Abstract

Background:

Patients with Alzheimer disease (AD) typically have impaired declarative memory as a result of hippocampal damage early in the disease. Far less is understood about AD’s effect on emotion.

Objective:

We investigated whether feelings of emotion can persist in patients with AD, even after their declarative memory for what caused the feelings has faded.

Methods:

A sample of 17 patients with probable AD and 17 healthy comparison participants (case-matched for age, sex, and education) underwent 2 separate emotion induction procedures in which they watched film clips intended to induce feelings of sadness or happiness. We collected real-time emotion ratings at baseline and at 3 post-induction time points, and we administered a test of declarative memory shortly after each induction.

Results:

As expected, the patients with AD had severely impaired declarative memory for both the sad and happy films. Despite their memory impairment, the patients continued to report elevated levels of sadness and happiness that persisted well beyond their memory for the films. This outcome was especially prominent after the sadness induction, with sustained elevations in sadness lasting for more than 30 minutes, even in patients with no conscious recollection for the films.

Conclusions:

These findings indicate that patients with AD can experience prolonged states of emotion that persist well beyond the patients’ memory for the events that originally caused the emotion. The preserved emotional life evident in patients with AD has important implications for their management and care, and highlights the need for caretakers to foster positive emotional experiences.

Key Words: amnesia, emotion, aging, declarative memory, emotional memory

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- DES

Differential Emotions Scale

- POMP

percent of maximum possible

- VAS

visual analog scale

The experience of an emotion and the memory for what caused that emotion often seem inseparable. For instance, people who feel sad because of the end of a relationship might conclude that their prolonged state of sadness is fueled by their ruminations about the relationship and its dissolution. They might even believe that by erasing the emotion-inducing memory, the sadness will also fade away.

Our recent research (Feinstein et al, 2010) has challenged this notion by showing that feelings of emotion can persist independent of the declarative memory for what caused the emotion—ie, stuck in a mood and you can’t remember why. We discovered this intriguing finding in a group of rare neurological patients with focal bilateral hippocampal damage that resulted in severe anterograde amnesia (Feinstein et al, 2010). After watching film clips that induced states of either sadness or happiness, these amnesic patients continued to experience elevated levels of the induced emotion, even when they had no declarative memory for the film clips. They were “happy” or “sad” but could not remember why.

A hallmark of Alzheimer disease (AD) is impaired declarative memory associated with hippocampal atrophy (Fox et al, 2001; Hyman et al, 1984, 1990; Jack et al, 1997; Mickes et al, 2007). Thus, similar to patients with hippocampal amnesia, patients with AD have difficulty acquiring and remembering new information. However, the brain damage in AD is not restricted to the hippocampus (Fox et al, 2001; Mickes et al, 2007), and often includes widespread damage to other regions. This progressive neurodegenerative process leads to the gradual decline of cognitive functions beyond the domain of memory, commonly impacting attention, visuospatial processing, and verbal fluency (Fox et al, 2001; Mickes et al, 2007).

In contrast to memory, emotional processing may be relatively preserved in patients with AD, especially during the early stages of the disease (Broster et al, 2012; Mori et al, 1999). Multiple studies have suggested that patients with AD maintain their ability to recognize (Narme et al, 2013) and express (Magai et al, 1996) emotions, and to benefit from emotional memory enhancement (Broster et al, 2012; Bucks and Radford, 2004; Fleming et al, 2003; Kazui et al, 2000; Moayeri et al, 2000; Nashiro and Mather, 2011).

We should note that the literature on emotion has some variability in findings, with several studies showing impaired emotional processing in AD (eg, Hamann et al, 2000; Kensinger et al, 2002). Such differences might reflect different patterns of underlying neuropathology. These unresolved questions remain an ongoing area of investigation in AD research.

Blessing et al (2006, 2012) have suggested that individuals with AD can implicitly remember emotional information despite having declarative memory impairment. Further support for these findings comes from clinical cases (Evans-Roberts and Turnbull, 2011; Sabat and Collins, 1999). An example is Mr A., a patient with AD who displayed persistent dislike for a doctor after a negative experience at an appointment, even though he could not recall the specific experience (Evans-Roberts and Turnbull, 2011). In addition to supporting “nonconscious” learning of emotional information, this case suggests that patients with AD can have feelings dissociated from memory. However, no study to date has systematically assessed the feelings of patients with AD and whether these feelings can persist beyond the memory for the original emotion-inducing event.

In this study we investigated whether feelings of emotion could persist in patients with AD even after their declarative memory for what caused the feelings had faded. Using a procedure similar to our previous study (Feinstein et al, 2010), we examined whether the phenomenon of “feelings without memory” that we had discovered in patients with hippocampal amnesia might also be observed in patients with AD. Given the aforementioned similarities between hippocampal amnesia and AD, we hypothesized that patients with AD might also feel a prolonged state of induced emotion despite severe declarative memory deficits for the events that had originally triggered the emotion.

METHODS

Participants

We tested 11 women and 6 men with probable AD. We recruited 13 of the patients from the Benton Neuropsychology Laboratory at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics. These patients had been diagnosed under the auspices of the Department of Neurology at our institution, in the context of their medical and neuropsychological workup for dementia, following the McKhann et al criteria (2011). We recruited the 4 other patients through the Alzheimer’s Association. These patients had been diagnosed at an outside hospital by their primary care physician or neurologist.

We also tested 11 women and 6 men as healthy comparison participants. We recruited this group from the Cognitive Neuroscience Registry for Normative Data at the University of Iowa.

To determine eligibility for the AD group, we used interviews with the candidate and caregiver, neuropsychological measures, and medical records. For both groups, we excluded candidates who had a neurologic disorder (other than AD for the patient group), a psychiatric disorder (eg, major depression or anxiety), uncorrected severe vision or hearing impairment, a history of learning disability, impaired basic attention or visuospatial abilities, or impaired comprehension.

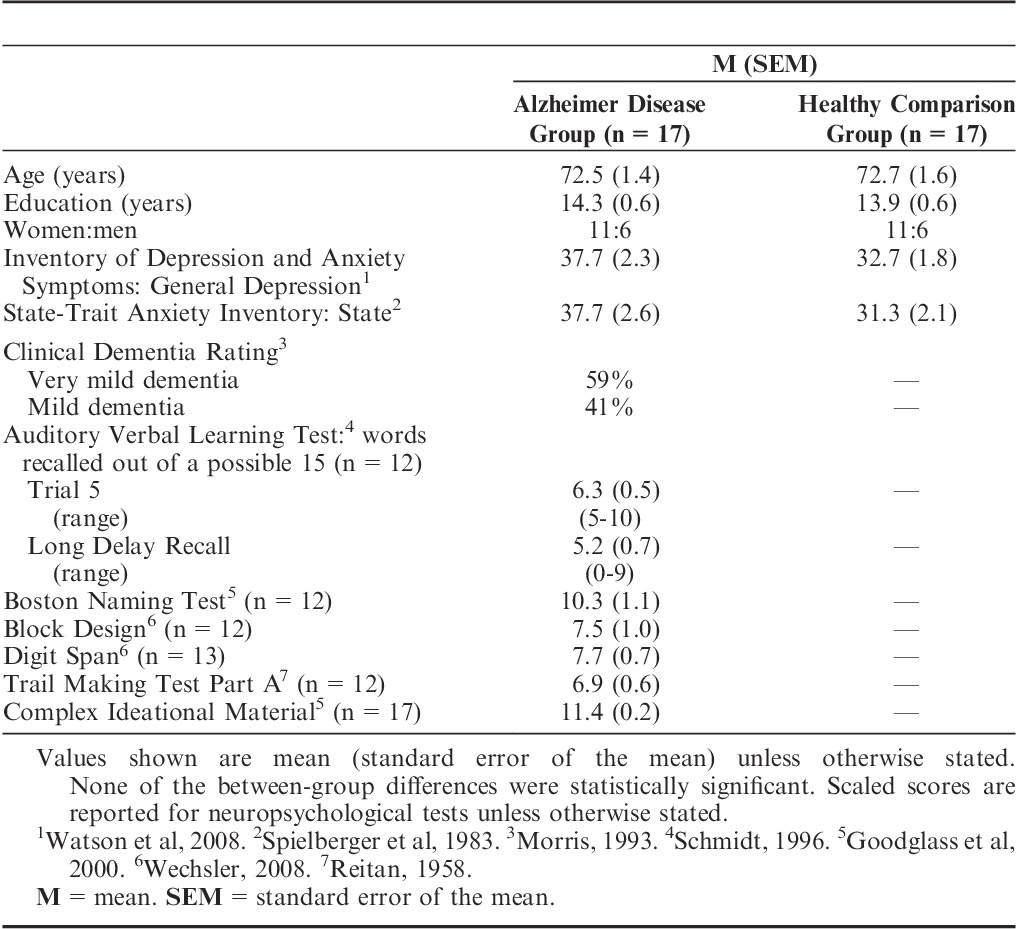

Table 1 lists the 2 groups’ demographic and neuropsychological data. The severity of AD in the patient group ranged from very mild to mild, as measured by the Clinical Dementia Rating scale (Morris, 1993). The neuropsychological tests confirmed that the patients had impaired declarative memory but relatively preserved comprehension, attention, and visuospatial processing.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Neuropsychological Data

The 2 groups were well-matched demographically. There were no significant between-group differences in age, education, depression, or state anxiety (all P values >0.05). The AD group had higher scores on the General Depression portion of the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (Watson et al, 2008); however, mean General Depression scores in clinically depressed patients are typically above 68 (Watson et al, 2008), while our patients with AD had a mean score nearly 30 points lower, well below the range of clinical depression.

Our study was approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board. All participants gave their informed written consent or assent before beginning the study. We used previously standardized procedures (DeRenzo et al, 1998) to determine the patients’ capacity to consent. When we determined that patients could not consent, their caregivers provided informed consent and the patients signed an assent document.

Procedure

Our procedures closely followed those that we had used in our study of patients with hippocampal amnesia (Feinstein et al, 2010). To begin, the participants completed the first (“baseline”) of 4 emotion measures (see the Emotion Measures section and Appendix 1 below; the Appendix is a copy of the actual emotion measure). Then the participants watched a series of film, television, and video excerpts (“film clips”) designed to induce sadness. As soon as the film clips ended, the participants completed the second emotion measure (“after induction”). Five minutes after the clips ended, we gave the participants a memory test that took approximately 5 minutes to complete (see the Memory Test section below). About 10 to 15 minutes after the clips ended, the participants completed the third emotion measure (“after memory test”). About 20 to 30 minutes after the end of the films, the participants completed their fourth emotion measure (“final rating”). We instructed the participants to remain silent between the third and fourth emotion measures.

Then we gave the participants a 5-minute break, during which they were instructed to relax and use the restroom. After the break, we started the happiness induction, using the same procedures. We always gave the sadness induction before the happiness induction so that all participants would end the experiment with a positive experience.

To minimize demand characteristics during the experiment, we repeatedly reminded participants, “There are no right or wrong answers. We ask only that you answer as honestly as possible.”

Experimental Materials

Emotion Induction

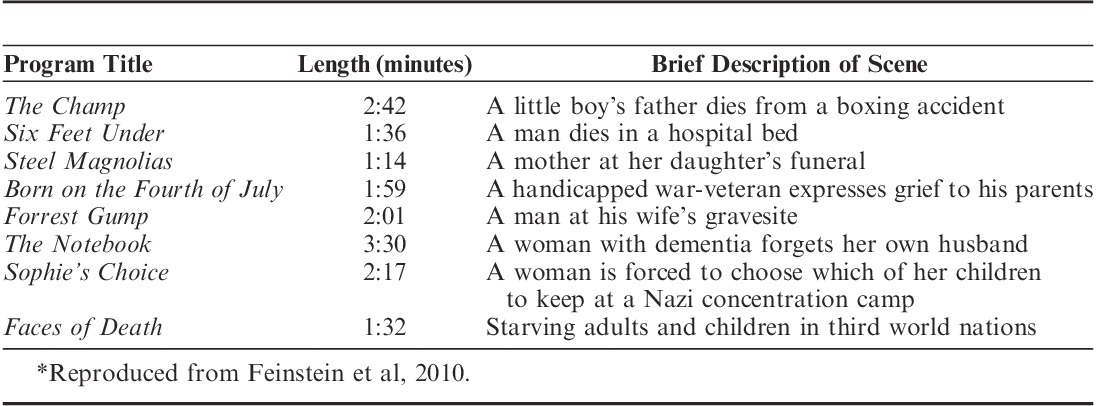

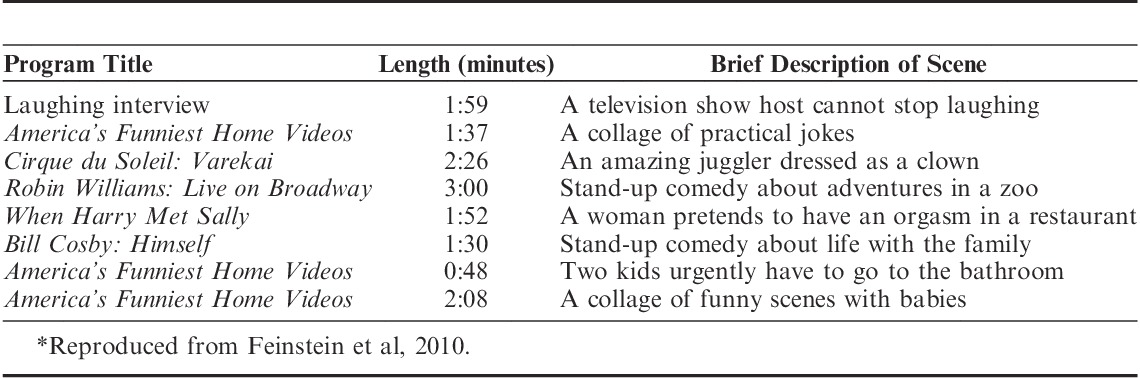

This experiment used the same emotion induction procedure as we used in Feinstein et al (2010). Each emotion induction entailed watching a series of 8 emotionally evocative film clips totaling about 18 minutes in length. The clips were chosen to induce states of either sadness, by portraying themes of loss and death (Table 2), or happiness, by showing jokes and other funny and amusing situations (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Film Clips Shown in the Sadness Induction*

TABLE 3.

Film Clips Shown in the Happiness Induction*

Participants were not told before the experiment about the valence of the films that they would be watching. For each induction, they viewed the entire set of clips in a single sitting, with a brief rest period of 10 to 20 seconds between films.

Many of the film clips were chosen from sets of previously validated films shown to be highly effective at inducing emotion across a large sample of participants (Gross and Levenson, 1995; Philippot, 1993; Rottenberg et al, 2007; Schaefer et al, 2010). We purposefully selected short clips, averaging about 2 minutes, to lessen problems arising from patients forgetting what was happening during each scene.

The sadness and happiness inductions can be obtained for research purposes by contacting coauthor Justin S. Feinstein at jfeinstein@laureateinstitute.org.

Emotion Measures

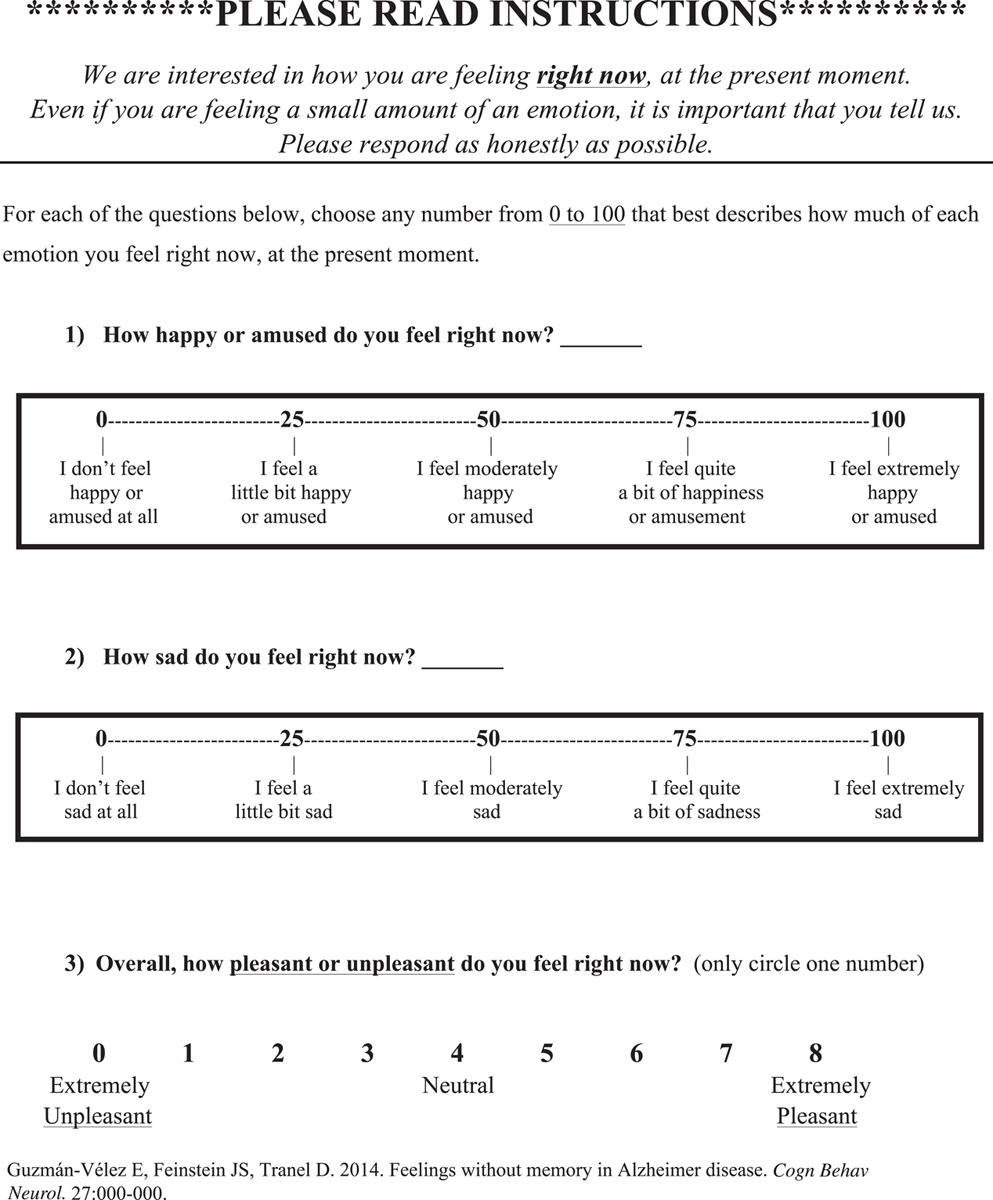

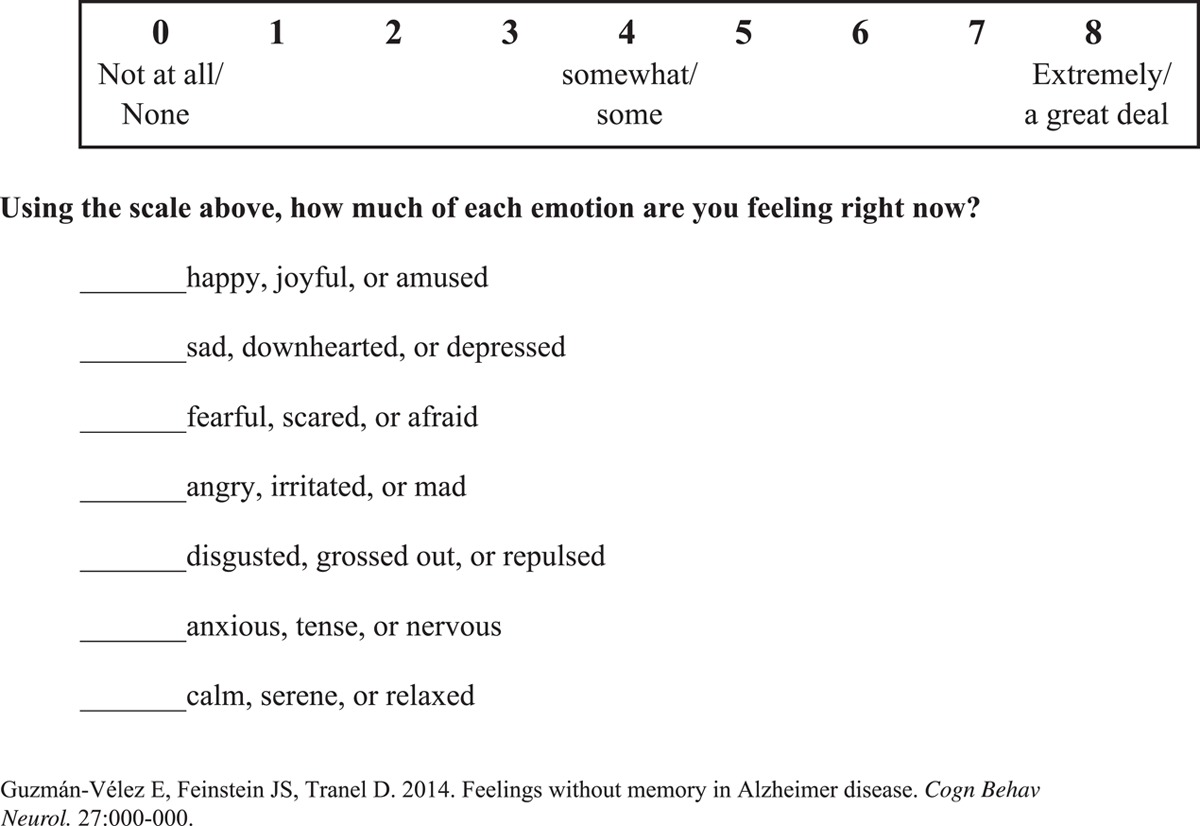

As noted, participants completed the emotion measure (see the actual measure in Appendix 1) at 4 points during each induction: baseline, after induction, after memory test, and final rating. We asked the participants to rate how they “feel right now, at the present moment” on several emotion scales. Participants rated how sad or happy they felt using 2 modified 100-point visual analog scales (VAS) that ranged from “I don’t feel sad/happy at all” (0) to “I feel extremely sad/happy” (100).

The participants also indicated how pleasant they felt using a 9-point bipolar valence scale that ranged from “extremely unpleasant” (0) to “extremely pleasant” (8).

Further, the participants rated their current experience of 7 emotions (sadness, anger, disgust, fear, anxiety, peacefulness, and happiness) using a 9-point scale that ranged in intensity from “none” (0) to “extremely” (8). We selected these 7 emotion terms from the Differential Emotions Scale (DES), which has been validated for measuring the subjective experience of emotion during film clips (Schaefer et al, 2010).

Memory Test

Participants took the memory test 5 minutes after they finished watching each set of film clips. This test had 3 sections: free recall, verbal recognition, and picture recognition.

For free recall, the participants were told, “Please describe 3 of the films in as much detail as possible. Try to describe 1 film at a time. Begin with the first film that comes to your mind.” All responses were audiorecorded and then transcribed by a research assistant. Two raters, working independently, used guidelines established by Feinstein et al (2010) to code the transcriptions for the total number of factual details reported about the films. The raters demonstrated excellent interrater reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient=0.965, P<0.001). We calculated the total number of details recalled by each participant by averaging the scores from the 2 raters. Incorrect details were not allocated points, nor did they affect the sum of correct details.

The verbal recognition test consisted of 10 multiple-choice questions that probed basic knowledge of what had been presented in the film clips. Each question had 1 correct answer and 4 foils.

The picture recognition test assessed participants’ nonverbal recognition of faces presented in the film clips. In this test we randomly presented 10 different still-frame pictures of faces, 1 at a time. Only 5 of the faces had appeared in the film clips. For each face, the participants were to answer “yes” or “no” about whether they remembered having seen the face in 1 of the film clips. We asked them to make a choice on each face, even if they had to guess. We calculated a sensitivity index (d′) for the picture recognition scores.

Statistical Analysis

We performed the statistical analyses using SPSS® version 19 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois) and created all graphs using GraphPad® Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California). All t tests used a significance threshold of P<0.05; when appropriate, we used the Holm's Sequential Bonferroni procedure to correct for multiple comparisons. We used 1-tailed paired sample t tests to look for significant between-group differences in measures of memory.

We conducted 2-tailed paired sample t tests to look for significant between-group differences in baseline VAS ratings. To determine whether the inductions were successful, we computed 1-tailed paired sample t tests for each group between the baseline VAS ratings and the VAS ratings obtained immediately after each induction. We analyzed differences in emotion ratings between the groups using a 3×2 (time×group) 1-way analysis of variance. To examine the relationship between sustained feeling and memory, we computed a Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient between the degree of sadness or happiness experienced during the final emotion rating and each participant’s free recall performance.

Before starting the statistical analysis, we converted all valence ratings and DES emotion ratings (originally using scales of 0 to 8) into standardized units of 0% to 100%, representing the “percent of maximum possible” (POMP) scores for each scale (Cohen et al, 1999). This conversion allowed us to analyze the valence and DES ratings on the same scale as the VAS ratings, which were already scaled from 0 to 100 and thus already in POMP units. Then we calculated composite scores for each induction to represent global changes in negative and positive affect.

For the sadness induction, we calculated the negative affect composite score for each participant by averaging his/her POMP scores for the following variables: sadness VAS, sadness DES, anger DES, disgust DES, fear DES, anxiety DES, and valence scale (reverse scored). We calculated the positive affect composite score by averaging the happiness VAS, happiness DES, and peacefulness DES scores.

For the happiness induction, we calculated the positive affect composite score for each participant by averaging his/her POMP scores for the following variables: happiness VAS, happiness DES, peacefulness DES, and valence scale. We calculated the negative affect composite score by averaging sadness VAS, sadness DES, anger DES, disgust DES, fear DES, and anxiety DES scores.

To assess for changes in each participant’s emotional experience induced by the film clips, we computed POMP difference scores by subtracting the baseline rating from each post-induction rating.

RESULTS

Sadness Induction

Memory

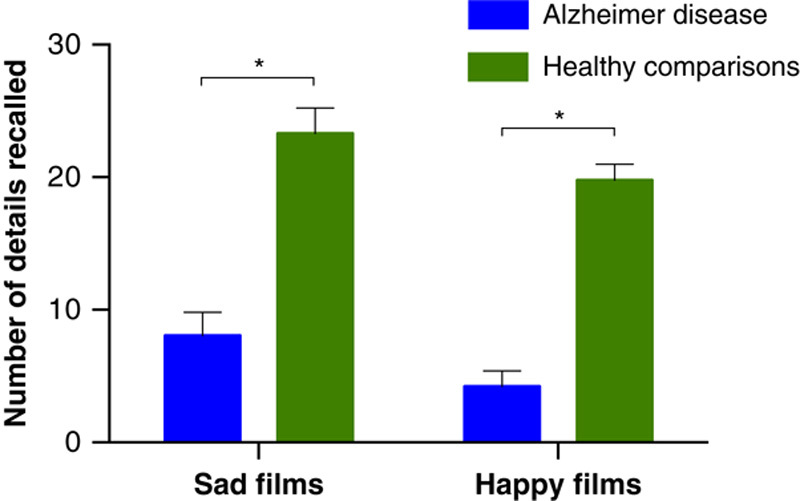

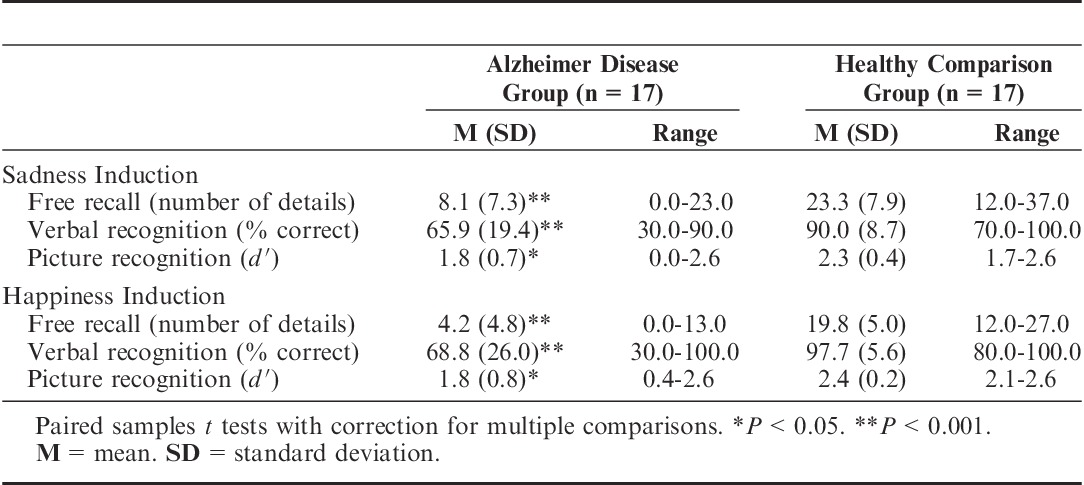

The memory test revealed that the AD group retained significantly less information about the sad films than did the healthy comparison group (t16=5.78, P<0.001) (Figure 1 and Table 4). Four patients with AD were unable to recall any factual details about the sad film clips, and 1 patient did not even remember having watched any film clips. The AD group also performed significantly worse than the healthy comparison group on the tests of verbal recognition (t16=4.29, P<0.001) and picture recognition (t16=2.23, P<0.05), meaning that the healthy comparison group had better performance on all 3 measures of memory (Table 4).

FIGURE 1.

Free recall: Average number of details that the 2 groups of participants recalled from the film clips after the sadness and happiness inductions. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. *P<0.001.

TABLE 4.

Memory Test Scores as a Function of Valence and Measure of Memory

Emotional State

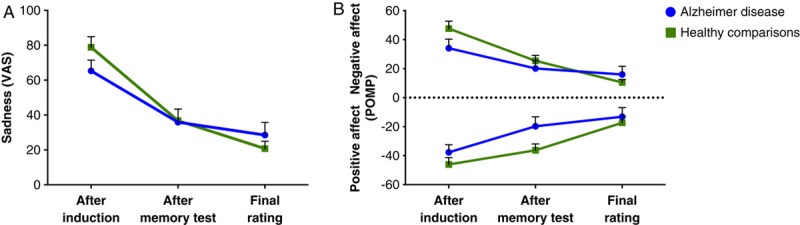

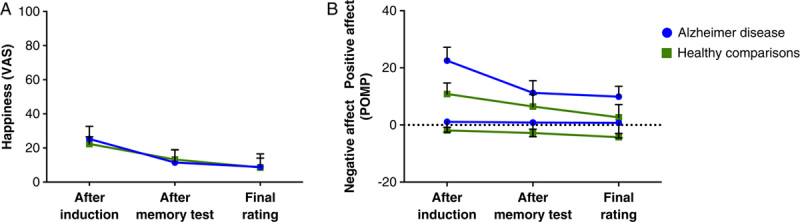

Both groups reported significant increases in their level of sadness (AD: t16=10.32, P<0.001; healthy comparisons: t16=12.88, P<0.001) immediately after watching the sad film clips, indicating that the sadness induction was effective (Figure 2). The 2 groups reported similar levels of sadness and negative affect. The groups did not differ significantly in their sadness VAS ratings and negative affect after the induction (F1,32=2.40; F1,32=3.42), after the memory test (F1,32=0.01; F1,32=0.88), or in the final rating (F1,32=0.86; F1,32=0.63).

FIGURE 2.

Change from baseline in the emotion ratings after watching the sad film clips. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Panel A: Average change in sadness reported on a modified visual analog scale (VAS) that ranged from 0 (no sadness) to 100 (extreme sadness). Panel B: Average change in negative and positive affect, shown as percent of maximum possible (POMP).

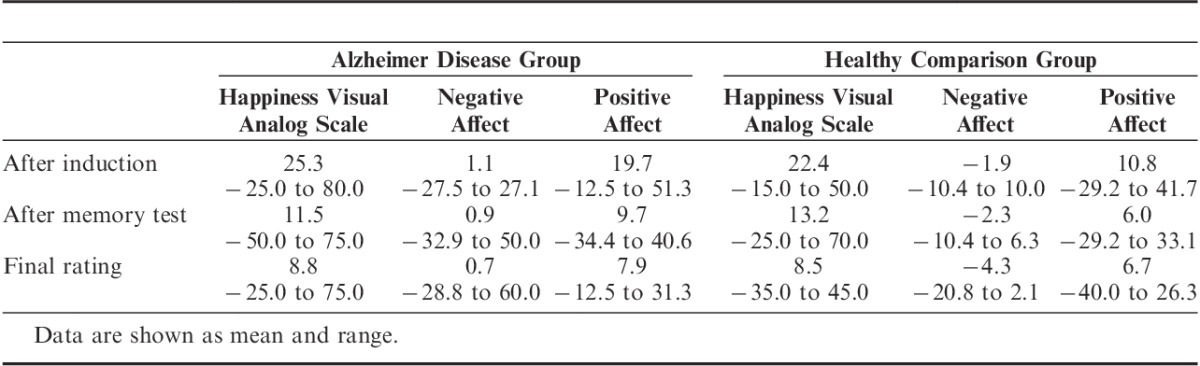

After the memory test, the AD group reported significantly more positive affect than the healthy comparison group (F1,32=4.43, P<0.05). There was no significant between-group difference in positive affect after the induction (F1,32=1.42) or in the final rating (F1,32=0.31). Table 5 shows more detail about the emotion ratings.

TABLE 5.

Emotion Ratings after the Sadness Induction (Change from Baseline)

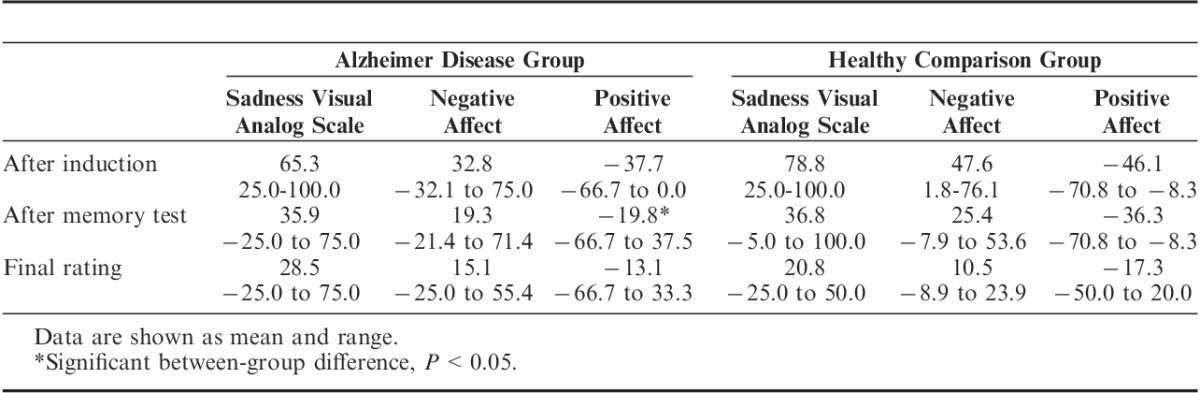

In strong support of our hypothesis, the patients with AD reported feeling elevated levels of sadness that lasted for up to 30 minutes after the films, despite having little or no recollection of the content (Figure 3). The AD group’s mean change in sadness from baseline to immediately after the induction was 65.29; after the memory test, 35.88; and in the final rating, 28.53. Across all participants, the correlation between memory performance and sadness during the final rating was significant, but in a negative direction (r=−0.37, n=34, P<0.05). This paradoxical effect actually suggests that the less the patients remembered about the films, the longer their sadness lasted.

FIGURE 3.

Relationship between declarative memory and the sustained experience of sadness in all participants. There was a significant negative correlation (r=−0.37, n=34, P<0.05) between the level of sadness reported in the final rating and the number of details recalled about the sad films. Each circle represents a participant’s change in sadness from baseline to final rating, and the number of film details recalled.

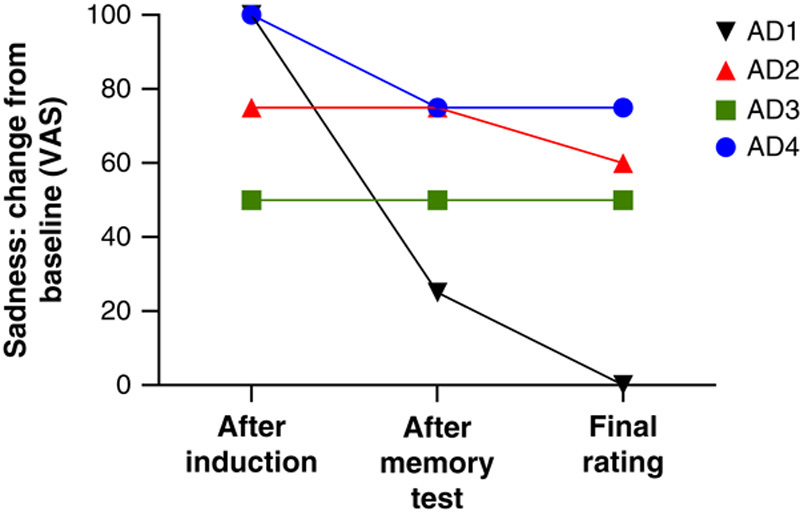

The dissociation between lingering feelings and impaired declarative memory was especially compelling in 4 patients with AD who could not recollect any details about the films. Despite their severe memory impairment, all 4 patients reported sustained feelings of sadness after the memory test, and 3 reported feeling sad even at the final rating 30 minutes post-induction (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Sadness ratings by 4 patients with Alzheimer disease who were unable to recall any details about the sadness-inducing film clips that they had just watched. Despite their severe memory impairment, the patients reported feeling high levels of sadness that lasted up to 30 minutes. VAS=visual analog scale.

We found no significant between-group differences in Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms scores (t16=1.16), sadness VAS at baseline (t16=0.23), or negative affect at baseline (t16=2.17). To explore further the influence of depressive symptoms on the experience and sustainability of sadness, we conducted a 2×2 (time × group) multivariate analysis of covariance. We used the last 2 emotion measures, “after memory test” and “final rating,” as dependent variables, because these measures reflected sustained feelings of sadness, and we used scores on the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms as the covariate. The analysis was not significant (F2,30=0.99, P=0.38). These results suggest that individual differences in depressive symptoms in our participants were not significantly related to their sustained experience of sadness.

Happiness Induction

Memory

The AD group retained significantly less information about the happy films than did the healthy comparison group (t16=11.17, P<0.001) (Figure 1). Five patients with AD were unable to recall any factual details about the happy films. The AD group also performed significantly worse than the healthy comparison group on both verbal recognition (t16=4.91, P<0.001) and picture recognition (t16=3.17, P<0.01) (Table 4).

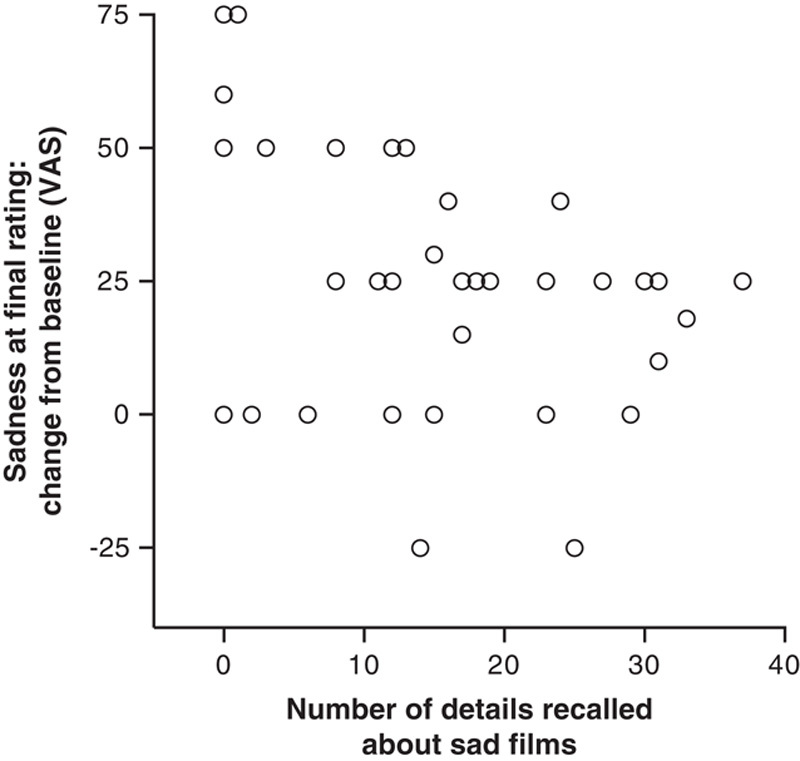

Emotional State

We found a significant increase in level of happiness in both the patients with AD (t16=3.41, P<0.01) and the healthy comparison participants (t16=5.51, P<0.001) immediately after they watched the film clips (Figure 5). The baseline happiness VAS ratings did not differ significantly between groups (t16=1.61).

FIGURE 5.

Change from baseline in the emotion ratings after watching the happy film clips. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Panel A: Average change in happiness reported on a modified visual analog scale (VAS) that ranged from 0 (no happiness) to 100 (extreme happiness). Panel B: Average change in positive and negative affect, shown as percent of maximum possible (POMP).

There were no significant between-group differences in happiness ratings obtained after the induction (F1,32=0.12), after the memory test (F1,32=0.04), or in the final rating (F1,32=0.00). Moreover, the groups did not differ significantly in their negative or positive affect ratings obtained after the induction (negative: F1,31=0.68; positive: F1,31=2.26), after the memory test (F1,31=0.40; F1,31=0.39), or at the final rating (F1,31=0.90; F1,32=0.87). Table 6 lists more detailed information about the emotion ratings.

TABLE 6.

Emotion Ratings after the Happiness Induction (Change from Baseline)

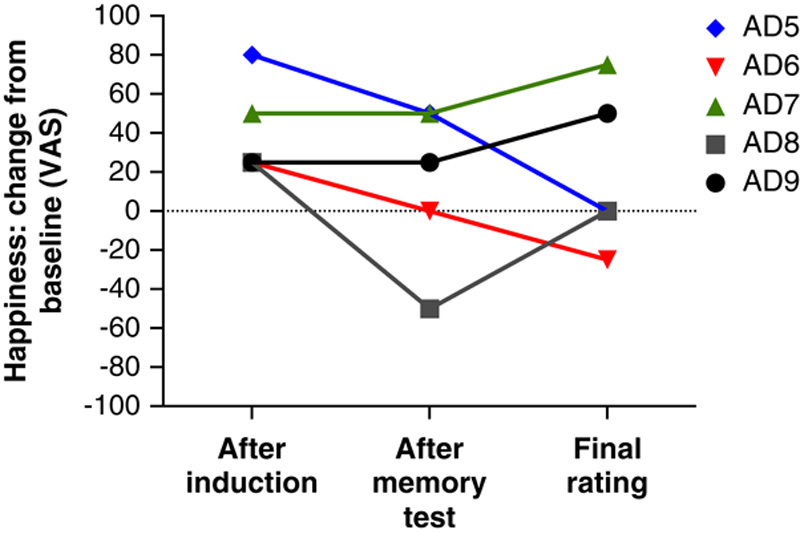

Similar to what we found with the sadness induction, 3 patients with AD had no recall at all for the happy films but continued to experience happiness beyond the memory test, and 2 of them showed elevations in happiness that persisted 30 minutes after the end of the films (Figure 6). This finding further illustrates the dissociation between impaired declarative memory and sustained feelings. We found no significant relationship between memory performance and ratings of happiness during the final rating (r=0.06, n=34).

FIGURE 6.

Happiness ratings by 5 patients with Alzheimer disease who did not recall any details about the happiness-inducing films that they had just watched. Despite their severe memory impairment, some of the patients reported feeling high levels of happiness that lasted up to 30 minutes. VAS = visual analog scale.

DISCUSSION

We found that patients with AD reported feeling sustained states of happiness and sadness despite their impaired declarative memory for the events that had originally triggered the emotional state. Our findings are consistent with previous studies showing that individuals with AD have relatively preserved emotion (Blessing et al, 2006, 2012; Evans-Roberts and Turnbull, 2011). However, our study goes beyond assessing the implicit learning of emotional information and demonstrates that patients with AD are profoundly impacted emotionally by events that they cannot recall. In other words, their feelings persist long after the memories have vanished. Thus, patients with AD exhibit the same phenomenon of “feelings without memory” that we had observed in patients with hippocampal amnesia (Feinstein et al, 2010).

The patients with AD also showed another pattern similar to the patients with hippocampal amnesia: Those patients who had the worst memory for the sad films tended to experience the most prolonged states of sadness (Figures 3 and 4). This counterintuitive finding suggests that a free-floating state of negative emotion, untethered from the original emotion-inducing memory, might be particularly difficult to manage.

This difficulty may stem from the adaptive value of knowing the cause of our negative emotions, which in turn can help expedite our recovery from them. A free-floating state of emotion, especially a negative emotion, triggers a search process aimed at discovering the source of the emotional disturbance (Feinstein, 2013). Unfortunately, the amnesia in patients with AD prevents them from being able to make any conclusive discovery. Their inability to attribute the source of the aberrant emotional state draws further attention to it, in effect creating a positive feedback loop that hijacks the natural recovery process and ultimately leads to an abnormally prolonged state of emotion.

For example, near the end of the post-induction period in this study, a patient with AD who had no recollection for any of the sad films stated, “I feel like all my emotions and feelings are rushing in on me. It’s extremely confusing and I do not like that feeling.” The persistence of this patient’s intense negative emotion and her inability to conjure up a logical explanation for the cause of her feelings illustrate the bewilderment that a patient with AD may experience in the face of an apparently inexplicable feeling.

Other patients reported remembering that something sad had happened but could not recall details about the source of their sadness. One patient said, “They showed so much heartache. I don’t recall seeing joy, just pain and heartache”; again, she could not provide any details. Her reaction echoes research showing that patients with AD may have “source amnesia,” ie, they can recall information but not where, how, or under what circumstances they learned it (Dalla Barba et al, 1999).

Our findings support the idea that the neural systems underlying emotional processing and feeling may be relatively preserved in individuals with AD, especially during the early stages. Previous research has shown that amygdala volumes are positively associated with emotional memory (Adolphs et al, 1997; Cahill et al, 1995; Hamann et al, 1997; Mori et al, 1999). Thus, it is possible that our study patients with AD who sustained the induced emotion may have relatively preserved amygdala function. Understanding the neuroanatomic underpinnings of the ability to sustain an emotion deserves further research, and our laboratory is currently working on this topic.

Our study had several limitations. First, our sample size was only moderate. However, both our individual cases and group means demonstrated that patients with AD can experience feelings for an extended period of time despite impaired declarative memory for what caused the feelings.

Second, our data on feelings were derived from self-report. It could be argued that patients with AD might have difficulty comprehending the questions and identifying their feelings (Sturm and Levenson, 2011). However, several points argue against this as a major explanation of our findings. First, before accepting the patients with AD into the study, we carefully tested them with neuropsychological measures to ensure that they had adequate comprehension to perform the study procedures. Second, the AD group and the healthy comparison group reported similar intensities of induced sadness or happiness, and both groups reported a concomitant decrease in positive affect when their negative affect increased after the sadness induction (Figure 2B), suggesting that the patients were rating their feelings reliably and validly. Third, while watching the films, the patients displayed emotional behaviors, such as crying or laughing, that were consistent with the feelings that they later reported. Previous studies looking at emotional reactivity in patients with AD have also shown preserved facial responses to emotional film clips (Mograbi et al, 2012; Smith, 1995).

A final limitation of our study was that the happy films were not as effective as the sad films at inducing strong emotions. This pattern is in keeping with a common trend in the literature. Inducing happiness in the laboratory is challenging, and negative emotions are generally reported to be more salient than positive emotions (Gerrards-Hesse et al, 1994; Monteil and Francois, 1998). One possible explanation for the difficulty of inducing happiness in the laboratory is that participants tend to report high levels of happiness at baseline (Gerrards-Hesse et al, 1994; Monteil and Francois, 1998). This explanation is consistent with our findings.

Our study highlights the fact that actions toward patients with AD have consequences, even when the patients do not appear to remember the actions. In fact, actions may have a lasting impact on how the patients feel. Older adults in nursing homes and patients with AD can be victims of both verbal and physical mistreatment by staff or caregivers (Schiamberg et al, 2012; VandeWeerd et al, 2006, 2013). Such mistreatment may explain in part the increases in psychiatric symptoms and feelings of loneliness seen in people who have moved into a nursing home (Karakaya et al, 2009; Scocco et al, 2006).

Our findings suggest that even though patients with AD may not remember instances of maltreatment, they can still experience the negative emotions triggered by such events. The fact that these patients’ feelings can persist, even in the absence of memory, highlights the need to avoid causing negative feelings and to try to induce positive feelings with frequent visits and social interactions, exercise, music, dance, jokes, and serving patients their favorite foods. Thus, our findings should empower caregivers by showing them that their actions toward patients really do matter and can significantly influence a patient’s quality of life and subjective well-being.

The fact that forgotten events can continue to exert a profound influence on a patient’s emotional life should be applied to the standard of care in nursing homes and assisted living facilities, and implemented by all caregivers. Jade Angelica (2013) has proposed that caregivers should not try to make patients conform to our version of “reality” because such efforts can leave patients feeling upset and confused. Instead, caregivers should try to view reality from the patient’s perspective and approach the patient with empathy. By adopting an attitude of acceptance and giving patients constant reassurance and positive affirmation, caregivers can potentially induce prolonged states of positive emotion while minimizing negative emotion and instances of noncompliant and aggressive behavior. Similarly, because positive feelings can persist, caregivers should be encouraged to continue interventions such as social dancing (Palo-Bengtsson and Ekman, 2002) and therapeutic games (Cohen et al, 2009).

Despite the considerable amount of research aimed at developing disease-modifying pharmacotherapies for AD, no drug has succeeded at either preventing or substantially influencing the disease’s progression. Against this foreboding backdrop, we would like to suggest that more resources be devoted to the research and dissemination of caregiving techniques that could improve the well-being and minimize the suffering for the millions of individuals afflicted with AD (Angelica, 2013; Edvardsson et al, 2012; Thies et al, 2013). Such a paradigm shift will become even more imperative as the population continues to age and the number of patients with AD rises to epidemic proportions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Karen Peralta, Ganna Savranska, Samantha Korns, and Emily Eilers for help with data collection and management; Jade Angelica for valuable comments; the staff at the Benton Neuropsychology Laboratory and the Alzheimer’s Association for assisting with recruitment; Oliver Turnbull and Daniel Mograbi for their perceptive reviews; and Don Fowles for his insightful comment that became the catalyst for this line of inquiry.

APPENDIX 1

Footnotes

The sadness and happiness inductions can be obtained for research purposes from coauthor Justin S. Feinstein at jfeinstein@laureateinstitute.org.

Supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant P01 NS19632 (D.T.), the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program under Grant 1048957 (E.G.-V.), Kiwanis International, the Fraternal Order of Eagles, an American Psychological Association of Graduate Students Basic Psychological Research Grant, and the William K. Warren Foundation.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Adolphs R, Cahill L, Schul R, et al. 1997. Impaired declarative memory for emotional material following bilateral amygdala damage in humans. Learn Mem. 4:291–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelica JC. 2013. Where Two Worlds Touch: A Spiritual Journey Through Alzheimer’s Disease. Boston, Massachusetts: Skinner House Books [Google Scholar]

- Blessing A, Keil A, Gruss LF, et al. 2012. Affective learning and psychophysiological reactivity in dementia patients. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2012:1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blessing A, Keil A, Linden DE, et al. 2006. Acquisition of affective dispositions in dementia patients. Neuropsychologia. 44:2366–2373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broster LS, Blonder LX, Jiang Y. 2012. Does emotional memory enhancement assist the memory-impaired? Front Aging Neurosci. 4:1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucks RS, Radford SA. 2004. Emotion processing in Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Ment Health. 8:222–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L, Babinsky R, Markowitsch HJ, et al. 1995. The amygdala and emotional memory. Nature. 377:295–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen GD, Firth FM, Biddle S, et al. 2009. The first therapeutic game specifically designed and evaluated for Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 23:540–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Cohen J, Aiken L, et al. 1999. The problem of units and the circumstance for POMP. Multivar Behav Res. 34:315–346 [Google Scholar]

- Dalla Barba G, Nedjam Z, Dubois B. 1999. Confabulation, executive functions, and source memory in Alzheimer’s disease. Cogn Neuropsychol. 16:385–398 [Google Scholar]

- DeRenzo EG, Conley RR, Love RC. 1998. Assessment of capacity to give consent to research participation: state-of-the-art and beyond. J Health Care Law Policy. 1:66–87 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edvardsson D, Sandman PO, Rasmussen B. 2012. Forecasting the ward climate: a study from a dementia care unit. J Clin Nurs. 21:1136–1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Roberts CE, Turnbull OH. Remembering relationships: preerved emotion-based learning in Alzheimer’s disease. 2011. Exp Aging Res. 37:1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein JS. 2013. Lesion studies of human emotion and feeling. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 23:304–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein JS, Duff MC, Tranel D. 2010. Sustained experience of emotion after loss of memory in patients with amnesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 107:7674–7679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming K, Kim SH, Doo M, et al. 2003. Memory for emotional stimuli in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 18:340–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NC, Crum WR, Scahill RI, et al. 2001. Imaging of onset and progression of Alzheimer’s disease with voxel-compression mapping of serial magnetic resonance images. Lancet. 358:201–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrards-Hesse A, Spies K, Hesse FW. 1994. Experimental inductions of emotional states and their effectiveness: a review. Br J Psychol. 85:55–78 [Google Scholar]

- Goodglass H, Kaplan E, Barresi B. 2000. The Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination (BDAE-3). 3rd edSan Antonio, Texas: Pearson [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Levenson RW. 1995. Emotion elicitation using films. Cogn Emotion. 9:87–108 [Google Scholar]

- Hamann SB, Cahill L, McGaugh JL, et al. 1997. Intact enhancement of declarative memory for emotional material in amnesia. Learn Mem. 4:301–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann SB, Monarch ES, Goldstein FC. 2000. Memory enhancement for emotional stimuli is impaired in early Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology. 14:82–92 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman BT, Van Hoesen GW, Damasio AR, et al. 1984. Alzheimer’s disease: cell-specific pathology isolates the hippocampal formation. Science. 225:1168–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman BT, Van Hoesen GW, Damasio AR. 1990. Memory-related neural systems in Alzheimer’s disease: an anatomic study. Neurology. 40:1721–1730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Jr, Petersen RC, Xu YC, et al. 1997. Medial temporal atrophy on MRI in normal aging and very mild Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 49:786–794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakaya MG, Bilgin SÇ, Ekici G, et al. 2009. Functional mobility, depressive symptoms, level of independence, and quality of life of the elderly living at home and in the nursing home. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 10:662–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazui H, Mori E, Hashimoto M, et al. 2000. Impact of emotion on memory: controlled study of the influence of emotionally charged material on declarative memory in Alzheimer’s disease. Br J Psychiatry. 177:343–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kensinger EA, Brierly B, Medford N, et al. 2002. Effects of normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease on emotional memory. Emotion. 2:118–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magai C, Cohen C, Gomberg D, et al. 1996. Emotional expression during mid- to late-stage dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 8:383–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. 2011. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 7:263–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mickes L, Wixted JT, Fennema-Notestine C, et al. 2007. Progressive impairment on neuropsychological tasks in a longitudinal study of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology. 21:696–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moayeri SE, Cahill L, Jin Y, et al. 2000. Relative sparing of emotionally influenced memory in Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroReport. 11:653–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mograbi DC, Brown RG, Morris RG. 2012. Emotional reactivity to film material in Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 34:351–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteil JM, Francois S. 1998. Asymmetry and time span of experimentally induced mood. Curr Psychol Cogn. 17:621–633 [Google Scholar]

- Mori E, Ikeda M, Hirono N, et al. 1999. Amygdalar volume and emotional memory in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 156:216–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC. 1993. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current vision and scoring rules. Neurology. 43:2412–2414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narme P, Mouras H, Roussel M, et al. 2013. Assessment of socioemotional processes facilitates the distinction between frontotemporal lobar degeneration and Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 35:728–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nashiro K, Mather M. 2011. Effects of emotional arousal on memory binding in normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychol. 124:301–312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palo-Bengtsson L, Ekman S. 2002. Emotional response to social dancing and walks in persons with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 17:149–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippot P. 1993. Inducing and assessing differentiated emotion-feeling states in the laboratory. Cogn Emotion. 7:171–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM. 1958. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept Mot Skills. 8:271–276 [Google Scholar]

- Rottenberg J, Ray R, Gross J.Coan JA, Allen JJ. 2007. Emotion elicitation using films. Handbook of Emotion Elicitation and Assessment. New York, New York: Oxford University Press;9–28 [Google Scholar]

- Sabat SR, Collins M. 1999. Intact social, cognitive ability, and selfhood: a case study of Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 14:11–19 [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer A, Nils F, Sanchez X, et al. 2010. Assessing the effectiveness of a large database of emotion-eliciting films: a new tool for emotion researchers. Cogn Emot. 24:1153–1172 [Google Scholar]

- Schiamberg LB, Oehmke J, Zhang Z, et al. 2012. Physical abuse of older adults in nursing homes: a random sample survey of adults with an elderly family member in a nursing home. J Elder Abuse Negl. 24:65–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M. 1996Rey Auditory and Verbal Learning Test: A Handbook. Los Angeles, California: Western Psychological Services [Google Scholar]

- Scocco P, Rapattoni M, Fantoni G. 2006. Nursing home institutionalization: a source of eustress or distress for the elderly? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 24:281–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MC. 1995. Facial expression in mild dementia of the Alzheimer type. Behav Neurol. 8:149–156 [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, et al. 1983. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, California: Consulting Psychologists Press [Google Scholar]

- Sturm VE, Levenson RW. 2011. Alexithymia in neurodegenerative disease. Neurocase. 17:242–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thies W, Bleiler L. Alzheimer’s Association. 2013. Alzheimer’s Association facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 9:208–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VandeWeerd C, Paveza GJ. 2006. Verbal mistreatment in older adults: a look at persons with Alzheimer’s disease and their caregivers in the state of Florida. J Elder Abuse Negl. 17:11–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VandeWeerd C, Paveza GJ, Walsh M, et al. 2013. Physical mistreatment in persons with Alzheimer’s disease. J Aging Res. 2013:1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, O’Hara MW, Chmielewski M, et al. 2008. Further validation of the IDAS: evidence of convergent, discriminant, criterion, and incremental validity. Psychol Assess. 20:248–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. 2008. WAIS-IV Administration and Scoring Manual. San Antonio, Texas: The Psychological Corporation [Google Scholar]