Abstract

Background

The mechanisms leading to the development of functional motor symptoms (FMS) are of pathophysiological and clinical relevance, yet are poorly understood.

Aim

The aim of the present study was to evaluate whether impaired emotional processing at the cognitive level (alexithymia) is present in patients affected by FMS. We conducted a cross-sectional study in a population of patients with FMS and in two control groups (patients with organic movement disorders (OMD) and healthy volunteers).

Methods

55 patients with FMS, 33 patients affected by OMD and 34 healthy volunteers were recruited. The assessment included the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20), the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, the Reading the Mind in the Eyes’ Test and the Structured Clinical Interview for Personality Disorders.

Results

Alexithymia was present in 34.5% of patients with FMS, 9.1% with OMD and 5.9% of the healthy volunteers, which was significantly higher in the FMS group (χ2 (2)=14.129, p<0.001), even after controlling for the severity of symptoms of depression. Group differences in mean scores were observed on both the difficulty identifying feelings and difficulty describing feelings dimensions of the TAS-20, whereas the externally orientated thinking subscale score was similar across the three groups. Regarding personality disorder, χ2 analysis showed a significantly higher prominence of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) in the FMS group (χ2 (2)=16.217, p<0.001) and 71.4% of those with OCPD also reached threshold criteria for alexithymia.

Conclusions

Because alexithymia is a mental state denoting the inability to identify emotions at a cognitive level, one hypothesis is that some patients misattribute autonomic symptoms of anxiety, for example, tremor, paraesthesiae, paralysis, to that of a physical illness. Further work is required to understand the contribution of OCPD to the development of FMS.

Keywords: NEUROPSYCHIATRY

Introduction

Functional motor symptoms (FMS), which include abnormal movements and weakness, are part of the wide spectrum of functional neurological symptoms, one of the commonest diagnoses made in neurological practice.1 Patients affected by FMS have levels of disability, distress and healthcare usage that equals, and in some cases surpasses, patients with neurodegenerative disease.2

Recent years have seen a surge of research interest in functional neurological symptoms. One outcome has been a reduction in the emphasis on identifiable traumatic events (such as sexual abuse in childhood or adult life, remote or recent life events) being antecedents to the development of FMS. Several studies have demonstrated that such traumatic events, although clearly important, might not play a unique role in the aetiology of FMS3 4, and, in the most recent revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5),5 the presence of a psychological stressor has been downgraded from an essential to a supportive criterion for the diagnosis of conversion disorder (functional neurological symptom disorder).6

Recent cognitive and neurobiological models of the pathophysiology of functional neurological symptoms have concentrated more on ‘how’ symptoms might be produced than on ‘why’. Research findings have identified three putative mechanistic processes leading to functional movement disorders (FMDs): abnormal attentional focus,7 abnormal beliefs and expectations,8 and abnormalities in sense of agency.9 These three processes have been combined in recent neurobiological models where abnormal predictions related to movement or perception are triggered by self-focused attention, and the resulting percept or movement is generated without a normal sense of agency.10 11

Recent aetiological work has highlighted a possible role for physical precipitating factors in the triggering of functional neurological and other somatic symptoms, and in some cases clear links have been made between the nature of the physical precipitant and the phenomenology of the resulting functional symptom.12 However, the physical precipitants identified (minor injury, flu-like illness, diarrhoea, migraine) are very common in the healthy population, and therefore why they should trigger functional symptoms in only a small proportion of people remains unexplained. Therefore, the investigation of mechanistic factors in the development of functional neurological symptoms is of continued relevance and importance.

One clue has been the observation that physiological markers of panic or anxiety are often reported at onset of FMSs (eg, in association with a physical trigger) or in a persistent manner throughout the illness, but that patients only rarely report a concurrent emotional state of anxiety.13 These studies in patients with FMSs link to previous work in patients with non-epileptic attacks where often patients will report or be observed to have physiological changes seen in panic episodes but generally do not report feeling ‘panicked’. This phenomenon has been named as ‘non-fearful panic’.14

Failure to identify and describe emotions in oneself and a difficulty in distinguishing and appreciating the emotions of others is called alexithymia, a term coined by Sifneos (1973) to describe certain clinical characteristics observed among patients with psychosomatic disorders who had difficulty engaging in insight-oriented psychotherapy.15 Most previous studies of alexithymia in patients with functional neurological symptoms have been restricted to non-epileptic seizures (NES).16 17 Here, both patients with epilepsy and those with NES had similar but very high rates of alexithymia. Only one recent study has assessed the prevalence of alexithymia in a general group of conversion disorders, and this found higher rates in patients compared with controls.18 No studies have previously investigated the prevalence of alexithymia in a population solely of patients affected by FMSs. We were specifically interested in assessing this, as high rates of alexithymia could help provide an explanation for the clinical observation of a dissociation between patients’ endorsement of physiological markers of panic/anxiety and their denial of the emotional experience of panic/anxiety.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the prevalence of alexithymia in patients affected by FMS and to clarify its pathophysiological role. In addition, we determined the presence of other mental states that may confound the interpretation of alexithymia, namely, personality disorder (PD), depression and deficits in theory of mind indicative of impaired social cognition. To do this we conducted a cross-sectional study in a population of patients with FMS presenting to a neurological service for the first time and in two control groups (patients with organic movement disorders (OMD) and healthy controls).

Materials and methods

Subjects

Patients affected by FMS and OMD were recruited from neuropsychiatry and neurology outpatient clinics at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery (NHNN), London, UK. Fifty-five patients affected by FMS assessed at NHNN between January and July 2013 were included in the study, and they were compared with 33 age-matched and sex-matched patients with a diagnosis of OMD and 34 age-matched and sex-matched healthy controls. Patients with FMS were included if they had ‘clinically definite’19 FMS. We used the Fahn & Williams criteria for movement disorders, and, for functional weakness, we used the DSM IV A, C, D and E Conversion Disorder criteria. The diagnosis was ascertained by a neurologist and psychiatrist on the basis of clinical presentation and appropriate investigations. We did not select cases based on aetiological assumptions (eg, presence of psychological factors); rather we decided to focus on the motor symptoms themselves to formulate a positive diagnosis. Patients affected by OMD were included after receiving a diagnosis by a consultant neurologist at the NHNN. Healthy individuals mainly comprised hospital staff and visitors to the hospital.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria for all the three groups were (i) age less than 18 years; (ii) inability to communicate with the researcher or complete questionnaires because of language difficulties, severe learning disabilities or dementia; (iii) any other serious neurological or medical illnesses; and (iv) the presence of both a functional and an OMD (functional overlay).

All subjects were assessed by a neuropsychiatrist (BD) at the NHNN. Demographic information was obtained from each participant through a brief self-report questionnaire designed for the study.

Assessments

The 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20): This is a well-validated and commonly used measure of alexithymia;20 it is a multidimensional self-report instrument with a three-factor structure: difficulty identifying feelings (DIF), difficulty describing feelings (DDF) and externally orientated thinking (EOT). As well as comparing TAS scores across the groups, we took the suggested TAS criterion score of ≥61 as categorically denoting alexithymia.

The Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS): This is a 10-item semistructured clinician-rated interview widely used to measure levels of depression; it has been showed to yield reliable and internally consistent scores and to demonstrate criterion-related validity.21

The Reading the Mind in the Eyes’ Test (Eyes): This is an advanced test of theory of mind. It is widely used to assess individual differences in social cognition and emotion recognition across different groups and cultures. Although it is not a diagnostic instrument, several studies indicate that the Eyes is a reliable instrument for assessing social cognition in adults.22

The Structured Clinical Interview for Personality Disorders (SCID II): This is a semistructured assessment instrument for PDs. Several studies have shown that it is reliable, internally consistent and valid.23

Ethical approval was obtained from the UCL Institute of Neurology and National Hospital for Neurology Joint Ethics Committee, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS V.21). The variables were first tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilks test. The variables that were not normally distributed (p<0.05) were log10-transformed. For continuous data, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test for differences across the three groups with posthoc Bonferroni pairwise comparisons when significant. The χ2 test was used for categorical data. Bonferroni correction was applied to correct for multiple comparisons. Analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) were carried out using scores from the MADRS and the Eyes as covariates where appropriate.

Results

In total, 55 patients with FMS (42 of 55 females (76%); mean age 43 years (SD, 10.55 years)), 33 patients with OMD (23 of 33 females (70%); mean age 45.70 years (SD, 14.64 years)) and 34 healthy controls (23 of 34 females (68%); mean age 42.18 years (SD, 11.32 years)) were included in the study. Patients’ clinical characteristics are shown in table 1. Age and gender were not significantly different between the three groups (age: F (2, 119)=0.809, p=0.448; gender: χ2 (2)=0.927, p=0.629).

Table 1.

Motor characteristics in functional and organic patient groups

| Symptom | Patients with functional motor symptoms n (%) |

Patients with organic movement disorders n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Tremor | 12 (21.8%) | 2 (6.1%) 2 essential tremor |

| Myoclonus | 12 (21.8%) | 2 (6.1%) 2 cortical myoclonus |

| Dystonia | 12 (21.8%) | 27 (81.8%) 15 cervical dystonia 12 focal hand dystonia |

| Weakness | 16 (29.1%) | 2 (6.1%) 1 transverse myelitis 1 motor neuron disease |

| Gait | 1 (1.8%) | |

| Tic | 2 (3.6%) |

There was a significant difference in TAS-20 alexithymia scores between the three groups (F (2, 119)=20.467, p<0.001), as shown in table 2. Posthoc analysis showed that each pairwise comparison was significant (FMS vs OMD: p=0.031; FMS vs healthy controls: p<0.001; OMD vs healthy controls: p=0.003). Alexithymia was present in 34.5%, 9.1% and 5.9% of the FMS, OMD and healthy control groups, respectively. The proportions of alexithymic patients (TAS-20 ≥ 61) differed significantly between groups (χ2 (2)=14.129, p<0.001). Comparisons between groups showed a significantly increased proportion of high-alexithymic subjects in patients with FMS (34.5%) as compared with patients with OMD (9.1%; χ2 (1)=7.127, p=0.08) and healthy controls (5.9%; χ2 (2)=89.000, p<0.01).

Table 2.

Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) total scores, percentage reaching criteria for presence of alexithymia (>60) and subscale scores for DIF, DDFs and EOT

| Scales | Patients with FMS | Patients with OMD | Healthy controls | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAS-20 score mean (SD) | 55.38 (12.12) | 49.19 (9.13) | 40.79 (8.54) | <0.002 |

| TAS-20 < 51 n (%) | 24 (43.6) | 19 (57.6) | 31 (91.2) | <0.002 |

| TAS-20=52–60 n (%) | 12 (21.8) | 11 (33.3) | 1 (2.9) | <0.003 |

| TAS-20 > 61 n (%) | 19 (34.5) | 3 (9.1) | 2 (5.9) | <0.001 |

| DIF mean (SD) | 14.42 (4.5) | 12.06 (3.8) | 9.97 (3.1) | <0.003 |

| DDF mean (SD) | 21.22 (5.8) | 17.48 (5.4) | 12.74 (4.4) | <0.002 |

| EOT Mean (SD) | 19.76 (4.6) | 19.85 (3.6) | 18.06 (4.0) | 0.128 |

DDF, difficulty describing feeling; DIF, difficulty identifying feelings; EOT, externally orientated thinking; FMS, functional motor symptoms; OMD, organic movement disorders.

Mean scores on the Eyes test and MADRS are shown in table 3. One-way ANOVA on the Eyes test did not show a significant effect of group (F (2, 119)=1.052, p=0.353). For the MADRS, there was a significant main effect of group (F (2, 119)=11.455, p<0.001). Posthoc pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences between patients with FMS and patients with OMD (p=0.007) and patients with FMS and healthy controls (p<0.000). Significant differences on total alexithymia scores remained when MADRS score was entered as a covariate using ANCOVA (F (3, 121)=26.636, p<0.001).

Table 3.

MADRS, Reading the Mind in the Eyes’ Test (Eyes) scores

| Scales | Patients with FMS | Patients with OMD | Healthy controls | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MADRS score mean (SD) | 10.65 (7.5) | 6.27 (5.8) | 4.32 (4.59) | <0.002 |

| Eyes score mean (SD) | 23.38 (4.3) | 22.73 (4.1) | 24.21 (3.9) | 0.353 |

FMS, functional motor symptoms; MADRS, Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale; OMD, organic movement disorder.

Group differences were observed in both the DIF and DDF dimensions of the TAS-20, whereas the EOT subscale appeared relatively consistent across the three groups, as shown in table 2. One-way ANOVA on the DIF subscale scores showed a significant main effect of group (F (2, 119)=13.383, p<0.001). Posthoc pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences between patients with FMS and patients with OMD (p=0.025) and between patients with FMS and healthy controls (p<0.001). However, no significant difference was observed between patients with OMD and healthy controls (p=0.102). One-way ANOVA on the DDF subscale also demonstrated a significant main effect of group (F (2, 119)=26.281, p<0.001). Pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences between patients with FMS and patients with OMD (p=0.006), patients with FMS and healthy controls (p<0.001), and patients with OMD and healthy controls (p=0.001). With respect to the EOT dimension, one-way ANOVA revealed a non-significant effect of group (F (2, 119)=2.088, p=0.128). ANCOVA with MADRS score as a covariate was performed in order to detect any effect of depression on the DIF and DDF subscales, with results showing that depression did not act as a significant confounding factor (F (3, 121)=18.549, p<0.001 for DIF; F (3, 121)=33.727, p<0.001 for DDF).

Correlations between TAS-20 total score, TAS-20 subscores and the Eyes score were not significant (range of r=−0.126 to 0.006).

Regarding PDs, the prevalence of each subtype is shown in table 4. χ2 Analysis showed a significant difference only in the distribution of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) (χ2 (2)=16.217, p<0.001) within the three groups. The presence of OCPD was found to strongly correlate with the presence of alexithymia (r=0.283, p=0.002); in fact, 71.4% of patients who had OCPD were also alexithymic. Comparisons between groups showed a significantly increased proportion of OCPD in patients with FMS as compared with patients with OMD (χ2 (1)=9.989, p=0.02) and healthy controls (χ2 (1)=7.600, p=0.006).

Table 4.

Structured Clinical Interview for Personality Disorders (SCID II) scores

| PD subtype | Patients with FMS, n (%) |

Patients with OMD, n (%) |

Healthy controls, n (%) |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avoidant | 2 (3.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.290 |

| Dependent | 2 (3.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.290 |

| Obsess-compulsive | 14 (25.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| Passive-aggressive | 2 (3.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | 0.554 |

| Depressive | 3 (5.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.154 |

| Paranoid | 3 (5.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.154 |

| Schizotypal | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.257 |

| Schizoid | 2 (3.6) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.543 |

| Histrionic | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.257 |

| Narcissistic | 2 (3.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.290 |

| Borderline | 3 (5.4) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.372 |

| Antisocial | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.541 |

FMS, functional motor symptoms; OMD, organic movement disorder; PD, personality disorder.

Discussion

Alexithymia

Our data suggest that patients affected by FMS are significantly more alexithymic than patients with OMDs and healthy controls, with a third of FMS patients reaching full criteria for alexithymia. The prevalence of alexithymia still remained significantly higher in patients with FMS even after controlling for symptoms of depression. The relationship between alexithymia and depression has been widely described, and it is well documented that alexithymia represents a risk factor for the development of depressive disorders.24 However, we found alexithymia to be a significant marker for FMS, independent of the presence of symptoms of depression. With respect to the three subscales of the TAS-20, patients with FMS were significantly more alexithymic on factor I (DIFs) and II (DDFs), whereas we did not find a significant difference on factor III (EOT). According to De Gucht et al,25 the internal consistency of the EOT subscale is considerably lower than that of the two other subscales, suggesting that a two-factor approach, rather than a three-factor one, could be more appropriate to measure alexithymia. It may also be the case that for patients with FMS, difficulty in identifying and explaining emotions relates only to the self, and not generally to the understanding of the emotional states of others. As additional evidence for this interpretation, patients with FMS were not significantly different from controls on the Eyes test, suggesting that the ability to recognise emotional expressions and the capacity to determine the mental state of an individual based on a partial facial expression (measures of social cognition) are not compromised in patients with FMS. Similar results regarding Theory of Mind have been found recently by Stonnington et al26 in a population of patients affected by conversion disorders.

In the last few years, several studies have examined the relationship between alexithymia and functional neurological symptoms, mainly focusing on NESs. The most common finding is that patients with NESs are no more likely to have alexithymia than patients with epileptic seizures;16–27 one study has found an increased prevalence in NES,28 although another suggests that emotional dysregulation, including alexithymia, may pertain to a small subgroup.29 Only one study has assessed alexithymia in other functional disorders.18 This study differs from ours in several important ways: they grouped together all types of functional neurological disorder, they used a single comparison group of healthy controls and they did not assess comorbidities. Nevertheless, they too found a higher rate of alexithymia in patients than controls, although this was higher than ours (74.5%), and they also found that this pertained to the DIF and DDF factors only.

Previous studies have reported the prevalence of alexithymia in the general population as approximately 10%.30 This tallies with that of our OMD group (9.1%) but is higher than our healthy controls (5.9%). The discrepancy in the prevalence of alexithymia between our control sample and the control samples of previous studies could be due to the relatively small size of this group. Alternatively, it could be related to the use of hospital staff as controls subjects—alexithymia has been shown to be linked to the level of education and socioeconomic status that may have differed between the groups.24

Personality disorders

Our data also showed a significantly increased proportion of OCPD in patients with FMS as compared with patients with OMD and healthy controls. Previous studies have already underlined the role of PD as a risk factor for the onset and maintenance of both FMS31 and NES,32 but no studies to date have found higher prevalence specifically of OCPD in patients with functional neurological symptoms. Feinstein et al31 found a prevalence of PD of 42% in their sample of patients affected by FMDs; these were mostly antisocial, borderline and dependent PDs. Similar results were found by Howarka et al32 and by Reuber et al33 in patients affected by NES: both studies found high rates of borderline PDs in patients with NES. On the other hand, Kranick et al,13 who assessed personality traits in a population of patients affected by FMDs using the Revised Neuroticism-Extroversion-Openness Personality Inventory, a dimensional instrument, did not find any significant difference in their group of patients compared with healthy controls. This discrepancy might be consistent with the observation that different forms of functional neurological symptoms (NESs, functional weakness or movements) may be associated with different personality traits (assessed by categorical instruments).

Our results, showing a higher prevalence of OCPD in patients with FMS, are in contrast with the results of the abovementioned studies. Although our study has been conducted with a relatively small sample of patients, it differs significantly from that of Feinstein et al,31 which has no comparative control group, and Kranick et al,13 which has used just a dimensional instrument. Further studies are needed to clarify the prevalence of each subtype of PD in a bigger population of patients with FMS.

In our study, there was a large overlap between OCPD and alexithymia with 10 of 14 OCPD patients also meeting criteria for alexithymia. This suggests that both scales may be measuring similar traits. However, this is unlikely to be the explanation as the TAS asks almost exclusively about emotions, whereas the SCID focuses on thoughts and behaviour. Nevertheless, alexithymia as a construct does include features overlapping with those of OCPD. For example, early studies described patients with psychosomatic symptoms developing compulsive behaviours and ‘a life guided by rules and regulations’ as well as emotional disconnection.34 Nemiah et al35 showed that alexithymia is characterised by (i) DIFs, differentiating among the range of common affects, and distinguishing between feelings and the bodily sensations of emotional arousal; (ii) difficulty finding words to describe feelings to other people; (iii) constricted imaginal processes, as evidenced by a paucity or absence of fantasies referable to drives and feelings; and (iv) a thought content characterised by a preoccupation with the minute details of external events. This therefore suggests that OCPD may not be an independent risk factor for the development of functional motor disorder and that alexithymia is a more relevant personality construct for understanding the mechanism of developing functional symptoms. However of relevance is that Kang et al36 have recently found an overlap between alexithymia and obsessive-compulsive disorder with 41% comorbidity. To clarify this further, future studies should include an assessment of obsessive-compulsive disorder, as well as OCPD.

Integration with current neurobiological models

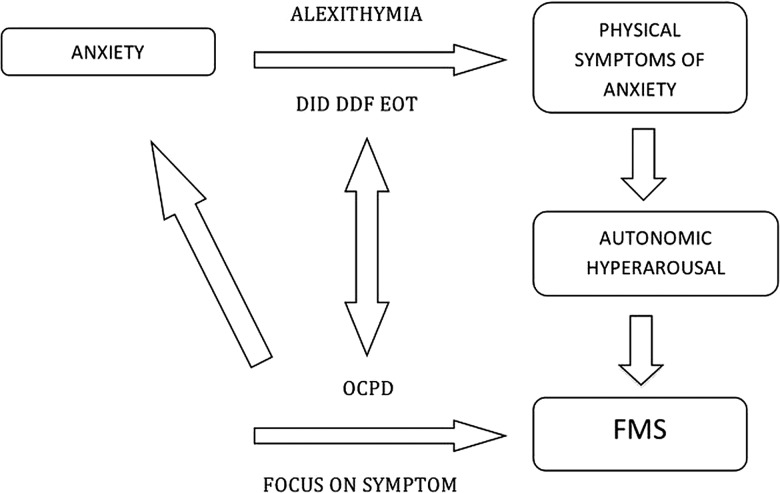

How might alexithymia be a relevant mechanistic factor for the development of FMS? We have discussed above the evidence that patients with FMS frequently report physiological markers of panic and anxiety, without reporting an emotional state of anxiety. These data are complemented by evidence that patients with FMS have greater arousal as indicated by galvanic skin response, higher baseline cortisol, reduced heart rate variability, greater threat vigilance and greater startle response to arousing stimuli.37 38 Patients with FMS have been found to have greater amygdala activity in response to arousing stimuli and impaired habituation along with greater functional connectivity between the amygdala and supplementary motor areas.39 We speculate that the autonomic arousal occurring during a physical precipitating event, or more chronically, fails to be interpreted correctly as anxiety/panic in patients with an impairment in the cognitive processing of emotional arousal (ie, alexithymia). These sensations may instead be interpreted as symptoms of physical illness because of an attribution of sensations to organic rather than psychological or benign causes. This vicious cycle might be further fostered in patients with pronounced obsessive-compulsive personality traits. In fact, the pervasive pattern of mental controlling and checking, at the expense of flexibility and openness,5 might reinforce the patient's belief of illness and exaggerated focus on physical symptoms. Individuals suffering from obsessive-compulsive traits often are not in touch with their emotional states as much as their thoughts. This interpretation, shown in figure 1, links directly to the key concepts proposed in the neurobiology of FMS: symptom-related beliefs/expectations and symptom/self-directed attention.40

Figure 1.

Integration with current neurobiological models. Patients with FMS frequently report physiological markers of panic and anxiety, without reporting an emotional state of anxiety. These data are complemented by evidence that patients with FMS have greater arousal. We speculate that the autonomic arousal occurring during a physical precipitating event, or more chronically, fails to be interpreted correctly as anxiety/panic in patients with an impairment in the cognitive processing of emotional arousal (ie, alexithymia). These sensations may instead be interpreted as symptoms of physical illness because of an attribution of sensations to organic rather than psychological or benign causes. This vicious cycle might be further fostered in patients with pronounced obsessive-compulsive personality traits. In fact, the pervasive pattern of mental controlling and checking, at the expense of flexibility and openness, might reinforce the patient's belief of illness and exaggerated focus on physical symptoms. DIF, difficulty identifying feelings; DDF, difficulty describing feelings; EOT, externally orientated thinking; OCPD, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder; FMS, functional motor symptoms.

Relevance for management

Considering alexithymia as a risk factor for the development of FMS might help the specialist not only in the definition of the diagnosis but also in the communication of the diagnosis. For example, communicating the diagnosis to a FMS patient who is alexithymic and completely focused on his/her physical symptoms might benefit from a more physical explanation rather than from a pure psychological one. In addition, there are several potential implications for treatment, particularly with respect to use of psychological therapies. First, a psychological treatment in a patient with alexithymia requires specific skills. Previous work has suggested that alexithymia is a negative prognostic indicator for many psychological treatments, particularly those focusing on insight, emotional awareness and a close alliance with a therapist.41 In contrast, alexithymia may not affect more structured cognitive-behavioural treatments and may even be associated with better outcomes of such treatments. It has been hypothesised that the compulsive nature and external focus of people with alexithymia prompt greater adherence to structured exercises and behavioural recommendations. With regards to the prognosis, although to date no studies have been conducted assessing the influence of alexithymia on FMS prognosis, it has been shown that alexithymia predicts poorer outcomes of treatment for anxiety and somatoform disorders, depression and functional gastrointestinal disorders.41

Limitations

We acknowledge the limits of our study: first, we did not conduct a systematic interview for Axis I psychiatric disorders to establish diagnoses of affective and anxiety disorders. In particular, we did not assess the prevalence of anxiety symptoms in our samples—anxiety might be a confounding factor for alexithymia, which we were unable to address.42 Second, this study is limited by the lack of a disability-matched OMD control group as 81% of patients had a diagnosis of dystonia, which is not representative of all movement disorders. Third, the choice of some scales might be criticised: although the TAS-20 is the most widely used instrument for assessing alexithymia, the use of a self-reported scale might be not appropriate, as alexithymic patients are not very self-reflective; with respect to the assessment of PD, it might have been more appropriate using a double instrument (categorical and dimensional approach), rather than just a categorical one. Fourth, the design of our study, a cross-sectional one, does not allow direct interpretation of causality.

Conclusions

The associations between alexithymia, OCPD and FMS are potentially relevant for understanding the mechanism developing functional neurological symptoms, the diagnostic explanation given to patients and treatment. As our study examined patients solely with functional movement symptoms, further studies are needed to clarify the prognostic role of alexithymia in patients affected by other forms of functional neurological symptoms.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff and patients of the participating clinics and all the neurologists who took part in this study: Prof. Kailash Bathia, Doctor Prasad Korlipara and Doctor Antonella Macerollo. EMJ is supported by UCLH NIHR Biomedical Research Centre. MJE was funded by an NIHR Clinician Scientist award.

Footnotes

Contributors: Each author has contributed in all the following: (1) conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and (3) final approval of the version to be published.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: UCL Institute of Neurology and National Hospital for Neurology Joint Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Stone J, Carson A, Duncan R, et al. Who is referred to neurology clinics?—the diagnoses made in 3781 new patients. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2010;112:747–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carson A, Stone J, Hibberd C, et al. Disability, distress and unemployment in neurology outpatients with symptoms “unexplained by organic disease”. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2011;82:810–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roelofs K, Spinhoven P. Trauma and medically unexplained symptoms towards an integration of cognitive and neuro-biological accounts. Clin Psychol Rev 2007;27:798–820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharpe D, Faye C. Non-epileptic seizures and child sexual abuse: a critical review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev 2006;26:1020–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-V). 5th edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Espay AJ, Goldenhar LM, Voon V, et al. Opinions and clinical practices related to diagnosing and managing patients with psychogenic movement disorders: an international survey of movement disorder society members. Mov Disord 2009;24:1366–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta A, Lang AE. Psychogenic movement disorders. Curr Opin Neurol 2009;22:430–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pareés I, Kassavetis P, Saifee TA, et al. Jumping to conclusions’ bias in functional movement disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2012;83:460–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kranick SM, Moore JW, Yusuf N, et al. Action-effect binding is decreased in motor conversion disorder. Implications for sense of agency. Mov Disord 2013;28:1110–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voon V, Brezing C, Gallea C, et al. Aberrant supplementary motor complex and limbic activity during motor preparation in motor conversion disorder. Mov Disord 2011;26:2396–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards MJ, Adams RA, Brown H, et al. A Bayesian account of ‘hysteria’. Brain 2012;135:3495–512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stone J, Carson A, Aditya H, et al. The role of physical injury in motor and sensory conversion symptoms: a systematic and narrative review. J Psychosom Res 2009;66:383–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kranick S, Ekanayak V, Martinez V, et al. Psychopathology and psychogenic movement disorders. Mov Disord 2011;26:1844–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen J, Tsuchiya M, Kawakami N, et al. Non-fearful versus fearful panic attacks: a general population study from the National Comorbidity Survey. J Affect Disord 2009;112:273–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sifneos PE. The prevalence of ‘alexithtymic’ characteristic mechanisms in psychosomatic patients. Psychother Psychosom 1973;21:133–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myers L, Matzener B, Lancman M, et al. Prevalence of alexithyima in patients with psychogenic non-epileptic seizures and epileptic seizures and predictors in psychogenic non-epilepetic seizures. Epilepsy Behav 2013;26:153–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bewley J, Murphy PN, Mallows J, et al. Does alexithymia differentiate between patients with nonepileptic seizures, patients with epilepsy, and nonpatient controls? Epilepsy Behav 2005;7:430–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gulpek D, Kaplan FK, Kesebir S. Alexithymia in patients with conversion disorder. Nord J Psychiatry 2013. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams DT, Ford B, Fahn S. Phenomenology and psychopathology related to psychogenic movement disorders. Adv Neurol 1995;65:231–57 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bagby RM, Taylor GJ, Parker JD. The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale-II: convergent, discriminant, and concurrent validity. J Psychosom Research 1994;38:33–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davidson J, Turnbull CD, Strickland R, et al. The Montgomery-Asberg Depression Scale: reliability and validity. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1986;73:544–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vellante M, Baron-Cohen S, Melis M, et al. The “reading the mind in the eyes” test: systematic review of psychometric properties and a validation study in Italy. Cogn Neuropsychiatry 2012;18:326–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lobbestael J, Leurgans M, Arntz A. Inter-rater reliability of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID I) and Axis II Disorders (SCID II). Clin Psychol Psychother 2011;18:75–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saarijarvi S, Salminen JK, Toikka TB. Alexithymia and depression: a 1-year follow-up study in outpatients with major depression. J Psychosom Res 2001;51:729–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Gucht V, Heiser W. Alexithymia and somatisation: a quantitative review of the literature. J Psychosom Res 2003;54:425–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stonnington CM, Locke DE, Hsu CH, et al. Somatization is associated with deficits in affective Theory of Mind. J Psychosom Res 2013;74:479–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tojek TM, Lumley M, Barkley G, et al. Stress and other psychosocial characteristics of patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Psychosomatics 2000;41: 221–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaplan MJ, Dwivedi AK, Privitera MD, et al. Comparisons of childhood trauma, alexithymia, and defensive styles in patients with psychogenic non-epileptic seizures vs. Epilepsy: implications for the etiology of conversion disorder. J Psychosom Res 2013;75:142–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown RJ, Bouska JF, Frow A, et al. Emotional dysregulation, alexithymia, and attachment in psychogenic nonepileptic seizure. Epilepsy Behav 2013;29: 178–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor GJ, Bagby RM, Parker JDA. Disorder of affect regulation: Alexithymia in medical and psychiatric illness. New York: Cambridge Univ Press, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feinstein A, Stergiopoulos V, Fine J, et al. Psychiatric outcome in patients with a psychogenic movement disorder: a prospective study. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 2001;14:169–76 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Howorka J, Nezadal T, Herman E. Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures, prospective clinical experience: diagnosis, clinical features, risk factors, psychiatric comorbidity, treatment outcome. Epilept Disord 2007;9:52–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reuber M, Pukrop R, Bauer J, et al. Multidimensional assessment of personality in patients with psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004;75:743–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor GJ, Bagby RM. Psychoanalysis and empirical research: the example of Alexithymia. J Am Psychoanal Assoc 2013;61:99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nemiah JC, Freyberger H, Sifneos PE, Alexithymia: a view of the psychosomatic process. In: Hill OW.ed. Modern trends in psychosomatic medicine. Vol. 3 London: Butterworths, 1976, 430–9 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kang JI, Namkoong K, Yoo SW, et al. Abnormalities of emotional awareness and perception in patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder. J Affect Disord 2012;141;286–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bakvis P, Roelofs K, Kuyk J, et al. Trauma, stress, and preconscious threat processing in patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsia 2009;50:1001–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seignourel PJ, Miller K, Kellison I, et al. Abnormal affective startle modulation in individuals with psychogenic [corrected] movement disorder. Mov Disord 2007;22:1265–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Voon V, Brezing C, Gallea C. Emotional stimuli and motor conversion disorder. Brain 2010;133:1526–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edwards MJ, Fotopoulou A, Parees I. Neurobiology of functional movement disorders. Curr Opin Neurol 2013;26:442–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lumley MA, Neely LC, Burger AJ. The assessment of alexithymia in medical settings: implications for understanding and treating health problems. Pers Assess 2007;89:230–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marchesi C, Brusamonti E, Maggini C. Are alexithymia, depression and anxiety different constructs in affective disorders? J Psychosom Res 2000;49:43–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]