Abstract

Background/Aims:

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), cholangiocarcinoma (CC) and hepatoblastoma (HB) are the main hepatic malignancies with limited treatment options and high mortality. Recent studies have implicated Hippo Kinase pathway in cancer development but detailed analysis of Hippo Kinase signaling in human hepatic malignancies, especially CC and HB, is lacking.

Methods:

We investigated Hippo Kinase signaling in HCC, CC and HB using cells and patient samples.

Results:

Increased expression of yes-associated protein (Yap), the downstream effector of the Hippo Kinase pathway, was observed in HCC cells and siRNA-mediated knockdown of Yap resulted in decreased survival of HCC cells. The density-dependent activation of Hippo Kinase pathway characteristic of normal cells was not observed in HCC cells and CCLP cells, a cholangiocarcinoma cell line. Immunohistochemistry of Yap in HCC, CC and HB tissues indicated extensive nuclear localization of Yap in majority of tissues. Western blot analysis performed using total cell extracts from patient samples and normal livers showed extensive activation of Yap. Marked induction of glypican-3, CTGF and Survivin, the three Yap target genes was observed in the tumor samples. Further analysis revealed significant decrease in expression and activity of Lats kinase, the main upstream regulator of Yap. However, no change in activation of Mst-2 kinase, the upstream regulator of Lats kinase was observed.

Conclusions:

These data show that Yap induction mediated by inactivation of Lats is observed in hepatic malignancies. These studies highlight Hippo Kinase pathway as a novel therapeutic target for hepatic malignancies.

Keywords: Cholangiocarcinoma, Hepatoblastoma, HCC, Lats, Yap

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), cholangiocarcinoma (CC) and hepatoblastoma (HB) are the three main hepatic malignancies, all with extremely grim prognosis (1, 2). The incidence of all three hepatic cancers is rising in the US (3-6). The treatment options for these hepatic malignancies are extremely limited mainly because the mechanisms of pathogenesis of these cancers are not completely known (7). Recent studies show that deregulation of Hippo Kinase pathway, a signaling pathway involved in organ size regulation, results in HCC development in rodents (8-11). However, clinical data on the status of Hippo Kinase signaling is limited. Furthermore, the role of Hippo Kinase pathway in pathogenesis of CC and HB remains to be studied.

The downstream effector of the pathway is a transcriptional coactivator called yes-associated protein (Yap) (12). Yap partners with transcription factor TEAD to initiate number of genes involved in cell proliferation including Survivin (BIRC5), CTGF, and Cyclin D1. In proliferating cells, Yap forms a heterodimer with TEAD and initiates pro-mitogenic gene expression. The Hippo Kinase pathway is activated by cell-cell contact resulting in phosphorylation-dependent activation of a cascade of serine-threonine kinases. This includes Mst, a STE 20-like kinase, which phosphorylates and activates Lats kinase. Once activated, Lats partners with a small adapter protein called Mob and phosphorylates Yap on Ser127 (Ser112 in mice) initiating cytoplasmic retention of Yap and subsequent 14-3-3-mediated degradation. Decrease in Yap results in inhibition of cell proliferation (12, 13).

Increase in Yap activity (nuclear localization and decreased phosphorylation) results in increased cell proliferation and HCC formation in mice (9). It is also known that dysfunctional Hippo Kinase signaling is involved in cancers of a number of organs including breast, pancreas, and prostate (13). Although experimental data generated using rodent models has shown involvement of Hippo Kinase pathway in HCC development, detailed clinical studies are lacking. In the present study we have investigated involvement of Hippo Kinase Pathway in human HCC, CC and HB using tissue arrays and patient samples. Our results show that Yap activation is critical in HCC pathogenesis and demonstrate, for the first time, deregulation of Hippo Kinase pathway in CC and HB.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Yap knockdown experiments

Two human HCC cell lines were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and the human CC cell line; CCLP was a kind gift from Dr. A. J. Demetris of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA. CCLP, HepG2 and Hep3B cells were grown in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum. HepaRG cells were cultured in either proliferation medium or differentiation medium and RIPA extracts were collected as described before (14). Yap knockdown experiments were conducted in Hep3B cells using Mission® shRNA purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Cells were transfected with either control shRNA or Yap shRNA using FUGENE-6 (Roche Applied Sciences, Indianapolis, IN) for 48 hr. Cell viability was assessed by MTT assay as previously described (15). Primary human hepatocytes were obtained from XenoTech LLC (Lenexa, KS) and used for preparation of RIPA extracts along with HepG2 and Hep3B cells as described previously (15).

Immunofluorescence Staining

For immunofluorescence studies cells were grown in 2-chamber slides. Cells were fixed with 10% formalin and blocked with 5% normal donkey serum. Rabbit anti-Yap primary antibody (Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers MA) was used at a concentration of 1:100 followed by Alexa®-594 conjugated donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody at a concentration of 1:500. Cells were washed between the primary and secondary antibody application with PBS with 0.1% Tween-20. Following secondary antibody cells were mounted in Prolong Gold Anti-Fade mounting medium containing DAPI for nuclear counter staining. Immunofluorescence signal was detected on an Olympus BX51 upright microscope and photographs were taken using a DX71 camera system.

Tissue Arrays and HB Immunohistochemistry

Tissue arrays (Cat# BC03116 and BC03002) were purchased from US Biomax (Rockville, MD). BC03116 has a total of 70 individual cases including 40 HCC, 13 cancer adjacent normal liver and 17 normal liver tissue cores. BC03002 has total of 80 individual cases including 30 HCC, 16 cholangiocarcinoma, 16 cirrhosis, 10 viral hepatitis, 4 cancer adjacent normal livers and 4 normal liver tissues. Each tissue core is 1.5 mm in diameter and 5 μm thickness. Manufacturer provided clinical data including TNM status and tumor grade for each HCC and cholangiocarcinoma specimen (Supplementary Table 1). Tissue array slides were baked at 60°C for 2 hr before proceeding with the immunohistochemistry protocol given below. Seven HB and adjacent normal tissue paraffin slides were obtained from the Children’s Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, MO. Clinical information on the two of the seven samples was not available. Additionally, 15 HB tissue paraffin slides were obtained from Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC, Pittsburgh, PA. Clinical characteristics of these HB samples are in supplementary table 3. All clinical samples were obtained under IRB approvals of the respective institutions. All slides were stained for Yap immunohistochemistry as following: after deparaffinization, slides were treated with 3% H2O2 followed by Citrate buffer antigen retrieval. Slides were washed in TBS with 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T) as washing buffer and blocked in 5% normal donkey serum in TBS-T. After blocking Rabbit anti-Yap Primary antibody was applied at a concentration of 1:100 (Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA) at 4°C overnight. Slides were washed with TBS-T and incubated in donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody was used at 1:500 (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA). The signal was visualized with combination of ABC Vectastain kit and DAB (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA). Slides were studied under the Olympus BX51 upright light microscope equipped with a DP-71 camera for obtaining photomicrographs.

Yap Staining Intensity Score

Yap staining was graded in a blinded fashion for all tissue cores. Each tissue core was graded for strong nuclear staining (>75% of cells with nuclear staining), mild nuclear staining (up to 25% cells with nuclear staining) or cytoplasmic staining (no nuclear staining). The staining grade scores were used to generate bar graphs. Some samples including HCC and adjacent normal tissues showed both nuclear and cytoplasmic staining. When scoring, the sample was placed in the group (high nuclear, low nuclear and cytoplasmic) with the predominant staining pattern.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed on 7 normal and 7 HCC specimens obtained from the University of Kansas Medical Center Liver Bank (clinical characteristics in Supplementary Table 2). All studies were performed under the guidelines of KU Institutional Review Board. The normal liver tissues were obtained from the livers deemed adequate for liver transplantation. RIPA extracts were prepared from the liver samples, protein estimation was conducted using the BCA protein assay and used for Western blot analysis as previously described (16). All primary and secondary antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology and used at a concentration of 1:1000 and 1:2000, respectively, according to manufacturer’s protocol.

Real Time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from normal and HCC tissues using the TRI reagent (Sigma Chemical Co.) and converted to cDNA as described previously (16). CTGF, BIRC5, Glypican 3 and 18S RNA TaqMan Gene Expression assays were purchased from Applied Biosystems and Real Time PCR analysis was performed using TaqMan gene expression master mix on a StepOnePlus sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). The expression of CTGF, BRIC5 and Glypican 3 mRNA was normalized relative to 18S expression levels and comparative Ct method was used to determine relative expression levels.

Statistical Analysis

Comparison between two groups was performed using Student’s T-test. The difference between groups was considered statistically significant at P<0.05.

Results

Increased Yap expression in human HCC cells

We investigated Yap expression in two human HCC cells including HepG2 and Hep3B cells and compared it with primary human hepatocytes. Western blot analysis (Fig. 1A) indicated increased Yap protein in both HepG2 and Hep3B cells as compared to primary human hepatocytes. HepG2 and Hep3B cells had significantly higher nuclear localization of Yap as compared to primary human hepatocytes. Immunofluorescence staining of Yap in Hep3B cells confirmed the nuclear localization of Yap (Fig. 1C). Further, Western blot analysis showed higher expression of CTGF, Glypican 3 and Survivin, three known Yap targets genes in HepG2 and Hep3B cells as compared to primary human hepatocytes (Fig. 1B). To investigate whether Yap knockdown has any effect on Hep3B cell viability, we performed shRNA mediated Yap knockdown. Western blot analysis indicated significant decrease in total and nuclear Yap protein in cells treated with anti-Yap shRNA (Fig. 1D). Yap knockdown was associated with decreased protein expression of Survivin and also resulted in decreased CTGF mRNA expression (Fig 1E). Finally, MTT assay indicated 50% decrease in cell viability after shRNA-mediated Yap knockdown (Fig. 1F).

Fig. 1.

Increased Yap expression in HCC and HB cells. (A) Western blot analysis of Yap in total cell extracts and nuclear protein extracts of HepG2 (a HB cell line), Hep3B (a HCC cell line) and primary human hepatocytes. (B) Western blot analysis of Yap target genes CTGF, Glypican 3 and Survivin in HepG2 cells, Hep3B cells and primary human hepatocytes. (C) Immunofluorescence staining of Yap in Hep3B cells. Top panel is Yap, middle panel is nuclear staining using DAPI and bottom panel shows the merge. Arrows point to nuclear Yap staining. All images at 400x magnification. (D) Western blot of Yap and its target gene Survivin in extracts of Hep3B cells treated with either control shRNA or anti-Yap shRNA. (E) Real Time PCR analysis of CTGF mRNA in Hep3B cells treated with either control or anti-Yap shRNA. (F) Hep3B cell viability following anti-Yap shRNA treatment determined by MTT assay.

Increased Yap expression and activity in human HCC samples

To investigate whether Yap activation is observed in human HCC, we stained tissue arrays containing a total of 70 HCC, 21 normal, and 17 cancer adjacent normal samples. Immunohistochemistry revealed mainly cytoplasmic Yap staining in the normal tissues (Fig. 2A) whereas majority of HCC samples exhibited high nuclear staining (Fig. 2B). Yap staining intensity was scored in blinded fashion in three categories including high nuclear, low nuclear or cytoplasmic staining. More than 85% of HCC samples exhibited high nuclear Yap staining with 18% and 20% samples had either low nuclear or cytoplasmic staining, respectively. Interestingly, 92% of the tumor adjacent normal tissues exhibited both low nuclear and cytoplasmic staining with only 25% samples showing high nuclear staining (Fig. 2C). The samples with high nuclear Yap staining were further divided into three groups according to the Tumor-Node-Metastasis (TNM) status as reported by the manufacturer. None of the tissues were reported to have either lymph node invasion or metastasis. Three percent of tumors with high nuclear Yap staining were in T1, 55% were in T2 stage whereas 42% were in T3 stage (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Yap expression in human HCC tissues. Tissue arrays purchased from US Biomax (Rockville, MD) were stained for Yap. The upper panel shows representative photomicrographs of normal (A) and HCC (B) tissues. Arrowheads indicate nuclear Yap staining. Staining intensity was scored in three categories including high nuclear, low nuclear and cytoplasmic (no nuclear) staining as described in the methods. All images at 400x magnification. (C) Bar graph showing percent of normal, HCC and tumor-adjacent normal tissue samples in each category. (D) The HCC staining intensity data was further stratified using TNM score.

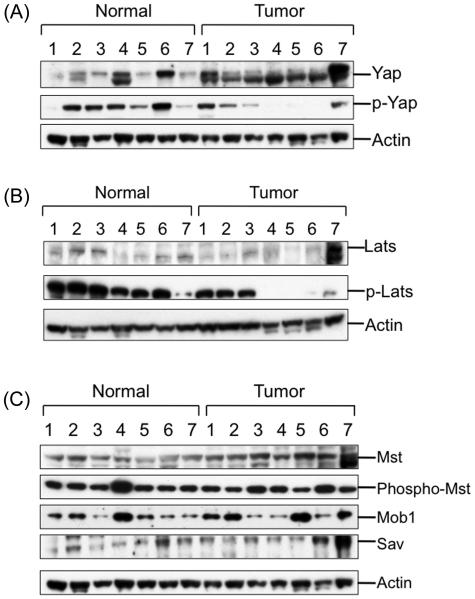

Yap expression correlates with Lats down-regulation in human HCC

We further investigated regulation of Yap by the Hippo Kinase signaling pathway members including Mst, Lats, Mob and Sav1 in a separate set of 7 normal and 7 HCC samples by Western blot analysis. All HCC samples studied had increased Yap expression where as only 2 of the normal samples had comparable Yap expression (Fig. 3A). Substantial phospho-Yap protein was observed in 6 out of 7 normal livers whereas 4 of 7 HCC samples had phospho-Yap expression with only 1 comparable to the expression found in the normal livers. Western blot analysis was able to detect presence of Lats in all normal livers but only in 3 of 7 HCC samples (Fig. 3B). All normal livers had extensive activation of Lats as demonstrated by the presence of phospho-Lats protein. In the case of HCC, the same four samples, which had phospho-Yap protein, also had presence of phospho-Lats.

Fig. 3.

Mechanisms of increased Yap activation in HCC. Western blot analysis was used to determine levels of Hippo Kinase pathway components in total cell extracts of normal and HCC samples. (A) Western blot analysis of total and phospho-Yap (B) Lats and phospho-Lats (active), and (C) Mst, phospho-Mst (active), Mob and Sav (WW45) in normal livers and HCC samples.

We further investigated upstream components of the Hippo Kinase pathway including Mst kinase, Mob and Sav. Western blot analysis of Mst and phospho-Mst (active), the upstream regulator of Lats indicated no difference in either total protein or activity of Mst between normal and HCC samples. Similarly, no difference in Mob and Sav expression was observed between normal and HCC samples (Fig. 3C).

Increased expression of Yap target genes in human HCC

To further analyze the activation of Yap in HCC, we investigated the expression of Yap target genes in the same set of 7 normal and 7 HCC samples using Real Time PCR. We quantified mRNA for connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), baculoviral IAP repeat-containing 5 (BIRC5 also called Survivin) and Glypican 3 using Real Time PCR. The data indicate extensive induction in all three Yap target genes in the HCC samples as compared to normal tissue (Fig. 4A and B). Further, we determined protein expression of CTGF, Glypican 3 and Survivin in three normal livers and three HCC livers with varying degree of Yap activation as determined by phospho-Yap (inactive) levels. The data indicate a positive correlation of Yap activation with expression of Yap targets genes. Tumors with higher Yap activation (i.e. lower phospho-Yap expression) showed higher expression of CTGF, Glypican 3 and Survivin (Fig 4C).

Fig. 4.

Increased expression of Yap target genes in HCC. Quantification of (A) Survivin (BIRC5), CTGF, and (B) Glypican 3 mRNA in normal and HCC samples using Real time PCR. Total RNA was extracted from the same samples used for Western blot analysis data shown in Fig. 3 and was used for Real Time PCR analysis. (C) Western blot analysis of Survivin, CTGF, Glypican 3 and phospho-Yap in three selected normal and HCC livers.

Increased Yap activity in cholangiocarcinoma

A total of 16 individual samples of human CC were analyzed for Yap expression Immunohistochemistry for Yap tissue array showed significant increase in Yap staining in the CC specimens. All the CC tissues had marked increase in nuclear Yap localization (Fig. 5 B, C and E). Staining intensity scoring showed 98% tissue samples with high nuclear staining (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Yap expression in human cholangiocarcinoma tissues. Tissue arrays purchased from US Biomax (Rockville, MD) were stained for Yap. The upper panel shows representative photomicrographs (400x) of (A) normal, (B) and (C) CC tissues. Staining intensity was scored using three categories including high nuclear, low nuclear and cytoplasmic (no nuclear) staining as described in methods. (D) Bar graph showing percent of CC tissue samples in each category. (E) Low magnification (200x) photomicrograph of CC tissue stained for Yap. Arrowheads indicate nuclear Yap staining.

Increased nuclear Yap staining in hepatoblastoma

We stained a total of 22 HB samples along with 5 tumor adjacent normal tissues for Yap. Normal liver showed mainly cytoplasmic Yap staining in hepatocytes with occasional mild nuclear staining. Yap expression in biliary epithelial cells was significantly higher than hepatocytes and most biliary epithelial cells had nuclear Yap staining (Fig. 6 A). In contrast, Yap expression increased in HB specimens and extensive nuclear Yap staining was observed in majority of cells in HB (Fig. 6 B-D). Immunohistochemistry scoring indicated 73% of HB with significantly high nuclear Yap staining indicating substantial deregulation of Hippo Kinase signaling in HB (Fig. 6E).

Fig. 6.

Yap expression in HB tissues. Representative photomicrographs of adjacent normal liver (A), and HB samples (B-D). All images are at 400x magnification. Arrows indicate cytoplasmic Yap staining in the hepatocytes of normal liver. Arrowheads indicate nuclear Yap staining in hepatoblastoma samples. (E) Bar graph showing percent of HB samples with high and moderate nuclear staining.

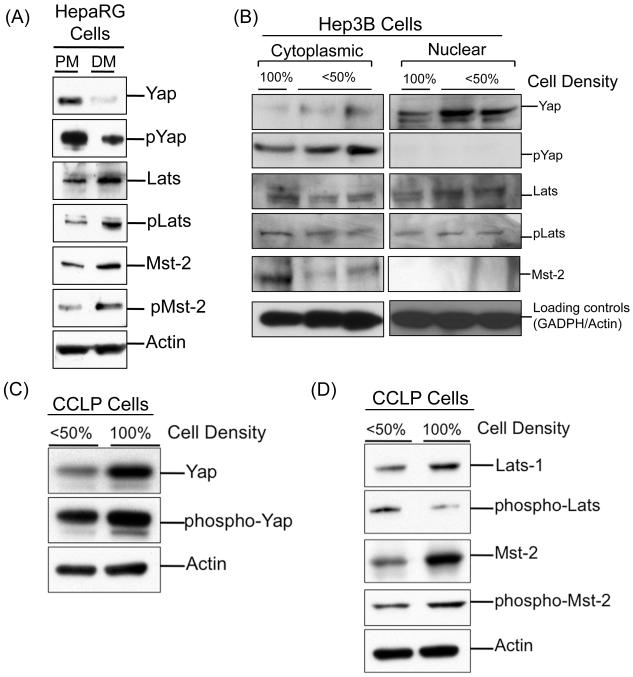

HCC and CC cells loose cell-cell contact dependent activation of Hippo Kinase Pathway

It is known that Hippo Kinase signaling is stimulated in the normal cells by cell-cell contact and results in inhibition of cell proliferation in response to increased cell density. Because human hepatocytes are unable to proliferate in culture, we used HepaRG cells as a control cell line. HepaRG is a human hepatocyte derived cell line, which can divide in culture upon growth factor stimulation, can be induced to differentiate and maintains hepatocyte differentiation program (14, 17, 18). We obtained total cell extracts from HepaRG cells maintained in a proliferation medium where these cells rapidly divide and cells maintained in differentiation medium where they do not divide and express markers of differentiated hepatocytes. Western blot analysis indicated extensive increase in total and phospho-Yap in HepaRG cells in proliferation medium, which decreased in cells in differentiation medium (Fig. 7A). The decrease in Yap activation in HepaRG cells in differentiation medium was accompanied by increased phosphorylation of Lats. We did not observe significant change in Mst-2 activation between HepaRG cells maintained in proliferation medium vs. differentiation medium. Taken together, these data indicate that the human hepatocyte derived HepaRG cells have an active Hippo Kinase signaling pathway, which responds to differentiation stimuli and cell density.

Fig. 7.

Loss of cell-cell contact-induced activation of Hippo Kinase pathway in HCC and CC. (A) Western blot analysis of Yap, phospho-Yap, Lats, phospho-Lats, Mst-2, and phopho-Mst-2 in RIPA extracts obtained from HepaRG cells treated with either proliferation media (PM) or differentiation media (DM). (B) Western blot analysis of Yap, phospho-Yap, Lats, phospho-Lats and Mst-2 in nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts of Hep3B cells grown at <50% density or 100% cell density. (C) Western blot analysis of Yap and phospho-Yap and (D) Lats, phospho-Lats, Mst and phospho-Mst using RIPA extracts of CCLP cells grown at <50% cell density and 100% cell density.

Next, we tested the ability of Hep3B and CCLP cells to initiate Hippo Kinase signaling in response to cell density. Hep3B cells grown at less than 50% cell density showed extensive Yap localization in the nuclear fraction and substantial phospho-Yap (inactive) protein in the cytoplasmic fraction (Fig. 7B). When cells were allowed to grow up to 100% confluency, a decline in both nuclear Yap and phospho-Yap was observed. However, Yap expression and activity was not completely inhibited at 100% cell density. Further analysis indicated significant amount of total Lats protein and active Lats protein (phospho-Lats) in the nuclear fraction in the cells grown at 50% cell density. In cells grown at 100% density, decrease in nuclear Lats protein expression and activity (as measured by phospho-Lats) was observed. We also observed a moderate increase in total and activate Lats in the cytoplasmic fraction of cells grown at 100% density. These data indicate that cell density-mediated inactivation of Yap does not occur efficiently in the HCC cells.

To determine if the cell density-mediated inactivation of Yap is observed in CC cells, CCLP cells were cultured at 50% or 100% cell density and the expression of Hippo Kinase components was determined by Western blot analysis. Interestingly, we observed extensive induction in Yap in CCLP cells grown at 100% density as compared to 50% density. Cell density had no significant effect on Yap inactivation as demonstrated by absence of a marked change in phospho-Yap levels (Fig. 7C). Western blot analysis showed an increase in total Lats protein at 100% density but a decrease in active (phosphorylated) Lats at 100% density. Interestingly, increased total and active (phospho) Mst-2 was observed in cells grown at 100% density (Fig. 7D). Taken together, these data indicate that CCLP cells have completely lost the density-dependent inhibition of Yap and that this effect may be due to inhibition of Lats but not Mst-2.

Discussion

HCC, HB and CC, the three major malignancies of the liver, are all extremely devastating diseases with grim prognosis, mainly due to limited treatment options (4, 19). Recent reports indicate that the incidence of all three hepatic malignancies is growing in the US and rest of the world (4). HCC constitutes more than 85% of the hepatic cancers and is the third leading cause of cancer related deaths worldwide (3). In spite of extensive investigations the mechanisms of HCC, CC and HB pathogenesis have remained elusive, hindering therapeutic development (20).

Recently, several studies have implicated Hippo Kinase signaling pathway in pathogenesis of HCC (8, 9, 13). In normal cells, Hippo Kinase pathway regulates organ size by limiting cellular proliferation (13). Animal studies performed using tissue specific gene targeting have shown that Hippo Kinase signaling is deregulated in cancers of many organs including breast, prostate and the liver (8). Other studies have put forth mechanisms involved in deregulation of Hippo Kinase pathway during cancer pathogenesis in animals (21-23). However, detailed clinical studies validating the mechanisms postulated in these animal studies are currently lacking. Whereas the role of Hippo Kinase pathway has been shown in HCC development, its role in pathogenesis of CC and HB is currently not known. The objective of our studies was to investigate the postulated deregulation of Hippo Kinase signaling in HCC and to determine whether Hippo Kinase pathway is dysfunctional in CC and HB using clinical samples.

Our studies demonstrate extensive activation of Yap, the downstream effector of the Hippo Kinase pathway, in HCC, CC and HB. We observed extensive nuclear localization of Yap in HCC, CC and HB tissues. We also observed decreased Yap phosphorylation, known to target Yap for degradation in the HCC cells and tissue. These data corroborate previous studies. Xu et al. have previously shown that Yap can be used as an independent prognostic marker for HCC and increased Yap levels correlate with decreased disease free survival (24). Consistent with this observation, we observed that Yap activation is associated with tumor aggressiveness and higher TNM grade. The majority of HCC and CC tissue with high nuclear Yap staining were of high grade (grade 2-3 poorly differentiated and aggressive tumors) and belonged to T2 or T3 in the TNM classification. We also observed increased expression of Yap target genes including Survivin, CTGF and Glypican 3. Taken together, our data indicate that Hippo Kinase dysfunction resulting in increased Yap activation is associated with aggressive and high grade HCC and CC.

We also stained a total of 22 HB tissue samples along with five adjacent normal tissues. Our data indicate that Yap is expressed in normal hepatocytes but is mainly cytoplasmic in localization. Biliary epithelial (BE) cells have higher Yap expression than hepatocytes and BE cells also exhibit nuclear staining in normal livers. This is consistent with the observation that Cytokaretin-19, the hallmark of BE cells, may be a downstream target of Yap. Our studies demonstrated that a large percentage of HB (73% in this study) have dysregulation of Hippo Kinase pathway as demonstrated by increased nuclear localization of Yap.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the upstream kinases, including Mst and Lats, are involved in Yap phosphorylation and degradation (25). Whole body Lats knockout mice are also known to develop soft tissue sarcomas, ovarian and pituitary tumors (26). Recent studies have shown that hepatocyte specific Mst knockout mice develop HCC (21, 23). However, these studies reported no change in Mst total or activate (phosphorylated) protein in human HCC samples. To determine the mechanism of Yap activation in HCC, we performed detailed Western blot analysis of all the Hippo Kinase pathway components including Yap, Lats, Mob, Mst-2, and Sav in seven HCC and seven unrelated normal samples. Our data indicate that Yap activation correlates with Lats inactivation. We did not observe any change in total or phosphorylated Mst-2 indicating that Mst-2 may not play a critical role in Yap inactivation and may be involved in tumor promotion via a separate pathway. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that Mst-1 dysfunction may be involved in Yap activation in HCC. Thus, our data indicate that Lats inactivation may be the primary mechanism behind Yap activation in HCC.

Hippo Kinase pathway is activated by cell-cell contact in normal cells (13). Our studies on HepaRG cells, a normal human hepatocyte cell line, indicate that normal hepatocytes exhibit active Hippo Kinase signaling pathway. HepaRG cells cultured in proliferation medium showed increased Yap expression, which reduced significantly when the cells were grown to confluency and cultured in a differentiation medium. To determine whether this cell-cell contact dependent activation of Hippo Kinase signaling is deregulated in hepatic malignancies, we determined Yap activation in Hep3B cells, a HCC cell line and CCLP cells, a CC cell line. Our data show that cell density-dependent activation of Hippo Kinase pathway is dysfunctional in HCC, CC and HB cells (HepG2 cells, data not shown). We observed significant nuclear localization of Yap and no change in phospho-Yap in Hep3B, CCLP and HepG2 cells grown at 100% cell density. This was associated with decreased Lats expression and activity. Interestingly, increased expression and activity of Mst-2 kinase was observed in cells grown to 100% cell density further indicting that Mst-2 may not be the primary regulator of Yap in HCC, CC and HB cells, and may function independently. These data further implicate Lats inactivation in increased Yap activation during HCC, CC and HB pathogenesis.

Taken together, our data provides evidence for Hippo Kinase pathway deregulation in three major hepatic malignancies including HCC, CC and HB. Our data suggests that Yap activation is associated with highly aggressive tumors. Further, our data indicate that Lats inactivation may be the primary mechanism behind Yap activation. The mechanism of Lats inactivation seems to be independent of Mst-2 inactivation because decreased Lats phosphorylation was observed in spite of significant Mst-2 activation in patient tissues and cell culture experiments. Thus, our studies provide additional evidence for role of the Hippo Kinase pathway in hepatic cancer pathogenesis and highlight Yap as a therapeutic target and prognostic marker in hepatic cancers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Supported by NIH - P20 RR021940 and American Cancer Society IRG grant.

Abbreviations

- Yap

yes-associated protein

- Lats

large tumor suppressor

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- CC

cholangiocarcinoma

- HB

hepatoblastoma

- CTGF

connective tissue growth factor

- BIRC5

baculoviral IAP repeat-containing 5

References

- 1.BUENDIA MA. Genetic alterations in hepatoblastoma and hepatocellular carcinoma: common and distinctive aspects. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2002;39(5):530–5. doi: 10.1002/mpo.10180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.BEFELER AS, DI BISCEGLIE AM. Hepatocellular carcinoma: diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(6):1609–19. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DI BISCEGLIE AM, BEFELER AS. Diagnostic and therapeutic approach to hepatocellular carcinoma in the USA. Hepatol Res. 2007;37(Suppl 2):S251–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC Hepatocellular carcinoma - United States, 2001-2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(17):517–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LITTEN JB, TOMLINSON GE. Liver tumors in children. Oncologist. 2008;13(7):812–20. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MCGLYNN KA, TARONE RE, EL-SERAG HB. A comparison of trends in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(6):1198–203. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LLOVET JM, BRUIX J. Molecular targeted therapies in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2008;48(4):1312–27. doi: 10.1002/hep.22506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ZHAO B, LEI QY, GUAN KL. The Hippo-YAP pathway: new connections between regulation of organ size and cancer. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20(6):638–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.PAN D. Hippo signaling in organ size control. Genes Dev. 2007;21(8):886–97. doi: 10.1101/gad.1536007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ZHAO B, WEI X, LI W, et al. Inactivation of YAP oncoprotein by the Hippo pathway is involved in cell contact inhibition and tissue growth control. Genes Dev. 2007;21(21):2747–61. doi: 10.1101/gad.1602907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LAM-HIMLIN DM, DANIELS JA, GAYYED MF, et al. The hippo pathway in human upper gastrointestinal dysplasia and carcinoma: a novel oncogenic pathway. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2006;37(4):103–9. doi: 10.1007/s12029-007-0010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DONG J, FELDMANN G, HUANG J, et al. Elucidation of a universal size-control mechanism in Drosophila and mammals. Cell. 2007;130(6):1120–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.PAN D. The hippo signaling pathway in development and cancer. Dev Cell. 2010;19(4):491–505. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.HART SN, LI Y, NAKAMOTO K, SUBILEAU EA, STEEN D, ZHONG XB. A comparison of whole genome gene expression profiles of HepaRG cells and HepG2 cells to primary human hepatocytes and human liver tissues. Drug Metab Dispos. 38(6):988–94. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.031831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ZENG G, APTE U, CIEPLY B, SINGH S, MONGA SP. siRNA-mediated beta-catenin knockdown in human hepatoma cells results in decreased growth and survival. Neoplasia. 2007;9(11):951–9. doi: 10.1593/neo.07469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.APTE U, ZENG G, MULLER P, et al. Activation of Wnt/beta-catenin pathway during hepatocyte growth factor-induced hepatomegaly in mice. Hepatology. 2006;44(4):992–1002. doi: 10.1002/hep.21317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MCGILL MR, YAN HM, RAMACHANDRAN A, MURRAY GJ, ROLLINS DE, JAESCHKE H. HepaRG cells: a human model to study mechanisms of acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Hepatology. 2011;53(3):974–82. doi: 10.1002/hep.24132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DARNELL M, SCHREITER T, ZEILINGER K, et al. Cytochrome P450-Dependent Metabolism in HepaRG Cells Cultured in a Dynamic Three-Dimensional Bioreactor. Drug Metab Dispos. 2011;39(7):1131–8. doi: 10.1124/dmd.110.037721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LLOVET JM, BRUIX J. Novel advancements in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma in 2008. J Hepatol. 2008;48(Suppl 1):S20–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ARAVALLI RN, STEER CJ, CRESSMAN EN. Molecular mechanisms of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2008;48(6):2047–63. doi: 10.1002/hep.22580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LU L, LI Y, KIM SM, et al. Hippo signaling is a potent in vivo growth and tumor suppressor pathway in the mammalian liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(4):1437–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911427107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ZHANG N, BAI H, DAVID KK, et al. The Merlin/NF2 tumor suppressor functions through the YAP oncoprotein to regulate tissue homeostasis in mammals. Dev Cell. 2010;19(1):27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LEE KP, LEE JH, KIM TS, et al. The Hippo-Salvador pathway restrains hepatic oval cell proliferation, liver size, and liver tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(18):8248–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912203107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.XU MZ, YAO TJ, LEE NP, et al. Yes-associated protein is an independent prognostic marker in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2009;115(19):4576–85. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.HUANG J, WU S, BARRERA J, MATTHEWS K, PAN D. The Hippo signaling pathway coordinately regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis by inactivating Yorkie, the Drosophila Homolog of YAP. Cell. 2005;122(3):421–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.ST JOHN MA, TAO W, FEI X, et al. Mice deficient of Lats1 develop soft-tissue sarcomas, ovarian tumours and pituitary dysfunction. Nat Genet. 1999;21(2):182–6. doi: 10.1038/5965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.