Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate outer retinal structural abnormalities in patients with visual deficits following closed globe blunt ocular trauma (cgBOT).

Methods

Nine subjects with visual complaints following cgBOT were examined between 1 month post-trauma and 6 years post-trauma. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) was used to assess outer retinal architecture, while adaptive optics scanning light ophthalmoscopy (AOSLO) was used to analyze photoreceptor mosaic integrity.

Results

Visual deficits ranged from central scotomas to decreased visual acuity. SD-OCT defects included focal foveal photoreceptor lesions, variable attenuation of the interdigitation zone, and mottling of the outer segment band, with one subject having normal outer retinal structure. AOSLO revealed disruption of the photoreceptor mosaic in all subjects, variably manifesting as foveal focal discontinuities, perifoveal hyporeflective cones, and paracentral regions of selective cone loss.

Conclusions

We observe persistent outer retinal disruption in subjects with visual complaints following cgBOT, albeit to a variable degree. AOSLO imaging allows assessment of photoreceptor structure at a level of detail not resolvable using SD-OCT or other current clinical imaging tools. Multimodal imaging appears useful for revealing the cause of visual complaints in patients following cgBOT. Future studies are needed to better understand how photoreceptor structure changes longitudinally in response to various trauma.

Keywords: Acute Macular Neuroretinopathy, Adaptive Optics, Commotio Retinae, Cones, En Face Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography, Ocular Trauma, Outer Retinal Architecture, Photoreceptors, Retinal Imaging, Traumatic Maculopathy

Introduction

While posterior segment manifestations of closed globe blunt ocular trauma (cgBOT) are variable, commotio retina (also known as “Berlin’s edema”1) is a frequent observation following cgBOT.2 Commotio retinae is characterized by a transient opacification or whitening of the retina, and studies using animal models have linked this opacity to a disruption of the photoreceptor cells.3,4 The degree of structural recovery is of interest in this condition, as it may be useful in predicting subsequent functional recovery. However recent studies using optical coherence tomography (OCT) have reached variable conclusions.

One of the more common changes reported on OCT is an increase in reflectivity/intensity of the hyperreflective band attributed to the inner segment/outer segment (IS/OS) junction, also referred to as the inner segment ellipsoid zone (ISe, or EZ),5–11 however loss or attenuation of this band has also been reported.5,9,10,12 The appearance of this band has been reported to return to normal,6,9,11 though others have reported variable recovery that is correlated to the region of the initial disruption.5,10 These latter results are consistent with the original findings of Sipperley et al., who hypothesized that the resultant visual loss in commotio retinae may be determined by the amount of photoreceptor damage occurring during the initial trauma.3 It has not been possible to test this hypothesis directly with OCT, thus the impact of cgBOT on photoreceptor structure remains unclear.

The ambiguity of current OCT results may be due in part to the resolution of commercial OCT systems. Despite having excellent axial resolution, these systems lack the ability to resolve individual photoreceptors. By correcting for the eye’s monochromatic aberrations, adaptive optics enables direct visualization of the photoreceptor mosaic with cellular resolution.13,14 In a growing number of cases, adaptive optics imaging has been shown to reveal subtle photoreceptor abnormalities that evade detection on clinical exam and/or OCT.15–18 Here we used adaptive optics scanning light ophthalmoscopy (AOSLO) to image patients with various clinical presentations of cgBOT to directly examine the relationship between photoreceptor integrity and the appearance of the outer retinal bands on OCT. Such studies may provide the foundation for the development of more accurate prognostic indicators regarding recovery of visual function in cgBOT.

Methods

Human Subjects

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary (NYEEI) and the Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW). Patients with visual complaints following cgBOT were recruited and informed consent was obtained from all subjects after explanation of the nature and possible consequences of the study. Axial length was measured using an IOL Master (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc., Dublin, CA) for calibration of the lateral scale of all retinal images. Prior to retinal imaging, eyes were dilated and accommodation was suspended using one drop each of phenylephrine hydrochloride (2.5%) and tropicamide (1%).

Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography (SD-OCT)

High-density 5-line raster scans and volumetric scans of the macula and optic nerve were obtained with a Cirrus HD-OCT (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc., Dublin, CA). Volumes were nominally 6 x 6 mm and consisted of 128 B-scans (512 A-scans/B-scan). Volume scans were examined for disruptions of the outer retinal layers to identify possible regions of interest to be imaged using AOSLO. Additional high-resolution scans of the macula were obtained using Bioptigen SD-OCT (Bioptigen, Inc., Durham, NC). Dense volumetric scans (1000 A-scans/B-scan, 250 B-scans/volume) subtending nominally either 6 x 6 mm or 7 x 7 mm were acquired to facilitate more precise inspection of retinal morphology. High-resolution line scans (1000 A-scans/B-scan; 100 repeated B-scans) were acquired through the foveal center. Up to 40 B-scans from these 100-scan sequences were registered and averaged to increase the signal to noise ratio as previously described.19 For one subject (RR_0045, Case 8), only Spectralis (Heidelberg Engineering Inc., Heidelberg, Germany) images were available (volume and high-resolution line scans).

Naming of the outer hyperreflective bands is based on the recent work of Spaide & Curcio.20,21 The innermost hyperreflective band is invariantly attributed to the external limiting membrane (ELM). The second hyperreflective band is referred to here as the ellipsoid portion of the inner segment, or ellipsoid zone (EZ). The third hyperreflective band is attributed to the interdigitation between outer segments and the underlying RPE contact cylinder, thus affording the name interdigitation zone (IZ). The fourth band is attributed to the apical portion of the RPE and so is named the RPE/Bruch’s membrane complex (RPE/BrM). Importantly, the distance between IZ and RPE/BrM is not the thickness of the RPE cell, but rather provides a convenient way to communicate the presence of multiple bands associated with the RPE. In some cases, we are able to delineate the RPE and BrM as separate peaks.

Outer nuclear layer (ONL) thickness was measured using previously described manual segmentation of the high-resolution horizontal line scans.22–24 We define the ONL thickness as the distance between the posterior boundary of the outer plexiform layer (OPL) and the ELM; while this technically includes the Henle Fiber Layer, 25 we will refer to this layer as the ONL, as the same segmentation was used to generate the previously published normative database from our lab. This normative data was comprised from 93 controls (42 male, 51 female), with an average age of 25.7 ± 8.2 years (range, 11 to 40 years).23 Finally, longitudinal reflectivity profiles (LRPs) were generated as previously described to examine the integrity of the outer hyperreflective bands.24,26,27

Using custom designed software (Java; Oracle, Redwood City, CA), we derived en face summed-volume-projection images from the Bioptigen SD-OCT volumes for two subjects as follows. The macular volume was exported from the machine and a custom contour was fit to the EZ band for each B-scan in the volume. The boundaries of the custom contour were placed at the hyporeflective region on either side of the EZ. For each B-scan, the number of points and the axial position of the points comprising the contour varied, depending on the morphology of the EZ. Then, for each B-scan, the pixels within the contour were averaged, resulting in a one-dimensional array of gray-scale values for that respective B-scan. The final en face, two-dimensional image was created by combining the one-dimensional arrays from each B-scan in the volume. The area of the lesion in the en face image was measured using previously described manually-guided segmentation software.28 This area represented the extent of the EZ band disruption.

Adaptive Optics Retinal Imaging

Images of the central photoreceptor mosaic were obtained with 1 of 2 previously described AOSLO systems.13,29–31 The systems are housed at the Medical College of Wisconsin and the New York Eye & Ear Infirmary, and are based on the same optical design. A 796 nm superluminescent diode was used for reflectance retinal imaging, with two fields of view used to acquire videos subtending either 1 x 1° or 1.75 x 1.75°. Foveal and parafoveal images were acquired by instructing the patient to fixate on one of the corners of the raster scan square, while perifoveal images were acquired using an internal fixation target. Individual image sequences containing between 100–200 frames, were then processed and averaged as outlined previously.32 These processed images were then stitched together and manually blended using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA) to generate the final montage for visualization. Montages were manually registered to clinical images as described previously.16,33 In the three montages with clearly demarcated focal lesions, the area of the lesion was measured using the same software utilized for the en face SD-OCT images.28

Cone density was measured using a previously described semi-automated algorithm,34 at select retinal locations for a subset of subjects. Central cone density is highly variable across normal individuals, so we largely focused on intra-retinal comparisons to describe the disruptions in the cone mosaic. To put our density values in context, we rely on a series of previously published histology35 and adaptive optics16,29,34,36,37 imaging studies.

Results

Nine symptomatic patients were recruited for imaging. Subject demographics and causes of trauma are listed in Table 1. The age of subjects ranged from 16 to 46 years (mean 30). Time between ocular trauma and imaging ranged from 1 month to 6 years. Visual acuity at time of imaging ranged from 20/20 to 4/200 with all but 2 subjects better than or equal to 20/30. Commotio retinae was documented in seven cases (6 macular, 1 peripheral) for which the results of any acute ophthalmic care sought was available. Subject KS_0931 (case 7) was a 20-year U.S. military veteran who sustained cgBOT during combat, and medical records of acute care were unavailable. Subject RR_0045 (case 8) presented for initial ophthalmic evaluation 6 years post trauma.

Table 1.

Subject Demographics and Causes of Trauma

| Case | Patient | Age/Gender | Cause of Trauma | Chief Complaint | Visual Acuity (OD, OS) | Time from Trauma to Imaging | Eye Imaged |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SR_0821 | 30/M | Motor vehicle collision, with airbag | Relative scotoma, OS | 20/20, 20/20 | 19 m | OS |

| 2 | TC_10006 | 31/F | Motor vehicle collision, with airbag | Relative scotoma, OU | 20/20, 20/20 | 5 m | OS |

| 3 | WW_0920 | 16/F | Motor vehicle collision, ejected from vehicle | Decreased vision, OS | 20/30, 4/200 | 5 m | OS |

| 4 | DW_0665 | 23/M | Assault-fist | Decreased vision, OD | 20/100†, 20/20 | 7 m | OD |

| 5 | RS_0785 | 40/M | Assault-pool cue | Blurry vision, OD | 20/30, 20/20 | 1 m | OD |

| 6 | WW_0923 | 20/M | Motor vehicle collision, with airbag | Blurry vision, OS | 20/20, 20/25 | 7 m | OS |

| 7 | KS_0931 | 46/M | Blast-related combat ocular trauma | Relative scotoma, OU | 20/30, 20/30 | 3 y | OD |

| 8 | RR_0045 | 51/M | Motor vehicle collision, without airbag | Relative scotoma, OS | 20/20, 20/20 | 6 y | OS |

| 9 | SH_0874 | 34/M | Motor vehicle collision, without airbag | Metamorphopsia, OD | 20/30†, 20/20 | 14 m | OD |

Pinhole

OS, left eye; OD, right eye; OU, both eyes

Case 1-SR_0821

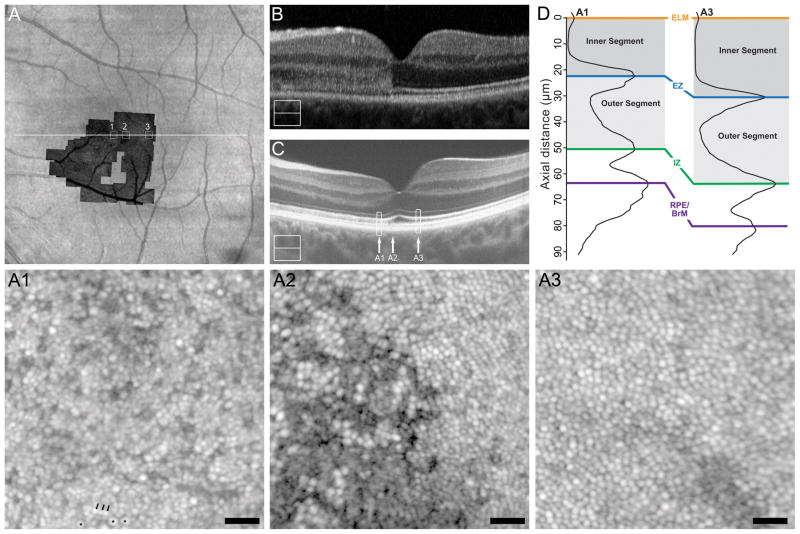

Subject SR_0821 (30-year-old male) presented to the ophthalmology clinic 4 days after cgBOT secondary to a motor vehicle collision with airbag deployment. His chief complaint at that time was a small relative scotoma superior to fixation in his left eye, and fundus examination revealed commotio retinae involving the macula. At 4 days-post-trauma, SD-OCT showed hyperreflectivity of the ONL with obscuration of the ELM, EZ, and IZ bands nasal to the fovea and infrared reflectance showed a circular hyporeflective lesion corresponding to the outer retinal hyperreflectivity seen on SD-OCT (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which shows clinical imaging results for SR_0821). By 10 months-post-trauma, visual acuity was 20/20, though the superior scotoma persisted. SD-OCT at this time showed resolution of the outer retinal hyperreflectivity with improved distinction of outer retinal bands and apparent thinning of the ONL, while the lesion on infrared reflectance was reduced (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which shows clinical imaging results for SR_0821). At 16 months-post-trauma, visual acuity remained 20/20 and the nasal hyporeflective lesion on infrared was barely visible (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which shows clinical imaging results for SR_0821). Significant thinning of the ONL nasal to the fovea was seen on SD-OCT (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 2, which shows ONL thickness in a subset of our patients compared to normal controls). At 18 months-post-trauma, research imaging was performed (Figure 1). High-resolution SD-OCT showed resolution of the ONL hyperreflectance with intact ELM, EZ, and IZ layers (Figure 1C), though residual hyperreflectivity within the outer segment layer (the normally hyporeflective band between the EZ and IZ bands) can be seen nasal to the fovea (A1). As shown in Figure 1D, LRP analysis confirms this outer segment hyperreflectivity as a reduced contrast of the EZ and IZ bands relative to that at the eccentricity-matched temporal location (A3). In addition, LRP analysis demonstrated thinning of the inner segment and outer segment layers nasal to the fovea (Figure 1D).

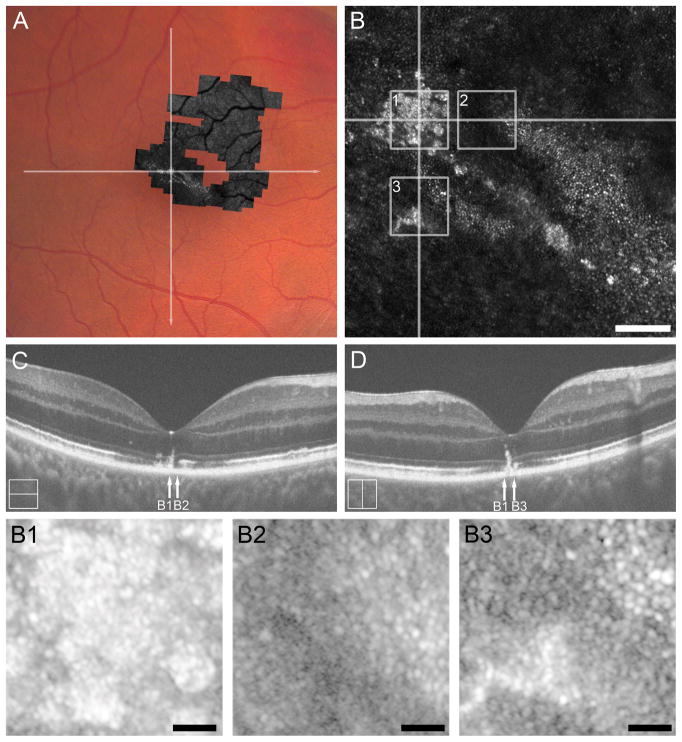

Figure 1.

Case 1, SR_0821. Trauma-induced hyperreflectivity of the outer retinal bands on SD-OCT resolves acutely and leaves behind thinning of the ONL and photoreceptor inner segment, and subtle mottling photoreceptor outer segment correlating to photoreceptor mosaic disruption on AOSLO. (A) Full extent of AOSLO montage overlaid onto an infrared image of the left eye, with the white arrow indicating the position of SD-OCT line scans (B, C), and numbered white boxes indicating the position of the AOSLO insets (A1 to A3). At day 4 post-trauma (B), SD-OCT showed a diffuse hyperreflectivity of the nasal outer retina spanning from the IZ to the OPL. SD-OCT at 18 months (C) shows resolution of this hyperreflectivity leaving a thinned ONL and visible external limiting membrane. Vertical arrows mark the locations of the three AOSLO insets (A1 to A3), while the rectangles mark locations of the LRPs shown in panel D. Compared to an eccentricity matched temporal location (A3), we see nasal (A1) thinning of the photoreceptor inner segment (72.28%) and mottled hyperreflectivity and thinning of the photoreceptor outer segment (84.54%) corresponding the disrupted photoreceptor mosaic in A1. AOSLO inset A1 shows hyporeflective cones (three exemplars marked with an asterisk near the bottom of the image) with intervening normal appearance of rods (three exemplars marked with an arrow near the bottom of the image). AOSLO inset A2 reveals a focal disruption of the cone mosaic with surrounding points of clustered hyporeflective cones which underlie a subtle focal point of hyporeflectivity of the IZ on SD-OCT (arrow A2 in panel C). The temporal location (eccentricity matched to A1) shows a contiguous cone mosaic (A3) corresponding to normal appearing outer retina on SD-OCT (arrow A3 in panel C). Scale bars = 20 μm.

AOSLO imaging revealed a disrupted photoreceptor mosaic throughout the region of inner segment and outer segment thinning nasal to the fovea (Figure 1, A1), characterized by dramatically reduced cone density (5,289 cones/mm2) and expanded rod visualization, as has been reported previously in acute macular neuroretinopathy.16 For reference, the average (± standard deviation) normal cone density at this retinal eccentricity is 43,582 ± 6,521 cones/mm2.23 AOSLO imaging near the foveal center revealed focal discontinuities of the cone mosaic (Figure 1, A2), despite qualitatively normal appearance of the outer retina on SD-OCT. AOSLO imaging at a temporal location that was eccentricity-matched to A1 (Figure 1, A3) revealed a contiguous cone mosaic of normal density (49,256 cones/mm2), consistent with the normal-appearing outer retinal architecture on SD-OCT (Figure 1C) and normal ONL thickness at this location (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 2, which shows ONL thickness in a subset of our patients compared to normal controls).

Case 2- TC_10006

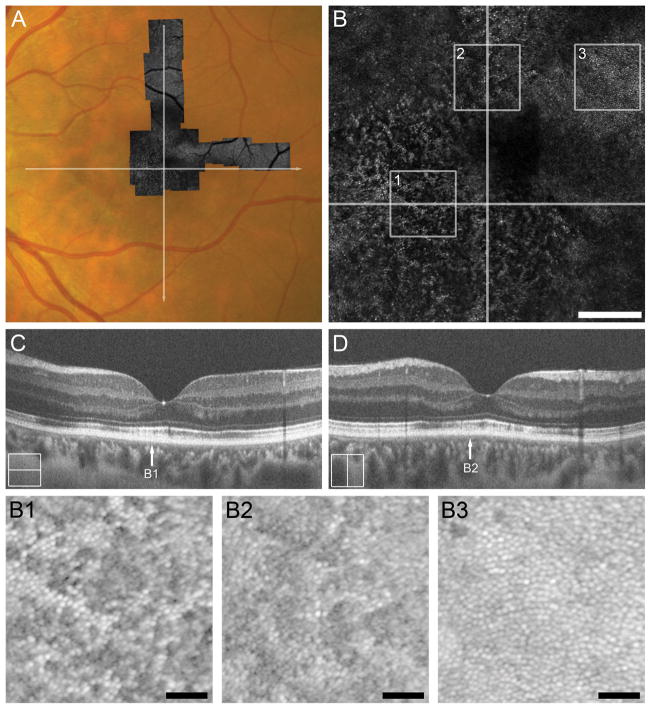

Subject TC_10006 (31-year-old female) was an unrestrained driver in a motor vehicle collision with airbag deployment and brief loss of consciousness. The subject presented for ophthalmic evaluation 19 days-post-trauma with a chief complaint of bilateral paracentral relative scotomas, left worse than right, that she noticed starting post-trauma day 1. At this time, the 24-2 Humphrey visual field (HVF) revealed dense paracentral scotomas in both eyes. Infrared reflectance showed circular hyporeflective lesion spanning the macula, corresponding to ONL thinning and disruption of the EZ and IZ bands on SD-OCT (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 3, which shows clinical imaging results for TC_10006). At day 131 post-trauma, ONL thinning persisted and the IZ and EZ bands showed mottled reflectivity (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 3, which shows clinical imaging results for TC_10006). Research imaging was performed 5 months post trauma (Figure 2), and visual acuity was 20/20 OU at this time. SD-OCT showed diffuse disruption of the EZ and IZ bands throughout the macula, including focal regions of absent IZ reflectance, and a small lamellar disruption of the EZ and IZ near temporal to the foveal center (Figure 2C & D). Thinning of the ONL throughout the macula was also documented (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 2, which shows ONL thickness in a subset of our patients compared to normal controls). AOSLO showed diffuse disruption of the cone mosaic throughout the foveal region, as seen by the dramatic reduction of normally-reflecting cones (Figure 2, B1 and B2), though patches of contiguous mosaic of normal density were also seen within this region (Figure 2, B3).

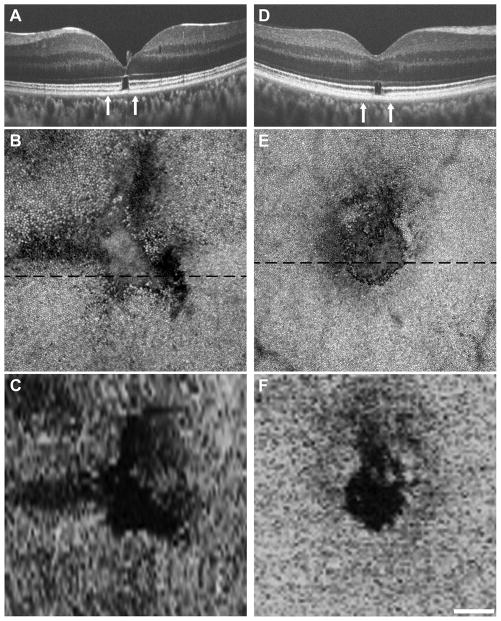

Figure 2.

Case 2, TC_10006. Trauma-induced diffuse disruption of the EZ and IZ bands and ONL thinning throughout the macula and on SD-OCT corresponds to the level of photoreceptor disruption on AOSLO 5 months after cgBOT. A. Full extent of AOSLO montage overlaid onto a color fundus photograph of the left eye with white arrows indicating the position of SD-OCT line scans (C, D). Central portion of AOSLO montage (B) showing widespread disruption of the foveal and perifoveal photoreceptor mosaic. Numbered white boxes indicating the position of the AOSLO insets (B1 to B3), and white lines again indicate the position of SD-OCT line scans (C, D). Scale bar = 200 μm. AOSLO insets, B1 and B2, taken from ~1–1.5° eccentricity show a disrupted cone mosaic of reduced density (18,281 cones/mm2 and 17,812 cones/mm2, respectively). Normal cone density for this location is 43,582 ± 6,521cones/mm2.23 The hyporeflective cones correspond to a region of IZ band disruption on SD-OCT (arrows B1 and B2 in panels C and D, respectively). AOSLO inset B3 shows a perifoveal (~2° eccentricity) contiguous cone mosaic of normal density (27,500 cones/mm2). Normal cone density for this location is 25,721 ± 3,506 cones/mm2.23 Although not captured with the SD-OCT line scans shown here, B3 corresponds to normal outer retinal lamination seen on volumetric SD-OCT through the macula. Scale bars in AOSLO insets B1–B3 = 40 μm.

Case 3-WW_0920

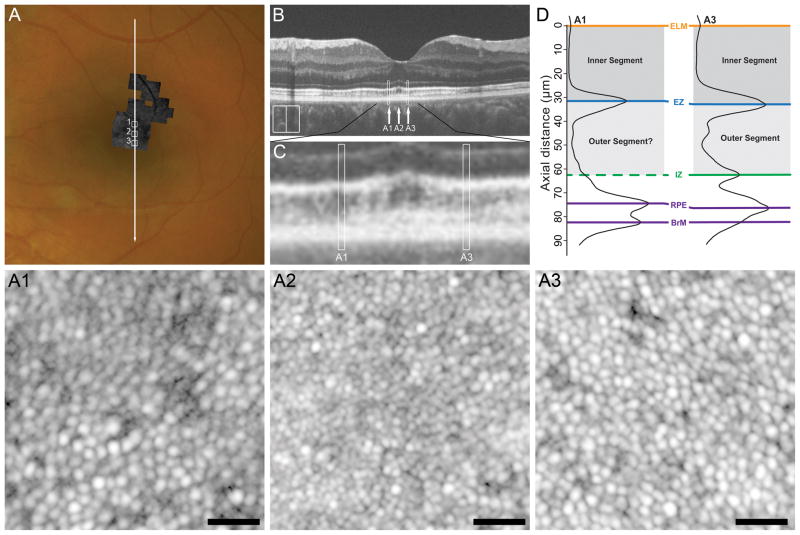

Subject WW_0920 (16-year-old female) sustained cgBOT secondary to a single vehicle rollover in which she was ejected from the vehicle. She sustained fractures of the left forearm and cervical spine. Ophthalmology was consulted on post-trauma day 1, where fundus exam revealed commotio retinae of the posterior pole, preretinal hemorrhages over the superior and inferior temporal arcades in the left eye, and visual acuity of 8/200 OS. At 11 week follow-up, commotio retinae had resolved and pre-retinal hemorrhage was decolorized. At this time macular atrophy and decreased foveal reflex was noted. Research imaging was performed at 5 months-post-trauma (Figure 3), where visual acuity was 4/200. Variable thinning of the ONL temporal to the fovea was also documented (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 2, which shows ONL thickness in a subset of our patients compared to normal controls). In addition, the macular volume scans from the Cirrus HD-OCT showed significant thinning of the ganglion cell layer (data not shown). As with TC_10006, SD-OCT showed diffuse disruption of the EZ and IZ bands throughout the macula, including focal regions of absent IZ reflectance. (Figure 3B & 3C) This is clearly seeing using the LRP analysis comparing two eccentricity-matched locations on opposite sides of the fovea (Figure 3D). Superiorly, there is an absence of a hyperreflective IZ band, however AOSLO imaging at this location (~0.8°) shows an intact cone mosaic (Figure 3, A1). AOSLO imaging at an eccentricity-matched inferior location showed an intact cone mosaic as well (Figure 3, A3), though the density was slightly higher than the superior location (49,917 cones/mm2 versus 34,050 cones/mm2). Expected cone density at this retinal eccentricity is about 49,394 ± 7,940 cones/mm2.23 Analysis of AOSLO images ~0.4° nasal to the foveal center (Figure 3, A2) yielded a cone density of 86,612 cones/mm2, consistent with normative values (78,234 ± 9,566 cones/mm2 ).38

Figure 3.

Case 3, WW_0920. Attenuation of outer retinal bands with focal regions of absent IZ band on SD-OCT corresponds to the level of photoreceptor disruption on AOSLO. (A) Full extent of AOSLO montage overlaid onto color fundus photograph of the left eye with the white arrow indicating position of the SD-OCT line scan (B) and numbered white boxes indicating the position of the AOSLO insets (A1 to A3). At 5 months-post-trauma, high-resolution SD-OCT reveals variable attenuation of the IZ band (B). This is more easily seen in the SD-OCT inset in panel C, where white boxes mark locations analyzed with LRPs in panel D. Comparison of the LRPs (D) demonstrates the absence of IZ band reflectance superiorly (A1) as compared to an eccentricity matched location inferiorly (A3) despite relative preservation of outer retinal thickness. AOSLO inset A1 shows a cone mosaic of reduced density (34,050 cones/mm2) with a central region of poorly distinguishable cone boundaries corresponding to a disrupted IZ band reflectance on SD-OCT (region A1 in B and C). AOSLO inset A3 shows an eccentricity-matched inferior location with more clearly-resolved cones and a slightly increased cone density (49,917 cones/mm2), though both locations were within the normative range for this eccentricity. AOSLO inset A2 shows a contiguous cone mosaic of normal density (82,645 cones/mm2), corresponding to a location of normal outer retinal structure on SD-OCT (arrow A2 in panel B and C). Scale bars = 20 μm.

Case 4-DW_0665

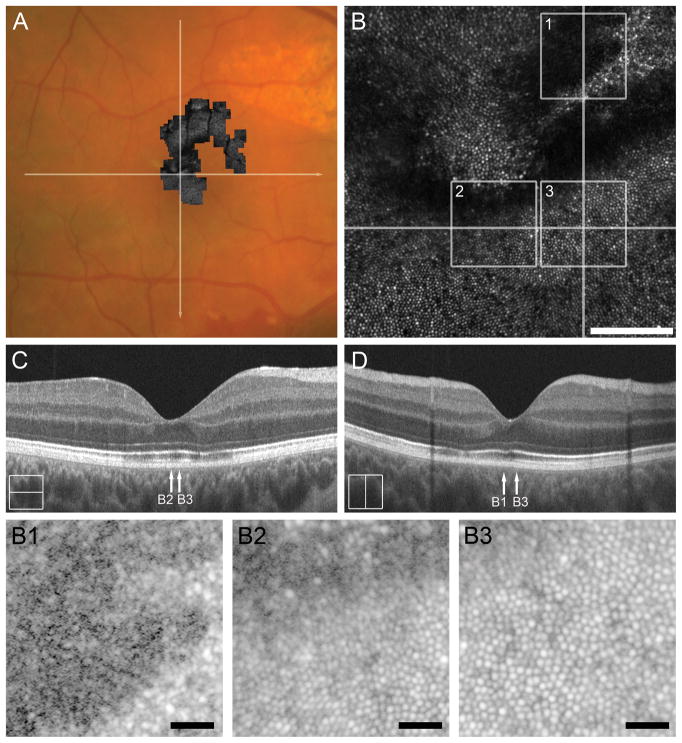

Subject DW_0665 (23-year-old male) sustained ocular damage secondary to an assault with a fist to an unprotected right eye. Initial visit on day 1 showed commotio retinae of the macula and along the inferotemporal arcade in addition to hyphema and orbital floor fractures. At follow-up on day 16, the patient complained of a central metamorphopsia and global decrease in vision OD; visual acuity at this time was 20/200 OD. Fundus exam revealed diffuse chorioretinal atrophy along the superotemporal arcade and retinal hemorrhage near the ora serrata, superiorly. SD-OCT at this time revealed extensive outer retinal attenuation within the macula (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 4, which shows clinical imaging results for DW_0665). On day 19, he underwent laser retinopexy for traumatic retinal dialysis superiorly. SD-OCT on day 100 (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 4, which shows clinical imaging results for DW_0665) showed slight resolution of EZ band attenuation with persistent disruption of the IZ band. At 5 months-post-trauma scleral buckle with cryopexy was performed for an inferior retinal detachment. At 6 months-post-trauma, visual acuity with pinhole was 20/100 and fundus exam was notable for extrafoveal choroidal ruptures concentric to the optic disc, chorioretinal atrophy supranasal to the fovea, and irregularities in macular reflex. Research imaging was conducted 7 months-post-trauma (Figure 4). SD-OCT showed diffuse disruption of the EZ and IZ bands parafoveally (Figure 4C & 4D). AOSLO imaging of the photoreceptor mosaic revealed disruption of the cone mosaic superiorly (Figure 4B), with clearly demarcated borders between normal and abnormal mosaic (Figure 4, B1–B3).

Figure 4.

Case 4, DW_0665. Reflectivity of the IZ band on SD-OCT correlates to degree of photoreceptor mosaic disruption 7 months after cgBOT. A. Color fundus photograph of the right eye showing the full extent of AOSLO montage with white arrows indicating the location of the SD-OCT scans in C and D. The central portion of the AOSLO montage (B) shows disruption of the foveal and perifoveal photoreceptor mosaic, with sharp boundaries between normal and abnormal cone mosaic. Numbered white boxes indicating the position of the AOSLO insets (B1 to B3), and white lines again indicate the position of SD-OCT line scans (C, D). Scale bar = 100 μm. AOSLO insets B1 and B2 show disruptions in the cone mosaic that correspond to the locations of an attenuated IZ band (arrow B1 and B2 in C and D). AOSLO inset B3 shows a normal contiguous cone mosaic corresponding to a location of normal retinal lamination (arrow B3 in C and D). Scale bars in AOSLO insets B1–B3 = 20 μm.

Case 5-RS_0785

Subject RS_0785 (40-year-old male) was admitted to the emergency department after sustaining a direct blow to an unprotected right orbit with a pool cue. Visual acuity at initial assessment on day 1 post-trauma was 20/200 OD. At this time fundus exam revealed commotio retinae of the macula with peripapillary subretinal hemorrhages from 9 o’clock to 5 o’clock around the optic disc, in addition to hyphema and a right upper lid laceration. At 9 days-post-trauma, color fundus photos showed resolution of commotio retinae and a decolorization of peripapillary sub retinal hemorrhage. SD-OCT at this time showed attenuation/absence of the EZ and IZ throughout the macula corresponding to a hyporeflective lesion revealed on infrared (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 5, which shows clinical imaging results for RS_0785). At 48 days-post-trauma, visual acuity had improved to 20/30 OD. Funduscopic exam revealed pigment mottling within the fovea, choroidal rupture superior to the optic disc, and partial resolution of peripapillary subretinal hemorrhages. SD-OCT on day 48, showed a decrease in EZ disruption throughout the macula with relatively persistent IZ band disruption (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 5, which shows clinical imaging results for RS_0785). Research imaging was done 6 weeks post trauma (Figure 5). Visual acuity was 20/30 in the affected eye. SD-OCT (Figure 5C and D) showed; attenuation of the EZ band and intermittent absence of the IZ band within the macula. Corresponding to the pigment mottling seen fundoscopically on day 48, SD-OCT revealed focal hyperreflective structures extending from the RPE into the ONL at foveal center (arrow B1 in Figure 5C and D). AOSLO showed diffuse disruption of the foveal and perifoveal photoreceptor mosaic (Figure 5B), with a large hyperreflective structure at foveal center (Figure 5B1), a focal disruption of the foveal cone mosaic (Figure 5B2), and patches of hyporeflective cone-like structures scattered throughout the macula (Figure 5B3).

Figure 5.

Case 5, RS_0785. Absence of the IZ on SD-OCT correlates to a discontiguous cone mosaic on AOSLO 6 weeks after cgBOT. The full extent of the AOSLO montage is overlaid onto a color fundus photograph (A) of the right eye with white arrows indicating the location of SD-OCT scans in (C and D). The central portion of the AOSLO montage (B) shows diffuse disruption of the foveal and perifoveal photoreceptor mosaic. Numbered white boxes indicating the position of the AOSLO insets (B1 to B3), and white lines again indicate the position of SD-OCT line scans (C, D). Scale bar = 100 μm. AOSLO inset B2 shows a focal discontinuity of the cone mosaic, corresponding to the absence of IZ band reflectivity on SD-OCT (arrow 2 in C). AOSLO insets B1 and B3 illustrate hyperreflective structures spanning the outer retina (arrows B1 and B3 in D), with adjacent scattered cone-like structures. Scale bars in AOSLO insets B1–B3 = 20 μm.

Case 6-WW_0923

Subject WW_0923 (20-year-old male) was an unrestrained driver in a motor vehicle collision in which airbags were deployed. He presented on post trauma day 2 with a chief complaint of decreased vision OS, with visual acuity of count fingers at 5 feet. Fundus exam revealed commotio retinae and RPE changes within the macula and extensive pre-, intra-, and subretinal hemorrhage throughout the posterior pole. SD-OCT 18 days-post-trauma showed a discontinuity of the EZ and IZ within the fovea and a hyperreflective structure at foveal center (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 6, which shows findings on clinical SD-OCT). At 1 month-post-trauma, laser retinopexy was performed for a collection of 3 peripheral retinal holes due to contusion necrosis. Research imaging was performed 7 months-post-trauma; visual acuity at this time was 20/25. SD-OCT showed a focal defect at foveal center, best characterized as an outer lamellar defect that included the EZ and IZ bands (Figure 6A). Despite the focal nature of the cone disruption, we also found significant ONL thinning at the fovea in this subject (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 2, which shows ONL thickness in a subset of our patients compared to normal controls). AOSLO imaging showed a large triangular-shaped disruption of the photoreceptor mosaic (Figure 6B). The AOSLO lesion measured 0.075 mm2, while the lesion measured from the en face SD-OCT image (Figure 6C) measured 0.070 mm2, demonstrating good correspondence between the two modalities.

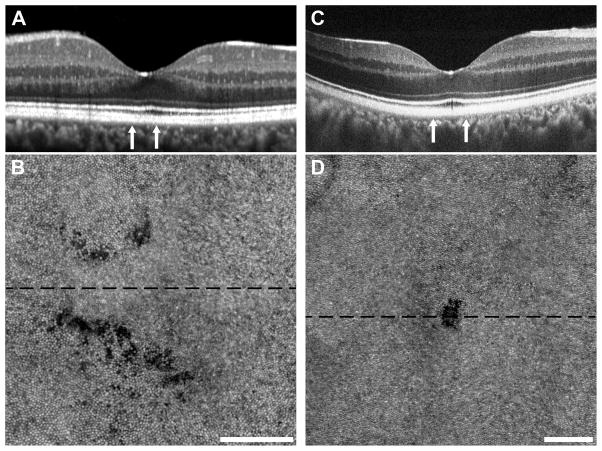

Figure 6.

Correlating focal disruption of the foveal cone mosaic with SD-OCT and AOSLO. Subjects WW_0923, Case 6 (A-C) and KS_0931, Case 7 (D-F) both showed similar presentation on research imaging, despite variable initial clinical presentation. Focal disruptions were seen on SD-OCT (A, D), best characterized as an outer lamellar defect that included the EZ and IZ bands. Vertical arrows indicate the area subtended by the AOSLO montages (B, E). The AOSLO images are displayed on a logarithmic scale and each shows a distinct hyporeflective lesion. In the retinal areas immediately adjacent to the focal lesion, the cone mosaic was contiguous and of normal density, highlighting the truly focal nature of these defects. The dashed black line on each AOSLO image indicates the location of the corresponding SD-OCT image. SD-OCT en face images of the EZ band integrity (C, F) show good agreement in the size and shape of the lesion as assessed with the 2 different imaging modalities. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Case 7-KS_0931

Subject KS_0931 (46-year-old male) is a 20-year U.S. military veteran who sustained multiple concussive blast-related injuries over his last 2 years of duty in Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom, though we were unable to obtain medical records detailing his injuries and initial clinical presentation. He presented to the study complaining of relative scotomas at the center of fixation in both eyes; visual acuity was 20/30 OU. SD-OCT showed an outer lamellar defect that included the EZ and IZ bands in both eyes (Right eye shown in Figure 6D). AOSLO imaging showed a large circular-shaped disruption of the photoreceptor mosaic (Figure 6E). The AOSLO lesion measured 0.028 mm2, while the lesion measured from the en face SD-OCT image (Figure 6F) measured 0.023 mm2, again demonstrating good correspondence between the two modalities.

Case 8-RR_0045

Subject RR_0045 (51-year-old male) was an unrestrained driver in a motor vehicle collision in which the subject’s head struck the steering wheel. He presented for ophthalmic evaluation for the first time 6 years post trauma with a chief complaint of a relative central scotoma in his left eye that he had been experiencing since the motor vehicle collision. He denied ever experiencing pain or flashes of light and reported having no previous ophthalmic history. At this time, visual acuity was 20/20-2 OS and 10-2 HVF was within normal limits, though Amsler grid testing revealed 2 blind spots immediately superior and nasal to the center of fixation (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 7, which shows visual disturbances assessed with an Amsler grid). SD-OCT imaging revealed no obvious disruptions of the outer retina (Figure 7A). AOSLO imaging in this area showed two areas of diffuse irregularities of the photoreceptor mosaic supero- and infero-nasal to foveal center, (Figure 7B) corresponding to the scotomas on Amsler grid testing.

Figure 7.

Subclinical photoreceptor defects following cgBOT. Subjects RR_0045, Case 8 (A, B) and SH_0874, Case 9 (C, D) had visual complaints despite normal clinical imaging with SD-OCT. Subject RR_0045 had a normal-appearing SD-OCT acquired using Spectralis (A). Subject SH_0874 had normal-appearing SD-OCT on both Spectralis and Cirrus, while imaging using the Bioptigen SD-OCT revealed a small focal disruption of the EZ and IZ (C). Vertical arrows indicate the area subtended by the AOSLO montages (B, D). The AOSLO images are displayed on a logarithmic scale and each shows clear photoreceptor disruption. Subject RR_0045 (B) had two areas of diffuse photoreceptor hyporeflectivity, while subject SH_0874 (D) had a small discrete lesion. The dashed black line on each AOSLO image indicates the location of the corresponding SD-OCT image. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Case 9-SH_0874

Subject SH_0874 (34-year-old male) was a restrained driver in a motor vehicle collision in which the airbag did not deploy. The subject sustained a bulging cervical disc secondary to the whiplash injury, but otherwise did not report striking his face or either orbit during the collision. He presented 1 month post trauma with the chief complaint of a right-sided segmentation of lines while reading and red desaturation within the right temporal hemifield. His visual acuity at this time was 20/40 OD and 20/20 OS. Fundus examination of the affected eye revealed white without pressure in the temporal periphery. No retinal detachments or hemorrhages were noted. An enlarged blind spot superiorly and diminished foveal sensitivity OD was seen on the 10-2 HVF. SD-OCT at this time was normal OU. Research imaging at 14 months post-trauma uncovered focal disruption of the IZ and EZ SD-OCT, though this was only revealed after repeated dense scanning through the foveal region (Figure 7C). This small defect was visualized on AOSLO as a well-circumscribed disruption of the foveal cone mosaic (Figure 7D). The AOSLO lesion measured 0.002 mm2, which would suggest that only a few hundred cones were affected in this individual.

Discussion

Clear alterations of outer retinal morphology were seen in 8 of 9 patients using clinical SD-OCT, and disruptions of the photoreceptor mosaic were seen in all subjects with AOSLO imaging. Given the time post-trauma at which we imaged these subjects, our data would be consistent with permanent photoreceptor disruption, though the extent and type of disruption varies dramatically across subjects. We have presented a number of examples highlighting how AOSLO can provide information regarding photoreceptor health beyond what can be appreciated on SD-OCT, even with the application of more sophisticated analysis of the SD-OCT images. In subject SR_0821 (Case 1), longitudinal SD-OCT scans show the apparent resolution of the initial disruption of the outer retinal bands. However, imaging with AOSLO revealed sustained and severe cone loss in the nasal retina. Although ONL thinning can be appreciated on respective SD-OCT scans, the distinction between cone versus rod loss in this subject would not have been possible without the application of AOSLO. A similar pattern of cone-dominated photoreceptor loss has been reported in a case of acute macular neuroretinopathy (AMN), where the photoreceptor loss appeared to be cone-dominated.16 Furthermore, the early hyperreflective changes seen in SR_0821 are also consistent with those reported by Fawzi et al in patients with AMN.39 Likewise, Nentwich et al showed that traumatic retinopathy can result in outer retinal changes resembling AMN.40

Another example came from WW_0920 (Case 3), where LRP analysis revealed absence of the IZ band on SD-OCT, with preservation of cone structure on AOSLO. This suggests possible RPE disruption, as opposed to primary photoreceptor degeneration. In our third example, we employed en face visualization of the EZ band on SD-OCT and showed good agreement in the measures of lesion area between the en face SD-OCT image and the AOSLO image (Figure 6). However, there were often visible photoreceptors inside the lesion zone marked on SD-OCT, demonstrating that seemingly continuous EZ and IZ focal lesions on SD-OCT do not necessarily represent complete photoreceptor loss. While these cases highlight the sensitivity of AOSLO in assessing photoreceptor structure, SD-OCT of course has advantages in assessing retinal structure in these patients. For example, in WW_0920 (Case 3), the vision of 4/200 could not be explained by the normal cone density findings on AOSLO. It was only through analysis of inner retinal thickness on SD-OCT that we identified a possible anatomical correlate for the subject’s vision loss. Thus, AOSLO and SD-OCT should be considered complementary tools in studying patients with cgBOT.

Of particular interest are the two subjects who showed no visible structural abnormalities on clinical SD-OCT (Case 8, RR_0045 and Case 9, SH_0874). Their chief complaints following clinical resolution of commotio retinae were line disjunction when reading. After clinical imaging, fundus examination, and central static perimetry failed to find an abnormality, both subjects were referred to our study and both showed clear photoreceptor lesions on AOSLO. Clinical OCT protocols likely missed the defects due to lower B-scan densities than the volumetric Bioptigen SD-OCT used in this study.41,42 The focal disruption seen on AOSLO in SH_0874 measured 30 μm in diameter, well within the lateral resolution of SD-OCT, however it was only after repeated dense scanning with the Bioptigen SD-OCT that we were able to detect the disruption. Likewise, in RR_0045, it appears that the “foveal” B-scan landed just between two moderate areas of photoreceptor disruption. The B-scans on either side of this were about 60 μm away, easily missing the photoreceptor loss. Thus, without those scans, it is difficult to say whether the disruption would have manifest on SD-OCT had the B-scan been collected through the lesion. Zucchiatti et al recently examined a patient following severe head and cervical injury and observed a similar outer lamellar defect using clinical SD-OCT.43 Thus the ability to detect these lesions with clinical scanning protocols appears to be both a matter of luck and lesion size. Our cases are also quite similar to a previous report, where following severe head trauma, a patient described a crescent shaped scotoma but clinical SD-OCT imaging was normal,15 though a subtle defect was visible when using a Bioptigen.44 We propose that AOSLO imaging be considered when evaluating patients with unexplained vision loss and/or scotomas following ocular trauma of any cause, especially in patients with normal SD-OCT findings. It is unclear what consequence these structural changes may have on the retinal response to subsequent environmental or genetic insults, though this bears consideration when evaluating these patients later in life. Furthermore, the diagnostic clarity offered by AOSLO imaging can be of significant value from a patient perspective, by helping provide patient peace of mind, resolve accusations of malingering, and serve of medicolegal use when sub-clinical photoreceptor damage interferes with the ability to perform personal/professional duties.

Limitations of this study include the small number of subjects, variable time between trauma and research imaging (range = 1 month to 6 years), lack of acute clinical SD-OCT and infrared imaging, and lack of AOSLO imaging immediately post-trauma. Thus, conclusions regarding the relationship between initial presentation and subsequent recovery of retinal structure could not be made. An additional limitation is incomplete functional data on these subjects, though our primary focus here was to assess the structural abnormalities in this patient population. Further longitudinal studies incorporating serial tracking of retinal structure (e.g., AOSLO and SD-OCT and function (e.g., microperimetry) following cgBOT are needed to identify potential prognostic biomarkers for photoreceptor recovery following ocular trauma. It is important to note that our results represent a limited range in the spectrum of cgBOT. Patients had sufficient trauma to result in clinically detectable posterior segment injury and/or visual symptoms, yet maintain media clarity to allow imaging of the retina. It would be interesting to image patients with lesser degrees of trauma (perhaps even those with no visual complaints) to see if there are subclinical abnormalities detectable with adaptive optics imaging.

Our results have important implications for patients with traumatic brain injury, which has been associated with numerous vision problems, including blurred vision, increased light sensitivity, double vision, visual field loss or reduction, and difficulties with eye movements.45–50 In a recent report on U.S. soldiers sustaining blast injuries during Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom, Weichel et al found that 21% of all traumatic brain injury cases had concomitant ocular injuries.48 Although the study found no correlation between traumatic brain injury and decreased visual acuity, it offered that other outcome measures require further investigation to fully understand the extent of visual dysfunction in cases of traumatic brain injury. A number of studies on civilian cases of traumatic brain injury have reported that the prevalence of visual field defects is approximately 35% with the majority categorized as scattered defects (occurring in more than one visual field).45 In our study, subject KS_0931 (Case 7), a 20 year military veteran with an extensive history of blast-related combat ocular trauma and mild traumatic brain injury, was found to have focal defects in the foveal photoreceptor mosaic of both eyes corresponding to bilateral central scotomas despite having 20/30 visual acuity in both eyes. Our findings suggest that while injury to the visual cortex or optic nerve is often blamed for many of the visual symptoms associated with traumatic brain injury, photoreceptor damage may play a greater role than currently appreciated. Thus, we propose that AOSLO and SD-OCT should be considered in the evaluation of both military and civilian patients with visual complaints presenting with traumatic brain injury, mild traumatic brain injury, or post-concussive syndrome.

Supplementary Material

Figure that shows clinical imaging results for subject SR_0821. tif

Figure that shows ONL thickness in a subset of our patients compared to normal controls. tif

Figure that shows clinical imaging results for subject TC_10006. tif

Figure that shows clinical imaging results for subject DW_0665. tif

Figure that shows clinical imaging results for subject RS_0785. tif

Figure that shows clinical imaging results for subject WW_0923. tif

Figure that shows visual disturbances assessed with an Amsler grid for subject RR_0045. tif

Summary Statement.

High-resolution retinal imaging revealed variable disruption in retinal morphology in nine patients with visual complaints secondary to closed globe blunt ocular trauma. Discrepancies between findings from adaptive optics and optical coherency tomography provide unique insight into the anatomical basis for visual complaints in these patients.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This study was supported by NIH Grants UL1TR000055 and P30EY001931. The E. Matilda Ziegler Foundation for the Blind, Thomas M. Aaberg, Sr., Retina Research Fund, Foundation Fighting Blindness, RD and Linda Peters Foundation, Marrus Family Foundation, Bendheim Lowenstein Family Foundation, Wise Family Foundation, Chairman’s Research Fund of the NYEEI, and an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness. This investigation was conducted in a facility constructed with support from Research Facilities Improvement Program Grant Number C06RR016511 from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health. The sponsors or funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of this research. Alfredo Dubra, PhD. holds a Career Award at the Scientific Interface from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

The authors would like to thank Pooja Godara, Jon Young, Brian Higgins, Sean Hansen, David Kay, and Megan Land for assistance and guidance with image processing and registration.

References

- 1.Berlin R. Zur sogenannten commotio retinae. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 1873;1:42–78. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams DF, Mieler WF, Williams GA. Posterior segment manifestations of ocular trauma. Retina. 1990;10 (Suppl 1):S35–44. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199010001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sipperley JO, Quigley HA, Gass DM. Traumatic retinopathy in primates. The explanation of commotio retinae. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978;96:2267–2273. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1978.03910060563021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mansour AM, Green WR, Hogge C. Histopathology of commotio retinae. Retina. 1992;12:24–28. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199212010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Souza-Santos F, Lavinsky D, Moraes NS, et al. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography in patients with commotio retinae. Retina. 2012;32:711–718. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318227fd01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oh J, Jung JH, Moon SW, et al. Commotio retinae with spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Retina. 2011;31:2044–2049. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31820f4bb4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sony P, Venkatesh P, Gadaginamath S, Garg SP. Optical coherence tomography findings in commotio retina. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;34:621–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyer CH, Rodrigues EB, Mennel S. Acute commotio retinae determined by cross-sectional optical coherence tomography. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2003;13:816–818. doi: 10.1177/1120672103013009-1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park JY, Nam WH, Kim SH, et al. Evaluation of the central macula in commotio retinae not associated with other types of traumatic retinopathy. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2011;25:262–267. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2011.25.4.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahn SJ, Woo SJ, Kim KE, et al. Optical coherence tomography morphologic grading of macular commotio retinae and its association with anatomic and visual outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;156:994–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saleh M, Letsch J, Bourcier T, et al. Long-term outcomes of acute traumatic maculopathy. Retina. 2011;31:2037–2043. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31820e8d78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen H, Lu Y, Huang H, et al. Prediction of visual prognosis with spectral-domain optical coherence tomography in outer retinal atrophy secondary to closed globe trauma. Retina. 2013;33:1258–1262. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31827b63ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dubra A, Sulai Y. Reflective afocal broadband adaptive optics scanning ophthalmoscope. Biomed Opt Express. 2011;2:1757–1768. doi: 10.1364/BOE.2.001757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rossi EA, Chung M, Dubra A, et al. Imaging retinal mosaics in the living eye. Eye. 2011;25:301–308. doi: 10.1038/eye.2010.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stepien KE, Martinez WM, Dubis AM, et al. Subclinical photoreceptor disruption in response to severe head trauma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130:400–402. doi: 10.1001/archopthalmol.2011.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansen SO, Cooper RF, Dubra A, et al. Selective cone photoreceptor injury in acute macular neuroretinopathy. Retina. 2013;33:1650–1658. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31828cd03a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carroll J, Neitz M, Hofer H, et al. Functional photoreceptor loss revealed with adaptive optics: An alternate cause of color blindness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8461–8466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401440101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mkrtchyan M, Lujan BJ, Merino D, et al. Outer retinal structure in patients with acute zonal occult outer retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153:757–768. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanna H, Dubis AM, Ayub N, et al. Retinal imaging using commercial broadband optical coherence tomography. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94:372–376. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.163501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spaide RF, Curcio CA. Anatomical correlates to the bands seen in the outer retina by optical coherence tomography: Literature review and model. Retina. 2011;31:1609–1619. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3182247535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spaide RF. Questioning optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2203–2204. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dubis AM, McAllister JT, Carroll J. Reconstructing foveal pit morphology from optical coherence tomography imaging. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93:1223–1227. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.150110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carroll J, Baraas RC, Wagner-Schuman M, et al. Cone photoreceptor mosaic disruption associated with Cys203Arg mutation in the M-cone opsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:20948–20953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910128106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McAllister JT, Dubis AM, Tait DM, et al. Arrested development: High-resolution imaging of foveal morphology in albinism. Vision Res. 2010;50:810–817. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lujan BJ, Roorda A, Knighton RW, Carroll J. Revealing Henle’s fiber layer using spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthamol Vis Sci. 2011;52:1486–1492. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang Y, Cideciyan AV, Papastergiou GI, et al. Relation of optical coherence tomography to microanatomy in normal and rd chickens. Invest Ophthamol Vis Sci. 1998;39:2405–2416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Godara P, Cooper RF, Sergouniotis PI, et al. Assessing retinal structure in complete congenital stationary night blindness and Oguchi disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154:987–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dubis AM, Hansen BR, Cooper RF, et al. Relationship between the foveal avascular zone and foveal pit morphology. Invest Ophthamol Vis Sci. 2012;53:1628–1636. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dubra A, Sulai Y, Norris JL, et al. Noninvasive imaging of the human rod photoreceptor mosaic using a confocal adaptive optics scanning ophthalmoscope. Biomed Opt Express. 2011;2:1864–1876. doi: 10.1364/BOE.2.001864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooper RF, Dubis AM, Pavaskar A, et al. Spatial and temporal variation of rod photoreceptor reflectance in the human retina. Biomed Opt Express. 2011;2:2577–2589. doi: 10.1364/BOE.2.002577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pinhas A, Dubow M, Shah N, et al. In vivo imaging of human retinal microvasculature using adaptive optics scanning light ophthalmoscope fluorescein angiography. Biomed Opt Express. 2013;4:1305–1317. doi: 10.1364/BOE.4.001305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dubra A, Harvey Z. Registration of 2D Images from Fast Scanning Ophthalmic Instruments. The 4th International Workshop on Biomedical Image Registration; Lübeck, Germany. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kay DB, Land ME, Cooper RF, et al. Outer retinal structure in Best vitelliform macular dystrophy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131:1207–1215. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garrioch R, Langlo C, Dubis AM, et al. Repeatability of in vivo parafoveal cone density and spacing measurements. OptomVis Sci. 2012;89:632–643. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3182540562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Curcio CA, Sloan KR, Kalina RE, Hendrickson AE. Human photoreceptor topography. J Comp Neurol. 1990;292:497–523. doi: 10.1002/cne.902920402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chui TYP, Song HX, Burns SA. Individual variations in human cone photoreceptor packing density: Variations with refractive error. Invest Ophthamol Vis Sci. 2008;49:4679–4687. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cideciyan AV, Hufnagel RB, Carroll J, et al. Human cone visual pigment deletions spare sufficient photoreceptors to warrant gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther. 2013;24:993–1006. doi: 10.1089/hum.2013.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carroll J, Rossi EA, Porter J, et al. Deletion of the X-linked opsin gene array locus control region (LCR) results in disruption of the cone mosaic. Vision Res. 2010;50:1989–1999. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fawzi AA, Pappuru RR, Sarraf D, et al. Acute Macular Neuroretinopathy: Long-term insights revealed by multimodal imaging. Retina. 2012;32:1500–1513. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318263d0c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nentwich MM, Leys A, Cramer A, Ulbig MW. Traumatic retinopathy presenting as acute macular neuroretinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97:1268–1272. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-303354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Odell D, Dubis AM, Lever JF, et al. Assessing errors inherent in OCT-derived macular thickness maps. J Ophthalmol. 2011:Article ID 692574, 1–9. doi: 10.1155/2011/692574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sadda SR, Keane FB, Ouyang Y, et al. Impact of scanning density on measurements from spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthamol Vis Sci. 2010;51:1071–1078. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zucchiatti I, Querques G, Querques L, et al. En face optical coherence tomography visualization of post-traumatic photoreceptor disruption. J Fr Ophthalmol. 2013;36:e159–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2012.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stepien KE, Martinez WM, Dubis AM, et al. Detection of Photoreceptor Disruption after Commotio Retinae using Adaptive Optics Scanning Laser Ophthalmoscopy. Invest Ophthamol Vis Sci. 2011;52:E-Abstract: 6657. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suchoff IB, Kapoor N, Ciuffreda KJ, et al. The frequency of occurrence, types, and characteristics of visual field defects in acquired brain injury: a retrospective analysis. Optometry. 2008;79:259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.optm.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kapoor N, Ciuffreda KJ. Vision disturbances following traumatic brain injury. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2002;4:271–280. doi: 10.1007/s11940-002-0027-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brahm KD, Wilgenburg HM, Kirby J, et al. Visual impairment and dysfunction in combat-injured servicemembers with traumatic brain injury. OptomVis Sci. 2009;86:817–825. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181adff2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weichel ED, Colyer MH, Ludlow SE, et al. Combat ocular trauma visual outcomes during operations iraqi and enduring freedom. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:2235–2245. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Phillips BN, Chun DW, Colyer M. Closed globe macular injuries after blasts in combat. Retina. 2013;33:371–379. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318261a726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goodrich GL, Flyg HM, Kirby JE, et al. Mechanisms of TBI and visual consequences in military and veteran populations. OptomVis Sci. 2013;90:105–112. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e31827f15a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure that shows clinical imaging results for subject SR_0821. tif

Figure that shows ONL thickness in a subset of our patients compared to normal controls. tif

Figure that shows clinical imaging results for subject TC_10006. tif

Figure that shows clinical imaging results for subject DW_0665. tif

Figure that shows clinical imaging results for subject RS_0785. tif

Figure that shows clinical imaging results for subject WW_0923. tif

Figure that shows visual disturbances assessed with an Amsler grid for subject RR_0045. tif