Background: SENSITIVE TO FREEZING 2 (SFR2) is classified as a glycosyl hydrolase, and by using glycosyltransferase activity, it modifies membrane lipids to promote freeze tolerance.

Results: Although the active site of SFR2 is identical to hydrolases, adjacent loop regions contribute to its transferase activity.

Conclusion: Transferase activity evolved by modifications external to the core catalytic site.

Significance: Defined structure-function relationships will inform engineering of transferases and freeze tolerance.

Keywords: Chloroplast, Glycosidase, Glycosyltransferase, Hydrolase, Membrane Turnover, Stress Response, Freezing, Glycosyl Hydrolase, Oligogalactolipid, Transferase

Abstract

SENSITIVE TO FREEZING 2 (SFR2) is classified as a family I glycosyl hydrolase but has recently been shown to have galactosyltransferase activity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Natural occurrences of apparent glycosyl hydrolases acting as transferases are interesting from a biocatalysis standpoint, and knowledge about the interconversion can assist in engineering SFR2 in crop plants to resist freezing. To understand how SFR2 evolved into a transferase, the relationship between its structure and function are investigated by activity assay, molecular modeling, and site-directed mutagenesis. SFR2 has no detectable hydrolase activity, although its catalytic site is highly conserved with that of family 1 glycosyl hydrolases. Three regions disparate from glycosyl hydrolases are identified as required for transferase activity as follows: a loop insertion, the C-terminal peptide, and a hydrophobic patch adjacent to the catalytic site. Rationales for the effects of these regions on the SFR2 mechanism are discussed.

Introduction

SENSITIVE TO FREEZING 2 (SFR2) is an enzyme located on the chloroplast envelope membrane that was shown to be necessary for freezing tolerance in cold-acclimated Arabidopsis thaliana (1). By sequence similarity, SFR2 was classified as a family 1 glycosyl hydrolase (GH1)2 (2). However, it was recently shown to have transferase activity (3). Specifically, it was shown to remove the galactose headgroup from chloroplast-specific lipid monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG) and transfer it to either a second MGDG or to an oligogalactolipid with two or three galactosyl moieties (di- or trigalactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG or TGDG)), thus increasing the number of galactosyl moieties in a processive manner both in vivo and in vitro (3). It was hypothesized that action of SFR2 during freezing is necessary to stabilize the chloroplast membrane both by increasing the hydration of the membrane and by adjusting the ratio of bilayer-forming to non-bilayer-forming lipids (4).

GH1s are a structurally related group of presumed functionally similar enzymes that catalyze removal of a sugar group while retaining the anomeric configuration of the sugar at carbon 1 (C1) (EC 3.2.1) (5). Structurally, they adopt a (β/α)8 or “α/β” barrel protein fold, also known as a triose-phosphate isomerase barrel, with loop regions conferring substrate specificity and modulating activity (6). Identified in many organisms, GH1 family proteins have always been found to have hydrolase activity, until the discovery of SFR2 and two additional GH1s described as transferases in plants as follows: Oryza sativa (rice) Os9BGlu31 synthesizes phytohormone glycoconjugates (7), and Dianthus caryophyllus (carnation) AA5GT glucosylates anthocyanin (8). The naturally occurring structural changes required to mechanistically convert a hydrolase into a structurally similar transferase are unknown (9). The evolution of this mechanism change is of interest because glycosyltransferases have the potential to make industrially useful oligosaccharides. The interest in these enzymes has already inspired efforts to convert hydrolases into transferases (10).

The mechanism of SFR2 transferase activity is of particular interest because of its role in freezing tolerance. Enhancing freezing tolerance of crop plants has agricultural value (11), and SFR2 is a potential tool. Protein and transcript levels of SFR2 do not appear to change upon cold acclimation; instead, SFR2 appears to be constitutively present (12). However, its products are not detectable prior to freezing conditions (3), i.e. the enzyme is likely to be activated post-translationally upon cellular detection of freezing. The nature of this activation is still unknown. Determining the structural basis for SFR2 transferase activity would allow targeting of specific regions of SFR2 for future design of constitutively active SFR2 versions for freeze tolerance engineering.

Here, the relationship between structure and function of SFR2 is investigated. SFR2 has little or no hydrolase activity under the optimal conditions for transferase activity. To understand the structural basis for SFR2 reaction specificity, its three-dimensional atomic structure is modeled using the crystal structures of other GH1 enzymes as templates. In doing so, a strategy was developed to yield higher confidence models. This strategy is applicable to other (β/α)8 barrel protein homology modeling efforts, and likely it will be applicable to other protein structures in which the enzyme core is conserved, although loops associated with substrate selectivity are more variable in sequence. The SFR2 model surprisingly yields a catalytic site identical in sequence and similar in architecture to that of GH1s with hydrolase but no transferase activity. Three regions of SFR2 dissimilar from other GH1s are shown to be necessary for transferase activity on its native galactosyldiacylglycerol substrates. Their relationship to galactolipid transferase activity and processivity is analyzed by modeling the substrate-enzyme complex.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Alignment and Selection of Crystal Structure Templates for Modeling the SFR2 Structure

Crystal structures as potential templates for modeling the three-dimensional atomic structure of A. thaliana SFR2 were identified using NCBI BLAST (www.blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov; see Ref. 13), Swiss Model Template Identification (14), and SALIGN (15) and then downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (16). These search engines were used because each has a unique ranking system for candidates. Top candidates identified by each program were then compared manually with preference given to candidates with higher sequence identity to SFR2, particularly in GH1 motifs and catalytic residues, and the best coverage of the entire (β/α)8 barrel. This method identified Sulfolobus solfataricus PDB entry 1UWT, a β-glycosidase in complex with d-galactohydroximo-1,5-lactam (17) and Rauvolfia serpentina PDB entry 4A3Y, a raucaffricine glucosidase (18) as the best structural templates for the barrel region of the protein.

Next, the best structural models for individual loops of SFR2 were identified. Candidates were identified in two ways. First, candidates identified from the original searches with the entire SFR2 sequence were reconsidered at the loop level. Second, additional candidates were identified by submitting sequences of the loop regions or of loop regions including flanking core elements, to NCBI DELTA-BLAST (modified for short input sequences), the Global Trace Graph server for remote homology detection (19), and SALIGN. All candidates were screened manually within loop regions for the highest identity and closest length matches to SFR2. A structural overlay of the template sequences created using the DALI server (20) was used to verify that template regions identified as similar to SFR2 loops were loop structures in the template. The highest scoring template candidates included the following: S. solfataricus PDB entry 1UWT (17) and R. serpentina PDB entry 4A3Y (18), and also included Thermosphaera aggregans PDB entry 1QVB, a hyperthermophilic β-glycosidase (21); Paenibacillus polymyxa PDB entry 2JIE, a β-glucosidase B in complex with 2-fluoroglucose (22); and Triticum aestivum PDB entry 2DGA, a β-d-glucosidase in complex with glucose (23).

Initial sequence alignments generated by Swiss Model were manually edited to incorporate short regions of better alignment from SALIGN or BLAST as appropriate. They were then manually compiled into a multiple sequence alignment such that the majority of the (β/α)8 barrel GH1 motifs were aligned with 1UWT or 4A3Y, although loops of SFR2 were aligned with corresponding loops from the best loop templates.

Structural Modeling with MODELLER Followed by Refinement and Energy Minimization

With the final alignment of template sequences, three high scoring homology models were generated by using Modeler with the EasyModeller interface (24–26), and they are provided as supporting PDB-formatted files named SFR2_1, SFR2_2, SFR2_3. The structures of each are similar in core regions but diverge in loop regions, particularly loop A (residues 67–157). Refinement of loop A was attempted using ModLoop (27, 28), which predicts loop folding based on spatial restraints instead of homology. However, resulting structures were not improved, as judged by structure quality assessments (see below for methodological details). Further improvements of the model proceeded using SFR2_2, which had the best structure quality (see below for methodological details). Given the near identity of the SFR2 and 1UWT sequences in the catalytic core, several active-site side chains and a short segment of main chain at His-223 were repositioned manually by using dihedral angle rotation in PyMOL version 1.4 (29), to more closely match 1UWT. Ser-224, a nonactive site residue with uncertain main-chain position, was removed from the model to allow the main chain of His-223 to adopt the GH1-conserved position in the active site. Finally, the entire structure was energy-minimized using the YASARA energy minimization server (30).

Model Validation for Favorable Stereochemistry and Chemical Contacts

Favorability of intramolecular chemical contacts and deviation from similar structures were assessed using ModEval and Swiss Model Structure Assessment. From these, the GA341 score (ModEval; see Ref. 31), which assesses surface accessibility and distance-dependent statistical potentials, and the Qmean6 Z-score (Swiss Model; see Refs. 32, 33), a composite score including potentials for distance-dependent chemical interaction, solvation, and torsion angle, are reported in Table 1. Main-chain and side-chain dihedral angle favorability was assessed using ProCheck from the PDBsum Generate server. From ProCheck, the percentage of main-chain dihedral angles within the favored, allowed, or disallowed region of the Ramachandran plot and the overall bond stereochemistry G scores were used as measures of stereochemical quality in the SFR2 model; see Table 1. Finally, interatomic contacts were assessed using the MolProbity server with electron-cloud optimized hydrogen positions (35), and the resulting clash scores (measuring the number of significant van der Waals overlaps per 1000 atoms) are given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

SFR2 model assessment scores

The first and second panels list the type of assessment and the value reported. Abbreviations used are as follows: ND, not determined. SFR2_1, SFR2_2, and SFR2_3 are the direct Modeller outputs, as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

| Assessment | SFR2_1 | SFR2_2 | SFR2_3 | SFR2_2 Energy-minimized | SFR2_2 MGDG-bound | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ProCheck | G-factor | −0.23 | −0.19 | −0.31 | −0.04 | −0.02 |

| Ramachandran | Core | 83.7 | 83.7 | 82.5 | 84.3 | 81.7 |

| Allowed | 13.7 | 12.7 | 13.2 | 12.4 | 15.9 | |

| Generously allowed | 1.2 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 1.7 | |

| Disallowed | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 0.7 | |

| SwissModel | Z-score | −2.25 | −1.91 | −2.23 | −1.90 | −2.26 |

| ModEval | GA341 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ND | ND |

| MolProbity | Clash score | 116.1 | 131.1 | 138.0 | 0.78 | 0.52 |

| YASARA | Energy (kJ/mol) | ND | 38,803 | ND | −214,987 | −218,476 |

Substrate Modeling in the SFR2 Active Site

Following protein superimposition of the highly conserved 1UWT catalytic site with SFR2, the three-dimensional structure of MGDG was placed into SFR2 by superimposition of its galactose headgroup with the corresponding d-galactohydroximo-1,5-lactam moiety in 1UWT. To accommodate MGDG, two nonconserved active site residues in SFR2 (Arg-400 and His-335) were rotated to low energy (close to rotameric) configurations. Similarly, the highly flexible acyl chains of MGDG were rotated to avoid van der Waals collisions with the protein and to interact favorably with the protein. Because acyl chain flexibility increases with chain length, docking was performed with six-carbon acyl chains. The docked MGDG-SFR2 model was submitted for two rounds of energy minimization using the YASARA energy minimization server (30), which performed bond rotations within the ligand and protein to improve interactions. ββ-DGDG was then docked using the MGDG-bound model as a starting point, including repositioned active site residues. ββ-DGDG was placed by superimposition of its outermost sugar moiety with the sugar headgroup of the MGDG, and the result was energy-minimized.

Determining Evolutionary Conservation of β-Glycosidases

Evolutionary-based residue conservation was analyzed in a three-dimensional structural context by using ConSurf (36–38). For a given query sequence, e.g. SFR2, ConSurf constructs a multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree, selecting sequences evenly across evolutionary time, and then maps the relative conservation of sequence positions onto the three-dimensional structure. The chloroplast-specific cpREV option was used to model residue substitution probabilities.

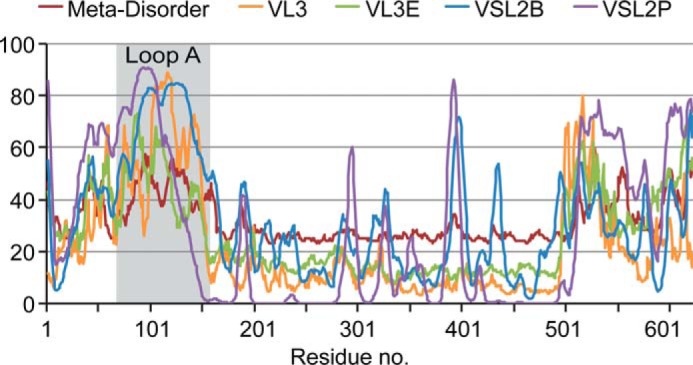

Disorder Prediction

Intrinsic disorder within the SFR2 structure was predicted using multiple prediction programs. Disorder prediction programs have variable accuracy and differ in the physicochemical properties predicted. Thus, it has been suggested that using multiple predictors is superior in defining true disordered regions rather than consideration of a single predictor alone (39). The Meta-Disorder predictor (40) from the Predict Protein server was used, as it combines outputs from four original programs, NORSnet (41), DISOPRED2 (42), PROFbval (43), and Ucon (44), into a conservative estimate of disordered regions. Furthermore, a suite of programs available from the Database of Protein Disorder was used. VL3 is a predictor that measures 20 attributes of residues commonly found in intrinsically disordered regions (45). VL3E uses the core functions of VL3 but expands the training set of intrinsically disordered regions to include additional proteins evolutionarily conserved with the original training set. VSL2P and VSL2B predictors were also used, as they were shown to have improved predictive capacity compared with other predictors on both long and short regions of disorder (46, 47).

Graphics Preparation

Graphic images presented in the figures were prepared using a combination of the PyMOL molecular graphics system, version 1.4 (29), using the hollow script (a plug-in to PyMOL) to visualize protein cavities/surfaces (48) and Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator software to annotate the figures.

Protein Production

SFR2 template cloning was described previously (3). The sequence of SFR2 can be found in the GenBankTM/EMBL data libraries under accession AEE74404. Truncation and loop exchange constructs were similarly PCR-amplified and then inserted into pYES2.1 using the pYES2.1/V5 TOPO TA yeast expression kit (Invitrogen) protocol. Fragments of loop exchange constructs were assembled using Gibson Assembly Master Mix (New England Biolabs). SFR2 point mutants were generated using Phusion (Thermo Scientific) and DpnI (New England Biolabs) or with the Q5 site-directed mutagenesis kit (New England Biolabs). Point mutants of SFR2 are named by the position of the mutation in the amino acid sequence, e.g. E267A is a mutation of glutamate 267 to alanine. Truncations of SFR2 are named for the first (N-terminal) or last (C-terminal) residue of SFR2 remaining in the construct, followed by the terminus designation of N or C, e.g. 27N is truncated at the N terminus of SFR2, with residue 27 being the first residue present from the original SFR2 sequence. Loop 1 and loop 2 constructs replace loop A (residues 67–157) with the equivalent loop from S. solfataricus (loop 1) or with a known β-turn from an artificially constructed (β/α)8 barrel, KQFARH (loop 2, see Ref. 49). Template for S. solfataricus was synthesized including the Trp-33 to Gly mutation shown to induce allosteric control, PDB code 4EAM (50). All DNA products were sequenced at the MSU RTSF facility and shown to be correct prior to protein production. Primers are given in Table 2. Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain InvSc1 (Invitrogen) was transformed using the Frozen-EZ Yeast Transformation II kit (Zymo Research) as per instructions. Transformation was with SFR2 constructs alone or simultaneously with MGDG synthase 1 (MGD1) in pESC-His (51) as indicated.

TABLE 2.

Primers used for SFR2 cloning

F/R means forward/reverse; term is terminal.

| No. | Name | F/R | Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SFR2 full | F | CACCATGGAATTATTCGCATTGTTAA |

| 2 | SFR2-HIS full | R | AGTCAATGATGATGATGATGATGGCCGTCAAAGGGTGAGGCTAAAG |

| 3 | 27N-term SFR2 | F | TCATGTCTCGTTTCCGTCGCCAGAATCTC |

| 4 | 550C-term His | R | AGTCAATGATGATGATGATGATGTGCGTACATAAGATTATGATTATCAACG |

| 5 | 581C-term His | R | AGTCAATGATGATGATGATGATGACTCAACGGGTCTTGAAGACCATCC |

| 6 | E267A | F | GACTCTTGGGTAACATTTAATGCACCCCATATCTTCACCATG |

| 7 | E267A | R | CATGGTGAAGATATGGGGTGCATTAAATGTTACCCAAGAGTC |

| 8 | E429A | F | GTTCCTTTTATCGTCACAGCAAATGGCGTGTCTGATGAA |

| 9 | E429A | R | TTCATCAGACACGCCATTTGCTGTGACGATAAAAGGAAC |

| 10 | Y377A | F | CATCAACTACGCTGGACAGGAAGCAGTGTG |

| 11 | Y377A | R | CCTATGAAATCCAACTTCTC |

| 12 | I270A | F | GTAACATTTAATGAACCCCATGCTTTCACCATGCTTACCTACATG |

| 13 | I270A | R | CATGTAGGTAAGCATGGTGAAAGCATGGGGTTCATTAAATGTTAC |

| 14 | M273A | F | GAACCCCATATCTTCACCGCTCTTACCTACATGTGTGG |

| 15 | M273A | R | CCACACATGTAGGTAAGAGCGGTGAAGATATGGGGTTC |

| 16 | L274A | F | CCCATATCTTCACCATGGCTACCTACATGTGTGGATC |

| 17 | L274A | R | GATCCACACATGTAGGTAGCCATGGTGAAGATATGGG |

| 18 | I270M273L274A | F | TGCTTTCACCGCAGCCACCTACATGTGTG |

| 19 | I270M273L274A | R | TGGGGTTCATTAAATGTTAC |

| 20 | SFR2N | F | GGAATATTAAGCTCGCCATGGAATTATTCGCATTG |

| 21 | SFR2N | R | GCCTGACTAGCTAACCCAAAGAAGAATTTTC |

| 22 | 4EAM2 | F | GGTTAGCTAGTCAGGCTGGATTCCAG |

| 23 | 4EAM2 | R | TTCTTTGTCCTTGTAGTTTCCCCAGTATCC |

| 24 | SFR2C | F | AACTACAAGGACAAAGAAGTGAAGCTAGC |

| 25 | SFR2C | R | CCGAGGAGAGGGTTATCAATGATGATGATGATGATG |

| 26 | SFR2N_KQF | F | GGAATATTAAGCTCGCCATGGAATTATTCGCATTGTTAAT |

| 27 | SFR2N_KQF | R | TGTCTAGCGAACTGCTTAGCTAACCCAAAGAAGAATTTTCC |

| 28 | ARH_SFR2C | F | AGCAGTTCGCTAGACATGACAAAGAAGTGAAGCTAGC |

| 29 | ARH_SFR2C | R | CCGAGGAGAGGGTTATCAATGATGATGATGATGATG |

Protein production was essentially according to pYES2.1 manufacturer instructions (Invitrogen). Briefly, minimal media cultures were inoculated from fresh yeast colonies on minimal media and grown at 30 °C with 275 rpm for 20 h. Then the A600 was normalized to 0.5, and the culture was transferred to rich media supplemented with galactose for 8 h. Because mutated proteins sufficiently destabilized to trigger the yeast unfolded protein response are not stably expressed (52), production of all SFR2 variants was tested with the same protein production protocol used for wild-type SFR2. Cell pellets were harvested, frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −80 °C until use. Pellets were thawed on ice, and microsomes were harvested essentially as described (53) and either used immediately or stored at −80 °C until use.

Protein analysis was by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting as per the Bio-Rad manual. Primary antisera against the N or C terminus of SFR2 or a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of each as specified in the figure legend at a concentration of 1:1000 was applied overnight. The secondary antisera used was HRP-linked (Bio-Rad) and was detected using Clarity ECL reagent as per instructions (Bio-Rad).

SFR2 Assays

SFR2 assays were modified from Ref. 3 as follows: MGDG was acquired from Avanti Polar Lipids; the reaction buffer was adjusted as indicated in figure legends to have various pH values buffered by Tris-HCl or various ion concentrations of MgCl2, MnCl2, CaCl2, KCl, VSO4, NiSO4, CuCl2, or CoCl2. Reactions were started by adding 15 μg of protein equivalent microsomes followed by brief sonication, incubated for 30 min, then stopped by adding 600 μl of methanol/chloroform/formic acid (2:1:0.1, v/v/v) followed by vortexing. Alditol acetates were measured as described previously (54). For assays with other lipids, 30 nmol/reaction ββ-DGDG was purified from SFR2-expressing yeast; 50 nmol/reaction lyso-MGDG was made from Rhizopus lipase digestion of MGDG (Avanti Polar Lipids) and then purified as described previously (55), or 30 nmol/reaction αβ-DGDG was purchased (Avanti Polar Lipids, Larodan Fine Chemicals).

Uncompromised Structure Verification

Equal protein levels of yeast microsomes containing SFR2 constructs (30 μg) were untreated or boiled in the presence of 1% (v/v) Triton X-100. These samples were then digested with or without 20 μg/ml final volume of freshly prepared trypsin (Sigma) for 30 min on ice. All reactions were stopped by addition of 60 μg/ml final volume of soy trypsin inhibitor (Sigma), and proteins were precipitated by acetone, resuspended in Laemmli sample buffer, and then equal volumes were analyzed. Native PAGE analysis was performed essentially as described (56). Samples were prepared by extracting yeast pelleted from 1 ml of culture with an absorbance at 600 nm in 40 μl of native sample buffer containing 2% (w/v) final concentration of digitonin by beating with glass beads with intermittent chilling on ice. Unsolubilized material was precipitated by chilled centrifugation at 21,000 × g for 10 min prior to loading.

Lipid Analysis

Lipid analysis was done as described (3), except extractions included back-extraction with water-saturated butanol to avoid loss of more polar oligogalactolipid species, as described previously (57). The thin layer chromatography (TLC) liquid phases used were chloroform, methanol, 0.45% (w/v) NaCl in water (60:35:8, v/v/v), or chloroform/methanol/acetate/water (85:20:10:4, v/v/v/v). The precise masses of a subset of oligogalactolipids in yeast extracts were confirmed using a Waters Xevo G2-S ultraperformance liquid chromatography/time of flight instrument at the Michigan State University mass spectrometry core facility. Separation was done on a 10-cm Supelco C18 column using protocol of 50:50 (v/v) solvent A to solvent B changing to 100% solvent B over the course of 20 min. Solvent A was 10 mm ammonium acetate; solvent B was methanol/acetonitrile (75:25, v/v). Selected molecular species were further fragmented with a variable cone voltage at 30–60 eV. All mass data were analyzed using the MassLynx software suite.

Antisera Production and Purification

Residues 4–103 (N-SFR2) or residues 515–622 (C-SFR2) were inserted into vector pET28b and confirmed by sequencing. Proteins were produced in BL21(DE3) Escherichia coli. Cell pellets were disrupted by sonication to isolate inclusion bodies, which were solubilized in 8 m urea, and SFR2 antigens were purified by nickel affinity chromatography and ion exchange chromatography to a final purity above 95%. Antisera were raised in rabbits using the standard protocol at Cocalico Biologicals, Inc. Final bleeds were purified by affinity to their antigens using Affi-Gel-10 and Affi-Gel-15 (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Chloroplast Assays

A. thaliana of the Columbia ecotype, wild type, or sfr2–3 (3) were grown on Murashige and Skoog medium supplemented with 1% sucrose for 3–4 weeks on a 16-h light, 8-h dark cycle. Chloroplasts were isolated essentially as described previously (58). To test antibody accessibility, intact chloroplasts were incubated similarly to Ref. 59; in brief, 200 μg of chlorophyll equivalent chloroplasts at 0.4 mg/ml concentration were incubated with primary antibody (above) for 1 h in the dark, and intact chloroplasts were reisolated through a 40% Percoll cushion, washed with incubation buffer (50 mm Hepes-KOH, pH 7.3, 330 mm sorbitol), and then incubated with AlexaFluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen) for 1 h in the dark. Intact chloroplasts were again reisolated through a 40% Percoll cushion, washed with incubation buffer, and observed using a Leica DMRA2 epifluorescence microscope (60) or a Photon Technology International spectrofluorometer. Thermolysin digestion of intact chloroplasts was performed as described (61), except membranes were disrupted using digitonin.

RESULTS

SFR2 Is a Highly Specific Galactosyltransferase

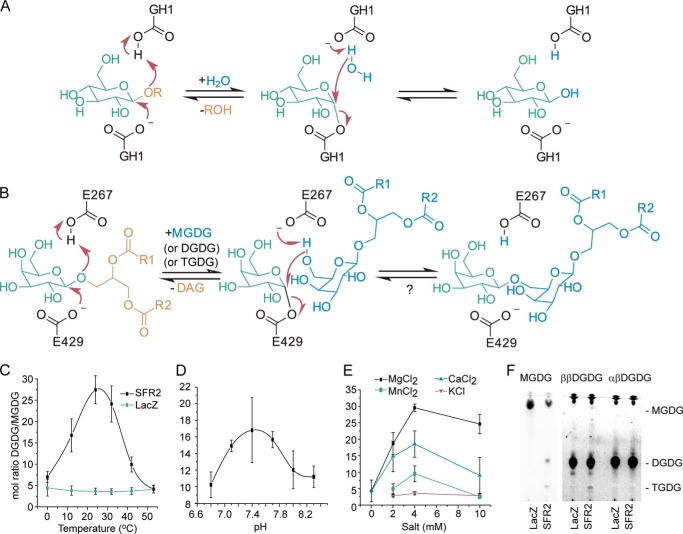

Glycosyl hydrolysis and transfer are in principle closely related activities and have been found to be carried out by the same enzyme (62, 63). The structural basis for predominant transferase rather than hydrolase activity has been suggested to be exclusion of water from the active site (62). As can be seen in Fig. 1A, the mechanism of a glycosyl hydrolase that retains the anomeric configuration of the sugar at position C1 involves a glycosyl-enzyme intermediate that is hydrolyzed by water. If water was excluded, and an alternate nucleophile entered the active site, transfer of the glycosyl moiety to the alternate nucleophile would occur, as is diagrammed in the suggested SFR2 reaction mechanism (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Proposed reaction mechanism and temperature, pH, and salt dependence of SFR2 activity. A, retaining mechanism of GH1. B, expected reaction mechanism of SFR2 with residue numbers of catalytic glutamates indicated. A question mark denotes the lack of observation of the expected back reaction. R1 and R2 are aliphatic chains of 15 or 17 carbons with or without desaturation at positions 9, 11, and 15. Microsomes isolated from S. cerevisiae producing SFR2 or LacZ were incubated with MGDG under a variety of temperatures (C), biologically relevant pH values (D), or salt concentrations (E) as indicated for 30 min. Lipids were extracted, and MGDG and DGDG were separated by thin layer chromatography, converted to fatty acid methyl esters, and quantified by gas chromatography. The ratio of DGDG (a product) to MGDG (a substrate) is shown with standard deviation bars, n ≥3. F, thin layer chromatogram of assays similar to those in C–E under optimal conditions with MGDG (substrate), ββ-digalactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG, product), or αβ-DGDG after 1 h. Chromatogram has been stained for sugars, and locations of MGDG, DGDG, and TGDG are indicated. A vertical white bar separates panels originally from the same TLC plate in which contrast settings have been increased on the right facilitate visualization of TGDG produced.

An assay to measure SFR2 galactosyltransferase activity was reported previously in which deoxycholate-solubilized substrate MGDG was supplied to microsomes purified from SFR2-producing yeast, and formation of product oligogalactolipids was measured (3). Here, optimal assay parameters for transferase activity were defined, as a prerequisite to measuring alternative activities. The temperature that resulted in the highest activity was ∼24 °C, although consistent with the role of SFR2 during freezing, activity was also detectable at 0 °C (Fig. 1C). At the optimal temperature, SFR2 activity was observed throughout the range of physiologically relevant pH values, with an optimum of ∼7.5 (Fig. 1D). At the optimal temperature and pH, activity of recombinant SFR2 was also tested for dependence on divalent cations, as galactosyltransferase activity in isolated chloroplasts was reported to increase when divalent cations were present (64). Indeed, activity in the absence of divalent cations was minimal, although Mg2+, Ca2+, or Mn2+ were all activating, with the strongest activation by Mg2+. Monovalent K+ was also activating, although not to the same extent as divalent cations above (Fig. 1E). Additionally, 4 mm each of V4+, Co2+, Ni2+, and Cu2+ was tested, but formation of oligogalactolipid product was not detectable in these assays. It should be noted that a small amount of sodium (0.4 mm) was present in all assays because it is the counter ion for deoxycholate. Use of alternative detergents, including CHAPS, also promoted SFR2 activity when divalent cations were supplied.

Using the optimal conditions for deoxycholate-mediated SFR2 activity, the specificity of SFR2 transferase activity was tested. First, occurrence of hydrolysis during the transferase assay was measured. Hydrolysis of MGDG by SFR2 would produce a novel product, free galactose. Thus, transferase products oligogalactolipids and hydrolase product free galactose were quantified in the same reactions, with galactose being quantified by the sensitive alditol acetate derivatization method (54, 65). SFR2 reactions were compared with those of LacZ (LACZ, gene name of E. coli β-galactosidase), a well studied galactosyl hydrolase that does not react with MGDG. During reactions with LacZ, −0.5 ± 1.0 nmol of oligogalactolipids and −0.15 ± 0.36 nmol of free galactose were produced during the assay. In comparison, SFR2 produced statistically significant levels of oligogalactolipids (8.0 ± 1.6 nmol, p < 0.002) but not of free galactose (0.08 ± 0.25 nmol, p = 0.45). To exclude the possibility that the transferase reaction conditions did not allow hydrolase activity, LacZ was or was not provided with a chromogenic substrate, 2-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG), under conditions identical to those above. The 2-nitrophenyl leaving group of ONPG is colored and absorbs light at 420 nm. During the course of the reaction, absorbance at 420 nm of the reaction with ONPG increased steadily, although the reaction without ONPG did not, indicating LacZ successfully hydrolyzed ONPG during the reaction and that the reaction conditions used are consistent with galactosyl hydrolase activity. Therefore, the production of oligogalactolipids by SFR2 and lack of production of free galactose together indicate that SFR2 is acting primarily as a transferase.

Second, substrate specificity of SFR2 in the transferase assay was tested. The two naturally occurring potential substrates most similar to MGDG are DGDG and lyso-MGDG, which has the same headgroup but only one fatty acid chain. In plants, there are two forms of DGDG. The major form under normal conditions has an α(1–6) linkage between the galactosyl groups, and the C1 carbon of the galactosyl directly attached to the diacylglycerol is in β-anomeric configuration (αβ-DGDG) (66). When SFR2 is active, a second form of DGDG is produced in which both galactosyl-C1 carbons are in the β-anomeric configuration (ββ-DGDG). When further extending the chain of galactose headgroups from two to three, SFR2 is likely to have activity only on its own product, ββ-DGDG, as all the C1 carbons of the galactosyl residues in TGDG produced in vivo are in the β-configuration (66). In vitro, the same holds true, as higher order galactolipid products derived from αβ-DGDG were undetectable, whereas small amounts of TGDG were produced in reactions with ββ-DGDG (Fig. 1E). Observation of TGDG was somewhat surprising as ββ-DGDG, the product of SFR2, was expected to produce MGDG through its reverse reaction, rather than TGDG through the forward reaction (Fig. 1B). Presumably, any MGDG produced was also immediately consumed to produce additional TGDG.

Less is known about the action of SFR2 on lyso-MGDG in vivo, partly because of its low abundance (67). Because GH1 family enzymes are frequently specific for the sugar group, and less frequently for the leaving group, lyso-MGDG is an attractive possible alternative substrate. To perform this experiment, lyso-MGDG was generated by lipase digestion from the same MGDG used as substrate, then purified and supplied to SFR2. However, products of a lyso-MGDG transferase reaction, oligogalactolysolipids, were not detectable. Considering the possibility that hydrolysis, rather than transferase activity, could occur with noncanonical substrates, two chromogenic substrates were tested, p-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucoside (PNPG) and ONPG. The leaving group of these substrates is colored, and therefore, if either hydrolase or transferase activity of SFR2 were active on these substrates, then absorbance of the leaving group would be detectable. This was observed for a positive control reaction with LacZ, but not for SFR2 under the same conditions. It was concluded that SFR specificity includes both a galactosyl moiety in which C1 carbons are in the β-anomeric configuration and at least some characteristics of the diacylglycerol leaving group.

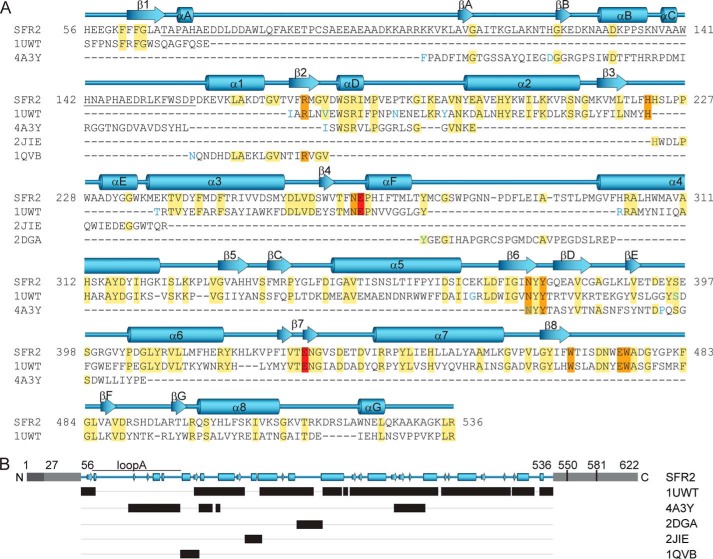

SFR2 Structural Modeling as a Framework for Understanding Substrate Interactions

To understand the origin of SFR2 substrate and transferase specificity, a homology model of the three-dimensional structure of SFR2 was constructed based on crystal structures of GH1 family members. Of the available crystal structures of GH1s, several were found with identity greater than or equal to 25% within the GH1 domain of SFR2 (residues 56–536). A previous study on the relationship between main-chain structural similarity and sequence identity indicates that 25% identity over at least 80 residues allows confidence that the main-chain structures are substantially similar, overlying a 2.5-Å root-mean-square deviation of αC positions (68). Of the potential templates, the GH1 with similarity throughout the entire (β/α)8 barrel and with the highest identity to SFR2 in the GH1 motifs and known catalytic residues is from Sulfolobus solfataricus (PDB code 1UWT), with 28% overall and 38% core identity. Thus, the 1UWT structure was chosen as the template for the majority of the model (Fig. 2). However, there were several loop regions of SFR2 with higher identity and fewer sequence gaps from alternative GH1 crystal structures. Because loops between core structure elements are known to be the origin of substrate specificity and interaction in GH1s (69), it was important to model SFR2 loop regions as accurately as possible. Thus, a second round of template analysis identified GH1s with the highest identity for individual loops between (β/α)8 barrel structural elements. The final template was constructed from multiple sequences and included 1UWT as the template for (β/α)8 barrel structural elements and loop regions from other GH1s where their sequences improved overall template identity (Fig. 2, A and B). This method is essentially similar to that used to build appropriate scaffolds for the mammalian serine proteases (70) and should be broadly applicable to other (β/α)8 barrel proteins. In a few regions of SFR2, sequences from multiple GH1s were included, particularly in regions where loops from other GH1s were spliced into the 1UWT template, to assist in defining structure near the loops similarly to described efforts based on multiple template modeling (71). In these regions, both templates were entered into Modeler, and an intermediate structure was derived. With this approach, the final assembly of modeling templates had 35% identity throughout its length (SFR2 residues 56–536, Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Alignment of SFR2 and homolog sequences used to build the three-dimensional structural model of SFR2. Amino acid sequence (A) is shown with SFR2 sequence numbering. Other family 1 glycosyl hydrolases are indicated by Protein Data Bank identifiers and are from the following species: S. solfataricus, 1UWT; R. serpentina, 4A3Y; T. aggregans, 1QVB; P. polymyxa, 2JIE; and T. aestivum, 2DGA. For space reasons, aligned template (1UWT and 4A3Y) sequences with insertions resulting in gaps greater than one residue in the SFR2 sequence are not shown. These positions are indicated by blue coloring of the following residue. Identical residues are highlighted in yellow, active site residues in orange, and acid/base catalyst glutamates in red. Secondary structure of the model is displayed above the sequence with (β/α)8 barrel helices and strands numbered sequentially, as per glycosyl hydrolase conventions. Additional helices and strands are lettered sequentially. Loop A, which is referred to specifically in the text, is underlined. The schematic representation in B, shows in black bars the ranges of residues in different structures that were used to construct the SFR2 structural model. Gray regions indicate portions of SFR2 not included in the model. Light gray portions have no known function, and dark gray indicates an identified transmembrane domain. Residue numbers for key features mentioned in the text are noted.

Validation of the Structural Model

Reliability of the SFR2 structural model was assessed using ProCheck, Swiss-Model, Modeler, and MolProbity tools. The probability that the overall fold was correct was greater than 95% as predicted from distance-dependent statistical potentials and surface accessibility by a GA341 score of 1.0 from Modeler (Table 2) (31). Favorability of the bond stereochemistry of residues was analyzed using multiple parameters. According to ProCheck, 84.3% of the main-chain dihedral angles of the residues were in the core Ramachandran regions, with an additional 15.3% in allowed regions, and only 0.5% in disallowed regions (34). This compares to 91.6, 8.2, and 0.2% for the main template structure 1UWT. The few SFR2 residues in disallowed Ramachandran regions were not near the active site but in or near external loop regions. Unfavorable atomic contacts were minimal, as reported by the clash score of MolProbity, which measures the number of steric overlaps of more than 0.4 Å per 1000 atoms. The SFR2 clash score was 0.78, which compares favorably with the relatively high score of 4.84 for 1UWT. Reliability of the predicted core structure was assessed visually by mapping Qmean-local scores from Swiss Model onto the model of SFR2 in Fig. 3, A and B. Qmean is a composite score including potentials for torsion angle, distance-dependent chemical interaction, and solvation (72). The (β/α)8 barrel fold encompassing most of the SFR2 active site has low Qmean scores (Fig. 3, A and B, blue), although several loops and the N and C termini have higher scores (Fig. 3, A and B, yellow and red), indicating the likelihood of increased model error in those regions. In summary, reliability assessments indicate that the core structure of the SFR2 model, including the catalytic site, should be close to its actual structure.

FIGURE 3.

Modeled structure of A. thaliana SFR2. A and B, ribbon diagram of the SFR2 structure is colored by qualitative model energy analysis (QMEAN) local scores (72) and is shown aligned to the structure of 1UWT (gray). The view in B is rotated by 90° about the x axis relative to the view in A. QMEAN scores by residue range from 0 to 10 and are composites of scores considering torsion angle potential over three consecutive amino acids, distance-dependent chemical interaction potential, predicted versus modeled secondary structure, and predicted versus modeled solvent accessibility. Helices and strands are labeled as in Fig. 2. Loop A is highlighted with a yellow halo and labeled. C and D, solvent-accessible molecular surface of SFR2, shown in the same orientations as A and B, is colored by residue hydrophobicity according to the scale in Ref. 74. Active site residues in the catalytic pocket of the enzyme are indicated by arrows.

Loop Structure

Increased model error in some SFR2 loop regions is almost certainly due to decreased similarity between those loops and the available crystal structures of GH1s, including 1UWT. The structure of 1UWT is shown as a gray overlay in Fig. 3, A and B. The overlay shows conservation of the (β/α)8 barrel fold and many loop regions between 1UWT and SFR2 and divergence for other loops. In particular, the loop region between the first (β/α)8 strand (β1) and first (β/α)8 helix (α1), residues 67–157, loop A, was modeled differently when testing different modeling and loop refinement protocols (see supplemental material, SFR2_1.pdb, SFR2_2.pdb, and SFR2_3.pdb). This region is longer in SFR2 than in crystallized GH1s, and thus a good template for the entire loop was not available (Fig. 2A, underlined region). The displayed model of loop A (yellow halo in Fig. 3, A and B) is one of three different conformations observed during modeling and should be considered a possible state.

The lack of constraints on loop A conformation suggested that loop A is an intrinsically disordered region. Intrinsically disordered regions of proteins have recently been recognized as a separate domain classification (73), which consists of peptides that do not autonomously fold into a single conformation. However, several types of disordered regions have been shown to adopt more specific conformations upon binding to other molecules or post-translational modification (73). Multiple predictors of intrinsic disorder were compared over the full length of SFR2 (Fig. 4). Regions of SFR2 in or near loop A have intrinsic disorder according to all of the predictors. A region between residues 500 and 525 may also be intrinsically disordered.

FIGURE 4.

Intrinsic disorder within SFR2. Multiple software packages were used to predict intrinsically disordered regions within SFR2. Outputs of these programs were normalized for display on the same scale. Increasing values indicate an increased probability of intrinsic disorder. Residues in loop A are indicated by gray background.

Relative Position of SFR2 to the Membrane

The substrates and products of SFR2 are membrane constituents. It has been hypothesized that SFR2 transferase specificity is maintained because SFR2 is tightly associated with the membrane, thus excluding water from its active site (9). To explore the presence of highly hydrophobic faces of SFR2, the surface of the SFR2 model is colored by hydrophobicity in Fig. 3, C and D (74). An entire face of SFR2 does not show hydrophobicity, making it likely that the SFR2 active site is exposed to a cytosolic environment similar to other GH1s. However, there is a concentrated region of hydrophobicity in the loop between α4 and αF which could mediate interaction with hydrophobic acyl chains of substrates or products (Fig. 3C, lower left).

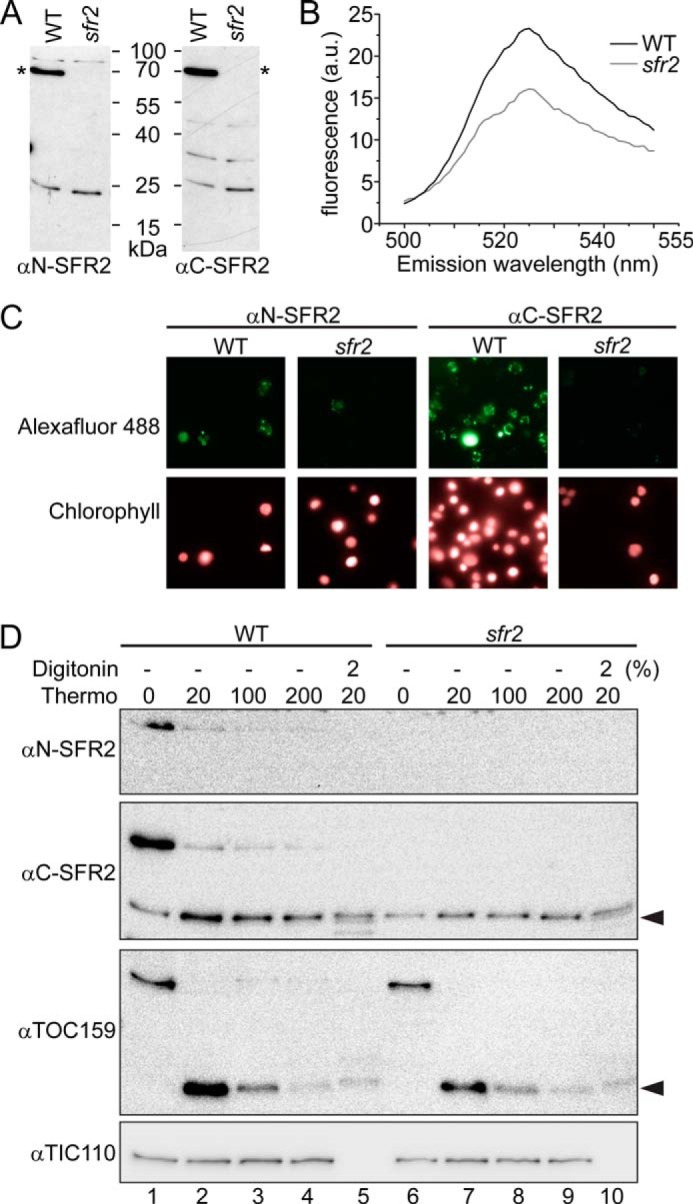

The N terminus of SFR2 was established as a chloroplast-targeting transmembrane domain by showing that, when fused to GFP, it tethered GFP stably to the chloroplast outer envelope (residues 1–27, see Fig. 2B) (12). In the same work, it was predicted that SFR2 may have a second transmembrane domain between residues 448 and 470. This prediction was based on positive results from transmembrane domain calculators and the presence of an SFR2 fragment protected from thermolysin digestion of isolated chloroplasts (12). However, if this region constitutes a second transmembrane domain, it would disrupt the seventh backbone helix (α7), displacing the eighth helix (α8) and strand (β8) to the other side of the membrane. Such a large disturbance would entirely disrupt the (β/α)8 barrel, and on that basis alone, a second transmembrane domain seems unlikely. To test whether α8 and β8 were displaced by a second transmembrane domain, antisera were raised against two SFR2 protein fragments produced heterologously from E. coli, residues 4–103 (αN-SFR2) and residues 515–622 (αC-SFR2). The antisera were purified until SFR2 was the primary antigen recognized by each (Fig. 5A). The purified antibodies were then applied individually to isolated wild type or sfr2 knock-out chloroplasts and detected using the fluorescence of AlexaFluor 488 attached to a secondary antibody. In chloroplasts treated with αC-SFR2, AlexaFluor fluorescence was higher in wild type than sfr2 by151 ± 31% (n = 4). A representative emission spectrum is shown in Fig. 5B. Similar results were seen for chloroplasts incubated with αN-SFR2 in which wild-type fluorescence was 1.7-fold ± 0.4 (n = 4) that of sfr2 chloroplasts. Micrographs of antibody-treated chloroplasts confirm the above observations and may indicate that SFR2 is not distributed evenly between isolated chloroplasts (Fig. 5C). Because the chloroplasts were isolated from whole plants, it is unclear whether distribution of SFR2 is tissue- or developmentally dependent. Together, the antibody accessibility data demonstrate that the C terminus of SFR2 is accessible from outside the chloroplast, a strong indicator that there is no second transmembrane domain.

FIGURE 5.

SFR2 has only one transmembrane domain. A, immunoblots of A. thaliana wild type or sfr2 protein extracts were probed with antisera raised against the N- or C-terminal amino acids of SFR2, as indicated. Asterisks indicate the location of SFR2. B, emission profile of AlexaFluor 488-labeled secondary antibody labeling chloroplasts decorated with antisera against SFR2 C terminus. Excitation wavelength is 488 nm. C, fluorescence micrographs of chloroplasts incubated first with antisera against the N or C terminus of SFR2 and then in a secondary antibody labeled with AlexaFluor 488. Numbers of chloroplasts present per panel is indicated by chlorophyll fluorescence. Magnifications shown are identical. D, immunoblots detected with antisera indicated at left of chloroplasts isolated from wild type or sfr2 A. thaliana and treated with or without thermolysin in the final concentrations (μg/ml) indicated and with or without the presence of digitonin in percentages indicated. Black arrowheads indicate regions of protein partially resistant to thermolysin.

The SFR2 antibody accessibility experiment above (Fig. 5, A–C) and the model itself (Fig. 3) appear to oppose the previous data showing that a portion of SFR2 is protected from thermolysin digestion by presence of the chloroplast outer envelope membrane (12). To test whether the previously observed SFR2 protein fragment was intrinsically thermolysin-resistant, isolated A. thaliana chloroplasts were digested with increasing levels of thermolysin, with or without the presence of membrane-disrupting digitonin. Thermolysin digests susceptible proteins not protected by a membrane (75). As demonstrated by a control inner envelope protein, TIC110 (translocon at the inner envelope membrane of chloroplasts 110 kDa) (76), the chloroplasts were intact, which enabled TIC110 to be protected from digestion unless digitonin was added (Fig. 5D, compare lanes 2–4 with 5). Control outer envelope protein, TOC159 (translocon at the outer envelope membrane of chloroplasts, 159 kDa), is known to have an intrinsically thermolysin-resistant portion (77–79). The resistant 52-kDa fragment was detected when thermolysin was present (Fig. 5D, black arrowhead, lanes 2-5 and 7–10); its amount decreased with increasing thermolysin concentration (compare lane 2 with 4, or lane 7 with 9), and it did not entirely disappear when digitonin was present (lanes 5 and 10). A similar pattern was seen for SFR2 as detected by αC-SFR2 (Fig. 5D, lanes 1–5). A nonspecific band co-migrated with the proteolytic fragment, as demonstrated by its presence in the sfr2 knock-out (Fig. 5D, compare lanes 6–10 with lanes 1–5). Thus, the SFR2-specific fragment is best seen by comparing intensities of the band before (Fig. 5D, lane 1) and after thermolysin treatment (lanes 2–5). When viewed in this way, the SFR2-specific fragment had a similar digestion pattern to the TOC159 fragment. Specifically, levels of the proteolytic fragment decreased as increasing thermolysin overcame its resistance (Fig. 5D, lanes 2–5). Accordingly, the presence of the SFR2 fragment was likely to be the result of protease resistance rather than membrane protection.

From the antibody accessibility and protease protection experiments together (Fig. 5), it was inferred that SFR2 has a single N-terminal transmembrane domain (Fig. 2B), consistent with the confident model of the core fold of SFR2 (Fig. 3) and previously reported data (12). Because no further data opposed the model, and the model itself is of good quality, it was used to inform further experiments.

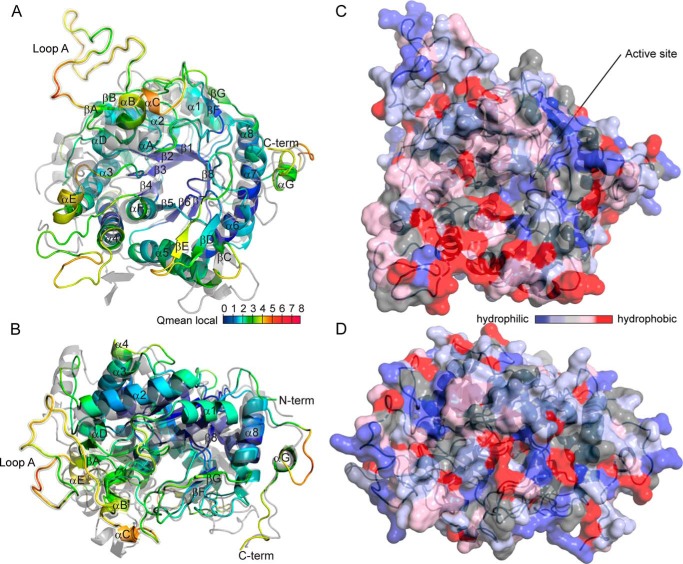

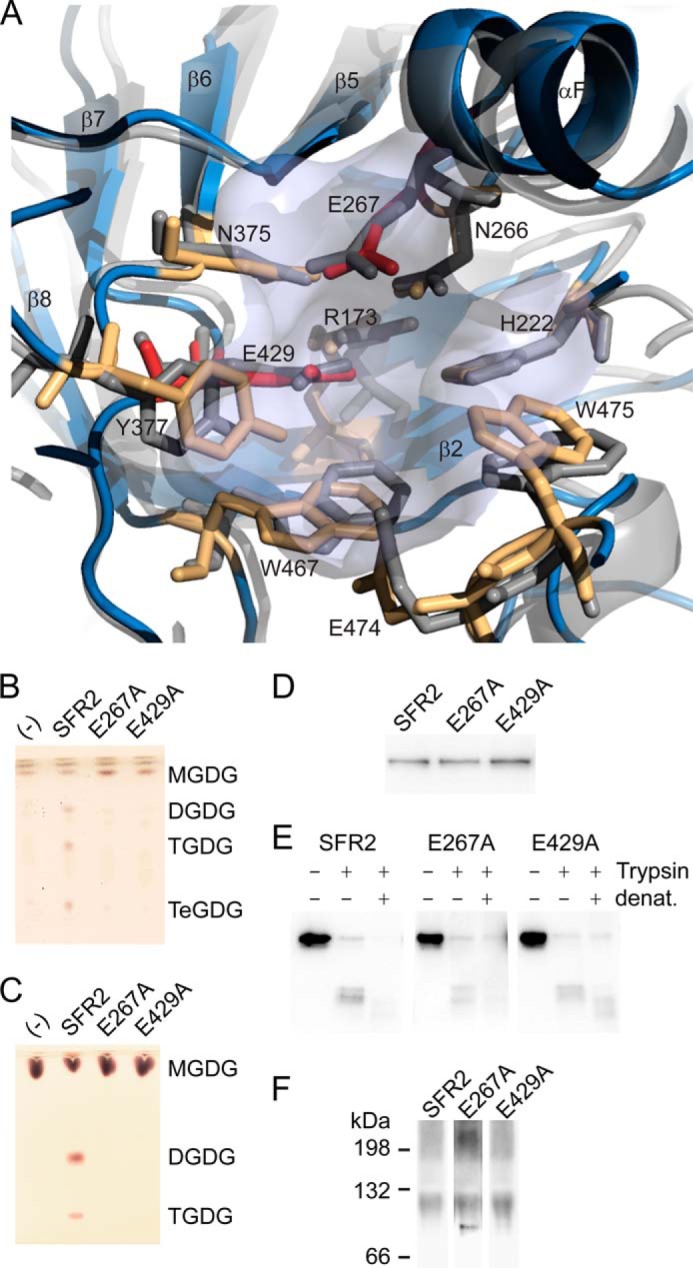

Active Site Architecture of SFR2 Is Conserved with GH1s

Examination of the modeled SFR2 active site shows it to have a similar architecture to that of GH1s (Fig. 6A, orange and red colored residues), due to its considerable sequence identity (Fig. 2A, orange and red colored residues). Within the catalytic site, there is virtual identity with the template structure, 1UWT. The catalytic glutamates Glu-267 and Glu-E429 are each within conserved GH1 motifs TFNEP and VTENG, respectively (Fig. 2A) (5). Based on their positions, Glu-429 is expected to act as the nucleophile and Glu-267 as the acid/base, as in the proposed SFR2 reaction mechanism (Fig. 1B). In the model, these two residues overlay their S. solfataricus GH1 equivalents (1UWT, Fig. 6A, red residues). Forming the local environment for the active glutamates are residues Arg-173, Asn-266, Asn-375, and Tyr-377 (80), which are also positioned similarly to their 1UWT counterparts in the SFR2 model. Substrate galactosyl binding includes residues His-222, Glu-474, Trp-475, and Trp-467 (Fig. 6A) (81), and they are again positioned similarly in the SFR2 model. As a whole, the active site structure of SFR2 is remarkably similar to that of other GH1s.

FIGURE 6.

Glycosyl hydrolase catalytic residues are conserved in SFR2. A, ribbon representation of SFR2 model with catalytic site residues (light blue) shown compared with 1UWT (gray). Catalytic glutamates are shown in red, and residues known to contribute to catalytic chemistry or to sugar binding of glycosyl hydrolases appear in orange. B, thin layer chromatogram of lipids extracted from microsomes purified from yeast expressing MGDG synthase (MGD1) alone or MGD1 and SFR2 constructs. C, thin layer chromatogram of lipid extracts of glycosyl transfer assays under optimal conditions with MGDG (substrate) after 1 h. Chromatograms in B and C are stained for sugars and locations of substrate, and products (DGDG, TGDG, and TeGDG) are indicated. D, immunoblots of yeast microsomes expressing SFR2 or mutant constructs detected using a mixture of antisera recognizing the N or C terminus of SFR2. E, immunoblots of equivalent protein levels of yeast microsomes digested or mock-digested with trypsin (Trypsin) before or after denaturation (denat.) with heat and detergent as indicated at top. Detection was with antisera recognizing the C terminus of SFR2. F, immunoblots of yeast expressing SFR2 or mutant constructs separated by blue native-PAGE detected using a mixture of antisera recognizing the N or C terminus of SFR2.

To ask whether SFR2 uses its GH1-like active site for transferase activity, point mutations of two critical residues were generated. SFR2 analogs of active site glutamates Glu-267 and Glu-429 (17) were each substituted with an alanine residue. Two types of functional assays were used to test activity of the point mutants. To avoid concerns that the activity of weaker variants of SFR2 may be altered or removed during processing, activity was tested within the yeast membrane environment. Mutant and wild-type SFR2 constructs were expressed in yeast coexpressing MGDG synthase. The resulting lipid profile was examined by thin layer chromatography (Fig. 6B). Only wild-type SFR2 was able to generate the products DGDG, TGDG, and TeGDG. In a second assay to confirm the lack of activity, yeast microsomes expressing wild type or mutant SFR2 constructs were extracted and assayed under established optimal glycosyltransferase conditions (Fig. 1) and then visualized by thin layer chromatography (Fig. 6C). Only the wild-type SFR2 construct was observed to produce product oligogalactolipids. Because all three proteins were similarly produced (Fig. 6D), confirmation that the lack of activity was due to mutation of a necessary active site residue rather than incorrect folding was sought. Again, two assays were used. In the first, trypsin was used to test protease accessibility of the folded structure. Digestion of SFR2 produced trypsin-resistant bands (Fig. 6E), but only when digested before denaturing conditions were applied, indicating that occurrence of the resistant band required correctly folded protein. Similar trypsin-resistant fragments were observed after digestion of yeast microsomes expressing the mutant constructs. In the second assay, proteins from yeast microsomes expressing SFR2 or knock-out constructs were gently extracted under nondenaturing conditions and then separated by blue native-PAGE. Wild-type SFR2 ran as both a high molecular weight aggregate and a discrete band near the 132-kDa marker (Fig. 6F). A similar pattern was observed for the two mutant SFR2 constructs. Together, the two assays indicate that the mutant constructs were likely correctly folded, and thus, the lack of activity is due to importance of the residue for catalysis. We concluded that SFR2 uses an active site highly conserved with GH1s to perform transferase activity.

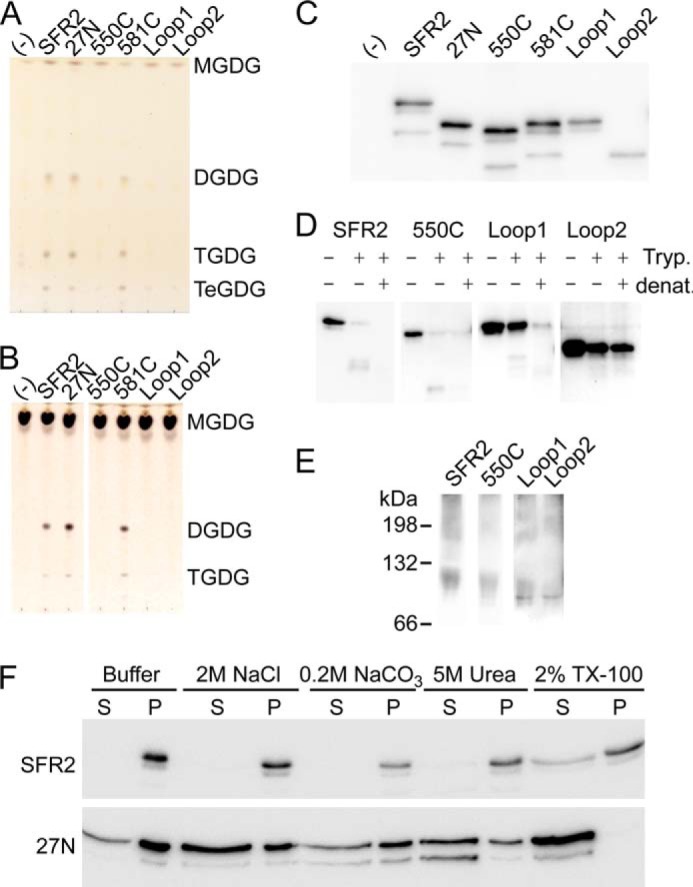

Functional Contributions of SFR2 Loop Regions

Several regions of SFR2 were not similar enough to GH1s to model well (Figs. 2 and 3). To determine the contributions of these regions to glycosyltransferase activity, they were investigated individually. The N terminus of SFR2 is of interest because it was shown previously to be a transmembrane anchor (12), and it is likely the only transmembrane anchor in SFR2 (Fig. 5). The unmodeled portion of the C terminus of SFR2 is of interest because it is unique to SFR2 and SFR2-like proteins, rather than GH1s, and may have intrinsically disordered areas (Fig. 4). Finally, loop A is of interest because of the following: (a) modification of GH1 loops in this position has been shown previously to introduce allosteric control (50); (b) it is only approximately modeled in SFR2 (Fig. 3), and (c) it appears to be intrinsically disordered, as predicted by multiple disorder predictors (Fig. 4). Constructs of SFR2 were made to truncate the N terminus at residue 27 (27N) or the C terminus at residues 550 and 581 (550C and 581C). Loop A was substituted in two ways. Either the equivalent loop from S. solfataricus GH1 (residues 14–64) was substituted (loop 1) or the artificially designed β-turn KQFARH, with only a structural role (49), was substituted (loop 2). Note that the S. solfataricus GH1 loop was not wild type but included a mutation shown to allow allosteric control by indole (50). Mutant constructs and wild-type SFR2 were expressed in yeast producing the substrate MGDG, and the resulting lipid profile was examined by thin layer chromatography (Fig. 7A). Only wild-type SFR2, 27N, and 581C were able to generate products DGDG, TGDG, and TeGDG (Fig. 7A). This was true with or without the addition of indole and was confirmed by a galactosyltransferase assay under optimal conditions, which showed similar results (Fig. 7B). All proteins were produced (Fig. 7C), and therefore, the folding state of mutants lacking activity was ascertained using protease protection and blue native-PAGE. Like wild-type SFR2, 550C and loop 1 constructs both showed protease-resistant fragments that were further degraded if trypsin was applied to denatured proteins (Fig. 7D). Interestingly, the loop 2 construct was resistant to proteases under native or denaturing conditions (Fig. 7D, right panel), which may indicate that the trypsin sensitivity in the other constructs is in loop A, but does not give useful information about its folding. SFR2, 550C, loop 1, and loop 2 constructs each showed similar patterns when separated under nondenaturing conditions (Fig. 7E). Together the experiments confirm the folding of 550C and loop 1 and suggest that loop 2 is also correctly folded.

FIGURE 7.

Unique regions of SFR2 are required for activity. A, thin layer chromatogram of lipids extracted from microsomes purified from yeast producing MGDG synthase (MGD1) alone or MGD1 and SFR2 constructs. B, thin layer chromatogram of lipid extracts of glycosyl transfer assays under optimal conditions with MGDG (substrate) after 1 h. Chromatograms in A and B are stained for sugars and locations of substrates and products (DGDG, TGDG, and TeGDG) are indicated. C, immunoblots of yeast microsomes used in A loaded with equal total protein and detected using a mixture of antisera specific to the N or C terminus of SFR2. D, immunoblots of equivalent protein levels of yeast microsomes digested or mock-digested with trypsin (Tryp.) before or after denaturation (denat.) with heat and detergent as indicated at top. Detection was with antisera recognizing the C terminus of SFR2. E, immunoblots of yeast expressing SFR2 or mutant constructs separated by blue native-PAGE detected using a mixture of antisera recognizing the N or C terminus of SFR2. White spaces separate lanes taken from distinct exposures of the same immunoblot. F, immunoblots of equal culture volumes of yeast producing SFR2 or 27N as indicated at left extracted with reagents indicated above before separation into soluble, S, and insoluble, P, fractions. Detection is by a mixture of antisera specific to the N or C terminus of SFR2 and representative of three repeats.

The possibility that the mutant constructs reduced oligogalactolipid synthesis, but increased activity on non-native substrates, was investigated by assaying with lyso-MGDG, -PNPG, or -ONPG. However, no product development was observed in these assays. Thus, either replacing loop A or removing the C-terminal region closest to the GH1 domain reduced transferase activity without relaxing specificity, although removal of the transmembrane domain or distal C-terminal regions allowed activity.

Given that SFR2 interacts with a hydrophobic substrate, but does not possess a hydrophobic face (Fig. 3), it was not expected that its transmembrane domain was dispensable for function when produced in yeast cells. To test whether removal of the transmembrane domain disrupted interaction of SFR2 with membranes, yeast membranes producing wild type or 27N SFR2 were challenged with high salt, mild base, chaotropic agents, or detergents (Fig. 7C). Wild-type SFR2 stayed with the membrane pellet unless detergent was added, although 27N was partially solubilized in all tested conditions and completely solubilized by detergent. This demonstrates that removal of the transmembrane domain eliminates tight membrane association of SFR2 but not peripheral association.

Hydrophobic Patch Divergent from GH1s Is Necessary for SFR2 Activity

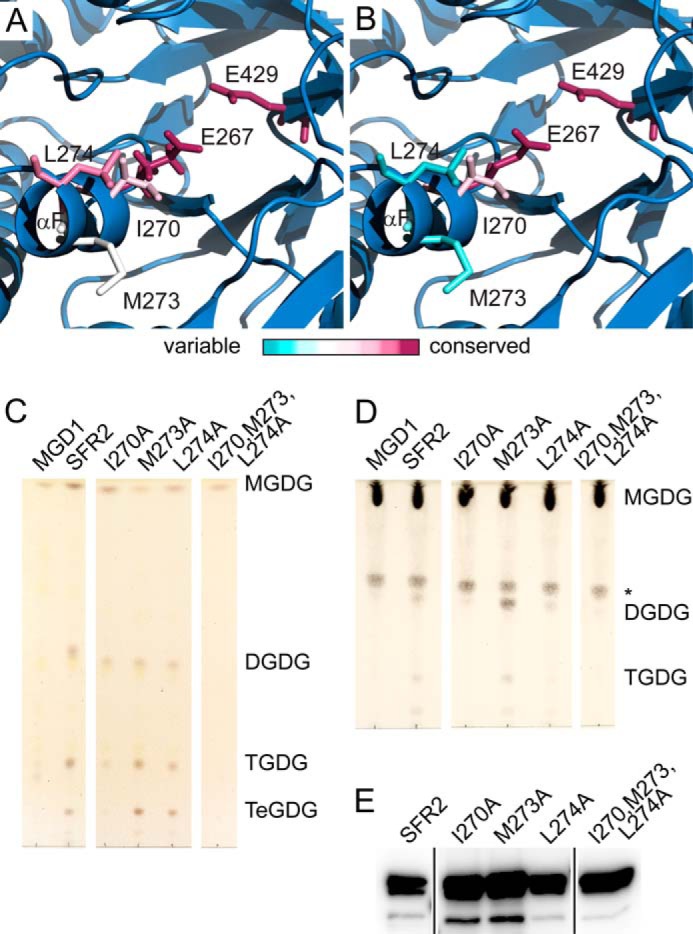

Because SFR2 binds a hydrophobic substrate, residues near the active site were examined for hydrophobicity. As seen in Fig. 3C, a small hydrophobic patch of three residues, Ile-270, Met-273, and Leu-274, exists adjacent to the active site. The relative evolutionary conservation of these residues was estimated based on phylogeny and alignment using ConSurf (36–38). These three positions were found to be strongly conserved when predicted SFR2 orthologs from plant species were considered (Fig. 8A), but less conserved among other GH1s (Fig. 8B). It is likely that the hydrophobic patch is specific to SFR2 and SFR2-like GH1s. Their roles were also investigated by mutagenesis, in which Ile-270, Met-273, and Leu-274 were substituted individually or simultaneously by alanine. When mutant constructs were expressed side-by-side with wild-type SFR2 in yeast that produced substrate MGDG, the resulting lipid profile showed that wild-type SFR2 and individual point mutants could generate products, although the triple point mutant could not (Fig. 8C). Largely similar results were seen in a galactosyltransferase assay under optimal conditions. This showed activity of wild-type SFR2 and M273A were equivalent, with less activity of I270A and L274A and no detectable activity from the triple mutant (Fig. 8D). Variations in SFR2 to microsomal total protein and lipid levels precludes precise quantification of the difference in activity between I270A and L274A, although all proteins were present (Fig. 8E). The inability of the triple mutant to act on MGDG was unexpected and suggests that this hydrophobic patch is important for strong MGDG specificity of SFR2. To further test this hypothesis, single and triple mutants were assayed with lyso-MGDG, PNPG, or ONPG as substrates, although no product development was observed.

FIGURE 8.

Hydrophobic residues are required for transferase activity. Representations of the SFR2 structure illustrating the side chains of active site glutamates and nearby hydrophobic patch. Side chains are colored by evolutionary conservation, as indicated by the ConSurf server for glycosyl hydrolase family 1 proteins that are SFR2-like (A) or excluding SFR2-like proteins (B). C, thin layer chromatogram of lipids extracted from microsomes purified from yeast expressing MGDG synthase (MGD1) alone or MGD1 and SFR2 constructs. White areas separate regions of the same TLC from which additional lanes were removed for clarity. D, thin layer chromatogram of lipid extracts of glycosyl transfer assays under optimal conditions with MGDG (substrate) after 1 h. White areas separate regions of the same TLC from which additional lanes were removed for clarity. An asterisk indicates a sugar-containing contaminant present in the substrate. Chromatograms in C and D are stained for sugars and locations of substrate and products (DGDG, TGDG, and TeGDG) are indicated. E, immunoblots of yeast microsomes used in B loaded with equal total protein and detected using a mixture of antisera specific to the N or C terminus of SFR2. Black lines separate regions of the same blot from which additional lanes were removed for clarity.

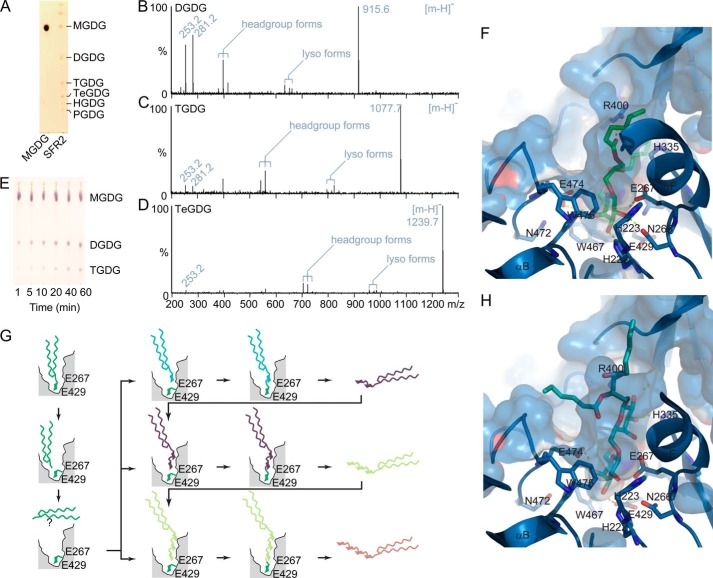

Using the Structural Model to Propose a Mechanism for Processivity

SFR2 produces not only DGDG but also higher order oligogalactolipids with up to six galactosyl residues in yeast (HGDG, Fig. 9A), although we have yet to observe more than four galactosyl residues in plants. The structures of lower order oligogalactolipids (DGDG and TGDG) have been analyzed multiple times by mass spectrometry and NMR analysis comparing extracts from wild type and constitutively active SFR2 in the tgd mutants (3, 66, 82). Additionally, the anomeric configuration of DGDG produced by assaying SFR2-producing yeast extracts was shown to be identical to that found in the extracts of plants with constitutive SFR2 activity (3). Here, masses of di- through penta-oligogalactolipids were investigated by mass spectrometry, resulting in identification of expected deprotonated molecular ions (Table 3). Ions matching expected sizes were selected and further fragmented at low voltages to retain headgroup ions. MS/MS spectra for C16:1/C18:1 di- through tetragalactolipids is shown in Fig. 9, B–D. Fragmentation of the oligogalactolipids resulted in expected peaks, including free fatty acids, lysolipids, and three forms in which both acyl tails were lost. In these forms, the headgroup remained attached to a version of the glycerol backbone, based on previous analyses of galactolipid fragmentation (83). Together with previous studies, these data confirm that the products are as suggested and that SFR2 is processive.

FIGURE 9.

Processivity of SFR2 is consistent with the model. A, thin layer chromatogram of lipids from 50 μg of protein-equivalent S. cerevisiae microsomes containing MGDG and SFR2. MGDG standard is loaded to the left, as indicated below. The number of galactosyl moieties in the headgroup is indicated at right: mono- (MGDG), di- (DGDG), tri- (TGDG), tetra- (TeGDG), penta- (PGDG), and hexa- (HDGD). Spectra obtained by fragmentation of (16:1,18:1) DGDG (B), TGDG (C), or TeGDG (D). Deprotonated molecular ions [M − H]− are labeled as follows: free 16:1 (253.2), free 18:1 (281.2), headgroup forms include the headgroup and glycerol backbone but have lost both fatty acids to form a diene group (379.1 DGDG, 541.2 TGDG, or 703.3 TeGDG), double hydroxyl groups (415.1 DGDG, 577.2 TGDG, or 739.2 TeGDG), or an enol group (397.1 DGDG, 559.2 TGDG, or 721.2 TeGDG) on the backbone glycerol, finally lyso-forms have lost an 18:1 (633.3 DGDG, 795.4 TGDG, or 957.5 TeGDG) or a 16:1 acyl group (661.4 DGDG, 823.4 TGDG, or 985.5 TeGDG). E, microsomes isolated from S. cerevisiae producing SFR2 were incubated with MGDG for the indicated number of minutes. The thin layer chromatogram has been stained for sugars and locations of MGDG (substrate), DGDG, and TGDG (products) are indicated. Surface and ribbon representations of the SFR2 active site in blue, with stick representation of a docked initial MGDG substrate, shown with carbon atoms in green (F), or the docked product DGDG, with carbon atoms in cyan (H). Polar contacts are shown with dashed lines. Acyl tails of both lipid species were reduced to six carbons for simplicity. G, diagram showing expected processivity of SFR2. Enzyme active site is cut away in gray with approximate positions of active site residues indicated. First, removal of a galactosyl moiety from MGDG is shown in top panels. Diffusion freedom of diacylglycerol by-product after lysis of MGDG is unclear and indicated by a question mark. Second, transfer of the galactosyl moiety to multiple galactolipid acceptors is shown in the bottom panels. In each case, the number of galactosyl moieties is increased by one.

TABLE 3.

Expected and observed absolute mass values of oligogalactolipids

| Species | Expected mass (m/z − H) | Observed mass (m/z − H) |

|---|---|---|

| DGDG | ||

| 16:1/16:1 | 887.573 | 887.58 |

| 16:0/16:1 | 889.588 | 889.59 |

| 16:1/18:1 | 915.604 | 915.61 |

| 16:0/18:1 | 917.619 | 917.62 |

| TGDG | ||

| 16:1/16:1 | 1049.625 | 1049.64 |

| 16:0/16:1 | 1051.641 | 1051.65 |

| 16:1/18:1 | 1077.656 | 1077.67 |

| 16:0/18:1 | 1079.672 | 1079.68 |

| TeGDG | ||

| 16:1/16:1 | 1211.678 | 1211.69 |

| 16:0/16:1 | 1213.693 | 1213.70 |

| 16:1/18:1 | 1239.709 | 1239.72 |

| 16:0/18:1 | 1241.724 | 1241.74 |

| PGDG | ||

| 16:1/16:1 | 1373.730 | 1373.74 |

| 16:0/16:1 | 1375.746 | 1375.74 |

| 16:1/18:1 | 1401.761 | 1401.77 |

| 16:0/18:1 | 1403.777 | 1403.78 |

Observation of time course reactions with SFR2 shows that DGDG is made first, TGDG second, etc. (Fig. 9E), favoring a sequential reaction. Furthermore, docking of MGDG into the SFR2 model indicates that space in the active site is insufficient for simultaneous removal of multiple galactosyl moieties (Fig. 9F), consistent with observed production of TGDG rather than TeGDG from DGDG (Fig. 1F). Thus, a model of a possible reaction mechanism is proposed in Fig. 9G in which a galactosyl moiety is removed from MGDG and then added to either another MGDG or an oligogalactolipid, forming DGDG or a higher order oligogalactolipid. In this manner, the distal galactosyl group on product DGDG is positioned very similarly to the galactosyl group of the MGDG, as modeled in Fig. 9H.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that SFR2 is a GH1 member that performs little or no hydrolase activity, instead acting as a glycosyltransferase. A reliable homology model of SFR2 was produced and then analyzed computationally and by mutagenesis to understand the mechanism of transferase rather than hydrolase function. The catalytic site of SFR2 is identical in sequence (Fig. 2A) and similar in architecture (Fig. 6A) to that of other studied glycosyl hydrolases and requires the same catalytic residues (Fig. 6, B–F). In contrast, SFR2 was shown to contain multiple regions dissimilar to GH1s, including loop A, a C-terminal region between 550 and 581, and hydrophobic residues near the active site. Experiments show these regions are also required for galactosyltransferase activity (Figs. 7, A–E, and 8, C and D). We conclude that evolutionary pressure changed SFR2 from a hydrolase to a transferase by altering residues external to the active site.

Interestingly, hydrolase activity was not observed in the wild-type SFR2 enzyme or in any of its mutations or truncations. It is somewhat surprising that removal or alteration of individual regions of SFR2 divergent from GH1s could not restore hydrolase activity. Structural alterations used by nature to evolve a hydrolase to a transferase are currently unknown (9) but are hypothesized to include binding of an alternate nucleophile while simultaneously excluding water (62). Because the active site face of SFR2 is not hydrophobic (Fig. 3C), an obvious place for water molecules to access the catalytic site is through the substrate binding cavity. The hydrophobic patch (residues Ile-270, Met-273, and Lys-274) near the active site could potentially exclude a water molecule from performing hydrolysis after formation of the enzyme-galactoside intermediate in a manner similar to the induced fit and solvent exclusion hypotheses for other transferases (84–87).

Alternatively, loop A or the C terminus could act as a flexible “lid,” closing over the active site during catalysis to exclude water, as occurs in a number of other (β/α)8 barrel proteins including triose-phosphate isomerase (88–91). Several lid type (β/α)8 barrel proteins studied to date use a loop extension within the α/β barrel region, and within the GH1 family, small changes to loops in the position of loop A have been shown to allow allosteric control (50). Also similar to other lid domains, both loop A and a small region of the C terminus may be intrinsically disordered (Fig. 4) and adopt a more defined structure upon substrate recognition (89, 91). If loop A or the C terminus indeed acts as a lid, they could be excellent targets for regulation. Replacement of any of these regions, hydrophobic triad, loop A, or C terminus, has clearly indicated that each is required for transferase activity (Figs. 7 and 8), although their removal or replacement did not restore hydrolase activity.

In addition to the possibility of water entering the active site through the substrate binding cavity, it has recently been suggested that GH1 family proteins have a conserved water channel (92). This channel allows water molecules to access active site glutamates through the “side” of the (β/α)8 barrel. If this channel was required for hydrolase activity, we anticipate that it is not present in SFR2, as hydrolase activity is not observed. Comparison of the position of the proposed water channel in the structure of T. thermophilus with structures of SFR2 or 1UWT shows that multiple side chains and some main-chain positions differ between the three proteins. It is not clear whether these changes are sufficient to exclude water from traveling through the (β/α)8 barrel. A point of interest is that the proposed water channel would pass near residues Ser-224 and His-223, which were manually adjusted in the SFR2 model to more closely adopt the GH1-conserved position in the active site. It is possible that the SFR2 structure varies from other GH1s in this region, although at the primary sequence level this region is more similar to GH1s than loop A or the N or C terminus.

At the onset of this study, it seemed attractive to speculate that any domain of SFR2, which connected it to the membrane (12), could also be a likely point of control for active site solvent. Similar to the idea that SFR2 may be held to the membrane by a hydrophobic face (9), we reasoned that if the substrate binding cavity of SFR2 was held tightly to the membrane surface by a transmembrane domain or domains, water could also be excluded. A previous study suggested that multiple transmembrane domains may be present in SFR2. However, our data indicate the presence of a single N-terminal transmembrane domain for multiple reasons. First, its removal disrupts tight membrane association (Fig. 7F). Second, antisera could recognize SFR2 terminal regions outside the chloroplast membrane (Fig. 5, B and C). Third, the proteolytic fragment seen in the original paper was unlikely to have occurred because of the protection of a membrane, as it had similar protease resistance to that of a natively protease-resistant fragment from an established monotopic membrane protein of the chloroplast outer envelope, rather than a protein truly protected by the membrane (Fig. 5D). Fourth, the model was predictive of active site residues (Fig. 6), indicating the presence of the (β/α)8 barrel fold. A second transmembrane domain would have removed strand and helix 8 of the (β/α)8 barrel, but these have retained similarity and identity to GH1s (Fig. 2), notably so in a conserved GH1 motif (GYIFWTISDNWEW, see Refs. 5, 12). Finally, it was noted that hydrophobicity in the residues suggested to be the second transmembrane domain (448–470) was not conserved among SFR2-like proteins. Therefore, concluding that SFR2 has a single transmembrane domain, it was then interesting that relaxation of membrane association by removal of the transmembrane domain did not alter galactosyltransferase activity. 27N SFR2 activity was indistinguishable from wild-type activity in yeast or by in vitro assay (Fig. 7, A–E). We conclude that the membrane-bound nature of SFR2 substrates and products has had little or no influence on the mechanism of water exclusion from the enzyme-galactoside intermediate.

The 27N construct of SFR2 lacked a transmembrane domain and yet still associated with membranes in a peripheral manner (Fig. 7C). It is possible that membrane interaction was maintained by binding of membrane-bound substrates or products, using hydrophobicity present at the SFR2 surface. The most likely region of SFR2 to interact with the hydrophobic acyl groups of its reactants is the loop region between helix 4 (α4) and strand 4 (β4) of the (β/α)8 barrel. This loop includes the hydrophobic patch (residues Ile-270, Met-273, and Leu-274) of αF, by which one of the acyl chains of MGDG was favorably positioned during docking (Fig. 9C), and appears to form an exposed hydrophobic surface (Fig. 3C). The requirement of the hydrophobic patch for SFR2 activity (Fig. 7A) and its placement in docking studies lends weight to the idea of substrate binding in this region. Because the structural model of SFR2 is based on structures of enzymes accepting hydrophilic substrates, we also cannot exclude the possibility that the increased hydrophobicity of this region indicates that it adopts an altered conformation relative to other GH1 family members.

Previously, Mg2+ and Mn2+ were described to stimulate galactolipid/galactolipid galactosyltransferase activity in isolated chloroplasts (64), an activity that is now attributed to SFR2 (3). Here, we showed that cations directly activate SFR2 in vitro (Fig. 1E), and the types of activating cations include Ca2+ and to a much lower extent K+. The cellular levels of cations should be considered when deducing which ions are used by SFR2 in vivo. In plants, the most plentiful divalent cation is Mg2+, which is present at 2–10 mm in the cell. Free Mg2+ concentrations are lower than this and have been measured as low as 0.4 mm (93). In comparison, Ca2+ and Zn2+ concentrations are estimated to be nano- or even picomolar (94, 95). Monovalent cations can be present at much higher levels, and K+ concentrations alone are estimated at 55–60 mm (96). It seems likely that SFR2 uses primarily Mg2+ or possibly K+ as a ligand in vivo. Metal usage is unusual among GH1 family proteins but not among other (β/α)8 barrel proteins. For example, in rhamnose isomerase, an active site acidic residue is substituted by a water molecule activated by a nearby Mg2+ (89). SFR2 could adopt a similar mechanism, although its highly conserved GH1-like active site suggests that metal binding is probably in another region. Prediction of metal-binding sites in SFR2 using multiple structure-based predictors (97–99) did not allow firm definition of the site(s).

In addition to metal binding, the in vitro studies of SFR2 activity raised another biological question. In vitro, SFR2 was not observed to perform the “back reaction,” converting ββ-DGDG into MGDG efficiently (Fig. 1F). It is likely that MGDG was produced transiently and then further reacted to make TGDG, as TGDG was an observable product (Fig. 1E). If the same is true in vivo, then another enzyme or enzymes is likely to degrade oligogalactolipids generated during stress conditions. The nature of this enzyme or these enzymes is unknown, and they may also be necessary for plant recovery from freezing.

In conclusion, the SFR2 structural model and dissection of functional roles of SFR2 subdomains presented in this work have already allowed us to answer multiple structure/function hypotheses about the relationship of SFR2 activity to glycosyl hydrolase activity. Using this information, molecular engineering of SFR2 for controlling freeze tolerance can now be more clearly driven.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Allan TerBush and Kathy Osteryoung for fluorescent microscope usage; Wolf-Dieter Reiter for the alditol acetate protocol; Dan Jones and Lijun Chen for assistance with mass spectrometry; and Eric Moellering for useful discussions on SFR2 function.

This work was supported by the Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences, Office of Basic Energy Sciences of the United States Department of Energy Grant DE-FG02-98ER20305 (to C. B.).

This article contains supplemental supporting material.

- GH1

- family 1 glycosyl hydrolase

- DGDG

- digalactosyldiacylglycerol

- MGDG

- monogalactosyldiacylglycerol

- MGD1

- monogalactosyldiacylglycerol synthase 1

- ONPG

- 2-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- PNPG

- p-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucoside

- TeGDG

- tetragalactosyldiacylglycerol

- TGDG

- trigalactosyldiacylglycerol.

REFERENCES

- 1. Warren G., McKown R., Marin A. L., Teutonico R. (1996) Isolation of mutations affecting the development of freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana (L) Heynh. Plant Physiol. 111, 1011–1019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thorlby G., Fourrier N., Warren G. (2004) The SENSITIVE TO FREEZING2 gene, required for freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana, encodes a β-glucosidase. Plant Cell 16, 2192–2203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moellering E. R., Muthan B., Benning C. (2010) Freezing tolerance in plants requires lipid remodeling at the outer chloroplast membrane. Science 330, 226–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moellering E. R., Benning C. (2011) Galactoglycerolipid metabolism under stress: a time for remodeling. Trends Plant Sci. 16, 98–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]