Background: The unfolded protein response (UPR) influences cellular differentiation and function.

Results: UPR-inducing agents enhance the differentiation of definitive endoderm cells from mouse ESCs. Inhibition of the UPR prevents the specific differentiation.

Conclusion: The UPR is required for the formation of definitive endoderm cells.

Significance: This study identifies a new molecular mechanism that interconnects the UPR and cell fate decisions in early embryonic development.

Keywords: Cell Culture, Cell Signaling, Development, Differentiation, Embryonic Stem Cell, Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress (ER Stress)

Abstract

Tremendous efforts have been made to elucidate the molecular mechanisms that control the specification of definitive endoderm cell fate in gene knockout mouse models and ES cell (ESC) differentiation models. However, the impact of the unfolded protein response (UPR), because of the stress of the endoplasmic reticulum on endodermal specification, is not well addressed. We employed UPR-inducing agents, thapsigargin and tunicamycin, in vitro to induce endodermal differentiation of mouse ESCs. Apart from the endodermal specification of ESCs, Western blotting demonstrated the enhanced phosphorylation of Smad2 and nuclear translocation of β-catenin in ESC-derived cells. The inclusion of the endoplasmic reticulum stress inhibitor tauroursodeoxycholic acid to the induction cultures prevented the differentiation of ESCs into definitive endodermal cells even when Activin A was supplemented. Also, the addition of the TGF-β inhibitor SB431542 and the Wnt/β-catenin antagonist IWP-2 negated the endodermal differentiation of ESCs mediated by thapsigargin and tunicamycin. These data suggest that the activation of the UPR appears to orchestrate the induction of the definitive endodermal cell fate of ESCs via both the Smad2 and β-catenin signaling pathways. The prospective regulatory machinery may be helpful for directing ESCs to differentiate into definitive endodermal cells for cellular therapy in the future.

Introduction

In embryonic development, the epiblasts migrate to the blastula and form the primitive streak, and the mesoderm and endoderm are then generated (1). Several signaling pathways and cascades of transcription factors have been reported to have roles in the induction and specification of the definitive endoderm at different stages of development (2–6). TGF-β signaling has been thought to be essential for the formation of the definitive endoderm (7, 8). Mutant embryos of Nodal failed to form a primitive streak, and, subsequently, had difficulty to generate both the mesoderm and definitive endoderm (9). Wnt/β-catenin signaling has also been noted to be vital to the development of the primitive streak and definitive endoderm (6, 10). In homozygous Wnt3a knockout embryos, epiblasts migrated to the primitive streak and diverted into neuroectodermal cells (11). In addition to the Wnt/β-catenin and TGF-β pathways, FGF signaling has also been shown to regulate the formation of the primitive streak and the specification of the definitive endoderm (3). Cross-talk among these signaling molecules appear to affect the process as well (3–6, 12, 13). However, the precise regulatory mechanism of the process of gastrulation is still unclear. Whether there are other factors involved in the specification of endodermal cell fate remains elusive.

The ER3 provides a unique environment for protein folding, assembly, and modification. Many insults, including disturbances of calcium homeostasis, changes in redox potential, ionic strength, and requirements of protein folding can pose stress to the ER. Upon ER stress, cells elicit a series of adaptive processes, termed UPR, to cope with ER stress to maintain the homoeostasis of the ER. It has been reported that three transmembrane ER proteins can act as sensors of the UPR, namely protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase, inositol-requiring protein 1 (IRES1) endonuclease/kinase, and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) (14, 15). Under normal conditions, binding immunoglobulin protein (Bip), which is a key ER chaperone, acts as a master regulator of the UPR and binds to the luminal domain of ER sensors to prevent their activations. Upon ER stress, Bip is released from protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase, IRES1, and ATF6, leading to the activation of these UPR signaling pathways. Activated protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase phosphorylates eIF2α, thereby reducing translation initiation and protein synthesis. Activated IRES1 endonuclease/kinase splices the mRNA-encoding X-box binding protein 1 (XBP-1) to allow the translation of mature XBP-1 protein, which mediates the up-regulation of UPR genes involved in protein folding and proteasome-dependent, ER-associated degradation. The ATF6 transcription factor, which is released from Bip, translocates from the ER to the Golgi apparatus, where it is cleaved. The cleaved form of ATF6 then acts as an activated transcription factor to target genes augmenting the capacity of protein folding (15). In general, the UPR integrates pathways to efficiently process newly synthesized proteins in the ER and activates ER-associated degradation to remove misfolded and excessive proteins to maintain homeostasis of ER. However, excessive and persistent ER stress can induce apoptosis (15).

A majority of studies focus on restoration of the homeostasis of the ER by the UPR and ER stress that may lead to the life or death of cells (15). Recently, increasing data indicate that the UPR play important roles in developmental and metabolic processes (16–21) and that ER stress influences chondrocyte differentiation and function (22). However, whether the UPR, because of ER stress, could influence cell fate decisions of the ES cells (ESCs) to become endoderms at the stage of gastrulation is undetermined.

In this study, we used mouse ESCs (mESCs) as a differentiation model for early cell lineage specification at the stage of gastrulation. We employed UPR stress-inducing agents, thapsigargin (TG) and tunicamycin (TM), that activate the UPR and found that these molecules enhanced the specification of the definitive endoderm from ESCs by promoting the nuclear translocation of β-catenin and transiently activating Smad2 signaling.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Induction of ER Stress

Mouse ESCs, E14Tg2a (catalog no. CRL-1821, ATCC (23) and CGR8 (a gift from Austin Smith), were propagated as described previously (24, 25). Embryoid bodies (EBs) were formed from ESCs by culturing in ESC medium without leukemia inhibitory factor (Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA). For the induction of ESCs into a monolayer of endodermal cells, ESCs were allowed to grow overnight without feeder support in the leukemia inhibitory factor-supplemented ESC medium. The medium was then replaced with freshly prepared serum-reduced differentiation medium of advanced RPMI 1640 enriched with 2% FBS, 2 mm l-glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen). UPR-inducing agents, TG and TM, at various concentrations, were added to either EB cultures or endodermal induction cultures. For monolayer culture, cells were allowed to grow with 0.01 μm TG or 0.25 μg/ml TM for 24 h, and then the cultures were further nurtured in the differentiation medium without TG/TM for 24 h or to grow in the presence of 100 ng/ml Activin A for 48 h. For the EB model, EBs were treated with 0.01 μm TG or 0.25 μg/ml TM for 48 h.

In the study of TGF-β/Smad signaling, SB431542 at 10 μm was added to the differentiation medium for 1 h prior to TG or TM treatment. IWP-2 (Stemgent, San Diego, CA), which is an inactivator of Wnt production and secretion, at 10 μm was added to the differentiation medium for 1 h before TG or TM treatment to investigate Wnt/β-catenin signaling. The GSK-3α/β inhibitor CHIR99021 (Merck Millipore) at 1 μm was added to the differentiation medium for 48 h. Chemicals were purchased from Sigma unless stated otherwise.

Definitive Endodermal Induction of ES Cells into Hepatocytic and Pancreatic Lineage Cells

E14Tg2a ESCs were cultured in differentiation medium supplemented with 0.01 μm TG or 0.25 μg/ml TM for 24 h, and continued to be cultured for 24 h without TG/TM. For hepatocytic induction, differentiated cells were allowed to grow in differentiation medium supplemented with 50 ng/ml bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4, R&D Systems), 10 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (Sigma), 20 ng/ml Activin A, and 10 ng/ml VEGF (R&D Systems) for 3 days. Thereafter, the medium was changed to DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with N2B27 (Invitrogen), 10 ng/ml hepatic growth factor (R&D Systems), and 10 ng/ml basic FGF, and cultures continued for 6 days. Cells were further grown in William's E medium (Invitrogen) enriched with 10% FBS, 2 mm l-glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 20 ng/ml EGF (R&D Systems), 10 ng/ml hepatic growth factor, 1 μm insulin, 0.5 mm ascorbic acid or vitamin C (Sigma), and 0.1 μm dexamethasone (Sigma) for 6 days. The cultures were maintained for 6–12 days in William's E medium further supplemented with 10 ng/ml oncostatin M (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ), 1 mm dexamethasone, and 1% insulin-transferrin-selenium (Invitrogen).

For pancreatic induction, differentiated cells were allowed to grow in DMEM supplemented with 2% FBS, 1% insulin-transferrin-selenium, and 2 μm retinoic acid (Sigma) for 1 day. The medium was then replaced with freshly prepared DMEM enriched with 10% FBS, 1% insulin-transferrin-selenium, 20 ng/ml EGF, 10 ng/ml basic FGF, and 50 ng/ml FGF 10 (Sigma) and maintained for an additional 5 days.

RT-PCR and Real-time PCR Analyses

RNA was extracted by using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and transcribed to cDNA using PrimedScriptTM RT Master Mix (Takara, Shiga, Japan). RNA integrity was confirmed by RT-PCR of a ubiquitous mRNA GAPDH. Results were confirmed in at least three separate analyses.

SYBR Green-based quantitative RT-PCR (Takara) was performed using an ABI Prism 7900 HT (Applied Biosystems) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. The relative expression level of each target gene was calculated by the comparative CT method and was normalized to GAPDH expression.

Immunofluorescence Staining

Cells grown on glass slips and 12- and 24-well culture plates were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) in PBS. After three washes, they were permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X (Sigma) and then blocked with 10% normal donkey serum. Cells were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary antibodies diluted in PBS containing 3% BSA as follows: IgG or polyclonal goat anti-Sox17 (1:100, R&D Systems), rabbit IgG or polyclonal anti-β-catenin (1:100, Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit IgG or polyclonal anti-Pdx1 (1:100, Cell Signaling Technology), mouse IgG or anti-CK8 (1: 50, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and mouse IgG or anti-albumin (1:100, Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO). After rinsing with PBS three times, specific cell markers were detected by the corresponding secondary antibodies, Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG, Alexa Fluor 594-conjugaged goat anti-mouse IgG, or Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Life Technologies), at 400-fold dilution in 3% BSA in PBS. Upon completion of washing, cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Sigma). The immunostaining was visualized by using an inverted fluorescence microscope and the corresponding fluorescence filters.

Western blotting

Western blot analyses were carried out as previously reported (26). The following antibodies raised from rabbit were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology to identify the specific proteins: rabbit anti-Bip, rabbit anti-p-eIF2α and eIF2α, rabbit p-GSK3β and GSK3β rabbit anti-p-Smad2 (Ser465/467) and Smad2, rabbit anti-GAPDH, and rabbit anti-β-catenin. Mouse anti-β-Actin was from Sigma, and Rabbit p21 was from Abcam.

Flow Cytometry

For cell phenotype analysis, cultures were dissociated by trypsinization and washed with cold PBS. Having been fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, cells were permeabilized with 0.2% cold Triton X-100. They were washed and separately stained with IgG or polyclonal goat anti-Sox 17 antibody diluted to 1:50 in PBS with 1% normal bovine serum and 0.1% Triton X-100 at 4 °C. After washing twice with PBS, cells were incubated with FITC-conjugated rabbit anti-goat antibody diluted in 1% normal bovine serum. Upon completion of washing, labeled cells were resuspended, and at least 105 events were acquired by using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer and analyzed using CellQuest Version 3.1 software (BD Biosciences). The background of nonspecific antibody uptake was evaluated by staining in parallel with a FITC-conjugated isotype-matched control antibody.

For cell surface staining, cells were dissociated with 0.02% EDTA and incubated with biotin-conjugated anti-E-cadherin mAb (eBioscience). After washing twice, cells were incubated with allophycocyanin-conjugated streptavidin (eBioscience) and phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CXCR4 mAb (eBioscience).

Luciferase Reporter Assays

E14Tg2a ESCs were transfected with 7TFP (7XTcf promoter) from Addgene (27) and selected with puromycin to obtain a wnt-responding ESC line. TG/TM was added to the differentiation medium for 24 h, and then the cells were harvested for luciferase activity analysis. The luciferase activities in the samples were measured using a Dual-Luciferase reporter assay system (Promega).

Statistical Analysis

Data derived from at least three independent experiments are presented as mean ± S.D. unless stated otherwise. The relative mRNA levels were quantified by using the 2−ΔΔCT method and averaged by normalization to GAPDH expression. Statistical significance was tested by Student's t test. SPSS 13.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL,) was used, and p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Thapsigargin and Tunicamycin Trigger ER Stress and Activate the UPR

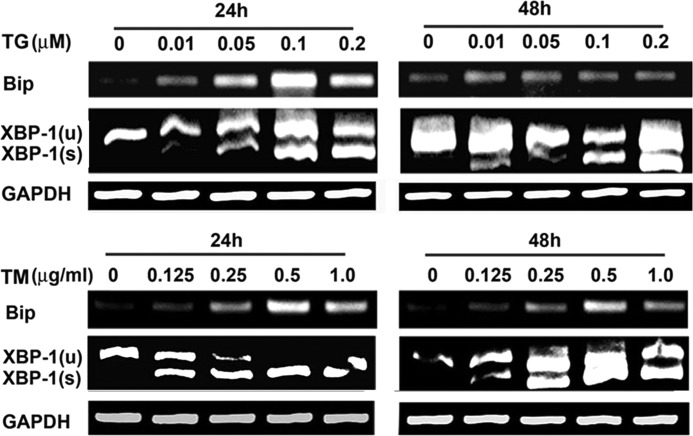

ER stress affects the expression of many genes and influences cellular differentiations and functions (20, 22, 28, 29). Therefore, we hypothesized that ER stress might simulate the specification of the germ layer at the stage of gastrulation. First, we used ESCs as an in vitro differentiation model. Second, we set up an experimental condition to trigger ER stress, which activates the UPR. We tested the effect of the widely used ER stress-inducing agents TG and TM on 2-day cultures of EBs derived from ESCs. RT-PCR demonstrated that the gene expressions of Bip and XBP-1(s), which is the active isoform of XBP-1 after splicing, were up-regulated in mouse ESC-derived EBs treated with TG and TM in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1). Both compounds could activate the UPR at low concentrations (TG, 0.01 μm; TM, 0.25 μg/ml) in 2 days.

FIGURE 1.

TG or TM activates the UPR in 2-day EBs from mESCs. Shown are representative images of RT-PCR products of Bip and XBP-1 derived from 2-day EBs developed from mouse ESCs (E14Tg2a) treated with and without 0.01–0.2 μm TG or 0.01–0.2 μg/ml TM for 24 and 48 h, respectively. An up-regulation of the gene expression levels of Bip and XBP-1(s) was noted in the treated cell samples. XBP-1(u), uncut XBP-1; XBP-1(s), spliced XBP-1.

ER Stress Enhances Endodermal Differentiation of ESCs in EBs

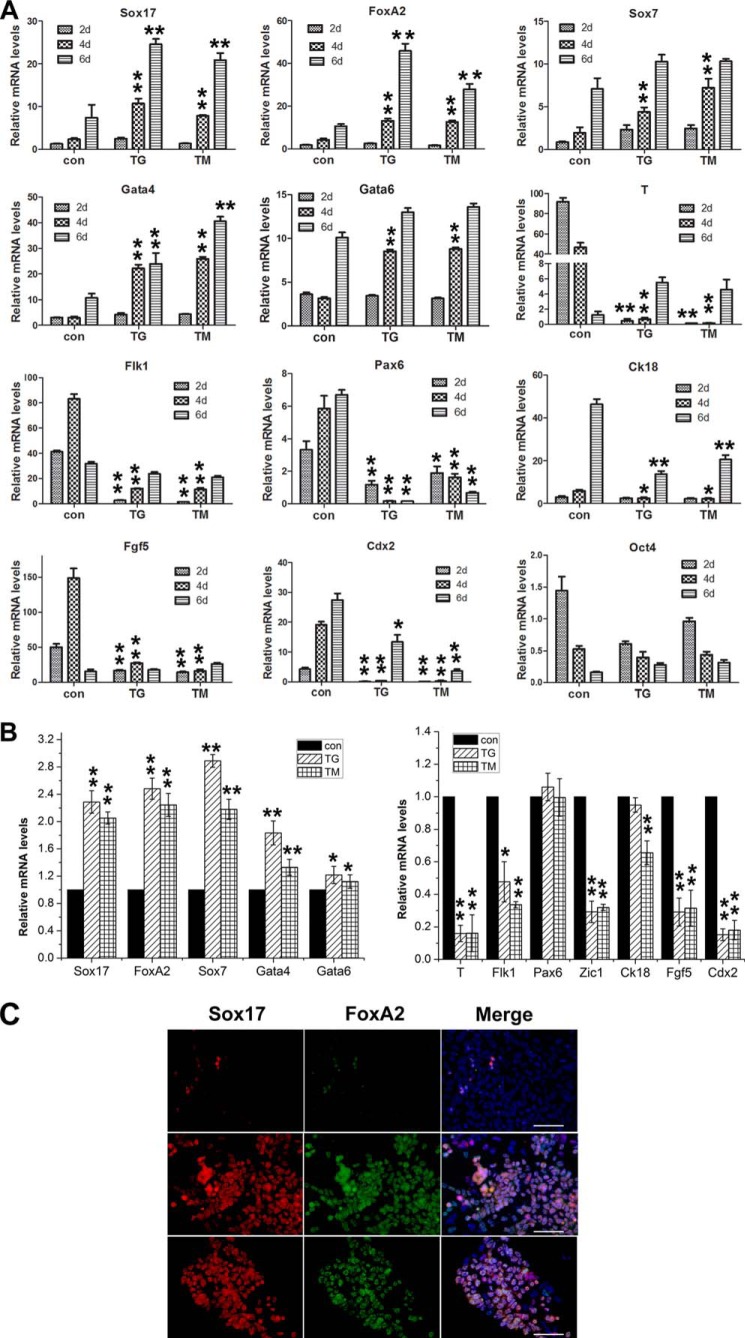

To study the effects of ER stress on the differentiation of ESCs, we differentiated ESCs in an EB model. EBs derived from mouse ESCs were cultured in differentiation medium with the supplement of either TG or TM for 2 days, followed by 4-day culture in the medium with neither supplement. Real-time PCR for the endodermal genes Sox17 and FoxA2 from cultures over the time course revealed a dramatic increase of gene expression in treated cultures compared with control cultures (Fig. 2). In addition, TG and TM also enhanced the expression of primitive endodermal genes, Sox7, Gata4, and Gata6 (Fig. 2A). Conversely, down-regulation of the gene expression of mesodermal T and Flk1, ectodermal Pax6 and Ck18, the epiblast marker Fgf5, and trophectodermal Cdx2 was observed in TG- and TM-treated cultures compared with untreated counterparts, whereas the expression of the pluripotent gene Oct4 became diminished in TG- and TM-treated cultures compared with the control cultures (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

TG and TM enhance the differentiation of endoderms derived from mESCs in EB models. A, real-time PCR analysis for the expression of marker genes in EBs treated with either 0.01 μm TG or 0.25 μg/ml TM for 2 days and followed by 4-day cultures in the same medium without the supplement. The levels of mRNA in ESCs was set as 1. con, control cultures. Data are shown as the mean ± S.D. (n = 3); *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01 compared to controls. B, relative gene expression levels on 2-day EBs grown in low-serum differentiation medium with either TG or TM for 2 days. The levels of mRNA in cells without the supplement was set as 1. Data are shown as the mean ± S.D. (n ≤ 3); *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 compared with controls. C, immunofluorescence staining of Sox17- and FoxA2-positive cells in 2-day EBs cultures supplemented with TG/TM for 2 days. Scale bars = 50 μm.

To further observe the effect of TG/TM on the differentiation of EBs, 2-day EBs were allowed to differentiate in TG- or TM-supplemented differentiation medium for 2 days. Real-time RT-PCR analysis demonstrated a significant increase of endodermal gene expression in cultures with TG and TM compared with the control cultures, whereas T, Flk1, Fgf5, and Cdx2 expressions were remarkably down-regulated (Fig. 2B). In addition, immunofluorescence staining showed that the numbers of Sox17- and FoxA2-positive cells in the cultures treated with TG/TM were notably more than those in the control cultures (Fig. 2C). Taken together, these data suggest that ER stress-induced UPR enhances definitive endodermal differentiation and inhibits other germ layer commitments of ESCs in EBs of mouse origin.

ER Stress Promotes Definitive Endodermal Differentiation of ES Cells in Monolayer Cultures

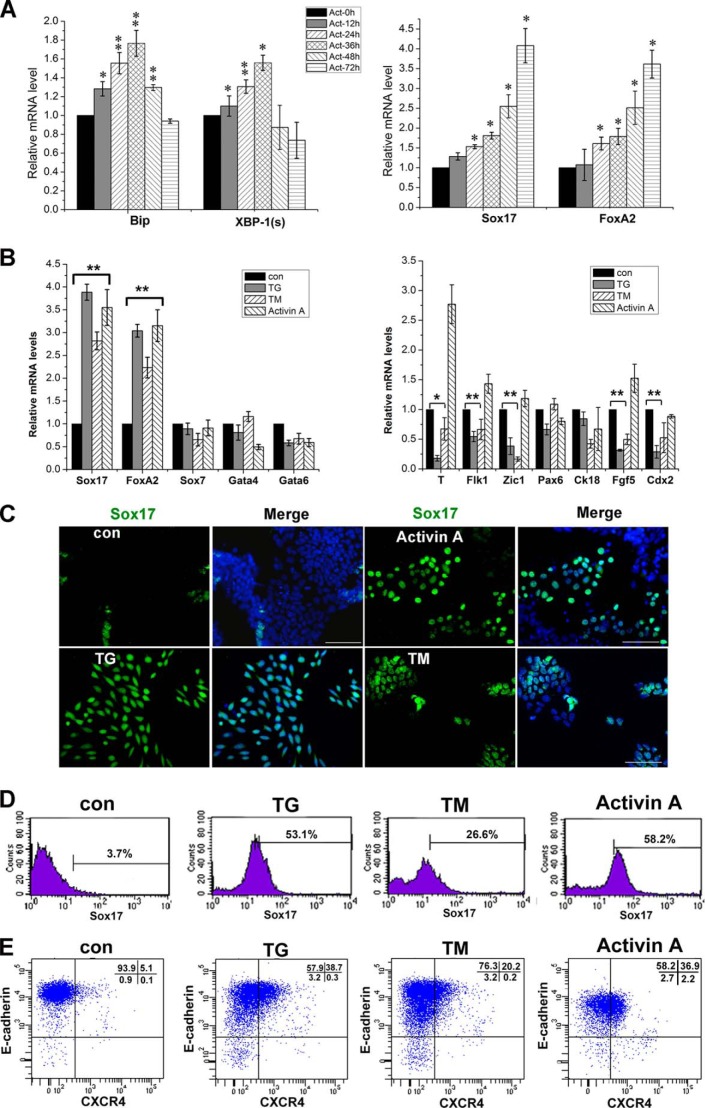

To further determine whether definitive endoderm differentiation was associated with the UPR, we treated ESCs with Activin A. Mouse ESCs were grown in differentiation medium on a monolayer in the presence of Activin A at a high concentration of 100 ng/ml for 72 h. The gene expression of Bip and XBP-1(s) was up-regulated progressively in the first 36 h, whereas the expressions of the definitive endodermal genes Sox17 and FoxA2 increased steadily up to 72 h (Fig. 3A). These findings suggest that the definitive endodermal lineage commitment of ESCs might be associated with the UPR.

FIGURE 3.

Characterization of definitive endodermal cell derivatives from differentiation cultures of ESCs in monolayer culture under ER stress. A, relative gene expression levels of Bip, XBP-1(s), Sox17, and FoxA2 from mouse E14Tg2a ESCs cultured in differentiation medium supplemented with 100 ng/ml Activin A for 72 h. B, real-time PCR analysis for marker gene expression levels in cells treated with TG/TM (0.01 μm TG/TM for 24 h and maintained in the medium without the supplement for 24 h) or 100 ng/ml Activin A for 48 h. con, control. A and B, the level of mRNA in cells without the supplement was set as 1. Data are shown as the mean ± S.D. (n ≤ 3); *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01 compared to controls. C, immunofluorescence staining of Sox17-positive cells in the cultures supplemented with either TG/TM or Activin A as in B. Scale bars = 50 μm. D, flow cytometry analysis for Sox17-positive cells in cultures treated with TG/TM or Activin A as in B. E, flow cytometry assays for E-cadherin and CXCR4 double-positive cells from cultures treated with TG/TM or Activin A as in B.

To confirm whether ER stress promotes definitive endoderm differentiation, we adopted a monolayer culture differentiation model. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis showed that for gene expression on monolayer cultures of ESCs, which grew in the presence of TG/TM or Activin A, displayed a significant up-regulation of the definitive endodermal genes Sox17 and FoxA2 compared to those of control cultures (Fig. 3B) or the EB cultures in the presence of ER stress (Fig. 2). Therefore, monolayer ES cultures, rather than EB cultures were used in the subsequent experiments. In contrast, there was a down-regulation of the T, Flk1, Zic, Fgf5, and Cdx2 genes in cells treated with TG/TM (Fig. 3B).

Immunofluorescence staining revealed that stronger green fluorescent signals were observed in 24-h TG- or TM-treated monolayer ESC cultures as compared to those in the control cultures, confirming the up-regulated expression of the Sox17 gene by real-time PCR (Fig. 3C). The numbers of Sox17-positive cells in TG- or TM-treated monolayer cultures quantified by flow cytometry were significantly more than those in control cultures (Fig. 3D).

It should be pointed out that Sox17 is not only expressed in the definitive endoderm, but also expressed in the visceral endoderm, which will form an extraembryonic yolk sac (30, 31). To date, a few markers are available to distinguish visceral and definitive endoderm cells. Among these markers, CXCR4 and E-cadherin double-positive cells have been reported to define definitive endodermal cells by FACS analysis (32). As shown in Fig. 3E, CXCR4 and E-cadherin double-positive cells in TG- or TM-treated monolayer cultures were remarkably more than those in control cultures. Moreover, TG-treated cultures yielded similar numbers of double-positive events compared with cultures supplemented with Activin A.

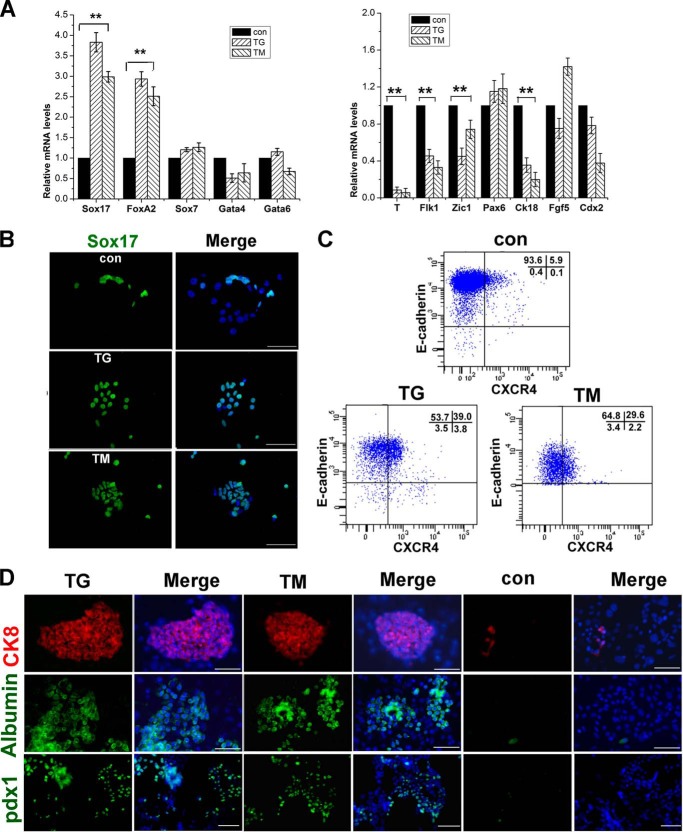

To further validate the above results, CGR8 cells, another mESC line, were treated with TG/TM on monolayer culture. Quantitative real-time PCR results showed that expression of the endodermal genes Sox17 and FoxA2 was increased significantly in the TG-/TM-treated cells compared with control cultures (Fig. 4A). Inversely, mesodermal genes were down-regulated in TG/TM-treated cells compared with the control group (Fig. 4A). Immunofluorescence staining showed that the numbers of Sox17-positive cells in cultures treated with TG/TM were significantly more than those in control cultures (Fig. 4B). In addition, flow cytometry assays with CXCR4 and E-cadherin antibodies also indicated that the numbers of CXCR4 and E-cadherin double-positive cells in TG- or TM-treated monolayer cultures were remarkably more than those in the control group (Fig. 4C). These observations demonstrate that ER stress-induced UPR enhances definitive endodermal differentiation.

FIGURE 4.

Characterization of definitive endodermal cells derived from CGR8 mESCs and developmental potential of TG/TM-induced definitive endoderm cells derived from E14Tg2a ESCs. A, induction of CGR8 mESCs by TG/TM to differentiate into definitive endodermal cells in monolayer cultures. Shown is a real-time PCR analysis for marker gene expression levels in cells treated with TG/TM for 24 h and maintained in medium without the supplement for 24 h. con, control. The level of mRNA in cells without the supplement was set as 1. Data are shown as the mean ± S.D. (n ≤ 3); *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01 compared to controls. B, immunofluorescence staining of Sox17 in cultures treated with TG/TM as in A. Scale bars = 50 μm. C, flow cytometry assays for E-cadherin and CXCR4 double-positive cells in cultures treated with TG/TM as in A. D, immunofluorescence staining of the hepatocytic lineage markers CK8, albumin, and the pancreatic progenitor marker Pdx1 in cultures upon completion of the induction as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Scale bars = 50 μm.

It is well known that definitive endoderm cells can further differentiate into functional hepatocytes and insulin-secreting cells, which is of significance for regeneration medicine. Therefore, it is important to evaluate the differentiation potency of the definitive endodermal cells from TG/TM-treated ESCs. To address the differentiating potential, we first treated mESCs with TG/TM to form a definitive endoderm, and then kept the cells in differentiation medium with the growth factors described under “Experimental Procedures.” In the control group, mESCs were first maintained in differentiation medium without treatment, and then the growth factors were added. Immunofluorescence staining demonstrated the expression of cytokeratin 8 (CK8) and albumin in the cultures upon completion of the induction into hepatocytic lineage cells. The expression of the pancreatic progenitor marker Pdx1 was also noted in the cultures upon completion of the differentiation to the pancreatic lineage (Fig. 4D).

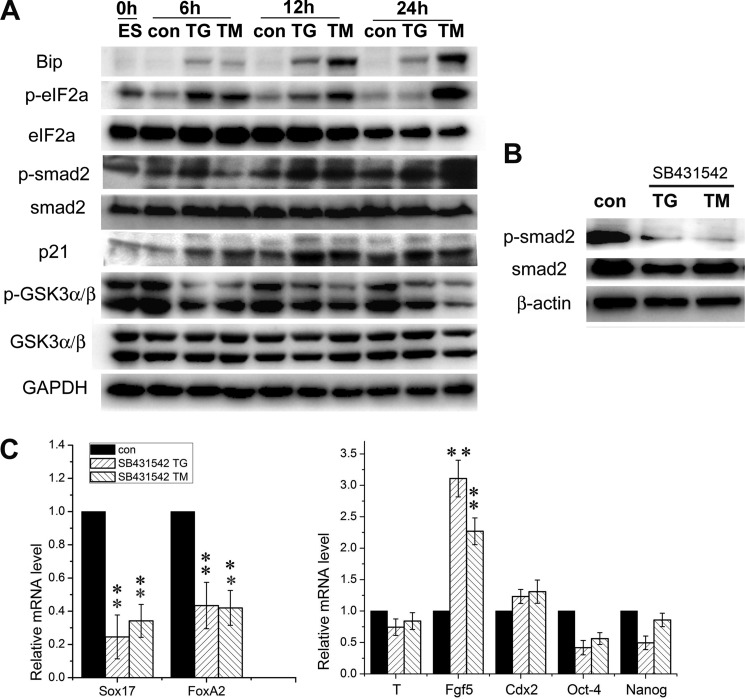

TGF-β/Smad Signaling in the Definitive Endodermal Specification of ESCs under ER Stress

ER stress can active a number of signaling pathways (22, 33, 34). Previous studies reported that the TGF-β/Smad, Wnt/β-catenin, and FGF signaling pathways can regulate the formation of the definitive endoderm (2, 4, 7). To test which signal that activates ER stress is associated with definitive endoderm differentiation, we performed Western blotting assays with the whole lysate from ESCs treated with TG/TM and found an active translation of Bip, which was not evident in the control cultures (Fig. 5A). In addition, phosphorylated eIF2α was seen in treated cells, indicating that ER stress did activate the UPR. It was also noted that phosphorylated Smad2 was up-regulated in cells treated with either TG or TM at 6–24 h (Fig. 5A). To provide additional evidence for the activation of the TGFβ/smad2 signaling pathway during ER stress, we analyzed downstream target gene expression. TGF-β/Smad signaling has been considered a tumor suppressor pathway by inhibiting cell growth, which is mediated by up-regulation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p15/INK4b and p21/WAF1 (35, 36). We found that the expression level of p21 was up-regulated, similar to that of p-smad2 (Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5.

Involvement of the TGF β/Smad2 signaling pathway during the definitive endodermal specification of ESCs under ER stress. A, Western blotting of proteins extracted from ESCs treated with TG or TM at 6–24 h. GAPDH was used as the loading control (con). B, Western blot assay for the cell lysate from mESCs treated with 10 μm Smad antagonist SB43152 and TG/TM. C, real-time PCR assay for marker gene expression levels of cells treated with SB431542 as above. The level of mRNA in cells without the supplement was set as 1. Data are shown as the mean ± S.D. (n ≤ 3); *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01 compared to controls.

To verify the role of Smad2 in the definitive endodermal induction of ESCs under ER stress, 10 μm SB431542 was supplemented to ESC cultures with TG or TM. Western blot analysis showed that SB431542 did inhibit smad2 signaling activated by TG/TM (Fig. 5B). Quantitative RT-PCR revealed a significant down-regulation of the definitive endodermal genes Sox17 and FoxA2 and up-regulation of Fgf5 in the cultures examined compared with those in the control cultures (Fig. 5C). These data suggest that ER stress enhances the definitive endodermal specification of ESCs via TGF-β/Smad2 signaling.

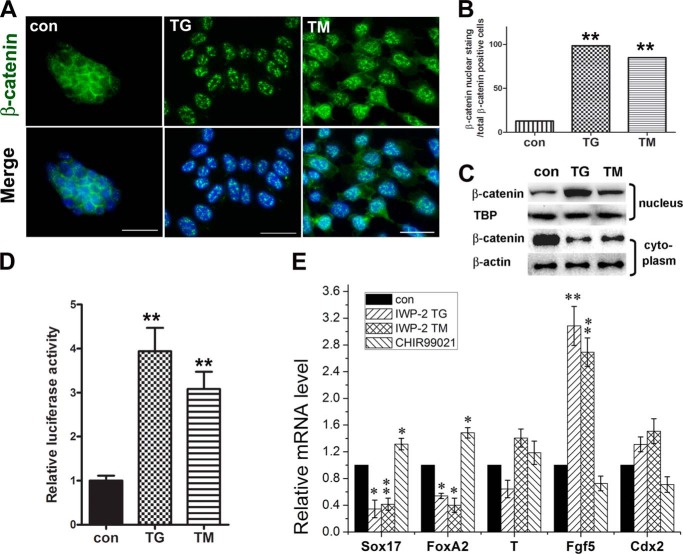

Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling in Definitive Endoderm Differentiation of ESCs under ER Stress

Apart from phosphorylated Smad2, which was up-regulated, we also found a down-regulation of phosphorylated GSK3α/β proteins in these cultures under ER stress (Fig. 5A), which phosphorylates cytoplasm β-catenin and subsequently degrades it by proteasome (37). As shown in Fig. 6A, immunostaining of β-catenin revealed that nuclear β-catenin in cells treated with TG/TM for 24 h was remarkably more than those in the control group. Quantification of the percentage of cells with β-catenin nuclear staining over the total β-catenin positive cells showed a significantly higher percentage in TG-treated (∼98.5%) or TM-treated (about 85.1%) cells than that in the control group (∼12.9%) (Fig. 6B). The same results were observed by Western blot analysis at the protein level (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

Involvement of Wnt/β-catenin signaling during the definitive endodermal commitment of ESCs under ER stress. A, immunofluorescence staining of β-catenin in ESCs in differentiation cultures supplemented with TG/TM for 24 h. con, control. Scale bars = 20 μm. B, quantification of the percentages of cells with β-catenin nuclear staining over total β-catenin-positive cells. Five to six representative visual fields for each of the groups were counted. C, TCF luciferase wnt reporter assays of cell lysates from TG/TM-treated cells. D, Western blotting of β-catenin extracted from cell derivatives of the nucleus and cytoplasm from ESCs under the same differentiation conditions for β-catenin staining. TATA-binding protein (TBP) and β-actin were used as loading controls for nuclear protein and cytoplasmic protein, respectively. E, real-time PCR analysis for marker gene expression levels in cultures treated with 10 μm IWP-2 and TG/TM, or 1 μm GSK-3α/β inhibitor CHIR 99021. B, D, and E, the level of mRNA in cells without the supplement was set as 1. Data are shown as mean ± S.D. (n ≤ 3); *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 compared to controls.

To determine whether the wnt/β-catenin signaling also participated in the process of definitive endoderm induction from ESCs by the UPR, we tested TCF (T cell transcription factor) luciferase wnt reporter activity in treated cell lysates. The luciferase activity in the cell lysates of the TG/TM-treated cells for 24 h was evidently enhanced compared with control cultures (Fig. 6D). These findings indicate an involvement of β-catenin signaling in the definitive endoderm differentiation of ESCs under ER stress.

To provide more evidence that wnt/β-catenin-mediated definitive endoderm differentiation is induced by ER stress, we applied IWP-2 and CHIR99021 to the cell culture. Quantitative RT-PCR for gene expression from the differentiation cultures of ESCs exposed to 10 μm IWP-2 with and without TG or TM displayed a significant down-regulation of Sox17 and FoxA2 and up-regulations of Fgf5 compared with control cultures (Fig. 6E). Inversely, a pattern of up-regulated expression of Sox17 and FoxA2 was observed in the differentiation cultures of ESCs treated with 1 μm GSK3α/β inhibitor CHIR99021 (Fig. 6E). The data suggest that Wnt/β-catenin signaling may play a role in definitive endoderm differentiation of ESCs under ER stress.

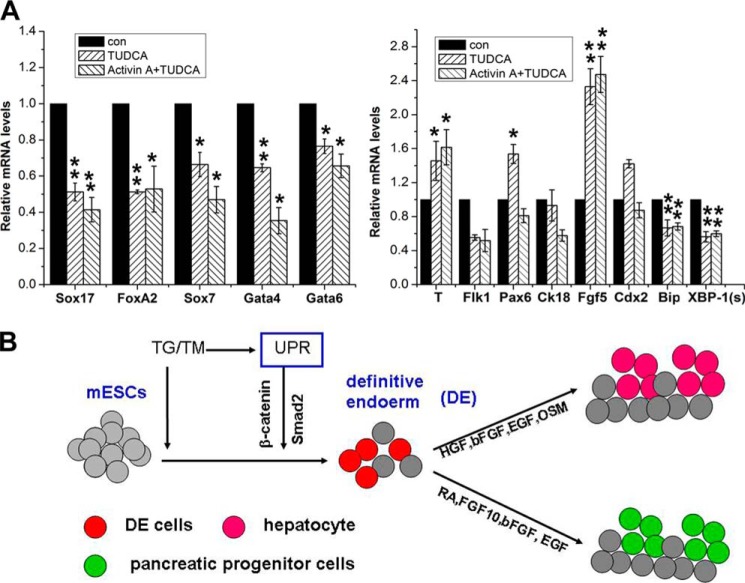

Inhibition of ER Stress Abolishes the Differentiation of the Endoderm

To investigate whether UPR induced by ER stress is requisite for definitive endodermal specification, we adopted the ER stress inhibitor tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA) to treat ESCs. We performed quantitative RT-PCR for gene expression on cell derivatives of ESCs in differentiation cultures supplemented with 300 μm TUDCA for 48 h. Down-regulation of the ER stress-related genes Bip and XBP-1(s), the definitive endodermal genes Sox17 and FoxA2, and primitive endodermal genes and up-regulation of T and Fgf5 were observed (Fig. 7A). To further verify whether the UPR is necessary for the specification of the definitive endoderm, 300 μm TUDCA, together with 100 ng/ml Activin A, was added to the ESC culture and maintained for 48 h. Sox17 and FoxA2 were also found to be down-regulated significantly (Fig. 7A). Together, these data indicate that inhibition of ER stress does nullify the definitive endodermal specification of ESCs.

FIGURE 7.

Inhibition of ER stress hinders the formation of the definitive endoderm. A, real-time PCR for marker gene expression levels in ESC differentiation cultures supplemented with 300 μm TUDCA in the presence or absence of Activin A for 48 h. con, control. The level of mRNA in cells without the supplement was set as 1. Data are shown as mean ± S.D. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 compared to controls. B, schematic of enhanced induction of definitive endodermal cells from mESCs via UPR induced by TG/TM. HGF, hepatic growth factor; bFGF, basic FGF; OSM, oncostatin M; RA, retinoic acid.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to show that ER stress-mediated UPR can stimulate the definitive endodermal specification of ESCs in in vitro systems of induction cultures of EBs and monolayers of mouse ESCs. The definitive endodermal lineage commitment of mouse ESCs could be kindled by using low dose of ER stress agonists, 0.01 μm TG and 0.25 μg/ml TM, to induce ER stress without provoking remarkable cell apoptosis (data not shown). Supplementing the ER stress inhibitor TUDCA in ESC cultures abolishes the definitive endodermal commitment even when Activin A was added, which induces the definitive endoderm (Fig. 7A) (8, 38). These observations suggest that the UPR is requisite for the definitive endodermal cell fate decision during the formation of gastrulation (Fig. 7B).

Previous studies have reported that the Nodal/Activin A (9), Wnt/β-catenin (2, 12, 39), and TGF-β signaling pathways can regulate the formation of the primitive streak and the specification of the definitive endoderm (3). To test which pathway controls the specification of the definitive endoderm in which the UPR participates, we performed Western blotting experiments with the protein extracts of ESCs treated with TG/TM at time points from 0–24 h and found that p-smad2 was up-regulated and p-GSK3α/β was down-regulated (Fig. 5A). These data indicate that TG/TM could specifically active the TGF-β/Smad2 and Wnt/β-catenin pathways. To ascertain the signaling in the TGF-β/Smad2 and Wnt/β-catenin pathways, we also assessed TGF-β/Smad2 downstream gene p21 expression and β-catenin TCF luciferase reporter activity. The results showed that p21 was up-regulated and that TCF luciferase activity was enhanced when the cells were treated with TG/TM. Furthermore, we applied the TGF-β smad inhibitor SB431542 and the inactivator of Wnt production (IWP-2) to ESCs prior to the administration of pharmaceutical inducers of ER stress and found that these molecules were able to block the definitive endoderm specification of ESCs under ER stress. In agreement with our hypothesis, it has been reported that mutant mice that missed an allele of Smad2 and Smad3 displayed definitive endodermal defects (7). Activin induces the definitive endoderm in ESCs via the Smad2 pathway (8, 38). In embryos lacking β-catenin, the definitive endodermal derivative changed the fate to cardiac mesoderms (2). More importantly, Sox17, which regulates the transcription of endodermal genes, has been shown to be a downstream target of β-catenin (10, 40). Together, these studies support the hypothesis that the TGF-β/Smad2 and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways may be essential in the induction of the definitive endoderm (8, 41) and suggest that UPR actives smad2 and Wnt/β-catenin to induce the specification of the definitive endoderm from ESCs.

The ER provides a unique environment for the production of secretory and membrane proteins and processing of unfolded, misfolded, degenerated, and mutated proteins (15). Recent findings indicate that ER stress might alter gene expression beyond protein folding (34). The ER stress inducers TG and TM are able to enhance the expression of differentiation genes in addition to genes encoding secretory polypeptides, membrane proteins, and growth factors (18–20). A recent study showed that some extracellular matrix components are necessary for definitive endoderm differentiation from ESCs (42). Furthermore, there are several reports addressing the intracellular compartment of protein folding, which happens in the ERs of stem and progenitor cells, in controlling cell fate decisions, especially under stress to restore the equilibrium between ER load and protein folding efficiency (14, 43, 44). Therefore, we think that ER stress could change the expression of some genes controlling and determining the specification of the endoderm. In summary, our data indicate that ER stress-mediated UPR is requisite for the specification of endoderm cell fate in early embryonic development via the synthesis and translocation of β-catenin from the cytoplasm to nuclei and transient activation of Smad2. Definitive endoderms derived from ESCs eventually can give rise to the internal organs, including the liver and the pancreas. Further understanding of the controlling mechanisms of cell fate divisions of stem cells will be helpful for the development of new treatment regimens for patients who currently do not have many therapeutic options.

This work was supported by grants from the National Basic Research Program of China (2012CB967903, 2012CB966800, and 2013CB945600), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81270438, 81130038, and 81372189), Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (Pujiang program), Shanghai Health Bureau Key Discipline and Specialty Foundation (J50208), Shanghai Education Committee Key Discipline and Specialty Foundation, and KC Wong Foundation.

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- UPR

- unfolded protein response

- ESC

- ES cell

- mESC

- mouse ES cell

- EB

- embryoid body.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lewis S. L., Tam P. P. (2006) Definitive endoderm of the mouse embryo: formation, cell fates, and morphogenetic function. Dev. Dyn. 235, 2315–2329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lickert H., Kutsch S., Kanzler B., Tamai Y., Taketo M. M., Kemler R. (2002) Formation of multiple hearts in mice following deletion of β-catenin in the embryonic endoderm. Dev. Cell 3, 171–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Morrison G. M., Oikonomopoulou I., Migueles R. P., Soneji S., Livigni A., Enver T., Brickman J. M. (2008) Anterior definitive endoderm from ESCs reveals a role for FGF signaling. Cell Stem Cell 3, 402–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li F., He Z., Li Y., Liu P., Chen F., Wang M., Zhu H., Ding X., Wangensteen K. J., Hu Y., Wang X. (2011) Combined activin A/LiCl/Noggin treatment improves production of mouse embryonic stem cell-derived definitive endoderm cells. J. Cell Biochem. 112, 1022–1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hansson M., Olesen D. R., Peterslund J. M., Engberg N., Kahn M., Winzi M., Klein T., Maddox-Hyttel P., Serup P. (2009) A late requirement for Wnt and FGF signaling during activin-induced formation of foregut endoderm from mouse embryonic stem cells. Dev. Biol. 330, 286–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sui L., Bouwens L., Mfopou J. K. (2013) Signaling pathways during maintenance and definitive endoderm differentiation of embryonic stem cells. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 57, 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu Y., Festing M., Thompson J. C., Hester M., Rankin S., El-Hodiri H. M., Zorn A. M., Weinstein M. (2004) Smad2 and Smad3 coordinately regulate craniofacial and endodermal development. Dev. Biol. 270, 411–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kubo A., Shinozaki K., Shannon J. M., Kouskoff V., Kennedy M., Woo S., Fehling H. J., Keller G. (2004) Development of definitive endoderm from embryonic stem cells in culture. Development 131, 1651–1662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Conlon F. L., Lyons K. M., Takaesu N., Barth K. S., Kispert A., Herrmann B., Robertson E. J. (1994) A primary requirement for nodal in the formation and maintenance of the primitive streak in the mouse. Development 120, 1919–1928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Engert S., Burtscher I., Liao W. P., Dulev S., Schotta G., Lickert H. (2013) Wnt/β-catenin signalling regulates Sox17 expression and is essential for organizer and endoderm formation in the mouse. Development 140, 3128–3138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yoshikawa Y., Fujimori T., McMahon A. P., Takada S. (1997) Evidence that absence of Wnt-3a signaling promotes neuralization instead of paraxial mesoderm development in the mouse. Dev. Biol. 183, 234–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gadue P., Huber T. L., Paddison P. J., Keller G. M. (2006) Wnt and TGF-β signaling are required for the induction of an in vitro model of primitive streak formation using embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 16806–16811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kim P. T., Ong C. J. (2012) Differentiation of definitive endoderm from mouse embryonic stem cells. Results Probl. Cell Differ. 55, 303–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hetz C. (2012) The unfolded protein response: controlling cell fate decisions under ER stress and beyond. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 89–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Boyce M., Yuan J. (2006) Cellular response to endoplasmic reticulum stress: a matter of life or death. Cell Death Differ. 13, 363–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kaufman R. J., Back S. H., Song B., Han J., Hassler J. (2010) The unfolded protein response is required to maintain the integrity of the endoplasmic reticulum, prevent oxidative stress and preserve differentiation in β-cells. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 12, 99–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang P., McGrath B., Li S., Frank A., Zambito F., Reinert J., Gannon M., Ma K., McNaughton K., Cavener D. R. (2002) The PERK eukaryotic initiation factor 2 α kinase is required for the development of the skeletal system, postnatal growth, and the function and viability of the pancreas. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 3864–3874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Reimold A. M., Etkin A., Clauss I., Perkins A., Friend D. S., Zhang J., Horton H. F., Scott A., Orkin S. H., Byrne M. C., Grusby M. J., Glimcher L. H. (2000) An essential role in liver development for transcription factor XBP-1. Genes Dev. 14, 152–157 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Luo S., Mao C., Lee B., Lee A. S. (2006) GRP78/BiP is required for cell proliferation and protecting the inner cell mass from apoptosis during early mouse embryonic development. Mol. Cell Biol. 26, 5688–5697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wu J., Kaufman R. J. (2006) From acute ER stress to physiological roles of the unfolded protein response. Cell Death Differ. 13, 374–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Iwakoshi N. N., Lee A. H., Glimcher L. H. (2003) The X-box binding protein-1 transcription factor is required for plasma cell differentiation and the unfolded protein response. Immunol. Rev. 194, 29–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tsang K. Y., Chan D., Cheslett D., Chan W. C., So C. L., Melhado I. G., Chan T. W., Kwan K. M., Hunziker E. B., Yamada Y., Bateman J. F., Cheung K. M., Cheah K. S. (2007) Surviving endoplasmic reticulum stress is coupled to altered chondrocyte differentiation and function. PLoS Biol. 5, e44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Smith A. G., Hooper M. L. (1987) Buffalo rat liver cells produce a diffusible activity which inhibits the differentiation of murine embryonal carcinoma and embryonic stem cells. Dev. Biol. 121, 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xu H., Tsang K. S., Chan J. C., Yuan P., Fan R., Kaneto H., Xu G. (2013) The combined expression of Pdx1 and MafA with either Ngn3 or NeuroD improves the differentiation efficiency of mouse embryonic stem cells into insulin-producing cells. Cell Transplant 22, 147–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li L., Sun L., Gao F., Jiang J., Yang Y., Li C., Gu J., Wei Z., Yang A., Lu R., Ma Y., Tang F., Kwon S. W., Zhao Y., Li J., Jin Y. (2010) Stk40 links the pluripotency factor Oct4 to the Erk/MAPK pathway and controls extraembryonic endoderm differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 1402–1407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xu H. M., Liao B., Zhang Q. J., Wang B. B., Li H., Zhong X. M., Sheng H. Z., Zhao Y. X., Zhao Y. M., Jin Y. (2004) Wwp2, an E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets transcription factor Oct-4 for ubiquitination. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 23495–23503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fuerer C., Nusse R. (2010) Lentiviral vectors to probe and manipulate the Wnt signaling pathway. PLoS ONE 5, e9370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yang L., Carlson S. G., McBurney D., Horton W. E., Jr. (2005) Multiple signals induce endoplasmic reticulum stress in both primary and immortalized chondrocytes resulting in loss of differentiation, impaired cell growth, and apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 31156–31165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ulianich L., Garbi C., Treglia A. S., Punzi D., Miele C., Raciti G. A., Beguinot F., Consiglio E., Di Jeso B. (2008) ER stress is associated with dedifferentiation and an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition-like phenotype in PC Cl3 thyroid cells. J. Cell Sci. 121, 477–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gardner R. L. (1982) Investigation of cell lineage and differentiation in the extraembryonic endoderm of the mouse embryo. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 68, 175–198 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wells J. M., Melton D. A. (1999) Vertebrate endoderm development. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 15, 393–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yasunaga M., Tada S., Torikai-Nishikawa S., Nakano Y., Okada M., Jakt L. M., Nishikawa S., Chiba T., Era T. (2005) Induction and monitoring of definitive and visceral endoderm differentiation of mouse ESCs. Nat. Biotechnol. 23, 1542–1550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Urano F., Wang X., Bertolotti A., Zhang Y., Chung P., Harding H. P., Ron D. (2000) Coupling of stress in the ER to activation of JNK protein kinases by transmembrane protein kinase IRE1. Science 287, 664–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kawai T., Fan J., Mazan-Mamczarz K., Gorospe M. (2004) Global mRNA stabilization preferentially linked to translational repression during the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 6773–6787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Derynck R., Akhurst R. J., Balmain A. (2001) TGF-β signaling in tumor suppression and cancer progression. Nat. Genet. 29, 117–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ijichi H., Otsuka M., Tateishi K., Ikenoue T., Kawakami T., Kanai F., Arakawa Y., Seki N., Shimizu K., Miyazono K., Kawabe T., Omata M. (2004) Smad4-independent regulation of p21/WAF1 by transforming growth factor-β. Oncogene 23, 1043–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gordon M. D., Nusse R. (2006) Wnt signaling: multiple pathways, multiple receptors, and multiple transcription factors. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 22429–22433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. D'Amour K. A., Agulnick A. D., Eliazer S., Kelly O. G., Kroon E., Baetge E. E. (2005) Efficient differentiation of human embryonic stem cells to definitive endoderm. Nat. Biotechnol. 23, 1534–1541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kelly O. G., Pinson K. I., Skarnes W. C. (2004) The Wnt co-receptors Lrp5 and Lrp6 are essential for gastrulation in mice. Development 131, 2803–2815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sinner D., Rankin S., Lee M., Zorn A. M. (2004) Sox17 and β-catenin cooperate to regulate the transcription of endodermal genes. Development 131, 3069–3080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Toivonen S., Lundin K., Balboa D., Ustinov J., Tamminen K., Palgi J., Trokovic R., Tuuri T., Otonkoski T. (2013) Activin A and Wnt-dependent specification of human definitive endoderm cells. Exp. Cell Res. 319, 2535–2544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Taylor-Weiner H., Schwarzbauer J. E., Engler A. J. (2013) Defined extracellular matrix components are necessary for definitive endoderm induction. Stem Cells 31, 2084–2094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Treglia A. S., Turco S., Ulianich L., Ausiello P., Lofrumento D. D., Nicolardi G., Miele C., Garbi C., Beguinot F., Di Jeso B. (2012) Cell fate following ER stress: just a matter of “quo ante” recovery or death? Histol. Histopathol. 27, 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lin J. H., Li H., Yasumura D., Cohen H. R., Zhang C., Panning B., Shokat K. M., Lavail M. M., Walter P. (2007) IRE1 signaling affects cell fate during the unfolded protein response. Science 318, 944–949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]