Abstract

The demand for high-throughput single cell assays is gaining importance because of the heterogeneity of many cell suspensions, even after significant initial sorting. These suspensions may display cell-to-cell variability at the gene expression level that could impact single cell functional genomics, cancer, stem-cell research and drug screening. The on-chip monitoring of individual cells in an isolated environment would prevent cross-contamination, provide high recovery yield, and enable study of biological traits at a single cell level. These advantages of on-chip biological experiments is a significant improvement for myriad of cell analyses over conventional methods, which require bulk samples providing only averaged information on cell metabolism. We report on a device that integrates mobile magnetic trap array with microfluidic technology to provide, combined functionality of separation of immunomagnetically labeled cells or magnetic beads and their encapsulation with reagents into pico-liter droplets. This scheme of simultaneous reagent delivery and compartmentalization of the cells immediately after sorting, all performed seamlessly within the same chip, offers unique advantages such as the ability to capture cell traits as originated from its native environment, reduced chance of contamination, minimal use and freshness of the reagent solution that reacts only with separated objects, and tunable encapsulation characteristics independent of the input flow. In addition to the demonstrated preliminary cell viability assay, the device can potentially be integrated with other up- or downstream on-chip modules to become a powerful single-cell analysis tool.

Introduction

Technological developments over the past several decades have played a major role in driving basic biology research and advancements in biomedical sciences. While cell and molecular biology techniques have laid the foundation of present diagnostics and therapeutic systems, most of these methods rely on ensemble measurements obtained from heterogeneous cell populations [1]. However, it has been demonstrated in different systems that even within an isogenic cell population, stochastic gene expressions exist among cells [2–5]. Analyzing an ensemble of cells at an individual level with high spatiotemporal resolutions can thus lead to a better understanding of such cell-to-cell variations [6]. Two key processes required prior to performing single-cell analyses are (i) the sorting of cells into subpopulations and (ii) the compartmentalization of these cells of interest with dedicated reagents into individual isolated environments.

Different sorting techniques have been developed over the past decade [7–9]. For example, conventional flow cytometry [4,10] sorts cells based on their sizes and biological signatures. While it is a well-developed and commercially available technique, this approach requires expensive instrumentation. Electric-field-based techniques such as optical trap [11,12], dielectrophoresis [12–16] and electrokinesis [17] utilize the dielectric property or charge of the objects to be sorted. However, these schemes generally have strict requirements on the optical and ionic properties of the surrounding fluid, and challenges such as heating and electrolysis (bubbling) need to be addressed. In contrast, magnetic-field-based sorting, achieved by the intrinsic or extrinsic (through marker-specific magnetic bead labeling) magnetic moment of the cells [18], serves as an inexpensive technique without the same difficulties that plague its electric counterparts. Schemes such as external magnets [19–23], ferromagnetic channels [24], ferromagnetic strips [25–27] and periodic ferromagnetic patterns [28–30] have been shown to generate the magnetic field gradient required to manipulate magnetic objects to desired locations.

Compartmentalization of the sorted cells of interest into individual isolated environments is a crucial step towards single-cell analysis. Various schemes have been utilized for the purpose of compartmentalization. For example, array of wells on proprietary chips [4,31] and microfluidic chambers [32–34] act as containers for single cells while delivering reagents through pumps and valves. However, the nature of these rigid confining structures limits the ability to multiplex and could potentially be contaminated or worn off over multiple uses. In contrast, compartmentalization based on microfluidic droplet devices serves as an alternative technique [35–40] where the containers (droplets) are created anew during the encapsulation of single cells. The number of droplets generated by the device is practically unlimited, allowing easy multiplexing.

In order to compartmentalize the cell while it still maintains the property as derived from the native heterogeneous environment, it is advantageous to perform the compartmentalization immediately following sorting in the same setup. However, existing work on single-cell analysis generally require transfer between machines [4, 31] or containers [5] from one step to another or purification of the samples elsewhere prior to introducing them onto the compartmentalization platforms [32–34,37–40]. These steps could potentially lead to contamination during transfer, freezing, and lose the ability to capture original cell traits. While sorting after compartmentalization may serve as a way of combining the two functions, e.g. post-encapsulation processing of droplets through hydrodynamic sorting [41], detection-based electric sorting [37,38] and droplet splitting [37,38,42], compartmentalization of the cells after their sorting, on the other hand, has the distinct advantage of preventing contamination from unwanted chemicals or cell population in the compartments.

In this paper, we integrate for the first time, the magnetic sorting capability of previously developed mobile magnetic trap array [30] immediately before compartmentalization with droplet microfluidics on the same chip-based device. The well-defined pick-up and drop-off locations of the mobile trap array and its ability to actively manipulate cells against the flow are unique features enabling this device for the separation of magnetically labeled cells and their encapsulation into droplets with the reagents. Preliminary assay on the viability of encapsulated cells through fluorescence detection demonstrates the potential to further integrate the device with downstream on-chip analysis schemes. With the combined advantages of low cost, ability to multiplex and the biocompatible nature of magnetic forces, the separation-encapsulation device presented here could become a key component in future single-cell analysis platforms.

Experimental

Device fabrication

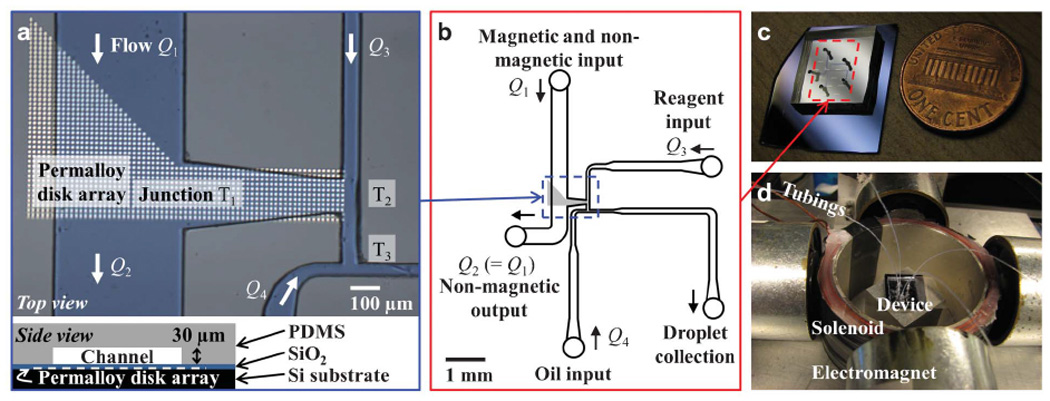

A mask design with transparent patterns of disk arrays and microchannels was produced on a chromium-on-quartz plate (Advance Reproductions Corporation). As shown in Fig. 1a, arrays of permalloy (Ni0.8Fe0.2) disks with 10 µm diameter, 15 µm centre-to-centre spacing and 84 nm height were imprinted onto a Si substrate by contact photolithography using the mask plate followed by physical vapor deposition and lift-off. A final deposition of 100 nm SiO2 on the entire surface served as a protective layer. The same photolithography technique was used to create microchannel molds (SU-8 2025, MicroChem) on the Si substrate. PDMS (polydimethylsiloxane) (Dow Corning Sylgard 184 Silicone Encapsulant, Ellsworth Adhesives) was mixed with curing agent at 10:1 ratio, poured onto the microchannel molds, cured at room temperature for 2 days, peeled from the mold, cut to desired size and punched with holes at the end of the channels for tubing connection. The resulting PDMS channel, with layout as illustrated in Fig. 1b, was permanently bonded to the disk array substrate to form the integrated device shown in Fig. 1c by the following procedure: The channel side of the PDMS as well as the SiO2 surface of the disk array were treated with UV-ozone (UVO Cleaner 42, Jelight Company Inc.) at ~1 cm sample-lamp distance for 3 minutes, aligned and attached to each other using ethanol as a temporary lubricant in between, and then baked at 80 °C for 30 min. To facilitate droplet formation, the channel surface was made hydrophobic prior to the experiment by treating the channel inner surface with Sigmacote (SL-2, Sigma-Aldrich) for 5~10 s followed by baking at 110°C for 30 min.

Fig. 1.

Device layout and system setup. (a) Microscope image (top) showing the channel layout on an array of permalloy (Ni0.8Fe0.2) disks and a schematic side view of the device (bottom). Fluid flow rates Q1, Q2, Q3 and Q4 are indicated at corresponding channels while the three T-junctions are labeled with T1, T2 and T3. (b) Schematic of full layout of the microfluidic channel. (c) Photograph of the device. (d) Photograph of the system consisting of four electromagnets and a solenoid that apply external magnetic field on the device. Tubings connected to computer-controlled syringes transfer fluid to or from the microfluidic channels of the device situated within the setup.

Preparation of the solutions

Magnetic bead solution (flow Q1)

Quantifications of the separation efficiency and encapsulation characteristics of the device were performed with magnetic bead solution that contains a mixture of:

7.9 µm diameter superparamagnetic microsphere solution (UMC4N/10150, Bang Laboratories, Inc.), and

3.34 µm diameter nonmagnetic bead solution (CP-30–10, Spherotech, Inc.).

Above solutions were diluted in 0.1% Triton X-100 (X100, Sigma-Aldrich) at final dilutions of 1:100 and 1:400 respectively.

Cell suspension (flow Q1)

Cell solution contained a mixture of:

Human breast cancer cells BT-474 labeled with 2.8 µm magnetic particles (Dynabeads M-270 Streptavidin, Life Technologies Corporation) functionalized with HER2 antibodies, and

red blood cells.

These cells were suspended in PBS (phosphate buffered saline) at 1~5 × 105 cells/mL concentration with 5 mg/mL Pluronic F-68 (P1300, Sigma-Aldrich), 5mM EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) and 1% BSA (bovine serum albumin).

Non-magnetic output (flow Q2)

Although flow Q2 withdraws fluid from the microfluidic channels, a buffer solution same as that used to suspend beads or cells was infused into the non-magnetic output channel (along with flows Q1, Q3 and Q4 from other channels) during the initial phase to fill the entire channels with fluid. After removing the air from all the channels, Q2 is set to the desired withdrawal rate.

Reagent solution (flow Q3)

Three types of solutions were used for the reagent channel, i.e. flow Q3 in Fig. 1a and b, depending on the experiment conducted:

0.1% Triton X-100 in de-ionized water for quantification experiments with the magnetic beads,

PBS (phosphate buffer saline) with 5 mg/mL Pluronic F-68, 5mM EDTA and 1% BSA for cell separation and encapsulation experiments, or

PBS with 1% BSA and 1.5 µM PI (propidium iodide) for cell separation and encapsulation followed by fluorescence analysis of cell viability.

The continuous phase solution (flow Q4)

Mineral oil (O121, Fisher Scientific), with 15 % Span 80 (sorbitan monooleate) (S6760, Sigma-Aldrich) as emulsifier, was used as the continuous phase that surrounds the aqueous droplets.

System setup

Microfluidics

Fluid flow in the microfluidic channel were controlled by syringe pumps (PHD Ultra Syringe Pump, Harvard Apparatus) through 25 and 50 µL syringes (7636–01 and 7637–01, Hamilton Company) and polyethylene tubings (inner diameter 0.40 mm, 720191, Harvard Apparatus) that transfer fluid to and from the device as shown in Fig. 1d. The flow rates at four of the microfluidic ports (Fig. 1a and b) are remotely controlled by program coded in LabVIEW (LabVIEW, National Instruments Corporation).

Magnetic and nonmagnetic input (Q 1),

Nonmagnetic output (Q 2),

Reagent input (Q 3), and

Oil input (Q 4).

The flow at the output channel for droplet collection was not controlled.

Magnetic manipulation

As shown in Fig. 1d, four electromagnets (OP-2025, Magnetech Corp) and a solenoid provide in-plane (Hx and Hy) and out-of-plane (Hz) components of the external magnetic field: Hext = (Hx, Hy, Hz). A LabVIEW program (LabVIEW, National Instruments Corporation) controls the current driving the electromagnets and solenoid allowing fields up to ~150 Oe to be produced and remotely tuned. Magnetic beads or labeled cells were manipulated across the permalloy disk array by rotation of the in-plane field, i.e. Hext = (H1·cosφ, H1·sinφ, Hz), φ = 0° to 180°, followed by reversing the orientation of Hz [30]. These steps result in the transport of the object around the disk periphery (e.g. from –x end to +x end) during the field rotation phase followed by its transfer to the adjacent disk (e.g. from +x end of one disk to –x end of next) when Hz is reversed. One period of the transport cycle consists of the rotation time (τ/2) and wait times before (τ/4) and after (τ/4) the inter-disk transfer is complete. The rate of transport is hence defined as f = 1/τ, i.e. the number of disks traversed by the object per unit time. With the ratio of |Hz| to H1 set fixed at 1.5 to 1, the two central parameters for magnetic manipulation are the magnitude of the in-plane field |H1| and the transport rate f.

Video capture

The sequence of events was observed through an optical microscope (Leica DM2500MH) with a 10x objective lens and recorded with a digital camera (QImaging Retiga EXi) interfaced with LabVIEW at a frame rate of 10~20 fps. The fluorescence signal from the PI (propidium iodide) dye was picked up with Leica’s Texas Red Filtercube (TX2).

System operation overview

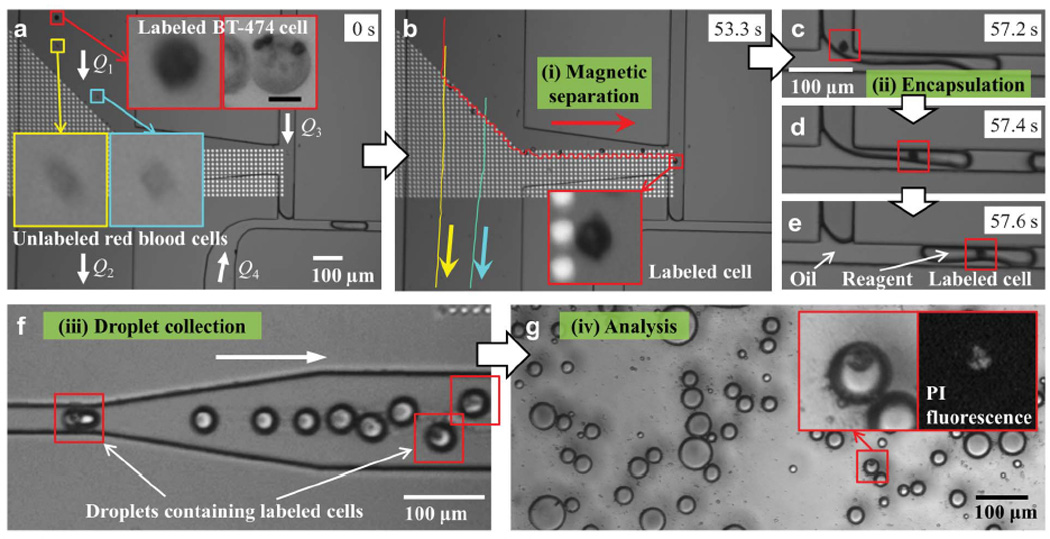

Magnetic and non-magnetic objects were sent down the input channel at flow rate Q1 while withdrawn at a rate Q2 same as or slightly higher than Q1 as shown in Fig. 1a and b. This constraint prohibits non-magnetic objects into the separation channel between junctions T1 and T2, while the mobile magnetic trap array captures magnetic objects and transports them towards the T2 junction where they are drawn by the reagent flow Q3 for eventual encapsulation at the T3 junction. As an example, Figure 2a shows magnetically labeled and unlabeled cells entering the input channel on the left. While the unlabeled ones followed the flow down the channel as shown in Fig. 2b, the labeled one was magnetically manipulated to the far right of the disk array, mixed with the reagent flow (Q3), and subsequently encapsulated into a droplet with the reagent as depicted in Fig. 2c–e. Encapsulated cells were then transferred down the output channel (Fig. 2f), collected in a tubing for further analysis. As an example, Figure 2h shows cell viability assay by fluorescence imaging of PI inside the encapsulated cells, which are dispersed between a glass substrate and cover glass.

Fig. 2.

Snapshots showing the process of magnetic separation, encapsulation, droplet collection and analysis. (a) At time t = 0 s, one labeled BT-474 cell and two unlabeled red blood cells (indicated by boxes and enlarged) enter from the top left branch of the channel with flow rate Q1. The flow rates at each of the channels are Q1 = Q2 = 75 nL/min, Q3 = 15 nL/min and Q4 = 30 nL/min. (b) At t = 53.3 s, movements of the three cells from t = 0 s are traced with lines. The labeled cell magnetically separated to the right is indicated by the box. (c-e) Sequential snapshots taken at t = 57.2, 57.4 and 57.6 s show the encapsulation process of the same labeled cell (indicated by the box) mixed with the reagent solution from flow Q3. (f) Snapshot taken from a separate video than that of (a-e) showing droplets being transferred down the output channel. Droplets contain solution of PI (propidium iodide) at 1.5 µM concentration, and those encapsulating labeled cells are indicated by the boxes. (g) Droplets collected from (f) are placed between a glass substrate and cover glass for detection of fluorescence signal from the PI dye.

Results and discussion

Quantification of the device with magnetic beads

Separation efficiency

Separation of targeted magnetic entities is achieved by the sequence of external magnetic fields (described in the Experimental Section). An important parameter characterizing separation efficiency of the device is defined by:

| (1) |

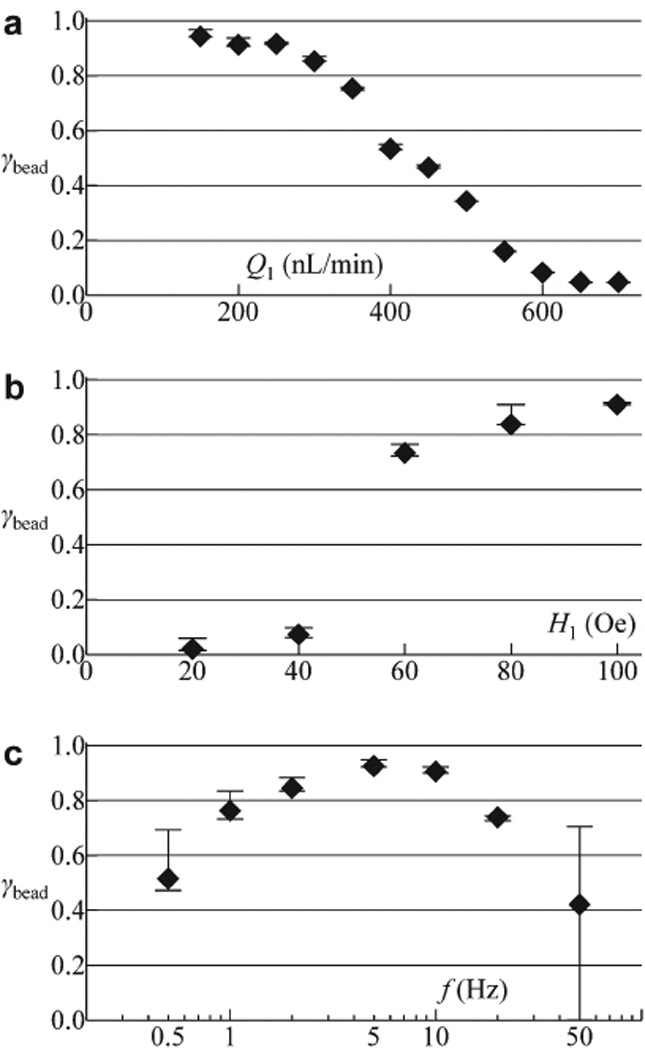

In this study magnetic and nonmagnetic bead solutions (Experimental Section) were used to evaluate γbead. As summarized in Fig. 3, the influence of the input flow rate Q1, in-plane magnetic field strength H1 (|Hz| = 1.5 H1) and transport rate f on the efficiency γbead were investigated.

Fig. 3.

Quantification of the separation efficiency γbead for 7.9 µm diameter magnetic beads. γbead is plotted as a function of (a) input flow rate Q1 (at H1 = 100 Oe, f = 5 Hz), (b) in-plane field strength H1 (at Q1 = 250 nL/min, f = 2 Hz) and (c) rate of transport f (at Q1 = 250 nL/min, H1 = 100 Oe). Experiments are performed at Q3 = 100 nL/min while the oil input was absent. Data points (plotted as filled diamonds) are based on measured number of separated magnetic beads while the upper (or lower) errors take into account magnetic beads that were (or were not) supposed to be separated were it not for flow fluctuation. The number of magnetic beads counted range from 200 to 450, yielding an estimated statistical error of ~2001/2/200 = 7.1% due to finite sample size.

For fixed H1 = 100 Oe and f = 5 Hz, Figure 3a depicts that high separation efficiency (γbead > 90%) was maintained until the input flow rate Q1 exceeds ~300 nL/min. Beyond this threshold, γbead steadily decreases to less than 10% at Q1 ≥ 600 nL/min. As an increasing hydrodynamic drag force could account for the decrease in γbead, an estimate on the force required to detach a bead, with typical magnetic susceptibility of 0.1‡, off the magnetic trap yields ~100 pN. This corresponds to a flow rate of Q1 = 970 nL/min based on Stokes law (neglecting near-wall effects). However, the observed flow rate at which γbead starts decreasing from its high value of > 90% is ~300 nL/min, a value much lower than the estimated flow rate (970 nL/min). This discrepancy suggests other explanations for the decrease in γbead: The higher flow rate (Q1) results in (i) higher bead throughput and therefore fewer vacant disks on the array to accommodate incoming beads into the T1-T2 channel, and (ii) less time for beads floating above the array surface to be pulled towards the disks by the magnetic trapping force or gravity.

As expected, Fig. 3b illustrates a greater magnetic field strength (H1) results in an enhanced magnetic force and therefore higher γbead for a given flow rate Q1 and transport rate f.

Figure 3c illustrates that increasing f while keeping other parameters fixed, i.e. more rapid rotation of the in-plane field (magnitude H1) and less wait time before and after reversing of the out-of-plane field (Hz), yielded more effective separation for frequency f up to ~5 Hz. In this case, rapid transport of the beads into the separation channel yielded more vacant disks to accommodate incoming beads, hence the increase in γbead. Transport rates higher than 5 Hz become less effective at separation since (i) motion of the trap against the flow (Q1) during the field rotation cycle decreases the minimum flow rate required to detach the bead from 970 nL/min (f = 5 Hz) to 480 nL/min (f = 25 Hz) and to zero (f = 50 Hz) according to calculation, and (ii) too short a wait time (τ/4 < 10 ms) during the inter-disk transfer phase may result in stalling of the bead. Stalled beads are observed to be sensitive to flow fluctuation, i.e. any slight flow in channel T1-T2 could push the stalled beads forward or backward, which is depicted by the large error bar at f = 50 Hz in Fig. 3c.

To summarize, the causes for decrease in the separation efficiency are:

flow driven bead detachment off the trap,

bead stalling or diversion by flow during inter-disk hopping phase,

high bead occupancy on disk array, and

beads flowing above disk array.

An optimal manipulation speed thus depends on the flow rates, bead concentration and strength of the trap array.

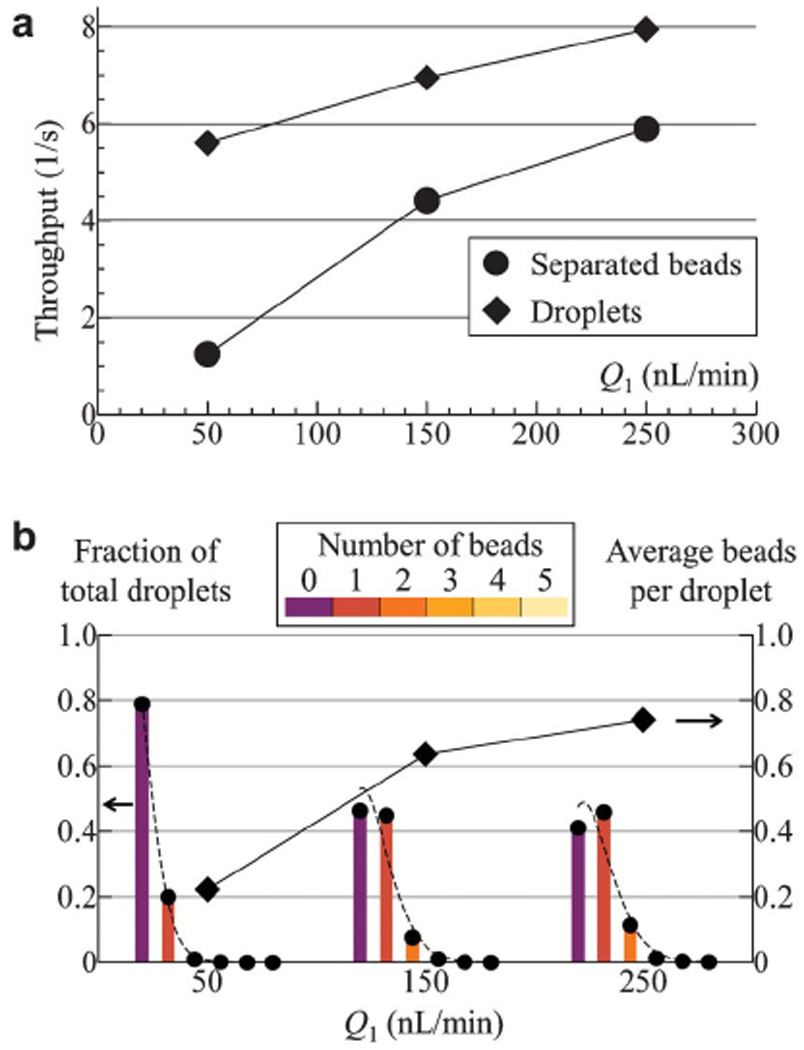

Encapsulation characteristics

To quantify the encapsulation aspect of the device, the same magnetic bead solution described above (see Experimental Section) is used. As shown in Fig. 4a, droplet throughput, i.e. droplet generation rate, is maintained at 5~8 droplets per second, while the separated bead throughput (entering the dropletization junction T3) is varied from 1 to 6 beads per second by tuning the input flow rate Q1 (note Q2 is set equal to Q1). This feature enables the number distribution of beads encapsulated within the droplets to be manipulated to some extent as shown in Fig. 4b.

Fig. 4.

Quantification of the encapsulation characteristics with 7.9 µm diameter magnetic beads. (a) Separated bead (filled circles) and droplet (filled diamonds) throughputs as a function of input flow rate Q1. Other experimental parameters are kept fixed at H1 = 100 Oe, f = 5 Hz and Q4 = 2Q3 = 30 nL/min. (b) Extracted from the same experiment as in (a), fraction of droplets (corresponding to the left vertical axis) containing various number of beads are plotted as dots with underlying color-coded bars at flow rates Q1 = 50, 150 and 250 nL/min. Dashed curves at each Q1 represent Poisson distribution function (Equation (2)) with mean value λ set by the measured average number of beads per droplet (plotted as filled diamonds with values corresponding to the right vertical axis). Total number of droplets taken into account ranges from 840 to 1251, and an estimate on the statistical deviation due to finite sample size is ~8401/2/840 = 3.5%.

The encapsulation can be approximated as discrete independent events that occur randomly in time. The probability for a droplet to encapsulate k beads is given by the Poisson distribution function P(k): [43]

| (2) |

where λ is the mean of P(k), i.e. average number of beads per droplet. It has long been a challenge in microfluidic-based approaches to overcome the inherent Poisson statistics in typical encapsulation processes and to achieve single-object encapsulation [44,45]. It follows from Equation (2) that while the percentage of single-object droplets P(1) is maximized only at P(1)λ=1 = 36.8% along with comparable number of empty droplets P(0)λ=1 = 36.8% and multi-object droplets P(k>1)λ=1 = 26.4%, reducing the average number of objects per droplet could increase P(1)/P(k>1) but at the expense of a large fraction of empty droplets, e.g. P(1)/P(k>1) = 19 but P(0) = 90.5% at λ = 0.1.

Figure 4b illustrates that the number distribution of beads in a droplet at each flow rate Q1 largely follow Poisson distribution based on the measured average number of beads per droplet. Interestingly, the fraction of single-bead droplets in our study exceeds that imposed by Poisson statistics by a small yet observable amount of ~11% (greater than the estimated statistical error of 3.5%) at Q1 = 150 and 250 nL/min in Fig. 4b. We attribute this to the fact that at higher throughput, i.e. shorter bead-to-bead distance, a rotating magnetic field with |Hz|/H1 = 1.5 results in repulsive dipolar interactions between the beads travelling from junction T2 to T3, causing them to self-arrange into a more evenly spaced configuration before being encapsulated. This feature increases the fraction of single-bead droplets.

Separation and encapsulation of labeled cells

Separation of a heterogeneous mixture of labeled and unlabeled cells (described in the Experimental Section) was studied. As shown in Fig. 5a, due to the lower magnetic moment of the labeling particle, larger cell size and propensity to aggregate, the optimal flow rate to achieve efficient separation of the cells (γcell > 75%), was at Q1 < 50 nL/min while the transport rate is f = 1 Hz. Both the size and shape of the cells or aggregates affect the separation efficiency. Non-aggregating single cells have a higher γcell than aggregates due to smaller fluid drag force; linear shaped (chain) aggregates tend to orient parallel to the flow direction and thereby experience less drag force when compared to more extended aggregates. Hence, in addition to marker-specific separation, the presented scheme is also selective based on variation of object size, shape and extent of cell aggregation.

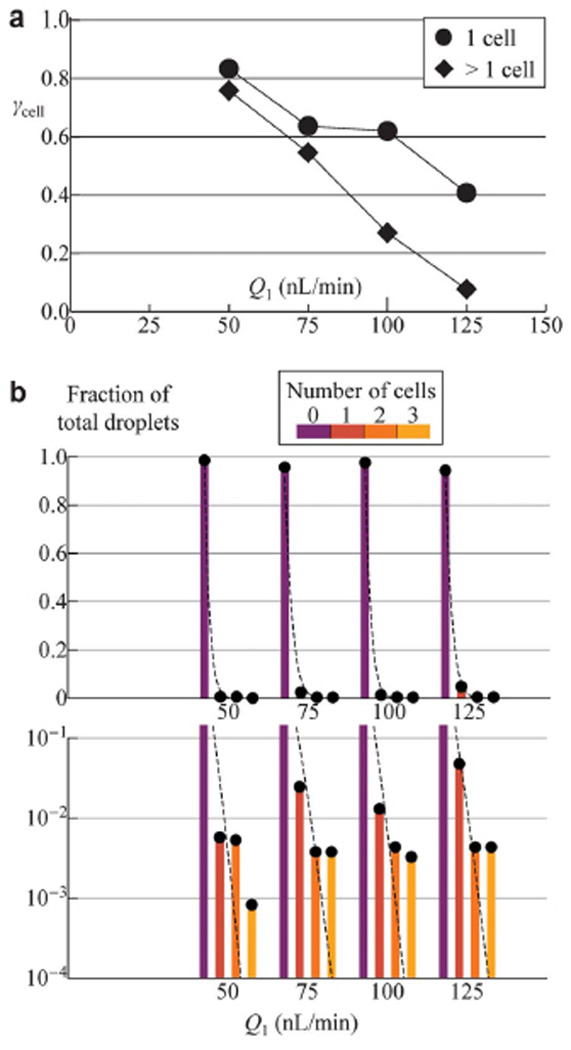

Fig. 5.

Separation efficiency (γcell) and encapsulation characteristics of labeled BT-474 cells. (a) γcell is plotted as a function of input flow rate Q1 while other experimental parameters are kept fixed at H1 = 100 Oe, f = 1 Hz and Q4 = 2Q3 = 30 nL/min. Each cell aggregate is counted as one entity, where single-cell (filled circles) and multi-cell (filled diamonds) entities are plotted separately. Total cell entity counts range from 33 to 58 for each Q1, and the estimated statistical error due to finite sample size is ~331/2/33 = 17%. (b) Extracted from the same experiment as in (a), fraction of droplets containing various number of cells are plotted as dots with underlying color-coded bars at flow rates Q1 = 50, 75, 100 and 125 nL/min. Dashed curves at each Q1 represent Poisson distribution function with mean value λ set by the measured average number of cells per droplet. Total number of droplets taken into account ranges from 217 to 2400, and an estimate on the statistical deviation due to finite sample size is ~8401/2/840 = 6.8%.

Encapsulation of labeled cells proves to be fundamentally different from encapsulating magnetic beads. The reduced flow rate for effective separation, tendency of cell aggregation and adhesion to surfaces lowers the separated cell throughput to below 0.15 cells per second and an average of lower than one cell per ten droplets at flow rates of Q1 = 50 ~ 125 nL/min. Although at such a low λ value of 0.1, Poisson statistics predicts a high single-cell to multi-cell droplet ratio of 19 (see previous section), the observed difference between single-cell and multi-cell droplet fractions still falls within an order of magnitude as depicted in Fig. 5b. This can be understood from the assumption of the encapsulation process as independent random events in Poisson statistics – a feature that becomes less valid due to the tendency for a cell to carry other cells into the same droplet through aggregation. As shown in Fig. 5b, measured trend indicates that multi-cell droplet fractions are indeed higher than those predicted by the Poisson distribution functions P(k) (k = 2, 3, …), whereas single-cell droplet fractions are lower than P(1) at corresponding flow rates. Such deviation from Poisson statistics may offer opportunities for investigating the probability of time-correlated events and insights on cell-cell interaction.

Cell staining and viability assay

The unique channel layout of the device shown in Fig. 1 opens up a broad range of downstream applications after the encapsulation of selected cells. The reagent flow (Q3) from the branch channel (Fig. 1b) not only draws the separated magnetic object towards T3 junction, thereby facilitating the encapsulation process, it also offers several advantages:

Separated objects enter a fresh chemical environment of the reagent several seconds before encapsulation, reducing contamination from the non-separated objects and degradation of the reagent over time.

Minimal use of the reagent, i.e. all fluid from flow Q3 is encapsulated in the droplet.

Different surface chemistries can be introduced via flow Q1 than to Q3. For example, while a hydrophilic surfactant is desirable in Q1 as it reduces cell adhesion to the surface, it hinders the stability of water-in-oil droplets if encapsulated. The reagent channel therefore allows the chemistry surrounding the separated cells to be switched from adhesion-prevention (with 5 mg/mL Pluronic F-68 surfactant) to droplet-friendly solvent (no surfactant).

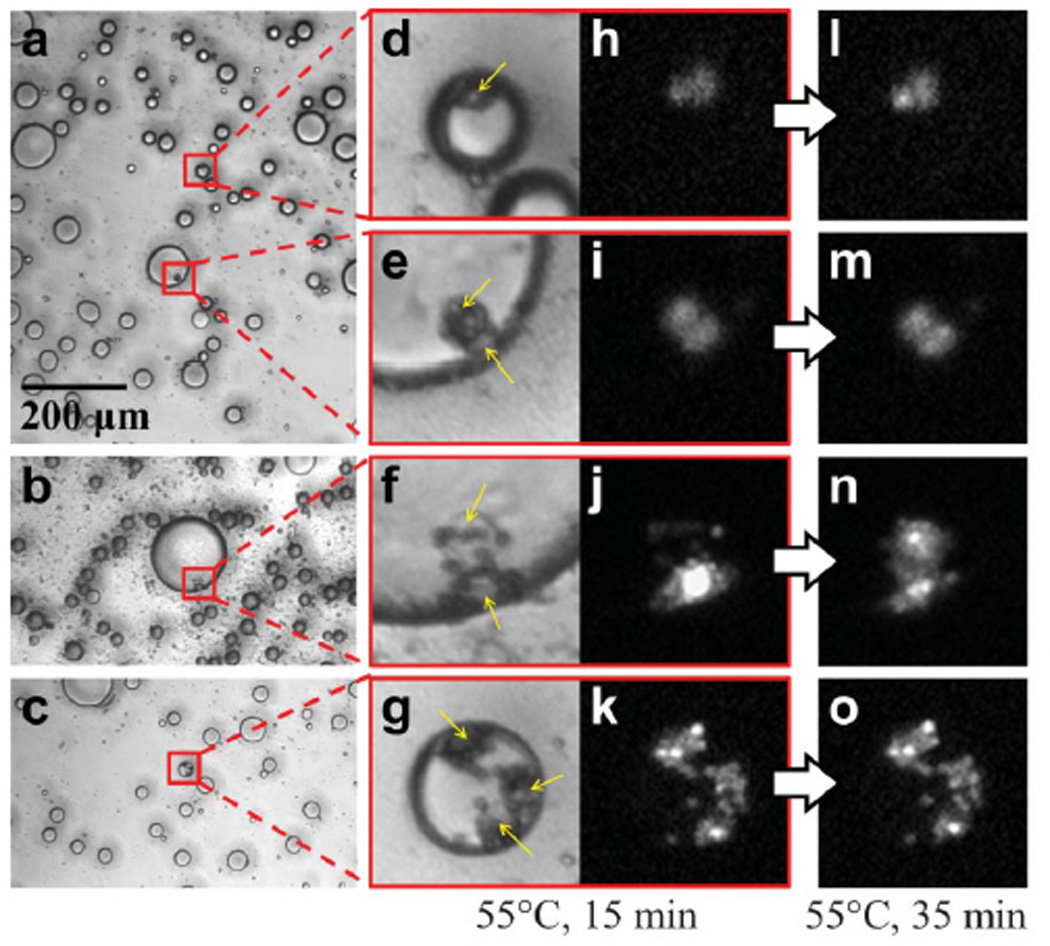

Utilizing the reagent channel to transfer PI dye, Figure 6 shows an example of viability assay performed on the encapsulated cells at a raised temperature of 55°C: Labeled BT-474 cells were magnetically separated and encapsulated in droplets containing PI and subsequently collected in the output tubing and re-dispersed onto a glass substrate. The sample was mounted with a cover glass for further preservation and ease of observation (Fig. 6a–d). PI is generally excluded outside the membrane by live cells, and since the fluorescence intensity of PI increases by many fold when it enters a dead cell to bind with nucleic acids, it serves as an indicator of cell viability. Prior to and within the first 25 min of heating at 55 °C, many encapsulated cells, assayed by the PI fluorescence retention (Fig. 6e and f), appear to be dead. After 35 min of heating, the increased fluorescence intensity in Fig. 6h indicates the eventual occurrence of death of the corresponding cell. The fluorescence intensity change as function of cell death is reflected in Fig. 6i. This proof-of-concept experiment shows the potential to detect cell-to-cell variation in isolated chemical environments (droplets) resulting from the separation-encapsulation device.

Fig. 6.

Cell viability detection with PI (propidium iodide) fluorescence of the encapsulated cells at 55°C. (a,b) Droplets placed between a glass substrate and cover glass are heated at 55°C for 15 min. Photographs of two droplets encapsulating labeled BT-474 cells are enlarged (c,d) with their respective fluorescence images (e,f) of the PI dye. (g,h) Fluorescence images taken at 35 min after heating. (i) PI fluorescence intensities from the encapsulated cells shown in (c) and (d) are plotted as a function of time. The intensities are integrated over the pixels of the fluorescing cells within the droplets, subtracted by the average background noise and then divided by (normalized according to) the droplet area to account for the amount of PI contributing to the signal.

Potential modules for integration

In addition to the separation and encapsulation functionalities, we envision other useful experimental modules that could be integrated into the device:

Analysis techniques such as single-cell PCR (polymerase chain reaction) for the amplification and detection of rare biological signatures of individual cells could be realized by introducing temperature zones on the microfluidic channels.

Electrical measurement could be performed by replacing mineral oil with, for example, the conductive ionic liquid for determining properties as the conductance or stiffness of the cell or detecting the change in surrounding solvent.

On-chip labeling, upstream of separation, through properly designed channels to mix the functionalized magnetic particles with cells would reduce the preparation time and amount of reagent needed for the immunomagnetic labeling of targeted cells.

Overcoming the Poisson statistics of encapsulation by incorporating real-time feedback on the rate of transport (f): By monitoring the traffic of magnetic objects in channels T1-T2 and T2-T3, one could achieve a more uniform throughput of separated objects and thus encapsulating a more consistent number of objects per droplet.

Conclusions

We have presented a mechanism for encapsulating cells immunomagnetically selected from a heterogeneous solution on a chip-based device. The device integrates microfluidics technology with magnetic tweezers array to combine the functionality of sorting and encapsulation of magnetic beads or labeled cells. The portable device can be fabricated at low cost and requires small (~microliters) fluid volumes, thereby permitting fast processing and solution analysis. With remote, programmable and automated transport on simultaneous cells (multiplexing), we demonstrate separation of breast cancer cell line (BT474) with greater than 75% separation efficiency under optimal flow rates and 100% purity: no red blood cells are encapsulated. Cell viability assay subsequent to the encapsulation was also demonstrated, permitting analysis on a single-cell basis rather than averaging properties over bulk populations. These on-chip functionalities with the potential to be integrated with other useful modules promise to impact biomedical applications, cancer research, stem cell biology and immunology.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Summary of experimental parameters

| Experiments | Manipulation rate f (Hz) |

In-plane field H1 (Oe) |

Flow rates (nL min −1) Q1 |

Q2 | Q3 | Q4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (i) Bead separation vs. Q1 | 5 | 100 | 150–700 | ~ Q1 + 10 | 100 | a |

| (ii) Bead separation vs. H1 | 2 | 20–100 | 250 | 260 | 100 | a |

| (iii) Bead separation vs. f | 0.5–50 | 100 | 250 | 260 | 100 | a |

| (iv) Bead encapsulation vs. Q1 | 5 | 100 | 50–250 | Q1 | 15 | 30 |

| (v) Cell separation and encapsulation vs. Q1 | 1 | 100 | 50–125 | ~Q1 + 10 | 15 | 30 |

| (vi) Cell separation, encapsulation and analysis | 1 | 100 | 50 | Q1 | 100 | 50 |

Flow not controlled.

Acknowledgements

A. C. thanks H.-C. Chung and K. Kwak for advice on fabrication of the device and B. Yu, X.-M. Wang and J.-Y. Ma for help on cell culturing. R.S. acknowledges funding from the U.S. Army Research Office under contract W911NF-10–1–0353. R.S, J. J. C and R.B. acknowledge the support of the NSF NSEC at OSU grant number EEC-0914790.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [details of any supplementary information available should be included here]. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

Based on susceptibility measurement on 8.18 µm diameter beads from the same company (UMC4F/9560, Bang Laboratories, Inc.) and scaling by the ratio between their magnetic contents, 4%:2.4%.

Notes and references

- 1.Skojerbo KJ. Anal. Chem. 1995;67:449. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elowithz MB, Levine AJ, Siggia ED, Swain PS. Science. 2002;297:1183. doi: 10.1126/science.1070919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avery SV. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006;4:577. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dalerba P, Kalisky T, Sahoo D, Rajendran PS, Rothenberg ME, Leyrat AA, Sim S, Okamoto J, Johnston DM, Qian D, Zabala M, Bueno J, Neff NF, Wang J, Shelton AA, Visser B, Hisamori S, Shimono Y, van de Wetering M, Clevers H, Clarke MF, Quake SR. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:1120. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Powell AA, Talasaz AH, Zhang H, Coram MA, Reddy A, Deng G, Telli ML, Advani RH, Carlson RW, Mollick JA, Sheth S, Kurian AW, Ford JM, Stockdale FE, Quake SR, Pease RF, Mindrinos MN, Bhanot G, Dairkee SH, Davis RW, Jeffrey SS. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33788. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fritzsch FSO, Dusny C, Frick O, Schmid A. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2012;3:129. doi: 10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-062011-081056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yi C, Li C-W, Ji S, Yang M. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2006;560:1. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishii S, Tago K, Senoo K. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010;86:1281. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2524-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhagat AA, Bow H, Hou HW, Tan SJ, Han J, Lim CT. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2010;48:999. doi: 10.1007/s11517-010-0611-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohnuma K, Yomo T, Asashima M, Kaneko K. BMC Cell Biology. 2006;7:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-7-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang X, Chen S, Kong M, Wang Z, Costa KD, Li RA, Sun D. Lab Chip. 2011;11:3656. doi: 10.1039/c1lc20653b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morishima K, Arai F, Fukuda T, Matsuura H, Yoshikawa K. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1998;365:273. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Becker FF, Wang X-B, Huang Y, Pethig R, Vykoukal J, Gascoyne PRC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1995;92:860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng J, Sheldon EL, Wu L, Uribe A, Gerrue LO, Carrino J, Heller MJ, O'Connell JP. Nat. Biotechnol. 1998;16:546. doi: 10.1038/nbt0698-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Müller T, Gradl G, Howitz S, Shirley S, Schnelle Th, Fuhr G. Biosens. Bioelectron. 1999;14:247. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu X, Bessette PH, Qian J, Meinhart CD, Daugherty PS, Soh HT. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:15757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507719102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li PCH, Harrison DJ. Anal. Chem. 1997;69:1564. doi: 10.1021/ac9606564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Šafařík I, Šafaříková M. J. Chromatography B. 1999;722:33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furdui VI, Harrison DJ. Lab Chip. 2004;4:614. doi: 10.1039/b409366f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pamme N, Wilhelm C. Lab Chip. 2006;6:974. doi: 10.1039/b604542a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou Y, Wang Y, Lin Q. J. MEMS. 2010;19:743. doi: 10.1109/JMEMS.2010.2050194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robert D, Pamme N, Conjeaud H, Gazeau F, Iles A, Wilhelm C. Lab Chip. 2011;11:1902. doi: 10.1039/c0lc00656d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin X, Abbot S, Zhang X, Kang L, Voskinarian-Berse V, Zhao R, Kameneva MV, Moore LR, Chalmers JJ, Zborowski M. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39491. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jung Y, Choi Y, Han K-H, Frazier AB. Biomed. Microdevices. 2010;12:637. doi: 10.1007/s10544-010-9416-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams JD, Kim U, Soh HT. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:18165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809795105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams JD, Thévoz P, Bruus H, Soh HT. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009;95:254103. doi: 10.1063/1.3275577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee H, Jung J, Han S-I, Han K-H. Lab Chip. 2010;10:2764. doi: 10.1039/c005145d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yellen BB, Erb RM, Son HS, Hewlin R, Jr, Shang H, Lee GU. Lab Chip. 2007;7:1681. doi: 10.1039/b713547e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vieira G, Henighan T, Chen A, Hauser AJ, Yang FY, Chalmers JJ, Sooryakumar R. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009;103:128101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.128101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henighan T, Chen A, Vieira G, Hauser AJ, Yang FY, Chalmers JJ, Sooryakumar R. Biophys. J. 2010;98:412. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spurgeon SL, Jones RC, Ramakrishnan R. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1662. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wheeler AR, Throndset WR, Whelan RJ, Leach AM, Zare RN, Liao YH, Farrell K, Manger ID, Daridon A. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:3581. doi: 10.1021/ac0340758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zare RN, Kim S. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2010;12:187. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-070909-105238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.White AK, VanInsberghe M, Petriv OI, Hamidi M, Sikorski D, Marra MA, Piret J, Aparicio S, Hansen CL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011;108:13999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019446108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song H, Chen DL, Ismagilov RF. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:7336. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teh S-Y, Lin R, Hung L-H, Lee AP. Lab Chip. 2008;8:198. doi: 10.1039/b715524g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Köster S, Angilè FE, Duan H, Agresti JJ, Wintner A, Schmitz C, Rowat AC, Merten CA, Pisignano D, Griffiths AD, Weitz DA. Lab Chip. 2008;8:1110. doi: 10.1039/b802941e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo MT, Rotem A, Heyman JA, Weitz DA. Lab Chip. 2012;12:2146. doi: 10.1039/c2lc21147e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brouzes E, Medkova M, Savenelli N, Marran D, Twardowski M, Hutchison JB, Rothberg JM, Link DR, Perrimon N, Samuels ML. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009;106:14195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903542106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang H, Jenkins G, Zou Y, Zhu Z, Yang CJ. Anal. Chem. 2012;84:3599. doi: 10.1021/ac2033084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chabert M, Viovy J-L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008;105:3191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708321105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Um E, Lee S-G, Park J-K. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010;97:153703. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moon S, Gurkan UA, Blander J, Fawzi WW, Aboud S, Mugusi F, Kuritzkes DR, Demirci U. PLoS One. 2011;6:8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abate AR, Chen C-H, Agresti JJ, Weitz DA. Lab Chip. 2009;9:2628. doi: 10.1039/b909386a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kemna EWM, Schoeman RM, Wolbers F, Vermes I, Weitz DA, van den Berg A. Lab Chip. 2012;12:2881. doi: 10.1039/c2lc00013j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.