Abstract

Although ovarian epithelial tumors are widely believed to arise in the coelomic epithelium that covers the ovarian surface, it was also suggested that they could instead arise from tissues that are embryologically derived from the mullerian ducts. This article revisits this debate based on recent epidemiological and molecular biological observations as well as evidence based on histopathological observations of surgical specimens from individuals with familial ovarian cancer predisposition. Morphological, embryological, and molecular biological characteristics of ovarian epithelial tumors that must be accounted for in formulating a theory about their cell of origin are reviewed, followed by comments about the ability of these two hypotheses to account for each of these characteristics. An argument is made that primary ovarian epithelial tumors fallopian tube carcinomas, and primary peritoneal carcinomas are all mullerian in nature and could therefore be regarded as a single disease entity. Although a significant proportion of cancers presently regarded as of primary ovarian origin arise in the fimbriated end of the fallopian tube, this site cannot account for an equally significant proportion of these tumors, which are most likely derived from components of the secondary mullerian system.

Progress in understanding the biology of ovarian epithelial tumors is complicated by the fact that their exact tissue of origin is still unclear. This knowledge is essential to understand the mechanisms underlying the risk factors for this important disease of women and is important for the development of effective screening protocols aimed at their early detection. I argued, nearly a decade ago, that the favored hypothesis that these tumors arise from the mesothelial cell layer lining the ovarian surface (ovarian coelomic epithelium) should be revised1. These arguments are revisited in this article in light of recent molecular biological observations as well as observations with high-risk human populations.

Challenges to the formulation of a theory for the origin of ovarian epithelial tumors

1) Morphological arguments

Ovarian epithelial tumors are composed of cell types not present in normal ovaries

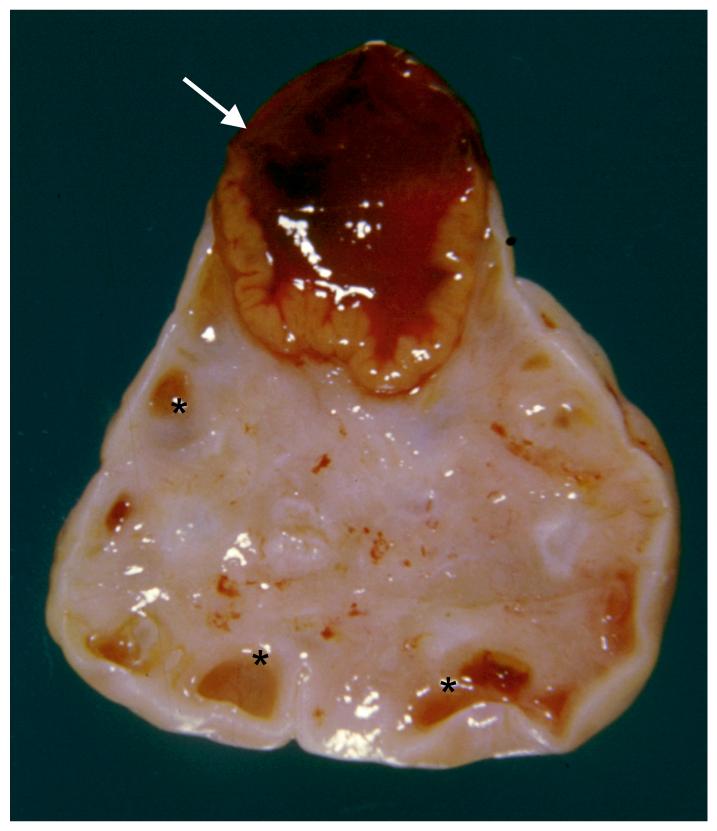

Ovarian epithelial neoplasms are remarkably similar to epithelial cells from extra-ovarian sites in the female reproductive tract. The 3 most common subtypes of these tumors, referred to as serous, endometrioid, and mucinous, are morphologically identical to carcinomas of the fallopian tube, endometrioid, and endocervix respectively. None of the normal cellular constituents of the ovary resemble any of these organs, hence the dilemma as to where epithelial tumors actually arise. Figure 1 shows a normal ovary with macroscopic features characteristic of fertility including a corpus luteum (arrow) still bulging from the ovarian surface as well as several developing follicles (asterisks). The remaining elements of normal ovaries are microscopic and include germ cells surrounded by primordial follicular cells scattered in the ovarian stroma as well as androgen-secreting cells known as hilar cells. The entire organ is covered by mesothelium. None of the normal ovarian constituents are lined with epithelial cells resembling those lining the fallopian tube, endometrium, or endocervix.

Figure 1. Constituents of normal ovaries.

The cut surface of an ovary sectioned through a corpus luteum (arrow) and also containing smaller follicles (asterisks) is shown. (Courtesy of Dr. Nancy E. Warner).

Ovarian epithelial tumors arise in cystic structures not present in normal ovaries

Ovarian epithelial tumors are frequently enclosed within epithelial cysts that have no normal ovarian counterpart. Almost all mucinous ovarian tumors, benign and malignant, are cystic. Although some poorly differentiated serous carcinomas may only show solid components, a cystic component is present in a large proportion. All benign serous ovarian tumors are cystic. As it turns out, microscopic cysts are frequently present within the ovary, but their origin is controversial and they are currently regarded as pathological. Cysts that are less than 1 cm in diameter are often lined by a cell layer resembling the coelomic epithelium on the ovarian surface, hence the idea that they are derived from cortical invaginations entrapped within the ovarian parenchyma. Such cysts are often referred to as inclusion cysts. The ovary can also harbor another type of cyst of greater interest to the issue of the cell of origin of ovarian epithelial tumors because similarly to these tumors, they are lined by epithelial cells identical to those lining the fallopian tube, endometrium, or endocervix. These cysts are often called metaplastic cysts because of the notion that they may represent cortical inclusion cysts that re-programmed their differentiation via a process known as metaplasia. Such metaplastic cysts are considered neoplastic by convention when they become larger than 1 cm, at which point they are named either serous cystadenomas (if lined by epithelial cells resembling those in fallopian tubes), endometriomas (if lined by epithelial cells resembling those in endometrial glands), or mucinous cystadenomas (if lined by epithelial cells resembling those in endocervix). These lesions are regarded as the benign counterparts of serous, endometrioid, and mucinous ovarian carcinomas respectively.

Tumors identical to ovarian epithelial neoplasms can originate outside the ovary

Benign ovarian epithelial-like tumors are at least as frequent outside the ovary (para-tubal and para-ovarian cystadenomas) as they are within this organ. In addition, malignant tumors that are histologically and clinically identical to ovarian carcinomas may be seen outside the ovary and may develop in individuals in whom the ovaries were removed several years previously and for reasons other than cancer2-5. Women with familial ovarian carcinoma predisposition due to germline mutations in either BRCA1 or BRCA2 continue to be at an increased risk of developing serous extra-ovarian carcinomas (usually referred to as primary peritoneal carcinomas) after undergoing prophylactic salpingo oophorectomies6-8.

2) Embryological arguments

Embryological notions that led to the idea that ovarian epithelial tumors arise in the ovarian surface are no longer valid

It was once believed, in the early part of the twentieth century, that the cell layer that lines the ovarian surface (ovarian coelomic epithelium) was made up of pluripotent cells from which all cell types found within the adult ovarian cortex, including germ cells and follicular cells, were derived9,10. It is for this reason that this cell layer was named germinal epithelium11, a name that continues to be used today. It is now well established that germ cells do not originate in the coelomic epithelium12 and although the exact origin of ovarian follicular cells continues to be debated, there are strong morphological, functional, and molecular arguments that they are of mesonephric origin13.

The embryological derivation of ovarian epithelial tumors is unrelated to that of the ovary

The various tissues to which ovarian epithelial tumors resemble, including the lining of fallopian tubes, endometrium, and endocervix, share a common embryological origin notably unrelated to that of the ovary. They are derived from embryological structures called mullerian (also called paramesonephric) ducts, which first develop as a pair medial to the mesonephric ducts early during fetal development. Similar ducts do not develop in males because secretion of mullerian inhibiting substance (MIS) by the testes prevents their formation14. The two mullerian ducts eventually fuse in their distal portion to become the upper third of the vagina, cervix, and body of the uterus. The proximal segments remain unfused and become the fallopian tubes. The lower two thirds of the vagina develop from an invagination of the skin that eventually connects to the mullerian ducts. The stratified epithelium that lines the lower vagina eventually expands upward, pushing its boundary with mullerian epithelium, which marks the transition between endo- and exo-cervix in mature individuals.

It is surprising that tumors currently regarded as of primary ovarian origin would resemble tumors derived from various segments of the mullerian tract in spite of the fact that the ovary is not embryologically related to this tract. The early development of this organ is similar to that of the testes. There is no difference noted between the ovaries and testes when the germ cells first enter the gonads, at which point the gonads are referred to as undifferentiated15. Although male mice carrying a constitutional gene knockout of mullerian inhibiting substance develop a uterus with attached fallopian tubes and cervix due to failure of regression of the mullerian ducts, they do not develop ovaries16, further attesting to the lack of relationship between the ovaries to these ducts.

3) Molecular biological arguments

The notion that ovarian epithelial tumors resemble tumors derived from the mullerian tract is supported by more than mere morphological arguments. Cheng et al17. studied the expression status of genes involved in body segmentation and morphogenesis in different components of the female reproductive tract. Expression of individual members of this gene family, called HOX genes, is highly specific for different body segments including segments of the reproductive tract. These authors found that serous, endometrioid, and mucinous ovarian carcinomas expressed the same set of HOX genes as epithelial cells from normal fallopian tube, endometrium, and endocervix respectively17. These results are highly supportive of the idea that these different ovarian tumor subtypes originate in mullerian epithelium as opposed to coelomic epithelium.

The coelomic metaplasia hypothesis

The idea that ovarian epithelial tumors arise from the portion of the coelomic epithelium that lines the ovarian surface is still favored by many. Proponents of this theory account for the mullerian appearance of ovarian tumors by stipulating that the coelomic epithelium is not the direct precursor of ovarian tumors, but must first change into mullerian-like epithelium through a process known as metaplasia. It is further hypothesized that this scenario of metaplasia followed by neoplastic transformation is most likely to happen in portions of the coelomic epithelium that have invaginated within the hormone-rich ovarian parenchyma (cortical inclusion cysts). This theory accounts for the presence of primary peritoneal tumors by stipulating that the hormonal environment in fertile women can trigger mullerian metaplasia in coelomic epithelial cells distant from the ovary just as they do in cells that line the ovarian surface.

The coelomic hypothesis, which is based on embryological arguments that are no longer valid as already pointed out, implies that ovarian carcinomas are better differentiated than the cells from which they originate. This notion is at odds with our current understanding of cancer development. This, plus the fact that no ovarian carcinoma precursor lesion had been defined within the coelomic epithelium in spite of decades of effort, led me to suggest nearly a decade ago that a more likely explanation for the morphological similarities between ovarian carcinomas and tumors arising in the mullerian tract is that lesions that are currently classified as ovarian epithelial tumors do not arise from the ovary itself, but from derivatives of the mullerian tract.

Potential sites of origin of ovarian epithelial tumors within the mullerian tract

1) Fallopian tube fimbriae

The fimbriated end of the fallopian tube is an obvious mullerian site from which some tumors currently classified as primary ovarian could originate. This notion is not novel, as pathologists have acknowledged for several decades that many lesions diagnosed as primary serous ovarian tumors are in fact of fallopian tube origin. The morphology of the malignant neoplasms that allegedly arise from these two adjacent organs are so similar that it is usually impossible to tell them apart. It is by pure convention that serous tumors from the tubo-ovarian area are categorized as ovarian except in rare situations when tubal tumors spare the ovary. There is little doubt that ovarian carcinomas have been over-diagnosed at the expense of carcinomas of the fallopian tubes (as well as of primary peritoneal origin) given those rigid criteria. Recent reports from several groups that the fimbriated end of the fallopian tubes is a frequent site of pre-neoplastic changes such as dysplasia in surgical specimens from women undergoing prophylactic procedures due to genetic predisposition to ovarian cancer suggest that the importance of the fallopian tube in ovarian tumorigenesis is substantially greater than previously appreciated18-21. This has led to the suggestion that the fallopian tube may be the main site of cancer predisposition in BRCA1 mutation carriers22.

An origin from fimbriae cannot account for all tumors currently diagnosed as ovarian carcinoma, even those with serous (fallopian tube-like) differentiation. The reasons are the same ones that led pathologists of the last century to reject this idea and formulate the coelomic metaplasia theory. Not all alleged ovarian carcinomas, including those of serous origin, involve the fallopian tubes. A large proportion develops from cystic structures for which there is no normal counterpart in the fimbriae. The cystic appearance of ovarian epithelial tumors is so frequent that the terms cystadenocarcinoma and carcinoma are used interchangeably by many pathologists when referring to ovarian tumors. Microscopic cancers within small serous intra-ovarian cysts with no connection to the fallopian tubes have been described, providing strong arguments for the notion that not all serous ovarian carcinomas arise in the fallopian tubes23.

A more recent argument against the notion that all serous carcinomas of the tubo-ovarian region originate in the fallopian tube comes from the fact that BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers who undergo prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy continue to be at risk for primary serous peritoneal carcinomas6-8. These tumors are identical to serous ovarian or tubal carcinomas except for the fact they do not involve any of these two organs. Although it has been argued that primary peritoneal tumors are rare and therefore unlikely to account for a large proportion of cancers developing in BRCA1 mutation carriers, these tumors are undoubtedly under diagnosed because of the strict diagnostic criteria that are currently applied. Fallopian tube cancers, which are also subjected to similar rigid criteria, were likewise regarded as extremely rare as recently as a few years ago.

2) Secondary mullerian system

The endocervix, endometrium, and fallopian tubes are not the only sites where epithelial cells derived from the mullerian ducts are found in adults. Microscopic structures lined by mullerian epithelium are extremely common in the para-tubal and para-ovarian areas. They also frequently impinge on the ovarian medulla and can even be seen within the deeper portions of the ovarian cortex. These structures, which have been grouped under the name “secondary mullerian system.”24, might be vestigial remnants of the oviducts, which carry the egg from the ovary to the uterine horns in lower mammals, but this notion remains unverified. They include endosalpingiosis, which is defined as small cystic structures filled with serous fluid and lined by cells similar to those lining the fallopian tubes, endometriosis, defined as endometrial-like glands (with admixed stroma) filled with bloody material outside the endometrium, and endocervicosis, defined as small cysts filled with mucin and lined by cells similar to those lining the endocervix. Thus, the various components of the secondary mullerian system provide a source for all the various cell types that are present in the major subtypes of tub-ovarian epithelial tumors. I suggested earlier1 that the rete ovarii, which is a series of coiled microscopic ducts near the ovarian hilum, could be part of the secondary mullerian system based on the fact that ovarian-like tumors have been described arising from this structure25 and based on evidence from experimental animals26,27. This idea, however, remains untested.

It may seem surprising that structures currently regarded as mere vestigial embryological remnants (although the possibility remains that they have a function in adults) could be the source of an important type of human cancer. Nevertheless, it is clear that endosalpingiosis, endocervicosis, and endometriosis can develop into large extra-ovarian cysts that are morphologically indistinguishable from serous or mucinous ovarian cystadenomas or endometriomas respectively. Extra-ovarian serous and mucinous cystadenomas are so frequent (para-ovarian and para-tubal cystadenomas) that pathologists often do not mention them in surgical pathology reports unless they are large enough to be clinically relevant. It is very likely that this system also gives rise to malignant epithelial tumors, but such tumors are invariably classified as of primary ovarian origin except in rare instances where they do not spread to the ovary, in which case they are diagnosed as primary peritoneal carcinomas.

A unifying hypothesis for the origin of primary ovarian, tubal, and peritoneal carcinomas

Ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal carcinomas are currently regarded as 3 distinct disease entities with identical morphological features. According to this view, primary ovarian tumors arise in the coelomic epithelial cell layer that lines the ovarian surface only after this cell layer changes its differentiation lineage via metaplasia to become mullerian-like. However, normal cells with the same characteristics and belonging to the same cell lineage as ovarian epithelial tumors are abundant in the immediate vicinity of the ovary. The fimbriae literally rub against the ovarian surface at the time of ovulation. They frequently adhere to the ovary as a result of inflammation (tubo-ovarian adhesions). Components of the secondary mullerian system, including endosalpingiosis, endometriosis, and endocervicosis are abundant in the para-ovarian area as well as in the ovarian hilum and medulla. There is therefore no need to invoke a theory whereby a specific cell type must completely change its differentiation lineage before undergoing malignant transformation. It seems much more likely that ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal tumors are all exclusively derived from cells in which features of mullerian differentiation are already present. In fact, the similar clinical characteristics of these tumors suggest that they could be regarded as a single disease entity.

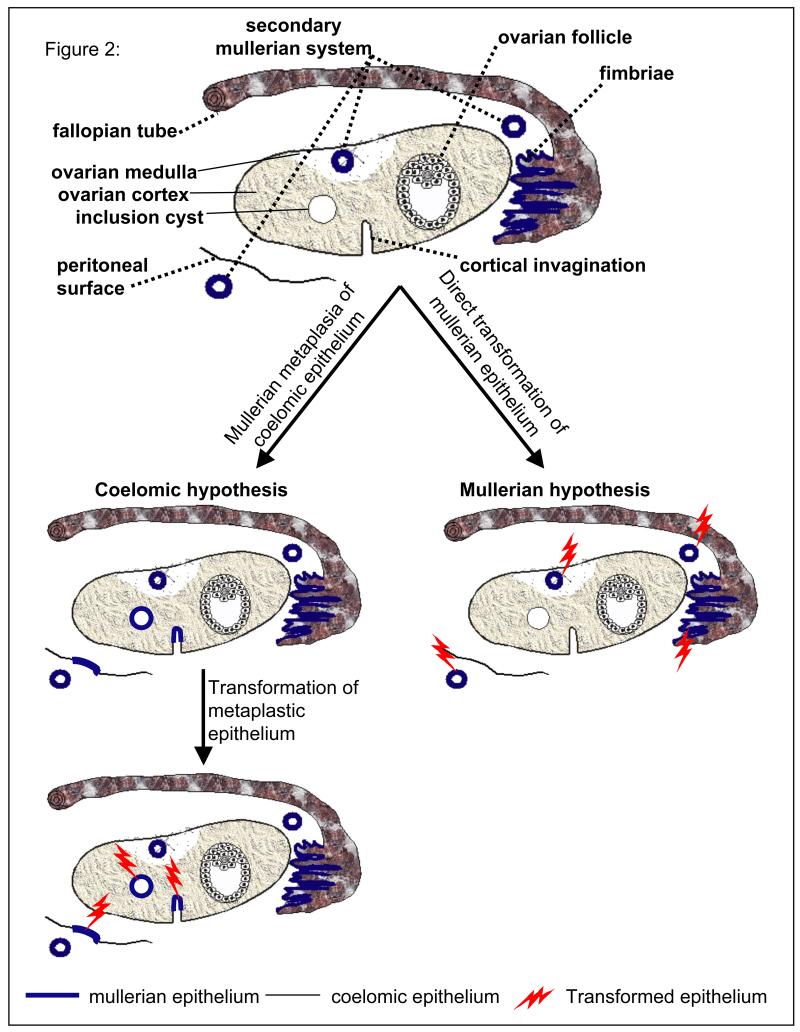

The main elements of this hypothesis are summarized and compared to the coelomic metaplasia hypothesis in figure 2. Cortical invaginations as well as cortical inclusion cysts, which are initially lined by coelomic epithelium (depicted by a thin black line in the illustration), must first undergo metaplasia and change to mullerian-like epithelium (thicker blue lines in Fig. 2) before undergoing malignant transformation (lightening signs in Fig. 2) according to the coelomic hypothesis. Likewise, the coelomic epithelium covering peritoneal surfaces outside the ovary can give rise to primary peritoneal tumors only after undergoing metaplasia to acquire characteristics of mullerian epithelium (Fig. 2). In contrast, no intermediary metaplastic step is necessary with the mullerian hypothesis, which stipulates that mullerian-like tumors arise directly and exclusively from mullerian epithelium that is already present, either in the fimbriae or in components of the secondary mullerian system. Although a small fraction of the tumors currently diagnosed as ovarian do originate within this organ because the secondary mullerian system sometimes extends to the ovarian medulla or even the deeper cortical regions, most originate from mullerian-derived tissues located outside this organ, either in the fimbriated end of fallopian tubes or in the secondary mullerian system. It is the mere fact that these tumors usually spread to the ovary early in their development that accounts for the majority being diagnosed as primary ovarian. Indeed, tubal and primary peritoneal carcinomas, by convention, are only diagnosed in the absence of ovarian involvement. The idea that fallopian tube cancers have been considerably under diagnosed is becoming well accepted in light of reports that this organ is a frequent site of dysplasia in surgical specimens from BRCA1 mutation carriers who underwent prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomies. Likewise and for the same reasons, tumors currently referred to as “primary peritoneal” are probably much more common than currently appreciated. Most cystic tumors from the tubo-ovarian area probably have a secondary mullerian origin, as their cystic features cannot be accounted for by invoking a fimbrial origin.

Figure 2.

The coelomic versus mullerian hypotheses for the origin of ovarian, tubal, and primary peritoneal carcinomas.

Further arguments supporting the notion that ovarian epithelial neoplasms are of mulleri an origin

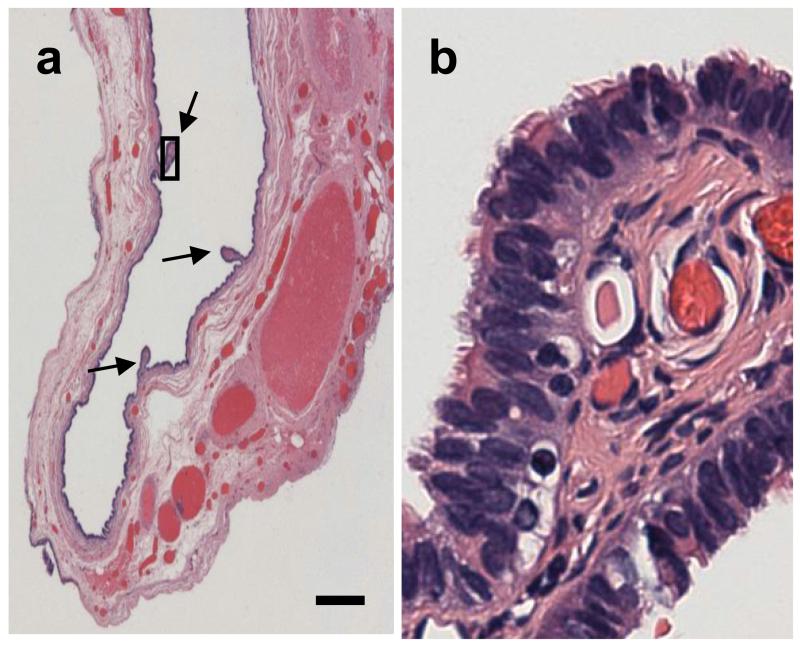

There is extensive epidemiological, histopathological, and molecular biological evidence that endometrioid ovarian carcinomas arise in foci of endometriosis28-33. Thus, the idea that this histological subtype of ovarian carcinoma, which was once believed to originate in the ovarian coelomic epithelium, represents instead malignant transformation of the secondary mullerian system, has some support in the scientific community. As for other subtypes of ovarian epithelial tumors, the mere fact that large benign serous or mucinous tumors resembling serous or mucinous ovarian cystadenomas can be seen outside the ovary strongly suggests that endosalpingiosis and endocervicosis can give rise to ovarian-like neoplasms. A portion of a 1.5 cm serous cyst morphologically identical to ovarian serous cystadenomas but located in the para-tubal area with no direct connection to the ovary is shown in Fig. 3A. The epithelial lining shows small papillae (arrows), oneof which is shown under higher magnification in panel B, revealing the presence of short hair-like structures called ciliae on the surface of the lining epithelial cells, which is characteristic of tubal, but not of coelomic epithelium. Ovarian tumors of low malignant potential have also been described in foci of endosalpingiosis outside the ovaries34. It is not uncommon to see small serous or mucinous carcinomas contiguous to large benign-looking cystadenomas within the same lesions and it has been argued, based on molecular biological evidence, that ovarian cystadenomas can progress to malignancy if certain genetic defects such as a p53 mutation or others are present35. Quddus et al36. reviewed all cases of endosalpingiosis and endometriosis of the omentum from a single institution over a 12-year period. They reported that the endosalpingiosis to endometriosis ratio in this cohort was similar to the ratio of primary peritoneal serous to endometrioid carcinomas, providing support to the idea that these two malignant tumor types are related to these two benign lesions respectively36.

Figure 3. Example of extra-ovarian serous cystadenoma.

The long arrows show papillae. The area within the rectangle is shown under higher magnification in B, revealing a ciliated epithelium. Bar: 300 microns.

Support for the notion that tumors currently classified as ovarian arise in the mullerian tract, whether from fallopian tubes of from the secondary mullerian system, also comes from the well documented observation that destruction of portions of the mullerian tract in the absence of ovarian ablation, either from tubal ligation or hysterectomy, is protective against ovarian cancer37-46. Although pre-neoplastic changes such as dysplasia have so far been found almost exclusively in the fimbriated end of the fallopian tubes in surgical specimens from women undergoing prophylactic procedures , due to familial predisposition to ovarian cancer18-21, it is likely that similar dysplastic lesions would have been found within foci of endosalpingiosis if components of the secondary mullerian system had been examined in addition to the fallopian tubes in these studies.

Observations with animal models can also provide insight into the site of origin of ovarian epithelial tumors. Mice lacking a functional Brca1 in their ovarian granulosa cells, which are part of ovarian follicles and play an important role in menstrual/estrus cycle progression, develop epithelial cysts similar to human ovarian cystadenomas in the ovarian hilum and uterine horns, but not in the ovarian surface47. The human homolog of this protein, BRCA1, controls familial predisposition to ovarian, tubal, primary peritoneal, and breast carcinoma. The fact that such cell-specific Brca1 inactivation mediates epithelial proliferation in the mullerian tract not only raises interesting possibilities regarding the well-established link between menstrual cycle activity and ovarian cancer risk, but also further supports a mullerian origin for ovarian epithelial tumors.

Concluding remarks

The arguments summarized in this article do not constitute an absolute proof, but are strongly supportive of the notion that tumors currently classified as primary ovarian or peritoneal have a mullerian as opposed to coelomic origin. The terms “ovarian carcinoma” and “primary peritoneal carcinoma” are misleading if these tumors do not arise from either the ovarian parenchyma proper or from the peritoneum. Even the term “fallopian tube carcinoma” is not entirely accurate because the current evidence suggests that it is only the cells that cover the fimbriae, which are outside the tube, that are at risk of malignant transformation in BRCA1 mutation carriers. I suggest that the term “extra-uterine mullerian” cystadenomas or carcinomas, further subdivided into histological subtypes such as serous, endometrioid, mucinous, and others, be applied to all mullerian tumors of the tubo-ovarian region in order to better convey their similarities and origin.

Regardless of mere terminology, acknowledgement of a mullerian origin for tubo-ovarian epithelial neoplasms should have important implications on future research directions as well as patient management. Efforts to define the precursor lesion of these tumors, which are imperative to the development of screening protocols aimed at their early detection, should be re-focused on the extra-uterine mullerian system. Strategies aimed at developing expression profile panels of potential utility for either early disease detection or prognostication, which have so far been largely based on comparing profiles of tumor cells to that of normal coelomic epithelium, should be based instead on comparisons to normal mullerian epithelium. The notion that tubo-ovarian tumors are of mullerian origin should also stimulate studies of the normal biology of specific components of the extra-uterine mullerian system such as the fimbriae, about which very little is currently known. This would likely lead to a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying disease risk factors, which in turn could lead to the development of better strategies for cancer prevention. Finally, knowledge of the exact tissue of origin of tubo-ovarian epithelial tumors has important implications for prophylactic surgical procedures performed in patients with familial cancer predisposition. For example, procedures sparing portions of the ovarian cortex might be considered in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers wanting to preserve their fertility.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I thank my colleagues, Anna Wu and Malcolm Pike from USC, for their critical review of the manuscript. This work was supported by Grant # R01CA119078 from the US National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dubeau L. The cell of origin of ovarian epithelial tumors and the ovarian surface epithelium dogma: does the emperor have no clothes? Gynecol Oncol. 1999;72:437–442. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1998.5275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altaras MM, Aviram R, Cohen I, Cordoba M, Weiss E, Beyth Y. Primary peritoneal papillary serous adenocarcinoma: clinical and management aspects. Gynecol Oncol. 1991;40:230–236. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(90)90283-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.August CZ, Mu rad TM, Newton M. Multiple focal extraovarian serous carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1985;4:11–23. doi: 10.1097/00004347-198501000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dalrymple JC, Bannatyne P, Russell P, et al. Extraovarian peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma. Cancer. 1989;64:110–115. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890701)64:1<110::aid-cncr2820640120>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fromm G-L, Gershenson DM, Silva EG. Papillary serous carcinoma of the peritoneum. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:89–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finch A, Beiner M, Lubinski J, et al. Salpingo-oophorectomy and the risk of ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal cancers in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 Mutation. JAMA. 2006;296:185–192. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levine DA, Argenta PA, Yee CJ, et al. Fallopian tube and primary peritoneal carcinomas associated with BRCA mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4222–4227. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olivier RI, van Beurden M, Lubsen MA, Rookus MA, Mooij TM, van de Vijver MJ, va n’t Veer LJ. Clinical outcome of prophylactic oophorectomy in BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers and events during follow-up. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1492–1497. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gillman J. The development of the gonads in man with a consideration of the role of fetal endocrines and the histogenesis of ovarian tumors. Contrib Embryol Carneg Inst. 1948;32:81–131. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gruenwald P. The development of sex cords in the gonads of man and mammals. Am J Anat. 1942;70:359–397. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen BM. The embryonic development of the ovary and testes o f the mammals. Am J Anat. 1904;3:89–153. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Witschi E. Migration of the germ cells of human embryo from the yolk sac to the primitive gonadal folds. Contr Embryol Carnegie Inst. 1948;32:69–80. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodriguez M, Dubeau L. Ovarian tumor development: insights f rom ovarian embryogenesis. Eur J Gynaec Oncol. 2001;22:175–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Josso N, di Clemente N, Gouedart L. Anti-mullerian hormone and its receptors. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001;179:25–32. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00467-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Byskov AG. Primordial germ cells and regulation of meiosis. In: Austin CR, Short RV, editors. Reprodu ction in mammals. I. Germ cells and fertilization. Cambridge University Press; London: 1982. pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Behringer RR, Finegold MJ, Cate RL. Mullerian-inhibiting substance function during mammalian sexual development. Cell. 1994;79:415–425. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng W, Liu J, Yoshida H, Rosen D, Naora H. Lineage infidelity of epithelial ovarian cancers is controlled by HOX genes that specify regional identity in the reproductive tract. Nat Med. 2005;11:531–537. doi: 10.1038/nm1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colgan TJ, Murphy J, Cole DE, Narod S, Rosen B. Occult carcinoma in prophylactic oophorectomy specimens: prevalence and association with BRCA germline mutation status. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1283–1289. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200110000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leeper K, Garcia R, Swisher E, Goff B, Greer B, Paley P. Pathologic findings i n prophylactic oophorectomy specimens in high-risk women. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;87:52–56. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2002.6779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piek JM, van Diest PJ, Zweemer RP, et al. Dysplastic changes in prophylactically removed Fallopian tubes of women predisposed to developing ovarian cancer. J Pathol. 2001;195:451–456. doi: 10.1002/path.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tonin P, Weber B, Offit K, et al. Frequency of recurrent BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in 222 Ashkenazi Jewish breast cancer families. Nat Med. 1996;2:1179–1183. doi: 10.1038/nm1196-1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crum CP, Drapkin R, Miron A, et al. The distal fallopian tube: a new mode l for pelvic serous carcinogenesis. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19:3–9. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e328011a21f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scully RE. Pathology of ovarian cancer precursors. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 1995;23:208–218. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240590928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lauchlan SC. The secondary mullerian system revisited. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1994;13:73–79. doi: 10.1097/00004347-199401000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rutgers JL, Scully RE. Cysts (cystadenomas) and tumors of the rete ovarii. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1988;7:330–342. doi: 10.1097/00004347-198812000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Byskov AGS. Does the rete ovarii act as a trigger for the onset of meiosis? Nature. 1974;252:396–397. doi: 10.1038/252396a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quattropani SL. Serous cy stadenoma formation in guinea pig ovaries. J Submicrosc Cytol. 1981;13:337–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brinton LA, Gridley G, Persson I, Baron J, Bergqvist A. Cancer risk after a hospital discharge diagnosis of endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:572–579. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70550-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heaps JM, Nieberg RK, Berek JS. Malignant neoplasms arising in endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:1023–1028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ness RB. Endometriosis and ovarian cancer: thoughts on shared pathophysiology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:280–294. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ness RB, Cottreau C. Possib le role of ovarian epithelial inflammation in ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1459–1467. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.17.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prefumo F, Todeschini F, Fulcheri E, Venturini PL. Epithelial abnormalities in cystic ovarian endometriosis. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;84:280–284. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vignali M, Infantino M, Matrone R, et al. Endometriosis: novel etiopathogenetic concepts and clinical perspectives. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:665–678. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)03233-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kadar N, Krumerman M. Possible metaplastic origin of lymph node “metastases” in serous ovarian tumor of low malig nant potential (borderline serous tumor) Gynecol Oncol. 1995;59:394–397. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1995.9955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng JP, Robinson WR, Ehlen T, Yu MC, Dubeau L. Distinction of low grade from high grade human ovarian carcinomas on the basis of losses of heterozygosity on chromosomes 3, 6, an d 11 and HER-2/neu gene amplification. Cancer Res. 1991;51:4045–4051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quddus MR, Sung CJ, Lauchlan SC. Benign and malignant serous and endometrioid epithelium in the omentum. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;75:227–232. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1999.5575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cornelison TL, Natarajan N, Piver MS, Mettlin CJ. Tubal ligation and the risk of ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Detect Prev. 1997;21:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cramer DW, Xu H. Epidemiologic evidence for uterine growth factors in the pathogenesis of ovarian cancer. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5:310–314. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)00098-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Green AC, Purdie DM, Bain CJ, et al. Survey of Women’s Health Group Tubal sterilization, hysterectomy and decreased risk of ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 1997;71:948–951. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970611)71:6<948::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hankinson SE, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, et al. Tubal ligation, hysterectomy, and risk of ovarian cancer. A prospective study. JAMA. 1993;270:2813–2818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Irwin KL, Weiss NS, Lee NC, Peterson HB. Tubal sterilization, hysterectomy, and the subsequent occurrence of epithelial ovarian cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134:362–369. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kreiger N, Sloan M, Cotterchio M, Parsons P. Surgical procedures associated with risk of ovarian cancer. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:710–715. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.4.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Loft A, Lidegaard O, Tabor A. Incidence of ovarian cancer after hysterectomy: a nationwide controlled follow up. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:1296–1301. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb10978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miracle-McMahill HL, Calle EE, Kosinski AS, et al. Tubal ligation and fatal ovarian cancer in a large prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:349–347. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosenblatt KA, Thomas DB. Reduced risk of ovarian cancer in women with a tubal lig ation or hysterectomy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1996;5:933–935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weiss NS, Harlow BL. Why does hysterectomy without bilateral oophorectomy influence the subsequent incidence of ovarian cancer? Am J Epidemiol. 1986;124:856–858. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chodankar R, Kw ang S, Sangiorgi F, et al. Cell-nonautonomous induction of ovarian and uterine serous cystadenomas in mice lacking a functional Brca1 in ovarian granulosa cells. Curr Biol. 2005;15:561–565. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]