In three quinolone compounds, the 1,4-dihydropyridine (1,4-DHP) rings adopt flat-boat conformations which are bisected by the plane of the pseudo-axial brominated aryl ring. The cyclohexanone rings adopt an envelope conformation. In all three compounds, intermolecular N—H⋯O hydrogen bonds link the molecules into extended chains. Intermolecular halogen bonding between Br and the ester carbonyl O atom is observed in two of the compounds.

Keywords: crystal structure; structure–activity relationships; calcium-channel antagonists; quinolone compounds; halogen bonding; 1,4-dihydropyridine rings; hydrogen bonding; bromine scanning

Abstract

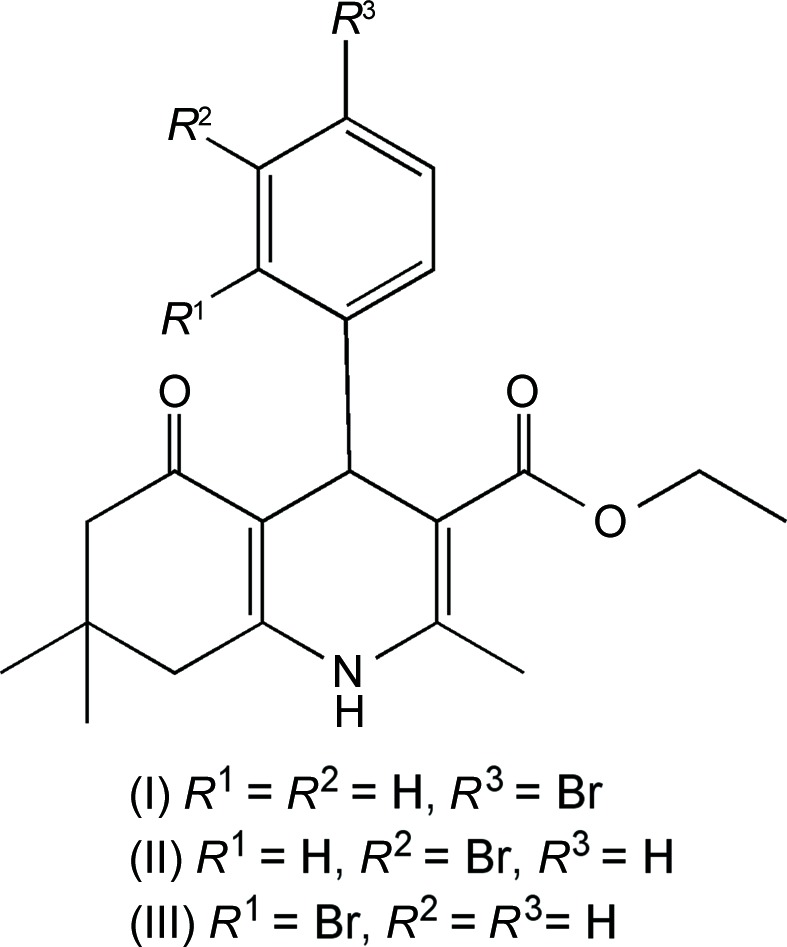

Three quinolone compounds were synthesized and crystallized in an effort to study the structure–activity relationship of these calcium-channel antagonists. In all three quinolones, viz. ethyl 4-(4-bromophenyl)-2,7,7-trimethyl-5-oxo-1,4,5,6,7,8-hexahydroquinoline-3-carboxylate, (I), ethyl 4-(3-bromophenyl)-2,7,7-trimethyl-5-oxo-1,4,5,6,7,8-hexahydroquinoline-3-carboxylate, (II), and ethyl 4-(2-bromophenyl)-2,7,7-trimethyl-5-oxo-1,4,5,6,7,8-hexahydroquinoline-3-carboxylate, (III), all C21H24BrNO3, common structural features such as a flat boat conformation of the 1,4-dihydropyridine (1,4-DHP) ring, an envelope conformation of the fused cyclohexanone ring and a bromophenyl ring at the pseudo-axial position and orthogonal to the 1,4-DHP ring are retained. However, due to the different packing interactions in each compound, halogen bonds are observed in (I) and (III). Compound (III) crystallizes with two molecules in the asymmetric unit. All of the prepared derivatives satisfy the basic structural requirements to possess moderate activity as calcium-channel antagonists.

Introduction

The 1,4-dihydropyridine (1,4-DHP) heterocycle comprises a large family of medicinally important compounds. The substructure has garnered the most attention as a class of calcium-channel antagonists working as slow calcium-channel blockers, which have been used in the treatment of angina pectoris and hypertension (Wishart et al., 2006 ▶). The examination of Hantzsch 1,4-dihydropyridine ester derivatives has produced more active and longer-acting agents than the prototypical nifedipine molecule (Triggle, 2003 ▶). Many other derivatives have been synthesized to yield compounds active as calcium-channel agonists or antagonists (Martin-Leon et al., 1995 ▶; Rose, 1990 ▶; Rose & Draeger, 1992 ▶). A fused cyclohexanone ring is one of the modifications to 1,4-DHP compounds and this class has been shown to have moderate calcium-channel antagonistic activity, as well as modest anti-inflammatory and stem-cell differentiation properties, and has been implicated in slowing neurodegenerative disorders (Tippier et al., 2014 ▶). Thus, further understanding of the structure–activity relationship of 1,4-DHP compounds and their derivatives will allow for the determination of off-target activity and the reduction of side effects. It has been proven that the flattened boat conformation of the 1,4-DHP ring is one factor that leads to higher calcium-channel activity (Linden et al., 2014 ▶). Atoms N1 and C4 of the 1,4-DHP ring can be marginally displaced from the mean plane of the boat (Linden et al., 2002 ▶). An aryl group in the 4-position of the 1,4-DHP ring is essential for optimal activity (Shaldam et al., 2014 ▶). One study showed that an aryl ring with halogen or other electron-withdrawing groups exhibits higher receptor-binding activity (Takahashi et al., 2008 ▶). On the 1,4-DHP ring, ester groups are usually substituted at the 3- and 5-positions. It has been suggested that at least one cis-ester is required for the calcium-channel antagonistic effect and hydrogen bonding to the receptor (Fossheim, 1986 ▶). In an effort to find more active calcium-channel antagonists in the 1,4-DHP genre, we have synthesized a series of 1,4-DHP fused-ring derivatives, i.e. hexahydroquinolones. In this paper, we report three structures which have bromine substituted at the para-, meta- and ortho-positions on the phenyl ring attached to the 1,4-DHP ring, viz. compounds (I)–(III).

Experimental

Synthesis and crystallization

An oven-dried 100 ml round-bottomed flask was charged with dimedone (0.757 g), ethyl acetoacetate (0.703 g), ytterbium(III) trifluoromethanesulfonate (0.170 g) and a magnetic stirrer bar. The mixture was then taken up in absolute ethanol (13.5 ml), capped, placed under an inert atmosphere of argon and stirred at room temperature for 20 min. Homologues of bromobenzaldehyde (1.0 g, 5.405 mmol) and a quantity of ammonium acetate (0.419 g) were added to the stirred solution, and stirring was continued at room temperature for a further 48 h. The progress of the reaction was monitored via thin-layer chromatography (TLC). Once the reaction was complete, excess solvent was removed via rotary evaporation. The solution was then purified via silica-column chromatography. The products were recrystallized from hexane and ethyl acetate (1:4 v/v) as white to light-yellow crystalline solids [for (I): yield 1.91 g, 4.57 mmol, 84.00%; for (II): yield 1.86 g, 4.45 mmol, 82.30%; for (III): yield 1.45 g, 3.466 mmol, 63.76%]. Analytical samples of the products were again recrystallized from a minimum of warm hexane and ethyl acetate (1:4 v/v), to which hexane was added dropwise to a faint opalescence, and slow evaporation produced diffraction-quality crystals as white to light-yellow crystalline solids.

Characterization information

Melting points were determined in open capillary tubes with a Mel-Temp melting point apparatus (200 W) and are uncorrected. Structures were confirmed with 1H and 13C NMR, and mass spectroscopy. 1H NMR spectra were obtained in chloroform-d 1 using a Bruker AMX 400 MHz spectrometer. Chemical shifts are reported as p.p.m. relative to tetramethylsilane (TMS). LC–MS (liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry) data were obtained using a Waters LCT Premier XE series spectrometer.

Compound (I). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.31 (d, J = 8.28 Hz, 2H), 7.20 (d, J = 8.28 Hz, 2H), 6.01 (bs, 1H), 5.02 (s, 1H), 4.05 (q, J = 7.03 Hz, 2H), 2.38 (s, 3H), 2.21 (s, 2H), 2.17 (s, 2H), 1.20 (t, J = 7.15 Hz, 3H), 1.08 (s, 3H), 0.93 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 195.42, 167.19, 148.01, 146.07, 143.60, 130.96, 129.89, 119.82, 111.90, 105.72, 59.94, 50.69, 41.14, 36.33, 32.75, 29.44, 27.15, 19.49, 14.23. HRMS calculated for C21H24BrNO3: 418.1018; found: 418.1024. MS, m/z = 418 ([M + 1] 100), 419 ([M + 2] 10), 420 ([M + 3] 100). M.p. 527–528 K. TLC [SiO2, hexane–EtOAc (3:2 v/v)]: R F = 0.19.

Compound (II). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.41 (s, 1H), 7.26 (d, J = 7.53 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (d, J = 8.53 Hz, 1H), 7.07 (t, J = 7.78 Hz, 1H), 6.09 (bs, 1H), 5.03 (s, 1H), 4.07 (m, J = 7.15 Hz, 2H), 2.38 (s, 3H), 2.31 (s, 2H), 2.22 (s, 2H), 1.21 (t, J = 7.15 Hz, 3H), 1.09 (s, 3H), 0.96 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 195.39, 167.15, 149.30, 148.24, 143.79, 131.09, 129.17, 126.97, 122.10, 111.71, 105.60, 59.96, 50.69, 41.12, 36.64, 32.78, 29.40, 27.22, 19.51, 14.21. HRMS calculated for C21H24BrNO3: 418.1018; found: 418.0979. MS, m/z = 418 ([M + 1] 100), 419 ([M + 2] 90). M.p. 508–509 K. TLC [SiO2, hexane–EtOAc (3:2 v/v)]: R F = 0.12.

Compound (III). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.44 (dd, J = 7.91 Hz, 1H), 7.37 (dd, J = 7.78 Hz, 1H), 7.16 (tt, J = 7.53 Hz, 1H), 6.94 (tt, J = 7.91 Hz, 1H), 5.92 (bs, 1H), 5.37 (s, 1H), 4.08 (m, J = 7.15 Hz, 2H), 2.32 (s, 3H), 2.30 (s, 2H), 2.19 (s, 2H), 1.18 (t, J = 7.03 Hz, 3H), 1.08 (s, 3H), 0.96 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 195.30, 167.44, 148.04, 145.88, 143.22, 133.08, 132.03, 127.49, 126.97, 123.38, 111.74, 105.86, 59.84, 50.69, 41.29, 37.98, 32.58, 29.28, 27.38, 19.49, 14.36. HRMS calculated for C21H24BrNO3: 418.1018; found: 418.1037. MS: m/z = 417 ([M] 100), 418 ([M + 1] 100), 419 ([M + 2] 30). M.p. 473–477 K. TLC [SiO2, hexane–EtOAc (3:2 v/v)]: R F = 0.23.

Refinement

Crystal data, data collection and structure refinement details are summarized in Table 1 ▶. The methyl H atoms were constrained to an ideal geometry, with C—H = 0.98 Å and U iso(H) = 1.5U eq(C), and were allowed to rotate freely about their C—C bonds. The remaining C-bound H atoms were placed in calculated positions, with C—H = 0.95–1.00 Å, and refined as riding, with U iso(H) = 1.2U eq(C). The positions of the amine H atoms were determined from difference Fourier maps and refined freely along with their isotropic displacement parameters. Two low-angle reflections of (I) and four of (III) were omitted from the refinement because their observed intensities were much lower than the calculated values as a result of being partially obscured by the beam stop.

Table 1. Experimental details.

For all structures: C21H24BrNO3, M r = 418.32, Z = 8. Experiments were carried out at 100 K with Mo Kα radiation using a Bruker SMART BREEZE CCD area-detector diffractometer. Absorption was corrected for by multi-scan methods (SADABS; Bruker, 2008 ▶). H atoms were treated by a mixture of independent and constrained refinement.

| (I) | (II) | (III) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal data | |||

| Crystal system, space group | Orthorhombic, P b c n | Orthorhombic, P b c n | Monoclinic, P21/c |

| a, b, c (Å) | 18.0371 (4), 15.4309 (3), 14.2604 (3) | 17.0813 (5), 15.4877 (5), 14.2544 (5) | 14.5012 (18), 18.299 (2), 15.1952 (19) |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 107.5262 (15), 90 |

| V (Å3) | 3969.08 (14) | 3771.0 (2) | 3844.9 (8) |

| μ (mm−1) | 2.09 | 2.20 | 2.16 |

| Crystal size (mm) | 0.26 × 0.18 × 0.13 | 0.40 × 0.21 × 0.19 | 0.34 × 0.16 × 0.08 |

| Data collection | |||

| T min, T max | 0.909, 1.000 | 0.839, 1.000 | 0.866, 1.000 |

| No. of measured, independent and observed [I > 2σ(I)] reflections | 35271, 4558, 3391 | 55070, 5055, 4278 | 45465, 8935, 6859 |

| R int | 0.038 | 0.032 | 0.065 |

| (sin θ/λ)max (Å−1) | 0.650 | 0.684 | 0.653 |

| Refinement | |||

| R[F 2 > 2σ(F 2)], wR(F 2), S | 0.042, 0.101, 1.04 | 0.032, 0.084, 1.03 | 0.036, 0.081, 1.02 |

| No. of reflections | 4558 | 5055 | 8935 |

| No. of parameters | 243 | 243 | 485 |

| Δρmax, Δρmin (e Å−3) | 1.49, −1.21 | 1.31, −0.38 | 1.46, −0.47 |

Results and discussion

Both ethyl 4-(4-bromophenyl)-2,7,7-trimethyl-5-oxo-1,4,5,6,7,8-hexahydroquinoline-3-carboxylate, (I) (Fig. 1 ▶), and ethyl 4-(3-bromophenyl)-2,7,7-trimethyl-5-oxo-1,4,5,6,7,8-hexahydroquinoline-3-carboxylate, (II) (Fig. 2 ▶), crystallize in the orthorhombic space group Pbcn with one molecule in the asymmetric unit. The asymmetric unit of ethyl 4-(2-bromophenyl)-2,7,7-trimethyl-5-oxo-1,4,5,6,7,8-hexahydroquinoline-3-carboxylate, (III) (Fig. 3 ▶), is composed of two symmetry-independent molecules, (IIIA) and (IIIB), which crystallize in the monoclinic space group P21/c. All three compounds have very similar structural conformations, which accommodate the requirements for calcium-channel antagonists.

Figure 1.

The asymmetric unit of (I), showing the atom-labelling scheme. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level.

Figure 2.

The asymmetric unit of (II), showing the atom-labelling scheme. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level.

Figure 3.

The asymmetric unit of (III), showing the atom-labelling scheme. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level.

In all three structures, the 1,4-DHP ring is characterized by a shallow or flattened boat conformation, which is one of the factors that leads to higher calcium-channel activity. The boat conformation can be quantified by ring-puckering parameters (Cremer & Pople, 1975 ▶). An ideal boat would have θ = 90° and ϕ = n × 60°. Calculated using PLATON (Spek, 2009 ▶), the puckering parameters in (I) are Q = 0.196 (2) Å, θ = 106.5 (6)° and ϕ = 5.2 (8)° for the atom sequence N1–C2–C3–C4–C10–C9. The corresponding parameters for (II) are Q = 0.3014 (17) Å, θ = 107.1 (3)° and ϕ = 0.9 (3)°, while for (III), two sets were obtained as QA = 0.162 (3) Å, θA = 67.3 (10)° and ϕA = 197.5 (10)°, and QB = 0.279 (3) Å, θB = 106.9 (6)° and ϕB = 3.9 (6)° for molecules A and B, respectively. The shallowness of the boat conformation is indicated by the marginal displacements of atoms N1 and C4 from the mean plane (the base of the boat) defined by the two double bonds (C2=C3 and C10=C9). The deviation of atom N1 from the base of the boat is generally smaller, between 0.00 and 0.19 Å, while the deviation of atom C4 is most frequently found around 0.3 Å (Linden et al., 2004 ▶, 2005 ▶). These are also observed in the title compounds: the deviations of atom N1 are 0.095 (3), 0.142 (2), 0.047 (3) and 0.134 (3) Å for (I), (II), (IIIA) and (IIIB), respectively; and the deviations of atom C4 are 0.235 (4), 0.365 (2), 0.207 (4) and 0.336 (4) Å for (I), (II), (IIIA) and (IIIB), respectively. The sum of the absolute values of the internal ring torsion angles is also considered a quantitative measure of the ‘flatness’ of the 1,4-DHP ring (Rowan & Holt, 1995 ▶). A flattened or unpuckered ring shows a sum of 0 and 240° for an ideal boat conformation of the ring (Triggle et al., 1989 ▶). Here, this sum is 67.7 (9)° for (I), 104.3 (5)° for (II), 55.8 (9)° for (IIIA) and 96.5 (8)° for (IIIB), indicating flattened boat conformations, compared with a sum of 72° for nifedipine, the known standard for 1,4-DHPs.

The relationship between the 1,4-DHP pyridine ring and the aryl group attached at the C4 position is another key factor in the 1,4-DHP structure–activity relationship. It has been reported that the pseudo-axial position of the aryl ring is essential for pharmacological activity (Langs et al., 1987 ▶). In the title compounds, the bromophenyl rings are almost orthogonal to the base of the 1,4-DHP ring defined by atoms C2, C3, C10 and C9, with dihedral angles between the mean planes (plane C2/C3/C10/C9 to plane C17–C22) of 86.32 (8), 88.46 (5), 99.37 (8) and 89.36 (9)° for (I), (II), (IIIA) and (IIIB), respectively. Another quantitative descriptive factor is the pseudo-torsion angle between the N1⋯C4 axis and the bond in the phenyl group directly above the 1,4-DHP ring [C17—C18 in compounds (I) and (II), and C17—C22 in compound (III)]. The N1⋯C4—C17—C18 pseudo-torsion angles are −6.75 (19) and 7.14 (17)° for (I) and (II), respectively. The corresponding pseudo-torsion angles in (III) show an even more orthogonal configuration, as the values are −2.0 (3) and −3.3 (3)° for (IIIA) and (IIIB), respectively. The ortho-bromo group is placed in a synperiplanar orientation with respect to the C4—H bond. Such an orientation has been observed in other ortho-substituted phenyl rings in 4-aryl-1,4-DHP compounds (Linden et al., 2004 ▶). It is worth noting that, although meta-NO2 substitution has been reported to be synperiplanar to the H atom on C4 (Morales et al., 1996 ▶), the meta-Br in (II) is in an antiperiplanar position. As in other reported ortho-substituted structures, compound (III) has the Br pointing away from the 1,4-DHP ring.

Due to the electron delocalization of the conjugate system, each ester group is coplanar with the mean plane of the 1,4-DHP ring and at a cis orientation to the adjacent endocyclic double bond. The planarity extends out through the ester chains in (I) and (II). However, in (III), because of the different packing pattern, the end methyl group in (IIIA) is curled up in the direction of the aryl group. As a result, it pushes the aryl group slightly away from the orthogonal position, thus making the dihedral angle between the 1,4-DHP ring and the aryl ring the most strongly deviating from 90°: 99.37 (8)° in (IIIA) versus 89.36 (9)° in (IIIB).

Again, Cremer & Pople’s ring puckering parameters can be used to quantify the conformations of the fused cyclohexanone rings. In all three compounds, the cyclohexanone rings adopt the envelope conformation, which ideally would have θ = 54.7° (or θ = 125.3° in the case of an absolute configuration change) and ϕ = n × 60°. For (I), the puckering parameters are Q = 0.447 (3) Å, θ = 57.4 (4)° and ϕ = 178.6 (4)° for the atom sequence C5–C10. For the same atom sequence in (II), (IIIA) and (IIIB), the corresponding puckering parameters are Q = 0.4595 (18) Å, θ = 59.4 (2)° and ϕ = 122.0 (3)° for (II), Q = 0.462 (3) Å, θ = 122.5 (4)° and ϕ = 2.9 (4)° for (IIIA), and Q = 0.477 (3) Å, θ = 59.4 (4)° and ϕ = 183.4 (4)° for (IIIB). All these parameters are very close to those of the ideal envelope conformation. Because of the almost perfect envelope conformation, atom C7 stands out from the plane formed by the rest of the atoms in the ring and lies on the same side of the ring plane as the C4-aryl ring. It is also interesting that the axial methyl group on C7 is almost synperiplanar to the bond that connects atom C4 to the aryl ring. The relationship can be shown by the C11—C7⋯C4—C17 pseudo-torsion angle, which is 13.86 (17)° for (I), 4.51 (13)° for (II), −16.2 (2)° for (IIIA) and 5.5 (2)° for (IIIB).

One feature which has not been reported previously for this type of structure is intermolecular halogen bonding between Br and the ester carbonyl O atom. A halogen bond is defined as a short C—X⋯O—Y interaction, where the X⋯O distance is less than or equal to the sums of the respective van der Waals radii (3.37 Å for Br⋯O), with the C—X⋯O angle ≃ 165° and the X⋯O—Y angle ≃ 120° (Auffinger et al., 2004 ▶). Although (II) has an X⋯O distance of 3.4837 (14) Å, which is only slightly longer than the sum of the van der Waals radii, the angles of 166.17 (13)° for Br1⋯O2—C14ii and 77.24 (6)° for C19—Br1⋯O2ii are out of the range for halogen bonds. Also in (III), the distance of Br1B⋯O2A at 4.048 (2) Å is out of halogen bond range. However, the Br⋯O distance is 3.1976 (18) Å in (I), with C20—Br1⋯O2iii = 152.24 (9)° and Br1⋯O2iii—C14iii = 111.06 (15)°, while in (III), Br1A⋯O2B = 3.1764 (18) Å and the angles are Br1A⋯O2B—C14B = 106.79 (16)° and C18A—Br1A⋯O2B = 160.65 (8)° [symmetry codes: (ii) −x +  , y −

, y −  , z; (iii) x −

, z; (iii) x −  , −y +

, −y +  , −z + 1]. These values are within the range for halogen bonds. Halogen bonding has been known for decades and has been found in biological systems, where the halogen acts as a Lewis acid and the interacting atom can be any electron-donating entity. For example, in addition to the backbone carbonyl O atom as the most prominent Lewis base involved in halogen bonds, hydroxy and carboxyl substituents in the side-chain groups can also form halogen bonds in protein-binding sites (Wilcken et al., 2013 ▶). The possibility of halogen bonding from Br in these three compounds needs to be considered during the study of their structure–activity relationships.

, −z + 1]. These values are within the range for halogen bonds. Halogen bonding has been known for decades and has been found in biological systems, where the halogen acts as a Lewis acid and the interacting atom can be any electron-donating entity. For example, in addition to the backbone carbonyl O atom as the most prominent Lewis base involved in halogen bonds, hydroxy and carboxyl substituents in the side-chain groups can also form halogen bonds in protein-binding sites (Wilcken et al., 2013 ▶). The possibility of halogen bonding from Br in these three compounds needs to be considered during the study of their structure–activity relationships.

In all three compounds, hydrogen bonds are formed between the N—H group of one molecule and the carbonyl O atom in the cyclohexanone ring of another molecule (Tables 2 ▶, 3 ▶ and 4 ▶). These hydrogen bonds link the molecules into extended chains running along the c axis in both (I) and (II), but along the a axis in (III) (Figs. 4 ▶, 5 ▶ and 6 ▶). In compound (I), the largest difference hole of −1.21 e Å−3, which is 0.68 Å from atom Br1, may indicate a slight disorder of the Br atom.

Table 2. Hydrogen-bond geometry (Å, °) for (I) .

| D—H⋯A | D—H | H⋯A | D⋯A | D—H⋯A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1—H1⋯O1i | 0.89 (3) | 1.94 (3) | 2.812 (2) | 168 (3) |

Symmetry code: (i)  .

.

Table 3. Hydrogen-bond geometry (Å, °) for (II) .

| D—H⋯A | D—H | H⋯A | D⋯A | D—H⋯A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1—H1⋯O1i | 0.86 (2) | 2.05 (2) | 2.8896 (19) | 166 (2) |

Symmetry code: (i)  .

.

Table 4. Hydrogen-bond geometry (Å, °) for (III) .

| D—H⋯A | D—H | H⋯A | D⋯A | D—H⋯A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1B—H1B⋯O1A i | 0.80 (3) | 2.02 (3) | 2.818 (3) | 174 (3) |

| N1A—H1A⋯O1B ii | 0.83 (3) | 2.07 (3) | 2.884 (3) | 165 (2) |

Symmetry codes: (i)  ; (ii)

; (ii)  .

.

Figure 4.

Part of the crystal structure of (I), showing the formation of chains of molecules running along the c axis. Hydrogen bonds are indicated by dashed lines. For the sake of clarity, H atoms not involved in hydrogen bonding have been omitted.

Figure 5.

Part of the crystal structure of (II), showing the formation of chains of molecules running along the c axis. Hydrogen bonds are indicated by dashed lines. For the sake of clarity, H atoms not involved in hydrogen bonding have been omitted.

Figure 6.

Part of the crystal structure of (III), showing the formation of chains of molecules running along the a axis. Hydrogen bonds are indicated by dashed lines. For the sake of clarity, H atoms not involved in hydrogen bonding have been omitted.

In conclusion, the structures reported here demonstrate that the usually observed conformational features have been conserved in cyclohexanone-fused 1,4-DHP derivatives. As a promising base structure for calcium-channel antagonists, different substitutions and more structural modifications are being carried out in our group; progress will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Crystal structure: contains datablock(s) I, II, III, global. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229614015617/sf3233sup1.cif

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) I. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229614015617/sf3233Isup2.hkl

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) II. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229614015617/sf3233IIsup3.hkl

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) III. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229614015617/sf3233IIIsup4.hkl

CML file for (I). DOI: 10.1107/S2053229614015617/sf3233Isup5.cml

CML file for (II). DOI: 10.1107/S2053229614015617/sf3233IIsup6.cml

CML file for (III). DOI: 10.1107/S2053229614015617/sf3233IIIsup7.cml

Acknowledgments

SS, CL and NRN thank the National Institutes of Health for grants NINDS P20RR015583 Center for Structural and Functional Neuroscience (CSFN) and P20RR017670 Center for Environmental Health Sciences (CEHS). NRN also thanks the University of Montana Grant Program (NN).

Footnotes

Supporting information for this paper is available from the IUCr electronic archives (Reference: SF3233).

References

- Auffinger, P., Hays, F. A., Westhof, E. & Ho, P. S. (2004). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 101, 16789–16794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bruker (2008). APEX2, SAINT and SADABS Bruker AXS Inc., Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

- Cremer, D. & Pople, J. A. (1975). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 97, 1354–1358.

- Dolomanov, O. V., Bourhis, L. J., Gildea, R. J., Howard, J. A. K. & Puschmann, H. (2009). J. Appl. Cryst. 42, 339–341.

- Fossheim, R. (1986). J. Med. Chem. 29, 305–307. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Langs, D. A., Strong, P. D. & Triggle, D. J. (1987). Acta Cryst. C43, 707–711.

- Linden, A., Şafak, C. & Aydın, F. (2004). Acta Cryst. C60, o711–o713. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Linden, A., Şafak, C. & Kismetlı, E. (2002). Acta Cryst. C58, o436–o438. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Linden, A., Safak, C. & Simsek, R. (1998). Acta Cryst. C54, 879–882.

- Linden, A., Şimşek, R., Gündüz, M. & Şafak, C. (2005). Acta Cryst. C61, o731–o734. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Martin-Leon, N., Quinteiro, M., Seoane, C., Soto, J., Mora, A., Suarez, M., Ochoa, E., Morales, A. & Bosque, J. (1995). J. Heterocycl. Chem. 32, 235–238.

- Morales, A. D., García-Granda, S., Navarro, M. S., Diviú, A. M. & Pérez-Barquero, R. E. (1996). Acta Cryst. C52, 2356–2359.

- Rose, U. (1990). Arch. Pharm. 323, 281–286. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rose, U. & Draeger, M. (1992). J. Med. Chem. 35, 2238–2243. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rowan, K. R. & Holt, E. M. (1995). Acta Cryst. C51, 2554–2559.

- Shaldam, M., Elhamamsy, M., Esmat, Eman. & El-Morselhy, T. (2014). ISRN Med. Chem. pp. 1–14.

- Sheldrick, G. M. (2008). Acta Cryst. A64, 112–122. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Spek, A. L. (2009). Acta Cryst. D65, 148–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, D., Oyunzul, L., Onoue, S., Ito, Y., Uchida, S., Simsek, R., Gunduz, M. G., Safak, C. & Yamada, S. (2008). Biol. Pharm. Bull. 31, 473–479. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tippier, P., Labby, K., Hawker, D., Mataka, J. & Silverman, R. (2014). J. Med. Chem. 56, 3121–3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wilcken, R., Zimmermann, M. O., Lange, A., Joerger, A. C. & Boeckler, F. M. (2013). J. Med. Chem. 56, 1363–1388. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wishart, D. S., Knox, C., Guo, A. C., Shrivastava, S., Hassanali, M., Stothard, P., Chang, Z. & Woolsey, J. (2006). Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 668–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Triggle, D. J. (2003). Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 23, 293–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Triggle, D. J., Langs, D. & Janis, R. (1989). Med. Res. Rev. 9, 123–180. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Crystal structure: contains datablock(s) I, II, III, global. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229614015617/sf3233sup1.cif

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) I. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229614015617/sf3233Isup2.hkl

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) II. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229614015617/sf3233IIsup3.hkl

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) III. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229614015617/sf3233IIIsup4.hkl

CML file for (I). DOI: 10.1107/S2053229614015617/sf3233Isup5.cml

CML file for (II). DOI: 10.1107/S2053229614015617/sf3233IIsup6.cml

CML file for (III). DOI: 10.1107/S2053229614015617/sf3233IIIsup7.cml