Abstract

Background

The screening colonoscopy process requires a considerable amount of time and some discomfort for patients.

Objective

We sought to use willingness-to-pay (WTP) to value the time required and the discomfort associated with screening colonoscopy. In addition, we aimed to explore some of the differences between and potential uses of the WTP and the human capital methods.

Methods

Subjects completed a diary recording time and a questionnaire including WTP questions to value the time and discomfort associated with colonoscopy. We also valued the elapsed time reported in the diaries (but not the discomfort) using the human capital method.

Results

110 subjects completed the study. Mean WTP to avoid the time and discomfort was $263. Human capital values for elapsed time were greater. Linear regressions showed that WTP was influenced most by the difficulty of the preparation, which added $147 to WTP (p=0.03).

Conclusions

WTP values to avoid the time and discomfort associated with the screening colonoscopy process were substantially lower than most of the human capital values for elapsed time alone. The human capital method may overestimate the value of time in situations that involve an irregular, episodic series of time intervals, such as preparation for or recovery after colonoscopy.

Keywords: Willingness-to-pay, contingent valuation method, health economics methods, colorectal cancer

1. INTRODUCTION

Patients undergoing screening colonoscopy invest a substantial amount of time preparing for, having, and recovering from the procedure. Valuing this time is important for economic analyses and for better understanding how patients view time spent in healthcare screening and other preventive endeavors including whether time may be a barrier to adherence (Jonas et al., 2007). A number of studies have focused on measuring or valuing patient time requirements for healthcare services (Attard et al., 2005, Bech and Gyrd-Hansen, 2000, Borisova and Goodman, 2003, Borisova and Goodman, 2004, Bryan et al., 1995, Cantor et al., 2006, Cromwell et al., 1997, Frew et al., 1999, Jonas et al., 2007, Lawrence et al., 2001, Robbins et al., 2002, Safford et al., 2005, Salome et al., 2003, Sculpher et al., 2000, Secker-Walker et al., 1999, Shireman et al., 2001, Tilford, 1993, Yabroff et al., 2005).

The human capital method and willingness-to-pay (WTP) are two economic techniques that can be used to value time. Some studies have attempted to value patient time using the human capital method, basing the value on patients’ salaries or on population wage averages (Attard et al., 2005, Bech and Gyrd-Hansen, 2000, Bryan et al., 1995, Cantor et al., 2006, Cromwell et al., 1997, Frew et al., 1999, Lawrence et al., 2001, Robbins et al., 2002, Salome et al., 2003, Sculpher et al., 2000, Shireman et al., 2001, Yabroff et al., 2005). Frew and colleagues measured and valued the time and travel costs incurred in screening with flexible sigmoidoscopy in the UK, finding a mean time of 130 minutes and a mean total cost (time and travel) of 22 British pounds (about $41) (Frew et al., 1999). We have previously reported the amount of time patients invest in the screening colonoscopy process and the value of this time using the human capital method (Jonas et al., 2007, Jonas et al., 2008).

Willingness-to-pay (WTP) has not been widely used to value patient time specifically, but has been used extensively to value health services or health states (Bergmo and Wangberg, 2007, Boonen et al., 2005, Byrne et al., 2005, Diez, 1998, Fautrel et al., 2007, Frew et al., 2001, Greenberg et al., 2004, Gueylard Chenevier and LeLorier, 2005, He et al., 2007, Jimoh et al., 2007, Johannesson et al., 1993, Johannesson et al., 1991, Johannesson et al., 1997, Narbro and Sjostrom, 2000, Oscarson et al., 2007, Pinto-Prades et al., 2008, Sadri et al., 2005, Slothuus et al., 2000, Tang et al., 2007, Unutzer et al., 2003, Wagner et al., 2000, Walsh and Bartfield, 2006, Whynes et al., 2003, Yasunaga et al., 2006a, Yasunaga et al., 2006b, Yasunaga et al., 2006c, Yasunaga et al., 2007, Zarkin et al., 2000). Whynes and colleagues used WTP to assess the value of colon cancer screening with fecal occult blood testing and flexible sigmoidoscopy (Frew et al., 2001, Whynes et al., 2003). To our knowledge, only Borisova (Borisova and Goodman, 2003, Borisova and Goodman, 2004) and Tilford (Tilford, 1993) have used WTP methods specifically for the purpose of valuing patient time (rather than as a more comprehensive outcome measure). We did not identify any previous studies reporting WTP as a measure of the value of patient time, or patient time and discomfort, for screening colonoscopy.

The time patients spend preparing for a colonoscopy is an irregular series of trips to the bathroom with intermittent periods of normalcy and sleep. Recovery may be comprised of intermittent periods of normalcy also. In addition, some of these irregular periods may be partially, but not entirely, devoted to the preparation or recovery process. For example, patients may be able to multitask during the preparation by reading while they are in the bathroom. In such situations, measuring the entire preparation or recovery period, and valuing it by the wage as the human capital method does, may overestimate both the amount of time spent and its value to the patient. The WTP method allows subjects to value only the time actually devoted to the process. Moreover, in providing a WTP the individual need not value all time equally. Finally, WTP allows the value of time and the associated utility/disutility (e.g. discomfort associated with the preparation for colonoscopy) to be determined using one measure, rather than separate measures. Thus, researchers and analysts can obtain information about the value of both time and discomfort more easily, with one survey/questionnaire, rather than investing more resources to measure both time (by observation, recall, or with time diaries) and discomfort (with questionnaires or utility measures).

The purpose of this manuscript is to describe the use of WTP to value the time required of patients for screening colonoscopy and the discomfort associated with the procedure. In addition, we aimed to explore some of the differences between, and potential uses of, the WTP and the human capital methods. Our WTP questions incorporated the value of patient time and discomfort whereas the human capital method valued only time.

2. METHODS

2.1 Overview

We asked participants to complete a diary recording time requirements for the screening colonoscopy process, including time spent in preparation, travel, waiting, colonoscopy, and recovery, and to complete a questionnaire after the screening process was complete. The questionnaire included willingness-to-pay questions which asked patients to place a value on both the time and discomfort involved in the colonoscopy process. In addition, we valued the time reported in the time diaries (but not the discomfort) using the human capital method. We have reported elsewhere our results on the amounts of time required for screening and the value of patient time as estimated by the human capital method, as well as the impact of including the value of patient time in cost-effectiveness analyses (Jonas et al., 2007, Jonas et al., 2008).

2.2 Recruitment of Subjects

We recruited patients from an off-campus university endoscopy center between October 2005 and June 2006. Eligibility criteria included patients 50–85 years old who were English speaking, able to complete the diary and questionnaire (with or without assistance), without a history of colon cancer, and having a colonoscopy for screening or surveillance of polyps. We excluded patients having colonoscopies for other reasons, such as evaluation of anemia, bloody stools, or any other symptoms.

Patients who completed the diary and questionnaire received a $25 gift card in appreciation of their participation. The study was approved by the University of North Carolina’s Office of Human Research Ethics Biomedical IRB.

2.3 Measures

We collected data using a patient time diary (Appendix 1) and a self-administered questionnaire (Appendix 2) that were to be completed within 1 week after the colonoscopy. The questionnaire included inquiries about the following: the colonoscopy process, including the overall test experience, preparation, travel, recovery, and activities/work missed; any subjective complications (such as bleeding, abdominal pain or dizziness) occurring after the procedure; basic demographic information, including income; health assessment, including diagnoses of specific medical conditions and self-rated overall health; their ability to perform activities of daily living. The details of the questionnaire, diary, and time measures are presented elsewhere (Jonas et al., 2007, Jonas et al., 2008).

2.3.1 Time Measures

The data permitted us to define various time intervals (Jonas et al., 2007) including: total time, from changing one’s diet in preparation for the procedure until feeling completely back to normal after the procedure, prep to routine time, from taking the preparation medication (polyethylene glycol with electrolytes solution) until returning to routine activities; occupied time, from taking the preparation medication until arriving at home (or other destination) after the procedure; and dedicated time, from leaving home to go to the endoscopy center until arriving at home (or other destination) after the procedure.

2.3.2 Willingness-to-pay

For WTP, the goal is to determine the maximum amount one is willing to pay either for a benefit or to avoid something that is disliked. Our WTP questions included the time and discomfort associated with the colonoscopy process.

We used both open-ended and payment-scale WTP questions because we wanted to gain experience with both types of questions to inform future studies we plan to conduct using WTP. The wording of both questions was identical:

“Imagine there was a new method of screening that had the same benefits for detecting and preventing colon cancer as colonoscopy and the same risk of complications as colonoscopy. It would not require any preparation or cause discomfort, and it would not involve a recovery period.

Assuming that you have no out of pocket expenses for colonoscopy, what is the most you would be willing to pay out of pocket to be able to use such a method of screening rather than go through the colonoscopy?”

For the open-ended version, respondents were asked to fill in the blank. For the payment-scale version they were offered 6 choices: less than $50, $50 to $99, $100 to $249, $250 to $499, $500 to $999, and $1000 or more.

Prior to our study, we developed our WTP questions using previous studies (Frew et al., 2001, Frew et al., 2003, Safford et al., 2005, Whynes et al., 2003) and the expertise of our team. We attempted to create simply worded questions to mitigate issues of literacy. We pre-tested our draft questions with a sample of 20 patients at the study site. The study research assistant (RA) asked patients to read and complete the questionnaires, explaining out loud how they would interpret and answer the questions. We then made changes based on this feedback.

To gain additional information about how study respondents interpreted and responded to our questionnaires, we convened two focus groups of study participants (total n=13) after data collection was otherwise complete. Participants were given new copies of the questionnaire. The WTP questions were read aloud and they were asked to describe in their own words what the questions were asking. They were also asked what factors influenced their responses the most. Results were recorded and transcribed.

2.3.3 Human Capital Method

The human capital method, recommended by the Panel on Cost-effectiveness in Health and Medicine (Gold et al., 1996), is based on the following economic reasoning: if a person can choose how many hours to work for pay, she will choose to work until the gain from the last hour (the wage) equals the value she places on using that hour for unpaid activities (Phelps, 2003). Thus, as an approximation, the wage rate equals the value of the person’s time at the margin, i.e., for small changes in activities, and time can be valued at the wage rate. If a person chooses not to work, it indicates that she values unpaid activities more highly than the market wage she could command and the wage sets a lower bound on the value of time. Since determining the appropriate value can be difficult (Phelps, 2003), we used two alternative wages to value time by the human capital method: (1) we used $18.62 per hour, the 2005 national average wage from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS); (2) we repeated the calculations using each patient’s personal income, reported on the questionnaire, to approximate individual hourly income. For policy purposes, it is reasonable to value time at the average wage for all persons, because it represents a population perspective (Russell et al., 1996). However, individuals may value their time more or less highly than the average wage. In addition, values of time based on individuals’ hourly incomes may be more appropriate for comparison with WTP, since both may be dependent on personal circumstances rather than population averages.

An important limitation of the human capital method is that analysts, clinicians, and patients may disagree about which time interval to value. The time involved may not be continuously devoted to one activity, and thus not the same as the elapsed time measured by the time diary. The time spent during the colonoscopy preparation is an irregular series of trips to the bathroom with intermittent periods of normalcy and sleep. Recovery may also be comprised of intermittent periods of normalcy. Therefore, we valued several time intervals (total time, prep to routine time, occupied time, and dedicated time) to produce a range of plausible estimates.

2.4 Data Analysis

Our initial analysis focused on descriptive statistics for the study subjects. Subjects not returning the diary or questionnaire (n=12) were excluded from the analysis. We used the two economic techniques, WTP and the human capital method, as described above to estimate the value of patients’ time. We assessed the consistency of responses to the two WTP questions for each subject. Responses were defined as consistent if the dollar amount entered for the open-ended question was within one dollar of the limits of the range chosen for the payment-scale question. For example, a response between $99 and $250 to the open-ended question was considered consistent with a response of $100–$249 to the payment-scale question.

2.4.1 WTP and Human Capital Method Correlations

We assessed correlation of the WTP and human capital methods for each individual by comparing the results of the open-ended WTP question with the human capital method values for total time, prep to routine time, occupied time, and dedicated time. We calculated Spearman’s correlations since the data were not normally distributed.

2.4.2 Effect of Patient Characteristics on WTP

We examined differences in WTP by subject characteristics, including age, sex, race, educational attainment, income, insurance, colonoscopy experience, prep experience, employment status, work days missed, complications, travel distance, travel cost, and out-of-pocket cost. We used nonparametric statistics because the WTP data from the open-ended question were not normally distributed. We calculated medians and p values using Wilcoxon rank-sum for variables with two categories and Kruskal-Wallis for variables with more than two categories. We calculated correlations with willingness-to-pay for continuous variables using Spearman’s correlation.

2.4.3 Linear Regression Analysis

To explore what factors determined subjects’ WTP responses, we ran least squares regressions using the open-ended WTP responses as the dependent variable. First, we included independent variables for all characteristics that were related to WTP in the bivariate analysis (p<0.05). Next, we explored the effects of including our measures of time (prep to routine time, occupied time, and dedicated time) as independent variables.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Recruitment

We contacted 176 patients through telephone and on-site recruiting. Of these, 31 refused, six were ineligible, and 139 agreed to be in the study. Thus, 82% (139/170) of the eligible patients contacted agreed to participate. Seventeen patients did not attend their colonoscopy or were rescheduled for a later date or different location and 12 did not return the survey materials. Overall, 110 of the 139 subjects (79%) completed the study. Of those, 99 answered both WTP questions.

3.2 Subject Characteristics

Participants were older (mean age 61.9 years), well-educated, and generally in good health (Table I). They were able to perform all activities of daily living without any assistance except for one individual who needed assistance walking.

Table I.

Patient characteristics (n=110)

| Characteristic | Percent |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (s.d.) | 61.9 (7.6), range 50–81 |

| Female | 57 |

| White | 85 |

| Insured | 90 |

| Medicare | 40 |

| Medicaid | 4 |

| Employment status | |

| Employed | 45 |

| Unemployed | 1 |

| Housewife/husband | 4 |

| Retired | 39 |

| Disabled | 11 |

| Annual household income range | |

| 0 to $14,999 | 14 |

| $15,000 to $29,999 | 5 |

| $30,000 to $59,999 | 19 |

| $60,000 to $89,999 | 18 |

| $90,000 or greater | 33 |

| Did not wish to answer | 11 |

| Educational level | |

| 11th grade or lower | 2 |

| High school graduate or GED | 8 |

| some college or vocational school | 15 |

| 2-year college degree | 7 |

| 4-year college degree | 21 |

| Professional or graduate degree | 46 |

| Self-rated general health: | |

| Excellent or very good | 69 |

| Good | 21 |

| Fair or poor | 10 |

| History of: | |

| Cancer (any type) | 29 |

| Arthritis | 35 |

| Diabetes | 9 |

| Heart Disease/Heart Failure | 10 |

| Asthma | 8 |

| COPD | 5 |

| Depression | 21 |

| Number of people in household | |

| One | 18 |

| Two | 60 |

| Three | 13 |

| Four or more | 9 |

The mean total time was 81.5 hours (median 72, range 32–344), mean prep to routine time was 39.9 hours (37.2, 16.0–118.0), mean occupied time was 23.2 hours (20.8, 13.1–88.3), and mean dedicated time was 4.4 hours (3.9, 1.3–13.8).

3.3 Value of Patient Time and Discomfort

3.3.1 Willingness-to-pay

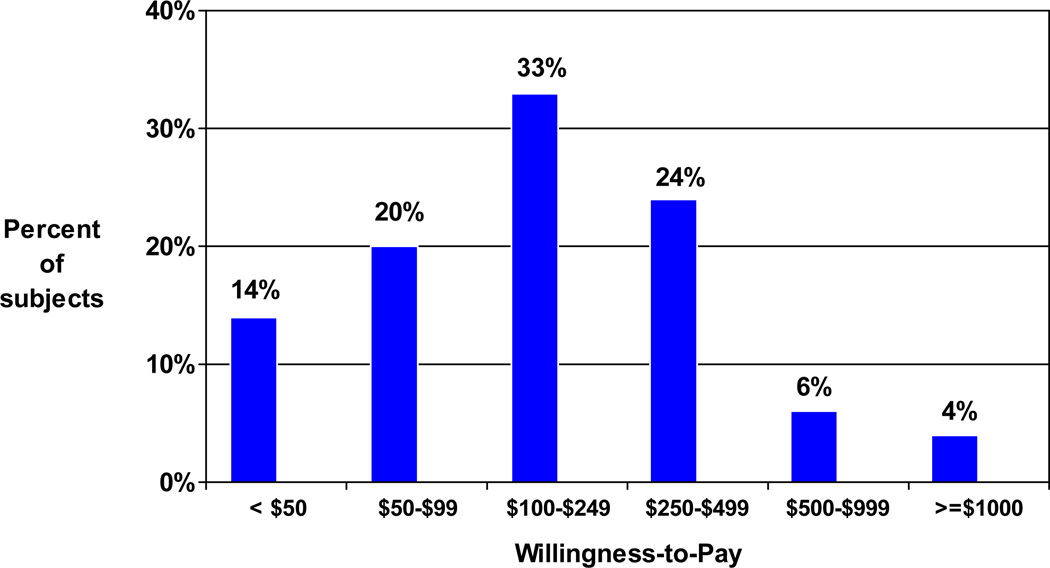

Mean WTP from the open-ended question was $263 (median $200, range $0–$2000, n=99 responses). On the payment-scale question, 14% of subjects selected <$50, 20% chose $50–$99, 33% chose $100–$249, 24% chose $250–$499, 6% chose $500–$999, and 4% chose $1000 or more (Figure 1). Consistent answers to the two WTP questions were given by 92% (91/99) of subjects.

Figure 1.

Willingness-to-Pay Ranges from the Payment-scale Question

3.3.2 Human capital method

Using national wage averages, the mean value of patients’ total time was $1518 (median $1340, range $596–$6405), prep to routine time was $743 ($693, $298–$2197), occupied time was $432 ($391, $244–$1643), and dedicated time was $81 ($73, $23–$258). Using subjects’ personal income data to value time produced significantly larger mean values: $2419 (median $2241, range $46–$7851), $1147 ($997, $70–$4441), $702 ($746, $74–$3598), and $122 ($130, $11–$303), respectively.

3.3.3 Correlations between willingness-to-pay and the human capital method

There were no significant correlations between WTP and various time intervals valued at average national wage rates (Table II). WTP was moderately correlated with the human capital value of patients’ time using individual patients’ hourly wage rates for prep to routine time (r=0.32, p=0.003), occupied time (r= 0.42, p<0.001), and dedicated time (r=0.29, p=0.008).

Table II.

Correlations Between the Willingness-to-pay (from the open-ended question) and Human Capital Method Values of Time

| Human Capital Method Time interval valued, hourly value used |

Correlation with WTP | p* |

|---|---|---|

| National average wage | ||

| Prep to routine time, (mean $743, range $298–$2197) | −0.09 | 0.42 |

| Occupied time, (mean $432, range $244–$1643) | 0.06 | 0.56 |

| Dedicated time, (mean $81, range $23–$258) | −0.19 | 0.07 |

| Hourly income | ||

| Prep to routine time, (mean $1147, range $70–$4441) | 0.32 | 0.003 |

| Occupied time, (mean $702, range $74–$3598) | 0.42 | <0.001 |

| Dedicated time, (mean $122, range $11–$303) | 0.29 | 0.008 |

Spearman’s

Note: Mean WTP from the open-ended question was $263 (median $200, range $0–$2000, n=99 responses). On the payment-scale WTP question, 14% of subjects selected <$50, 20% chose $50–$99, 33% chose $100–$249, 24% chose $250–$499, 6% chose $500–$999, and 4% chose $1000 or more.

3.3.4 Focus Group Findings

Most of the respondents (9 out of 13) seemed to understand the WTP questions as they were intended. When asked how they would explain the questions in their own words, their answers included the following: “…what would I be willing to pay not to spend so many hours getting ready for this exam?”; “…what would I be willing to pay not to suffer”; “instead of going in with all the preparation time and lost time, inconveniencing other people, what was I willing to pay out of pocket?”; “…I think one of the key things that they are saying is the discomfort is so much that you’re willing, if there’s something else, …to pay…x amount of dollars. It’s just so that you don’t have the discomfort of drinking and doing all that. Would it be worth it to you to forego that?”

A minority (n=4) had assumed that the questions were intended to determine the price of a new technology or that the questions were too long and complicated: “the purpose is I think to gather information to see whether the new method is sellable to the public…How it’s going to go over. Sort of a pre-market study. … Or a market study.”; “I think you mean what you are willing to pay out of pocket for the procedure…without the health insurance.”; “I think it’s too long, too complicated.”

When asked what kinds of things impacted their answers most, participants emphasized dislike of the preparation, lost time for self and others, ability to pay, amount of coinsurance, and embarrassment: “…the memory of the liquid. The taste lingered you know, I could taste that stuff for a week afterwards in my mind.”; “you’d have to go through another prep”; “…the lost day”; “ability to pay”; “I think I used my cost share as the [amount].”; “my husband’s doctor finally talked him into having one … But he would be much more willing to do something to avoid the embarrassment because that’s what it is to him, sheer embarrassment.”

3.4 Effect of Patient Characteristics on Willingness-to-Pay

The relationships between patient characteristics and WTP are examined in Tables III and IV. WTP was sensitive (p<0.05) to missing household chores, missing leisure activities, difficulty of the overall colonoscopy experience, difficulty of the preparation, race, education, having insurance, and income. There was no significant difference in WTP for patients who reported bad effects from the colonoscopy compared to those who did not. Nor was there a significant difference for subjects with different estimates of their risk for colon cancer.

Table III.

Effect of Patient Characteristics on Willingness-to-pay

| Characteristic | n | Median* | p* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 42 | 200 | 0.983 |

| Female | 56 | 200 | |

| Prep type | |||

| NuLytely (0) | 88 | 200 | 0.467 |

| Fleets (1) | 10 | 237.5 | |

| First colonoscopy | |||

| Yes | 58 | 200 | 0.447 |

| No | 36 | 225 | |

| Reason | |||

| Screening colonoscopy | 95 | 200 | 0.759 |

| Polyp surveillance | 2 | 300 | |

| Family history (1st degree relative) | |||

| Yes | 11 | 200 | 0.631 |

| No | 82 | 200 | |

| Feel completely back to normal 1 wk after colonoscopy | |||

| Yes | 93 | 200 | 0.385 |

| No | 4 | 275 | |

| Missed paid work | |||

| Yes | 42 | 225 | 0.454 |

| No | 54 | 150 | |

| Missed household chores | |||

| Yes | 46 | 250 | 0.032 |

| No | 50 | 175 | |

| Missed caring for others | |||

| Yes | 28 | 175 | 0.262 |

| No | 68 | 200 | |

| Missed leisure activities | |||

| Yes | 45 | 250 | 0.049 |

| No | 51 | 150 | |

| Missed other activities | |||

| Yes | 14 | 237.5 | 0.364 |

| No | 83 | 200 | |

| “Bad effects” from colonoscopy: | |||

| Yes | 16 | 250 | 0.103 |

| No | 79 | 200 | |

| History of cancer, any type | 30 | 200 | 0.957 |

| No history of cancer | 68 | 200 | |

| Colonoscopy experience | |||

| Moderately or very easy | 55 | 150 | 0.007 |

| Neither easy nor difficult | 17 | 200 | |

| Moderately or very difficult | 22 | 250 | |

| Work days missed | |||

| Zero | 16 | 100 | 0.214 |

| Part of a day | 8 | 250 | |

| One | 22 | 250 | |

| Two | 8 | 212.5 | |

| Three or more | 1 | 20 | |

| Not applicable | 40 | 200 | |

| Preparation for colonoscopy (3 cat) | |||

| Moderately or very easy | 31 | 100 | <0.001 |

| Neither easy nor difficult | 19 | 100 | |

| Moderately or very difficult | 46 | 250 | |

| Mode of transportation | |||

| Personal/family car | 78 | 200 | 0.065 |

| Friend’s car | 16 | 100 | |

| Taxi | 0 | ||

| Bus | 0 | ||

| Other | 4 | 275 | |

| Who accompanied patient | |||

| Spouse or significant other | 62 | 200 | 0.151 |

| Relative | 13 | 250 | |

| Friend | 19 | 150 | |

| Other | 4 | 75 | |

| Roundtrip distance | |||

| Less than 5 miles | 13 | 300 | 0.436 |

| 5 to 9.9 miles | 20 | 225 | |

| 10 to 19.9 miles | 27 | 200 | |

| 20 to 29.9 miles | 15 | 100 | |

| 30 to 49.9 miles | 11 | 250 | |

| 50 or more miles | 12 | 237.5 | |

| Recovery from colonoscopy | |||

| Very easy | 56 | 212.5 | 0.619 |

| Moderately easy | 26 | 175 | |

| Neither easy nor difficult | 5 | 150 | |

| Moderately difficult | 6 | 100 | |

| Very difficult | 1 | 150 | |

| Risk of colon cancer compared to others your age (self reported) | |||

| Lower | 37 | 100 | 0.090 |

| Average | 51 | 200 | |

| Higher | 10 | 275 | |

| How effective do you think colonoscopy is…? | |||

| Completely ineffective | |||

| Not very effective | 2 | 150 | 0.375 |

| Moderately effective | 0 | ||

| Very effective | 24 | 150 | |

| 72 | 212.5 | ||

| General Health | |||

| Excellent | 27 | 250 | 0.072 |

| Very good | 44 | 200 | |

| Good | 19 | 150 | |

| Fair | 6 | 99.5 | |

| Poor | 2 | 137.69 | |

| Race | |||

| White | 86 | 225 | 0.011 |

| Black/African American | 9 | 100 | |

| Hispanic | 1 | 75 | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1 | 100 | |

| Other | 0 | ||

| Education | |||

| 7th grade or lower | 0 | 0.033 | |

| 8th through 11th grade | 1 | 200 | |

| High school graduate or GED | 6 | 50 | |

| Some college or vocational sch. | 13 | 150 | |

| 2-year college | 6 | 100 | |

| 4-year college | 22 | 237.5 | |

| Professional or graduate degree | 50 | 225 | |

| Insured | 90 | 200 | 0.050 |

| Not insured | 7 | 100 | |

| Medicare | |||

| Yes | 39 | 150 | 0.089 |

| No | 58 | 225 | |

| Medicaid | |||

| Yes | 2 | 175 | 0.321 |

| No | 94 | 200 | |

| Number of people in household: | |||

| One | 17 | 150 | 0.107 |

| Two | 59 | 200 | |

| Three | 14 | 200 | |

| Four | 5 | 225 | |

| Five | 3 | 500 | |

| Six | 0 | ||

| Seven or more | 0 | ||

| Annual Household Income | |||

| 0 to $14,999 | 9 | 100 | 0.005 |

| $15,000 to $29,999 | 6 | 125 | |

| $30,000 to $44,999 | 8 | 100 | |

| $45,000 to $59,999 | 12 | 100 | |

| $60,000 to $74,999 | 10 | 150 | |

| $75,000 to $89,999 | 10 | 212.5 | |

| $90,000 or greater | 33 | 250 | |

| Did not wish to answer | 10 | 325 | |

| Current employment status: | |||

| Employed | 46 | 250 | 0.095 |

| Unemployed | 1 | 500 | |

| Housewife/husband | 4 | 250 | |

| Retired | 40 | 150 | |

| Disabled | 7 | 100 | |

Medians and p values calculated using wilcoxon rank-sum for variables with two categories and using Kruskal-Wallis for variables with more than two categories.

Table IV.

Correlations Between Patient Characteristics and Willingess-to-pay (from the open-ended question)

| Characteristic | Correlation | p* |

|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.10 | 0.33 |

| Travel cost | −0.11 | 0.29 |

| Out-of-pocket cost | 0.26 | 0.03 |

| Prep to routine time | −0.08 | 0.42 |

| Occupied time | −0.03 | 0.77 |

| Dedicated time | −0.22 | 0.03 |

| Travel time | −0.31 | 0.002 |

| Hourly income | 0.40 | <0.001 |

Spearman’s correlation

WTP was correlated with out-of-pocket cost. As out-of-pocket cost increased, so did willingness-to-pay (correlation 0.26, p=0.03). Increased travel time was correlated with lower WTP (−0.31, p<0.01), as was increased dedicated time (−0.22, p=0.03). There were no significant correlations with age, travel cost, prep to routine time, or occupied time.

3.5 Linear Regression Analysis

Linear regressions showed that WTP was related to the difficulty of the preparation. When all variables that had significant bivariate relationships with WTP (p<0.05, Table III) were included, the difficulty of the preparation added $147 to WTP (p=0.03). Further regressions found a dose-response relationship for difficulty of the preparation; with subjects who experienced moderate difficulty adding $147 to WTP (p < 0.01) and those who found it very difficult adding $187 (p=0.02). The regressions including time variables (prep to routine, occupied, and dedicated) found that the amount of elapsed time spent in the screening colonoscopy process was not significantly related to WTP.

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we asked patients their willingness-to-pay to avoid the time and discomfort of the colonoscopy screening process. We also measured the elapsed time involved in the process and valued it using the human capital method. Our willingness-to-pay questions incorporated the value of patient time and discomfort; the human capital method valued only time. The mean willingness-to-pay to avoid the colonoscopy process while still receiving its benefits was $263. This was substantially lower than the human capital values for the three longest time intervals valued using either national wage averages or subjects’ individual hourly wages, but substantially greater than the human capital values for the shortest time interval (from leaving home to go to the endoscopy center until arriving at home after the procedure: $81 using national wage averages and $122 using subjects’ hourly wages).

The lower WTP values are noteworthy since WTP, but not the human capital values, include patients’ valuation of the discomfort of the colonoscopy process. We suspect that the WTP values are lower in large part because much of the time spent in the colonoscopy process does not involve continuous activity and is thus less than the elapsed time measured by the time diary. Since the colonoscopy process involves intermittent periods of time, some only partially occupied by the process, the human capital method may overestimate the time spent and thus the value of that time. The WTP method allows patients to value only the time actually devoted to the process, a point that may be important for valuing time spent in other health-care activities during which multitasking (such as reading, using a computer, making telephone calls) may occur.

When various time intervals were valued by the national average wage, there were no significant correlations with WTP. However, there were moderate correlations (r=0.32, 0.42, and 0.29) between WTP and the human capital values of these time intervals when they were valued by subjects’ personal hourly income, indicating that different subjects place different values on their time and that these values are related to their individual wages. The correlations suggest that WTP responses may have been influenced more by personal income than by differences in the time invested in the screening colonoscopy process.

The relationships between patient characteristics and WTP revealed some of the factors that influenced subjects’ WTP. As expected, WTP was sensitive to income. Economic theory suggests that individuals with higher incomes value their time more highly than those with lower incomes because the next best use of their time, the opportunity cost, is more valuable. Subjects were willing to pay larger amounts, again indicating greater opportunity costs, if they missed household chores or leisure activities than if they did not. In addition, as expected, subjects were willing to pay more as the difficulty of the preparation or of the overall colonoscopy experience increased.

Some of our data, however, show that WTP is influenced by various patient characteristics in unexpected ways. These findings suggest that the method needs further evaluation and development to better ensure it is measuring what is intended. For example, we would expect that WTP for an alternative method of screening for colon cancer might increase among those that reported bad effects from the colonoscopy compared to those that did not. Yet, this was not the case. In addition, increasing out-of-pocket cost was correlated with increased WTP despite the wording of our question that directed subjects to assume that they had no out-of-pocket expenses. Also, increasing travel time was correlated with decreased WTP. We expected that greater travel times would result in individuals willing to pay greater amounts to avoid the colonoscopy process.

Our multivariate analysis found that the difficulty of the preparation was the main determinant of WTP. This finding is supported by our focus group information and suggests that the disutility of the preparation has a large influence on subjects’ WTP to avoid the colonoscopy screening process.

Other studies have used variants of the human capital method to value time spent receiving health services or in self-care (Attard et al., 2005, Bech and Gyrd-Hansen, 2000, Bryan et al., 1995, Cantor et al., 2006, Cromwell et al., 1997, Frew et al., 1999, Jonas et al., 2008, Lawrence et al., 2001, Robbins et al., 2002, Salome et al., 2003, Sculpher et al., 2000, Shireman et al., 2001, Yabroff et al., 2005). Some of these used patients’ personal wages while others used national or state wage data. To our knowledge, only two studies (Borisova and Goodman, 2003, Borisova and Goodman, 2004, Tilford, 1993) have used WTP methods for the purpose of valuing patient time. The first of these used WTP for reduction in doctor’s office waiting time to measure the value of time for the elderly (Tilford, 1993). The second study compared the use of WTP, willingness-to-accept (WTA), and wage rates for measuring the value of travel time for methadone maintenance clients (Borisova and Goodman, 2003, Borisova and Goodman, 2004). The authors found that the wage rate was not correlated with either WTP or WTA. They concluded that using WTP was preferable to using wage rates in measuring the value of time because WTP predicted treatment attendance.

Determining the appropriate value of patients’ time can be complicated. Willingness-to-pay and the human capital method each have inherent advantages, disadvantages, and limitations. The human capital method, which values each hour of time using wage rates, values all time equally as a cost, separate from any satisfaction or dissatisfaction that occurs during that time. However, the wage rate is not necessarily equivalent to the value of time. There are several factors that may disrupt the equality, including: not working for market wages, paid sick leave, direct utility or disutility of time spent consuming medical care, and reduction of the opportunity cost of time due to illness (Borisova and Goodman, 2003, Borisova and Goodman, 2004, Cauley, 1987). In addition, the human capital method is more difficult to apply to those outside the workforce (retired, disabled, children) who don’t have or are not well characterized by wage rates. Those outside the workforce may value time differently from the wage they could earn.

Another disadvantage of the human capital method in the context of a procedure like a screening colonoscopy is that it may be difficult to determine the appropriate time interval or amount of time to value when the time devoted to the process is not continuous or is not completely devoted to one activity. As noted, the time spent during the colonoscopy preparation is an irregular series of trips to the bathroom with intermittent periods of normalcy and sleep. Recovery may follow a similar pattern. Determining which portion of this time to value or accurately measuring the true time spent can be difficult (Jonas et al., 2008).

For WTP, the goal is to determine the maximum amount one is willing to pay either for a health benefit or to avoid something undesirable. In the context of valuing time, WTP does not require valuing all time equally. For the purposes of valuing time for cost-effectiveness analyses, WTP allows the value of time and the utility/disutility to be determined using one measure, rather than having to do them separately. As exemplified in this study, WTP enabled us to measure the time and discomfort related to screening colonoscopy with one question, rather than having to measure time and discomfort separately. The WTP method also does not necessitate a determination of the quantity of time invested in the activity being evaluated. In other words, where the time demands are irregular, or the time only partially occupied, WTP has the advantage of allowing individuals to consider this in their contingent valuation, rather than requiring investigators to accurately measure the time involved. The WTP method, however, may be limited by the difficulty of designing questions that measure what they are intended to measure.

The time costs and disutility associated with screening colonoscopy are important for understanding the cost-effectiveness of colon cancer screening. We have previously demonstrated how the human capital value of the time patients invest in the screening colonoscopy process should be incorporated into a cost-effectiveness analysis (Jonas et al., 2008). In short, it should be included as a cost in the numerator. Similarly, WTP valuation of the time and discomfort could be incorporated in the numerator of a cost-effectiveness analysis as a cost. However, it is important to avoid double counting. That is, the discomfort/disutility should not also be included in the denominator.

4.1 Limitations

Our WTP questions incorporated the value of patient time and discomfort whereas the human capital method valued only time. Thus, the numerical dollar value results for these different measures should not be compared as though they were measuring the same thing. The comparison is only useful to explore some of the differences and potential uses of the two methods. Willingness-to-pay questions that measure only patient time could be constructed, allowing direct comparison of the resulting dollar values if that was the aim.

Next, the range of response choices for the payment-scale WTP question may have influenced participant responses to the open-ended question. The two questions had identical wording and the payment-scale question was asked before the open-ended question. However, since we pre-tested our WTP questions to choose ranges for the payment-scale question, it may also be that the payment-scale ranges accurately captured the range of values respondents had in mind for WTP.

Another limitation is the uncertainty about how well the WTP questions are measuring what we intended to measure. Our focus group results and the relationships we observed suggest that some respondents were not valuing their time or may have been responding based on external benchmarks such as the out-of-pocket charges for the procedure. This may have been due to the wording of our WTP questions; they did not explicitly state the period of time we wanted subjects to consider. Further research in the development and testing of these questions is needed to determine if they are measuring what we intended to measure.

Our results are based on one endoscopy center and our study sample is not representative of the national population. Given that our sample was relatively wealthy and that WTP and perhaps the value of time depend on patients’ wealth, the characteristics of our sample limit the generalizability of some of our results. The patient population of other centers may result in different values of time and WTP.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Mean WTP to avoid the time and discomfort associated with the colonoscopy process while still receiving its benefits was $263. WTP values to avoid the time and discomfort involved in the screening colonoscopy process were substantially lower than most of the human capital values for elapsed time alone, probably reflecting patients’ ability to adjust for the episodic nature of the time required for preparation and recovery. The human capital method may overestimate the value of time in situations that involve an irregular, episodic series of time intervals, or situations that involve multitasking. With further methodological development, WTP holds promise as a means to estimate patient time costs.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- Attard NJ, Zarb GA, Laporte A. Long-term treatment costs associated with implant-supported mandibular prostheses in edentulous patients. Int J Prosthodont. 2005;18:117–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bech M, Gyrd-Hansen D. Cost implications of routine mammography screening of women 50–69 years in the county of Funen, Denmark. Health Policy. 2000;54:125–141. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(00)00104-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmo TS, Wangberg SC. Patients' willingness to pay for electronic communication with their general practitioner. Eur J Health Econ. 2007;8:105–110. doi: 10.1007/s10198-006-0014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boonen A, Severens JL, Van Tubergen A, Landewe R, Bonsel G, Van der Heijde D, Van der Linden S. Willingness of patients with ankylosing spondylitis to pay for inpatient treatment is influenced by the treatment environment and expectations of improvement. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:1650–1652. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.038786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borisova NN, Goodman AC. Measuring the value of time for methadone maintenance clients: willingness to pay, willingness to accept, and the wage rate. Health Econ. 2003;12:323–334. doi: 10.1002/hec.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borisova NN, Goodman AC. The effects of time and money prices on treatment attendance for methadone maintenance clients. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004;26:345–352. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan S, Buxton M, Mckenna M, Ashton H, Scott A. Private costs associated with abdominal aortic aneurysm screening: the importance of private travel and time costs. J Med Screen. 1995;2:62–66. doi: 10.1177/096914139500200202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne MM, O'Malley K, Suarez-Almazor ME. Willingness to pay per quality-adjusted life year in a study of knee osteoarthritis. Med Decis Making. 2005;25:655–666. doi: 10.1177/0272989X05282638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor SB, Levy LB, Cardenas-Turanzas M, Basen-Engquist K, Le T, Beck JR, Follen M. Collecting direct non-health care and time cost data: application to screening and diagnosis of cervical cancer. Med Decis Making. 2006;26:265–272. doi: 10.1177/027298906288679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauley SD. The Time Price of Medical Care. Rev Econ Stat. 1987;69:59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Cromwell J, Bartosch WJ, Fiore MC, Hasselblad V, Baker T. Cost-effectiveness of the clinical practice recommendations in the AHCPR guideline for smoking cessation. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Jama. 1997;278:1759–1766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez L. Assessing the willingness of parents to pay for reducing postoperative emesis in children. Pharmacoeconomics. 1998;13:589–595. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199813050-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fautrel B, Clarke AE, Guillemin F, Adam V, St-Pierre Y, Panaritis T, Fortin PR, Menard HA, Donaldson C, Penrod JR. Costs of rheumatoid arthritis: new estimates from the human capital method and comparison to the willingness-to-pay method. Med Decis Making. 2007;27:138–150. doi: 10.1177/0272989X06297389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frew E, Wolstenholme JL, Atkin W, Whynes DK. Estimating time and travel costs incurred in clinic based screening: flexible sigmoidoscopy screening for colorectal cancer. J Med Screen. 1999;6:119–123. doi: 10.1136/jms.6.3.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frew E, Wolstenholme JL, Whynes DK. Willingness-to-pay for colorectal cancer screening. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:1746–1751. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frew EJ, Whynes DK, Wolstenholme JL. Eliciting willingness to pay: comparing closed-ended with open-ended and payment scale formats. Med Decis Making. 2003;23:150–159. doi: 10.1177/0272989X03251245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, Weinstein MC. Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg D, Bakhai A, Neumann PJ, Cohen DJ. Willingness to pay for avoiding coronary restenosis and repeat revascularization: results from a contingent valuation study. Health Policy. 2004;70:207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueylard Chenevier D, Lelorier J. A willingness-to-pay assessment of parents' preference for shorter duration treatment of acute otitis media in children. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23:1243–1255. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200523120-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He M, Chan V, Baruwa E, Gilbert D, Frick KD, Congdon N. Willingness to pay for cataract surgery in rural Southern China. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:411–416. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimoh A, Sofola O, Petu A, Okorosobo T. Quantifying the economic burden of malaria in Nigeria using the willingness to pay approach. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2007;5:6. doi: 10.1186/1478-7547-5-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannesson M, Johansson PO, Kristrom B, Gerdtham UG. Willingness to pay for antihypertensive therapy--further results. J Health Econ. 1993;12:95–108. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(93)90042-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannesson M, Jonsson B, Borgquist L. Willingness to pay for antihypertensive therapy--results of a Swedish pilot study. J Health Econ. 1991;10:461–473. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(91)90025-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannesson M, O'conor RM, Kobelt-Nguyen G, Mattiasson A. Willingness to pay for reduced incontinence symptoms. Br J Urol. 1997;80:557–562. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1997.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas DE, Russell LB, Sandler RS, Chou J, Pignone M. Patient time requirements for screening colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2401–2410. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas DE, Russell LB, Sandler RS, Chou J, Pignone M. Value of patient time invested in the colonoscopy screening process: time requirements for colonoscopy study. Med Decis Making. 2008;28:56–65. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07309643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence WF, Peshkin BN, Liang W, Isaacs C, Lerman C, Mandelblatt JS. Cost of genetic counseling and testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 breast cancer susceptibility mutations. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:475–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narbro K, Sjostrom L. Willingness to pay for obesity treatment. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2000;16:50–59. doi: 10.1017/s0266462300016159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oscarson N, Lindholm L, Kallestal C. The value of caries preventive care among 19-year olds using the contingent valuation method within a cost-benefit approach. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35:109–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps CE. Health economics. Boston: Addison Wesley; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto-Prades JL, Farreras V, De Bobadilla JF. Willingness to pay for a reduction in mortality risk after a myocardial infarction: an application of the contingent valuation method to the case of eplerenone. Eur J Health Econ. 2008;9:69–78. doi: 10.1007/s10198-007-0041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins JM, Tilford JM, Gillaspy SR, Shaw JL, Simpson DD, Jacobs RF, Wheeler JG. Parental emotional and time costs predict compliance with respiratory syncytial virus prophylaxis. Ambul Pediatr. 2002;2:444–448. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2002)002<0444:peatcp>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell LB, Gold MR, Siegel JE, Daniels N, Weinstein MC. The role of cost-effectiveness analysis in health and medicine. Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. Jama. 1996;276:1172–1177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadri H, Mackeigan LD, Leiter LA, Einarson TR. Willingness to pay for inhaled insulin: a contingent valuation approach. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23:1215–1227. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200523120-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safford MM, Russell L, Suh DC, Roman S, Pogach L. How much time do patients with diabetes spend on self-care? J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18:262–270. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.18.4.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salome HJ, French MT, Miller M, Mclellan AT. Estimating the client costs of addiction treatment: first findings from the client drug abuse treatment cost analysis program (Client DATCAP) Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;71:195–206. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00133-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sculpher M, Palmer MK, Heyes A. Costs incurred by patients undergoing advanced colorectal cancer therapy. A comparison of raltitrexed and fluorouracil plus folinic acid. Pharmacoeconomics. 2000;17:361–370. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200017040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secker-Walker RH, Vacek PM, Hooper GJ, Plante DA, Detsky AS. Screening for breast cancer: time, travel, and out-of-pocket expenses. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:702–708. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.8.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shireman TI, Tsevat J, Goldie SJ. Time costs associated with cervical cancer screening. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2001;17:146–152. doi: 10.1017/s0266462301104137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slothuus U, Larsen ML, Junker P. Willingness to pay for arthritis symptom alleviation. Comparison of closed-ended questions with and without follow-up. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2000;16:60–72. doi: 10.1017/s0266462300016160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang CH, Liu JT, Chang CW, Chang WY. Willingness to pay for drug abuse treatment: results from a contingent valuation study in Taiwan. Health Policy. 2007;82:251–262. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilford J. PhD thesis. Detroit, Michigan: Department of Economics, Wayne Sate University; 1993. Coinsurance, willingness to pay for time, and elderly health care demand. [Google Scholar]

- Unutzer J, Katon WJ, Russo J, Simon G, Von Korff M, Lin E, Walker E, Ludman E, Bush T. Willingness to pay for depression treatment in primary care. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:340–345. doi: 10.1176/ps.54.3.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner TH, Hu TW, Duenas GV, Pasick RJ. Willingness to pay for mammography: item development and testing among five ethnic groups. Health Policy. 2000;53:105–121. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(00)00085-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh BM, Bartfield JM. Survey of parental willingness to pay and willingness to stay for "painless" intravenous catheter placement. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22:699–703. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000238743.96606.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whynes DK, Frew E, Wolstenholme JL. A comparison of two methods for eliciting contingent valuations of colorectal cancer screening. J Health Econ. 2003;22:555–574. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(03)00006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabroff KR, Warren JL, Knopf K, Davis WW, Brown ML. Estimating patient time costs associated with colorectal cancer care. Med Care. 2005;43:640–648. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000167177.45020.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasunaga H, Ide H, Imamura T, Ohe K. Analysis of factors affecting willingness to pay for cardiovascular disease-related medical services. Int Heart J. 2006a;47:273–286. doi: 10.1536/ihj.47.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasunaga H, Ide H, Imamura T, Ohe K. Benefit evaluation of mass screening for prostate cancer: willingness-to-pay measurement using contingent valuation. Urology. 2006b;68:1046–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasunaga H, Ide H, Imamura T, Ohe K. The measurement of willingness to pay for mass cancer screening with whole-body PET (positron emission tomography) Ann Nucl Med. 2006c;20:457–462. doi: 10.1007/BF02987254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasunaga H, Ide H, Imamura T, Ohe K. Women's anxieties caused by false positives in mammography screening: a contingent valuation survey. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;101:59–64. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9270-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarkin GA, Cates SC, Bala MV. Estimating the willingness to pay for drug abuse treatment: a pilot study. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2000;18:149–159. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(99)00030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.