Abstract

Objective

Mutations of transmembrane channel-like 1 gene (TMC1) can cause dominant (DFNA36) or recessive (DFNB7/B11) deafness. In this article, we describe the characteristics of DFNA36 and DFNB7/B11 deafness, the features of the Tmc1 mutant mouse strains, and recent advances in our understanding of TMC1 function.

Methods

Publications related to TMC1, DFNA36 or DFNB7/B11 were identified through PubMed.

Results

All affected DFNA36 subjects showed post-lingual, progressive, sensorineural hearing loss (HL), initially affecting high frequencies. In contrast, almost all affected DFNB7/B11 subjects demonstrated congenital or prelingual severe to profound sensorineural HL. The mouse Tmc1 gene also has dominant and recessive mutant alleles that cause HL in mutant strains, including Beethoven, deafness and Tmc1 knockout mice. These mutant mice have been instrumental for revealing that Tmc1 and its closely related paralog Tmc2 are expressed in cochlear and vestibular hair cells, and are required for hair cell mechanoelectrical transduction (MET). Recent studies suggest that TMC1 and TMC2 may be components of the long-sought hair cell MET channel.

Conclusion

TMC1 mutations disrupt hair cell MET.

Keywords: DFNA36, DFNB7/B11, Hearing loss, Mechanoelectrical transduction, TMC1, TMC2

Introduction

Hearing loss (HL) affects approximately one in 500 newborns and 4% of people 45 years of age and younger [1], reaching 50% by 80 years of age [2]. It is estimated that 278 million people worldwide have HL [3,4].

More than 50% of cases of congenital deafness are thought to have a genetic etiology [5], while the other cases are caused by environmental factors including exposure to ototoxic drugs or congenital cytomegalovirus infection [6]. Within the group that is considered to have a genetic cause, approximately 30% of cases present with other clinical features in addition to HL and is termed syndromic HL. The remaining 70% shows HL without additional overt clinical features, and is called nonsyndromic HL [7]. Approximately 70% of cases of nonsyndromic HL are autosomal recessive in inheritance, 25% are autosomal dominant, and X-linked and mitochondrial inheritance account for the remaining few percent [8,9]. Depending on the inheritance mode, the nonsyndromic phenotypes and loci are classified as: DFNA (autosomal dominant), DFNB (autosomal recessive), DFNX (X-linked) or DFNY (Y-linked). DFNM denotes modifier loci for which there are alleles that modify the HL phenotypes caused by mutations at another locus.

The strategy to identify genes for HL through a positional cloning approach has been successful over the past two decades. Linkage analysis with microsatellite markers and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) has been used widely, allowing the chromosomal locations of deafness genes to be mapped in large families. Following identification and refinement of the linkage loci, dideoxy (Sanger) sequencing has been used to analyze the genes within the critical interval, which has led to the identification of the causative mutations. In addition to studies of human families, some deafness genes have been identified from analogous analyses of spontaneous or chemically induced mutations in the mouse. Candidate gene approaches, in the absence of statistically significant linkage or association analyses or a closely corresponding animal model, have not yet yielded conclusive results. To date, 74 genes are known or proposed to be involved in nonsyndromic HL (http://hereditaryhearingloss.org/ accessed on February 12, 2014). More genes will more certainly be discovered, since the causative genes at over 50 deafness loci have not yet been identified. The genes identified to date encode many different proteins with a large variety of functions in the inner ear, including gene regulation, development, ionic and osmotic homeostasis, synaptic transmission, hair cell bundle morphology, generation of the endocochlear potential, and mechanoelectrical transduction (MET) [10,11].

Hair cells have a critical role in transducing mechanical forces evoked by sound, or linear or angular accelerations of the head into an electrical signal. The apical surface of hair cells contains stereocilia, which play a pivotal role in this mechanism. The stereocilia have a typical staircase arrangement, and are connected with lateral and tip links stabilizing the mature hair bundle structure [12,13]. The tip link connects the top of a stereocilium with the side of its taller neighbor [14–16], and gates the opening of the MET channel(s) located at the tip of the shorter stereocilium [17–21]. Numerous candidates for the hair cell MET have emerged over the past 15 years, but none have withstood rigorous scientific scrutiny [22].

In this review, we highlight the transmembrane channel-like 1 (TMC1) gene, which was identified as the gene mutated in DFNA36 and DFNB7/B11 deafness [23]. First, we introduce the identification of TMC1 as a deafness-causing gene, and describe the phenotype and mutation spectrum of DFNA36 and DFNB7/B11 patients. Next, we review mutant mouse models of human DFNA36 and DFNB7/B11 deafness, which have been instrumental for revealing the hair cell expression and function of TMC1. Recent experiments using these mouse models revealed that Tmc1 and the closely related Tmc2 genes are required for MET and might encode components of the MET channel [24,25].

Identification of TMC1 as a causative gene for DFNA36 and DFNB7/B11 deafness

TMC1 was identified as the causative gene of DFNA36 and DFNB7/B11 deafness through positional cloning [23]. The DFNA36 interval had been mapped to chromosome 9q13-q21 by linkage analysis of a large North American family, LMG128, segregating autosomal dominant, nonsyndromic, sensorineural HL. Genotype analysis of markers linked to known nonsyndromic recessive deafness loci had revealed that the DFNA36 region overlapped the DFNB7/B11 linkage interval. Linkage analysis of approximately 230 Indian or Pakistani consanguineous families segregating autosomal recessive, nonsyndromic, sensorineural HL identified 11 additional families showing linkage to the DFNB7/B11 locus. Within this linkage interval, dideoxy sequencing of the TMC1 gene revealed p.D572N (c.1714G>A) segregating in family LMG128, as well as one of eight otherpathogenic mutations segregating among each of the ten DFNB7/B11 families. These findings showed that DFNA36 and DFNB7/B11 were allelic disorders caused by mutations of TMC1.

TMC1 spans approximately 300 kb on chromosome 9q21, and consists of 24 exons that make up a coding region of 2283 nucleotides [23]. It is a member of the transmembrane channel-like (TMC) gene family that includes seven other paralogs in mammals (TMC2 to TMC8) [26]. At the time, the function of the TMC genes was unknown, and in silico translation products showed no significant sequences similarity to proteins or domains of known function. However, all were predicted to encode membrane proteins with at least six membrane-spanning domains [26]. The six-pass transmembrane topology was experimentally confirmed for mouse TMC1 expressed in heterologous systems and suggested that it might function as a receptor, transporter, pump, or channel [27].

TMC genes have been implicated in other human diseases and disorders. Recessive mutations of TMC6 (also designated as EVER1) or TMC8 (EVER2) cause epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EV), which is characterized by abnormal susceptibility to infection by specific subtypes of human papillomaviruses with a high risk of progression to skin carcinoma [28]. The disease was reviewed in detail by Orth [29] and Patel et al. [30]. It has been proposed that the site of the functional lesion of EV is either in keratinocytes or T lymphocytes [29,31]. However the molecular pathogenesis of EV and the function of TMC6 and TMC8 thus remain unknown, although one report described an abnormality in zinc transport [32]. It is unclear if this observation was a direct or indirect effect of heterologous overexpression in these cells.

Phenotype and mutation spectrum of DFNA36 subjects

Three different missense mutations, p.G417R (c.1249G>A), p.D572H (c.1714G>C) and p.D572N (c.1714G>A), have been reported to cause autosomal dominant HL at the DFNA36 locus (Table 1) [23,33–35]. Families L1754 and LMG248 segregate p.G417R and p.D572N, respectively. Families LMG248 and H segregate p.D572H.

Table 1.

Clinical phenotypes of DFNA36 patients

| Family | Origin | Nucleotide mutation a | Predicted effect | Exon number | Onset of HL | Severity of HL | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1754 | Iran | c.1249G>A | p.G417R | Exon 16 | Postlingual | Severe to profound 2nd decade: all frequencies Rapid progression b |

Yang et al. [35] |

| LMG248 | North America (Caucasian) | c.1714G>C | p.D572H | Exon 19 | Postlingual | Profound 2nd decade: high frequencies 4th–5th decade: all frequencies |

Kitajiri et al. [33] |

| LMG128 | North America (Caucasian) | c.1714G>A | p.D572N | Exon 19 | Postlingual | Profound 1st decade: mid and high frequencies 2nd decade: all frequencies |

Kurima et al. [23] Makishima et al. [36] |

| Family H | North America (Caucasian) | c.1714G>A | p.D572N | Exon 19 | Postlingual | Severe to profound 1st decade: mid and high frequencies Rapid progression b |

Hilgert et al. [34] |

Abbreviation: HL, hearing loss.

The numbering is based on cDNA sequence (GenBank accession number: NM_138691.2).

Detailed time course was not described.

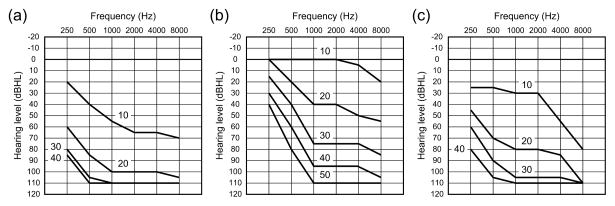

All of the affected members of families L1754, LMG248, LMG128 and H show post-lingual, progressive and symmetrical sensorineural HL initially affecting high frequencies, although there are variations in the age of onset and rate of progression [33–36]. In LMG128 family members carrying p.D572N, HL became evident in the first decade of life and rapidly progressed to severe to profound deafness by the second decade of life (Fig. 1a). The calculated rate of progression was 5.9 dB/year before 20 years of age. After the age of 20 years, the rate of progression was less than 1 dB/year. This slower rate at older ages reflects a ceiling effect due to the elevated thresholds [36]. In contrast, HL in LMG248 family members with the p.D572H mutation began in the second decade of life and progressed to profound levels by the fourth or fifth decade (Fig. 1b). The rate of progression in family LMG248 was significantly slower than that in family LMG128 for all stimulus test frequencies, although the calculated progression rate was not reported [33]. This difference may reflect differing effects of these substitution mutations, different genetic backgrounds, or both.

Fig. 1.

Age-related typical audiograms for three families, LMG128, LMG248 and W06-792. (a) In LMG128, hearing loss was evident in the first decade of life and rapidly progressed to severe to profound deafness by the second decade of life. (b) In LMG248, hearing loss was reported in the second decade of life and progressed to profound levels by the fourth or fifth decade. (c) In family W06-792, hearing loss was noticed in the first to second decade, starting at high frequencies and rapidly progressing to severe to profound levels in the third or fourth decade. Numbers near the lines in the graph indicate ages in decade steps. We estimated age-matched hearing thresholds by plotting audiogram data of all the affected subjects in each frequency and depicting a polynomial trendline using the Mac version of Microsoft Excel.

Affected subjects with DFNA mutations typically do not have vestibular symptoms. Although three of 13 affected members of family LMG128 reported various vestibular symptoms, they were not recurrent and were unaccompanied by tinnitus or fluctuations of hearing [36]. In combination with incomplete penetrance of the vestibular phenotype, Makishima et al. [36] suggested that vestibular symptoms were not related to DFNA36. Their observation was consistent with a lack of associated vestibular signs or symptoms in family LMG248 [33].

Remarkably, two different missense mutations, p.D572H and p.D572N, affect the same nucleotide and amino acid of TMC1. Of these, p.D572N was identified in families LMG128 and H. To determine if the p.D572N mutation was derived from a common founder, Hilgert et al. [34] compared TMC1-linked haplotypes of short tandem repeat (STR) markers and SNPs between the two families. They demonstrated several differences in the linked haplotypes and concluded that families LMG128 and H most likely did not have a common founder. The result indicates that c.1714G is a possible hot spot for mutations that arose independently in DFNA36 families, the p.D572 residue or the mutated residues are associated with a critical function or gain-of-function, or a combination of these possibilities.

Phenotype and mutation spectrum of DFNB7/B11 subjects

To date, 39 mutations have been reported to be associated with autosomal recessive HL at the DFNB7/B11 locus among 60 families. These families have their origins in Pakistan, Turkey, Tunisia, Iran, Lebanon/Jordan, North America, China, Europe, Sudan and Morocco (Table 2) [23,35,37–48]. These 39 mutations are widely distributed throughout the entire coding region of TMC1. Some mutations, including c.64+2T>A, p.R34X, c.536-8T>A, p.R389X, p.R445H, c.1763+3A>G, p.R604X and p.S668R, were identified in multiple unrelated families [23,37,38,40–47]. p.R34X was identified in 10 different Pakistan families in addition to 6 families from Tunisia, Iran, Lebanon/Jordan and Turkey [23,40–43]. To examine if p.R34X arose from a common founder, Kitajiri et al. [40] studied the TMC1-linked haplotypes of STR markers and SNPs for the 10 independent p.R34X chromosomes. They demonstrated that all of the 10 chromosomes have identical combinations of STR markers and suggested that the Pakistani p.R34X mutation was derived from a common founder.

Table 2.

Clinical phenotypes of DFNB7/B11 patients

| Family | Origin | Nucleotide mutation a | Predicted effect | Exon/Intron number | Onset of HL | Severity of HL | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homozygous state b | |||||||

| PKDF22 | Pakistan | c.-195_16del d | Genomic deletion | Prelingual | Severe to profound | Kurima et al. [23] | |

| PKDF274 | Pakistan | c.16+1G>T | Splice disruption | Intron 5 | Prelingual | Severe to profound | Kitajiri et al. [40] |

| 734, 763 | Turkey | c.64+2T>A | Splice disruption | Intron 6 | Congenital/Prelingual | Profound | Sirmaci et al. [43] |

| PKSR9, PKSN9, PKSN24, PKDF7, PKDF75 | Pakistan | c.100C>T | p.R34X | Exon 7 | Prelingual | Severe to profound | Kurima et al. [23] |

| PKDF69, PKDF178, PKDF243, PKDF319, PKDF401 | Pakistan | c.100C>T | p.R34X | Exon 7 | Prelingual | Severe to profound | Kitajiri et al. [40] |

| Family A, B, C | Tunisia | c.100C>T | p.R34X | Exon 7 | Congenital | Profound | Tlili et al. [42] |

| 935 | Iran | c.100C>T | p.R34X | Exon 7 | Congenital | Severe to profound | Hilgert et al. [41] |

| Nas | Lebanon/Jordan | c.100C>T | p.R34X | Exon 7 | Congenital | Severe to profound | Hilgert et al. [41] |

| 685 | Turkey | c.100C>T | p.R34X | Exon 7 | Congenital/Prelingual | Severe to profound | Sirmaci et al. [43] |

| L787 | Iran | c.150delT | p.N50KfsX26 | Exon 7 | Congenital | Profound | Yang et al. [35] |

| M36 | Iran | c.236+1G>A | Splice disruption | Intron 7 | Congenital | Severe to profound | Hilgert et al. [41] |

| IN-DKB6 | North America (Indian) | c.295delA | p.K99KfsX4 | Exon 8 | Prelingual | Severe to profound | Kurima et al. [23] |

| PKSR25 | Pakistan | c.536-8T>A | Splice disruption | Intron 10 | Prelingual | Severe to profound | Kurima et al. [23] |

| 4090 | Pakistan | c.536-8T>A | Splice disruption | Intron 10 | Prelingual | Severe to profound | Santos et al. [37] |

| DF139 | Turkey | c.767delT | p.F255FfsX14 | Exon 13 | Congenital | Severe to profound | Hilgert et al. [41] |

| TR56 | Turkey | c.821C>T | p.P274L | Exon 13 | Prelingual | Profound | Kalay et al. [38] |

| 4049 | Pakistan | c.830A>G | p.Y277C | Exon 13 | Prelingual | Severe to profound | Santos et al. [37] |

| PKSR1a | Pakistan | c.884+1G>A | Splice disruption | Intron 13 | Prelingual | Severe to profound | Kurima et al. [23] |

| TR56 | Turkey | c.1083_1087delCAGAT | p.R362PfsX6 | Exon 15 | Prelingual | Profound | Kalay et al. [38] |

| 4119, 4160 | Pakistan | c.1114G>A | p.V372M | Exon 15 | Prelingual | Severe to profound | Santos et al. [37] |

| Family D | Tunisia | c.1165C>T | p.R389X | Exon 15 | Congenital | Profound | Tlili et al. [42] |

| Fay | Lebanon/Jordan | c.1165C>T | p.R389X | Exon 15 | Congenital | Severe to profound | Hilgert et al. [41] |

| DF135 | Turkey | c.1166G>A | p.R389Q | Exon 15 | Congenital | Severe to profound | Hilgert et al. [41] |

| D555 | China | c.1209G>C | p.W403C | Exon 15 | Prelingual | Severe to profound | Yang et al. [47] |

| 232 | Turkey | c.1330G>A | p.G444R | Exon 16 | Congenital/Prelingual | Profound | Sirmaci et al. [43] |

| 647 | Turkey | c.1333C>T | p.R445C | Exon 16 | Congenital/Prelingual | Severe to profound | Sirmaci et al. [43] |

| TR56 | Turkey | c.1334G>A | p.R445H | Exon 16 | Prelingual | Profound | Kalay et al. [38] |

| PKSR20a | Pakistan | c.1534C>T | p.R512X | Exon 17 | Prelingual | Severe to profound | Kurima et al. [23] |

| PKDF431 | Pakistan | c.1541C>T | p.P514L | Exon 17 | Prelingual | Severe to profound | Kitajiri et al. [40] |

| PKDF329, PKDF511 | Pakistan | c.1543T>C | p.C515R | Exon 17 | Prelingual | Severe to profound | Kitajiri et al. [40] |

| W06-792 | Netherlands | c.1763+3A>G | p.W588WfsX81 | Intron 19 | Postlingual | Profound 1st decade: high frequencies 2nd–3rd decade: all frequencies |

de Heer et al. [44] |

| Family E | Tunisia | c.1764G>A | p.W588X | Exon 20 | Congenital | Profound | Tlili et al. [42] |

| GRE | Greece | c.1810C>T | p.R604X | Exon 20 | Congenital | Severe to profound | Hilgert et al. [41] |

| IN-M17 | North America (Indian) | c.1960A>G | p.M654V | Exon 20 | Prelingual | Severe to profound | Kurima et al. [23] |

| 4070, 4138 | Pakistan | c.2004T>G | p.S668R | Exon 21 | Prelingual | Severe to profound | Santos et al. [37] |

| PKDF419 | Pakistan | c.2004T>G | p.S668R | Exon 21 | Prelingual | Severe to profound | Kitajiri et al. [40] |

| 675 | Turkey | c.2030T>C | p.I677T | Exon 21 | Congenital/Prelingual | Profound | Sirmaci et al. [43] |

| 4008, 4033 | Pakistan | c.2035G>A | p.E679K | Exon 21 | Prelingual | Severe to profound | Santos et al. [37] |

| 551 | Turkey | c.1696_2283del e | Genomic deletion | Congenital/Prelingual | Profound | Sirmaci et al. [43] | |

| Compound heterozygous state c | |||||||

| D419 | China | c.150delT c.1107C>A |

p.N50KfsX25 p.N369K |

Exon 7 Exon 9 |

Prelingual | Severe to profound | Yang et al. [47] |

| D472 | China | c.236+1G>C c.1334G>A |

Splice disruption p.R445H |

Intron 7 Exon 16 |

Prelingual | Severe to profound | Yang et al. [47] |

| 21 | Europe | c.458G>A c.1763+3A>G |

p.W153X Splice disruption |

Exon 10 Intron 19 |

Prelingual | Moderate to profound | Schrauwen et al. [46] |

| 1953 | China | c.589G>A c.1171C>T |

p.G197R p.Q391X |

Exon 11 Exon 15 |

Prelingual | Severe to profound | Gao et al. [48] |

| Not described | Sudan | c.1165C>T c.1763+5G>A |

p.R389X Splice disruption |

Exon 13 Intron 19 |

Congenital | Profound | Meyer et al. [39] |

| D28C | Morocco (Jewish) | c.1810C>T c.1939T>C |

p.R604X p.S647P |

Exon 20 Exon 20 |

Not available | Profound | Brownstein et al. [45] |

Abbreviation: HL, hearing loss.

The numbering is based on cDNA sequence (GenBank accession number: NM_138691.2).

Homozygous state indicates that the patients have same mutations on both alleles.

Compound heterozygous state indicates that the patient have different mutations on each allele.

The mutation is a 27-kb deletion encompassing exons 4–5 and adjacent introns.

The mutation is a 431-kb deletion encompassing exons 19–24 with intron 18 and downstream sequences of 3′ untranslated region.

Mutations in TMC1 are a common cause of autosomal recessive nonsyndromic deafness (Table 3). Mutation analysis of TMC1 among Pakistani and North American families segregating autosomal recessive nonsyndromic HL identified TMC1 mutations in 11 (4.8%) of 230 families [23]. The Pakistani portion of this mixed cohort was later increased to 557 families and mutations in TMC1 were identified in 19 (3.4%) of 557 families [40]. Another study in a different Pakistani population identified TMC1 mutations in eight (4.4%) in 180 families [37]. Mutations in TMC1 were also identified in other populations of hearing loss patients of different ethnicity at a similar prevalence: 4.3% (4/93) in Turkey [38]; 5.9% (5/85) in Tunisia [42]; 8.1% (7/86) in another study among Turkish population [43]; and 4.2% (1/24) in Europe [46]. Recently, high-throughput sequencing of 79 known deafness-causing genes in 190 Chinese patients revealed TMC1 mutations in three (1.6%) of 190 [47]. Since this latter study included patients with prelingual or early-onset severe to profound deafness, regardless of a family history of hearing loss, the prevalence may be low due to inclusion of non-genetic cases. These findings indicate that recessive mutations of TMC1 mutations are distributed worldwide and are a comparatively common cause of nonsyndromic HL.

Table 3.

Prevalence of DFNB7/B11 among deaf populations

| Reference | Study family/patient criteria | Origin | Number of families/patients with TMC1 mutations (%) | Method to detect TMC1 mutations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kurima et al. [23] | Consanguineous families segregating autosomal recessive, nonsyndromic, prelingual, severe to profound SNHL | Pakistan and North America (Indian) | 11/230 families (4.8%) | Linkage analysis and dideoxy sequencing b |

| Kitajiri et al. [40] | Consanguineous families segregating autosomal recessive, prelingual, severe to profound SNHL | Pakistan | 19/557 families (3.4%) | Linkage analysis and dideoxy sequencing b |

| Santos et al. [37] | Families segregating autosomal recessive, nonsyndromic, prelingual, severe to profound SNHL Each family includes at least two affected individuals |

Pakistan | 8/180 families (4.4%) | Linkage analysis and dideoxy sequencing b |

| Kalay et al. [38] | Consanguineous families segregating autosomal recessive, nonsyndromic, prelingual, profound SNHL Families with GJB2 mutations were excluded |

Turkey | 4/93 families (4.3%) | Linkage analysis and dideoxy sequencing b |

| Tlili et al. [42] | Consanguineous families segregating autosomal recessive, nonsyndromic, congenital, moderate to profound SNHL Families with GJB2 mutations were excluded |

Tunisia | 5/85 families (5.9%) | Linkage analysis and dideoxy sequencing b |

| Sirmaci et al. [43] | Consanguineous families segregating autosomal recessive, nonsyndromic, congenital or prelingual, severe to profound SNHL Families with GJB2 mutations were excluded |

Turkey | 7/86 families (8.1%) | Linkage analysis and dideoxy sequencing b |

| Schrauwen et al. [46] | Patients with autosomal recessive, nonsyndromic, moderate to profound SNHL Patients with GJB2 mutations were excluded |

Europe | 1/24 patients (4.2%) | High-throughput sequencing of 34 deafness genes |

| Yang et al. [47] | Patients with nonsyndromic, prelingual or early onset, severe to profound SNHL a | China | 3/190 patients (1.6%) | High-throughput sequencing of 79 deafness genes |

Abbreviation: SNHL, sensorineural hearing loss.

This study included 137 simplex and 53 multiplex probands. Of the multiplex probands, seven were from families with dominant segregation; 42 from families with probable recessive inheritance and four from families with maternal inheritance.

Linkage analysis to DFNB7/B11 interval was performed among family members and dideoxy sequencing of coding exons and flanking introns of TMC1 was performed among the linked families.

Generally, DFNB7/B11 patients have congenital or prelingual non-progressive severe to profound hearing loss (Table 2) [23,35,37–43,45–48]. Interestingly, in one family (W06-792) segregating DFNB7/B11, HL was noticed in the first to second decade of life, starting at high frequencies and rapidly progressing to severe to profound levels by the third or fourth decade (Fig. 1c) [44]. Genome-wide linkage analysis and dideoxy sequencing of TMC1 identified c.1763+3A>G in the family, leading to a frameshift and a premature stop codon due to the utilization of a cryptic splice donor site 47 bp downstream in intron 19. The delay in the onset of HL may result from residual wild-type TMC1 transcripts escaping the aberrant splicing or from residual function of mutant truncated proteins.

Although vestibular function was formally examined in only some affected subjects, none reported vestibular symptoms or a developmental delay in gross motor skills [23,37,39,41,43,48]. These findings collectively suggest that TMC1 mutations do not affect vestibular function.

Mouse models for DFNA36 and DFNB7/B11 deafness

The laboratory mouse is an invaluable model organism for investigating the genetic basis of human disease because of its short life span, ease of experimental manipulation and limited genetic heterogeneity. Mice have additional advantages for use in the analysis of HL. There are strong structural similarities between the human and the mouse auditory system [49]. Furthermore, mouse models allow histopathological and ultrastructural studies and electrophysiological measurements to investigate the underlying pathogenesis of HL.

The mouse genes involved in hearing exhibit strong sequence similarities and similar functions with their human counterparts [50]. Most information about protein function in the auditory system originates from the study of mouse mutants carrying alterations in the genes corresponding to those in human HL. These mouse mutants are derived from spontaneous mutagenic events, chemical mutagens such as N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU), as well as gene-targeting techniques.

The mouse ortholog Tmc1 spans approximately 170 kb on mouse chromosome 19. It consists of 21 exons with a coding region of 2274 nucleotides [23]. The amino acid sequence of mouse TMC1 protein has 95% identity and 96% similarity with that of human TMC1 [26]. Tmc1 mRNA is expressed in mouse cochlear and vestibular hair cells from the late embryonic stages of development [23,24]. Mouse Tmc1 also has dominant and recessive mutant alleles that cause hearing loss in mutant mouse strains, including Beethoven (Bth) [51], deafness (dn) [23,52], baringo, nice, stitch [53] and a targeted deletion of Tmc1 (Tmc1Δ) mice [24] (Table 4).

Table 4.

Tmc1 mutant mouse strains

| Mouse mutant | Mutagenesis method | Nucleotide mutation a | Predicted effect | Exon number | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beethoven (Bth) | ENU | c.1235T>A | p.M412K | Exon 13 | Vreugde et al. [51] |

| deafness (dn) | Spontaneous | c.1387_1557del c | p.(I463_Q519del) | Kurima et al. [23] Deol et al. [52] |

|

| baringo | ENU | c.545A>G | p.Y182C | Exon 8 | Manji et al. [53] |

| nice | ENU | c.1345T>C | p.Y449H | Exon 13 | Manji et al. [53] |

| stitch | ENU | c.1661G>T | p.W554L | Exon 15 | Manji et al. [53] |

| Tmc1Δ b | Targeted deletion | Kawashima et al. [24] |

Abbreviation: ENU, N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea.

The numbering is based on cDNA sequence (GenBank accession number: NM_028953.2).

Exons 8–9 and adjacent introns were replaced with a gene trap construct fused to a LacZ reporter gene.

The mutation is a 1656-bp deletion encompassing 171-bp exon 14 with adjacent introns.

Phenotypic, ultrastructural and electrophysiological characteristics of Beethoven (Bth) mice

The Bth mutation of Tmc1, p.M412K, arose in a large-scale ENU mutagenesis program [51]. Heterozygous mice (Tmc1Bth/+) show progressive sensorineural HL analogous to that of human DFNA36 [51]. The measurement of compound action potentials (CAPs) showed a small but significant elevation of thresholds for stimulus test frequencies ≥18 kHz at postnatal day 15 (P15), and a large increase in CAP thresholds for frequencies ≥12 kHz at P30 [54]. Scanning electron microscopy of Tmc1Bth/+ organs of Corti revealed progressive hair cell degeneration from P20 onward. At P30, Tmc1Bth/+ mice showed hair cell damage and a significant reduction of number of hair cells in the basal and middle turns of the cochlea. There was an unusual pattern with inner hair cells (IHCs) lost at an earlier age than outer hair cells (OHCs), but no significant hair cell loss in the apical region [51,55]. There was a correlation between hair cell loss and elevated CAP thresholds in Tmc1Bth/+ mice. In contrast, homozygous mice (Tmc1Bth/Bth) showed profound deafness at all time points at which hearing can be detected in wild-type mice [54]. CAP responses could not be detected in P15 Tmc1Bth/Bth ears exposed to maximum stimulus intensities. Scanning electron microscopy showed hair cell damage and a significant reduction in the number of hair cells in the basal and middle turns even at P15, but no significant hair cell loss in the apical region. Endocochlear potentials (EPs) were present and normal in Tmc1Bth/+ and Tmc1Bth/Bth mice. Furthermore, MET currents could be recorded from OHCs at P6 to P7 under whole-cell voltage clamp [54].

Phenotypic, ultrastructural and electrophysiological characteristics of deafness (dn), baringo, nice, stitch and Tmc1Δ mice

Homozygous dn, baringo, nice, stitch and Tmc1Δ mice show severe to profound deafness at P30, whereas heterozygotes display no differences in hearing thresholds from those of wild-type mice [24,52,53]. These findings reveal that these mouse strains are models of human recessive deafness DFNB7/B11. The model mice were generated in different ways: dn, a 1,656-bp deletion encompassing the 171-bp exon 14 and adjacent introns, is a spontaneous mutation [23,52]; baringo (p.Y182C), nice (p.Y449H) and stitch (p.W554L) arose in a large-scale ENU mutagenesis program [53]; and Tmc1Δ was generated using homologous recombination to replace the region encompassing exons 8–9 and adjacent introns with a gene trap construct fused to a LacZ reporter gene [24].

Of these DFNB7/B11 models, dn mice have been the most extensively examined. This strain was first described by Doel and Kocher in 1958 as an autosomal recessive mutant arising from the curly-tail stock [52]. Tmc1dn/dn mice lacked any cochlear responses (CAPs, summating potentials or cochlear microphonics) to sound stimuli between the ages of P12 and P20 [54,56]. Scanning electron microscopy revealed that Tmc1dn/dn mice had normal hair bundles at P14 but showed significant hair cell damage and loss in middle and basal cochlear turns at P30, where IHCs and OHCs appeared equally affected. In the apical turn, many hair cells retained a normal, or near-normal, bundle appearance at P30 [54]. The EPs were present and normal in Tmc1dn/dn mice [56]. Furthermore, MET currents could be recorded from Tmc1dn/dn OHCs at P6-7 under whole-cell voltage clamp [54]. Tmc1dn/dn mice do not show circling behavior or head tilting/tossing that suggest the existence of congenital severe vestibular dysfunction [52].

Homozygous baringo, nice and stitch mice show auditory and morphological characteristics similar to those of Tmc1dn/dn mice with some variations that may be caused by differences in the mutations [53]. Homozygous Tmc1Δ (Tmc1Δ/Δ) mice showed the same auditory and morphological characteristics as Tmc1dn/dn mutants [24].

The association of Tmc1 and Tmc2 with mechanoelectrical transduction (MET) in mouse hair cells

The absence of CAPs in Tmc1Bth/Bth and Tmc1dn/dn mice at P15 in spite of their normal hair bundle appearance at the apical cochlear turn indicated that HL might not be an indirect consequence of a hair cell structural defect but a functional deficit. Furthermore, the absence of cochlear microphonics in Tmc1dn/dn mice, in spite of the presence of an intact EP, suggested that the underlying mutation might affect the MET channels [54,56,57]. However, this hypothesis seemed unlikely when MET currents were recorded from P6-7 OHCs from Tmc1Bth/Bth and Tmc1dn/dn mice [54].

Kawashima et al. [24] revealed a contribution of Tmc1 and the closely related Tmc2 gene to MET using mice segregating the targeted deletion alleles Tmc1Δ and Tmc2Δ. Tmc2, the mouse ortholog of human TMC2, is expressed in mouse cochlear and vestibular hair cells, but neither Tmc2 nor TMC2 has been implicated in inner ear dysfunction. Its temporal expression pattern in hair cells was different from that of Tmc1. Tmc2 expression was transient in early postnatal cochlear hair cells but persisted in vestibular hair cells, whereas Tmc1 expression was persistent in mature cochlear and vestibular hair cells. While Tmc1Δ/Δ mice were deaf and Tmc2Δ/Δ mice were phenotypically normal, double homozygous (Tmc1Δ/Δ;Tmc2Δ/Δ) mice showed deafness and complete loss of peripheral vestibular function. These observations suggest that persistent Tmc2 expression in vestibular hair cells may preserve vestibular function in mature Tmc1Δ/Δ mice. Scanning electron microscopic analysis of Tmc1Δ/Δ;Tmc2Δ/Δ inner ear tissue demonstrated that cochlear and vestibular hair cells had intact hair bundles, tip links and tip-link tension at P3 and had normal structure during the early postnatal period. These morphologically normal cochlear and vestibular hair cells were used to evaluate mechanosensory function. While MET currents were detected in vestibular and cochlear hair cells from early postnatal Tmc1Δ/Δ or Tmc2Δ/Δ mice, MET currents were completely absent in Tmc1Δ/Δ;Tmc2Δ/Δ hair cells. Furthermore, MET currents were rescued by the expression of exogeneous Tmc1 or Tmc2 in cultured Tmc1Δ/Δ;Tmc2Δ/Δ hair cells. These findings indicate that Tmc1 and Tmc2 are necessary for hair cell MET. They also suggest that the MET currents inearly postnatal Tmc1Δ/Δ cochlear hair cells are mediated by Tmc2.

The spatiotemporal expression patterns of Tmc1 and Tmc2 mRNA were examined by quantitative RT-PCR and in situ hybridization. In the vestibular organs, a Tmc2 expression rises just before the onset of MET around E16-17, and the rise of Tmc1 expression lagged MET acquisition by several days [24]. In the cochlea, the rise in Tmc2 expression just preceded the spatiotemporal onset of MET in OHCs in the base at P0 and the apex at P2. The rise in Tmc1 expression lagged MET acquisition by 2–3 days in all regions of the cochlear. Moreover, Tmc2 expression declined from the base to the apex during this developmental period, revealing a switch from Tmc2 to Tmc1 expression [24]. Importantly, this developmental decrease of Tmc2 is consistent with the decrease of calcium permeability (PCa) in OHC MET channels from the base to the apex [58]. In wild-type mice, the PCa of OHCs decreases from the cochlear base to the apex before P6. In Tmc1dn/dn mice, PCa in basal OHCs was larger than that in wild-type mice, whereas in Tmc2 mutant mice (Tmc2tm1Lex/tm1Lex), PCa in apical and basal OHCs was decreased compared with that in wild-type OHCs. On the basis of these results, it was postulated that differences in PCa reflected different expression of Tmc1 and Tmc2, with the latter conferring higher PCa [24,58]. These results further support the association of Tmc1 and Tmc2 with MET.

Function of Tmc1 and Tmc2 in mouse hair cells

Several findings revealed that Tmc1 and Tmc2 are required for mouse hair cell MET [24,58], but the precise molecular function of their protein products is unknown. Considering the data described above, there are at least four hypotheses about their function: first, TMC1 and TMC2 proteins may be pore-forming subunits of the MET channel; second, they may be accessory subunits physically associated with the pore-forming subunits of the MET channel; third, they may be components of the MET complex, but not directly contacting the MET channel; finally, they may be required for assembly, trafficking, development, or function of MET channel or complex without being stably physically associated with them. These four hypotheses are not mutually exclusive: more than one may be true.

Recently, Pan et al. [25] measured whole-cell and single-channel currents from mouse cochlear hair cells of Tmc1+/Δ;Tmc2Δ/Δ, Tmc1Δ/Δ;Tmc2+/Δ or Tmc1Bth/Δ;Tmc2Δ/Δ mice: these mutant hair cells expressed only wild-type TMC1, only wild-type TMC2, or only mutant TMC1 (p.M412K) molecules. This allowed direct comparison of MET channel properties associated with the presence of only TMC1, TMC2 or mutant TMC1 by measuring MET currents of hair cells from each compound mutant mouse. IHCs that expressed wild-type Tmc2 but not Tmc1 had high PCa, and large single-channel currents in comparison to those of hair cells expressing only Tmc1. In contrast, hair cells that expressed mutant Tmc1 had reduced PCa and reduced single-channel currents in comparison to those of cells that expressed wild-type Tmc1. These findings demonstrated that a missense amino acid substitution, p.M412K, in TMC1 alters the ion permeation properties of hair cell MET channels, consistent with the hypothesis that TMC1 and TMC2 are components of the hair cell MET complex, if not the channel itself.

An alternative technique was used by Kim et al. [59], who recently reported the existence of a mechanically elicited current in the OHCs from double homozygous mutant mice (Tmc1dn/dn;Tmc2tm1Lex/tm1Lex) using an oscillating fluid jet. After disruption of tip links with a calcium chelator, they observed currents in OHCs of neonatal wild-type and the double homozygous mutant mice. However, the characteristics of the stimulus were anomalous in that the currents were activated by displacements of the hair bundle away from its tallest row of stereocilia. They were unable to elicit currents when the bundle was displaced toward the tallest row of stereocilia, as occurs in wild-type hair cells whose bundles have not been disrupted with calcium chelation. These “reverse” MET currents had similar characteristics to conventional MET currents in wild-type hair bundles: the novel currents were blocked by styryl dye FM1-43, dihydrostreptomycin, and extracellular calcium at concentrations similar to those that block wild-type hair cell MET channels. In contrast, the PCa of the reverse transduction current in the double homozygous mutant hair cells was lower than that of conventional wild-type MET. On the basis of these findings, Kim et al. concluded that, in the absence of TMC1 and TMC2, the MET channel is not associated with the tip link and cannot be activated by tip-link tension, but can be activated by reverse displacement. This led them to conclude that neither TMC1 nor TMC2 are pore-forming components of MET channel. They hypothesized that TMC1 and TMC2 are required for targeting the MET channel to the tips of the stereocilia where they can interact with other constituents of the transduction complex, including the tip link.

There are several caveats to these conclusions. First, the targeted deletion alleles of Tmc1 and Tmc2 used by Kim et al. may encode functional or partially functional TMC proteins. Even if the mutant TMC1 or TMC2 proteins cannot traffic to tips of stereocilia to contribute to conventional MET, they may nevertheless contribute to the non-canonical reverse transduction that may be occurring at other locations at the apical region of the hair cell. Second, the non-cannonical MET currents could be mediated by another protein(s), including another TMC protein(s), because the inhibitors used by Kim et al. are not specific for the MET channel of hair cell stereocilia. The precise role of TMC1 and TMC2 in hair cell MET remains an open question at this time.

Several criteria have to be met for a protein to be considered the bona fide hair cell MET channel [60,61]. First, the channel must be expressed in the appropriate temporal and spatial domains to allow for hair cell MET function. Second, the channel must be required for the hair cell MET response to mechanical stimuli. Third, missense substitutions of the pore region of the protein, which do not affect its assembly or folding, should alter the core biophysical properties of the channel pore. Fourth, the MET channel activity should be reconstituted by expression of the candidate protein(s) in vitro or in a heterologous expression system.

For the first criteria, the rise in Tmc2 mRNA expression immediately preceded the onset of MET, and exogenous fluorophore-tagged TMC1 and TMC2 proteins are localized to the tips of the stereocilia [24]. For the second criteria, the conclusions are disparate: Kawashima et al. [24] and Pan et al. [25] showed that hair cells in Tmc1Δ/Δ;Tmc2Δ/Δ mutant eliminates conventional MET currents and exogenous TMC1 and TMC2 can restore MET currents in cultured Tmc1Δ/Δ;Tmc2Δ/Δ hair cells. While Kim et al. [59] demonstrated non-canonical MET currents in the double homozygous mutant hair cells, the relevance of those currents is unknown in the absence of information about the expression and localization of TMC proteins encoded by the Tmc mutant alleles they studied. For the third criteria, Pan et al. [25] showed that a missense mutation in TMC1 altered the permeation properties of the hair cell MET channel. This is consistent with TMC1 being a component of the channel, but it is inconclusive evidence. For the fourth criteria, reconstitution of the MET channel in a heterologous system has not yet been successful. When TMC1, TMC2, or both are expressed in heterologous systems, they fail to localize to the plasma membrane where they could be tested by electrophysiologic methods for channel activity. Reconstitution of MET may require yet to be identified beta subunits, if any, and other protein or lipid partners necessary for stretch-activated channel function in hair cells. A recent report concluded that C. elegans tmc-1 encodes a sodium-sensitive ion channel, but this study lacked a mutated control and did not, in our opinion, adequately demonstrate plasma membrane localization of the protein. Moreover, this observation has not been replicated for vertebrate TMC1 [62]. Expression of functional TMC1 and TMC2 in vitro or in a heterologous system will be helpful to test the hypothesis that they are components of the hair cell MET channel. Given the long journey to identify the hair cell MET channel, we do not expect this to be easy.

Conclusion

A large number of TMC1 mutations have been identified by linkage analysis and DNA sequencing of DFNA36 and DFNB7/B11 patients worldwide, indicating that TMC1 mutations are comparatively common causes of genetic deafness. Typically, DFNA36 subjects show post-lingual, progressive sensorineural HL, resulting in severe to profound deafness. In contrast, DFNB7/B11 subjects show congenital or prelingual severe to profound sensorineural HL. While the precise function of Tmc1 remains unknown, recent studies of Tmc1 and Tmc2 mutant mouse models revealed that they are required for MET in cochlear and vestibular hair cells. There is a possibility that TMC1 and TMC2 are actual components of the elusive hair cell MET channel, whose molecular identity remains unknown.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dennis T. Drayna, Thomas B. Friedman and Jeffrey R. Holt for critical review of this manuscript. Work in the authors’ laboratories was supported by NIH intramural research fund Z01-DC-000060-13 (A.J.G.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Kiyoto Kurima and Andrew J. Griffith hold the following U.S. patents: 7,166,433 (Transductin-2 and Applications to Hereditary Deafness), 7,192,705 (Transductin-1 and Applications to Hereditary Deafness), and 7,659,115 (Nucleic Acid Encoding Human Transductin-1 Polypeptide).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Estivill X, Fortina P, Surrey S, Rabionet R, Melchionda S, D’Agruma L, et al. Connexin-26 mutations in sporadic and inherited sensorineural deafness. Lancet. 1998;351:394–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11124-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nadol JB., Jr Hearing loss. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1092–1102. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199310073291507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morton CC, Nance WE. Newborn hearing screening--a silent revolution. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2151–64. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith RJ, Bale JF, Jr, White KR. Sensorineural hearing loss in children. Lancet. 2005;365:879–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marazita ML, Ploughman LM, Rawlings B, Remington E, Arnos KS, Nance WE. Genetic epidemiological studies of early-onset deafness in the U.S. school-age population. Am J Med Genet. 1993;46:486–91. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320460504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nance WE, Lim BG, Dodson KM. Importance of congenital cytomegalovirus infections as a cause for pre-lingual hearing loss. J Clin Virol. 2006;35:221–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Resendes BL, Williamson RE, Morton CC. At the speed of sound: gene discovery in the auditory system. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:923–35. doi: 10.1086/324122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nance WE. Genetic counseling of hereditary deafness; an unusual need. In: Bass FH, editor. Childhood Deafness: Causation, Assessment and Management. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1977. pp. 211–6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rose SP, Conneally PM, Nance WE. Genetic analysis of childhood deafness. In: Bass FH, editor. Childhood Deafness: Causation, Assessment and Management. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1977. pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dror AA, Avraham KB. Hearing impairment: a panoply of genes and functions. Neuron. 2010;68:293–308. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richardson GP, de Monvel JB, Petit C. How the genetics of deafness illuminates auditory physiology. Annu Rev Physiol. 2011;73:311–34. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Amraoui A, Petit C. Usher I syndrome: unravelling the mechanisms that underlie the cohesion of the growing hair bundle in inner ear sensory cells. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4593–603. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frolenkov GI, Belyantseva IA, Friedman TB, Griffith AJ. Genetic insights into the morphogenesis of inner ear hair cells. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:489–98. doi: 10.1038/nrg1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kazmierczak P, Sakaguchi H, Tokita J, Wilson-Kubalek EM, Milligan RA, Müller U, et al. Cadherin 23 and protocadherin 15 interact to form tip-link filaments in sensory hair cells. Nature. 2007;449:87–91. doi: 10.1038/nature06091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pickles JO, Comis SD, Osborne MP. Cross-links between stereocilia in the guinea pig organ of Corti, and their possible relation to sensory transduction. Hear Res. 1984;15:103–12. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(84)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Indzhykulian AA, Stepanyan R, Nelina A, Spinelli KJ, Ahmed ZM, Belyantseva IA, et al. Molecular remodeling of tip links underlies mechanosensory regeneration in auditory hair cells. PLoS Biol. 2013;11:e1001583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beurg M, Fettiplace R, Nam JH, Ricci AJ. Localization of inner hair cell mechanotransducer channels using high-speed calcium imaging. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:553–8. doi: 10.1038/nn.2295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Denk W, Holt JR, Shepherd GM, Corey DP. Calcium imaging of single stereocilia in hair cells: localization of transduction channels at both ends of tip links. Neuron. 1995;15:1311–21. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hudspeth AJ. Extracellular current flow and the site of transduction by vertebrate hair cells. J Neurosci. 1982;2:1–10. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-01-00001.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaramillo F, Hudspeth AJ. Localization of the hair cell’s transduction channels at the hair bundle’s top by iontophoretic application of a channel blocker. Neuron. 1991;7:409–20. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90293-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lumpkin EA, Hudspeth AJ. Detection of Ca2+ entry through mechanosensitive channels localizes the site of mechanoelectrical transduction in hair cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:10297–301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corey DP. What is the hair cell transduction channel? J Physiol. 2006;576:23–8. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.116582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurima K, Peters LM, Yang Y, Riazuddin S, Ahmed ZM, Naz S, et al. Dominant and recessive deafness caused by mutations of a novel gene, TMC1, required for cochlear hair-cell function. Nat Genet. 2002;30:277–84. doi: 10.1038/ng842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawashima Y, Géléoc GS, Kurima K, Labay V, Lelli A, Asai Y, et al. Mechanotransduction in mouse inner ear hair cells requires transmembrane channel-like genes. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4796–809. doi: 10.1172/JCI60405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan B, Géléoc GS, Asai Y, Horwitz GC, Kurima K, Ishikawa K, et al. TMC1 and TMC2 are components of the mechanotransduction channel in hair cells of the mammalian inner ear. Neuron. 2013;79:504–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurima K, Yang Y, Sorber K, Griffith AJ. Characterization of the transmembrane channel-like (TMC) gene family: functional clues from hearing loss and epidermodysplasia verruciformis. Genomics. 2003;82:300–8. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(03)00154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Labay V, Weichert RM, Makishima T, Griffith AJ. Topology of transmembrane channel-like gene 1 protein. Biochemistry. 2010;49:8592–8. doi: 10.1021/bi1004377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramoz N, Rueda LA, Bouadjar B, Montoya LS, Orth G, Favre M. Mutations in two adjacent novel genes are associated with epidermodysplasia verruciformis. Nat Genet. 2002;32:579–81. doi: 10.1038/ng1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orth G. Genetics of epidermodysplasia verruciformis: Insights into host defense against papillomaviruses. Semin Immunol. 2006;18:362–74. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patel T, Morrison LK, Rady P, Tyring S. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis and susceptibility to HPV. Dis Markers. 2010;29:199–206. doi: 10.3233/DMA-2010-0733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lazarczyk M, Dalard C, Hayder M, Dupre L, Pignolet B, Majewski S, et al. EVER proteins, key elements of the natural anti-human papillomavirus barrier, are regulated upon T-cell activation. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lazarczyk M, Pons C, Mendoza JA, Cassonnet P, Jacob Y, Favre M. Regulation of cellular zinc balance as a potential mechanism of EVER-mediated protection against pathogenesis by cutaneous oncogenic human papillomaviruses. J Exp Med. 2008;205:35–42. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kitajiri S, Makishima T, Friedman TB, Griffith AJ. A novel mutation at the DFNA36 hearing loss locus reveals a critical function and potential genotype-phenotype correlation for amino acid-572 of TMC1. Clin Genet. 2007;71:148–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hilgert N, Monahan K, Kurima K, Li C, Friedman RA, Griffith AJ, et al. Amino acid 572 in TMC1: hot spot or critical functional residue for dominant mutations causing hearing impairment. J Hum Genet. 2009;54:188–90. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2009.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang T, Kahrizi K, Bazazzadeghan N, Meyer N, Najmabadi H, Smith RJ. A novel mutation adjacent to the Bth mouse mutation in the TMC1 gene makes this mouse an excellent model of human deafness at the DFNA36 locus. Clin Genet. 2010;77:395–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01338.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Makishima T, Kurima K, Brewer CC, Griffith AJ. Early onset and rapid progression of dominant nonsyndromic DFNA36 hearing loss. Otol Neurotol. 2004;25:714–9. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200409000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santos RL, Wajid M, Khan MN, McArthur N, Pham TL, Bhatti A, et al. Novel sequence variants in the TMC1 gene in Pakistani families with autosomal recessive hearing impairment. Hum Mutat. 2005;26:396. doi: 10.1002/humu.9374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kalay E, Karaguzel A, Caylan R, Heister A, Cremers FP, Cremers CW, et al. Four novel TMC1 (DFNB7/DFNB11) mutations in Turkish patients with congenital autosomal recessive nonsyndromic hearing loss. Hum Mutat. 2005;26:591. doi: 10.1002/humu.9384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meyer CG, Gasmelseed NM, Mergani A, Magzoub MM, Muntau B, Thye T, et al. Novel TMC1 structural and splice variants associated with congenital nonsyndromic deafness in a Sudanese pedigree. Hum Mutat. 2005;25:100. doi: 10.1002/humu.9302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kitajiri SI, McNamara R, Makishima T, Husnain T, Zafar AU, Kittles RA, et al. Identities, frequencies and origins of TMC1 mutations causing DFNB7/B11 deafness in Pakistan. Clin Genet. 2007;72:546–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hilgert N, Alasti F, Dieltjens N, Pawlik B, Wollnik B, Uyguner O, et al. Mutation analysis of TMC1 identifies four new mutations and suggests an additional deafness gene at loci DFNA36 and DFNB7/11. Clin Genet. 2008;74:223–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.01053.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tlili A, Rebeh IB, Aifa-Hmani M, Dhouib H, Moalla J, Tlili-Chouchène J, et al. TMC1 but not TMC2 is responsible for autosomal recessive nonsyndromic hearing impairment in Tunisian families. Audiol Neurootol. 2008;13:213–8. doi: 10.1159/000115430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sirmaci A, Duman D, Oztürkmen-Akay H, Erbek S, Incesulu A, Oztürk-Hi mi B, et al. Mutations in TMC1 contribute significantly to nonsyndromic autosomal recessive sensorineural hearing loss: a report of five novel mutations. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73:699–705. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Heer AM, Collin RW, Huygen PL, Schraders M, Oostrik J, Rouwette M, et al. Progressive sensorineural hearing loss and normal vestibular function in a Dutch DFNB7/11 family with a novel mutation in TMC1. Audiol Neurootol. 2011;16:93–105. doi: 10.1159/000313282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brownstein Z, Friedman LM, Shahin H, Oron-Karni V, Kol N, Abu Rayyan A, et al. Targeted genomic capture and massively parallel sequencing to identify genes for hereditary hearing loss in Middle Eastern families. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R89. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-9-r89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schrauwen I, Sommen M, Corneveaux JJ, Reiman RA, Hackett NJ, Claes C, et al. A sensitive and specific diagnostic test for hearing loss using a microdroplet PCR-based approach and next generation sequencing. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A:145–52. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang T, Wei X, Chai Y, Li L, Wu H. Genetic etiology study of the non-syndromic deafness in Chinese Hans by targeted next-generation sequencing. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:85. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gao X, Su Y, Guan LP, Yuan YY, Huang SS, Lu Y, et al. Novel compound heterozygous TMC1 mutations associated with autosomal recessive hearing loss in a Chinese family. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63026. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anagnostopoulos AV. A compendium of mouse knockouts with inner ear defects. Trends Genet. 2002;18:499. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)02753-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pennacchio LA. Insights from human/mouse genome comparisons. Mamm Genome. 2003;14:429–36. doi: 10.1007/s00335-002-4001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vreugde S, Erven A, Kros CJ, Marcotti W, Fuchs H, Kurima K, et al. Beethoven, a mouse model for dominant, progressive hearing loss DFNA36. Nat Genet. 2002;30:257–8. doi: 10.1038/ng848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Deol MS, Kocher W. A new gene for deafness in the mouse. Heredity. 1958;12:463–6. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Manji SS, Miller KA, Williams LH, Dahl HH. Identification of three novel hearing loss mouse strains with mutations in the Tmc1 gene. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:1560–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marcotti W, Erven A, Johnson SL, Steel KP, Kros CJ. Tmc1 is necessary for normal functional maturation and survival of inner and outer hair cells in the mouse cochlea. J Physiol. 2006;574:677–98. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.095661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Noguchi Y, Kurima K, Makishima T, de Angelis MH, Fuchs H, Frolenkov G, et al. Multiple quantitative trait loci modify cochlear hair cell degeneration in the Beethoven (Tmc1Bth) mouse model of progressive hearing loss DFNA36. Genetics. 2006;173:2111–9. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.057372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Steel KP, Bock GR. The nature of inherited deafness in deafness mice. Nature. 1980;288:159–61. doi: 10.1038/288159a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bock GR, Steel KP. Inner ear pathology in the deafness mutant mouse. Acta Otolaryngol. 1983;96:39–47. doi: 10.3109/00016488309132873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim KX, Fettiplace R. Developmental changes in the cochlear hair cell mechanotransducer channel and their regulation by transmembrane channel-like proteins. J Gen Physiol. 2013;141:141–8. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201210913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim KX, Beurg M, Hackney CM, Furness DN, Mahendrasingam S, Fettiplace R. The role of transmembrane channel-like proteins in the operation of hair cell mechanotransducer channels. J Gen Physiol. 2013;142:493–505. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201311068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Christensen AP, Corey DP. TRP channels in mechanosensation: direct or indirect activation? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:510–21. doi: 10.1038/nrn2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arnadóttir J, Chalfie M. Eukaryotic mechanosensitive channels. Annu Rev Biophys. 2010;39:111–37. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chatzigeorgiou M, Bang S, Hwang SW, Schafer WR. tmc-1 encodes a sodium-sensitive channel required for salt chemosensation in C. elegans. Nature. 2013;494:95–9. doi: 10.1038/nature11845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]