Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Abstract

Background:

Surgeons have long debated the relative merits of vertical and inverted-T mammaplasties. These debates have centered on surgeons’ opinions. Without measurements, this controversy is unlikely to be resolved. This study compares these common techniques using a recently published measurement system. Such a study using measurements on photographs matched for size and orientation has not been previously published.

Methods:

A prospective group of women undergoing primary vertical mastopexies, augmentation/mastopexies, and reductions (n = 78) was compared with a retrospective group of women treated with inverted-T mastopexies, augmentation/mastopexies, and reductions (n = 35). Consecutive patients with photographs at least 3 months after surgery and no subsequent procedures were evaluated.

Results:

All patient groups demonstrated a significant elevation (P < 0.001) of the breast mound. Vertical mastopexy, but not inverted-T mastopexy, increased breast projection and upper pole projection (P < 0.008). Neither vertical nor inverted-T breast reduction significantly increased breast projection. Vertical breast reduction better preserved breast projection (P < 0.017) than the inverted-T technique. Vertical reduction significantly increased upper pole projection (P < 0.008), but inverted-T reduction did not. The inverted-T breast reduction caused greater breast constriction (reduced lower pole distance) than the vertical technique. Lower pole ratios were significantly higher for inverted-T patients (P < 0.01), indicating boxier lower poles.

Conclusions:

Photographic measurements of relevant breast parameters favor the vertical technique over the inverted-T technique and are consistent with anatomical considerations and clinical experience.

The new millennium has witnessed a challenge to the inverted-T technique, still popular in America,1 largely due to the work of Hall- Findlay.2 There are a growing number of surgeons who have abandoned the inverted-T procedure, including the author, impressed not only by reduced scarring but also by the improved shape provided by the vertical technique.3–9

In 2002, Rohrich10 considered whether limited-incision breast surgery represents a passing fad or emerging trend, pointing out that the literature offered no comparison of breast shape and contour between the inverted-T and limited-incision techniques. Nahabedian11 wrote an editorial critical of those who have relegated the inverted-T technique to obsolescence, memorably titled “Scar Wars.” Certainly, there is a level of conviction on each side of the debate. But what is the evidence?

Evaluation of changes in breast shape after surgery, including breast projection, upper pole fullness, and “bottoming-out,” has been limited by the lack of an accepted definition of these entities and no standardized system of measurements. Without measurements, there is likely to be no resolution of the controversy. The author has recently published such a system.3,12,13 The purpose of this study is to compare these procedures using measurements. Such a study, using breast measurements to compare relevant shape parameters for the 2 techniques, has not been previously published.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A prospective group of women undergoing a vertical mammaplasty with and without simultaneous implants (n = 78) was compared with a retrospective group of women treated with the inverted-T technique (n = 35). The label “breast reduction” is used for mammaplasties with resection weights of 300 g or more from at least 1 breast.13 All procedures were bilateral. Reconstructive patients were excluded. All implants were placed submuscularly and all were round and saline-filled (Mentor, Santa Barbara, Calif.).

Prospective Study

The prospective study group included consecutive women undergoing primary mastopexy, augmentation/mastopexy, breast reduction, or reduction plus implants from 2002 through 2007. Patients who were unavailable for follow-up photographs at least 3 months after surgery (11 patients) or patients who underwent another breast operation, except for scar revisions performed under local anesthesia, before postoperative photographs (2 patients) were excluded. The remaining 78 patients were evaluated, representing 85.7% of the primary procedures performed during this 5-year period.

All mammaplasties in the prospective study group were performed using the vertical technique with a medially based pedicle2 and intraoperative nipple positioning.13 All procedures were performed by the author at a state-licensed ambulatory surgery center. Institutional review board approval was obtained.

Retrospective Study

The retrospective study group included consecutive women undergoing primary mastopexy, mastopexy/augmentation, or breast reduction during the period 1996 through 2002. The same inclusion criteria were used. A total of 35 consecutive patients meeting these criteria were evaluated, representing 57.4% of primary procedures performed during this period. The excluded patients consisted of 25 patients without follow-up photographs at least 3 months after surgery and 1 patient whose arms were raised in the preoperative pictures, precluding comparative analysis.

All patients in the retrospective group were treated using the inverted-T technique for mastopexies and the inverted-T, inferior pedicle technique for breast reductions,14 limiting the vertical limb length to 5 cm. Similar to the vertical cases, the new nipple position was determined intraoperatively.13

Measurements

For the prospective group, standardized digital photographs,15 calibrated by having patients hold a ruler, were stored on the Canfield Mirror 7.1.1 program (Canfield Scientific, Fairfield, N.J.). This program matches images without distortion and assists in measurements and area calculations.3 Breast projection is measured along the plane of maximum postoperative breast projection. Upper pole projection is measured along a plane bisecting the level of maximum postoperative breast projection with the level of the sternal notch.3

For the retrospective group of patients treated before 2002, analog photographs were scanned into the same Mirror program. All photographs, analog and digital, were taken using the same Nikon 60-mm lens (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Calibration was performed using an average upper arm length of 32.5 cm.16

Illustrations

Illustrations were created using the Adobe Photoshop CS2 Version 9.0.2 and Illustrator CS2 Version 12.0.1 softwares (Adobe Systems, San Jose, Calif.) that provide a 2D rendering of the data based on actual mean breast dimensions.12,13 Illustrations of vertical and inverted-T breast reductions are provided in Figures 1 and 2. To conserve journal space, vertical and inverted-T mastopexies and augmentation/mastopexies are included in Supplemental Figures 1–4 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/PRSGO/A21).

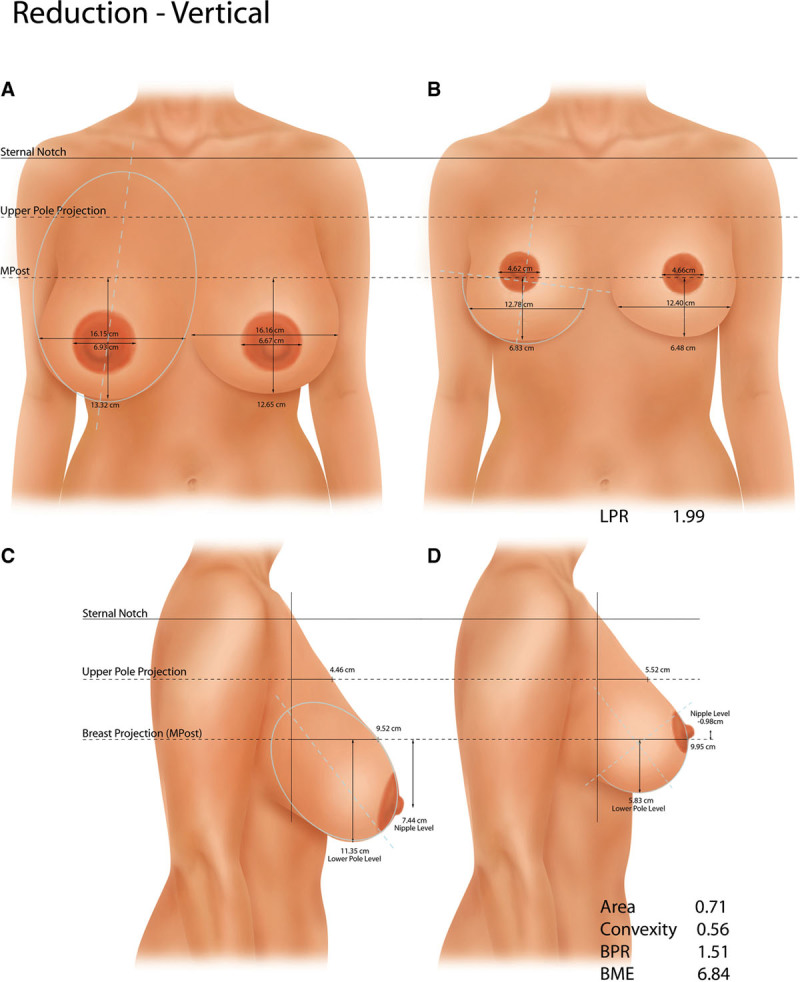

Fig. 1.

Breast shape before (A, C) and after (B, D) vertical breast reduction. Breast projection is maintained and upper pole projection is increased. The nipple is slightly (and not ideally) overelevated. The upper pole contour describes a mild ogee curve before surgery and is slightly convex (upper pole projection/breast projection) after surgery. An elliptical shape of the lower pole is reduced to a semicircle. The mean lower pole ratio is just under 2.0. Illustrations are based on actual mean breast measurements. BME indicates breast mound elevation; BPR, breast parenchymal ratio; LPR, lower pole ratio; MPost, maximum postoperative breast projection.

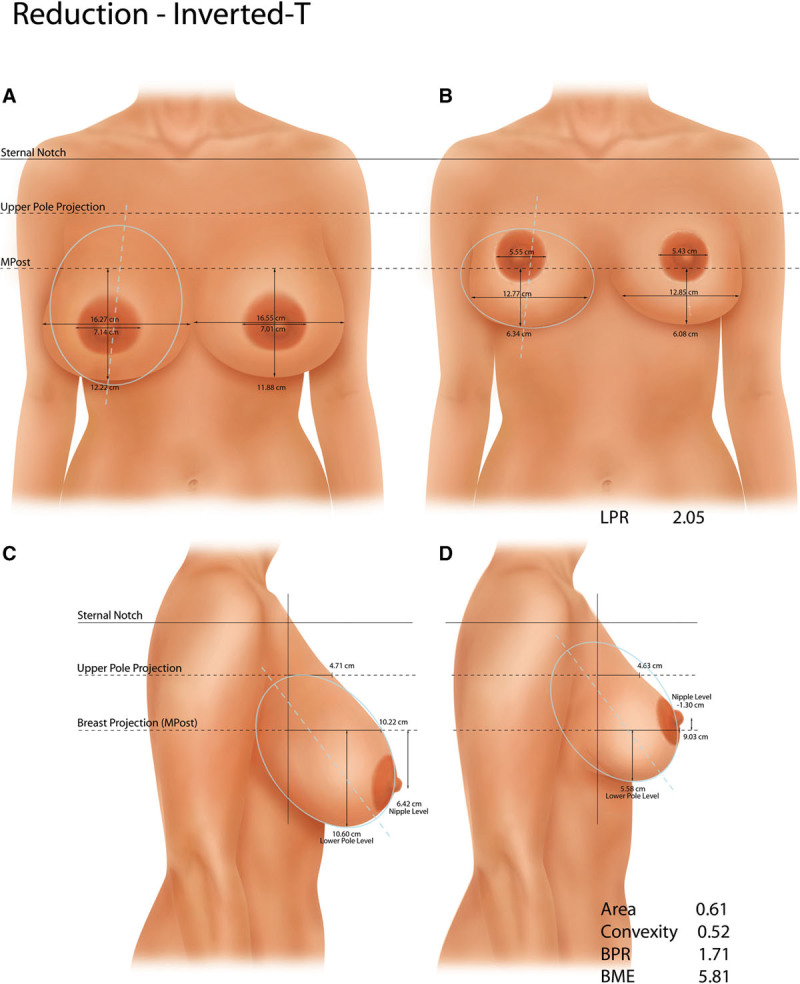

Fig. 2.

Breast shape before (A, C) and after (B, D) inverted-T breast reduction. Breast projection is reduced. Despite the use of the 5-cm rule for the vertical limb of the inverted-T, the nipple is overelevated. The mean lower pole ratio, 2.05, is slightly boxy. Illustrations are based on actual mean breast measurements. BME indicates breast mound elevation; BPR, breast parenchymal ratio; LPR, lower pole ratio; MPost, maximum postoperative breast projection.

Typical Patients

The “typical” patient is the patient from each procedure group with the most average before-and-after measurements based on z-scores. This statistical method was used to avoid selection bias in presenting representative results (Figs. 3 and 4).17

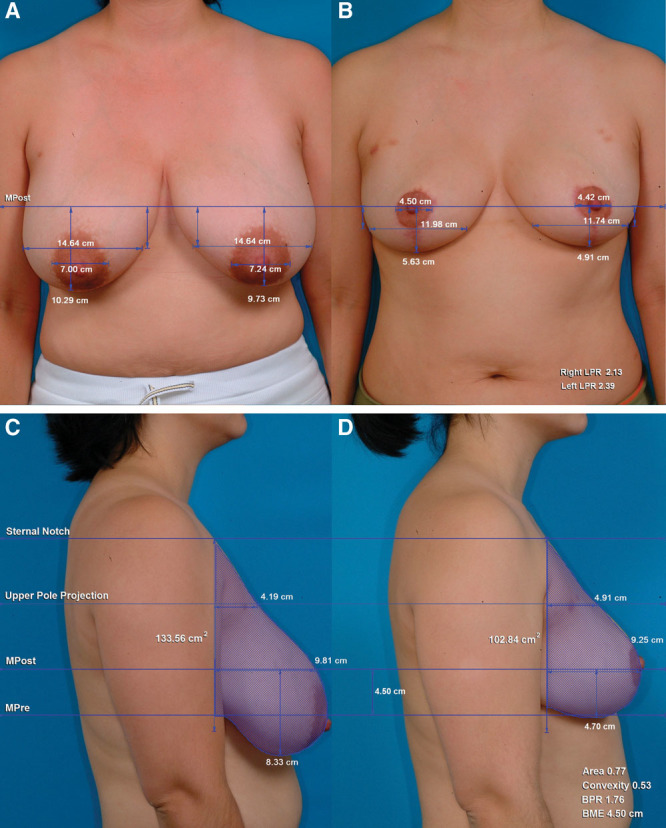

Fig. 3.

Orientation-matched views of the vertical reduction patient with the most average (lowest z-score) breast measurements. A 28-year-old woman before (A, C) and 6 mo after (B, D) a vertical breast reduction using a medial pedicle. Resection weights: right breast, 367 g; left breast, 464 g. Breast area is reduced 23% (shaded). Breast projection is slightly decreased in this patient and upper pole projection is slightly increased. The lower pole level and breast mound are elevated. Nipple position is appropriate. BME indicates breast mound elevation; BPR, breast parenchymal ratio; LPR, lower pole ratio; MPost, maximum postoperative breast projection.

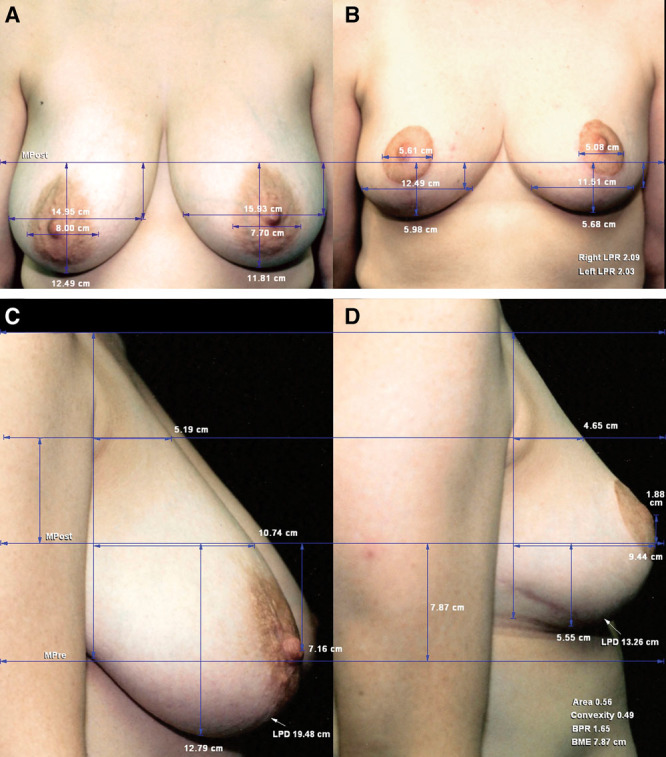

Fig. 4.

Orientation-matched views of the inverted-T reduction patient with the most average (lowest z-score) breast measurements. A 37-year-old woman before (A, C) and 22 mo after (B, D) an inverted-T, inferior pedicle breast reduction. Resection weights: right breast, 440 g; left breast, 510 g. Breast projection and upper pole projection are decreased. The lower pole distance is 6.2 cm shorter after surgery. The upper pole contour is linear before surgery and slightly concave after surgery, with an upturned nipple. BME indicates breast mound elevation; BPR, breast parenchymal ratio; LPD, lower pole distance; LPR, lower pole ratio; MPre, maximum preoperative breast projection; MPost, maximum postoperative breast projection.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS for Windows version 21.0 (SPSS, IBM, Armonk, N.Y.). The null hypothesis was no significant difference in shape parameters between mammaplasty techniques. One-way analysis of variance was used to compare means for continuously measured variables. Independent t tests were used to compare means between 2 groups, and paired t tests were used to compare preoperative and postoperative measurements. The “reduction plus implants” group was excluded from comparisons because of its small sample size (n = 2). A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant, except for multiple comparisons, for which a Bonferroni correction was used. z-scores were computed by subtracting the group mean and dividing by the group standard deviation for each measurement, converting the patient’s measurement into standard deviation units. An a priori power analysis was performed for the one-way analysis of variance. To achieve 80% power, with an α level of 0.05, sufficient to detect a moderate treatment effect (f = 0.40)18 comparing across 3 groups, 66 subjects would be needed.19

RESULTS

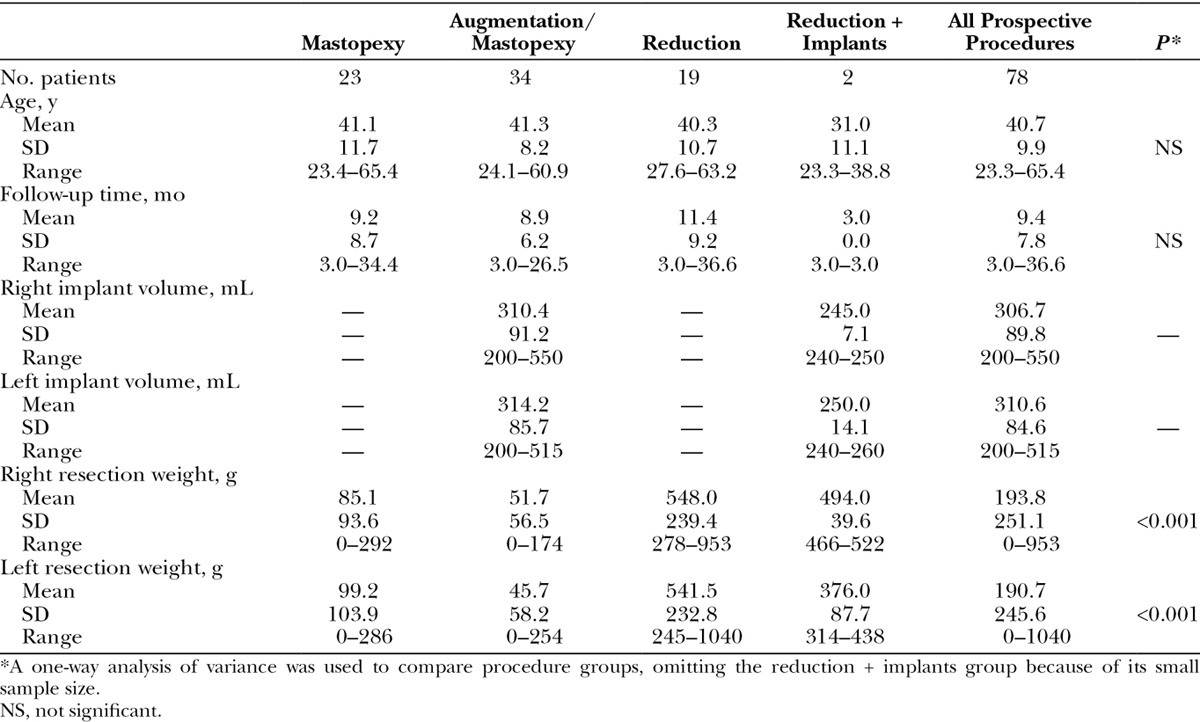

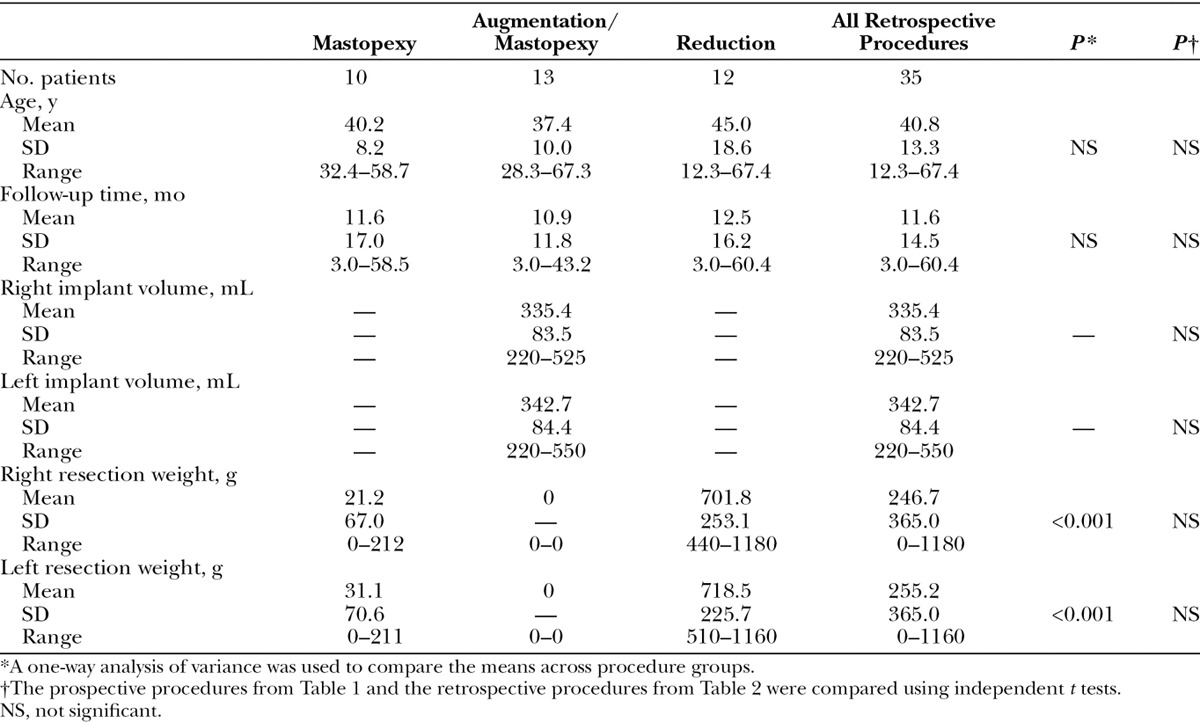

There were no significant differences between prospective and retrospective patient groups in mean age, follow-up time, implant volume, or resection weights (Tables 1 and 2). No significant differences in these parameters were detected comparing participants and patients who did not meet the inclusion criteria.

Table 1.

Patient Data for Prospective Study of Patients Treated with a Vertical Mammaplasty

Table 2.

Patient Data for Retrospective Study of Patients Treated with an Inverted-T Mammaplasty

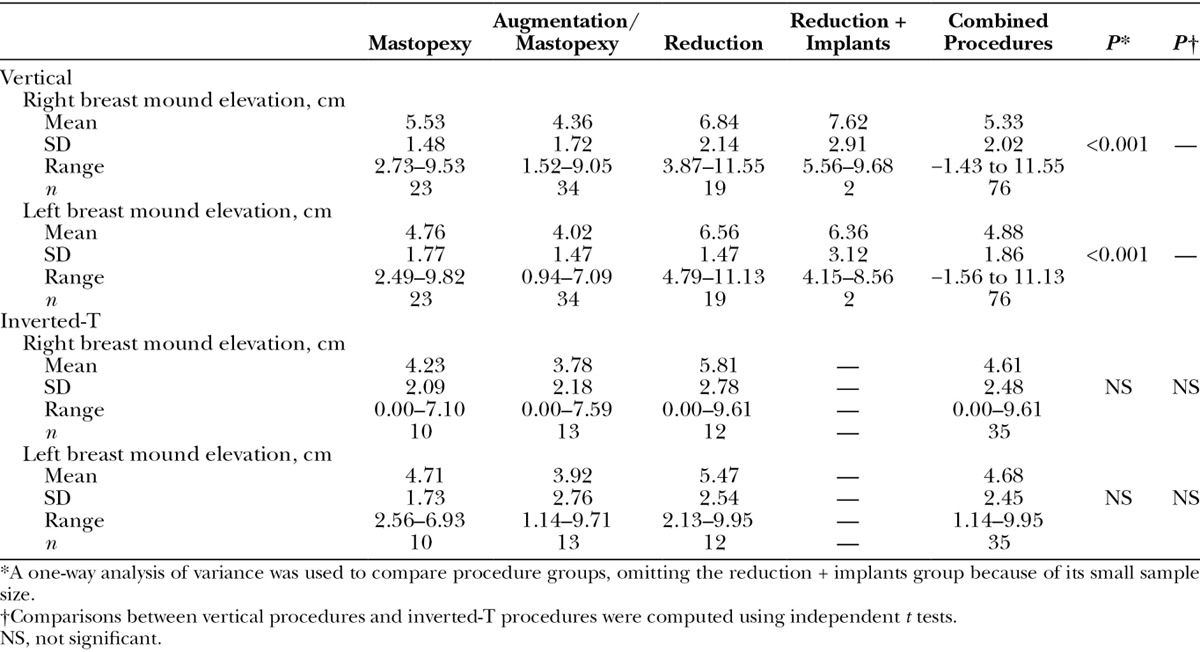

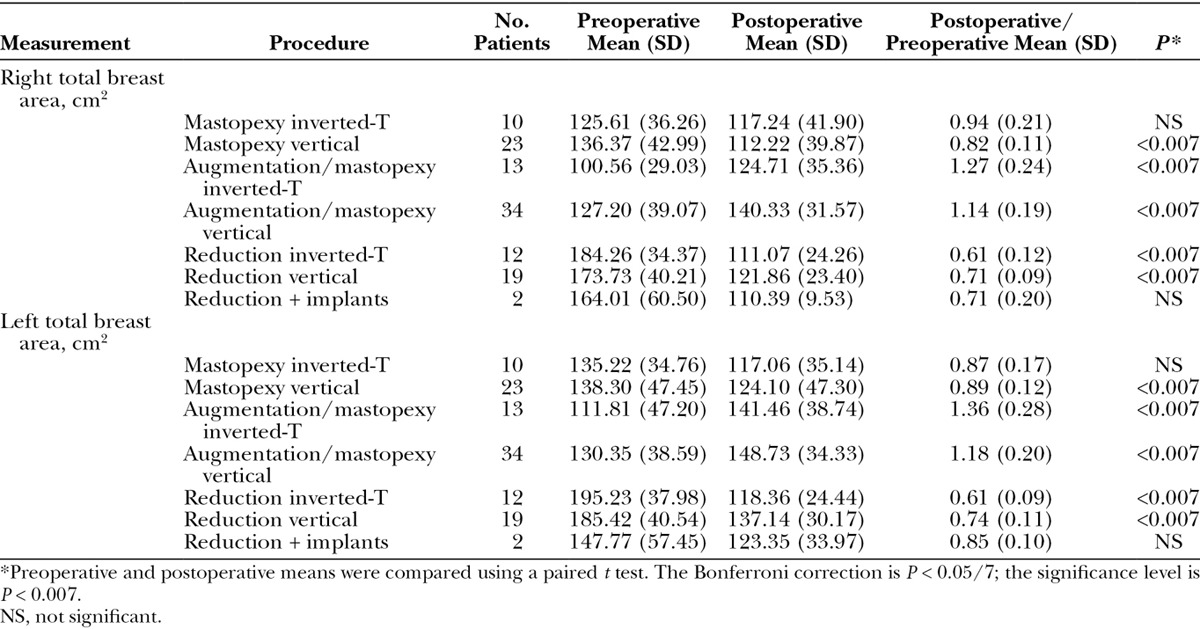

Breast mound elevation is defined as the vertical change in level of the plane of maximum breast projection.3 All patient groups demonstrated a significant elevation (P < 0.001) of the breast mound, averaging approximately 5 cm (Table 3), with no significant difference between techniques. Breast areas were reduced after mastopexies and reductions and increased after augmentation/mastopexies (Table 4).

Table 3.

Breast Mound Elevation

Table 4.

Preoperative and Postoperative Total Breast Area

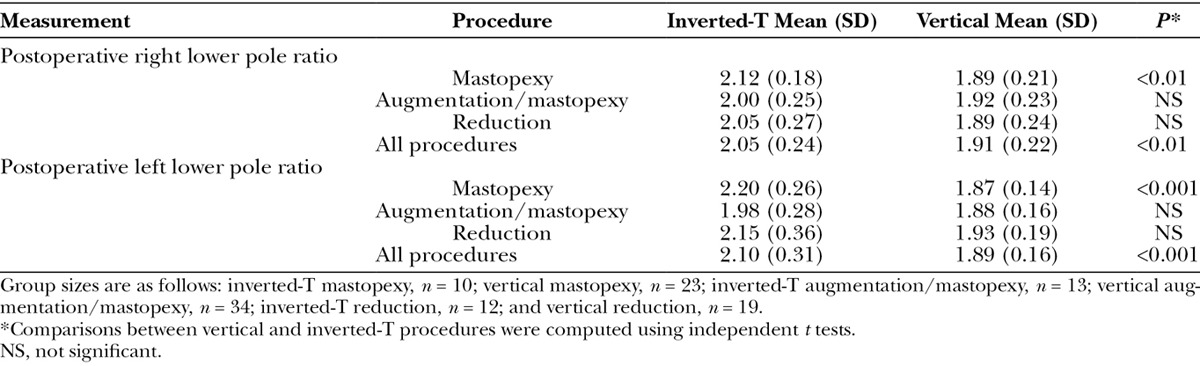

Lower pole ratios assess the boxiness of the lower pole by dividing the lower pole width by its vertical length.3 For vertical mastopexy and reduction procedures, the mean lower pole ratio measured 1.91 on the right and 1.89 on the left (Table 5). For inverted-T procedures, these ratios were significantly higher, measuring 2.05 on the right (P < 0.01) and 2.10 on the left (P < 0.001).

Table 5.

Postoperative Lower Pole Ratio (Lower Pole Width/Lower Pole Length)

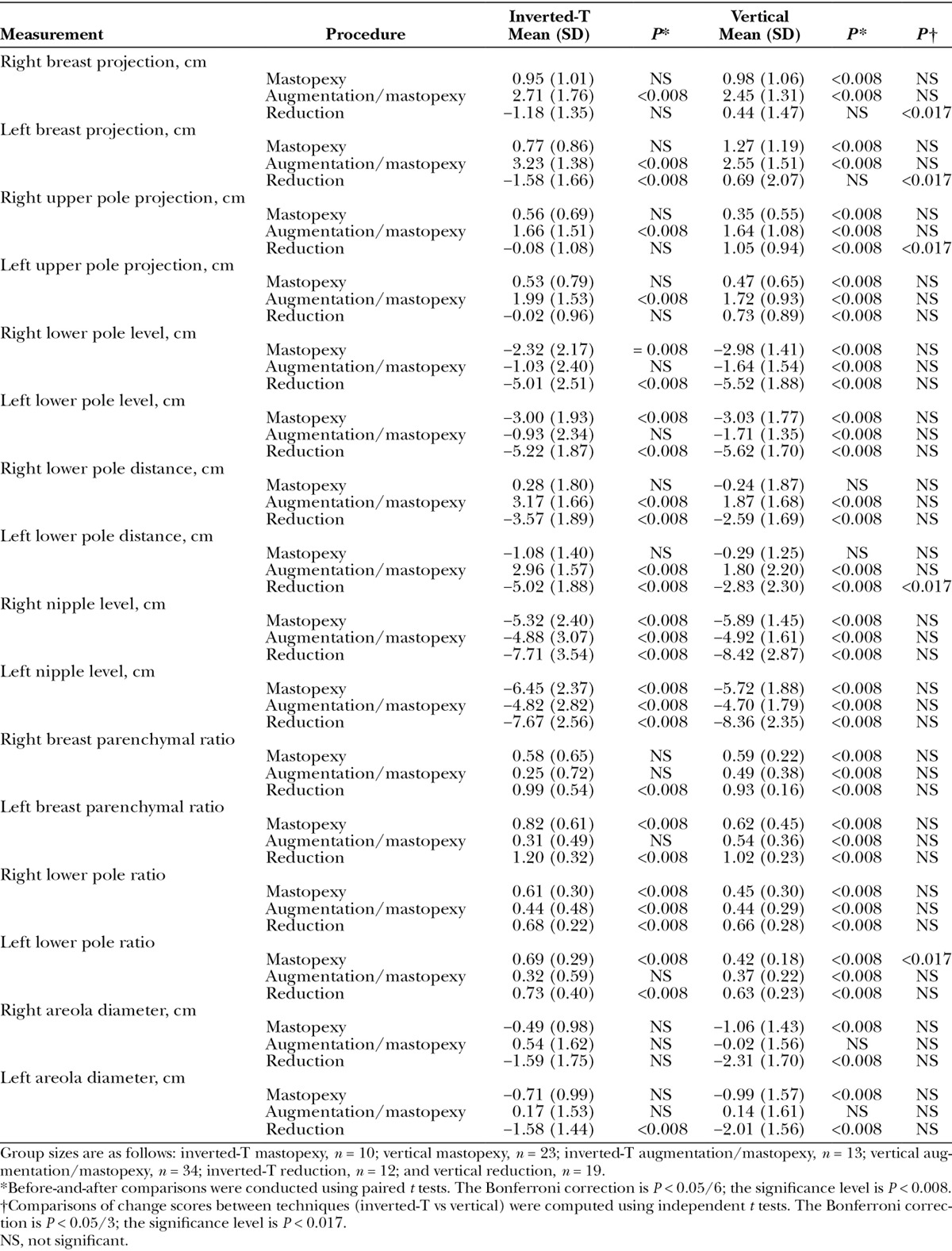

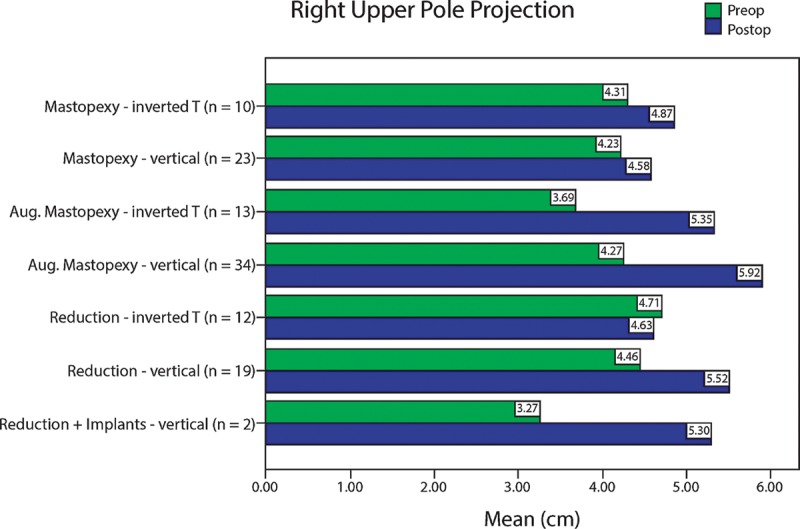

Breast implants boosted breast projection and upper pole projection regardless of technique (P < 0.008). Vertical mastopexy increased breast projection and upper pole projection (P < 0.008). Inverted-T mastopexy did not significantly increase breast projection or upper pole projection (Table 6).

Table 6.

Difference in Breast Measurements (Postoperative–Preoperative)

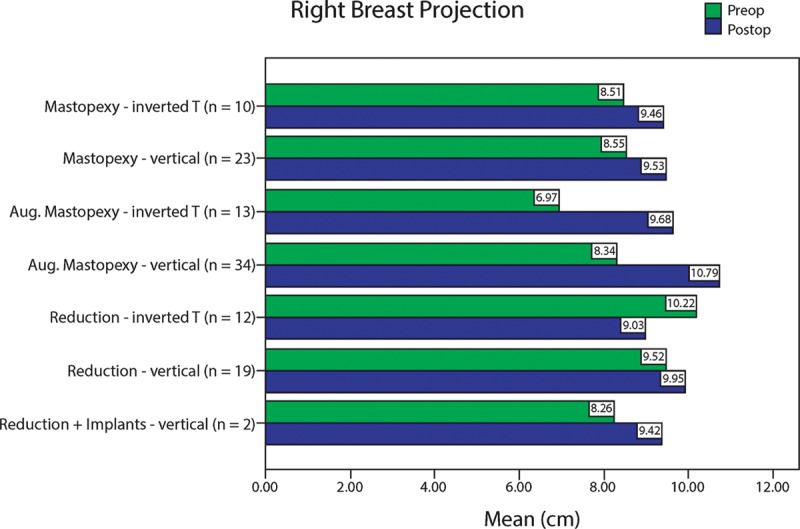

Neither vertical nor inverted-T breast reduction significantly increased breast projection (Table 6 and Fig. 5). For inverted-T reductions, there was an average loss of breast projection of 1.18 cm on the right (not significant) and 1.58 cm on the left (P < 0.008). Vertical breast reduction better preserved breast projection (P < 0.017) than the inverted-T technique. Vertical reduction significantly increased upper pole projection (P < 0.008), but inverted-T reduction did not (Table 6 and Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Right breast projection before (green) and after (blue) surgery.

Fig. 6.

Right upper pole projection before (green) and after (blue) surgery.

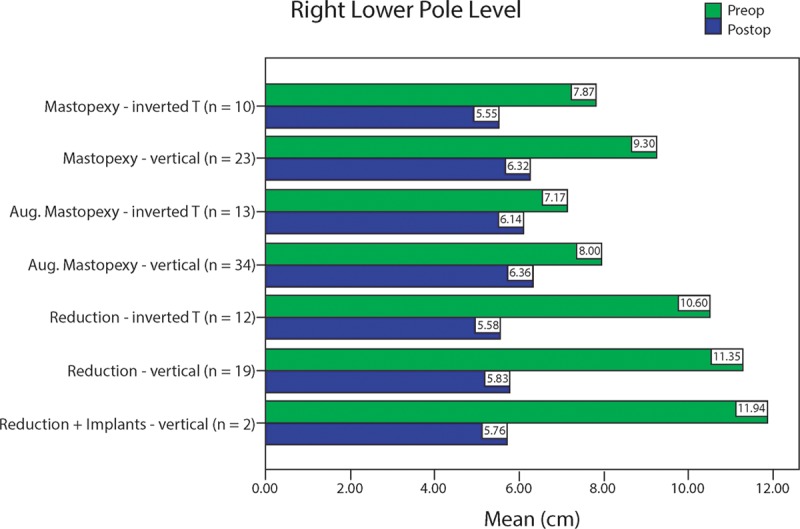

All vertical mammaplasties, including augmentation/mastopexies, reduced (elevated) the lower pole level on both sides (P < 0.008) (Table 6 and Fig. 7). The inverted-T procedure did not raise the lower pole significantly for augmentation/mastopexy but raised the lower pole level significantly for breast reduction and mastopexy (P ≤ 0.008).

Fig. 7.

Right lower pole level before (green) and after (blue) surgery. These measurements represent vertical distances from the most inferior point on the breast to the plane of maximum postoperative breast projection. Smaller values indicated higher levels.

The lower pole distance3 (the length along the lateral curve from the plane of maximum postoperative breast projection to the posterior breast margin), a measure of breast constriction, was reduced in both vertical and inverted-T breast reductions, but to a greater degree for inverted-T reductions (right, not significant; left, P < 0.017) (Table 6 and Fig. 4).

Vertical mastopexy, augmentation/mastopexy, and reduction significantly (P < 0.008) increased the breast parenchymal ratio (upper pole area/lower pole area). The inverted-T procedure increased the breast parenchymal ratio significantly on both sides for breast reduction (P < 0.008) and on the left side for mastopexy (P < 0.008), but on neither side for augmentation/mastopexy (Table 6).

DISCUSSION

The importance of evaluating the aesthetic result after reduction mammaplasty is well recognized.20 Remarkably, no existing publication compares the quality of the aesthetic result using defined, objective measurements in consecutive patients. This investigation was undertaken to remedy this deficiency.

Origins

The history of mastopexy and breast reduction is important because many old concepts continue to influence our thinking today. Aubert,21 in 1923, is credited as the first surgeon to transpose the nipple, bringing it out through a new buttonhole located higher on the breast. Nipple transposition has been a cornerstone of breast reduction and mastopexy surgery ever since. The inverted-T technique was introduced by Kraske22 and Lexer23 in the 1920s. This skin closure technique was also used by Biesenberger24 and was widely adopted.25–27 Aufricht26 removed breast tissue from the upper pole, transposed the nipple, and used an inverted-T skin closure, relying on the “skin brassiere” to provide form. Biesenberger24 and Maliniac25 believed that the parenchymal dissection was most important for shape, not the skin covering. Penn28 took Aufricht’s position that it was the skin envelope that mattered. The skin/parenchyma controversy continues to this day. Any surgeon performing a skin-only mastopexy relies on the skin envelope for shape. The inverted-T, inferior pedicle reduction, described by Ribeiro,29 Courtiss and Goldwyn,30 and Robbins14 in the 1970s, remains the most common breast reduction technique used in the United States, although the vertical technique is gaining popularity.31

Nipple/Areola Transposition

Nipple/areola transposition is based on an assumption that the nipple position falls on the breast and needs to be elevated with respect to the breast tissue. In an inverted-T mammaplasty, the nipple is separated from the rest of the breast tissue and moved superiorly while the surrounding breast tissue is paradoxically displaced inferiorly.13 This maneuver causes nipple overelevation.12,13

Even today, no procedure has been shown to truly accomplish upward movement of the breast on the chest wall. The illusion of a breast lift can only be reliably achieved by resecting lower pole excess tissue and filling the upper pole with an implant.32–35

Measurements reveal that in 60% of mammaplasty candidates, the nipple falls with the breast, not on it, and when it does slide on the breast, the distance is typically under 6.5 cm.13 Using the vertical technique, the nipple is raised with the breast mound and requires minimal relocation. Notably, Dartigues’36 original description of a vertical resection did not include nipple transposition, an approach that may still be suitable in secondary mammaplasties. In these patients, the nipple position is rarely too low.32

Anatomy

The inferior pedicle dissection removes breast tissue from the superior, medial, and lateral portions of the breast and preserves breast tissue centrally and inferiorly. Parenchymal removal from the upper pole rather than the lower pole puzzled Maliniac,25 in 1950. This skin resection pattern makes use of a horizontal ellipse that reduces breast projection and constricts the lower pole,12 a geometric effect that is confirmed by measurements of lower pole distance (Table 6 and Fig. 4). This parenchymal resection removes the medial and lateral breast tissue that might otherwise be used to elevate the nipple and increase projection, the length dividend that results from side-to-side closure of a vertical ellipse.13,32 In an inverted-T mammaplasty, the breast skin is pulled down rather than pushed up.12 Limiting the vertical limb to 5 cm does not prevent nipple overelevation (Figs. 2 and 4).12 Not surprisingly, in view of the upper pole parenchymal resection, the upper pole contour is consistently flat or concave (Figs. 2 and 4).

A midline resection cannot interfere with medially and laterally based blood supply and sensation. Ideally, the nipple/areola would remain attached both medially and laterally and even superiorly,37 but such a wide attachment allows minimal mobility and was the shortcoming of the Strombeck procedure.38 Fortunately, unilateral pedicles, based either laterally or medially, are sufficient.39,40 The medial circulation is dominant in about 70% of women and lateral circulation in 20% of women. Ten percent of women have equal contributions.41,42

Hall-Findlay2 found that a medially based pedicle provided better breast shape, by preserving tissue in the upper, medial quadrant, where it is desirable. Because of its geometry, a vertical ellipse improves projection and creates a tighter, more semicircular lower pole than the inverted-T, inferior pedicle technique [Tables 5 and 6, Figs. 1–4, and Supplemental Figs. 1–4 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/PRSGO/A21)]. These anatomic considerations support the use of a vertical mammaplasty and medially based pedicle.

Clinical Experience

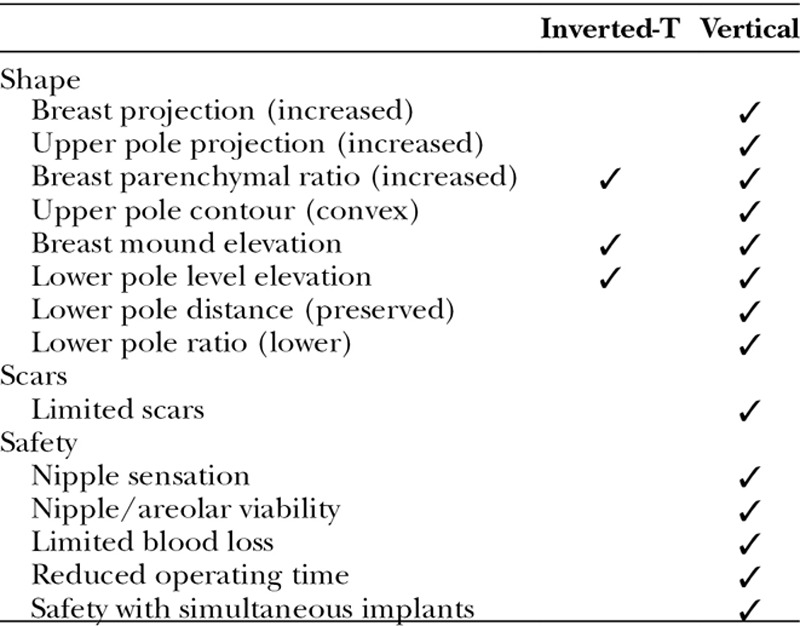

The techniques are compared in Table 7. As might be expected from anatomic considerations, the inverted-T, inferior pedicle mammaplasty can compromise nipple/areola perfusion. Lista and Ahmad7 report a series of 1501 vertical reductions without a single case of nipple loss. This experience is instructive to any surgeon wishing to avoid a complication that is devastating for patients and surgeons alike. Nipple/areola loss after the vertical technique may be related to compression and thinning of the pedicle when a superior pedicle is used2; a medial pedicle is safer.

Table 7.

Clinical Comparison of Inverted-T and Vertical Mammaplasties

Sensation

Courtiss and Goldwyn,43 in their well-known investigation of breast sensation, reported a 35% incidence of persistent nipple numbness 2 years after an inverted-T, inferior pedicle breast reduction. This rate may be compared with a 21.5% incidence of persistent numbness 2.5 years after a vertical reduction.44 Medial nipple innervation is important and should be preserved; superior pedicles, used in the Lejour technique, are more likely to compromise sensation by sacrificing the deep innervation and by partially excluding superficial medial innervation.45

Shape

It has been long recognized that the inverted-T technique produces flattening of the upper poles, boxiness of the lower poles, and a tendency to bottom-out.2,7,46 These clinical observations are confirmed by measurements in the present study.

Scars

The inverted-T, inferior pedicle technique produces a long inframammary scar, with levels of patient dissatisfaction in the range of 11–71%.47–51 Scar dissatisfaction after vertical mammaplasty is 4.7%.44 Patients consistently prefer the aesthetic result and scars of the vertical technique.50,52–54

Safety

Vertical mammaplasty requires a shorter operating time and less blood loss than the inverted-T, inferior pedicle technique.2,7 Blood transfusions are avoided.7 There is less surgeon fatigue and therefore more opportunity to safely perform other cosmetic surgeries at the same time.32

Limitations of the Study

The author first performed the vertical technique in 2002, so that patients in the prospective study group include his learning curve experience. Accordingly, the level of proficiency in the retrospective, inverted-T group is likely to be higher. Despite this advantage for the inverted-T group, the measurement data favor the vertical technique. The retrospective group included fewer patients because only 57.4% of the retrospective study patients met the 3-month follow-up criterion compared with 85.7% of the prospective study patients. Patients in the retrospective group were often discharged from follow-up after their 1 month postoperative photographs. Longer follow-up times are desirable, but come at the price of a reduced inclusion rate. Other studies have shown that postmammaplasty shape changes after 3 months are minimal,13,55 indicating that at 3 months swelling has resolved sufficiently for the purpose of measurements.

This study compares a prospective cohort with a historical control group. Two prospective contemporaneous cohorts are preferred. However, it would be unethical for the author to conduct such a study because of known advantages of the vertical technique. Long-term changes in breast shape are not assessed; such an analysis would be an appropriate subject for future study.

Strengths of the Study

This study benefits from consistencies that reduce confounding factors—the same surgeon, the same measurement system, and consecutive patients meeting the same inclusion criteria. Treating all patients in each group with the same technique (the author abandoned the inverted-T mammaplasty in 2002) removes selection bias that can weaken a comparison of cohorts if the surgeon prefers one technique more than the other for certain patients. For example, a common practice is to use the vertical technique for moderate degrees of hypertrophy and the inverted-T reduction for very large ones.56

CONCLUSIONS

Photographic measurements of relevant breast parameters favor the vertical technique over the inverted-T technique and are consistent with anatomical considerations and clinical experience.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author thanks Jane Zagorski, PhD, for statistical analyses; Lindsey Kroenke, BSN, for data collection; and Gwendolyn Godfrey for illustrations.

Supplemental Digital Content

Footnotes

Presented at Plastic Surgery 2008: 77th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, October 31 to November 5, 2008, Chicago, Ill.

Disclosure: The author has no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article. The Article Processing Charge was paid for by the author.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Clickable URL citations appear in the text.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rohrich RJ, Gosman AA, Brown SA, et al. Mastopexy preferences: a survey of board-certified plastic surgeons. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118:1631–1638. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000248397.83578.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall-Findlay EJ. A simplified vertical reduction mammaplasty: shortening the learning curve. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:748–759. discussion 760–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swanson E. A measurement system for evaluation of shape changes and proportions after cosmetic breast surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:982–992. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182442290. discussion 993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen CM, White C, Warren SM, et al. Simplifying the vertical reduction mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113:162–172. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000095943.74829.33. discussion 173–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serra MP, Longhi P, Sinha M. Breast reduction with a superomedial pedicle and a vertical scar (Hall-Findlay’s technique): experience with 210 consecutive patients. Ann Plast Surg. 2010;64:275–278. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181b0a611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neaman KC, Armstrong SD, Mendonca SJ, et al. Vertical reduction mammaplasty utilizing the superomedial pedicle: is it really for everyone? Aesthet Surg J. 2012;32:718–725. doi: 10.1177/1090820X12452733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lista F, Ahmad J. Vertical scar reduction mammaplasty: a 15-year experience including a review of 250 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:2152–2165. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000218173.16272.6c. discussion 2166–2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hofmann AK, Wuestner-Hofmann MC, Bassetto F, et al. Breast reduction: modified “Lejour technique” in 500 large breasts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120:1095–1104. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000279150.85155.1e. discussion 1105–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amini P, Stasch T, Theodorou P, et al. Vertical reduction mammaplasty combined with a superomedial pedicle in gigantomastia. Ann Plast Surg. 2010;64:279–285. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181b0a5d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rohrich RJ. Minimally invasive, limited incision breast surgery: passing fad or emerging trend? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:1315–1317. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200210000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nahabedian MY. Scar wars: optimizing outcomes with reduction mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:2026–2029. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000191197.21528.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swanson E. A retrospective photometric study of 82 published reports of mastopexy and breast reduction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:1282–1301. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318230c884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swanson E. Prospective photographic measurement study of 196 cases of breast augmentation, mastopexy, augmentation/mastopexy, and breast reduction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131:802e–819e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182865e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robbins TH. A reduction mammaplasty with the areola-nipple based on an inferior dermal pedicle. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1977;59:64–67. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197701000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DiBernardo BE, Adams RL, Krause J, et al. Photographic standards in plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:559–568. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199808000-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Westreich M. Anthropomorphic breast measurement: protocol and results in 50 women with aesthetically perfect breasts and clinical application. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100:468–479. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199708000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldwyn RM. Wanted: real clinical results. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:1000–1001. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. Analysis of variance. pp. 273–406. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, et al. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175–191. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hidalgo DA. Discussion. A detailed analysis of the reduction mammaplasty learning curve: a statistical process model for approaching surgical performance improvement. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:715–716. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181b17989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aubert V. Hypertrophie mammaire de la puberté. Résection partielle restauratrice. Arch Franco-Belges de Chir. 1923;3:284–289. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kraske H. Die operation der atrophischen und hypertrophie schen hängebrust. Münch Med Wschr. 1923;60:672. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lexer E. Zur operation der mammahypertrophie und der hängebrust. Dtch Med Wschr. 1925;51:26. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biesenberger H. Deformitaten und Kosmetische Operationen der Weiblichen Brust. Wien: Wilhelm Maudrich; 1931. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maliniac JW. Breast Deformities and Their Repair. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1950. pp. 20–103. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aufricht G. Mammaplasty for pendulous breasts; empiric and geometric planning. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1949;4:13–29. doi: 10.1097/00006534-194901000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bames HO. Breast malformations and a new approach to the problem of the small breast. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1950;5:499–506. doi: 10.1097/00006534-195006000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Penn J. Breast reduction. Br J Plast Surg. 1955;7:357–371. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1226(54)80046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ribeiro L. A new technique for reduction mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1975;55:330–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Courtiss EH, Goldwyn RM. Reduction mammaplasty by the inferior pedicle technique. An alternative to free nipple and areola grafting for severe macromastia or extreme ptosis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1977;59:500–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okoro SA, Barone C, Bohnenblust M, et al. Breast reduction trend among plastic surgeons: a national survey. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:1312–1320. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181881dd7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swanson E. Prospective comparative clinical evaluation of 784 consecutive cases of breast augmentation and vertical mammaplasty, performed individually and in combination. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:30e–45e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182910b2e. discussion 46e–47e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hall-Findlay EJ. Pedicles in vertical breast reduction and mastopexy. Clin Plast Surg. 2002;29:379–391. doi: 10.1016/s0094-1298(02)00008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baroudi R, Lewis JR. The augmentation-reduction mammaplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1976;3:301–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Regnault P, Daniel RK, Tirkanits B. The minus-plus mastopexy. Clin Plast Surg. 1988;15:595–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dartigues L. Esthetique mammaire. Traitement chirurgical du prolapsus mammaire. Arch Franco-Belges Chir. 1925;28:313–328. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pitanguy I. Surgical treatment of breast hypertrophy. Br J Plast Surg. 1967;20:78–85. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1226(67)80009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strombeck JO. Mammaplasty: report of a new technique based on the two-pedicle procedure. Br J Plast Surg. 1960;13:79–90. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1226(60)80014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skoog T. A technique of breast reduction; transposition of the nipple on a cutaneous vascular pedicle. Acta Chir Scand. 1963;126:453–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strombeck JO, Rosato FE. Surgery of the Breast. Diagnosis and Treatment of Breast Diseases. Vol. 303. Stuttgart: Thieme; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maliniac JW. Arterial blood supply of the breast: revised anatomic data relating to reconstructive surgery. Arch Surg. 1943;47:329–343. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palmer JH, Taylor GI. The vascular territories of the anterior chest wall. Br J Plast Surg. 1986;39:287–299. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(86)90037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Courtiss EH, Goldwyn RM. Breast sensation before and after plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;58:1–13. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197607000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Swanson E. Prospective outcome study of 106 cases of vertical mastopexy, augmentation/mastopexy, and breast reduction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013;66:937–949. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2013.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schlenz I, Rigel S, Schemper M, et al. Alteration of nipple and areola sensitivity by reduction mammaplasty: a prospective comparison of five techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:743–751. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000152435.03538.43. discussion 752–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reus WF, Mathes SJ. Preservation of projection after reduction mammaplasty: long-term follow-up of the inferior pedicle technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;82:644–652. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198810000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davis GM, Ringler SL, Short K, et al. Reduction mammaplasty: long-term efficacy, morbidity, and patient satisfaction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:1106–1110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Glatt BS, Sarwer DB, O’Hara DE, et al. A retrospective study of changes in physical symptoms and body image after reduction mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:76–82. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199901000-00013. discussion 83–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramon Y, Sharony Z, Moscona RA, et al. Evaluation and comparison of aesthetic results and patient satisfaction with bilateral breast reduction using the inferior pedicle and McKissock’s vertical bipedicle dermal flap techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106:289–295. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200008000-00006. discussion 295–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferreira MC. Evaluation of results in aesthetic plastic surgery: preliminary observations on mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106:1630–1635. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200012000-00032. discussion 1636–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sprole AM, Adepoju I, Ascherman J, et al. Horizontal or vertical? An evaluation of patient preferences for reduction mammaplasty scars. Aesthet Surg J. 2007;27:257–262. doi: 10.1016/j.asj.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cruz-Korchin N, Korchin L. Vertical versus Wise pattern breast reduction: patient satisfaction, revision rates, and complications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112:1573–1578. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000086736.61832.33. discussion 1579–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Godwin Y, Wood SH, O’Neill TJ. A comparison of the patient and surgeon opinion on the long-term aesthetic outcome of reduction mammaplasty. Br J Plast Surg. 1998;51:444–449. doi: 10.1054/bjps.1997.0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Celebiler O, Sönmez A, Erdim M, et al. Patients’ and surgeons’ perspectives on the scar components after inferior pedicle breast reduction surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:459–464. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000173060.02593.3a. discussion 465–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eder M, Klöppel M, Müller D, et al. 3-D analysis of breast morphology changes after inverted T-scar and vertical-scar reduction mammaplasty over 12 months. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013;66:776–786. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rohrich RJ, Thornton JF, Jakubietz RG, et al. The limited scar mastopexy: current concepts and approaches to correct breast ptosis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:1622–1630. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000139062.20141.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.