Abstract

Objective

Microvascular malperfusion after myocardial infarction leads to infarct expansion, adverse remodeling, and functional impairment. Native reparative mechanisms exist but are inadequate to vascularize ischemic myocardium. We hypothesized that a 3-dimensional human fibroblast culture (3DFC) functions as a sustained source of angiogenic cytokines, thereby augmenting native angiogenesis and limiting adverse effects of myocardial ischemia.

Methods

Lewis rats underwent ligation of the left anterior descending coronary artery to induce heart failure; experimental animals received a 3DFC scaffold to the ischemic region. Border-zone tissue was analyzed for the presence of human fibroblast surface protein, vascular endothelial growth factor, and hepatocyte growth factor. Cardiac function was assessed with echocardiography and pressure–volume conductance. Hearts underwent immunohistochemical analysis of angiogenesis by co-localization of platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule and alpha smooth muscle actin and by digital analysis of ventricular geometry. Microvascular angiography was performed with fluorescein-labeled lectin to assess perfusion.

Results

Immunoblotting confirmed the presence of human fibroblast surface protein in rats receiving 3DFC, indicating survival of transplanted cells. Increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and hepatocyte growth factor in experimental rats confirmed elution by the 3DFC. Microvasculature expressing platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule/alpha smooth muscle actin was increased in infarct and border-zone regions of rats receiving 3DFC. Microvascular perfusion was also improved in infarct and border-zone regions in these rats. Rats receiving 3DFC had increased wall thickness, smaller infarct area, and smaller infarct fraction. Echocardiography and pressure–volume measurements showed that cardiac function was preserved in these rats.

Conclusions

Application of a bioengineered 3DFC augments native angiogenesis through delivery of angiogenic cytokines to ischemic myocardium. This yields improved microvascular perfusion, limits infarct progression and adverse remodeling, and improves ventricular function.

Ischemic cardiovascular disease is an increasingly prevalent global health concern. Traditionally, patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy are treated with either percutaneous coronary intervention or bypass surgery. However, a significant proportion of patients do not have anatomically correctable coronary disease. Additionally, conventional revascularization methods do not adequately address the microvascular destruction that accompanies a significant ischemic myocardial injury.1–4 These factors have driven investigators to develop novel revascularization techniques that specifically target the microvasculature in ischemic myocardium.5–7

Induction of microvascular angiogenesis by angiogenic growth factors has been studied as one such approach. Vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs) are potent inducers of vascular growth and have been shown to produce transmural angiogenesis and improve myocardial perfusion.8–10 Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) likewise enhances myocardial angiogenesis, limits apoptosis, and improves postinfarct cardiac function.11–13

Despite these promising results, optimal delivery of angiogenic growth factors remains problematic. Systemic or intracoronary delivery, while preferable owing to ease of use and clinical applicability, does not achieve adequate concentrations in the myocardium to maximize efficacy. Therefore, local delivery is desired to maximize effect.14 Although recombinant proteins have a good safety profile, delivery via either direct myocardial injection or percutaneous catheter-based injection is confined to a single administration, temporally limiting the effects. Alternatively, viral gene transfer may achieve greater efficacy but is hampered by immune factors that may cause toxicity and diminished transgene expression.15 The ideal delivery vehicle would achieve sustained growth factor expression in the zone of interest with limited toxicity.

Although a bioengineered sustained delivery mechanism is appealing, perhaps the ideal method of achieving prolonged local expression of angiogenic growth factors is recruitment or transplantation of fibroblasts. As a key mediator of wound healing and angiogenesis, fibroblasts are a robust source of VEGF and HGF, as well as other known and unknown factors. Additionally, a cellular source is more likely than a bioengineered delivery system to secrete the precise concentrations of growth factors required for an optimal angiogenic response. Because multiple investigators have shown that direct myocardial injection of cells results in poor cell survival,16–19 and studies show that cell-seeded biocompatible sheets result in improved cell engraftment, 20,21 the current study uses a tissue-engineered, 3-dimensional human dermal fibroblast culture (3DFC) scaffold as a sustained local source of angiogenic growth factors. A similar 3DFC (Dermagraft; Advanced BioHealing, Inc, La Jolla, Calif) is approved by the Food and Drug Administration in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers and is a safe, effective method of improving ulcer closure.22 Our 3DFC, composed of structural extracellular matrix proteins and human dermal fibroblasts, currently marketed as Anginera (Theregen, Inc, San Francisco, Calif), is being studied as an angiogenic therapy for myocardial ischemia. Two previous studies have shown that the 3DFC supports myocardial angiogenesis and attenuates reduction in cardiac function in a severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mouse model of ischemic cardiomyopathy.23,24

The purpose of this study is to examine in depth the angiogenic mechanisms of the 3DFC. It is hypothesized that the 3DFC serves as a sustained local source of VEGF and HGF to support angiogenesis after ischemic myocardial injury. It is further hypothesized that enhanced microvascular perfusion results in diminished adverse ventricular remodeling and cardiac functional loss in a rat model of ischemic cardiomyopathy.

METHODS

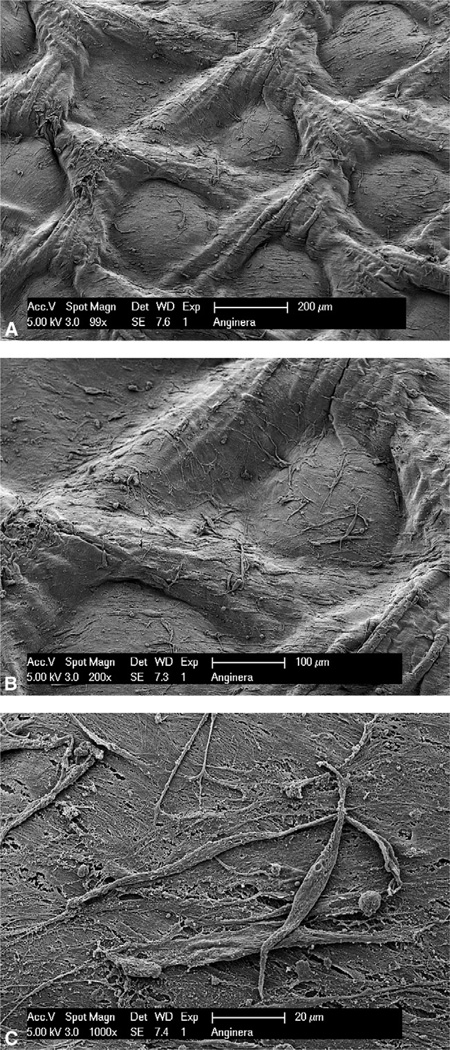

The 3DFC (Figure 1), composed of fibroblasts cultured on pieces of polyglycolic acid mesh, was stored at −80°C and then rapidly thawed, rinsed, and used immediately according to the previously published protocol.25

FIGURE 1.

Scanning electron microscopy images of the 3-dimensional fibroblast culture (3DFC). The 3DFC consists of a bioabsorbable scaffold, extracellular matrix proteins, and viable human dermal fibroblasts. A, 99×; B, 200×; C, 1000×.

In Vitro Growth Factor Expression

A portion of 3DFC was cultured in endothelial basal medium-2 (Lonza Walkersville, Inc, Walkersville, Md), free of growth factors and supplements. A time course of growth factor expression by the 3DFC was generated. Media samples were collected at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 10, and 24 hours after culture and analyzed via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for human VEGF-A (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn) and human HGF (R&D Systems). Media-only samples served as a control.

Animal Care and Biosafety

Male Lewis rats weighing 250 to 300 g were obtained from Charles River (Boston, Mass). Food and water were provided ad libitum. This study was performed in accordance with the standard humane care guidelines of the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” and the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee of the University of Pennsylvania.

Ischemic Cardiomyopathy Model

Per a previously published protocol,26 rats were anesthetized with ketamine (75 mg/kg) and xylazine (7.5 mg/kg), intubated with a 16-gauge catheter, and mechanically ventilated (Hallowell EMC, Pittsfield, Mass) with a tidal volume (mL) = 6.2 × M1.01 (M = animal mass, kg) and respiratory rate (min−1) = 53.5 × M−0.26. A thoracotomy was performed in the left fourth intercostal space. A 7-0 polypropylene suture was placed around the mid–left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) and ligated to produce a large anterolateral myocardial infarction of 30%of the left ventricle. The extent of infarction is highly reproducible in our hands and cardiomyopathy has been well documented.11,27–29 In experimental animals, a 3DFC scaffold (0.75 × 0.75 cm2) was sutured to the ischemic area. Control animals received a similar array of sutures with no scaffold. Notably, the two previous SCID mouse 3DFC studies showed no significant angiogenic response in animals treated with an acellular scaffold, suggesting that the angiogenic response results entirely from the cellular component of the 3DFC.23,24 A fibroblast implantation control group was not used because the poor survivability of therapeutic cells when directly injected into ischemic myocardium would render this an inadequate control population.16–19 The thoracotomy was closed and animals were implanted with identification microchips (BioMedic Data Systems Inc, Seaford, Del) and allowed to recover. Identification data were maintained by an investigator who did not participate in subsequent data collection or analysis. Four weeks following LAD ligation, animals underwent the following experiments.

Determination of Human Fibroblast Cell Fate

To determine the presence of transplanted fibroblast components, we explanted hearts from a subset of animals (control, n = 4; experimental, n = 4) 4 weeks after LAD ligation. Myocardial tissue biopsy specimens were taken from the ischemic zone, including the scaffold in 3DFC animals. Samples were homogenized in T-Per Tissue Extraction Reagent (Thermo-Fischer, Rockford, Ill), normalized for total protein content via Quick Start Bradford Protein Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif), and tested for the presence of human fibroblast surface protein (HFSP). Immunoblotting was performed with a mouse antibody directed against HFSP (1:300; Abcam, Cambridge, Mass), and sheep anti-mouse secondary antibodies (1:100,000; GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). Detection was performed with SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, Ill).

In Vivo Growth Factor Expression/Mechanism of Action

We assayed for the presence of human VEGF-A and human HGF by immunoblotting to determine in vivo expression of angiogenic growth factors after 3DFC implantation (control, n = 4; experimental, n = 4). Myocardial tissue biopsy specimens were processed as described earlier, and immunoblotting was performed with a mouse antibody directed against human VEGF-A (1:750, Abcam) and a rabbit antibody directed against human HGF (1:1000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, Calif). Secondary antibodies were sheep anti-mouse (1:40,000, GE Healthcare) and donkey antirabbit (1:30,000, GE Healthcare). Detection was performed as described earlier.

Assessment of Microvascular Density

Microvascular angiogenesis was assessed in the ischemic zone (control, n = 10; experimental, n = 9). Explanted hearts were distended with OCT compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, Calif), submerged in an OCT-filled reservoir, frozen, and stored at −80°C. Transverse 10-mm sections were prepared through the infarct level and co-stained with antibodies directed against platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM) and alpha smooth muscle actin (α-SMA). Sections were incubated with mouse anti- PECAM (1:500; BD Biosciences, San Jose, Calif) and rabbit anti-α-SMA (1:500, Abcam) for 1 hour. Sections were then washed and incubated with Alexa Fluor 555 donkey anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (1:500, Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, Calif) and Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (1:500, Invitrogen) for 1 hour. Slides were washed and mounted with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Inc, Burlingame, Calif). Quantitative analysis of vessels co-staining for PECAM and α-SMA was conducted with 40× fluorescent microscopy in the infarct zone, peri-infarct border zone, and remote myocardium. Counts were conducted in a group-blinded fashion in 4 fields per specimen for each of the three zones and averaged.

Assessment of Microvascular Perfusion With Lectin Angiography

To ensure that newly formed microvessels were functionally perfused, we subjected a subset of animals (control, n =3; experimental, n =3) to lectin microvascular angiography. We injected 500 µg/kg of fluorescein-labeled Lycopersicon esculentum (tomato) lectin (Vector Laboratories) into the inferior vena cava and allowed it to circulate with a beating heart for 5 minutes. Direct contact of lectin with endothelial cells is required for binding to the surface N-acetylglucosamine oligomers of endothelial cells, so only perfused vessels are labeled.30 After lectin perfusion, hearts were explanted. Image stacks were obtained with scanning laser confocal microscopy through 100-µm thick myocardial sections of infarct, border zone, and remote myocardial regions. Three-dimensional reconstructions of the Z-stacks were created with Volocity Software version 3.61 (Improvision Inc, Waltham, Mass). Fluorescein-labeled voxels were quantified as a percentage of total tissue section voxels, creating a quantifiable measurement of perfusion per unit of myocardial tissue volume.

Infarct Size and Ventricular Geometry Analysis

After myocardial functional analysis described below, hearts were explanted (control, n =10; experimental, n =9). The left ventricle was filled with OCT through the aorta at a pressure of 80 mm Hg, and the heart was submerged in OCT, frozen, and stored at −80°C. Sections (10 µm) from midway between the apex and point of ligation were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Measurements were performed on digitized photomicrographs of the sections using Adobe Photoshop CS3 Extended version 10.0 image processing software (Adobe Systems Inc, San Jose, Calif) with a standard of known length and were obtained on two sections for each animal. Left ventricular internal diameter (LVID), border-zone wall thickness, infarct area, and cross-sectional area of the entire heart were recorded for each of the sections.

Echocardiographic Assessment of Left Ventricular (LV) Geometry and Function

Left ventricular (LV) geometry and function were evaluated by transthoracic echocardiography using a Phillips Sonos 5500 revD system (Phillips Medical Systems NA, Bothwell, Wash) with a 12-MHz transducer at an image depth of 2 cm. Rats (control, n =20; experimental, n =17) were anesthetized and placed in the dorsal recumbency position. Left parasternal LV short axis 2-D and M-mode images were used to define LV free wall thickness and LVID during systole and diastole. LV end-systolic diameter (LVIDs) and end-diastolic diameter (LVIDd) were used to derive end-diastolic volume (EDV, 1.047 × LVIDd3), end-systolic volume (ESV, 1.047 × LVIDs3), fractional shortening ([(LVIDd − LVIDs)/LVIDd] × 100), stroke volume (EDV−ESV), and ejection fraction (stroke volume/EDV × 100).31

Invasive Hemodynamic Assessment

Eleven control and 8 experimental animals underwent invasive hemodynamic measurements with a pressure–volume conductance catheter (SPR- 869; Millar Instruments, Inc, Houston, Tex). The catheter was calibrated via 5-point cuvette linear interpolation with parallel conductance subtraction by the hypertonic saline method.26 Rats were anesthetized and the catheter was introduced into the left ventricle with a closed-chest approach via the right carotid artery. Measurements were obtained before and during inferior vena cava occlusion to produce static and dynamic pressure–volume loops under varying load conditions. Data were recorded and analyzed with LabChart version 6 software (AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, Colo) and ARIA Pressure Volume Analysis software (Millar Instruments).

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed in a blinded fashion. The unpaired Student t test was used to compare groups. Values are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean.

RESULTS

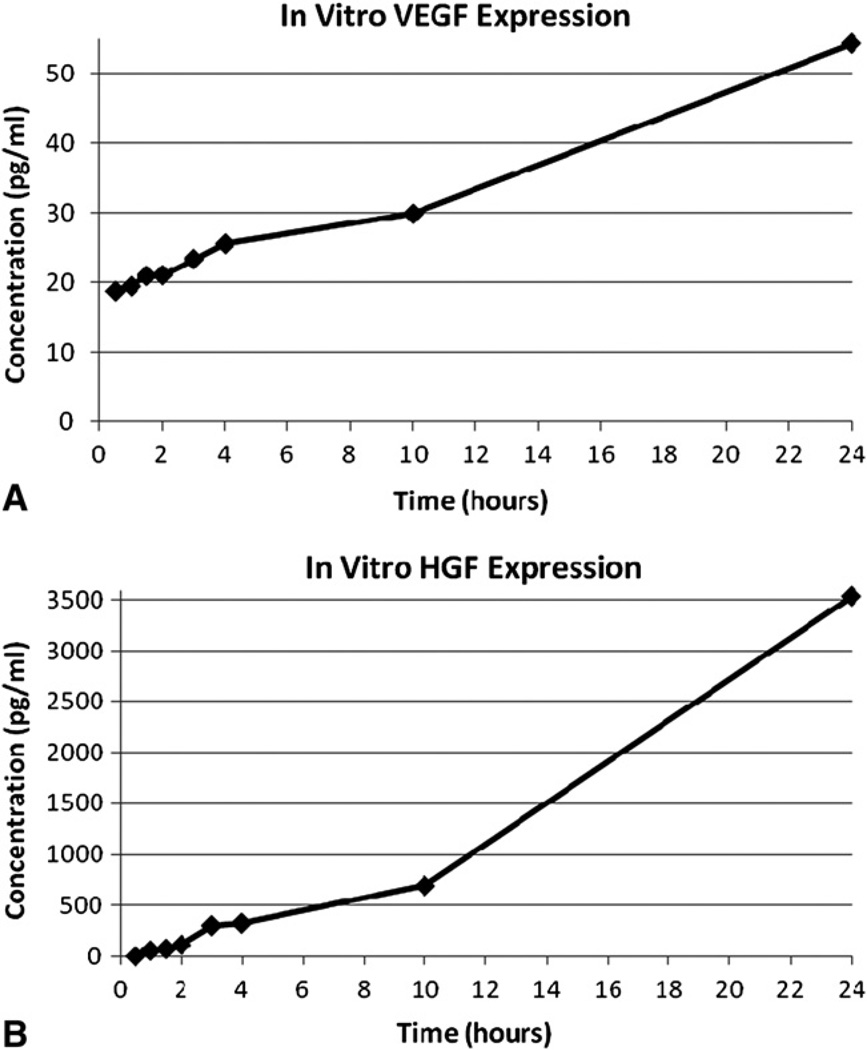

In Vitro Growth Factor Expression

VEGF-A concentrations in the growth medium at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 10, and 24 hours were 18.8, 19.5, 21.0, 21.1, 23.4, 25.6, 29.9, and 54.3 pg/mL, respectively. HGF (undetectable, 57, 73, 113, 301, 325, 693, and 3533 pg/mL) expression followed a similar pattern (Figure 2). Media-only control samples demonstrated undetectable levels of VEGF-A and HGF at all time points. This validated the expression of the angiogenic growth factors by the 3DFC.

FIGURE 2.

A, In vitro VEGF-A concentration steadily increased over 24 hours of 3DFC culture. B, In vitro HGF concentration followed a similar pattern. VEGF, Vascular endothelial growth factor; HGF, hepatocyte growth factor.

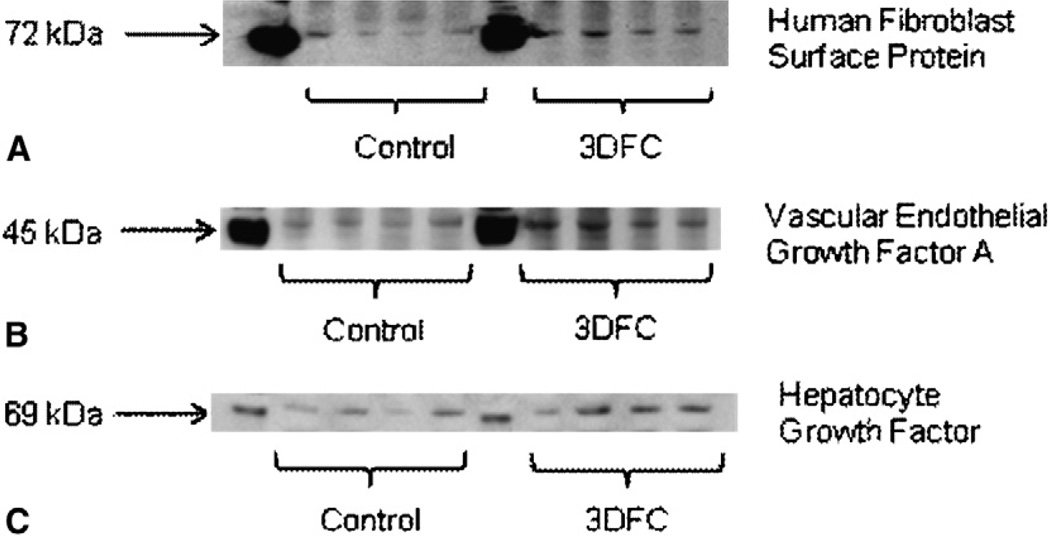

Determination of Human Fibroblast Cell Fate

HFSP is present on the surface of human fibroblasts, and antibodies directed against HFSP show minimal cross-reactivity in rats. Therefore, immunoblotting for HFSP allowed us to qualitatively assess presence of transplanted human fibroblast components in the 3DFC group. Figure 3, A, shows expression of HFSP in control and 3DFC animals. Quantitative analysis demonstrated a twofold increase in HFSP staining among 3DFC animals (57.8 ± 7.4 intensity units [IU]) compared with controls (28.1 ± 9.0 IU; P = .022). These data suggest that fractions of the transplanted fibroblasts survived.

FIGURE 3.

A, Immunoblotting directed against human fibroblast surface protein 4 weeks after 3DFC scaffold implantation provides evidence of human fibroblast survival in experimental animals. B, Experimental animals exhibited statistically significant upregulation in vascular endothelial growth factor A expression 4 weeks after 3DFC implantation. C, 3DFC-treated animals also exhibited increase hepatocyte growth factor expression at 4 weeks. 3DFC, 3-dimensional human dermal fibroblast culture.

In Vivo Growth Factor Expression/Mechanism of Action

Immunoblotting revealed a statistically significant increase in VEGF-A and HGF expression in 3DFC animals (VEGF-A, 30.1 ± 1.4 IU; HGF, 42.7 ± 6.0 IU) versus controls (VEGF-A, 18.2 ± 1.5 IU; P < .001; HGF, 28.2 ± 4.0 IU; P = .049). Immunoblots are shown in Figure 3, B (VEGF-A) and 3, C (HGF). These experiments suggest that the 3DFC may continue to elute angiogenic growth factors after implantation.

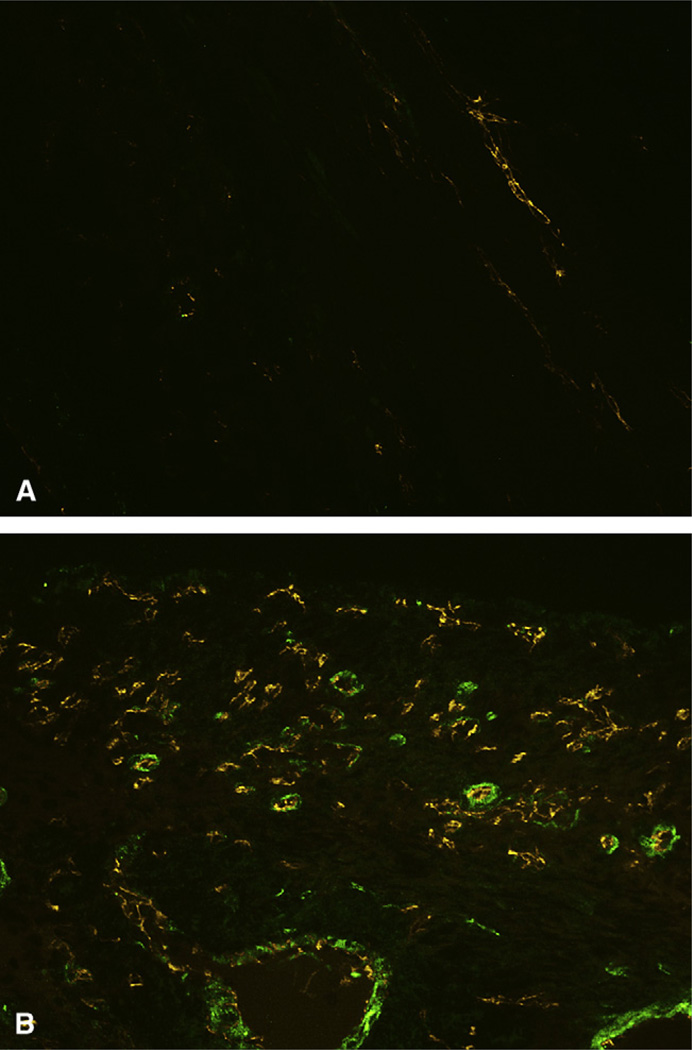

Microvascular Angiogenesis Is Increased After 3DFC Treatment

Analysis of immunofluorescent co-expression of PECAM and α-SMA (Figure 4) revealed a significant increase in blood vessel density in the infarct and border-zone regions of 3DFC animals (infarct, 8.8 ± 0.6 vessels/high-power field [hpf]; border zone, 8.4 ± 0.4 vessels/hpf) compared with controls (infarct, 1.8 ± 0.3 vessels/hpf; P < .001; border zone, 1.8 ± 0.1 vessels/hpf; P <.001). Vessel density in remote myocardium was equivalent between 3DFC (8.4 ± 0.3 vessels/hpf) and control animals (9.3 ± 0.7 vessels/hpf; P >.2).

FIGURE 4.

Representative images of myocardial sections depicting platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM, orange) and alpha smooth muscle actin (α-SMA, green) in control (A) and 3DFC-treated hearts (B).

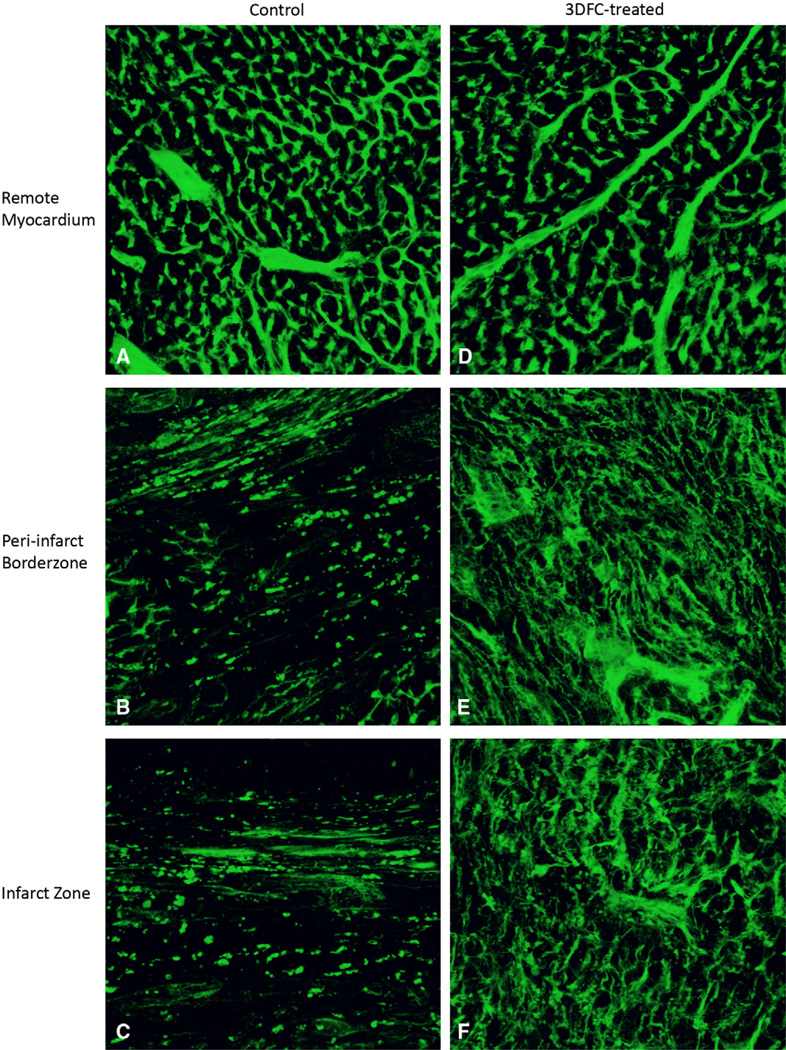

Augmentation of Microvascular Perfusion After 3DFC Treatment

Remote myocardial perfusion was equivalent between 3DFC and control groups (1.9% ± 0.3%vessel volume/tissue volume versus 2.7% ± 0.4%; P >.2). This served as an internal control, validating the assay and demonstrating similar baseline perfusion in the two groups. Qualitative analysis revealed increased perfusion among 3DFC animals in infarct and border-zone regions (Figure 5). Quantitative analysis demonstrated significantly enhanced perfusion in the ischemic areas in 3DFC (infarct, 1.6% ± 0.2%; border zone, 2.3% ± 0.4%) compared with control animals (infarct, 0.4% ± 0.1%; P = .005; border zone, 0.7% ± 0.2%; P = .041). In addition to demonstrating improved microvascular perfusion of the ischemic zones after 3DFC treatment, these data confirm the increase in vasculature that was noted with PECAM/α-SMA vascular labeling.

FIGURE 5.

After perfusion with lectin, 3-dimensional image stacks were obtained with confocal microscopy of control, remote myocardium (A), control, peri-infarct border-zone myocardium (B), control, infarct myocardium (C), 3DFC-treated, remote myocardium (D), 3DFC-treated, peri-infarct border-zone myocardium (E), and 3DFC-treated, infarct myocardium (F).

Adverse Ventricular Remodeling Is Diminished After 3DFC Treatment

Infarct area and infarct fraction were significantly smaller in 3DFC animals (area, 4.38 ± 0.55 mm2; fraction, 8.07% ± 1.34%) versus controls (area, 8.64 ± 0.87 mm2; P = .001; fraction, 15.76% ±1.09%; P <.001). A marked increase in border-zone wall thickness was also observed in the 3DFC group (3DFC, 1.53 ± 0.11 mm; control, 1.07 ± 0.08 mm; P = .004). A trend toward smaller LVID among the 3DFC group was also noted (3DFC, 8.49 ± 1.34 mm; control, 9.74 ± 0.29 mm; P = .103).

Echocardiographic Assessment of LV Function and Geometry

Echocardiographic assessment of cardiac structure and function demonstrated significant benefits in the 3DFC group versus the control group (Table 1, part A). Among 3DFC animals, LVID was smaller in both systole and diastole, whereas LV free wall thickness was greater. This provides clear evidence that adverse ventricular remodeling is diminished after treatment with the 3DFC. Additionally, fractional shortening and LV ejection fraction were significantly improved in 3DFC animals.

TABLE 1.

Hemodynamic parameters of LV function and geometry 4 weeks after left anterior descending coronary artery ligation among control and 3DFC-treated animals

| Control | 3DFC | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Echocardiography (control, n = 20; 3DFC, n = 17) | |||

| LV internal diameter diastole (cm) | 0.770 ± 0.026 | 0.689 ± 0.025 | .030 |

| LV free wall thickness diastole (cm) | 0.107± 0.006 | 0.160 ± 0.013 | .001 |

| LV internal diameter systole (cm) | 0.638 ± 0.030 | 0.497 ± 0.024 | .001 |

| LV free wall thickness systole (cm) | 0.107 ± 0.007 | 0.181 ± 0.017 | .001 |

| Fractional shortening (%) | 18 ± 2 | 28 ± 1 | <.001 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 44 ± 3 | 63 ± 2 | <.001 |

| B. Pressure–volume conductance catheter (control, n = 11; 3DFC, n = 8) | |||

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 210 ± 5 | 222 ± 15 | >.2 |

| End-diastolic volume (µL) | 160.50 ± 11.0 | 130.99 ± 11.85 | .010 |

| End-systolic volume (µL) | 119.39 ± 9.95 | 82.47 ± 11.32 | .002 |

| End-diastolic pressure (mm Hg) | 13.55 ± 1.02 | 16.66 ± 2.34 | .053 |

| End-systolic pressure (mm Hg) | 91.26 ± 2.33 | 106.30 ± 5.01 | .001 |

| dP/dt max (mmHg/s) | 4238 ± 234 | 5726 ± 249 | <.001 |

| Pressure @ dP/dt max (mm Hg) | 63.87 ± 1.81 | 75.31 ± 4.77 | .003 |

| Volume @ dP/dt max (µL) | 164.33 ± 11.67 | 125.81 ± 13.28 | .004 |

| Preload-adjusted maximal power (mW/µL2) | 13.78 ± 1.56 | 17.48 ± 4.27 | .052 |

| Slope of end-systolic pressure–volume relationship | 0.749 ± 0.137 | 2.250 ± 0.561 | .005 |

Values were obtained using echocardiography and an intraventricular pressure–volume conductance catheter, as indicated. Values are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. LV, Left ventricular; 3DFC, 3-dimensional human dermal fibroblast culture; dP/dt max, maximum rate of pressure rise.

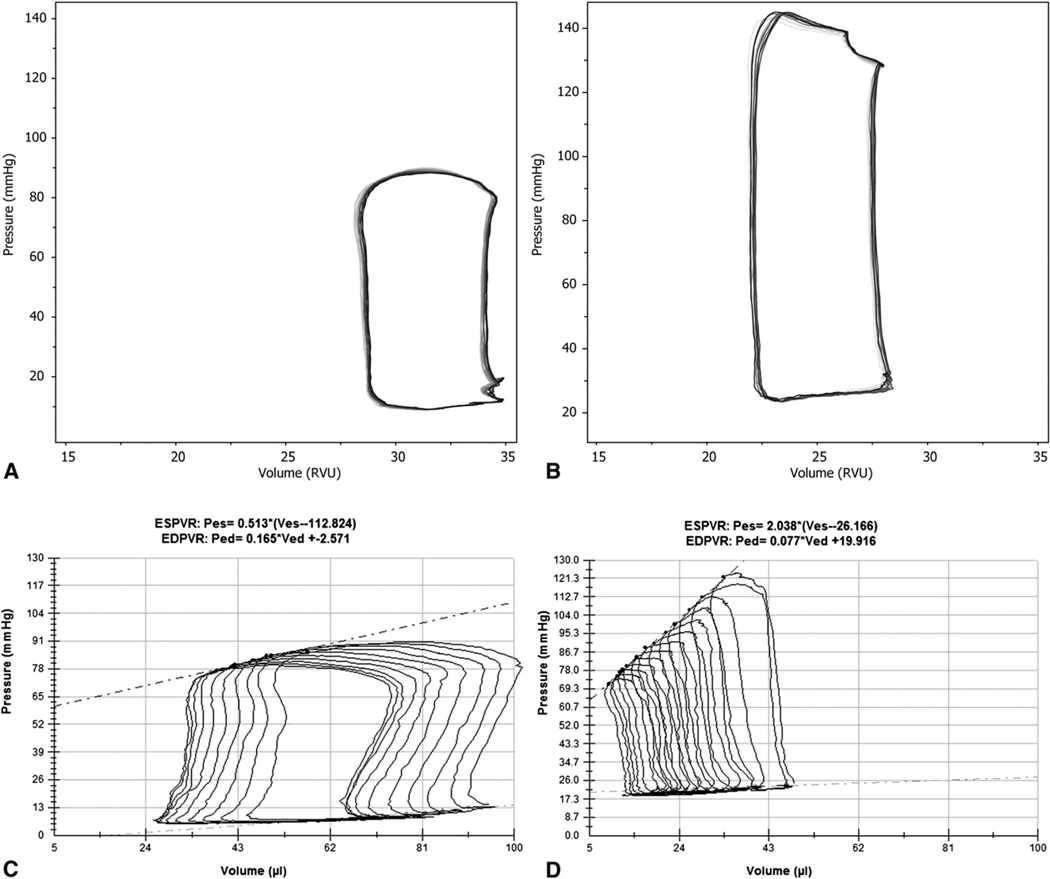

Invasive Hemodynamic Assessment

The 3DFC animals had statistically significant preservation of cardiac function compared with controls (Table 1, part B). The 3DFC group had improved EDV, ESV, end-diastolic and end-systolic pressures, maximum rate of pressure rise (dP/dt max), and preload adjusted maximal power. 3DFC animals also had improved contractility, indicated by an increased slope of the end-systolic pressure–volume relationship. Representative pressure–volume loops are shown in Figure 6.

FIGURE 6.

Representative pressure–volume loops obtained during steady state measurements from control (A) and 3DFC-treated animals (B). Representative pressure–volume loops obtained during inferior vena caval occlusion from control (C) and 3DFC-treated animals (D).

DISCUSSION

The prevalence and severity of ischemic cardiomyopathy, combined with the moderate success of conventional revascularization therapies, have prompted the development of novel techniques specifically targeting the microvasculature in ischemic myocardium. This study demonstrates the ability of a scaffold-based 3DFC to stimulate angiogenesis within an area of myocardial ischemic injury. The angiogenic response induced by the 3DFC resulted in improved microvascular perfusion, which diminished adverse ventricular remodeling and preserved myocardial function.

Preclinical studies of angiogenic growth factor therapy have given significant insight into the biology of these agents and have shown success in treating both peripheral and cardiac ischemia.27,32–34 Although the results of randomized controlled clinical trials are mixed, the potential for clinical success remains.32–34 The current study and previous studies with the 3DFC are unique compared with other angiogenic growth factor studies in that they use multiple factors simultaneously expressed by a cellular source.23,24

Previous myocardial angiogenesis studies with the 3DFC have used an SCID mouse model of ischemic cardiomyopathy to avoid immunologic tissue rejection by the host toward the human cells.23,24 By contrast, our study uses a model of ischemic cardiomyopathy in immunocompetent rats. Our successful use of the 3DFC in immunocompetent hosts establishes the 3DFC as a potentially translatable therapy in recipients with normal immune function. Additionally, the success of the 3DFC in healing chronic diabetic foot wounds in patients with normal immune function further supports the claim that this therapy will be clinically translatable.

A related study has recently been published by Thai and associates,35 which concluded that the 3DFC improved LV function and blood flow after myocardial infarction in immunocompetent rats. Although this work is promising, our study builds on these findings. First, because both articles represent the first reports of this 3DFC in the treatment of myocardial ischemia in immune-competent hosts, we believe it is important to prove that the 3DFC fibroblasts show evidence of survival and function after xenotransplantation. Additionally, invasive hemodynamic measurements in our study showed improvements in EDV, ESV, EDP, ESP, dP/dt max, pressure at dP/dt max, volume at dP/dt max, preload-adjusted maximal power, and the slope of the endsystolic pressure–volume relationship.

In our study, the 3DFC was proven to elute VEGF-A and HGF in vitro. After application of the 3DFC to a region of myocardial ischemia, fibroblasts showed evidence of survival up to 4 weeks, and the cells expressed these factors at a higher level than control animals during this time period. Sustained local delivery of VEGF-A and HGF led to significant upregulation of microvascular angiogenesis in the ischemic zones of the myocardium, evidenced by increased density of vessels co-staining for PECAM and α-SMA. The presence of α-SMA, a marker of pericyte presence in the vessel wall, establishes that the new microvasculature has achieved maturity. Additionally, lectin microvascular angiograms demonstrated that the newly formed microvascular networks are functionally perfused. Improved microvascular perfusion was demonstrated in both infarct and border-zone regions.

Because adverse ventricular remodeling and LV functional loss are due to malperfusion that accompanies significant ischemic injury, it is expected that activation of angiogenesis and improved microvascular perfusion will limit adverse ventricular remodeling and preserve LV function. This study confirmed that expectation when LV geometry and function were analyzed via multiple modalities, including digital planimetric analysis of myocardial sections, echocardiography, and invasive pressure–volume measurements. It is notable that the two previous SCID mouse studies found no improvement in ventricular geometry or function among animals treated with an acellular scaffold, suggesting that these benefits result from angiogenesis and enhanced perfusion, rather than the scaffold itself.23,24

In addition to sustained delivery of angiogenic cytokines, multiple other factors may be responsible for the success of the 3DFC in inducing angiogenesis. For example, most experimental angiogenic therapies are focused on modulating the ischemic border zone. However, in this study the therapeutic 3DFC is applied to the entire ischemic zone, which may prompt a more robust angiogenic response. Additionally, as one of the key cellular components in wound healing, fibroblasts may be ideally suited to adapt to the ischemic milieu of the infarct, secreting known and unknown angiogenic stimulants in physiologic concentrations to optimize angiogenesis. It will be important to address these questions in subsequent studies as Anginera transitions into the clinical domain. Future investigations should also elucidate the specific angiogenic and anti-apoptotic pathways stimulated by the 3DFC and determine whether a higher dose of fibroblasts, and therefore a higher dose of angiogenic cytokines, results in improved angiogenesis.

Limitations

There are multiple potential limitations to this study. First, the study was not designed to evaluate whether the polyglycolic acid mesh contributed to the survival and function of the transplanted fibroblasts. Therefore, it is not possible to assess whether the 3DFC represents an improvement over direct cell transplantation with other cell types that have been previously studied by other investigators. Further, this study did not evaluate the use of a polyglycolic acid mesh without cells as an additional control group. Finally, the lectin studies evaluated microvascular perfusion. They did not specifically evaluate perfusion of the individual cardiomyocytes.

CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrates the ability of a tissue-engineered 3-dimensional fibroblast scaffold to stimulate angiogenesis, improve microvascular perfusion, limit adverse ventricular remodeling, and preserve ventricular function in ischemic myocardium through sustained local delivery of angiogenic growth factors. Therefore, it may, in the future, play a role in the treatment of ischemic heart disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH R01 HL072812 (to Y.J.W.), NIH/TSFRE K08 HL072812 (to Y.J.W.), an ISHLT Research Fellowship Grant (to J.R.F. III), and NIH HL07843 (to J.R.F.).

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- α-SMA

alpha smooth muscle actin

- 3DFC

3-dimensional human dermal fibroblast culture

- dP/dt max

maximum rate of pressure rise

- EDV

end-diastolic volume

- ESV

end-systolic volume

- HFSP

human fibroblast surface protein

- HGF

hepatocyte growth factor

- IU

intensity units

- LAD

left anterior descending coronary artery

- LV

left ventricular

- LVID

left ventricular internal diameter

- LVIDd

left ventricular end-diastolic diameter

- LVIDs

left ventricular end-systolic diameter

- PECAM

platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule

- SCID

severe combined immunodeficient

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

Winner of the C. Walton Lillehei Resident Forum at the 89th Annual Meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, May 10, 2009, Boston, Mass.

References

- 1.Prech M, Grajek S, Marszalek A, Lesiak M, Jemielity M, Araszkiewicz A, et al. Chronic infarct-related artery occlusion is associated with a reduction in capillary density. Effects on infarct healing. Eur J Heart Fail. 2006;8:373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rochitte CE, Lima JA, Bluemke DA, Reeder SB, McVeigh ER, Furuta T, et al. Magnitude and time course of microvascular obstruction and tissue injury after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1998;98:1006–1014. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.10.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolognese L, Carrabba N, Parodi G, Santoro GM, Buonamici P, Cerisano G, et al. Impact of microvascular dysfunction on left ventricular remodeling and long-term clinical outcome after primary coronary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2004;109:1121–1126. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118496.44135.A7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heilmann C, Kostic C, Giannone B, Grawitz AB, Armbruster W, Lutter G, et al. Improvement of contractility accompanies angiogenesis rather than arteriogenesis in chronic myocardial ischemia. Vascul Pharmacol. 2006;44:326–332. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McConnell PI, Del Rio CL, Jacoby DB, Pavlicova M, Kwiatkowski P, Zawadzka A, et al. Correlation of autologous skeletal myoblast survival with changes in left ventricular remodeling in dilated ischemic heart failure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:1001–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gavira JJ, Herreros J, Perez A, Garcia-Velloso MJ, Barba J, Martin-Herrero F, et al. Autologous skeletal myoblast transplantation in patients with nonacute myocardial infarction: 1-year follow-up. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131:799–804. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ott HC, Brechtken J, Swingen C, Feldberg TM, Matthiesen TS, Barnes SA, et al. Robotic minimally invasive cell transplantation for heart failure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132:170–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Symes JF, Losordo DW, Vale PR, Lathi KG, Esakof DD, Mayskiy M, et al. Gene therapy with vascular endothelial growth factor for inoperable coronary artery disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68:830–836. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)00807-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henry TD, Rocha-Singh K, Isner JM, Kereiakes DJ, Giordano FJ, Simons M, et al. Intracoronary administration of recombinant human vascular endothelial growth factor to patients with coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2001;142:872–880. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.118471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutanen J, Rissanen TT, Markkanen JE, Gruchala M, Silvennoinen P, Kivelä A, et al. Adenoviral catheter-mediated intramyocardial gene transfer using the mature form of vascular endothelial growth factor-D induces transmural angiogenesis in porcine heart. Circulation. 2004;109:1029–1035. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000115519.03688.A2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jayasankar V, Woo YJ, Pirolli TJ, Bish LT, Berry MF, Burdick J, et al. Induction of angiogenesis and inhibition of apoptosis by hepatocyte growth factor effectively treats postischemic heart failure. J Card Surg. 2005;20:93–101. doi: 10.1111/j.0886-0440.2005.200373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang W, Yang ZJ, Ma DC, Wang LS, Xu SL, Zhang YR, et al. Induction of collateral artery growth and improvement of post-infarct heart function by hepatocyte growth factor gene transfer. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2006;27:555–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo Y, He J, Wu J, Yang L, Dai S, Tan X, et al. Locally overexpressing hepatocyte growth factor prevents post-ischemic heart failure by inhibition of apoptosis via calcineurin-mediated pathway and angiogenesis. Arch Med Res. 2008;39:179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laham RJ, Garcia L, Baim DS, Post M, Simons M. Therapeutic angiogenesis using basic fibroblast growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor using various delivery strategies. Curr Interv Cardiol Rep. 1999;1:228–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seow Y, Wood MJ. Biological gene delivery vehicles: beyond viral vectors. Mol Ther. 2009;17:767–777. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laflamme MA, Chen KY, Naumova AV, Muskheli V, Fugate JA, Dupras SK, et al. Cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells in pro-survival factors enhance function of infarcted rat hearts. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1015–1024. doi: 10.1038/nbt1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dow J, Simkhovich BZ, Kedes L, Kloner RA. Washout of transplanted cells from the heart: a potential new hurdle for cell transplantation therapy. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;67:301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muller-Ehmsen J, Whittaker P, Kloner RA, Dow JS, Sakoda T, Long TI, et al. Survival and development of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes transplanted into adult myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:107–116. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang M, Methot D, Poppa V, Fujio Y, Walsh K, Murry CE. Cardiomyocyte grafting for cardiac repair: graft cell death and anti-death strategies. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:907–921. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Memon IA, Sawa Y, Fukushima N, Matsumiya G, Miyagawa S, Taketani A, et al. Repair of impaired myocardium by means of implantation of autologous myoblast sheets. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:1333–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kondoh H, Sawa Y, Miyagawa S, Sakakida-Kitagawa S, Memon IA, Kawaguchi N, et al. Longer preservation of cardiac performance by sheet-shaped myoblast implantation in dilated cardiomyopathic hamsters. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;69:466–475. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marston WA, Hanft J, Norwood P, Pollak R for the Dermagraft Diabetic Foot Ulcer Study Group. The efficacy and safety of dermagraft in improving the healing of chronic diabetic foot ulcers: results of a prospective randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1701–1705. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.6.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kellar RS, Landeen LK, Shepherd BR, Naughton GK, Ratcliffe A, Williams SK. Scaffold-based three-dimensional human fibroblast culture provides a structural matrix that supports angiogenesis in infarcted heart tissue. Circulation. 2001;104:2063–2068. doi: 10.1161/hc4201.097192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kellar RS, Shepherd BR, Larson DF, Naughton GK, Williams SK. Cardiac patch constructed from human fibroblasts attenuates reduction in cardiac function after acute infarct. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:1678–1687. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mansbridge JN, Liu K, Pinney RE, Patch R, Ratcliffe A, Naughton GK. Growth factors secreted by fibroblasts: role in healing diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Obes Metab. 1999;1:265–279. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1326.1999.00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pacher P, Nagayama T, Mukhopadhyay P, Bátkai S, Kass DA. Measurement of cardiac function using pressure-volume conductance catheter technique in mice and rats. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1422–1434. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woo YJ, Grand TJ, Berry MF, Atluri P, Moise MA, Hsu VM, et al. Stromal cell–derived factor and granulocyte-monocyte colony–stimulating factor form a combined neovasculogenic therapy for ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Atluri P, Liao GP, Panlilio CM, Hsu VM, Leskowitz MJ, Morine KJ, et al. Neovasculogenic therapy to augment perfusion and preserve viability in ischemic cardiomyopathy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:1728–1736. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu YH, Yang XP, Nass O, Sabbah HN, Peterson E, Carretero OA. Chronic heart failure induced by coronary artery ligation in Lewis inbred rats. Am J Physiol. 1997;272(2 Pt 2):H722–H727. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.2.H722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gee MS, Procopio WN, Makonnen S, Feldman MD, Yeilding NM, Lee WM. Tumor vessel development and maturation impose limits on the effectiveness of anti-vascular therapy. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:183–193. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63809-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown L, Fenning A, Chan V, Loch D, Wilson K, Anderson B, et al. Echocardiographic assessment of cardiac structure and function in rats. Heart Lung Circ. 2002;11:167–173. doi: 10.1046/j.1444-2892.2002.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Atluri P, Woo YJ. Pro-angiogenic cytokines as cardiovascular therapeutics: assessing the potential. BioDrugs. 2008;22:209–222. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200822040-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ylä-Herttuala S, Rissanen TT, Vajanto I, Hartikainen J. Vascular endothelial growth factors: biology and current status of clinical applications in cardiovascular medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1015–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beenken A, Mohammadi M. The FGF family: biology, pathophysiology and therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:235–253. doi: 10.1038/nrd2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thai HM, Juneman E, Lancaster J, Hagerty T, Do R, Castellano L, et al. Implantation of a three-dimensional fibroblast matrix improves left ventricular function and blood flow after acute myocardial infarction. Cell Transplant. 2009;18:283–295. doi: 10.3727/096368909788535004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]