Abstract

Introduction

For decades, clinicians dealing with immunocompromised and critically ill patients have perceived a link between Candida colonization and subsequent infection. However, the pathophysiological progression from colonization to infection was clearly established only through the formal description of the colonization index (CI) in critically ill patients. Unfortunately, the literature reflects intense confusion about the pathophysiology of invasive candidiasis and specific associated risk factors.

Methods

We review the contribution of the CI in the field of Candida infection and its development in the 20 years following its original description in 1994. The development of the CI enabled an improved understanding of the pathogenesis of invasive candidiasis and the use of targeted empirical antifungal therapy in subgroups of patients at increased risk for infection.

Results

The recognition of specific characteristics among underlying conditions, such as neutropenia, solid organ transplantation, and surgical and nonsurgical critical illness, has enabled the description of distinct epidemiological patterns in the development of invasive candidiasis.

Conclusions

Despite its limited bedside practicality and before confirmation of potentially more accurate predictors, such as specific biomarkers, the CI remains an important way to characterize the dynamics of colonization, which increases early in patients who develop invasive candidiasis.

Keywords: Candida albicans, Candidemia, Invasive candidiasis, Colonization, Colonization index, Empirical treatment, Nosocomial infections

Introduction

Candida spp. colonization occurs in up to 80 % of critically ill patients after 1 week in intensive care [1–3]. This very high proportion contrasts strongly with the low rate of invasive candidiasis in less than 10 % of them [4, 5]. Despite recent advances in microbiological techniques, early diagnosis of invasive candidiasis remains problematic and microbiological documentation often occurs late in the course of infection [6–8]. This explains its high crude and attributable mortality, i.e., in the range reported for septic shock [9–11].

Early empirical treatment of severe candidiasis has improved survival, but is responsible for the overuse of antifungals [12–14]. This overuse not only contributes to a huge financial burden, but has also promoted a shift to Candida species with reduced susceptibility to antifungal agents [15, 16]. Unfortunately, recent guidelines resulting from expert consensus failed to provide high-level recommendations about empirical antifungal treatment or to clarify the nature of such treatment strategies [8, 17, 18]. Despite limited levels of evidence, empirical treatment currently relies on the positive predictive value of risk assessment strategies, such as the colonization index (CI), Candida score, and predictive rules based on combinations of risk factors [19–21].

Improved knowledge of the pathophysiological specificities of invasive candidiasis should promote better use of clinical tools in the evaluation of patients who could truly benefit from early antifungal therapy [22]. In contrast to most bacterial infections, invasive candidiasis is characterized by a 7–10-day delay between exposure to risk factors and infection development [23–25]. This time window provides a unique opportunity for the implementation of a structured approach to the rigorous selection of patients likely to benefit from early empirical antifungal treatment [19, 26].

The CI is the most widely studied clinical tool for the early risk assessment of invasive candidiasis among at-risk patients. The primary objective of this review is to highlight its role in this setting. The use of colonization dynamics, as assessed by the CI, for the early detection of patients likely to benefit from early antifungal treatment is also explored in comparison with other tools currently available in clinical practice. Finally, we also propose a research agenda for the next decade.

Pathophysiology of invasive candidiasis

Nosocomial exogenous transmission of Candida has been well described [27]. Of note, both endogenous and exogenous colonization can co-exist in the clinical setting [1]. However, carefully designed studies using genotyping of Candida strains confirmed that endogenous colonization is responsible for the large majority of severe candidiasis [28, 29].

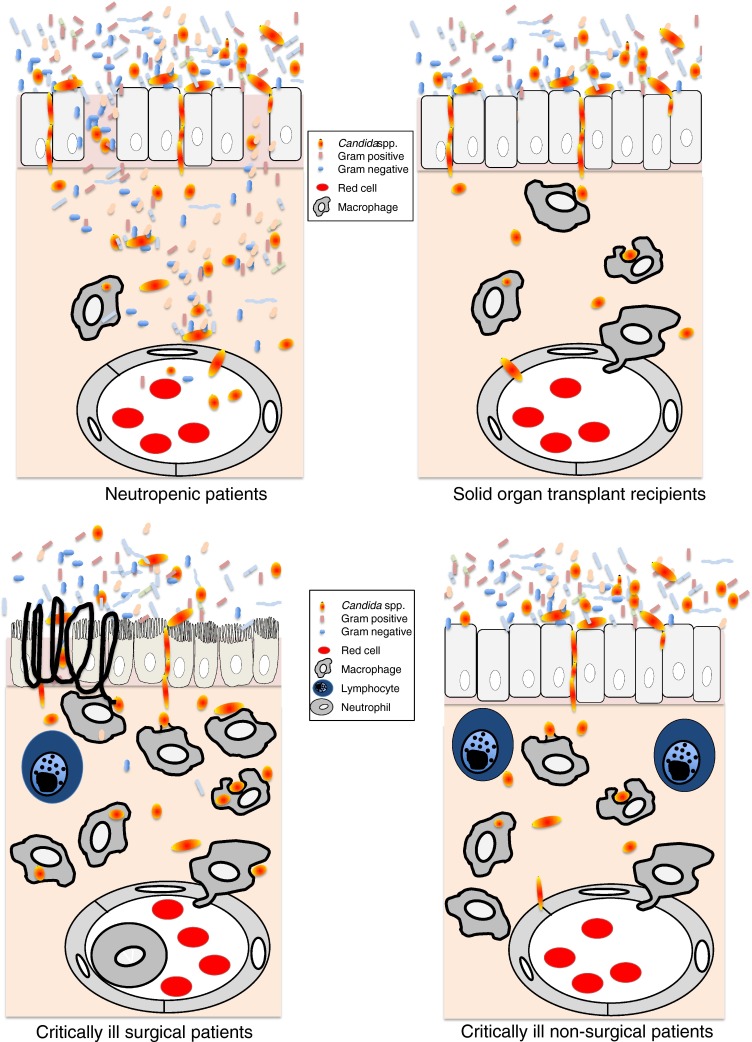

The epidemiology of invasive candidiasis has some important differences in immunocompromised and critically ill patients (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Pathophysiology of invasive candidiasis in different patient populations. Detailed mechanisms are summarized in the corresponding sections of the text

Neutropenic and bone marrow transplant recipients

Neutrophils are essential in the defense against invasive candidiasis [30]. Their prolonged absence in neutropenic patients or those with functional impairment after bone marrow transplantation, combined with the selective pressure of frequent and repetitive exposure to antibacterial agents, plays a major role in the development of invasive candidiasis in these patients. A high density of Candida spp. on mucosal surfaces injured by chemotherapy develops progressively and is responsible for fungal translocation with a high risk of candidemia. The use of systematic antifungal prophylaxis in the past three decades explains the epidemiology of Candida infection, typically characterized by breakthrough invasive candidiasis [31, 32]. Infection is almost always caused by a Candida strain resistant to the antifungal agent used [15, 33].

Solid organ transplant recipients

Anti-rejection therapy increases the risk for Aspergillus and other filamentous fungal infections in solid organ transplant recipients, except among those receiving small bowel and liver transplants, in whom additional specific surgical factors further modify the epidemiology of disease [34, 35]. Prolonged and intense impairment of cellular T cell-mediated immune response may contribute to the high proportion of cutaneous and mucosal candidiasis [36]. This factor has justified the use of systematic antifungal prophylaxis in these patients in whom, as among neutropenic patients and bone marrow transplant recipients, breakthrough Candida spp. infection develops with strains resistant to the agent used [18].

Nonsurgical critically ill patients

In nonsurgical critically ill patients, the continuous and prolonged support of failing organs and the selective pressure of broad-spectrum antibiotics constitute key risk factors for invasive candidiasis. Support of organ failure requires the use of numerous devices, such as intravascular catheters, endotracheal tubes, naso- and oro-gastric tubes, and Foley catheters, which are frequently colonized by Candida spp. as a result of the high affinity of their biofilm [1]. These specificities may explain progressive colonization in a high proportion of patients after prolonged stay in the intensive care unit (ICU) [6, 37, 38]. They may also explain a higher proportion of catheter-related infections in the absence of severe immune impairment [39]. In this context, the role of exposure to steroids largely used to improve the speed of recovery from circulatory failure remains to be determined.

Limited data are available on the usefulness of prophylaxis and recent guidelines did not include recommendation for antifungal prophylaxis in nonsurgical critically ill patients [17, 18, 40].

Critically ill patients recovering from abdominal surgery

Additional factors should be considered in patients after abdominal surgery [41]. Any perforation or opening of the digestive tract results in contamination of the peritoneum by bowel flora. In most cases, surgical cleaning of the abdominal cavity, eventually combined with antibiotics, is sufficient to allow full recovery [42]. Except for patients presenting with nosocomial peritonitis and some of those presenting with septic shock and multiple organ failure, the identification of Candida spp. has no clinical significance under these conditions [22]. Recurrent peritonitis following anastomotic leakage or persistent inflammation may be required for the progression of Candida spp. colonization to invasive candidiasis [43]. However, the development of invasive candidiasis requires concomitant exposure to additional factors, such as an increasing amount of Candida spp. in a non-functioning bowel, prolonged antibiotic treatment, and/or requirement for organ support. In contrast to nonsurgical patients, these particularities explain why a high proportion of invasive candidiasis cases do not manifest with candidemia and develop only late in the course of the disease [44].

Non-candidemic invasive candidiasis includes intra-abdominal abscess and peritonitis defined by one of the following culture results from specimens obtained at surgery: (1) monomicrobial growth of Candida spp.; (2) any amount of Candida spp. growth within a mixed-flora abscess; or (3) moderate or heavy growth of Candida spp. in mixed-flora peritonitis treated with appropriate antibacterial therapy according to susceptibility testing [43–46].

Two small prospective studies, including one placebo-controlled, suggested that antifungal prophylaxis in patients presenting with anastomotic leakage after abdominal surgery may prevent the development of invasive candidiasis [18, 45, 46].

In patients with severe acute necrotizing pancreatitis, invasive candidiasis develops with similar pathophysiological characteristics. Progressive colonization of the bowel within the first 2 weeks of the disease results in translocation into necrotic tissues, and fungal infections have been documented in up to 10 % of patients not exposed to antibiotics.

Critically ill patients with Candida isolated from the respiratory tract

Candida spp. colonization of the airway is frequently reported in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients, and its clinical significance is difficult to evaluate. Candida has a low affinity for alveolar pneumocytes and histologically documented pneumonia has been rarely reported. Hematogenous dissemination in the context of candidemia [1] may be responsible for multiple pulmonary abscesses and should be viewed as a distinct entity. Hence the existence of true candidal pneumonia is doubtful and recovery of Candida spp. from the respiratory tract should generally be considered as colonization and does not justify antifungal therapy [17–19].

Candida colonization

The distinction between patients with Candida spp. colonization who did not require treatment and those likely to develop invasive infection was identified as a difficult clinical challenge in the field of infectious diseases more than 40 years ago [47]. After the description in the early 1970s of Candida infection in surgical patients, manifesting as “disseminated candidiasis” and characterized by persistent fungemia and multiple disseminated microabscesses on autopsy, several authors reported that it might be preceded by fungal colonization. Klein and Watanakunakorn [48] reported the presence of visceral microabscesses in up to 30 % of patients with Candida spp. colonization and recommended treatment of all such patients with critical illness or persistent candidemia.

Solomkin et al. confirmed this concept in a detailed review of 63 surgical patients with postoperative candidemia. Among 51 patients who developed candidemia as a late complication of intra-abdominal infection, adequate antifungal treatment (>3 mg/kg amphotericin B) resulted in survival of 10/15 patients compared with 6/36 untreated patients. Autopsies revealed visceral Candida spp. microabscesses in 7/20 patients [42, 49]. Moreover, a digestive fungal source was identified in nearly all patients, and candidemia was considered to originate from intestinal Candida spp. growth in the presence of mucosal loss.

Calandra et al. provided further evidence of the clinical significance of Candida colonization of the peritoneum in surgical patients [39]. In a series of 49 patients with spontaneous perforation (n = 28) or surgical opening of the digestive tract (n = 21), 19 (39 %) patients developed invasive candidiasis, including 7 cases of intra-abdominal abscesses and 12 cases of peritonitis [43]. Invasive candidiasis developed significantly more frequently in patients who had undergone surgery for acute pancreatitis than in those with gastrointestinal perforations (90 vs. 32 %, p = 0.005) or other disorders, such as diseases of the biliary tract or colon (90 vs. 17 %, p = 0.003). Invasive candidiasis was associated significantly with an initially high or increasing amount of Candida spp., as assessed by semiquantitative cultures. Compared with uninfected patients, Candida spp. showed light, moderate, and heavy growth from the first positive specimen in 26 (87 %) vs. 9 (47 %), 4 (13 %) vs. 6 (32 %), and 0 vs. 4 (21 %) infected patients, respectively (p = 0.005). Moreover, the amount of Candida spp. cultured from subsequent specimens increased in 15 (79 %) infected patients and only 2 (7 %) uninfected patients (p < 0.001) [39].

Candida colonization index: the missing link

In the early 1990s, the origin of Candida spp. infection was highly debated [50]. Whether the infection was exogenous or endogenous in origin, and whether patients could become colonized with strains from the surrounding environment or with their “own” strains of Candida spp. was uncertain. We tested the hypothesis that yeast colonization would precede infection in critically ill patients [23]. We determined the genotypic characteristics of 322 Candida spp. collected prospectively from 29 critically ill patients who developed significant colonization under routine culture surveillance two to three times weekly over a 6-month period. These patients belonged to a cohort of 650 surgical ICU patients. Significant colonization was defined as the presence of Candida spp. in three or more samples taken from one or more sites on at least two consecutive screening days. Candida spp. strains isolated from an individual patient had an identical genetic pattern, even when isolated from different body sites, and this pattern remained the same over a prolonged period of up to 140 days. No horizontal transmission could be demonstrated during the study period. Invasive candidiasis, including 8 cases of candidemia, occurred in 11/29 (38 %) patients. All patients who developed infection had previous colonization by strains with identical genetic patterns. Our intensive surveillance failed to document cross-transmission of Candida spp. between colonized and non-colonized patients.

Colonization index

The development of the CI has been viewed as a major conceptual advance in the characterization of supporting the progression from colonization to infection in surgical patients.

The Candida CI is defined as the ratio of the number of distinct non-blood body sites colonized by Candida spp. to the total number of body sites cultured [24]. With the exception of blood cultures, samples collected from body sites other than those routinely screened are also considered in the CI (Table 1). Only strains of Candida spp. with the same genetic identity are considered in calculating the CI.

Table 1.

Description of the colonization index

| Index | Definition | Formula |

|---|---|---|

| Colonization index (CI) | Ratio of the number of distinct non-blood body sites colonized by Candida spp. to the total number of body sites cultured. With the exception of blood cultures, samples collected from body sites other than those routinely screened are also considered. Only strains of Candida spp. with identical electrophoretic karyotypes are considered when calculating the CI | |

| Corrected colonization index (CCI) | Product of the CI and the ratio of the number of distinct body sites showing heavy growth (+++ from semi-quantitative culture or ≤105 in urine or gastric juice) to the total number of body sites with Candida spp. heavy growth | |

| Use of the CIa |

In patients perceived to be at risk of developing an invasive candidiasis: twice weekly surveillance culture of the following sitesb: - Oropharynx swab or tracheal secretions - Gastric fluid - Perinea swab or stool sample - Urine sample - Surgical wound swab or drained abdominal fluids - Catheter insertion sites |

aIdentification of Candida species at the genetic level has only been performed in the original study. However, different species of Candida may contribute to the burden of fungi which will eventually result in symptomatic infection. Accordingly, we suggest to consider all species of Candida identified for the calculation of the CI

bExcept for specific invasive candidiasis discussed in the section on pathophysiology of non-candidemic invasive candidiasis, Candida spp. isolated from these sites should be considered as colonization

All 29 included patients were heavily colonized with Candida spp., but with no significant difference in the reason for ICU admission and comorbidities between infected and uninfected patients. The Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) score and duration of antibiotic exposure before colonization were higher among the 11 patients who ultimately developed invasive candidiasis. In these patients, colonization preceded infection by an average of 25 days (range 6–70). The 18 patients who did not develop infection were colonized for a mean of 29 days (range 5–140). A total of 153 [5.3 ± 1 (range 3–8) per patient] distinct body sites were tested, and this number did not differ significantly between the two groups of patients.

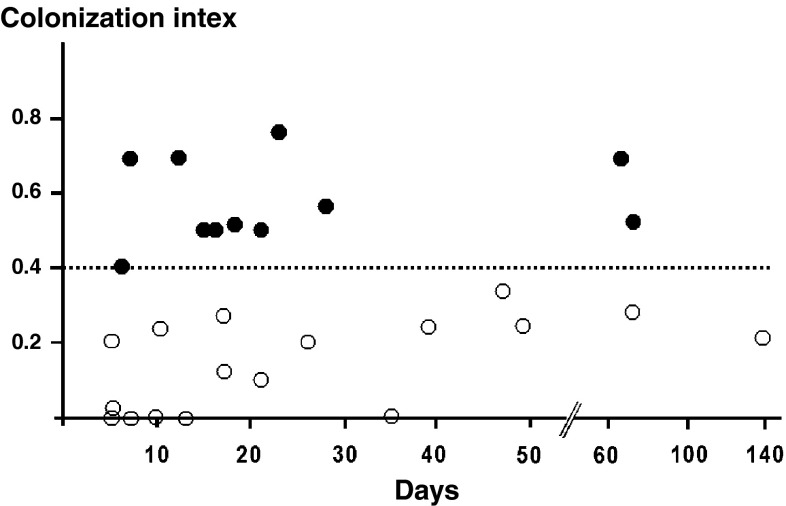

The CI was calculated daily, and the highest values obtained before invasive candidiasis development were compared with those recorded for patients who did not develop candidiasis. The average CI differed significantly between colonized and infected patients (0.47 vs. 0.70, p < 0.01). All patients who ultimately developed infection reached the threshold value of 0.5 before infection (Fig. 2). Importantly, infected patients reached the threshold CI value an average of 6 days (range 2–21) before candidiasis. All but one patient reached this threshold at least 3 days before the time of infection. The sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of the CI were determined to be 100, 69, 66, and 100 %, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Colonization index. This index is defined as the ratio of the number of distinct non-blood body sites with Candida spp. colonization to the total number of distinct body sites tested. It was recorded for each patient from the first day of colonization until discharge from the intensive care unit (uninfected patients) or severe candidiasis development (infected patients). Black circles represent patients who developed severe candidiasis, white circles represent patients who remained colonized. Reproduced with permission from Pittet et al. [24]

Corrected colonization index

In a post hoc analysis, we developed the corrected colonization index (CCI) by taking into account the amount of Candida spp. recovered by semiquantitative cultures [24]. The CCI is the product of the CI and the ratio of the number of distinct body sites showing heavy growth (+++ or at most 105 in urine or gastric juice) to the total of distinct body sites with Candida spp. growth (Table 1).

The mean CCI differed significantly between colonized (0.16) and infected (0.56) patients (p < 0.01). CCIs were less than 0.35 in all colonized patients and at least 0.4 in all infected patients (p ≤ 0.001). The sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values were all 100 %. In a multiple logistic regression analysis, only the APACHE II score [odds ratio (OR), 1.03; 95 % confidence interval, 1.01–1.05 per point; p = 0.007] and CCI (OR, 4.01; 95 % confidence interval, 2.16–7.45; p < 0.001) independently predicted the development of invasive candidiasis.

Overview of the usefulness of the colonization index

Since the publication of the paper describing the CI in 1994 in Annals of Surgery, many centers have used the CI or a methodology derived from its original description to assess the dynamics of Candida colonization in different subgroups of critically ill patients at risk of invasive candidiasis. Unfortunately, these data have not been validated in large multicenter trials.

Several studies have indirectly suggested the validity and potential usefulness of the CI, but almost exclusively in surgical patients (Table 2). This index has been used to characterize colonization dynamics [37, 38, 51–55], assess the significance of candiduria in critically ill patients [38, 56–59], and evaluate the impact of antifungal prophylaxis in subgroups of patients at risk of candidiasis [40, 46, 60–63]. At least four studies have reported the use of the CI to guide empirical antifungal treatment. Although major methodological flaws may preclude the validation of their findings, this application reduced the incidence of ICU-acquired invasive candidiasis in all four studies (Table 3) [57, 64–66].

Table 2.

Reported experience with the use of the colonization index (CI)

| Reference | Type of patient; study design | Number of patients | Number of invasive candidiasis cases | CI monitoring | Number of surveillance cultures | Main CI findings | Authors’ conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General studies (n = 7) | |||||||

| Tran et al. [51] | Cardiac surgery; prospective | 81 | 7 | Preoperatively, day 6 or at discharge | 773 (mean, 8.8/patient); 116 (16.3 %) positive |

CI ↑ in 57 % developing IC, 23 % uninfected; CI associated with female sex (45 vs. 21 %), catheter duration (13 vs. 11 days), length of ICU stay (5.7 vs. 4.9 days) CI did not change in 43 % developing IC, 72 % uninfected |

“This study showed that three epidemiological factors—duration of the intravascular catheterization and medical devices, length of stay in the SICU and the sex of the patient—were associated in elective cardiovascular surgical patients with an increase of the Candida spp. colonization index, which helps to identify high-risk patients for Candida infections” |

| Yazdanparast et al. [52] | Cardiac surgery; prospective | 131: coronary artery bypass grafting with (n = 72) and without (n = 59) extracorporeal circulation | 0 | Preoperatively, postoperatively (day not specified) | 147 | In patients requiring extracorporeal circulation, ↑ CI associated with more antibiotic use (1.50 ± 0.83 vs. 1.08 ± 0.40; different agents; p = 0.0055) | “Epidemiological data obtained from this study show that coronary artery bypass grafting with extracorporeal circulation procedure is associated with an increase in the use of antibiotics and subsequently a higher risk of Candida colonization-infection” |

| Charles et al. [37] | Mixed ICU, patients with candidemia; retrospective | 51: 20 MICU, 32 SICU (p < 0.05) | 51 | Daily for 7 days before candidemia | Not specified (mean, 3.2/patient before candidemia) |

Mean CI in 46 assessed: 0.56 ± 0.39 CI ≥ 0.50 in 21 (45.6 %) MICU 0.74 ± 0.31 vs. SICU 0.45 ± 0.40 (p = 0.01) Mean CI in survival 0.46 vs. death 0.63 (p = 0.04) Better ICU outcome associated with prior surgery [HR, 0.25 (0.09–0.67)], antifungal treatment [HR, 0.11 (0.04–0.30)], absence of neutropenia [HR, 0.10 (0.02–0.45)] |

“Candidemia occurrence is associated with a high mortality rate among critically ill patients. Differences in underlying conditions could account for the poorer outcome of the medical patients. Screening for fungal colonization could allow identification of such high-risk patients and, in turn, improve outcome” |

| Charles et al. [38] | Medical ICU, stay >7 days; prospective | 92 | 1 (septic shock with typical maculopapular rash, positive skin biopsy) | Weekly (mean, 3.2/patient) | 1,696 (mean, 18.4/patient) |

CI ≥ 0.50 in 36 (39.1 %), almost all with detectable fungal colonization on ICU admission Predictors of CI ≥ 0.5: Candida colonization at admission [OR 18.80 (5.21–67.79)], >2 days bladder catheterization [OR, 10.44 (1.61–67.85)] CI ↑ associated with days on broad-spectrum antibiotics [β = 0.01 (0.01–0.02)], hematological malignancy [β = 0.41 (0.09–0.73)], candiduria [β = 0.2 (0.09–0.31)] Empirical antifungal treatment prescribed in 14/36 (39 %) with CI ≥ 0.5, 7/56 (13 %) with CI < 0.5 (p = 0.007) |

“Candida spp. multiple-site colonization is frequently reached among the critically ill medical patients. Broad spectrum antibiotic therapy was found to promote fungal growth in patients with prior colonization. Since most of the invasive candidiasis in the ICU setting are thought to be subsequent to colonization in high-risk patients, reducing antibiotic use could be useful in preventing fungal infections” |

| Eloy et al. [53] | Mixed ICU, risk factors (antibiotics or hospital stay >8 days, neutropenia); prospective |

75: 46 MICU, 29 SICU |

4 MICU (2 respiratory tract, 2 urinary); 5 SICU (4 peritonitis, 1 urinary) | At admission, weekly | 901; 469 (52 %) positive |

Accuracy of CI > 0.5 in predicting IC in MICU: sens, 75 %; spec, 35 %; PPV, 10 %; NPV, 94 % In SICU: sens, 100 %; spec, 50 %; PPV, 29 %; NPV, 100 % |

“Serological tests failed to differentiate infected from non-infected patients. The Pittet’s CI identified infected surgical patients (Fisher exact test, 0.052), which are in the population with CI > 0.5” |

| Agvald-Ohman et al. [54] | Mixed ICU, stay >7 days; prospective | 59 | 10 | At admission, then weekly | 401; 149 (37 %) positive |

32 (54 %) received antifungals: 10 with IC [mean CI, 0.7; 8 had digestive surgery, 7 had CIs > 0.5 (<0.8 in 6)]; 22 without IC (mean CI, 0.26; 7 had digestive surgery, 9 had CIs > 0.5) 17/25 (68 %) with CIs ≥ 0.5 on day 7 received antifungals Predictors of IC: CI > 0.5 (OR, 19.1 [2.4–435]), digestive surgery [OR, 60 (2.4–infinity)] |

“High colonization index and recent extensive gastro-abdominal surgery were significantly correlated with IC. The results indicate that ICU patients exposed to extensive gastro-abdominal surgery would benefit from early antifungal prophylaxis” |

| Massou et al. [55] | Medical ICU, stay >2 days and at least one risk factor; prospective | 100 | 15 | At admission, then weekly | 816 (including 143 blood cultures) |

CI ≥ 0.5 in 53 (53 %), predicted only by corticosteroids [OR, 5.1 (1.02–25.2)] Accuracy of CI > 0.5 in predicting IC: sens, 93 %; spec, 48 %; PPV, 26 %; NPV, 98 % Only neutropenia predicted invasive candidiasis [OR, 18.3 (2.9–114)] |

“CI has the advantage to provide quantified data of the patient’s situation in relation to the colonization. But, it isn’t helpful with patients having an invasive candidiasis in medical intensive care unit” |

| Candiduria studies (n = 5) | |||||||

| Chabasse [56] | 15 mixed ICUs, one major or two minor risk factors and candiduria; prospective | 135 | 0 | At time of candiduria and/or candidemia | Not available |

Candiduria: <103, 56 (42 %); 103–104, 21 (16 %); >104, 56 (42 %) CI > 0.5 in 36/76 tested (65 % with candiduria >104, 31 % with candiduria <104; p = 0.003) |

“Quantification of candiduria could be useful to select patients at high risk for disseminated candidiasis” |

| Dubau et al. [57] | Surgical ICU, stay or antibiotics >7 days or postoperative fistula and CRP > 100 mg/ml; prospective | 89 | 1/35 empirically treated with CIs ≥ 0.5; 0 with CIs < 0.5; 22 candiduria | On inclusion, then weekly | 2,238 |

Absence of candiduria: CI = 0.3–0.47 (p = 0.008) Presence of candiduria: CI = 0.57–0.87 (p = 0.0001) |

“The presence of a candiduria was significantly associated with an increased invasive candidiasis” |

| Sellami et al. [58] | Mixed ICU, stay >3 days; prospective | 162 | 6; 56 candiduria | On inclusion, then weekly | Not available |

Candiduria: <103, 12 (21 %); 103–104, 16 (29 %); >104, 28 (50 %) Mean CI = 0.47 candiduria, 0.8 IC (n = 6) CI > 0.5 in 67 % candiduria >104 |

“Candiduria superior or equal to 104 UFC/ml associated with risk factors may predict invasive candidiasis in critically ill patients” |

| Charles et al. [38] | Medical ICU, stay > 7 days; prospective | 92 | 9 | Weekly | 1,696 (mean, 18.4/patient) | ↑ CI associated with: days on broad-spectrum antibiotics [β = 0.01 (0.01–0.02)], hematological malignancy [β = 0.41 (0.09–0.73)], candiduria [β = 0.2 (0.09–0.31)] | “Since most of the invasive candidiasis in the ICU setting are thought to be subsequent to colonization in high-risk patients, reducing antibiotic use could be useful in preventing fungal infections” |

| Ergin et al. [59] | Mixed ICU, stay >7 days; prospective | 100 | 9 (5 candidemia, 4 urinary); 42 candiduria | On inclusion, then weekly | 1,691 (mean, 17/patient) |

CI > 0.2, 42 (42 %); CI > 0.2 and <0.5, 34 (34 %); CI ≥ 0.5, 8 (8 %) Accuracy of CI ≥ 0.5 in predicting invasive candidiasis: sens, 100 %; spec, 64 %; PPV, 21 %; NPV, 100 % |

“Candida colonization and Candida colonization index may be used as useful parameters to predict invasive Candida infections” |

| Prophylaxis studies (n = 6) | |||||||

| Laverdière et al. [60] | Neutropenia (leukemia or BMT); prospective, double-blinded, randomized: prophylaxis (fluconazole, 400 mg/day orally) vs. placebo | 266 | 41: 9/135 (6.7 %) fluconazole, 32/131 (24.4 %) placebo (p < 0.001) | On randomization, at end of prophylaxis | 1,904; 458 (21 %) positive |

Colonization ↓ (39–36 %) fluconazole, ↑ (37–73 %) placebo (p < 0.0001) CI ↓ (0.18–0.16) fluconazole, ↑ (0.18–0.39) placebo (p < 0.001) Accuracy of CI ≤ 0.25 in predicting IC at baseline: sens, 39 %; spec, 82 %; PPV, 28 %; NPV, 88 % At end of prophylaxis: sens, 76 %; spec, 69 %; PPV, 69 %; NPV, 94 % |

“Fluconazole prevented and reduced fungal colonization of the alimentary tract and subsequent invasive fungal infections… In cancer patients, a colonization index ≤0.25 at the initiation of chemotherapy clearly predicts a low risk of invasive fungal infection” |

| Garbino et al. [40] | Mixed ICU, >2 days mechanical ventilation and expected continuation for ≥72 h; prospective, double-blinded randomized: prophylaxis (fluconazole, 100 mg/day iv) vs. placebo plus selective digestive decontamination (polymyxin B, neomycin, vancomycin) | 204 | 6/103 (5.8 %) fluconazole, 16/101 (16 %) placebo (p < 0.001) | Daily | Not available |

Colonization: 29/55 (53 %) fluconazole, 40/51 (78 %) placebo (p = 0.01) CI ↓ (0.26–0.13) fluconazole, ↑ (0.26–0.50) placebo (p < 0.001) Mean pre-infection CI in patients with candidemia (n = 10): 0.89 |

“…fluconazole prophylaxis in selected, high-risk critically ill patients decreases the incidence of Candida infection, in particular, candidemia” |

| Normand et al. [61] | Mixed ICU, >2 days mechanical ventilation; prospective, open-label, nystatin vs. placebo | 98 | 0 | On randomization, then every 3 days | Not available |

Colonization: 0/51 nystatin, 12/47 (25 %) placebo (p < 0.01) CI ↓ (0.1–0.05) nystatin, ↑ (0.1–0.25) placebo (p < 0.05) |

“Oral nystatin prophylaxis efficiently prevented Candida spp. colonization in ICU patients at low risk of developing invasive candidiasis” |

| Senn et al. [46] | Surgical ICU, recurrent gastrointestinal perforation/anastomotic leakage or acute necrotizing pancreatitis; prospective, non-comparative, caspofungin prophylaxis | 19 | 1 (6–8 expected in this high-risk group without prophylaxis) | On inclusion, then twice in week 1, then weekly until end of follow-up | Not available (median, 4 sites/patient screened) | CI ↓ (0.5–0.3) during prophylaxis (p = 0.03) | “Despite limitations such as the open single-center non-comparative design and the small sample size, the observations of this proof-of-concept study suggest that caspofungin may be efficacious and safe for prevention of intra-abdominal candidiasis in surgical patients with a high-risk profile” |

| Giglio et al. [62] | Surgical/trauma ICU, >2 days mechanical ventilation; prospective, randomized, open-label: prophylaxis (oral nystatin, 3 × 1 million U/day) vs. placebo | 99 | 0 | On inclusion, then every 3 days until end of follow-up (day 15) | 2,569; 746 (29 %) positive |

Overall: CI ↓ (0.12–0.0) nystatin, ↑ (0.2–0.44) placebo (p < 0.05) Colonization at entry: CI ↓ (0.1–0.0) nystatin, ↑ (0.2–0.42) placebo (p < 0.05) |

“The present trial shows that nystatin pre-emptive therapy in surgical/trauma ICU patients significantly reduces fungal colonization, even in those colonized at admission” |

| Chen et al. [63] | Mixed ICU, mechanical ventilation; prospective, randomized, open-label: prophylaxis (oral nystatin, 3 × 1 million U/day) vs. placebo | 124 | 8: 3/60 (0.5 %) nystatin, 5/64 (7.8 %) placebo (p > 0.05) | On inclusion, every 3 days until end of follow-up (day 9) | Not available; 874 positive |

CCI at day 6: 0.19 nystatin, 0.39 placebo (p < 0.05) At day 9: 0.0 nystatin, 0.45 placebo (p < 0.05) Length of ICU stay: 9.6 ± 3.5 days nystatin, 11.9 ± 6.3 days placebo (p < 0.05) |

“Nystatin might reduce the colonization by Candida albicans and was associated with shorter ICU stay” |

CRP C-reactive protein, BMT bone marrow transplant, MICU medical ICU, SICU surgical ICU, sens sensitivity, spec specificity, PPV positive predictive value, NPV negative predictive value

Table 3.

Use of the colonization index (CI) to guide the initiation of empirical antifungal treatment

| Reference | Type of patient; study design | Number of patients | Number of invasive candidiasis cases | CI monitoring | Number of surveillance cultures | Main CI findings | Authors’ conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interventional studies (n = 4) | |||||||

| Dubau et al. [57] | Surgical ICU, stay or antibiotics >7 days or -postoperative fistula and CRP >100 mg/ml; prospective, open, non-randomized: empirical antifungal treatment for CI >0.5 | 89 | 1/35 with CI > 0.5 receiving empirical antifungal treatment | On inclusion, then weekly | 2,238 |

CI > 0.5: week 1, 6 %; week 2, 25 %; week 3, 40 %; week 4, 55 %; week >4, 59 % CI ↓ rapidly after start of empirical antifungal treatment in 34/35 patients |

“A treatment was started whenever a colonization index >0.5 was associated with severe clinical or biological signs. This involved an increase of the expense of antifungal drugs. The potential benefits could not be evaluated from our study” |

| Piarroux et al. [64] | Surgical ICU, stay ≥5 days; prospective, open, non-randomized: empirical antifungal treatment for CCI > 0.4 | 478 |

Overall IC: 18 [3.8 %; 2/455 (7.0 %) in historical controls] ICU-acquired: 0 [10/455 (2.2 %) in historical controls; p < 0.001) |

On inclusion, then weekly | 6,682 |

With empirical treatment: CCI > 0.4, 96/117; CCI < 0.4 and CI ≥ 0.5, 11/66; CCI < 0.4 and CI < 0.5, 5/230 ~160 complete mycological screenings and 10 preemptive treatments needed to prevent at least one proven SICU-acquired candidiasis |

“Preemptive treatment of highly colonized patients may efficiently prevent SICU-acquired proven candidiasis. Our results demonstrate the feasibility and benefits of implementing a large systematic mycological screening of SICU patients” |

| Eren et al. [65] | Mixed ICU, inclusion criteria not specified; prospective observational, intervention not specified (antifungal treatment for CI > 0.5?) | 37 | 0 | Not specified | 191 |

26 (70 %) with C. albicans colonization CI ≥ 0.5 in 7 (5 with IgM, IgG positivity) CI < 0.5 in 19 (3/12 tested with IgM, IgG positivity) IgM, IgG found in 0/7 patients tested without colonization, out of 11 |

“…follow-up of the ICU patients in terms of C. albicans CI and IgM would be effective for the prevention of serious Candida infections” |

| Wang et al. [66] | 5 mixed ICUs, APACHE score > 10; prospective randomized: empirical antifungal treatment for CCI ≥ 0.4 (intervention group) or (control group) | 110 | Not specified | Not specified | Not available; 575 positive | Antifungal treatment for sepsis started at 0.9 ± 0.7 days in CCI ≥ 0.4, 3.8 ± 3.6 days in control (p < 0.05) | “Application of CCI may enhance the accuracy of timely preemptive treatment for invasive candidiasis and facilitate the collection of epidemiological data of Candida in critically ill patients” |

Sens sensitivity, spec specificity, PPV positive predictive value, NPV negative predictive value

Dubau et al. [57] prospectively monitored CIs weekly in 89/669 consecutive patients staying in the ICU for more than 7 days after digestive surgery who had protein C levels greater than 100 mg/l or received antibiotic treatment for more than 7 days. All patients developing a CI above 0.5 were empirically treated with antifungals until it decreased below 0.5. The proportion of patients with CIs greater than 0.5 increased from 6 to 25, 40, 55, and 59 % after 1, 2, 3, 4, and more than 4 weeks, respectively. Only one of the 35 patients with CIs greater than 0.5 who were empirically treated with antifungal medications developed candidiasis; the degree of colonization decreased rapidly in the other 34 patients.

In a before/after trial, Piarroux et al. [64] prospectively used weekly CIs and CCIs to assess the intensity of Candida spp. colonization in 478 surgical patients staying in the ICU. Patients with CCIs greater than 0.4 received empirical antifungal treatment. Compared with an historical cohort of 455 control subjects, the incidence of invasive candidiasis was lower among these patients (7.0 vs. 3.8 %; p = 0.03). Moreover, this strategy completely prevented the development of ICU-acquired invasive candidiasis. The proportions of patients treated empirically were 87 % of those with CCIs greater than 0.4 (some of them died before the CCI could be calculated), 18 % of those with CCIs less than 0.4 and CIs greater than 0.5, and 2 % of those with CCIs less than 0.4. A total of 25 % of patients received empirical antifungal treatment. The authors estimated that 160 complete mycological screenings and 10 preemptive antifungal treatments were needed to prevent one proven ICU-acquired invasive candidiasis. Despite the absence of randomization, this study is the most valuable ever performed using the CI to guide empirical antifungal treatment. However, the intense laboratory work required to perform CI in all ICU patients and the high proportion of patient treated may explain why this practice is not currently used widely among non-immunocompromised critically ill patients.

In a prospective study of 37 critically ill patients, Eren et al. [65] found a correlation between the CI and the presence of C. albicans antibodies. Among 26 patients with C. albicans colonization, immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgG were found in 5/7 (71 %) patients with CIs greater than 0.5, compared with only 3/12 (25 %) patients with CIs less than 0.5 in whom serum could be tested (total, n = 19) and 0/7 non-colonized patients in whom serum could be tested (total, n = 11) [65]. The authors stated, “in the follow-up of the patients, no candidemia developed and this was thought to be due to the preventive measures which were taken especially in ICU patients with CI > 0.5,” suggesting that empirical antifungal treatment was given to patients with CIs greater than 0.5.

Comparison of the colonization index with other predictive tools

The accuracy of the CI has been compared with that of other surrogate markers of invasive candidiasis, such as the Candida score, predictive rules, and, more recently, beta-glucan (Table 4) [44, 67–72]. In a prospective study of 89 high-risk surgical ICU patients (61 recurrent gastrointestinal tract perforation; 25 severe acute pancreatitis) in whom 29 developed a non-candidemic invasive candidiasis, Tissot el al. showed that two consecutive beta-glucan serum levels above 80 pg/ml predicted early the development of infection with a sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and a negative predictive value of 65, 78, 68 and 77 %, respectively [44]. Similarly, a previous study by Posteraro et al. [70] in a cohort of medical and surgical critically ill patients staying more than 5 days and developing a severe sepsis, in whom beta-glucan was higher than 80 pg/ml, showed a sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and a negative predictive value of 93, 94, 72, and 99 %, respectively for the early detection of invasive candidiasis (16 episodes, including 13 candidemia). Overall, the accuracy of CI is lower than other methods for the early detection of patients at higher risk of infection. Nevertheless, the usefulness of beta-glucan to guide empirical antifungal treatment remains to be determined.

Table 4.

Comparison of the colonization index (CI) with other markers for the prediction of invasive candidiasis

| References | Type of patient; study design | Number of patients | Number of invasive candidiasis | CI monitoring | Performance of CI | Performance of comparators | Authors’ conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leon et al. [67] | 36 mixed ICUs, stay ≥7 days; prospective, observational cohort | 1,107 | 58; 18/240 in whom BG could be performed | At inclusion, then weekly (4,198 cultures) |

892 with Candida spp. colonization or invasive candidiasis Development of invasive candidiasis: CI < 0.5, 16/411 (3.9 %); CI ≥ 0.5, 42/481 (8.7 %) Sens, 72 %; spec, 47 %; PPV, 9 %; NPV, 96 %; AUC, 0.633 20.8 needed to treat to avoid one episode of invasive candidiasis |

892 with Candida spp. colonization or invasive candidiasis Development of invasive candidiasis: Candida score <3, 13/565 (2.3 %); Candida score ≥3, 45/327 (13.8 %) Sens, 78 %; spec, 66 %; PPV, 14 %; NPV, 98 %; AUC, 0.774 8.7 needed to treat to avoid one episode of invasive candidiasis |

“In this cohort of colonized patients staying >7 days, with a CS <3 and not receiving antifungal treatment, the rate of IC was <5 %. Therefore, IC is highly improbable if a Candida-colonized non-neutropenic critically ill patient has a Candida score <0.3” |

| Ellis et al. [68] | Hematological patients with febrile neutropenia and >3 days broad-spectrum antibiotics; prospective, usefulness of serial analysis for mannans/anti-mannans, β-glucans | 86 | 12 (14 %) | Twice a week |

CI ≥ 0.5 in 52/86 (60 %), 8/9 (89 %) IC Accuracy not determined |

Mannans/anti-mannans (33 patients (2 consecutive positive tests): sens, 73 %; spec, 80 %; PPV, 0.36; NPV, 0.95 Positive correlation of invasive candidiasis with β-glucans (r = 0.28, p = 0.01) |

“Serial assays for mannans and anti-mannans in patients at risk for invasive candidiasis may usefully contribute to the management of such patients” |

| Caggiano et al. [69] | Neurological ICU, stay ≥7 days; prospective, link between colonization and invasive candidiasis | 51 | 3 candidemia | At admission, then every 3 days (to day 15) |

Colonization: 76 % at study entry, 92 % on day 15 CI ≥ 0.5: 16.6 % at study entry, 75 % on day 15 (all IC) CCI: 0.34 at study entry, 0.60 on day 15 |

No mannan/anti-mannan detected in patients without candidemia Mannans: sens, 66.6 %; spec, 100 % Anti-mannans: sens, 100 %; spec, 100 % |

“Thus, our experience suggests that monitoring CI could be helpful in identifying patients at risk of invasive fungal infection. In addition, complementing this with anti-Candida antibodies detection in immunocompetent patients with CI ≥ 0.5 increases the positive predictivity for infection allowing an early diagnosis of candidemia” |

| Posteraro et al. [70] | Mixed ICU, stay ≥5 days; prospective, single-center, observational: diagnostic value of BG assay, Candida score, CI | 95 | 16 (14 invasive candidiasis) | At entry, day 3, and then weekly |

CI ≥ 0.5: overall, 35 %; IC, 56 %; no IC, 30 % (p = 0.04) Sens, 64 %; spec, 70 %; PPV, 27 %; NPV, 92 %; AUC, 0.63 (0.57–0.79) |

Candida score ≥3: overall, 22 %; IC, 75 %; no IC, 11 % (p < 0.001). Sens, 86 %; spec, 87 %; PPV, 57 %; NPV, 97 %; AUC, 0.80 (0.69–0.92) BG positivity: overall, 21 %; IC, 94 %; no IC, 6 % (p < 0.001). Sens, 94 %; spec, 94 %; PPV, 75 %; NPV, 99 %; AUC, 0.98 (0.92–1.00) Candida score ≥3 and BG positivity: sens, 100 %; spec, 84 %; PPV, 52 %; NPV, 100 % |

“A single-point BG assay based on a blood sample drawn at the sepsis onset, alone or in combination with Candida score, may guide the decision to start antifungal therapy early in patients at risk for Candida infection” |

|

Peman et al. [71] |

6 mixed ICU, high risk of invasive candidiasisa; prospective, usefulness of CAGTA | 53 | 0 | Not specified | CCI ≥ 0.4: 23/53 (43 %) at study entry, 41/53 (77 %) at end of study | CAGTA positivity: 22/53 (42 %) at study entry, 47/53 (90 %) at end of study | “This study identified previous surgery as the principal clinical factor associated with CAGTA-positive results (serologically proven candidiasis) and emphasises the utility of this promising technique, which was not influenced by high Candida colonization or antifungal treatment” |

| Hall et al. [72] | Mixed ICU, severe acute pancreatitis; retrospective, diagnostic value of BG assay, Candida score, CI | 101 | 18 (5 died) | Not specified |

Colonization: 16/18 (89 %) IC, 37/83 (45 %) no IC (p = 0.0006). Colonization for IC: OR, 4.33 (1.07–17.5); p = 0.04 CI ≥ 0.5: sens, 67 %; spec, 79 %; PPV, 43 %; NPV, 91 %; AUC, 0.79 (0.69–0.87) |

Candida score: sens, 23 %; spec, 85 %; PPV, 39 %; NPV, 72 %; AUC, 0.62 (0.52–0.71) Predictive ruleb: sens, 61 %; spec, 49 %; PPV, 21 %; NPV, 85 %; AUC, 0.59 (0.49–0.69) |

“In this study the Candida colonisation index score was the most accurate and discriminative test at identifying which patients with severe acute pancreatitis are at risk of developing candidal infection. However its low sensitivity may limit its clinical usefulness” |

| Tissot et al. [44] | Surgical ICU, recurrent gastrointestinal perforation/anastomotic leakage or acute necrotizing pancreatitis; prospective, accuracy of BG antigenemia for diagnosis of intra-abdominal candidiasis | 89 | 2 | On admission, then twice a week |

CI ≥ 0.5: sens, 26 %; spec, 76 %; PPV, 35 %; NPV, 67 %; AUC, 0.67 CCI ≥ 0.4: sens, 14 %; spec, 77 %; PPV, 23 %; NPV, 65 %; AUC, 0.43 |

BG > 80 pg/ml (2×): sens, 66 %; spec, 83 %; PPV, 73 %; NPV, 78 %; AUC, 0.79 Candida score ≥3: sens, 86 %; spec, 50 %; PPV, 54 %; NPV, 84 %; AUC, 0.61 |

“BG antigenemia is superior to Candida score and colonization indexes and anticipates diagnosis of blood culture-negative intra-abdominal candidiasis” |

Sens sensitivity, Spec specificity, PPV positive predictive value, NPV negative predictive value, AUC area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, CAGTA Candida albicans germ tube antibody

a(1) Acute pancreatitis with >7 days evolution, (2) prolonged (>14 days) ICU stay and ≥3 risk factors (diabetes mellitus, extrarenal depuration, parenteral nutrition, >7 days broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, major abdominal surgery), (3) liver transplantation, (4) neutropenia or bone marrow transplantation, or (5) high CAGTA

b[73]

Three industry-sponsored studies failed to demonstrate the clinical usefulness of predictive rules combining various risk factors. A predictive rule was used in a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial comparing caspofungin vs. placebo as antifungal prophylaxis or preemptive treatment in 222 critically ill patients [73]. The rule combined ICU stay for at least 3 days, mechanical ventilation, exposure to antibiotics, the presence of a central line, together with at least one additional risk factor among the following: parenteral nutrition, dialysis, surgery, pancreatitis, systemic steroids, or other immune suppressive agents. The incidence of invasive candidiasis was 16.7 % (14/84) vs. 9.8 % (10/102) in patients receiving placebo and caspofungin, respectively (p = 0.14). When baseline infections were included, it was 30.4 % (31/102) and 18.8 % (22/117), for patients receiving preemptive placebo and caspofungin, respectively (p = 0.04). Safety, length of ICU stay, antifungal use, and mortality did not differ. The authors concluded that caspofungin prophylaxis was safe with a non-significant trend to reduce invasive candidiasis, and that the preemptive therapy approach deserves further study. Two recent and currently unpublished studies attempt to use clinical predictive rules to guide empirical antifungal treatment. The first, entitled “Pilot Feasibility Study With Patients Who at High Risk For Developing Invasive Candidiasis in a Critical Care Setting (MK-0991-067 AM1” (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01045798) and conducted by the Mycoses Study Group, was terminated because of a low recruitment rate after the inclusion of only 15 patients and generation of uninterpretable data. Preliminary results of the second study, entitled “A Study to Evaluate Pre-emptive Treatment for Invasive Candidiasis in High Risk Surgical Subjects (INTENSE)” (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01122368), showed a high proportion of invasive candidiasis at study entry; independent experts considered, however, that the majority of salvage antifungal treatments were unjustified. Globally, the proportion of invasive candidiasis developing in the group receiving preemptive antifungal treatment was not different from that of the group receiving placebo, but the number of patients excluded from the analysis resulted in an underpowered analysis.

These outcomes illustrate a well-known paradigm of accuracy. The use of the most sensitive test potentially increases the number of patients who are uselessly treated empirically. In contrast, the use of the most specific test potentially increases the number of patients who do not receive empirical antifungal treatment and in whom late treatment could be associated with a worse outcome.

An ongoing prospective multicenter, double blind, randomized-controlled French trial (EMPIRICUS) is currently recruiting critically ill patients at risk of invasive candidiasis. Patients mechanically ventilated for more than 4 days with sepsis of unknown origin and with at least one extra-digestive fungal colonization site and multiple organ failure are eligible for randomization to receive empirical micafungin or a placebo. This study includes prospective determination of the CI among its secondary endpoints and may help to develop guidelines for treating non-immunocompromised patients with fungal colonization multiple organ failure and sepsis of unknown origin [74].

The CI and other predictive tools (the Candida score and predictive rules) have been specifically developed by using their positive predictive value for the early identification of high-risk patients who will develop invasive candidiasis. Nevertheless, it is relevant to note that the negative predictive values of the CI and all other surrogate markers of invasive candidiasis are much higher than their positive predictive values [21]. Among them, only the negative predictive value of the Candida score has been validated in a multicenter prospective clinical trial [75].

Advantages and pitfalls of the use of colonization index

To summarize the data reviewed on the use of the CI, its main advantages are that it has been successfully used to characterize colonization dynamics, assess the significance of candiduria, and to evaluate the impact of antifungal prophylaxis. A low CI has a high negative predictive value for the further development of invasive candidiasis. Among the pitfalls, it should be emphasized that it is work-intensive with a limited bedside practicability, that only limited data are available for nonsurgical patients, and its cost-effectiveness and usefulness for the management of critically ill patients remain to be proven in large prospective clinical trials.

Further perspectives

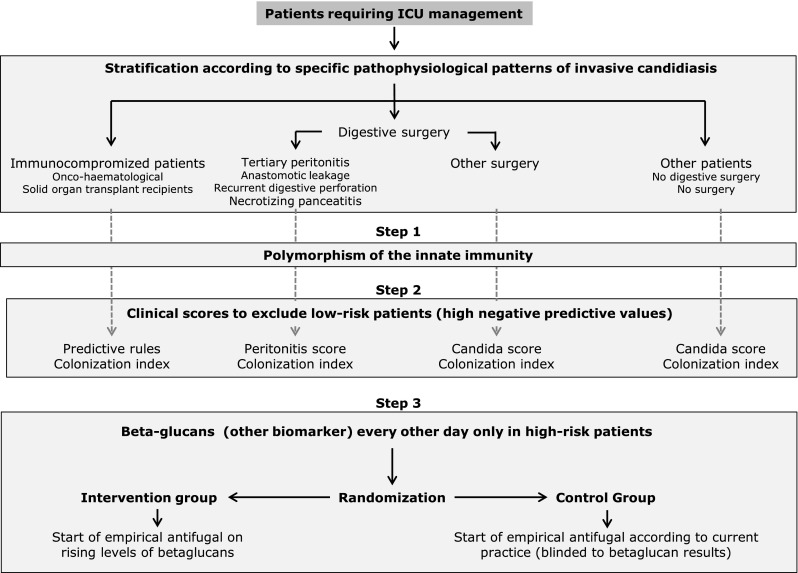

These observations may pave the way for a new paradigm in the research agenda of the early diagnosis of invasive candidiasis and take advantage of the disease pathophysiology characterized by a 7–10-day delay between exposure to risk factors and infection. We propose a stepwise approach to optimize the accuracy of the CI and other clinical tools (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Proposed study designs to select high-risk patients who would truly benefit from early empirical antifungal treatment. First, patients should be stratified according to pathophysiological characteristics specific to invasive candidiasis (i.e., immunocompromised individuals, after digestive surgery, other critically ill patients). The three-step approach: In a first optional step, increased intrinsic risk of invasive candidiasis is identified by specific genetic polymorphisms related to innate immunity. In the second step, patients at low objective risk of invasive candidiasis are ruled out by using the high negative predictive values of current risk-assessment strategies (CI, Candida score, peritonitis score, predictive rule). In the third step, empirical antifungal treatment is started early in high-risk patients identified by increased biomarkers values, such as beta-glucan performed only in patients retained by who met criteria outlined in previous steps. A simplified approach restricted to steps two and three may be also of potential interest

Provided that preliminary results can be confirmed in larger cohorts of patients [76], preliminary stratification according to specific genetic polymorphisms could be used as a preliminary step to increase the accuracy of subsequent steps. The second step is to take advantage of the high negative predictive values of the CI, Candida score, and/or predictive rules. This strategy will reduce the currently large proportion of useless antifungal treatments, frequently started for nonobjective emotional reasons. The enhanced intrinsic risk of invasive candidiasis in patients with increased risk identified after this second step may further improve the accuracy of biomarkers, such as mannan/anti-mannan antibodies and/or β-glucan, applied in the third step. This approach should enhance the ability to identify patients who will truly benefit from early antifungal treatment and reduce unnecessary overexposure to antifungal agents in patients with a documented limited risk of infection.

Moreover, the high negative predictive value of the predictive tools (CI, Candida score, and predictive rules) for the further development of an invasive candidiasis may allow one to stop empirical antifungal treatment possibly prescribed before evaluating the patient according to the proposed stepwise approach.

Conclusion

The development of the CI has enabled better appreciation of the dynamics of Candida colonization in patients at high risk of invasive candidiasis. It can still be used, as it is in many institutions, for the early detection of patients at high risk of invasive candidiasis and to guide empirical antifungal treatment. Continued development and execution of clinical trials in this difficult field are important. Until further progress can be achieved with new clinical studies of specific biomarkers involving larger patient cohorts, 20 years after its description, the CI remains one of the best methods of characterizing the dynamics of Candida colonization and identifying patients at very low or increasing risk of invasive candidiasis.

Acknowledgments

PE received research grants and/or educational grants and/or speaker’s honoraria and/or consultant’s honoraria from (in alphabetic order): Astellas, Merck, Sharp & Dohme-Chibret, and Pfizer.

Conflicts of interest

DP declares no disclosure of potential conflicts of interest regarding their contribution to this study.

Contributor Information

Philippe Eggimann, Email: philippe.eggimann@chuv.ch.

Didier Pittet, Phone: +41 22 372 9844, Email: didier.pittet@hcuge.ch.

References

- 1.Eggimann P, Garbino J, Pittet D. Epidemiology of Candida species infections in critically ill non-immunosuppressed patients. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:685–702. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00801-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vincent JL, Rello J, Marshall J, Silva E, Anzueto A, Martin CD, Moreno R, Lipman J, Gomersall C, Sakr Y, Reinhart K, EPIC II Group of Investigators International study of the prevalence and outcomes of infection in intensive care units. JAMA. 2009;302:2323–2329. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfaller M, Neofytos D, Diekema D, Azie N, Meier-Kriesche HU, Quan SP, Horn D. Epidemiology and outcomes of candidemia in 3648 patients: data from the Prospective Antifungal Therapy (PATH Alliance®) registry, 2004-2008. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;74:323–331. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guery BP, Arendrup MC, Auzinger G, Azoulay E, Borges Sa M, Johnson EM, Muller E, Putensen C, Rotstein C, Sganga G, Venditti M, Zaragoza Crespo R, Kullberg BJ. Management of invasive candidiasis and candidemia in adult non-neutropenic intensive care unit patients: part I. Epidemiology and diagnosis. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:55–62. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1338-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kett DH, Azoulay E, Echeverria PM, Vincent JL, Extended Prevalence of Infection in ICUSGoI Candida bloodstream infections in intensive care units: analysis of the extended prevalence of infection in intensive care unit study. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:665–670. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318206c1ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marchetti O, Bille J, Fluckiger U, Eggimann P, Ruef C, Garbino J, Calandra T, Glauser MP, Tauber MG, Pittet D, Fungal Infection Network of S Epidemiology of candidemia in Swiss tertiary care hospitals: secular trends, 1991–2000. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:311–320. doi: 10.1086/380637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eggimann P, Bille J, Marchetti O. Diagnosis of invasive candidiasis in the ICU. Ann Intensive Care. 2011;1:37. doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-1-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bassetti M, Marchetti M, Chakrabarti A, Colizza S, Garnacho-Montero J, Kett DH, Munoz P, Cristini F, Andoniadou A, Viale P, Rocca GD, Roilides E, Sganga G, Walsh TJ, Tascini C, Tumbarello M, Menichetti F, Righi E, Eckmann C, Viscoli C, Shorr AF, Leroy O, Petrikos G, De Rosa FG. A research agenda on the management of intra-abdominal candidiasis: results from a consensus of multinational experts. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:2092–2106. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-3109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gudlaugsson O, Gillespie S, Lee K, Berg JV, Hu J, Messer S, Herwaldt L, Pfaller M, Diekema D. Attributable mortality of nosocomial candidemia, revisited. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:1172–1177. doi: 10.1086/378745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zaoutis TE, Argon J, Chu J, Berlin JA, Walsh TJ, Feudtner C. The epidemiology and attributable outcomes of candidemia in adults and children hospitalized in the United States: a propensity analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1232–1239. doi: 10.1086/496922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prowle JR, Echeverri JE, Ligabo EV, Sherry N, Taori GC, Crozier TM, Hart GK, Korman TM, Mayall BC, Johnson PD, Bellomo R. Acquired bloodstream infection in the intensive care unit: incidence and attributable mortality. Crit Care. 2011;15:R100. doi: 10.1186/cc10114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morrell M, Fraser VJ, Kollef MH. Delaying the empiric treatment of candida bloodstream infection until positive blood culture results are obtained: a potential risk factor for hospital mortality. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:3640–3645. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.9.3640-3645.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garey KW, Rege M, Pai MP, Mingo DE, Suda KJ, Turpin RS, Bearden DT. Time to initiation of fluconazole therapy impacts mortality in patients with candidemia: a multi-institutional study. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:25–31. doi: 10.1086/504810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azoulay E, Dupont H, Tabah A, Lortholary O, Stahl JP, Francais A, Martin C, Guidet B, Timsit JF. Systemic antifungal therapy in critically ill patients without invasive fungal infection. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:813–822. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318236f297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sipsas NV, Lewis RE, Tarrand J, Hachem R, Rolston KV, Raad II, Kontoyiannis DP. Candidemia in patients with hematologic malignancies in the era of new antifungal agents (2001–2007): stable incidence but changing epidemiology of a still frequently lethal infection. Cancer. 2009;115:4745–4752. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lortholary O, Desnos-Ollivier M, Sitbon K, Fontanet A, Bretagne S, Dromer F, French Mycosis Study G Recent exposure to caspofungin or fluconazole influences the epidemiology of candidemia: a prospective multicenter study involving 2,441 patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:532–538. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01128-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes D, Benjamin DK, Jr, Calandra TF, Edwards JE, Jr, Filler SG, Fisher JF, Kullberg BJ, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Reboli AC, Rex JH, Walsh TJ, Sobel JD, Infectious Diseases Society of A Clinical practice guidelines for the management of candidiasis: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:503–535. doi: 10.1086/596757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cornely OA, Bassetti M, Calandra T, Garbino J, Kullberg BJ, Lortholary O, Meersseman W, Akova M, Arendrup MC, Arikan-Akdagli S, Bille J, Castagnola E, Cuenca-Estrella M, Donnelly JP, Groll AH, Herbrecht R, Hope WW, Jensen HE, Lass-Florl C, Petrikkos G, Richardson MD, Roilides E, Verweij PE, Viscoli C, Ullmann AJ, Group EFIS ESCMID guideline for the diagnosis and management of Candida diseases 2012: non-neutropenic adult patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(Suppl 7):19–37. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eggimann P, Garbino J, Pittet D. Management of Candida species infections in critically ill patients. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:772–785. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00831-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Playford EG, Eggimann P, Calandra T. Antifungals in the ICU. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008;21:610–619. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3283177967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eggimann P, Ostrosky-Zeichner L. Early antifungal intervention strategies in ICU patients. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2010;16:465–469. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32833e0487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montravers P, Dupont H, Eggimann P. Intra-abdominal candidiasis: the guidelines-forgotten non-candidemic invasive candidiasis. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:2226–2230. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-3134-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pittet D, Monod M, Filthuth I, Frenk E, Suter PM, Auckenthaler R. Contour-clamped homogeneous electric field gel electrophoresis as a powerful epidemiologic tool in yeast infections. Am J Med. 1991;91:256S–263S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90378-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pittet D, Monod M, Suter PM, Frenk E, Auckenthaler R. Candida colonization and subsequent infections in critically ill surgical patients. Ann Surg. 1994;220:751–758. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199412000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van de Veerdonk FL, Kullberg BJ, Netea MG. Pathogenesis of invasive candidiasis. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2010;16:453–459. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32833e046e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Magill SS, Swoboda SM, Shields CE, Colantuoni EA, Fothergill AW, Merz WG, Lipsett PA, Hendrix CW. The epidemiology of Candida colonization and invasive candidiasis in a surgical intensive care unit where fluconazole prophylaxis is utilized: follow-up to a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2009;249:657–665. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31819ed914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khan ZU, Chandy R, Metwali KE. Candida albicans strain carriage in patients and nursing staff of an intensive care unit: a study of morphotypes and resistotypes. Mycoses. 2003;46:479–486. doi: 10.1046/j.0933-7407.2003.00929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marco F, Lockhart SR, Pfaller MA, Pujol C, Rangel-Frausto MS, Wiblin T, Blumberg HM, Edwards JE, Jarvis W, Saiman L, Patterson JE, Rinaldi MG, Wenzel RP, Soll DR. Elucidating the origins of nosocomial infections with Candida albicans by DNA fingerprinting with the complex probe Ca3. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2817–2828. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.9.2817-2828.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nucci M, Anaissie E. Revisiting the source of candidemia: skin or gut? Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1959–1967. doi: 10.1086/323759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Filler SG. Insights from human studies into the host defense against candidiasis. Cytokine. 2012;58:129–132. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charlier C, Hart E, Lefort A, Ribaud P, Dromer F, Denning DW, Lortholary O. Fluconazole for the management of invasive candidiasis: where do we stand after 15 years? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;57:384–410. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maertens J, Marchetti O, Herbrecht R, Cornely OA, Fluckiger U, Frere P, Gachot B, Heinz WJ, Lass-Florl C, Ribaud P, Thiebaut A, Cordonnier C, Third European Conference on Infections in Leukemia European guidelines for antifungal management in leukemia and hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: summary of the ECIL 3–2009 update. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2011;46:709–718. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dannaoui E, Desnos-Ollivier M, Garcia-Hermoso D, Grenouillet F, Cassaing S, Baixench MT, Bretagne S, Dromer F, Lortholary O, French Mycoses Study G Candida spp. with acquired echinocandin resistance, France, 2004–2010. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:86–90. doi: 10.3201/eid1801.110556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pacholczyk M, Lagiewska B, Lisik W, Wasiak D, Chmura A. Invasive fungal infections following liver transplantation—risk factors, incidence and outcome. Ann Transplant. 2011;16:14–16. doi: 10.12659/aot.881989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schaenman JM. Is universal antifungal prophylaxis mandatory in lung transplant patients? Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2013;26:317–325. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3283630e67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toth A, Csonka K, Jacobs C, Vagvolgyi C, Nosanchuk JD, Netea MG, Gacser A. Candida albicans and Candida parapsilosis induce different T-cell responses in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:690–698. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Charles PE, Doise JM, Quenot JP, Aube H, Dalle F, Chavanet P, Milesi N, Aho LS, Portier H, Blettery B. Candidemia in critically ill patients: difference of outcome between medical and surgical patients. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:2162–2169. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-2002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Charles PE, Dalle F, Aube H, Doise JM, Quenot JP, Aho LS, Chavanet P, Blettery B. Candida spp. colonization significance in critically ill medical patients: a prospective study. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:393–400. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2571-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eggimann P, Calandra T, Fluckiger U, Bille J, Garbino J, Glauser MP, Marchetti O, Ruef C, Tauber M, Pittet D, Fungal Infection Network of Switzerland Invasive candidiasis: comparison of management choices by infectious disease and critical care specialists. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:1514–1521. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2809-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garbino J, Lew DP, Romand JA, Hugonnet S, Auckenthaler R, Pittet D. Prevention of severe Candida infections in nonneutropenic, high-risk, critically ill patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in patients treated by selective digestive decontamination. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:1708–1717. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1540-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vincent JL, Anaissie E, Bruining H, Demajo W, el-Ebiary M, Haber J, Hiramatsu Y, Nitenberg G, Nystrom PO, Pittet D, Rogers T, Sandven P, Sganga G, Schaller MD, Solomkin J. Epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment of systemic Candida infection in surgical patients under intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 1998;24:206–216. doi: 10.1007/s001340050552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Solomkin JS, Flohr AB, Quie PG, Simmons RL. The role of Candida in intraperitoneal infections. Surgery. 1980;88:524–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Calandra T, Bille J, Schneider R, Mosimann F, Francioli P. Clinical significance of Candida isolated from peritoneum in surgical patients. Lancet. 1989;2:1437–1440. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(89)92043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tissot F, Lamoth F, Hauser PM, Orasch C, Fluckiger U, Siegemund M, Zimmerli S, Calandra T, Bille J, Eggimann P, Marchetti O, Fungal Infection Network of Switzerland (FUNGINOS) Beta-glucan antigenemia anticipates diagnosis of blood culture-negative intraabdominal candidiasis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:1100–1109. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201211-2069OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eggimann P, Francioli P, Bille J, Schneider R, Wu MM, Chapuis G, Chiolero R, Pannatier A, Schilling J, Geroulanos S, Glauser MP, Calandra T. Fluconazole prophylaxis prevents intra-abdominal candidiasis in high-risk surgical patients. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1066–1072. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199906000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Senn L, Eggimann P, Ksontini R, Pascual A, Demartines N, Bille J, Calandra T, Marchetti O. Caspofungin for prevention of intra-abdominal candidiasis in high-risk surgical patients. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:903–908. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldstein E, Hoeprich PD. Problems in the diagnosis and treatment of systemic candidiasis. J Infect Dis. 1972;125:190–193. doi: 10.1093/infdis/125.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klein JJ, Watanakunakorn C. Hospital-acquired fungemia. Its natural course and clinical significance. Am J Med. 1979;67:51–58. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(79)90073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Solomkin JS, Flohr AM, Simmons RL. Indications for therapy for fungemia in postoperative patients. Arch Surg. 1982;117:1272–1275. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1982.01380340008003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vazquez JA, Sanchez V, Dmuchowski C, Dembry LM, Sobel JD, Zervos MJ. Nosocomial acquisition of Candida albicans: an epidemiologic study. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:195–201. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.1.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tran LT, Auger P, Marchand R, Carrier M, Pelletier C. Epidemiological study of Candida spp. colonization in cardiovascular surgical patients. Mycoses. 1997;40:169–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1997.tb00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yazdanparast K, Auger P, Marchand R, Carrier M, Cartier R. Predictive value of Candida colonization index in 131 patients undergoing two different cardiovascular surgical procedures. J Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;42:339–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eloy O, Marque S, Mourvilliers B, Pina P, Allouch PY, Pangon B, Bedos JP, Ghnassia JC (2006) Contribution of the Pittet’s index, antigen assay, IgM, and total antibodies in the diagnosis of invasive candidiasis in intensive care unit. J Mycol Med 16:113–118

- 54.Agvald-Ohman C, Klingspor L, Hjelmqvist H, Edlund C. Invasive candidiasis in long-term patients at a multidisciplinary intensive care unit: candida colonization index, risk factors, treatment and outcome. Scand J Infect Dis. 2008;40:145–153. doi: 10.1080/00365540701534509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Massou S, Ahid S, Azendour H, Bensghir M, Mounir K, Iken M, Lmimouni BE, Balkhi H, Drissi Kamili N, Haimeur C. Systemic candidiasis in medical intensive care unit: analysis of risk factors and the contribution of colonization index. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2013;61:108–112. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chabasse D. Yeast count in urine. Review of the literature and preliminary results of a multicenter prospective study carried out in 15 hospital centers. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2001;20:400–406. doi: 10.1016/S0750-7658(01)00376-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dubau B, Triboulet C, Winnock S. Use of the colonization index. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2001;20:418–420. doi: 10.1016/S0750-7658(01)00375-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sellami A, Sellami H, Makni F, Bahloul M, Cheikh-Rouhou F, Bouaziz M, Ayadi A. Candiduria in intensive care unit: significance and value of yeast numeration in urine. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2006;25:584–588. doi: 10.1016/j.annfar.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ergin F, Eren Tulek N, Yetkin MA, Bulut C, Oral B, Tuncer Ertem G. Evaluation of Candida colonization in intensive care unit patients and the use of Candida colonization index. Mikrobiyol Bul. 2013;47:305–317. doi: 10.5578/mb.4764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Laverdiere M, Rotstein C, Bow EJ, Roberts RS, Ioannou S, Carr D, Moghaddam N. Impact of fluconazole prophylaxis on fungal colonization and infection rates in neutropenic patients. The Canadian Fluconazole Study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;46:1001–1008. doi: 10.1093/jac/46.6.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Normand S, Francois B, Darde ML, Bouteille B, Bonnivard M, Preux PM, Gastinne H, Vignon P. Oral nystatin prophylaxis of Candida spp. colonization in ventilated critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:1508–1513. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2807-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Giglio M, Caggiano G, Dalfino L, Brienza N, Alicino I, Sgobio A, Favale A, Coretti C, Montagna MT, Bruno F, Puntillo F. Oral nystatin prophylaxis in surgical/trauma ICU patients: a randomised clinical trial. Crit Care. 2012;16:R57. doi: 10.1186/cc11300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen Z, Yang CL, He HW, Zeng J. The clinical research of nystatin in prevention of invasive fungal infections in patients on mechanical ventilation in intensive care unit. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2013;25:475–478. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.2095-4352.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Piarroux R, Grenouillet F, Balvay P, Tran V, Blasco G, Millon L, Boillot A. Assessment of preemptive treatment to prevent severe candidiasis in critically ill surgical patients. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:2443–2449. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000147726.62304.7F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Eren A, Aydogan S, Kalkanci A, Kustimur S. The relationship between Candida albicans colonization indices and the presence of specific antibodies in non-neutropenic intensive care unit patients. Mikrobiyol Bul. 2007;41:253–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang DH, Gao XJ, Wei LQ, Xia R, Sun L, Li Q, Peng M, Qin YZ. The preemptive treatment of invasive Candida infection with reference of corrected colonization index in critically ill patients: a multicenter, prospective, randomized controlled clinical study. Zhongguo Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2009;21:525–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Leon C, Ruiz-Santana S, Saavedra P, Galvan B, Blanco A, Castro C, Balasini C, Utande-Vazquez A, Gonzalez de Molina FJ, Blasco-Navalproto MA, Lopez MJ, Charles PE, Martin E, Hernandez-Viera MA, Cava Study G Usefulness of the “Candida score” for discriminating between Candida colonization and invasive candidiasis in non-neutropenic critically ill patients: a prospective multicenter study. Critical Care Med. 2009;37:1624–1633. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819daa14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ellis M, Al-Ramadi B, Bernsen R, Kristensen J, Alizadeh H, Hedstrom U. Prospective evaluation of mannan and anti-mannan antibodies for diagnosis of invasive Candida infections in patients with neutropenic fever. J Med Microbiol. 2009;58:606–615. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.006452-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Caggiano G, Puntillo F, Coretti C, Giglio M, Alicino I, Manca F, Bruno F, Montagna MT. Candida colonization index in patients admitted to an ICU. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12:7038–7047. doi: 10.3390/ijms12107038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Posteraro B, De Pascale G, Tumbarello M, Torelli R, Pennisi MA, Bello G, Maviglia R, Fadda G, Sanguinetti M, Antonelli M. Early diagnosis of candidemia in intensive care unit patients with sepsis: a prospective comparison of (1→3)-beta-d-glucan assay, Candida score, and colonization index. Crit Care. 2011;15:R249. doi: 10.1186/cc10507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Peman J, Zaragoza R, Quindos G, Alkorta M, Cuetara MS, Camarena JJ, Ramirez P, Gimenez MJ, Martin-Mazuelos E, Linares-Sicilia MJ, Ponton J, Study group Candida albicans Germ Tube Antibody Detection in Critically Ill Patients Clinical factors associated with a Candida albicans germ tube antibody positive test in intensive care unit patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hall AM, Poole LA, Renton B, Wozniak A, Fisher M, Neal T, Halloran CM, Cox T, Hampshire PA. Prediction of invasive candidal infection in critically ill patients with severe acute pancreatitis. Crit Care. 2013;17:R49. doi: 10.1186/cc12569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Shoham S, Vazquez J, Reboli A, Betts R, Barron MA, Schuster M, Judson MA, Revankar SG, Caeiro JP, Mangino JE, Mushatt D, Bedimo R, Freifeld A, Nguyen MH, Kauffman CA, Dismukes WE, Westfall AO, Deerman JB, Wood C, Sobel JD, Pappas PG (2014) MSG-01: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of caspofungin prophylaxis followed by preemptive therapy for invasive candidiasis in high-risk adults in the critical care setting. Clin Infect Dis 58:1219–1226 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 74.Timsit JF, Azoulay E, Cornet M, Gangneux JP, Jullien V, Vesin A, Schir E, Wolff M. EMPIRICUS micafungin versus placebo during nosocomial sepsis in Candida multi-colonized ICU patients with multiple organ failures: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:399. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Charles PE, Castro C, Ruiz-Santana S, Leon C, Saavedra P, Martin E. Serum procalcitonin levels in critically ill patients colonized with Candida spp: new clues for the early recognition of invasive candidiasis? Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:2146–2150. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1623-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]