Abstract

HIV infection is linked to increased prevalence of depression which may affect maternal caregiving practices and place young infants at increased risk of illness. We examined the incidence and days ill with diarrhea among infants of HIV positive (HIV-P), HIV negative (HIV-N), and unknown HIV status (HIV-U) women, and determined if symptoms of maternal postnatal depression (PND) modulated the risk of diarrhea. Pregnant women (n=492) were recruited from 3 antenatal clinics; mothers and infants were followed for 12 mo postpartum. Diarrheal incidence was 0.6 episodes/100-d at risk. More HIV-P than HIV-N and HIV-U women tended to report PND symptoms (P=0.09). PND symptoms increased the risk of infantile diarrhea only for HIV-P and HIV-U but not HIV-N women (interaction term, P=0.02). Health care providers should be aware of the increased risk of infantile diarrhea when both maternal HIV and PND symptoms are present and take preventive action to reduce morbidity.

Keywords: infantile diarrhea, HIV, depression, postpartum

INTRODUCTION

Diarrhea remains a leading cause of child morbidity and contributes to 19% of deaths in children under 5 y of age (1). A plethora of studies have described the epidemiology as well as the risk factors associated with diarrheal morbidity. Improvements in household water supply and treatment as well as in sanitation and hygiene practices have reduced diarrheal morbidity and mortality (2). Recent studies have identified maternal mental health as another important determinant of infant health outcomes. Rahman and colleagues reported that postnatal depression (PND) was associated with an increase in the risk of diarrheal morbidity in Pakistani infants (3).

The HIV/AIDS pandemic has added to the concern for young child survival as HIV infection may compromise a household’s ability to adequately care for a young child. HIV infection also has been reported to be associated with an increased risk for adult major depressive disorders (4) which may be a contributing factor to the observed increase in infant morbidity and mortality from infectious diseases (5, 6). The co-existence of HIV infection and maternal depression may synergistically influence infant morbidity outcomes including diarrhea. This study examined the incidence and number of days ill with diarrhea among Ghanaian infants living in communities affected with HIV and examined the interaction between maternal HIV status and symptoms of PND on infant risk of having diarrhea. We hypothesized that:

maternal HIV infection would be positively associated with infant diarrheal morbidity

symptoms of PND among mothers would be positively associated with infant diarrheal morbidity, and

there would be a synergistic effect of maternal HIV infection and symptoms of PND such that infants of women who were affected by both conditions would have an excessive risk of diarrhea.

METHODS

Study site

This study [Research to Improve Infant Nutrition and Growth (RIING) project (2004–2008)] was conducted in the Manya and Yilo Krobo districts, Eastern region, Ghana. This region has consistently recorded the highest HIV prevalence; the 2007 prevalence (4.2%) was more than twice the national rate of 1.9%. The Manya Krobo district was the first in the country to benefit from services and support for voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) for HIV in 2001.

Recruitment and follow-up

Recruitment of pregnant women occurred at prenatal clinics in three hospitals. Pregnant women were recruited and enrolled after VCT. In 2003, under the national VCT program, all pregnant women received counselling on the risk of HIV transmission and were informed about the available services, after which they were invited to be tested for HIV (‘opt-in’ system). In 2005, the national program was changed to an ‘opt-out’ system in which all women were tested after counselling unless they requested not to be.

Women were considered eligible for the study if they 1) were at least 18 years old, 2) were pregnant at the time of enrolment, 3) had completed pre- and post-VCT, or only pre-VCT if they had refused testing, and 4) agreed to have their HIV test results released to the project coordinator (for those who completed VCT). The rapid test ‘Abbott Determine HIV-1/2’ (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA) was used at the hospital to test for HIV. Samples from indeterminate results were sent to the Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research for confirmation with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis. The participants were classified as HIV positive (HIV-P, tested positive for HIV), HIV negative (HIV-N, tested negative for HIV) or unknown HIV status (HIV-U, refused to be tested for HIV). A participant was considered eligible for the postpartum longitudinal surveillance if 1) she gave birth to a live infant, 2) her infant was free of any birth defect that may otherwise hinder feeding, and 3) she was free of any physical condition that may limit her ability to care for her infant. Only the field supervisor had access to women’s HIV status.

Mother-infant pairs were followed from birth up to 12 months. Twice a week, mothers were visited to collect information on infant health, including total number of stools and stool characteristics (e.g., liquid). For each symptom, the mother was asked to recall the events for the day of visit and for each preceding day since she was last visited by the field worker for up to a maximum of seven days of recall. Infant feeding information was collected with the same methodology. The mother was asked if she breastfed the baby and if the baby received any non-breast milk liquids (water, infant formula, other non-human milk) or semi-solid or solid food.

Symptoms of maternal PND were measured shortly after birth (median 5 days, range 0–50 days) using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), a10-item scale that asks for symptoms that occurred over the past 7 days (7). There was no significant difference between the three HIV groups with regards to the time when the scale was administered (P=0.32). Each item on the EPDS was scored on a 4-point rating scale that represented the level of occurrence. The Cronbach’s alpha for the EPDS was 0.82.

Maternal stress was measured at enrolment (prenatal) using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), a 4-item scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87) used to measure the degree to which situations in a person’s life are perceived as stressful (8). Each item on the PSS measures the frequency of occurrence. Total scores range from 4 (low stress) to 20 (high stress).

Infant weight was measured at birth, then monthly. Maternal weight was measured monthly and height was measured once at six months postpartum. Duplicate weight measurements were made using the Tanita digital weighing scale (Tanita Corporation of America Inc., Arlington Heights, IL, USA) and measured to the nearest 0.1 kg. Maternal height was measured in duplicate to the nearest 0.1 cm using a wooden stadiometer (Shorr Productions; Maryland, USA).

Variables

Outcome measures included the incidence, number of days ill, and risk of having diarrhea on any day during the first 12 months of life. Diarrhea was defined as passing three or more liquid or semi-liquid stools in a 24-hour period (9). An episode was separated from another by at least two symptom-free days (10). Incidence rate was calculated as the number of new episodes divided by the number of days at risk [days at risk = (days observed) − (# days ill) + (# episodes)] (11). Diarrheal incidence and days ill were standardised to 100-days of observation.

An infant was considered to be exclusively breastfed (EBF) if since birth the infant received only breast milk. EBF ceased on the day that the infant received any non-breast milk liquids or semi-solids.

A binary variable was used for maternal PND. Mothers with total EPDS scores below 13 were classified as not showing symptoms of PND whereas those with total EPDS scores 13 and above were classified as showing symptoms of PND (7, 12). Maternal perceived stress score was maintained as a continuous variable.

Statistical analysis

Morbidity was examined for four age intervals: 0–3, 3–6, 6–9 and 9–12 months. The descriptive data are presented as means and standard errors or frequencies and percentages. Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test were used for categorical variables and Analysis of Variance for normally distributed continuous variables. The non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used for non-normally distributed continuous data. Multiple logistic regression analysis was conducted using the SAS PROC GENMOD procedure. The models were fitted with the assumption that the data were generated from a binomial distribution. Overdispersion, a condition that occurs when the variance is larger than expected under a given model, was checked and adjusted for (using the D-scale syntax) whenever it occurred. An HIV-PND interaction term was included in the model to test for the interaction between HIV status and PND. The initial model included maternal (age, parity, height, education, ethnicity, marital status, prenatal stress score) infant (sex, EBF status, low birth weight) and household (primary water source, cooking fuel, toilet facility) factors. The method of backward elimination was used to remove non-significant variables one at a time until a final model consisted of variables with a p-value of ≤0.1. All data were analysed using SAS version 9.13 for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and significant results were reported at alpha < 0.05 unless otherwise indicated.

Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review boards of McGill University, University of Ghana, Iowa State University, and University of Connecticut. Signed informed consent was obtained from each participant.

RESULTS

Study sample

Six hundred and ninety-two pregnant women were informed about the study, out of which 552 women were enrolled. Out of 505 recorded live births, morbidity data were available for 492 infants.

Baseline characteristics

Maternal age ranged from 18 to 48 years with a mean of 28.5 ± 0.3 y. Study subjects had 0–8 prior live births, with a median of 1. The majority of women (69%, n=339) were of the Ga-Adangme ethnic group. More than two-thirds of the women were not married and were either living with a partner (n=245) or had no partner (n=95). Most women (n=440) had some form of formal education although one-third (n=162) had not reached secondary school. The public tap served as the main water source for the majority of households (67%, n=328). Fewer than one-fifth (16%) of the women had flush toilets. Over 70% of the households used charcoal or wood as their main cooking fuel. On the whole, HIV-P women were poorer than other women, as indicated by less secondary or higher education, lower likelihood to be married and less access to flush toilet, in-house tap and gas or electric stove (TABLE I).

Table 1.

Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of Ghanaian study population at baseline, by maternal HIV status

| HIV-P N=152 |

HIV-N N=176 |

HIV-U N=164 |

χ2 | P-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (y) | 28.3 ± 0.5 | 29.0 ± 0.4 | 28.1 ± 0.4 | 2.3689 | 0.3059 |

| Parity (#) | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 2.3085 | 0.3153 |

| Maternal education | 21.93 | 0.0002 | |||

| None | 25 (16.4) | 13 (7.4) | 14 (8.5) | ||

| Primary | 47 (30.9) | 30 (17.0) | 33 (20.1) | ||

| Secondary and higher | 80 (52.6) | 133 (75.6) | 117 (71.3) | ||

| Ethnicityb | 20.86 | <0.0001 | |||

| Non-local | 26 (17.1) | 62 (35.2) | 65 (39.6) | ||

| Local | 126 (8.29) | 114 (64.8) | 99 (60.4) | ||

| Marital status | 29.87 | <0.0001 | |||

| Not married | 128 (84.2) | 99 (56.2) | 113 (68.9) | ||

| Married | 24 (15.8) | 77 (43.7) | 51 (31.1) | ||

| Cooking fuel | 4.62 | 0.09 | |||

| Wood | 22 (14.6) | 14 (7.9) | 14 (8.5) | ||

| Otherc | 129 (85.4) | 162 (92.0) | 150 (91.4) | ||

| Main water source | 13.82 | 0.0010 | |||

| No tap in home | 126 (83.4) | 124 (70.4) | 107 (65.2) | ||

| Tap in home | 25 (16.6) | 52 (29.5) | 57 (34.7) | ||

| Toilet facilityd | 14.41 | 0.0061 | |||

| KVIP | 86 (56.9) | 80 (45.4) | 95 (57.9) | ||

| Other | 52 (34.4) | 62 (35.2) | 39 (23.8) | ||

| Flush toilet | 13 (8.6) | 34 (19.3) | 30 (18.3) |

Results are presented as mean ± standard error or N (%)

HIV-P, HIV positive; HIV-N, HIV negative; HIV-U, unknown HIV status

Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous data; chi-square test for categorical data

Non-local=Ewe, Akan, northerner, any other ethnicity; Local= Ga-Adangme

Other=charcoal, gas cooker, electric stove

KVIP=Kumasi Ventilated Improved Pit latrine; Other=bucket, latrine, pit latrine, bush

Diarrheal episodes and diarrheal days ill

The total number of days ill with diarrhea was 2.2 per 100-days observed (8.0 days ill/ year). There was an average of 0.6 new episodes of diarrhea per 100-days at risk (2.3 episodes/ year). Over the 12 months, although the diarrheal incidence was similar among the three groups of infants and infants of HIV-P mothers tended to have a lower number of days ill (TABLE II).

Table 2.

Infant diarrheal days ill (per 100 days of observation) and incidence of diarrhea (episodes per 100 days at risk), by maternal HIV status

| HIV-P | HIV-N | HIV-U | χ2 | P-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days ill (d/100 d observed) | |||||

| 0–3 mo | 1.6 ± 0.4 [151] | 2.3 ± 0.6 [175] | 2.7 ± 0.5 [163] | 5.13 | 0.0767 |

| 3–6 mo | 2.2 ± 0.4 [135] | 3.9 ± 0.6 [167] | 4.1 ± 0.6 [160] | 5.48 | 0.0646 |

| 6–9 mo | 2.4 ± 0.4 [123] | 3.0 ± 0.4 [164] | 3.1 ± 0.4 [152] | 2.52 | 0.2837 |

| 9–12 mo | 1.8 ± 0.3 [107] | 2.9 ± 0.4 [161] | 2.9 ± 0.4 [146] | 5.71 | 0.0576 |

| 0–12 mo | 1.6 ± 0.2 [152] | 2.3 ± 0.3 [176] | 2.6 ± 0.3 [164] | 5.77 | 0.0557 |

| Incidence (episodes/100 d at risk) | |||||

| 0–3 mo | 0.6 ± 0.1 [151] | 0.5 ± 0.1 [175] | 0.8 ± 0.1 [163] | 4.37 | 0.1123 |

| 3–6 mo | 0.7 ± 0.1 [135] | 1.1 ± 0.1 [167] | 1.1 ± 0.2 [160] | 4.29 | 0.1172 |

| 6–9 mo | 1.0 ± 0.2 [123] | 1.1 ± 0.1 [164] | 0.9 ± 0.1 [152] | 1.65 | 0.4370 |

| 9–12 mo | 0.8 ± 0.1 [107] | 1.1 ± 0.1 [161] | 1.1 ± 0.1 [146] | 5.47 | 0.0649 |

| 0–12 mo | 0.6 ± 0.1 [152] | 0.6 ± 0.1 [176] | 0.7 ± 0.1 [164] | 3.25 | 0.1968 |

Results represented as mean ± standard error [N]

HIV-P, HIV positive; HIV-N, HIV negative; HIV-U, unknown HIV status

Kruskal-Wallis tests

Maternal postnatal depression

About 10% of women reported symptoms of PND at birth. HIV-P women tended to be more likely to report symptoms at birth than HIV-N and HIV-U women (14% vs. 7% and 10%, respectively; P=0.09). The analysis of diarrheal morbidity by maternal PND status showed that having symptoms of PND was associated with more episodes and days ill with diarrhea (TABLE III). In the first three months of life, infants of mothers reporting PND symptoms had almost twice the number of diarrheal episodes (P=0.002) and about 50% more days ill with diarrhea (P<0.001) than infants whose mothers reported no PND symptoms.

Table 3.

Infant diarrheal days ill (per 100 days of observation) and incidence (episodes per 100 days at risk), by symptoms of maternal postnatal depression reported by mothers shortly after birth

| Symptoms of PNDa | No symptom of PND | χ2 | P-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days ill (d/100 d observed) | ||||

| 0–3 mo | 4.4 ± 1.0 [49] | 2.0 ± 0.3 [419] | 13.81 | 0.0002 |

| 3–6 mo | 3.3 ± 0.8 [46] | 3.4 ± 0.3 [400] | 1.94 | 0.1636 |

| 6–9 mo | 3.3 ± 0.9 [43] | 2.7 ± 0.2 [381] | 0.75 | 0.3842 |

| 9–12 mo | 2.7 ± 0.5 [38] | 2.6 ± 0.2 [362] | 1.13 | 0.2868 |

| 0–12 mo | 2.8 ± 0.5 [49] | 2.1 ± 0.2 [419] | 2.70 | 0.1000 |

|

| ||||

| Incidence (episodes/100 d at risk) | ||||

| 0–3 mo | 1.1 ± 0.2 [49] | 0.6 ± 0.1 [419] | 12.24 | 0.0005 |

| 3–6 mo | 1.2 ± 0.2 [46] | 1.0 ± 0.1 [400] | 3.53 | 0.0603 |

| 6–9 mo | 1.1 ± 0.2 [43] | 1.0 ± 0.1 [381] | 0.89 | 0.3440 |

| 9–12 mo | 1.1 ± 0.2 [38] | 1.0 ± 0.1 [362] | 1.62 | 0.2024 |

| 0–12 mo | 0.8 ± 0.1 [49] | 0.6 ± 0.1 [419] | 4.18 | 0.0409 |

Results represented as mean ± standard error [N]

PND, Postnatal depression; symptoms of PND were measured shortly after birth. Participants were classified as showing symptoms of PND if they scored 13 or more on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) [10]. Participants with EPDS scores <13 were classified as not showing symptoms of PND.

Kruskal-Wallis tests

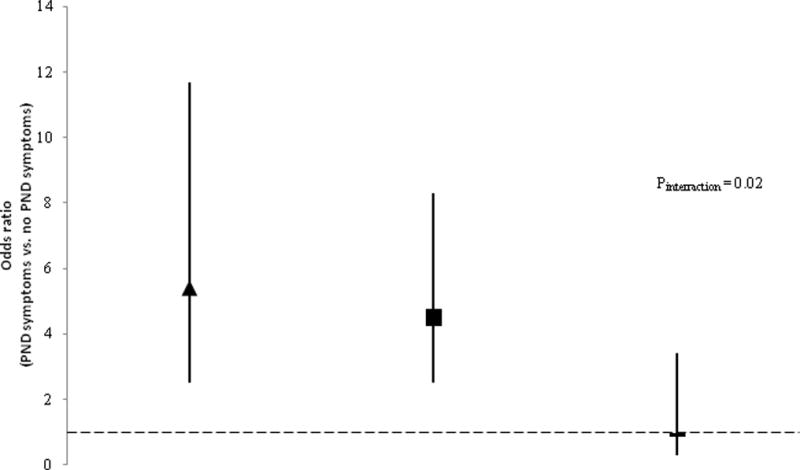

Maternal HIV status-PND interaction

To examine the synergistic effect of maternal HIV infection and symptoms of PND on risk of diarrhea, the analysis focused on the first three months postpartum when a strong association between maternal PND and risk of infant diarrhea was noted. Logistic regression results showed a significant interaction between maternal HIV status and PND on infant risk of having diarrhea in the first three months of life (TABLE IV). The association between maternal HIV status and infant diarrhea differed according to maternal depression status. Whereas there was no difference in infant risk of diarrhea by reported PND symptoms among HIV-N women (OR = 0.9, 95% CI 0.3, 3.3), infants of HIV-P women had a 6-fold increased risk of having diarrhea if their mother reported PND symptoms (OR = 6.5, 95% CI 2.9, 14.5). Similarly, PND symptoms were associated with a 3-fold increase in likelihood of reporting infant diarrhea among HIV-U women (OR = 3.5, 95% CI 1.8, 6.7). Being not married, as well as being of an ethnic group not native to the community, possible indicators of social and economic stress, remained significantly associated with increased illness (TABLE IV). Low birth weight did not remain significant in the adjusted model.

Table 4.

Unadjusted odds ratios for explanatory variables of infant risk of having diarrhea in the first 3 months of life

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | χ2 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parity (#) | 1.13 (1.01–1.25) | 5.06 | 0.0245 |

| Maternal age (y) | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | 0.24 | 0.6211 |

| Maternal height (cm) | 0.98 (0.95–1.02) | 1.07 | 0.3004 |

| Maternal HIV status | |||

| Positive | 0.68 (0.43–1.09) | 2.55 | 0.1102 |

| Unknown | 1.17 (0.79–1.73) | 0.65 | 0.4185 |

| Negative | Reference | ||

| Postnatal depression symptomsa | |||

| Yes | 2.36 (1.53–3.67) | 14.84 | 0.0001 |

| No | Reference | ||

| Perceived prenatal stress scoreb | 0.97 (0.92–1.02) | 1.47 | 0.2250 |

| Marital status | |||

| Not married | 2.35 (1.48–3.72) | 13.36 | 0.0003 |

| Married | Reference | ||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Non-localc | 1.20 (0.84–1.73) | 1.02 | 0.3125 |

| Local | Reference | ||

| Low birth weight | |||

| Yes | 0.20 (0.05–0.76) | 5.63 | 0.0177 |

| No | Reference | ||

| Exclusive breastfeeding to 3 mo | |||

| No | 0.96 (0.65–1.42) | 0.03 | 0.8636 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Cooking fuel | |||

| Wood | 1.64 (1.02–2.65) | 4.21 | 0.0402 |

| Otherd | Reference | ||

| Main water source | |||

| No tap in home | 1.35 (0.89–2.05) | 2.08 | 0.1493 |

| Tap in home | Reference | ||

| Toilete | |||

| KVIP | 1.27 (0.77–2.12) | 0.92 | 0.3383 |

| Other | 0.90 (0.51–1.59) | 0.12 | 0.7268 |

| Flush toilet | Reference |

Participants were classified as showing symptoms of postnatal depression (PND) if they scored 13 or more on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) [10]. Participants with EPDS scores <13 were classified as not showing symptoms of PND.

Perceived prenatal stress used the 4-item Perceived Stress Scale [11]; total scores ranged from 4 (low stress) to 20 (high stress).

Non-local=Ewe, Akan, northerner, any other ethnicity; Local= Ga-Adangme

Charcoal, gas cooker, electric stove

KVIP=Kumasi Ventilated Improved Pit latrine; Other=bucket latrine, pit latrine, bush

OR, Odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; HIV-P, HIV positive; HIV-N, HIV negative; HIV-U, unknown HIV status

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to show a synergistic relationship between maternal HIV status and postnatal depression on infant risk of having diarrhea. HIV-P mothers with PND symptoms may have spent less time on child care, compromising infant health. Alternatively, HIV-P women with PND symptoms may have been clinically sicker and unable to adequately care for their infants. Antelman and colleagues reported an increase in risk of disease progression (HR=1.61, 95% CI: 1.28 to 2.03) and all-cause mortality (HR=2.65; 95% CI: 1.89 to 3.71) among Tanzanian HIV-infected women who were depressed (13). The only other study that has examined the relationship between maternal depression and infant diarrhea was conducted in a non-HIV population in Pakistan. The researchers reported a three-fold (OR=3.1; 95% CI: 1.8 to 5.6) increase in risk of frequent diarrheal illness (defined as ≥ 5 diarrheal episodes/year) among infants of women who were depressed (3). In both the Pakistani and our study, low birth weight did not remain a significant predictor of diarrheal illness once other socioeconomic factors were included. However, wasting (<−2 weight-for-length) at 6 months in the Pakistani was associated with increased risk. We chose to not include a similar mid-point anthropometric predictor in our model for various reasons. First, only predictors that occurred prior to the outcome of interest were included to clarify temporal relationships. Second, differences in anthropometric measurements were pronounced from birth and retained thereafter (data not shown). Finally, birth weight is highly correlated with weight during the first year of life and therefore an additional weight indicator may be redundant.

The estimate of diarrheal incidence (2.3 episodes/year) is similar to that reported in a WHO global review (2.6 episodes/year) (14) and a study in Turkey (2.8 episodes/year) (15). However, between 7.7 and 18.6 episodes were reported in South Africa, Kenya and Zimbabwe (16). The comparatively lower rates recorded in Ghana could be due to high exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) rates (> 70% at 5 months; data not shown); only nine infants of HIV-P mothers (2.7%) did not breastfeed. Exclusive breastfeeding is protective against diarrhea (17, 18). This high EBF rate across HIV groups, which is consistent with another Ghanaian study (19), may partly explain why we found no group differences in diarrhea. However, different factors in other settings should be considered. In Botswana, diarrheal morbidity at 6 months was similar between infants of HIV-P and HIV-N women, despite low EBF rates (17.5% and 9.5% EBF at 5 months among HIV-P and HIV-N, respectively) (20).

Twice weekly data collection reduced errors from poor maternal recall and allowed for confirmation of health status by the field staff when the illness coincided with the visit. Field workers were masked to HIV status, thereby reduced differential bias. Despite these methodological strengths, this study had limitations. Firstly, maternal HIV status was tested only at enrollment. Some mothers may have become infected during the study; new infections would have diminished our ability to observe group differences. Secondly, our analysis did not include the infant’s HIV status. At the time of the study, the health ministry protocol included testing of infants only at 18 mo of age or with presentation of symptoms. Although the project offered free testing for all infants, few mothers agreed to have their child tested. Infant HIV infection is associated with increased morbidity; however, given the decreased risk of HIV transmission with EBF compared to mixed feeding, the majority of infants may have remained uninfected.

In summary, infants of HIV-P and HIV-U mothers who showed symptoms of PND had an increased risk of having diarrhea in the first 3 months of life. Health care programs in HIV-affected communities should train their personnel to address the challenges that poor maternal mental and physical health may bring to infant health; programs are need to work towards prevention and intervention programs to decrease infant morbidity and mortality.

Fig. 1.

Infants’ risk of having diarrhea on any day, 0 – 3 months of age, associated with symptoms of postnatal depression (PND), by maternal HIV status. Symbols indicate adjusted Odds Ratios (aOR; adjusted for perceived prenatal stress, marital status, low birth weight, and cooking fuel); vertical lines indicate 95% CI. The comparisons shown use absence of PND symptoms as the reference group within each HIV category: HIV-P (aOR = 5.39, 95% CI: 2.48–11.68); HIVU (aOR = 4.53, 95% CI: 2.47–8.32); HIV-N (aOR = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.28–3.43). Dotted line represents OR = 1. HIV-P, HIV positive; HIV-N, HIV negative; HIV-U, unknown HIV status

Table 5.

Factors associated with infant risk of having diarrhea in the first 3 mo after birth

| aORa (95% CI) |

χ2 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal HIV status | |||

| Unknown | 1.62 (0.81–3.24) | 1.90 | 0.1685 |

| Positive | 0.86 (0.41–1.81) | 0.15 | 0.6980 |

| Negative | Reference | ||

| Postnatal depression symptomsb | |||

| Yes | 2.89 (1.71–4.89) | 15.84 | 0.0001 |

| No | Reference | ||

| HIV status*PND symptoms interactionc | 7.84 | 0.02 | |

| HIV-P and PND symptoms | 2.00 (1.01–3.94) | 4.01 | 0.0451 |

| HIV-P and no PND symptoms | 0.37 (0.20–0.67) | 10.43 | 0.0012 |

| HIV-U and PND symptoms | 3.45 (1.90–6.27) | 16.58 | 0.0001 |

| HIV-U and no PND symptoms | 0.76 (0.47–1.21) | 1.30 | 0.2537 |

| HIV-N and PND symptoms | 0.99 (0.28–3.43) | 0.00 | 0.9942 |

| HIV-N and no PND symptoms | Reference | ||

| Perceived prenatal stressd | 0.92 (0.87–0.97) | 7.75 | 0.0054 |

| Marital status | |||

| Not married | 4.03 (2.39–6.78) | 27.42 | 0.0001 |

| Married | Reference | ||

| Low birth weight | |||

| Yes | 0.25 (0.07–0.81) | 5.30 | 0.0213 |

| No | Reference | ||

| Cooking fuel | |||

| Wood | 2.03 (1.27–3.25) | 8.79 | 0.0030 |

| Othere | Reference |

The multiple logistic regression model adjusted for all the variables shown in the table including the interaction term; adjusted odds ratios are shown.

Participants were classified as showing symptoms of postnatal depression (PND) if they scored 13 or more on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) [10]. Participants with EPDS scores <13 were classified as not showing symptoms of PND.

HIV status-postnatal depression interaction was significant (P=0.02).

Perceived prenatal stress used the 4-item Perceived Stress Scale [11]. Total scores ranged from 4 (low stress) to 20 (high stress).

Other=charcoal, gas cooker, electric stove

aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; HIV-P, HIV positive; HIV-N, HIV negative; HIV-U, unknown HIV status; PND, Postnatal depression

Acknowledgments

Rula Souieda and Dr. Roger Cue at McGill University provided assistance with data management and statistical analysis, respectively. This publication was funded by grant number HD 43260, National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD)/National Institutes of Health. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NICHD.

References

- 1.Boschi-Pinto C, Velebit L, Shibuya K. Estimating child mortality due to diarrhoea in developing countries. Bull WHO. 2008;86(9):710–17. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.050054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cairncross S, Hunt C, Boisson S, et al. Water, sanitation and hygiene for the prevention of diarrhoea. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(Suppl 1):193–205. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahman A, Bunn J, Lovel H, Creed F. Maternal depression increases infant risk of diarrhoeal illness: A cohort study. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92(1):24–8. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.086579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ciesla JA, Roberts JE. Meta-analysis of the relationship between HIV infection and risk for depressive disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(5):725–30. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thea DM, St Louis ME, Atido U. A prospective study of diarrhea and HIV-1 infection among 429 Zairian infants. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(23):1696–702. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312023292304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brahmbhatt HP, Kigozi GMD, Wabwire-Mangen FP, et al. Mortality in HIV-infected and uninfected children of HIV-infected and uninfected mothers in rural Uganda. JAIDS. 2006;41(4):504–8. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000188122.15493.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10 item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150(6):782–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baqui AH, Black RE, Yunus MD, Hoque ARA, Chowdhury HR, SACK RB. Methodological issues in diarrhoeal diseases epidemiology: definition of diarrhoeal episodes. Int J Epidemiol. 1991;20(4):1057–63. doi: 10.1093/ije/20.4.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris SS, Cousens SN, Lanata CF, Kirkwood BR. Diarrhoea – Defining the episode. Int J Epidemiol. 1994;23(3):617–23. doi: 10.1093/ije/23.3.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bashour HN, Webber RH, Marshall T. A community-based study of acute respiratory infections among preschool children in Syria. J Trop Pediatr. 1994;40(4):207–13. doi: 10.1093/tropej/40.4.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris B, Huckle P, Thomas R, Johns S, Fung H. The use of rating scales to identify post-natal depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154(6):813–17. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.6.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antelman G, Kaaya S, Wei RL, et al. Depressive symptoms increase risk of HIV disease progression and mortality among women in Tanzania. JAIDS. 2007;44(4):470–7. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802f1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bern C, Martines J, de Zoysa I, Glass RI. The magnitude of the global problem of diarrheal disease : a ten year update. Bull WHO. 1992;70(6):705–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Etiler N, Velipasaoglu S, Aktekin M. Risk factors for overall and persistent diarrhoea in infancy in Antalya, Turkey: a cohort study. Public Health. 2004;118(1):62–9. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3506(03)00132-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wright JA, Gundry SW, Conroy R, et al. Defining Episodes of Diarrhea: Results from a Three-country Study in Sub-Saharan Africa. JHPN. 2006;24(1):8–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howie PW, Forsyth JS, Ogston SA, Clark A, Florey CD. Protective effect of breast feeding against infection. BMJ. 1990;300(6716):11–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6716.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhandari N, Bahl R, Mazumdar S, et al. Effect of community-based promotion of exclusive breastfeeding on diarrhoeal illness and growth: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361(9367):1418–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13134-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aidam BA, Pérez-Escamilla R, Lartey A. Lactation counseling increases exclusive breast-feeding rates in Ghana. J Nutr. 2005;135(7):1691–5. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.7.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shapiro RL, Lockmann S, Kim S, et al. Infant morbidity, mortality, and breast milk immunologic profiles among breast-feeding HIV-infected and HIV-Uninfected women in Botswana. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(4):562–9. doi: 10.1086/519847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]