Abstract

Summary:

Skin cancer formation is on the rise. Only a few case reports, which focus on skin cancer being caused by tattoos, have been published so far. Our aim is to determine whether skin cancer occurrence can be triggered by tattoos. In our presented case, a squamous-cell carcinoma developed inside of the red areas of a multicolored tattoo within months. Furthermore, surgical removal of the cancerously mutated skin area without mutilating the design of the tattoo was challenging. Due to widespread skin alterations in other red areas of the tattoo, those affected skin regions were surgically removed and split-skin grafting was performed. After 1-year follow-up period, the patient has been tumor free. Squamous-cell carcinoma is an unusual reaction that can occur in tattoos. Nevertheless, this skin cancer should be included in the list of cutaneous complications related to tattooing.

Tattoos have become fairly popular within Western society.1 The prevalence of tattooed individuals in the United States is estimated to be around 25% among the population aged 18–50 years,2 whereas in Europe, this proportion is closer to 10%.3 Tattooing is defined by the implementation of exogenous pigment and dye into the dermis to obtain a long-lasting individual design. The implemented exogenous pigment at times can cause inflammatory processes inside of the skin. Therefore, it is not surprising that the incidence of tattoo-associated skin dermatoses and neoplasia—like in our presented case with a squamous-cell carcinoma (SCC)—have been on the rise during the past few years.4 Clinical diagnosis can be challenging as differential diagnoses include skin alterations based on allergic reactions, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, and keratoacanthomas.4

CASE REPORT

A 48-year-old white male patient with no medical history was referred to our clinic suffering from a histopathologically verified SCC on his lower left leg. Three weeks earlier, the patient consulted his physician because he had observed skin alterations within red parts of his multicolored tattoo, which he had received 4 months before the occurrence. The body art was done by a licensed tattooist with nontoxic, organic inks by Eternal Ink—for the red sections, “Dark Red” ink was used. The patient did not have a history of trauma or severe sunburn within the altered skin area. In the following, a SCC (pT1, G1) with invasive growth features into the dermis was diagnosed (Fig. 1). For further medical treatment, the patient was transferred to our clinic and a R0 tumor resection was carried out. During follow-up consultations, the patient developed a wound dehiscence. Additionally, in other red areas of the tattoo, further suspected skin alterations were observed. As a consequence, a second surgery was performed 6 weeks after the first surgical intervention. At that time, all remaining skin alterations were surgically removed—the pathological review confirmed nonmalignant skin dermatoses without new carcinoma formation in this area. Finally, the still remaining skin defect was covered with split-skin graft from the left upper limb. After a 1-year follow-up period, the patient has been tumor free (Fig. 2).

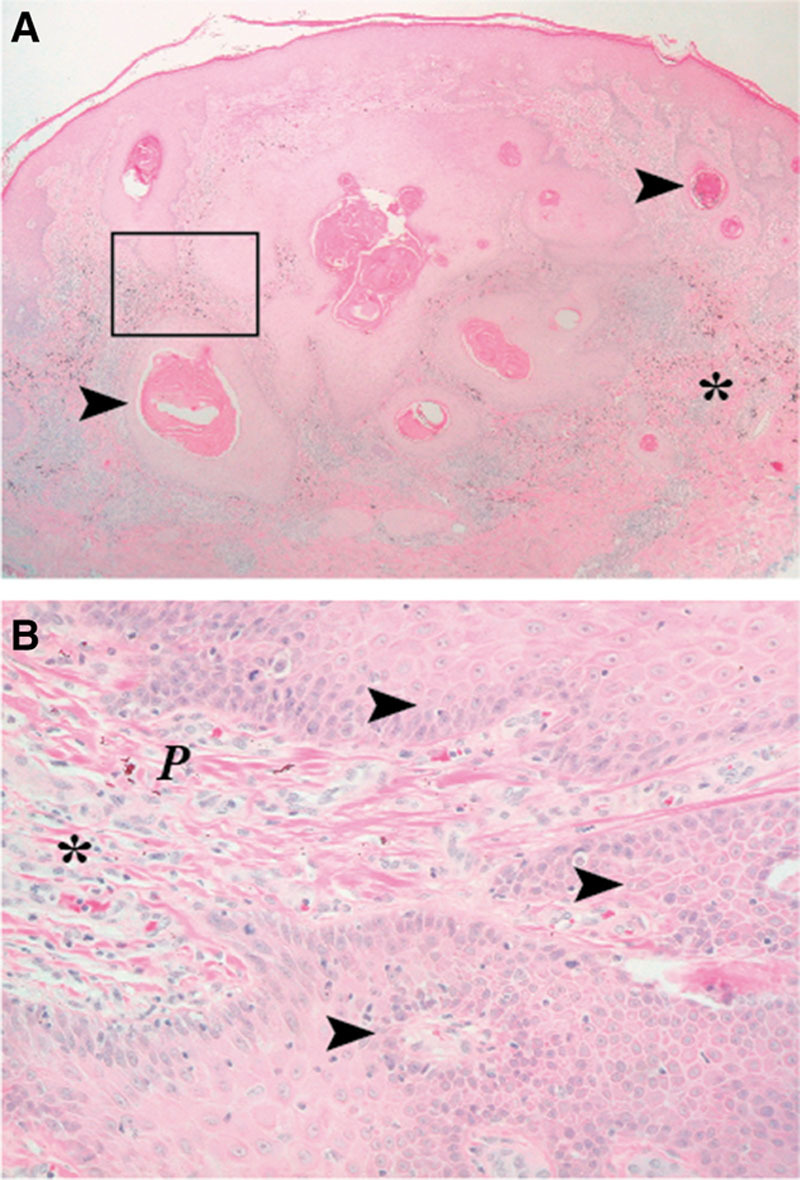

Fig. 1.

Histopathological verification of a SCC. A, As a relative well-circumscribed neoplasm in the dermis, the tumor is composed of strands and nodules of atypical squamous cells with some mitoses and furthermore shows endophytic prolongation into the dermis. Also variable central keratinization and horn pearls formation can be found. Magnified rectangular cutout shown in (B) with typical nests of squamous cells alongside with atypia and mitotic activity in the dermis, near to the tumor formation red pigment, can be seen. Arrow, SCC complex; P, red exogenous pigment; *, infiltrate of histiocytes and lymphocytes; (A), 25-fold microscopic magnification, and (B), 200-fold microscopic magnification.

Fig. 2.

Surgical tumor resection. A, After the first surgical procedure, the histopathologically diagnosed SCC was completely resected (arrow, scar). B, Later on, within 1 part of the surgical area, a wound dehiscence developed and further skin alterations inside of remaining red parts of the multicolored tattoo came up (arrow, wound dehiscence + skin changes). Those lesions were once more surgically removed and the wound was covered with split-skin graft. C, Final medical result 1 y after the last surgical treatment (asterisk, completed wound repair).

DISCUSSION

Tattooing has gained tremendous popularity during the last 2 decades among young people in developed countries.1 The growing popularity of tattoos may be the result of broader social acceptance, cosmetic appearance, or the option of a more efficient tattoo-laser-removal. Inks in all kinds of colors have been developed by the industry, resulting in even more complex artistic tattoos. It has to be mentioned that the precise composition of tattoo ink is neither nationally nor internationally standardized. It is still the case that in some countries, multiple carcinogenic substances are used for certain tattoo dyes.4 Nevertheless, mercury sulfide, which can be responsible for red tattoo reactions, has since been eliminated by major fabricants, from tattoo ink—as to mention 1 positive impact. Although this substance has been replaced by other inorganic/organic compounds, in particular, red ink still causes more reactions than other colors.5 Red tattoo reactions are indeed the most common, even though reactions to almost all colors have been reported.5

The skin represents the largest organ of the human body, serving as a barrier to the environment and having the ability to metabolize absorbed chemicals.4 The incidence of tattoo-associated skin dermatoses and neoplasia have been increasing over the past years.4 Tattooing involves the application of pigment such as metallic salts and organic dyes, which remain inside of the skin’s dermis for decades.4 Directly after initial injection, the dye is scattered between the epidermis and the upper dermis. The injected pigment is detected by the immune system as intrusive material and consequently is absorbed by phagocytes. Later on, the damaged epidermis falls apart and the surface pigment is vanished. In the dermis, granulation takes place and connective tissue is formed. Therefore, the implemented dye is trapped within fibroblasts, resulting in an increased concentration inside of the layer just below the epidermis-dermis boundary. Despite the fact that exogenous pigment in this area is quite stable, within decades it still tends to shift deeper into the dermis.

SCC is the second-most prevalent cancer of the skin—it is more common than basal cell carcinoma and less common than melanoma.6 Unlike basal cell carcinoma, SCC is associated with a low substantial risk of metastasis.6 The histopathological presentation of SCC varies from scaly erythematous plaques or cutaneous horns to crusted ulcerated lesions.7 It arises from uncontrolled multiplication of cells of the epithelium or cells showing particular cytological or tissue architectural characteristics of squamous-cell differentiation.7 The characteristic features are full-thickness epidermal atypia with disordered architecture, abnormal mitoses, and dyskeratosis.7 Early excision of small lesions generally is associated with an excellent prognosis.8

So far mainly keratoacanthoma, as a SCC subgroup, and only a few other forms of SCC have been described in scientific literature to be triggered by tattoos.1,4,9–12 Therefore 2 different ways of SCC tumor formation should be mentioned: new, trauma-induced keratoacanthomas that occur rapidly—until up to 1 year after the initial tattooing procedure—or classic SCCs that usually develop over multiple years after the initial tattooing procedure.4 Our presented case seems to be a mixture—a rapid SCC tumor formation within less than 6 months. This kind of tumor behavior has not been described in scientific literature so far—also considering the patient’s blank medical record, his fairly young age, and no history of binge tanning. Compared with older case reports, it seems that patients who develop skin cancers within tattoos nowadays are younger and have a shorter delay since tattoo application.13 Despite that fact, red and black colors have always been the most commonly used colors for tattoos.3 However, red is known to be the main color responsible for hypersensitivity tattoo reactions and seems to be the most common color for triggering SCCs, keratoacanthomas, and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia.4 Therefore, the authors of this presented case think that SCC occurrence is strongly connected with the red ink’s usage for tattooing.

CONCLUSION

SCC is an unusual reaction that can occur in tattoos; however, the association may be coincidental.4 The authors of this case report believe that SCC should be added to the list of histological patterns of tattoo-related inflammatory reactions, especially in cases of rapidly growing lesions. Surgical removal and thorough histological analysis of the entire skin alteration are fundamental. The prognosis is favorable after an in-total excision of the skin cancer. Nevertheless, routine surveillance and careful follow-up examinations are recommended, as reoccurrence is possible.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Mr. Jon Kaczmarczyk and Mr. Peter Khoury for the English text editing.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article. The Article Processing Charge was paid for by the Agaplesion Diakonieklinikum Rotenburg.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sarma DP, Dentlinger RB, Forystek AM, et al. Poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma arising in tattooed skin. Case Rep Med. 2010;2010:431813. doi: 10.1155/2010/431813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laumann AE, Derick AJ. Tattoos and body piercings in the United States: a national data set. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:413–421. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klügl I, Hiller KA, Landthaler M, et al. Incidence of health problems associated with tattooed skin: a nation-wide survey in German-speaking countries. Dermatology. 2010;221:43–50. doi: 10.1159/000292627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kluger N, Koljonen V. Tattoos, inks, and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:e161–e168. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70340-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mortimer NJ, Chave TA, Johnston GA. Red tattoo reactions. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:508–510. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samarasinghe V, Madan V, Lear JT. Management of high-risk squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2011;11:763–769. doi: 10.1586/era.11.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arlette JP, Trotter MJ. Squamous cell carcinoma in situ of the skin: history, presentation, biology and treatment. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45:1–9; quiz 10. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2004.00025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia-Zuazaga J, Olbricht SM. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Adv Dermatol. 2008;24:33–57. doi: 10.1016/j.yadr.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McQuarrie DG. Squamous-cell carcinoma arising in a tattoo. Minn Med. 1966;49:799–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kluger N, Minier-Thoumin C, Plantier F. Keratoacanthoma occurring within the red dye of a tattoo. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:504–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldenberg G, Patel S, Patel MJ, et al. Eruptive squamous cell carcinomas, keratoacanthoma type, arising in a multicolor tattoo. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:62–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vitiello M, Echeverria B, Romanelli P, et al. Multiple eruptive keratoacanthomas arising in a tattoo. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:54–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kluger N, Phan A, Debarbieux S, et al. Skin cancers arising in tattoos: coincidental or not? Dermatology. 2008;217:219–221. doi: 10.1159/000143794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]