Abstract

To overcome cardiovascular disease (CVD) disparities impacting high-risk populations, it is critical to train researchers and leaders in conducting community-engaged CVD disparities research. The authors summarize the key elements, implementation, and preliminary outcomes of the CVD Disparities Fellowship and Summer Internship Programs at the Johns Hopkins University Schools of Medicine, Nursing, and Bloomberg School of Public Health.

In 2010, program faculty and coordinators established a trans-disciplinary CVD disparities training and career development fellowship program for scientific investigators who desire to conduct community-engaged clinical and translational disparities research. The program was developed to enhance mentorship support and research training for faculty, post-doctoral fellows, and pre-doctoral students interested in conducting CVD disparities research. A CVD Disparities Summer Internship Program for undergraduate and pre-professional students was also created to provide a broad experience in public health and health disparities in Baltimore, Maryland, with a focus on CVD. Since 2010, 39 pre-doctoral, post-doctoral, and faculty fellows have completed the program. Participating fellows have published disparities-related research and given presentations both nationally and internationally. Five research grant awards have been received by faculty fellows. Eight undergraduates, 1 post-baccalaureate, and 2 medical professional students representing seven universities have participated in the summer undergraduate internship. Over half of the undergraduate students are applying to or have been accepted into medical or graduate school. The tailored CVD health disparities training curriculum has been successful at equipping varying levels of trainees (from undergraduate students to faculty) with clinical research and public health expertise to conducting community-engaged CVD disparities research.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) accounts for approximately one-third of the excess overall mortality in African Americans in the United States, in large part because of disparities in hypertension prevalence and control rates with care.1-6 Barriers to CVD risk factor control exist at multiple levels, including individual socio-demographic factors and risk behaviors, as well as in the social, environmental (e.g., neighborhood stability), and healthcare (e.g., access to care) contexts.7,8 There is an urgent need to comprehensively integrate the best evidence-based, sustainable, multi-level strategies to overcome CVD disparities and to translate them into clinical and public health practice using a community engaged approach. To accomplish this goal, it is critical to train the next generation of CVD health disparities researchers, equipping them with clinical research and public health expertise in the areas of social epidemiology, health services research, health policy, community-based participatory research (CBPR), and implementation science. Advanced training in these disciplines will give disparities researchers expertise in rigorous measurement and analysis of physical and social environment exposures as contributors to health disparities (social epidemiology); examination of health care and health system contributors to disparities and designing multi-level health system preventive interventions (health services research); promotion of culturally sensitive, effective, and sustainable interventions through community and academic partnership (CBPR); and integration of research findings into healthcare practice and policy (implementation science). With this in mind, we developed a CVD health disparities research training program for faculty, post-doctoral fellows, pre-doctoral students, health professions students, and undergraduate students through the Training Core of our National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute-funded Johns Hopkins Center to Eliminate Cardiovascular Health Disparities.9

CVD Disparities Fellowship for Faculty, Post-doctoral Fellows, and Pre-doctoral Students

Program overview

We established a trans-disciplinary collaboration across the Johns Hopkins University Schools of Medicine, Nursing, and Bloomberg School of Public Health (JHBSPH), to create a CVD disparities training and career development fellowship program for investigators who desire to be engaged in clinical and translational research. Disciplines represented in the Center to Eliminate Cardiovascular Health Disparities are medicine, nursing, psychology, pharmacy, nutrition, epidemiology, biostatistics, behavioral science, communications, health services research, health economics, organizational behavior, and community development. Our program was developed by the center faculty, with input from the initial trainees selected in 2010, to enhance mentorship support and research training for faculty (MDs and PhDs), post-doctoral fellows (MDs and PhDs, often trainees from other formal programs within our institution), and pre-doctoral students (both at the doctoral and master’s levels) interested in better understanding the causes of and identifying sustainable solutions to overcome CVD disparities. Established in 2010, the program recruits up to three pre- and post-doctoral fellows annually and two to three faculty members every other year. Senior faculty members (associate and full professors) are considered only if CVD health disparities research represents a new career path for them.

Our fellowship program, which complements and extends our trainees’ formal programs, has three key goals: to offer specialized training in CVD disparities to individuals already participating in established training programs; to provide mentoring from senior faculty with expertise in five core research areas (cardiovascular epidemiology; health services research; behavioral sciences; health disparities and social epidemiology; and CBPR); and to provide funds to support CVD disparities projects for all fellows and salary support for faculty fellows. Although the program does not currently culminate with a certificate, our trainees are able to list participation in the Center’s training program and the research funding support received on their curriculum vitae as important indicators of their academic potential.

Program eligibility and entrance requirements

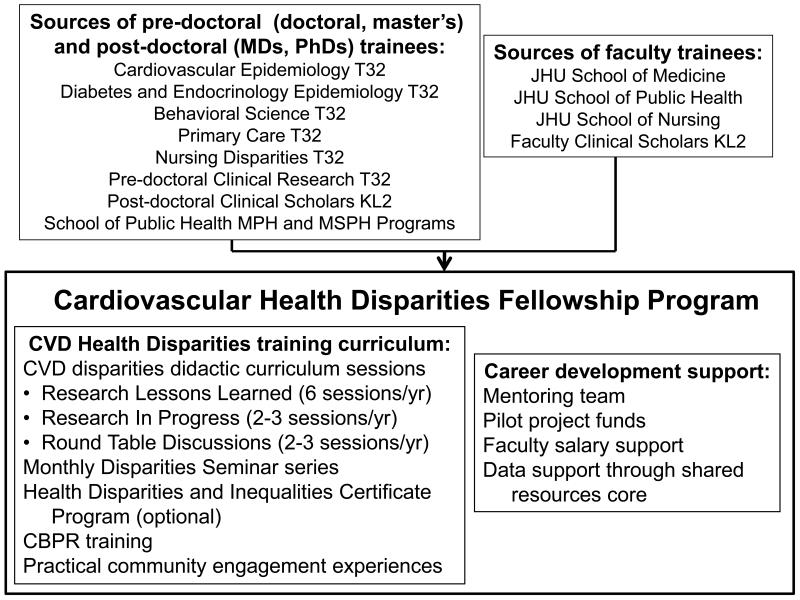

Our fellowship program recruits pre-doctoral students and post-doctoral fellows at Johns Hopkins University who are primarily supported by another research training grant, enrolled in a JHBSPH graduate program, or currently participating in other clinical research training programs (see Figure 1). We have also accepted a pre-doctoral trainee for a disparities internship from an outside institution. Full-time faculty members at Johns Hopkins University with dedicated research time are also eligible to apply. Prospective applicants identify a mentor with clinical research and/or health disparities research experience. Applicants also submit a personal statement addressing background information relevant to the trainee’s interest in one of the center’s five core program areas, past research experiences, long-term career goals, and a description of how the training program is relevant to advancing these goals. Additionally, applicants must provide a description of a proposed CVD disparities-oriented research project that would be conducted if selected. Finally, we require a letter of support from the applicant’s existing training grant director, academic program director, or (for faculty applicants) division chief, indicating a commitment to supporting and allowing time and effort needed to complete our focused training program. Criteria for selection of candidates include outstanding past performance, career objectives demonstrating a commitment to CVD disparities research, and documentation of strong support from the primary mentor.

Figure 1.

Cardiovascular Health Disparities Fellowship Program recruitment sources and career development components, Johns Hopkins Center to Eliminate Cardiovascular Health Disparities. Abbreviations: CVD = cardiovascular disease; CBPR = Community-based participatory research; MPH = Masters of Public Health; MSPH = Masters of Science in Public Health; JHU = Johns Hopkins University.

CVD disparities training curriculum

The first goal of our program is to offer CVD disparities training via participation in the following five didactic and practical components. The didactic curriculum sessions were developed by center faculty with expertise in health disparities research, social epidemiology and social determinants of health, methods for community and organizational engagement in disparities research, and behavioral science. The center also conducted a focus group with first class of trainees selected in 2010 to determine the best session formats and the topics of interest in health disparities research not addressed in their formal training programs, which was instrumental in shaping the final curriculum.

CVD disparities didactic curriculum sessions

The center developed a monthly CVD disparities didactic curriculum for trainees, which encompasses a multimodal format of sessions and covers a range of topics throughout the academic year. Fellows are required to attend at least nine of twelve sessions during their fellowship year and we monitor attendance. The curriculum consists of three types of sessions:

Research Lessons Learned (6 per year): These sessions are presented by center faculty and research staff and are interactive in nature, which allows fellows to grasp an understanding of practical issues in conducting health disparities research. The specific objectives for each session are summarized in Table 1.

Research in Progress (2–3 per year): Current pre-doctoral, post-doctoral, and faculty fellows present updates on their center-supported CVD disparities-oriented research projects. The center’s core faculty members and each trainee’s primary mentor attend the session to provide guidance and constructive feedback.

Roundtable Discussions (2–3 per year): We also hold periodic roundtable group sessions with internationally-recognized senior investigators from outside institutions in the field of CVD disparities research.

Table 1. Learning Objectives of CVD Disparities Fellowship Research Lessons Learned Curriculum Sessions, Johns Hopkins Center to Eliminate Cardiovascular Health Disparities.

| Lessons Learned topic | Objectives |

|---|---|

| Addressing cultural competence and communication skills in health disparities research |

Describe barriers and promoters to participation in research by diverse groups |

Discuss how researchers can use communication skills and cultural competence to:

| |

|

| |

| Addressing ethical and safety issues conducting health disparities research |

To learn how to develop a safety alerts algorithm for abnormal blood pressure and laboratory values that arise during screening and/or conduct of a patient-oriented cardiovascular disparities research study |

| To learn how to recognize and follow-up on mental health safety concerns, using depression screening as an example, that may arise during the screening and/or conduct of a patient-oriented disparities research study |

|

| To learn how to develop and execute an algorithm for medication adjustment for pharmacological interventions in patient-oriented cardiovascular disparities research |

|

|

| |

| Selecting and training staff for health disparities research |

To know how to write a job description for project- specific staffing in conducting health disparities research To know how to review and select candidates to interview for health disparities research

|

| To know how to assess cultural competence of potential staff members during the job interview |

|

| To know important aspects of job offers, on boarding and training of new staff for health disparities research |

|

| To know how to evaluate staff performance, recognize good performance, and provide feedback/corrective action |

|

|

| |

| Developing assessment and intervention materials for health disparities research and research in underserved populations |

Discuss the role of culture, language, literacy, beliefs, attitudes, in individuals’ perceptions of health and illness, stress and coping, help-seeking behaviors, and decision making |

| Identify effective strategies for cultural and linguistic targeting in intervention materials |

|

| Provide examples of cultural and linguistic targeting |

|

| Explain how targeting and tailoring can be combined to acknowledge individual differences when designing population-level interventions |

|

|

| |

| Generating community support for health disparities research |

Develop understanding of the relevance of community engagement in all phases of research |

| Identify methods for community engagement in all phases of research |

|

|

| |

| Generating organizational support for healthcare disparities research |

Describe how to use the System Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) framework14 for conceptualizing barriers and promoters to implementation of interventions |

| Provide at least 1 example of each of the following concepts from the SEIPS model: person, organization, physical environment, task, tools/technology |

|

| Describe Herzberg and colleagues’ “Two-factor” theory15 and how it applies to workplace motivation List at least 3 factors that motivate clinicians |

|

Abbreviations: CVD = cardiovascular disease.

Johns Hopkins Health Disparities Consortium Monthly Seminar Series

This recommended seminar series is jointly sponsored by the center and by the four other National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded health disparities research centers on our campus. These sessions address and highlight social determinants, health system factors, and health policy factors related to health disparities. Speakers include faculty within our 5 health disparities centers as well as health disparities experts from outside institutions. The center hosts 2-3 speakers annually whose presentations focus on CVD disparities. We also occasionally co-sponsor half-day workshops that include several speakers focused on a themed topic related to health disparities.

Health Disparities and Inequalities Certificate Program

Completion of this certificate program is optional but highly recommended for all fellows in the training program. Offered through JHBSPH, its educational objectives are to train future leaders in research on health disparities and health inequality, to train individuals for leadership in health policy and public health practice on the underlying causes of health inequality, and to prepare public health professionals in known solutions for health disparities and health inequality. A monthly journal club supports the program.

CBPR seminars

Trainees are encouraged to participate in formal courses at JHBSPH which are led by faculty affiliated with the center. Introduction to Community-Based Participatory Research Methods is a 3-credit course where students learn the principles of CBPR; determine the strengths and limitations of CBPR; distinguish how CBPR differs from community-based and basic research; and review case studies. The Graduate Seminar in Community-Based Participatory Research meets twice per month and is an interactive series designed to enhance collaborative CBPR efforts between academic researchers and community leaders.

Practical community engagement experiences

Our trainees engage in several practical community education experiences such as community advisory board meetings, seminars, health fairs, and conferences. For all activities, the focus is to enhance participants’ learning using a range of methods. One example is the ongoing Ask the Expert seminar series created by the School of Medicine’s Office of Community Health and Institute for Clinical and Translational Research in conjunction with pastors and lay health ministry leaders at local churches. Since July 2012, the center’s director and one post-doctoral fellow has given a 1-hour presentation on racial disparities and hypertension at four Baltimore churches. The presentation includes a definition of disparities in CVD and hypertension, sources of these disparities, relevant research findings, and mechanisms to reduce disparities. Approximately 25-30 church members attend each of the sessions and are given the opportunity to ask questions. The center’s participation in this seminar series has been very well received by the local community, and in 2013, this experience was incorporated as a permanent component of our training program. We pair fellows and faculty with complementary clinical and public health backgrounds to present CVD-related topics at these seminars.

Participating fellows can also participate in a community-based service learning experience with one of the center’s community partners. The objectives of this experience are for fellows to deliver direct services to the surrounding community, develop a research partnership, and/or assist the community in organizing for advocacy.

Career development: Mentoring, research funding, and support

In addition to didactic training, the second goal of the fellowship training program is to provide dedicated mentoring from senior faculty with expertise in the center’s five core research areas. Effective mentoring ensures that early career investigators become successful CVD health disparities researchers. Mentors are expected to meet with trainees regularly to choose a topic, plan the literature review, choose the type of project (e.g., secondary data analysis, primary data collection), discuss collaborations, set goals, review instruments, data analysis plans and output, and guide drafting and editing manuscripts and proposals. Each fellow selects a faculty mentor with expertise in one of the five areas in which he or she needs career development. The program also provides faculty and post-doctoral trainees with the opportunity to themselves become mentors to our undergraduate interns, allowing junior trainees to develop their own skills as mentors.

Finally, the third goal of the fellowship program is to provide supplemental research support. Funds are provided to support CVD disparities projects ($5,000/year for all fellows) and salary support for junior and senior faculty ($10,000-$15,000/year for 2 years). Additionally, trainees receive support through the center’s Shared Resources Core, which provides advice and consultation on study design and data analysis, provides infrastructure for data capture and management, and assists in recruitment and retention of research participants for original data collection projects.9

Each year the program received more applicants than it could fund. Consequently, the training core director allowed these individuals who did not receive fellowship funds to participate in the didactic and seminar session with the funded trainees to broaden the reach of the training program.

CVD Disparities Summer Internship Program for Undergraduate and Health Professions Students

Program overview

In 2011, the center initiated a trans-disciplinary summer internship as a result of inquiries to faculty/staff for a summer experience in health disparities. Whereas the fellowship program provides pre- and post-doctoral trainees and faculty with in-depth research training to address CVD disparities, the summer internship for undergraduates and medical students provides participants a broad experience in public health and health disparities. The summer program, however, is linked to the fellowship program in that it gives participating CVD disparities fellows the opportunity to gain mentoring experience under the supervision of center faculty. The overall goal is to expose students to CVD health disparities and public health solutions through participation in clinical, research, and community-based experiences. The learning objectives for our summer students are to:

Explain the center’s mission, function, and organizational structure;

Identify and characterize at least one current CVD disparity issue or opportunity related to the center’s missions, functions, and organizational structure; and

Identify a barrier to resolving health or health care disparities and a potential solution based on a clinical or community-based field experience.

The center limited the number of participants to 3 during the first year of the program to ensure a high-quality experience for the students. After receiving positive feedback, the center expanded the program the second year, admitting 6 enrollees.

Description of program components

The multi-dimensional experience includes rotations at clinical, research, and community sites as well as attendance at a Community Advisory Board (CAB) meeting of the center. The members of the CAB are essential to the success of the summer program, facilitating the preponderance of community-based field experiences for the students. A sample of these experiences is summarized in Table 2. In addition, summer interns were able to attend meetings at the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, which exposed students to statewide public health policy and programs.

Table 2. CVD Disparities Summer Internship Program Community-Based Field Experiences, Johns Hopkins Center to Eliminate Cardiovascular Health Disparities.

| Field experience site | Description |

|---|---|

| Baltimore Medical Systems, Inc. | Federally Qualified Health Center with multiple sites in the city. Students participated in a heart health educational intervention targeting low income African American women at one clinic site and they shadowed community health workers from another clinic site in an urban neighborhood with a large Hispanic population. |

|

| |

| Sisters Together and Reaching (STAR) |

A community based agency that works with women who are at high risk of contracting HIV. Students work with STAR staff to perform HIV outreach and community health education to at risk populations in West Baltimore. |

|

| |

| Charm City Clinic (CCC) | A free clinic staffed by volunteers on Saturdays, CCC is housed at the Men and Families Center, a community based organization domiciled in the neighborhood adjoining the Johns Hopkins Medical Campus. CCC provides basic health screenings and provides its clients with assistance accessing health insurance and support services. Students assisted workers in recruiting patients from the neighborhood for clinic sessions and observed clinic activities. |

|

| |

| Baltimore City Health Department’s Needle Exchange and Overdose Prevention Program |

A program targeting injection drug users composed of both a one-for-one needle exchange (clean syringes for dirty ones) and proactive overdose prevention activities. Students worked with current opiate users: they prepared harm reduction kits, performed outreach, and observed wound care and risk counseling for intravenous drug users in the city. |

|

| |

| Day at the Market | A monthly event sponsored by the Department of Environmental Health Sciences at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health. The event occurs at the Northeast Market, a venue that was established in 1885 and is composed of more than 35 vendors. Along with our Center staff and faculty, students disseminated health education materials to community members and encouraged patrons of the market to participate in health screenings being offered by Johns Hopkins faculty and staff. |

Abbreviations: CVD = cardiovascular disease.

Shadowing/Mentoring

Each student has three clinical shadowing experiences during the internship. At the Johns Hopkins Diabetes Center, the students shadow a clinician during a schedule of diabetes outpatient appointments. Students then spend a day with a dietician who counsels high risk diabetic patients. A third experience allows students to follow a preventive cardiologist during his patient appointments.

Each student is assigned a mentor, either a center faculty member or post-doctoral trainee. These mentors facilitate the students’ engagement on one of the center’s three research projects.

Interns attend two panel presentations by a group of graduate students from the Schools of Medicine, Public Health, and Nursing, providing younger trainees with an opportunity to explore various health disciplines and career paths with individuals not far removed from their own undergraduate experience. During these sessions, graduate students discuss their decisions to enter their particular field and answer questions.

Didactic sessions

The students participate in a minimum of six faculty-led didactic sessions that focus on different aspects of CVD health and health care disparities research. Among the topics of these sessions are An Overview of Health Disparities; Ethnic Disparities: Control of Glycemia, Blood Pressure, and LDL Cholesterol Among US Adults with Type 2 Diabetes; and Health Disparities and Chronic Disease Self-management.

Final project

At the end of the internship, the students give a formal presentation on a topic related to CVD health disparities. During the first year, the Center’s studies were in the development phases; therefore, the students chose broad topics centering upon CVD disparities in Baltimore. Now presentations are based on the research questions students addressed during their internship. Health professions students are required to develop a poster presentation based on the research that they conduct during their internship with the center.

Metrics to Evaluate Program Outcomes

We evaluate trainees on their competency in cultural and social preparedness to conduct health disparities research and in health disparities-specific research skills based on surveys completed by the trainees and their mentors. Trainees complete the surveys at baseline and at the end of their training, and we will continue to administer surveys annually for five years after completion of training to assess the durability of knowledge provided by our curriculum. We also collect process measures, including trainees’ evaluation of the usefulness of curriculum components and mentorship quality, as these are important determinants of knowledge and skill acquisition. Finally, we examine objective outcomes to assess research productivity in the field of CVD health disparities annually during training and will continue to do so for 10 years after training. These metrics include the number of peer-reviewed publications and their impact, number of presentations at scientific meetings, number and types of grants received, number of awards received, and academic advancement. Table 3 summarizes the metrics used and frequency of their assessment.

Table 3. Summary of Metrics to Evaluate Program Outcomes, Johns Hopkins Center to Eliminate Cardiovascular Health Disparities.

| 1 Metric domain | Description | Frequency | Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural and social preparedness to conduct research |

Trainee self-report and mentor report of trainee’s preparedness to conduct research with the following populations: cultures different from their own; racial or ethnic minorities, individuals with religious beliefs at odds with Western Medicine, distrust of the U.S. health system, persons with low socioeconomic status, and with limited health literacy |

At baseline and annually during training and for 5 years after completing program |

Survey |

|

| |||

| Health disparities research skills |

Trainee self-report and mentor report of trainee’s skills in:

|

Annually for 5 years |

Survey |

|

| |||

| Process measures | Trainee self-report of: |

||

|

One time at the completion of fellowship |

Survey |

|

|

At the conclusion of each session |

Survey | |

|

| |||

| Number of trans- disciplinary peer- reviewed publications and author impact |

Number of articles discovered by PubMed Search and the H-index, which quantifies the actual scientific productivity and the apparent impact of the scientist |

Annually for 10 years |

PubMed search Web of Science Cited Reference Search |

|

| |||

| Number of oral and poster presentations at scientific meetings |

Number of presentation on health disparities related topics given at scientific meetings |

Annually for 10 years |

Survey; CV review |

|

| |||

| Number and type of grants received |

Peer-reviewed funding to conduct research from NIH, other federal agencies, private foundations or philanthropy; institutional funding |

Annually for 10 years |

Survey, CV, search of NIH Reporter database |

|

| |||

| Number of awards received for disparities work |

Awards for research, teaching, and/or community engagement |

Annually for 10 years |

Survey, CV |

|

| |||

| Academic advancement | Matriculation into graduate or professional school, completion of Master’s or PhD; attainment of post-doctoral fellowship; faculty position or other research position; for faculty, academic promotion |

Annually for 10 years |

Survey, web search |

Abbreviations: CV = curriculum vita; NIH = National Institutes of Health.

Preliminary Program Outcomes

Table 4 summarizes the characteristics of all trainees who have participated in our program since its inception in 2010. In addition to the 26 fellows and students who receive or have received funding from the center grant, in 2014 we also have 13 trainees who did not receive fellowship funds, but participate in our programs and conduct mentored research within the center’s three projects, as described above. The majority of trainees have been women and they come from diverse race/ethnic backgrounds (Table 4).

Table 4. Characteristics of 39 Trainees, Johns Hopkins Center to Eliminate Cardiovascular Health Disparities, 2010-2013.

| Characteristic of trainees | Measure |

|---|---|

| Female gender, no. (%) | 35 (90) |

| Hispanic ethnicity, no. (%) | 2 (5) |

| Race, no. (%) | 17 (43) |

| African American | 6(15) |

| Asian American | 16 (42) |

| White | |

| Level of trainee, no. (%) | |

| Undergraduate | 8 (20.5) |

| Post-baccalaureate | 2(5) |

| Medical student | 4(10) |

| Pre-doctoral | 6(15) |

| Post-doctoral | 11(2) |

| Faculty | 8 (20.5) |

| Supported by center funds, no. (%) | |

| Yes | 26 (67) |

| No | 13 (33) |

| Disparities-related publications, no. | |

| Total | 32 |

| Pre-doctoral | 7 |

| Post-doctoral | 14 |

| Faculty | 11 |

|

Disparities-related presentations at national and international

meetings, no. |

|

| Total | 19 |

| Pre-doctoral | 5 |

| Post-doctoral | 6 |

| Faculty | 8 |

| Junior faculty who obtained additional grant funding, no. | |

| Total | 5 |

| NIH (Mentored Patient-Oriented Research Career Development | 1 |

| Award (K23,K08) | |

| Foundation grant | 2 |

| Institutional grant | 3 |

|

Academic advancement (current positions of trainees completing

programs), no. |

|

| Undergraduate students applying to graduate or professional schoola | 3 |

| Undergraduate students accepted into graduate or professional schoola |

2 |

| Post-baccalaureate students accepted into graduate or professional school |

1 |

| Pre-doctoral students who completed PhD degrees and were accepted into post- doctoral program or obtained faculty positionb |

2 |

| Post-doctoral fellows who obtained faculty positionsc | 1 |

| Junior faculty who were promoted from assistant to associate professor |

1 |

Abbreviations: CVD = cardiovascular disease; NIH = National Institutes of Health.

Several students were still completing their undergraduate degree programs as of 2014.

One pre-doctoral student was still completing the training program as of 2014.

Three post-doctoral fellows have completed the training program but were still completing their overall 3-year post-doctoral fellowships as of 2014.

Outcomes of CVD Disparities Fellowship Program (pre-doctoral students, post-doctoral fellows, faculty)

The first two pre-doctoral fellows earned their PhD degrees in 2012—one in Health Policy and Management and one in Nursing. Two former fellows have become tenure track assistant professors—one at Johns Hopkins University and one at a another university. One faculty fellow was recently promoted to associate professor. Her manuscript, “Impact of Physician BMI on Obesity Care and Beliefs,” was selected as paper of the year by The Obesity Society.10 During their time at the center, faculty fellows have received a total of 5 NIH, foundation, and institutional grant awards. As a group, CVD disparities fellows at all levels have published 38 disparities-related papers as of spring 2014 and given 24 disparities-related presentations at national and international meetings (Table 4).

CVD Disparities Summer Internship Program (undergraduate and health professions students)

To date, 8 undergraduates, 1 post-baccalaureate, and 2 medical students representing seven universities have participated in the summer undergraduate internship. Five undergraduate students are applying to or have been accepted into medical or graduate school.

Conclusions and Future Directions

We have developed a trans-disciplinary CVD health disparities training curriculum tailored to multiple levels of trainees, from undergraduates to faculty, to equip them with clinical research and public health expertise in the areas of social epidemiology, health services research, health policy, CBPR, and implementation science. Our CVD Disparities Fellowship for faculty, post-doctoral fellows, and pre-doctoral students complements and extends the training they receive in their formal training programs by specifically teaching research skills needed to conduct studies in underserved and disparate populations. Although the examples used in our sessions relate to CVD, curriculum research topics are not CVD-specific and can be adapted and applied to many health disparity disease areas.

There are few health disparities research training programs that address the afore-mentioned disciplines simultaneously in an integrated manner. The program described by Cene and colleagues, like the one at Johns Hopkins University, includes community-based experiential activities and service learning as part of a health disparities curriculum; however, unlike our program, it does not focus on research skills.11 Estape and colleagues have described a multicultural, multi-institutional, and multidisciplinary course to teach translational research in health disparities to individuals enrolled in post-doctoral Masters of Science in Clinical Research Programs at 5 minority institutions.12 This Puerto Rico-based program is focused on reducing health disparities in Hispanic populations. Like our program, they provide supplementary health disparities research training to individuals already enrolled in advanced training programs. The course content they describe focuses on similar principles, including clinical research design and implementation, cultural diversity principles, and community engagement. Their publication describes the program implementation; however, the specifics of the curriculum are not provided; thus, the overlap in content between our programs is unclear. Additionally, we could not tell whether their program targets post-doctoral fellows only, or whether, like our program, it also targets pre-doctoral students and junior faculty. The National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities has offered a two-week intensive introductory course, annually for three years, aimed at providing clinical, public health, and public policy professionals, researchers, and members of community-based organizations with the knowledge and research tools needed to conduct translational and trans-disciplinary research and develop interventions to eliminate health disparities.13

Lessons learned

We have learned several important lessons. During the first year, we held a monthly “Speed Dating” CVD Disparities Journal Club. It was not well attended because fellows were already actively engaged in journal clubs within their formal parent training programs or were already participating in a general Health Disparities Journal Club at JHBSPH. We therefore discontinued this club; however, its focused format might be valuable at institutions where other well-established journal clubs do not exist. Initially, we also required all fellows to enroll in the health disparities certificate program. However, we soon realized the need to allow more flexibility, due to heterogeneity in fellows’ background and training, pre-existing obligations, and scheduling conflicts between the certificate program and other degree program requirements. Thus, we offer several options to help fellows meet our program’s research training and professional development objectives. The key to active fellow participation in the curriculum sessions was conducting a focus group with our initial group of fellows to determine the time when all fellows were available, the best session formats, and the topics of interest not addressed in their formal training programs. Based on their feedback, we continue to add relevant topics which have enriched our training program. We recognized early on that some of our trainees’ projects required expertise not initially found among the center’s faculty. Therefore, we sought additional trans-disciplinary collaborations and have learned that building trans-disciplinary mentoring teams is critical to our trainees’ acquisition of research and collaborative skills. One example of a trans-disciplinary research project, in which a senior and junior faculty member serve as comentors to a newly appointed assistant professor, is a collaboration that combines health services research methodologies with social epidemiology methods including geographic information systems and spatial analysis. This project describes the geographic clustering of patients at each clinical site participating in the center’s multi-level health care system quality improvement intervention study and examines the association of neighborhood demographics, healthy food availability, and crime with patients’ health outcomes. Finally, it has been invaluable to incorporate community engagement into our training activities. One of the CAB members and co-author on this manuscript (MM) assisted in conceptualizing the presentations by and evaluations of our undergraduate summer students. Organizations led by CAB members served as outstanding community-based field experiences for trainees and were among the most highly rated activities on the summer program’s evaluation. Thus, community engagement is as critical to successful disparities training as it is to successful disparities research.

Future directions

In the near future, we would like to expand the program’s curriculum to have a broader reach beyond Johns Hopkins University. Specifically, we would like to create a web-based version of our curriculum including learning objectives, videotaped lectures with sample handouts, and pre- and post-tests to assess changes in knowledge and attitudes. We would also like to develop a 1-2 day seminar of our Research Lessons Learned topics that would be open to researchers outside of our institution, as well as a JHSPH for-credit course focused on research issues specific to conducting CVD health disparities research in underserved populations. These additional avenues would enhance the sustainability and impact of our program on training the next generation of CVD disparities researchers both within and outside of our institution.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all of the faculty mentors and administrative and budgetary staff at Johns Hopkins and members of the Administrative and Shared Resources Cores and the Community and Provider Advisory Board of the Johns Hopkins Center to Eliminate Cardiovascular Health Disparities for their support of this program. They would also like to thank the other Johns Hopkins health disparities centers for their collaboration on the Health Disparities Consortium Seminar Series: the Center for Health Disparities Solutions, the Center to Reduce Cancer Disparities, the Center of Excellence for Cardiovascular Health in Vulnerable Populations, and the DC-Baltimore Research Center on Child Health Disparities.

Funding/Support:

This work was supported by a Program Project Grant [the Johns Hopkins Center to Eliminate Cardiovascular Health Disparities (P50 HL0105187)] and a Mid-Career Investigator Award [Patient-Oriented Research in Cardiovascular Health Disparities (K24HL083113)], from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: Reported as not applicable.

Contributor Information

Dr Sherita Hill Golden, is the Hugh P. McCormick Family Associate Professor of Medicine and Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland; and director of the training core, Johns Hopkins Center to Eliminate Cardiovascular Health Disparities.

Dr Tanjala Purnell, is a post-doctoral fellow, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and Johns Hopkins Center to Eliminate Cardiovascular Health Disparities, Baltimore, Maryland.

Ms Jennifer P. Halbert, is a program manager, Johns Hopkins Center to Eliminate Cardiovascular Health Disparities, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore Maryland.

Mr Richard Matens, is a program administrator, Johns Hopkins Center to Eliminate Cardiovascular Health Disparities, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland.

Dr Edgar R. “Pete” Miller, is professor of medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; and a faculty member of the training core, Johns Hopkins Center to Eliminate Cardiovascular Health Disparities.

Dr David M. Levine, is professor of medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland; and a faculty member, training core of the Johns Hopkins Center to Eliminate Cardiovascular Health Disparities.

Dr Tam H. Nguyen, is associate faculty member, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, Baltimore, Maryland.

Dr Kimberly A. Gudzune, is assistant professor of medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland.

Dr Deidra C. Crews, is assistant professor of medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland.

Rev. Dr Mankekolo Mahlangu-Ngcobo, is a faculty member, Morgan State University, Baltimore, Maryland; and a member of the Community-Provider Advisory Board, Johns Hopkins Center to Eliminate Cardiovascular Health Disparities.

Dr Lisa A. Cooper, is the James F. Fries Professor of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland; and director, Johns Hopkins Center to Eliminate Cardiovascular Health Disparities.

References

- 1.Wong MD, Shapiro MF, Boscardin WJ, Ettner SL. Contribution of major diseases to disparities in mortality. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1585–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fields LE, Burt VL, Cutler JA, Hughes J, Roccella EJ, Sorlie P. The burden of adult hypertension in the United States 1999 to 2000: A rising tide. Hypertension. 2004;44:398–404. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000142248.54761.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hajjar I, Kotchen TA. Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States, 1988-2000. JAMA. 2003;290:199–206. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klag MJ, Whelton PK, Randall BL, Neaton JD, Brancati FL, Stamler J. End-stage renal disease in African-American and white men. 16-year MRFIT findings. JAMA. 1997;277:1293–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gu Q, Burt VL, Paulose-Ram R, Yoon S, Gillum RF. High blood pressure and cardiovascular disease mortality risk among U.S. adults: The third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey mortality follow-up study. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18:302–9. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kung HC, Hoyert DL, Xu J, Murphy SL. Deaths: Final data for 2005. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2008;56:1–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golden SH, Brown A, Cauley JA, et al. Health disparities in endocrine disorders: Biological, clinical, and nonclinical factors--an Endocrine Society scientific statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E1579–E1639. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warnecke RB, Oh A, Breen N, et al. Approaching health disparities from a population perspective: The National Institutes of Health Centers for Population Health and Health Disparities. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1608–15. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.102525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper LA, Boulware LE, Miller ER, et al. Creating a trans-disciplinary research center to reduce cardiovascular health disparities in Baltimore, Maryland: Lessons learned. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:e26–38. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bleich SN, Bennett WL, Gudzune KA, Cooper LA. Impact of physician BMI on obesity care and beliefs. Obesity. 2012 May;20(5):999–1005. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cene CW, Peek ME, Jacobs E, Horowitz CR. Community-based teaching about health disparities: Combining education, scholarship, and community service. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(Suppl 2):S130–135. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1214-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Estape E, Laurido LE, Shaheen M. A multiinstitutional, multidisciplinary model for developing and teaching translational research in health disparities. Clin Transl Sci. 2011 Dec;4(6):434–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2011.00346.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. [accessed May 28, 2014];National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities Translation Health Disparities Course. 2013 http://www.nimhd.nih.gov/courseHD-2013revised02.html.

- 14.Carayon P, Schoofs Hundt A, Karsh BT, et al. Work system design for patient safety: The SEIPS model. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15(1 Suppl):i50–i58. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.015842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herzberg F, Mausner, Snyderman BB. The Motivation to Work. 2nd ed. John Wiley; New York: 1959. [Google Scholar]