Abstract

Background

Burkholderia pseudomallei, the causative agent of melioidosis, is a Gram-negative bacterium widely distributed in soil and water in endemic areas. This soil saprophyte can survive harsh environmental conditions, even in soils where herbicides (containing superoxide generators) are abundant. Sigma factor E (σE) is a key regulator of extra-cytoplasmic stress response in Gram-negative bacteria. In this study, we identified the B. pseudomallei σE regulon and characterized the indirect role that σE plays in the regulation of spermidine, contributing to the successful survival of B. pseudomallei in stressful environments.

Results

Changes in the global transcriptional profiles of B. pseudomallei wild type and σE mutant under physiological and oxidative stress (hydrogen peroxide) conditions were determined. We identified 307 up-regulated genes under oxidative stress condition. Comparison of the transcriptional profiles of B. pseudomallei wild type and σE mutant under control or oxidative stress conditions identified 85 oxidative-responsive genes regulated by σE, including genes involved in cell membrane repair, maintenance of protein folding and oxidative stress response and potential virulence factors such as a type VI secretion system (T6SS). Importantly, we identified that the speG gene, encoding spermidine-acetyltransferase, is a novel member of the B. pseudomallei σE regulon. The expression of speG was regulated by σE, implying that σE plays an indirect role in the regulation of physiological level of spermidine to protect the bacteria during oxidative stress.

Conclusion

This study identified B. pseudomallei genes directly regulated by σE in response to oxidative stress and revealed the indirect role of σE in the regulation of the polyamine spermidine (via regulation of speG) for bacterial cell protection during oxidative stress. This study provides new insights into the regulatory mechanisms by which σE contributes to the survival of B. pseudomallei under stressful conditions.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/1471-2164-15-787) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: B. pseudomallei, Transcription profile, Sigma E, SpeG, Oxidative stress

Background

Burkholderia pseudomallei is a Gram-negative bacterium and the causative agent of melioidosis [1, 2]. This serious and often fatal disease of humans and animals such as horses, sheep, goats, pigs and cows is endemic in Southeast Asia and northern Australia [1, 3]. B. pseudomallei is intrinsically resistant to several antibiotics and treatment typically involves an initial parenteral phase of therapy, followed by a prolonged course of oral antibiotics [4]. No melioidosis vaccine is currently available. In endemic areas, B. pseudomallei can be found in soil and in stagnant waters [5]. In the natural environment, this saprophytic bacterium is able to survive a wide range of conditions, including fluctuating temperatures, pH levels, oxygen levels, osmotic pressures and nutritional stresses. During infection, the bacterium is able to survive and replicate in phagocytic or non-phagocytic cells. Within these cells B. pseudomallei may be exposed to free radicals, reactive oxygen intermediates and high osmolality. To survive exposure to stressful environments, B. pseudomallei must be able to activate the appropriate genes and regulate their expression. Many of these genes are organized into regulons which are under the control of sigma factors.

RpoE (σE) is a member of the extra-cytoplasmic function (ECF) subfamily of sigma factors [6] and has been characterized to be one of the most important gene regulatory systems in response to extracellular stress in Gram-negative bacteria. In Escherichia coli K12, the inhibition of σE resulted in increased sensitivity to bacterial cell wall disruption [7] and in Vibrio vulnificus, deletion of σE resulted in increased sensitivity to membrane-perturbing agents such as ethanol, peroxide and SDS [8]. Inactivation of σE in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium) resulted in attenuation in a mouse model of infection [9, 10]. In addition, microarray analysis of a S. Typhimurium σE mutant identified the σE regulon and virulence factors that contributed to disease [11, 12].

A B. pseudomallei rpoE insertional inactivation mutant has previously been constructed and showed increased susceptibility to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), suggesting a role for σE in the oxidative stress response [13]. Furthermore, inactivation of B. pseudomallei σE resulted in reduced survival in J774A.1 macrophages and the mutant was attenuated in a murine model of infection [13, 14]. A proteomic comparison of B. pseudomallei wild type and the σE insertional mutant revealed the differential levels of proteins that may contribute to the stress tolerance and survival of B. pseudomallei [14] but this study was unable to identify all the proteins involved in this response, because of the limitations of the proteomic platform. Recently, the development of a tiling microarray for B. pseudomallei enabled comprehensive transcriptional profiling, providing global snapshots of regulons in response to various stimuli. Analyses of transcriptional profiles of σE would lead to a better understanding of the mechanisms that bacteria use to circumvent environmental stresses. Such microarray studies will also complement our previous proteomic data and is likely to provide new insights to gene members and regulation of these genes under stress.

In this study, global transcriptional profiles of B. pseudomallei in response to H2O2-induced oxidative stress were analyzed. We compared the transcriptional profiles of B. pseudomallei wild type and its isogenic σE mutant under oxidative stress. In addition, the transcriptional profiles also revealed a novel gene member of the σE regulon, speG, that is involved in maintaining the physiological balance of the polyamine spermidine in bacterial cells during oxidative stress. This is the first report to demonstrate the direct and indirect roles of σE contributing to B. pseudomallei survival in the environment.

Results and discussion

Comparative transcriptional profiles of B. pseudomalleiwild type with and without oxidative stress

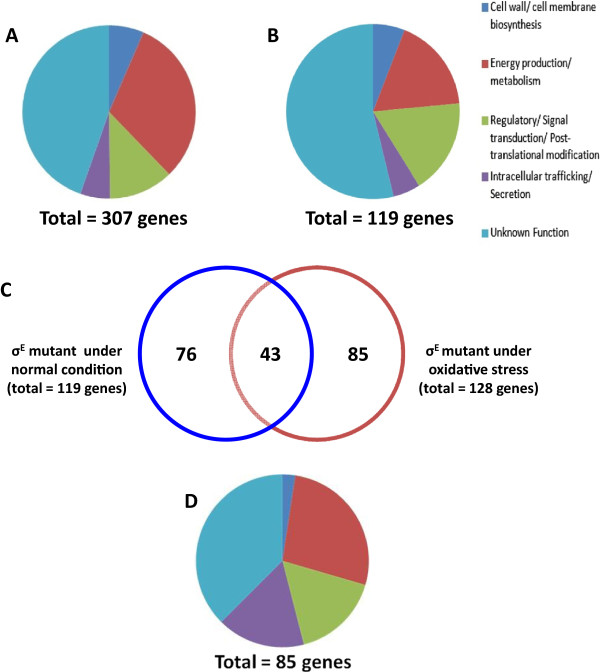

The transcriptional profiles of B. pseudomallei in the presence or absence of 100 μM H2O2 for 10 min were first determined. Analyses of the profiles revealed a total of 649 genes (Additional file 1) that were differentially regulated (≥1 absolute log-transformed fold change) representing approximately 11.0% of all B. pseudomallei K96243 genes. These differentially regulated genes were found on chromosome 1 (57.5%) and chromosome 2 (42.5%). Among the 649 genes, 307 genes were up regulated (47.3% of differentially regulated genes) and 342 genes (52.7%) were down regulated under oxidative stress. Since the objective of this study was to identify B. pseudomallei gene expression in response to oxidative stress, we focused on the analysis of the up-regulated genes. Among 307 up-regulated genes, 221 (72.0%) could be classified into 4 major functional groups according to the Cluster of Orthologous Groups of proteins (COGs) database. These included genes involved in cell wall/membrane biosynthesis; energy and metabolism; regulatory, signal transduction and post-translational modification; intracellular trafficking/secretion system. The remaining 86 genes (28.0%) had unknown functions (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Differentially expressed genes. A) Up-regulated genes under oxidative stress in wild type B. pseudomallei K96243. B) Down-regulated genes under control condition (LB broth) in the σE mutant. C) Comparison of microarray profiles from σE mutant under control and oxidative stress conditions shows 85 genes as σE-dependent oxidative-stress-responsive genes. D) Functional classification of the 85 σE-dependent oxidative-stress-responsive genes.

Of the 307 up-regulated genes, 20 genes (6.5%) were involved in cell wall/cell membrane biosynthesis (Figure 1A) including bpsl0497 (encoding periplasmic TonB protein), bpsl0785 (encoding a peptidase), bpsl3312 (encoding a putative glycosyltransferase), bpss0238 (encoding a penicillin-binding protein) and bpss0711 (encoding an alanine racemase). We also found that genes involved in the transport of lipopolysaccharide (bpsl0963) and capsular polysaccharide (bpsl2806) across the cell membrane to the bacterial cell surface were up-regulated. We found increased expression of mreB (bpsl0186) gene after oxidative stress. MreB is a bacterial ortholog of actin and MreB is reported to be important in maintaining the shape of bacteria [15, 16]. MreB is thought to organize the incorporation of cell wall precursors into the side-wall [17]. The up-regulation of genes involved in cell wall/cell membrane synthesis may reflect their roles in the repair of the cell wall after oxidative stress damage.

In addition to genes involved in cell wall and membrane biosynthesis, 87 genes involved in energy production and metabolism were up-regulated (31% of all up-regulated genes). These included three genes belonging to the sugar transporter superfamily (bpsl1045, bpsl2729, and bpsl2736), and two genes of the Entner-Doudoroff pathway (bpsl2931 and bpsl2932). In addition, many genes related to amino acid utilization (bpsl1076, bpsl2305 and bpsl2497) and amino acid biosynthesis (bpsl3419) were up-regulated when B. pseudomallei was exposed to oxidative stress. We found an increased expression of B. pseudomallei bpsl1784 (encoding ATP-binding cassette transporters) which plays a role in inorganic iron transport. A previous study [18] reported that the bioavailability of iron decreases under oxidative stress conditions, and the up-regulation of bpsl1784 is consistent with this observation. The increased expression of B. pseudomallei fis-regulatory gene (bpsl0609) suggests that BPSL0609 interacts with σ54 (a nitrogen specific sigma factor), with the consequential transcription of genes involved in the metabolism and transportation of nitrogen and carbon and genes involved in alginate and flagella synthesis [19, 20].

We observed an increase in the expression of peroxide scavenging enzymes including katG (catalase-peroxidase; bpsl2865), katB (monofunctional catalase; bpss0993) and ahpC (alkyl hydroperoxide reductase; bpss0492) during exposure to H2O2-induced oxidative stress (Table 1). The expression of B. pseudomallei katG and ahpC is regulated through a global H2O2 sensor and the OxyR transcriptional regulator [21–23]. The increased expression of katG and ahpC after exposure to oxidative stress is consistent with the findings from previous studies [22, 23]. The role of KatG may be to enable B. pseudomallei survival within phagocytes through the detoxification of antibacterial reactive oxygen species.

Table 1.

Selected differentially regulated genes of B. pseudomallei K96243 and σ E mutant under H 2 O 2 –induced oxidative stress

| Gene loci | Description of gene product | Fold change: wild type under oxidative stress compared with untreated control * | Fold change: σ E mutant compared with wild type under oxidative stress |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative stress responsive gene (OSR gene) | |||

| bpss0993 | KatB | 5.90 | NS |

| bpss0492 | AhpC | 4.54 | NS |

| bpsl2865 | KatG | 3.64 | NS |

| bpss0238 | Penicillin-binding protein | 3.03 | NS |

| bpss0281 | 4 Aminobutyrate aminotransferase | 2.80 | NS |

| bpss0711 | Alanine racemase | 2.25 | NS |

| bpsl3142 | BolA-like protein | 1.94 | NS |

| bpsl2285 | Chaperone protein HscA | 1.88 | NS |

| bpsl0497 | Periplasmic TonB protein | 1.54 | NS |

| bpsl2286 | Co-chaperone HscB | 1.43 | NS |

| bpsl1787 | ECF sigma factors | 1.41 | NS |

| bpsl0785 | Peptidase | 1.19 | NS |

| bpsl0963 | Putative permease protein | 1.13 | NS |

| bpsl2806 | Capsular polysaccharide | 1.07 | NS |

| bpss0585 | AraC family transcriptional regulator | 1.07 | NS |

| bpsl1527 | Tex transcriptional factor | 1.05 | NS |

| bpsl0186 | MreB | 1.04 | NS |

| bpsl3312 | Putative glycosyltransferase | 1.00 | NS |

| σ E -dependent and OSR gene | |||

| bpss1837 | Hypothetical protein | 3.37 | −1.84 |

| bpss1839 | Oxidative stress related rubrerythrin protein | 3.36 | −1.68 |

| bpss1838 | Ferredoxin | 3.31 | −1.79 |

| bpsl2931 | Eda (KHG/KDPG_aldolase) | 3.26 | −2.59 |

| bpsl2932 | Phosphogluconate dehydratase | 3.17 | −2.13 |

| bpsl2605 | TrxB | 2.75 | −1.18 |

| bpsl1799 | Putative fimbrial chaperone | 2.70 | −1.71 |

| bpsl1800 | Putative outer membrane usher protein precursor | 2.59 | −1.86 |

| bpss1437 | Lipoprotein | 2.42 | −2.27 |

| bpss1251 | N-carbamoyl-L-amino N-acid amidohydrolase | 2.34 | −1.01 |

| bpss1434 | Membrane-anchored cell surface protein | 2.33 | −3.52 |

| bpsl3419 | Putative GMC oxidoreductase | 2.27 | −1.22 |

| bpss1252 | Inner membrane transport protein | 2.20 | −1.11 |

| bpsl2300 | PdhB | 2.19 | −1.34 |

| bpsl2301 | PdhA | 1.89 | −1.68 |

| bpss0175-0184 | T6SS-4 | ||

| BPSS0175 | 1.89 | −3.67 | |

| BPSS0176 | 1.77 | −3.55 | |

| BPSS 0177 | 1.70 | −3.78 | |

| BPSS 0178 | 1.99 | −2.92 | |

| BPSS 0179 | 1.94 | −2.56 | |

| BPSS 0180 | 1.70 | −2.50 | |

| BPSS 0181 | 1.68 | −2.16 | |

| BPSS0182 | 1.14 | −1.50 | |

| BPSS0183 | 1.06 | −1.09 | |

| BPSS0184 | 1.04 | −1.22 | |

| bpsl2933 | Putative regulatory protein | 1.61 | −1.29 |

| bpsl1042 | Putative lipoprotein | 1.61 | −1.43 |

| bpsl1806 | Subfamily M23B unassigned peptidase | 1.57 | −1.60 |

| bpsl1983 | Putative two component system histidine kinase | 1.41 | −1.00 |

| bpss0796A | H-NS-like protein | 1.41 | −1.32 |

| bpsl0609 | Fis family regulatory protein | 1.31 | −3.20 |

| bpsl0320 | PfkB family carbohydrate kinase | 1.31 | −1.10 |

| bpss0016 | Phospholipase | 1.23 | −2.72 |

| bpss0124 | Response regulator | 1.22 | −2.64 |

| bpsl0785 | Putative lipoprotein | 1.19 | −1.21 |

| bpss1133 | FadH | 1.15 | −1.30 |

| bpss2053 | Cell surface protein | 1.12 | −2.46 |

| bpsl1043 | Putative lipoprotein | 1.12 | −1.44 |

| bpsl3216 | FusA elongation factor EF-2 | 1.10 | −1.10 |

| bpsl1577 | TkrA 2-ketogluconate reductase | 1.06 | −1.30 |

| bpsl1893 | Putative type II/IV secretion system ATP-binding protein | 1.02 | −1.01 |

| σ E -dependent but not OSR gene | |||

| bpsl0096 | SpeG spermidine n(1)-acetyltransferase | NS | −1.29 |

| bpsl0224 | Putative GMC oxidoreductase | NS | −1.24 |

| bpsl0327 | LysR family regulatory protein | NS | −1.85 |

| bpsl2289 | IscS cysteine desulfurase | NS | −1.08 |

| bpss1944 | AdhA alcohol dehydrogenase | NS | −1.01 |

| bpss1945 | AtpG ATP synthase gamma chain | NS | −1.23 |

| bpss1946 | AtpA ATP synthase subunit A | NS | −1.24 |

NS; Not significant different.

*B. pseudomallei cultured in LB broth without H2O2.

The differential transcription profile of B. pseudomallei under oxidative stress revealed that 37 genes (12.1% of oxidative stress responsive genes) were predicted to encode regulatory, signal transduction or post-translational modification-related proteins (Figure 1A). These genes included bpsl0049, encoding a GntR family regulatory protein and bpsl1787, encoding an ECF sigma factor. Several genes involved in transcription regulation such as tex (bpsl1527 encoding a transcriptional factor), nrdR (bpsl2757 encoding a transcriptional regulator) and an araC family gene (bpss0585 encoding a transcriptional regulator) were up-regulated. In Streptococcus pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa the transcription factor Tex is important for bacterial fitness [24]. The NrdR transcription regulator is reported to control the expression of a ribonucleotide reductase involved in deoxyribonucleotide biosynthesis, which is required for DNA replication and repair [25]. Many members of the AraC family transcription regulator have been proven to play critical roles in regulating bacterial virulence factors in response to environmental stress [26]. The high number of regulatory genes up-regulated after exposure to oxidative stress may indicate that B. pseudomallei employs multiple regulation systems in response to oxidative stress.

In addition to genes involved in transcription, a number of chaperone-encoding genes were up-regulated after expsore of the bacteria to oxidative stress including hscA/hscB (bpsl2285/bpsl2286), and groES2 (bpsl2919). HscA is a specialized member of the hsp70 family of molecular chaperones that plays a role in the biosynthesis of several iron-sulfur proteins [27]. Previous studies indicated the essential roles of iron-sulfur proteins in the adaptation of bacteria to iron starvation [28]. Chaperonin GroES2 binds to heat shock protein GroEL to facilitate protein folding in response to environmental stresses [29]. Oxidative stress can cause to protein misfolding, and as a result, the bacterial cells are unable to maintain their protein functions. The up-regulation of genes involved in protein folding may reflect the fact that under oxidative stress conditions, B. pseudomallei proteins are likely to become damaged.

The smallest functional group of proteins that were up-regulated under oxidative stress included 18 genes (5.5% of total up-regulated genes) encoding proteins related to intracellular trafficking and secretion (Figure 1A). Increased expression of proteins in this group, such as type II/IV and VI secretion systems implies that the virulence of B. pseudomallei is likely to be affected by oxidative stress.

Comparative analysis of transcription profiles of B. pseudomalleiwild type and σEmutant without oxidative stress

We have previously reported the construction of B. pseudomallei σE mutant. The mutant shows increased susceptibility to killing by H2O2, indicating the role of σE in regulating resistance to oxidative stress [13, 14]. To identify the σE regulon under oxidative stress conditions, we first investigated the transcriptional profiles of B. pseudomallei wild type and the σE mutant grown in LB medium without antibiotic supplementation. Analysis of the transcription profiles revealed that a total of 350 genes (Additional file 2) were differentially regulated (≥1 absolute log fold change), representing approximately 5.9% of the total B. pseudomallei K96243 genes. These differentially regulated genes were distributed on both chromosome 1 (59.4%) and chromosome 2 (40.6%). In total, 231 genes were up-regulated (66.0% of differentially regulated genes) and 119 genes (34.0%) were down-regulated in the σE mutant. The down-regulation of genes may indicate either direct or indirect regulation by σE. Among the down-regulated genes, 55 (46.2%) could be classified into 4 major COG functional groups, including 7 genes (5.9%) predicted to be involved in cell wall/cell membrane biosynthesis, 21 genes (17.6%) involved in energy production/metabolisms, 21 genes (17.6%) involved in regulatory/signal transduction/post-translational modification and repair, and 6 genes (5.1%) involved in intracellular trafficking/secretion (Figure 1B). The remaining 64 genes (53.8%) have unknown functions.

Comparative analysis of transcription profiles of B. pseudomalleiwild type and σEmutant under oxidative stress

To identify σE-dependent genes that are differentially expressed under oxidative stress conditions, we compared the transcriptome profiles of the σE mutant and wild type which had been exposed to oxidative stress. The bacteria were treated with H2O2 for 10 min before RNA extraction and microarray analysis. A total of 404 genes (Additional file 3) were differentially regulated (≥1 absolute log fold change) representing approximately 6.81% of the total B. pseudomallei K96243 genes. Of these, 276 genes were up-regulated in the σE mutant (68.3% of the total differentially regulated genes) and were located on either chromosome 1 (56.5%) or chromosome 2 (43.5%). Among the 128 down-regulated genes in the σE mutant, 43 genes were also down-regulated in the mutant under normal growth conditions. By excluding these genes, we identified 85 genes defined as the σE-dependent oxidative stress regulon (Figure 1C). These 85 genes were distributed on both chromosome 1 (53.1%) and chromosome 2 (46.9%). Two genes (2.4%) were predicted to be involved in cell wall/cell membrane biosynthesis, 23 genes (27.1%) in energy production/metabolisms, 14 genes (16.5%) in regulatory/signal transduction/post-translational modification and repair, 14 genes (16.5%) in intracellular trafficking/secretion. The remaining 32 genes (37.5%) had unknown functions (Figure 1D).

Amongst the 85 genes making up the σE-dependent oxidative stress regulon, bpsl1806 is predicted to be involved in cell wall/cell membrane biosynthesis and bpss0265 is predicted to encode a membrane protein related to metalloendopeptidases and porins. Genes involved in energy production and metabolism included bpsl0320-0321 (sugar kinase and N-acyl-D-glucosamine 2-epimerase), bpsl2931 (KHG/KDPG aldolase) and bpsl2300-l2301 (pyruvate dehydrogenase complex). The absence of a functional σE under oxidative stress affected the expression of bpss1838-1839 (encoding ferredoxin and rubrerythrin proteins), genes that play important roles in increasing tolerance and resistance to oxidative stress [30].

We identified 14 (16.5%) σE-regulated genes involved in regulatory, signal transduction and post-translational modification after oxidative stress including bpsl0609 (encoding fis-regulatory protein), bpsl1983 (putative two-component system, histidine kinase), bpsl2933 (putative regulatory protein), bpss0124 (two-component system, response regulator) and bpsl2605 (trxB). The latter encodes thioredoxin reductase which functions in post-translational modification. In addition, site-specific recombinase (bpsl2881), which is involved in DNA replication, recombination and repair, was also under σE regulation.

Intracellular trafficking and secretion genes accounted for 12.8% of σE-dependent oxidative stress responsive genes. These included genes of the type II secretion system (bpsl1893), fimbrial proteins (bpsl1798-1800) and membrane-anchored cell surface protein (bpss1434). B. pseudomallei contains six clusters type VI secretion system (T6SS-1 to T6SS-6) [31]. The expression of T6SS genes has been reported to be induced in vivo [31–33]. A previous study reported that the T6SS-1 cluster is important for host adaptation of B. pseudomallei within phagocytes, and that the expression of genes in this cluster is significantly elevated after infection of murine macrophages [31]. We found the increased expression of ten genes (bpss0175-0184) belonging to T6SS-4 under oxidative stress conditions suggesting that T6SS-4 may play a role in combating oxidative stress.

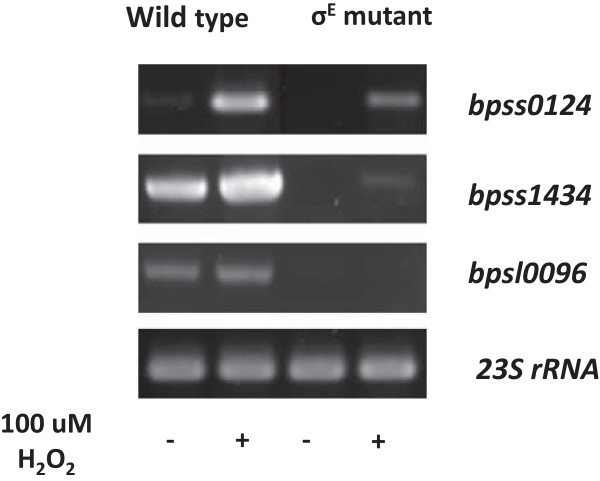

RT-PCR analysis of genes under normal and oxidative stress conditions

To validate the results from our microarray analysis, RT-PCR was performed. Figure 2 shows the increased expression of the bpsl0124 and bpss1434 genes in B. pseudomallei wild type after H2O2 treatment. We did not observe a significant difference in expression of bpsl0096 (speG; encoding spermidine-n-1-acetyltransferase). These results are consistent with the microarray data which indicated that bpsl0124 and bpss1434, but not bpsl0096, were up-regulated in response to oxidative stress (Additional file 1). In the B. pseudomallei σE mutant exposed to H2O2 treatment, the expression of the bpsl0124, bpss1434 and bpsl0096 genes was down-regulated compared to the wild type, indicating that these genes are under σE control. These results are also consistent with our microarray results (Additional file 2).

Figure 2.

RT-PCR analysis of genes under normal and oxidative stress conditions. B. pseudomallei wild type or the isogenic σE mutant was incubated for 10 min in the presence or absence of 100 μM H2O2 and RT-PCR analysis carried out. Each row represents an individual gene (bpsl0124, bpss1434 or bpsl0096) and normalized against 23S rRNA expression.

In addition to RT-PCR, the differential transcription profiles were analyzed to ensure the quality of our transcription profile data. For example, we found that 10 genes (bpss0175-0184) encoding B. pseudomallei T6SS-4 were all up-regulated, suggesting that these genes may be co-expressed as an operon and support the validity of our transcriptional profiling results (Table 1).

Other studies have shown that the katG (catalase-peroxidase) and ahpC (alkyl hyperoxide reductase) genes are up-regulated following the exposure of B. pseudomallei to oxidative stress [22, 23]. Our transcriptional data (Table 1) also reveals these patterns of gene expression. Collectively, these results indicate that our data is robust and reliable.

B. pseudomalleiσEindirectly regulates spermidine levels during oxidative stress

Previous studies have suggested that sigma factors regulate speG and consequently spermidine levels [34, 35]. Spermidine is one of the predominant polyamines in Gram-negative bacteria, widely distributed in the environment, and is involved in various biological processes including gene regulation, protein translation and stress resistance [36]. During oxidative stress, spermidine functions as a free radical scavenger and plays an important adjunctive role in protecting bacterial cells from the toxic effects of reactive oxygen species [37]. The intracellular level of spermidine in bacteria is reported to range from 1-3 mM [38]. High concentrations of spermidine are toxic for bacteria. Excess spermidine can be a result of de-regulated bacterial biosynthesis/metabolism or from environmental exposure, inhibiting bacterial growth and even killing the bacterial cells [39]. Therefore, in bacteria, the maintenance of an appropriate intracellular level of spermidine is critical. Excess spermidine can be converted into the physiologically inert acetylspermidine by the spermidine-acetyltransferase (SpeG). A recent study revealed that the speG gene has been silenced by convergent evolution in Shigella and this resulted in elevated levesl of intracellular spermidine. As a result, the survival of Shigella under oxidative stress is enhanced, contributing to its successful pathogenic lifestyle [40].

We observed expression of speG (bpsl0096) in B. pseudomallei wild type under both control and oxidative stress conditions (Figure 2). However, the speG gene was down-regulated in the σE mutant (Additional file 3), indicating that the inactivation of rpoE effected the expression of speG. This suggests that speG is regulated by σE. The decreased gene expression we have observed corroborates our previous proteomic study [14]. To our knowledge, this is the first report on the regulation of speG by σE.

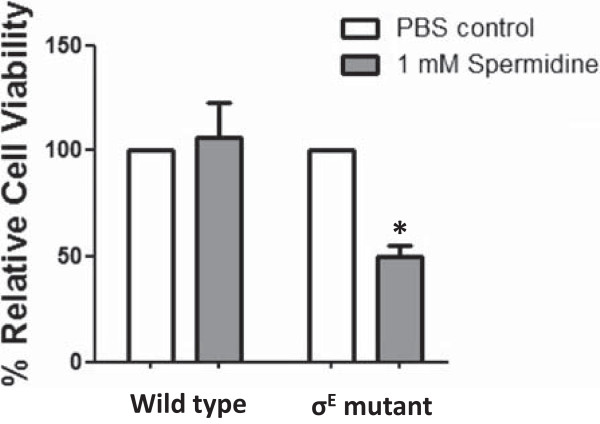

We hypothesised that under high concentrations of spermidine, σE positively regulate expression of speG gene in order to prevent spermidine accumulation, the failure of which, will result in inhibition of B. pseudomallei growth and even cytotoxicity. To test this hypothesis, cultures of B. pseudomallei wild type or σE mutant grown in LB broth were exposed to 1 mM spermidine and the number of viable bacteria determined. The number of wild type bacteria was not affected by the addition of spermidine. This is likely due to the presence of a functional σE gene in the wild type, activating the expression of speG gene. In contrast, in the B. pseudomallei σE mutant, the number of viable bacteria was significantly reduced by the addition of spermidine, indicating the accumulation of spermidine to toxic levels (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of spermidine on the viability of B. pseudomallei wild type or σ E mutant. The numbers of B. pseudomallei wild type or the σE mutant cells were grown in the presence or absence of 1 mM spermidine. After 6 h, the numbers of viable bacteria (colony-forming unit; CFU) were determined after plating onto LB agar. The viability of wild type and σE mutant in the presence of spermidine was calculated from CFU count divided by the CFU count of control condition and multiplied by 100. Values shown are the mean of three independent experiments. Asterisks indicate significant differences (P = 0.038).

This result corroborates the findings from a previous study in E. coli, where excess spermidine was shown to be toxic to bacteria and speG was shown to be important for bacterial viability [41]. Our study provides further evidence that the regulation of speG is affected by σE; speG is a novel member of the σE regulon and σE plays an indirect but important role in the regulation of polyamine levels in bacterial cells to protect the cells during oxidative stress.

Conclusions

DNA tiling arrays were employed to identify global transcriptional profile changes in B. pseudomallei K96243 exposed to oxidative stress induced by H2O2. We have identified not only genes involved in repairing cell wall/membrane biosynthesis but also genes involved in energy and metabolism, regulatory and signal transduction, post translational modification, and intracellular trafficking/secretion genes, which are directly regulated by σE during oxidative stress. We found the increased expression of the B. pseudomallei T6SS-4 under oxidative stress. More importantly, we provided evidence that σE also indirectly regulates the polyamine levels in B. pseudomallei, to protect the cells from oxidative stress.

Methods

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

B. pseudomallei K96243 wild type or the σE mutant [13] was grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or LB agar (Criterion) with or without 50 μg/ml of chloramphenicol (Sigma).

Extraction of bacterial total RNA

B. pseudomallei wild type K96243 or the isogenic σE mutant was harvested after culturing in LB broth without chloramphenicol supplementation. After centrifugation, the cell pellet was washed and treated with TRIZOL (Invitrogen). One-tenth volume of 1-bromo-3-chloro-propane (Sigma) was added to the mixture before centrifugation. The aqueous phase was transferred to a fresh tube containing equal volume of isopropanol to precipitate the total RNA. After centrifugation, the supernatant was discarded; the RNA pellet was washed with 75% ethanol and suspended in RNase-free water. RNA concentration was quantified by spectrophotometer. The isolated bacterial RNA was then treated with DNase I (Ambion) according to manufacturer’s instructions to remove any genomic DNA contamination. DNase inactivation reagent (Ambion) was then added to stop the reaction.

Bacterial mRNA enrichment, cDNA synthesis and microarray hybridization

Bacterial mRNA was enriched from purified total RNA and synthesized into single-stranded cDNA prior to microarray hybridization as described in [42]. The purified cDNAs prepared from B. pseudomallei wild type or σE mutant were labeled with Cy5 or Cy3 respectively (Cy5-ULS Cy3-ULS, Kreatech Diagnostics). Hybridization of labeled cDNA to the array was performed and images acquired from array slides as previously described [43]. Data obtained from hybridizations of two independent RNA preparations of each bacterial strain were used in each analysis.

Design of B. pseudomalleiK96243 high-density tiling microarray

A high-density tiling array based on the sequenced reference genome B. pseudomallei K96243 was custom-fabricated using NimbleGen’s photolithographic Maskless Array Synthesis (MAS) platform (Roche NimbleGen). Using the 7.2 Mb B. pseudomallei K96243 genome sequence, we selected 384,926 50 mer oligonucleotide probes to represent both sense and antisense strands of the B. pseudomallei genome at an average resolution of 35 bp (probes have a mean overlap of 15 bp). Control features that are not complementary to B. pseudomallei K96243 genome, were also included for background checks and alignment purposes. Altogether, 95.1% of the B. pseudomallei K96243 genome, including intergenic regions, is represented on this high-density tiling array.

Data acquisition and preprocessing

Images were acquired with Axon GenePix 4000B laser scanner (Molecular Devices) at 5 μm resolution and intensity data were extracted using the software NimbleScan (Roche NimbleGen). Data obtained from hybridizations of two independent RNA preparations of each sample were used for final analysis. Raw microarray data were first LOWESS (Locally Weighted Scatter Plot Smoother) normalized using GeneSpring GX (Agilent) to correct for dye-bias within array followed by median normalization to normalize across all arrays. Finally, the median ratio of probes corresponding to Sanger’s 5935 genes comparing between B. pseudomallei wild type and σE mutant was computed.

Differential expression analysis

Changes in the expression of genes under oxidative stress (denoted as T) compared to control conditions (denoted as R) were measured in log2 fold change [44]. Specifically, each condition was normalized by a common reference, of which intensity was measured in arrays with Cy5 channels. The common reference (Rc) is B. pseudomallei K96243 grown to stationary phase in LB broth. We computed the difference of two normalized values as the log-transformed fold change: log(T/R) = log(T/Rc) − log(R/Rc). Genes with a log2 fold change ≥ 1 were considered further. The microarray data have been deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) with the identifier, GSE43205. In particular, the data used in this study are as follow: GSM1058304 (sigmaE-mutant + oxidative stress), GSM1058305 (common reference for sigmaE-mutant + oxidative stress), GSM1058306 (sigmaE-mutant control), GSM1058307 (common reference for sigmaE-mutant control), GSM1058508 (wild type + oxidative stress), GSM1058509 (common reference for wild type + oxidative stress), GSM1058519 (wild type control), GSM1058520 (common reference for wild type control).

RT-PCR analysis

An overnight cultured of B. pseudomallei was sub-cultured in 10 ml of LB broth before incubation at 37°C for 6 h (OD600 of 0.8). The logarithmic phase cells were centrifuged and washed with 1x PBS and resuspended into 10 ml of LB broth containing 100 μM H2O2 before incubation at 37°C for 10 min. After H2O2 treatment, bacterial RNA was extracted using Total RNA mini Kit (GeneAid) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. To remove trace genomic DNA, the RNA samples were treated with DNase I (Promaga). The yield and purity of the RNA were determined by spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies). The absence of DNA contamination was confirmed by PCR before proceeding to cDNA synthesis.

SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen) was used to convert total RNA to cDNA. The cDNA was amplified using the PCR with primers (Table 2), GoTaq DNA polymerase (Promega) and cycling conditions of 94°C, 3 min and 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 45 s, followed by incubation at 72°C for 5 min. In each PCR experiment, the amplification of 23S rRNA was used as a normalization control. The amplified products were then visualized using GeneSys software (Syngene). Positive controls were performed with genomic DNA, and negative controls were performed with RNA that had not been subjected to reverse transcription.

Table 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Primer sequence (5’ → 3’) | Purpose | |

|---|---|---|

| 23S-F | TTTCCCGCTTAG ATG CTTT | Forward primer for 23S rRNA |

| 23S-R | AAAGGTACTCTGGGGATAA | Reverse primer for 23S rRNA |

| bpsl0096-F | TCGATTAGTTCGGCCTCGTG | Forward primer for bpsl0096 |

| bpsl0096-R | GAGCTCGACTACATCCACCG | Reverse primer for bpsl0096 |

| bpsl0124-F | ATTATGACGAATGGGAGCAG | Forward primer for bpsl0124 |

| bpsl0124-R | GCGCTTGTTGATGATGAAAT | Reverse primer for bpsl0124 |

| bpss1434-F | GTCGAAGGACGTGAACAGTG | Forward primer for bpss1434 |

| bpss1434-R | ACACGAGAAATTCCGGACAC | Reverse primer for bpss1434 |

Spermidine sensitivity assay

The numbers of B. pseudomallei wild type or the σE mutant cells were adjusted to 100 CFU and subjected to grow in the presence or absence of 1 mM spermidine (Sigma). After 6 h, the bacterial samples were plated onto LB agar to determine the numbers of viable bacteria as CFU. The cell viability of B. pseudomallei under control condition was set as 100%. The viability of B. pseudomallei in the presence of spermidine was calculated from CFU count in the presence of spermidine divided by the CFU count of control condition and multiplied by 100.

Statistical analysis

Average and standard errors of the mean (SEM) were calculated from at least three independent determinations. All tests for significance were performed using the Student’s t-test. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Electronic supplementary material

Additional file 1: Differentially expressed gene of B. pseudomallei K96243 under H 2 O 2 -induced oxidative stress. (XLS 120 KB)

Additional file 2: Differentially expressed gene of B. pseudomallei σ E mutant and K96243 wild type under physiological condition. (XLS 80 KB)

Additional file 3: Differentially expressed gene of B. pseudomallei σ E mutant and K96243 wild type under oxidative stress. (XLS 130 KB)

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Science and Technology Development Agency and Siriraj Grant for Research and Development. S. Jitprasutwit was supported by the Royal Golden Jubilee Ph. D. Program (PHD0270/2551).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CO and WO performed microarray hybridization and analysis. SJ and SK prepared B. pseudomallei RNA, performed bacterial functional assays. SJ, CO, RT and SK wrote the manuscript. SJ and NJ performed RT-PCR. CH, PT, PV, RT and SK participated in study design, coordination or extensive revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Siroj Jitprasutwit, Email: Sjitprasutwit@gmail.com.

Catherine Ong, Email: Catong@dso.org.sg.

Niramol Juntawieng, Email: Niramol_immuno@yahoo.com.

Wen Fong Ooi, Email: Ooiwf@gis.a-star.edu.sg.

Claudia M Hemsley, Email: C.Mueller@exeter.ac.uk.

Paiboon Vattanaviboon, Email: paiboon@cri.or.th.

Richard W Titball, Email: R.W.Titball@exeter.ac.uk.

Patrick Tan, Email: Tanbop@gis.a-star.edu.sg.

Sunee Korbsrisate, Email: Sunee.kor@mahidol.ac.th.

References

- 1.Abraham KA. Studies on DNA-dependent RNA polymerase from Escherichia coli. 1. The mechanism of polyamine induced stimulation of enzyme activity. Eur J Biochem. 1968;5(1):143–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1968.tb00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wuthiekanun V, Mayxay M, Chierakul W, Phetsouvanh R, Cheng AC, White NJ, Day NP, Peacock SJ. Detection of Burkholderia pseudomallei in soil within the Lao People's Democratic Republic. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(2):923–924. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.2.923-924.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiersinga WJ, van der Poll T, White NJ, Day NP, Peacock SJ. Melioidosis: insights into the pathogenicity of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4(4):272–282. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanthawong S, Nazmi K, Wongratanacheewin S, Bolscher JG, Wuthiekanun V, Taweechaisupapong S. In vitro susceptibility of Burkholderia pseudomallei to antimicrobial peptides. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;34(4):309–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wuthiekanun V, Smith MD, White NJ. Survival of Burkholderia pseudomallei in the absence of nutrients. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995;89(5):491. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(95)90080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Las PA, Connolly L, Gross CA. SigmaE is an essential sigma factor in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1997;179(21):6862–6864. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.21.6862-6864.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayden JD, Ades SE. The extracytoplasmic stress factor, sigmaE, is required to maintain cell envelope integrity in Escherichia coli. PLoS One. 2008;3(2):e1573. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown RN, Gulig PA. Roles of RseB, sigmaE, and DegP in virulence and phase variation of colony morphotype of Vibrio vulnificus. Infect Immun. 2009;77(9):3768–3781. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00205-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Humphreys S, Stevenson A, Bacon A, Weinhardt AB, Roberts M. The alternative sigma factor, sigmaE, is critically important for the virulence of Salmonella typhimurium. Infect Immun. 1999;67(4):1560–1568. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.1560-1568.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Testerman TL, Vazquez-Torres A, Xu Y, Jones-Carson J, Libby SJ, Fang FC. The alternative sigma factor sigmaE controls antioxidant defences required for Salmonella virulence and stationary-phase survival. Mol Microbiol. 2002;43(3):771–782. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skovierova H, Rowley G, Rezuchova B, Homerova D, Lewis C, Roberts M, Kormanec J. Identification of the sigmaE regulon of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Microbiology. 2006;152(Pt 5):1347–1359. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28744-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis C, Skovierova H, Rowley G, Rezuchova B, Homerova D, Stevenson A, Spencer J, Farn J, Kormanec J, Roberts M. Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium HtrA: regulation of expression and role of the chaperone and protease activities during infection. Microbiology. 2009;155(Pt 3):873–881. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.023754-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Korbsrisate S, Vanaporn M, Kerdsuk P, Kespichayawattana W, Vattanaviboon P, Kiatpapan P, Lertmemongkolchai G. The Burkholderia pseudomallei RpoE (AlgU) operon is involved in environmental stress tolerance and biofilm formation. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;252(2):243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thongboonkerd V, Vanaporn M, Songtawee N, Kanlaya R, Sinchaikul S, Chen ST, Easton A, Chu K, Bancroft GJ, Korbsrisate S. Altered proteome in Burkholderia pseudomallei rpoE operon knockout mutant: insights into mechanisms of rpoE operon in stress tolerance, survival, and virulence. J Proteome Res. 2007;6(4):1334–1341. doi: 10.1021/pr060457t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Figge RM, Divakaruni AV, Gober JW. MreB, the cell shape-determining bacterial actin homologue, co-ordinates cell wall morphogenesis in Caulobacter crescentus. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51(5):1321–1332. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2003.03936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doi M, Wachi M, Ishino F, Tomioka S, Ito M, Sakagami Y, Suzuki A, Matsuhashi M. Determinations of the DNA sequence of the mreB gene and of the gene products of the mre region that function in formation of the rod shape of Escherichia coli cells. J Bacteriol. 1988;170(10):4619–4624. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.10.4619-4624.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaballah A, Kloeckner A, Otten C, Sahl HG, Henrichfreise B. Functional analysis of the cytoskeleton protein MreB from Chlamydophila pneumoniae. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e25129. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pantopoulos K, Hentze MW. Rapid responses to oxidative stress mediated by iron regulatory protein. EMBO J. 1995;14(12):2917–2924. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07291.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cases I, Ussery DW, de Lorenzo V. The sigma54 regulon (sigmulon) of Pseudomonas putida. Environ Microbiol. 2003;5(12):1281–1293. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2003.00528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Studholme DJ, Wigneshwereraraj SR, Gallegos MT, Buck M. Functionality of purified sigma(N) (sigma(54)) and a NifA-like protein from the hyperthermophile Aquifex aeolicus. J Bacteriol. 2000;182(6):1616–1623. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.6.1616-1623.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dowling AJ, Wilkinson PA, Holden MT, Quail MA, Bentley SD, Reger J, Waterfield NR, Titball RW, Ffrench-Constant RH. Genome-wide analysis reveals loci encoding anti-macrophage factors in the human pathogen Burkholderia pseudomallei K96243. PLoS One. 2010;5(12):e15693. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loprasert S, Whangsuk W, Sallabhan R, Mongkolsuk S. Regulation of the katG-dpsA operon and the importance of KatG in survival of Burkholderia pseudomallei exposed to oxidative stress. FEBS Lett. 2003;542(1–3):17–21. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00328-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loprasert S, Sallabhan R, Whangsuk W, Mongkolsuk S. Compensatory increase in ahpC gene expression and its role in protecting Burkholderia pseudomallei against reactive nitrogen intermediates. Arch Microbiol. 2003;180(6):498–502. doi: 10.1007/s00203-003-0621-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He X, Thornton J, Carmicle-Davis S, McDaniel LS. Tex, a putative transcriptional accessory factor, is involved in pathogen fitness in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microb Pathog. 2006;41(6):199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nordlund P, Reichard P. Ribonucleotide reductases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:681–706. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gallegos MT, Schleif R, Bairoch A, Hofmann K, Ramos JL. Arac/XylS family of transcriptional regulators. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61(4):393–410. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.4.393-410.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vickery LE, Cupp-Vickery JR. Molecular chaperones HscA/Ssq1 and HscB/Jac1 and their roles in iron-sulfur protein maturation. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;42(2):95–111. doi: 10.1080/10409230701322298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wandersman C, Delepelaire P. Bacterial iron sources: from siderophores to hemophores. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2004;58:611–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Llorca O, Galan A, Carrascosa JL, Muga A, Valpuesta JM. GroEL under heat-shock. Switching from a folding to a storing function. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(49):32587–32594. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sztukowska M, Bugno M, Potempa J, Travis J, Kurtz DM., Jr Role of rubrerythrin in the oxidative stress response of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Mol Microbiol. 2002;44(2):479–488. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shalom G, Shaw JG, Thomas MS. In vivo expression technology identifies a type VI secretion system locus in Burkholderia pseudomallei that is induced upon invasion of macrophages. Microbiology. 2007;153(Pt 8):2689–2699. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/006585-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Das S, Chakrabortty A, Banerjee R, Roychoudhury S, Chaudhuri K. Comparison of global transcription responses allows identification of Vibrio cholerae genes differentially expressed following infection. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;190(1):87–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Potvin E, Lehoux DE, Kukavica-Ibrulj I, Richard KL, Sanschagrin F, Lau GW, Levesque RC. In vivo functional genomics of Pseudomonas aeruginosa for high-throughput screening of new virulence factors and antibacterial targets. Environ Microbiol. 2003;5(12):1294–1308. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Samuel Raj V, Full C, Yoshida M, Sakata K, Kashiwagi K, Ishihama A, Igarashi K. Decrease in cell viability in an RMF, sigma(38), and OmpC triple mutant of Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;299(2):252–257. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)02627-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Terui Y, Higashi K, Tabei Y, Tomitori H, Yamamoto K, Ishihama A, Igarashi K, Kashiwagi K. Enhancement of the synthesis of RpoE and StpA by polyamines at the level of translation in Escherichia coli under heat shock conditions. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(17):5348–5357. doi: 10.1128/JB.00387-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shah P, Swiatlo E. A multifaceted role for polyamines in bacterial pathogens. Mol Microbiol. 2008;68(1):4–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ha HC, Sirisoma NS, Kuppusamy P, Zweier JL, Woster PM, Casero RA., Jr The natural polyamine spermine functions directly as a free radical scavenger. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(19):11140–11145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen SS. A guide to the polyamines. New York; Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 39.He Y, Kashiwagi K, Fukuchi J, Terao K, Shirahata A, Igarashi K. Correlation between the inhibition of cell growth by accumulated polyamines and the decrease of magnesium and ATP. Eur J Biochem. 1993;217(1):89–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barbagallo M, Di Martino ML, Marcocci L, Pietrangeli P, De Carolis E, Casalino M, Colonna B, Prosseda G. A new piece of the Shigella pathogenicity puzzle: spermidine accumulation by silencing of the speG gene. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27226. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fukuchi J, Kashiwagi K, Yamagishi M, Ishihama A, Igarashi K. Decrease in cell viability due to the accumulation of spermidine in spermidine acetyltransferase-deficient mutant of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(32):18831–18835. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.32.18831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun GW, Chen Y, Liu Y, Tan GY, Ong C, Tan P, Gan YH. Identification of a regulatory cascade controlling Type III Secretion System 3 gene expression in Burkholderia pseudomallei. Mol Microbiol. 2010;76(3):677–689. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ong C, Ooi CH, Wang D, Chong H, Ng KC, Rodrigues F, Lee MA, Tan P. Patterns of large-scale genomic variation in virulent and avirulent Burkholderia species. Genome Res. 2004;14(11):2295–2307. doi: 10.1101/gr.1608904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ooi WF, Ong C, Nandi T, Kreisberg JF, Chua HH, Sun G, Chen Y, Mueller C, Conejero L, Eshaghi M, Ang RM, Liu J, Sobral BW, Korsrisate S, Gen YH, Titball RW, Bancroft GJ, Valade E, Tan P. The condition-dependent transcriptional landscape of Burkholderia pseudomallei. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(9):e1003795. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Differentially expressed gene of B. pseudomallei K96243 under H 2 O 2 -induced oxidative stress. (XLS 120 KB)

Additional file 2: Differentially expressed gene of B. pseudomallei σ E mutant and K96243 wild type under physiological condition. (XLS 80 KB)

Additional file 3: Differentially expressed gene of B. pseudomallei σ E mutant and K96243 wild type under oxidative stress. (XLS 130 KB)