Abstract

Objective

Youth with callous unemotional (CU) behavior are at risk of developing more severe forms of aggressive and antisocial behavior. Previous cross-sectional studies suggest that associations between parenting and conduct problems are less strong when children or adolescents have high levels of CU behavior, implying lower malleability of behavior compared to low-CU children. The current study extends previous findings by examining the moderating role of CU behavior on associations between parenting and behavior problems in a very young sample, both concurrently and longitudinally, and using a variety of measurement methods.

Methods

Data were collected from a multi-ethnic, high-risk sample at ages 2–4 (N = 364; 49% female). Parent-reported CU behavior was assessed at age 3 using a previously validated measure (Hyde et al., 2013). Parental harshness was coded from observations of parent-child interactions and parental warmth was coded from five-minute speech samples.

Results

In this large and young sample, CU behavior moderated cross-sectional correlations between parent-reported and observed warmth and child behavior problems. However, in cross-sectional and longitudinal models testing parental harshness, and longitudinal models testing warmth, there was no moderation by CU behavior.

Conclusions

The findings are in line with recent literature suggesting parental warmth may be important to child behavior problems at high levels of CU behavior. In general, however, the results of this study contrast with much of the extant literature and suggest that in young children, affective aspects of parenting appear to be related to emerging behavior problems, regardless of the presence of early CU behavior.

Keywords: behavior problems, callous-unemotional, conduct problems, deceitful-callous, parenting

Children with early-starting behavior problems are at risk of developing more severe and entrenched forms of antisocial behavior, as well as a wide range of other adverse mental health problems in adulthood (Odgers et al., 2008). Lifetime antisocial behavior is costly to society, requiring education, treatment, or incarceration (Loeber, Farrington, Stouthamer-Loeber, & Van Kammen, 1998). Prospective longitudinal studies support the idea that antisocial behavior has its developmental roots in the preschool years (Shaw, Gilliom, Ingoldsby, & Nagin, 2003). Further, patterns of parenting appear to play an important role in the development of behavior problems, and particularly during early childhood (Shaw, Keenan, & Vondra, 1994). In particular, rejecting parenting behavior (Shaw et al., 2003), coercive patterns of parent-child interaction (Patterson, 1982; Shaw et al., 1994; Scaramella & Leve, 2004) and a lack of positive parent-child engagement (Gardner, Ward, Burton, & Wilson, 2003) have all been longitudinally linked to behavior problems. However, a better understanding is needed of the importance of parenting to the development of conduct problems among different subgroups of children, which has implications for basic research, prevention, and treatment.

One approach to subtype youth with conduct problems has focused on the presence or absence of callous-unemotional (CU) behavior (Frick, Ray, Thornton, & Kahn, 2014). A CU behavior specifier for the diagnosis of Conduct Disorder appears in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), labeled ‘with limited prosocial emotions’. Children and adolescents with high levels of CU behavior show deficits in empathy and guilt, insensitivity to punishment, and reward-focused aggression. Further, youth with high levels of CU behavior demonstrate reduced responsivity and physiological hypoarousal to cues of punishment or distress of others, and a stronger genetic predisposition to antisocial behavior (Frick et al., 2014; Viding & McCrory, 2012). A common notion in the literature is that the behavior problems of youth with high levels of CU behavior develop largely independently of parenting, or that children with these characteristics are less responsive to parenting (e.g., Oxford, Cavell, & Hughes, 2003; Wootton, Frick, Shelton, & Silverthorn, 1997).

Evidence that appears to support this hypothesis has typically come from cross-sectional studies of youth across various developmental stages. In this type of study design (referred to subsequently as a ‘moderator’ design), an interaction term (‘parenting × CU behavior’) is included in regression models, and associations between parenting and conduct problems are tested at high versus low levels of CU behavior. Cross-sectional studies adopting this design have reported that ineffective or negative parenting practices are associated with conduct problems when youth have low but not high levels of CU behavior. This finding has been replicated across different types of samples, including representative (aged 5–7 years, Koglin & Petermann, 2008; aged 7–8 years, Hipwell et al., 2007), clinic-referred (aged 6–9 years, Falk & Lee, 2011; aged 6–13 years Wootton et al., 1997), aggressive (aged 8–10 years, Oxford et al., 2003), and adjudicated (aged 14–19, Edens, Skopp, & Cahill, 2008) samples. The similar pattern of findings found across different types of samples and developmental periods has been taken to suggest that the conduct problems of youth with CU behavior are less malleable and less responsive to parenting.

However, it is interesting to note that many previous moderator studies do not find significant interactions between parenting and CU behavior consistently, although when effects do occur, these results appear to receive greater focus within papers. For example, in the two most commonly cited papers investigating the moderation question (Wootton et al., 351 citations, Google Scholar; Oxford et al., 124 citations, Google Scholar, December 2013), both studies found that the interaction term between parenting and CU behavior was more frequently non-significant across models tested. Furthermore, while the moderator design (whether adopted cross-sectionally or longitudinally) provides an insight into associations between parenting and conduct problems, it is unhelpful when studies extrapolate from the moderator design to draw conclusions about how parenting relates to the development of CU behavior specifically.

In addition, three limitations, common to many previous moderator studies, make it difficult to draw strong conclusions about the nature of associations between parenting, conduct problems, and CU behavior in samples of youth. First, many previous cross-sectional studies have assessed aggressive, male samples with wide age ranges, making findings difficult to generalize to normative or community settings without clinical levels of behavior problems, as well as to samples of females. Indeed, very few studies have investigated samples with a narrow age range, which could enable greater precision in any conclusions drawn about associations between parenting, behavior problems, and CU behavior during specific developmental periods. Second, the majority of previous moderator studies have typically used parent report for all their measures. When parents reflect on their own behavior, including their implementation of different discipline strategies and then evaluate affective and interpersonal characteristics (i.e., CU behavior) of their child, it is unclear how the ratings for one affect the other, making it difficult to interpret studies when parent report is the sole assessment method. Third, it is noteworthy that the majority of previous studies have assessed goal-directed parenting behavior, including monitoring or ‘ineffective discipline’, rather than measures than incorporate parental affect.

Given the socio-emotional and affective characteristics of children with high levels of CU behavior, dimensions of parental affect appear to be a salient target of investigation. This may be particularly relevant during early childhood when parental influence is likely at its peak, due to children’s greater psychological and physical dependence on parents relative to other developmental periods. For example, parental warmth and positive affect have been found to predict conscience development in young children showing fearlessness and insensitivity to punishment (e.g., Kochanska, 1997). In addition, higher maternal warmth experienced during infancy have been shown to predict increases in empathic responding (Kiang, Moreno, & Robinson, 2004) and guilt (Kochanska, Forman, Aksan, & Dunbar, 2005), which are both related to the construct of CU behavior. Finally, it has been argued that parents who display abusive, unemotional or harsh behavior, or who communicate their feelings poorly, may leave their children unable to understand the perspectives or emotional demonstrations of others, and therefore at greater risk for CU- or psychopathic-like behaviors (Daversa, 2010). As such, the associations between dimensions of both positive and negative parental affect and child behavior problems need further investigation at different levels of CU behavior, as these aspects of parenting may provide important targets for intervention.

In an innovative study addressing this question, Pasalich, Dadds, Hawes and Brennan (2011a) examined the moderating role of CU behavior on associations between observed parental warmth versus coercion and conduct problems in clinic-referred boys (age 4–12 years; N = 95). Coercive parenting was coded from observations of family interactions, and parental warmth was coded from five-minute narratives. Pasalich et al. found an intriguing divergence between these dimensions of parenting. Coercive parenting was more strongly positively associated with conduct problems in boys with low levels of CU behavior, whereas parental warmth was more strongly negatively associated with conduct problems in boys with high levels of CU behavior. First, the results suggest that negative parenting appears related to conduct problems among boys who are emotionally reactive and easily aroused (i.e., those with low CU behavior). This association is thought to result in increasingly coercive parent-child interactions over time and further increases in conduct problems (e.g., Dadds & Salmon, 2003). In contrast, the finding that parental warmth was associated with lower levels of conduct problems (Pasalich et al., 2011a) for boys with high CU behavior, supports the hypothesis that strongly positive and mutually warm parent-child interactions may enable a child with CU behaviors to internalize prosocial norms, and develop normative levels of empathy, guilt, and conscience. However, it is difficult to generalize from the small, clinic-referred sample of males reported on by Pasalich et al. (2011a). Specifically, it is unclear if associations between parental affect, conduct problems, and CU behavior would operate in the same way in community samples, comprised of children without the same, high levels of behavior problems, or during specific developmental periods.

Four longitudinal studies to date have adopted a moderator design, which may enable stronger conclusions to be drawn about the direction of effects, although the findings are somewhat mixed across studies. First, Pardini, Lochman, and Powell (2007) investigated predictors of CU and antisocial behavior in a sample of aggressive children over one year (age 9–12 years; N=120). In one of several analyses, Pardini and colleagues found that no ‘parenting × CU behavior’ interaction terms significantly predicted antisocial behavior. Second, Kroneman, Hipwell, Loeber, Koot, and Pardini (2011) found that low maternal warmth predicted faster decreasing levels of conduct problems among girls with high CU behavior (N=1233; aged 7–8 years old at baseline), but the interaction was no longer significant after five years, by which time girls were 12–13 years old. Third, in the same sample as the current study, including families receiving the intervention, Hyde et al. (2013) tested whether age 3 CU behavior moderated the association between age 3 observed positive parenting and growth in child behavior problems from ages 2–4, and found that it did not. The measure of observed positive parenting comprised a range of parenting behaviors, including parental structuring of the environment, verbal communication, contingent use of praise, and neutral parent-child engagement. Finally, Kochanska, Kim, Boldt, and Yoon (2013; N = 102) found that for children with high CU behavior (assessed at age 5½), higher levels of observed mother-child mutually responsive orientation and father-child shared positive affect (score aggregated across ages 3 and 4 ½) were associated with fewer behavior problems at early school age (aggregated across ages 6½ and 8½). Interestingly, this study examined children recruited from the community, suggesting that there may be differences in the conclusions that can drawn about the moderating role of CU behavior on longitudinal associations between parenting and behavior problems depending on type of sample assessed (i.e., normative, high-risk, or clinic).

The aim of the current study was thus to examine the moderating effects of CU behavior on associations between affective dimensions of parenting and behavior problems in toddlers. In doing so, the current study sought to replicate the divergent findings reported on by Pasalich et al. (2011a) in relation to parental warmth versus harshness, and extend this and other previous studies in a number of ways. First, an increasing number of studies have examined CU behavior among preschool aged children or have included a handful of underfives within samples (e.g., Ezpeleta, Osa, Granero, Penelo, & Domènech, 2013; Koglin & Petermann, 2008; Willoughby, Washbusch, Moore & Propper, 2011). Two previous studies carried out in the full sample of the current study (as opposed to just the control group) have also assessed early CU behavior (Hyde et al., 2013; Waller et al., 2012b). However, no previous studies have specifically examined whether CU behavior moderates associations between affective dimensions of parenting and behavior problems at very young ages. As the development of conscience and empathy (i.e., related to the construct of CU behavior) appear to have their roots in the preschool years (e.g., Kochanska & Aksan, 2006; Svetlova, Nichols, & Brownell, 2010), this appears to be a particularly important developmental period to consider. Second, unlike previous studies that have assessed samples with wide age ranges, an advantage of the current study is that all children in the sample were the same age at assessment points, allowing greater clinical precision in any conclusions that can be drawn about interactions between parenting and CU behavior. Third, the measures used were (a) similar dimensions of observed, affective aspects parenting to those investigated by Pasalich et al., and (b) parent reports of affective dimensions of parenting. Specifically, the current study employs multi-informant and parent-reported measures, which enables comparison of different methodologies and potential corroboration across assessment methods, as well as direct comparison with other studies. Fourth, inclusion of both negative and positive affective aspects of parenting in the same model enables the current study to examine unique associations with behavior problems (i.e., the effect of parental warmth, controlling for harshness, and vice versa). In this way, the longitudinal analysis in the current study extends the work of Kochanksa and colleagues, who included only positive affective aspects of parent-child relationships in their models. Fifth, the current study tested whether CU behavior moderated both cross-sectional and longitudinal associations. Finally, for both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses, the current study includes earlier behavior problems in models, which enables the role of parenting/CU behavior in contributing to increases or decreases in behavior problems over time to be examined. It was hypothesized that CU behavior would moderate cross-sectional links between affective measures of parenting and child behavior problems. Specifically, it was hypothesized that, (a) parental harshness would be more strongly positively and cross-sectionally related to child behavior problems in children with low levels of CU behavior at age 3, and (b) parental warmth would be more strongly and cross-sectionally negatively associated with behavior problems in children with high levels of CU behavior at age 3. Because of the mixed pattern of findings reported across the four previous longitudinal studies, no a priori hypotheses were postulated for longitudinal models.

Methods

Participants

Mother–child dyads were recruited between 2002 and 2003 from the Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) in metropolitan Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Eugene, Oregon, and Charlottesville, Virginia. Families were invited to participate if they had a son or daughter between age 2 years 0 months and 2 years 11 months. Screening procedures were developed to recruit families of children at high risk for behavior problems. Recruitment risk criteria were defined as 1 SD above normative averages on screening measures in at least two of the following three domains: (1) child behavior problems (conduct problems – Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory, ECBI; Robinson, Eyberg, & Ross, 1980) or high-conflict relationships with adults – Adult Child Relationship Scale (ACRS); adapted from Pianta, 2001), (2) primary caregiver problems (maternal depression; daily parenting challenges – Parenting Daily Hassles; Crnic & Greenberg, 1990; or self-report of substance or mental health diagnosis, or adolescent parent at birth of first child), and (3) socio-demographic risk (low education achievement). The research protocol was approved by the respective universities’ Institutional Review Boards, and participating primary caregivers provided informed consent. Half of the sample was randomly assigned to receive a parenting intervention (see Dishion et al., 2008). However, the analyses to test the research questions within the current study only use data collected from the control group, who were assessed annually, but did not receive the intervention. At the first assessment, children in the control group (n = 364; 50% female) had a mean age of 28.5 months (SD = 3.27 months). Across sites, primary caregivers in the control group self-identified as European-American (51%), African-American (27%), biracial (13%) and other groups (9%). Most children were living with either both biological parents (37%), either a single/separated parent (42%) or a cohabiting single parent (21%). Sixty-six percent of the sample reported an annual family income below $20,000.

Procedures

Assessments were conducted in the home annually from ages 2 to 4 with mothers, and if present, an alternative caregiver, such as a father or grandmother. Assessments began by introducing the child to age-appropriate toys and having them engage in free play while the mother completed questionnaires. After free play (15 minutes), mother and child participated in a clean-up task (5 minutes), followed by a delay of gratification task (5 minutes), four teaching tasks (3 minutes each), a free play (4 minutes) and clean-up task with the alternative caregiver (4 minutes), the presentation of two inhibition-inducing toys (2 minutes each), and a meal task (20 minutes). All tasks were videotaped and the clean-up, teaching, and meal tasks were used for observational coding of harsh parental behavior. A five-minute speech sample was collected at the end of the assessment. The parent and interviewer were alone in one room when recording the speech sample with minimal distractions. In a scripted prompt, interviewers asked parents, ‘please talk about your thoughts and feelings about your child, and how well you get along together’. Speech samples were used to code expressed parental warmth.

Measures

Demographics questionnaire

A demographics questionnaire was administered at ages 2 and 3, which included questions about parental education and income (Dishion et al., 2008).

CU behavior

CU behavior in this sample was assessed using a measure of deceitful-callous behavior, which was validated in a previous study using the full sample (Hyde et al., 2013). The measure was constructed from parent-reported items from the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000), the ECBI (Robinson et al., 1980) and the ACRS (Pianta, 2001) at age 3. Items were chosen if they reflected an early lack of guilt, lack of affective behavior, deceitfulness, or were similar to items on the Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits (ICU; Frick, 2004). In a previously published study using the full sample, items were examined in an exploratory factor analysis on half the sample, and a confirmatory factor analysis on the other half. The following five items loaded onto a single factor of CU behavior, which was termed deceitful-callous behavior: ‘child doesn’t seem guilty after misbehaving’, ‘punishment doesn’t change his/her behavior’, ‘child is selfish/won’t share’, ‘child lies’, and ‘child is sneaky/tries to get around me’ (see Hyde et al., 2013). There was acceptable internal consistency at age 3 (α = .64), comparable with other measures of CU behavior in older samples of children and adolescents (e.g., Frick, Kimonis, Dandreaux, & Farell, 2003; Hipwell et al., 2007). The reported Cronbach’s alpha may have been affected by the few number of items (n = 5) comprising the deceitful-callous behavior measure, and is lower than the usual accepted cut-off of .70, which should be considered alongside the findings of the study (also see Hyde et al., 2013).

Observed harsh parenting

Observed harsh parenting was defined and validated at age 3 as a multi-dimensional factor, incorporating general parenting qualities (e.g., overall harshness) and specific parental behaviors (e.g., negative comments and negative physical behavior) (Moilanen, Shaw, Dishion, Gardner, & Wilson, 2010), and using two observational coding methods. First, a team of undergraduates, blind to families’ intervention status, coded videotaped family tasks using the Relationship Process Code (RPC; Jabson, Dishion, Gardner, & Burton, 2004), a third-generation code derived from the family process code (Dishion et al., 1983), which has been used extensively in previous research. Coding defines both verbal displays (general conversation or attempts to change the behavior of another) and physical behavior as either positive, negative, or neutral. Three RPC codes were aggregated to form an observed harsh parenting construct: the duration proportions of parental negative verbal, negative directive, or negative physical behavior. Inter-rater reliability was calculated using Noldus Observed Pro 5.0 software based on the duration of each micro-social behavior. To achieve acceptable reliability levels, coders had to achieve 70% agreement and kappa = .70 on two consecutive training assignments, which had been coded by a ‘master coder.’ Fifteen percent of videotapes were coded twice, with acceptable agreement (M team agreement = .87%; kappa = .86). Following micro-social coding, coders completed macro-social ratings on a nine-point scale (1 = not at all, 5 = somewhat; 9 = very much) on the videotaped interactions using the Coder Impressions Inventory (Dishion, Hogansen, Winter, & Jabson, 2004). Harsh parenting was assessed by COIMP items that assessed global displays of parental harshness or rejection towards the child or critical attitudes about child. Specifically, parents were rated on the following six items: the parent ‘gives developmentally inappropriate reasons for desired behavior change,’ ‘displays anger/frustration/annoyance,’ ‘criticizes the child for family problems,’ ‘uses physical discipline,’ ‘actively rejects the child’ and ‘makes statements/gestures indicating the child is worthless.’ The three RPC codes and six macro ratings were standardized and summed to create a composite index of observed harsh parenting (age 3, α = .75; Moilanen et al., 2010).

Parent reported harshness

Parent-reported harshness was assessed using the over-reactivity subscale of the Parenting Scale at ages 2 and 3 (Arnold, O’Leary, Wolff, & Acker, 1993). The Parenting Scale is a 30-item self-report measure of parenting practices comprising three factors (over reactivity, laxness, and verbosity). The 10-item over reactivity subscale used in the current study assesses parental harshness, including reports of displaying anger and irritability, threats and physical punishment. Example items include, ‘when my child misbehaves, I spank, grab, or hit him/her’, ‘when my child misbehaves, I raise my voice or yell’ and ‘when I am upset or under stress, I am picky and on my child’s back’. Items are rated on a 1–7 scale. In the current sample, the alpha was modest at age 3 (α = .58) and harshness was also examined using observational methods (see above).

Expressed parental warmth

The measure of parental warmth was coded from five-minute parental speech samples, using the positive subscale of the Family Affective Attitudes Rating Scale (FAARS; Bullock, Schneiger, & Dishion, 2005) and is referred to as expressed parental warmth. FAARS examines beliefs and feelings expressed by a parent about their child and their relationship. The positive subscale of FAARS has previously been shown to demonstrate adequate reliability and validity in the current sample (Waller et al., 2012a), in an older sample of clinic-referred children (aged 4–11 years old; Pasalich, Dadds, Hawes & Brennan, 2011b), and in a community sample of adolescents (aged 9–17 years old; Bullock & Dishion, 2007). The five positive items (e.g., ‘parent reports a positive relationship with the child’) were rated on a nine-point Likert scale. Coding was based on global impressions of the speech sample and a guideline for scoring is provided in the FAARS coding manual: 1 (no examples), 2–3 (some indication, but no concrete evidence), 3–4 (one or more weak examples), 5 (one concrete, unambiguous but unqualified example, or three or more weak examples of the same behavior), 6–8 (at least one concrete example and one or more weak examples of different behaviors/attributes), and 9 (two or more concrete, unambiguous examples) (see Bullock et al., 2005). Qualifying statements were coded as neutral (i.e., a negative or positive statement followed by a qualifier, such as, ‘but’). The rating of an item between coders was considered an agreement if the scores were within 2 points (e.g., scores of 5 and 7 are an agreement, but scores of 5 and 8 are a disagreement). The total number of agreements over both scales were summed and divided by the total number of items to determine the percent agreement (82.8 % agreement at age 2; 80.7 % agreement at age 3). The positive subscale of FAARS had acceptable internal consistency at age 3 (α = .69).

Parent-reported warmth

Parent reports of warmth in the parent-child relationship were indexed by the 5-item warmth/openness subscale of the ACRS, which was adapted for use with parents and children based on the Student-Teacher Relationship Scale (STRS; Pianta, 2001). The STRS was modified to assess a parent’s positive feelings towards the child and attachment-related behavior, assessing multiple distinct characteristics of the affective quality of the relationship (see Ingoldsby, Shaw, & Garcia, 2001). Each item was rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = definitely not; 2 = not really; 3 = not sure; 4 = somewhat true; 5 = definitely true). A previous study using both the warmth/openness and conflict subscales of the ACRS has shown them to be predictive of later antisocial behavior and social skills (Trentacosta et al., 2011). In the current sample, the warmth/openness subscale had acceptable internal consistency at age 3 (α = .68).

Behavior problems

Behavior problems were assessed using the ECBI (Robinson et al., 1980), a 36-item parent-report behavior checklist. The ECBI assesses behavior problems in children between 2 and 16 years of age via two factors, one that focuses on the perceived intensity of behavior, and another that identifies the degree to which the behavior is a problem for caregivers. The current study used the Problem Factor. Parents rated each item on a seven-point Likert scale (e.g., 1 = never; 4 = sometimes; 7 = always), providing an index of the degree to which they found each behavior problematic. One item had been used in the deceitful-callous behavior measure to assess callous-unemotional behavior (‘lies’) and was therefore removed from the Eyberg Problem Factor score to avoid content overlap between problem behavior outcome and the deceitful-callous behavior measure. The Eyberg Problem factor demonstrated acceptable internal consistency from ages 2 to 4 (α = .84 to .94; Dishion et al., 2008).

Analytic strategy

First, descriptive statistics, bivariate correlations, and partial correlations (controlling for demographic covariates) were computed. Second, regression analyses were used to examine whether CU behavior moderated associations between parenting and child behavior problems. For cross-sectional models, the dependent variable was child behavior problems at age 3. For longitudinal models, the dependent variable was child behavior problems at age 4. In step 1 of all models, the following covariates were entered: child race, child gender, child behavior problems at age 2 (baseline assessment), parent education, and family income. Finally, as data were collected from multiple sites, location was also included as a covariate. In step 2, the main effects were entered: age 3 CU behavior, age 3 parental harshness, and age 3 parental warmth. Finally in step 3, the product terms of ‘CU behavior × parental harshness’, and ‘CU behavior × parental warmth’ were entered. All predictor variables were centered prior to creation of interaction terms and entry into models. Separate models were computed for the observed versus parent-reported measures of parenting. However, given the overlap across the parenting dimensions being assessed within method (i.e., harshness or warmth) and across measurement method (i.e., parent-reported or observed), a further model was computed, in which all parenting measures were included simultaneously. This final model was examined within a general estimating equation (GEE) framework in SPSS, which takes account of dependency between independent variables (i.e., correlations between measures of parenting). To explore significant interactions, associations between parenting variables and child behavior problems were tested at low (1 SD below mean) and high levels of CU behavior (1 SD above mean) (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003).

Attrition

Of the families from the control group entering the study at child age 2 (n = 364), 89% participated at age 3 and 85% at age 4. Selective attrition analyses conducted from 2 to 4 years old revealed no significant differences in project site, race, ethnicity, gender, or child problem behavior (Dishion et al., 2008). Although the amount of missing data was small for individual measures, listwise deletion may have limited the power and biased estimation. Thus, to address missing data, values were imputed (via the EM algorithm in SPSS, version 18.0). Sources of missing data beyond attrition included families refusing to be videotaped, damaged videotapes, or families moving and being unavailable for observations, although still submitting questionnaires via mail.

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the child and parenting variables at ages 2–4. For all subsequent analyses, the observed harsh parenting measure was log-transformed to reduce skew. Bivariate and partial correlations between main study variables are presented in Table 2. As expected, there were significant bivariate correlations between CU behavior and child problem behavior as has been reported elsewhere for this sample (range, r = .21–51, p < .001; see Hyde et al., 2013), and which are of a similar magnitude to the association between behavior problems and CU behavior found in older samples. In addition, there were modest-moderate correlations between the parenting variables and both behavior problems and CU behavior, which emerged for cross-sectional and longitudinal associations. Correlations were of greater magnitude for associations between child behavior and parent-reports of parenting (range, r = .10–.43, p < .001) versus observed parenting (range, r = .11–.25, p < .001). There were moderate correlations within method for parenting measures (observed, r = −.23, p < .001; parent-reported, r = −.27, p < .001) and between measurement methods (harshness, r = .26, p < .001; warmth, r = .27, p < .001). The significant partial correlations (controlling for race, gender, parent income, parent education, and project site) suggest associations between affective dimensions of parenting (across measurement methods) and child behavior problems both cross-sectionally (range, r = .16 – .38, p < .01) and longitudinally (range, r = .20 – .37, p < .01).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the main study variables

| N | M | SD | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavior problems age 2 | 363 | 14.24 | 6.50 | .00 | 33.00 |

| Behavior problems age 3 | 320 | 14.70 | 7.93 | .00 | 36.00 |

| Behavior problems age 4 | 305 | 15.27 | 8.36 | .00 | 35.00 |

| Deceitful-callous behavior age 3 | 324 | .002 | .17 | −.29 | .42 |

| Observed harshness age 3 | 287 | −.35 | 4.53 | −4.25 | 25.70 |

| Observed parental warmth age 3 | 274 | 4.46 | 1.51 | 1.00 | 9.00 |

| Parent-reported harshness age 3 | 324 | 2.77 | .83 | 1.00 | 5.10 |

| Parent-reported warmth age 3 | 324 | 8.51 | 3.12 | 5.00 | 21.00 |

Note: Child age 2 conduct problems were included in models as a covariate

Table 2.

Bivariate and partial cross-sectional and longitudinal correlations between study variables

| Behavior problems age 2 | Behavior problems age 3 | Behavior problems age 4 | CU behavior age 3 | Observed harsh parenting age 3 | Observed parental warmth age 3 | Parent- reported harshness age 3 | Parent- reported warmth age 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavior problems age 2 | .43*** | .31*** | .21*** | .12* | −.04 | .19** | −.04 | |

| Behavior problems age 3 | .47*** | .68*** | .51*** | .18*** | −.21*** | .38*** | −.21** | |

| Behavior problems age 4 | .32*** | .66*** | .46*** | .25*** | −.21*** | .35*** | −.24*** | |

| CU behavior age 3 | .18*** | .50*** | .47*** | .11† | −.18** | .43*** | −.10† | |

| Observed harsh parenting age 3 | .15* | .16* | .24*** | .12† | −.27*** | .26*** | −.12* | |

| Observed parental warmth age 3 | −.04 | −.18** | −.20** | .18** | −.28*** | −.13* | .27*** | |

| Parent-reported harshness age 3 | .13 | .38*** | .37*** | .42*** | .26*** | −.12† | −.23*** | |

| Parent-reported warmth age 3 | −.06† | −.25*** | −.26*** | −.12† | −.16* | .25*** | −.24*** |

p <.10,

p <.05;

p<.01;

p<.001.

Note. Partial correlations (controlling for race, gender, parent income, parent education, and project site) below diagonal and italicized.

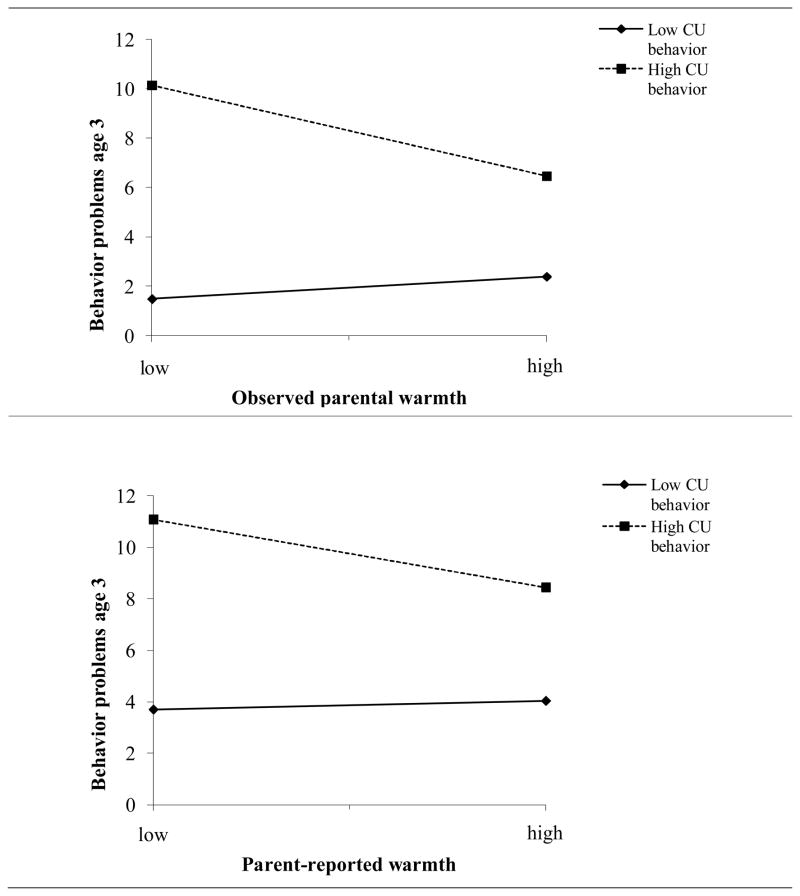

The cross-sectional regression analyses for the separate models (parent-reported versus observed measures of parenting) are summarized in Table 3. For parent-reported measures, the model explained 43% of variance in age 3 child behavior problems. There were significant main effects of more behavior problems (age 2) and more age 3 CU behavior on child behavior problems at age 3. The addition of the interaction terms in step 2 explained a further 3% in variance, and child CU behavior significantly moderated associations between parent-reported warmth and behavior problems at age 3. Post-hoc probing of this significant interaction effect revealed that higher levels of parent-reported warmth were associated with fewer parent-reported behavior problems in children with high (β = −.30, p < .05) versus low (β =.03, ns) levels of CU behavior (see Figure 1). CU behavior did not moderate the cross-sectional association between parent-reported harshness and child behavior problems. For observed parenting measures, the model explained 42% of variance in age 3 behavior problems. There were main effects of more behavior problems (age 2), more CU behavior, and more observed parental harshness on child behavior problems at age 3. In addition, CU behavior significantly moderated the association between observed parental warmth and behavior problems. Higher levels of observed parental warmth were associated with fewer behavior problems in children with high (β = −.26, p < .05) versus low levels of CU behavior (β = −.08, ns).

Table 3.

Regression analysis testing for moderation by CU behavior on the cross-sectional association between parenting variables and child behavior problems at age 3

| Parent-reported measures of parenting | Observed measures of parenting | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Step | Independent variables | β | R2 | ΔR2 | β | R2 | ΔR2 |

| 2. | Behavior problems age 2 | .34*** | .39*** | ||||

| CU behavior age 3 | .37*** | .39*** | |||||

| Parental harshness age 3 | .15** | .07 | |||||

| Parental warmth age 3 | −.07 | .41*** | −.08 | .40*** | |||

|

| |||||||

| 3. | CU behavior × parental harshness | .03 | .07 | ||||

| CU behavior × parental warmth | −.10* | .42*** | .01* | −.12* | .43*** | .03** | |

Note. Covariates entered in Step 1 (not shown) were: child gender, child race, parent education, project site, and family income. The results are presented for the final model, with all predictors entered.

p <.05;

p<.01;

p<.001.

Figure 1.

Cross-sectional associations between parental warmth (observed and parent-reported) and age 3 child behavior problems at high and low levels of CU behavior

For the longitudinal regression models, the same steps were followed with age 4 behavior problems (rather than age 3) as the dependent variable. In the models testing parent-reported measures, there were main effects of more problem behavior at age 2 (β = .22, p < .001), more CU behavior at age 3 (β = .35, p < .001), more parental harshness at age 3 (β = .14, p < .05), and less parental warmth at age 3 (β = −.15, p < .01). In the models testing observational parenting measures, there were main effects of more problem behavior at age 2 (β = .23, p < .001), more CU behavior at age 3 (β = .38, p < .001), and more observed harshness at age 3 (β = .16, p < .05). However, in both sets of models (i.e., parent-reported and observed parenting measures), the interaction terms at age 3 (CU behavior × parenting) were not significant in predicting behavior problems at age 4 (ps > .15).

Finally, all parenting measures (parent-reported and observed) were considered simultaneously in separate cross-sectional (predicting age 3 behavior problems) and longitudinal (predicting age 4 behavior problems) models, within a GEE framework. In the cross-sectional model, there were main effects of more behavior problems at age 2 (unstandardized beta, B = .50, p < .001), more CU behavior at age 3 (B = 2.58, p < .001), more parent-reported harshness at age 3 (B = 1.38, p < .01) and less parent-reported warmth at age 3 (B = −.75, p < .10). However, controlling for non-independence within a GEE framework, there was no significant moderating effect of CU behavior on the associations between any of the parenting measures and child behavior problems. Similarly, in predicting age 4 behavior problems, earlier behavior problems (B = .29, p < .001), CU behavior at age 3 (B = 2.49, p < .001), more age 3 parent-reported harshness (B = 1.06, p < .01), and lower parent-reported warmth at age 3 (B = −1.07, p < .10) were main effects, but there was no moderation of any of the parenting measures by CU behavior (ps range = .63 – .97).

Discussion

This study examined the moderation of cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between affective dimensions of parenting and behavior problems by CU behavior in a large, high-risk sample of preschool children. Previous studies that have investigated questions relating to associations between parenting and youth behavior problems have typically relied on parent reports of parenting, and assessed small, male, clinic-referred samples, often with a wide age range, which makes it hard to generalize findings (e.g., Oxford et al., 2003; Pasalich et al., 2011a; Wootton et al., 1997). Based on the extant literature, it was predicted that parental harshness would be cross-sectionally and positively related to young children’s behavior problems when they had low levels of CU behavior, and that warmth would be cross-sectionally and negatively related to children’s behavior problems when they had high levels of CU behavior. No predictions were made about moderation for longitudinal associations. The findings from both cross-sectional and longitudinal models from the current study have implications for our understanding of the malleability of the behavior problems of very young children and the treatment of early-starting behavior problems.

Contrary to the hypothesis, higher levels of harsh parenting were positively related to child behavior problems at both high and low levels of child CU behavior in cross-sectional and longitudinal models. The findings for observed and parent-reported harsh parenting in this young and large sample of children do not show the same pattern reported in previous studies (e.g., Oxford et al., 2003; Falk & Lee, 2011; Pasalich et al., 2011a; Wootton et al., 1997). This result needs careful interpretation. It may be that in very young children, the effects of parental harshness are important to the development of behavior problems of children regardless of emerging CU behavior. Indeed, at younger ages, it could be that the transactional effects of negative interactions, or coercive parent-child exchanges are yet to have become entrenched. However, at older ages, children with CU behavior may have become insensitive to the effects of punishment or parental discipline and thus, appear to manifest conduct problems that are independent of negative parenting practices, as reported in other studies. The current study therefore highlights the toddler years as a key intervention period to reduce the likelihood that children with CU behavior will develop more entrenched and severe conduct problems. The moderator design does not allow, however, for inferences to be drawn about the direct effect of parenting practices on CU behavior development. However, in previous analyses from this project using the full sample, observed and parent-reported harshness predicted increases in CU behavior from ages 2–4 over and above existing behavior problems (Waller et al., 2012b). Taken together, these findings suggest that at very young ages, parental harshness may have a non-specific effect on increases in both CU behavior and general behavior problems, which could have lasting implications for parental socialization efforts and child conduct problems at later stages of development.

In the cross-sectional analyses, the findings for parental warmth replicate those of Pasalich et al. (2011a). Specifically, the interaction between parental warmth and CU behavior was significant. Higher levels of parental warmth were associated with fewer behavior problems for children with high levels of CU behavior. This finding supports the notion that mutually reciprocal, warm, and positive parent-child interactions may be important for preventing further development of behavior problems in children with CU behavior. It is important to consider, however, that CU behavior did not moderate the effect of parental warmth on later behavior problems when associations were considered in longitudinal models. In addition, CU behavior did not moderate the effects of either parent-reported or observed measures of harshness and warmth when the effects of these measures were tested within a GEE framework.

While the pattern of results in the current study needs to be interpreted with caution, it appears that in very young children, behavior problems are related to both positive and negative affective aspects of parenting regardless of the level of CU behavior. Further, the range of different models tested in the current study highlights the risk of drawing conclusions about associations between parenting, CU behavior, and behavior problems, based on the findings of small, cross-sectional studies. Indeed, it is interesting to consider the findings of the current study alongside highly cited studies, which often feature non-significant ‘parenting × CU behavior’ terms even though the significant effects often receive the greater focus in papers. Indeed, the null findings for the ‘parenting × CU behavior’ interaction terms reported in the current study are in line with a previous analysis in the same sample, which examined associations between parental observed positive behavior support (i.e., parental structuring of the environment, responsiveness, and neutral parent-child engagement) and behavior problems (Hyde et al., 2013), and a previous longitudinal study examining associations parenting and antisocial behavior among high risk children (Pardini et al., 2007). However, the results of the current study contrast somewhat with the longitudinal analyses of Kochanska and colleagues (2013), who examined associations between positive affective parent-child interactions and child outcomes (assessed from 3–8 years old). It is noteworthy that the measure employed by Kochanska et al captured dyadic aspects of the parent-child relationship. In contrast, the current study focused specifically on parental behavioral displays or reports of their harshness and warmth. Further, the current study included both positive and negative dimensions of parenting in the same models, thus examining the effect of parental warmth on child behavior problems controlling for the effects of parental harshness, and vice versa.

Differences in measures aside, the null findings from the current study have several important methodological and theoretical implications for future studies examining the moderating effects of CU behavior on associations between parenting and early-childhood onset of behavior problems. First, both this and previous studies highlight that it is difficult to interpret the findings of the moderator design when the outcome is at a later time point. Moving from a cross-sectional to longitudinal moderation design raises questions about how to specify models. In particular, there could be multiple possible hypotheses about the timing and nature of associations between parenting, CU behavior, and behavior problems, which may be reciprocally related over time. Indeed, the complexity and likely reciprocity of associations between different dimensions of parenting, CU behavior, and behavior problems across developmental periods and types of samples suggest that alternative designs are needed in future studies (see Waller, Gardner, & Hyde, 2013). For example, it is theoretically intuitive that certain early parenting behavior (e.g., lack of warmth, poor attachment, or harshness) may be more important to emerging CU behavior (c.f., Waller et al., 2012b), which then interacts with or increases the frequency of other aspects of negative parental caregiving practices, and subsequently put a child at greater risk of developing behavior problems.

Second, inconsistencies between the findings of the current study and previous studies could relate to the young age of the sample. It is yet to be established how the expression of CU-like behavior in the preschool years relates to CU behavior later in childhood or adolescence. As such, it is difficult to interpret the findings from the current study alongside studies that have examined older children and adolescents with conduct problems, where differentiating according to the level of ‘CU traits’ (i.e., as conceived of as an extension of the adult construct of psychopathy), may have more clinical significance. At the same time, previous studies in this and other sample have highlighted the utility of differentiating CU behavior from oppositional defiant/general externalizing behaviors (e.g., Hyde et al., 2013; Willoughby et al., 2011), particularly as a means of identifying of children who are risk of developing more stable and severe aggression. As such, the current study highlights the need for future studies to examine the continuity or measurement invariance of CU behavior across different developmental periods.

Third, because children with high levels of CU behavior, in this and other samples, display more severe behavior problems (see Hyde et al., 2013), the lack of a longitudinal association between parenting and behavior problems may emerge as a statistical artifact. Specifically, because there appears to be little variability within behavior problems for youth with high levels of CU behavior (i.e., a ceiling effect), it may appear that parenting is not a predictor for this subgroup (see Waller et al., 2013). The null findings could thus be re-conceptualized as parenting not moderating the robust association between child CU behavior and behavior problems. This notion is supported by the fact that CU behavior was always a strong predictor in models, an effect that may have been exacerbated by relying on parent reports for both child behavior problems and CU behavior. Future studies are thus needed that incorporate reports of child behavior from multiple informants. The different pattern of findings for models depending on whether a GEE framework was adopted in the current study also highlights the need for future studies to consider how analytic technique influences findings and/or study conclusions, especially in how this may relate to overlap between variables, including measures of parenting or child behavior.

There are a number of strengths to the present study, including the large sample size, use of observed measures, and prospective, longitudinal measurement from toddler age. At the same time, the results should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, the variance explained by the significant interaction terms in the cross-sectional models was modest (1–3%). Thus the clinical relevance of the cross-sectional interaction effects may be minimal, especially when considered alongside the null findings for the longitudinal models and GEE analyses. Other (unobserved) factors could also be important to the development of behavior problems among children with high CU behavior, which needs further investigation in future studies (e.g., inattention to the eye region of caregivers and ensuing deficits in conscience and socioemotional processing; c.f., Dadds et al., 2013; also see Hyde, Waller, & Burt, 2013). Second, it is yet to be established how and whether the CU behavior measure in this sample is prognostic of ‘CU traits’ in middle childhood and adolescence, especially given that it contained a greater preponderance of deceitful and fewer unemotional items than traditional ‘CU traits’ scales. Further, the use of cut-off scores to create subgroups of youth with high versus low levels of CU behavior has yet to be evaluated in older samples of children and adolescents, let alone in very young samples. Third, while the observed measure of parental warmth was derived from global coding of speech samples, it was not based on direct observations of parent behavior, relying on parental narratives about their relationship with their child. However, the FAARS measure was used in an attempt to enable comparability with the findings of Pasalich et al. (2011a), and has been shown in a previous study in this sample to relate to observed positive parental behavior support during parent-child interactions (Waller et al., 2012a). Fourth, the alphas for the measures of CU behavior and parent-reported harshness were below usual acceptable cut-offs, which should be considered alongside the findings. Finally, the current study focused on low-income children with multiple risk factors, including family risk (e.g., maternal depression, substance use), and early child problem behavior. Due to the screening procedure, some families were recruited because of family or socioeconomic risk, whereas others may have qualified because of early child problem behavior. Regardless, it is unclear whether the results would be generalizable to children from higher-income families with fewer risk factors.

The results from the current study suggest that at very young ages, children with behavior problems are likely to benefit from interventions that both reduce parental harshness and simultaneously improve the positive affective quality of the parent-child relationship, and importantly, regardless of their level of CU behavior. Future studies are needed to replicate the findings in similarly young samples (i.e., during toddler years) because they have implications for the malleability of emerging conduct problems in the presence of high CU behavior that do not fit with current and prevailing opinions in the literature relating to older samples. However, the current study also raises questions about the importance of study design to findings. The majority of previous studies investigating associations between parenting and conduct problems at high versus low levels of CU behavior have adopted cross-sectional designs, focusing on an outcome of conduct problems. Future studies are needed to investigate longitudinal associations between specific dimensions of parenting, and comparing their effects on increases/decreases in ‘CU traits’ versus conduct problems (see Waller et al., 2013). In particular, studies that employ cross-lagged models to directly examine longitudinal associations between affective dimensions of parenting and CU behavior, controlling for the presence of behavior problems, would be helpful, paying particular attention to the developmental age period being studied.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant 5R01 DA16110 from the National Institutes of Health, awarded to Dishion, Shaw, Wilson, & Gardner. We thank families and staff of the Early Steps Multisite Study.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

Contributor Information

Rebecca Waller, Department of Psychology, University of Michigan, USA.

Frances Gardner, Department of Social Policy and Intervention, University of Oxford, UK.

Daniel S. Shaw, Department of Psychology, University of Pittsburgh, USA

Thomas J. Dishion, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University, USA

Melvin N. Wilson, Department of Psychology, University of Virginia, USA

Luke W. Hyde, Department of Psychology, Center for Human Growth and Development, Survey Research Center of the Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, USA

References

- Achenbach T, Rescorla L. Manual for the ASEBA Preschool Forms and Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. (DSM-5) [Google Scholar]

- Arnold D, O’Leary S, Wolf L, Acker M. The parenting scale: A measure of dysfunctional parenting in discipline situations. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5:137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Bullock B, Schneiger A, Dishion T. Manual for coding five-minute speech samples using the Family Affective Rating Scale (FAARS) Available from Child and Family Centre; 195 W. 12th Avenue, Eugene, Oregon 97401: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bullock B, Dishion T. Family process and adolescent problem behavior: integrating relationship narratives into understanding development and change. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:396–407. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31802d0b27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West S, Aiken L. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Crnic KA, Greenberg MT. Minor parenting stresses with young children. Child Development. 1990;57:209–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds M, Salmon K. Punishment insensitivity and parenting: Temperament and learning as interacting risk for antisocial behavior. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2003;6:69–86. doi: 10.1023/a:1023762009877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Allen JL, McGregor K, Woolgar M, Viding E, Scott S. Callous-unemotional traits in children and mechanisms of impaired eye contact during expressions of love: a treatment target? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, epub ahead of print. 2013 doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daversa M. Early environmental predictors of the affective and interpersonal construct of psychopathy. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2010;54:6–21. doi: 10.1177/0306624X08328754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion T, Gardner K, Patterson G, Reid J, Spyrou S, Thibodeaux S. Unpublished report. Oregon Social Learning Center; Eugene, OR: 1983. The family process code: A multidimensional system for observing family interaction. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion T, Hogansen J, Winter C, Jabson J. Unpublished manual. Child and Family Center; Eugene, OR: 2004. Coder impressions inventory. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion T, Shaw D, Connell A, Gardner F, Weaver C, Wilson M. The Family Check-Up with high-risk indigent families: Preventing problem behavior by increasing parents’ positive behavior support in early childhood. Child Development. 2008;79:1395–1414. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edens J, Skopp N, Cahill M. Psychopathic features moderate the relationship between harsh and inconsistent parental discipline and adolescent antisocial behavior. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:472–476. doi: 10.1080/15374410801955938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezpeleta L, Osa NDL, Granero R, Penelo E, Domènech JM. Inventory of callous-unemotional traits in a community sample of preschoolers. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2013;42(1):91–105. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.734221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk A, Lee S. Parenting behavior and conduct problems in children with and without Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): moderation by callous-unemotional traits. Journal of Psychopathology & Behavioral Assessment. 2011;32:172–181. [Google Scholar]

- Frick P, Kimonis E, Dandreaux D, Farell J. The 4-year stability of psychopathic traits in non-referred youth. Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 2003;21:713–736. doi: 10.1002/bsl.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick P. Unpublished rating scale. 2004. The Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits. [Google Scholar]

- Frick P, Ray JV, Thornton LC, Kahn RE. Can callous-unemotional traits enhance the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of serious conduct problems in children and adolescents? A comprehensive review. Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140:1–57. doi: 10.1037/a0033076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner F, Ward S, Burton J, Wilson C. Joint play and the early development of conduct problems in children: A longitudinal observational study of pre-schoolers. Social Development. 2003;12:361–379. [Google Scholar]

- Hipwell A, Pardini D, Loeber R, Sembower M, Keenan K, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Callous-unemotional behaviors in young girls: Shared and unique effects relative to conduct problems. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:293–304. doi: 10.1080/15374410701444165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde LW, Waller R, Burt SA. Improving treatment for youth with Callous-Unemotional traits through the intersection of basic and applied science: Commentary on Dadds et al., (2013) Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12274. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde L, Shaw D, Gardner F, Cheong J, Dishion T, Wilson M. Dimensions of callousness in early childhood: Links to problem behavior and family intervention effectiveness. Development & Psychopathology. 2013;25:347–363. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412001101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingoldsby E, Shaw DS, Garcia M. Intra-familial conflict in relation to boys’ adjustment at school. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:35–52. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401001031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabson J, Dishion T, Gardner F, Burton J. Unpublished manual. Child and Family Center; Eugene, OR: 2004. Relationship process code V-2.0 training manual: A system for coding relationship interactions. [Google Scholar]

- Kiang L, Moreno AJ, Robinson JL. Maternal preconceptions about parenting predict child temperament, maternal sensitivity, and children’s empathy. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:1081–1092. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G. Mutually responsive orientation between mothers and their young children: Implications for early socialization. Child Development. 1997;62:284–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Forman DR, Aksan N, Dunbar SB. Pathways to conscience: Early mother–child mutually responsive orientation and children’s moral emotion, conduct, and cognition. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:19–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Aksan N. Children’s conscience and self-regulation. Journal of Personality. 2006;74:1587–1617. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00421.x. (Special Issue on Self-Regulation and Personality) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Kim S, Boldt LJ, Yoon JE. Children’s callous-unemotional traits moderate links between their positive relationships with parents at preschool age and externalizing behavior problems at early school age. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.111/jcpp.12084. epub ahead of publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroneman L, Hipwell A, Loeber R, Koot H, Pardini D. Contextual risk factors as predictors of disruptive behavior disorder trajectories in girls: the moderating effect of callous-unemotional features. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2011;52:167–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02300.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koglin U, Petermann F. Inkonsistentes erziehungsverhalten: Ein risikofaktor für aggressive verhalten? Zeitschrift für Psychiatrie, Psychologie & Psychotherapie. 2008;56:285–291. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Farrington DP, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Van Kammen WB. Antisocial behavior and mental health problems: Explanatory factors in childhood and adolescence. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Moilanen K, Shaw D, Dishion T, Gardner F, Wilson M. Predictors of longitudinal growth in inhibitory control in early childhood. Social Development. 2010;19:326–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00536.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odgers CL, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Broadbent JM, Dickson NP, Hancox R, et al. Female and male antisocial trajectories: from childhood origins to adult outcomes. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:673–716. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxford M, Cavell T, Hughes J. Callous/unemotional traits moderate the relation between ineffective parenting and child externalizing problems: A partial replication and extension. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:577–585. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardini D, Lochman J, Powell N. The development of callous-unemotional traits and antisocial behavior in children: are there shared and/or unique predictors? Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:319–333. doi: 10.1080/15374410701444215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasalich D, Dadds M, Hawes D, Brennan J. Callous-unemotional traits moderate the relative importance of parental coercion versus warmth in child conduct problems: An observational study. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2011a;52:1308–1315. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasalich D, Dadds M, Hawes D, Brennan J. Assessing relational schemas in parents of children with externalizing behavior disorders: reliability and validity of the family affective attitude rating scale. Psychiatry Research. 2011b;185:438–443. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Coercive family process. Castalia; Eugene, OR: 1982. A social learning approach; III. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC. Student-teacher relationship scale: Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson E, Eyberg S, Ross A. The standardization of an inventory of child conduct problem behaviors. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1980;9:22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella L, Leve L. Clarifying parent–child reciprocities during early childhood: the early childhood coercion model. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2004;7:89–107. doi: 10.1023/b:ccfp.0000030287.13160.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw D, Keenan K, Vondra J. Developmental precursors of externalizing behavior: ages 1 to 3. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:355–364. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw D, Gilliom M, Ingoldsby E, Nagin DS. Trajectories leading to school-age conduct problems. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svetlova M, Nichols S, Brownell C. Toddlers’ prosocial behavior: From instrumental to empathic to altruistic helping. Child Development. 2010;81:1814–1827. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01512.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trentacosta CJ, Criss MM, Shaw DS, Lacourse E, Hyde LW, Dishion TJ. Antecedents and outcomes of joint trajectories of mother-son conflict and warmth during middle childhood and adolescence. Child Development. 2011;82:1676–1690. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01626.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viding E, McCrory EJ. Why should we care about measuring callous-unemotional traits in children? British Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;200(3):177–178. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.099770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, Gardner F, Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, Wilson MN. Validity of a brief measure of parental affective attitudes in high-risk preschoolers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012a;40(6):945–955. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9621-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, Gardner F, Hyde LW, Shaw DS, Dishion T, Wilson M. Do harsh and positive parenting predict reports of deceitful-callous behavior in early childhood? Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2012b;53(9):946–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, Gardner F, Hyde L. What are the associations between parenting, callous-unemotional traits, and antisocial behavior in youth? A systematic review of evidence. Clinical Psychology Review. 2013;33(4):593–608. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby MT, Waschbusch DA, Moore GA, Propper CB. Using the ASEBA to screen for callous unemotional traits in early childhood: factor structure, temporal stability, and utility. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2011;33:19–30. doi: 10.1007/s10862-010-9195-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wootton J, Frick P, Shelton K, Silverthorn P. Ineffective parenting and childhood conduct problems: the moderating role of callous-unemotional traits. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:301–308. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.65.2.292.b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]