Abstract

Background

Recent studies in various animal models have suggested that anesthetics such as propofol, when administered early in life, can lead to neurotoxicity. These studies have raised significant safety concerns regarding the use of anesthetics in the pediatric population and highlight the need for a better model by which to study anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity in humans. Human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) are capable of differentiating into any cell type and represent a promising model to study mechanisms governing anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity.

Methods

Cell death in hESC-derived neurons was assessed using TUNEL staining and microRNA (miR) expression was assessed using quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRTPCR). miR-21 was overexpressed and knocked down using a miR-21 mimic and antagomir, respectively. Sprouty 2 was knocked down using a small interfering RNA and the expression of the miR-21 targets of interest was assessed by Western blot.

Results

Propofol dose and exposure time-dependently induced significant cell death (n = 3) in the neurons and downregulated several microRNAs, including miR-21. Overexpression of miR-21 and knockdown of Sprouty 2 attenuated the increase in TUNEL-positive cells following propofol exposure. In addition, miR-21 knockdown increased the number of TUNEL-positive cells by 30% (n = 5). Finally, activated Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (STAT3) and protein kinase B (Akt) were downregulated and Sprouty 2 was upregulated following propofol exposure (n = 3).

Conclusions

These data suggest that: (1) hESC-derived neurons represent a promising in vitro human model for studying anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity, (2) propofol induces cell death in hESC-derived neurons and (3) the propofol-induced cell death may occur via a STAT3/miR-21/Sprouty2-dependent mechanism.

Introduction

It is estimated that 4 million children are administered anesthetic agents every year in the United States for imaging or surgical purposes.1 The deleterious effects of anesthetic exposure on the developing brain in animals have been well-established and several anesthetics, including propofol, have been shown to induce neuronal cell death in neonatal rat and primate models.2–5 Moreover, anesthetic exposure has been linked to learning disabilities and impaired cognitive function which has raised safety concerns regarding the use of anesthetics in children.6,7. However, the use of anesthetic agents in young children is often unavoidable. Therefore, it is critical to understand the effects of anesthetics on developing human neurons and their mechanisms of action in order to minimize any neurotoxic effects of these agents.

The mechanisms involved in developmental anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity are not well understood and until recently, much of the research in the neurodegenerative field was performed in animal models with no direct evidence available in a human model. Additionally, for ethical reasons, it is not feasible to perform these studies on young children and the only human data available comes from a limited number of epidemiological studies.8–11 Moreover, these human studies are often limited by many confounding variables and have produced widely mutable results. Therefore, the neurological effects of anesthetics on young children remain uncertain. Human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) are pluripotent cells that are derived from the inner cell mass of a human blastocyst.12 The benefit of using hESCs lies in their ability to differentiate into any cell type making them a potentially powerful model of human physiology and pathophysiology. Therefore, neurons derived from hESCs are a valuable model to directly study the effects of anesthetics on immature, human-derived neurons.

MicroRNAs (miRs) are endogenous, non-coding RNA molecules that act to regulate nearly every cellular process through inhibition of target messenger RNA expression. MicroRNAs are produced through the processing of long stem-loop transcripts by the nucleases Drosha and Dicer. The mature microRNA then combines with the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) and interacts with its target to induce gene silencing through target mRNA degradation or translational repression.13 MicroRNAs have been implicated to play important roles in many different disease processes, including neurological diseases.14–16 Neurotoxicity conferred by ethanol, cocaine, Huntington’s disease, and brain injuries have all been linked to microRNA dysregulation.17 However, the role of microRNAs in anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity has yet to be studied.

One microRNA, miR-21, has been shown to decrease apoptosis and can protect neurons from ischemic injury. Exposure of fetal cerebral cortical-derived neuroepithelial cells to ethanol was shown to suppress miR-21.18 miR-21 has been shown to decrease apoptosis in varying cell types by directly targeting and suppressing Sprouty 2 which, in turn, negatively regulates Protein Kinase B (Akt) activation.19–23 Additionally, Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (STAT3) is a known regulator of miR-21.24–28 After screening microRNAs and finding that miR-21 was downregulated following exposure to propofol, we hypothesized that the miR-21 signaling pathway (STAT3/Sprouty2/Akt) plays a role in the increased cell death observed in the hESC-derived neurons following propofol administration.

Materials and Methods

Culturing of hESCs hESCs

(H1 cell line, WiCell Research Institute Inc., Madison, WI) were cultured on a feeder layer of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) that were mitotically inactivated using mitomycin C (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) as previously described by our laboratory29,30. Briefly, culture dishes were coated with 0.1% gelatin overnight in a humidified incubator. MEFs were then plated onto the gelatin and cultured in MEF media consisting of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle media (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, Grand Island, NY) and 1% nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The MEFs were cultured overnight in a humidified, hypoxic incubator (4% O2/5% CO2, 37°C). hESCs were then plated onto the MEFs and cultured in the hypoxic incubator in hESC media containing DMEM/F12 supplemented with 20% Knockout serum (Gibco), 1% nonessential amino acids, 1 mM L-glutamine, 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen), 4 ng/mL human recombinant basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF, Invitrogen) and 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich). The media was changed every day and the cells were passaged mechanically every 5 days. hESCs at passage 55–70 were used for these studies.

Differentiation of Neurons from hESCs

To generate neurons from the hESCs, the cells were taken through a 4-step differentiation protocol as previously described.29,30 The timeline for the differentiation protocol is shown in Figure 1A and was performed as follows: (1) Embryoid Body (EB) Culture. hESCs cultured on MEFs were dissociated for 40 minutes using the protease Dispase (1.5 unit/mL, Invitrogen). The hESCs were then spun down, resuspended in hESC medium without bFGF and cultured in ultra-low attachment 6-well plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) in a normoxic incubator (20% O2/5% CO2, 37°C). The media was changed daily and spherical EBs were present 24 hours after dispase digestion. Five days after digestion, EBs were switched to neural induction media containing DMEM/F12 supplemented with 1% N2 (Invitrogen), 1% nonessential amino acids, 1 mg/mL heparin (Sigma) and 5 ng/mL bFGF. The media was changed daily for an additional 4 days. (2) Rosette Formation. On day 9, the EBs were plated to matrigel-coated 35-mm dishes and cultured in neural induction media. The media was changed every other day and rosette-like structures were present within 5 days of the EBs plating down. (3) Expansion of Neural Stem Cells (NSCs). Two days after the rosette morphology was clearly visible, the rosettes were manually separated from the surrounding cells using a 5 mL serological pipette. The rosette cells were then transferred to matrigel-coated culture dishes and cultured in neural expansion media containing DMEM/F12 supplemented with 2% B27 without vitamin A, 1% N2 (Invitrogen), 1% nonessential amino acids, 20 ng/mL bFGF and 1 mg/mL heparin. The media was changed every other day and the NSCs were passaged enzymatically every 5 days with Accutase (Innovative Cell Technologies, San Diego, CA). (4) Neuron Differentiation. NSCs were cultured in 60-mm matrigel-coated dishes (500,000 cells/dish) for 2 weeks in neuron differentiation media containing neurobasal media (Gibco) supplemented with 2% B27, 0.1 μM cyclic adenosine monophosphate, 100 ng/mL ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 ng/mL brain-derived neurotrophic factor, 10 ng/mL glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor, and 10 ng/mL insulin-like growth factor 1 (PeproTech Inc., Rocky Hill, NJ). The media was changed every other day and after 2 weeks of culture, the cells displayed clear neuronal morphology and were used for the studies.

Fig. 1.

Differentiation and characterization of human embryonic stem cell (hESC)-derived neurons. (A) A 4-step differentiation protocol was used to generate neurons from the hESCs which included embryoid body culture, rosette formation, expansion of neural stem cells and neuron differentiation. (B) The differentiated cells displayed a morphology characteristic of neurons with small cell bodies and projections (a) and stained positive for the neuron-specific markers, microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2, b, green) and β-tubulin III (c, green). The blue dots are the cell nuclei stained with Hoechst 33342. (C) The neurons also stained positive for doublecortin (a, green), a marker of immature neurons and again for β-tubulin III (b, red). The doublecortin staining co-localized with the β-tubulin III staining (c, orange). (D) Finally, synapse-like structures were visible in the differentiated neurons (indicated by the yellow arrow) upon electron microscopy imaging.

Immunofluorescence Staining, Confocal Microscopy and Electron Microscopy

2-week-old hESC-derived neurons cultured on matrigel-coated, glass coverslips were fixed for 30 minutes at room temperature in 1% paraformaldehyde. Cells were then washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) 3 times followed by a 15 minute incubation in 0.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS. The cells were then washed with PBS and blocked for 20 minutes at room temperature with 10% donkey serum. Following the blocking, the cells were incubated with the primary antibodies [microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2), β-tubulin III or doublecortin (Abcam, Cambridge, MA)] for 1 hour in a humidified, 37°C incubator. The cells were washed 3 times with PBS and incubated for 45 minutes at 37°C with Alexa Fluor 488 or 594 donkey anti-mouse or rabbit immunoglobulin G (Invitrogen) secondary antibodies. The cells were washed with PBS and the cell nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen). Finally, the coverslips were mounted onto glass slides and imaged using a laser-scanning confocal microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U, Nikon Inc., Melville, NY). To assess the differentiation efficiency, the ratio of MAP2-positive cells over the total cell nuclei was calculated. Electron microscopy imaging was performed as previously described.29,30

Propofol Exposure

While assessment of brain concentrations of propofol in humans during the induction and maintenance of anesthesia is difficult, studies have shown and estimated that it ranges from 4–20 μg/mL.31–34 The dose of propofol used clinically in children varies widely but typically ranges from about 1–10 μg/mL (blood concentration) with higher doses used for induction of anesthesia and lower doses used for maintenance.35–37 In addition, cell culture and whole animal studies have shown that propofol can induce toxicity at high doses or prolonged exposure times after a single exposure.5,31,38,39 Thus, 2-week-old hESC-derived neurons were treated with 0, 5, 10 and 20 μg/mL of research grade propofol (0–112 μM, Sigma-Aldrich) or equal volume of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma-Aldrich) as the vehicle control in 60 mm culture dishes (500,000 cells/dish) or 12 mm glass coverslips (100,000 cells/coverslip). A stock solution (40 mg/mL) of propofol was prepared in DMSO and serial dilutions to the desired doses were prepared from the stock. Cells were exposed to propofol for 6 hours either one time or three times (once per day for three consecutive days). In the multiple exposure groups, following the 6 hours of propofol exposure each day, the cells were rinsed with PBS and placed in fresh media overnight. Following exposure to the propofol, the cells were lysed for microRNA analysis and Western blot or fixed for immunostaining and TUNEL staining. The mechanistic experiments in this study were performed in hESC-derived neurons following a single exposure to 6 hours of 20 μg/mL propofol.

TUNEL Staining

Apoptosis, and to some extent necrosis was analyzed using a cell death detection kit (Roche Applied Bio Sciences, Indianapolis, IN) based on terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate in situ nick end labeling (TUNEL) following instructions provided by the manufacturer. TUNEL identifies single and double stranded DNA breaks by labeling the free 3′-OH termini with modified nucleotides in an enzymatic reaction with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT). Cells were cultured on glass coverslips in 24 well plates and exposed for 6 hours to 20 μg/mL propofol or DMSO. Following an 18 hour washout in media, the cells were then rinsed and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde and DNA fragmentation was assessed using the polymerase TdT, which incorporates into areas of DNA breaks. Hoechst 33342 was used to stain the nuclei and the cells were imaged using the confocal microscope. Apoptosis/necrosis was quantified by determining the ratio of TUNEL-positive nuclei to total cell nuclei. To eliminate the possibility of different wells of the 24-well plate receiving preferential conditions and affecting the outcome of the studies, the coverslips were assigned randomly to the experimental groups across the entire plate. In addition, to minimize the introduction of bias into the cell imaging and counting studies, the experimenter was blinded to the group being analyzed.

Total RNA Extraction

Following exposure to propofol or DMSO, total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Briefly, the cells were rinsed with PBS and lysed with QIAzol lysis reagent (Qiagen). Chloroform was added and the lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was transferred to a new Eppendorf tube. RNA was precipitated from the upper phase with 100% ethanol and collected using the RNeasy spin columns (Qiagen). Samples were rinsed twice with buffer RPE and the RNA was eluted from the column by adding 30 μL of RNase-free water (Qiagen). The quantity and quality of the RNA was assessed using an Epoch nanodrop spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments Inc., Winooski, VT). Each RNA sample was then diluted to 100 ng/μL in RNase-free water.

cDNA Preparation and MicroRNA analysis by Quantitative Reverse Transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR)

The RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using the miScript II RT kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, a mixture containing 1 μg of RNA, 10x miScript nucleics mix, RNase-free water, reverse transcriptase mix and 5x HiSpec buffer (Qiagen) was prepared. The RT reaction mixture had a final volume of 20 μL and was incubated at 37°C for 1 hour and 95°C for 5 minutes to stop the reaction. The RT product was diluted in 200 μL of RNase-free water to give a final RNA concentration of 4.5 ng/μL. MicroRNA expression levels were assessed using qRT-PCR. To screen for potential microRNAs contributing to the propofol-induced neurotoxicity, we used human miFinder miRNA PCR arrays (Qiagen). These arrays allow for rapid screening of 84 of the most abundantly expressed microRNAs as characterized in miRBase*. For these arrays, a master mix (25 μL/well) containing the template cDNA (4.5 ng/well), universal primer, RNase-free water and miScript SYBR Green (Qiagen) was prepared according to the manufacturer’s directions. The primers for each of the 84 microRNAs to be analyzed come lyophilized in the 96-well plates of the arrays. To confirm the array results for the expression of miR-21, a validation assay was performed in which the 3 cDNA samples used for the arrays were each run in triplicate on the same PCR run. To prepare the samples for the triplicate assays, a similar mastermix to that used for the arrays was prepared with the addition of the primers (miR-21 and the housekeeping gene, Rnu-6). The PCR was run using a BioRad iCycler for 15 minutes at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of a 3-step denaturation (15 seconds at 94°C), annealing (30 seconds at 55°C) and extension (301 seconds at 70°C). Reverse transcriptase and melt curve controls were run to ensure primer specificity and sample purity, respectively.

cDNA Preparation and mRNA analysis by Quantitative Reverse Transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Following total RNA extraction, cDNA was prepared using an RT2 First Strand Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 500 ng of RNA was combined with the genomic DNA elimination buffer and water and incubated for 5 minutes at 42°C to purify the RNA samples. The samples were then placed on ice for 1 minute. A mixture of 5x buffer BC3, RT mix, water and an external control was prepared and combined with the genomic DNA elimination mix. The samples were then incubated for 15 minutes at 42°C and the reaction was stopped by incubating the samples at 95°C for 5 minutes. The cDNA was then diluted in 91 μL of RNase-free water and combined with RT2 SYBR Green ROX FAST Mastermix, primers (Sprouty 2 or the housekeeping gene, B2M) and water (Qiagen). The samples were loaded into the 96-well plates (25 μL/well) and the PCR was run using the BioRad iCycler Real-Time PCR detection system for 10 minutes at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of a denaturation step (15 seconds at 95°C) and a combined annealing/extension step (30 seconds at 60°C). The Ct values of the mRNAs in each sample were collected and the expression data was normalized to the housekeeping gene, B2M. Melt curve controls were also run.

miR-21 Overexpression and Knockdown

In order to manipulate the level of miR-21, 2 week old hESC-derived neurons were transfected in 6-well plates with 25 nM locked nucleic acid (LNA) anti-miR-21 (Exiqon, Vedbaek, Denmark) or 1 nM miR-21 mimic (pre-miR-21) (Qiagen) to knockdown miR-21 or increase miR-21 abundance, respectively using lipofectamine (Invitrogen). These concentrations were chosen based upon dose studies implicating the specified concentrations as sufficient to increase abundance or knockdown miR-21 in our cells. Scrambled LNA anti-miR control (Exiqon) and pre-miR precursor negative control (Qiagen) were used as controls. Twenty-four hours after transfection, a subset of cells was used to confirm miR-21 overexpression and knockdown in the neurons by qRT-PCR. Following confirmation of overexpression/knockdown of miR-21, the remaining cells were exposed to 20 μg/mL propofol for 6 hours. The effect of miR-21 overexpression and knockdown on propofol-induced neurotoxicity in the hESC-derived neurons was analyzed by TUNEL staining. To eliminate possible bias, the wells were assigned randomly to the various experimental and control conditions.

Sprouty 2 Knockdown

To knockdown Sprouty 2 in the hESC-derived neurons, the cells were transfected in 6-well plates with 20 nM Sprouty 2 siRNA or scramble control siRNA (Qiagen) following instructions provided by the manufacturer. To eliminate any possible bias introduced by well position in each plate, the wells were assigned randomly to the various experimental groups. Briefly, a mix of opti-MEM and siRNA was prepared and 12 μL of HiPerFect Transfection Reagent (Qiagen) was added to the mixture. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes. Fresh culture media was added to each well and the siRNA mixture was added dropwise to the appropriate wells. The cells were then incubated at 37°C for 48 hours. These doses and times produced the largest knockdown as implicated by dose and time studies performed in these cells (data not shown). Following the transfection period, a subset of cells was used to confirm the Sprouty 2 knockdown by qRT-PCR. The remaining cells were exposed for 6 hours to 20 μg/mL propofol or DMSO. The effect of Sprouty 2 knockdown on propofol-induced toxicity was assessed by TUNEL staining.

Western Blot

Following exposure to propofol or DMSO (control), the cells were rinsed with PBS and were lysed and sonicated in RIPA lysis buffer (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) containing phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics). Lysates were centrifuged at 10,000×g for 10 min at 4°C. Pellets were discarded and the total protein concentration of the supernatants was determined using a DC Protein Assay Reagents Package kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The samples were boiled for 5 min at 97°C. 25 μg of protein was loaded per lane for SDS-PAGE gel separation and then transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were blocked with Blocking Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3tyr705), STAT3, Sprouty 2, Akt, phosphorylated Akt (pAktser473), and tubulin (Cell Signaling). The membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Cell Signaling) for 1 hour at room temperature and labeled proteins were detected with chemiluminescence detection reagent (Cell Signaling) and obtained on X-ray film. Optical densities were quantified using ImageJ software and the data was reported as % of control.

Statistical Analysis

Results were obtained from at least 3 independent neuronal differentiations. Values were reported as means ± SD with normal distributions. Statistical analysis was performed using the Student’s t-test when comparing 2 groups and one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Tukey correction for multiple testing when comparing more than 2 groups. All statistical analysis was performed using the SigmaStat 3.5 software (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA). P-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Characterization of hESC-Derived Neurons

To generate neurons from the hESCs, the cells were taken through a 4-step differentiation protocol as outlined in Figure 1A. Differentiated neurons displayed characteristic neuronal morphology with small cell bodies and projections and over time, the neurons formed extensive, interconnected networks (fig. 1B–a). The cells displayed a very distinct morphology at each stage of the differentiation protocol. The hESCs formed tight colonies while cultured on the feeder layer of MEFs while the EBs formed three-dimensional aggregates when suspended in culture. At the neural rosette stage, the NSCs formed into tightly packed, circular arrangements bordered closely by various additional cell types. Once mechanically separated from the surrounding cells and digested, the NSCs spread on the matrigel-coated dishes and extensively proliferated.

Following 14 days in neuronal differentiation media, the cells displayed a very characteristic neuronal morphology with small cell bodies and interconnected projections (fig. 1B–a). The neurons were immunostained after 2 weeks in differentiation media and expressed the neuron-specific markers MAP2 and β-tubulin III (fig. 1B–b, c). Based upon the immunostaining, the differentiation protocol was about 90–95% efficient in the generation of neurons.

In an attempt to better gauge the maturity level of the hESC-derived neurons, the cells were also immunostained 2 weeks after the initiation of differentiation media for doublecortin, a marker of immature/migrating neurons. Based upon the results of this staining, most of the neurons in culture (90–95%) were positive for this marker of immature neurons (fig. 1C) suggesting that this is a valuable model of developing human neurons. It has been shown that the period in which developing mammalian neurons are the most vulnerable to anesthetic administration is the period of rapid synaptogenesis or the brain growth spurt.40–42 To assess the synaptogenic capacity of the 2 week old hESC-derived neurons, we utilized electron microscopy and we were able to visualize synapse-like structures as indicated by the yellow arrow in figure 1D. It is extremely difficult to identify the exact stage in development that these cells represent. Therefore, further work will be needed to better define the maturation stage of these cells.

Propofol Induces Cell Death in hESC-Derived Neurons

TUNEL staining was used to assess cell death in hESC-derived neurons following propofol exposure by labeling breaks in the DNA. The cells were exposed one and three times to 6 hours of 5, 10 and 20 μg/mL propofol. The number of TUNEL-positive cells was significantly increased when compared to DMSO-treated cells following one exposure to 20 μg/mL propofol, but not after a single exposure to 5 μg/mL or 10 μg/mL propofol (fig. 2A–a). In the group exposed one time to 20 μg/mL propofol, 9.42% ± 1.48% of the total cells were TUNEL-positive while only 1.7% ± 0.4% of cells treated with an equal volume of the vehicle control (DMSO) were TUNEL-positive (fig. 2A–b). Following three exposures to propofol, the number of TUNEL positive cells was significantly increased in both the 10 μg/mL and 20 μg/mL propofol-treated groups, but not the 5 μg/mL treated group (fig. 2B–a). The number of TUNEL-positive cells was increased to 19.9% ± 1.1% following 3 exposures to 20 μg/mL propofol as compared to the control in which 1.52% ± 0.32% of the cells were TUNEL-positive. However, after 3 exposures to 10 μg/mL propofol, the number of TUNEL-positive cells was only slightly increased to 4.48% ± 1.15%, although this was a statistically significant difference when compared to the control-treated cells (fig. 2B–b). For all mechanistic studies, the cells were exposed 1 time to 20 μg/mL propofol for 6 hours.

Fig. 2.

Propofol dose- and exposure time-dependently increases the number of TUNEL-positive cells. (A) TUNEL staining was used to identify damaged DNA and assess cell death following a single exposure to 6 hours of various doses of propofol. Hoechst 33342 was used to stain the nuclei which are shown in blue. Most of the TUNEL-positive staining (red) was localized to the DNA stained nuclei and the number of TUNEL-positive cells observed was considerably higher in the 20 μg/mL propofol-treated cells when compared with control cells (a). The TUNEL-positive cells were counted to quantify the data and cell death was significantly increased after exposure to 20 μg/mL propofol, but not after exposure to either 5 μg/mL or 10 μg/mL propofol (b). (B) TUNEL staining was also used to assess cell death following three, six hour exposures to various doses of propofol. The number of TUNEL-positive cells appeared to be much greater in the 10 μg/mL and 20 μg/mL treated cells when compared to control (a). To quantify the results, the number of TUNEL-positive cells was manually counted and we found that cell death was significantly increased in both the 10 μg/mL and 20 μg/mL propofol-treated groups when compared to control, but not in the 5 μg/mL propfol-treated group (b). (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 vs. Respective Control, n = 3/group). TUNEL = terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate in situ nick end labeling.

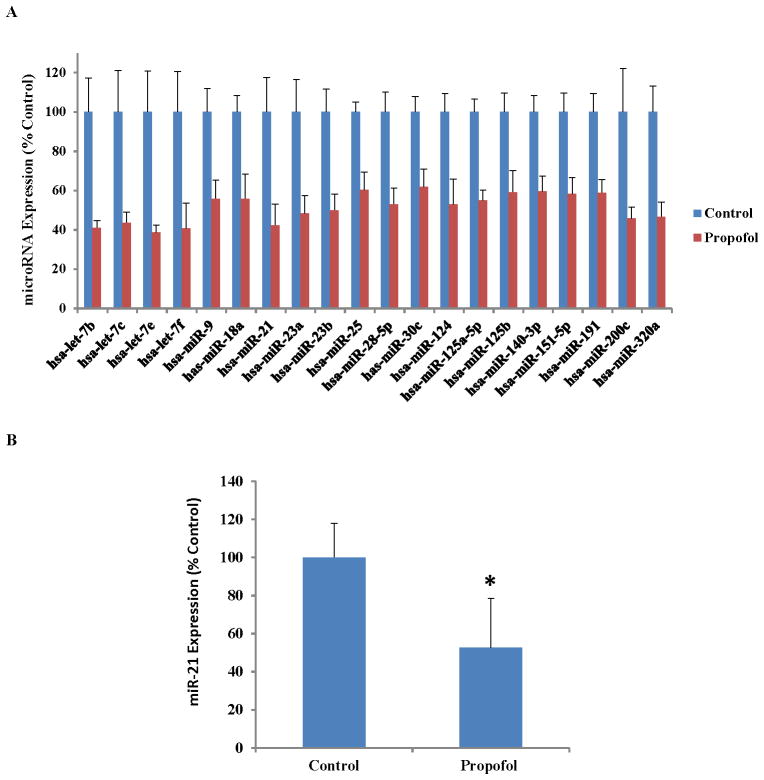

Propofol Exposure Downregulates 20 MicroRNAs

As shown in Figure 3A, with the use of the human miFinder miRNA PCR arrays, we identified 20 microRNAs that were significantly downregulated following exposure to 6 hours of 20 μg/mL propofol when compared to vehicle-treated cells (P < 0.05, n = 4/group). Of these 20 microRNAs, several were of interest to us based upon their established roles in other diseases or models. For example, the let-7 family has been shown to be highly expressed in the brain and is important in stem cell differentiation and apoptosis.43 In addition, miRs 9 and 124 have been shown to play a role in neuronal differentiation.44 However, miR-21 was of particular interest to us due to the fact that it is a well-established anti-apoptotic factor.45,46 Therefore, we hypothesized that the downregulation of miR-21 conferred by propofol exposure would play a role in the increased cell death observed in the hESC-derived neurons following propofol administration. However, the potential role of additional microRNAs in propofol-induced developmental neurotoxicity cannot be excluded. To confirm the PCR array results for the expression of miR-21, an assay was performed which again showed that miR-21 was significantly downregulated following exposure to propofol (fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Propofol exposure alters the expression of several microRNAs and the propofol-induced downregulation of microRNA-21 (miR-21) was confirmed using quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). (A) Exposure to 6 hours of 20 μg/mL propofol significantly downregulated 20 microRNAs as assessed by qRT-PCR. Of the 20 potential microRNAs of interest identified through the use of arrays, miR-21 was an intriguing target due to its well-established role as an anti-apoptotic factor. (B) The downregulation of miR-21 following exposure to propofol was validated again using qRT-PCR. This confirmation was performed to account for any variability introduced by running the samples on separate plates, as is done in the arrays. For the validation assay, the samples were all run on the same PCR plate. (*P < 0.05 vs. Control, Fig. 3A: n = 4/group, Fig. 3B: n = 5/group).

Overexpression of miR-21 Significantly Attenuates the Propofol-Induced Cell Death

To evaluate the role of miR-21 in the propofol-induced neurotoxicity observed, a mimic was used to artificially overexpress miR-21 in the hESC-derived neurons. Transfection using Lipofectamine in a cell culture system is a well-documented strategy for investigating the functions of microRNAs.47,48 Following 20 hours of transfection with the miR-21 mimic (pre-miR-21), the overexpression of miR-21 was confirmed using qRT-PCR. The levels of miR-21 were significantly higher in the cells transfected with the miR-21 mimic when compared to scramble- treated cells (fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Overexpression of microRNA-21 (miR-21) in human embryonic stem cell-derived neurons attenuates the propofol-induced cell death. (A) To overexpress miR-21, lipofectamine and a miR-21 mimic (pre-miR-21) or scrambled control (pre-scramble) microRNA (1 nM) were used. Following 20 hours of transfection with the miR-21 mimic, quantitative reverse transcription-PCR was used to confirm the overexpression of miR-21. miR-21 expression was significantly elevated following transfection with the miR-21 mimic when compared to scramble-treated cells. (B) Overexpression of miR-21 significantly attenuated the increase in TUNEL-positive cells following exposure to 6 hours of 20 μg/mL propofol. (**P < 0.01 vs. Pre-Scramble, #P < 0.01 vs. all other groups, Fig. 4A: n = 3, Fig. 4B: n = 5). TUNEL = terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate in situ nick end labeling.

TUNEL staining was used to assess cell death following exposure to propofol with and without overexpression of miR-21. Exposure to 6 hours of 20 μg/mL propofol significantly increased the number of TUNEL-positive cells (10.2% ± 1.9%) when compared to vehicle-treated cells (3.3% ± 0.4%). Overexpression of miR-21 significantly reduced the number of TUNEL-positive cells following exposure to propofol (5.3% ± 0.7%) suggesting that miR-21 is playing an important role in the propofol-induced neurotoxicity. Moreover, scramble transfection did not have an effect on the number of TUNEL-positive cells following propofol exposure (10.4% ± 1.1%) indicating that the transfection process itself is not having an effect on the cell death detected (fig. 4B).

Knockdown of miR-21 Exacerbates the Propofol-Induced Neuronal Cell Death

To further assess the role that miR-21 plays in propofol-induced neurotoxicity, a miR-21 antagomir was used to knockdown miR-21 in the hESC-derived neurons using lipofectamine. The cells were transfected for 20 hours with the anti-miR-21 or a scramble control and the knockdown was assessed by qRT-PCR. miR-21 expression was significantly reduced in the cells treated with the antagomir (0.03% ± 0.01%) when compared to the scramble-treated cells (100% ± 28.1%), confirming that the knockdown was successful (fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

MicroRNA-21 (miR-21) knockdown exacerbates the propofol-induced toxicity in human embryonic stem cell (hESC)-derived neurons. (A) hESC-derived neurons were transfected for 20 hours with a miR-21 antagomir (anti-miR-21) or scrambled control (anti-scramble) microRNA (25 nM) to knockdown miR-21. To confirm the knockdown of miR-21, quantitative reverse transcription -PCR was used. miR-21 expression was substantially reduced in the group treated with the miR-21 antagomir when compared to the scramble treated group, confirming the successful knockdown. (B) miR-21 knockdown exacerbated the increase in TUNEL-positive cells following exposure to 6 hours of 20 μg/mL propofol. (**P < 0.01 vs. Anti-Scramble, †P < 0.01 vs. all control-treated groups, #P < 0.05 vs. all other groups, Fig. 5A: n = 3, Fig. 5B: n = 5). TUNEL = terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate in situ nick end labeling.

To assess the effects of miR-21 knockdown on propofol-induced cell death, TUNEL staining was used. A single exposure to 6 hours of 20 μg/mL propofol significantly increased the number of TUNEL-positive cells (10.2% ± 1.9%) when compared to vehicle-treated, control cells (3.3% ± 0.4%). Knockdown of miR-21 exacerbated the effects of the propofol and led to an increase in the number of TUNEL-positive cells (13.0% ± 1.7%), further confirming that miR-21 is playing a role in the propofol-induced toxicity observed in the hESC-derived neurons. Scramble transfection did not have an effect on the number of TUNEL-positive cells following propofol exposure (9.3% ± 2.1%) indicating that the lipofectamine and transfection itself is not affecting the measured cell death (fig. 5B).

Propofol Induces Alterations in the Expression of Several Members of the miR-21 Pathway

There are several well-established regulators and targets of miR-21. We investigated the targets of miR-21 that have been shown to play important roles in apoptotic processes. STAT3 is a known regulator of miR-21 that has been shown to have anti-apoptotic properties.49 STAT3 is activated when phosphorylated at the tyrosine 705 position. A single exposure to 6 hours of 20 μg/mL propofol significantly decreased the expression of pSTAT3, which was consistent with the miR-21 expression data (fig. 6A–a). Sprouty 2 is known to be a direct target of miR-21. Exposure to propofol significantly increased the expression of Sprouty 2 which is consistent with the miR-21 expression data since microRNAs act as negative regulators of their target genes (fig. 6A–b). Finally, Sprouty 2 is known to act on Akt, specifically to reduce the levels of activated/phosphorylated Akt.19–21 The expression of pAkt (Ser 473) was significantly reduced following exposure to 6 hours of 20 μg/mL propofol (fig. 6A–c). Since Akt is known to play an important role in survival pathways, this represents a possible pathway by which propofol induces toxicity in the hESC-derived neurons.

Fig. 6.

Propofol exposure induces alterations in the expression of the microRNA-21 (miR-21)regulator, pSTAT3, and the direct and indirect targets of miR-21, Sprouty 2 and pAkt, respectively and manipulation of miR-21 expression alters the expression of Sprouty 2. (A) Exposure to 6 hours of 20 μg/mL propofol significantly decreased the expression of pSTAT3 (a). Propofol exposure significantly increased the expression of Sprouty 2 (b) and decreased the expression of pAkt (c). (B) Human embryonic stem cell (hESC)-derived neurons were transfected for 20 hours with a miR-21 antagomir (anti-miR-21, 25 nM) or scrambled control microRNA. Following the transfection, the expression of Sprouty 2 was assessed by Western blot. Sprouty 2 expression was significantly elevated following miR-21 knockdown (a). In addition, miR-21 abundance was artificially increased by transfecting hESC-derived neurons with 1 nM miR-21 mimic (pre-miR-21). Following the transfection, Sprouty 2 expression was again assessed by Western blot. The expression of Sprouty 2 was significantly reduced following miR-21 overexpression suggesting that Sprouty 2 is a direct target of miR-21 in our model (b). (*P < 0.05 vs. control or scramble, n = 3). pSTAT3: phosphorylated (Tyr 705) Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3. pAkt: phosphorylated (Ser 473) protein kinase B.

Manipulation of miR-21 Expression Alters the Expression of Sprouty 2

To confirm that miR-21 targets Sprouty 2 in the hESC-derived neurons, we overexpressed and knocked down miR-21 and assessed the expression of Sprouty 2 by Western blot. We found that knockdown of miR-21 significantly increased the expression of Sprouty 2 (171.6 ± 23.2) when compared to scramble-treated cells (100 ± 17.4%) (fig. 6B–a). In addition, overexpression of miR-21 led to a significant reduction in the expression of Sprouty 2 (83 ± 7.5%) when compared to scramble transfected cells (100 ± 6.6%) (fig. 6B–b). These data suggest that miR-21 is targeting Sprouty 2 in these cells.

Knockdown of Sprouty 2 Partially Attenuates the Propofol-Induced Cell Death and Alters the Expression of pAkt

To further assess the role of Sprouty 2 in the propofol-induced toxicity, we utilized a siRNA-mediated approach to knockdown Sprouty 2 in the hESC-derived neurons. The cells were transfected for 48 hours using Sprouty 2 or scramble siRNAs and transfection reagents provided by Qiagen. Following the transfection, the knockdown efficiency was assessed by qRT-PCR. Sprouty 2 expression was significantly decreased in the group treated with the Sprouty 2 siRNA (34.5 ± 2.4%) when compared to the scramble-treated group (100 ± 1.5%) (fig. 7A–a).

Fig. 7.

Sprouty 2 knockdown attenuates the propofol-induced cell death in the human embryonic stem cell (hESC)-derived neurons and increases the expression of pAkt. (A) hESC-derived neurons were transfected with a Sprouty 2 small interfering RNA (siRNA, 20 nM) or a control siRNA for 48 hours to knockdown Sprouty 2. Knockdown of Sprouty 2 was assessed by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR. Sprouty 2 expression was significantly reduced in the group treated with the Sprouty 2 siRNA when compared to scramble transfected cells confirming successful knockdown of Sprouty 2 (a). Knockdown of Sprouty 2 partially attenuated the increase in TUNEL-positive cells following exposure of hESC-derived neurons to 6 hours of 20 μg/mL propofol (b). (B) hESC-derived neurons were transfected for 48 hours with a Sprouty 2 siRNA or a control/scramble siRNA (20 nM). To confirm that Sprouty 2 was indeed acting to suppress the levels of activated Akt, we assessed the expression of pAkt and total Akt after Sprouty 2 knockdown. We found that the expression of pAkt was significantly increased in the group treated with the Sprouty 2 siRNA when compared to the scramble transfected cells. (**P < 0.01 vs. Scramble, # P < 0.01 vs. all other groups, † P < 0.01 vs. all vehicle-control treated groups and Sprouty 2 siRNA/Propofol treated group, Figs. 7A–a and B: n = 3, Fig. 7A–b: n = 5). pAkt: phosphorylated (Ser 473) protein kinase B. TUNEL = terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate in situ nick end labeling.

To evaluate the role of Sprouty 2 in the propofol-induced toxicity, 2-week-old hESC-derived neurons were transfected with Sprouty 2 or scramble siRNA for 48 hours followed by exposure to 6 hours of 20 μg/mL propofol or control. TUNEL staining was then performed on all groups. Exposure to 6 hours of propofol increased the number of TUNEL positive cells in the control group (9.3 ± 0.5%) when compared to control, vehicle-treated cells (2.4 ± 0.5%). This increase in TUNEL-positive cells was partially attenuated by Sprouty 2 knockdown (3.9 ± 0.6%), suggesting that Sprouty 2 is playing an important role in the propofol-induced toxicity. Scramble transfection did not have a significant effect on the number of TUNEL-positive cells observed in the control or propofol-treated groups indicating that the transfection process itself is not playing a role in the cell death (fig. 7A–b).

To confirm that Sprouty 2 was targeting and suppressing pAkt in our model, we transfected 2-week-old hESC-derived neurons with Sprouty 2 or scramble siRNA for 48 hours and assessed the expression of pAkt and Akt by Western blot. We found that the expression of pAkt/Akt was significantly elevated following Sprouty 2 knockdown (181.7 ± 17.8%) when compared to scramble transfected cells (100 ± 7.7%) confirming that Sprouty 2 is acting to suppress activated Akt (fig. 7B).

Discussion

In this study, we examined, for the first time, the effects of propofol on human stem cell-derived neurons and the role of the miR-21 pathway in the observed toxicity. We found that: 1) exposure to propofol induced significant cell death in the hESC-derived neurons; 2) propofol altered the expression level of several microRNAs in the neurons and downregulated miR-21; 3) Overexpression of miR-21 and knockdown of Sprouty 2 significantly attenuated the increase in TUNEL-positive cells following propofol administration while miR-21 knockdown exacerbated the effects; and 4) The expression of activated STAT3 and Akt were significantly downregulated and Sprouty 2 was upregulated following propofol exposure.

Human neurons are thought to be the most vulnerable to anesthetic administration between the third trimester in utero and the 2nd or 3rd year of life.50 The exact neuronal markers in humans during this time period are not well understood making it difficult to define this stage of development. Although it is difficult to assess the exact maturity level of the hESC-derived neurons, we have shown that most of the cells in culture are doublecortin positive, a marker of migrating/immature neurons (fig. 1C). In addition, it is the period of rapid synaptogenesis in which developing neurons are most vulnerable to anesthetic administration40–42. Thus, it is important to understand the synaptogenic capacity of the cells. We showed previously that 2-week-old hESC-derived neurons express the pre- and post-synaptic markers Synapsin I and Homer I, respectively.29,30 Additionally, we showed in this study that these cells also display synapse-like structures upon EM imaging (fig. 1D) suggesting that these cells are undergoing synaptogenesis and are likely representative of this critical stage of development. However, further electrophysiological studies will be needed to better understand the developmental stage of these cells.

Studies have shown that anesthetics, when administered early in life, can lead to learning disabilities later in life in animal models.51,52 In addition, studies performed in rodent and primate models have shown that propofol induces neuroapoptosis when administered for 5–6 hours.4,53 For example, a 5 hour exposure to an amount of propofol sufficient to maintain a surgical plane of anesthesia induced significant neuroapoptosis in both fetal and neonatal rhesus macaques.4 Additionally, exposure of cultured neonatal rat hippocampal neurons to 5 hours of 5 and 50 μM propofol was sufficient to induce cell death when compared to control treated cells.54 In 7-day-old rat pups administered 6 bolus injections, at one hour intervals of 20 mg/kg propofol; there was a significant increase in activated caspase-3 levels immediately following the exposure.55 Despite the numerous findings in animal models, the effects of propofol on a human model of neurons have yet to be studied. We found that a high, but clinically relevant dose of propofol, when administered one time for 6 hours, can induce significant cell death in 2-week-old hESC-derived neurons (fig. 2A).

The mechanisms by which anesthetics induce neurotoxicity are not well understood and although microRNAs have been shown to play crucial roles in gene regulation and disease processes, their role in anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity has yet to be examined. We found that the expression of several microRNAs, many of which have established roles in differentiation and cell death, was significantly altered by propofol administration. In particular, miR-21 was downregulated following exposure to propofol. miR-21 was of particular interest to us due to its well-established anti-apoptotic effects and its role in neuronal protection against various insults.18,46,56,57 Suppression of miR-21 in fetal rat neural progenitor cells and cultured rat cortical neurons significantly increased cell death, suggesting that miR-21 is an important anti-apoptotic factor in the brain.18,56 We found that overexpression of miR-21 could attenuate the propofol-induced cell death seen in the hESC-derived neurons (fig. 4B). Additionally, we found that miR-21 knockdown exacerbated the toxic effects of propofol (fig. 5B). These data indicate that miR-21 is playing an important role in the neuronal cell death. There were no differences in the number of TUNEL-positive cells among the vehicle-treated groups when miR-21 was overexpressed or knocked down. This is expected since miR-21 is a stress-response microRNA.58

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) is a well-established, positive regulator of miR-21.25–28 It has been shown that siRNA induced downregulation of STAT3 completely reverses the overexpression of miR-21 typically observed in prostate cancer cells.27 Moreover, downregulation of STAT3 in ER-Src cells using both an siRNA and a pharmacological inhibitor (JSI-124) induced a significant reduction in the basal expression of miR-21.28 In addition, 2 conserved STAT3 binding sites have been identified in the miR-21 enhancer sequence and several studies have shown, through the use of chromatin immunoprecipitation studies, that STAT3 directly binds to miR-21.27,59 STAT3 is activated when phosphorylated at the tyrosine 705 position. In addition, STAT3 has been shown to have anti-apoptotic effects on its own and in combination with alterations in miR-21 expression.49,60 We found that STAT3 and miR-21 were significantly downregulated following a single exposure to 20 μg/mL propofol, suggesting that this pathway is contributing to the propofol-induced cell death.

Although miR-21 has many well-established targets, we decided to focus our initial studies on miR-21 targets that had recognized roles in survival pathways. Protein kinase B (Akt) plays a crucial role in cell survival and apoptosis.61,62 miR-21 can indirectly regulate Akt through several targets, including Sprouty 2. Sprouty 2 is a direct target of miR-21 that can act to negatively regulate Akt expression.19–21 We found that Sprouty 2 expression was increased following exposure to propofol with a concomitant decrease in the expression of pAkt. To confirm that miR-21 was directly targeting Sprouty 2 in our model, we overexpressed and knocked down miR-21 and assessed the expression of Sprouty 2 by Western blot. We found that Sprouty 2 was significantly upregulated following miR-21 knockdown and significantly downregulated following miR-21 overexpression (fig. 6B). These data suggest that miR-21 is targeting Sprouty 2 in our cells and altering its expression. To further elucidate the role of Sprouty 2 in the observed toxicity, we used an siRNA-mediated approach to knockdown Sprouty 2. To assess the role of Sprouty 2 in the observed toxicity, we exposed the hESC-derived neurons to propofol following Sprouty 2 or scramble siRNA transfection. Sprouty 2 knockdown partially attenuated the increase in TUNEL-positive cells following propofol exposure suggesting an important role of Sprouty 2 in this process (fig. 7A). We believe that the partial return to control conditions following Sprouty 2 knockdown is likely due to the incomplete knockdown of Sprouty 2 in these cells. However, the role of additional miR-21 targets in the propofol-induced toxicity cannot be excluded and may also explain the lack of complete attenuation of the toxicity following Sprouty 2 knockdown. Nevertheless, our findings suggest a crucial role of the STAT3/miR-21/Sprouty 2/Akt pathway in the propofol-induced neurotoxicity observed.

One of the caveats of this study lies in the relevance of our in vitro model to an in vivo system. In the human brain, there are many different cell types including astrocytes, neurons, and various glial cells. These cells all interact and affect one another including responsiveness to agents such as propofol. Our model consists of a culture of pure neurons which may prevent us from observing the true effects of anesthetics on neurons. However, we are interested in teasing out the direct effects of propofol on neurons which would not be possible with other cell types present. A second limitation of our study is that we evaluated cell death as the final end point. However, there may be detrimental effects on the surviving neurons that could possibly influence the long-term outcome such as increased intracellular calcium levels and aberrant cell signaling.54,63 Finally, our current study focused on the role of the miR-21 pathway in the toxicity conferred by propofol exposure. Based upon our findings, it appears that miR-21 is playing a crucial role in this toxicity. However, the possible role of additional microRNAs or additional miR-21 targets in developmental anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity cannot be excluded.

In conclusion, this is the first time that a role for microRNAs in the mechanism of anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity has been established. Our data suggest that 1) hESC-derived neurons represent a promising in vitro human model for studying anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity, 2) propofol induces cell death in hESC-derived neurons that can be attenuated by overexpression of miR-21 or Sprouty 2 knockdown, and 3) propofol induces neuronal cell death possibly through the STAT3-miR-21-Sprouty 2-Akt pathway. This study has a high degree of clinical relevance as many human infants and children are exposed to propofol either alone or in combination with other anesthetic agents for imaging or surgical purposes. Additionally, the incidence of propofol abuse among pregnant women is on the rise which has the potential to affect the developing neurons of the fetus. These findings raise safety concerns regarding the use of anesthetics in children and pregnant women. The increases we observed in neuronal death following propofol exposure could possibly translate to future learning disabilities as seen in the animal studies. Finally, establishing the role of microRNAs in propofol-induced neurotoxicity could possibly pave the way for new research into possible neuroprotective strategies.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants P01GM066730 and R01HL034708 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, FP00003109 from Advancing Healthier Wisconsin Research and Education Initiative Fund, Milwaukee, WI (to Dr. Zeljko J. Bosnjak) and R01GM112696 from the NIH (to Dr. Xiaowen Bai).

The authors would like to thank Aniko Szabo, Ph.D. (Associate Professor, Division of Biostatistics, Medical College of Wisconsin) for statistical consultation and her help with statistical analysis of the data presented.

Footnotes

www.miRBase.org, Last accessed 9/1/2013

Part of this work has been presented at the American Society of Anesthesiologists meeting, San Francisco, CA, October 15, 2013 and Experimental Biology, San Diego, CA, April 29, 2014.

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Loepke AW, Soriano SG. An assessment of the effects of general anesthetics on developing brain structure and neurocognitive function. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:1681–707. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318167ad77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Hartman RE, Izumi Y, Benshoff ND, Dikranian K, Zorumski CF, Olney JW, Wozniak DF. Early exposure to common anesthetic agents causes widespread neurodegeneration in the developing rat brain and persistent learning deficits. J Neurosci. 2003;23:876–82. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00876.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slikker W, Jr, Zou X, Hotchkiss CE, Divine RL, Sadovova N, Twaddle NC, Doerge DR, Scallet AC, Patterson TA, Hanig JP, Paule MG, Wang C. Ketamine-induced neuronal cell death in the perinatal rhesus monkey. Toxicol Sci. 2007;98:145–58. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Creeley C, Dikranian K, Dissen G, Martin L, Olney J, Brambrink A. Propofol-induced apoptosis of neurones and oligodendrocytes in fetal and neonatal rhesus macaque brain. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110 (Suppl 1):i29–38. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu D, Jiang Y, Gao J, Liu B, Chen P. Repeated exposure to propofol potentiates neuroapoptosis and long-term behavioral deficits in neonatal rats. Neurosci Lett. 2013;534:41–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mellon RD, Simone AF, Rappaport BA. Use of anesthetic agents in neonates and young children. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:509–20. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000255729.96438.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalkman CJ, Peelen L, Moons KG, Veenhuizen M, Bruens M, Sinnema G, de Jong TP. Behavior and development in children and age at the time of first anesthetic exposure. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:805–12. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819c7124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCann ME. Anesthetic neurotoxicity in babies. J AAPOS. 2011;15:515–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilder RT, Flick RP, Sprung J, Katusic SK, Barbaresi WJ, Mickelson C, Gleich SJ, Schroeder DR, Weaver AL, Warner DO. Early exposure to anesthesia and learning disabilities in a population-based birth cohort. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:796–804. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000344728.34332.5d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansen TG, Pedersen JK, Henneberg SW, Pedersen DA, Murray JC, Morton NS, Christensen K. Academic performance in adolescence after inguinal hernia repair in infancy: A nationwide cohort study. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:1076–85. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31820e77a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartels M, Althoff RR, Boomsma DI. Anesthesia and cognitive performance in children: No evidence for a causal relationship. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2009;12:246–53. doi: 10.1375/twin.12.3.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coopman K. Large-scale compatible methods for the preservation of human embryonic stem cells: Current perspectives. Biotechnol Prog. 2011;27:1511–21. doi: 10.1002/btpr.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He L, Hannon GJ. MicroRNAs: Small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:522–31. doi: 10.1038/nrg1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson R, Zuccato C, Belyaev ND, Guest DJ, Cattaneo E, Buckley NJ. A microRNA-based gene dysregulation pathway in Huntington’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;29:438–45. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asikainen S, Rudgalvyte M, Heikkinen L, Louhiranta K, Lakso M, Wong G, Nass R. Global microRNA expression profiling of Caenorhabditis elegans Parkinson’s disease models. J Mol Neurosci. 2010;41:210–8. doi: 10.1007/s12031-009-9325-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hebert SS, Horre K, Nicolai L, Papadopoulou AS, Mandemakers W, Silahtaroglu AN, Kauppinen S, Delacourte A, De Strooper B. Loss of microRNA cluster miR-29a/b-1 in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease correlates with increased BACE1/beta-secretase expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:6415–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710263105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaur P, Armugam A, Jeyaseelan K. MicroRNAs in Neurotoxicity. J Toxicol. 2012;2012:870150. doi: 10.1155/2012/870150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sathyan P, Golden HB, Miranda RC. Competing interactions between micro-RNAs determine neural progenitor survival and proliferation after ethanol exposure: Evidence from an ex vivo model of the fetal cerebral cortical neuroepithelium. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8546–57. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1269-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng YH, Wu CL, Shiau AL, Lee JC, Chang JG, Lu PJ, Tung CL, Feng LY, Huang WT, Tsao CJ. MicroRNA-21-mediated regulation of Sprouty2 protein expression enhances the cytotoxic effect of 5-fluorouracil and metformin in colon cancer cells. Int J Mol Med. 2012;29:920–6. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2012.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel R, Gao M, Ahmad I, Fleming J, Singh LB, Rai TS, McKie AB, Seywright M, Barnetson RJ, Edwards J, Sansom OJ, Leung HY. Sprouty2, PTEN, and PP2A interact to regulate prostate cancer progression. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1157–75. doi: 10.1172/JCI63672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edwin F, Singh R, Endersby R, Baker SJ, Patel TB. The tumor suppressor PTEN is necessary for human Sprouty 2-mediated inhibition of cell proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4816–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508300200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sayed D, Rane S, Lypowy J, He M, Chen IY, Vashistha H, Yan L, Malhotra A, Vatner D, Abdellatif M. MicroRNA-21 targets Sprouty2 and promotes cellular outgrowths. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:3272–82. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-02-0159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Banjo T, Grajcarek J, Yoshino D, Osada H, Miyasaka KY, Kida YS, Ueki Y, Nagayama K, Kawakami K, Matsumoto T, Sato M, Ogura T. Haemodynamically dependent valvulogenesis of zebrafish heart is mediated by flow-dependent expression of miR-21. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1978. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rozovski U, Calin GA, Setoyama T, D’Abundo L, Harris DM, Li P, Liu Z, Grgurevic S, Ferrajoli A, Faderl S, Burger JA, O’Brien S, Wierda WG, Keating MJ, Estrov Z. Signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)-3 regulates microRNA gene expression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Mol Cancer. 2013;12:50. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han L, Yue X, Zhou X, Lan FM, You G, Zhang W, Zhang KL, Zhang CZ, Cheng JQ, Yu SZ, Pu PY, Jiang T, Kang CS. MicroRNA-21 expression is regulated by beta-catenin/STAT3 pathway and promotes glioma cell invasion by direct targeting RECK. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012;18:573–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2012.00344.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barnes NA, Stephenson S, Cocco M, Tooze RM, Doody GM. BLIMP-1 and STAT3 counterregulate microRNA-21 during plasma cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2012;189:253–60. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang CH, Yue J, Fan M, Pfeffer LM. IFN induces miR-21 through a signal transducer and activator of transcription 3-dependent pathway as a suppressive negative feedback on IFN-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8108–16. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iliopoulos D, Jaeger SA, Hirsch HA, Bulyk ML, Struhl K. STAT3 activation of miR-21 and miR-181b-1 via PTEN and CYLD are part of the epigenetic switch linking inflammation to cancer. Mol Cell. 2010;39:493–506. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bai X, Yan Y, Canfield S, Muravyeva MY, Kikuchi C, Zaja I, Corbett JA, Bosnjak ZJ. Ketamine Enhances Human Neural Stem Cell Proliferation and Induces Neuronal Apoptosis via Reactive Oxygen Species-Mediated Mitochondrial Pathway. Anesth Analg. 2013;116:869–80. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182860fc9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bosnjak ZJ, Yan Y, Canfield S, Muravyeva MY, Kikuchi C, Wells CW, Corbett JA, Bai X. Ketamine induces toxicity in human neurons differentiated from embryonic stem cells via mitochondrial apoptosis pathway. Curr Drug Saf. 2012;7:106–19. doi: 10.2174/157488612802715663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vutskits L, Gascon E, Tassonyi E, Kiss JZ. Clinically relevant concentrations of propofol but not midazolam alter in vitro dendritic development of isolated gamma-aminobutyric acid-positive interneurons. Anesthesiology. 2005;102:970–6. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200505000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chung HG, Myung SA, Son HS, Kim YH, Namgung J, Cho ML, Choi H, Lim CH. In vitro effect of clinical propofol concentrations on platelet aggregation. Artif Organs. 2013;37:E51–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2012.01553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ludbrook GL, Visco E, Lam AM. Propofol: Relation between brain concentrations, electroencephalogram, middle cerebral artery blood flow velocity, and cerebral oxygen extraction during induction of anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:1363–70. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200212000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Costela JL, Jimenez R, Calvo R, Suarez E, Carlos R. Serum protein binding of propofol in patients with renal failure or hepatic cirrhosis. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1996;40:741–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1996.tb04521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Viviand X, Berdugo L, De La Noe CA, Lando A, Martin C. Target concentration of propofol required to insert the laryngeal mask airway in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2003;13:217–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.01006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Varveris DA, Morton NS. Target controlled infusion of propofol for induction and maintenance of anaesthesia using the paedfusor: An open pilot study. Paediatr Anaesth. 2002;12:589–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2002.00921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hume-Smith HV, Sanatani S, Lim J, Chau A, Whyte SD. The effect of propofol concentration on dispersion of myocardial repolarization in children. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:806–10. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181815ce3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spahr-Schopfer I, Vutskits L, Toni N, Buchs PA, Parisi L, Muller D. Differential neurotoxic effects of propofol on dissociated cortical cells and organotypic hippocampal cultures. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:1408–17. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200005000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cui Y, Ling-Shan G, Yi L, Xing-Qi W, Xue-Mei Z, Xiao-Xing Y. Repeated administration of propofol upregulated the expression of c-Fos and cleaved-caspase-3 proteins in the developing mouse brain. Indian J Pharmacol. 2011;43:648–51. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.89819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jevtovic-Todorovic V. Developmental synaptogenesis and general anesthesia: A kiss of death? Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:6225–31. doi: 10.2174/138161212803832380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lunardi N, Ori C, Erisir A, Jevtovic-Todorovic V. General anesthesia causes long-lasting disturbances in the ultrastructural properties of developing synapses in young rats. Neurotox Res. 2010;17:179–88. doi: 10.1007/s12640-009-9088-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stratmann G, Sall JW, May LD, Bell JS, Magnusson KR, Rau V, Visrodia KH, Alvi RS, Ku B, Lee MT, Dai R. Isoflurane differentially affects neurogenesis and long-term neurocognitive function in 60-day-old and 7-day-old rats. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:834–48. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819c463d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roush S, Slack FJ. The let-7 family of microRNAs. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:505–16. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roese-Koerner B, Stappert L, Koch P, Brustle O, Borghese L. Pluripotent stem cell-derived somatic stem cells as tool to study the role of microRNAs in early human neural development. Curr Mol Med. 2013;13:707–22. doi: 10.2174/1566524011313050003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen Y, Liu W, Chao T, Zhang Y, Yan X, Gong Y, Qiang B, Yuan J, Sun M, Peng X. MicroRNA-21 down-regulates the expression of tumor suppressor PDCD4 in human glioblastoma cell T98G. Cancer Lett. 2008;272:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chan JA, Krichevsky AM, Kosik KS. MicroRNA-21 is an antiapoptotic factor in human glioblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6029–33. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumar B, Yadav A, Lang J, Teknos TN, Kumar P. Dysregulation of microRNA-34a expression in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma promotes tumor growth and tumor angiogenesis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wei T, Xu N, Meisgen F, Stahle M, Sonkoly E, Pivarcsi A. Interleukin-8 is regulated by miR-203 at the posttranscriptional level in primary human keratinocytes. Eur J Dermatol. 2013 doi: 10.1684/ejd.2013.1997. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shen XH, Han YJ, Zhang DX, Cui XS, Kim NH. A link between the interleukin-6/Stat3 anti-apoptotic pathway and microRNA-21 in preimplantation mouse embryos. Mol Reprod Dev. 2009;76:854–62. doi: 10.1002/mrd.21048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dobbing J, Sands J. Comparative aspects of the brain growth spurt. Early Hum Dev. 1979;3:79–83. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(79)90022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shen X, Liu Y, Xu S, Zhao Q, Guo X, Shen R, Wang F. Early life exposure to sevoflurane impairs adulthood spatial memory in the rat. Neurotoxicology. 2013;39C:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Paule MG, Li M, Allen RR, Liu F, Zou X, Hotchkiss C, Hanig JP, Patterson TA, Slikker W, Jr, Wang C. Ketamine anesthesia during the first week of life can cause long-lasting cognitive deficits in rhesus monkeys. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2011;33:220–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pearn ML, Hu Y, Niesman IR, Patel HH, Drummond JC, Roth DM, Akassoglou K, Patel PM, Head BP. Propofol neurotoxicity is mediated by p75 neurotrophin receptor activation. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:352–61. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318242a48c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kahraman S, Zup SL, McCarthy MM, Fiskum G. GABAergic mechanism of propofol toxicity in immature neurons. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2008;20:233–40. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e31817ec34d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Milanovic D, Popic J, Pesic V, Loncarevic-Vasiljkovic N, Kanazir S, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Ruzdijic S. Regional and temporal profiles of calpain and caspase-3 activities in postnatal rat brain following repeated propofol administration. Dev Neurosci. 2010;32:288–301. doi: 10.1159/000316970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Buller B, Liu X, Wang X, Zhang RL, Zhang L, Hozeska-Solgot A, Chopp M, Zhang ZG. MicroRNA-21 protects neurons from ischemic death. FEBS J. 2010;277:4299–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07818.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carletti MZ, Fiedler SD, Christenson LK. MicroRNA 21 blocks apoptosis in mouse periovulatory granulosa cells. Biol Reprod. 2010;83:286–95. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.081448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thum T, Gross C, Fiedler J, Fischer T, Kissler S, Bussen M, Galuppo P, Just S, Rottbauer W, Frantz S, Castoldi M, Soutschek J, Koteliansky V, Rosenwald A, Basson MA, Licht JD, Pena JT, Rouhanifard SH, Muckenthaler MU, Tuschl T, Martin GR, Bauersachs J, Engelhardt S. MicroRNA-21 contributes to myocardial disease by stimulating MAP kinase signalling in fibroblasts. Nature. 2008;456:980–4. doi: 10.1038/nature07511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Loffler D, Brocke-Heidrich K, Pfeifer G, Stocsits C, Hackermuller J, Kretzschmar AK, Burger R, Gramatzki M, Blumert C, Bauer K, Cvijic H, Ullmann AK, Stadler PF, Horn F. Interleukin-6 dependent survival of multiple myeloma cells involves the Stat3-mediated induction of microRNA-21 through a highly conserved enhancer. Blood. 2007;110:1330–3. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-081133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hwang JH, Kim DW, Suh JM, Kim H, Song JH, Hwang ES, Park KC, Chung HK, Kim JM, Lee TH, Yu DY, Shong M. Activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 by oncogenic RET/PTC (rearranged in transformation/papillary thyroid carcinoma) tyrosine kinase: Roles in specific gene regulation and cellular transformation. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:1155–66. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Song G, Ouyang G, Bao S. The activation of Akt/PKB signaling pathway and cell survival. J Cell Mol Med. 2005;9:59–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2005.tb00337.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brazil DP, Hemmings BA. Ten years of protein kinase B signalling: A hard Akt to follow. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:657–64. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01958-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Popic J, Pesic V, Milanovic D, Todorovic S, Kanazir S, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Ruzdijic S. Propofol-induced changes in neurotrophic signaling in the developing nervous system in vivo. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]