Abstract

Introduction

The associations of radiological features with clinical and laboratory findings in Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection are poorly understood. The purpose of this study was to assess the associations.

Material and methods

A retrospective cohort study of 1230 patients with community-acquired pneumonia was carried out between January 2005 and December 2009. The diagnosis of M. pneumoniae infection was made using the indirect microparticle agglutinin assay and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Results

Females were more susceptible to M. pneumoniae infection. Ground-glass opacification on radiographs was positively associated with M. pneumoniae-IgM titres (rank correlation coefficient (r s) = 0.141, p = 0.006). The left upper lobe was more susceptible to infection with M. pneumoniae compared with other pathogens. More increases in the risk of multilobar opacities were found among older or male patients with M. pneumoniae pneumonia (odds ratio, 1.065, 3.279; 95% confidence interval, 1.041–1.089, 1.812–5.934; p < 0.001, p < 0.001; respectively). Patients with M. pneumoniae pneumonia showing multilobar opacities or consolidation had a significantly longer hospital length of stay (r s = 0.111, r s = 0.275; p = 0.033, p < 0.001; respectively), incurring significantly higher costs (r s = 0.119, r s = 0.200; p = 0.022, p < 0.001; respectively).

Conclusions

Our study highlighted female susceptibility to M. pneumoniae pneumonia and the association of ground-glass opacification with higher M. pneumoniae-IgM titres. The left upper lobe might be more susceptible to M. pneumoniae infection. Older or male patients with M. pneumoniae pneumonia were more likely to show multilobar opacities. Multilobar opacities and consolidation were positively associated with hospital length of stay and costs.

Keywords: community-acquired pneumonia, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, radiological features, association

Introduction

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a common infection. Despite substantial progress in therapeutic options, the mortality remains unacceptably high [1], as high as 58% in patients with severe CAP admitted to the intensive care unit [2]. Mycoplasma pneumoniae is an important causative organism of CAP, accounting for 10–30% of all cases [3–5]. The frequency of CAP due to M. pneumoniae was 20.7% in China from December 2003 to November 2004 [6]. Patients infected with M. pneumoniae constitute about 29% of ambulatory adult patients with CAP and about 20% of hospitalized low-risk CAP patients in China [7, 8]. Three–four percent of patients infected with M. pneumoniae are known to develop a severe life-threatening pneumonia with respiratory failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome [9].

Although characteristic computed tomographic (CT) features of M. pneumoniae pneumonia have been described [10], radiological findings are not particularly specific. The disease is most frequently characterized by bronchopneumonic or interstitial infiltrates usually in the lower lobe, unilaterally and centrally dense [11].

Manifestations of infectious diseases may be influenced by both the pathogen and the host. In the case of M. pneumoniae pneumonia, mechanistic correlates of disease severity are poorly characterised. Generally, evidence from research on humans and animal models suggests that the immune system may on the one hand limit disease through the enhancement of host defence mechanisms but on the other hand exacerbate organ damage and systemic disease manifestations. Thus, the more vigorous the cell-mediated immune response and cytokine stimulation, the more severe the clinical illness and pulmonary injury [4]. Consequently, it might be expected that radiological signs of pulmonary lesions in M. pneumoniae pneumonia might vary according to the demographics of the patients and clinical and laboratory findings. To our knowledge, however, these associations have so far been only partly addressed by a few studies [10, 12–15].

In the present study, adult patients with CAP were selected to investigate the associations of radiological features with clinical and laboratory findings in a Chinese affiliated hospital.

Material and methods

Design and setting

A retrospective cohort study was performed of 1230 adult patients who met the criteria for CAP presenting to the Department of Respiratory Medicine in a Chinese affiliated hospital of a medical college from 1st January 2005 to 31st December 2009, thus including five autumn-winter seasons.

Criteria for enrolment

The CAP was defined as an acute infection of the pulmonary parenchyma associated with an acute infiltrate on the chest radiograph with two or more symptoms including fever (> 38°C), hypothermia (< 36°C), rigors, sweats, new cough or change in colour of respiratory secretions, chest discomfort or dyspnoea [16].

Acute M. pneumonia infection was defined as a fourfold or greater increase in specific IgM and/or IgG titres between acute and convalescent phase serum samples. The CAP due only to acute M. pneumonia infection was defined as M. pneumoniae pneumonia. However, CAP caused by other pathogens and not having a fourfold or greater increase in specific IgM and/or IgG titres was defined as other pneumonias. Mixed pneumonia (atypical + bacteria) was discarded. Patients < 18 years of age, any who had been hospitalized during the 28 days preceding the study, and any who had severe immunosuppression (e.g., patients with neutropenia after chemotherapy or bone marrow transplantation, patients with drug-induced immunosuppression as a result of solid-organ transplantation or corticosteroid or cytotoxic therapy, and patients with HIV-related disorders) [17], active tuberculosis, or end-stage diseases, or who had a written “do not resuscitate” order were excluded. We also excluded patients with pulmonary emphysema, idiopathic interstitial pneumonia and malignant diseases. In such patients it is difficult to distinguish bronchopneumonia from lobar pneumonia and unifocal from multifocal disease. There were no patients with concurrent infectious disease.

We used recent definitions of radiological abnormalities as follows [18]:

Ground-glass opacity: On chest radiographs, it appears as an area of hazy increased lung opacity, usually extensive, within which margins of pulmonary vessels may be indistinct. On CT scans, it appears as hazy increased opacity of lung, with preservation of bronchial and vascular margins.

Consolidation: It appears as a homogeneous increase in pulmonary parenchymal attenuation that obscures the margins of vessels and airway walls. An air bronchogram may be present.

Grouping

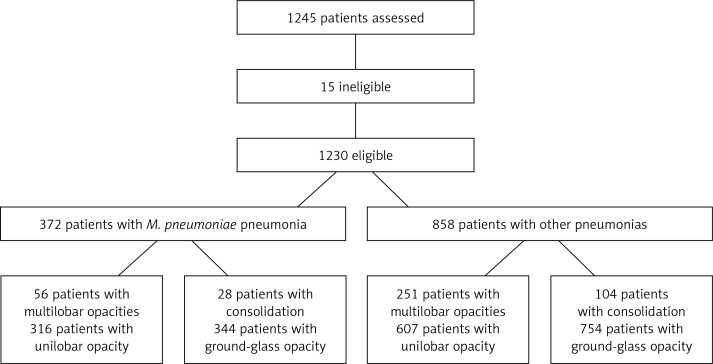

One thousand two hundred and forty-five patients were selected and then 15 cases were excluded from this investigation due to exclusion criteria. A total of 1230 patients were accepted for the study. Three hundred and seventy-two patients with M. pneumoniae-associated pneumonia were included in one group and compared with 858 patients caused by infection due to other pathogens. Patients with ground-glass opacity were further designated as the bronchopneumonia subgroup and those with consolidation as the lobar pneumonia subgroup. Patients were also further subgrouped according to lobar involvement as follows: the unilobar opacity subgroup and the multilobar opacities subgroup (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study Flow Chart

Data collection

Clinical and diagnostic data and radiological features were collected from medical records following discharge. For the detection of M. pneumoniae specific IgM antibodies, the indirect microparticle agglutinin assay (Serodia-Myco II, Fujirebio, Japan, positive threshold value ≥ 1: 40) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Mycoplasma pneumoniae specific IgG antibodies were measured by SERION ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay: Friedrich-Bergius-Ring 19, D-97076 Würzburg, Germany, positive threshold > 30 U/ml). We analyzed M. pneumoniae-IgM titres as continuous variables after natural logarithmic transformation to normalize their distribution. CURB-65 (confusion, urea, respiratory rate, blood pressure, and age) scores at admission and sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) scores at 72 h after commencing therapy were calculated. We also recorded total hospital costs, including pharmacy, radiology, and laboratory costs (including tests of blood, urine and stool, arterial blood gas, and bacterial cultures), examination costs (including lung function tests, electrocardiogram, and ultrasound), medical staff fees (including costs for physicians and nurses), bed or room fees, and other costs such as nebulization and oxygen therapy. Costs of dealing with multiple co-morbidities were excluded. All the patients had chest radiographs and CT scans. The frontal and lateral chest radiographic findings and CT scan images were reviewed and classified independently by two senior radiologists (LH Liang and QZ Zhao) and two senior physicians (YP Zhou and M Li) to ensure accuracy. Missing laboratory findings (most common in patients with less severe illness) were assumed to be normal [19]. The principal investigator reviewed every form and medical record to ensure accuracy. The study was approved by our Institutional Review Board (Review Board of Guangdong Medical College). No informed consent was required because the data were already in existence.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with Statistical Package for the Social Science for Windows version 13.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical variables and continuous variables were reported as percentages and as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), respectively. The χ2 test, unpaired Student's t-test, univariate logistic regression and Spearman rank correlation were employed. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of patients

Characteristics of the patients are presented in Table I. Patients infected with M. pneumoniae were younger, more likely to be female, and more likely to have a less severe condition compared with such patients infected with other pathogens. Mycoplasma pneumoniae was an important causative organism of CAP in the current study, accounting for 30.2% of all cases. All patients underwent diagnostic tests for the detection of the etiologic agent of pneumonia, but the aetiologies were detected in only 21.7% of the patients infected with other pathogens. Hence, the data were not shown.

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of the patients (mean ± SD, n = 1230)

| Variable | M. pneumoniae pneumonia group | Other pneumonias group | t or χ2 value | Value of p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [years] | 31.3 ±11.6 | 50.4 ±22.4 | 15.702 | < 0.001 |

| Age ≥ 65 years [%] | 2.2 | 31.8 | 132.151 | < 0.001 |

| Male sex [%] | 39.8 | 51.0 | 13.717 | < 0.001 |

| Confusion [%] | 0 | 2.1 | 7.963 | 0.005 |

| Body temperature [°C] | 37.5 ±1.1 | 37.5 ±1.1 | 0.281 | 0.779 |

| Respiratory rate [breaths/min] | 19.7 ±2.3 | 20.6 ±2.9 | 5.053 | < 0.001 |

| Low blood pressure* [%] | 15.1 | 14.2 | 0.171 | 0.679 |

| WBC count [109/l] | 7.46 ±3.65 | 8.83 ±4.42 | 5.353 | < 0.001 |

| PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 250 mm Hg [%] | 0 | 3.6 | 13.914 | < 0.001 |

| Serum BUN ≥ 7 mmol/l [%] | 0 | 7.5 | 29.413 | < 0.001 |

| Platelet count [109/l] | 245.69 ±96.52 | 226.57 ±89.34 | 3.469 | 0.001 |

| CURB-65 score: 0-1-2-3-4 [%] | 82.8-17.2-0-0-0 | 53.8-35.4-9.4-1.1-0.2 | 107.118 | < 0.001 |

| Multilobar opacities, n (%) | 15.1 (56) | 29.3 (251) | 29.295 | < 0.001 |

| Consolidation, n (%) | 7.5 (28) | 12.1 (104) | 5.838 | 0.016 |

Systolic < 90 mm Hg; or diastolic ≤ 60 mm Hg, WBC – white blood cell, PaO2/FiO2 – arterial oxygen pressure/fraction inspired oxygen, BUN – blood urea nitrogen, CURB-65 – confusion, urea, respiratory rate, blood pressure, and age

Mycoplasma pneumoniae-IgM titres

The percentages of patients with M. pneumoniae-IgM titres of 1: 80, 1: 160, 1: 320, 1: 640, 1: 1280, 1: 2560 and 1: 5120 in acute phase sera in the M. pneumoniae pneumonia group were 26.9, 21.5, 11.8, 11.8, 20.4, 6.5 and 1.1, respectively. Patients with ground-glass opacification had higher M. pneumoniae-IgM titres compared with such patients with consolidation (1: 2.524 ±1: 0.521 vs. 1: 2.243 ±1: 0.414, t = 2.789, p = 0.006), but there was no significant difference in the titres between patients with a unilobar opacity and those with multilobar opacities (1: 2.515 ±1: 0.515 vs. 1: 2.436 ±1: 0.539, t = 1.024, p = 0.309). Ground-glass opacity showed a significant positive relationship with M. pneumoniae-IgM titres (rank correlation coefficient (r s) = 0.141, p = 0.006). Mycoplasma pneumonia specific IgM titres in convalescent sera and M. pneumonia specific IgG titres were not shown.

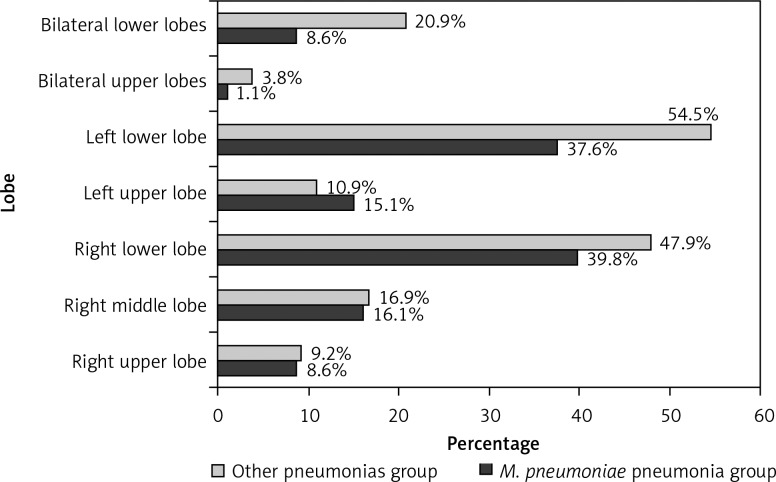

Distribution of opacities

Distribution of opacities amongst the lobes is shown in Figure 2. A significant difference was observed between the two groups (χ2 = 110.824, p < 0.001). Compared with other lobes, the left upper lobe appeared more susceptible to infection with M. pneumoniae than with other pathogens (χ2 = 4.437, p = 0.035).

Figure 2.

Distribution of opacities amongst the lobes

Radiological features according to demographic characteristics

Associations of lobar involvement and parenchymal opacification with patients’ demographic characteristics are depicted in Tables II and III, respectively. Comparisons between the M. pneumoniae pneumonia group and the other pneumonias group are listed in columns, whereas comparisons between the subgroups are shown in rows. More increases in the risk of multilobar opacities were found among older patients than younger patients in both the M. pneumoniae pneumonia group and the other pneumonias group (odds ratio (OR), 1.065, 1.029; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.041–1.089, 1.022–1.035; p < 0.001, p < 0.001; respectively). Older patients with M. pneumoniae pneumonia also showed a trend towards lower susceptibility to lobar pneumonia than younger patients (OR = 0.971; 95% CI: 0.932–1.011; p = 0.155), whereas older patients with other pneumonias had a decreased OR for lobar pneumonia compared with the younger patients (OR = 0.989; 95% CI: 0.980–0.997; p = 0.009). An increased OR for multilobar opacities was observed in male patients with M. pneumoniae pneumonia compared with the female patients (OR = 3.279; 95% CI: 1.812–5.934; p < 0.001), whereas with other pathogens this was decreased (OR = 0.744; 95% CI: 0.570–0.973; p = 0.030).

Table II.

Associations of lobar involvement with clinical and laboratory characteristics (mean ± SD, n = 1230)

| Variable | Group | Multilobar opacities subgroup | Unilobar opacity subgroup | t or χ2 value | Value of p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [years] | M. pneumoniae pneumonia | 39.9 ±15.2 | 29.8 ±10.1 | 6.349 | < 0.001 |

| Other pneumonias | 60.2 ±23.2 | 46.3 ±20.8 | 9.485 | < 0.001 | |

| t | 6.298 | 13.495 | |||

| p | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| Male sex [%] | M. pneumoniae pneumonia | 64.3 | 35.4 | 16.519 | < 0.001 |

| Other pneumonias | 45.8 | 53.1 | 4.695 | 0.030 | |

| χ2 | 6.509 | 27.697 | |||

| p | 0.011 | < 0.001 | |||

| CURB-65 score | M. pneumoniae pneumonia | 0.29 ±0.46 | 0.15 ±0.36 | 2.459 | 0.014 |

| Other pneumonias | 0.90 ±0.85 | 0.45 ±0.62 | 9.523 | < 0.001 | |

| t | 5.312 | 8.076 | |||

| p | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| SOFA score | M. pneumoniae pneumonia | 0.43 ±0.0.74 | 0.23 ±0.53 | 2.459 | 0.014 |

| Other pneumonias | 1.20 ±1.59 | 0.54 ±1.08 | 7.762 | < 0.001 | |

| t | 3.574 | 4.915 | |||

| p | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| Hospital LOS [days] | M. pneumoniae pneumonia | 10.4 ±4.5 | 9.1 ±3.0 | 2.601 | 0.010 |

| Other pneumonias | 11.9 ±10.3 | 9.4 ±4.4 | 5.594 | < 0.001 | |

| t | 1.126 | 1.514 | |||

| p | 0.261 | 0.131 | |||

| Costs [$] | M. pneumoniae pneumonia | 768.22 ±411.26 | 623.47 ±270.69 | 3.375 | 0.001 |

| Other pneumonias | 1204.35 ±1323.26 | 703.60 ±443.74 | 9.122 | < 0.001 | |

| t | 2.366 | 2.564 | |||

| p | 0.019 | 0.010 |

CURB-65 – confusion, urea, respiratory rate, blood pressure, and age, SOFA – sequential organ failure assessment, LOS – length of stay, $ – US dollars

Table III.

Associations of parenchymal opacification with clinical and laboratory characteristics (mean ± SD, n = 1230)

| Variable | Group | Lobar pneumonia subgroup | Bronchopneumonia subgroup | t or χ2 value | Value of p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [years] | M. pneumoniae pneumonia | 28.3 ±8.1 | 31.6 ±11.8 | 1.966 | 0.057 |

| Other pneumonias | 43.8 ±19.7 | 51.1 ±22.6 | 3.360 | 0.001 | |

| t | 4.340 | 15.275 | |||

| p | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| Male sex [%] | M. pneumoniae pneumonia | 28.6 | 40.7 | 1.589 | 0.207 |

| Other pneumonias | 49.2 | 51.2 | 0.178 | 0.915 | |

| χ2 | 3.934 | 11.049 | |||

| p | 0.047 | 0.001 | |||

| CURB-65 score | M. pneumoniae pneumonia | 0.29 ±0.46 | 0.16 ±0.37 | 1.659 | 0.098 |

| Other pneumonias | 0.56 ±0.77 | 0.58 ±0.72 | 0.329 | 0.742 | |

| t | 2.057 | 10.397 | |||

| p | 0.041 | < 0.001 | |||

| SOFA score | M. pneumoniae pneumonia | 0.14 ±0.36 | 0.27 ±0.58 | 1.119 | 0.264 |

| Other pneumonias | 0.64 ±1.34 | 0.75 ±1.28 | 0.823 | 0.412 | |

| t | 3.539 | 6.741 | |||

| p | 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| Hospital LOS [days] | M. pneumoniae pneumonia | 14.1 ±4.4 | 9.5 ±3.6 | 5.409 | < 0.001 |

| Other pneumonias | 14.4 ±13.3 | 9.6 ±5.2 | 7.334 | < 0.001 | |

| t | 0.100 | 0.250 | |||

| p | 0.920 | 0.803 | |||

| Costs [$] | M. pneumoniae pneumonia | 823.44 ±243.93 | 630.76 ±299.72 | 3.944 | < 0.001 |

| Other pneumonias | 1181.28 ±1311.15 | 808.57 ±749.44 | 4.579 | < 0.001 | |

| t | 2.569 | 4.001 | |||

| p | 0.011 | < 0.001 |

CURB-65 – confusion, urea, respiratory rate, blood pressure, and age, SOFA – sequential organ failure assessment, LOS – length of stay, $ – US dollars

Associations of lobar involvements with clinical and laboratory characteristics

Associations of lobar involvements with clinical and laboratory characteristics are shown in Table II. Multilobar opacities had significant positive relationships with CURB-65 scores in both the M. pneumoniae pneumonia group and the other pneumonias group (r s = 0.127, r s = 0.262; p = 0.014, p < 0.001; respectively). Multilobar opacities were associated with longer hospital LOS in both the M. pneumoniae pneumonia group and the other pneumonias group (r s = 0.111, r s = 0.083; p = 0.033, p = 0.008; respectively), incurring significantly higher costs (r s = 0.119, r s = 0.201; p = 0.022, p < 0.001; respectively).

Associations of parenchymal opacification with clinical and laboratory characteristics

Associations of parenchymal opacification with clinical and laboratory characteristics are shown in Table III. Consolidation had significant positive relationships with hospital LOS in both the M. pneumoniae pneumonia group and the other pneumonias group (r s = 0.275, r s = 0.192; p < 0.001, p < 0.001; respectively), as it did with costs despite no association with the severity of the disease (r s = 0.200, r s = 0.151; p < 0.001, p < 0.001; respectively).

Discussion

Our findings show that females were more susceptible to M. pneumoniae infection, that ground-glass opacification had a positive association with M. pneumoniae-IgM titres, that the left upper lobe was more susceptible to infection with M. pneumoniae, that older or male patients with M. pneumoniae pneumonia were more likely to show multilobar opacities, and that patients with M. pneumoniae pneumonia showing multilobar opacities or consolidation had a significantly longer hospital LOS and higher costs.

Radiographic manifestations of M. pneumoniae pneumonia can be extremely variable and mimic a wide variety of lung diseases. The inflammatory response elicited by M. pneumoniae causes interstitial mononuclear cell inflammation that may be manifested radiographically as diffuse, reticular infiltrates of bronchopneumonia in the perihilar regions or lower lobes, usually with a unilateral distribution, and hilar adenopathy [4]. In the current study, the common radiographic features of M. pneumoniae pneumonia on chest radiographs and CT scans were ground-glass opacification, unilobar opacification, or lower lobe involvement as previously described by Mansel et al. [11] and Reittner et al. [20]. Mycoplasma pneumoniae is an extracellular pathogen, the survival of which depends on adherence to the respiratory epithelium, and this fixation to ciliary membranes is conducted primarily by interactive adhesion and accessory proteins. The major adhesion protein is P1 adhesin. Cytoadhesion protects M. pneumoniae from mucociliary clearance [21]. Hydrogen peroxide and superoxide radicals synthesized by M. pneumoniae act in concert with endogenous toxic oxygen molecules generated by host cells to induce oxidative stress in the respiratory epithelium [4]. Attachment of the microorganism to epithelial cilia is responsible for bronchial wall thickening [21]. Therefore, this attachment might be envisaged to interpret higher frequency of the presentation of ground-glass opacification in M. pneumoniae pneumonia compared with other pneumonias and the association of ground-glass opacification with higher M. pneumoniae-IgM titres. Our finding that lobar involvement did not associate with IgM titres is not congruent with what Waites et al. [4] observed (the cold agglutinin response often correlates directly with the severity of pulmonary involvement). On the basis of the current knowledge, we can envisage no definite mechanisms to account for the apparent increase in susceptibility of females to M. pneumoniae infection. As mycoplasma occurs in epidemic cycles, there may be local epidemiologic factors that may have played a role in the female preponderance to mycoplasma infection. Similarly, there is little information to determine the possible reasons why the left upper lobe was more susceptible to infection with M. pneumoniae than with other pathogens and it requires further epidemiological observations. Hence, further studies are warranted.

The frequency of consolidation in association with M. pneumoniae infection appears to vary greatly between studies. One study reported that consolidation was infrequent in adult patients in Japan [10], Hsieh et al. [12] reported a higher frequency of this pattern (38%) in paediatric patients in Taiwan, whereas Hosker et al. [13] reported that 95% of paediatric patients presented with this pattern in Hong Kong and Defilippi et al. [14] showed that consolidation was the commonest finding in children with infection due to M. pneumoniae in Genoa. Bilateral involvement may occur in about 20% of cases [22], but it was observed in only 9.7% of the patients in the current study.

The factors determining disease manifestations and severity in M. pneumoniae infection are only partly understood. Few studies have attempted a clinical comparison of the effects of M. pneumoniae infection according to age. Youn et al. [15] reported that paediatric patients with segmental/lobar pneumonia were older than those with bronchopneumonia in Korea. Defilippi et al. [14] also found that the rate of chest radiographic consolidation was higher in older children with M. pneumoniae infection. There was a significantly increased OR for multilobar opacities in older adult patients and younger adult patients showed a trend toward susceptibility to lobar pneumonia in the current study. These may reflect the fact that the immune response and/or the mucociliary clearance of M. pneumoniae are less active in older adults and younger children, conferring a risk of more severe disease. On the basis of the above-mentioned rationale, it is difficult to interpret the positive association of multilobar opacities with male patients suffering from M. pneumoniae pneumonia in the current study. It warrants further study.

In the current study, the positive association of multilobar opacities, but not consolidation, with severity of the disease is consistent with the common understanding that the presentation of multilobar opacities is one of nine minor criteria for severe CAP [1]. There have been few previous studies about the associations of radiological features with hospital LOS and costs in patients with pneumonia due to M. pneumoniae. The length of stay depends on the time needed to reach clinical stability, which is significantly influenced by the severity of disease [23]. Bilateral or multilobar opacities on chest radiographs of low-risk CAP patients were not significantly associated with higher total costs [8], but we found that multilobar opacities were positively associated with hospital LOS and costs in both groups, as was consolidation despite no association with the severity of the disease, which might have implications for the management of M. pneumoniae pneumonia and other pathogens pneumonia and health economics.

A few laboratory findings were inevitably missed due to retrospective data collection. This phenomenon is most common in patients with less severe illness. Missing values were assumed to be normal in the current study. This strategy is widely used in the clinical application of prediction rules and reflects the methods used in the original derivation and validation of the Pneumonia Severity Index [19]. Even so, some of them might be abnormal. Therefore, the assumption might result in the alterations of statistical power and even statistical results and might give rise to misleading conclusions. Hence, further prospective validation of our findings is warranted.

Several limitations of this study deserve comment. First, the numbers of patients with consolidation or multilobar opacities were relatively small despite this being a cohort study. Had the number been larger, perhaps the results might have been more robust. The best method to detect acute M. pneumoniae infection is a polymerase chain reaction assay. Therefore, a few patients infected with M. pneumoniae might be excluded because of the absence of IgM antibodies in the early stage. It was not multicentre. A further weakness of this study was its retrospective design.

In conclusion, females were more susceptible to M. pneumoniae pneumonia. Ground-glass opacification was associated with higher M. pneumoniae-IgM titres. The left upper lobe might be more likely to be infected with M. pneumoniae compared with other pathogens. Older or male patients with M. pneumoniae pneumonia were more likely to show multilobar opacities. Multilobar opacities and consolidation were positively associated with hospital LOS and costs.

Acknowledgments

Qi Guo and Hai-Yan Li are joint first authors.

We are indebted to the nurses, further education physicians and postgraduates of the Department of Respiratory Medicine, and the staff of the Department of Medical Record for making contributions to this study.

We thank Chris J. Corrigan (King's College London) for assistance in English editing.

The abstract (No. 501) has been accepted for a Thematic Poster at the ERS (European Respiratory Society) Amsterdam 2011 Annual Congress (24-28 September).

The study was funded by the medical science and technology foundation of Guangdong province in 2010 (No. A2010553), the planned science and technology project of Shenzhen municipality in 2011 (No. 201102078), and the non-profit scientific research project of Futian district in 2011 (No. FTWS201120).

References

- 1.Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(Suppl 2):S27–72. doi: 10.1086/511159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Restrepo MI, Anzueto A. Severe community-acquired pneumonia. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2009;23:503–20. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blasi F. Atypical pathogens and respiratory tract infections. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:171–81. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00135703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waites KB, Talkington DF. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and its role as a human pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:697–728. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.4.697-728.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atkinson TP, Balish MF, Waites KB. Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, pathogenesis and laboratory detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32:956–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu YN, Chen MJ, Zhao TM, et al. A multicentre study on the pathogenic agents in 665 adult patients with community-acquired pneumonia in cities of China. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2006;29:3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao B, Ren LL, Zhao F, et al. Viral and Mycoplasma pneumoniae community-acquired pneumonia and novel clinical outcome evaluation in ambulatory adult patients in China. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;29:1443–8. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-1003-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou QT, He B, Zhu H. Potential for cost-savings in the care of hospitalized low-risk community-acquired pneumonia patients in China. Value Health. 2009;12:40–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koletsky RJ, Weinstein AJ. Fulminant Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Report of a fatal case, and review of the literature. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980;122:491–6. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1980.122.3.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyashita N, Sugiu T, Kawai Y, et al. Radiographic features of Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia: differential diagnosis and performance timing. BMC Med Imaging. 2009;9:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2342-9-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mansel JK, Rosenow EC, 3rd, Smith TF, Martin JW., Jr Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia. Chest. 1989;95:639–46. doi: 10.1378/chest.95.3.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsieh SC, Kuo YT, Chern MS, Chen CY, Chan WP, Yu C. Mycoplasma pneumonia: clinical and radiographic features in 39 children. Pediatr Int. 2007;49:363–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2007.02363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hosker HS, Tam JS, Chain CH, Lai CK. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in Hong Kong: clinical and epidemiological features during an epidemic. Respiration. 1993;60:237–40. doi: 10.1159/000196206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Defilippi A, Silvestri M, Tacchella A, et al. Epidemiology and clinical features of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in children. Respir Med. 2008;102:1762–8. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Youn YS, Lee KY, Hwang JY, et al. Difference of clinical features in childhood Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia. BMC Pediatr. 2010;10:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-10-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phua J, See KC, Chan YH, et al. Validation and clinical implications of the IDSA/ATS minor criteria for severe community-acquired pneumonia. Thorax. 2009;64:598–603. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.113795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hilbert G, Gruson D, Vargas F, et al. Noninvasive ventilation in immunosuppressed patients with pulmonary infiltrates, fever, and acute respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:481–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102153440703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Müller NL, Remy J. Fleischner Society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology. 2008;246:697–722. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2462070712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aujesky D, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. Prospective comparison of three validated prediction rules for prognosis in community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med. 2005;118:384–92. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reittner P, Müller NL, Heyneman L, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia: radiographic and high-resolution CT features in 28 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:37–41. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.1.1740037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kashyap S, Sarkar M. Mycoplasma pneumonia: clinical features and management. Lung India. 2010;27:75–85. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.63611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferwerda A, Moll HA, de Groot R. Respiratory tract infections by Mycoplasma pneumoniae in children: a review of diagnostic and therapeutic measures. Eur J Pediatr. 2001;160:483–91. doi: 10.1007/s004310100775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halm EA, Fine MJ, Marrie TJ, et al. Time to clinical stability in patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia: implications for practice guidelines. JAMA. 1998;279:1452–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.18.1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]