Abstract

Introduction

The purpose of this study was to explore the factors influencing the implementation or the lack of implementation of advanced practitioner role in Australia.

Methods

This study uses an interpretative phenomenological approach to explore the in-depth real life issues, which surround the advanced practitioner as a solution to radiologist workforce shortages in Australia. Research participants are radiographers, radiation therapists and health managers registered with the Australian Institute of Radiography (AIR) and holding senior professional and AIR Board positions with knowledge of current advanced practice.

Results

In total, seven interviews were conducted revealing education, governance, technical, people issues, change management, government, costs and timing as critical factors influencing advanced practice in Australia.

Conclusions

Seven participants in this study perceived an advanced practice role might have major benefits and a positive impact on the immediate and long-term management of patients. Another finding is the greater respect and appreciation of each other's roles and expertise within the multidisciplinary healthcare team. Engagement is required of the critical stakeholders that have been identified as ‘blockers’ (radiologists, health departments) as well as identified allies (e.g. emergency clinicians, supportive radiologists, patient advocacy groups). The research supports that the AIR has a role to play for the professional identity of radiographers and shaping the advanced practice role in Australia.

Keywords: Advanced practice, interpretative phenomenological approach, phenomenology, professional boundaries, radiographer reporting, sonographers

Introduction

According to the Australian Government, major changes in healthcare delivery have occurred over the past 10–15 years. Health Workforce Australia's ‘Strategic Framework for Action, Innovation and Reform of the Health Work Force’1 contended that Australia's population is growing, ageing and living longer and health expenditure as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) is rising rapidly. A health sector in which services are delivered not only by doctors, by other health professionals who are safe, potentially cheaper, and most importantly available is now part of Australian health policy.2

A review of the literature paints a compelling picture for change in radiographer roles and practices in Australia that are significantly different to approaches that are being undertaken in comparison to the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States (USA).3–5

The UK Government has challenged traditional methods of care provision causing some blurring of professional boundaries. This resulted in UK hospital trusts facilitating the creation of new roles for nurses and allied health professionals in order to meet ever increasing healthcare demands.3 In recent years a massive growth in applications of radiographic imaging, interventional procedures and image-guided treatments has occurred. This caused a worldwide shortage of radiologists as the numbers being trained failed to keep pace with this greatly expanded workload.3

A significant component of the research for the Australian context has already been undertaken.6–8 Australia has similar healthcare pressures to the UK and USA but has failed to grasp the opportunities that those jurisdictions have taken.9 A reluctance to change has been articulated by local radiologists9 even though the radiologist numbers are not keeping pace with the increasing healthcare needs.7 The change to practitioner status in some other allied health disciplines (e.g. nurse practitioner, sonographers) has already occurred in Australia.10

In April 2012, the Australian Institute of Radiography (AIR) convened a workshop (Inter Profession Advisory Taskforce – IPAT) meeting with representatives from the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists (RANZCR), amongst others, to progress an advanced clinical role for registered radiographers with a summary of thirteen recommendations.11

The UK and the USA have introduced the Radiographer Advanced Practice Model into their jurisdictions and all share the same healthcare challenges of ageing populations, increasing healthcare delivery and service requirements and decreasing ratios of radiologists to support the increased demands.11,12 The main driver for change in the UK was the National Health Service (NHS), seeking to meet the growing demands of the healthcare industry.8,12,13 A decade ago, the UK government introduced legislation to allow approved and certified radiographers to report on selected images, thereby reducing the radiologist workload and hence improving healthcare service delivery and cost savings.12,14

A report published in 2007 from the National Radiotherapy Advisory Group (NRAG) states that the incidence of cancer is set to increase with the ageing population and advises further reductions in time patients wait to receive radiotherapy treatment. It estimated that around 80% of current cancer – centre workload could be carried out by advanced or consultant level practitioners with appropriate oncologist support. Endorsement of NRAG recommendations, which include full implementation of the four- tier radiography career structure in all radiotherapy departments as a potential solution to achieving the increase in capacity required.3 This may lead to more role development opportunities and furthermore, the Royal College of Radiologists (RCR), acknowledged that certain tasks could be delegated to radiographers, provided the change was proper, agreed, planned and monitored so as to avoid prejudicing the outcome for the patient or increasing the likelihood of complaint and litigation.3

Researchers have shown that in some hospitals in the UK, radiologists support and advocated the radiographer's role development; however overall, radiologists were viewed as the main barrier to the adoption of extended roles.14 A recent publication by the RCR has supported this.8 Other barriers to the extension of the radiographer role included, the shortage of radiography and radiology staff and the expense of backfilling in order to release staff for training.8,14

The drivers for change in managing advanced radiographer roles in the UK and USA were largely identified through a data analysis (positivist approach) of the trends of diagnoses undertaken versus the trends of available radiologists to undertake the reporting (on the assumption that only radiologists could undertake the reporting).3,5

There are two main questions that need to be answered by this research. Firstly, why should the advanced practitioner role be pursued in Australia and secondly, why the Advanced Practitioner role has not been implemented yet?

Method

Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) aims to explore individuals' perceptions and experiences in a two-stage interpretation process as the researcher tries to make sense of the participants ‘sense making referred to as a double hermeneutic.15,16’ Although generalisations are not possible in the same way as conclusions stemming from quantitative research, commonalities across accounts and ‘analytical commentary’ may well lead to useful insights that have wider implications.16 These accounts fulfil the need for rigour, by leaving a decision trail.17,18 A qualitative approach, in particular an IPA paradigm, enables participants to share their stories during in-depth interviews, which gives the radiographer a voice, and honours the practice-based knowledge of the participants.19 Each participant was recognised as a unique person rather than just a source of data. The participants' stories were essential to this project and their experiences are accepted as both valid and valuable.

Ethics approval

Human ethics approval was obtained from Charles Sturt University (CSU) Institutional Ethics Committee prior to the commencement of the qualitative research study in December 2011, (protocol number 2012/005).

Sampling

Seven participants were purposively selected from AIR Board members, members of academia, radiographers and radiation therapists working in senior positions in the Public Health sector across Australia. Ten potential participants from the Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, Western Australia and the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) were invited by email to participate and seven agreed. A set of 25 questions was sent to all participants prior to the interview. Consistent with the IPA approach participants were reminded that there were no right or wrong answers but that the researcher was simply interested in learning about their experience of the advanced practice process in Australia.

Data collection

Data was collected during in-depth interviews, which lasted, on average, one hour. To ensure confidentiality occurred, participants were informed that all identifying information provided would be coded so as to de-identify the data. Data collection and data analysis occurred concurrently. Seven interviews were conducted and thematic saturation was achieved, that is no new themes were emerging from the interviews.15

Data analysis

All audiotapes were transcribed verbatim using a professional transcriber. Using IPA methodology, meanings emerged from thematic analysis of the transcribed interviews in keeping with that described by Reid et al.15 and Malim et al.20 Themes were identified and reflected upon with interpretations offered to participants for checking and by cross-analysis with the researcher. Themes from the texts were connected and clustered into super-ordinate themes with related sub-themes. As anticipated, the participants' stories wove a rich tapestry of meaning, shedding light on the causes for the need for change to advanced practice and why the role of advanced practitioner had not been introduced yet in Australia. A summary was outlined and an interpretative, reflexive account written.

Results

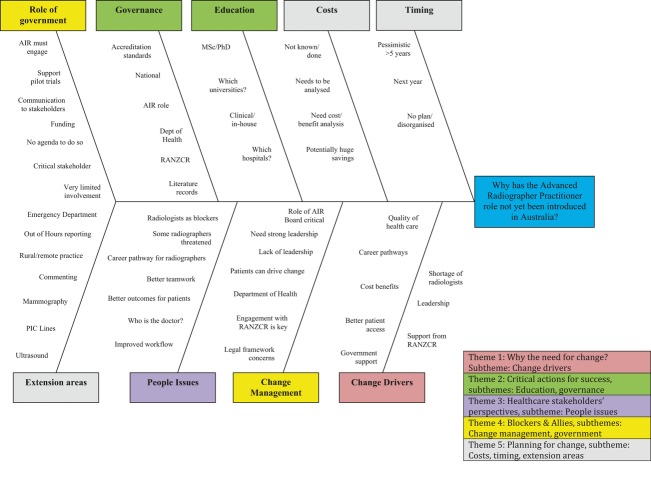

In all, six major themes were identified from the qualitative research study conducted in 2012; which may lead to recommendations being made to policy makers and the AIR community. Nine sub-themes are summarised in the Fishbone Diagram (Fig. 1) that underpin the six major themes identified. Findings reported in this article lead to the last theme, ‘Why hasn't change occurred?’

Figure 1.

Factors influencing the implementation of Advanced Practice in Australia. Classification of the six main themes and underpinning nine subthemes are shown schematically in the Fishbone diagram. Australian Institute of Radiography (AIR); Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists (RANZCR); Master of Science (MSc); Doctor of Philosophy (PhD); Peripherally Inserted Catheter (PIC). Six major themes were identified: Theme 1: Why the need for change? subtheme: Change drivers; Theme 2: Critical actions for success, subthemes: Education, governance; Theme 3: Healthcare stakeholders' perspectives, subtheme: People issues. Theme 4: Blockers & Allies, subthemes: Changed management, Government. Theme 5: Planning for change, subtheme: Costs, timing. Theme 6: Why hasn't change occurred? subtheme: Consistency on Panels, Boards AIR, timing, difference between UK and Australia.

Why the need for change?

Change drivers

All participants in the study understood the need for change and had different levels of familiarity with the situations in the UK and USA that led to the introduction of the advanced practitioner role in those respective jurisdictions. Several cautioned that Australia's case is not directly analogous to the UK's, with the latter having a single National Health System (NHS) and public sector dominated radiological/ radiographic delivery model. This stated, all acknowledged many similar drivers for change (e.g. ageing population, radiologists' shortage, doctors' shortage). Several participants believed that Australia is still not ready for advanced practitioner introduction and that Australia is a decade behind the UK in the need and readiness for change.

In the UK, a huge problem of supply and demand, particularly with aging population and this all started, the best part of 20 years ago. So this education process and this potential for expanding and extending scope slowly evolved and it happened naturally in small pockets around the country. If it was appropriately directed, written up or appropriate training or protocol created within that local site and the employer was aware of it going on consent was provided by the employer. (Participant 4)

Quite simply there aren't enough doctors around to handle the workload. (Participant 3)

New career pathways and leadership roles, the need for job creation, design and changes in multidisciplinary workforce patterns were highlighted as potential areas needed to initiate facilitation of advanced practice.

I think the shortage of radiologists in the NHS was the big driver there- they were certainly top down stuff. The nursing profession as a whole, have sort of taken more of a lead role. I think it has been a nice example of how government and professional bodies can actually work together to address workforce change and the need for changes. (Participant 6)

What critical actions need to be undertaken to drive success?

Education, governance, management

While there was divergence of views on this matter, the case for change must be made clear, and some participants view that this had been most strongly pushed by researchers over the past decade.6,7,10 The participants agreed that education initiatives must be changed dramatically and a Masters degree would be a standard requirement.

For an advanced practitioner we really need to be looking at Master's level, combined between what they might do in-house on the job. (Participant 5)

A stronger engagement with potential allies to change was essential. Limited government engagement was seen to have occurred and the current economic pressures in Australia makes this engagement challenging.

The profession should, the College and I also believe that Departments of Health and the hospitals should have a part to play too. (Participant 7)

There needs to be a collaborative, multi-professional organization of some sort, set up to actually oversee the governance issues. I don't think one occupation group can do it, driving forward without the others. (Participant 6)

Healthcare stakeholders' perspectives

People issues

The participants shared a common view that medical clinicians, and in particular radiologists, were the healthcare group that may have the most to gain but felt as though they were at greatest risk from the introduction of the Advanced Practitioner role.

Certainly some of the advantages are that it's going to better support the medical profession … With the radiologists one of the advantages is we can probably actually bring our relationship a bit closer.

Disadvantages - clearly you get the medical fraternity feeling threatened. (Participant 5)

Patients were the other critical healthcare stakeholder seen to have much to gain with the improvements in key areas of better access and quality of healthcare that would result.

The need to improve turn around time for patients, faster service, less time sitting in Emergency Departments with better outcomes, better care, quality and safety.

I think, potentially, better patient outcomes. Being able to provide a more accurate diagnosis at the point-of-care, rather than further down the track. I think that's probably the principal advantage for clinicians. (Participant 6)

The benefit to the patient is simply time and understanding. I think the biggest criticism any patient has of the healthcare system is the time they spend waiting. (Participant 7)

The radiographer cohort was seen as being of mixed interest. A concern identified was that the radiography fraternity was seen to be a much smaller and less vocal group than the nursing profession, who are some 40% of the Australian professional healthcare workforce, whereas the radiographers were around 5%.21 The majority saw the advantages of an AP role as being a career pathway, recruitment and retention incentive, financial benefits, more responsibility, more interesting job and work-life satisfaction. Disadvantages were hierarchy, more responsibility, and that they were worried about the medico-legal aspects.

The disadvantage is we could create a hierarchy. I don't want to see that happen. The benefit of course the main one is a huge satisfaction- work/life balance for people. To me that's the single greatest benefit. (Participant 7)

As far as disadvantages, I think having to assume more responsibility might be perceived as a disadvantage by some. I think that people are also worried about sticking their necks out and if they got is wrong. They are worried about the medico-legal aspects. (Participant 6)

Other allied health professionals were believed likely to see the introduction as positive and a push to enhance teamwork and to be a leader in the introduction and would benefit from a more collaborative approach of extended practice potentially into their allied health discipline.

An overall improvement in our standards of service, it'll rub off on everybody in terms of improved standards of care and service and running of the department. (Participant 3)

What it does is overall encourage a much more collaborative approach to patient care, working together and not working apart. (Participant 4)

A gaining of professional respect from somebody on another healthcare team. (Participant 5)

The advantages for other healthcare staff are that there could be a template created for further extended practice for some other health professionals. But certainly in some other areas like radiation therapy. (Participant 6)

Healthcare administrators were seen as being equivocal. Advantage for healthcare administrators would be in terms of waiting list reduction and productivity throughput of patients and delivery of service. There would be cost savings with better recruitment and retention of staff.

I think the cost issue comes into it for healthcare administrators. I think the disadvantages for administrators would be there's a perceived medico-legal risk in radiographers being more exposed to legal action. (Participant 6)

‘Obviously money’ Let's say somebody comes in and if they are not treated within short space of time there is capacity for the injury, whatever it might be, to go to a worse outcome. Every time you have a step down in outcome you have a resultant increase in costs. So actually I think over a long term we would see significant savings on budget. (Participant 7)

I think that budgets will probably be the primary disadvantage. The advantages will be though, in terms of waiting-list reduction and productivity and throughput of patients and delivery of services. (Participant 1)

Blockers and allies

Role of government, change management, people issues

There was unanimous consent that the radiologists/RANZCR was the biggest impediment to implementation of the advanced practitioner role.

It's about their loss of power and quite clearly so long as there is such a large proportion in Australia of private radiology … so it is a cash cow and that will be the main impediment to advances in radiography practice. (Participant 2)

They were seen to be a divided group with 50% of radiologists working in radiologist-owned private practices and this group in particular not being interested in changing the current lucrative business model.

I think the medical profession is undoubtedly the biggest impediment. To them, it's about power, and it's about professional boundaries, and it's perceived as a whole that is an erosion of their power base. (Participant 6)

The radiologists in the public sector, on the other hand, were seen to be more likely to be supportive as potentially the government.

It could be the radiologists. If it were, it would be brilliant. At the moment, it's not. I think, potentially, it could be government. (Participant 6)

A major potential ally was seen to be the patient with patient advocacy groups looking for improved healthcare outcomes.

Philosophically, I think name your patient advocacy group. They will be your ally. (Participant 1)

Governments (Federal and State) were seen as both major blockers and allies. Participants saw that governments were more concerned about not spending money, rather than potentially spending some money to save a lot of money and at the same time providing a more cost-effective service to improve overall health outcomes.

Government is critically important. They own the health services. The way that power could be broken is for the government to actually say, we will break your power. But the government doesn't seem prepared to do that at the moment, because I think they're under the influence of the radiologists. (Participant 6)

Other potential allies were seen as emergency physicians, speech pathologists, oncologists, physiotherapists and radiologists.

From what I've heard it is the referring medical practitioners…we have heard from the Emergency Department specialists and so on that it would be a great step forward. (Participant 3)

I'd probably have to say other healthcare professionals like your physios. The allied health side of health care has certainly been advocating for us taking an Advanced Practice role. (Participant 5)

How well planned and resourced is the push for change?

Role of government, costs, timing

Surprisingly, many of the participants had a limited understanding of what plans were in place and what resourcing (people, money) had been allocated over what time frame to drive the push for the implementation of the advanced practitioner role.

One that I would like to see happen would be the government to fund one a large-scale multi-site trial of frontline radiographer reporting. The College of Radiologists is the power broker, and I think we have to play with them to actually make it happen. It happened in the UK. You'll find that in 1999, 2000, they set up a special interest group in radiographer reporting. (Participant 6)

Participants saw that there needs to be further engagement with the government and the radiologists.

What should have happened then are there needs to be further engagement between the key players, and those key players have to involve the College. (Participant 6)

The participants were uncertain around the costs and timing of the project, however it was felt by the seven participants the need to get the universities involved and all working together was a priority.

We probably spent in the IPAT phase - well I know that we spent over $100,000 getting this right. There is probably a two to three year role for a 0.4 project officer. (Participant 7)

A health economist needs to actually have a look at this. The savings that you could potentially make could be huge. (Participant 6)

I don't know. I honestly don't know. (Participant 3)

Why hasn't the change occurred?

Change management, leadership

There was a divergence of opinion on why this had not occurred. Several participants believed that Australia is still not ready for Advanced Practitioner introduction and that Australia is a decade behind the UK in the need and readiness for change. All agreed that leadership was needed and most believed that the AIR Board was the main group to provide strong leadership. A perception of the role of leadership and the need to enlist the support from radiologists and the government were highlighted as the major challenges to the introduction. The key issues were perceived as having the appropriate legal framework in place, the need to be informed of the expectations of responsibilities and inter-professional boundary design and a need to expand scope of practice.

Leadership is massive in driving change and leadership is probably one of our biggest weaknesses in our profession. (Participant 5)

Essentially they have to lead the charge from a point of view engaging with all players. I think the Board seems reluctant to actually pursue any engagement with the HWA-Health Workforce Australia, with the Department of Health and Ageing in Canberra, or with the College of Radiologists. What you actually need for advanced practice to happen is for the political engagement. (Participant 6)

Advanced Practice Advisory Panel (APAP) definitely they are the people who are involved in the profession who can see the potential and who actually don't want to be knockers. It is those people who have a passion for their profession. (Participant 7)

So the blockers have been the radiologists. The leaders for positive change have been the radiologists. There are forward thinking radiologists out there who are being supportive of us piloting for example the radiographer commenting system. (Participant 3)

Discussion

In keeping with the IPA and methodology that informed this study, very careful consideration was given to the essence of the experiences being shared by participants. It was concluded by the researcher and confirmed by the participants that the core experiences being described by them about the concept of the introduction of the advanced practitioner in Australia that they were generally aware of the precedence, especially from the introduction of advanced radiographer practitioner in the UK. Important differences were highlighted between the ease of implementing change in Australia and the UK. The UK had a single powerful government body (the NHS) rather than State and Federal Health Departments in Australia. Also, in the UK most radiologists work in the public sector whereas in Australia, the public/private sector divide is close to 50:50.22

There was, however, a divergence of opinion on the overall benefits, especially for the general radiographer cohort. The radiologist cohort, via the RANZCR, was almost unanimously agreed to be the principal impediment to the introduction. On the other hand, the RANZCR and their other medical colleagues (especially emergency physicians) were potentially seen to be the biggest allies for implementation. The Government's role (State, Federal) was also seen to be crucial to success but most agreed its input to date had been distinctly lacking. In the UK, it was not the Government that made it happen for radiographers, it was the professional body acting on the change in policy with contributions from individuals like Audrey Paterson (OBE) at Society of Radiographers (SoR).23

There was a divergence on where and how leadership was to be provided to assist in driving success. While leadership was acknowledged to be important for success, there was lack of agreement on where it would come from and whether it was currently being demonstrated. Concern was expressed that the AIR Board members were almost all volunteers with limited time to commit to the very large and long- term undertaking needed for energetically driving advanced practitioner status to full implementation. Opinion was divergent on when the advanced practitioner role would actually be introduced. Some saw a staggered approach, commencing as early as next year; whilst this could be introduced progressively via commenting and work in rural or remote locations where radiologists are not available. Others were pessimistic that it would be at least 5 years until implementation.

On the key question of why the Advanced Practitioner role had not yet been introduced, there was uncertainty and divergence. Lack of leadership, need for consistent funding and support from government and lack of interest from the radiographic cohort (through both lack of interest and also lack of information / knowledge) were seen as the main causes. No clear plan (project plan, budget, time-line) was identified, albeit that an excellent status quo update plus recommendations was recently provided by the Inter Profession Advisory Team.11

Participants made no mention or focus on the key issue of change management. Without this key consideration, otherwise technically or financially robust project solutions often fail unless programmes to manage change for impacted people are properly planned and implemented.24 The path to implementation of the advanced practitioner is unclear. The IPAT Report11 is an excellent summary from the multi-party stakeholders on the status quo. However, while identifying many issues that need to be addressed for successful implementation, the actual path forward has not apparently been identified.

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations, participants did not include radiologists or government but, rather, senior radiographers, radiation therapists and AIR Board members who had an interest in advanced practice in Australia, which may lead to potential bias. The recommendations are based on the data from the participants of this study. Although only a limited number, their experiences and thoughts are a platform to initiate discussion related to future directions. In qualitative research it is not possible to bracket out the researcher. The researcher is embedded in the research as the collector of the data and the means of the data analysis.

To honour the richness of the participants' stories, only the theme, being analytical rather than critical, is explored and this must be viewed as a limitation of the paper. Given the qualitative nature of this research project and the small sample size, it is not possible to generalise the findings but it does alert the reader to the possibility that others may experience similar stories. Participants were all advocates for implementation although some were reluctant to go as far as to say that it was likely to happen in the near future because of the lack of support from the ground up and the current stance of the AIR.

Future Research

Future research set around a collaboration of critical stakeholders such as radiographers, radiologists, health departments, educational institutions and government is needed to advance the concept radiographer advance practice in Australia. A basis for future work in Australia could be the well-documented policy models underpinning service delivery developments in the UK.25,26,23

Conclusion

Theme 1: Why should AP be pursued in Australia? Why the need for change?

In this qualitative study focusing on the AP role of the radiographers, all seven participants acknowledged that an ageing population, radiologists' shortage, and doctors' shortage were the key drivers for change to advanced practice. New career pathways and leadership roles, the need for job creation, design and the participants highlighted changes in multidisciplinary workforce patterns as potential areas for future facilitation of advanced practice.

Theme 2: Critical actions for success

The seven participants agreed that approved post-graduate training and a minimum of Masters level in education were critical for success.

Theme 3: Healthcare stakeholders perspectives-people issues

The participants shared a common view that medical clinicians, and radiologists, were the healthcare group that may have the most to gain and that the patients were the other critical healthcare stakeholders seen to gain with improved turnaround time and a reduction in waiting times in Emergency Departments. Another finding is the greater respect and appreciation of each other's roles and expertise within the multidisciplinary healthcare team. For healthcare administrators there would be increase in cost savings with better recruitment and retention of staff.

Theme 4: Blockers and allies; changed management, government

Engagement of the critical stakeholders that have been identified as the principal impediment or ‘blockers’ (radiologists, health departments) on the other hand, (e.g. emergency clinicians, supportive radiologists, patient advocacy groups) were potentially seen to be the biggest allies for implementation. The government's role (State and Federal), was also seen to be crucial to success and its input to date lacking

Theme 5: Planning for change: costs and timing

Participants saw that there needs to be further engagement with the government and the radiologists and the need to get the universities involved and all working together was a priority.

Theme 6: Why hasn't change occurred? Consistency on panels and boards AIR, difference between UK and Australia

The majority of the participants were uncertain about the issue of timing however they all agreed that leadership was needed and that the AIR was instrumental in driving the changes. The key issues were perceived as having the appropriate legal framework in place, the need to be informed of the expectations of responsibilities and inter-professional boundary design and a need to expand scope of practice.

Acknowledgments

The author thank the participants who agreed to participate and also to Mr. Bruce Harvey, immediate past Australian Institute of Radiography (AIR) President and Mr. David Collier, AIR Chief Executive who gave their approval for the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Health Workforce Australia. 2011. National Health Workforce Innovation and Reform Strategic Framework for Action 2011-2015. Available from: http://www.hwa.gov.au/sites/uploads/hwa-wir-strategic-framework-for-action-201110.pdf. Accessed October 2012.

- 2008. The Hon N Roxon, “The Light on the Hill: History Repeating”. Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/ministers/publishing.nsf/Content/sp-yr08-nr-nrsp200908.htm?OpenDocument&yr=2008&mth=9. Accessed 19 April 2012.

- Kelly J, Piper K, Nightingale J. Factors influencing the development and implementation of advanced and consultant radiographer practice – A review of the literature. Radiography. 2008;14:71–8. [Google Scholar]

- Price RC, Le Masurier SB. Longitudinal changes in extended roles in radiography: a new perspective. Radiography. 2007;13:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.radi.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May L, Martino S, McElveny C. The establishment of an advanced clinical role for radiographers in the United States. Radiography. 2008;14:24–7. [Google Scholar]

- Smith TN, Lewis SJ. Opportunities for role development for medical imaging practitioners in Australia: part 1 – rationale and potential. Radiographer. 2002;49:161–5. [Google Scholar]

- Smith TN, Baird M. Radiographers' role in radiological reporting: a model to support future demand. Med J Aust. 2007;186:629–31. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S, Reeves P. The extension of the role of the diagnostic radiographer in the UK National Health Service over the period 1995-2009. Eur J Radiogr. 2009;1:108–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny LM, Andrews MW. Addressing radiology workforce issues. Med J Aust. 2007;186:615–6. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. An Australian perspective. Emerg Nurse. 2008;16:8–12. doi: 10.7748/en.16.5.8.s15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freckleton I. Advanced Practice in Radiography and Radiation Therapy: Report from an Inter-Professional Advisory Team. Australian Institute of Radiograpy (AIR): Melbourne; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Blakeley C, Hogg P, Heywood J. Effectiveness of UK radiographer image reading. Radiol Technol. 2008;79:221–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogg J, Hussain Z. Equality diversity and career progression: Perceptions of radiographers working in the National Health Service. Radiography. 2010;16:262–7. [Google Scholar]

- Price RC, Edwards H, Heaseman F, Herbland A, Le Masurier SB, Miller L. The Scope of Radiographic Practice 2008, A research report compiled by the University of Hertfordshire in collaboration with the Institute for Employment Studies. Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire; 2009. p. 168. [Google Scholar]

- Reid K, Flowers P, Larkin M. Exploring lived experience. Psychologist. 2005;18:20–4. [Google Scholar]

- Smith JA. Reflecting on the development of interpretative phenomenological analysis and its contribution to qualitative research in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2004;1:39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Koch T. Establishing rigour in qualitative research: the decision trail. J Adv Nurs. 2006;53:91–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JA. Hermeneutics, human sciences and health: linking theory and practice. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2007;2:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Offredy M, Vickers P. Developing a healthcare research proposal. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Malim T, Birch A, Wadeley A. Perspectives in Psychology. Hampshire: Macmillan Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Duckett S, Willcox S. The Australian health care system. 4th edn. South Melbourne, Victoria, Australia: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Radiology Workforce Committee. Sydney, Australia: 2011. RANZCR Radiology Workforce Report. [Google Scholar]

- Society of Radiographers. 2013. Preliminary Clinical Evaluation and Clinical Reporting by Radiographers: Policy and Practice Guidance. Responsible person Audrey Paterson. Available from: http://www.sor.org. Accessed 7 May 2014.

- Hiatt JM, Creasey TJ. Change Management – The People Side of Change. Loveland, Colorado: Prosci Learning Centre Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- College of Radiographers. Implementing Radiography Career Progression: Guidance for Managers. London, U.K.: The College of Radiographers; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Society of Radiographers. 2014. Case Study – The Experience at Addenbrookes. Available from: http://www.sor.org/learning/document-library/implementing-career-framework-radiotherapy-policy-practice/case-study-experience-addenbrookes. Accessed 9 March 2014.