Abstract

Background

Episiotomy is done to prevent severe perineal tears, but its routine use has been questioned. The relative effects of midline compared with midlateral episiotomy are unclear.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to assess the effects of restrictive use of episiotomy compared with routine episiotomy during vaginal birth.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register (March 2008).

Selection criteria

Randomized trials comparing restrictive use of episiotomy with routine use of episiotomy; restrictive use of mediolateral episiotomy versus routine mediolateral episiotomy; restrictive use of midline episiotomy versus routine midline episiotomy; and use of midline episiotomy versus mediolateral episiotomy.

Data collection and analysis

The two review authors independently assessed trial quality and extracted the data.

Main results

We included eight studies (5541 women). In the routine episiotomy group, 75.15% (2035/2708) of women had episiotomies, while the rate in the restrictive episiotomy group was 28.40% (776/2733). Compared with routine use, restrictive episiotomy resulted in less severe perineal trauma (relative risk (RR) 0.67, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.49 to 0.91), less suturing (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.81) and fewer healing complications (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.85). Restrictive episiotomy was associated with more anterior perineal trauma (RR 1.84, 95% CI 1.61 to 2.10). There was no difference in severe vaginal/perineal trauma (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.18); dyspareunia (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.16); urinary incontinence (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.20) or several pain measures. Results for restrictive versus routine mediolateral versus midline episiotomy were similar to the overall comparison.

Authors’ conclusions

Restrictive episiotomy policies appear to have a number of benefits compared to policies based on routine episiotomy. There is less posterior perineal trauma, less suturing and fewer complications, no difference for most pain measures and severe vaginal or perineal trauma, but there was an increased risk of anterior perineal trauma with restrictive episiotomy.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): *Episiotomy [adverse effects; methods; standards], *Parturition, Perineum [*injuries; surgery], Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

MeSH check words: Female, Humans, Pregnancy

BACK GROUND

Description of the condition

Vaginal tears during childbirth are common and may occur spontaneously during birth, or the midwife or obstetrician may need to make a surgical incision (episiotomy) to increase the diameter of the vaginal outlet to facilitate the baby’s birth (Kettle 2007). Anterior perineal trauma is injury to the labia, anterior vagina, urethra, or clitoris, and is usually associated with little morbidity. Posterior perineal trauma is any injury to the posterior vaginal wall, perineal muscles, or anal sphincter (Fernando 2007).

Spontaneous tears are defined as:

first degree (involving the fourchette, perineal skin and vaginal mucous membrane, but not the underlying fascia and muscle);

second degree (involving the perineal muscles and skin);

third degree (injury to the anal sphincter complex: 3a = < 50% of the external anal sphincter torn 3b = 50% of the external anal sphincter torn 3c = injury to the external and internal anal sphincter); and

fourth degree (injury to the perineum involving the anal sphincter complex and anal epithelium) (Fernando 2006).

The most common injuries to the vagina during labour occur at the vaginal opening, which may tear as the baby’s head passes through. For successful vaginal delivery, the vaginal opening must dilate slowly, in order to allow the appropriate stretching of the tissues. When the baby descends quickly, the tissues can tear.

Description of the intervention

Episiotomy is the surgical enlargement of the vaginal orifice by an incision of the perineum during the last part of the second stage of labour or delivery. This procedure is done with scissors or scalpel and requires repair by suturing (Thacker 1983).

A report dating back to 1741 suggested the first surgical opening of the perineum to prevent severe perineal tears (Ould 1741). Worldwide, rates of episiotomy increased substantially during the first half of this century. At that time there was also an increasing move for women to give birth in hospital and for physicians to become involved in the normal uncomplicated birth process. Although episiotomy has become one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures in the world, it was introduced without strong scientific evidence of its effectiveness (Lede 1996). Reported rates of episiotomies vary from as low as 9.70% (Sweden) to as high as 100% (Taiwan) (Graham 2005). Rates of episiotomies around the world are 62.50% in USA (Thacker 1983), 30% in Europe (Buekens 1985; Mascarenhas 1992) and with higher estimates in Latin America. In Argentina, episiotomy is a routine intervention in nearly all nulliparous and primiparous births (Lede 1991).

How the intervention might work

The suggested maternal beneficial effects of episiotomy are the following: (a) reduction in the likelihood of third degree tears (Cunningham 1993; Ould 1741; Thacker 1983), (b) preservation of the muscle relaxation of the pelvic floor and perineum leading to improved sexual function, and a reduced risk of faecal and or urinary incontinence (Aldridge 1935; Gainey 1955), (c) being a straight, clean incision, an episiotomy is easier to repair and heals better than a laceration. For the neonate, it is suggested that a prolonged second stage of labour (a second stage of labour longer than 120 minutes (Hamilton 1861)), could cause fetal asphyxia, cranial trauma, cerebral haemorrhage and mental retardation. During delivery it is also suggested that episiotomy may be necessary to make more room if rotation manoeuvres are required during a fetal shoulder dystocia.

On the other hand, hypothesized adverse effects of routine use of episiotomy include: (a) extension of episiotomy either by cutting the anal sphincter or rectum, or by unavoidable extension of the incision, (b) unsatisfactory anatomic results such as skin tags, asymmetry or excessive narrowing of the introitus, vaginal prolapse, recto-vaginal fistula and fistula in ano (Homsi 1994), (c) increased blood loss and haematoma, (d) pain and oedema in the episiotomy region, (e) infection and dehiscence (Homsi 1994), (f) sexual dysfunction.

Other important issues to bear in mind are costs and the additional resources that may be required to sustain a policy of routine use of episiotomy.

Why it is important to do this review

This review aims to evaluate the available evidence about the possible benefits, risks and costs of the restrictive use of episiotomy versus routine episiotomy. We also evaluate the benefits and risks of performing a midline episiotomy compared with a mediolateral episiotomy.The question of whether midline episiotomy results in a better outcome than mediolateral episiotomy has not been satisfactorily answered. The suggested advantages of performing a midline episiotomy instead of midlateral episiotomy are: better future sexual function and better healing with improved appearance of the scar. Those not in favour of using the midline method suggest it is associated with higher rates of extension of the episiotomy and consequently an increased risk of severe perineal trauma (Shiono 1990).

We also consider the implications for clinical practice and the need for further research in this area.

OBJECTIVES

To determine the possible benefits and risks of the use of restrictive episiotomy versus routine episiotomy during delivery. We will also determine the beneficial and detrimental effects of the using midline episiotomy compared with mediolateral episiotomy.

Comparisons will be made in the following categories.

Restrictive episiotomy versus routine episiotomy (all).

Restrictive episiotomy versus routine episiotomy (mediolateral).

Restrictive episiotomy versus routine episiotomy (midline).

Midline episiotomy versus mediolateral episiotomy.

Hypotheses

Restrictive use of episiotomy compared with routine use of episiotomy during delivery will not influence any of the outcomes cited under ‘Types of outcome measures’.

Restrictive use of midline episiotomy compared with routine use of midline episiotomy during delivery will not influence any of the outcomes cited under ‘Types of outcome measures’.

Restrictive use of medio-lateral episiotomy compared with routine use of medio-lateral episiotomy during delivery will not influence any of the outcomes cited under ‘Types of outcome measures’.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Any adequate randomized controlled trial that compares one or more of the following:

restrictive use of mediolateral episiotomy versus routine use of mediolateral episiotomy;

restrictive use of midline episiotomy versus routine use of midline episiotomy;

use of midline episiotomy versus mediolateral episiotomy. We did not include quasi-randomized controlled trials.

Types of participants

Pregnant women having a vaginal birth.

Types of interventions

Primary comparison

The main comparison is restrictive use of episiotomy versus routine use of episiotomy.

Secondary comparisons

These include:

restrictive use of mediolateral episiotomy versus routine use of mediolateral episiotomy;

restrictive use of midline episiotomy versus routine use of midline episiotomy;

use of midline episiotomy versus mediolateral episiotomy.

Types of outcome measures

Maternal and neonatal outcomes are evaluated.

Primary outcomes

The primary maternal outcomes assessed in the comparison include: severe perineal trauma and severe vaginal/perineal trauma.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary maternal outcomes assessed in the comparison include: number of episiotomies, assisted delivery rate, severe vaginal/perineal trauma, severe perineal trauma, need for suturing, posterior perineal trauma, anterior perineal trauma, blood loss, perineal pain, use of analgesia, dyspareunia, haematoma, healing complications and dehiscence, perineal infection, and urinary incontinence.

The neonatal outcome measures are Apgar score less than seven at one minute and need for admission to special care baby unit.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co-ordinator (March 2008).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co-ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co-ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Trials under consideration were evaluated for methodological quality and appropriateness for inclusion, without consideration of their results. Included trial data were processed as described in Higgins 2006.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies that were identified as a result of the search strategy. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data and two review authors extracted data using the agreed form. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Data were entered into Review Manager software (RevMan 2008) and checked for accuracy.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed methodological quality in the three dimensions initially described by Chalmers 1989: namely the control for selection bias at entry (the quality of random allocation, assessing the generation and concealment methods applied); the control of selection bias after entry (the extent to which the primary analysis included every person entered into the randomized cohorts); and the control of bias in assessing outcomes (the extent to which those assessing the outcomes were kept unaware of the group assignment of the individuals examined).

The two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2006). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion.

Randomization

We describe for each included study the methods used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

Concelament allocation

We describe for each included study the method used to conceal the allocation sequence in sufficient detail and determined whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during, recruitment.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate (e.g. telephone or central randomization; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

inadequate (open random allocation; unsealed or non-opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear.

Blinding

We have described the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received.

Incomplete outcome data

We have described loss to follow up for the studies.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

In case of heterogeneity we have conducted subgroup analyses by whether women were primiparous or multiparous in order to explore possible causes of heterogeneity. When the heterogeneity was not readily explained by this sensitivity analysis one option is to use a random-effects model. A random-effects meta-analysis model involves an assumption that the effects being estimated in the different studies are not identical, but follow similar distribution. However, as we have previously demonstrated (Villar 2001), the relative risk summary for the random-effects model tends to show a larger treatment effect than the fixed-effect model, while not eliminating the heterogeneity itself.

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

The search identified 14 studies including 5441 women, of which 8 were included (Argentine 1993; Dannecker 2004; Eltorkey 1994; Harrison 1984; House 1986; Klein 1992; Sleep 1984;Rodriguez 2008) and 5 excluded (Coats 1980; Detlefsen 1980; Dong 2004; Henriksen 1992; Werner 1991). There is one ongoing trial (Murphy 2006). The included studies varied in the rate of episiotomies between the intervention and control groups from a difference of 7.6% episiotomies in the restricted group compared with 100% episiotomies in the routine group (Harrison 1984), and 57.1% in the restricted group and 78.9% in the routine group (Dannecker 2004).

For details of included and excluded studies, see table of ‘Characteristics of included studies’ and ‘Characteristics of excluded studies’.

Risk of bias in included studies

The method of treatment allocation in general is sound except for the Harrison 1984 trial where the method of treatment allocation is not clearly established raising concerns about possible selection bias.

Argentine 1993, Dannecker 2004, Eltorkey 1994, House 1986, Klein 1992, Sleep 1984 and Rodriguez 2008 report random allocation and the concealment of the assignment by sealed opaque envelopes reducing the risk of selection bias at entry to the trial. Selection bias after entry is avoided in Dannecker 2004, Eltorkey 1994, Harrison 1984, House 1986, Sleep 1984 and Rodriguez 2008 where all the women randomized are included in the analyses. Sleep 1984 and Dannecker 2004 include long-term follow up, with a loss to follow up of about 33% and 40 % of the participants respectively. Klein 1992 shows a loss to follow up rate of 0.71% for primary outcomes to 5% for secondary outcomes. In the Argentine 1993 trial the total number of women randomized was included in the analysis of the primary outcome with a 5% loss to follow up at delivery, 11% at postnatal discharge and 57% at seven months postpartum. Intention-to-treat analysis was performed in all of the studies.

In the Sleep 1984 trial, the observer measuring the outcomes was blinded to the treatment group assignments. In the Argentine 1993 trial only the assessment of the healing and morbidity outcomes were blinded to the observer. None of the other studies (Eltorkey 1994; Harrison 1984; House 1986; Klein 1992, Rodriguez 2008) reported any effort to blind the observer to the treatment group allocation.

Effects of interventions

The restrictive use of episiotomy shows a lower risk of clinically relevant morbidities including severe perineal trauma (relative risk (RR) 0.67, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.49 to 0.91), posterior perineal trauma (RR 0.88, 95% 0.84 to 0.92), need for suturing perineal trauma (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.81), and healing complications at seven days (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.85). No difference is shown in the incidence of major outcomes such as severe vaginal and perineal trauma nor in pain, dyspareunia or urinary incontinence. The only disadvantage shown in the restrictive use of episiotomy is an increased risk of anterior perineal trauma (RR 1.84, 95% CI 1.61 to 2.10). The secondary comparisons, for both restrictive versus routine mediolateral episiotomy and restrictive versus routine midline episiotomy, show similar results to the overall comparison.

See Data and analyses section .

No trials comparing mediolateral versus midline episiotomy were included because of poor methodological quality.

DISCUSSION

The primary question is whether or not to use an episiotomy routinely. The answer is clear. There is evidence to support the restrictive use of episiotomy compared with routine use of episiotomy. This was the case for the overall comparison and the comparisons of subgroups, that take parity into account.

In light of the available evidence, restrictive use of episiotomy is recommended. However, it needs to be taken into account that long term outcomes were assessed by studies with high loss of follow up.

What type of episiotomy is more beneficial, midline or mediolateral? To date there are only three published trials available (Coats 1980; Detlefsen 1980; Werner 1991), which were excluded from this review. As described in the ‘Characteristics of excluded studies’ table, these trials are of poor methodological quality, making their results uninterpretable. This question, therefore, remains unanswered.

A cost effective analysis study conducted in Argentina (Borghi 2002) has shown that a restrictive episiotomy policy is more effective and less costly than a routine episiotomy policy.

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

There is clear evidence to recommend a restrictive use of episiotomy. These results are evident in the overall comparison and remain after stratification according to the type of episiotomy: restrictive mediolateral versus routine mediolateral or restrictive midline versus routine midline. Until further evidence is available, the choice of technique should be that with which the accoucheur is most familiar.

Implications for research

Several questions remain unanswered and further trials are needed to address them. What are the indications for the restrictive use of episiotomy at an assisted delivery (forceps or vacuum), preterm delivery, breech delivery, predicted macrosomia and presumed imminent tears? There is a pressing need to evaluate which episiotomy technique (mediolateral or midline) provides the best outcome.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Vaginal tears can occur during childbirth, most often at the vaginal opening as the baby’s head passes through, especially if the baby descends quickly. Tears can involve the perineal skin or extend to the muscles and the anal sphincter and anus. The midwife or obstetrician may decide to make a surgical cut to the perineum with scissors or scalpel (episiotomy) to make the baby’s birth easier and prevent severe tears that can be difficult to repair. The cut is repaired with stitches (sutures). Some childbirth facilities have a policy of routine episiotomy.

The review authors searched the medical literature for randomised controlled trials that compared episiotomy as needed (restrictive) compared with routine episiotomy to determine the possible benefits and harms for mother and baby. They identified eight trials involving more than 5000 women. For women randomly allocated to routine episiotomy 75.10% actually had an episiotomy whereas with a restrictive episiotomy policy 28.40% had an episiotomy. Restrictive episiotomy policies appeared to give a number of benefits compared with using routine episiotomy. Women experienced less severe perineal trauma, less posterior perineal trauma, less suturing and fewer healing complications at seven days (reducing the risks by from 12% to 31%); with no difference in occurrence of pain, urinary incontinence, painful sex or severe vaginal/perineal trauma after birth. Overall, women experienced more anterior perineal damage with restrictive episiotomy. Both restrictive compared with routine mediolateral episiotomy and restrictive compared with midline episiotomy showed similar results to the overall comparison with the limited data on episiotomy techniques available from the present trials.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Jean Hay-Smith was the author of previous published version of this review See ’Other published versions of this review’.

José M Belizán was an author on previous versions of this review and Georgina Stamp was a co-author on the first version of this review.

Dr Carroli visited theCochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Review Group’s editorial office in Liverpool in 1996 to prepare the first version of this review, funded by a Shell Fellowship administered by the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

Human Reproduction, World Health Organization, Switzerland.

Centro Rosarino de Estudios Perinatales, Rosario, Argentina.

Secretaria de Salud Publica, Municipalidad de Rosario, Argentina.

External sources

No sources of support supplied

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Generation of randomization by computer from a random sample generator programme, organised in balanced blocks of 100, with stratification by centre and by parity (nulliparous and primiparous) Allocation concealment by sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes, divided according to parity |

|

| Participants | 2606 women. Uncomplicated labour. 37 to 42 weeks’ gestation. Nulliparous or primiparous. Single fetus. Cephalic presentation. No previous caesarean section or severe perineal tears | |

| Interventions | Selective: try to avoid an episiotomy if possible and only do it for fetal indications or if severe perineal trauma was judged to be imminent. Routine: do an episiotomy according to the hospital’s policy prior to the trial | |

| Outcomes | Severe perineal trauma. Middle/upper vaginal tears. Anterior trauma. Any posterior surgical repair. Perineal pain at discharge. Haematoma at discharge. Healing complications, infection and dehiscence at 7 days. Apgar score less than 7 at 1 minute | |

| Notes | Mediolateral episiotomies. Epsiotomy rates were 30% for the restricted group and 80.6% for the routine group | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A - Adequate |

| Methods | Random generation: not stated. Allocation concealment: sealed opaque envelopes. |

|

| Participants | 146 primiparous women. Gestation of > 34 weeks, with an uncomplicated pregnancy and a live singleton fetus. Women were intending to have a vaginal delivery | |

| Interventions | Restrictive: try to avoid an episiotomy even if severe perineal trauma was judged to be imminent and only do it for fetal indications. Liberal: in addition to fetal indications use of episiotomy when a tear is judged to be imminent |

|

| Outcomes | Reduction of episiotomies, increase of intact perinea and only minor perineal trauma, perineal pain in the postpartum period, percentage change in overall anterior perineal trauma, difference of the PH of the umbilical artery, percentage of umbilical artery PH less than 7.15, percentage of Apgar scores less than 7 at 1 minute, maternal blood loss at delivery, percentage of severe perineal trauma | |

| Notes | Mediolateral episiotomies. Epsiotomy rates were 70% for restricted group and 79% for the routine group | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A - Adequate |

| Methods | Random generation: not stated. Allocation concealment: sealed opaque envelopes. |

|

| Participants | 200 primigravid women with live, singleton fetus, cephalic presentation of at least 37 weeks of gestational age, having a spontaneous vaginal delivery. Women were not suffering from any important medical or psychiatric disorder | |

| Interventions | Elective group: the intention was to perform an episiotomy unless it was considered absolutely unnecessary Selective group: the intention was not to perform an episiotomy unless it was absolutely necessary for maternal or fetal reasons |

|

| Outcomes | First, second, third and fourth degree tears, anterior trauma, need for suturing, and neonatal outcomes: Apgar score at 1 and 7 minutes, and stay in neonatal intensive care unit | |

| Notes | Mediolateral episiotomies. Epsiotomy rate were 53% for the restricted group and 83% for the routine group were | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A - Adequate |

| Methods | Generation method of randomization not established. Concealment allocation method not established. ’Allocated randomly’. |

|

| Participants | 181 women primigravid, vaginal delivery, at least 16 years old, no less than 38 weeks’ gestational age, not suffering from any important medical or psychiatric conditions or eclampsia | |

| Interventions | One group were not to undergo episiotomy unless it was considered to be medically essential by the person in charge, that is the accoucheur could see that a woman was going to sustain a greater damage or if the intact perineum was thought to be hindering the achievement of a safe normal or operative delivery Another group were to undergo mediolateral episiotomy. |

|

| Outcomes | Severe maternal trauma. Any posterior perineal trauma. Need for suturing perineal trauma | |

| Notes | Mediolateral episiotomies. Epsiotomy rates were 7.6% for restricted group and 100% for the routine group | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B - Unclear |

| Methods | Generation method of randomization not established. Concealment method of allocation by envelopes. |

|

| Participants | Number of participants not established. There is only information for 165 women available to follow up but it lacks information about those women lost to follow up either because one of the authors was not available, or because of the early discharge scheme. Women were at least 37 weeks’ gestational age, cephalic presentation and vaginal delivery | |

| Interventions | In one group episiotomy was not performed specifically to prevent laceration Another group were to receive standard current management whereby perineal damage was avoided by control of the descent of the head and supporting the perineum at crowning. An episiotomy was made if there was fetal distress, or for maternal reasons to shorten the 2nd stage such as severe exhaustion, inability to complete expulsion or unwillingness to continue pushing. Episiotomy was performed if the perineum appeared to be too tight or rigid to permit delivery without laceration, or if a laceration appeared imminent |

|

| Outcomes | Second degree tear. Third degree tear. Need for perineal suturing. Any perineal pain at 3 days. Healing at 3 days. Tenderness at 3 days. Perineal infection at 3 days. Blood loss during delivery | |

| Notes | Mediolateral episiotomies. Epsiotomy rate for restricted group were 18% and for the routine group were 69% | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A - Adequate |

| Methods | Generation method of randomization not established. Concealment of allocation by opaque, sequentially numbered envelopes |

|

| Participants | 1050 women enrolled at30to 34 weeks’ gestation, from which 703 were randomized. Randomization took place if the women were at least 37 weeks’ gestation, medical conditions developing late in pregnancy, fetal distress, caesarean deliveries and planned forceps. Parity 0, 1 or 2. Between the ages of 18 and 40 years. Single fetus. English or French spoken. Medical or obstetrical low risk determined by the physician | |

| Interventions | “Try to avoid an episiotomy”: the restricted episiotomy instruction “Try to avoid a tear”: the liberal episiotomy instruction. |

|

| Outcomes | Perineal trauma including first, second, third and fourth degree and sulcus tears. Perineal pain at 1, 2, 10 days. Dyspareunia. Urinary incontinence and perineal bulging. Time on resumption and pain of sexual activity. Pelvic floor function. Admission to special care baby unit | |

| Notes | Midline episiotomies. Epsiotomy rates were 43.8% for restricted group and 65% for the routine group | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A - Adequate |

| Methods | Ralloc software (Boston College Department of Economics, Boston, MA) was used to create a random sequence of numbers in blocks with 2, 4, and 6 size permutations | |

| Participants | 446 nulliparous women with pregnancies more than 28 weeks of gestation who had vaginal deliveries | |

| Interventions | Patients were assigned either to the routine episiotomy or the selective episiotomy group, depending on the basis of the randomization sequence kept at the institution. Patients assigned to the selective episiotomy group underwent the procedure only in cases of forceps delivery, fetal distress, or shoulder dystocia or when the operator considered that a severe laceration was impending and could only be avoided by performing an episiotomy. This decision was made by the treating physician. All the patients in the routine episiotomy group underwent the procedure at the time the fetal head was distending the introitus | |

| Outcomes | The primary outcome of severe laceration to perineal tissues was defined as a third-degree laceration when the extent of the lesion included the external anal sphincter totally or partially, and fourth degree laceration when the rectal mucosa was involved. | |

| Notes | Midline episiotomies. Epsiotomy rates were 24.3% for restricted group and 100% for the routine group | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A - Adequate |

| Methods | Generation method of randomization not established. Concealment of allocation by opaque sealed envelopes. |

|

| Participants | 1000 women randomized with spontaneous vaginal deliveries, live singleton fetus, at least 37 completed weeks of gestational age, cephalic presentation From the 1000 original women randomized in the original trial, 922 were available for follow up and 674 of them responded to a postal questionnaire which are the women included in the analysis |

|

| Interventions | “Try to avoid episiotomy”: the intention should be to avoid an episiotomy and performing it only for fetal indications (fetal bradycardia, tachycardia, or meconium stained liquor) “Try to prevent a tear”: the intention being that episiotomy should be used more liberally to prevent tears |

|

| Outcomes | Severe maternal trauma: extension through the anal sphincter or to the rectal mucosa or to the upper 3rd of the vagina. Apgar score less than 7 at 1 minute. Severe or moderate perineal pain 10 days after delivery. Admission to special care baby unit in first 10 days of life. Perineal discomfort 3 months after delivery. No resumption of sexual intercourse 3 months after delivery Any dyspareunia in 3 years. Any incontinence of urine at 3 years. Urinary incontinence severe to wear a pad at 3 years |

|

| Notes | Mediolateral episiotomies. Epsiotomy rates were 10.2% for restricted group and 51.4% for the routine group | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A - Adequate |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| Coats 1980 | The allocation was quasi random and prone to cause selection bias. It is described in the article as, ”women who were admitted to the delivery suite were randomly allocated into two groups by the last digit of their hospital numbers“. In addition, when the staff performed an incision which was inappropriate to the treatment allocation, the woman was removed from the trial.” This withdrawal of women as opposed to the principle of’ intention-to-treat analysis’ increases the risk of selection bias |

| Detlefsen 1980 | This study does not compare the restrictive use of episiotomy versus the routine use of episiotomy |

| Dong 2004 | This study does not compare the restrictive use of episiotomy versus the routine use of episiotomy |

| Henriksen 1992 | The allocation was quasi random. As explained in the article, “the deliveries were assisted by midwives on duty when they arrived on the labour ward”. This method of allocation is very prone to selection bias |

| Werner 1991 | There is no reference about the method of randomization used. The effects are not shown in a quantitative format making the data uninterpretable |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

| Trial name or title | Randomised controlled trial of restrictive versus routine use of episiotomy for instrumental vaginal delivery: a multi-centre pilot study |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Random allocation to: [A] Restrictive use of episiotomy for instrumental vaginal delivery. [B] Routine use of episiotomy for instrumental vaginal delivery |

| Participants | The study aims to recruit 200 women. Inclusion criteria: primigravid women in the third trimester of pregnancy (>36 weeks) with a singleton cephalic pregnancy who are English speakers and have no contra-indication to vaginal birth. Exclusion criteria: Women who are: non-English speakers; who have contra-indication to vaginal birth; multiple pregnancy; malpresentation; multiparous women as the rate ofinstrumental delivery is significantly lower in these women making the effort of recruitment unjustified; women who have not given written informed consent prior to the onset of labour |

| Interventions | Random allocation to: [A] Restrictive use of episiotomy for instrumental vaginal delivery. [B] Routine use of episiotomy for instrumental vaginal delivery |

| Outcomes | Damage to the anal sphincter (third or fourth degree tears). |

| Starting date | 01/09/2005 |

| Contact information | Miss B Strachan Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology St Michael’s Hospital Bristol BS2 8EG Telephone: 0117 928 5594 Fax: 0117 928 5180 E-mail: bryony.strachan@ubht.swest.nhs.uk |

| Notes |

DATA AND ANALYSES

Comparison 1. Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Number of episiotomies | 8 | 5441 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.36, 0.40] |

| 2.1 Midline | 2 | 1143 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.46 [0.41, 0.52] |

| 2.2 Mediolateral | 6 | 4298 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.36 [0.33, 0.38] |

| 4 Assisted delivery rate | 6 | 4210 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.56, 1.05] |

| 4.1 Midline | 2 | 1137 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.50, 1.46] |

| 4.2 Mediolateral | 4 | 3073 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.49, 1.07] |

| 5 Severe vaginal/perineal trauma | 5 | 4838 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.72, 1.18] |

| 5.1 Midline | 2 | 1143 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.55, 1.10] |

| 5.2 Mediolateral | 3 | 3695 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.77, 1.59] |

| 8 Severe perineal trauma | 7 | 4404 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.49, 0.91] |

| 8.1 Midline | 2 | 1143 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.51, 1.07] |

| 8.2 Mediolateral | 5 | 3261 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.55 [0.31, 0.96] |

| 11 Any posterior perineal trauma | 4 | 2079 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.84, 0.92] |

| 11.1 Midline | 1 | 698 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.87, 0.99] |

| 11.2 Mediolateral | 3 | 1381 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.80, 0.91] |

| 14 Any anterior trauma | 6 | 4896 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.84 [1.61, 2.10] |

| 14.1 Midline | 2 | 1143 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.00 [1.45, 2.77] |

| 14.2 Mediolateral | 4 | 3753 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.80 [1.56, 2.09] |

| 17 Need for suturing perineal trauma | 5 | 4133 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.61, 0.81] |

| 20 Estimated blood loss at delivery | 1 | 165 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | −58.0 [−107.57, −8. 43] |

| 21 Moderate/severe perineal pain at 3 days | 1 | 165 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.48, 1.05] |

| 22 Any perineal pain at discharge | 1 | 2422 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.65, 0.81] |

| 23 Any perineal pain at 10 days | 1 | 885 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.78, 1.27] |

| 24 Moderate/severe perineal pain at 10 days | 1 | 885 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.67, 1.62] |

| 25 Use of oral analgesia at 10 days | 1 | 885 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.47 [0.63, 3.40] |

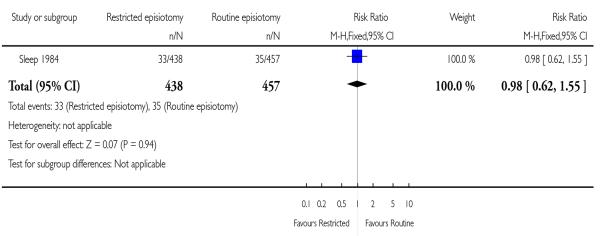

| 26 Any perineal pain at 3 months | 1 | 895 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.62, 1.55] |

| 27 Moderate/severe perineal pain at 3 months | 1 | 895 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.51 [0.65, 3.49] |

| 28 No attempt at intercourse in 3 months | 1 | 895 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.61, 1.39] |

| 29 Any dyspareunia within 3 months | 1 | 895 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.90, 1.16] |

| 30 Dyspareunia at 3 months | 1 | 895 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.22 [0.94, 1.59] |

| 31 Ever suffering dyspareunia in 3 years | 1 | 674 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.21 [0.84, 1.75] |

| 32 Perineal haematoma at discharge | 1 | 2296 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.65, 1.42] |

| 33 Healing complications at 7 days | 1 | 1119 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.56, 0.85] |

| 34 Perineal wound dehiscence at 7 days | 1 | 1118 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.48 [0.30, 0.75] |

| 35 Perineal infection | 2 | 1298 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.48, 2.16] |

| 36 Perineal bulging at 3 months -Midline | 1 | 667 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.50, 1.40] |

| 37 Urinary incontinence within 3-7 months | 2 | 1569 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.79, 1.20] |

| 37.1 Midline | 1 | 674 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.68, 1.32] |

| 37.2 Mediolateral | 1 | 895 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.76, 1.30] |

| 38 Any urinary incontinence at 3 years | 1 | 674 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.77, 1.16] |

| 39 Pad wearing for urinary incontinence | 1 | 674 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.16 [0.71, 1.89] |

| 40 Apgar score less than 7 at 1 minute | 4 | 3908 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.76, 1.43] |

| 41 Admission to special care baby unit | 3 | 1898 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.46, 1.19] |

| 41.1 Midline | 1 | 698 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 41.2 Mediolateral | 2 | 1200 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.46, 1.19] |

| 42 Anorectal incontinence at 7 months | 0 | 0 | Odds Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Comparison 2. Restrictive versus routine (primiparae).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Number of episiotomies | 8 | 3364 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.41 [0.38, 0.44] |

| 1.1 Midline | 2 | 801 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.43 [0.37, 0.48] |

| 1.2 Mediolateral | 6 | 2563 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.40 [0.37, 0.44] |

| 2 Severe vaginal/perineal trauma | 5 | 2541 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.60, 1.12] |

| 2.1 Midline | 2 | 801 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.56, 1.11] |

| 2.2 Mediolateral | 3 | 1740 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.45, 2.07] |

| 3 Severe perineal trauma | 7 | 2944 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.49, 0.94] |

| 3.1 Midline | 2 | 801 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.52, 1.08] |

| 3.2 Mediolateral | 5 | 2143 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.53 [0.28, 1.01] |

| 4 Any posterior trauma | 4 | 1157 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.82, 0.91] |

| 4.1 Midline | 1 | 356 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.93, 1.05] |

| 4.2 Mediolateral | 3 | 801 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.75, 0.87] |

| 5 Any anterior trauma | 5 | 1530 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.52 [1.24, 1.86] |

| 5.1 Midline | 2 | 801 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.26 [1.51, 3.38] |

| 5.2 Mediolateral | 3 | 729 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.27 [1.00, 1.60] |

| 6 Need for suturing perineal trauma | 5 | 2441 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.70, 0.76] |

| 6.2 Mediolateral | 5 | 2441 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.70, 0.76] |

Comparison 3. Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (multiparae).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Number of episiotomies | 4 | 2040 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.27 [0.23, 0.31] |

| 1.1 Midline | 1 | 342 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.50, 0.86] |

| 1.2 Mediolateral | 3 | 1698 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.20 [0.17, 0.24] |

| 2 Severe vaginal/perineal trauma | 3 | 1973 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.52, 2.48] |

| 2.1 Midline | 1 | 342 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.19, 4.61] |

| 2.2 Mediolateral | 2 | 1631 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.21 [0.49, 2.96] |

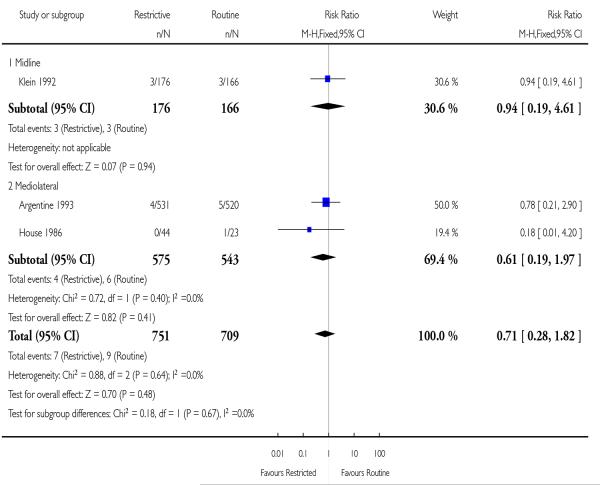

| 3 Severe perineal trauma | 3 | 1460 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.28, 1.82] |

| 3.1 Midline | 1 | 342 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.19, 4.61] |

| 3.2 Mediolateral | 2 | 1118 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.61 [0.19, 1.97] |

| 4 Any posterior perineal trauma | 2 | 922 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.83, 0.99] |

| 4.1 Midline | 1 | 342 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.76, 0.97] |

| 4.2 Mediolateral | 1 | 580 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.83, 1.05] |

| 5 Any anterior trauma | 2 | 922 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.61 [1.19, 2.18] |

| 5.1 Midline | 1 | 342 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.57 [0.91, 2.71] |

| 5.2 Mediolateral | 1 | 580 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.63 [1.13, 2.35] |

| 6 Need for suturing perineal trauma | 3 | 1692 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.72, 0.83] |

| 6.1 Mediolateral | 3 | 1692 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.72, 0.83] |

Analysis 1.2. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 2 Number of episiotomies.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 2 Number of episiotomies

|

Analysis 1.4. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 4 Assisted delivery rate.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 4 Assisted delivery rate

|

Analysis 1.5. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 5 Severe vaginal/perineal trauma.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 5 Severe vaginal/perineal trauma

|

Analysis 1.8. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 8 Severe perineal trauma.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 8 Severe perineal trauma

|

Analysis 1.11. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 11 Any posterior perineal trauma.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 11 Any posterior perineal trauma

|

Analysis 1.14. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 14 Any anterior trauma.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 14 Any anterior trauma

|

Analysis 1.17. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 17 Need for suturing perineal trauma.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 17 Need for suturing perineal trauma

|

Analysis 1.20. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 20 Estimated blood loss at delivery.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 20 Estimated blood loss at delivery

|

Analysis 1.21. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 21 Moderate/severe perineal pain at 3 days.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 21 Moderate/severe perineal pain at 3 days

|

Analysis 1.22. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 22 Any perineal pain at discharge.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 22 Any perineal pain at discharge

|

Analysis 1.23. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 23 Any perineal pain at 10 days.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 23 Any perineal pain at 10 days

|

Analysis 1.24. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 24 Moderate/severe perineal pain at 10 days.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 24 Moderate/severe perineal pain at 10 days

|

Analysis 1.25. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 25 Use of oral analgesia at 10 days.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 25 Use of oral analgesia at 10 days

|

Analysis 1.26. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 26 Any perineal pain at 3 months.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 26 Any perineal pain at 3 months

|

Analysis 1.27. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 27 Moderate/severe perineal pain at 3 months.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 27 Moderate/severe perineal pain at 3 months

|

Analysis 1.28. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 28 No attempt at intercourse in 3 months.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 28 No attempt at intercourse in 3 months

|

Analysis 1.29. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 29 Any dyspareunia within 3 months.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 29 Any dyspareunia within 3 months

|

Analysis 1.30. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 30 Dyspareunia at 3 months.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 30 Dyspareunia at 3 months

|

Analysis 1.31. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 31 Ever suffering dyspareunia in 3 years.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 31 Ever suffering dyspareunia in 3 years

|

Analysis 1.32. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 32 Perineal haematoma at discharge.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 32 Perineal haematoma at discharge

|

Analysis 1.33. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 33 Healing complications at 7 days.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 33 Healing complications at 7 days

|

Analysis 1.34. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 34 Perineal wound dehiscence at 7 days.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 34 Perineal wound dehiscence at 7 days

|

Analysis 1.35. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 35 Perineal infection.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 35 Perineal infection

|

Analysis 1.36. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 36 Perineal bulging at 3 months - Midline.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 36 Perineal bulging at 3 months - Midline

|

Analysis 1.37. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 37 Urinary incontinence within 3-7 months.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 37 Urinary incontinence within 3-7 months

|

Analysis 1.38. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 38 Any urinary incontinence at 3 years.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 38 Any urinary incontinence at 3 years

|

Analysis 1.39. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 39 Pad wearing for urinary incontinence.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 39 Pad wearing for urinary incontinence

|

Analysis 1.40. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 40 Apgar score less than 7 at 1 minute.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 40 Apgar score less than 7 at 1 minute

|

Analysis 1.41. Comparison 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all), Outcome 41 Admission to special care baby unit.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 1 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (all)

Outcome: 41 Admission to special care baby unit

|

Analysis 2.1. Comparison 2 Restrictive versus routine (primiparae), Outcome 1 Number of episiotomies.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 2 Restrictive versus routine (primiparae)

Outcome: 1 Number of episiotomies

|

Analysis 2.2. Comparison 2 Restrictive versus routine (primiparae), Outcome 2 Severe vaginal/perineal trauma.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 2 Restrictive versus routine (primiparae)

Outcome: 2 Severe vaginal/perineal trauma

|

Analysis 2.3. Comparison 2 Restrictive versus routine (primiparae), Outcome 3 Severe perineal trauma.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 2 Restrictive versus routine (primiparae)

Outcome: 3 Severe perineal trauma

|

Analysis 2.4. Comparison 2 Restrictive versus routine (primiparae), Outcome 4 Any posterior trauma.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 2 Restrictive versus routine (primiparae)

Outcome: 4 Any posterior trauma

|

Analysis 2.5. Comparison 2 Restrictive versus routine (primiparae), Outcome 5 Any anterior trauma.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 2 Restrictive versus routine (primiparae)

Outcome: 5 Any anterior trauma

|

Analysis 2.6. Comparison 2 Restrictive versus routine (primiparae), Outcome 6 Need for suturing perineal trauma.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 2 Restrictive versus routine (primiparae)

Outcome: 6 Need for suturing perineal trauma

|

Analysis 3.1. Comparison 3 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (multiparae), Outcome 1 Number of episiotomies.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 3 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (multiparae)

Outcome: 1 Number of episiotomies

|

Analysis 3.2. Comparison 3 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (multiparae), Outcome 2 Severe vaginal/perineal trauma.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 3 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (multiparae)

Outcome: 2 Severe vaginal/perineal trauma

|

Analysis 3.3. Comparison 3 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (multiparae), Outcome 3 Severe perineal trauma.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 3 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (multiparae)

Outcome: 3 Severe perineal trauma

|

Analysis 3.4. Comparison 3 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (multiparae), Outcome 4 Any posterior perineal trauma.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 3 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (multiparae)

Outcome: 4 Any posterior perineal trauma

|

Analysis 3.5. Comparison 3 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (multiparae), Outcome 5 Any anterior trauma.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 3 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (multiparae)

Outcome: 5 Any anterior trauma

|

Analysis 3.6. Comparison 3 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (multiparae), Outcome 6 Need for suturing perineal trauma.

Review: Episiotomy for vaginal birth

Comparison: 3 Restrictive versus routine episiotomy (multiparae)

Outcome: 6 Need for suturing perineal trauma

|

FEEDBACK

Preston, September 2001

Summary

Results

The relative risks reported in the results section have been calculated using a fixed effects analysis. There is significant heterogeneity in the outcomes for suturing and perineal trauma. Use of the fixed effects approach ignores this variability between studies, producing artificially narrow confidence intervals. For example, the relative risk for ‘need for suturing perineal trauma’ changes from 0.74 (0.71,0.77) to 0.71(0.61,0.81) with a random effects model, and that for ‘any anterior trauma’ changes from 1.79 (1.55,2.07) to 1.48 (0.99,2.21). [Summary of comment from Carol Preston, September 2001.]

Reply

In cases of heterogeneity among the results of the studies, it is clearly of interest to determine the causes by conducting subgroup analyses or meta-regression on the basis of biological characteristics of the population, use of different interventions, methodological quality of the studies, etc, to find the source of heterogeneity. Trying to find the source of heterogeneity, we performed beforehand a sensitivity analysis stratifying by parity. When the heterogeneity were not readily explained by this sensitivity analysis, we used a random-effects model. A random-effects meta-analysis model involves an assumption that the effects being estimated in the different studies are not identical, but follow similar distribution. However, one needs to be careful in interpreting these results as, the relative risk summary for the random-effects model tend to show a larger treatment effect than the fixed-effect model while not eliminating the heterogeneity itself (Villar 2001).

Contributors

Guillermo Carroli, Luciano Mignini.

Verdurmen, 1 October 2012

Summary

This important and well-performed review assesses the effects of restrictive use of episiotomy compared with routine episiotomy during vaginal birth. We would like to have more information on several important definitions, used in this review. It is known that there are several strong indications for the use of an episiotomy, such as fetal distress, breech delivery and assisted delivery. We can presume that with “restricted use of episiotomy” the review authors mean that there was no episiotomy used, unless there was such a strong indication for an episiotomy in that specific case. We wonder what the exact indications were in this specific review. To prevent confusion, we think it is necessary to have a clear description of what is meant by a “restrictive use of episiotomy” policy in this Cochrane review.

The exact definitions of “anterior perineal trauma” and “posterior perineal trauma” are described properly under the subheading “description of the condition”. In addition, the various degrees of spontaneous ruptures are well-defined. However, the terms “severe vaginal/perineal trauma” (outcome 5) and “severe perineal trauma” (outcome 8) are not well described. We can assume involvement of the anal sphincter complex (third and fourth degree ruptures) is defined as severe trauma. Unfortunately, this is not described in the background text, although it is of great importance to interpret the outcomes of the review correctly.

Similarly, the exact definitions of Outcomes 21, 24 and 27 (Moderate/severe perineal pain in 3 days; - 10 days; -3 months) are not clear. The methods used in the individual trials to assess the degree of experienced pain, for example the standardized visual analogue score, are not described. In Outcome 33 (Healing complications at 7 days), there is no specification of these complications and/or symptoms involved with healing complications. Therefore, it is not possible for the reader to determine how serious these complications were.

In conclusion, we think that this review would gain strength if the above mentioned definitions are added to the description of the data.

[Comments submitted by KMJ Verdurmen and PJ van Runnard Heimel, September 2012.]

Reply

The authors for this review are currently updating the review and will consider these recommendations when preparing their update.

Contributors

Guillermo Carroli

WHAT’S NEW

Last assessed as up-to-date: 28 July 2008.

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 October 2012 | Feedback has been incorporated | Feedback 2 added. |

HISTORY

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 1997

Review first published: Issue 2, 1997

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 18 January 2012 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 28 July 2008 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | New author. |

| 31 March 2008 | New search has been performed | New search conducted; two new studies included (Dannecker 2004; Rodriguez 2008), two excluded (Detlefsen 1980; Dong 2004) and one new ongoing study identified (Murphy 2006). |

| 31 January 2008 | Feedback has been incorporated | Response to feedback from Carol Preston added. |

| 3 October 2001 | Feedback has been incorporated | Received from Carol Preston, September 2001. |

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN PROTOCOL AND REVIEW

Review methodology section was updated (Higgins 2006).

References to studies included in this review

*Indicates the major publication for the study

- Argentine 1993 {published data only} .Argentine Episiotomy Trial Collaborative Group. Routine vs selective episiotomy: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1993;42:1517–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannecker 2004 {published data only} .Dannecker C, Hillemanns P, Strauss A, Hasbargen U, Hepp H, Anthuber C. Episiotomy and perineal tears presumed to be imminent: randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2004;83(4):364–8. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2004.00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Dannecker C, Hillemanns P, Strauss A, Hasbargen U, Hepp H, Anthuber C. Episiotomy and perineal tears presumed to be imminent: the influence on the urethral pressure profile, analmanometric and other pelvic floor findings - follow up study of a randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2005;84:65–71. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2005.00585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eltorkey 1994 {published data only} .Eltorkey MM, Al Nuaim MA, Kurdi AM, Sabagh TO, Clarke F. Episiotomy, elective or selective: a report of a random allocation trial. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1994;14:317–20. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison 1984 {published data only} .Harrison RF, Brennan M, North PM, Reed JV, Wickham EA. Is routine episiotomy necessary? BMJ. 1984;288:1971–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.288.6435.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House 1986 {published data only} .House MJ, Cario G, Jones MH. Episiotomy and the perineum: a random controlled trial. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1986;7:107–10. [Google Scholar]

- Klein 1992 {published data only} .Klein M, Gauthier R, Jorgensen S, North B, Robbins J, Kaczorowski J, et al. The McGill/University of Montreal multicentre episiotomy trial preliminary results. Innovations in Perinatal Care; Proceedings of the 9th Birth Conference; San Francisco, USA. 1990; Nov 11-13, pp. 44–55. 1990 . [Google Scholar]; Klein MC, Gauthier RJ, Jorgensen SH, Robbins JM, Kaczorowski J, Johnson B, et al. Does episiotomy prevent perineal trauma and pelvic floor relaxation? [Forebygger episiotomi perineal trauma och forsvagning av backenbotten?] Jordemodern. 1993;106(10):375–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Klein MC, Gauthier RJ, Jorgensen SH, Robbins JM, Kaczorowski J, Johnson B, et al. Does episiotomy prevent perineal trauma and pelvic floor relaxation? Online Journal of Current Clinical Trials. 1992 doi: 10.1097/00006254-199404000-00008. Vol. Doc No 10:[6019 words; 65 paragraphs] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Klein MC, Gauthier RJ, Robbins JM, Kaczorowski J, Jorgensen SH, Franco ED, et al. Relationship of episiotomy to perineal trauma and morbidity, sexual dysfunction and pelvic floor relaxation. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1994;171:591–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(94)90070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Klein MC, Kaczorowsky J, Robbins JM, Gauthier RJ, Jorgensen SH, Joshi AK. Physicians’ beliefs and behaviour during a randomized controlled trial of episiotomy: consequences for women in their care. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1995;153:769–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez 2008 {published data only} .Rodriguez A, Arenas EA, Osorio AL, Mendez O, Zuleta JJ. Selective vs routine midline episiotomy for the prevention of third- or fourth-degree lacerations in nulliparous women. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;198(3):285.e1–285.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleep 1984 {published data only} .Sleep J, Grant AM. West Berkshire perineal management trial: three year follow up. BMJ. 1987;295:749–51. doi: 10.1136/bmj.295.6601.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Sleep J, Grant AM, Garcia J, Elbourne D, Spencer J, Chalmers I. The Reading episiotomy trial: a randomised trial comparing two policies for managing the perineum during spontaneous vaginal delivery; Proceedings of 23rd British Congress of Obstetrics and Gynaecology; Birmingham, UK. 1983; Jul 12-15, p. 24. 1983 . [Google Scholar]; Sleep J, Grant AM, Garcia J, Elbourne DR, Spencer JAD, Chalmers I. West Berkshire perineal management trial. BMJ. 1984;289:587–90. doi: 10.1136/bmj.289.6445.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

- Coats 1980 {published data only} .Coats PM, Chan KK, Wilkins M, Beard RJ. A comparison between midline and mediolateral episiotomies. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1980;87:408–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1980.tb04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detlefsen 1980 {published data only} .Detlefsen GU, Vinther S, Larsen P, Schroeder E. Median and mediolateral episiotomy [Median og mediolateral episiotomi] Ugeskrift for Laeger. 1980;142(47):3114–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong 2004 {published data only} .Dong LQ, Li HL, Song ZL. Clinical study and application of the improved episiotomy incision and anesthesia method in the vaginal deliveries. Journal of Qilu Nursing. 2004;10(1):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen 1992 {published data only} .Henriksen T, Beck KM, Hedegaard M, Secher NJ. Episiotomy and perineal lesions in spontaneous vaginal deliveries. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1992;99:950–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb13695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Henriksen TB, Bek KM, Hedegaard M, Secher NJ. Episiotomy and perineal lesions in spontaneous vaginal delivery [Episiotomi og perineale laesioner ved spontane vaginale fodsler] Ugeskrift for Laeger. 1994;156(21):3176–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner 1991 {published data only} .Werner Ch, Schuler W, Meskendahl I. Midline episiotomy versus medio-lateral episiotomy - a randomized prospective study; Proceedings of 13th World Congress of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) (Book 1); Singapore. 1991; Sep 15-20, p. 33. 1991. [Google Scholar]

References to ongoing studies

- Murphy 2006 {published data only} .Murphy DJ. Randomised controlled trial of restrictive versus routine use of episiotomy for instrumental vaginal delivery - a multi-centre pilot study. National Research Register; [accessed 6 July 2006]. www.nrr.nhs.uk [Google Scholar]

Additional references

- Aldridge 1935.Aldridge AN, Watson P. Analysis of end results of labor in primiparas after spontaneous versus prophylactic methods of delivery. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1935;30:554–65. [Google Scholar]

- Borghi 2002.Borghi J, Fox-Rushby J, Bergel E, Abalos E, Hutton G, Carroli G. The cost-effectiveness of routine versus restrictive episiotomy in Argentina. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2002;186:221–8. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.119632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buekens 1985.Buekens P, Lagasse R, Dramaix M, Wollast E. Episiotomy and third degree tears. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1985;92:820–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1985.tb03052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers 1989.Chalmers I, Hetherington J, Elbourne D, Keirse MJNC, Enkin M. Materials and methods used in synthesizing evidence to evaluate the effects of care during pregnancy and childbirth. In: Chalmers I, Enkin MWE, Keirse MJNC, editors. Effective care in pregnancy and childbirth. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1989. pp. 39–65. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham 1993.Cunningham FG. Conduct of normal labor and delivery. In: Cunningham FG, MacDonald PC, Gant NF, Leveno KJ, Gilstrap LC III, editors. Williams obstetrics. 19th Edition Appleton and Lange; Norwalk, CT: 1993. pp. 371–93. [Google Scholar]

- Fernando 2006.Fernando R, Sultan AH, Kettle C, Thakar R, Radley S. Methods of repair for obstetric anal sphincter injury. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002866.pub2. DOI: 10.1002/14651858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando 2007.Fernando RJ, Williams AA, Adams EJ. The management of third or fourth degree perineal tears. RCOG; London: 2007. RCOG Green-top guidelines. No 29. [Google Scholar]

- Gainey 1955.Gainey NL. Postpartum observation of pelvis tissue damage: further studies. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1955;70:800–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)37836-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham 2005.Graham ID, Carroli G, Davies C, Medves JM. Episiotomy rates around the world: an update. Birth. 2005;32:219–23. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2005.00373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton 1861.Hamilton G. Classical observations and suggestions in obstetrics. Edinburgh Medical Journal. 1861;7(313):21. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins 2006.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. The Cochrane Library. 4. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; Chichester, UK: 2006. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 4.2.6 [updated September 2006] [Google Scholar]

- Homsi 1994.Homsi R, Daikoku NH, Littlejohn J, Wheeless CR., Jr. Episiotomy; risks of dehiscence and rectovaginal fistula. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 1994;49:803–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettle 2007.Kettle C, Hills RK, Ismail KMK. Continuous versus interrupted sutures for repair of episiotomy or second degree tears. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000947.pub2. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000947.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lede 1991.Lede R, Moreno M, Belizan JM. Reflections on the routine indications for episiotomy [Reflexiones acerca de la indicacion rutinaria de la episiotomia] Sinopsis Obstétrico-Ginecológica. 1991;38:161–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lede 1996.Lede R, Belizan JM, Carroli G. Is routine use of episiotomy justified? American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1996;174:1399–402. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70579-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascarenhas 1992.Mascarenhas T, Eliot BW, Mackenzie IZ. A comparison of perinatal outcome, antenatal and intrapartum care between England and Wales and France. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1992;99:955–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb13696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ould 1741.Ould F. A treatise of midwifery. J Buckland; London: 1741. pp. 145–6. [Google Scholar]

- RevMan 2008.The Cochrane Collaboration . Review Manager (RevMan). 5.0. The Nordic Cochrane Centre: The Cochrane Collaboration; Copenhagen: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shiono 1990.Shiono P, Klebanoff MA, Carey JC. Midline episiotomies: more harm than good? Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1990;75:765–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thacker 1983.Thacker SB, Banta HD. Benefits and risks of episiotomy: an interpretative review of the english language literature, 1860-1980. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 1983;38:322–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villar 2001.Villar J, Mackey ME, Carroli G, Donner A. Meta-analyses in systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials in perinatal medicine: comparison of fixed and random effects models. Statistics in Medicine. 2001;20(23):3635–47. doi: 10.1002/sim.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

- Hay-Smith 1995a.Hay-Smith J, The Cochrane Collaboration . Liberal use of episiotomy for spontaneous vaginal delivery. In: Enkin MW, Keirse MJNC, Renfrew MJ, Neilson JP, Crowther CA, editors. The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Database. Update Software; Oxford: 1995. [database on disk and CD ROM] Issue 2 . Pregnancy and Childbirth Module . revised 05 May 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hay-Smith 1995b.Hay-Smith J, The Cochrane Collaboration . Midline vs mediolateral episiotomy. In: Enkin MW, Keirse MJNC, Renfrew MJ, Neilson JP, Crowther CA, editors. The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Database. 2. Update Software; Oxford: 1995. [database on disk and CD ROM] Issue 2 . Pregnancy and Childbirth Module. revised 26 January 1994. [Google Scholar]