Abstract

Background

The state of Maryland implemented innovative budgeting of outpatient and inpatient services in eight rural hospitals under the Total Patient Revenue (TPR) system in July, 2010.

Methods

This paper uses data on Maryland discharges from the 2009-2011 Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) State Inpatient Databases (SID). Individual inpatient discharges from eight treatment hospitals and three rural control hospitals (n=374,353) are analyzed. To get robust estimates and control for trends in the state, we also compare treatment hospitals to all hospitals in Maryland that report readmissions (n=1,997,164). Linear probability models using the difference-in-differences approach with hospital fixed effects are estimated to determine the effect of the innovative payment mechanisms on hospital readmissions, controlling for patient demographics and characteristics.

Results

Difference-in-differences estimates show that after implementation of TPR in the treatment hospitals, there were no statistically significant changes in the predicted probability of readmissions.

Conclusions

Early evidence from the TPR program shows that readmissions were not affected in the 18 months after implementation.

Implications

: As the health care system innovates, it is important to evaluate the success of these innovations. One of the goals of TPR was to lower readmission rates, however these rates did not show consistent downward trends after implementation. Our results suggest that payment innovations that provide financial incentives to ensure patients receive care in the most appropriate setting while maintaining quality of care may not have immediate effects on commonly used measures of hospital quality, particularly for rural hospitals that may lack coordinated care delivery infrastructure.

Keywords: Maryland, health care reform, hospital readmissions, innovative payment

Introduction

The US health care system is undergoing rapid transformation in an effort to address high levels of health care expenditures, to control growth in spending, and to reduce widespread inefficiency. Although hospitals account for over one-third of total health care spending,1 there are few incentives in our primarily fee-for-service payment system to encourage hospitals, physicians and other health care providers to coordinate care.2 This results in duplication of efforts, overuse of services, and extensive waste.2,3 There is a consensus that there is a need to move beyond traditional fee-for-service reimbursement strategies, and encourage study of emerging models of provider-payment reform.2,4–9 Innovative payment mechanisms that discourage volume of care and reward collaborative, efficient care show promise in slowing expenditure growth, especially in the high-cost hospital setting.10

All-Payer System in Maryland

The state of Maryland is well-suited to transform its health care delivery system because it is the only state that sets hospital rates for all payers.3–6 Maryland implemented its' system of full rate-setting authority for all payers and all general acute hospitals in 1976.7 Rates are prospectively set, largely in line with Medicare's hospital prospective payment system (PPS), with no discounts or preference to specific payers.7 The all-payer system includes pay-for-performance incentives. A value-based purchasing initiative results in redistribution of system revenue from lower-to-higher performing hospitals, and an initiative to reduce hospital acquired infections provides hospitals incentives to reduce preventable conditions.

Total Patient Revenue

Maryland is on the forefront of health care reform, with a new system in place to realign providers' incentives through sweeping payment reform. Maryland implemented the Total Patient Revenue (TPR) program in eight rural hospitals on July 1, 2010.11 TPR is a voluntary alternative hospital financing strategy developed by the Health Services Cost Review Commission (HSCRC) covering all inpatient and outpatient services for rural hospitals.12–14 TPR revenue constraint systems were made available to hospitals operating in regions of the state characterized by an absence of densely overlapping service areas.14 The program changed incentives for hospitals by providing a global budget that guarantees a specified annual revenue for each hospital regardless of the number of patients treated and the amount of services provided.14 This is a significant deviation from the system that financially rewarded admissions and readmissions rather than including strong financial settings to reduce them.

The primary goal of the TPR program is to provide the hospitals with strong incentives to treat its community of patients in the most efficient and clinically effective way, improving the value of the care provided via lower cost and better clinical effectiveness/quality.14 TPR aligns with several “best practices” of alternative payment systems that influence changes in utilization and quality.15 Such best practices include quantifying measures that have room for improvement, coordinated program design, and incentives for quality attainment and improvement that are large enough to motivate a behavioral response. Participating hospitals now have incentives to increase efficiency of health care delivery, contain costs, and to reduce avoidable admissions and readmissions.16 HSCRC staff monitor hospital performance on quality of care metrics, with the expectation that each hospital will at a minimum maintain its relative performance ranking on the HSCRC Quality-Based Reimbursement (QBR) and Maryland Hospital Acquired Conditions rankings.14 There is concern that the initiative may lead to hospitals directing patients to rival facilities, providing insufficient care or selecting healthier patients; HSCRC announced it would closely monitor hospitals' practices.16

The budget for each hospital is based on the hospital's revenue from the prior fiscal year.13 Base year patient revenues are adjusted for price variance from approved rates, for volume variances, and change in differential due to changes in payer mix.14 The approved revenue is adjusted based on each hospital's relative performance on specific quality measures.12 Annual adjustments to the budget also include adjustment for population changes and growth, reversal of any previous retroactive adjustments, and differential readjustments due to payer mix changes and bad debt.14 If participating hospitals lower spending by reducing admissions, readmissions or by other strategies, they keep the resulting savings.12 However, if costs increase beyond the budget allotment, the hospital bears financial risk, and can adjust their prices within a 5% corridor in the next year.13,14,17 Focusing efforts on reducing readmission rates to improve quality of care and reduce costs is a strategy that has proven to be effective.18,19

Readmission rates are increasingly used in assessment of health care system performance;20 they have advantages and limitations as measures of quality of health care.21,22 Readmissions may be appropriate under certain circumstances, but they occur often at significant additional financial and health expense.18,23 There has been very little improvement in national average 30-day readmission rates in recent years.23 The Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 authorizes penalties for hospitals with Medicare admissions that exceed a hospital's average, risk-adjusted 30 day readmission rate for specific diagnoses.20,21,24 Hospitals have naturally shifted focus to reducing readmission rates in effort to improve quality of care and reduce costs.18,19 Readmissions are an important metric of quality of care, and hospitals did not have adequate financial incentives to reduce readmissions before the state of Maryland altered their incentive structure in 2010 to “aggressively reduce readmissions”- the focus of this analysis.14,25 To our knowledge, Maryland is the first state to implement global budgeting of hospital and outpatient services (Rochester, New York globally budgeted only inpatient services in the 1980s26). The goal of this paper is to analyze the early effects of implementation of the TPR program on hospital readmissions.

Material and Methods

Data

This analysis uses patient-level discharge data for Maryland from the State Inpatient Database (SID) core data file for 2009, 2010, and 2011 (the most recent year available).27 The SID data are from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) dataset sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Department of Health and Human Services. The HSCRC supplies these state-level data on the universe of discharges in Maryland for HCUP. Authorized use of the SID data comes with limitations. Researchers agree to report only aggregate level statistics, so this analysis does not tabulate any data at the individual hospital level beyond data already publicly available. Researchers agree to not contact establishments included in the data.6

We identify the eight rural treatment hospitals that began participating in the TPR program in July, 2010. Two of the participating hospitals report their data together (Dorchester General and The Memorial Hospital at Easton), so the treatment hospitals include data reported from seven sources. TPR was already implemented in two rural hospitals, Edward. W. McCready Memorial Hospital and Garrett County Memorial Hospital, so these two hospitals are excluded from the analysis.

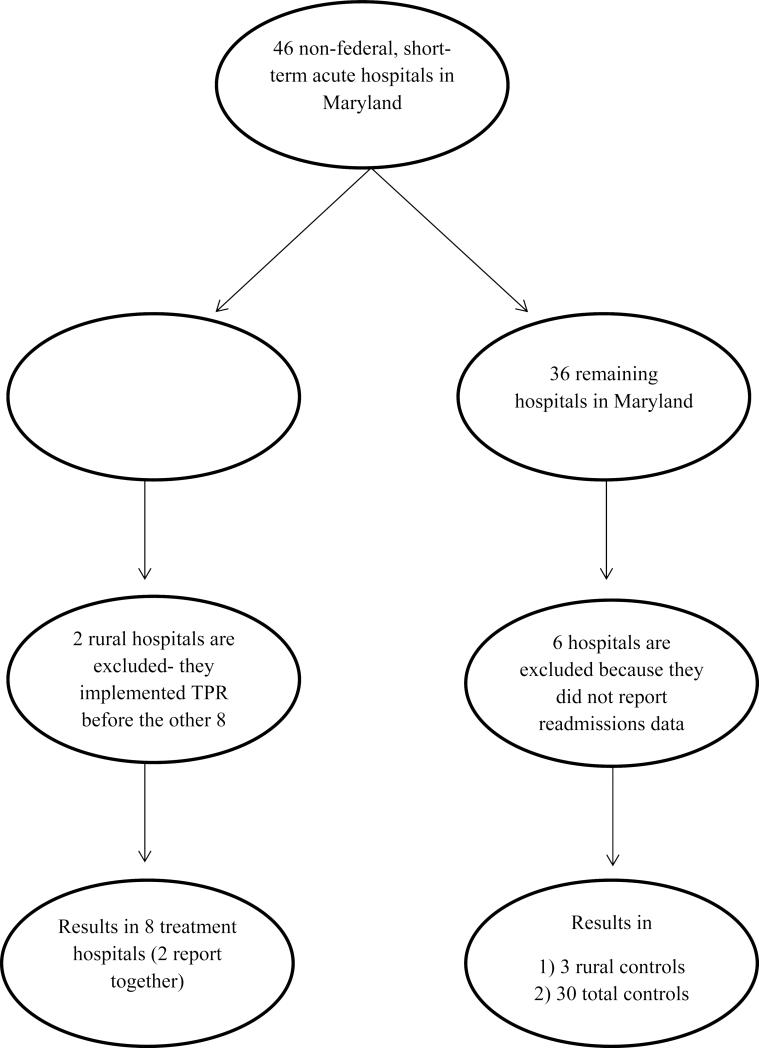

There are a total of 46 non-federal, short-term acute care hospitals in Maryland (http://www.ahd.com/states/hospital_MD.html). We use the remaining 36 that are not participating in TPR as the universe for our two control groups (Figure 1). For the first control group, we identify the remaining seven hospitals that are classified as rural hospitals.28 Two of these hospitals (Peninsula Regional Medical Center and Atlantic General Hospital) did not report readmissions data in the SID, so they are excluded from the analysis. Of the remaining five rural hospitals, we select three hospitals that did not participate but were identified by HSCRC as potential participants in TPR in the future to serve as controls.29 These three rural hospitals include Civista Medical Center, Frederick Memorial Hospital, and Upper Chesapeake Medical Center.

Figure 1.

Maryland Hospitals Included as Treatment and Controls

The second control group that includes the three rural controls, two additional rural hospitals, and the remaining 25 Maryland hospitals that report readmissions data (four additional hospitals in the state did not have readmission data in the SID). The data set has 1,997,164 observations representing patient admissions for the 37 reporting hospital units included in this analysis.

Variables

The analysis controls for characteristics that proxy for risk adjustment. The demographic variables include patient's age, sex, race (white, black, other race), and ethnicity (Hispanic). The primary payer for the discharge is categorized as private insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, self-pay, and no payment. We include the count of unique chronic diagnoses reported on the discharge as a measure for risk-adjustment. Estimated median household income measured at the patient's zip code of residence is included in quartiles, with classification cut-off values varying by year.30 Patients discharged from small hospitals have been found to have higher readmission rates than those discharged from large hospitals.19 With the exception of one medium-sized hospital, all of the hospitals in the treatment and rural controls fall under the category of rural large hospitals in the Northeastern region of the US.31 All of the treatment and rural control hospitals in this analysis are short-term acute care, voluntary, nonprofit hospitals.

Three key explanatory variables are generated for the analysis. The first is a temporal measure that captures the pre- and post- periods. The indicator for post equals one for all months beginning with the July 1, 2010 implementation date. The second binary variable is an indicator for treatment status, equaling one for all of the seven hospitals participating in the TPR program. The third indicator variable is the interaction term between post and treatment status. This interaction variable is the key coefficient for interpreting the effect of the TPR program on readmissions in participating hospitals.

The outcome variable is the binary readmission variable. The Maryland SID includes a binary variable indicating readmission. The READMIT variable indicates that the patient was admitted within 31 days of this admission.30 The state of Maryland did not have an accurate algorithm to consistently match patients across hospitals during the study period,32 so this readmission measure is strictly an intra-hospital readmission. The Maryland data do not have unique patient identifiers, so visit linking and timing variables for alternative readmission indicators are not available. Although not a perfect comparison, data on preventable readmissions for Medicare beneficiaries in the state of Maryland in 2008 MedPAR data suggest that inter-hospital and out-of-state readmissions are not a major concern for these rural hospitals.33 The differences in 30 day readmission rates for intra-hospital only compared to rates for intra- and inter-hospital readmissions range from a low of an increase of .06 percentage points (Chester River Hospital Center) to a high of a 2.42 percentage point increase (9.72% to 12.14% at Calvert Memorial Hospital).33

Methods

This analysis employs a difference-in-difference specification, used widely in the health services literature.10,34,35 The first difference is a pre-post comparison of hospitals that implement TPR during the study period. The second difference is the experience of rural hospitals that did not participate in the program over the same time period. These non-participating hospitals are similar in that they are also rural with distinct service areas, and serve as a control group to difference out factors unrelated to TPR that may have influenced readmission trends over the study period. As a sensitivity check, we re-estimate the analysis using the control group of rural and urban hospitals in Maryland to control for general trends in readmissions throughout the state.

We employ a fixed effects framework accounting for unobserved, time-invariant hospital characteristics, since hospitals' environments such as the policy environment, local health care markets and membership in integrated systems contribute to their capacity to reduce readmissions.36 The fixed effects regressions are estimated in Stata 11.2 using the xtreg command, which estimates linear panel data models. Linear models may be preferred when estimating fixed effects models,37 and have been used in the readmissions literature.38 They provide a clear interpretation of both the magnitude and sign of the interaction coefficient. However, to address concerns about the limitations of the ordinary least squares framework, we also estimated probit regressions that include hospital dummy variables as a sensitivity check (results available from authors upon request). We cluster the analysis at the hospital level and use the robust command in Stata to calculate appropriate standard errors.

Results

Table 1 presents publicly available data on the eight hospitals that participated in the TPR program, as well as the three rural controls and the larger set of control hospitals in the state. Treatment hospitals had statistically significantly fewer staffed beds than the controls. The average number of staffed beds for the treatment hospitals is 181, compared to 199 for the rural control hospitals and 320 for all the control hospitals. The average of total discharges for treatment (11,921) is lower than the average for rural control hospitals (14,201) and all controls (19,777). Gross patient revenue figures reported for fiscal year ending 2011 are from Medicare Cost report data available online from www.ahd.com. Average gross patient revenue for the treatment hospitals ($191,753) is similar to that of the rural control hospitals ($247,577) and all controls ($464,566).

Table 1.

Structural Characteristics of Treatment, Rural Control and All Control Hospitals - Total Patient Revenue

| Hospital Name | Staffed Beds | Total Discharges | Gross Patient Revenue ($000) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | |||

| Calvert Memorial Hospital | 116 | 9,221 | $124,295 |

| Carroll Hospital Center | 197 | 17,311 | $216,533 |

| Chester River Hospital Center | 53 | 3,522 | $62,804 |

| Dorchester General Hospital in Cambridge+ | − | − | − |

| The Memorial Hospital at Easton | 179 | 13,297 | $251,802 |

| Meritus Medical Center | 288 | 18,107 | $297,359 |

| Union Hospital | 140 | 8,002 | $126,899 |

| Western Maryland Regional Medical Center | 295 | 13,985 | $265,796 |

| Average | 181 | 11,921 | $191,753 |

| Rural Controls | |||

| Civista Medical Center | 120 | 9,151 | $113,146 |

| Frederick Memorial Hospital | 294 | 18,318 | $369,029 |

| Upper Chesapeake Medical Center | 182 | 15,787 | $226,535 |

| Average | 199* | 14,201* | $247,577* |

| All Controls | |||

| Anne Arundel Medical Center | 316 | 23,397 | $448,401 |

| Baltimore Washington Medical Center | 311 | 20,705 | $359,036 |

| Doctors Community Hospital | 190 | 12,357 | $196,846 |

| Fort Washington Medical Center | 37 | 3,078 | $47,665 |

| Franklin Square Hospital Center | 393 | 30,210 | $523,816 |

| Greater Baltimore Medical Center | 355 | 20,042 | $424,052 |

| Harford Memorial Hospital | 105 | 6,751 | $100,235 |

| Holy Cross Hospital | 450 | 36,596 | $447,741 |

| Howard County General Hospital | 227 | 18,988 | $244,838 |

| Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center | 489 | 21,058 | $530,282 |

| Kernan Hospital | 132 | 3,244 | $101,563 |

| Maryland General Hospital | 180 | 6,416 | $187,278 |

| Medstar Good Samaritan Hospital | 317 | 17,098 | $419,443 |

| MedStar Harbor Hospital | 221 | 14,528 | $233,491 |

| MedStar Saint Mary's Hospital | 108 | 10,264 | $133,939 |

| MedStar Southern Maryland Hospital | 265 | 18,660 | $232,657 |

| Mercy Medical Center | 293 | 21,108 | $396,874 |

| Northwest Hospital | 230 | 13,294 | $221,889 |

| Saint Agnes Hospital | 346 | 21,679 | $474,665 |

| Shady Grove Adventist Hospital | 367 | 27,050 | $369,694 |

| Sinai Hospital of Baltimore | 434 | 28,094 | $772,605 |

| Suburban Hospital | 239 | 13,696 | $258,614 |

| The Johns Hopkins Hospital | 918 | 48,442 | $1,727,733 |

| Union Memorial Hospital | 295 | 19,525 | $514,879 |

| University of Maryland Medical Center | 771 | 38,675 | $2,523,977 |

| University of Maryland Saint Joseph Medical | 365 | 20,948 | $380,038 |

| Washington Adventist Hospital | 281 | 18,067 | $271,023 |

| Average | 320* | 19,777* | $464,566* |

All data are publicly available. Financial data from Medicare Cost report data for period ending 6/30/2011 (HCRIS 3909E) and data on total discharges are from www.ahd.com.

Indicates statistically significant difference from control hospitals, two-sample t-tests at 95% confidence.

Reports with Memorial at Easton

Descriptive statistics aggregated for the treatment and control hospitals are shown in Table 2. Patient characteristics including age, race/ethnicity, health insurance status, and the number of chronic conditions all differ significantly each year among treatment and controls. Treatment hospitals on average serve older, white patients with primary payers of Medicare, while control hospitals served more minorities and more privately insured patients.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Study Population: Total Patient Revenue, 2009-2011

| Treatment Hospitals | Rural Control Hospitals | All Control Hospitals | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 |

| Readmissions | |||||||||

| Readmission rate | 18.3 | 18.8 | 18.4 | 18.5 | 21.9a | 15.6a | 12.8a | 13.4a | 12.0a |

| Age (years) | 52.5 | 52.6 | 52.7 | 50.2a | 50.7a | 51.6a | 48.3a | 48.5a | 48.6a |

| Percent Female | 58.0 | 57.9 | 57.8 | 59.8a | 58.7a | 58.9a | 58.4a | 58.1 | 58.2a |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| White | 87.7 | 88.8 | 88.6 | 78.8a | 77.6a | 78.2a | 54.4a | 53.8a | 53.8a |

| Black | 9.4 | 8.4 | 8.6 | 14.9a | 15.0a | 14.9a | 35.3a | 35.8a | 35.7a |

| Hispanic | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 3.1a | 3.9a | 2.9a | 4.0a | 4.3a | 4.5a |

| All other races | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 3.2a | 3.4a | 3.9a | 5.9a | 5.7a | 5.6a |

| Primary Payer | |||||||||

| Medicare | 44.3 | 45.6 | 46.7 | 39.1a | 39.5a | 41.2a | 35.1a | 35.5a | 36.0a |

| Medicaid | 16.9 | 18.0 | 18.2 | 13.8a | 14.6a | 14.2a | 20.0a | 20.5a | 20.8a |

| Private Insurance | 32.8 | 31.0 | 29.3 | 40.0a | 38.9a | 37.7a | 37.7a | 36.0a | 35.4a |

| Self-pay | 3.9 | 3.4 | 3.7 | 3.5a | 3.5 | 4.0 | 4.9a | 5.3a | 5.0a |

| No payment | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 3.6a | 3.4a | 3.3a | 2.5a | 2.8a | 2.8a |

| Health Status | |||||||||

| # Chronic conditions | 5.6 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 5.2a | 5.4a | 5.7a | 4.8a | 4.9a | 5.0a |

Authors' analysis of 2009-2011 Maryland State Inpatient Databases (SID)

Indicates statistically significant difference from treatment hospitals in each year, two-sample t-tests at 95% confidence.

Although the treatment and controls hospitals differ on patient characteristics, the control hospitals are useful for identifying trends throughout the state that may affect readmissions. The readmission rate for treatment hospitals remained relatively constant over the study period, at 18.3% in 2009, 18.8% in 2010, and 18.4% in 2011. The three rural control hospitals exhibit more variation in readmission rates. The set of all control hospitals have lower readmission rates than the treatment hospitals, more stability than the rural controls, and end up slightly lower in 2011 (12%) than in 2009 (12.8%).

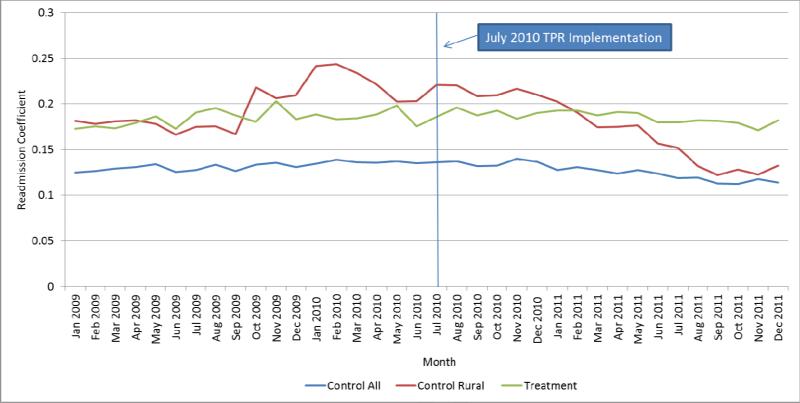

Figure 2 shows the aggregate trends in readmissions for treatment, rural controls and all control hospitals for 2009, 2010, and 2011. The data points are coefficients from unadjusted linear probability models. Readmission rates for treatment hospitals are relatively constant before and after TPR implementation. Readmissions in rural control hospitals are more variable, while readmission rates for all controls show little relatively little variability over the study period. The larger control group readmission rates suggest there were no significant factors driving change in readmissions during this time period.

Figure 2.

Monthly Readmission Rates for Treatment, Rural Controls, and all Control Hospitals: Total Patient Revenue, 2009-2011

Results from the difference-in-differences analyses are presented in Table 3. Coefficients and confidence intervals for the difference-in-differences estimates with rural controls from the linear probability model estimated with hospital fixed effects and clustered on hospital ID are in the first column. The explanatory variable of interest is the interaction term between post and treatment. The coefficient on this interaction variable is not statistically significant. The coefficient on the interaction from the linear model with all control hospitals, in the second column, is not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Difference-in-Differences Regression Estimates of the Effect of Total Patient Revenue on Hospital Readmissions

| Characteristic | Linear Probability Model with Fixed Effects Rural Controls n=374,353 (10 hospitals) | Linear Probability Model with Fixed Effects All Controls n=1,997,164 (38 hospitals) |

|---|---|---|

| Post | −.0261 | −.0079* |

| (−.0680, .0159) | (−.0157, −.0002) | |

| Post*Treatment | .0260 | .0080 |

| (−.0173, .0693) | (−.0039, .0199) | |

| Female | .0012 | −.0002 |

| (−.0159, .0183) | (−.0090, .0037) | |

| Black | .0105* | .0084* |

| (.0017, .0193) | (.0023, .0145) | |

| Hispanic | −.0048 | .0076 |

| (−.0305, .0210) | (−.0078, .0231) | |

| Other Races | − .0071* | −.0046 |

| (−.0136, −.0006) | (.0115, .0022) | |

| Age | .0004* | .0003* |

| (.0001, .0008) | (.0001, .0005) | |

| Income Quartile 1 | −.0012 | −.0114 |

| (−.0224, .0248) | (−.0194, −.0034) | |

| Income Quartile 2 | −.0052 | −.0063 |

| (−.0257, .0152) | (−.0145, .0020) | |

| Income Quartile 3 | −.0071 | −.0037 |

| (−.0246, .0104) | (−.0084, .0009) | |

| Self-Pay | .0127 | −.0017 |

| (−.0017, .0272) | (−.0212, .0177) | |

| No Payment | .0031 | −.0075 |

| (-.0113, .0176) | (−.0333, .0184) | |

| Medicaid | .0479* | .0325* |

| (.0304, .0654) | (.0235, .0415) | |

| Medicare | .0290* | .0234* |

| (.0132, .0448) | (.0154, .0316) | |

| # Chronic Conditions | .0143* | .0123* |

| (.0102, .0185) | (.0100, .0147) | |

| Constant | .0693* | .0501* |

| (.0329, .1056) | (.0331, .0672) |

Author's calculations using the 2009-2011 Maryland State Inpatient Databases (SID). Robust standard errors are clustered by hospital.

p-value ≤.05

The linear probability model results show readmissions vary by demographics, socio-economic characteristics, and presence of chronic conditions. In the first model with rural controls, African Americans (coeff=.0105, p≤.05) were more likely and other races (coeff=-.0071, p≤.05) were less likely than whites to have a readmission. Age was positively associated with readmissions (coeff=.0004, p≤.05). The probability of readmissions was higher for patients whose stays were paid by Medicare (coeff=.0290, p≤.05) and Medicaid (coeff=.0479, p≤.05) relative to private insurance. The number of chronic conditions indicated at discharge (coeff=.0143, p≤.05) was positively associated with readmission. The estimates from the model with all control hospitals had the same sign and significance for these same variables, except the coefficient on other races was no longer statistically significant.

Discussion

Our results show that in the 18 months following implementation of the program, TPR is not associated with decreases in the probability of a patient readmission. This is consistent with recent findings from one hospital participating in the TPR program, Western Maryland Health System. The hospital found that their readmissions rate remained high at 16% in 2011 but dropped significantly to 9% in 2012.17 The program has enable hospitals to enhance outpatient services, such as opening primary care clinics, diabetes clinics, behavioral health clinics, wound care centers, and following up with discharged patients.17

There is much to be learned about innovate payment mechanisms, so policymakers, organizations providing health care, and state health departments can benefit from this analysis of Maryland's experience with the TPR program. TPR is unique; rather than national policy that penalizes hospitals with high readmission rates that may cause hospitals to forgo quality,21 TPR works to create positive financial incentives to reduce unnecessary admissions and readmission rates while monitoring quality. The incentives for hospitals to treat patients under TPR are different than under a prospective payment system like Medicare. The financial incentives in Medicare are such that hospitals will continue to admit patients but reduce length of stay, whereas incentives under TPR encourage hospitals to invest in outpatient infrastructure in the community to keep patients out of the hospital altogether.

The difference-in-differences approach we use provides a strong framework for analyzing the TPR program. It attributes a change in readmissions to the TPR program only if the change is concurrent with implementation of the program, and if the changes in readmissions in participating hospitals differ from hospitals that did not participate. The hospital fixed effect framework provides the opportunity to focus on changes within each hospital, avoiding bias due to differences in the unobservable characteristics of these rural hospitals.35

This analysis has several limitations. The TPR program demonstrations were targeted to rural hospitals because of their defined, non-overlapping service areas, so participation in TPR was not randomly assigned, and is not intended for urban and suburban hospitals. Maryland is a relatively small state geographically, with 46 non-federal, short-term acute hospitals, which limits the sample of rural hospitals that can appropriately be used for controls. The HCUP does not contain readmission data for neighboring states; the closest state with the readmit variable in the SID is New Jersey. There are also limitations to the difference-in-differences model,39which we attempt to address by clustering standard errors at the hospital level.

Readmissions data for the state of Maryland are not always readily accessible.23 Maryland uses its own penalty system for readmissions32 so it is exempt from the national Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program and penalties instituted by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and mandated by the Affordable Care Act. Data from the Dartmouth Atlas do not report aggregate readmission data for Maryland.23 Thus, the tabulations we calculate from the HCUP data can't be cross-verified. We view this as a potential limitation because we had to remove two hospitals from our initially selected rural control group since neither hospital reported any readmissions for either one of the calendar years or the entire three year sample. Despite these limitations, the results have important implications for hospitals participating in the TPR program, hospitals considering participation, and local health systems across the country.

Conclusions

This paper provides early evidence effects of the TPR program on rural hospital readmissions. The program continues through at least 2013, so this is not a comprehensive evaluation of the program. The results show that participating hospitals did not reduce their readmissions in the first 18 months of the program. The program targeted rural hospitals, perhaps because of their clearly defined service areas, but also perhaps because rural hospitals do not have the same integrated structure and capacity as urban hospitals, and global budgeting provides them the incentive and financial stability to undertake systematically these efforts. Streamlining outpatient and inpatient services and other steps towards integration take time, so it is reasonable to expect that the TPR program did not instantaneously reduce hospital readmission rates.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to Melinda Beeuwkes Buntin, anonymous reviewers, and seminar participants at University of Minnesota Medical Industry Leadership Institute, George Mason University, AcademyHealth, and the International Health Economics Association in Sydney, Australia for valuable feedback. We gratefully acknowledge support from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Center for Child Health and Human Development grant R24-HD041041, Maryland Population Research Center. We thank Jack Meyer for guidance and support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Karoline Mortensen, Department of Health Services Administration 3310 School of Public Health Building University of Maryland College Park, MD 20742-2611 301 405-6545.

Chad Perman, Health Management Associates 1350 Connecticut Ave. NW, Suite 605 Washington, D.C. 20036 202 785-3669 cperman@healthmanagement.com.

Jie Chen, Department of Health Services Administration 3310 School of Public Health Building University of Maryland College Park, MD 20742-2611 301 405-9053 jichen@umd.edu.

References

- 1.Martin AB, Lassman D, Washington B, Catlin A. Growth in US health spending remained slow in 2010; health share of Gross Domestic Product was unchanged from 2009. Health Aff. 2012;31(1):208–219. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1135. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenthal MB. Beyond pay for performance — emerging models of provider-payment reform. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359(12):1197–1200. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0804658. doi:10.1056/NEJMp0804658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine . The pathway to continuously learning health care in America. Washington, DC: 2012. Best care at lower cost. Available at: http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2012/Best-Care/BestCareReportBrief.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altman SH, Cohen AB. The need for a national global budget. Health Affairs. 1993;12(Supplement 1):194–203. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.12.suppl_1.194. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.12.suppl_1.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor M. Experiments in payment. Hospitals & Health Networks. 2008 Available at: http://www.hhnmag.com/hhnmag/jsp/articledisplay.jsp?dcrpath=HHNMAG/Article/data/09SEP2008/0809HHN_FEA_CoverStory&domain=HHNMAG. [PubMed]

- 6.Murray R. The case for a coordinated system of provider payments in the United States. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 2012;37(4):679–695. doi: 10.1215/03616878-1597493. doi:10.1215/03616878-1597493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray R. Setting hospital rates to control costs and boost quality: the Maryland experience. Health Aff. 2009;28(5):1395–1405. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.1395. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reinhardt U. A Modest Proposal On Payment Reform. Health Affairs Blog. 2009 Available at: http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2009/07/24/a-modest-proposal-on-payment-reform/

- 9.Chernew ME, Hong JS. Commentary on the spread of new payment models. Healthcare. 2013;1(1–2):12–14. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2013.04.009. doi:10.1016/j.hjdsi.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song Z, Safran DG, Landon BE, et al. The “Alternative Quality Contract,” based on a global budget, lowered medical spending and improved quality. Health Aff. 2012 doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0327. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Health Services Cost Review Commission Report to the Governor. Fiscal year. 2011 2011. Available at: http://www.hscrc.state.md.us/documents/HSCRC_PolicyDocumentsReports/AnnualReports/GovReport2011_MD_HSCRC.pdf.

- 12.Bazinsky K, Herrera L, Sharfstein J. Toward innovative models of health care and financing: matchmaking in Maryland. JAMA. 2012;307(12):1261–1262. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.364. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Innovations: Maryland Total Patient Revenue for hospitals. 2012 Available at: http://dhmh.maryland.gov/innovations/SitePages/maryland-total-patient-revenue.aspx.

- 14.Health Services Cost Review Commission Agreement between the Health Services Cost Review Commission and hospital regarding the adoption of the total patient revenue system. 2010 Available at: http://www.hscrc.state.md.us/documents/HSCRC_Initiatives/TPR/2012-04-24_TPR_AgreementTemplate-Website.pdf.

- 15.Ryan AM, Damberg CL. What can the past of pay-for-performance tell us about the future of Value-Based Purchasing in Medicare? Healthcare. 2013;1(1–2):42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2013.04.006. doi:10.1016/j.hjdsi.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Appleby J. Hospital effort could reduce readmissions. The Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/12/06/AR2010120607108.html. Published December 7, 2010.

- 17.Porter E. Lessons in Maryland for costs at hospitals. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/28/business/economy/lessons-in-maryland-for-costs-at-hospitals.html. Published August 27, 2013.

- 18.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360(14):1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joynt KE, Jha AK. Who has higher readmission rates for heart failure, and why? implications for efforts to improve care using financial incentives. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4(1):53–59. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.950964. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.950964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare and the health care delivery system. 2012 Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/documents/Jun12_EntireReport.pdf.

- 21.Joynt KE, Jha AK. Thirty-Day readmissions — truth and consequences. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366(15):1366–1369. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1201598. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1201598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benbassat J TM. Hospital readmissions as a measure of quality of health care: Advantages and limitations. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(8):1074–1081. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.8.1074. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.8.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodman D, Fisher ES, Chang C-H. The revolving door: a report on U.S. hospital readmissions. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2013. Available at: http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/reports/2013/rwjf404178. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berenson RA, Paulus RA, Kalman NS. Medicare's Readmissions-Reduction Program — A Positive Alternative. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366(15):1364–1366. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1201268. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1201268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krumholz H, Frakt A, Carroll A. Harlan Krumholz on hospital readmissions. The Incidental Economist. 2013 Available at: http://theincidentaleconomist.com/wordpress/harlan-krumholz-on-hospital-readmissions/

- 26.Government Accountability Office Rochester's community approach yields better access, lower costs. 1993 Available at: http://www.gao.gov/assets/220/217472.pdf.

- 27.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality HCUP databases. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) 2013 Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/sidoverview.jsp. [PubMed]

- 28.Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Maryland's rural hospitals. 2013 Available at: http://mhcc.dhmh.maryland.gov/workgroup/Documents/Rural_Health/071713_List_of_Maryland%27s_Rural_Hospitals.pdf.

- 29.Ports S. The Maryland Hospital Rate Setting System Update. Maryland Health Services Cost Review Commission; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality SID: Description of data elements. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/vars/siddistnote.jsp?var=readmit.

- 31.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality HCUP NIS description of data elements: bedsize of hospital. 2008 Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/vars/hosp_bedsize/nisnote.jsp.

- 32.Health Services Cost Review Commission Draft staff recommendation on rate methods and financial incentives relating to reducing Maryland preventable hospital readmissions. 2011 Available at: http://www.hscrc.state.md.us/documents/HSCRC_Initiatives/QualityImprovement/MHPR/2011/01-05-11/MHPR_Revised_Draft_Final_2011-1-5.pdf.

- 33.Health Services Cost Review Commission 473rd meeting of the Health Services Cost Review Commission. 2010 Available at: www.hscrc.state.md.us/event_files/HSCRC_PreCommMeet12-08-10.pdf.

- 34.Mortensen K. Copayments did not reduce Medicaid enrollees’ nonemergency use of emergency departments. Health Affairs. 2010;29(9):1643 –1650. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0906. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ho V, Ku-Goto M-H, Jollis JG. Certificate of need (CON) for cardiac care: controversy over the contributions of CON. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(2p1):483–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00933.x. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00933.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silow-Carroll S. Reducing hospital admissions: lessons from top hospitals. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/~/media/Files/Publications/Case%20Study/2011/Apr/1473_SilowCarroll_readmissions_synthesis_web_version.pdf.

- 37.Norton E. Interaction terms in logit and probit models. 2007 Available at: http://www.unc.edu/~enorton/InteractionAcademyHealth2004.pdf.

- 38.Hockenberry JM, Burgess JF, Glasgow J, Vaughan-Sarrazin M, Kaboli PJ. Cost of readmission. Medical Care. 2013;51(1):13–19. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31825c2fec. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31825c2fec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bertrand M, Duflo E, Mullainathan S. How Much Should We Trust Differences-In- Differences Estimates? The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2004;119(1):249–275. doi:10.1162/003355304772839588. [Google Scholar]