Background: Osteopontin is a chemotactic protein for dendritic cells without a clear definition of its functional domains.

Results: A pro-chemotactic sequence, 168RSKSKKFRR176, spanning the thrombin cleavage site at Arg168 was identified. The C-terminal fragment released by thrombin cleavage assumes a new conformation.

Conclusion: Thrombin cleavage of osteopontin disrupts the pro-chemotactic sequence, RSKSKKFRR.

Significance: Thrombin cleavage of osteopontin modulates dendritic cell migration.

Keywords: Chemokine, Dendritic Cell, Migration, Osteopontin, Thrombin

Abstract

Thrombin cleavage alters the function of osteopontin (OPN) by exposing an integrin binding site and releasing a chemotactic C-terminal fragment. Here, we examined thrombin cleavage of OPN in the context of dendritic cell (DC) migration to define its functional domains. Full-length OPN (OPN-FL), thrombin-cleaved N-terminal fragment (OPN-R), thrombin- and carboxypeptidase B2-double-cleaved N-terminal fragment (OPN-L), and C-terminal fragment (OPN-CTF) did not have intrinsic chemotactic activity, but all potentiated CCL21-induced DC migration. OPN-FL possessed the highest potency, whereas OPNRAA-FL had substantially less activity, indicating the importance of RGD. We identified a conserved 168RSKSKKFRR176 sequence on OPN-FL that spans the thrombin cleavage site, and it demonstrated potent pro-chemotactic effects on CCL21-induced DC migration. OPN-FLR168A had reduced activity, and the double mutant OPNRAA-FLR168A had even lower activity, indicating that these functional domains accounted for most of the pro-chemotactic activity of OPN-FL. OPN-CTF also possessed substantial pro-chemotactic activity, which was fully expressed upon thrombin cleavage and its release from the intact protein, because OPN-CTF was substantially more active than OPNRAA-FLR168A containing the OPN-CTF sequence within the intact protein. OPN-R and OPN-L possessed similar potency, indicating that the newly exposed C-terminal SVVYGLR sequence in OPN-R was not involved in the pro-chemotactic effect. OPN-FL and OPN-CTF did not directly bind to the CD44 standard form or CD44v6. In conclusion, thrombin cleavage of OPN disrupts a pro-chemotactic sequence in intact OPN, and its loss of pro-chemotactic activity is compensated by the release of OPN-CTF, which assumes a new conformation and possesses substantial activity in enhancing chemokine-induced migration of DCs.

Introduction

Osteopontin (OPN)3 is constitutively expressed as a component of bone matrix and released as a soluble, pleiotropic cytokine by various cell types. Expression of OPN in T cells, NK cells, monocytes, and macrophages only becomes prominent and pathophysiologically relevant upon cellular activation (1). This increased expression significantly modulates innate and adaptive immunity due to engagement of OPN with a number of integrin receptors expressed on leukocytes. In addition to promoting leukocyte cell survival (2), differentiation (3), and mobilization (4), a prominent role of OPN in immunity is to regulate leukocyte adhesion, migration, and trafficking (1). OPN-deficient mice are protected from angiotensin-II-accelerated atherosclerosis and aneurysm formation, due to decreased vascular macrophage infiltration and inflammatory activities in the absence of OPN (5).

OPN is also expressed in dendritic cells (DCs), the professional antigen-presenting cells. However, in contrast to other immune cells, OPN expression is strongly up-regulated early during DC differentiation from bone marrow precursors, and its secretion is markedly decreased when DCs become terminally differentiated and activated (6). Increased OPN expression in DCs is found in experimental autoimmune encephalitis and in patients with multiple sclerosis (7). OPN-deficient mice have impaired migration of DCs to lymph nodes, leading to attenuated delayed cutaneous contact hypersensitivity (3).

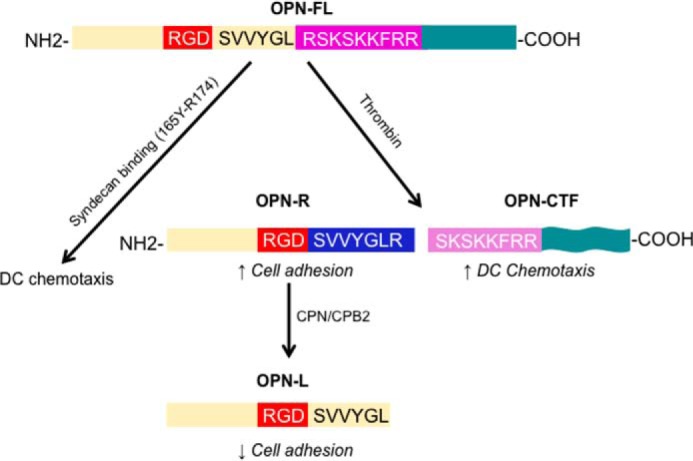

Structure-function studies had previously shown that human full-length OPN contains at least three functional cellular binding domains that are responsible for cell adhesion, spreading, and migration. A highly conserved 158GRGDS162 motif binds to RGD-recognizing integrins, including αvβ1, αvβ3, αvβ5, α5β1, and α8β1, and confers cell adhesion, spreading, haptotaxis, and cellular signaling. Adjacent to this RGD domain is a thrombin cleavage site at Arg168↓Ser169. Thrombin cleavage of full-length OPN (OPN-FL) leads to OPN-Arg (OPN-R), with a newly exposed C-terminal sequence, 162SVVYGLR168, that binds to α4β1 and α9β1 integrins, allowing RGD-independent cell adhesion (8–10) and a survival advantage to cells (11). Carboxypeptidase N (CPN) or B2 (CPB2) can remove Arg168 from OPN-R, converting it to OPN-Leu (OPN-L), inactivating the binding site for integrin α9β1 (12). In addition to these two binding sites, a putative CD44 binding domain is located within the last 18 amino acids at the highly conserved C terminus (13). Another highly conserved sequence that spans the thrombin cleavage site, 165YGLRSKSKKFRR174, binds to the heparan sulfate on syndecan-4, protecting OPN-FL from cleavage by thrombin (14).

Both thrombin generation and OPN expression are enhanced during inflammation. Thrombin cleavage alters OPN function, allowing better accessibility to RGD by integrin α5β3 (15) and to SVVYGLR by α9β1 and α4β1 integrins (10). However, the integrity of OPN appears to be necessary for certain functions of OPN. Phosphorylation of OPN at the C-terminal region inhibits RGD-mediated cell adhesion to OPN-FL (16), and antibody blocking of C-terminal Lys298–Asn314 also inhibits OPN-FL binding to integrin-expressing cells (17). Furthermore, following thrombin cleavage, the OPN C-terminal fragment (OPN-CTF), Ser169–Asn314, is chemotactic for macrophages (18, 19). Similarly, a 5-kDa fragment (Leu167–Asp210) released by matrix metalloprotease (MMP)-9 cleavage, which overlaps the N-terminal sequence of OPN-CTF, induces migration of hepatocellular carcinoma cells (20). Although the OPN C-terminal half sequence is well conserved between species, the biochemical properties, pathophysiological role, and fate of OPN-CTF after thrombin cleavage have not been fully defined.

Upon antigen uptake and activation, DCs migrate to lymph nodes, a process primarily driven by engagement of chemokines CCL19 and CCL21 with their common receptor CCR7 (21). Because both DCs (6, 22) and T cells (23) are sources of OPN that may play a role in DC migration, in this study, we investigated the impact of thrombin cleavage of OPN on DC migration to identify the functional domains of OPN. We identified a new pro-chemotactic domain in OPN-FL spanning its thrombin cleavage site. Thrombin cleavage disrupts its integrity, leading to a significant reduction in its pro-chemotactic function, but this is compensated by the released OPN-CTF that may assume a new conformation and possesses substantial pro-chemotactic activity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Synthetic peptides were synthesized and purified by Elim Biopharmaceuticals (Hayward, CA), and their sequences are listed in Table 1. The following murine monoclonal IgG antibodies directed against human integrins and various cell surface antigens were from BioLegend (San Diego, CA): 9F/10 (α4, CD49d), NKI-M9 (αV, CD51), TS2/16 (β1, CD29), Y9A2 (α9β1), AST-3T (β5), 23C6 (αVβ3), IM7 (pan-CD44), L243 (HLR-DR), HI149 (CD1a), G043H7 (CCR7), and 3.9 (CD11c). Antibody clone 515 (anti-pan-CD44) was from BD Biosciences. Antibody clone 2F10 (anti-CD44v6) was from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). OPN-CTF-specific monoclonal antibody clone MAB197P was from Maine Biotechnology Services (Portland, ME) Human CD44-Fc fusion protein was purchased from R&D Systems. Rat CD44v6 ectodomain protein with a His6 tag fused at its C terminus was provided by Dr. V. Orian-Rousseau (Institute of Toxicology and Genetics, Karlsruhe, Germany) (24).

TABLE 1.

Sequences of synthetic peptides

| Peptides | Sequences |

|---|---|

| P0 | 162SVVYGLRSKSKKFRR176 |

| P0R168A | 162SVVYGLASKSKKFRR176 |

| P0K170A | 162SVVYGLRSASKKFRR176 |

| P0K172A/K173A | 162SVVYGLRSKSAAFRR176 |

| P0reversed | 176RRFKKSKSRLGYVVS162 |

| PR168-T185 | 168RSKSKKFRRPDIQYPDAT185 |

| PS169-T185 | 169SKSKKFRRPDIQYPDAT185 |

| PS169-T185-scrambled | AKDSRPIRPDKFSYQKT |

| P1 | 169SKSKKFRRPDIQYPDATDEDITSHM193 |

| P2 | 189ITSHMESEELNGAYKAIPVAQDLNA213 |

| P3 | 209QDLNAPSDWDSRGKDSYETSQLDDQ233 |

| P4 | 229QLDDQSAETHSHKQSRLYKRKANDE253 |

| P5 | 249KANDESNEHSDVIDSQELSKVSREF273 |

| P6 | 269VSREFHSHEFHSHEDMLVVDPKSKE293 |

| P7 | 289PKSKEEDKHLKFRISHELDSASSEVN314 |

Mice

OPN−/− mice on a C57BL/6J background were obtained from Jackson Laboratories and bred at the Stanford University School of Medicine Veterinary Service Center. Wild type C57BL/6J mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Sacramento, CA). All mouse experiments were performed under protocols approved by the Stanford University School of Medicine Committee of Animal Research and were in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Production of Recombinant Osteopontin

Recombinant human OPN-FL, OPN-R, and OPN-L and RGD-mutated OPN-FL, denoted as OPNRAA-FL, were generated as described previously (12). The cDNA encoding mature human OPN-FL and its RGD-mutated counterpart in which Arg168 was replaced by alanine (OPN-FLR168A and OPNRAA-FLR168A, respectively) and OPN-CTF (amino acids Ser169–Asn314) were inserted as C-terminal in-frame fusions to GST using the Escherichia coli expression vector pGEX-6P-3 (GE Healthcare). The mutated sequences were generated using site-directed mutagenesis (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara CA). The cDNA encoding OPN-CTF was inserted into E. coli expression vector pET-24D (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) with a free N terminus and with a His6 tag fused at the C terminus. The plasmids pOPN-FLR168A, pOPNRAA-FLR168A, pOPN-CTF, and pOPN-CTFHis6 were transformed into One Shot Top10 Chemically Competent E. coli (Invitrogen) for plasmid expansion, purified with a Qiagen plasmid Midi kit (Germantown, MD), and sequenced by ELIM Biopharmaceuticals to verify the mutation (Hayward, CA). The purified plasmids were then transformed into One Shot BL21(DE3) pLysS Chemically Competent E. coli (Invitrogen). The procedures for large scale production and purification of OPN-FLR168A and OPN-CTF were similar to those used previously to produce other OPN forms (12). His6-tagged OPN-CTFHis6 was purified from lysate of E. coli that overexpressed OPN-CTFHis6 using a HisTrap FF column (GE Healthcare). Lysate was loaded in 40 mm imidazole in phosphate buffer (20 mm sodium phosphate, 0.5 m NaCl, pH 7.4), and bound protein was eluted with 500 mm imidazole in phosphate buffer (20 mm sodium phosphate, 0.5 m NaCl, pH 7.4). The N-terminal sequence of the OPN-CTFHis6 was verified by Edman degradation. The schematic structure and sequences of recombinant OPN and OPN fragments used in this study are illustrated in Fig. 1A. The recombinant proteins were greater than 95% pure as judged by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Blue staining (Fig. 1B). The endotoxin levels in all protein samples were less than 2 EU/ml, as determined by the ToxinSensor Chromogenic LAL endotoxin assay kit (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic structure and purity of recombinant human osteopontins. A, schematic of recombinant mature full-length human OPN (amino acids 1–314) (OPN-FL), RGD-mutated OPN-FL (OPNRAA-FL), mature full-length human OPN mutant in which Arg168 was substituted with Ala (OPN-FLR168A), and double mutant OPNRAA-FLR168A and thrombin-cleaved OPN N-terminal fragment 1–168 (OPN-R), thrombin- and CPB2-cleaved OPN N-terminal fragment 1–167 (OPN-L), thrombin-cleaved OPN C-terminal fragment 169–314 (OPN-CTF) (all the above recombinant proteins have GST fused to their N termini), and thrombin-cleaved OPN C-terminal fragment with free N terminus and His6 tag at its C terminus (OPN-CTFHis6). B, recombinant osteopontin proteins were purified by affinity chromatography using a glutathione-Sepharose column. A total of 2 μg of purified proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained by Coomassie Brilliant Blue.

Preparation of Human and Mouse DCs

DCs were prepared from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells in buffy coats from 500 ml of whole blood obtained from the Stanford Blood Center. Briefly, 30–35 ml of the buffy coat was layered over 15 ml of Ficoll-Paque PREMIUM separating solution (GE Healthcare). Mononuclear cells were separated by gradient centrifugation at 300 × g for 30 min at room temperature. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were collected and washed with HBSS before incubation with FcR-blocking reagent (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) and anti-CD14-conjugated magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec). The CD14+ cells were selected using an LS column on a MidiMACS separator. The CD14+ cell fraction was cultured in 6-well or T-75 tissue culture-treated culture plates for 6 days at a density of 106/ml in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 ng/ml recombinant human GM-CSF (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ), and 100 ng/ml recombinant human IL-4 (PeproTech) to obtain immature DCs. Immature DCs were matured by adding 100 ng/ml LPS from E. coli 0128:B12 (Sigma-Aldrich) to the cell culture on day 7, and mature DCs were harvested 18 h later. Mouse bone marrow cells from 10–12-week-old C57BL/6 or OPN−/− male mice were grown in RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS and 100 ng/ml recombinant murine GM-CSF (PeproTech) for 6 days to derive bone marrow-derived DCs as described previously (25) before maturation with 100 ng/ml LPS for 18 h.

Phenotyping of Mature Human DCs

Mature DCs were harvested, washed with HBSS, and suspended in HBSS supplemented with 2% FBS (HBSS2) at a density of 107 cells/ml. The cell suspension (100 μl) was incubated with FcR-blocking reagent (Miltenyi Biotec) and stained with fluorescent specific antibodies against CCR7, CD11c, CD1a, HLA-DR, integrin α4, αV, β1, β5, α9β1, αvβ3, CD44, or CD44v6 and corresponding isotype antibodies for 30 min at 4 °C. The cells were then washed three times with HBSS2 to remove unbound antibodies and resuspended in HBSS2 before analysis by flow cytometry using a BD LSRII Fortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). The data were analyzed using Flowjo software (Treestar, Ashland, OR).

DC Migration Assay

Mature or immature DCs were harvested, washed three times with HBSS, and resuspended at 2 × 106/ml in RPMI 1640 medium with no phenol red, and 2 × 105 cells in 100 μl of RPMI 1640 were added to the upper chamber of a Transwell plate (Corning, Inc.; 6.5-mm diameter, 5.0-μm pore size). The chemoattractant being tested was added to the lower chamber in 600 μl of RPMI 1640. The cells were incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 4 h. The cells that migrated to the lower chamber of the Transwell chamber were determined using a cell counting kit (Dojindo, Japan), and absorbance was read at 450 nm. The signals from medium alone were averaged and subtracted as background. The chemotactic index, a normalized measure of the chemotaxis, was calculated as (number of migrated cells)/(number of cells that migrated to CCL21 or CCL19).

Surface Plasmon Resonance

Binding of MAB197P, CD44-Fc, and CD44v6 with OPN was measured using the Bio-Rad ProteOn XPR36 system (Bio-Rad) and GLM chips. The chip was activated with 40 mm 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethyl aminopropyl) carbodiimide and 10 mm N-hydroxysuccinimide injected at a flow rate of 30 μl/min for 120 s immediately after mixing. The antibody MAB197P, CD44-Fc, or CD44v6 protein molecules were immobilized onto a GLM chip through amine coupling to the carboxyl groups on the chip. Briefly, 10–25 μg/ml MAB197P and 10 μg/ml CD44-Fc and CD44v6 in 10 mm acetate (pH 4.0) were injected onto the chip surface at a flow rate of 30 μl/min for 60 s. The chip surface was then deactivated with 1 m ethanolamine HCl. OPN-FL, OPN-CTF, OPNRAA-FLR168A, or OPN-CTFHis6 in PBS containing 0.005% Tween 20 (pH 7.4) or buffer containing 2 mm Ca2+, 2 mm Mg2+, 50 mm Tris, and 100 mm NaCl (pH 7.4) at concentrations from 10 to 1000 nm was passed over the chip surface at a rate of 50 μl/min for 180 s. The antibody IM7 (pan-CD44) at concentrations from 0.62 to 50 nm was injected to measure its binding to immobilized CD44-Fc or CD44v6 as a positive control. All data were corrected for both an interspot reference where samples were passed over a chip surface without any immobilized protein and a row reference where PBS-Tween buffer was passed over a chip surface with immobilized MAB197P, CD44-Fc, or CD44v6. Binding data were analyzed using ProteOn Manager software.

Measurement of Calcium Transients

DCs were incubated in HBSS (Ca2+, Mg2+) with 5 μg/ml Fluo-8/AM (AAT Bioquest, Sunnyvale, CA), 2.5 mm probenecid (AAT Bioquest), 0.04% pluronic F127 (AAT Bioquest) at 37 °C for 30 min to load the calcium indicator, Fluo-8. Washed cells were then suspended in HBSS (Ca2+, Mg2+), and 100 μl was plated in Nunclon 96-well microwell plates (Thermo Scientific) at a density of 1.25 × 105/well. Baseline green fluorescence (excitation, 485 nm; emission, 538) was recorded, followed by the addition of CCL21 or premixed CCL21-OPN. The green fluorescence was recorded over 3 min immediately to monitor the calcium transient. The amplitude of calcium transient, denoted as ΔE538 nm, was calculated by subtracting the baseline fluorescence from the maximum values of the green fluorescence.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed with Prism version 6.02 for Windows. Student's t test was used to compare two groups, and analysis of variance with post hoc Dunnet multiple comparison was used for comparison of three or more groups. Error bars show 95% confidence interval (CI). p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The sigmoidal dose response model in Prism version 6.02 was used for curve fitting in experiments to determine dose dependence. EC50 values are presented as mean with CI in parenthesis.

RESULTS

Expression of OPN Receptors on Human Monocyte-derived DCs

Differentiation and maturation of human DCs from peripheral blood mononuclear cells generated cells that displayed a phenotype similar to that of conventional myeloid DCs (26), including the presence of the surface markers CD11c, HLA-DR, CD1a, and CCR7 (Fig. 2). These DCs expressed CD44, CD44v6, αv, αvβ3, αvβ5, β1, α4β1, and α9β1 integrins, all of which have been reported to be OPN receptors.

FIGURE 2.

Cell surface phenotype of human monocyte-derived DCs. Flow cytometry analysis of DC surface expression of CD44, CD44v6, αv, αvβ3, αvβ5, β1, α4β1, and α9β1 integrins, CD11c, HLA-DR, CD1a, and CCR7 on LPS-stimulated mature human monocyte-derived DCs. Gray-filled histograms, isotype controls; black empty histograms, target antigens.

Neither OPN nor Its Fragments Induce Migration of Mature DCs

Because OPN had previously been shown to induce mouse DC (3) and macrophage (19) chemotaxis, we first tested the potency of OPN in inducing human DC migration in comparison with the lymphatic chemokine CCL21 in a transmigration assay. To our surprise, mature DCs did not migrate toward OPN-FL, OPNRAA-FL, OPN-R, and OPN-L (Fig. 3A). To exclude the possibility that OPN caused DCs to adhere to the polycarbonate membrane and not transmigrate into the lower wells, we used 0.025% trypsin EDTA to detach any DCs from the lower surface of the insert membrane but did not observe any cells that became detached. In contrast, DCs readily migrated to the lower chamber when it contained CCL21 (4.2 nm), with ∼10% of the input cells in the lower chamber at 4 h.

FIGURE 3.

OPN-FL and thrombin-cleaved N-terminal fragments enhance DC migration toward lymphatic chemokines CCL21 and CCL19. DCs were added to the upper chamber of a Transwell plate. CCL21 (50 ng/ml or 4.2 nm) and/or OPN (100 nm) was added into serum-free culture medium in the lower chamber to create a concentration gradient. A, DC migration to OPN or thrombin-cleaved OPN fragments was compared with migration of DCs to CCL21 (n = 9–24; data pooled from seven independent experiments; *, p < 0.0001, CCL21 versus each OPN). B, DC migration to CCL21 in the presence of various concentrations of OPN-FL (n = 3–6). The level of migration observed in CCL21 alone was subtracted for curve fitting. C, DC migration to 50 ng/ml CCL21 in the presence of 100 nm OPN was compared with migration to CCL21 alone (n = 6–20; data pooled from six independent experiments). D, DC migration to 25 ng/ml CCL19 in the presence of 100 nm OPN was compared with migration to CCL19 alone (n = 6; data are representative of three independent experiments). In all experiments, the value from medium alone was subtracted as background. Migrated cells in the lower chamber of the Transwell were normalized relative to cells migrating to CCL21 or CCL19. Data are shown as mean with CI (error bars).

Enhancement of CCL21-induced DC Migration Involves the RGD Domain

Although OPN and its fragments by themselves are not chemotactic for DCs, OPN-FL could augment the effect of CCL21 on DC migration, with an EC50 of 358 nm (CI, 248–518 nm) (Fig. 3B). Based on that EC50, OPN fragments were tested at 100 nm for their effects on CCL21-induced DC migration. Compared with OPN-FL, OPNRAA-FL had a significantly reduced potentiation effect (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3C), indicating the importance of the RGD domain. Similarly, OPN-R and OPN-L also augmented CCL21-induced DC migration (Fig. 3C), but the extent of augmentation was substantially less than that of OPN-FL. There was no significant difference between OPN-R and OPN-L, suggesting that the newly exposed C-terminal SVVYGLR binding site in OPN-R does not play a role in this potentiation of chemotaxis. The reduction in the potency of OPN-R versus OPN-FL suggests that in OPN-FL, the augmentation might also be mediated via the C-terminal fragment. To demonstrate that the potentiating effect was not CCL21-specific, we tested CCL19, another lymphatic chemokine that binds to CCR7, and found that CCL19-induced DC migration was also augmented by OPN and its fragments in a pattern similar to that observed with CCL21 (Fig. 3D).

OPN-CTF Enhances CCL21-induced DC Migration

To investigate the role of OPN-CTF in CCL21-induced DC migration, recombinant OPN-CTF (Ser169–Asn314) was expressed and purified (Fig. 1B). Similar to OPN-FL, OPN-CTF by itself did not induce DC migration but potentiated the CCL21-induced chemotaxis with an EC50 of 326 nm (CI, 139–778 nm) (Fig. 4, A and B). The potency is in the same range as that of OPN-FL. In the presence of 100 nm OPN-CTF, the CCL21 dose-response curve was shifted to the left without increasing the maximum effect of CCL21 (Fig. 4C), suggesting that OPN-CTF increased the potency of CCL21 but not its efficacy. Interestingly, when both OPN-CTF and OPN-R were added at the same molar concentration to the lower wells, no additive effect was observed (Fig. 4A). These data strongly suggested that the integrity of OPN-FL is necessary for its maximum effect. In order to identify the functional domain(s) on OPN-CTF that is responsible for its potentiating effect, we synthesized eight overlapping peptides based on the OPN-CTF sequence that are least 25 amino acids long and have at least a 5-amino acid overlap with the next peptide (Table 1). These were tested for their ability to antagonize DC migration in the presence of OPN-CTF and CCL21 as well as to promote DC migration to CCL21. In the antagonism experiment, none of the eight peptides inhibited the potentiating effect of OPN-CTF on CCL21-induced DC migration (data not shown). Next we tested whether any of the peptides could augment CCL21-induced migration of DCs. Peptide P0 (Ser162–Arg176), which overlapped the thrombin cleavage site and contained SVVYGLR and the first 8 N-terminal amino acids of the OPN-CTF, markedly enhanced CCL21-induced cell migration. P1 (Ser169–Met193) and P7 (Pro289–Asn314), located at the N and C termini of OPN-CTF, respectively, also augmented CCL21-induced migration of DCs, although they were much less potent than P0 (Fig. 4D).

FIGURE 4.

DC migration toward CCL21 in the presence of thrombin-cleaved OPN C-terminal fragment and its overlapping peptides. A, DC migration to CCL21 (50 ng/ml or 4.2 nm) in the presence of 100 nm OPN-CTF, OPN-FL, OPN-R, or a combination of 100 nm OPN-CTF + 100 nm OPN-R (n = 6–25; data pooled from three independent experiments). B, DC migration to CCL21 (50 ng/ml or 4.2 nm) in the presence of various concentrations of OPN-CTF (n = 3–4). The level of migration observed in CCL21 alone was subtracted. C, DC migrations to various concentrations (0.3–200 nm) of CCL21 in the presence of 100 nm OPN-CTF (n = 4). D, DC migration to CCL21 in the presence of 2 μm overlapping peptides P0–P7 derived from OPN-CTF. (See Table 1 for peptide sequences; n = 6–17; data pooled from three independent experiments). Data are shown as mean with CI (error bars). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ****, p < 0.0001.

SVVYGLRKSKKFRR Is a Pro-chemotactic Sequence within OPN-FL

Because of the markedly higher potency of P0 (Ser162–Arg176) than P1 (Ser169–Met193), we hypothesized that the sequence spanning the thrombin cleavage site, 162SVVYGLRSKSKKFRR176, is key for the augmentation by OPN-FL of CCL21-induced migration of DCs. To test this hypothesis, we produced a mutant protein, OPN-FLR168A, in which Arg168 was replaced by alanine. This protein was significantly less active than the wild type OPN-FL (p < 0.0001; Fig. 5A). Similarly peptide P0 is significantly more active than the mutant peptide P0R168A containing the same substitution of Ala for Arg168 (Fig. 5B). These data confirmed that Arg168 is a key residue for the augmentation of CCL21-induced DC migration by OPN-FL. We further examined other basic amino acids present in the peptide P0 by testing two more peptides, P0K170A and P0K172A/K173A, in which basic amino acids Lys170, Lys172, and Lys173 were replaced by alanine. Both mutants demonstrated significantly less potency than P0, as shown in a dose-dependent study of DC migration in response to CCL21 (Fig. 5B). Additionally, P0reverse, which had the sequence of P0 reversed but possesses the same charge, was significantly less potent than P0, indicating that the effect of P0 was sequence-specific and was not just due to its high pI. None of the synthetic peptides induced DC migration by themselves (data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that R168A plays a key role in the potentiating effect of OPN-FL and P0.

FIGURE 5.

Sequence spanning thrombin cleavage site is pro-chemotactic. A, DC migration to CCL21 (50 ng/ml or 4.2 nm) in the presence of 100 nm OPN-FL, OPNRAA-FL, OPN-FLR168A, and OPNRAA-FLR168A (n = 4–20; data pooled from four independent experiments). B, DC migration to 50 ng/ml CCL21 was measured in the presence of various concentrations of P0, P0R168A, P0K170A, P0K172A/K173A, and P0reversed (see Table 1 for peptide sequences; n = 10; data are representative of three independent experiments). C, DC migration to 50 ng/ml CCL21 was measured in the presence of various concentrations of P0, PR168-T185, PS169-T185, and PS168-T185-scrambled (see Table 1 for peptide sequences; n = 9–10; data are representative of two independent experiments). Data are shown as mean with CI (error bars).

Thrombin Cleavage Reduces the Pro-chemotactic Activity of OPN-FL by Disrupting the Sequence RSKSKKFRR

Because thrombin cleavage of OPN disrupted the sequence of P0, 152SVVYGLRSKSKKFRR176, we designed additional peptides to study the consequence of thrombin cleavage. Peptide PS169-T185, corresponding to the first 17 N-terminal amino acids in thrombin-cleaved OPN-CTF, had a modest potentiating effect on CCL21-induced DC migration compared with its scrambled sequence, whereas PR168-T185 demonstrated the same potency as P0, as shown in a dose-dependent study (Fig. 5C). These data confirmed the key role of Arg168 in this pro-chemotactic sequence and excluded the involvement of SVVYGLR.

OPN-CTF Manifests Its Full Pro-chemotactic Activity upon Thrombin Cleavage and Release from OPN-FL

To assess the relative role of RGD, Arg168, and the C-terminal fragment (Ser169–Asn314), we produced a double mutant protein, OPNRAA-FLR168A. The double mutant OPN had markedly reduced pro-chemotactic activity, and strikingly, on an equimolar basis, it was much less active than OPN-CTF (Fig. 6A), suggesting that the full pro-chemotactic activity of the C-terminal fragment may be expressed only upon thrombin cleavage and its release from the intact protein, resulting in an alteration of its conformation. That the pro-chemotactic activity of OPN-CTF is conformation-dependent is also suggested by the finding that the addition of a His6 tag to the C terminus of OPN-CTF markedly reduced its activity (Fig. 6B). To further demonstrate this, we measured the binding of an OPN-CTF-specific monoclonal antibody, MAB197P, to OPN-FL, OPN-CTF, OPNRAA-FLR168A, and OPN-CTFHis6, which all contain the OPN-CTF sequence but differ in their C- or N-terminal modifications. The association rate constants (Ka) for MAB197P binding to all four recombinant OPN proteins were similar (Fig. 6C and Table 2). However, the disassociation rate constants (Kd) and equilibrium state constants (KD) of MAP197P binding to OPN-CTF were about 6 times lower than its binding to OPN-FL and OPN-CTFHis6. Interestingly, binding of MAB197P to OPNRAA-FLR168A was essentially irreversible because there was a >10-order of magnitude decrease in Kd and KD when compared with its binding to the other forms of OPN. The difference in binding kinetics of MAB197P to these different OPN proteins revealed that OPN-CTF exists in different conformations, depending on its adjacent N- or C-terminal sequences.

FIGURE 6.

Thrombin cleavage and C-terminal modification altered pro-chemotactic activity of OPN-CTF. A, DC migrated to CCL21 (50 ng/ml or 4.2 nm) in the presence of various concentrations of OPN-CTF and OPNRAA-FLR168A (n = 4–8; data pooled from two independent experiments); B, DC migration to CCL21 (50 ng/ml or 4.2 nm) in the presence of various concentrations of OPN-CTF and OPN-CTFHis6 (n = 8; data pooled from two independent experiments). Data are shown as mean with CI (error bars). C, representative surface plasmon resonance sensorgrams of OPN-FL, OPN-CTF, OPNRAA-FLR168A, and OPN-CTFHis6 binding to immobilized MAB197P. Langmuir fits to the kinetic data are shown in Table 2. Response (resonance units (RU)) is plotted against time. Injected OPN concentrations (from top to bottom traces) are 1000, 300, 100, 30, and 10 nm.

TABLE 2.

Kinetics of MAB197P binding to recombinant OPN

Data are shown as mean ± S.D.

| Ka | Kd | KD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GST-OPN-FL | 2.34 ± 0.50 × 104 | 3.71 ± 0.28 × 10−4 | 2.53 ± 0.41 × 10−8 |

| GST-OPN-CTF | 1.82 ± 0.32 × 104 | 5.80 ± 1.69 × 10−5 | 4.93 ± 2.19 × 10−9 |

| GST-OPNRAA-FLR168A | 1.73 ± 0.40 × 104 | 4.93 ± 1.93 × 10−18 | 6.59 ± 4.30 × 10−22 |

| OPN-CTFHis6 | 2.35 ± 0.76 × 104 | 3.63 ± 0.33 × 10−4 | 2.44 ± 0.56 × 10−8 |

OPN-FL and OPN-CTF Exert Maximum Effect When Present in Physical Proximity to CCL21

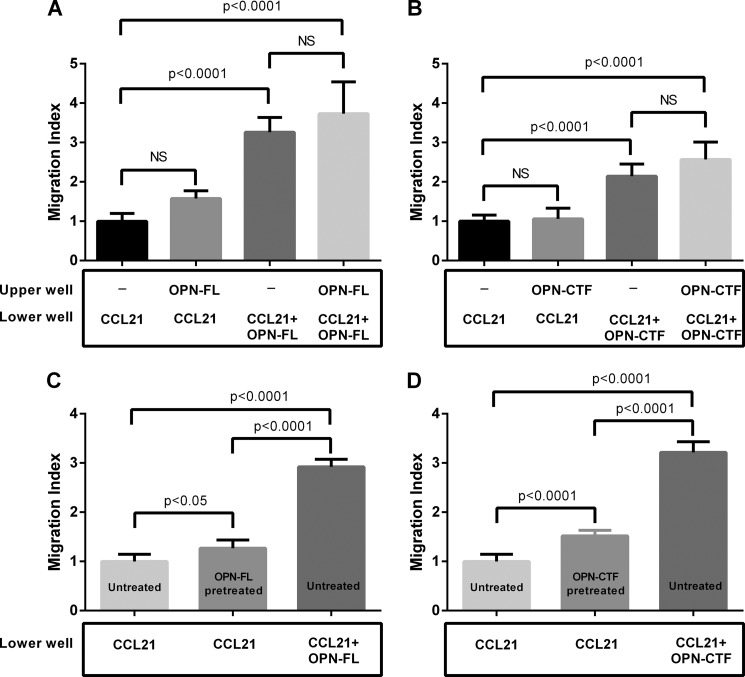

To test whether the effect of OPN-FL and OPN-CTF requires a concentration gradient, similar to CC chemokines, we assessed CCL21-induced DC migration when OPN was present in the upper well, lower well, or both in the cell migration assay. When OPN-FL or OPN-CTF was present in the upper well, no enhancement of CCL21-induced migration was observed relative to CCL21 alone in the lower well (Fig. 7, A and B). When OPN-FL or OPN-CTF was present both in upper and lower wells, the enhancement was similar to that of CCL21 plus OPN-FL or OPN-CTF in the lower well alone (Fig. 7, A and B). These data suggest that a concentration gradient is not required, and both OPN-FL and OPN-CTF need to be present in physical proximity to CCL21 to enhance chemotaxis. We then assessed the kinetics of OPN-FL and OPN-CTF on CCL21-induced DC migration. Although pretreatment with OPN-FL or OPN-CTF slightly enhanced CCL21-induced DC migration, the degree of enhancement was markedly less than that observed if OPN was constantly present in the lower wells during the experiment (Fig. 7, C and D).

FIGURE 7.

Maximum effect of OPN-FL and OPN-CTF requires temporal and physical co-existence of OPN and CCL21. DC migration to CCL21 (50 ng/ml or 4.2 nm) in the presence of 100 nm OPN-FL (A) or 100 nm OPN-CTF (B) in the upper well, lower well, or both upper and lower wells (n = 16; data pooled from two independent experiments). DCs were treated with 100 nm OPN-FL (C) or 100 nm OPN-CTF (D) for 1 h, followed by washing with PBS to remove residual OPN-FL or OPN-CTF. OPN-pretreated and untreated DCs were loaded onto upper wells of Transwell plates, in which the lower wells contained CCL21 (50 ng/ml) or CCL21 (50 ng/ml) and 100 nm OPN-FL/OPN-CTF (n = 8–22; data pooled from three independent experiments). Error bars, CI.

OPN-FL and OPN-CTF Do Not Alter the Amplitude of CCL21-induced Calcium Transients in DCs

Activation of CCR7, a Gi-coupled G protein-coupled receptor, induces an intracellular calcium transient, whose amplitude is associated with the concentration of the ligand. Therefore, we assessed whether OPN-FL or OPN-CTF alters the amplitude of the CCL21-induced calcium transient in DCs. CCL21 induced intracellular calcium transients in a dose-dependent fashion with an EC50 of 3.56 nm (CI, 2.35–5.40 nm) (Fig. 8A). We then measured the calcium transients generated when CCL21 was added to a DC suspension in which OPN-FL or OPN-CTF was present. Under these conditions, the presence of OPN-FL or OPN-CTF did not change the amplitude of the CCL21-induced intracellular calcium transient (Fig. 8B).

FIGURE 8.

OPN-FL or OPN-CTF does not alter the amplitude of CCL21-induced calcium transients. Mature DCs were loaded with the calcium indicator Fluo-8 and plated onto a 96-well plate. A, various concentrations (20 pm to 200 nm) of CCL21 were added to DC suspensions to demonstrate a dose-dependent response of CCL21-induced calcium transients (EC50 = 3.56 nm; n = 3–4 at each concentration). B, CCL21 (50 ng/ml or 4.1 nm) was added into DC suspension in which OPN-FL or OPN-CTF was present (n = 11). The green fluorescence (excitation, 485 nm; emission, 488 nm) was recorded before and after the addition of CCL21. ΔE488 indicates the maximum change in fluorescence upon CCL21 stimulation. Error bars, CI.

OPN-FL and OPN-CTF Do Not Bind to CD44s and CD44v6

The standard form of CD44 (CD44s) and its variant form CD44v6 have been implicated as OPN receptors in experiments in which the effects of OPN interactions with cells were inhibited by anti-CD44 antibodies (3, 18, 19, 27). We tried to block DC migration using anti-CD44 antibodies. We noticed, however, that anti-CD44s or anti-CD44v6 antibodies antagonized CCL21-induced DC migration in the absence of OPN. The anti-pan-CD44 antibody clone IM7 completely abolished DC motility because the migration observed in its presence was significantly less than that found in medium alone (Fig. 9). These results suggest that the anti-CD44 antibodies had a direct inhibitory effect on DC migration, which is not mediated via blocking of CD44 interaction with OPN.

FIGURE 9.

Anti-CD44 and CD44v6 antibodies blocked 50 ng/ml CCL21-induced migration in the absence of OPN. The cells were treated with 10 μg/ml of antibody for 15 min before adding them to the upper chamber. Antibody (10 μg/ml) was added to the lower chamber of the Transwell plate (n = 8–14; data pooled from two independent experiments). Data are shown as mean with CI (error bars). *, p < 0.05; ****, p < 0.0001.

To further investigate whether OPN or its thrombin-cleaved fragments interacted with one of the CD44 variants, we measured the binding of OPN-FL and OPN-CTF to CD44s by an ELISA binding assay in which protein binding to immobilized CD44s was measured using anti-GST. No binding was detected between CD44s and OPN either in the presence or absence of divalent cations (data not shown). Using surface plasmon resonance, we also did not detect any measurable binding of OPN-FL and OPN-CTF to immobilized CD44s-His6 or CD44v6 ectodomain in the presence or absence of divalent cations, whereas the control consisting of anti-CD44 (IM7) binding to the immobilized CD44 proteins was positive (data not shown).

OPN Augments Chemokine-induced Chemotaxis of Murine DCs

Because the thrombin cleavage site is conserved between species (11), we tested whether the augmentation of chemokine-induced DC migration also applies to other species and chemokines. To do so, we examined the effect of human OPN and its fragments on augmenting mouse bone-marrow-derived DCs (BMDCs) migrating to CCL21 and immature BMDC migration to CCL3. We observed a similar pattern of potentiating effects by OPN in BMDCs because OPN-FL and its fragments by themselves did not induce mouse DC migration. Instead, OPN-FL augmented both CCL21- and CCL3-induced DC migration with a significant reduction when OPN-R or OPN-L was tested (Fig. 10, A and B). This is consistent with the suggestion that OPN enhances all chemokine-induced DC migration. Mature mouse BMDCs from OPN-deficient mice responded to exogenous added OPN in a similar pattern (Fig. 10C), indicating that the augmentation was independent of DC production of OPN and intracellular OPN.

FIGURE 10.

Mouse bone marrow-derived DCs migrate to chemokines in the presence of OPN. A, WT mature BMDC migration toward CCL21 (100 ng/ml or 8.4 nm) supplemented with different OPN forms was compared with migration to CCL21 alone (n = 8). B, WT immature BMDC migration to CCL3 (50 ng/ml or 6.4 nm) supplemented with different OPN forms was compared with migration to CCL3 alone (n = 3). C, mature OPN−/− BMDC migration to 100 ng/ml CCL21 supplemented with different OPN forms was compared with migration to CCL21 alone (n = 3). Data are shown as mean with CI (error bars). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated the role of OPN as an enhancer of CC-chemokine-induced DC migration while not being a chemoattractant by itself. When DCs are activated, a rapid up-regulation of chemokine receptor CCR7 and down-regulation of other chemokine receptors dictate its migration exclusively to draining lymph nodes. The CCR7 ligands CCL19 and CCL21 are exclusively expressed by stromal cells in lymph nodes and the high endothelial venules of the afferent lymphatics, where they contribute to the chemokine gradient. OPN is present at a high level at sites of inflammation where antigen uptake and DC activation occur. Our study suggests that although OPN by itself is insufficient to induce directional migration of DCs to lymph nodes, its presence in the milieu provides an amplification mechanism for chemokine-induced G protein-coupled receptor-mediated migration. The same properties were found in DCs derived from both wild type and OPN-deficient mice, showing that production of endogenous OPN by the DCs was not necessary for the enhancement of migration. The phenomenon was also observed in immature DCs responding to chemokines, such as CCL3, suggesting that OPN signaling may enhance leukocyte migration induced by multiple CC chemokines.

We identified three functional domains involved in the potentiation of DC migration to CCL21 by OPN: the well defined RGD domain present in OPN-FL that can potentially bind to integrin αvβ1, αvβ3, αvβ5, α5β1, and α8β1; a new pro-chemotactic sequence, 168RSKSKKFRR176, that spans the thrombin cleavage site Arg168↓Ser169 in OPN-FL; and a third functional domain within the OPN-CTF (Ser169–Asn314). There was no difference in potency between OPN-R and OPN-L, and thus SVVYGLR is not required for the enhancement of chemotaxis, thereby excluding the involvement of α4β1 and α9β1 integrins in this process. Importantly, OPN-FL is the most active protein in potentiating DC migration to CCL21, indicating that its integrity is critical for the maximal pro-chemotactic effect because both OPN-R and OPN-CTF are less potent than OPN-FL. The presence of both OPN-R and OPN-CTF in the medium, mimicking the results of thrombin cleavage, did not recover the full potency of OPN-FL, highlighting the importance of the integrity of the newly identified sequence, 168RSKSKKFRR176, that spans the thrombin cleavage site. Within this sequence, Arg168 is critical for its full activity because the peptide, PR168-T185, demonstrated the same potency as P0 (Ser162–Arg176), whereas PS169-T185 had markedly reduced activity. MMP-3, -7, and -9 cleave OPN at Gly166↓Leu167 (20, 28), with the release of a 5-kDa fragment (Leu167–Asp210) that has been reported to induce chemotaxis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells (20). This fragment contains the newly described pro-chemotactic site. However, a shorter sequence was not identified within this 5-kDa fragment. The receptor site for 168RSKSKKFRR176 on DC remains to be defined.

OPN-CTF (Ser169–Asn314), released from OPN-FL upon thrombin cleavage, clearly enhances chemokine-induced DC migration. Peptide P1 (Ser169–Met193) has a modest potentiating effect compared with P0 (Ser162–Arg176), which is almost certainly due to the loss of the critical Arg168. P7 (Pro289–Asn314) also has a modest enhancement of chemokine-induced DC migration, but it is far less potent than OPN-CTF. The activity of OPN-CTF appears to be dependent on its conformation because it needs to be released from OPN-FL, and thus it is likely that its full activity is not captured by the individual peptides. This is supported by the evidence that, on an equimolar basis, OPN-CTF is significantly more potent than OPNRAA-FLR168A, which contains intact OPN-CTF sequence but differs from OPN-CTF in the N-terminal residues. Moreover, the C-terminal His6 tag significantly reduced the potency of OPN-CTF. In that context, positively charged His6 tag may bind to a negatively charged domain (P3) within OPN-CTF, thereby distorting the requisite conformation required for the optimal expression of its pro-chemotactic activity. Moreover, MAB197B demonstrates drastically different kinetics when binding to OPN-FL, OPN-CTF, OPNRAA-FL-R168A, and OPN-CTFHis6, consistent with the notion that OPN-CTF may exist in different conformations, depending on its adjacent N-terminal sequence or C-terminal modifications. The precise pro-chemotactic domain and mechanism of the OPN-CTF pro-chemotactic activity remain to be further defined.

The enhancement of CCL21-induced migrations of DCs by OPN-FL or OPN-CTF does not require a concentration gradient of OPN but requires its presence in physical proximity to CCL21 during migration. This confirms that CCL21 is the main driver for DC migration in this experimental setting. Chemokine-induced DC migration is driven by asymmetrical signaling through its Gi-coupled G protein-coupled receptor at the leading edge, resulting in polarized cytoskeleton reorganization. In this context, if OPN serves as an amplifier to chemokine signaling, a localized OPN signaling through an unknown receptor in proximity to the leading edge may be required. Alternatively, OPN and CCL21 may form a complex, which then facilitates the engagement of CCL21 to CCR7. However, in the presence of OPN, CCL21 does not induce a stronger calcium transient than CCL21 alone. The exact mechanism(s) by which OPN enhances chemokine-induced DC migration remains to be clarified in future studies.

It is interesting that thrombin cleavage of OPN, leading to the generation of OPN-R and its subsequent cleavage by CPB2 to OPN-L, has been previously shown to modulate cell adhesion in Jurkat cells (12), cultured synoviocytes (2, 29), and some glioblastoma cell lines (11). These effects are mediated by the exposure of the SVVYGLR sequence in OPN-R and the subsequent removal of the C-terminal Arg168 in OPN-L. Elevated OPN-R and OPN-L levels have been found in inflammatory diseases (29). In contrast, thrombin cleavage leads to a diminished, rather than enhanced, augmentation effect of OPN on chemokine-induced DC migration, due to disruption of the sequence 168RSKSKKFRR176, which spans the cleavage site, and the critical role of Arg168. In this regard, the sequence spanning the thrombin cleavage site, 165YGLRSKSKKFRR174, has been shown to bind to heparan sulfate in syndecan-4, which then protects it from enzymatic cleavage (15). It is possible that at the initiation of inflammation, while DC is being activated, cell matrix proteoglycan-bound OPN will maintain its full-length form and exert its maximal potentiating effect on chemokine-induced DC migration despite the presence of thrombin. With further progression of inflammation and local generation of thrombin and CPB2, proteolytic cleavages of OPN will occur that modify its cellular inflammatory properties on DCs, monocytes, and macrophages. Although the DC chemotactic activity in OPN-FL is disrupted by thrombin cleavage, this is compensated by the release of OPN-CTF that assumes a new conformation and has substantial pro-chemotactic activity. Thus, the net effect of proteolytic processing of OPN and its fragments will depend on a complex interplay between the specific cell types involved and their surrounding extracellular milieu (Fig. 11).

FIGURE 11.

Thrombin cleavage of OPN modulates chemokine-induced DC migration. At the initiation of inflammation, while DC is being activated, cell matrix proteoglycan-bound OPN will maintain its full-length form and exert its maximal potentiating effect on chemokine-induced DC migration, mediated by the 159RGD161 and 168RSKSKFRR176 sequences, despite the presence of thrombin. With further progression of inflammation and local generation of thrombin and CPB2, thrombin cleavage of OPN occurs, which will increase cell adhesion by exposing SVVYGLR and allowing better access to RGD in OPN-R while reducing its potentiating effect on DC migration. Further cleavage of OPN-R by CPB2 (or CPN) inactivates SVVYGLR, converting it to OPN-L, and thus decreases cell adhesion mediated by α4β1 and α9β1 integrins. While thrombin cleavage disrupts the RSKSKKFRR pro-chemotactic domain in intact OPN, it releases OPN-CTF (Ser169–Asn314), which assumes a new conformation and possesses substantial pro-chemotactic activity, compensating for the loss of the pro-chemotactic activity in OPN-R and OPN-L.

CD44 and its variants have been identified as OPN receptors by the use of anti-CD44 antibodies (3, 18, 19, 27), but here we did not detect any binding of OPN to CD44 or CD44v6 by two independent techniques. We also showed that anti-CD44 antibody had an inhibitory effect on cell migration by itself, irrespective of the type of chemokine or presence of OPN. Indeed, certain anti-CD44 antibodies, such as IM7, strongly inhibited baseline cell motility, as shown by a decreased non-directional migration to medium alone. The inhibitory effect of anti-CD44 antibodies on cell motility is consistent with the observation that injection of anti-CD44 and CD44v antibodies into an ex vivo ear specimen inhibits emigration of Langerhans cells to the medium (6). In contrast, cells transfected with CD44v6 or/and CD44v7 ectodomain bind to OPN as well as to its thrombin-cleaved N- and C-terminal fragments in a β1 integrin-dependent manner (18). It is possible that binding of the CD44-transfected cells to OPN may be controlled by an inside-out signaling pathway initiated from transfected CD44v6, leading to activation of β1 integrin (30). These results suggest that the observed binding of OPN might be mediated via activated integrins rather than CD44. In other experiments, similar to our data, no binding of OPN to CD44H (CD44, standard form), CD44E (CD44v8–10), CD44v3, v8-v10 (CD44v3 plus v8–10), or CD44v3 was detected (31). Additionally, CD44v3–6-transfected A3 cells do not bind to recombinant OPN either (31). The rat CD44v6 ectodomain used in our study has low homology to its human counterpart, but it has been shown to be active in regulating EGFR-2 in the human system (24). It is possible that the sequence differences in certain residues between the human and rat CD44v6 domain account for the rat CD44v6 not binding to human OPN in our experiments.

Previous studies on OPN and leukocyte migration utilizing murine macrophages suggested that OPN functions as a chemoattractant (19), in contrast to our results showing that OPN is not a chemoattractant itself for DCs. This does not rule out OPN being a direct chemoattractant for macrophages or the possibility that there is an indirect interaction of OPN with CD44 and its variant forms. Discrepancies between macrophages and DCs may be due to intrinsic differences between the two cell types or to the different experimental settings.

In summary, we found that OPN and its fragments did not induce DC migration by themselves but significantly potentiated CCL21-induced DC migration via the well defined RGD and a new pro-chemotactic sequence, 168RSKSKKFRR176, that spans the thrombin cleavage site. Thrombin cleavage disrupts this site, but this loss of pro-chemotactic activity is compensated by the release of OPN-CTF that assumes a new conformation and possesses substantial activity in enhancing chemokine-induced migration of DCs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Véronique Orian-Rousseau (Institute of Toxicology and Genetics, Karlsruhe, Germany) for providing purified rat CD44v6 ectodomain protein. We thank Dr. Xiaomei Ge (Stanford University School of Medicine) for help with purifying GST-OPN-FL and OPN-CTFHis6 for some experiments.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant 5R01HL057530.

- OPN

- osteopontin

- OPN-CTF

- osteopontin C-terminal fragment

- OPN-FL

- full-length OPN

- OPN-L

- OPN-Leu

- OPN-R

- OPN-Arg

- BMDC

- bone marrow-derived dendritic cell

- CCR

- (C-C motif) chemokine receptor

- CCL

- (C-C motif) chemokine ligand

- CI

- 95% confidence interval

- CPB2 and CPN

- carboxypeptidase B2 and N, respectively

- DC

- dendritic cell

- MMP

- matrix metalloprotease

- HBSS

- Hanks' balanced salt solution.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lund S. A., Giachelli C. M., Scatena M. (2009) The role of osteopontin in inflammatory processes. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 3, 311–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sharif S. A., Du X., Myles T., Song J. J., Price E., Lee D. M., Goodman S. B., Nagashima M., Morser J., Robinson W. H., Leung L. L. (2009) Thrombin-activatable carboxypeptidase B cleavage of osteopontin regulates neutrophil survival and synoviocyte binding in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 60, 2902–2912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weiss J. M., Renkl A. C., Maier C. S., Kimmig M., Liaw L., Ahrens T., Kon S., Maeda M., Hotta H., Uede T., Simon J. C. (2001) Osteopontin is involved in the initiation of cutaneous contact hypersensitivity by inducing Langerhans and dendritic cell migration to lymph nodes. J. Exp. Med. 194, 1219–1229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grassinger J., Haylock D. N., Storan M. J., Haines G. O., Williams B., Whitty G. A., Vinson A. R., Be C. L., Li S., Sørensen E. S., Tam P. P., Denhardt D. T., Sheppard D., Choong P. F., Nilsson S. K. (2009) Thrombin-cleaved osteopontin regulates hemopoietic stem and progenitor cell functions through interactions with α9β1 and α4β1 integrins. Blood 114, 49–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bruemmer D., Collins A. R., Noh G., Wang W., Territo M., Arias-Magallona S., Fishbein M. C., Blaschke F., Kintscher U., Graf K., Law R. E., Hsueh W. A. (2003) Angiotensin II-accelerated atherosclerosis and aneurysm formation is attenuated in osteopontin-deficient mice. J. Clin. Invest. 112, 1318–1331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schulz G., Renkl A. C., Seier A., Liaw L., Weiss J. M. (2008) Regulated osteopontin expression by dendritic cells decisively affects their migratory capacity. J. Invest. Dermatol. 128, 2541–2544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Murugaiyan G., Mittal A., Weiner H. L. (2008) Increased osteopontin expression in dendritic cells amplifies IL-17 production by CD4+ T cells in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and in multiple sclerosis. J. Immunol. 181, 7480–7488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smith L. L., Giachelli C. M. (1998) Structural requirements for α9β1-mediated adhesion and migration to thrombin-cleaved osteopontin. Exp. Cell Res. 242, 351–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yokasaki Y., Sheppard D. (2000) Mapping of the cryptic integrin-binding site in osteopontin suggests a new mechanism by which thrombin can regulate inflammation and tissue repair. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 10, 155–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smith L. L., Cheung H. K., Ling L. E., Chen J., Sheppard D., Pytela R., Giachelli C. M. (1996) Osteopontin N-terminal domain contains a cryptic adhesive sequence recognized by α9β1 integrin. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 28485–28491 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yamaguchi Y., Shao Z., Sharif S., Du X. Y., Myles T., Merchant M., Harsh G., Glantz M., Recht L., Morser J., Leung L. L. (2013) Thrombin-cleaved fragments of osteopontin are overexpressed in malignant glial tumors and provide a molecular niche with survival advantage. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 3097–3111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Myles T., Nishimura T., Yun T. H., Nagashima M., Morser J., Patterson A. J., Pearl R. G., Leung L. L. (2003) Thrombin activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor, a potential regulator of vascular inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 51059–51067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kazanecki C. C., Uzwiak D. J., Denhardt D. T. (2007) Control of osteopontin signaling and function by post-translational phosphorylation and protein folding. J. Cell Biochem. 102, 912–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kon S., Ikesue M., Kimura C., Aoki M., Nakayama Y., Saito Y., Kurotaki D., Diao H., Matsui Y., Segawa T., Maeda M., Kojima T., Uede T. (2008) Syndecan-4 protects against osteopontin-mediated acute hepatic injury by masking functional domains of osteopontin. J. Exp. Med. 205, 25–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Barry S. T., Ludbrook S. B., Murrison E., Horgan C. M. (2000) A regulated interaction between α5β1 integrin and osteopontin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 267, 764–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Christensen B., Kläning E., Nielsen M. S., Andersen M. H., Sørensen E. S. (2012) C-terminal modification of osteopontin inhibits interaction with the αVβ3-integrin. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 3788–3797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kazanecki C. C., Kowalski A. J., Ding T., Rittling S. R., Denhardt D. T. (2007) Characterization of anti-osteopontin monoclonal antibodies: Binding sensitivity to post-translational modifications. J. Cell Biochem. 102, 925–935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Katagiri Y. U., Sleeman J., Fujii H., Herrlich P., Hotta H., Tanaka K., Chikuma S., Yagita H., Okumura K., Murakami M., Saiki I., Chambers A. F., Uede T. (1999) CD44 variants but not CD44s cooperate with β1-containing integrins to permit cells to bind to osteopontin independently of arginine-glycine-aspartic acid, thereby stimulating cell motility and chemotaxis. Cancer Res. 59, 219–226 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Weber G. F., Zawaideh S., Hikita S., Kumar V. A., Cantor H., Ashkar S. (2002) Phosphorylation-dependent interaction of osteopontin with its receptors regulates macrophage migration and activation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 72, 752–761 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Takafuji V., Forgues M., Unsworth E., Goldsmith P., Wang X. W. (2007) An osteopontin fragment is essential for tumor cell invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene 26, 6361–6371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Förster R., Davalos-Misslitz A. C., Rot A. (2008) CCR7 and its ligands: balancing immunity and tolerance. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 362–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kawamura K., Iyonaga K., Ichiyasu H., Nagano J., Suga M., Sasaki Y. (2005) Differentiation, maturation, and survival of dendritic cells by osteopontin regulation. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 12, 206–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shinohara M. L., Jansson M., Hwang E. S., Werneck M. B., Glimcher L. H., Cantor H. (2005) T-bet-dependent expression of osteopontin contributes to T cell polarization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 17101–17106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tremmel M., Matzke A., Albrecht I., Laib A. M., Olaku V., Ballmer-Hofer K., Christofori G., Héroult M., Augustin H. G., Ponta H., Orian-Rousseau V. (2009) A CD44v6 peptide reveals a role of CD44 in VEGFR-2 signaling and angiogenesis. Blood 114, 5236–5244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Toda M., Shao Z., Yamaguchi K. D., Takagi T., D'Alessandro-Gabazza C. N., Taguchi O., Salamon H., Leung L. L., Gabazza E. C., Morser J. (2013) Differential gene expression in thrombomodulin (TM; CD141)(+) and TM(−) dendritic cell subsets. PLoS One 8, e72392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sallusto F., Lanzavecchia A. (1994) Efficient presentation of soluble antigen by cultured human dendritic cells is maintained by granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor plus interleukin 4 and downregulated by tumor necrosis factor α. J. Exp. Med. 179, 1109–1118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Weber G. F., Ashkar S., Glimcher M. J., Cantor H. (1996) Receptor-ligand interaction between CD44 and osteopontin (Eta-1). Science 271, 509–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Agnihotri R., Crawford H. C., Haro H., Matrisian L. M., Havrda M. C., Liaw L. (2001) Osteopontin, a novel substrate for matrix metalloproteinase-3 (stromelysin-1) and matrix metalloproteinase-7 (matrilysin). J. Biol. Chem. 276, 28261–28267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Song J. J., Hwang I., Cho K. H., Garcia M. A., Kim A. J., Wang T. H., Lindstrom T. M., Lee A. T., Nishimura T., Zhao L., Morser J., Nesheim M., Goodman S. B., Lee D. M., Bridges S. L., Jr., Consortium for the Longitudinal Evaluation of African Americans with Early Rheumatoid Arthritis (CLEAR) Registry, Gregersen P. K., Leung L. L., Robinson W. H. (2011) Plasma carboxypeptidase B downregulates inflammatory responses in autoimmune arthritis. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 3517–3527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lee J. L., Wang M. J., Sudhir P. R., Chen G. D., Chi C. W., Chen J. Y. (2007) Osteopontin promotes integrin activation through outside-in and inside-out mechanisms: OPN-CD44V interaction enhances survival in gastrointestinal cancer cells. Cancer Res. 67, 2089–2097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Smith L. L., Greenfield B. W., Aruffo A., Giachelli C. M. (1999) CD44 is not an adhesive receptor for osteopontin. J. Cell Biochem. 73, 20–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]