Abstract

Exosomes, nano-sized membrane vesicles, are released by various cells and are found in many human body fluids. They are active players in intercellular communication and have immune-suppressive, immune-regulatory, and immune-stimulatory functions. EBV is a ubiquitous human herpesvirus that is associated with various lymphoid and epithelial malignancies. EBV infection of B cells in vitro induces the release of exosomes that harbor the viral latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1). LMP1 per se mimics CD40 signaling and induces proliferation of B lymphocytes and T cell–independent class-switch recombination. Constitutive LMP1 signaling within B cells is blunted through the shedding of LMP1 via exosomes. In this study, we investigated the functional effect of exosomes derived from the DG75 Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line and its sublines (LMP1 transfected and EBV infected), with the hypothesis that they might mimic exosomes released during EBV-associated diseases. We show that exosomes released during primary EBV infection of B cells harbored LMP1, and similar levels were detected in exosomes from LMP1-transfected DG75 cells. DG75 exosomes efficiently bound to human B cells within PBMCs and were internalized by isolated B cells. In turn, this led to proliferation, induction of activation-induced cytidine deaminase, and the production of circle and germline transcripts for IgG1 in B cells. Finally, exosomes harboring LMP1 enhanced proliferation and drove B cell differentiation toward a plasmablast-like phenotype. In conclusion, our results suggest that exosomes released from EBV-infected B cells have a stimulatory capacity and interfere with the fate of human B cells.

Exosomes are nano-sized membrane vesicles (40–100 nm in diameter) that are formed by inward budding of the endosomal membrane within multivesicular bodies (1). Upon fusion of the multivesicular body membrane with the plasma membrane, exosomes are released into the environment where they can exert their function as immune mediators on bystander cells (2). Many cell types, including immune cells such as dendritic cells (DCs) and B and T cells, release exosomes, and they are found in human body fluids, such as plasma, saliva, urine, and breast milk (3). Cellular activation is needed to induce exosome release by primary immune cells, in particular primary B cells (4). The physiological role of exosomes remains to be fully elucidated, but many studies provide strong evidence that they are active players in intercellular communication as a result of their immune-suppressive, immune-regulatory, and immune-stimulatory functions (5–8).

EBV is a ubiquitous human γ herpesvirus that successfully coevolved with its host to persist in a latent stage within isotype-switched memory (IgD−CD27+) and nonswitched marginal zone (IgD+CD27+) B cells (9–11). It is the causative agent of infectious mononucleosis and is associated with lymphoid and epithelial malignancies, such as posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders, Hodgkin’s disease, Burkitt’s lymphoma, and nasopharyngeal carcinoma (12). Intriguingly, EBV is also suspected to contribute to autoantibody production in patients suffering from autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, multiple sclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis (13). In vitro EBV-transformed B cells (lymphoblastoid cell line [LCL]) constitutively release exosomes that induce Ag-specific MHC class II–restricted T cell responses (14). Moreover, exosomes released by LCLs harbor the EBV latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) (15). LMP1 function mimics CD40 signaling and thereby ensures EBV persistence within the B cell compartment by promoting apoptotic resistance, proliferation, and immune modulation (16). LMP1 is constitutively active and signals in a ligand-independent fashion through mitogen-activated kinases, NF-κB, and the JAK/STAT pathway via TNFR-associated factors (17). Thus, LMP1 expression must be tightly regulated during EBV infection. Recently, it was demonstrated that constitutive LMP1 signaling within B cells is blunted through the shedding of LMP1 via exosomes (18). Therefore, LMP1 exosomes released by infected cells during EBV-associated diseases might contribute to clinical features seen in patients with lymphoproliferative disorders or autoimmune diseases. Recombinant LMP1 was shown to directly suppress activated T cells, and exosomes released by EBV-infected nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells harbor LMP1 (19, 20). Both studies suggest that LMP1 secreted by EBV+ tumor cells might mediate immunosuppressive effects on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. However, a potential effect of LMP1 exosomes on B cells equipped with all CD40-signaling molecules has not been addressed.

In vivo administration of OVA-loaded DC-derived exosomes is able to induce Ag-specific CD4+ T cell responses through a B cell–dependent mechanism, suggesting exosomes as Ag shuttle systems for delivery to B cells (21). In this study, we examined whether B cell–derived exosomes are conveyers of intercellular communication by interfering with the fate of human B cells. To mimic exosomes released during EBV infection or EBV-associated diseases, we took advantage of the human EBV− DG75 Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line and its derived sublines (LMP1 transfected and EBV infected) as a stable source of human B cell–derived exosomes carrying LMP1 or not. We addressed their functional potency and tested the hypothesis of whether LMP1 transferred via exosomes exerts its function after binding and internalization by B cells. In this study, we demonstrate that exosomes harboring LMP1 were released during primary EBV infection of B cells and that similar physiological concentrations were found on exosomes secreted from DG75-LMP1 cells. When exposed to DG75 exosomes, human peripheral B cells gained the capacity to proliferate, upregulated the expression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), and induced intronic γ1 exon–C region of the H chain μ(Iγ1-Cμ) circle and Iγ1/2-Cγ1 germline transcripts. Additionally, exosomes harboring LMP1 induced differentiation toward a plasmablast-like phenotype. Altogether, our study highlights the B cell–stimulatory capacity of exosomes released by EBV-infected B cells. We propose that clinical features observed in patients with EBV-associated diseases, such as lymphoproliferative disorders or autoimmune diseases, might be intensified by the presence and action of these exosomes.

Materials and Methods

B cell lines

The following B cell lines were used for exosome preparations: EBV− Burkitt’s lymphoma DG75-CO (control), DG75-LMP1 (stably transfected with LMP1), DG75-EBV (EBV infected) (22–24), BJAB, and lymphoblastoid cell line LCL1 (25). Cells were tested routinely and were mycoplasma free (VenorGem; Minerva Biolabs); they were cultured (5 × 105 cells/ml) in complete medium consisting of RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies, Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated and exosomedepleted FCS (HyClone, Nordic Biolab; FCS was diluted with RPMI 1640 medium to 30% and centrifuged for 16 h at 100,000 × g at 4°C), 2 mM L-glutamine (HyClone), 100 IU/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin (HyClone), and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C, 5% CO2. After 3 d, the culture supernatants were collected for exosome isolation.

Exosome isolation and phenotyping

B cell–derived exosomes (DG75-COex, DG75-LMP1ex, DG75-EBVex, BJABex, and LCL1ex) were isolated by differential centrifugation, as previously described (25). The protein concentrations of exosomes were determined using the Bio-Rad Dc assay, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Three batches of exosome preparations (20 µg) were tested for endotoxin levels using the Limulus Amebocyte Lysate assay (Charles River Laboratories), and the following mean levels were detected: DG75-COex (0.253 EU/ml), DG75-LMP1ex (0.076 EU/ml), and DG75-EBVex (0.273 EU/ml). Exosomes were phenotyped by flow cytometry after adsorption onto 4.5-µm precoated anti–MHC class II Dynabeads (clone HKB1, custom made; Dynal Biotech ASA/Invitrogen) overnight at room temperature at a concentration of 0.8 µg exosomes/9.5 × 105 Dynabeads for each staining in PBS containing 0.1% BSA and 0.01% sodium azide. Exosomes coated on beads were stained with mouse monoclonal FITC-conjugated Abs (BD Pharmingen or BioLegend/Nordic Biosite) against human CD9 (M-LI3), CD19 (4G7), CD21 (B-ly4), CD23 (M-L233), CD40 (5C3), CD63 (MEM-259), CD80 (2D10), CD81 (JS-81), CD86 (2331), HLA-DR (L243), HLA-ABC (W6/32), IgG1 (MOPC-21), and IgG2a (MOPC-173). A total of 5 × 103 exosome-coated beads was acquired using a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson), and data were analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar).

Nanoparticle tracking analysis

The size distributions of B cell–derived exosome preparations were analyzed by measuring the rate of Brownian motion using a NanoSight LM10 system, equipped with a fast video capture and particle-tracking software NTA 2.2. Exosome preparations were measured in triplicates at a concentration of 5 × 108 particles/ml.

Immunoblot analysis

DG75 cells (2 × 106) or exosomes (10 µg) were separated by SDS-PAGE (10%) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore). A total of 1 × 106 negatively selected B cells was incubated (37°C, 5% CO2) for 15 h with 100 µg BJABex or LCL1ex in 500 µl complete medium (48-well plate; Becton Dickinson). B cells were washed three times with PBS to remove unbound exosomes and incubated for the remaining 24 or 48 h in complete medium (37°C, 5% CO2). Cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE (NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris Gel; Life Technologies) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore). Membranes were stained according to the manufacturer’s instructions with Abs against LMP1 (CS. 1.4; Dako), EBNA2 (PE2; Novocastra), HLA-DR (TAL.1B5; Dako), CD81 (H-121; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and β-actin (I-19; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Membranes were visualized with ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare) and exposed on CL-XPosure films (Nordic Biolabs).

Binding pattern of exosomes to B cells and monocytes in PBMCs

PBMCs were isolated from buffy coat preparations of healthy blood donors (Blood Transfusion Center Solna, Stockholm, Sweden) through Ficoll-Paque Plus separation (GE Healthcare), as previously described (25). Exosomes (10 µg) were stained with a PKH67 Green Fluorescent Cell Linker Kit (Sigma-Aldrich), as previously described (25). Prefiltered (0.22-µm filter) PKH67-stained exosomes were added to PBMCs (2.5 × 105) for 1, 2, or 4 h at 37°C, 5% CO2. A PKH67 dye pellet centrifuged in parallel with labeled exosomes served as negative background control. PBMCs were stained with the following Abs to distinguish B cells (CD3−CD19+HLA-DR+), monocytes (CD3−CD14+HLA-DR+), and T cells (CD3+CD19−): CD19-ECD (HD237; B4 lytic; Beckman Coulter); HLA-DR–PE-Cy5 (TU36; BD Biosciences), CD14-PE (HCD14; BioLegend), and CD3 Pacific Blue (SP34-2; BD Biosciences). Exosome binding to live PBMCs (LIVE/DEAD Fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain Kit; Invitrogen) was measured (~150,000 events) using an LSR Fortessa (BD) or FACSAria (BD) and analyzed using FlowJo software.

Human primary B cell isolation

B cells were isolated from PBMCs of healthy blood donors (Blood Transfusion Center Solna or Banc de Sang i Teixits, Barcelona, Spain). B cells were isolated either through negative selection (B Cell Isolation Kit II; Miltenyi Biotec) or by positive selection using biotinylated anti-IgD Ab (Southern Biotech) and Anti-Biotin MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec). The purity and B cell composition of each donor were assessed by flow cytometry, staining for CD19-allophycocyanin (HIB19; BD), IgD-FITC (IA6-2; BD), CD38-PECy (HB7; BD), CD27-PE (M-T271; BD), and DAPI (5.7 µM; Sigma-Aldrich) using an LSR II or Fortessa (BD) and analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar).

EBV infection of primary human B cells

Negatively selected B cells were incubated with B95-8 virus–containing supernatant for 1.5 h, with shaking every 30 min (37°C, 5% CO2). Thereafter, the cells were washed with PBS (300 × g, 10 min) and resuspended in complete medium at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/ml. Three days postinfection, supernatants were collected and centrifuged at 3000 × g for 30 min before storage at −80°C.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy analysis

A total of 3 × 105 negatively selected B cells (purity > 90%) was incubated in 250 µl complete medium with 40 µg PKH67-labeled exosomes in polypropylene tubes (Becton Dickinson) for 4 h at 37°C (5% CO2). Cells were washed twice with PBS (400 × g, 5 min) and fixed with 2% formaldehyde (Merck) for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were washed twice and incubated with purified human Ig (Sigma-Aldrich) and anti-CD19 (HIB19; BD Pharmingen) for 30 min at room temperature. Washed cells were incubated with a secondary Ab Alexa Fluor 564 (Invitrogen) for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were washed and centrifuged (Cytospin3; Shandon) on microscopy slides (Menzel-Gläser), and VECTASHIELD HardSet Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories) was used. For each sample, 150 cells were analyzed for surface-bound or internalized PKH67-labeled exosomes by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) (Leica TCS SP2 AOBS).

B cell apoptosis assay

Negatively selected B cells were used with a purity > 93% (n = 4; two donors in Barcelona and two donors in Stockholm). A total of 1.8 × 105 B cells was cultured in complete medium for 24 h in 200 µl (96-well round-bottom plates; BD). Cells were either left unstimulated or stimulated with soluble MegaCD40L (100 ng/ml; Enzo Life Sciences) and IL-21 (50 ng/ml; Invitrogen) or with 15 µg B cell–derived exosomes/well. Subsequently, B cells were incubated with purified human Ig (Sigma-Aldrich) and stained with anti-CD19–allophycocyanin (HIB19; BD Pharmingen) for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were washed with PBS (350 × g, 5 min) and stained with an FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Pharmingen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A total of 2 × 104 cells was acquired by flow cytometry (LSR II or Fortessa; BD) and analyzed with FlowJo software. Cells were gated as follows: forward scatter (FSC) area (FSC-A) versus side scatter (SSC) area (SSC-A), FSC-A versus FSC height (FSC-H) for doublet exclusion, CD19+. The morphology of cells was documented using a light microscope (Axiovert 25; Zeiss) and Leica software (Zeiss).

Proliferation of PBMCs

PBMCs were isolated from healthy blood donors (Blood Transfusion Center Solna). A total of 10 × 106 PBMCs was labeled at room temperature with 1.5 µM CFSE (CellTrace CFSE Cell Proliferation Kit; Invitrogen) for 3 min. Labeled PBMCs were washed three times with complete medium (400 × g, 7 min) and cultured in complete medium at a density of 2.5 × 105 cells/200 µl (96-well flat bottom plates; BD). PBMCs were either left unstimulated (unstimulated control [co]) or stimulated with 1.5% PHA (PHA-M; Life Technologies Life Technologies) or 25 µg DG75-COex, DG75-LMP1ex, or DG75-EBVex per well. After 5 d of culture (37°C, 5% CO2), cells were incubated with purified human Ig (Sigma-Aldrich) and stained for CD3-allophycocyanin (UCHT1L; BioLegend) and CD19–Texas Red (B4 [LYTIC]-ECD, CYTO-STAT; Beckman Coulter). DAPI (5.7 µM; Sigma-Aldrich) was used as live/dead marker. Cells were acquired using an LSR II or Fortessa (BD), and data were analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar). Cells were gated as follows: FSC-A-SSC-A, FSC-A-FSC-H, DAPI− (alive).

B cell proliferation and differentiation

B cells were isolated (negative selection), and purity was > 92% (n = 4; two donors from Barcelona and two donors from Stockholm). A total of 2–9 × 106 B cells was labeled for 5 min at room temperature with 1.25 µM CFSE (CellTrace CFSE Cell Proliferation Kit; Invitrogen). Labeled B cells were washed three times (350 × g, 7 min) and cultured in complete culture medium at a density of 1.5 × 105 cells/200 µl (96-well round-bottom plates; BD). B cells were either left unstimulated or stimulated with IL-21 (100 ng/ml; Invitrogen), MegaCD40L (500 ng/ml; Enzo Life Sciences), or 5 or 25 µg exosomes/well. After 5 d of cultivation (37°C, 5% CO2), cells were incubated with purified human Ig (Sigma-Aldrich) and subsequently stained with CD19-allophycocyanin (HIB19), CD20-PerCP-Cy5.5 (2H7) and CD38-PeCy (HB7; all from BD). DAPI (5.7 µM; Sigma-Aldrich) was used as live/dead marker. Cells were analyzed with flow cytometry and gated as follows: FSC-A-SSC-A, FSC-A-FSC-H, DAPI− (alive), CD19+.

Quantitative real-time PCR

IgD+ B cells were used with a purity > 96% (two donors from Barcelona). B cells (1.2 × 105/200 µl in 96-well round-bottom plates; BD) were cultivated for 3 d in complete culture medium (37°C, 5% CO2) and either left unstimulated or stimulated with soluble MegaCD40L (500 ng/ml; Enzo Life Sciences) and IL-21 (100 ng/ml) or with 12.5 µg DG75 exosomes. RNA from 5 × 105 B cells was extracted (High Pure RNA Isolation Kit; Roche) and transcribed into cDNA (TaqMan Gold RT-PCR Kit; Applied Biosystems). Expression of AICDA (forward, 5′-AGAGGCGTGACAGTGCTACA-3′; reverse, 5′-TGTAGCGGAGGAAGAGCAAT-3′) was investigated using a Bio-Rad CXF96 cycler. For each reaction, 250 nM primers, 10 ng cDNA, and 13 µl iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) were used and run for 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. All reactions were standardized to the expression of EF-1α (forward, 5′-CTGAACCATCCAGGCCAAAT-3′; reverse, 5′-GCCGTGTGGCAATCCAAT-3′) and GAPDH (forward, 5′-GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTCAAC-3′; reverse, 5′-CAGAGTTAAAAGCAGCCCTGGT-3′). Primers were purchased from TAG Copenhagen A/S.

Ig class-switch recombination analysis

RNA was extracted (High Pure RNA Isolation Kit; Roche) from 5 × 105 positively selected IgD+ B cells. The RNA was retrotranscribed (TaqMan Gold RT-PCR Kit; Applied Biosystems), and cDNAwas used as a template to amplify isotype-specific I-Cμ circle transcripts (Iγ1/2-Cμ) and germline IH-CH transcripts (Iμ-Cμ and Iγ1/2-Cγ1) by PCR. Amplified PCR products were separated in a 1.5% agarose gel and transferred overnight onto nylon membranes (Amersham Biosciences) by Southern blot. Membranes were hybridized with appropriate radiolabeled probes, as reported (26, 27).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism version 5.02 (GraphPad). The D’Agostino–Pearson omnibus test was used as a normality test. Normally distributed data were analyzed further using one-way ANOVA and the parametric unpaired Student t test, whereas nonnormally distributed data were analyzed using the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test. The p values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

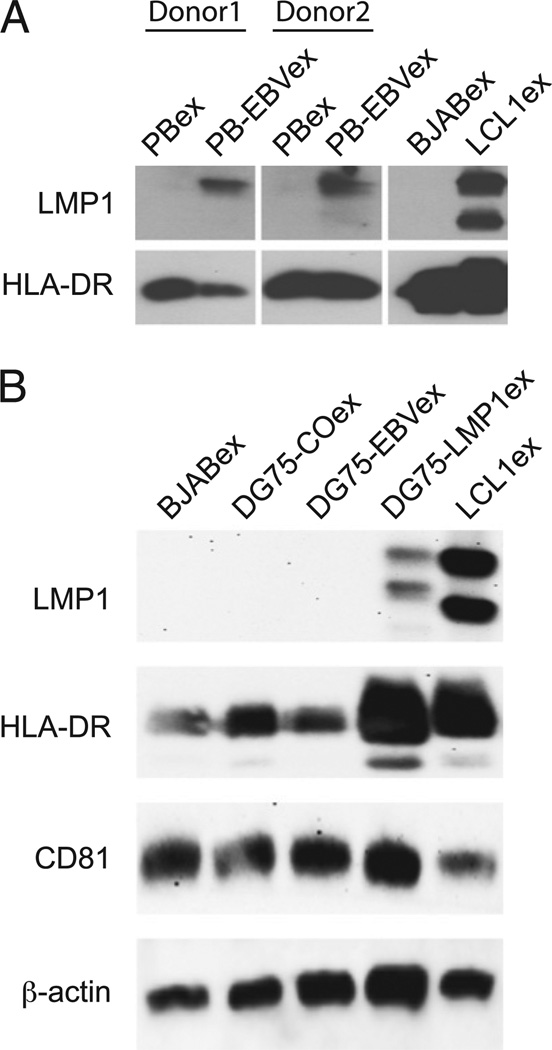

DG75-LMP1ex contain physiological levels of LMP1 as found on exosomes released during primary EBV infection

Exosomes from monoclonal EBV-transformed B cell lines (LCLs) contain high levels of LMP1 (19). However, whether these expression levels are physiological and are achieved during natural EBV infection remained to be elucidated. Therefore, we infected human peripheral B cells with EBV and isolated exosomes from cell culture supernatants 3 d postinfection. LMP1 levels in exosomes from uninfected or EBV-infected peripheral B cells (PBex and PB-EBVex) from two donors were compared with levels found in exosomes derived from the EBV− Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line (BJABex) and LCL1 cells (LCL1ex). Immunoblot analysis revealed that PB-EBVex from both donors harbored LMP1 (Fig. 1A). However, these levels were much lower than those in LCL1ex. Next, we screened exosomes from B cell lines in search of exosomes that would harbor lower amounts of LMP1, thereby better reflecting the physiological concentration observed in PB-EBVex. We found that exosomes from the human DG75 Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line stably transfected with LMP1 (DG75-LMP1ex) harbored lower amounts of LMP1 compared with LCL1ex (Fig. 1B). No LMP1 expression was found in BJABex, the EBV− DG75 Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line (DG75-COex), or its EBV-transformed subline (DG75-EBVex). LMP1 levels in exosomes reflected expression levels in the corresponding B cell line (Supplemental Fig. 1A). In line with their endosomal origin, all B cell–derived exosomes contained tetraspanin CD81 and HLA-DR molecules. Thus, we concluded that exosomes from DG75-LMP1 harbor similar LMP1 levels as those observed during primary EBV infection and that DG75 exosomes were suitable to elucidate their potential effect on human B cells.

FIGURE 1.

DG75-LMP1ex contain physiological levels of LMP1, as found on exosomes released during primary EBV infection. (A) Peripheral B cells from two donors were either left untreated or infected with EBV and cultured for 3 d. The corresponding exosomes, PBex and PB-EBVex, were isolated and analyzed for LMP1 and HLA-DR expression by immunoblot. Expression levels of 10 µg PBex and PB-EBVex from donor 1 and 20 µg of PBex and PB-EBVex from donor 2 were compared with 10 µg each of BJABex and LCL1ex. (B) Exosomes (10 µg) isolated from the Burkitt’s lymphoma cell lines BJAB (BJABex), DG75 (DG75-COex), LMP1 transfected (DG75-LMP1ex), and EBV transformed (DG75-EBVex), as well as from a lymphoblastoid cell line (LCL1ex), were analyzed by immunoblot for their expression levels of LMP1, HLA-DR, CD81, and β-actin. One representative immunoblot of four is shown.

DG75 exosomes harbor phenotypic differences that reflect the phenotype of their B cell line

Next, we further compared the phenotype of the DG75 cell lines (DG75-CO, DG75-LMP1, and DG75-EBV) and their corresponding exosomes (DG75-COex, DG75-LMP1ex, and DG75-EBVex). Cells were analyzed directly by flow cytometry, whereas, because of their small size, exosomes were first coated onto anti–MHC class II Dynabeads (Fig. 2A). In general, exosomes had a similar phenotype as their originating cell line (Fig. 2B). However, quantitative differences in surface molecules were observed when comparing DG75-COex, DG75-LMP1ex, and DG75-EBVex. For instance, DG75-LMP1ex harbored significantly more HLA-DR molecules than did DG75-COex and DG75-EBVex (Fig. 2B), consistent with the increased HLA-DR expression detected by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 1B). Additionally, a significant increase in HLA-ABC expression was observed on DG75-LMP1ex and DG75-EBVex compared with DG75-COex. As expected, all DG75 exosomes were enriched for the tetraspanins CD63 and CD81 (Fig. 2C). However, no CD21 or CD23 expression was detected on DG75 exosomes or their corresponding cells (Supplemental Fig. 1B). Finally, the size of DG75 exosomes was verified by nanoparticle tracking analysis (Fig. 2D). Exosome preparations of DG75-COex, DG75-LMP1ex, and DG75-EBVex displayed a population of vesicles with similar size peaks without any significant difference (p = 0.382): DG75-COex (122 ± 14.0 nm), DG75-LMP1ex (122 ± 8.5 nm), and DG75-EBVex (116 ± 16.3 nm). Altogether, these data indicated that DG75 exosomes harbor phenotypic differences but reflect the phenotype of their cellular source.

FIGURE 2.

DG75 exosomes harbor phenotypic differences that reflect the phenotype of their B cell line. (A) Schematic diagram of direct phenotypic characterization of different DG75 B cell lines and indirect phenotyping of their exosomes after binding onto anti–MHC class II Dynabeads by flow cytometry. (B) The expression pattern on cells and exosomes of HLA-ABC, HLA-DR, CD19, CD40, CD80, and CD86 and (C) of the tetraspanins CD63 and CD81 on exosomes shown as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) ratio divided by the isotype control. Horizontal lines indicate mean values from 3–5 independent experiments for DG75 B cells (DG75-CO, DG75-LMP1, and DG75-EBV) and from 5–20 independent experiments for the exosomes (DG75-COex, DG75-LMP1ex, and DG75-EBVex). (D) Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NanoSight). The mean particle size distribution from three different exosome batches for DG75-COex, DG75-LMP1ex, and DG75-EBVex. *p ≤ 0.05, ***p ≤ 0.001, Mann–Whitney U test. MVB, multivesicular body.

DG75 exosomes bind with similar efficiency to B cells in PBMCs and are internalized by B cells

To elucidate a functional effect of DG75-LMP1ex on human B cells, we first addressed whether different DG75 exosomes have similar binding capacities to human B cells. Therefore, exosomes were stained with the lipid dye PKH67, and their binding pattern to PBMCs was analyzed after 1, 2, and 4 h by multicolor flow cytometry (Fig. 3A). All DG75 exosomes showed increased binding to B cells and monocytes over time, and no statistical difference among DG75-COex, DG75-LMP1ex, and DG75-EBVex was detected (Fig. 3B). After 4 h, the binding efficiency for DG75 exosomes to B cells was 55–70% and to monocytes was 79–89%. Consistent with our previous study on exosomes derived from the LCL1 cell line, DCs, and human breast milk (25), all three DG75 exosomes showed a very low binding efficiency to T cells (<3%; data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

DG75 exosomes bind with similar efficiency to B cells in PBMCs and are internalized by B cells. (A) Gating strategy used to assess binding of PKH67-labeled exosomes, after 4 h, to human B cells and monocytes within PBMCs, showing representative contour plots. (B) Binding pattern of PKH67-labeled DG75-COex, DG75-LMP1ex, and DG75-EBVex, after 1, 2, or 4 h, to B cells and monocytes. Results from three (1 h) and five (2 or 4 h) independent experiments are shown. Horizontal lines represent the mean. (C) Human primary B cells were incubated for 24 or 48 h with no exosomes (−), BJABex, or LCL1ex, and cell lysates were assessed by immunoblot analysis for expression of LMP1 and β-actin. One representative experiment of three is shown. (D) Confocal microscopy analysis of anti-CD19+ (red) B cells incubated with PKH67-labeled (green) DG75 exosomes for 4 h at 37°C. Areas in the white boxes are shown in the Merge column. Arrows point to intracellular (green) localization of exosomes within B cells. Scale bars, 30 µm (left and middle panels), 7.5 µm (right panels). One representative experiment of three is shown.

Having found that DG75 exosomes bind with similar efficiency to human B cells, we next investigated whether exosomes are also internalized by the cells. Thus, we performed a kinetic study in which either no exosomes (−) or BJABex or LCL1ex harboring high levels of LMP1 were added to primary B cells for 24 or 48 h (Fig. 3C). To ensure maximal uptake but minimize the likelihood of detecting associated or unbound exosomes, B cells were washed extensively with PBS after 15 h. LMP1 was detected by immunoblot analysis in B cells incubated with LCL1ex at both time points. The two LMP1-specific bands have a molecular mass of 57–66 kDa and 50–55 kDa, corresponding to full-length and truncated LMP1 (19, 28). Yet to visualize internalization of exosomes, DG75 exosomes were labeled with the lipid dye PKH67 and incubated with primary B cells for 4 h at 37°C. CLSM analysis revealed the intra- and extracellular localization of DG75 exosomes in B cells (Fig. 3D). A stronger and more frequent intracellular staining of PKH67+-exosome-positive B cells was observed for DG75-LMP1ex (~20%) compared with DG75-COex (~11%) and DG75-EBVex (~11%) (Fig. 3D). In summary, these findings indicated that DG75 exosomes bound with similar efficiency to B cells in PBMCs and were internalized by B cells.

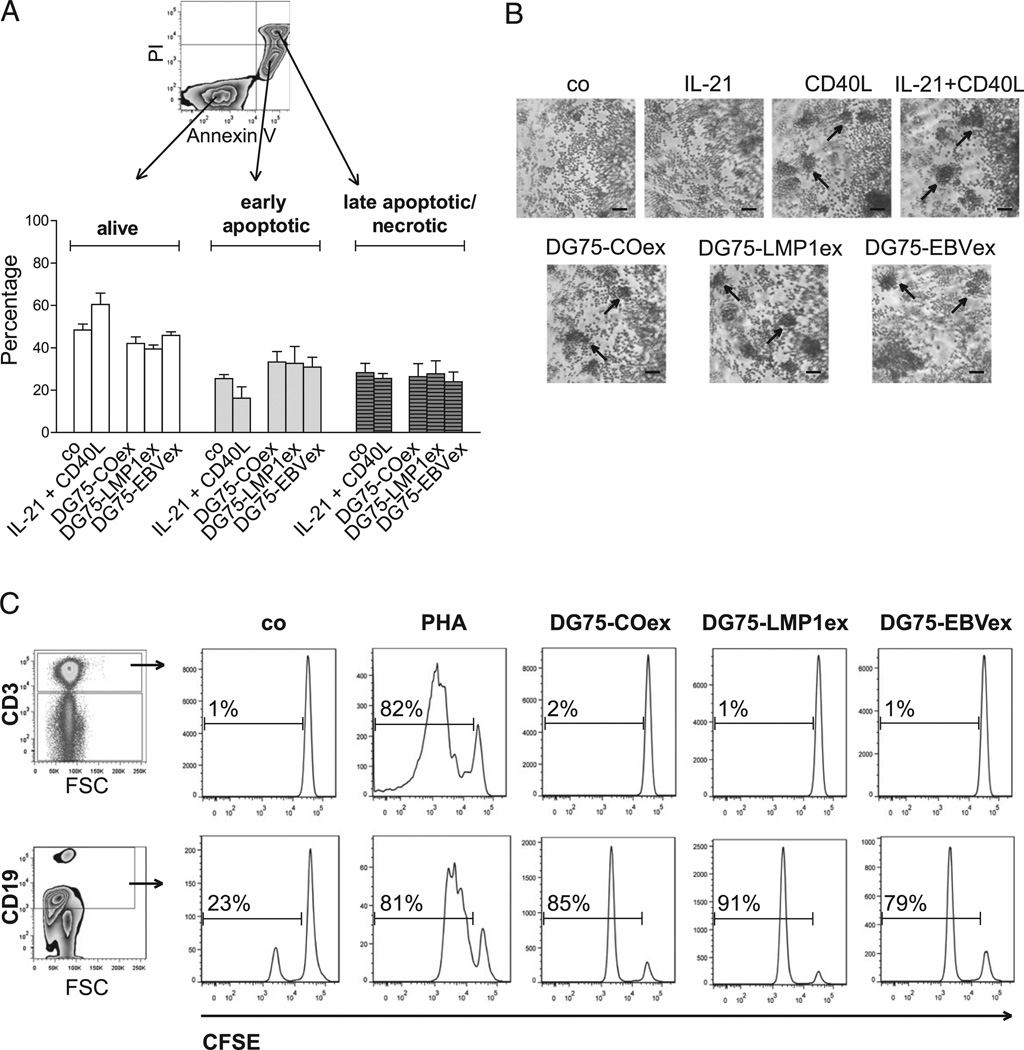

DG75 exosomes do not prevent early apoptosis, but they induce B cell proliferation in PBMCs

Exosomes were demonstrated to shuttle proteins and RNAs to recipient cells in various settings, thereby influencing the cellular response (29). Having found that human B cells internalize DG75 exosomes, we wondered whether exosomes might provide survival signals. Therefore, B cells were incubated for 24 h with DG75-COex, DG75-LMP1ex, or DG75-EBVex and subsequently stained for Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) to investigate signs of apoptosis (Fig. 4A). After 24 h, unstimulated (co) and IL-21 + CD40L–stimulated B cells already made up 53 and 41% of early apoptotic and late apoptotic/necrotic cells, respectively. No statistical difference in induction of apoptosis was observed when the addition of DG75 exosomes was compared with unstimulated B cells (early apoptotic, p = 0.305; late apoptotic/necrotic, p = 0.781; n = 4). Interestingly, we observed the formation of clumps in DG75 exosome–stimulated B cells in a similar manner as observed in CD40L- and IL-21 + CD40L–stimulated B cells (Fig. 4B). However, no difference was detected among the various DG75 exosomes. The observed clump formation prompted us to investigate in a first attempt whether DG75 exosomes have a functional impact and might induce the proliferation of lymphocytes. CFSE-labeled PBMCs were either left unstimulated (co) or stimulated with PHA or DG75 exosomes, and cell proliferation was assessed after 5 d by flow cytometry. The addition of DG75 exosomes to PBMCs did not induce proliferation of T cells, but it induced strong proliferation of B cells (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 4.

DG75 exosomes do not prevent apoptosis but induce B cell proliferation in PBMCs. Purified B cells (1.8 × 105 cells/200 µl) were either left unstimulated (co) or stimulated with IL-21 + CD40L or with 15 µg/well DG75-COex, DG75-LMP1ex, or DG75-EBVex. After 24 h, the induction of apoptosis was assessed by flow cytometry (A), and morphological changes were documented (B). (A) Representative contour plot showing differentiation between alive (Annexin V− and PI−), early apoptotic (Annexin V+, PI−), or late apoptotic/necrotic (Annexin V+ and PI+) B cells. Results are shown from four independent experiments (mean ± SEM). (B) Cultures of purified B cells were stimulated, as indicated, and visualized using a light microscope. Arrows indicate the formation of clumps. One representative experiment out of two is shown. Scale bars, 200 µm. (C) PBMCs were labeled with CFSE and either left unstimulated (co) or stimulated with PHA or DG75-COex, DG75-LMP1ex, or DG75-EBVex. After 5 d, proliferation of CD3+ T cells and CD19+ B cells was assessed by flow cytometry. One representative experiment of two is shown.

DG75 exosomes induce a dose-dependent proliferative response in B cells

The observedBcell–specific proliferation inPBMCs inducedbyDG75 exosomes prompted us to investigate whether DG75 exosomes also induce proliferation of isolated B cells. In particular, we wondered whether LMP1 transferred through DG75-LMP1ex might induce stronger proliferation in the recipient B cells than did DG75-COex and DG75-EBVex. Hence, B cells were labeled with CFSE, and proliferation was assessed by flow cytometry 5 d after stimulation with the different DG75 exosomes, alone or in combination with IL-21 (Fig. 5A). Synergistic activation ofBcellswith IL-21 + CD40L induced proliferation rates ranging from ~40–95%, depending on the blood donor. Because of this observed variability among the blood donors, all data were normalized to the proliferation rate of IL-21 + CD40L–stimulated B cells, which was set to 100% (Fig. 5B). CD40L stimulation alone induced lower proliferation rates (average, 33%) compared with the synergistic activation. In contrast, unstimulated (co) or IL-21–stimulated B cells did not proliferate (average, 2%). The addition of DG75 exosomes induced a dose-dependent proliferative response. Compared with unstimulated B cells, a significant increase in proliferation was observed when 25 µg of DG75-COex (12%) and DG75-LMP1ex (24%) were added, and a trend toward increased proliferation of DG75-LMP1ex compared with DG75-COex (p = 0.057) was noted. The addition of IL-21 to DG75 exosome stimulation did not increase the proliferation rates (Fig. 5B). Taken together, our data demonstrate that DG75 exosomes induce proliferation of human B cells in a concentration-dependent manner.

FIGURE 5.

DG75 exosomes induce a dose-dependent proliferative response in B cells. B cells (1.5 × 105 cells/200 µl) were labeled with CFSE and either left unstimulated (co) or stimulated with IL-21, CD40L, or IL-21 + CD40L or with 5 or 25 µg exosomes/well, with or without IL-21. After 5 d of culture, proliferation was assessed by flow cytometry. (A) Representative plots from one donor. The percentage of B cells for each quadrant is shown. (B) Combined results from four blood donors (mean ± SEM). Data are normalized to proliferation rates of IL-21 + CD40L–stimulated B cells (= 100%). *p ≤ 0.05, Mann–Whitney U test.

DG75-LMP1ex induces differentiation into a CD19+CD38highCD20low plasmablast-like B cell population

Proliferating B cells have two fates in a germinal center reaction: differentiation into memory B cells or Ab-secreting plasmablasts (30). Hence, we addressed whether the observed proliferation is accompanied by B cell differentiation. CFSE-labeled B cells were stained for CD19, CD20, and CD38 expression. Plasmablast differentiation is characterized by increased expression of CD38 and decreased expression of CD20 (Fig. 6A). Synergistic activation with IL-21 + CD40L for 5 d gave rise to a CD19+CD38highCD20low population with an average of 11% compared with an average of 6% observed in unstimulated B cells (Fig. 6B). Addition of 5 µg DG75 exosomes did not induce an increase in that population; however, the addition of 25 µg of DG75-LMP1ex induced a significant increase, with an average of 26% of the CD19+CD38highCD20low population compared with unstimulated B cells (Fig. 6B). In contrast, addition of 25 µg of DG75-COex and DG75-EBVex induced, on average, only 12% of the CD19+CD38highCD20low population. As already observed in the proliferation assay (Fig. 6B), the addition of IL-21 did not enhance the differentiation effects induced by the exosomes alone. These data suggest that DG75-LMP1ex induce differentiation into aCD19+CD38highCD20low plasmablast-like cell population.

FIGURE 6.

DG75-LMP1ex induces differentiation into a CD38highCD20low plasmablast-like B cell population. CFSE-labeled B cells (1.5 × 105 cells/200 µl) were either left unstimulated (co) or stimulated with IL-21, CD40L, or IL-21 + CD40L or with 5 or 25 µg DG75 exosomes/well, with or without IL-21. After 5 d of culture, B cells were stained for CD19, CD20, and CD38 and assessed by flow cytometry. (A) Representative plots from one donor are shown, and the percentage of CD38highCD20low B cells is indicated. (B) Combined results from four blood donors (mean ± SEM). *p ≤ 0.05, Mann–Whitney U test.

DG75 exosomes induce class-switch recombination in human IgD+ B cells

A key feature of activated B cells is that they undergo class-switch recombination (CSR) that diversifies the effector function of the secreted Ab. A hallmark of active CSR is upregulation of the enzyme AID, the formation of looped-out circular DNAs (circle transcripts), and germline transcription (31). Intrinsic LMP1 expression was shown to induce CSR from constant µ (Cµ) to multiple Cγ, Cα, and Cε genes in a NF-κB–dependent manner (27). For this reason, we investigated whether B cells stimulated with DG75 exosomes showed signs of active CSR. First, we measured the upregulation of AID (AICDA) transcripts by quantitative real-time PCR in IgD+-selected B cells exposed to DG75 exosomes, alone or in combination with IL-21 (Fig. 7A). B cells stimulated with DG75 exosomes plus IL-21 upregulated AICDA transcripts comparable to IL-21 + CD40L–stimulated B cells. Next, we addressed whether DG75 exosomes induced the formation of circular Iγ1/2-Cμ transcripts, as well as Iγ1/2-Cγ1 germline transcription. Of note, the formation of looped-out circular DNA detected by circle transcript formation precedes germline transcription (31). Amplified Iγ1/2-Cμ circular transcripts were detected by Southern blot analysis in primary B cells when stimulated with IL-21, CD40L, IL-21 + CD40L and when exposed to DG75-COex, DG75-LMP1ex alone, and DG75-EBVex + IL-21 (Fig. 7B). Iγ1/2-Cγ1 germline transcription was observed in CD40L, DG75-LMP1ex, DG75-EBVex, and IL-21 + DG75-COex or DG75-LMP1ex B cells of another donor (Fig. 7C). Altogether, these data indicate that DG75 exosome stimulation induces circle transcript formation and germline transcription in primary human B cells.

FIGURE 7.

DG75 exosomes induce CSR in human IgD+ B cells. IgD+ B cells were either left unstimulated (co) or stimulated with IL-21, CD40L, or IL-21 + CD40L or with DG75 exosomes, with or without IL-21, for 3 d. (A) Quantitative real-time PCR of AICDA transcripts relative to unstimulated (co) B cells. AICDA was normalized to EF-1α and GAPDH mRNA levels. Data from one donor of two is shown. Southern blot analysis of (B) circle transcripts for Iμ-Cμ and Iγ1/2-Cμ and (C) for Iμ-Cμ and Iγ1/2-Cγ1 germline transcripts. Data in (B) and (C) are from two donors.

Discussion

In this study, we provide evidence that B cell–derived exosomes shuttle functional information to human B cells and, thereby, influence B cell biology. The DG75 Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line (DG75-CO), LMP1-transfected cell line (DG75-LMP1), or EBVinfected cell line (DG75-EBV) were used as constitutive sources for B cell–derived exosomes, with the hypothesis that they might mimic exosomes released during EBV infection or EBV-associated diseases. Our data demonstrate that DG75 exosomes efficiently bind to B cells within PBMCs, are internalized by B cells, and induce proliferation and CSR. Additionally, we observed that DG75-LMP1 exosomes are able to induce the differentiation of B cells into a plasmablast-like phenotype.

LCLs are characterized by high expression of LMP1 that facilitates the outgrowth and survival of a particular clone within the EBV-infected polyclonal B cell culture. Constitutive LMP1 signaling is limited through association of endogenous LMP1 with endosomal tetraspanin CD63 and subsequent secretion via exosomes (18). Our results showed that primary EBV-infected B cells also released exosomes harboring LMP1, but expression levels were much lower compared with LCL-derived exosomes (Fig. 1A). Instead, the Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line stably transfected with LMP1 (DG75-LMP1) was a suitable source to obtain human exosomes that harbored LMP1 at physiological concentrations and, thus, potentially mimic exosomes that are released during primary EBV infection (Fig. 1B).

Primary human B cells stimulated with IL-4 plus anti-CD40 secrete exosomes that reflect the activation state of the B cells (32). Consistent with these findings, DG75 exosomes reflected the phenotype of their corresponding B cell line (Fig. 2B). Ectopic LMP1 expression in EBV− Burkitt’s lymphoma cell lines was shown to increase MHC class I and II Ag expression (33, 34). In line with this, DG75-LMP1ex had significantly higher levels of HLA-ABC and HLA-DR than did DG75-COex (Fig. 2B). In general, it has to be stressed that all three DG75 exosomes had a phenotypic profile that distinguished them, and these differences are likely to influence biological effects. For instance, DG75-LMP1ex and DG75-EBVex had significantly higher levels of HLA-ABC molecules compared with DG75-COex, and it is tempting to speculate that they contain EBV-specific peptides that could be presented on the surface of DCs or B cells after their uptake. Potentially, these exosomes could be an “additional source” of viral peptides, which increase the frequency of EBV-specific CTLs. In contrast, increased expression of HLA-DR molecules on DG75-LMP1ex compared with DG75-COex and DG75-EBVex might be an additional Ag source used by DCs to license CD4+ Th cells that, in turn, can activate B cells, thereby inducing Ab responses. Also, LMP1 was detected only in DG75-LMP1ex; the diverse effects seen in this study between the different DG75 exosomes are clearly not only dependent on the presence of LMP1 (Fig. 1B). Of note, the low or undetectable LMP1 levels in DG75-EBV cells and DG75-EBVex, respectively, are in agreement with a previous study (24).

A large body of evidence indicates that exosomes play a major role in intercellular communication and, thereby, influence the outcome of an immune response (1, 35). To contribute to intercellular communication, exosomes have to interact with and deliver their content to the recipient cell. In a previous study, we observed that DC- and breast milk–derived exosomes had a different binding pattern within PBMC cultures compared with exosomes from a gp350-expressing LCL (LCL1) (25). Our data demonstrate that the different DG75 exosomes bound with similar efficiency to B cells and monocytes within PBMC cultures (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, the detection of LMP1 shuttled through LCL1ex in B cell lysates indicated exosome binding and suggested their uptake (Fig. 3C). Confocal microscopy analysis demonstrated internalization of DG75 exosomes by B cells (Fig. 3D). Recently, fusion of the exosomal membrane with the plasma membrane was demonstrated as a mechanism by which functional miRNA shuttled by DC-derived exosomes is delivered to the acceptor DC (36). Pegtel et al. (29) demonstrated the functional delivery of mature EBV-encoded microRNAs via exosomes released from EBV-infected B cells to monocyte-derived DCs. However, it still has to be elucidated which uptake mechanism, direct fusion or endocytosis, allows B cell–derived exosomes to deliver their content into the cytoplasm of the recipient B cell.

Apoptosis plays a critical role in B cell development and homeostasis, and the T cell–derived cytokine IL-21 was shown in vitro to induce apoptosis of resting and activated primary murine B cells (37). Consistent with that, unstimulated and IL-21 + anti-CD40–stimulated primary human B cells also showed signs of apoptosis and necrosis already at 24 h, and the addition of DG75 exosomes did not protect resting B cells from apoptosis (Fig. 4A). Ectopic LMP1 expression in a B cell line and EBV infection of IgD+ B cells in vitro provide B cell survival signals through upregulation of autocrine BAFF and a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL) expression (27, 38). However, the concentration of LMP1 in B cells after delivery through DG75-LMP1ex is much lower compared with ectopically expressed LMP1 used in the above-described study (27). Future studies will investigate whether exosomes carrying high amounts of LMP1 induce autocrine BAFF and APRIL expression that provide survival and proliferation signals to B cells. This might be of particular interest in providing a link between EBV exosomes and SLE, in which increased BAFF expression rescues self-reactive B cells from peripheral deletion (39).

The addition of DG75 exosomes to PBMC cultures induced proliferation in B cells, whereas no proliferation was seen for T cells (Fig. 4C). It has to be stressed that the absence of T cell proliferation might be due to the very low binding efficiency of DG75 exosomes to T cells (<3%; data not shown). A dose-dependent proliferation was observed when isolated B cells were exposed to DG75 exosomes, with a trend toward increased proliferation for DG75-LMP1ex (Fig. 5B). We would like to point out that these data were generated in two laboratories with consistent results (Sweden and Spain). Compared with isolated B cells, B cell proliferation within PBMCs was much stronger, indicating that the presence of APCs, CD4+ T cell help, and soluble factors released by these cells is important to boost B cell proliferation (Figs. 4C, 5B). The proliferative capacity is supported by the observation that DG75 exosomes are taken up by B cells, as well as the more pronounced intracellular staining of DG75-LMP1ex by CLSM (Fig. 3D). Moreover, it suggests that DG75-LMP1ex delivered functional LMP1 that can signal through TNFR-associated factor adaptor molecules to govern proliferation in recipient B cells. Our data are in line with the finding that EBV-mediated B cell proliferation is dependent upon LMP1, as well as the observation of increased development of lymphoma in LMP1-transgenic mice (40, 41). However, it remains to be elucidated which proliferation-inducing factor is delivered by DG75-COex and DG75-EBVex. The expression of EBNA2 and LMP1 is essential for EBV transformation of B cells in vitro (42, 43). Immunoblot analysis of cell lysates from DG75 cells revealed no expression of EBNA2 (Supplemental Fig. 1A). This is in accordance with previous reports, namely that the original cell line DG75-CO is EBV− and that EBV infection did not induce EBNA2 expression (22, 24). Therefore, we can rule out that EBNA2 is delivered via DG75 exosomes to B cells.

In contrast, the question arises which B cell population proliferated after exposure to high doses of DG75 exosomes. Negatively isolated peripheral B cells were used as recipient cells, which consist of naive (IgD+CD27−), marginal zone (IgD+CD27+), and memory (IgD−CD27+) B cells (44, 45). Preliminary data on isolated IgD+ B cells also revealed a dose-dependent proliferation of DG75 exosomes, with increased proliferation for DG75-LMP1ex (C. Gutzeit, unpublished observations). Thus, it is likely that the responding cell population is either naive and/or circulating marginal zone B cells. Strikingly, the proliferating B cells exposed to DG75-LMP1ex differentiated into a CD19+CD38highCD20low plasmablast-like population (Fig. 6). Human IgD+CD27+ marginal zone B cells were shown to have increased capacity to differentiate and to secrete all IgG subclasses compared with naive B cells (46). Therefore, future studies will focus on the ability of exosomes to stimulate this particular B cell subset.

To mount protective immune responses, B cells diversify Igencoding genes through CSR, which is mandatory for the maturation of the Ab response and crucially requires AID (47). Stimulation of IgD+ B cells with DG75 exosomes + IL-21 induced the upregulation of AID transcripts (Fig. 6A). Recently, it was demonstrated that BCR signaling needs to synergize with TLR signaling to induce AID and T cell–independent CSR (48, 49). Our data suggest that DG75 exosomes might provide a yet unknown primary CSR-inducing signal (e.g., BCR crosslinking), which then synergizes with cytokine signaling to induce AID. Additionally, hallmarks of active CSR are the formation of circular transcripts and germline transcription (31). Germline transcripts play a central role in CSR by directing AID to a specific S region within the IgH locus, and IL-21 was shown to be a switch factor for Cγ1 and Cγ3 transcripts in human B cells (50, 51). Stimulation of IgD+ B cells with DG75 exosomes induced the formation of Iγ1/2-Cμ circle transcripts, as well as Iγ1/2-Cγ1 germline transcription (Fig. 7A, 7B). Ectopic LMP1 expression in a BJAB cell line stably transfected with a tetracycline-inducible LMP1 expression vector was shown to induce Iγ1/2-Cγ1 germline transcripts (27). However, it remains to be investigated further why the synergistic stimulation of IgD+ B cells with DG75 exosomes plus IL-21 did not increase circle transcript formation and germline transcription.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates the B cell–stimulatory capacity of exosomes released by EBV-infected B cells. So far, various studies have only elucidated an immune-suppressive effect of these exosomes on recipient cells, such as human T cells and DCs (15, 29). However, B cells are equipped with all mandatory adaptor molecules to provide signaling for viral proteins, such as LMP1, a mimic of the B cell–activating receptor CD40 (16). Thus, we propose that B cell–derived exosomes released from EBVinfected B cells are able to deliver their content to B cells and, thereby, influence B cell biology. Therefore, clinical features observed in patients with EBV-associated diseases, such as lymphoproliferative disorders or autoimmune diseases, might be intensified by the presence and action of these exosomes. Furthermore, they might influence B cell development in healthy EBV carriers with implications, for example, for allergy or autoimmune disease development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mikael Karlsson, Lisa Westerberg, and John Andersson (Department of Medicine Solna, Karolinska Institutet and Karolinska University Hospital) for fruitful discussions. We are grateful for the excellent technical support of Linda Cassis (Institut Municipal d‘Investigatió Mèdica, Barcelona, Spain).

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council, the Center for Allergy Research Karolinska Institutet, the Hesselman Foundation through Junior Faculty, Karolinska Institutet, and the Swedish Cancer and Allergy Fund. N.N. is a recipient of a Cancer Research Fellowship from the Cancer Research Institute (New York)/Concern Foundation (Los Angeles).

Abbreviations used in this article

- AID

activation-induced cytidine deaminase

- APRIL

a proliferation-inducing ligand

- CLSM

confocal laser scanning microscopy

- co

unstimulated control

- CSR

class-switch recombination

- DC

dendritic cell

- FSC

forward scatter

- FSC-A

FSC area

- FSC-H

FSC height

- Iγ1-Cμ

intronic γ1 exon–C region of the H chain μ

- LCL

lymphoblastoid cell line

- LMP1

latent membrane protein 1

- PI

propidium iodide

- SSC

side scatter

- SSC-A

SSC area

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bobrie A, Colombo M, Raposo G, Théry C. Exosome secretion: molecular mechanisms and roles in immune responses. Traffic. 2011;12:1659–1668. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathivanan S, Ji H, Simpson RJ. Exosomes: extracellular organelles important in intercellular communication. J. Proteomics. 2010;73:1907–1920. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Théry C, Ostrowski M, Segura E. Membrane vesicles as conveyors of immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009;9:581–593. doi: 10.1038/nri2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLellan AD. Exosome release by primary B cells. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2009;29:203–217. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v29.i3.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaput N, Théry C. Exosomes: immune properties and potential clinical implementations. Semin. Immunopathol. 2011;33:419–440. doi: 10.1007/s00281-010-0233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor DD, Akyol S, Gercel-Taylor C. Pregnancy-associated exosomes and their modulation of T cell signaling. J. Immunol. 2006;176:1534–1542. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Admyre C, Johansson SM, Qazi KR, Filén JJ, Lahesmaa R, Norman M, Neve EP, Scheynius A, Gabrielsson S. Exosomes with immune modulatory features are present in human breast milk. J. Immunol. 2007;179:1969–1978. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Théry C, Duban L, Segura E, Véron P, Lantz O, Amigorena S. Indirect activation of naïve CD4+ T cells by dendritic cell-derived exosomes. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:1156–1162. doi: 10.1038/ni854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein G, Klein E, Kashuba E. Interaction of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) with human B-lymphocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010;396:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaganti S, Ma CS, Bell AI, Croom-Carter D, Hislop AD, Tangye SG, Rickinson AB. Epstein-Barr virus persistence in the absence of conventional memory B cells: IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells harbor the virus in X-linked lymphoproliferative disease patients. Blood. 2008;112:672–679. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaganti S, Heath EM, Bergler W, Kuo M, Buettner M, Niedobitek G, Rickinson AB, Bell AI. Epstein-Barr virus colonization of tonsillar and peripheral blood B-cell subsets in primary infection and persistence. Blood. 2009;113:6372–6381. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-175828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Küppers R. B cells under influence: transformation of B cells by Epstein-Barr virus. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2003;3:801–812. doi: 10.1038/nri1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niller HH, Wolf H, Minarovits J. Regulation and dysregulation of Epstein-Barr virus latency: implications for the development of autoimmune diseases. Autoimmunity. 2008;41:298–328. doi: 10.1080/08916930802024772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raposo G, Nijman HW, Stoorvogel W, Liejendekker R, Harding CV, Melief CJ, Geuze HJ. B lymphocytes secrete antigen-presenting vesicles. J. Exp. Med. 1996;183:1161–1172. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flanagan J, Middeldorp J, Sculley T. Localization of the Epstein-Barr virus protein LMP 1 to exosomes. J. Gen. Virol. 2003;84:1871–1879. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18944-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Middeldorp JM, Pegtel DM. Multiple roles of LMP1 in Epstein-Barr virus induced immune escape. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2008;18:388–396. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mosialos G, Birkenbach M, Yalamanchili R, VanArsdale T, Ware C, Kieff E. The Epstein-Barr virus transforming protein LMP1 engages signaling proteins for the tumor necrosis factor receptor family. Cell. 1995;80:389–399. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90489-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verweij FJ, van Eijndhoven MA, Hopmans ES, Vendrig T, Wurdinger T, Cahir-McFarland E, Kieff E, Geerts D, van der Kant R, Neefjes J, et al. LMP1 association with CD63 in endosomes and secretion via exosomes limits constitutive NF-κB activation. EMBO J. 2011;30:2115–2129. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dukers DF, Meij P, Vervoort MB, Vos W, Scheper RJ, Meijer CJ, Bloemena E, Middeldorp JM. Direct immunosuppressive effects of EBV-encoded latent membrane protein 1. J. Immunol. 2000;165:663–670. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keryer-Bibens C, Pioche-Durieu C, Villemant C, Souquère S, Nishi N, Hirashima M, Middeldorp J, Busson P. Exosomes released by EBV-infected nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells convey the viral latent membrane protein 1 and the immunomodulatory protein galectin 9. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:283. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qazi KR, Gehrmann U, Domange Jordö E, Karlsson MC, Gabrielsson S. Antigen-loaded exosomes alone induce Th1-type memory through a B-cell-dependent mechanism. Blood. 2009;113:2673–2683. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-153536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ben-Bassat H, Goldblum N, Mitrani S, Goldblum T, Yoffey JM, Cohen MM, Bentwich Z, Ramot B, Klein E, Klein G. Establishment in continuous culture of a new type of lymphocyte from a “Burkitt like” malignant lymphoma (line D.G.-75) Int. J. Cancer. 1977;19:27–33. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910190105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cuomo L, Trivedi P, Wang F, Winberg G, Klein G, Masucci MG. Expression of the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-encoded membrane antigen (LMP) increases the stimulatory capacity of EBV-negative B lymphoma lines in allogeneic mixed lymphocyte cultures. Eur. J. Immunol. 1990;20:2293–2299. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830201019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maeda A, Kiss C, Chen F, Ehlin-Henriksson B, Nagy N, Szekely L, Takada K, Klein E, Klein G. EBNA promoter usage in EBV-negative Burkitt lymphoma cell lines converted with a neomycin-resistant EBV strain. Int. J. Cancer. 2001;93:714–719. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vallhov H, Gutzeit C, Johansson SM, Nagy N, Paul M, Li Q, Friend S, George TC, Klein E, Scheynius A, Gabrielsson S. Exosomes containing glycoprotein 350 released by EBV-transformed B cells selectively target B cells through CD21 and block EBV infection in vitro. J. Immunol. 2011;186:73–82. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He B, Santamaria R, Xu W, Cols M, Chen K, Puga I, Shan M, Xiong H, Bussel JB, Chiu A, et al. The transmembrane activator TACI triggers immunoglobulin class switching by activating B cells through the adaptor MyD88. Nat. Immunol. 2010;11:836–845. doi: 10.1038/ni.1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He B, Raab-Traub N, Casali P, Cerutti A. EBV-encoded latent membrane protein 1 cooperates with BAFF/BLyS and APRIL to induce T cell-independent Ig heavy chain class switching. J. Immunol. 2003;171:5215–5224. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang X, He Z, Xin B, Cao L. LMP1 of Epstein-Barr virus suppresses cellular senescence associated with the inhibition of p16INK4a expression. Oncogene. 2000;19:2002–2013. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pegtel DM, Cosmopoulos K, Thorley-Lawson DA, van Eijndhoven MA, Hopmans ES, Lindenberg JL, de Gruijl TD, Würdinger T, Middeldorp JM. Functional delivery of viral miRNAs via exosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:6328–6333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914843107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McHeyzer-Williams M, Okitsu S, Wang N, McHeyzer-Williams L. Molecular programming of B cell memory. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012;12:24–34. doi: 10.1038/nri3128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kinoshita K, Harigai M, Fagarasan S, Muramatsu M, Honjo T. A hallmark of active class switch recombination: transcripts directed by I promoters on looped-out circular DNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:12620–12623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221454398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saunderson SC, Schuberth PC, Dunn AC, Miller L, Hock BD, MacKay PA, Koch N, Jack RW, McLellan AD. Induction of exosome release in primary B cells stimulated via CD40 and the IL-4 receptor. J. Immunol. 2008;180:8146–8152. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.12.8146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rowe M, Khanna R, Jacob CA, Argaet V, Kelly A, Powis S, Belich M, Croom-Carter D, Lee S, Burrows SR, et al. Restoration of endogenous antigen processing in Burkitt’s lymphoma cells by Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein-1: coordinate up-regulation of peptide transporters and HLA-class I antigen expression. Eur. J. Immunol. 1995;25:1374–1384. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Q, Brooks L, Busson P, Wang F, Charron D, Kieff E, Rickinson AB, Tursz T. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) latent membrane protein 1 increases HLA class II expression in an EBV-negative B cell line. Eur. J. Immunol. 1994;24:1467–1470. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, micro-vesicles, and friends. J. Cell Biol. 2013;200:373–383. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Montecalvo A, Larregina AT, Shufesky WJ, Stolz DB, Sullivan ML, Karlsson JM, Baty CJ, Gibson GA, Erdos G, Wang Z, et al. Mechanism of transfer of functional microRNAs between mouse dendritic cells via exosomes. Blood. 2012;119:756–766. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-338004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mehta DS, Wurster AL, Whitters MJ, Young DA, Collins M, Grusby MJ. IL-21 induces the apoptosis of resting and activated primary B cells. J. Immunol. 2003;170:4111–4118. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.4111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schweighoffer E, Vanes L, Nys J, Cantrell D, McCleary S, Smithers N, Tybulewicz VL. The BAFF receptor transduces survival signals by co-opting the B cell receptor signaling pathway. Immunity. 2013;38:475–488. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thien M, Phan TG, Gardam S, Amesbury M, Basten A, Mackay F, Brink R. Excess BAFF rescues self-reactive B cells from peripheral deletion and allows them to enter forbidden follicular and marginal zone niches. Immunity. 2004;20:785–798. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thornburg NJ, Kulwichit W, Edwards RH, Shair KH, Bendt KM, Raab-Traub N. LMP1 signaling and activation of NF-kappaB in LMP1 transgenic mice. Oncogene. 2006;25:288–297. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kilger E, Kieser A, Baumann M, Hammerschmidt W. Epstein-Barr virus-mediated B-cell proliferation is dependent upon latent membrane protein 1, which simulates an activated CD40 receptor. EMBO J. 1998;17:1700–1709. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hammerschmidt W, Sugden B. Genetic analysis of immortalizing functions of Epstein-Barr virus in human B lymphocytes. Nature. 1989;340:393–397. doi: 10.1038/340393a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaye KM, Izumi KM, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 is essential for B-lymphocyte growth transformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:9150–9154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.9150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klein U, Rajewsky K, Küppers R. Human immunoglobulin (Ig)M+IgD+ peripheral blood B cells expressing the CD27 cell surface antigen carry somatically mutated variable region genes: CD27 as a general marker for somatically mutated (memory) B cells. J. Exp. Med. 1998;188:1679–1689. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.9.1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weller S, Braun MC, Tan BK, Rosenwald A, Cordier C, Conley ME, Plebani A, Kumararatne DS, Bonnet D, Tournilhac O, et al. Human blood IgM “memory” B cells are circulating splenic marginal zone B cells harboring a prediversified immunoglobulin repertoire. Blood. 2004;104:3647–3654. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Werner-Favre C, Bovia F, Schneider P, Holler N, Barnet M, Kindler V, Tschopp J, Zubler RH. IgG subclass switch capacity is low in switched and in IgM-only, but high in IgD+IgM+, post-germinal center (CD27+) human B cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2001;31:243–249. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200101)31:1<243::AID-IMMU243>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu Z, Zan H, Pone EJ, Mai T, Casali P. Immunoglobulin class-switch DNA recombination: induction, targeting and beyond. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012;12:517–531. doi: 10.1038/nri3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pone EJ, Zhang J, Mai T, White CA, Li G, Sakakura JK, Patel PJ, Al-Qahtani A, Zan H, Xu Z, Casali P. BCR-signalling synergizes with TLR-signalling for induction of AID and immunoglobulin class-switching through the non-canonical NF-κB pathway. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:767. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rawlings DJ, Schwartz MA, Jackson SW, Meyer-Bahlburg A. Integration of B cell responses through Toll-like receptors and antigen receptors. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012;12:282–294. doi: 10.1038/nri3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stavnezer J, Guikema JE, Schrader CE. Mechanism and regulation of class switch recombination. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2008;26:261–292. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pène J, Gauchat JF, Lécart S, Drouet E, Guglielmi P, Boulay V, Delwail A, Foster D, Lecron JC, Yssel H. Cutting edge: IL-21 is a switch factor for the production of IgG1 and IgG3 by human B cells. J. Immunol. 2004;172:5154–5157. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.