Abstract

Summary:

Developing countries have been attracting more international patients by building state-of-the-art facilities and offering sought-after healthcare services at a fraction of the cost of the US healthcare system. These price differentials matter most for elective procedures, including cosmetic surgeries, which are paid for out of pocket. It is unclear how this rise in medical tourism will affect the practice of plastic surgery, which encompasses a uniquely large number of elective procedures. By examining trends in the globalization of the cosmetic surgery market, we can better understand the current situation and what plastic surgeons in the United States can expect. In this article, we explore both domestic and foreign factors that affect surgical tourism and the current state of this industry. We also discuss how it may affect the practice of cosmetic surgery within the United States.

The cost of healthcare in the United States has become an increasingly hot topic. American politicians and economists debate over how best to curb the rising costs and improve access while maintaining quality. Although the domestic financial burden weighs on the minds of plastic surgeons, it has become a driving force behind the international medical tourism industry. Research has shown that the number of American patients interested in and actually traveling abroad for medical services is increasing.1 Lower- and middle-income countries have begun to capitalize on the comparatively wealthier citizens of Western nations who want to obtain discounted health services. These developing nations build hospitals and court highly trained physicians to attract foreign patients and get a piece of what has become a multibillion dollar industry. Cosmetic surgery centers are also appearing in medical tourism destinations. They offer procedures that are elective, paid for out of pocket, and nonurgent at a fraction of American prices, making them especially well suited for medical travel.

Medical tourism is expected to grow and capture more patients from developed countries including the United States, contributing to the globalization of the cosmetic surgery market. How this will affect the American practice of plastic surgery, a specialty dominated by elective procedures, is uncertain. In this article, we examine the rise and transformation of the medical tourism industry, foreign and domestic forces that influence cosmetic surgical tourism, and the pros and cons for all involved parties. The implications of recent healthcare changes within the United States for the field of cosmetic surgery are also discussed. Understanding the current state medical tourism as it relates to the field of American plastic surgery can help prepare plastic surgeons in the United States to compete and excel in the global arena.

HISTORY AND TRANSFORMATION OF MEDICAL TRAVEL

Traveling in search of medical care is not a new phenomenon. Since antiquity, people with means have traveled to seek expertise, technologies, and environments for healing and recuperation. For centuries, Europeans have flocked to spas famous for their restorative waters, and peoples of the Middle East have journeyed to the mineral-rich waters of the Dead Sea.2–4 Some royal or otherwise influential patients requested that renowned doctors come to them. James Marion Sims (the father of gynecology) from South Carolina was sought by Empress Eugenie of France, the Duchess of Hamilton, and the Duchess of Austria to be their surgeon.5 In general, however, past tourists were traditionally wealthy patients from areas of less abundant or less advanced medical care who pursued higher quality care in areas with better technology or more temperate climates.3

Today’s medical tourists diverge from the historical pattern of health tourism in 3 main ways: there is a much larger number of them, they tend to travel from wealthy countries to developing countries (a reversal of flow), and they are motivated by different factors, namely, by lower costs.2–4,6 Patients are drawn abroad by newer (often unproven) procedures performed in some developing countries, the opportunity to circumvent long wait times, and the added bonus of a vacation.2–4,6 Most medical tourists travel on their own accord and pay out of pocket for health services, with one exception being “outsourced” patients sent by their insurers to receive treatment abroad.6 Blue Shield of California introduced its Access Baja HMO in 2000, an outsourcing plan that allowed members with employer-sponsored benefit to receive healthcare services from Blue Shield–approved providers in Tijuana, Mexico. This was the first cross-border health plan in the United States.7 Most medical tourists, however, tend to seek elective and cosmetic procedures, which is a primary reason why this industry could potentially have a great effect on plastic surgery within the United States.1,6

What initiated and enabled this transformation in international health travel? The answer is a combination of social, industrial, and economic developments in both lower income and developed countries. For one, the world has gotten smaller owing to more efficient air travel that enables more people to reach overseas locales. The internet has also facilitated medical tourism by providing consumers with access to information about foreign hospitals and accreditations, helping advertisements reach potential patients, and making it easier to find providers and book travel.6 The modernization of technology, medicine, and medical facilities in low-income countries that have become destinations has similarly fueled this transformation. Many have expanded their biomedical sectors and funding to attract more medical tourists. The vice president of the United Arab Emirates constructed Dubai Health Care City to entice tourists from the Middle East and elsewhere.3,6 Opened in 2002, Dubai Health Care City now attracts foreign and domestic patients and offers a comprehensive list of health services, including plastic surgery. Cosmetic procedures have become an integral part of medical tourism because they are not covered by insurance and the costs overseas are much lower.3

CURRENT STATE OF MEDICAL TOURISM AND TRENDS

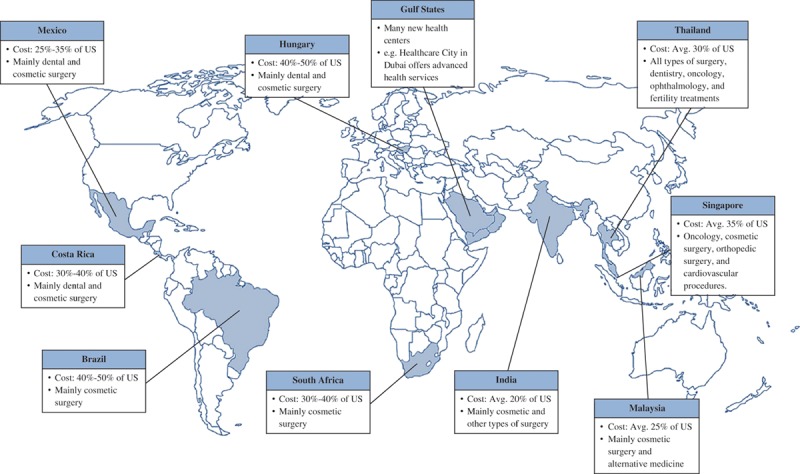

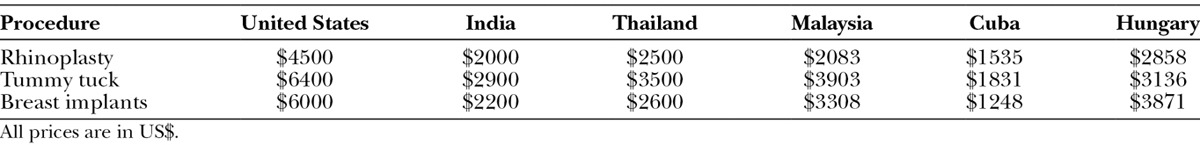

The number of patients traveling abroad today varies widely among reports (from 60,000 to 50 million medical tourists worldwide), in part due to differing definitions of the term “medical tourist.”6,8 Virtually all, however, agree that the industry is growing. In India alone, the number of tourists was predicted to rise from around 100,000 in 2002 to over 1 million in 2012.9 A 2008 poll of American consumers found that 39% would consider going to a foreign country for an elective procedure if the cost was half or less that in the United States and if the quality was guaranteed to be equal to or better than that in the United States.1 Figure 1 shows the top sites of medical tourism for American patients as well as the average price differentials and popular services that are offered. The same report predicted that the number of Americans traveling overseas for healthcare would rise from 750,000 in 2007 to over 8 million by 2013.1 It is clear that patients can save a lot of money by receiving treatment abroad, which is an especially important factor when deciding where to have elective surgery. Table 1 shows the typical pricing of common cosmetic procedures in the United States and select destination countries. Having an operation overseas is often less expensive than it is domestically even when airfare is included.1,6

Fig. 1.

Major destinations of American medical tourists, average cost relative to the US health system, and main services offered. Adapted with permission from Deloitte Development. Copyright 2012 Deloitte Development LLC.1 Adaptations are themselves works protected by copyright. So in order to publish this adaptation, authorization must be obtained both from the owner of the copyright in the original work and from the owner of copyright in the translation or adaptation.

Table 1.

Average Prices of Common Cosmetic Procedures in the United States and Select Medical Tourism Destinations6 in 2011

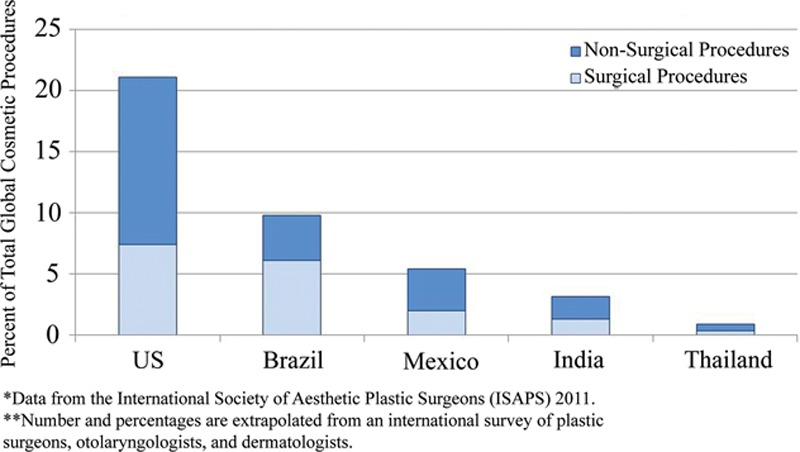

By now there are some established patterns of travel between departure and destination countries, which are often related to proximity, but also depend on what services a particular site offers.6 Mexico has long attracted dental and cosmetic surgery patients from the United States, whereas Thailand and India have emerged as forerunners in offering gender reassignment operations and cosmetic procedures, respectively, to Americans, Western Europeans, and Middle Easterners from oil-rich countries.6,10 Destination countries compete for market share in a number of ways, including finding a specialty niche (eg, gender reassignment surgery), advertising a lower price, attracting patients from nearby developed countries, or offering unique services or experiences.3 Figure 2 shows the percent of total global cosmetic surgery volume captured by the United States and by countries that attract medical tourists.

Fig. 2.

Percent of total global cosmetic procedures by country.11

Surgeon & Safari, a South African tourism company whose motto is “Privacy in Paradise,” offers a long list of cosmetic procedures, resort-like accommodations where patients stay during recovery, and various themed safaris.3,12 By venturing abroad for cosmetic surgery, patients can recuperate privately and then return home without anyone knowing that their trip involved a medical procedure. The allure of vacationing in an exotic, beautiful place mirrors historical healthcare tourism, in which tourists flocked to naturally therapeutic places such as mineral water spas.2–4 India, Costa Rica, South Africa, and other countries are also destinations of traditional tourism and attract patients who wish to combine medical travel with a vacation to an exotic, beautiful, and/or culturally rich locale.6

For countries trying to attract medical tourists from developed countries, the biggest challenge is convincing potential patients that they can offer care, expertise, facilities, and technology that are comparable to or better than the patients’ home countries.3 Americans, who are used to expensive healthcare, tend to be wary of the low prices and third world reputations of India, Thailand, and other destinations; quality and safety are major concerns of those considering procedures abroad.1,3 Accreditation by international or national organization is one way to reassure potential clientele. The Joint Commission International, a branch of the United States Joint Commission, evaluates the quality of hospitals around the world and accredits those that meet its standards, including 22 in India and over 30 in Thailand.1,6,13 Another method of demonstrating quality is to establish a formal connection between hospitals and American universities or providers (eg, Johns Hopkins Singapore International Medical Center at Tan Tock Seng Hospital in Singapore, which is staffed by Singaporeans and managed by Johns Hopkins Medicine International).6,14 Other hospitals recruit western-trained and certified physicians whose credentials are familiar to and trusted by American tourists.6 Most of these doctors come from developing countries, left to pursue training, and would not have returned except for the new opportunities and higher pay afforded by medical tourism.

India exemplifies these and other strategies for fostering medical tourism. Although modern technological centers are now emerging, India has long been regarded as being a developing country. Most Americans are more acquainted with images of crowded streets and children in need of vaccination than they are with the image of India as a booming center of biomedicine. However, its medical tourism industry, whose annual growth rate has been estimated at an astounding 30%, has blossomed in recent years owing to the breadth of procedures offered, modern technology, westernization of medical and surgical standards, low costs, attention to patients, and improvements in hospital management and organization.3,15 The last change led to better private hospitals and somewhat higher salaries that drew back many physicians from abroad.3 Tourism campaigns advertise the world-class facilities, doctors, and technology, though with little supporting evidence on quality and outcome indices.15 The Indian government actively supports medical tourism. To attract patients and expand an industry that is expected to bring in $2 billion in revenues, it introduced the M visa for medical tourists that lasts up to 1 year and has offered tax breaks to hospitals catering to tourists.6,9,15,16 The low cost of care resulting from inexpensive labor and virtual nonexistence of malpractice liability draws many patients seeking less costly elective procedures such as cosmetic surgery.3

ISSUES AND IMPLICATIONS

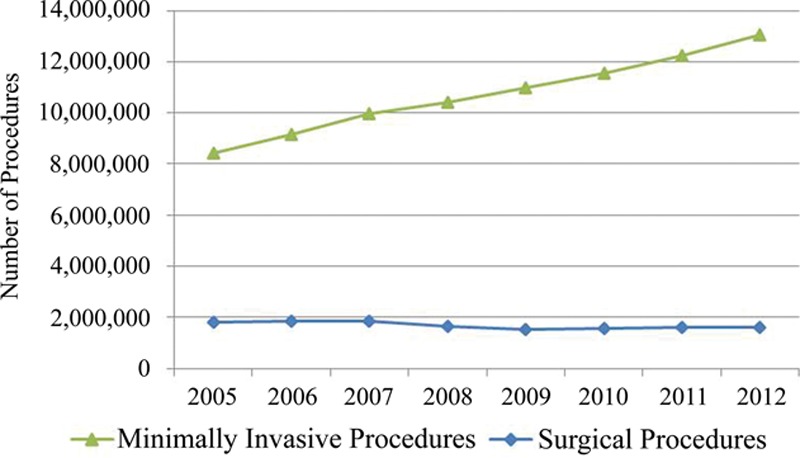

In contrast to the rapid expansion occurring in East Asia and elsewhere, American plastic surgery growth is curtailed by the high costs of healthcare and malpractice liability. According to a report from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS), the number of surgical cosmetic procedures dropped by 16% from 2000 to 2012, whereas minimally invasive procedures rose 137%.17 Figure 3 shows surgical and minimally invasive procedural volumes in the United States from the past 8 years. The decrease in cosmetic surgical procedures can be attributed to an increase in procedural malpractice premiums, surgeons’ unwillingness to perform high-risk procedures, and the stagnant economy, which affects patients’ decisions about cosmetic surgery.

Fig. 3.

Malpractice premiums have been steadily rising to cover the larger payouts to patients who file malpractice suits.19 Malpractice liability also leads to the practice of defensive medicine (ie, over utilization of diagnostic tests and other services to avoid malpractice lawsuits), which undermines cost reduction and efficiency, resulting in higher procedural costs in the United States relative to other countries. As Horton and Hollier20 recently stated, “cost-effective and quantity-conscious care provides no legal defense or financial benefit.” In response, some specialists are cutting back on high-risk procedures.19 The different growth rates of surgical and minimally invasive procedures shown in Figure 3 also reflect differences in demand for these procedures. Hoppe et al21 found that patients’ decisions to have cosmetic surgery are based on long-term planning, but their decisions to undergo minimally invasive procedures are made impromptu during good economic times. The drop in cosmetic surgical procedures after 2008 reflects the lasting effects that the recession had on consumers, which deterred them from planning large purchases. The economic recovery in recent years has led to growth in the number of minimally invasive procedures but is not yet stable enough to encourage growth in surgical procedures. These economic forces contribute to the decline in surgical procedure volume.

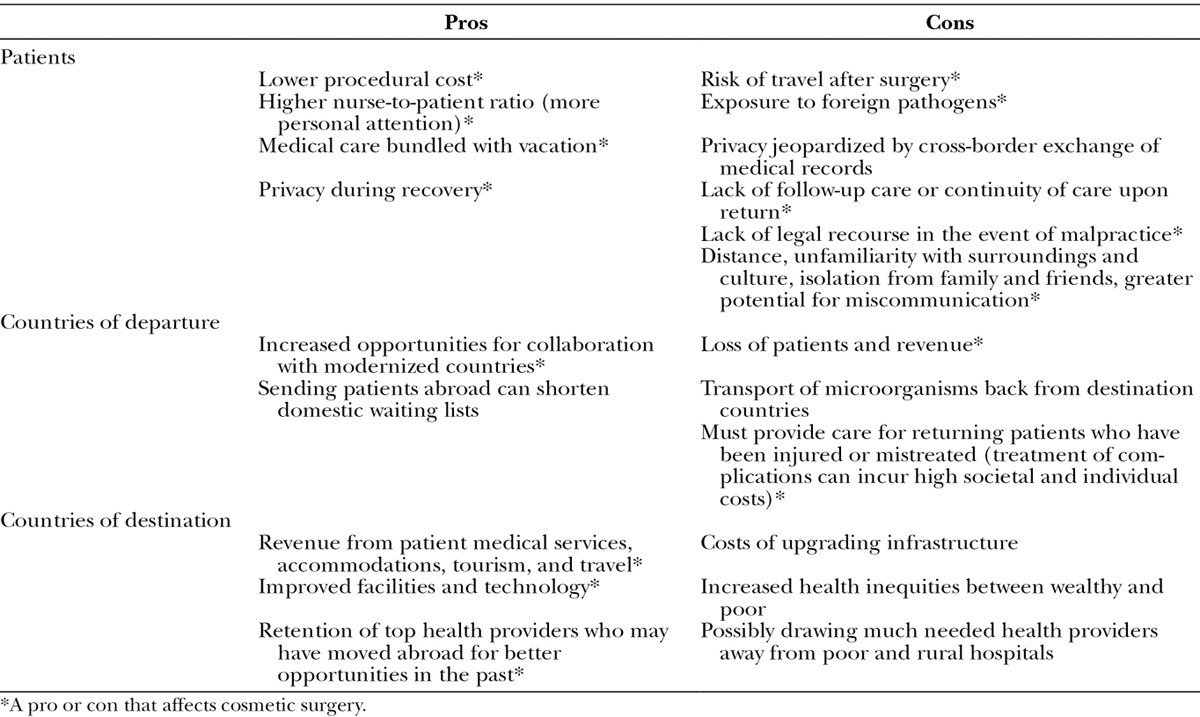

Despite the accreditation strategies, physical safety and legal protection of medical tourists are still an issue. Most destination countries have inadequate malpractice laws and offer no legal recourse to patients.2,15 Travel insurance is available for tourists (usually only those without preexisting conditions) to cover the costs of treatment for complications or dissatisfaction with surgical outcomes, which would otherwise be billed to the patient.6 This type of insurance could encourage more patients interested in cosmetic surgery to go overseas. Pros and cons of medical tourism for patients and for countries sending and receiving them can be found in Table 2. In addition to these, patients face the challenge of sifting through providers’ Web sites for information about safety, some of which downplay the risks: “In the hands of expert surgeons and world-class facilities like Apollo Cosmetic clinics, the risks are really minimal and the procedures are absolutely safe.”6,22 This type of misinformation is confounded by the lack of data on the quantity of patient traffic and quality of care in destination countries. American plastic surgeons and professional societies can help patients considering medical tourism by providing information about risks and counseling to help them make the optimal decision. The ASPS provides such information on their Web site, including risks and aspects of travel and follow-up care that patients should consider before going abroad.23

Table 2.

The Pros and Cons of Medical Tourism for Patients and Countries of Departure and Destinations2,3,6,8

CONCLUSIONS

All research suggests that medical tourism is a growing industry. More countries are building hospitals and courting patients, more physicians are moving to destinations of tourists, and each year, more patients are traveling. For plastic surgeons in the United States, this means that more potential patients will be going overseas and across borders where prices are lower and standards may be approaching those of the United States. The rapid globalization of the industry also marks a fundamental shift in the world’s perception of elective procedures: patients are becoming consumers and these medical services are being viewed as commodities.6 Economic forces, including supply, demand, and competition for market share, are affecting the global plastic surgery industry. Because the practice of medical travel does not seem to be going away in the foreseeable future, plastic surgeons in the United States must understand the international market and learn to compete in it.

There are 3 basic ways to retain American patients and compete with the low costs of cosmetic surgery abroad: lower domestic prices, provide superior care, or find a niche market. The first option is limited by the costs of living, supplies, and labor, which are generally higher in the United States than in countries that attract medical tourists. Depending on the rate of development in these countries and the rate that medical costs rise in the United States, their costs may approach those of the United States in the future. Connell,3 however, suggests that price differentials between medical tourist destinations and developed nations are growing, not shrinking. In the meantime, American plastic surgeons can strive to provide the best possible care, whereby justifying higher costs with quality. This can be done by offering a comprehensive array of procedures, improving patient satisfaction and the patient experience (ie, pre-, intra-, and postoperatively), and demonstrating leadership in the field through research and innovation. Plastic surgeons in the United States and organizations such as the ASPS can also counsel patients about the risks of going abroad that may be omitted from medical tourism Web sites. Finding a niche market essentially means finding a “sweet spot” of procedures that are profitable but have small enough price differentials that the expense of traveling overseas would not be offset by the savings. For example, if we assume airfare is $1000, going abroad for chin augmentation, which in 2012 cost $2480 on average in the United States, would not be worth it unless the procedure, accommodations, and other expenses totaled under $1480.

Medical tourism with respect to plastic surgery is not purely good or bad for patients or countries that send and receive them, as seen in Table 2. It is important as we move forward with international partnerships and collaboration to share the collective knowledge for providing high quality and cost-effective healthcare. As plastic surgery in developing countries advances, new opportunities for international, multicenter research arise. Collaborative efforts could also ameliorate the health inequities exacerbated by medical tourism, which has been criticized for treating health services as a commodity and undermining efforts to implement universal health coverage.2 Government subsidizing and promoting of medical tourism may indirectly exacerbate the existing health inequities. In India, hospitals catering to tourists receive tax breaks and low interest loans to build facilities that are largely unaffordable to the local people.9,15 Many fail to provide the free care mandated in return for these subsidies. In effect, the hospitals receive the financial benefits of charitable institutions but provide few or none of the public services.10,15 The economic boons of tourism also draw providers to the modern facilities and higher wages available in cities, which further lowers access to and quality of care in rural areas.2,9

There are gaps in the evidence and literature regarding medical tourism. Lunt et al6 identified what is perhaps the most important—the lack of data about the quality, safety, and risks involved with overseas care and surgery. Data regarding clinical outcomes and follow-up are also scarce, which is relevant to US plastic surgeons who must assume the postoperative care of patients who are treated abroad.6 Over a third of surveyed British plastic surgeons had seen patients with complications resulting from cosmetic surgery in a foreign country.24 Outcomes data would also help patients, who currently only have access to information on providers’ Web sites. What data are available are collected in nonstandardized ways, making them difficult to compare. For example, estimates of tourists vary widely due to different definitions of the label medical tourist. Future research should be directed toward closing these gaps in the literature to better illuminate the reality of cosmetic surgery tourism. To retain patients and be competitive in a global market, American plastic surgery must be vigilant of the changes in medical tourism and must adapt accordingly.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article. This study was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K24 AR053120. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The Article Processing Charge was waived at the discretion of the Editor-in-Chief.

REFERENCES

- 1.Keckley PH, Underwood HR. Medical Tourism: Consumers in Search of Value. Washington, DC: Deloitte Development; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnston R, Crooks VA, Snyder J, et al. What is known about the effects of medical tourism in destination and departure countries? A scoping review. Int J Equity Health. 2010;9:24. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-9-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connell J. Medical tourism: sea, sun, sand and … surgery. Tourism Manag. 2006;27:1093–1100. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weisz G. Historical reflections on medical travel. Anthropol Med. 2011;18:137–144. doi: 10.1080/13648470.2010.525880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Straughn JM, Jr, Gandy RE, Rodning CB. The core competencies of James Marion Sims, MD. Ann Surg. 2012;256:193–202. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318249ce3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lunt N, Smith R, Exworthy M, et al. Medical Tourism: Treatments, Markets and Health System Implications: A Scoping Review. Paris: OECD; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perry L. Blue Shield Initiates Quality Focus in Baja California with New Cross-border HMO. About Blue Shield: Newsroom 2000. Available at: https://www.blueshieldca.com/bsca/about-blue-shield/newsroom/access-baja-cross-border-hmo.sp. Accessed August 10, 2013.

- 8.Pashley H. Medical tourism presents opportunities and risks for patients. AORN. 2012;96:C6–C7. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2092(12)00723-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sengupta A. Medical tourism: reverse subsidy for the elite. Signs (Chic) 2011;36:312–319. doi: 10.1086/655910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burkett L. Medical tourism. Concerns, benefits, and the American legal perspective. J Leg Med. 2007;28:223–245. doi: 10.1080/01947640701357763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hackworth S. ISAPS International Survey on Aesthetic/Cosmetic Procedures Performed in 2011. International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 2012 Hanover, NH. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Surgeon & Safari: Surgery and Recuperation with Time to Heal Away from Public Scrutiny. 2013. Available at: http://www.surgeon-and-safari.co.za/index.html. Accessed July 10, 2013.

- 13.JCI; Accredited Organizations. 2013. Available at: http://www.jointcommissioninternational.org/jci-accredited-organizations/. Accessed August 12, 2013.

- 14.Johns Hopkins Singapore International Medical Centre. 2013.. Available at: http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/international/international_affiliations/asia_pacific/singapore_international_medical_centre.html. Accessed August 12, 2013.

- 15.Shetty P. Medical tourism booms in India, but at what cost? Lancet. 2010;376:671–672. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61320-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chinai R, Goswami R. Medical visas mark growth of Indian medical tourism. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:164–165. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.010307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Society of Plastic Surgeons. 2012 Cosmetic Plastic Surgery Statistics: Cosmetic Procedure Trends. American Society of Plastic Surgeons; 2013. Arlington Heights, IL: [Google Scholar]

- 18.American; Society of Plastic Surgeons. 2012 Quick Facts: Cosmetic and Reconstructive Plastic Surgery Trends. American Society of Plastic Surgeons; 2013. Arlington Heights, IL: [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mello MM, Studdert DM, DesRoches CM, et al. Effects of a malpractice crisis on specialist supply and patient access to care. Ann Surg. 2005;242:621–628. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000182957.54783.9a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horton JB, Hollier LH., Jr The current state of health care reform: the physicians’ burden. Aesthet Surg J. 2012;32:230–235. doi: 10.1177/1090820X11431978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoppe IC, Pastor CJ, Paik AM. An analysis of leading, lagging, and coincident economic indicators in the United States and its relationship to the volume of plastic surgery procedures performed. Ann Plast Surg. 2012;69:471–473. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31824a4393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Apollo; Hospitals. 2013. Available at: http://www.apollohospitals.com/international_patient_services/. Accessed August 10, 2013.

- 23.Medical Tourism. Patient and Consumer Information: Patient Safety. 2012 Available at: http://www.plasticsurgery.org/articles-and-galleries/patient-and-consumer-information/patient-safety/medical-tourism.html. Accessed August 12, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeevan R, Armstrong A. Cosmetic tourism and the burden on the NHS. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61:1423–1424. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]