Abstract

Although the education-health relationship is well documented, pathways through which education influences health are not well understood. This study uses data from a 2003-4 cross sectional supplemental survey of respondents to the longitudinal Health and Retirement Study (HRS) who had been diagnosed with diabetes mellitus to assess effects of education on health and mechanisms underlying the relationship. The supplemental survey provides rich detail on use of personal health care services (e.g., adherence to guidelines for diabetes care) and personal attributes which are plausibly largely time invariant and systematically related to years of schooling completed, including time preference, self-control, and self-confidence. Educational attainment, as measured by years of schooling completed, is systematically and positively related to time to onset of diabetes, and conditional on having been diagnosed with this disease on health outcomes, variables related to efficiency in health production, as well as use of diabetes specialists. However, the marginal effects of increasing educational attainment by a year are uniformly small. Accounting for other factors, including child health and child socioeconomic status which could affect years of schooling completed and adult health, adult cognition, income, and health insurance, and personal attributes from the supplemental survey, marginal effects of educational attainment tend to be lower than when these other factors are not included in the analysis, but they tend to remain statistically significant at conventional levels.

Keywords: Education, health Production, diabetes mellitus, cognition, health information

I. Introduction

The notion that there is a relationship between years of schooling and health has a long history in economics (Schultz 1962). Yet although empirical analysis of the effect of educational attainment on health is an active research area, much remains to be learned about the relationship. This study uses unique data from a 2003-4 survey of respondents to the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) diagnosed with diabetes mellitus (DM) to assess pathways through which schooling affects health.

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic disease affecting 16 million persons in the U.S.,1 and a leading cause of death.2 This is a complex chronic disease, the treatment of which requires considerable personal health investment. By taking certain precautions, disease complications and death can be postponed. In a study of persons with diabetes using HRS data, self-reported health deteriorated more over eight years among less highly educated persons (Goldman and Smith 2002). More highly educated individuals were less likely to be in fair/poor health.

Our study addresses five issues. First, does educational attainment, as measured by the number of years of schooling completed, affect time to diagnosis of diabetes? Second, to what extent are educational attainment and health related among persons with diabetes? Third, how does the estimated effect of educational attainment on health change after accounting for factors that are both potentially affected by educational attainment of persons with diabetes and also affect their health? Fourth, given that educational attainment continues to influence health among persons with diabetes after accounting for these covariates, what are pathways through which educational attainment influences health? Fifth, does the marginal effect of an additional year of schooling vary by level of educational attainment?

II. Conceptual and Econometric Issues

Although the correlation between education and health is well established, the notion that additional schooling causes health improvements is not. Reverse causality from health to years of schooling completed or omitted third variables may cause educational attainment and health to vary in the same direction. There is little reason to expect reverse causation from health to years of schooling since generally the temporal lag between the completion of formal education and the time at which health declines is several decades (Kitagawa and Hauser 1973).

Possible omitted third variables is a more likely source of bias. Among these variables are: native ability (Heckman 2008; Nordin 2008); time preference, including at the time schooling choices are made (Cutler and Lleras-Muney 2010; Fuchs 1982); genetic factors (Jayachandran and Lleras-Muney 2009); poor health in early life which may be positively correlated with poor health in adulthood (Case et al. 2002; Currie and Stabile 2003; Smith 2009) and also affect educational attainment in early life (Adams et al. 2003; Case et al. 2005; Oreopoulos et al. 2008); low income in early life which similarly may affect educational attainment and independently health in later life (Adler and Rehkopf 2008).

The issues are seen from the following two-equation system. In youth and early adulthood, parents and children determine years of schooling (S). S is a function of expected pecuniary and non-pecuniary returns to schooling E(r), where non-pecuniary returns include adult health (HA), price of schooling (PS), and child health (HC), and other factors in childhood (XC), e.g., native ability. Childhood illnesses and low birth weight, determinants of HC, may contribute to lower years of schooling (Case et al. 2002; Conley and Bennett 2000). Low income in childhood may also reduce educational attainment (Haas 2006).

| (1) |

Adult health (HA) is a function of years of schooling, the price of personal health care services (PHS), and other factors (XA).

| (2) |

If S influences HA and HA influences S, the estimated marginal effect of an additional year of schooling will be upward biased. Given ages at which most diabetes is first diagnosed, this possibility is extremely unlikely.

There are two types of diabetes, Type I, which often begins in childhood and Type II, almost always adult onset. The vast majority of persons with DM have Type II. And although Type I is of much earlier onset than Type II, it is rare. In 2007, 0.2 percent of persons under age 20 were diagnosed with either type (http://diabetes.niddk.nih.gov/DM/PUBS/statistics/#people, accessed 12/15/09). In the sample described below, only 2.9 percent of adult respondents with a DM diagnosis reported that they were first diagnosed with diabetes before 25, an age by which formal schooling has generally been completed.

However, XA and XC may be correlated, and HC may be correlated with S and HA. Failure to account for XA, XC, and HC will lead to bias in the estimated effect of schooling.

Many studies have attempted to establish causation from education to health. Several approaches have been used. Researchers have taken natural experiments as instrumental variables (IVs), e.g., changes in compulsory schooling laws (Albouy and Lequien 2009; Chou et al. 2010; Lleras-Muney 2005; Oreopoulos 2006), exemptions from military service (de Walque 2007a), changes in requirements for high school completion (Kenkel et al. 2006), and primary school construction programs (Breierova and Duflo 2004). Other IVs have been college openings for women in the 17th year (Currie and Moretti 2003), tuition free primary education (Osili and Long 2008), and age at school entry policy (McCrary and Royer 2006). Another approach for dealing with endogeneity is to account for unobserved heterogeneity using discrete factor analysis (Arendt 2008; Cowell 2006).

Two aspects of these studies are particularly noteworthy. With exceptions (Albouy and Lequien 2009; Kenkel et al. 2006), IV estimates of effects of education on health have higher implied marginal effects than their ordinary least squares (OLS) counterparts. (Grossman 2004). Hence, OLS estimates of the marginal effect on schooling are likely, if anything, to be lower bounds on schooling’s effect on health. Second, the IVs used in these studies primarily operate at different parts of the frequency distribution of educational attainment. For example, compulsory schooling laws mainly affect high school graduation. The threat of being drafted during the Viet Nam War affected the probability of college graduation.

Still another approach is to use OLS and include measures of HC, XC, and XA as covariates in analysis of the relationship between educational attainment and adult health, essentially the approach used by Cutler and Lleras-Muney (2010). Not only does that study assess schooling effects on health and health behaviors, but by employing alternative specifications, they could assess the sensitivity of educational attainment parameter estimates to presence or absence of other variables, such as those included in HC, XC, and XA. Hence, they could learn about the pathways through which education relates to health. At the same time, they do not make causal claims.

Good IVs for educational attainment of respondents to the HRS are lacking. Compulsory schooling laws became less important by the 1940s (Lleras-Muney 2005) and most HRS sample persons went to school after 1940. Few would have been affected by the Viet Nam draft. Except for place of birth, the HRS does not record where respondents lived in prior years. However, the HRS is rich in measures of HC, XC, and XA.

III. Data

We use longitudinal data from the HRS and a HRS cross sectional supplement, the Diabetes Study (HRS-DS), administered to sample persons by mail in 2003-4 to HRS respondents who by 2002 had reported that they had been told by a physician that they had diabetes.

The HRS is a U.S. panel study of birth cohorts initially 1931-41 and their spouses who could be of any age. The HRS over-samples blacks, Hispanics and Florida residents. Participants were interviewed every two years from 1992–2008. In 1998, persons born during 1942-47 were added to HRS. Assets and Health Dynamics among the Oldest Old (AHEAD), which collected information from persons born during 1913-23, was initially conducted in 1993. Starting in 1998, HRS and AHEAD have been combined.

Medicare-eligible HRS respondents were asked to agree to provide their Medicare identification numbers to allow linkage of their Medicare claims with their survey responses; over 80% of eligible respondents agreed to do so. We identify diabetes-related diagnoses (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification, ICD-9-CM), procedures (Current Procedural Terminology, CPT-4; Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System, HCPCS), and physician visits (U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) provider physician specialties) submitted with each claim using Medicare inpatient, outpatient, and Part B claims data, available from 1993–2007.

As a first step in our empirical analysis, we conduct a survival analysis of time to first diagnosis of DM as revealed by respondents to the HRS-DS or in a wave of the HRS for persons who did not respond to the HRS-DS. We assess time to first diagnosis preferably using the date given in the HRS-DS but otherwise from the regular HRS interviews. Persons who were diagnosed later than 2003-4 or are never diagnosed during the observational period (through 2008) are considered to be right-censored. We use age 30 as the baseline year and 2003-4, the year the HRS-DS was conducted, as the terminal year for this analysis. Responses from 9,757 individuals are included in this analysis.

The rest of our empirical analysis is cross sectional, and the sample consists entirely of persons with a diabetes diagnosis. Of the 18,167 individuals interviewed by HRS in 2002, 3,194 reported having diabetes. After excluding individuals for death or random assignment to another study supplement, 2,341 persons were eligible to participate in the HRS-DS. Of these, 1,901 (81.2%) returned a mail questionnaire.

IV. Empirical Specification

Dependent Variables

Diabetes Diagnosis

We first analyze determinants of time to a first diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, focusing on the role of educational attainment in time to diagnosis but including other covariates based on variables pertaining to the person’s age before 30 as well. Time is measured in years. It is known that diabetes is more highly prevalent but also less likely to be diagnosed among less educated persons (Smith 2007).

Diabetes Complications

We assess relationships between educational attainment and other factors and health outcomes associated with diabetes from the HRS-DS and other data sources: (1) the number of organ systems with a diabetes-related complication at baseline; and (2) change in the number of organ systems with a diabetes-related complication developed from baseline (2003-4) to 2008. Diabetes frequently results in complications involving the eye, kidney, heart, lower extremities, and cerebrovascular system (Sloan et al. 2008). We assume that diabetes complications are an absorbing state.

The first dependent complications variable measures the number of organ systems for which the person reported having complications to the HRS-DS or for whom complications were recorded as diagnoses on Medicare claims by mid 2003. For each organ system, we distinguish between minor and major complications. For example, for cardiac complications, anginaischemic heart disease without a hospitalization, shortness of breath and heart pain at rest or with exercise are considered minor complications. Congestive heart failure, heart attacks, heart surgeries, and angina-ischemic heart disease with a hospitalization are major complications. We count minor complications affecting an organ system as 1 and major complications as 2.

The second dependent complications variable uses data on the change in the number of organ systems affected by complications 2003-4 to 2008. Medicare claims data are only available through 2007; we use these data through this year, relying exclusively on self reports of new complications in 2008 from HRS interviews.

We have data for the change in number of organ systems for 74.1 percent of persons for whom complications were measured at baseline. Educational attainment has no statistically significant effect on the probability of having a report for the change, conditional on having a value for the number of organ systems with complications at baseline.

Given the analysis of years of schooling and variables for HC, HA, and XA on the number of organ systems with complications, we explore reasons for differences in health by years of schooling completed among persons with a diabetes diagnosis.

Health Knowledge

Health knowledge has been linked to efficiency in health production (Grossman 1972). If persons with diabetes are knowledgeable about the disease and its treatment, they are likely to experience better health outcomes, cet. par.

To measure health knowledge, we use two dependent variables. First, we construct a general measure of knowledge of the person’s own diabetes history using the number of “don’t knows” and “uncertains” to questions the HRS-DS asked about the respondent’s experience with diabetes. Presumably if a person cannot recall key aspects of his or her own disease history, s/he will not be able to relate this to his or her physicians and will also be ignorant of other aspects of diabetes care. Individuals are assigned a value of 1 for an item if they answered “don’t know” or “uncertain” for each of 13 items: age at which the person was told by a doctor that s/he had diabetes; DM type; whether or not s/he ever received an HbA1c test; HbA1c at person’s last test; whether or not s/he knows what an HbA1c test is; whether or not s/he ever had diabetes education other than during routine doctor or nurse visits; reason an individual has not sought diabetes education or has not seen a dietician; number of days in the last month s/he had symptoms of low or high blood sugar; when his/her last blood pressure reading was performed; what the person’s blood pressure reading was; and when the last cholesterol test was performed. We reverse the count so that higher count signifies greater knowledge. The knowledge count ranges from 0 to 10 with a mean of 7.99 (standard deviation 1.99).

The second knowledge measure gauges the individual’s understanding of diabetes care processes. The HRS-DS asked respondents to rate on a 4-point scale how well s/he understood: how to take his/her insulin or other medications, what each of his/her prescribed medications do; how to choose the food s/he should eat, how to read nutrition labels on food; how to exercise; how and when to test his/her blood sugar; how to care for his/her feet; and what the complications of diabetes are. A rating of 1 represented “I don’t understand it at all” and a rating of 4 was for “I understand completely.” We create a continuous variable for understanding diabetes care processes by summing respondents’ responses to these 8 questions. The count ranges from 8 to 32 with a mean of 25.93 (standard deviation 4.91).

Use of Personal Health Care Services

Goldman and Smith (2002) inferred from their empirical findings that less educated persons benefit more from enforced treatment protocols in randomized clinical trials, possibly because they more often lack the knowledge or self control to be effective diabetes self-managers.

To test whether or not persons with more schooling are better at following instructions, we use an adherence index based on responses to the HRS-DS (Sloan et al. 2009). We construct the index from responses indicating whether during the previous year, an individual (1) received an HbA1c and/or (2) cholesterol test; (3) received an eye examination; (4) tried to lose weight or had a body mass index of ≤25 at the 2002 HRS interview; (5) exercised regularly; and (6) reported “rarely/never” missing taking a prescribed dose of oral diabetes medication. Index values range from 0 to 6, with a higher index denoting greater adherence. The mean is 3.51 (standard deviation 1.30).

We also investigate whether or not more highly educated persons obtain care from a larger number of types of diabetes specialists. It is unlikely that any one type of health professional can provide the comprehensive range of services likely to confer benefit on most persons with diabetes. Even if there are no complications, practice guidelines specify regular, routine examinations of eyes and lower extremities (American Diabetes Association 2009).

Our measure is based on the number of types of diabetes specialists persons with diabetes saw in the year following the HRS-DS. The count ranges from 0 to 7 with a mean of 3.08 (standard deviation 1.46). The specialist count consists of general physicians (general practitioners, family practitioners, internists, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants), cardiologists, endocrinologists, podiatrists, lower extremity specialists (general surgeons, dermatologists, neurologists, orthopedic surgeons, physical medicine and rehabilitation specialists, diagnostic radiologists, physical therapists), eye specialists (ophthalmologists and optometrists), and nephrologists. We define a continuous variable for number of types of diabetes specialists the person saw in the year following the HRS-DS.

Data for the dependent variable come from Medicare claims information merged with the HRS. Since the number of types of providers is plausibly related to number of organ systems with diabetes complications, we include an explanatory variable for the number of organ systems with complications (described above). The remaining explanatory variables are as above, except the covariate for uninsured is dropped because everyone in this sample had Medicare.

Our adherence index described above includes use of some (e.g., eye care) but not most of the provider types relevant for diabetes care.

Explanatory Variables: Analysis of Time to a First Diagnosis of Diabetes

The analysis of time to first diagnosis of diabetes includes covariates for educational attainment, demographic characteristics—male gender, child health, and child socioeconomic status. The variable for poor child health is set to 1 if the person reported being in fair or poor health in childhood and 0 otherwise. The HRS asked respondents to rate their health as a child. Possible responses are excellent, very good, good, fair, and poor. 6.6 percent of the sample reported poor health as a child. The variable for low child socioeconomic status as a child is set to 1 if the person said his/her family’s socioeconomic status was poor in childhood and is 0 otherwise. The HRS asked whether the respondent’s family growing up was “pretty well off financially, about average, or poor.” 36.3 percent said they had low child SES.

Explanatory Variables: Persons with a Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus

Child Health (HC) and Low Child SES (XC)

The covariates just described are also explanatory variables in our cross sectional analysis.

Adult Characteristics (XA)

We measure cognition as of 1998. We use 1998 values since 1998 is the first year for which HRS obtained cognition data on most respondents. Cognition in adulthood and cognition in youth are positively correlated (Richards et al. 2004). Thus, by including cognition in adulthood, we account for the person’s cognitive status while of school age.

The cognitive score is a sum of four separate measures. (1) HRS asks respondents to remember as many words as possible from a list of 10 words that were read to them by the interviewer and to recall the words immediately and (2) five minutes after the list was read to them. (3) To measure a working memory based on serial 7s subtraction, respondents were required to subtract seven from 100 five times. They are assigned a value of one for each correct subtraction. (4) A count of correct responses to various questions measuring knowledge, language and orientation was compiled. Survey individuals were asked the month, day, year, and day of the week of the interview, and to name the following: the thing used to cut paper, the prickly plant that grows in the desert, the current U.S. president and the current U.S. vice president. They were also asked to count backwards starting from 20 to 10. Respondents are assigned a value of 2 for counting correctly the first time, 1 for counting correctly on the second try, and 0 for an incorrect count both times.3 The total score varies from 0 to 35 with 35 signifying highest cognitive ability.4

The HRS-DS asked one question to elicit time preference. Respondents were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with the following statement: “I live life one day at a time and don’t think much about the future.” Responses were elicited on a 5-point scale with 1 representing “strongly disagree” and 5 representing “strongly agree.” We create a binary variable for time preference: “patient” with 0 for “agree” or “strongly agree” and 1 representing other responses. We reverse the 0’s and 1’s so that a value of 1 signifies that the person is patient.

To measure risk preferences in the financial domain, the HRS asks respondents to choose among 4 different gambles. Following Barsky et al. (1997), we construct a measure of risk tolerance set to 0.15 if the sample person rejected both the one-third and one-fifth gambles, 0.28 if s/he rejected the one-third gamble but accepted the one-fifth gamble, 0.35 if s/he accepted the one-third gamble but rejected the one-half gamble, and 0.57 if s/he accepted both the one-third and one-half gambles. Barsky et al. (1997) showed that this measure of risk preference is related to several personal decisions and behaviors. When a value for risk preferences is missing, we set the risk preference variable to 0 and define a separate explanatory variable for missing equal to 1.

HRS-DS asked how much the respondent agreed or disagreed with the following statement, “I have little control over things that happen to me.” Responses were elicited on a five-point scale with 1 representing “strongly disagree” and 5 representing “strongly agree.” To measure high self control, we create a binary variable set to 0 if the person responded “agree” or “strongly agree” and is 1 otherwise and again reverse code so that the binary variable is 1 for persons with high self control.

HRS-DS asked how much respondents agreed or disagreed with the following: “I can do just about anything I set out to do.” Responses were elicited on a 5-point scale from which we construct a binary variable with high self-confidence set to 1 for “agree” or “strongly agree” and 0 otherwise. Responses to this question represent a measure of high self-confidence in the person’s ability to carry out his/her plans.

Household income and whether or not the individual has no health insurance were elicited in the 2002 HRS, both measures of XA. We also include measures of diabetes duration and its square. As explained above, HRS-DS asked the age at which respondents received their first diabetes diagnosis.

Finally, in all specifications, we include covariates for demographic characteristics (male gender, Black, non-Black Hispanic, and other race, with White, the reference group, and marital status).

Estimation

For the analysis of time to first diagnosis of diabetes, we use a Cox proportional hazard model. In the analysis limited to persons with a diabetes diagnosis, we use OLS. In preliminary analysis, we used negative binomial for analysis of count dependent variables. Some of the runs did not converge. When we did obtain parameter estimates from both negative binomial and OLS, the implied marginal effects from negative binomial were very close to the corresponding OLS parameter estimates. None of the dependent variables have thick tails at the extremes of the distributions.

IV. Results

Time to First Diagnosis with Diabetes Mellitus

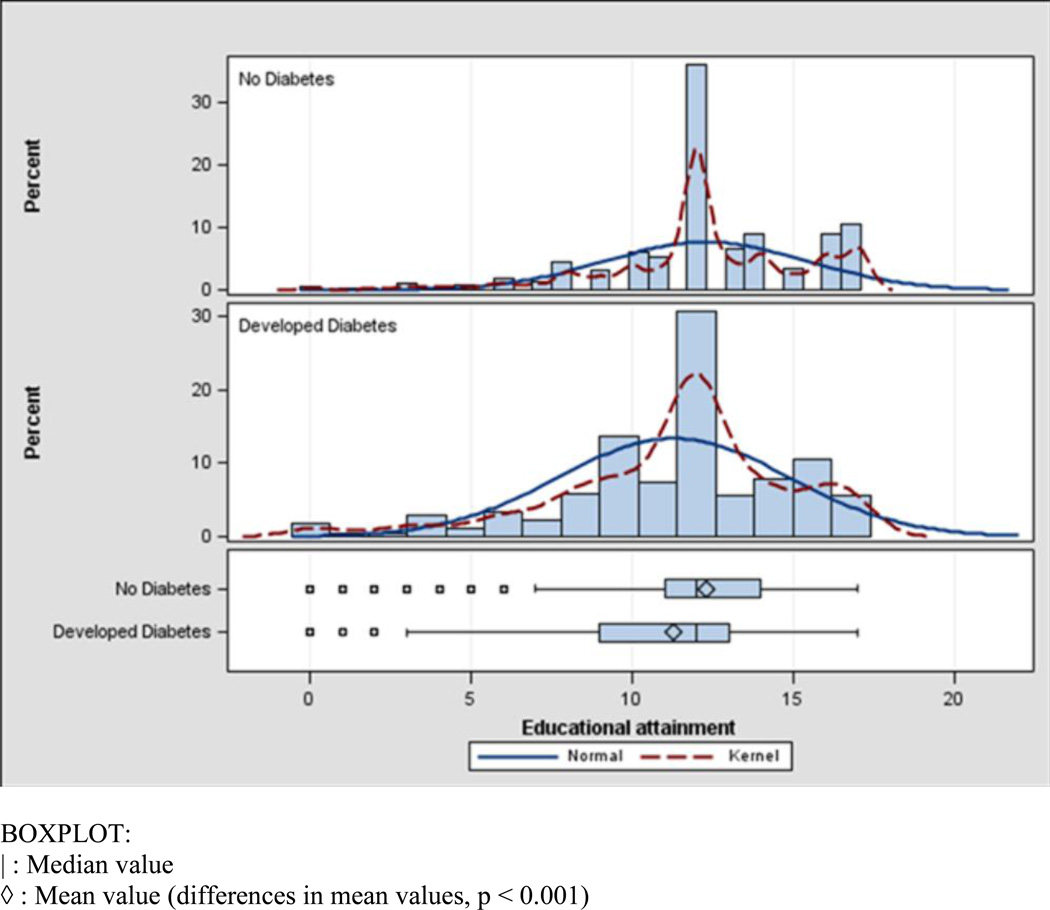

Persons who were diagnosed with diabetes are statistically different on all of the baseline characteristics except one (Table 1). Mean educational attainment is a year higher for the non-diabetes group. Median educational attainment is the same for both groups (Fig. 1). However, there are proportionally more persons in the lower tail of the distribution of years of schooling for persons with than without diabetes. By contrast, the upper tails are quite similar. Persons with a diabetes diagnosis are more likely to be Black and Hispanic.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics: Time to First Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus

| No Diabetes | Developed Diabetes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | |

| Educational attainment | 12.30 | 3.14 | 11.29** | 3.58 |

| Male | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0.50** | 0.50 |

| White non-Hispanic | 0.76 | 0.43 | 0.61** | 0.49 |

| Black | 0.14 | 0.35 | 0.23** | 0.42 |

| Other non-Hispanic | 0.020 | 0.14 | 0.026 | 0.16 |

| Non-Black Hispanic | 0.082 | 0.27 | 0.14** | 0.35 |

| Low child SES | 0.31 | 0.46 | 0.36** | 0.48 |

| Poor child health | 0.066 | 0.25 | 0.089** | 0.29 |

| Observations | 8,846 | 911 | ||

significantly different from No Diabetes Group at the 1% significant level

significantly different from No Diabetes Group at the 5% significant level

Figure 1.

Frequency Distribution for Educational Attainment by Development of Diabetes Mellitus

Holding other factors constant, an increase of a year of schooling decreases the hazard of being diagnosed with DM by 0.04 (hazard ratio (HR)=0.96; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.94–0.98, Table 2), which is the mean difference in educational attainment between those with and those without a diabetes diagnosis in Table 1. Thus, while there is a statistical difference in educational attainment between the two groups, the effect of a difference in this range on the probability of being diagnosed with diabetes is small. Persons of Black, Hispanic, or non-White ethnicity are nearly twice as likely to be diagnosed with diabetes than were White non-Hispanics, the omitted reference group. Poor health as a child raises the probability of a DM diagnosis by 27 percent (HR=1.27; 95% CI, 1.01–1.60).

Table 2.

Survival Analysis of Time to First Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus

| Hazard Ratio [95% CI] | |

|---|---|

| Educational attainment | 0.96** [0.94 0.98] |

| Male | 1.06 [0.93 1.21] |

| Black | 1.92** [1.62 2.26] |

| Other non-Hispanic | 1.82* [1.21 2.74] |

| Non-Black Hispanic | 1.85** [1.49 2.30] |

| Low child SES | 1.01 [0.88 1.16] |

| Poor child health | 1.27* [1.01 1.60] |

| Observations | 9,757 |

significantly different from No Diabetes Group at the 1% significant level

significantly different from No Diabetes Group at the 5% significant level

Analysis of Persons with a Diabetes Diagnosis

Mean educational attainment in an analysis sample of persons with a diabetes diagnosis is 11.5 years (Table 3), which is slightly different from the corresponding Table 1 value since the Table 1 value includes persons with diabetes who did not respond to the HRS-DS. In 2003-4, sample persons in this study had a mean age of nearly 70 with a standard deviation of nearly 9 years.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics: Persons Diagnosed with Diabetes Mellitus

| Dependent variables | Mean | Std dev |

|---|---|---|

| Number of organ systems affected by complications of diabetes, 2003 | 2.82 | 2.17 |

| Number of organ systems affected by complications of diabetes, 2003-8 | 1.46 | 1.44 |

| Knowledge about person’s own diabetes history | 7.99 | 1.99 |

| Understanding diabetes care | 25.93 | 4.91 |

| Following instructions—adherence count | 3.51 | 1.30 |

| Number of diabetes specialists visited in year | 3.08 | 1.46 |

| Explanatory variables | ||

| Educational attainment | 11.52 | 3.54 |

| Poor child health (HC) | 0.070 | 0.26 |

| Low child SES (XC) | 0.36 | 0.48 |

| Cognition | 19.84 | 5.68 |

| Time preference: patient | 0.59 | 0.49 |

| High risk tolerance | 0.23 | 0.13 |

| High self-control | 0.69 | 0.46 |

| High self-confidence | 0.55 | 0.50 |

| Household income (10,000s) | 4.04 | 5.35 |

| No health insurance | 0.040 | 0.20 |

| Years since first diagnosis of diabetes | 12.44 | 11.78 |

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| Age | 69.81 | 8.97 |

| Male | 0.47 | 0.50 |

| White non-Hispanic | 0.68 | 0.47 |

| Black | 0.19 | 0.40 |

| Non-Black Hispanic | 0.11 | 0.31 |

| Other non-Hispanic | 0.019 | 0.14 |

| Married | 0.63 | 0.48 |

| Observations | 1,895 | |

Higher educational attainment leads to a reduced number of organ systems with complications at baseline, 2003-4, and to fewer increases in complications between 2003-4 and 2008 (Table 4). In the most limited specification, an additional year of schooling reduces the number of affected organ systems by 0.083. Including measures of HC and XC, poor child health and low child socioeconomic status, slightly reduces estimated effects of educational attainment. Neither poor child health nor low SES as a child affects the number of complications at baseline. Including variables for XA, cognition, time preference, risk tolerance, self control, self confidence, income, health insurance, and years since the diabetes diagnosis, an added year of schooling reduces the number of organ systems with complications at baseline by 0.044 (relative to an observational mean of 2.82).

Table 4.

Organ Systems Affected by Complications of Diabetes,

| 2003-4 | Change 2003-8 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Educational attainment | 0.083*** (0.017) | 0.079*** (0.017) | −0.044** (0.017) | 0.058*** (0.012) | 0.051*** (0.012) | 0.038*** (0.014) |

| Poor child health | 0.31 (0.20) | 0.23 (0.18) | 0.29** (0.14) | 0.28** (0.14) | ||

| Low child SES | 0.10 (0.11) | 0.11 (0.10) | 0.20** (0.081) | 0.20** (0.081) | ||

| Cognition | −0.020** (0.010) | −0.014* (0.008) | ||||

| Time preference: patient | −0.20** (0.10) | 0.070 (0.086) | ||||

| High risk tolerance | 0.71 (0.55) | −0.44 (0.44) | ||||

| High self-control | −0.24** (0.11) | −0.18* (0.10) | ||||

| High self-confidence | 0.95*** (0.10) | −0.13 (0.080) | ||||

| Household income | −0.020* (0.011) | −0.012** (0.005) | ||||

| No health insurance | −0.42* (0.24) | 0.12 (0.18) | ||||

| Years since first diagnosis of diabetes | 0.10*** (0.010) | 0.007 (0.008) | ||||

| Years since first diagnosis of diabetes² | 0.001*** (0.000) | −0.000 (0.000) | ||||

| R2 | 0.062 | 0.064 | 0.19 | 0.048 | 0.055 | 0.069 |

| Observations | 1,895 | 1,405 | ||||

Also includes covariates for age, male gender, Black, Hispanic, other race, and marital status not shown.

p<0.1;

p<0.05;

p<0.01

The estimated effect of an additional year of schooling on the change in number of organ systems with complications is slightly lower than in the analysis of complications at baseline. Both poor child health and low child SES increase the number of complications developed between 2003-4 and 2008, implying that a link exists between poor health, low income and educational attainment of parents of HRS respondents and respondents’ health decline in late life.

Time preference, self control, self-confidence, cognitive ability, and diabetes duration are significantly related to the number of organ systems with complications at baseline. Relatively patient individuals and those with high self control and self confidence tended to have fewer organ systems with complications as did persons with high cognitive ability. While these results are not new, they do indicate that these explanatory variables measure what they are designed to measure and capture some of effect on health that otherwise would be attributed to years of schooling. Diabetes duration was positively related to the number of organ systems with complications at baseline.

In the analysis of change in the number of complications, among XA variables, only the parameter estimate for income is statistically significant. Interestingly, the effects of poor child health and low childhood socioeconomic status persist even with inclusion of several covariates. The changes in number of complications occurred half a century or so after the years in which sample persons experienced disadvantages of poor health and low income and associated factors in childhood.

V. Why Does Educational Attainment Affect Health?

Overview

While part of the explanation for more highly educated persons being healthier can be attributed to higher income, cognitive ability, and other factors, including time and risk preferences, and self control, a residual effect of educational attainment on health, the latter measured by the number of organ systems with complications remains.

There are several possible additional explanations for this result. First, schooling raises a person’s productivity in producing health. Grossman (1972) argued that more highly educated individuals may recognize signs and symptoms of disease and seek medical care more quickly. Second, schooling may teach individuals how to acquire and process new information more rapidly and accurately (de Walque 2007b).

Third, more highly educated persons may be better at following instructions (Goldman and Smith 2002; Smith 2007). This skill may be acquired in school, in which case following instructions is part of the causal effect of schooling; alternately, people who spend a lot of time in school may have a higher propensity to engage in activities in which following instructions is required. Fourth, additional schooling may widen individuals’ social networks, thereby improving access to physicians (Cutler and Lleras-Muney 2010; Khwaja et al. 2009).

The HRS-DS provides direct measures of diabetes-specific knowledge and adherence to medical recommendations for persons with diabetes. From Medicare claims we can monitor individuals’ use of specialists in diabetes care.

That additional schooling improves knowledge and increases the propensity to follow instructions receives strong empirical support in Tables 5 and 6. Cet. par., educational attainment is positively related to knowledge about one’s own diabetes history with an effect size of 0.10 (SE: 0.016; Table 5, col. 3). Persons with lower SES as a child have worse knowledge of their own diabetes history (cols. 2 and 3), although the parameter estimate is not quite statistically significant at the 0.05 level. The marginal effect for educational attainment is positive and nearly 40 percent lower in the full (col. 3) than in the limited specifications when only demographic characteristics and/or only demographic characteristics and child characteristics are included as covariates. In the full specification, persons with high self-control and high self-confidence have better health knowledge about their own diabetes history as do those with higher cognitive ability, and longer diabetes duration.

Table 5.

Health Knowledge

| Knowledge about Person’s Own Diabetes History | Understanding Diabetes Care Processes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Educational attainment | 0.14*** (0.015) | 0.14*** (0.015) | 0.10*** (0.016) | 0.17*** (0.044) | 0.14*** (0.045) | 0.12** (0.048) |

| Poor child health | −0.15 (0.19) | −0.056 (0.19) | −1.06* (0.55) | −0.74 (0.55) | ||

| Low child SES | −0.18* (0.096) | −0.17* (0.094) | −0.86*** (0.27) | −0.80*** (0.27) | ||

| Cognition | 0.023** (0.009) | −0.018 (0.025) | ||||

| Time preference: patient | 0.18* (0.095) | 0.20 (0.27) | ||||

| High risk tolerance | 0.70 (0.58) | 0.058 (1.59) | ||||

| High self-control | 0.25** (0.11) | 0.28 (0.30) | ||||

| High self-confidence | 0.48*** (0.089) | 1.70*** (0.25) | ||||

| Household income | 0.013* (0.008) | −0.014 (0.022) | ||||

| No health insurance | −0.27 (0.23) | −1.57** (0.67) | ||||

| Years since first diagnosis of diabetes | 0.028*** (0.009) | 0.10*** (0.026) | ||||

| Years since first diagnosis of diabetes² | −0.000** (0.000) | 0.001*** (0.001) | ||||

| R2 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.10 |

| Observations | 1,895 | 1.523 | ||||

Also includes covariates for age, male gender, Black, Hispanic, other race, and marital status not shown.

p<0.1;

p<0.05;

p<0.01

Table 6.

Following Instructions—Adherence Count

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Educational attainment | 0.089*** (0.010) | 0.088*** (0.010) | 0.070*** (0.010) |

| Poor child health | −0.021 (0.11) | −0.001 (0.11) | |

| Low child SES | −0.027 (0.063) | −0.024 (0.062) | |

| Cognition | 0.011* (0.006) | ||

| Time preference: patient | 0.061 (0.063) | ||

| High risk tolerance | 0.22 (0.41) | ||

| High self-control | 0.12* (0.068) | ||

| High self-confidence | 0.17*** (0.059) | ||

| Household income | 0.01** (0.005) | ||

| No health insurance | −0.28* (0.16) | ||

| Years since first diagnosis of diabetes | 0.012** (0.006) | ||

| Years since first diagnosis of diabetes² | −0.000 (0.000) | ||

| R2 | 0.078 | 0.079 | 0.11 |

| Observations | 1,895 | ||

Also includes covariates for male gender, Black, Hispanic, other race, and marital status not shown.

p<0.1;

p<0.05;

p<0.01

Persons with higher educational attainment have better understanding of care processes, with effects ranging from 0.17 (SE: 0.044; col. 4) in the most limited to 0.12 (SE: 0.048; col. 6) in the full specification. The marginal effect for educational attainment for understanding care processes is about the same as for knowledge of one’s own diabetes history, but both are low relative to the observational means of the dependent variables (7.99 and 25.93, respectively, Table 3).

As with knowledge of personal diabetes history, highly self-confident persons have a better understanding of care processes. Those with without health insurance (4 percent of the sample) do not, on average, understand care processes as well as others. This analysis too lends support to the view that better health knowledge explains part of the observed effect of educational attainment on health.

More highly educated individuals are also better at following instructions as measured by the number of diabetes guidelines to which the person adhered (Table 6). Adding additional explanatory variables only decreases the implied marginal effect of educational attainment slightly. The marginal effect of 0.070 is low relative to an observational mean of this dependent variable of 3.51, but this mean value is substantially lower than those for the dependent variables in the previous table. Higher income and more self-confident individuals and those with greater time from first diabetes diagnosis, also tended to be more adherent. The parameter estimate for self-control is positive and almost statistically significant at conventional levels (p=0.07).

In sum, additional schooling leads to improvements in both types of health knowledge and in following instructions. Our empirical tests support the conventional wisdom that education improves efficiency in household production, but they do not allow us to conclude that one source of efficiency is improved relative to the others.

Evidence that higher educational attainment increases the probability of visiting more types of diabetes specialists, possibly by improving social networks, is weaker than for knowledge (Table 7). The parameter estimate for educational attainment loses statistical significance at conventional levels in the full specification. While the parameter estimate on income is positive, the negative sign on the parameter estimate for high self-control suggests that obtaining care from many provider types may reflect patient indecision among patients with less than “high” self-control. As anticipated, persons with higher household income and in worse health (higher values of “comorbidities”) see a higher number of types of diabetes specialists in a year.

Table 7.

Number of Types of Diabetes Specialists Visited in Year

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Educational attainment | 0.048*** (0.014) | 0.046*** (0.014) | 0.028* (0.016) |

| Poor child health | −0.20 (0.17) | −0.13 (0.17) | |

| Low child SES | −0.046 (0.090) | −0.048 (0.090) | |

| Cognition | 0.019** (0.009) | ||

| Time preference: patient | 0.075 (0.091) | ||

| High risk tolerance | 0.93 (0.89) | ||

| High self-control | −0.29*** (0.097) | ||

| High self-confidence | 0.084 (0.087) | ||

| Household income | 0.034*** (0.012) | ||

| No health insurance | −0.44 (0.41) | ||

| Comorbidities | 0.23*** (0.020) | 0.23*** (0.020) | 0.23*** (0.021) |

| Years since first diagnosis of diabetes | 0.003 (0.008) | ||

| Years since first diagnosis of diabetes² | 0.000 (0.000) | ||

| R2 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.19 |

| Observations | 1,046 | ||

Also includes covariates for male gender, Black, Hispanic, other race, and marital status not shown.

p<0.1;

p<0.05;

p<0.01

In sum, in the analysis of a sample of persons with a diabetes diagnosis, including other covariates always reduces the marginal effect of years of schooling but in varying amounts. In the analysis of number of organ systems with complications, the relative magnitude of the coefficient on educational attainment implies that 47 percent of the estimated effect of educational attainment is accounted for by the other factors included the full specification versus specifications with only the educational attainment variable. In analysis of change in organ systems affected by complications, the corresponding percentage is 35 percent. In the other regressions, corresponding reductions in estimated effects of an additional year of schooling vary from 42 percent for number of diabetes specialists seen to 21 percent for following instructions.

VI. Does the Marginal Product of Educational Attainment Vary According to Years of Schooling Completed?

We reestimate all equations, substituting a spline for years of schooling completed—≤10, 11–12, and 13+ years for the educational attainment variable used above (Table 8). The vast majority of parameter estimates on years of schooling completed are statistically significant at conventional levels. Overall, there is no consistent pattern. While for complications at baseline and understanding diabetes care processes, the marginal effect for the lowest educational group is relatively high, for knowledge about personal diabetes health history, the opposite result holds. Results on diabetes knowledge imply some learning about diabetes occurs as time from initial diagnosis of diabetes increases.

Table 8.

Spline for Educational Attainment

| Years of Schooling Completed |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 10 Years | 11 or 12 Years | ≥ 13 Years | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Organ systems adversely affected by diabetes, 2003 | −0.093** (0.039) | −0.069** (0.028) | −0.062*** (0.022) |

| Organ systems adversely affected by diabetes, 2008 | −0.11** (0.045) | −0.10*** (0.032) | −0.086*** (0.026) |

| Change in organ systems adversely affected by diabetes 2003-8 | −0.041* (0.025) | −0.046** (0.018) | −0.039*** (0.015) |

| Knowledge about Person’s Diabetes History | 0.090** (0.035) | 0.10*** (0.026) | 0.10*** (0.020) |

| Understanding diabetes care processes | 0.23** (0.10) | 0.19*** (0.071) | 0.16*** (0.058) |

| Following instructions—adherence to guidelines | 0.047** (0.022) | 0.053*** (0.016) | 0.063*** (0.013) |

| Number of types of diabetes specialists visited in year | −0.044 (0.032) | −0.011 (0.023) | −0.003 (0.019) |

p<0.1;

p<0.05;

p<0.01

VIII. Discussion and Conclusions

The hazard of being diagnosed with diabetes mellitus is somewhat lower for persons with fewer years of schooling completed. The mean difference in educational attainment between persons with and without a diagnosis is about a year with the difference in mean values mainly reflecting a higher proportion of persons with low educational attainment in the diabetes group. The difference in mean educational attainment is noteworthy but at the same time sufficiently similar to lend support the view that patterns entirely based on evidence from persons with a diabetes diagnosis generalize to near elderly and elderly persons whether or not they have diabetes.

Conditional on having been diagnosed with diabetes, persons with more years of schooling completed tend to have fewer organ systems with diabetes complications. These findings hold even after accounting for various factors that covary with educational attainment: cognitive ability; time and risk preferences; and self-control and self-confidence; household income; and demographic characteristics.

Given the positive coefficients for educational attainment on health, there is the question of the pathways through which educational attainment operates to improve health. There is strong empirical support for all three pathways we considered; Persons with more formal education have better knowledge of their own diabetes history and underlying disease processes of diabetes and are better at following instructions they receive from physicians and others. Admittedly, persons who are better at following instructions may perform better in school and therefore chose to stay in school longer. Also, although the relationships between educational attainment and knowledge and following instructions are statistically significant and hold even after accounting for influences (e.g., self-control which themselves may have influenced years of schooling), marginal effects of years of schooling are low relative to their observational means. Raising the number of years of schooling completed should contribute to better health, but this strategy is from a panacea in improving population health.

More highly educated persons tend to use a broader range of health care providers, conditional on the number of organ systems with complications and other factors. Such persons may have better access than others to high quality medical care through their networks and therefore visit a larger number of types of diabetes specialists. However, empirical support in our study for the relationship between the number of diabetes specialists visited in a year is weaker than for relationships between diabetes knowledge and following instructions.

We do not instrument for educational attainment; rather we argue that diabetes onset could not have been anticipated at the time educational decisions were made. Marginal effects of a year of schooling on health, health knowledge, and utilization of personal health services are low relative to their observational mean values. If these marginal effects are biased away from zero in a positive direction, which is the most likely effect in the presence of endogeneity of years of schooling completed in this context, we note that the effects are small in any case. ,

Exogenous policies which affect educational attainment at the lower end of the frequency distribution of years of schooling completed can sometimes serve as useful instruments (see e.g., (Chou et al. 2010; Lleras-Muney 2005). The assumption underlying this IV strategy is that it is gains in educational attainment at the lower end that affect health and related outcomes. In our study, we find no consistent pattern. Marginal effects of years of schooling on health are not concentrated at a particular point in the frequency distribution of years of schooling completed.

The focus of our study is on education attainment and health. Yet two other sets of findings are particularly noteworthy. First, our results show that health and home environment as a child have long-lasting effects on th person’s well-being as a result. Second, such personal attributes as self-confidence and self-control, measured as here in adulthood are important factors in explaining variations in adult outcomes.

Finally, although a link between education and health exists, the underpinnings of this relationship are complex. Particularly in view of these complexities, conducting case studies such as we have done for diabetes mellitus can yield useful insights. Monitoring decision making for a variety of chronic diseases would be a highly worthwhile undertaking as is empirical analysis of individuals much earlier in the life cycle to undercover relationships with educational attainment and variables assumed here to be exogenous.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: Partial support for this research came from grants from the National Institute on Aging (2R37-AG-17473-05A1).

Footnotes

Source: http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/prev/national/figpersons.htm, accessed 4/18/08.

Source: National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 56 No. 10.

This 4th measure is a modified version of the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status or TICS score (Brandt et al. 1988)

Individuals without a valid cognition score received a 0 and we set a dummy variable for cognitive score missing equal to 1 for these persons (not shown).

Contributor Information

Padmaja Ayyagari, Email: Padmaja.ayyagari@yale.edu.

Daniel Grossman, Email: Dan.s.grossman@gmail.com.

References

- Adams P, Hurd MD, McFadden D, Merrill A, Ribeiro T. Healthy, wealthy, and wise? Tests for direct causal paths between health and socioeconomic status. Journal of Econometrics. 2003;112(1):3–56. [Google Scholar]

- Adler NE, Rehkopf DH. Us disparities in health: Descriptions, causes, and mechanisms. Annual Review of Public Health. 2008;29:235–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090852. [Review] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albouy V, Lequien L. Does compulsory education lower mortality? Journal of Health Economics. 2009;28(1):155–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes-2009. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:S13–S61. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arendt JN. In sickness and in health - till education do us part: Education effects on hospitalization. Economics of Education Review. 2008;27(2):161–172. [Google Scholar]

- Barsky RB, Juster FT, Kimball MS, Shapiro MD. Preference parameters and behavioral heterogeneity: An experimental approach in the health and retirement study*. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1997;112(2):537–579. [Google Scholar]

- Breierova L, Duflo E. The impact of education on fertility and child mortality: Do fathers really matter less than mothers? National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 10513. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Case A, Fertig A, Paxson C. The lasting impact of childhood health and circumstance. Journal of Health Economics. 2005;24(2):365–389. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case A, Lubotsky D, Paxson C. Economic status and health in childhood: The origins of the gradient. American Economic Review. 2002;92(5):1308–1334. doi: 10.1257/000282802762024520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou S-Y, Liu J-T, Grossman M, Joyce T. Parental education and child health: Evidence from a natural experiment in taiwan. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 2010;2(1):33–61. doi: 10.1257/app.2.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley D, Bennett NG. Is biology destiny? Birth weight and life chances. American Sociological Review. 2000;65(3):458–467. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Cowell AJ. The relationship between education and health behavior: Some empirical evidence. Health Economics. 2006;15(2):125–146. doi: 10.1002/hec.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie J, Moretti E. Mother's education and the intergenerational transmission of human capital: Evidence from college openings. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2003;118(4):1495–1532. [Google Scholar]

- Currie J, Stabile M. Socioeconomic status and child health: Why is the relationship stronger for older children? American Economic Review. 2003;93(5):1813–1823. doi: 10.1257/000282803322655563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler DM, Lleras-Muney A. Understanding differences in health behaviors by education. Journal of Health Economics. 2010;29(1):1–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Walque D. Does education affect smoking behaviors? Evidence using the vietnam draft as an instrument for college education. Journal of Health Economics. 2007a;26(5):877–895. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Walque D. How does the impact of an hiv/aids information campaign vary with educational attainment? Evidence from rural uganda. Journal of Development Economics. 2007b;84(2):686–714. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs VR. Time preference and health: An exploratory study. In: Fuchs VR, editor. Economic aspects of health. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1982. pp. 93–120. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman DP, Smith JP. Can patient self-management help explain the ses health gradient? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(16):10929–10934. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162086599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman M. On the concept of health capital and the demand for health. The journal of political economy. 1972;80(2):223–255. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman M. The demand for health, 30 years later: A very personal retrospective and prospective reflection. Journal of Health Economics. 2004;23(4):629–636. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas SA. Health selection and the process of social stratification: The effect of childhood health on socioeconomic attainment. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2006;47(4):339–354. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700403. [Article] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ. Schools, skills, and synapses. Economic Inquiry. 2008;46(3):289–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-7295.2008.00163.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayachandran S, Lleras-Muney A. Life expectancy and human capital investments: Evidence from maternal mortality declines. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2009;124(1):349–397. [Google Scholar]

- Kenkel D, Lillard D, Mathios A. The roles of high school completion and ged receipt in smoking and obesity. Journal of Labor Economics. 2006;24(3):635–660. [Google Scholar]

- Khwaja A, Sloan F, Wang Y. Do smokers value their health and longevity less? Journal of Law & Economics. 2009;52(1):171–196. [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa E, Hauser P. Differential mortality in the United States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Lleras-Muney A. The relationship between education and adult mortality in the united states. Review of Economic Studies. 2005;72(1):189–221. [Google Scholar]

- McCrary J, Royer H. The effect of female education on fertility and infant health: Evidence from school entry policies using exact date of birth. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 12329. 2006 doi: 10.1257/aer.101.1.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordin M. Ability and rates of return to schooling-making use of the swedish enlistment battery test. Journal of Population Economics. 2008;21(3):703–717. [Google Scholar]

- Oreopoulos P. Estimating average and local average treatment effects of education when compulsory schooling laws really matter. American Economic Review. 2006;96(1):152–175. [Google Scholar]

- Oreopoulos P, Stabile M, Walld R, Roos LL. Short-, medium-, and long-term consequences of poor infant health - an analysis using siblings and twins. Journal of Human Resources. 2008;43(1):88–138. [Google Scholar]

- Osili UO, Long BT. Does female schooling reduce fertility? Evidence from nigeria. Journal of Development Economics. 2008;87(1):57–75. [Google Scholar]

- Richards M, Shipley B, Fuhrer R, Wadsworth MEJ. Cognitive ability in childhood and cognitive decline in mid-life: Longitudinal birth cohort study. British Medical Journal. 2004;328(7439):552–554B. doi: 10.1136/bmj.37972.513819.EE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz T. Reflections on investment in man. The journal of political economy. 1962;70(5):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan FA, Bethel MA, Ruiz D, Shea AH, Feinglos MN. The growing burden of diabetes mellitus in the US elderly population. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008;168(2):192–199. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan FA, Padron NA, Platt AC. Preferences, beliefs, and self-management of diabetes. Health Services Research. 2009;44(3):1068–1087. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00957.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JP. The impact of socioeconomic status on health over the life-course. Journal of Human Resources. 2007;42(4):739–764. [Google Scholar]

- Smith JP. The impact of childhood health on adult labor market outcomes. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2009;91(3):478–489. doi: 10.1162/rest.91.3.478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]