Abstract

The quadriceps tendon (QT) as a graft source for anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction has recently achieved increased attention. Although many knee surgeons have been using the QT as a graft for ACL revision surgery, it has never gained universal acceptance for primary ACL reconstruction. The QT is a very versatile graft that can be harvested in different widths, thicknesses, and lengths. Conventionally, the QT graft is harvested by an open technique, requiring a 6 to 8 cm longitudinal incision, which often leads to unpleasant scars. We describe a new, minimally invasive, standardized approach in which the QT graft can be harvested through a 2- to 3-cm skin incision and a new option of using the graft without a bone block.

The quadriceps tendon (QT) as a graft source for anterior cruciate ligament (ACL)1-5 and posterior cruciate ligament (PCL)6 reconstruction has recently achieved increased attention. Although many knee surgeons have been using the QT as a graft for ACL revision surgery,7,8 it has never gained universal acceptance for primary ACL reconstruction. The main reason, in our opinion, is that QT graft harvest is technically more demanding and a scar on the thigh is cosmetically less favorable, despite excellent clinical results in the literature.3,9-13 In the late 1990s Stäubli et al.,14,15 from Switzerland, published anatomic and biomechanical details of the QT and were the first advocates of its use as a primary ACL graft. Excellent clinical outcomes have been documented for the use of the QT in ACL revision surgery as well.7,8 The QT has also been successfully used for PCL reconstruction.6

The QT is a very versatile graft that can be harvested in different widths, thicknesses, and lengths and can be used with or without a bone block. If a preoperative magnetic resonance imaging study is available, it is helpful to examine the QT and evaluate the thickness.16,17 Conventionally, the QT graft is harvested by an open technique, requiring a 6 to 8 cm longitudinal incision.18 We present a new, minimally invasive, standardized approach in which the QT graft can be harvested through a 2 to 3 cm skin incision and a new option of using the graft without a bone block.

Surgical Technique

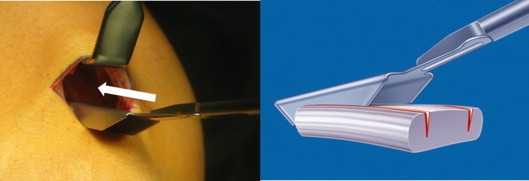

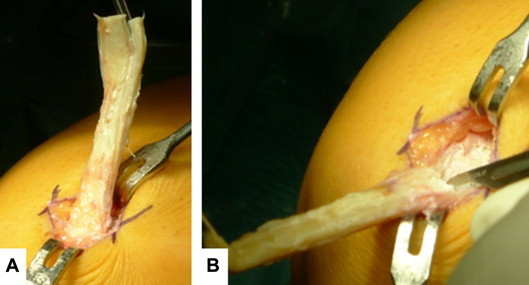

In 90° of knee flexion, a 2.5 to 3 cm transverse skin incision (alternatively, a 3 cm longitudinal incision) is placed over the superior border of the patella. The prepatellar bursa is incised longitudinally, and the QT is then carefully exposed (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Skin incisions. A 2.5 to 3 cm transverse skin incision (solid line) may be recommended for the best cosmetic result. Alternatively, a 2.5 to 3 cm longitudinal incision (dotted line) may be used.

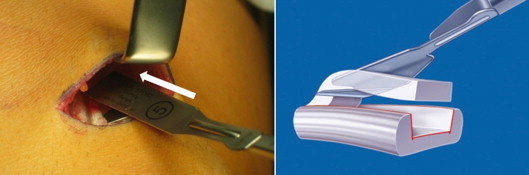

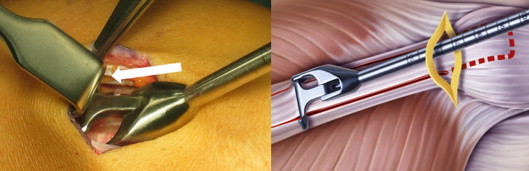

A long Langenbeck retractor is introduced, and the QT is subcutaneously exposed proximal to the patella. A double knife (Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany) 8 to 12 mm in width is then introduced, starting in the middle or slightly lateral to the middle of the superior patellar border and pushed up to a minimum of 6 cm (if used with bone block for ACL or 8 cm for PCL) (Fig 2). The thickness of the graft (5 mm) is determined using a tendon separator (Karl Storz). The knife is pushed proximal to the same mark (Fig 3). Finally, the tendon strip is cut subcutaneously by a special tendon cutter (Karl Storz) (Fig 4), and the graft is retrieved through the skin incision.

Fig 2.

A double knife is introduced starting slightly lateral to the middle of the superior patellar border11,18 and pushed up (white arrow) to the desired tendon length. There are centimeter markings on the instrument.

Fig 3.

Graft thickness is determined using a 5 mm tendon separator. The tendon separator is then pushed proximally (white arrow) to the previously determined length. There are centimeter markings on the instrument.

Fig 4.

The tendon strip is cut subcutaneously by a special tendon cutter at the determined length (white arrow).

There are 2 options at this point: QT with a bone block and QT without a bone block (Table 1).

Table 1.

Pros and Cons of Bone Block Use

| Bone block |

| Pro: quicker graft-to-tunnel healing |

| Con: risk of patellar fracture |

| Soft-tissue graft |

| Pros: No fracture risk; may be used in case of open physes |

| Con: slower graft-to-tunnel healing |

Option 1: QT With Bone Block

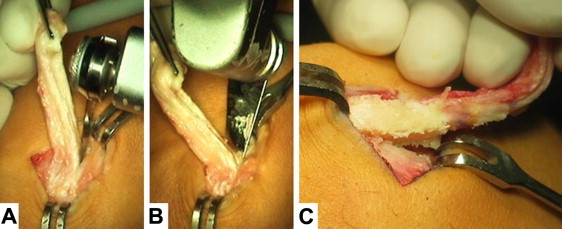

The tendon strip is elevated and then followed distally to its bony attachment. The dimensions of the bone block (1.5 to 2 cm in length and respective graft width) are outlined. The bone cuts are made with an oscillating saw, starting with the longitudinal cuts. The graft is then elevated, and the final cut determining the thickness of the bone block is made from proximal to distal. The bone block is then easily elevated with a chisel (Fig 5). All the steps of the harvesting procedure are summarized in Video 1. These steps avoid extensive use of the chisel and hammer to remove the block and reduce the risk of a patellar fracture.

Fig 5.

The bone block is harvested using an oscillating saw. (A) First, the longitudinal and transverse cuts are made. (B) The last cut determines the thickness of the bone block and is made from proximal to distal. (C) Finally, the block is easily elevated.

We recommend harvesting the bone block last. Harvesting the bone block first is commonly associated with taking an unnecessary amount of bone, as well as an increased risk of opening the joint capsule.

The bone block is prepared to the appropriate size, and one or two 1.5 mm holes are drilled through. We prefer to use a square bone block rather than a round bone block.2,19 The bone block can then be fixed to a flip-button device (e.g., EndoButton [Smith & Nephew, Andover, MA]) by strong nonresorbable sutures (e.g., No. 2 FiberWire [Arthrex, Naples, FL]) or by only a resorbable pullout suture if it is fixed later with an interference screw.

Option 2: QT Without Bone Block

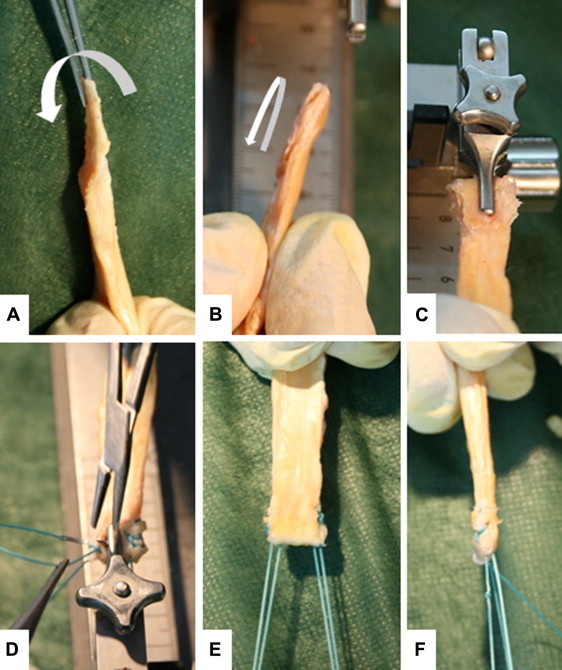

The tendon strip is elevated and then followed distally to its bony attachment. The parallel longitudinal cuts are continued with a surgical knife toward the patella and 2 cm over the patellar surface. The QT graft is then subperiosteally elevated from the surface of the patella (Fig 6) and detached. The periosteal part of the graft is folded in the middle, and web-stitch sutures are placed on each side of the graft using strong No. 2 suture (e.g., No. 2 FiberWire) (Fig 7). This will result in a smooth, round end of the graft, which allows easier graft passage. It also gains about 1 cm of additional graft length. Both aspects are a major point for using the QT for PCL reconstruction. The sutures are then passed through a flip-button device (e.g., EndoButton) for later fixation. Alternatively, a soft-tissue interference screw may be used for femoral fixation.

Fig 6.

(A) After retrieving the QT graft, it is pulled distally, and (B) a strip of periosteum in the appropriate width is detached about 2 cm in length.

Fig 7.

Graft preparation without bone block. (A) Final graft with strip of periosteum measuring approximately 2 cm. (B) The periosteum is folded in the middle and (C) fixed in the clamp of a preparation board. (D) Web-stitch sutures are placed on each side of the graft using nonresorbable No. 2 suture material. (E, F) This results in a smooth, round end of the graft, which allows easy graft passage.

Closing Tendon Defect

A long Langenbeck retractor is reintroduced, and the tendon defect is closed. The stitches should be placed in the superficial aspect of the tendon to avoid shortening of the tendon (“fan-like closure”). The prepatellar bursa is carefully closed over a bony defect.

Discussion

QT harvest, following the aforementioned steps, is a safe and reliable procedure (Table 2). By use of this minimally invasive technique, the cosmetic outcome can be markedly improved and the surgical time reduced compared with conventional open harvesting techniques. As a soft-tissue graft, it may also be used in children with open physes.

Table 2.

Potential Complications

| Graft is too short |

| Inspect the QT before harvesting to look for the longest tendon part (the surgeon may place the arthroscope in the skin incision). |

| Start harvesting slightly lateral to the center of the proximal border of the patella. |

| Angle the double knife and the tendon separator approximately 30° to the QT to avoid early cutout. |

| As a solution, use a different graft; note that in some cases, a second QT graft can be harvested adjacent to the first. |

| Patellar fracture |

| Avoid forceful action with the chisel and hammer to the front of the patella. |

| As a solution, perform ORIF (with 2 cannulated small-fragment screws). |

ORIF, open reduction–internal fixation.

Whether the use of a bone block is advantageous over the use of the QT as a pure soft-tissue graft has yet to be established. The use of a periosteal strip was found to facilitate graft passage through the tunnels. Theoretically, the use of a periosteal tendon part might also lead to improved tendon-to-bone healing compared with a QT graft that is simply cut proximal to the patella.

We think that improving and simplifying QT harvest will make this graft increasingly attractive not only for revision but also for primary ACL/PCL reconstruction.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Caroline Hepperger from the OSM Research Foundation for helping to prepare the manuscript. The authors thank Karl Storz (Tuttlingen, Germany) for providing Figures 2-4.

Footnotes

The authors report the following potential conflict of interest or source of funding: C.F. receives support from Karl Storz, DePuy Mitek, Smith & Nephew. M.H. receives support from OSM Research Foundation, Biotissue, Karl Storz.

Supplementary Data

Surgical technique for minimally invasive harvesting of QT graft: A 5 mm-thick and 10 mm wide strip of QT is harvested subcutaneously using special instrumentation from Karl Storz. The graft is harvested with a bone block from the patella in the appropriate dimensions.

References

- 1.Akoto R., Hoeher J. Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction with quadriceps tendon autograft and press-fit fixation using an anteromedial portal technique. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;27:161. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-13-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fink C., Hoser C. Einzelbündeltechnik: Quadrizepssehne in Portaltechnik. Arthroskopie. 2013;26:35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoeher J., Balke M., Albers M. Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction using a quadriceps tendon autograft and press-fit fixation has equivalent results compared to a standard technique using semitendinosus graft: A prospective matched-pair analysis after 1 year. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20:147. (abstr) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lund B., Nielsen T., Faunø P. Is quadriceps tendon a better graft choice than patellar tendon? A prospective randomized study. Arthroscopy. 2014;30:593–598. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sasaki N., Farraro K.F., Kim K.E. Biomechanical evaluation of the quadriceps tendon autograft for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:723–730. doi: 10.1177/0363546513516603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zayni R., Hager J.P., Archbold P. Activity level recovery after arthroscopic PCL reconstruction: A series of 21 patients with a mean follow-up of 29 months. Knee. 2011;18:392–395. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forkel P., Petersen W. Anatomic reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament with the autologous quadriceps tendon: Primary and revision surgery. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2014;26:30–42. doi: 10.1007/s00064-013-0261-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garofalo R., Djahangiri A., Siegrist O. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with quadriceps tendon-patellar bone autograft. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorschewsky O., Klakow A., Putz A. Clinical comparison of the autologous quadriceps tendon (BQT) and the autologous patella tendon (BPTB) for the reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:1284–1292. doi: 10.1007/s00167-007-0371-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim S.J., Kumar P., Oh K.S. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: Autogenous quadriceps tendon-bone compared with bone-patellar tendon-bone grafts at 2-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2009;25:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee S., Seong S.C., Jo H. Outcome of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using quadriceps tendon autograft. Arthroscopy. 2004;20:795–802. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mulford J.S., Hutchinson S.E., Hang J.R. Outcomes for primary anterior cruciate reconstruction with the quadriceps autograft: A systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21:1882–1888. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2212-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schulz A.P., Lange V., Gille J. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using bone plug-free quadriceps tendon autograft: Intermediate-term clinical outcome after 24-36 months. Open Access J Sports Med. 2013;19:243–249. doi: 10.2147/OAJSM.S49223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stäubli H., Bollmann C., Kreutz R. Quantification of intact quadriceps tendon, quadriceps tendon insertion, and suprapatellar fat pad: MR arthrography, anatomy, and cryosections in the sagittal plane. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173:691–698. doi: 10.2214/ajr.173.3.10470905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stäubli H., Schatzmann L., Brunner P. Mechanical tensile properties of the quadriceps tendon and patellar ligament in young adults. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27:27–34. doi: 10.1177/03635465990270011301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iriuchishima T., Shirakura K., Yorifuji H. Anatomical evaluation of the rectus femoris tendon and its related structures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132:1665–1668. doi: 10.1007/s00402-012-1597-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xerogeanes J.W., Mitchell P.M., Karasev P.A. Anatomic and morphological evaluation of the quadriceps tendon using 3-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging reconstruction: Applications for anterior cruciate ligament autograft choice and procurement. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:2392–2399. doi: 10.1177/0363546513496626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lippe J., Armstrong A., Fulkerson J.P. Anatomic guidelines for harvesting a quadriceps free tendon autograft for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2012;28:980–984. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herbort M., Tecklenburg K., Zantop T. Single-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A biomechanical cadaveric study of a rectangular quadriceps and bone–patellar tendon–bone graft configuration versus a round hamstring graft. Arthroscopy. 2013;29:1981–1990. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2013.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Surgical technique for minimally invasive harvesting of QT graft: A 5 mm-thick and 10 mm wide strip of QT is harvested subcutaneously using special instrumentation from Karl Storz. The graft is harvested with a bone block from the patella in the appropriate dimensions.