The current systematic literature review and meta-analysis extends and confirms the associations of obesity with an unfavourable overall and breast cancer survival in pre and postmenopausal breast cancer, regardless of when BMI is ascertained. Increased risks of mortality in underweight and overweight women and J-shape associations with total mortality were also observed. The recommendation of maintaining a healthy body weight throughout life is important as obesity is a pandemic health concern.

Keywords: body mass index, meta-analysis, survival after breast cancer, systematic literature review

Abstract

Background

Positive association between obesity and survival after breast cancer was demonstrated in previous meta-analyses of published data, but only the results for the comparison of obese versus non-obese was summarised.

Methods

We systematically searched in MEDLINE and EMBASE for follow-up studies of breast cancer survivors with body mass index (BMI) before and after diagnosis, and total and cause-specific mortality until June 2013, as part of the World Cancer Research Fund Continuous Update Project. Random-effects meta-analyses were conducted to explore the magnitude and the shape of the associations.

Results

Eighty-two studies, including 213 075 breast cancer survivors with 41 477 deaths (23 182 from breast cancer) were identified. For BMI before diagnosis, compared with normal weight women, the summary relative risks (RRs) of total mortality were 1.41 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.29–1.53] for obese (BMI >30.0), 1.07 (95 CI 1.02–1.12) for overweight (BMI 25.0–<30.0) and 1.10 (95% CI 0.92–1.31) for underweight (BMI <18.5) women. For obese women, the summary RRs were 1.75 (95% CI 1.26–2.41) for pre-menopausal and 1.34 (95% CI 1.18–1.53) for post-menopausal breast cancer. For each 5 kg/m2 increment of BMI before, <12 months after, and ≥12 months after diagnosis, increased risks of 17%, 11%, and 8% for total mortality, and 18%, 14%, and 29% for breast cancer mortality were observed, respectively.

Conclusions

Obesity is associated with poorer overall and breast cancer survival in pre- and post-menopausal breast cancer, regardless of when BMI is ascertained. Being overweight is also related to a higher risk of mortality. Randomised clinical trials are needed to test interventions for weight loss and maintenance on survival in women with breast cancer.

introduction

The number of female breast cancer survivors is growing because of longer survival as a consequence of advances in treatment and early diagnosis. There were ∼2.6 million female breast cancer survivors in US in 2008 [1], and in the UK, breast cancer accounted for ∼28% of the 2 million cancer survivors in 2008 [2].

Obesity is a pandemic health concern, with over 500 million adults worldwide estimated to be obese and 958 million were overweight in 2008 [3]. One of the established risk factors for breast cancer development in post-menopausal women is obesity [4], which has further been linked to breast cancer recurrence [5] and poorer survival in pre- and post-menopausal breast cancer [6, 7]. Preliminary findings from randomised, controlled trials suggest that lifestyle modifications improved biomarkers associated with breast cancer progression and overall survival [8].

The biological mechanisms underlying the association between obesity and breast cancer survival are not established, and could involve interacting mediators of hormones, adipocytokines, and inflammatory cytokines which link to cell survival or apoptosis, migration, and proliferation [9]. Higher level of oestradiol produced in postmenopausal women through aromatisation of androgens in the adipose tissues [10], and higher level of insulin [11], a condition common in obese women, are linked to poorer prognosis in breast cancer. A possible interaction between leptin and insulin [12], and obesity-related markers of inflammation [13] have also been linked to breast cancer outcomes. Non-biological mechanisms could include chemotherapy under-dosing in obese women, suboptimal treatment, and obesity-related complications [14].

Numerous studies have examined the relationship between obesity and breast cancer outcomes, and past reviews have concluded that obesity is linked to a lower survival; however, when investigated in a meta-analysis of published data, only the results of obese compared with non-obese or lighter women were summarised [6, 7, 15].

We carried out a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of published studies to explore the magnitude and the shape of the association between body fatness, as measured by body mass index (BMI), and the risk of total and cause-specific mortality, overall and in women with pre- and post-menopausal breast cancer. As body weight may change close to diagnosis and during primary treatment of breast cancer [16], we examined BMI in three periods: before diagnosis, <12 months after diagnosis, and ≥12 months after breast cancer diagnosis.

materials and methods

data sources and search

We carried out a systematic literature search, limited to publications in English, for articles on BMI and survival in women with breast cancer in OVID MEDLINE and EMBASE from inception to 30 June 2013 using the search strategy implemented for the WCRF/AICR Continuous Update Project on breast cancer survival. The search strategy contained medical subject headings and text words that covered a broad range of factors on diet, physical activity, and anthropometry. The protocol for the review is available at http://www.dietandcancerreport.org/index.php [17]. In addition, we hand-searched the reference lists of relevant articles, reviews, and meta-analysis papers.

study selection

Included were follow-up studies of breast cancer survivors, which reported estimates of the associations of BMI ascertained before and after breast cancer diagnosis with total or cause-specific mortality risks. Studies that investigated BMI after diagnosis were divided into two groups: BMI <12 months after diagnosis (BMI <12 months) and BMI 12 months or more after diagnosis (BMI ≥12 months). Outcomes included total mortality, breast cancer mortality, death from cardiovascular disease, and death from causes other than breast cancer. When multiple publications on the same study population were found, results based on longer follow-up and more outcomes were selected for the meta-analysis.

data extraction

DSMC, TN, and DA conducted the search. DSMC, ARV, and DNR extracted the study characteristics, tumour-related information, cancer treatment, timing and method of weight and height assessment, BMI levels, number of outcomes and population at-risk, outcome type, estimates of association and their measure of variance [95% confidence interval (CI) or P value], and adjustment factors in the analysis.

statistical analysis

Categorical and dose–response meta-analyses were conducted using random-effects models to account for between-study heterogeneity [18]. Summary relative risks (RRs) were estimated using the average of the natural logarithm of the RRs of each study weighted by the inverse of the variance and then unweighted by applying a random-effects variance component which is derived from the extent of variability of the effect sizes of the studies. The maximally adjusted RR estimates were used for the meta-analysis except for the follow-up of randomised, controlled trials [19, 20] where unadjusted results were also included, as these studies mostly involved a more homogeneous study population. BMI or Quetelet's Index (QI) measured in units of kg/m2 was used.

We conducted categorical meta-analyses by pooling the categorical results reported in the studies. The studies used different BMI categories. In some studies, underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m2 according to WHO international classification) and normal weight women (BMI 18.5–<25.0 kg/m2) were classified together but, in some studies, they were classified separately. Similarly, most studies classified overweight (BMI 25.0–<30.0 kg/m2) and obese (BMI ≥30.0 kg/m2) women separately but, in some studies, overweight and obese women were combined. The reference category was normal weight or underweight together with normal weight, depending on the studies. For convenience, the BMI categories are referred to as underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese in the present review. We derived the RRs for overweight and obese women compared with normal weight women in two studies [19, 21] that had more than four BMI categories using the method of Hamling et al. [22]. Studies that reported results for obese compared with non-obese women were analysed separately.

The non-linear dose–response relationship between BMI and mortality was examined using the best-fitting second-order fractional polynomial regression model [23], defined as the one with the lowest deviance. Non-linearity was tested using the likelihood ratio test [24]. In the non-linear meta-analysis, the reference category was the lowest BMI category in each study and RRs were recalculated using the method of Hamling et al. [22] when the reference category was not the lowest BMI category in the study.

We also conducted linear dose–response meta-analyses, excluding the category underweight when reported separately in the studies, by pooling estimates of RR per unit increase (with its standard error) provided by the studies, or derived by us from categorical data using generalised least-squares for trend estimation [25]. To estimate the trend, the numbers of outcomes and population at-risk for at least three BMI categories, or the information required to derive them using standard methods [26], and means or medians of the BMI categories, or if not reported in the studies, the estimated midpoints of the categories had to be available. When the extreme BMI categories were open-ended, we used the width of the adjacent close-ended category to estimate the midpoints. Where the RRs were presented by subgroups (age group [27], menopausal status [28, 29], stage [30] or subtype [31] of breast cancer, or others [32–34]), an overall estimate for the study was obtained by a fixed-effect model before pooling in the meta-analysis. We estimated the risk increase of death for an increment of 5 kg/m2 of BMI.

To assess heterogeneity, we computed the Cochran Q test and I2 statistic [35]. The cut points of 30% and 50% were used for low, moderate, and substantial level of heterogeneity. Sources of heterogeneity were explored by meta-regression and subgroup analyses using pre-defined factors, including indicators of study quality (menopausal status, hormone receptor status, number of outcomes, length of follow-up, study design, geographic location, BMI assessment, adjustment for confounders, and others). Small study or publication bias was examined by Egger's test [36] and visual inspection of the funnel plots. The influence of each individual study on the summary RR was examined by excluding the study in turn [37]. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 12.1 (Stata Statistical Software: Release 12, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

results

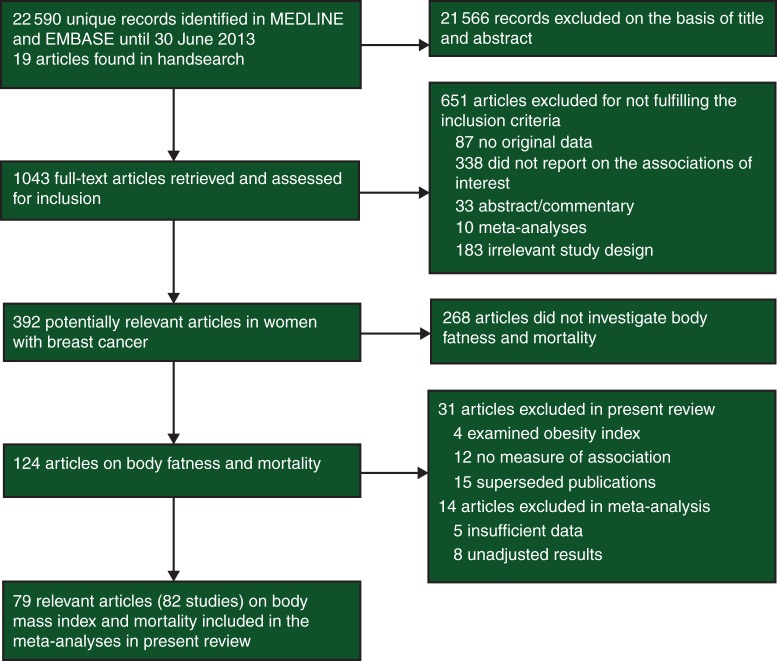

A total of 124 publications investigating the relationship of body fatness and mortality in women with breast cancer were identified. We excluded 31 publications, including four publications on other obesity indices [38–41], 12 publications without a measure of association [42–53], and 15 publications superseded by publications of the same study with more outcomes [54–68]. A further 14 publications were excluded because of insufficient data for the meta-analysis (five publications [69–73]) or unadjusted results (nine publications [74–82]), from which nine publications reported statistically significant increased risk of total, breast cancer or non-breast cancer mortality in obese women (before or <12 months after diagnosis) compared with the reference BMI [69, 71–74, 76, 77, 79, 82], two publications reported non-significant inverse associations [75, 80] and three publications reported no association [70, 78, 81] of BMI with survival after breast cancer. Hence, 79 publications from 82 follow-up studies with 41 477 deaths (23 182 from breast cancer) in 213 075 breast cancer survivors were included in the meta-analyses (Figure 1). Supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online shows the characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analyses and details of the excluded studies are in supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online. Results of the meta-analyses are summarised in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of search.

Table 1.

Summary of meta-analyses of BMI and survival in women with breast cancera

| BMI before diagnosis |

BMI <12 months after diagnosis |

BMI ≥12 months after diagnosis |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | RR (95% CI) |

I2 (%) Ph |

N | RR (95% CI) |

I2 (%) Ph |

N | RR (95% CI) |

I2 (%) Ph |

|

| Total mortality | |||||||||

| Under versus normal weight | 10 | 1.10 (0.92–1.31) | 48% 0.04 |

11 | 1.25 (0.99–0.57) | 63% <0.01 |

3 | 1.29 (1.02–1.63) | 0% 0.39 |

| Over versus normal weight | 19 | 1.07 (1.02–1.12) | 0% 0.88 |

22 | 1.07 (1.02–1.12) | 21% 0.18 |

4 | 0.98 (0.86–1.11) | 0% 0.72 |

| Obese versus normal weight | 21 | 1.41 (1.29–1.53) | 38% 0.04 |

24 | 1.23 (1.12–1.33) | 69% <0.01 |

5 | 1.21 (1.06–1.38) | 0% 0.70 |

| Obese versus non-obese | – | – | – | 12 | 1.26 (1.07–1.47) | 80% <0.01 |

– | – | – |

| Per 5 kg/m2 increase | 15 | 1.17 (1.13–1.21) | 7% 0.38 |

12 | 1.11 (1.06–1.16) | 55% 0.01 |

4 | 1.08 (1.01–1.15) | 0% 0.52 |

| Breast cancer mortality | |||||||||

| Under versus normal weight | 8 | 1.02 (0.85–1.21) | 31% 0.18 |

5 | 1.53 (1.27–1.83) | 0% 0.59 |

1 | 1.10 (0.15–8.08) | – |

| Over versus normal weight | 21 | 1.11 (1.06–1.17) | 0% 0.66 |

12 | 1.11 (1.03–1.20) | 14% 0.31 |

2 | 1.37 (0.96–1.95) | 0% 0.90 |

| Obese versus normal weight | 22 | 1.35 (1.24–1.47) | 36% 0.05 |

12 | 1.25 (1.10–1.42) | 53% 0.02 |

2 | 1.68 (0.90–3.15) | 67% 0.08 |

| Obese versus non-obese | – | – | – | 6 | 1.26 (1.05–1.51) | 64% 0.02 |

– | – | – |

| Per 5 kg/m2 increase | 18 | 1.18 (1.12–1.25) | 47% 0.01 |

8 | 1.14 (1.05–1.24) | 66% 0.01 |

2 | 1.29 (0.97–1.72) | 64% 0.10 |

| Cardiovascular disease related mortality | |||||||||

| Over versus normal weight | 2 | 1.01 (0.80–1.29) | 0% 0.87 |

– | – | – | – | – | – |

| Obese versus normal weight | 2 | 1.60 (0.66–3.87) | 78% 0.03 |

– | – | – | – | – | – |

| Per 5 kg/m2 increase | 2 | 1.21 (0.83–1.77) | 80% 0.03 |

– | – | – | – | – | – |

| Non-breast cancer mortality | |||||||||

| Over versus normal weight | – | – | – | 5 | 0.96 (0.83–1.11) | 26% 0.25 |

– | – | – |

| Obese versus normal weight | – | – | – | 5 | 1.29 (0.99–1.68) | 72% 0.01 |

– | – | – |

aBMI before and after diagnosis (<12 months after, or ≥12 months after diagnosis) was classified according to the exposure period which the studies referred to in the BMI assessment; the BMI categories were included in the categorical meta-analyses as defined by the studies.

Ph, P for heterogeneity between studies.

Studies were follow-up of women with breast cancer identified in prospective aetiologic cohort studies (women were free of cancer at enrolment), or cohorts of breast cancer survivors whose participants were identified in hospitals or through cancer registries, or follow-up of breast cancer patients enrolled in case–control studies or randomised clinical trials.

Some studies included only premenopausal women [83–85] or postmenopausal women [21, 27, 86–94], but most studies included both. Menopausal status was usually determined at time of diagnosis. Year of diagnosis was from 1957–1965 [70] to 2002–2009 [74]. Patient tumour characteristics and stage of disease at diagnosis varied across studies, and some studies included carcinoma in situ. No all studies provided clinical information on the tumour, treatment, and co-morbidities.

Most of the studies were based in North America or Europe. There were three studies from each of Australia [79, 95, 96], Korea [97, 98] and China [99–101]; two studies from Japan [71, 102]; one study from Tunisia [103] and four international studies [19, 104–106]. Study size ranged from 96 [107] to 24 698 patients [97]. Total number of deaths ranged from 56 [93] to 7397 [108], and the proportion of deaths from breast cancer ranged from 22% [27] to 98% [84] when reported. All but eight studies [30, 93, 94, 98, 99, 109–111] had an average follow-up of more than 5 years.

BMI and total mortality

categorical meta-analysis

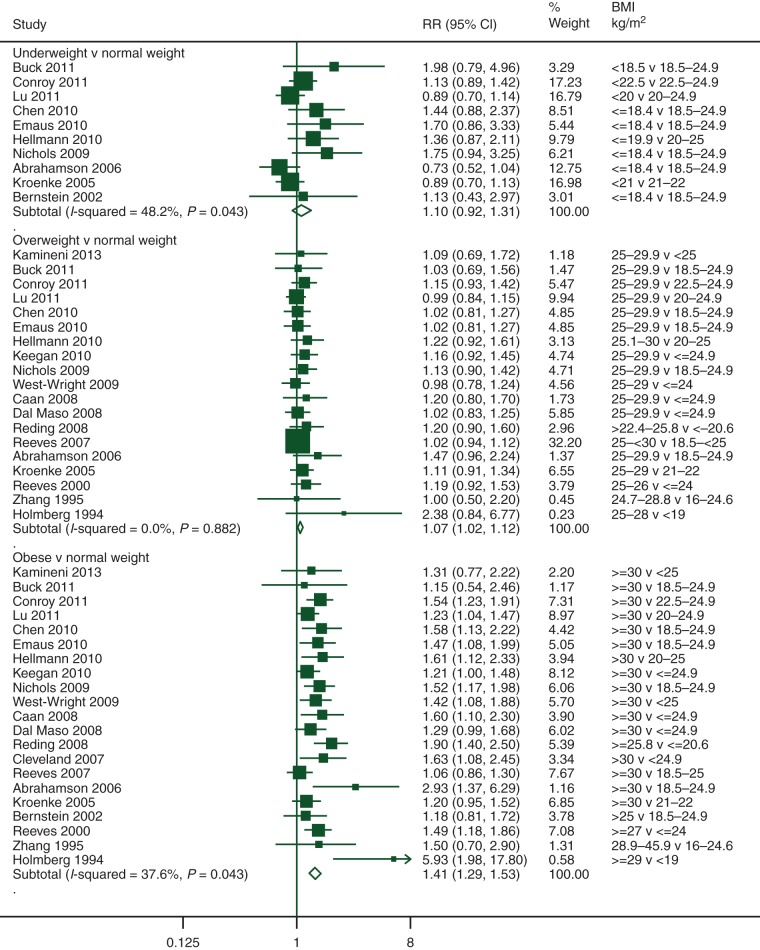

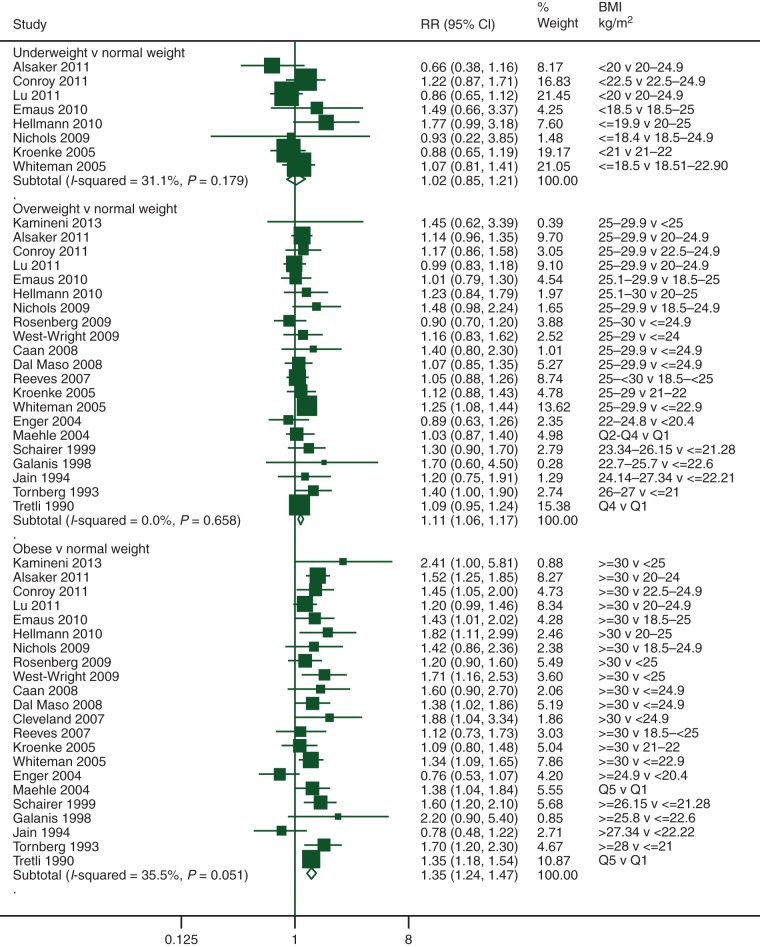

For BMI before diagnosis, compared with normal weight women, the summary RRs were 1.41 (95% CI 1.29–1.53, 21 studies) for obese women, 1.07 (95% CI 1.02–1.12, 19 studies) for overweight women, and 1.10 (95% CI 0.92–1.31, 10 studies) for underweight women (Figure 2). For BMI <12 months after diagnosis and the same comparisons, the summary RRs were 1.23 (95% CI 1.12–1.33, 24 studies) for obese women, 1.07 (95% CI 1.02–1.12, 22 studies) for overweight women, and 1.25 (95% CI 0.99–1.57, 11 studies) for underweight women (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). Substantial heterogeneities were observed between studies of obese women and underweight women (I2 = 69%, P < 0.01; I2 = 63%, P < 0.01, respectively). For BMI ≥12 months after diagnosis, the summary RRs were 1.21 (95% CI 1.06–1.38, 5 studies) for obese women, 0.98 (95% CI 0.86–1.11, 4 studies) for overweight women, and 1.29 (95% CI 1.02–1.63, 3 studies) for underweight women (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). Twelve additional studies reported results for obese versus non-obese women <12 months after diagnosis, and the summary RR was 1.26 (95% CI 1.07–1.47, I2 = 80%, P < 0.01).

Figure 2.

Categorical meta-analysis of pre-diagnosis BMI and total mortality.

dose–response meta-analysis

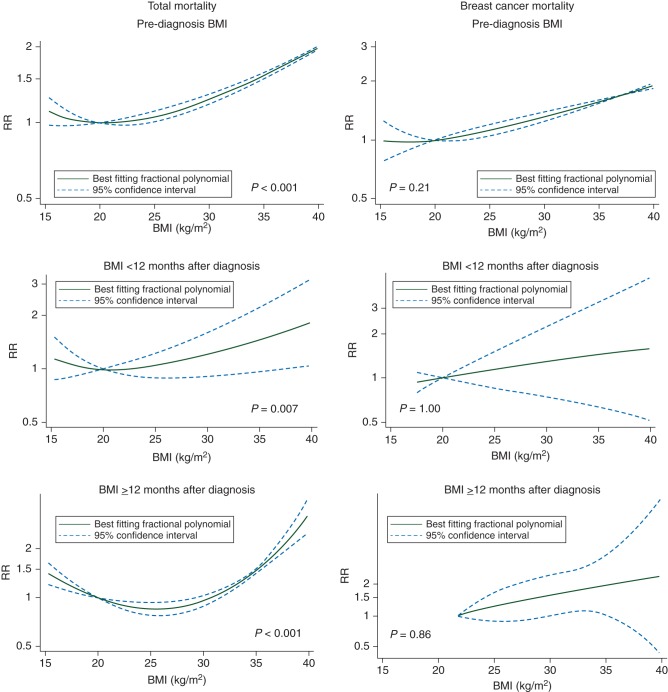

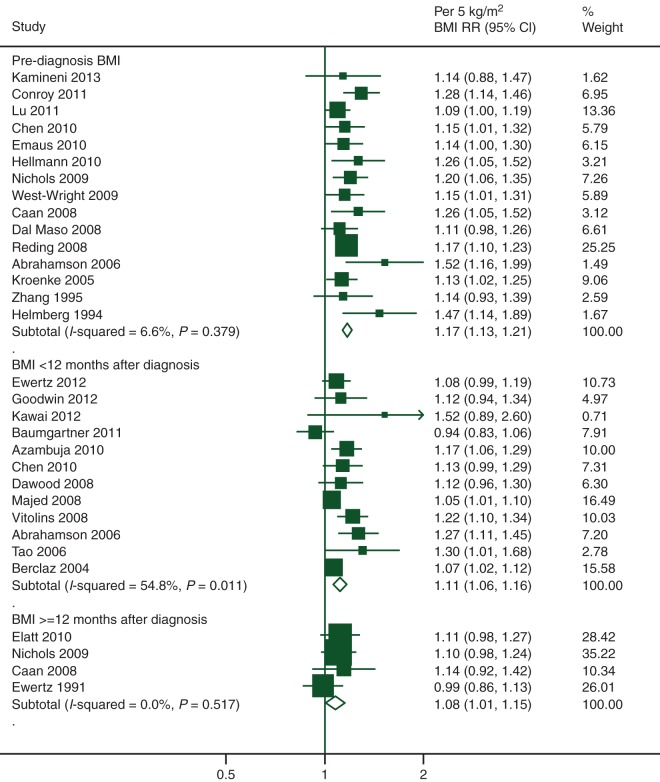

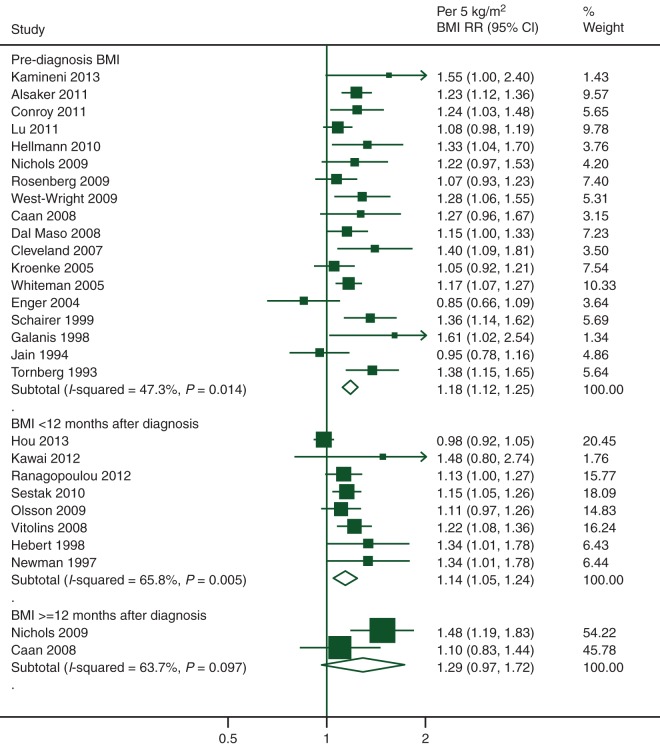

There was evidence of a J-shaped association in the non-linear dose–response meta-analyses of BMI before and after diagnosis with total mortality (all P < 0.01; Figure 3), suggesting that underweight women may be at slightly increased risk compared with normal weight women. The curves show linear increasing trends from 20 kg/m2 for BMI before diagnosis and <12 months after diagnosis, and from 25 kg/m2 for BMI ≥12 months after diagnosis. When linear models were fitted excluding the underweight category, the summary RRs of total mortality for each 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI were 1.17 (95% CI 1.13–1.21, 15 studies, 6358 deaths), 1.11 (95% CI 1.06–1.16, 12 studies, 6020 deaths), and 1.08 (95% CI 1.01–1.15, 4 studies, 1703 deaths) for BMI before, <12 months after, and ≥12 months after diagnosis, respectively (Figure 4). Substantial heterogeneity was observed between studies on BMI <12 months after diagnosis (I2 = 55%, P = 0.01).

Figure 3.

Non-linear dose–response curves of BMI and mortality.

Figure 4.

Linear dose–response meta-analysis of BMI and total mortality.

BMI and breast cancer mortality

categorical meta-analysis

BMI was significantly associated with breast cancer mortality. Compared with normal weight women, for BMI before diagnosis, the summary RRs were 1.35 (95% CI 1.24–1.47, 22 studies) for obese women, 1.11 (95% CI 1.06–1.17, 21 studies) for overweight women, and 1.02 (95% CI 0.85–1.21, 8 studies) for underweight women (Figure 5). For BMI <12 months after diagnosis, the summary RRs were 1.25 (95% CI 1.10–1.42, 12 studies) for obese women, 1.11 (95% CI 1.03–1.20, 12 studies) for overweight women, and 1.53 (95% CI 1.27–1.83, 5 studies) for underweight women (supplementary Figure S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). Substantial heterogeneity was observed between studies of obese women (I2 = 53%, P = 0.02). For BMI ≥12 months after diagnosis, the summary RRs of the two studies identified were 1.68 (95% CI 0.90–3.15) for obese women and 1.37 (95% CI 0.96–1.95) for overweight women (supplementary Figure S4, available at Annals of Oncology online). The summary of another six studies that reported RRs for obese versus non-obese <12 months after diagnosis was 1.26 (95% CI 1.05–1.51, I2 = 64%, P = 0.02).

Figure 5.

Categorical meta-analysis of pre-diagnosis BMI and breast cancer mortality.

dose–response meta-analysis

There was no significant evidence of a non-linear relationship between BMI before, <12 months after, and ≥12 months after diagnosis and breast cancer mortality (P = 0.21, P = 1.00, P = 0.86, respectively) (Figure 3). When linear models were fitted excluding data from the underweight category, statistically significant increased risks of breast cancer mortality with BMI before and <12 months after diagnosis were observed (Figure 6). The summary RRs for each 5 kg/m2 increase were 1.18 (95% CI 1.12–1.25, 18 studies, 5262 breast cancer deaths) for BMI before diagnosis and 1.14 (95% CI 1.05–1.24, 8 studies, 3857 breast cancer deaths) for BMI <12 months after diagnosis, with moderate (I2 = 47%, P = 0.01) and substantial (I2 = 66%, P = 0.01) heterogeneities between studies, respectively. Only two studies on BMI ≥12 months after diagnosis and breast cancer mortality (N = 220 deaths) were identified. The summary RR was 1.29 (95% CI 0.97–1.72).

Figure 6.

Linear dose–response meta-analysis of BMI and breast cancer mortality.

BMI and other mortality outcomes

Only two studies reported results for death from cardiovascular disease (N = 151 deaths) [27, 112]. The summary RR for obese versus normal weight before diagnosis was 1.60 (95% CI 0.66–3.87). No association was observed for overweight versus normal weight (summary RR = 1.01, 95% CI 0.80–1.29). For each 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI, the summary RR was 1.21 (95% CI 0.83–1.77). Five studies reported results for deaths from any cause other than breast cancer (N = 2704 deaths) [21, 34, 108, 113, 114]. The summary RRs were 1.29 (95% CI 0.99–1.68, I2 = 72%, P = 0.01) for obese women, and 0.96 (95% CI 0.83–1.11, I2 = 26%, P = 0.25) for overweight women compared with normal weight women.

subgroup, meta-regression, and sensitivity analyses

The results of the subgroup and meta-regression analyses are in supplementary Tables S3 and S4, available at Annals of Oncology online. Subgroup analysis was not carried out for BMI ≥12 months after diagnosis as the limited number of studies would hinder any meaningful comparisons.

Increased risks of mortality were observed in the meta-analyses by menopausal status. While the summary risk estimates seem stronger with premenopausal breast cancer, there was no significant heterogeneity between pre- and post-menopausal breast cancer as shown in the meta-regression analyses (P = 0.28–0.89) (supplementary Tables S3 and S4, available at Annals of Oncology online). For BMI before diagnosis and total mortality, the summary RRs for obese versus normal weight were 1.75 (95% CI 1.26–2.41, I2 = 70%, P < 0.01, 7 studies) in women with pre-menopausal breast cancer and 1.34 (95% CI 1.18–1.53, I2 = 27%, P = 0.20, 9 studies) in women with post-menopausal breast cancer.

Studies with larger number of deaths [105, 115], conducted in Europe [28, 115], or with weight and height assessed through medical records [28, 104, 115, 116] tended to report weaker associations for BMI <12 months after diagnosis and total mortality compared with other studies (meta-regression P = 0.01, 0.02, 0.01, respectively) (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online); while studies with larger number of deaths [101], conducted in Asia [101, 102], or adjusted for co-morbidity [101, 102] reported weaker associations for BMI <12 months after diagnosis and breast cancer mortality (meta-regression P = 0.01, 0.02, 0.01, respectively) (supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Analyses stratified by study designs, or restricted to studies with invasive cases only, early-stage non-metastatic cases only, or mammography screening detected cases only, or controlled for previous diseases did not produce results that were materially different from those obtained in the overall analyses (results not shown). Summary risk estimates remained statistically significant when each study was omitted in turn, except for BMI ≥12 months after diagnosis and total mortality. The summary RR was 1.06 (95% CI 0.98–1.15) per 5 kg/m2 increase when Flatt et al. [117] which contributed 315 deaths was omitted.

small studies or publication bias

Asymmetry was only detected in the funnel plots of BMI <12 months after diagnosis and total mortality, and breast cancer mortality, which suggests that small studies with an inverse association are missing (plots not shown). Egger's tests were borderline significant (P = 0.05) or statistically significant (P = 0.03), respectively.

discussion

The present systematic literature review and meta-analysis of follow-up studies clearly supports that, in breast cancer survivors, higher BMI is consistently associated with lower overall and breast cancer survival, regardless of when BMI is ascertained. The limited number of studies on death from cardiovascular disease is also consistent with a positive association. For before, <12 months after, and 12 months or more after breast cancer diagnosis, compared with normal weight women, obese women had 41%, 23%, and 21% higher risk for total mortality, and 35%, 25%, and 68% increased risk for breast cancer mortality, respectively. The findings were supported by the positive associations observed in the linear dose–response meta-analysis. All associations were statistically significant, apart from the relationship between BMI ≥12 months after diagnosis and breast cancer mortality. This may be due to limited statistical power, with only 220 breast cancer deaths from two follow-up studies.

Positive associations, in some cases statistically significant, were also observed in overweight, and underweight women compared with normal weight women. Women with BMI of 20 kg/m2 before, or <12 months after diagnosis, and of 25 kg/m2 12 months or more after diagnosis appeared to have the lowest mortality risk in the non-linear dose–response analysis. Co-morbid conditions may cause the observed increased risk in underweight women. Thorough investigation within the group and on their contribution to the shape of the association is hindered, as not all studies in this review reported results for this group. The increased risk associated with obesity was similar in pre- or post-menopausal breast cancer. We did not find any evidence of a protective effect of obesity on survival after pre-menopausal breast cancer, contrary to what has been observed for the development of breast cancer in pre-menopausal women [4].

A large body of evidence with 41 477 deaths (23 182 from breast cancer) in over 210 000 breast cancer survivors was systematically reviewed in the present study. We carried out categorical, linear, and non-linear dose–response meta-analyses to examine the magnitude and the shape of the associations for total and cause-specific mortality in underweight, overweight, and obese women by time periods before and after diagnosis that is important in relation to the population-at-risk and breast cancer survivors. Our findings agree with and further extend the results from previous meta-analyses. A review published in 2010 reported statistically significant increased risks of 33% of both total and breast cancer mortality for obesity versus non-obesity around diagnosis [7]. These estimates are slightly higher than ours, which may be explained by the different search periods and inclusion criteria for the articles (33 studies and 15 studies included in the analyses, respectively). Another review published in 2012 further reported consistent positive associations of total and breast cancer mortality with higher versus lower BMI around diagnosis [6]. No significant differences were observed by menopausal status or hormone receptor status. The After Breast Cancer Pooling Project of four prospective cohort studies found differential effects of levels of pre-diagnosis obesity on survival [118]. Compared with normal weight women, significant or borderline significant increased risks of 81% of total and 40% of breast cancer mortality were only observed for morbidly obese (≥40 kg/m2) women and not for women in other obesity categories. We observed statistically significant increased risks also for overweight women, probably because of a larger number of studies. We were unable to investigate the associations with severely and morbidly obese women because only two studies included in this review reported such results [19, 113]. Overall, our findings are consistent with previous meta-analyses in showing elevated total and breast cancer mortality associated with higher BMI and support the current guidelines for breast cancer survivors to stay as lean as possible within the normal range of body weight [4], for overweight women to avoid weight gain during treatment and for obese women to lose weight after treatment [119].

The present review is limited by the challenges and flaws encountered by the individual epidemiological studies evaluating the body fatness–mortality relationship in breast cancer survivors. Most studies did not adjust for co-morbidities and assess intentional weight loss. Women with more serious health issues, and especially smokers, may lose weight but are at an increased risk of mortality, and this might cause an apparent increased risk in underweight women. Body weight information through the natural history of the disease and treatment information were usually not complete or available. Increase of body weight post-diagnosis is common in women with breast cancer, particularly during chemotherapy [16]. Chemotherapy under-dosing is a common problem in obese women and may contribute to their increased mortality [120]. Although several studies with pre-diagnosis BMI adjusted for underlying illnesses or excluded the first few years of follow-up, reverse causation may have affected the results in studies that assessed BMI in women with cancer and other illnesses. However, in these studies, the associations were similar to other studies. Possible survival benefit (subjects with better prognostic factors survive) may be present in the survival cohorts, in which the range of BMI could be narrower, and may cause an underestimation of the association.

Follow-up studies with variable characteristics were pooled in the meta-analysis. Women identified in clinical trials may have had specific tumour subtypes, with fewer co-morbidities, and were more likely to receive protocol treatments with high treatment completion rates. Women who were recruited through mammography screening programmes may have had healthier lifestyles or access to medical facilities, and more likely to be diagnosed with in situ or early-stage breast cancer. Cancer detection methods, tumour classifications and treatment regimens change over time, and may vary within (if follow-up is long) and between studies, and could not be simply examined by using the diagnosis or treatment date. We cannot rule out the effect of unmeasured or residual confounding in our analysis. Nevertheless, most results were adjusted for multiple confounding factors, including tumour stage or other-related variables and stratified analyses by several key factors showed similar summary risk estimates. Small study or publication bias was observed in the analyses of BMI <12 months after diagnosis. However, the overall evidence is supported by large, well-designed studies and is unlikely to be changed. We did not conduct analyses by race/ethnicity and treatment types as only limited studies had published results.

Future studies of body fatness and breast cancer outcomes should aim to account for co-morbidities, separate intended and unintended changes of body weight, and collect complete treatment information during study follow-up. Randomised clinical trials are needed to test interventions for weight loss and maintenance on survival in women with breast cancer.

In conclusion, the present systematic literature review and meta-analysis extends and confirms the associations of obesity with an unfavourable overall and breast cancer survival in pre- and post-menopausal breast cancer, regardless of when BMI is ascertained. Increased risks of mortality in underweight and overweight women were also observed. Given the comparable elevated risks with obesity in the development (for post-menopausal women) and prognosis of breast cancer, and the complications with cancer treatment and other obesity-related co-morbidities, it is prudent to maintain a healthy body weight (BMI 18.5–<25.0 kg/m2) throughout life.

funding

This work was supported by the World Cancer Research Fund International (grant number: 2007/SP01) (http://www.wcrf-uk.org/). The funder of this study had no role in the decisions about the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The views expressed in this review are the opinions of the authors. They may not represent the views of the World Cancer Research Fund International/American Institute for Cancer Research and may differ from those in future updates of the evidence related to food, nutrition, physical activity, and cancer survival.

disclosure

DCG reports personal fees from World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research, during the conduct of the study; grants from Danone, and grants from Kelloggs, outside the submitted work. AM reports personal fees from Metagenics/Metaproteomics, personal fees from Pfizer, outside the submitted work. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

TN is the principal investigator of the Continuous Update Project at Imperial College London. TN and DSMC wrote the protocol and implemented the study with the advice of an expert committee convened by WCRF. RV developed and managed the database for the Continuous Update Project. DSMC, TN, and DA did the literature search and study selections. DSMC, ARV, and DNR did the data extraction. DSMC carried out the statistical analyses. DCG was statistical adviser and contributed to the statistical analyses. DSMC wrote the first draft of the original manuscript. EB, AM, and IT are panel members of the Continuous Update Project and advised on the interpretation of the review. All authors revised the manuscript. DSMC takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

references

- 1.American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2011–2012. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, Inc.; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maddams J, Brewster D, Gavin A, et al. Cancer prevalence in the United Kingdom: estimates for 2008. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:541–547. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finucane MM, Stevens GA, Cowan MJ, et al. National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9.1 million participants. Lancet. 2011;377:557–567. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective. Washington DC: AICR; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ligibel J. Obesity and breast cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 2011;25:994–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niraula S, Ocana A, Ennis M, et al. Body size and breast cancer prognosis in relation to hormone receptor and menopausal status: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134:769–781. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Protani M, Coory M, Martin JH. Effect of obesity on survival of women with breast cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:627–635. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0990-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pekmezi DW, Demark-Wahnefried W. Updated evidence in support of diet and exercise interventions in cancer survivors. Acta Oncol. 2011;50:167–178. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.529822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hursting SD, Berger NA. Energy balance, host-related factors, and cancer progression. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4058–4065. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.27.9935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lonning PE. Aromatase inhibition for breast cancer treatment. Acta Oncol. 1996;35(Suppl 5):38–43. doi: 10.3109/02841869609083966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodwin PJ, Ennis M, Bahl M, et al. High insulin levels in newly diagnosed breast cancer patients reflect underlying insulin resistance and are associated with components of the insulin resistance syndrome. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;114:517–525. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodwin PJ, Ennis M, Fantus IG, et al. Is leptin a mediator of adverse prognostic effects of obesity in breast cancer? J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6037–6042. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pierce BL, Ballard-Barbash R, Bernstein L, et al. Elevated biomarkers of inflammation are associated with reduced survival among breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3437–3444. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.9068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenman CG, Jagielski CH, Griggs JJ. Breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy dosing in obese patients: dissemination of information from clinical trials to clinical practice. Cancer. 2008;112:2159–2165. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryu SY, Kim CB, Nam CM, et al. Is body mass index the prognostic factor in breast cancer? A meta-analysis. J Korean Med Sci. 2001;16:610–614. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2001.16.5.610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demark-Wahnefried W, Campbell KL, Hayes SC. Weight management and its role in breast cancer rehabilitation. Cancer. 2012;118:2277–2287. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.2013. World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research: Continuous Update Project (CUP)

- 18.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Azambuja E, Caskill-Stevens W, Francis P, et al. The effect of body mass index on overall and disease-free survival in node-positive breast cancer patients treated with docetaxel and doxorubicin-containing adjuvant chemotherapy: the experience of the BIG 02–98 trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;119:145–153. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0512-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vitolins MZ, Kimmick GG, Case LD. BMI influences prognosis following surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy for lymph node positive breast cancer. Breast J. 2008;14:357–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2008.00598.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sestak I, Distler W, Forbes JF, et al. Effect of body mass index on recurrences in tamoxifen and anastrozole treated women: an exploratory analysis from the ATAC trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3411–3415. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamling J, Lee P, Weitkunat R, et al. Facilitating meta-analyses by deriving relative effect and precision estimates for alternative comparisons from a set of estimates presented by exposure level or disease category. Stat Med. 2008;27:954–970. doi: 10.1002/sim.3013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Royston P, Ambler G, Sauerbrei W. The use of fractional polynomials to model continuous risk variables in epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:964–974. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.5.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bagnardi V, Zambon A, Quatto P, et al. Flexible meta-regression functions for modeling aggregate dose-response data, with an application to alcohol and mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:1077–1086. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orsini N, Bellocco R, Greenland S. Generalized least squares for trend estimation of summarized dose-response data. Stata J. 2006;6:40–57. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bekkering GE, Harris RJ, Thomas S, et al. How much of the data published in observational studies of the association between diet and prostate or bladder cancer is usable for meta-analysis? Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:1017–1026. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reeves KW, Faulkner K, Modugno F, et al. Body mass index and mortality among older breast cancer survivors in the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:1468–1473. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baumgartner AK, Hausler A, Seifert-Klauss V, et al. Breast cancer after hormone replacement therapy—does prognosis differ in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women? Breast. 2011;20:448–454. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cleveland RJ, Eng SM, Abrahamson PE, et al. Weight gain prior to diagnosis and survival from breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:1803–1811. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tretli S, Haldorsen T, Ottestad L. The effect of pre-morbid height and weight on the survival of breast cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 1990;62:299–303. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1990.282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sparano JA, Wang M, Zhao F, et al. Obesity at diagnosis is associated with inferior outcomes in hormone receptor-positive operable breast cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:5937–5946. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu Y, Ma H, Malone KE, et al. Obesity and survival among black women and white women 35 to 64 years of age at diagnosis with invasive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3358–3365. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olsson A, Garne JP, Tengrup I, et al. Body mass index and breast cancer survival in relation to the introduction of mammographic screening. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:1261–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Connor AE, Baumgartner RN, Pinkston C, et al. Obesity and risk of breast cancer mortality in Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women: the New Mexico Women's Health Study. J Women's Health. 2013;22:368–377. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.4191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sterne JA, Gavaghan D, Egger M. Publication and related bias in meta-analysis: power of statistical tests and prevalence in the literature. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:1119–1129. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00242-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tobias A. Assessing the influence of a single study in meta-analysis. Stata Tech Bull. 1999;47:15–17. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abe R, Kumagai N, Kimura M, et al. Biological characteristics of breast cancer in obesity. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1976;120:351–359. doi: 10.1620/tjem.120.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bastarrachea J, Hortobagyi GN, Smith TL, et al. Obesity as an adverse prognostic factor for patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:18–25. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-1-199401010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Donegan WL, Jayich S, Koehler MR. The prognostic implications of obesity for the surgical cure of breast cancer. Breast. 1978;4:14–17. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nomura AM, Marchand LL, Kolonel LN, et al. The effect of dietary fat on breast cancer survival among Caucasian and japanese women in Hawaii. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1991;18(Suppl. 1):S135–S141. doi: 10.1007/BF02633546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Albain KS, Green S, LeBlanc M, et al. Proportional hazards and recursive partitioning and amalgamation analyses of the Southwest Oncology Group node-positive adjuvant CMFVP breast cancer data base: a pilot study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1992;22:273–284. doi: 10.1007/BF01840840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bergmann A, Bourrus NS, de Carvalho CM, et al. Arm symptoms and overall survival in Brazilian patients with advanced breast cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:2939–2942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coates RJ, Clark WS, Eley JW, et al. Race, nutritional status, and survival from breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990;82:1684–1692. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.21.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crujeiras AB, Cueva J, Vieito M, et al. Association of breast cancer and obesity in a homogeneous population from Spain. J Endocrinol Invest. 2012;35:681–685. doi: 10.3275/8370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kimura M. Obesity as prognostic factors in breast cancer. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1990;10:S247–S251. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(90)90171-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lara-Medina F, Perez-Sanchez V, Saavedra-Perez D, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer in Hispanic patients: high prevalence, poor prognosis, and association with menopausal status, body mass index, and parity. Cancer. 2011;117:3658–3669. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lethaby AE, Mason BH, Harvey VJ, et al. Survival of women with node negative breast cancer in the Auckland region. N Z Med J. 1996;109:330–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sendur MAN, Aksoy S, Zengin N, et al. Efficacy of adjuvant aromatase inhibitor in hormone receptor-positive postmenopausal breast cancer patients according to the body mass index. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:1815–1819. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singh AK, Pandey A, Tewari M, et al. Obesity augmented breast cancer risk: a potential risk factor for Indian women. J Surg Oncol. 2011;103:217–222. doi: 10.1002/jso.21768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taylor SG, Knuiman MW, Sleeper LA, et al. Six-year results of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trial of observation versus CMFP versus CMFPT in postmenopausal patients with node-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:879–889. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1989.7.7.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Loehberg CR, Almstedt K, Jud SM, et al. Prognostic relevance of Ki-67 in the primary tumor for survival after a diagnosis of distant metastasis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;138:899–908. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2460-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mousa U, Onur H, Utkan G. Is obesity always a risk factor for all breast cancer patients? c-erbB2 expression is significantly lower in obese patients with early stage breast cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2012;14:923–930. doi: 10.1007/s12094-012-0878-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anderson SJ, Wapnir I, Dignam JJ, et al. Prognosis after ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence and locoregional recurrences in patients treated by breast-conserving therapy in five National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project protocols of node-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2466–2473. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bayraktar S, Hernadez-Aya LF, Lei X, et al. Effect of metformin on survival outcomes in diabetic patients with triple receptor-negative breast cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:1202–1211. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Daling JR, Malone KE, Doody DR, et al. Relation of body mass index to tumor markers and survival among young women with invasive ductal breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2001;92:720–729. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010815)92:4<720::aid-cncr1375>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eralp Y, Smith TL, Altundag K, et al. Clinical features associated with a favorable outcome following neoadjuvant chemotherapy in women with localized breast cancer aged 35 years or younger. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2009;135:141–148. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0428-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ewertz M. Breast cancer in Denmark. Incidence, risk factors, and characteristics of survival. Acta Oncol. 1993;32:595–615. doi: 10.3109/02841869309092438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ganz PA, Habel LA, Weltzien EK, et al. Examining the influence of beta blockers and ACE inhibitors on the risk for breast cancer recurrence: results from the LACE cohort. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;129:549–556. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1505-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Goodwin PJ, Ennis M, Pritchard KI, et al. Fasting insulin and outcome in early-stage breast cancer: results of a prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:42–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Greenberg ER, Vessey MP, McPherson K, et al. Body size and survival in premenopausal breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1985;51:691–697. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1985.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Holmes MD, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, et al. Dietary factors and the survival of women with breast carcinoma.[Erratum appears in Cancer 1999 Dec 15;86(12):2707–8] Cancer. 1999;86:826–835. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990901)86:5<826::aid-cncr19>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jain M, Miller AB. Tumor characteristics and survival of breast cancer patients in relation to premorbid diet and body size. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1997;42:43–55. doi: 10.1023/a:1005798124538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jung SY, Sereika SM, Linkov F, et al. The effect of delays in treatment for breast cancer metastasis on survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130:953–964. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1662-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maehle BO, Tretli S. Pre-morbid body-mass-index in breast cancer: reversed effect on survival in hormone receptor negative patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1996;41:123–130. doi: 10.1007/BF01807157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shu XO, Zheng Y, Cai H, et al. Soy food intake and breast cancer survival. JAMA. 2009;302:2437–2443. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sparano JA, Wang M, Zhao F, et al. Race and hormone receptor-positive breast cancer outcomes in a randomized chemotherapy trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:406–414. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vatten LJ, Foss OP, Kvinnsland S. Overall survival of breast cancer patients in relation to preclinically determined total serum cholesterol, body mass index, height and cigarette smoking: a population-based study. Eur J Cancer. 1991;27:641–646. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(91)90234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Allemani C, Berrino F, Krogh V, et al. Do pre-diagnostic drinking habits influence breast cancer survival? Tumori. 2011;97:142–148. doi: 10.1177/030089161109700202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gregorio DI, Emrich LJ, Graham S, et al. Dietary fat consumption and survival among women with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1985;75:37–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kyogoku S, Hirohata T, Takeshita S, et al. Survival of breast-cancer patients and body size indicators. Int J Cancer. 1990;46:824–831. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910460513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mohle-Boetani JC, Grosser S, Whittemore AS, et al. Body size, reproductive factors, and breast cancer survival. Prev Med. 1988;17:634–642. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(88)90056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Suissa S, Pollak M, Spitzer WO, et al. Body size and breast cancer prognosis: a statistical explanation of the discrepancies. Cancer Res. 1989;49:3113–3116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Allin KH, Nordestgaard BG, Flyger H, et al. Elevated pre-treatment levels of plasma C-reactive protein are associated with poor prognosis after breast cancer: a cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:R55. doi: 10.1186/bcr2891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.den Tonkelaar I, de WF, Seidell JC, et al. Obesity and subcutaneous fat patterning in relation to survival of postmenopausal breast cancer patients participating in the DOM-project. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1995;34:129–137. doi: 10.1007/BF00665785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Eley JW, Hill HA, Chen VW, et al. Racial differences in survival from breast cancer. Results of the National Cancer Institute Black/White Cancer Survival Study. JAMA. 1994;272:947–954. doi: 10.1001/jama.272.12.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gordon NH, Crowe JP, Brumberg DJ, et al. Socioeconomic factors and race in breast cancer recurrence and survival. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135:609–618. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Menon KV, Hodge A, Houghton J, et al. Body mass index, height and cumulative menstrual cycles at the time of diagnosis are not risk factors for poor outcome in breast cancer. Breast. 1999;8:328–333. doi: 10.1054/brst.1999.0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rohan TE, Hiller JE, McMichael AJ. Dietary factors and survival from breast cancer. Nutr Cancer. 1993;20:167–177. doi: 10.1080/01635589309514283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Saxe GA, Rock CL, Wicha MS, et al. Diet and risk for breast cancer recurrence and survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1999;53:241–253. doi: 10.1023/a:1006190820231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schuetz F, Diel IJ, Pueschel M, et al. Reduced incidence of distant metastases and lower mortality in 1072 patients with breast cancer with a history of hormone replacement therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:342–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.10.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tammemagi CM, Nerenz D, Neslund-Dudas C, et al. Comorbidity and survival disparities among black and white patients with breast cancer. JAMA. 2005;294:1765–1772. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.14.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Enger SM, Bernstein L. Exercise activity, body size and premenopausal breast cancer survival. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:2138–2141. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Holmberg L, Lund E, Bergstrom R, et al. Oral contraceptives and prognosis in breast cancer: effects of duration, latency, recency, age at first use and relation to parity and body mass index in young women with breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A:351–354. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90255-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Reding KW, Daling JR, Doody DR, et al. Effect of prediagnostic alcohol consumption on survival after breast cancer in young women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:1988–1996. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Alsaker MDK, Opdahl S, Asvold BO, et al. The association of reproductive factors and breastfeeding with long term survival from breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130:175–182. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1566-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Buck K, Vrieling A, Zaineddin AK, et al. Serum enterolactone and prognosis of postmenopausal breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3730–3738. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.6478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Clough-Gorr KM, Ganz PA, Silliman RA. Older breast cancer survivors: factors associated with self-reported symptoms of persistent lymphedema over 7 years of follow-up. Breast J. 2010;16:147–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2009.00878.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Conroy SM, Maskarinec G, Wilkens LR, et al. Obesity and breast cancer survival in ethnically diverse postmenopausal women: the Multiethnic Cohort Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;129:565–574. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1468-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Katoh A, Watzlaf VJ, D'Amico F. An examination of obesity and breast cancer survival in post-menopausal women. Br J Cancer. 1994;70:928–933. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rosenberg L, Czene K, Hall P. Obesity and poor breast cancer prognosis: an illusion because of hormone replacement therapy? Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1486–1491. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schairer C, Gail M, Byrne C, et al. Estrogen replacement therapy and breast cancer survival in a large screening study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:264–270. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.3.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhang S, Folsom AR, Sellers TA, et al. Better breast cancer survival for postmenopausal women who are less overweight and eat less fat. The Iowa Women's Health Study. Cancer. 1995;76:275–283. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950715)76:2<275::aid-cncr2820760218>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pfeiler G, Stoger H, Dubsky P, et al. Efficacy of tamoxifen+/-aminoglutethimide in normal weight and overweight postmenopausal patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: an analysis of 1509 patients of the ABCSG-06 trial. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:1408–1414. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Loi S, Milne RL, Friedlander ML, et al. Obesity and outcomes in premenopausal and postmenopausal breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1686–1691. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mason BH, Holdaway IM, Stewart AW, et al. Season of tumour detection influences factors predicting survival of patients with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1990;15:27–37. doi: 10.1007/BF01811887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Moon HG, Han W, Noh DY. Underweight and breast cancer recurrence and death: a report from the Korean Breast Cancer Society. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5899–5905. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.4436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lee K-H, Keam B, Im S-A, et al. Body mass index is not associated with treatment outcomes of breast cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy: Korean data. J Breast Cancer. 2012;15:427–433. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2012.15.4.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chen X, Lu W, Zheng W, et al. Obesity and weight change in relation to breast cancer survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;122:823–833. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0708-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tao MH, Shu XO, Ruan ZX, et al. Association of overweight with breast cancer survival. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:101–107. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hou G, Zhang S, Zhang X, et al. Clinical pathological characteristics and prognostic analysis of 1,013 breast cancer patients with diabetes. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;137:807–816. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2404-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kawai M, Minami Y, Nishino Y, et al. Body mass index and survival after breast cancer diagnosis in Japanese women. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:149. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Labidi SI, Mrad K, Mezlini A, et al. Inflammatory breast cancer in Tunisia in the era of multimodality therapy. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:473–480. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Berclaz G, Li S, Price KN, et al. Body mass index as a prognostic feature in operable breast cancer: the International Breast Cancer Study Group experience. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:875–884. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ewertz M, Gray KP, Regan MM, et al. Obesity and risk of recurrence or death after adjuvant endocrine therapy with letrozole or tamoxifen in the breast international group 1–98 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3967–3975. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.8666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Keegan TH, Milne RL, Andrulis IL, et al. Past recreational physical activity, body size, and all-cause mortality following breast cancer diagnosis: results from the Breast Cancer Family Registry. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:531–542. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0774-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.von Drygalski A, Tran TB, Messer K, et al. Obesity is an independent predictor of poor survival in metastatic breast cancer: retrospective analysis of a patient cohort whose treatment included high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell support. Int J Breast Cancer. 2011:523276. doi: 10.4061/2011/523276. doi:10.4061/2011/523276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ewertz M, Jensen MB, Gunnarsdottir KA, et al. Effect of obesity on prognosis after early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:25–31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.7614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tornberg S, Carstensen J. Serum beta-lipoprotein, serum cholesterol and Quetelet's index as predictors for survival of breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 1993;29A:2025–2030. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(93)90466-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Newman SC, Lees AW, Jenkins HJ. The effect of body mass index and oestrogen receptor level on survival of breast cancer patients. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:484–490. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.3.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ademuyiwa FO, Groman A, O'Connor T, et al. Impact of body mass index on clinical outcomes in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer. 2011;117:4132–4140. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Nichols HB, Trentham-Dietz A, Egan KM, et al. Body mass index before and after breast cancer diagnosis: associations with all-cause, breast cancer, and cardiovascular disease mortality. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:1403–1409. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Dignam JJ, Wieand K, Johnson KA, et al. Effects of obesity and race on prognosis in lymph node-negative, estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;97:245–254. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9118-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Dignam JJ, Wieand K, Johnson KA, et al. Obesity, tamoxifen use, and outcomes in women with estrogen receptor-positive early-stage breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1467–1476. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Majed B, Moreau T, Senouci K, et al. Is obesity an independent prognosis factor in woman breast cancer? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;111:329–342. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9785-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Dawood S, Broglio K, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, et al. Prognostic value of body mass index in locally advanced breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1718–1725. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Flatt SW, Thomson CA, Gold EB, et al. Low to moderate alcohol intake is not associated with increased mortality after breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:681–688. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kwan ML, Chen WY, Kroenke CH, et al. Pre-diagnosis body mass index and survival after breast cancer in the After Breast Cancer Pooling Project. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132:729–739. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1914-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Rock CL, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W, et al. Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:243–274. doi: 10.3322/caac.21142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Griggs JJ, Mangu PB, Anderson H, et al. Appropriate chemotherapy dosing for obese adult patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1553–1561. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.9436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.