Abstract

Background:

Cleft lip with or without palate is one of the common congenital malformations.

Aim:

To evaluate the per-operative complications of anesthesia, a comparative study was conducted in children using the endotracheal tubes available in the Institute so that the complications can be averted in future procedures.

Materials and Methods:

The rural population of Tripura, India.

Result:

Awareness was generated and the incidence of repair surgeries of cleft lip and palate was thus increased considerably in Dr. B. R. Ambedkar Memorial Teaching Hospital, Agartala, Tripura.

Conclusion:

The RAE tube has been found to be the choicest one and at a minimal risk for maintaining patients’ patent airway and other related complications.

Keywords: Anesthetic complication, cleft lip and palate, free surgery, Magill endotracheal tubes, RAE endotracheal tube, ring, adair, elwyn endotracheal tubes

INTRODUCTION

Cleft lip with or without palate is one of the common congenital malformations. The incidence of CLP worldwide is 1 in 700 live births and it is nearly 1 in 500 in India.[1] Inequalities exist in urban versus rural accessibility for repair surgeries. Accumulation of unrepaired clefts in lip and palate has proved a health care problem in India. In 2008, the World Health Organisation included cleft lip and palate in their Global Burden Disease (GBD), as these birth defects lead to significant infant mortality and childhood morbidity.[2] The associated facial disfigurement causes problems in feeding, speech and dental development and imparts significant psychosocial consequences if cleft repair surgeries are ignored till the adulthood. In India, over 35,000[3] infants are born with cleft lip or palate every year. The risk factors are considered as:

Family history- Cleft lip (cheiloschisis) is more likely to be inherited than a cleft palate (palatoschisis). Chances of offspring suffering from an affected parent, range from 3-5% and the sibling risk is 20-40% with one affected child. The incidence of the defect is 40-50% in Monozygotic twins and 5% in Dizygotic twins[4]

Sex - Male female ratio is 2:1 for a cleft lip and 1:2 for a cleft palate[5]

Left to right sided unilateral cleft lip ratio 2:1[5]

Unilateral clefts are nine times as common as bilateral clefts[5]

86% of bilateral cleft lips and 68% of unilateral cleft lips occur with a cleft palate[5]

Race as American Indian, Asians[6] are more prone.

ITIOLOGY

Defects in palatal growth during the first trimester result in both cleft lip and palate. The aetiology for cleft lip palate (CLP) is often unknown, though likely to result from environmental and genetic causes. The palate grows inwards to fuse in the midline in two stages. By 6 weeks the primary palate fuses which forms the alveolus and lip. By 8 weeks the secondary palate, which is posterior to the incisive foramen is formed. Suggested theories for failure of fusion include mechanical obstruction causing impaired development of mandible which prevents the descend of tongue. This obstructs fusion of the palatal shelves resulting in cleft formation.

Teratogenic exposure associated with CLP includes maternal consumption of alcohol, smoking,[7] anticonvulsants (phenytoin, benzodiazepines), salicylates, and cortisone. The risk increases with rising maternal and paternal age.[8] Folic acid 400 microgram/day has a role in preventing CLP.[9] Diagnosis of cleft lip (CP) and alveolus can be made at the routine 18-20 week antenatal ultrasound scan but clefts of the palate can only be excluded by examination of the palate after the baby is born.

Associated Conditions: Children with CLP may have multiple abnormalities, ranging from 4.3 to 63.4%.[10] Craniofacial abnormalities are most common, followed by congenital cardiac disease, renal and abdominal defect, Central Nervous System abnormalities, e.g. mental retardation and seizures.

AIM

To avert the adversities in future, a comparison of per-operative complications of anesthesia was done in cleft lip and palate repair surgeries within a specified age group using two different types of endotracheal tubes (ETT) viz Magill red rubber and south facing RAE (Ring, Adair, Elwyn), only which are available in the institution. This study was conducted during the period of January 2010 to January 2011 in Dr. B. R. Ambedkar Memorial Teaching Hospital Agartala, Tripura, India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

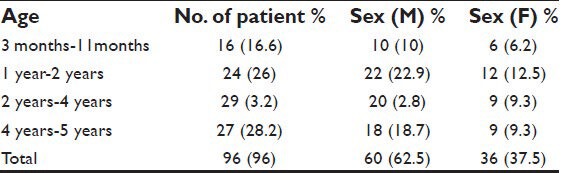

This is a prospective study of 102 facial cleft patients in the age group of 3 months to 5 years who presented for surgical repair. All patients were ASA 1 or 2 [Table 1]. Operating room records were the source of data which included age, sex, body weight, diagnosis, associated complications, and the anesthetic equipments used. Patient selection during pre-operative assessment for facial cleft surgery is critical in relation to the safety of general anesthesia. The screenings included history of illness, associated medical conditions and general examination. Investigations undertaken were routine urinalysis; blood film for malarial parasites, total and differential count, packed cell volume; body temperature measurement to rule out fever. Other screening includes height and weight measurements to rule out malnutrition. Patients with congenital anomalies or packed cell volume less than 30%, underweight or those with clinical signs of malaria or respiratory tract infection were excluded from the surgery.

Table 1.

Age, sex, percentage

Waiting until 3 months of age[11] gives time to detect most congenital abnormalities and allows anatomical and physiological maturation. Upper respiratory tract infections are particularly common at this age. Routine treatment of low-grade nasal infections with antibiotics reduce the incidence of postoperative complications[12] and impaired wound healing. Some of these children had a continuous nasal discharge without overt infection. Anemia detected in some of the children was probably from a combination of nutritional and physiological causes. Pre-anesthetic check up allowed time to assess general and specific problems and prepare the children for the repair surgeries concerned. Parents were communicated about the induction technique, provision of analgesia, possibility of additional measures such as postoperative nasopharyngeal airway insertion and postoperative feeding.

Anesthetic management

Over 70 years ago Magill recognised problems with airway management in children with CLP. The methods of assessment of difficult airway for adults are neither useful nor can be applied in children. So to predict which children may have difficult airways is not easy at times. For insertion of I.V. cannula, ketamine given intramuscularly (4-6 mg/kg) 30 min pre-operatively. Induction was done with glycopyrrolate (0.004 mg/kg), midazolam (0.05-0.1 mg/kg), and ketamine (1-2 mg/kg) intravenously. Endotracheal intubation performed using muscle relaxant suxamethonium 1-2 mg/kg. The approximate size of ETT calculated by using a formula (age/4 + 4.5 = estimated tube size) [Figure 1]. An adequate view of the larynx is usually easily achieved with gentle cricoid pressure and a choice of curved or straight laryngoscope blade. The cleft palates were packed with a small gauze roll to avoid the tendency of the laryngoscope to fall into a wide gap. A pediatric gum elastic bougie was a useful aid to intubation. Caution taken not to bruise the lip or palate to be repaired. Difficult laryngoscopy (Cormack and Lehane views grade III or IV[11]) occurs in upto 10% of ASA- I patients for CLP repair.[13] Pre-operative fasting fluid deficits and intraoperative losses were replaced with crystalloid. A single shot of intravenous antibiotic was given.

Figure 1.

Three images e.g., RAE (endotracheal tube) ETT in situ Magill (endotracheal tube) ETT in situ RAE south facing ETT for oral intubation used in the present study and RAE north facing ETT for nasal intubation not used in the present study

In the surgery for cleft palate the head was put more or less in hanging position by putting a roll under the patient's shoulder blades to extend the neck. The occiput of the head put on a head ring. A Boyle-Davis gag was used for the palate repair that keeps the mouth open and tongue clear. Care was taken (1) not to snare the ET tube within the blades of the gag, and (2) the endotracheal tube not kinked or pushed down into a bronchus when the gag was opened. In palate reconstruction, a pharyngeal pack is avoided for surgical convenience, but is a must in cleft lip repair surgeries to prevent soiling of the airway by ingestion of blood as the ET tubes used were non-cuffed. Protection given to the eyes using eye pads. The surgeon did Millard rotation advancement method for repair of cleft lip and two flap with the posterior alveolar ridge technique for cleft palate.[14] An infiltration with short acting local anesthetic and vasoconstrictor, injected in palate repair. Anesthesia maintained with halothane and nitrous oxide in 60% oxygen administered through the pediatric breathing system. Atracurium (0.5 mg/kg I.V.), a non-depolarising agent used and ventilation controlled manually. This makes a rapid wake up and recovery of reflexes, allowing controlled PaCO2, which may reduce blood loss. Although blood transfusion ion is uncommon, cross matching was available as CP repairs have the potential for significant blood loss. Intraoperatively monitoring was done to measure the heart rate, blood pressure, and arterial oxygen saturation (SpO2) with automatic electronic monitors. Throat packs were removed at the end of the operation and the oropharynx inspected for blood clots and oozing. Suction should be kept to a minimum. Non-depolarizing relaxants antagonized with neostigmine and glycopyrrolate. Extubation was done once the child was fully awake with wail and protective reflexes returned. Supplementary oxygen was given and then was sent to the ward. At 4-6 h post-operative, feeding with clear fluids started which was usually comforting for the child as the parents were also encouraged to join at this time. In some of the cases, it was necessary to splint the arms to prevent the baby disrupting the sutures. Careful monitoring performed for the first 12 h after surgery for the early detection of airway obstruction or post-operative bleeding. All anesthetic complications were documented. The results were analyzed and presented in Tables.

RESULT

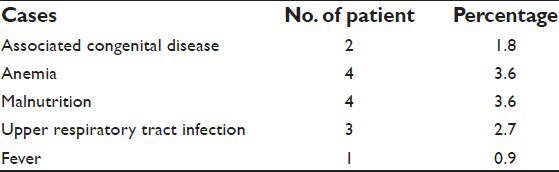

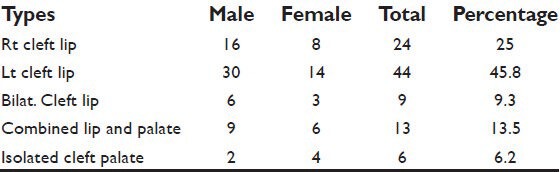

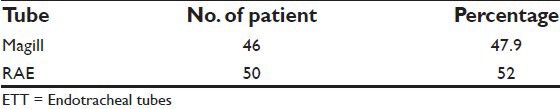

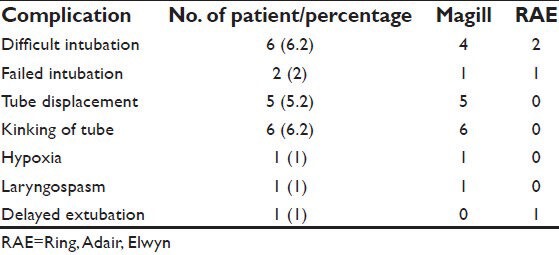

Out of the 110 facial cleft patients, 2 (1.8%) had congenital disorder and were excluded from the study. A total of 12 (10.9%) patients were unfit for anesthesia because of various medical conditions[15] such as respiratory tract infection (2.7%), anemia (3.6%), malnutrition (3.6%), and fever (0.9%) [Table 2]. Out of 96 cleft patients in whom surgery was done, (70.8%) had unilateral lip, (9.3%) had bilateral lip, (6.2%) had cleft palate, (13.5%) had combined lip and palate [Table 3]. A total of 50 (52%) children were done under RAE tube and 46 (47.9%) were done under Magill's tube [Table 4]. A total of 22 (22.9%) children suffered various anesthetic complications[16] which included difficult intubation (6.2%), failed intubation (2%), tube displacement (5.2%), kinking of tube (6.2%), hypoxia (1%), laryngospasm (1%) and delayed recovery from anesthesia (1%). The low incidence of hypoxia recorded may be due to adequate intraoperative monitoring with a pulse oximeter for immediate detection of hypoxia. In one (1%) case of cleft palate the child coughed on the endotracheal tube while awakening resulting in bleeding and delayed extubation [Table 5]. None of the patient required intraoperative blood transfusion.

Table 2.

Cases regretted for Anesthesia

Table 3.

Type of cleft lip and palate

Table 4.

Types of ETT used

Table 5.

Per-operative complication

DISCUSSION

The child presenting for primary repair of a cleft lip and/or palate presents a significant anesthetic challenge, where sharing the airway with the surgeon is involved. The ultimate choice of anesthetic technique depends on the availability of equipment, drugs, trained assistants, supportive environment, and co-operation at the level of the patient. Difficult laryngoscopy and intubation were associated with complete cleft palate and bilateral cleft lip due to the protruding maxilla. RAE (Ring, Adair, Elwyn) preformed tube[17] for orotracheal intubation, passes out over the lower lip, where it is fixed centrally, allowing optimal surgical access, has been found to be ideal for cleft lip and palate surgeries. The preformed bend in the tube (south facing type) exits from the mouth of the patient so calculatively that the connector with the circuit passes down the chin without hampering the airway. The red rubber Magill's endotracheal tube which were used in some of the cases had posed difficulty in maintaining its texture once draping of the surgical parts were done. Many at times the tube either got kinked or dislodged and slipped out of the trachea in mid surgery of cleft lip. In palate reconstruction where pharyngeal pack is avoided for surgical convenience, the displacement of ETT used to create an emergency for immediate repeat intubation. The kinking of Magill endotracheal tube recorded in six patients could have been avoided through the use of RAE tube which allows better operative field and surgical access. The inadvertent extubation which occurred in four patients during cleft palate was due to the inappropriate use of mouth gag which exerted too much traction on the endotracheal tube while extending the patient's head, another in cleft lip while adjusting the operative field. In two patients a naso-pharyngeal airway which does not damage the palate repair was required for 6 h post-operatively to relieve upper airway obstruction. Though RAE tube has a disadvantage as its fixed intra-oral length[17] it is always the choicest one because of the least risk for maintaining patients’ patent airway and thus safety of the anesthesiologist and uninterrupted operating field for the surgeon.

CONCLUSION

The part where the study was conducted, i.e., the North East India, the children of the low socio economic status, more of the local tribal population is found to be affected the most. Reasons observed are the inter-relation of (1) genetic, (2) environmental as habit of smoking or taking home brewed alcohol, (3) nutritional factors as lack of folic acid and/or other vitamins and poor food habit. Some patients presenting late in late childhood were due to poverty, ignorance, and long distance from cleft care surgical facilities. A marked increase in the number of cleft repair surgeries in the institution was observed from 2007. 8-10 cleft surgeries, in the study age group used to be done every month. In contrast to one or nil was done prior to that period of time. The increase in the number of patients is primarily because the surgeries are done free of cost to the patients by a visiting plastic surgeon under the banner of a NGO, secondarily the advertisement done by those who had undergone the surgeries while they go back to their villages.[18] This created awareness amongst the downtrodden people around, but the most important reason may be the safe and improved anesthetic technique to the vulnerable group of patients.

In conclusion, to have a relatively safe with a low rate peri-operative anesthetic complications for a favorable outcome in the repair surgeries of cleft lip and palate, we recommend the use of RAE (south facing) endotracheal tube.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Selvia R, Saranyaa GR, Murthyb J, Fa AM, Paula SF. Chromosomal abnormality in individuals with cleft lip or cleft palate. Sri Ramachandra Journal of Medicine. 2009 Jun;II(2):21–4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mossey P, Little J. Addressing the challenges of cleft lip and palate research in India. Indian J Plast Surg. 2009;42(Suppl):S9–S18. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.57182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. [Last accessed on 2012 Jun 12]. Available from: http://www.smiletrainindia.org .

- 4.Tolarova M, Oh H. Cleft Lip and Palate. 2006. May, [Last accessed on 2012 Jun 12]. eMedicine available from: http://www.emedicine.com/ped/topic2679.htm .

- 5. Available from: http://www.seattlechildrens.org/chromosomal and genetic conditions, cleft lip and palate .

- 6.Mayo clinic.com. Study by Mayo clinic staff,/health/cleft lip and Cleft palate. [Last accessed 2012 Jun 12];2008 Apr 19; [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi M, Wehby GL, Murray JC. Review on Genetic Variants and Maternal Smoking in the Etiology of Oral Clefts and Other Birth Defects. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2008;84:16–29. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bille C, Skytthe A, Vach W, Knudsen LB, Andersen AM, Murray JC, et al. Parent's age and the risk of oral clefts. Epidemiology. 2005;16:311–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000158745.84019.c2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilcox AJ, Lie RT, Solvoll K, Taylor J, McConnaughey DR, Abyholm F, et al. Folic acid supplements and risk of facial clefts: National population based case-control study. BMJ. 2007;334:464. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39079.618287.0B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Venkatesh R. Syndromes and anomalies associated with cleft. Indian J Plast Surg. 2009;42(Suppl):S51–5. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.57187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hardcastle T. Anaesthesia for repair of cleft lip and palate. J Perioper Pract. 2009;19:20–3. doi: 10.1177/175045890901900102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desalu I, Adeyemo W, Akintimoye M, Adepoju A. Airway and Respiratory Complications in Children Undergoing Cleft Lip and Palate Repair. Ghana Med J. 2010;44:16–20. doi: 10.4314/gmj.v44i1.68851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gunawardana RH. Difficult laryngoscopy in cleft lip and palate surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1996;76:757–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/76.6.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis MB. Timing and technique of cleft palate repair. In: Marsh JL, editor. Current Therapy in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Vol. 1. Mosby-Year Book; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwari DY, Chinda JY, Olasoji HO, Adeosun OO. Cleft lip and palate surgery in children: Anaesthetic Considerations. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 2010;7:174–7. doi: 10.4103/0189-6725.70420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fillies T, Homann C, Meyer U, Reich A, Joos U, Werkmeister R. Perioperative complications in infant cleft repair. Head Face Med. 2007;3:9. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Savey AJ, Diva A. 5th ed. China: Elsevier; 2005. Wards Anaesthetic Equipment; p. 187. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donkor P, Bankas DO, Agbenorku P, Plange-Rhule G, Ansah SK. Cleft lip and palate surgery in Kamasi, Ghana: 2001-2005. J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18:1376–9. doi: 10.1097/01.scs.0000246504.09593.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]