Abstract

The plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium Ochrobactrum lupini KUDC1013 elicited induced systemic resistance (ISR) in tobacco against soft rot disease caused by Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum. We investigated of its factors involved in ISR elicitation. To characterize the ISR determinants, KUDC1013 cell suspension, heat-treated cells, supernatant from a culture medium, crude bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and flagella were tested for their ISR activities. Both LPS and flagella from KUDC1013 were effective in ISR elicitation. Crude cell free supernatant elicited ISR and factors with the highest ISR activity were retained in the n-butanol fraction. Analysis of the ISR-active fraction revealed the metabolites, phenylacetic acid (PAA), 1-hexadecene and linoleic acid (LA), as elicitors of ISR. Treatment of tobacco with these compounds significantly decreased the soft rot disease symptoms. This is the first report on the ISR determinants by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) KUDC1013 and identifying PAA, 1-hexadecene and LA as ISR-related compounds. This study shows that KUDC1013 has a great potential as biological control agent because of its multiple factors involved in induction of systemic resistance against phytopathogens.

Keywords: biological control, induced systemic resistance (ISR), Ochrobactrum lupini KUDC1013, plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR)

Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) are non-pathogenic bacteria colonizing the surface of plant roots with beneficial effects on plant health and growth, provide protection to some unfavorable environmental conditions, suppress phytopathogens and accelerates nutrient availability and assimilation (Babalola, 2010). The use of PGPR is an environment-friendly alternative to control plant diseases commonly caused by deleterious pathogens. Plant diseases are often controlled using resistant plants and hazardous chemicals. However, resistance does not occur against a wide array of diseases and producing resistant plants takes many years (Lugtenberg and Kamilalova, 2009) while application of chemicals to enhance plant growth or induce resistance is limited because of the negative effects of chemical treatment as well as the difficulty to determine the optimal concentrations to benefit plants (Ryu et al., 2005).

The utilization of PGPR is considered as a favorable approach to augment plant immunity and to control plant diseases. PGPR has diverse mechanisms in controlling diseases including direct antibiosis (Chin et al., 1998; Dunne et al., 1998; Haas et al., 2003), competition of nutrient and niches (Han et al., 2006; Kamilova et al., 2005) and induction of systemic resistance (ISR) (Jetiyanon and Kloepper, 2002; van Peer et al., 1991). ISR is an elevated resistance observed in the whole plant and not only at the site colonized by the rhizobacteria (Kloepper et al., 1992). ISR is phenotypically similar to systemic acquired resistance (SAR) which is evident by direct antibiosis between the inducing bacterium and the challenging pathogen and the maximum level of SAR is expressed when the inducing organism causes necrosis (Cameron et al., 1994), whereas ISR by rhizobacteria typically do not cause any necrotic symptoms on the host plants (van Loon et al., 1998). The utilization of SAR inducing organisms has not been successful under field conditions and generally, the duration of protection is less following induction of a pathogen than that with rhizobacteria-mediated ISR (Wei et al., 1991). Also, PGPR mediated ISR is effective against a wide array of fungal, bacterial and viral plant pathogens (van Loon et al., 1998).

Many individual PGPR components induce ISR such as cell wall components flagellin (Gomez-Gomez and Boller, 2002) and lipopolysaccharides (van Peer and Schippers, 1992; Leeman et al., 1995). Various secondary metabolites produced by some PGPR strains were found to elicit ISR such as 4-aminocarbonyl phenylacetate (Park et al., 2009), N-alkylated benzylamine derivative (Ongena et al., 2005), butyl 2-pyrrolidone-5-carboxylate (Park et al., 2009). Some PGPR strains release volatile organic compounds (VOCs) involved in ISR activity such as 2-3-butanediol and acetoin (Ryu et al., 2004). These PGPR metabolites have received much attention as part of agricultural methodologies that provide an alternative to synthetic chemicals for pathogen control (Park et al., 2009). Thus, finding new microbial metabolites with ISR activity against plant pathogens is of great interest in agriculture.

Ochrobactrum lupini KUDC1013 elicits ISR in pepper against bacterial spot caused by Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. vesicatoria and in tobacco against leaf soft rot caused by Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum (Ham et al., 2009; Hahm et al., 2012). Recently, KUDC1013 has been found to elicit ISR in pepper against fungal pathogen Stemphylium lycopersici causing gray leaf spot disease (unpublished data). This strain has great potential as biological control agent especially in eliciting ISR; however, the determinants of KUDC1013 involved in ISR activity remain unknown. The present study aims to identify the determinants of KUDC1013 involved in ISR elicitation. The role of LPS, flagella and cell free extracts of KUDC1013 to confer ISR activity was investigated.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains

PGPR strain Ochrobactrum lupini KUDC1013, originally isolated from the rhizosphere of Solanum nigrum L. in Dokdo island Korea and which was reported to promote growth and induce systemic resistance in tobacco against leaf soft rot was used (Ham et al., 2009). For experimental use, KUDC1013 was streaked on Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) plates (Difco Laboratories, USA) and incubated at 30°C for 24 hours. The leaf soft rot pathogen P. carotovorum subsp. carotovorum was grown in Luria Bertani (LB) agar supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin. For long term storage, bacteria were maintained in 15% (v/ v) glycerol at −70°C.

Bacterial cell suspension and heat-treated cells

KUDC1013 was grown 24 hours on TSA plates at 30°C. Cells were scraped off the plate and suspended in a sterile saline solution (0.85% NaCl) adjusted to a final concentration of 108 CFU/ml. KUDC1013 heat-treated cells were obtained by autoclaving and viability of these heat-treated cells was checked by dilution plating of the suspension on TSA. The heat-treated cell suspension was used at the same concentration with living cells. Suspensions were subjected to ISR bioassay as described below.

Extraction and purification of LPS

Lipopolysaccharide containing cell walls were obtained using the method described by Leeman et al. (1995). Bacterial cells grown on TSA plates were suspended in phosphate buffered saline (10 mM, pH 7.2), centrifuged at 4000 g for 5 min and lyophilized. Lyophilized cells were suspended in 50 mM Tris/HCl, 2 mM EDTA buffer (pH 8.5) and sonicated six times at resonance amplitude for 15 s at 4°C. The sonicated suspension was centrifuged (600 g, 20 min) to remove intact cells and the supernatant was again centrifuged (8,000 g, 60 min) to obtain the crude LPS as a pellet. LPS was purified according to the method of Rezania et al. (2011). LPS was resuspended in PBS and treated with enzymes to eliminate contaminating proteins and nucleic acids. An equal volume of hot (67–75°C) 90% phenol was added with vigorous shaking at 65–70°C for 15 min and the suspension was cooled in ice. The mixture was centrifuged at 8,500 g for 15 min. Sodium acetate at 0.5 M final concentration and 10 volumes of 95% ethanol were added to the supernatant. The samples were stored at −20°C overnight in order to precipitate the LPS and followed by centrifugation at 2,000 g, 4°C for 10 min. The pellets were resuspended in distilled water and an equal amount of chloroform was added followed by shaking in order to remove traces of phenol. The suspension was centrifuged at 2,000 g, 4°C for 10 min and the purified LPS was lyophilized and stored at 4°C.

Flagella extraction

Flagella were prepared as described by Meziane et al. (2005). Bacterial cells grown on TSA were harvested and suspended in 20 mM potassium-phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 (KP buffer) followed by centrifugation at 5,700 g, 5 min. The pellet was resuspended in KP buffer and treated in a homogenizing blender for 60 s to shear off the flagella. Intact cells and cell debris were removed by centrifugation at 23,400 g, 1 h, 4°C and flagella were collected by high speed centrifugation (60,000 g, 4 h, 4°C). The pellet was stored at −20°C.

Isolation of ISR determinant from KUDC1013 cell free supernatant

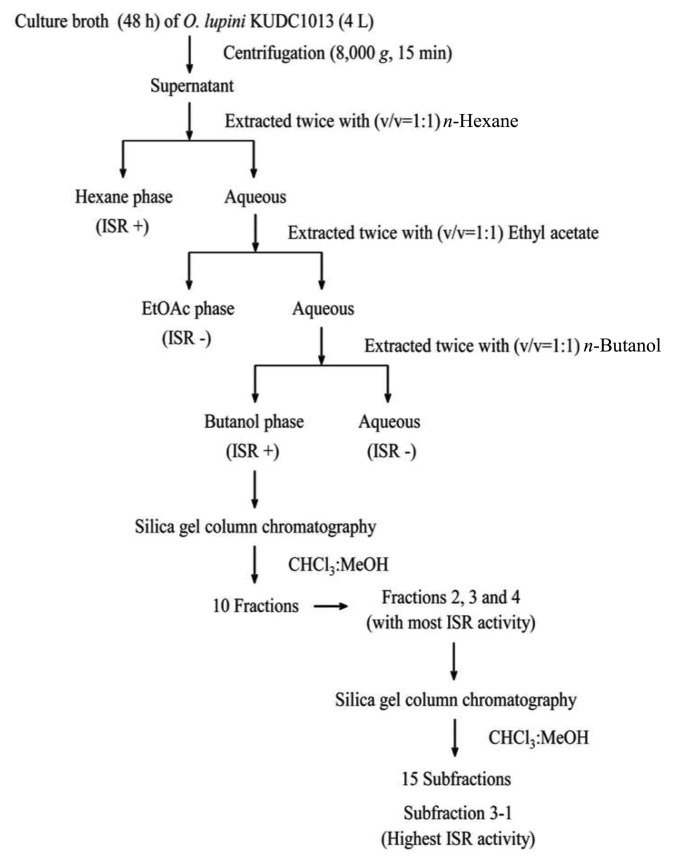

O. lupini KUDC1013 was grown in Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) on a rotary shaker (180 rpm) at 30°C for 48 h to stationary phase. Cells were eliminated by centrifugation at 8,000 g for 15 min. 300 ml from the obtained supernatant was lyophilized and the resulting powder was suspended in 30 ml sterile distilled water (SDW). Heat-treated supernatant was obtained by autoclaving. The suspensions were subjected to ISR bioassay as described below. The remaining culture filtrate was extracted twice with a double volume of n-hexane, ethyl acetate and n-butanol (Fig. 1). Extracts were evaporated to dryness in an EYELA model N-1000 rotary evaporator at 50°C. The extracts were dissolved in 10% Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO, Kanto Chem. Inc., Japan) and were subjected to ISR bioassay as described below. The extract with highest ISR activity was subjected to silica gel column chromatography. An open glass column (50 mm diameter × 820 mm long) was slurry packed with silica gel in chloroform and washed with two bed volumes of chloroform methanol. The extracts were loaded onto the column and eluted with two bed volumes of a solvent mixture of chloroform and methanol, in which the methanol concentration was increased at each elution step. Each eluate was evaporated and subjected to ISR bioassay. The fraction with the ISR activity was further processed and sub-fractions were tested for their ISR eliciting capacity. The most ISR active sub-fraction was subjected to instrumental analysis. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) investigation of the most ISR active sub-fraction was carried out with an Agilent model 7890A-5975C GC/MSD equipped with a capillary column (0.25 ID × 30 m × 0.25 μm film thickness) and electron ionization (EI) as the ion source. The carrier gas is helium and the flow rate is 1.0 ml/min. The column temperature was set at 30°C for 3 min, elevated at 50°C/min to 180°C and by 40°C/min to 200°C. The chemicals present in the sub-fraction were purchased (Sigma Aldrich, Korea) and were tested for ISR elicitation.

Fig. 1.

Extraction procedure and ISR activity of extracts from O. lupini KUDC1013. KUDC1013 was grown in Tryptic Soy Broth (4 L) for 48 h and extracted with organic solvents.

Plant material and induced systemic resistance bioassay

Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacuum) seeds were surface sterilized by soaking in 1.2% sodium hypochlorite solution for 30 min and washed extensively with SDW. Seeds were allowed to germinate on petri dishes containing half-strength Murashige and Skoog salt (MS) medium containing 1.5% sucrose and 0.8% plant agar, for 2–3 days at 25°C in the absence of light (Murashige and Skoog, 1962). Equally germinated seeds were transferred to 24-well microtitre plate (SPL, Korea), one seed on each well containing 1.5 ml of MS agar media and grown in a growth chamber at 25°C with 14 h/10 h light/dark conditions. One week after transplanting, tobacco plants were inoculated in the root part with 10 μl of different preparations tested for their ISR activity. Control plants were treated with SDW or 10% DMSO as negative controls and 0.5 mM Benzothiadiazole (BTH) as positive control. Seven days after root treatment, four leaves per tobacco seedling were dropped each with 5 μl suspensions of P. carotovorum subsp. carotovorum (108 CFU/mL). Soft rot symptom was determined by visual examination of leaves 24 h after inoculation. The disease incidence was measured by counting the number of symptomatic leaves per seedling (Ryu et al., 2004). The experiment was repeated three times, three replicates per treatment with 24 plants per replicate.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the means were separated by the least significant difference test using JMP software version 4.04 (SAS Institute, USA). The significance of the effects of the treatments was determined by Duncan’s multiple range test (p = 0.05).

Results and Discussion

O. lupini KUDC1013 was previously reported to promote the growth of tobacco under laboratory conditions and of pepper under laboratory and field conditions (Ham et al., 2009; Hahm et al., 2012). This rhizobacterium possess plant growth-promoting characteristics including the ability to solubilize phosphate, produce indole-3-acetic acid and siderophore (Ham et al., 2009). Aside from its plant growth-promoting ability, KUDC1013 has been shown to elicit ISR against several pathogens and under greenhouse and field conditions (Ham et al., 2009; Hahm et al., 2012). In this study, factors from KUDC1013 involved in ISR activity were investigated using tobacco as the model plant and P. carotovorum subsp. carotovorum as the challenging pathogen.

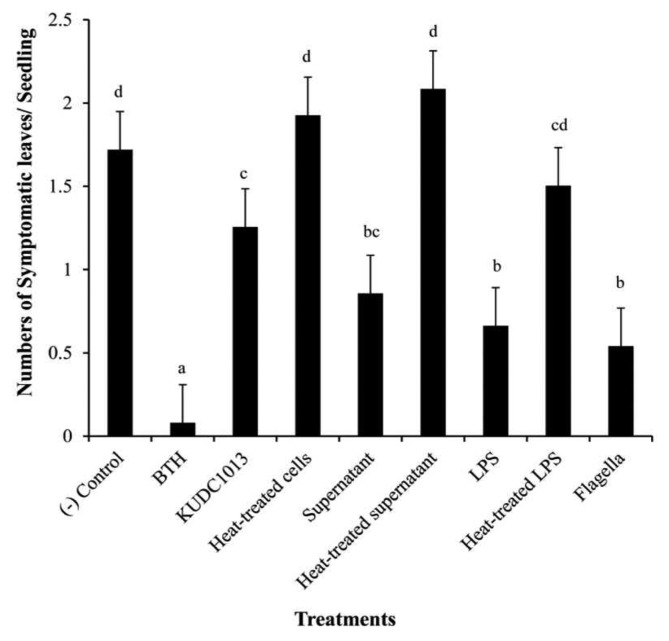

Treatments containing live KUDC1013 cells or heat-treated cells were tested for ISR activity in order to determine if there is any heat stable cell envelop or cell wall related components that play a major role in ISR elicitation. Results showed that tobacco plants treated with KUDC1013 cells have lesser symptoms compared with those treated only with sterile distilled water and heat-treated cell preparation did not provide any protection (Fig. 2). Cell wall components such as LPS and flagellin were reported to elicit ISR (Gomez-Gomez and Boller, 2002 Leeman et. al., 1995; van Peer and Schippers, 1992). When suspension containing LPS of KUDC1013 was treated in the rhizosphere of tobacco, the disease incidence was lower compared with control (Fig. 2). In certain PGPR strains, bacterial LPS present in the outer membrane of PGPR are the major determinants of ISR. LPS from Pseudomonas sp. strain WCS417r induce resistance in radish and carnation to Fusarium wilt. The heat-treated cells and purified LPS of WCS417r both triggered ISR in carnation to a level similar to that obtained by treatment with viable bacterial cells (Leeman et al., 1995; van Peer and Schippers, 1992). LPS of Rhizobium etli strain G12 induced systemic resistance of potato to infection by cyst nematode Globodera pallida. Both living and heat-killed cells of the rhizobacterium elicited protection in potato (Reitz et al., 2000). However, in this study LPS elicited ISR while heat-treated LPS did not provide any protection (Fig. 2). This suggests that LPS from KUDC1013 could be heat-labile. LPS from KUDC1013 should be further characterized and tested using mutants as it was suggested that different LPS compositions have different resistance responses to plants (Leeman et al., 2005; Whatley et al., 1980).

Fig. 2.

Resistance induced in tobacco plant by O. lupini KUDC1013 and its components against P. carotovorum subsp. carotovorum. Symptom was expressed as number of symptomatic leaves per seedling. Sterile distilled water (SDW) and 0.5 mM Benzothiadiazole (BTH) were used as negative and positive control, respectively. Vertical bars represent standard errors. Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments according to Duncan’s multiple range test at p = 0.05. The data are representative of three experiments, three replicates per treatment with 24 plants per replicate.

In addition to LPS, treatment of tobacco roots with flagella preparations of KUDC1013 significantly decreased soft rot symptoms (Fig. 2). Some PGPR mediates ISR through flagella (Gomez-Gomez and Boller, 2002). Bacterial flagellin, the principal structural component of flagella, is recognized in plants by surface receptors containing extracellular leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain FLS2 (Mendei et al., 2000). Flagellins purified from Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea, an incompatible pathogen for tobacco, induced immune responses in tobacco (Taguchi et al., 2003). Flagella preparations of KUDC1013 elicited ISR against P. carotovorum thus; it is interesting to know examine flagella lacking mutant of KUDC1013 for their ability to induce ISR and to determine activation of resistance pathways in tobacco on perception of flagellin from KUDC1013.

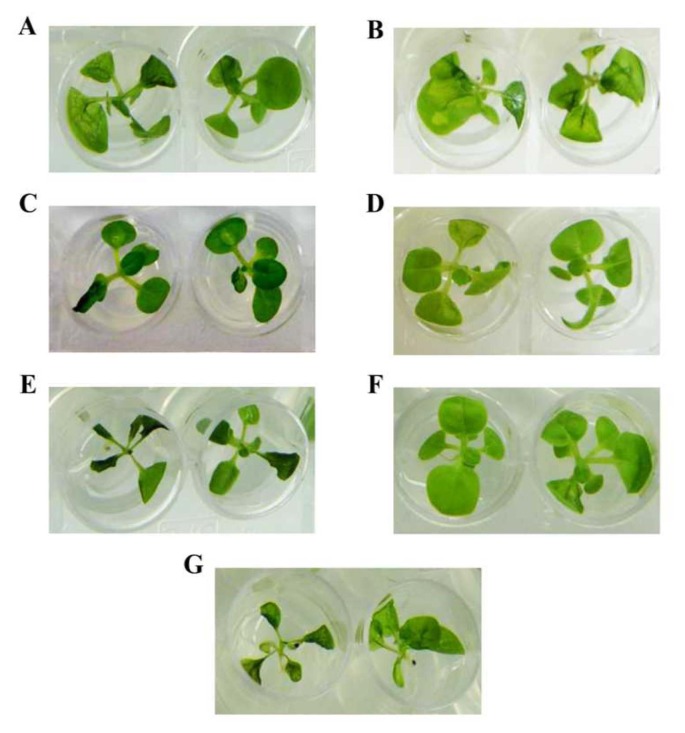

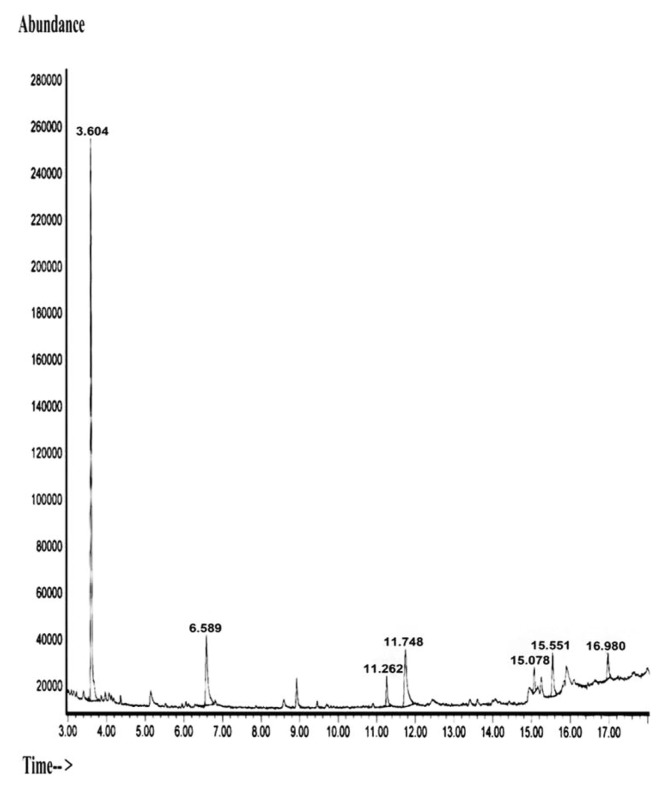

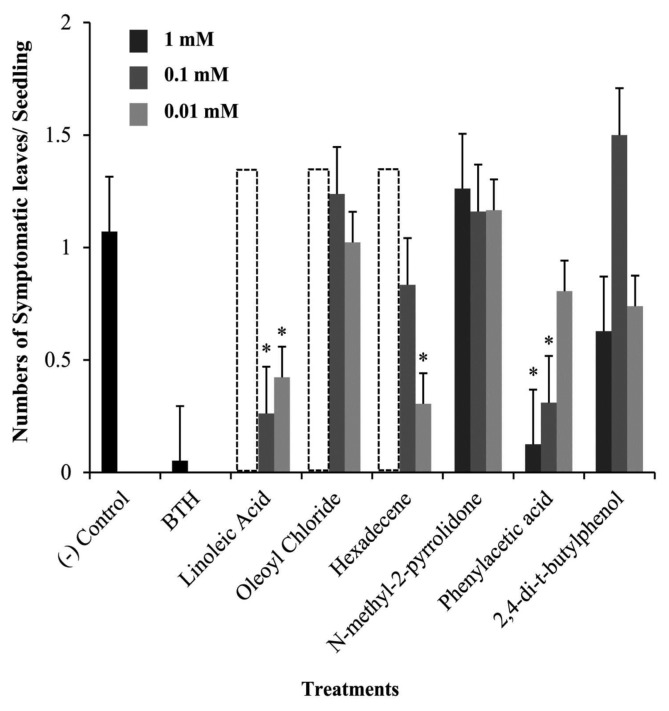

A reduction in soft rot disease symptom was observed in plants treated with the crude supernatant obtained after growth of strain KUDC1013 in TSB. Moreover, heat-treated supernatant did not elicit ISR suggesting that the ISR-related metabolite present in the supernatant could be heat labile. To further investigate the metabolites present in KUDC1013 supernatant, it was extracted by a series of organic solvents. ISR bioassay using the organic extracts and remaining aqueous suspension showed that compounds in the n-hexane and n-butanol fractions have ISR eliciting capability with n-butanol having higher protective effect while remaining aqueous suspension and ethyl acetate fractions were impaired of ISR activity (Figs. 1 and 3). The n-butanol extract was further processed through silica gel column chromatography and fractions were subjected to ISR bioassay. The most reduction in soft rot disease incidence was observed in treatment with subfraction 3-1 (Fig. 1). Gas chromatography/Mass spectrometry (GC/MS) analysis revealed that compounds were present in subfraction 3-1 namely; N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone, phenylacetic acid, 2,4-d-t-butylphenol, linoleic acid, oleoyl chloride and 1-hexadecene (Fig. 4). ISR bioassay using these compounds showed that among them, linoleic acid, 1-hexadecene and phenylacetic acid induced systemic resistance against leaf soft rot pathogen (Fig. 5).

Fig. 3.

Effect of extracts of KUDC1013 on soft rot symptoms on tobacco leaves. Roots of seedlings were inoculated with Sterile distilled water (SDW) (A), 10% Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) (B), 0.5 mM Benzothiadiazole (BTH) (C), n-Hexane (D), Ethyl acetate (E), n-Butanol (F), and Aqueous (G) extracts. SDW and 10% DMSO were used as negative controls and BTH as positive control. One week after treatment, plant leaves were challenges with soft rot pathogen, as described in Materials and Methods. Photographs were taken 24 h after inoculation with P. carotovorum. The photographs are representative of three independent experiments with at least 72 seedlings per treatment.

Fig. 4.

Chromatogram obtained in Gas Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry analysis for identification of the ISR determinant(s) of O. lupini KUDC1013 present in the ISR-active butanol subfraction 3-1.

Fig. 5.

Influence of root treatment with chemicals present in n-butanol subfraction 3-1 on the number of symptomatic leaves on tobacco after inoculation with soft rot pathogen P. carotovorum. Sterile distilled water (SDW) and 0.5 mM Benzothiadiazole (BTH) were used as negative and positive control, respectively. The highest ISR eliciting subfraction 3–1 was subjected to GC/ MS analysis and chemicals present were purchased and subjected to ISR bioassay. The data are representative of three experiments, three replicates per treatment with 24 plants per replicate. Blank bars mean plants died after treatment. Vertical bar represents standard errors. *Indicates significantly different from negative control at LSD (p = 0.05).

Phenyl acetic acid (PAA) at 1 mM and 0.1 mM induced systemic resistance of tobacco against P. carotovorum (Fig. 5). PAA is known as an auxinomimetric compound with the ability to stimulate cell enlargement similar to a plant growth promoting hormone IAA (Fries, 1977; Milborrow et al., 1975). PAA is produced by both plants (Isogai et al., 1967) and by bacteria (Hwang et al., 2001; Sarwar et al., 1995; Somers et al., 2005). PAA showed inhibitory activity against zoospore germination and hyphal growth of Phytophthora capsici (Lee et al., 2004) and antifungal activity against the dry rot causative pathogen Gibberella pulicaris, and was shown to suppress dry rot infection of wounded potatoes (Slininger et al., 2004).

Induction of systemic resistance was also observed in tobacco plants treated with 0.01 mM 1-hexadecene. Hexadecene is a hydrocarbon commonly reported in seaweeds (Zakaria et al., 2011). Hexadecene observed in the crude extract of the microalgae Spirulina platensis showed antimicrobial activity against pathogenic bacteria (Kumar et al., 2011). Also, hexadecene was isolated from the liquid culture of the biocontrol fungus Trichoderma harzianum strain FA1132 (Siddiquee et al., 2012).

Linoleic acid (LA) is a fatty acid found in many natural sources including vegetable oils from safflower, sunflower and corn oils and is produced by some bacteria (Alonso et al., 2003; Chin et al., 1992; Macouzet et al., 2009). It is considered as a biologically beneficial functional lipid because of its many nutraceutical purposes (Ogawa et al., 2005). Kabara et al. (1972) demonstrated that linoleic acid possessed biocidal effects against gram positive bacteria. In this study, treatment of tobacco roots with 1 mM LA caused death to plants while it significantly decreased the soft rot symptoms at 0.1 mM and 0.01 mM (Fig. 5). This suggests that LA, at higher concentration is toxic to tobacco and is possibly more effective in eliciting ISR at lower concentrations. Linoleic acid inhibited the mycelial growth of Alternaria solani, Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici, and F. oxysporum f. sp. cucumerinum at 2 mM and exhibited an antifungal activity against Crinipellis perniciosa at the lower level of 0.1 mM (Liu et al., 2008; Walters et al., 2004).

Some biologically active metabolites play a role as elicitors of ISR at low contration but showed antimicrobial activity at higher concentration (Rohilla et al. 2002; Tosi and Zazzerini, 2000). PAA, 1-hexadecene and LA, at concentration tested for direct antibiosis (0.01 mM–2.0 mM), did not exhibit any direct antimicrobial activity against the pathogen in vitro (data not shown). Different ISR-active compounds elicit ISR at different concentrations. The ISR-active metabolite 4-aminocarbonyl phenylacetate from Pseudomonas chlororaphis O6 applied at 68.0 mM elicited ISR activity against wildfire pathogen at a level similar to 1.0 mM salicylic acid (Park et al., 2008). The ISR effect of butyl-2-pyrrolidone-5-carboxylate (BPC) from Klebsiella oxytoca C1036 was observed at 12 mM (Park et al., 2009). In this study PAA elicited ISR at 1.0 mM and 0.1 mM, 1-hexadecene at 0.01 mM while LA elicited ISR at concentration of 0.1 and 0.01 mM (Fig. 5).

These results demonstrated the various determinants of KUDC1013 involved in ISR activity. The recognition of KUDC1013 cell wall components, LPS and flagella led to the induction of systemic resistance of tobacco against soft rot disease. Metabolites present in the culture supernatant of KUDC1013 that elicit ISR against soft rot disease were identified as PAA, 1-hexadecene and LA. Application of these compounds activated the disease resistance of tobacco against soft rot. To the author’s knowledge, this is the first report of PAA, 1-hexadecene and LA as ISR-related metabolites from KUDC1013.

The present work shows that O. lupini KUDC1013 has multiple factors involved in the induction of systemic resistance. Further studies are therefore necessary to elucidate the mode of actions and the physiological functions of KUDC1013 determinants in order to maximize their biological control potential.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (No. 2011-0011565).

References

- Alonso L, Cuesta EP, Gilliland SE. Production of free conjugated linoleic acid by Lactobacillus acidophilus and Lactobacillus casei of human intestinal origin. J Dairy Sci. 2003;86:1941–1946. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(03)73781-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babalola OO. Beneficial bacteria of agricultural importance. Biotechnol Lett. 2010;32:1559–1570. doi: 10.1007/s10529-010-0347-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron RK, Dixon R, Lamb C. Biologically induced systemic acquired resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1994;5:715–725. [Google Scholar]

- Chin SF, Liu W, Storkson JM, Ha YL, Pariza MW. Dietary sources of conjugated dienoic isomers of linoleic acid, a newly recognized class of anticarcinogens. J Food Comp Anal. 1992;5:185–197. [Google Scholar]

- Chin-A-Woeng TFC, Bloemberg GV, van der Bij AJ, van der Drift KMGM, Schripsema J, Kroon B, Scheffer RJ, Keel C, Bakker PAHM, Tichy HV, de Brujin FJ, Thomas-Oaters JE, Lugtenberg BJJ. Biocontrol by phenazine-1-carboxamide-producing Pseudomonas chlororaphis PCL1391 of tomato root rot caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. radicis-lycopersici. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1998;11:1069–77. [Google Scholar]

- Dunne C, Möenne-Loccoz Y, McCarthy J, Higgins P, Powell J, Dowling DN, O’Gara F. Combining pro-teolytic and phloroglucinol-producing bacteria for improved control of Pythium-mediated damping-off of sugar beet. Plant Pathol. 1998;47:299–307. [Google Scholar]

- Fries L. Growth regulating effects of phenylacetic acid and phydroxy-phenylacetic acid on Fucus spiralis L. (Phaecophyceae, Fucales) in axenic culture. Phycology. 1977;16:451–455. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Gomez L, Boller T. Flagellin perception: a paradigm for innate immunity. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7:251–256. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(02)02261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas D, Keel C. Regulation of antibiotic production in root-colonizing Pseudomonas spp. and relevance for biological control of plant disease. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2003;41:117–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.41.052002.095656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahm MS, Sumayo M, Hwang YJ, Jeon SA, Park SJ, Lee JY, Ahn JH, Kim BS, Ghim S-Y. Biological control and plant growth promoting capacity of rhizobacteria on pepper under greenhouse and field conditions. J Microbiol. 2012;50:380–385. doi: 10.1007/s12275-012-1477-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham MS, Park YM, Sung HR, Sumayo M, Ryu CM, Park SH, Ghim S-Y. Characterization of rhizo-bacteria isolated from family Solanaceae plants in Dokdo island. Kor J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;37:110–117. [Google Scholar]

- Han SH, Anderson JA, Yang KW, Cho BH, Kim KY, Lee MC, Kim YH, Kim YC. Multiple determinants influence root colonization and induction of induced systemic resistance by Pseudomonas chlororaphis O6. Mol Plant Pathol. 2006;7:463–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2006.00352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang BK, Lim SW, Kim BS, Lee JY, Moon SS. Isolation and in vivo and in vitro antifungal activity of phenylacetic acid and sodium phenylacetate from Streptomyces humidus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:3739–3745. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.8.3739-3745.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isogai Y, Okamoto T, Koizumi T. Isolation of indole-3-acetamide, 2-phenylacetamide and indole-3-carboxaldehyde from etiolated seedlings of Phaseolus. Chem Pharm Bull Tokyo. 1967;15:151–158. doi: 10.1248/cpb.11.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jetiyanon K, Kloepper JW. Mixtures of plant-growth promoting rhizobacteria for induction of systemic resistance against multiple diseases. Biol. Control. 2002;24:285–291. [Google Scholar]

- Kamilova F, Validov S, Azarova T, Mulders I, Lugtenberg B. Enrichment for enhanced competitive plant root tip colonizers selects for a new class of biocontrol bacteria. Environ Microbiol. 2005;7:1809–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloepper JW, Tuzun S, Kuc JA. Proposed definitions related to induced disease resistance. Biocontrol Sci Tech. 1992;2:349–351. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Bhatnagar AK, Srivastava JN. Antibacterial activity of crude extracts of Spirulina platensis and its structural elucidation of bioactive compound. J Med Plants Res. 2011;5:7043–7048. [Google Scholar]

- Lee JY, Kim HS, Kim KD, Hwang BK. In vitro anti-oomycete and in vivo control efficacy of phenylacetic acid against Phytophthora capsici. Plant Pathol J. 2004;20:177–183. [Google Scholar]

- Leeman M, van Pelt JA, Den Ouden FM, Heinsbroek M, Bakker PAHM, Schippers B. Induction of systemic resistance against Fusarium wilt of radish by lipopolysaccharides of Pseudomonas fluorescens. Phytopathology. 1995;85:1021–1027. [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Weibin R, Jing L, Hua X, Jingan W, Yubao G, Jingguo W. Biological control of phytopathogenic fungi by fatty acids. Mycopathologia. 2008;166:93–102. doi: 10.1007/s11046-008-9124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugtenberg B, Kamilalova F. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2009;63:541–556. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macouzet M, Lee BH, Robert N. Production of conjugated linoleic acid by probiotic Lactobacillus acidophilus La-5. J Appl Microbiol. 2009;106:1886–1891. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meindl T, Boller T, Felix G. The bacterial elicitor flagellin activates its receptor in tomato cells according to the address-message concept. Plant Cell. 2000;12:1783–1794. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.9.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meziane H, van der Sluis I, van Loon LC, Höfte M, Bakker PAHM. Determinants of Pseudomonas putida WCS358 involved in inducing systemic resistance in plants. Mol Plant Pathol. 2005;6:177–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2005.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milborrow BV, Purse JG, Wightman F. On the auxin activity of phenylacetic acid. Ann Bot. 1975;39:1143–1146. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa J, Kishino S, Ando A, Sugimoto S, Mihara K, Shimizu S. Production of conjugated fatty acids by lactic acid bacteria. J Biosci Bioeng. 2005;100:355–364. doi: 10.1263/jbb.100.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ongena M, Jourdan E, Schäfer M, Kech C, Budzikiewicz H, Luxen A, Thonart P. Isolation of an N-alkylated benzylamine derivative from Pseudomonas putida BTP1 as elicitor of induced systemic resistance in bean. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2005;18:562–569. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-18-0562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park MR, Kim YC, Park JY, Han SH, Kim KY, Lee SW, Kim IS. Identification of an ISR-related metabolite produced by Pseudomonas chlororaphis O6 against wildfire pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci in tobacco. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;18:1659–1662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park MR, Kim YC, Lee S, Kim IS. Identification of an ISR-related metabolite produced by rhizobacterium Klebsiella oxytoca C1036 active against soft-rot disease pathogen in tobacco. Pest Manag Sci. 2009;65:1114–1117. doi: 10.1002/ps.1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitz M, Rudolph K, Schröder I, Hoffmann-Hergarten S, Hallmann J, Sikora RA. Lipopolysaccharides of Rhizobium etli strain G12 act in potato roots as an inducing agent of systemic resistance to infection by the cyst nematode Globodera pallida. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:3515–3518. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.8.3515-3518.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezania S, Amirmozaffari N, Bahman Tabarraei B, Jeddi-Tehrani M, Zarei O, Alizadeh R, Masjedian F, Amir Hassan, Zarnani AH. Extraction, purification and characterization of lipopolysaccharide from Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhi. Avicenna J Med Biotech. 2011;3:3–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohilla R, Singh US, Singh RL. Mode of action of acibenzolar-S-methyl against sheath blight of rice, caused by Rhizoctonia solani Kühn. Pest Manag Sci. 2002;58:63–69. doi: 10.1002/ps.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu CM, Farag MA, Hu CH, Reddy MS, Kloepper JW, Paré PW. Bacterial volatiles induce systemic resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2004;134:1017–1026. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.026583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu CM, Kim J, Choi O, Park SY, Park SH, Park CS. Nature of a root-associated Paenibacillys polymyxa from field-grown winter barley in Korea. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;15:984–991. [Google Scholar]

- Sarwar M, Franckenberger WT., Jr Fate of lphenylalanine in soil and its effect on plant growth. Soil Sci Soc Amer J. 1995;59:1625–1630. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiquee S, Cheond BE, Taslima K, Kausar H, Hasan MM. Separation and identification of volatile compounds from liquid cultures of Trichoderma harzianum by GC-MS using three different capillary columns. J Chromatogr Sci. 2012;50:358–367. doi: 10.1093/chromsci/bms012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slininger PJ, Burkhead KD, Schisler DA. Anti-fungal and sprout regulatory bioactivities of phenylacetic acid, indole-3-acetic acid, and tyrosol isolated from the potato dry rot suppressive bacterium Enterobacter cloacae S11:T:07. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;31:517–524. doi: 10.1007/s10295-004-0180-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somers E, Ptacek D, Gysegom P, Srinivasan M, Vanderleyden J. Azospirillum brasilense produces the auxin-like phenylacetic acid by using the key enzyme for indole-3-acetic acid biosynthesis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:1803–1810. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.4.1803-1810.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi F, Shimizu R, Nakajima R, Toyoda K, Shiraishi T, Ichinose Y. Differential effects of flagellins from Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci, tomato and glycinea on plant defense response. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2003;41:165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Tosi L, Zazzerini A. Interactions between Plasmopara helianthi, Glomus mosseae and two plant activators in sunower plants. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2000;106:735–744. [Google Scholar]

- van Loon LC, Bakker PAHM, Pieterse CMJ. Systemic resistance induced by rhizosphere bacteria. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1998;36:453–483. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.36.1.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Peer R, Schippers B. Lipopolysaccharides of plant growth promoting Pseudomonas spp. strain WCS417r induce resistance in carnation to Fusarium wilt. Neth J Pl Path. 1992;98:129–139. [Google Scholar]

- van Peer R, Niemann GJ, Schippers B. Induced resistance and phytoalexin accumulation in biological control of Fusarium wilt of carnation by Pseudomonas sp. strain WCS417r. Phytopathology. 1991;81:728–34. [Google Scholar]

- Walters D, Raynor L, Mitchell A, Walker R, Walker K. Antifungal activities of four fatty acids against plant pathogenic fungi. Mycopathologia. 2004;157:87–90. doi: 10.1023/b:myco.0000012222.68156.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei G, Kloepper JW, Tuzun S. Induction of systemic resistance of cucumber to Colletotrichum orbiculare by select strains of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria. Phytopathology. 1991;81:1508–1512. [Google Scholar]

- Whatley MH, Hunter N, Cantrell MA, Hendrick CA, Keegstra K, Sequeira L. Lipopolysaccharide composition of the wilt pathogen, Pseudomonas solanacearum: correlation with hypersensitive response in tobacco. Plant Physiol. 1980;65:557–559. doi: 10.1104/pp.65.3.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakaria NA, Ibrahim D, Fariza Shaida SF, Afifah Supardy NA. Phytochemical composition and antibacterial potential of hexane extract from Malaysian red algae, Acanthophora spicifera(Vahl) Borgesen. World Appl Sci J. 2011;15:496–501. [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel C, Robatzek S, Navarro L, Oakeley EJ, Jones JDG, Felix G, Boller T. Bacterial disease resistance in Arabidopsis through flagellin perception. Nature. 2004;428:764–767. doi: 10.1038/nature02485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]