Abstract

Background

Many individuals with schizophrenia experience remission of prominent positive symptoms but continue to experience impairments in real world functioning. Residual negative and depressive symptoms may have a direct impact on functioning and impair patients’ ability to use the cognitive and functional skills that they possess (competence) in the real world (functional performance).

Methods

136 individuals (100 men, 36 women) with schizophrenia were classified as having primarily positive symptoms, primarily negative symptoms, primarily depressive symptoms, or undifferentiated symptom profiles. Performance based measures of cognition and adaptive and interpersonal functional competence were used, along with ratings of real world behavior by high contact clinicians. Assessments were performed at baseline and at an 18-month follow-up.

Results

The relationships between neurocognition and capacity / performance were not moderated by symptom group ps > .091; neurocognition predicted capacity and performance for all groups ps < .001. The relationship between adaptive competence and adaptive performance was moderated by symptom group, ps < .01, such that baseline competence only predicted future performance ratings for participants with primarily positive or undifferentiated symptoms, and not for individuals with primarily negative or depressive symptoms. This same moderation effect was found on the relationship between interpersonal competence and interpersonal performance, ps < .002.

Conclusions

Residual negative and depressive symptoms are distinct constructs that impede the use of functional skills in the real world. Depressive symptoms are often overlooked in schizophrenia but appear to be an important factor that limits the use of functional ability in real world environments.

1. Introduction

The concept of functional recovery transcends the traditional medical model of symptom remission (Andreasen et al., 2005) to include the attainment of meaningful roles in the community (Harvey & Bellack, 2009). As such, community functioning is an increasingly important treatment target for schizophrenia. Unfortunately, full functional recovery is rarely attained and even less frequently maintained, even after symptoms have remitted (Robinson et al., 1999; 2004). Profound impairments persist after clinical stabilization across multiple domains of functioning, including occupational and academic achievement, interpersonal relationships, and independent living (Abdallah et al., 2009; Bowie et al., 2008; Green et al., 2004).

Functioning can be considered to consist of two distinct constructs: competence (what one can do under optimal conditions) and performance (what one actually does in the real world; Gupta et al., 2012). Competence, typically indexed by performance on measures of various cognitive and functional abilities, accounts for a substantial, but still minority, portion of the variance in performance, typically indexed through ratings of community behaviour by third-party observers. In a recent report, Gupta et al., (2012) examined this competence-performance discrepancy and found that both intrinsic (e.g., neurocognitive ability, depressive symptoms, motivation) and environmental (e.g., residential and vocational opportunities, hospitalization, disability rules) factors predict whether an individual under-performs in the real world relative to performance on laboratory measures of various functional and cognitive abilities.

Positive and negative symptoms have been consistently found to be minimally related to functional competence, but they are often found to be associated with poorer everyday real world performance even after other factors, such as functional competence, are considered (e.g., Bowie et al., 2006; 2008; 2010; Leifker et al., 2009; Sabbag et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2002; Stefanoloulou et al., 2011). Positive symptoms tend to respond well to pharmaceutical treatment, but approximately 15-20% of people with schizophrenia experience treatment-resistant negative symptoms (Buchanan, 2007) that are strongly associated with poor functional outcomes (e.g., Herbernet & Harrow, 2004; Milev et al., 2005; Leifker et al., 2009; Sabbag et al., 2012). Depressive symptoms are also important to consider in schizophrenia, and are present in up to 83% of patients at first admission for schizophrenia (Häfner et al., 2005), 40% meeting lifetime criteria for major depression (Harvey et al., in press), and in any month approximately 35% of patients with schizophrenia present with at least one of the core symptoms of depression (an der Heiden et al., 2005). Patients in the community still experience symptoms of depression, even after remission of positive symptoms (Pogue-Geile, 1989; Baynes et al., 2000). These residual depressive symptoms are overlooked in schizophrenia, yet they may interfere with everyday task performance (Bowie et al., 2006; 2008; 2010; Harvey, 2011; Sabbag et al., 2012). Thus, negative and depressive symptoms provide insight into persistent functional impairment in spite of positive symptom reduction. Although negative symptoms are well known to be associated with functional disability, depressive symptoms in schizophrenia have not yet received much attention in the research literature.

The purpose of this study is to examine the longitudinal moderating effect of symptomology, particularly depressive symptoms, on the relationship between cognitive and functional competence with functional performance in schizophrenia. We examined individuals with four distinct symptom profiles: (1) positive symptoms (with minimal negative symptoms); (2) negative symptoms (with minimal positive symptoms); (3) depressive symptoms (with minimal concurrent positive or negative symptoms); and (4) undifferentiated symptoms (could not be classified into one of the above categories). To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study to examine functioning in individuals with schizophrenia whose negative and positive symptoms were minimal and whose only active symptoms were depressive symptoms.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

People with a diagnosis of either schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (100 men, 36 women) were assessed twice at 18 month intervals. Exclusion criteria included any DSM-IV (APA, 1994) Axis I disorder other than schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, a Mini-Mental State Examination (Folstein et al., 1975) score below 18, Wide Range Achievement Test (WRAT-3; Wilkinson, 1993) reading equivalent of grade 6 or less, or any medical illnesses that affect cognitive functioning (e.g., traumatic brain injury, epilepsy, cerebrovascular accident, multiple sclerosis). A trained research assistant completed the Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History (CASH; Andreasen et al., 1992) with each participant, and a senior clinician confirmed the diagnosis.

2.2. Measures

All participants completed the assessments in a fixed order. All raters received extensive training and were subject to reevaluations of their performance every three months. Raters were trained to adequate reliability on symptom ratings yielding intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) ranging from .86 to .92.

2.2.1. Symptom Assessment

Severity of clinical symptoms was assessed with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; Kay, 1991). Following a structured interview, seven positive symptoms, seven negative symptoms, and sixteen general aspects of psychopathology were rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale. Participants also completed the Beck Depression Inventory, second edition (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996) – a self-report measure of depressive symptoms consisting of 21 questions with response options ranging from 0 (absence of symptom) to 3 (symptom is severe). In accordance with previous studies (Bowie et al., 2006; Bowie et al., 2008), the BDI was used instead of the Depression item on the PANSS (PANSS-D) due to the greater breadth of symptom information obtained (Lindenmayer et al., 1992). The correlation between the BDI-II and the PANSS-D in the present sample was r = .51, p < .001.

2.2.2. Neurocognition

The following measures of neurocognition were included: Trail-Making Test Parts A and B (Reitan & Wolfson, 1993); category naming (animal naming; Spreen & Strauss, 1998); phonological fluency (F, A, S; Spreen & Strauss, 1998); the Digit Span Distraction Test (DSD; Oltmanns & Neale, 1975); Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT; Morris et al., 1989) learning trials 1 to 5, RAVLT short delay free recall, and recognition; Wisconsin Card Sorting Test 64-card computerized version (WCST; Heaton et al., 1993); the Constructional Praxis test (Morris et al., 1989); and the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Third Edition (WAIS-III; Wechsler, 1998) digit span, digit symbol, and letter-number sequencing subtests. A global cognitive composite was computed by creating an equally weighted average of all of the cognitive measures after each was converted into to z-scores based on norms in the instruments’ manuals, as we have previously reported (Bowie et al., 2006, 2008).

2.2.3. Performance-Based Functional Capacity

The UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment Battery (UPSA; Patterson et al., 2001a) is designed to assess functional capacity. The UPSA measures performance in a number of everyday functional domains (e.g., transportation, planning recreation) through the use of props and standardized skills performance situations. A total UPSA score is calculated based on the number of correct responses.

The Social Skills Performance Assessment (Patterson et al., 2001b) is a measure of social skills. After a practice trial, the patients initiate and maintain a conversation for 3 minutes in each of two situations: greeting a new neighbor and calling a landlord to request a repair for a leak. These sessions were audiotaped and scored by a trained rater who was unaware of diagnosis and all other data. Dimensions of social skills scored include fluency, clarity, focus, negotiation ability, persistence, and social appropriateness. Raters were trained to the gold standard ratings of the instrument developers (ICC = .86) and high interrater reliability was maintained at 3 months (ICC = .87). The mean of the ratings on these variables across the two measures was used in this study.

2.2.4. Real world Functional Performance

The Specific Level of Function Scale (Schneider & Struening, 1983) is a 43-item observer-rated scale that provides a report of behavior and real world functioning; the two specific domains examined in this study included the Interpersonal (e.g., initiating, accepting, and maintaining social contacts), and Activities (e.g., paying bills, use of leisure time, use of public transportation) subscales.

Ratings by a high contact clinician, who indicated that they knew the patient at least “very well” on the SLOF 5-point Likert scale, were made based on the amount of assistance required to perform real world skills or frequency of the behavior. SLOF raters were in a position to observe behaviour in the community, and were unaware of performance on any other measures.

2.3. Data Analysis

Hierarchical regression analyses determined whether functional competence accounted for a significant proportion of variance beyond that accounted for by symptoms, when predicting functional performance. The severity of positive, negative, and depressive symptoms was used in these analyses, and was calculated as the mean rating of the PANSS items used to create the symptom categories outlined below. Symptoms were always entered into the first block, and the measure of functional competence was entered in the second block.

We also conducted moderated regression analyses using symptom group as a categorical moderator. We were interested in moderation analyses that would address the clinical issue of symptom presence or remission and we selected those items that the APA remission working group viewed as central features of the illness and relevant to remission from symptoms.

The presence of positive symptoms was defined as a score of 4 or greater (indicating a moderate level of symptom) on at least one of the following core items on the PANSS positive symptoms domain: Delusions, Conceptual Disorganization, or Hallucinations. The presence of negative symptoms was defined as a score of 4 or greater on at least one of the following PANSS items: Blunted Affect, Emotional Withdrawal, Social Withdrawal, or Disturbance of Volition. Absence of the symptoms was defined as a score of less than 4 (indicating that symptom is either entirely absent, or that the symptom is questionable or minor). We did not include other variables because of their poor loading on positive and negative symptom factors (e.g., White et al, 1997). The presence of depressive symptoms was defined as a BDI score greater than or equal to 11, a clinical cutoff that indicates at least a mild level of depressive symptoms (Beck, 1988).

Participants were classified into groups according to their primary type of symptom: positive, negative, depressive, or undifferentiated. The positive group had positive symptoms with minimal negative symptoms; the negative group had negative symptoms with minimal positive symptoms; the depressive group had depressive symptoms with minimal positive or negative symptoms; and the undifferentiated group could not be classified into one of the above categories. Demographic information is included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic information by Group

| Positive Symptoms (n = 26) |

Negative Symptoms (n = 17) |

Depressive Symptoms (n = 25) |

Undifferentiated Symptoms (n = 68) |

Test Statistic | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Diagnosis (Schizophrenia: Schizoaffective) | 22 : 4 | 12 : 5 | 13 : 12 | 56 : 12 | χ2=10.6 | .014 |

| Gender (men:women) | 17 : 9 | 13 : 4 | 18 : 7 | 52 : 16 | χ2 = l.3 | .73 |

| Age Mean (SD) | 55.2 (13.4) | 57.3 (10.8) | 54.2 (6.2) | 57.6 (6.5) | F = 1.15 | .333 |

| Years of Education Mean (SD) | 12.5 (3.1) | 12.7 (1.7) | 13.0 (3.4) | 13.0 (2.05) | F = .304 | .822 |

| Age at First Hospitalization Mean (SD) | 24.4 (10.5) | 24.8 (14.3) | 34.5 (11.2) | 25.4 (9.2) | F = 4.77 | .004 |

| Independent Livinga % | 69.6% | 64.3% | 72.0% | 66.1% | χ2=.393 | .942 |

Living independently in the community without supervision

3. Results

3.1 Relationship Between Negative and Depressive Symptoms

Given the conceptual overlap between some negative and depressive symptoms, we calculated Spearman’s rank correlations to determine whether any of the negative symptoms were correlated significantly with the severity of depressive symptoms. Total BDI score was not associated with blunted affect, emotional withdrawal, or disturbance of volition, ps > .313, but was significantly, but minimally, correlated with the negative symptom category of passive/apathetic social withdrawal, r = .21, p = .019.

We also conducted non-parametric analyses to determine whether having depressive symptoms was associated with having negative symptoms, according to our criteria. There was no significant association, Cramer’s V = 0.095, p = .286, indicating that negative and depressive symptoms, as measured in the present study, are generally distinct constructs. A weak association was observed between the presence of negative symptoms and the presence of positive symptoms, Cramer’s V = .234, p = .008.

3.2. Hierarchical Regression Models

Results of the hierarchical regression analyses are presented in Table 2. No symptoms significantly predicted SLOF Activities, and in all models, scores on the UPSA accounted for a significant proportion of variance beyond that accounted for by symptoms. Only negative symptoms significantly predicted the SLOF Interpersonal domain, and in all models, SSPA accounted for a significant proportion of variance beyond that accounted for by symptoms.

Table 2.

Hierarchical regression results using symptoms as continuous variables. Symptom variable was entered into the first block and functional competence measure was entered into the second block.

| Model | R | R2 Change | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLOF Activities | Positive Symptoms | .047 | .002 | .594 |

| Positive Symptoms, UPSA | .226 | .051 | .011 | |

|

| ||||

| Negative Symptoms | .131 | .017 | .135 | |

| Negative Symptoms, UPSA | .277 | .059 | .005 | |

|

| ||||

| Depressive Symptoms | .039 | .002 | .659 | |

| Depressive Symptoms, UPSA | .229 | .051 | .010 | |

|

| ||||

| SLOF Interpersonal | Positive Symptoms | .107 | .011 | .225 |

| Positive Symptoms, SSPA | .298 | .078 | .001 | |

|

| ||||

| Negative Symptoms | .344 | .118 | < .001 | |

| Negative Symptoms, SSPA | .419 | .057 | .004 | |

|

| ||||

| Depressive Symptoms | .066 | .004 | .462 | |

| Depressive Symptoms, SSPA | .275 | .071 | .002 | |

3.3. Moderated Regression Analyses

All continuous independent variables were centered at the mean before being entered into the regression equation in order to reduce multicollinearity. The categorical variable of primary symptom type was dummy coded such that one variable represented the comparison between the positive symptom group and depressive symptom group, one variable represented the comparison between the negative symptom group and depressive symptom group, and the other variable represented the comparison between the undifferentiated group and the depressive symptom group.

3.3.1. Cognition Predicting Functional Capacity / Performance

The neurocognition composite score at baseline significantly predicted the UPSA scores at 18 month follow-up such that better neurocognition was associated with better performance on the UPSA, B = 4.56, t = 7.74, p < .001. Baseline neurocognition was also a significant predictor of SLOF Activities at 18 month follow-up, B = 5.91, t = 4.14, p < .001.

There was no significant moderating effect of symptoms on the relationship between the neurocognitive composite score at baseline and UPSA at 18 month follow-up, ps > .191. There was also no significant moderating effect of symptoms on the relationship between cognition at baseline and SLOF Activities at 18 month follow-up, ps > .091.

3.3.2. Capacity Predicting Performance

There was a significant moderating effect of symptoms on the relationship between UPSA at baseline and SLOF Activities at 18 month follow-up such that the relationship was greater for individuals with primarily positive symptoms, B = 1.15, F(1,128) = 10.06, p = .002, and individuals with undifferentiated symptoms, B = 0.74, F(1,128) = 6.71, p = .01, compared to individuals with only depressive symptoms. There was no difference in the magnitude of this relationship between individuals with primarily negative symptoms and individuals with only depressive symptoms, p = .824.

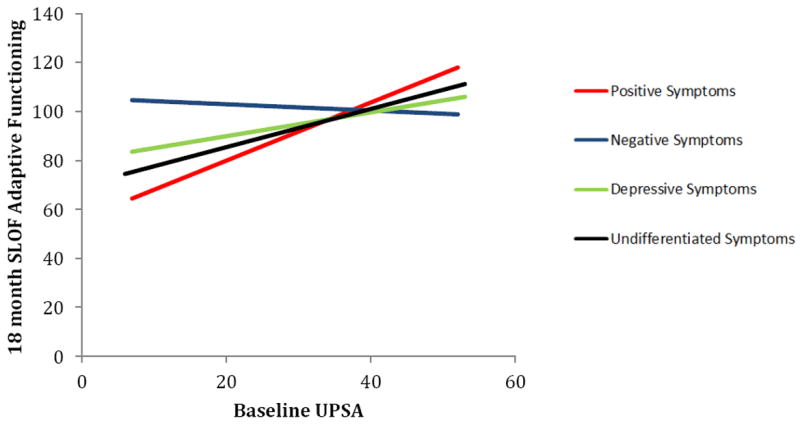

Simple slopes follow-ups were conducted to determine for which symptom subgroups baseline UPSA predicted SLOF Activities at 18 months (Figure 1). Baseline UPSA significantly predicted SLOF Activities at 18 months for individuals with primarily positive symptoms, B = 1.19, F(1,128) = 12.50, p = .001, 95% CI = .52 to 1.86, and individuals with undifferentiated symptoms, B = 0.78, F(1,128) = 9.58, p = .002, 95% CI = .28 to 1.28, but not for individuals with primarily negative symptoms, B = -.13, F(1,128) = 0.03, p = .864, 95% CI = -1.61 to 1.4, or primarily depressive symptoms, B = .04, F(1,128) = .095, p = .759, 95% CI = -.22 to .31.

Figure 1.

Prediction of SLOF (activities in the community) at 18 month follow-up by UPSA (adaptive competence) at baseline, by symptom group.

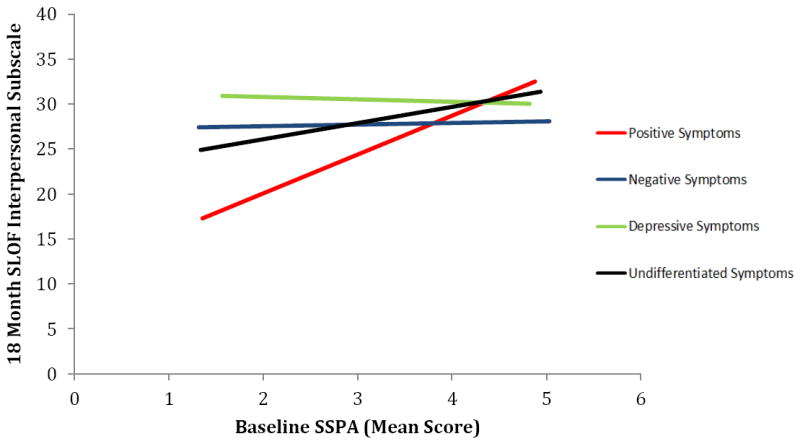

We calculated a regression model using SSPA at baseline to predict the SLOF Interpersonal subdomain at 18 month follow-up. There was a significant moderating effect of symptoms on this relationship such that the relationship was stronger for individuals with primarily positive symptoms compared to individuals with only depressive symptoms, B = 4.59, F(1,124) = 6.67, p = .011. There was no difference in the magnitude of this relationship between individuals with primarily negative symptoms, p = .869, or individuals with undifferentiated symptoms, p = .190, and individuals with only depressive symptoms.

Simple slopes follow-ups (Figure 2) revealed that SSPA score at baseline significantly predicted SLOF Interpersonal functioning at 18 month follow-up for individuals with primarily positive symptoms, B = 4.31, F(1,124) = 13.96, p < .001, 95% CI = 2.03 to 6.59, and for individuals with undifferentiated symptoms, B = 1.81, F(1,124) = 4.78, p = .031, 95% CI = 0.17 to 3.44. This same relationship did not exist for individuals with primarily negative symptoms, B = 0.19, F(1,124) = 0.01 p = .940, 95% CI = -4.77 to 5.14, or only depressive symptoms, B = -0.28, F(1,124) = .043, p = .836, 95% CI = -2.96 to 2.40.

Figure 2.

Prediction of SLOF Interpersonal domain (interpersonal performance) at 18 month follow-up by SSPA (interpersonal competence) at baseline, by symptom group.

The same patterns of results were found even after controlling for diagnosis, age, gender, education, age at first hospitalization, and independent living status.

4. Discussion

Results from this study suggest that specific classes of prominent symptoms moderate the relationship between functional competence at baseline and functional performance at an 18 month follow-up for both adaptive and interpersonal functioning in individuals with schizophrenia. No moderation was observed for the relationship between neurocognition and capacity or performance. A relationship existed between competence and performance for individuals with primarily positive symptoms and undifferentiated symptoms, such that greater competence in an optimized assessment setting was associated with better future real world performance. No significant relationship was found between baseline competence and real world performance 18 months later for individuals with primarily negative or primarily depressive symptoms.

Many individuals with schizophrenia will experience remission of their positive symptoms, but may not function within normal societal expectations. It is well recognized that these individuals with schizophrenia may continue to experience persistent negative symptoms (Pogue-Geile & Harrow, 1985; Buchanan, 2007). Although the importance of these residual negative symptoms in limiting functional recovery is being recognized, and treatments have been developed to target these symptoms, there is little research examining the role of residual depressive symptoms in schizophrenia. Our results suggest that for individuals who are in remission from positive symptoms, depressive symptoms have the potential to impair functional recovery in a similar way as negative symptoms. Furthermore, residual depressive symptoms were found to be independent of residual negative symptoms, indicating that although they are distinct constructs, as measured in the current study, both are equally important to consider as persistent symptoms that require treatment.

This study has several limitations that should be taken into consideration, some of which may limit the generalizability of these findings to other samples. This study features the performance of older patients with a long-term course of illness and may not generalize to performance of younger or more acutely ill individuals. The criteria used to classify individuals into positive and negative symptoms groups were based on the PANSS – a semi-structured interview, whereas the criterion for the presence of depressive symptoms was based on the BDI – a self-report questionnaire. Self-report questionnaires can suffer from validity issues and using a self-report measure of depression may have decreased the validity of the depressive symptom measurement compared to the negative and positive symptom measurements. Our sample size per group was relatively small, potentially leaving us underpowered to detect significant correlations within some groups. However, we used moderation analyses to examine differences in relationships between groups, increasing our power to detect these effects. We also acknowledge that the SLOF does not contain identical items to the UPSA or SSPA, and therefore some of the discrepancy observed may be the result of differences in content, however, it is unlikely that item differences can fully account for the varying relationships found among the symptom classifications. Lastly, although real-world observation may be the ideal way to measure functioning, this method still relies on third-party reports which may not be accurate representations of behaviour across diverse situations (Pyne et al., 2003), might not be available to all persons, and can be confounded if the participant knows they are being observed (Robson, 2002).

As our treatment target for individuals with schizophrenia shifts from remission of positive symptoms towards achieving functional recovery, understanding how residual negative and depressive symptoms impair functioning is increasingly important. Incorporating treatment for residual depressive symptoms into chronic care and early intervention programs may be a mechanism through which we can improve such independent community functioning. Our findings suggest that both residual depressive symptoms and residual negative symptoms impede an individual’s ability to apply the functional skills they possess in the real world more than positive symptoms, and are essential treatment targets in our goal to promote functional recovery.

Acknowledgments

We authors thank Hannah Anderson, Brooke Halpern, and Kushik Jaga for assistance with data collection. We also thank Katherine Holshausen and Michael Grossman for comments on the work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abdallah C, Cohen CI, Sanchez-Almira M, Reyes P, Ramirez P. Community integration and associated factors among older adults with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(12):1642–1648. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.12.1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Author; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, Flaum M, Arndt S. The comprehensive assessment of symptoms and history (CASH): An instrument for assessing psychopathology and diagnosis. Arch Gen Psychiat. 1992;49(8):615–623. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080023004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, Carpenter WT, Kane JM, Lasser RA, Marder SR, Weinberger DR. Remission in schizophrenia: proposed criteria and rationale for consensus. Am J Psychiat. 2005;162(3):441–449. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- an der Heiden W, Könnecke R, Maurer K, Ropeter D. Depression in the long-term course of schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psy Clin N. 2005;255(3):174–184. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0585-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baynes D, Mulholland C, Cooper SJ, Montgomery RC, MacFlynn G, Lynch G, Kelly C, King DJ. Depressive symptoms in stable chronic schizophrenia: prevalence and relationship to psychopathology and treatment. Schizophr Res. 2000;45(1):47–56. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory Manual. second. San Antonio, Texas: Psychological Corp; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8(1):77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bowie CR, Depp C, McGrath JA, Wolyeniec P, Mausbach BT, Thornquist MH, Luke J, Patterson TL, Harvey PD, Pulver AE. Prediction of real world functional disability in chronic mental disorders: a comparison of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiat. 2010;167(9):1116–1124. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie CR, Leung WW, Reichenberg A, McClure MM, Patterson TL, Heaton RK, Harvey PD. Predicting schizophrenia patients’ real world behavior with specific neuropsychological and functional capacity measures. Biol Psychiat. 2008;63(5):505–511. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie CR, Reichenberg A, Patterson T, Heaton RK, Harvey PD. Determinants of real world functional performance in schizophrenia subjects: correlations with cognition, functional capacity, and symptoms. Am J Psychiat. 2006;163(3):418–425. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan RW. Persistent negative symptoms in schizophrenia: An overview. Schizophrenia Bull. 2007;33(4):1013–1022. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental State: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF, Kern RS, Heaton RK. Longitudinal studies of cognition and functional outcome in schizophrenia: implications for MATRICS. Schizophr Res. 2004;72(1):41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta M, Bassett E, Iftene F, Bowie CR. Functional outcomes in schizophrenia: understanding the competence-performance discrepancy. J Psychiat Res. 2012;46(2):205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häfner H, Maurer K, Trendler G, Schmidt M, Könnecke R. Schizophrenia and depression: challenging the paradigm of two separate diseases--a controlled study of schizophrenia, depression and healthy controls. Schizophr Res. 2005;77(1):11–24. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PD. Mood symptoms, cognition, and everyday functioning: in major depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. Innovations in Clin. Neurosci. 2011;8(10):14–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PD, Bellack AS. Toward a terminology for functional recovery in schizophrenia: is functional remission a viable concept? Schizophrenia Bull. 2009;35(2):300–306. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PD, Siever LJ, Huang GD, et al. The genetics of functional disability in schizophrenia and bipolar illness: methods and initial results for VA cooperative study #572. Neuropsych Gen. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32242. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Chellune CJ, Talley JL, Kay GG, Curtlss G. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test Manual-Revised and Expanded. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Herberner ES, Harrow M. Are negative symptoms assocaited with functioning deficits in both schizophrenia and nonschizohrenia patients? A 10-year longitudinal analysis. Schizophrenia Bull. 2004;30(4):813–825. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay SR. Positive and negative syndromes in schizophrenia: Assessment and research. Brunner/Mazel; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Leifker FR, Bowie CR, Harvey PD. Determinants of everyday outcomes in schizophrenia: the influences of cognitive impairment, functional capacity, and symptoms. Schizophr Res. 2009;115(1):82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenmayer JP, Stanley RK, Plutchik R. Multivantaged assessment of depression in schizophrenia. Psychiat Res. 1992;42(3):199–207. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(92)90112-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milev P, Ho BC, Arndt S, Andreasen NC. Predictive values of neurocognition and negative symptoms on functional outcome in schizophrenia: a longitudinal first-episode study with 7-year follow-up. Am J Psychiat. 2005;162(3):495–506. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC, Heyman A, Mohs RC, et al. The consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer’s disease (CERAD). Part I. Clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1989;39:1159–1165. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.9.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oltmanns TF, Neale JM. Schizophrenic performance when distractors are present: Attentional deficit or differential task difficulty? J Abnorm Psychol. 1975;84(3):205–209. doi: 10.1037/h0076721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TL, Goldman S, McKibbin CL, Hughs T, Jeste DV. UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment: development of a new measure of everyday functioning for severely mentally ill adults. Schizophrenia Bull. 2001a;27(2):235–245. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TL, Moscona S, McKibbin CL, Davidson K, Jeste DV. Social skills performance assessment among older patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2001b;48(2):351–360. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogue-Geile M. Negative symptoms and depression in schizophrenia. Depression in Schizophrenics. 1989:121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Pogue-Geile MF, Harrow M. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: their longitudinal course and prognostic importance. Schizophrenia Bull. 1985;11(3):427–439. doi: 10.1093/schbul/11.3.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyne JM, Sullivan G, Kaplan R, Williams DK. Comparing the sensitivity of generic effectiveness measures with symptom improvement in persons with schizophrenia. Medical Care. 2003;41(2):208–217. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000044900.72470.D4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery: Theory and Clinical Interpretation. 2. Neuropsychology Press; Tucson: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, Bilder R, Goldman R, Geisler S, Koreen A, Sheitman B, Chakos M, Mayerhoff D, Lieberman JA. Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiat. 1999;56(3):241–247. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.3.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson DG, Woerner MG, McMeniman M, Mendelowitz A, Bilder RM. Symptomatic and functional recovery from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiat. 2004;161(3):473–479. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson C. Real world research: a resource for social scientists and practitioner-researchers. Blackwell Publishing; Maiden, MA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sabbag S, Twamley EW, Vella L, Heaton RK, Patterson TL, Harvey PD. Predictors of the accuracy of self assessment of everyday functioning in people with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;137(1-3):190–195. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider LC, Struening EL. SLOF: A behavioral rating scale for assessing the mentally ill. Soc Work Res Abstr. 1983;19(3):9–21. doi: 10.1093/swra/19.3.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TE, Hull JW, Huppert JD, Silverstein SM. Recovery from psychosis in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: symptoms and neurocognitive ratelimiters for the development of social behavior skills. Schizophr Res. 2002;55(3):229–237. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00231-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spreen O, Strauss E. A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests and Norms. 2. Oxford University Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanopoulou E, Lafuente AR, Fonseca AS, Keegan S, Vishnick C, Huxley A. Global assessment of psychosocial functioning and predictors of outcome in schizophrenia. Int J Psychiat Clin Prac. 2011;15(1):62–68. doi: 10.3109/13651501.2010.519035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler M. WAIS-III and WMS-III Technical Manual. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- White L, Harvey PD, Opler L, Lindenmayer JP. Empirical assessment of the factorial structure of clinical symptoms in schizophrenia. A multimodel evaluation of the factorial structure of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale. The PANSS Study Group. Psychopathology. 1997;30(5):263–274. doi: 10.1159/000285058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson GS. The Wide Range Achievement Test. Wide Range, Inc; Wilmington, DE: 1993. [Google Scholar]