Abstract

We previously reported that nanoceria can slow retinal degeneration in the tubby mouse for two weeks by multiple systemic injections. However, the long-term protection of retinal structure and function by directly deliver of nanoceria to the eye had not been explored. In this study, 172 ng of nanoceria in lμl saline (1 mM) were intravitreally injected into tubby P7 pups and assays were performed at P28, P49, P80 and P120. The expression of antioxidant associated genes and photoreceptor-specific genes were significantly up regulated, the mislocalization of rod and cone opsins was decreased, and retinal structure and function were protected. These findings demonstrate that nanoceria can function as catalytic antioxidants in vivo and may be broad spectrum therapeutic agents for multiple types of ocular diseases.

Keywords: tubby mouse, nanoceria, antioxidant, gene expression, retinal degeneration, longevity

Introduction

The Tubby mouse was naturally generated by a splicing mutation in the Tub gene [1, 2]. It exhibits early and rapid retinal and cochlear degeneration, maturity onset of obesity, resistance to insulin and gradual reduction of fertility. These characteristics are similar to those of human Usher's syndrome [3, 4]. Our previous study revealed that the photoreceptor degeneration occurs at P14 [5] and cell death peaks at P19 [6]. Almost half of the photoreceptors are dead by P28 and retinal function is undetectable around 2 months of age [5]. As a member of the TUB family, the TUB protein has been suggested to function as a transcription factor and to be involved in protein trafficking [7]. Mutation of the TUB protein results in mislocation of photoreceptor-specific proteins, rhodopsin, arrestin and transducin [5]. Although the mechanism underlying the defect in the Tub gene and photoreceptor cell death is not known, published data suggest that inherited ocular diseases proceed through oxidative stress [8-10]. Excessive amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS) cause photoreceptor cell damage and subsequent cell apoptosis [11]. At present, there are no effective therapies to treat and cure inherited ocular diseases. Classical antioxidant treatments can slow the retinal degeneration but the pharmaceutical longevity is an issue because daily supplementations are needed.

Nanoceria (cerium oxide nanoparticles) have large surface area to volume ratios and form oxygen vacancies which enable them to switch valence states between +3 and +4 with the loss of oxygen and/or its electrons. This allows nanoceria to catalytically and regeneratively scavenge free radicals and destroy the ROS [12-14]. Nanoceria have been shown to decrease the amount of ROS thereby protecting adult rat spinal cord neurons in vitro [15], and down regulate the expression of a biomarker for myofibroblastic cells and prevent the invasion of tumor cells [16]. Our lab previously reported that nanoceria can protect photoreceptor cells from oxidative stress-induced damage in a light damaged albino wild type rat model [17]. In very low density lipoprotein receptor knockout (Vldlr-/-) mice, nanoceria decreased oxidative stress, down regulated vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and caused the regression of existing intraretinal and subretinal neovascularizations [18]. In tubby mice, by regulating cell survival/apoptosis signal transduction pathways, nanoceria delayed photoreceptor degeneration and protected retinal function for up to 2 weeks following systemic (intracardial) administration [19]. However, pharmaceutical benefits of nanoceria over extended times had not been investigated. Also, because site-specific targeted delivery can be most effective and provide maximum benefits for pharmaceutical agents, we chose intravitreal injection, which is one of the preferred strategies for ocular delivery of therapeutic materials [20].

In this study, tubby pups at P7 were intravitreally injected with 1 μl of 1 mM nanoceria and the efficacy of nanoceria was determined by preservation of photoreceptor cells, expression of genes associated with oxidative stress and antioxidant defense, and by evaluating the proper localization of photoreceptor-specific proteins at P28, P49,P80 and P120.

Materials and Methods

Animals and genotyping

Tubby mutant mice (tub/tub) in C57BL/6J background were purchased from Jackson laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and used to start the colony. The breeder mating and genotyping are the same as previously reported [5]. All animal procedures followed protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center and the Dean McGee Eye Institute, and the ARVO statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Visual Research.

Synthesis of nanoceria

Cerium oxide nanoparticles (nanoceria) were synthesized the same way as reported previously [18]. Briefly, cerium nitrate (99.999% from Sigma Aldrich) was dissolved in pure water. The solution was oxidized with hydrogen peroxide. After the synthesis of nanoparticles, the pH of the solution was adjusted to 3.4 using nitric acid (1N) to keep the synthesized nanoceria in suspension. The diameter of nanoceria is 3 ∼ 5 nm. Nanoceria can be kept at room temperature for several years without changes in their effectiveness [21]. When used, nanoceria were diluted to the required concentration with saline.

Intravitreal injection

Tubby pups at P7 were cold-anesthetized by incubation on ice for 1∼2 minutes [22]. The eyelid was cut and a puncture on the sclera was made with a 30 gauge needle. A 34 gauge needle attached to a 10 μl syringe of a Nanofil® injection system (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) was inserted into the puncture and 1 μl of either saline or 1 mM nanoceria (172 ng) in saline was delivered into the vitreous under an operating microscope (Carl Zeiss Surgical Inc., NY). The needle was kept in place for 30 seconds to allow complete delivery and the cut eyelid was returned to its original position. The pups were kept on a warming plate until fully awake, returned to their parents and maintained under standard conditions until the scheduled assay time points. Any mice that developed cataracts or had small eyes as a result of the injection were removed from the study.

Electroretinography (ERG)

Full field ERG was performed using an LKC diagnosis system as previously reported [22]. Briefly, mice from four groups (wild type (wt/wt), tub/tub injected with nanoceria or saline and uninjected tub/tub) at P28, P49, P80 and P120 were dark adapted over night. After being anesthetized, the eyes were dilated and the whiskers were trimmed. The responses of rods and cones to the light stimulant were recorded in a getzfield (EPIC-2000, LKC Technologies, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA) with a pair of 3 mm gold electrodes placed on the surface of the cornea. Electrodes hooked in the tail and cheek served as ground and reference electrodes respectively. Scotopic ERGs were recorded using a single flash light at a stimulus intensity of 600 mcd s/m2; Photopic ERGs were recorded using a single flash light of an intensity of 1000 mcd s/m2 after 5 minutes of light exposure at 100 mcd s/m2.

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis and PCR array

3 ∼ 4 pairs of retinas from each group (tub/tub injected with nanoceria or saline, uninjected tub/tub and wt/wt) were collected at P28 for PCR array. Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Inc. Carlsbad, CA) and cDNA was subsequently reverse transcribed using 2 μg of total RNA according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen Inc. Carlsbad, CA). Final volume of RNA is 111 μ1 PCR array was carried out in a single-color icycler machine (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using mouse “oxidative stress and antioxidant defense” array plates and SYBR green master mix in a 25 μl reaction volume according to the manufacturer's protocol (SABiosciences, Frederick, MD). The changes in gene expression in nanoceria injected retinas are shown as fold changes compared to uninjected tub/tub samples and P value was indicated using the array software (SABiosciences, Frederick, MD).

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) and semi-quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis were performed as described above using 3 ∼ 5 retinas from each group. qRT-PCR was carried out in a 20 μl reaction volume containing 20 ng cDNA with SYBR green mix (SABiosciences, Frederick, MD). Gene expression was calculated against the house-keeping gene (GAPDH) and is shown as relative expression level using the 2-ΔCt method [23]. Primer sequences for rod opsin (rhodopsin), cone middle wave-length opsin (M-opsin) are the same as previously reported [24]; Primers for cone short wave-length opsin (S-opsin), arrestin, α-transducin, Rds (Peripherin/rds, or prph/rds, or Prph2) are the same as previously reported [25]; Primers for caspase 3 are the same as previously reported [19]. NF-E2-related factor-2 (Nrf2) expression was detected by semi-quantitative RT-PCR using GAPDH as a control gene [5, 19]. The primer sequences for Nrf2 are: forward primer, 5′-CCTCGCTGGAAAAAGAAGTG, reverse primer 5′- CCGTCCAGGAGTTCAGAGAG Data are shown as mean ± SD.

Western blot

Western blots were performed using 3 ∼ 7 retinas from each group according to our published protocol [18, 19]. Individual retinas were homogenized on ice, centrifuged and after quantification, 40 μg of soluble proteins were loaded on a 12% SDS-page gel and electrophoresed. The gel was electrophoretically transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane [18, 19]. The membrane was blocked in 5% BSA, then probed with the following antibodies: monoclonal anti-rhodopsin (R1D4) (1:10,000, generous gift from Dr. Robert Molday, University of British Columbia, Canada), polyclonal anti-S-opsin (1:1,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and anti-M-opsin (1: 1000, Chemicon International), monoclonal anti-rod arrestin (1:5,000, Paul Hargrave), polyclonal anti-α-transducin (1:1,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), polyclonal anti-caspase 3 (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), and monoclonal anti-β-actin (1:10,000, Abcam, Cambridge, MA). The bands were detected with an ECL system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, UK) after incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5,000, Amersham Biosciences (GE Healthcare), Buckinghamshire, UK) and imaged using a Kodak Image Station 4000R with Kodak MI software.

Light microscopy and quantitative histology

Eyes were marked with green dye on the superior cornea, enucleated and fixed in Perfix at 4°C for at least 24 hours as previously reported [17, 26]. They were embedded in paraffin after being dehydrated through a series of ethanol solutions using an automated tissue processor. Paraffin sections of 5 μm were cut and stained with hematoxylineosin (H&E), coverslipped, observed and imaged using a Nikon Eclipse 800 microscope. All light microscopic images were obtained at a fixed position (from superior-hemisphere sections of the retina at a distance of 1.2 mm from the optic nerve head (ONH)) using a 40× lens. Outer nuclear layer (ONL) thickness was measured superiorly and inferiorly at eleven points of each side under 60× with the first point at a distance of 0.16 mm from the ONH. Similarly, the thickness of outer segment (OS) plus inner segment (IS) was measured at four points on each side of the ONH under 60× with the first value recorded at a distance of 0.32 mm from the ONH. Light images of OS+IS were taken at superior-hemisphere sections at a distance of 0.8 mm to the ONH using a 60× lens. For each treatment and each time point, 4 ∼ 8 eyes were analyzed and data are shown as mean ± SD.

Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemistry was performed as previously reported [22]. Briefly, eyes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at room temperature for 1 hour. After the cornea and lens were removed, the eyes were cryo-protected with 15% and 30% sucrose in 1×PBS for 1 hour each. Individual eyecups were embedded in OCT media (Sakura Finetek USA, Inc., Torrance, CA) and frozen over liquid nitrogen. Cryosections of 10 μm in thickness were cut with a cryostat (Leica, Japan) and collected on pre-cleaned Superfrostplus microscope slides (Fisher Scientific). The slides were blocked with 5% BSA in l×PBS buffer and then incubated with primary antibodies (anti-rhodopsin antibody R1D4, 1:1,000; anti-M-opsin antibody, 1:500; anti-S-opsin antibody, 1:500; anti-arrestin antibody, 1:1,000). After rinsing 3 times in PBS buffer at room temperature for 15 min each, the slides were incubated in secondary antibody conjugated with AlexaFluor 488 anti-mouse IgG or AlexaFluor 596 anti-rabbit IgG. Slides were coverslipped and imaged under a Nikon Eclipse 800 fluorescence microscope using a 40× lens.

Statistical analysis

Data from quantitative histology and ERG were statistically analyzed using the two tailed unpaired student t-test. For RT-PCR data, the one tailed unpaired student t-test was used. P value of less than 0.05 (P<0.05) was considered to be significant.

Results

In this study we performed a single intravitreal injection of nanoceria in saline into P7 tub/tub pups. To test for any retinal toxicity caused by the injection procedure and any benefit gained from saline, we injected the wt/wt P7 pups with 1 μl saline or 1 mM nanoceria in 1 μl saline. Scotopic and photopic ERGs and retinal histology were performed at post injection (PI) day 30 and compared with age-matched uninjected wt/wt mice. The data (Supplementary Fig. 1) indicate that saline injections do not cause any positive or negative changes in retinal structure and function in wt/wt mice. But saline injection does cause a decline in the light response in the tub/tub mutant eyes (See below). We think that the mutant retina is more fragile than the wt/wt retina and the recovery of retinal function needs to overcome the deleterious effects from intravitreal injection damage in addition to overcoming the degenerative effects of the Tub gene mutation.

The expression of oxidative stress-associated genes

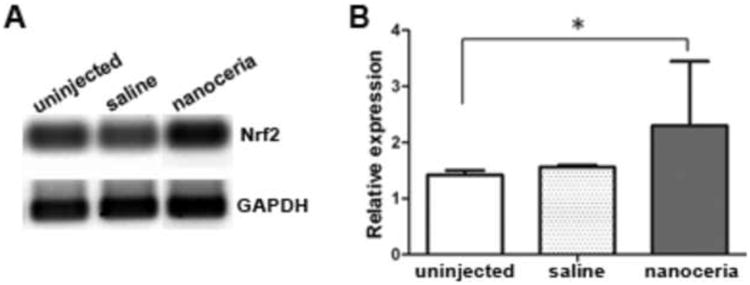

The wt photoreceptors reach their full development at P28, so P28 retinas from nanoceria treated, saline treated, untreated tub/tub mutant and wt/wt mice were used for PCR array analysis to survey the expression of genes associated with oxidative stress and antioxidant defense. The changes in gene activity caused by nanoceria are shown as fold changes compared to the same gene expressed in age-matched uninjected tub/tub mutant retinas (CeO2/tubby). In keeping with the published data in the literature, we decided that changes above the threshold of 1.5 fold were considered to be large. Data with P values are summarized in Table 1. Genes associated with products of antioxidants including glutathione reductase (Gsr), nudix (nucleoside diphosphate linked moiety X)-type motif 15 (Nudt15), peroxiredoxin 6 related sequence 1 (Prdx 6-rs1), prion protein (Prnp), superoxide dismutase 2, mitochondrial (Sod2), superoxide dismutase 3, extracellular (Sod3), thioredoxin reductase 1 (Trnrd1), thioredoxin reductase 2 (Trnrd2) and uncoupling protein 3 (mitochondrial proton carrier (Ucp3)) were upregulated by nanoceria treatment. However, another group of genes including glutathione peroxidase 1 (Gpx1), NAD(P)H dehydrogenase, quinine 1 (Nqo1), nucleoredoxin (Nxn), peroxiredoxin (Prdx)2, Prdx3, Prdx4, superoxide dismutase 1, soluble (Sod1), thyroid peroxidase (Tpo), etc, having a similar function, were down regulated. Genes associated with cellular protection (Tmod1, tropomodulin 1), prevention of DNA damage and involved with DNA repair (Als2, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis 2 (juvenile) homolog (human); Ercc6, excision repair cross-complementing rodent repair deficiency, complementation group 6), Ca2+ handling (Mpp4, membrane protein, palmitoylated 4 (MAGUK p55 subfamily member 4)), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) activation (Gab1, growth factor receptor bound protein 2-associated protein 1), and endocytosis pathway (Ehd2, EH-domain containing 2) were also elevated. We had shown that Nrf2 decreased in tubby mutant retina, and nanoceria treatment significantly up regulated its expression at the protein levels [19]. Our semi-quantitative RT-PCR data demonstrate that intravitreal injection with nanoceria significantly elevates the Nrf2 mRNA level (Fig. 1). Nrf2 is known to be involved in mediating anti-oxidative effects and protection against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis signaling pathways [26-31]. Recently, Nrf2 has been suggested to play a central role in regulating the expression of oxidative stress associated genes [32].

Table 1.

Mouse oxidative stress and antioxidant defense genes with statistically significant changes in expression in tubby mice (≥1.5 fold) before and after nanoceria treatment.

| Symbol | Gene name | tubby/wt | CeO2/tubby | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| antioxidants | fold | P value | fold | P value | |

| Gsr | Glutathione reductase | -1.78 | 0.3517 | 3.38 | 0.0646 |

| Nudt15 | Nudix (nucleoside diphosphate linked moiety X)-type motif 15 | -3.69 | 0.0016** | 1.74 | 0.0267* |

| Prdx6-rsl | Peroxiredoxin 6, related sequence 1 | 3.02 | 0.1567 | 3.45 | 0.0272* |

| Prnp | Prion protein | -1.08 | 0.9767 | 3.59 | 0.0145* |

| Sod2 | Superoxide dismutase 2, mitochondrial | -1.83 | 0.3549 | 2.21 | 0.2043 |

| Sod3 | Superoxide dismutase 3, extracellular | 2.32 | 0.0590 | 2.75 | 0.0840 |

| Txnrd1 | Thioredoxin reductase 1 | -1.25 | 0.9465 | 3.82 | 0.0595 |

| Txnrd2 | Thioredoxin reductase 2 | 1.61 | 0.3474 | 2.68 | 0.1219 |

| Ucp3 | Uncoupling protein 3 (mitochondrial, proton carrier) | -1.61 | 0.1120 | 1.62 | 0.0924 |

| Als2 | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis 2 (juvenile) homolog (human) | -2.47 | 0.0035** | 1.91 | 0.0801 |

| Ercc6 | Excision repair cross-complementing rodent repair deficiency, complementation group 6 | -9.54 | 0.0399* | 5.47 | 0.2461 |

| Gab1 | Growth factor receptor bound protein 2-associated protein 1 | -2.44 | 0.0335* | 2.74 | 0.0408* |

| Ehd2 | EH-domain containing 2 | 1.46 | 0.5039 | 1.71 | 0.4292 |

| Mpp4 | Membrane protein, palmitoylated 4 (MAGUK p55 subfamily member 4) | 1.28 | 0.6852 | 1.74 | 0.1476 |

| Tmod1 | Tropomodulin 1 | 1.54 | 0.4610 | 3.01 | 0.0586 |

| Gpx1 | Glutathione peroxidase 1 | 1.02 | 0.7733 | -1.60 | 0.1565 |

| Nqo1 | NAD(P)H dehydrogenase, quinone 1 | 2.15 | 0.0425* | -1.86 | 0.0646 |

| Nxn | Nucleoredoxin | 1.04 | 0.7771 | -2.22 | 0.1040 |

| Prdx2 | Peroxiredoxin 2 | 1.77 | 0.0406* | -2.07 | 0.0365* |

| Prdx3 | Peroxiredoxin 3 | -1.47 | 0.4728 | -1.61 | 0.2915 |

| Prdx4 | Peroxiredoxin 4 | 1.38 | 0.2246 | -2.47 | 0.0412* |

| Sod1 | Superoxide dismutase 1, soluble | 1.14 | 0.7661 | -2.86 | 0.0064** |

| Tpo | Thyroid peroxidase | -1.27 | 0.4696 | -1.60 | 0.2135 |

| Ctsb | Cathepsin B | -1.17 | 0.5756 | -1.55 | 0.1347 |

| Gstk1 | Glutathione S-transferase kappa 1 | 1.91 | 0.0473* | -1.90 | 0.0471* |

| Psmb5 | Proteasome (prosome, macropain) subunit, beta type 5 | 1.24 | 0.2689 | -1.77 | 0.0832 |

(N=3∼4),

P<0.05,

P<0.01

Figure 1.

Nrf2 expression level in the tubby retina was increased by nanoceria treatment. Representative semi-quantitative RT-PCR data from 5 independent experiments (A) using retinas from P28 and densitometric analysis of the bands (B) are shown. N=3∼5 retinas from each group. *P<0.05

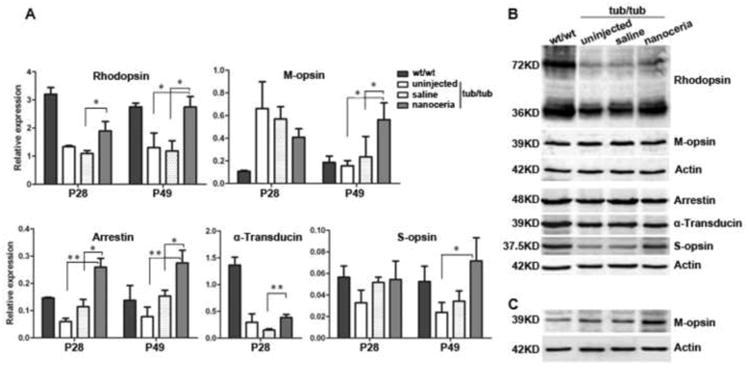

Photoreceptor-specific gene expression and mislocalization of rod and cone opsins

We next analyzed the expression levels of photoreceptor-specific genes in the tub/tub mutant before and after nanoceria treatment using qRT-PCR. Saline injection served as injected control and age-matched wt/wt and uninjected tub/tub mutant mice were used as uninjected controls. As shown in Fig. 2A, at P28 the expression of rhodopsin, S-opsin, arrestin and rod (α) transducin in the tub/tub mutant mice was significantly reduced compared to the wt/wt and declined even more at P49. Surprisingly, M-opsin was significantly elevated 5 fold higher in tub/tub retina than wt/wt at P28 but was equivalent to that which was found in wt/wt at P49 (Fig. 2A). Compared to untreated mutants at P28, nanoceria treatment significantly increased the expression levels of rhodopsin, S-opsin and arrestin by 1.5 fold, 2 fold and 4 fold respectively and reduced M-opsin by 2 fold. There is no significant change in α-transducin levels following nanoceria injection (Fig. 2A). These modulations of gene expression by nanoceria were sustained until P49. These changes were further confirmed by analysis of protein levels by western blots at P28, i.e. the expression levels of these proteins were reduced in the mutant retinas in comparison to the wt/wt retinas and were elevated by nanoceria injection (Fig. 2B). M-opsin protein, similar to its mRNA level, is higher in the mutant than in the wt/wt at P28 (Fig. 2B) and is equivalent to wt/wt/level at P49 (Fig. 2C), whereas nanoceria treatment maintained its level 2∼3 fold higher than the wt/wt level (Fig. 2B, 2C).

Figure 2.

Nanoceria injection alters photoreceptor-specific gene expression at P28 and P49. qRT-PCR analysis of photoreceptor - specific expression of mRNA levels (A) and western blot assay of protein levels (B). Rhodopsin, arrestin, α-transducin and S-opsin are down regulated in the tub/tub compared to the levels in wt/wt. Nanoceria treatment significantly increased the expression of these genes (A). Surprisingly, M-opsin is significantly elevated in the mutant retina at P28, and nanoceria down regulated its expression (A). N=3 ∼ 4 retinas from each group. *P<0.05, **P<0.005. Western blots analysis confirmed the RT-PCR results (C). N=3 ∼ 8 retinas from each group.

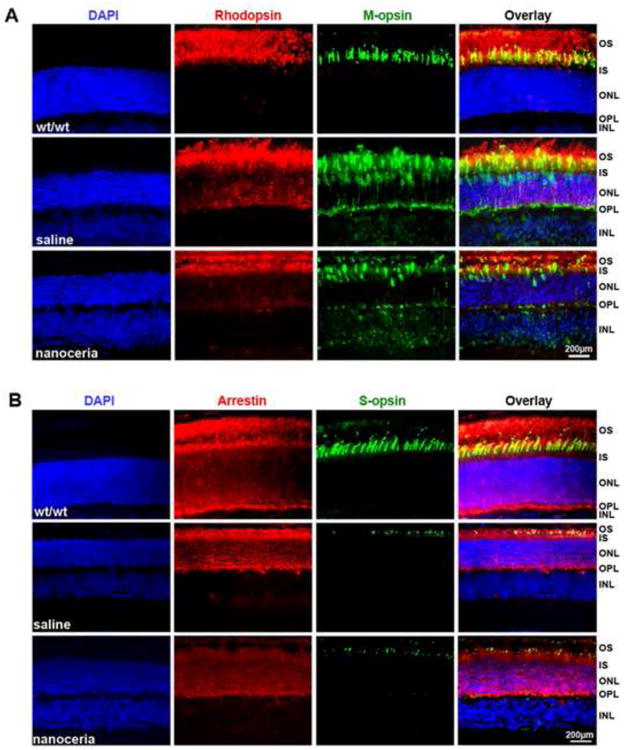

Our lab had previously reported that rhodopsin, arrestin and transducin were mislocalized in the tub/tub mutant retina at P18 [5]. In this study, we performed immunocytochemistry with retinal cryosections at P28 to observe the distribution of rod and cone opsins as well as arrestin before and after nanoceria treatment. As shown in Figs. 3A and 3B, rhodopsin, M- and S-opsin are properly localized in the outer segment (OS) of the wt/wt retina, and arrestin is localized primarily in the OS and outer nuclear layer (ONL). However except for S-opsin positive cells which were greatly reduced in number and length the other proteins in the tub/tub retina were localized throughout the ONL, outer plexiform layer (OPL). M-opsin even further localized in the inner nuclear layer (INL) (Fig. 3A). Similar results were also obtained with P49 retina (data not shown). In agreement with the qRT-PCR data, western blot assay showed that the amount of M-opsin in tub/tub retina was much more than that in the wt/wt retina (Fig. 3A, M-opsin panel). Nanoceria treatment greatly reduced the rhodopsin and M-opsin mislocalizations (Fig. 3A, nanoceria panel) but had no effect on the localization of arrestin and S-opsin (Fig. 3B). Saline injection did not cause any significant changes in the distribution of these proteins.

Figure 3.

Photoreceptor-specific proteins are mislocalized in tubby retinas and partially prevented by nanoceria. Immunocytochemistry at P28 reveals that rhodopsin (red) and M-opsin (green), arrestin (red) and S-opsin (green) are properly localized in the OS of wt/wt retina. In the tub/tub retina, with the exception of S-opsin, these proteins are mislocalized throughout the OS, ONL, OPL and INL. Nanoceria injection partially prevented the mislocalization (N=3 ∼ 4 eyes from each group) Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). OS: outer segment, IS: inner segment, ONL: outer nuclear layer, OPL: outer plexiform layer, INL: inner nuclear layer. Scale bar, 200 μm

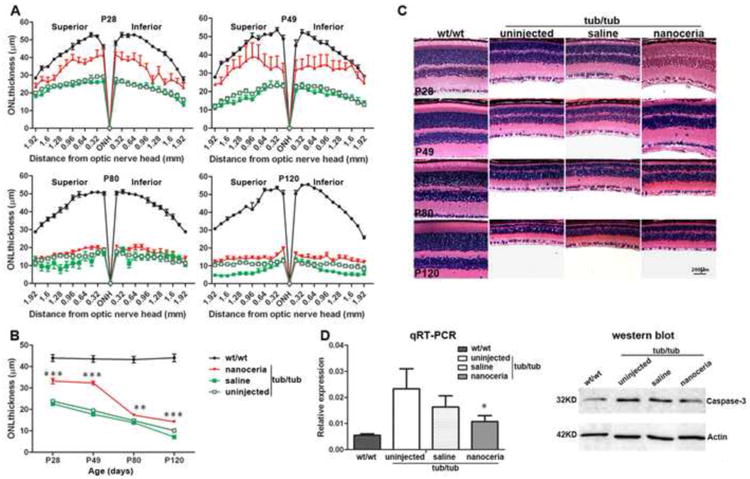

Longevity of photoreceptor survival

Light microscopic observations indicated that the tub/tub mutant exhibits a fast photoreceptor cell degeneration which starts at P14 and peaks between P28 and P34 [5]. At P28, compared to wt/wt retina, the ONL thickness in uninjected tub/tub retina is significantly reduced (P<0.0001) and is 54.3 % of that in wt/wt (23.9 μm in tub/tub vs. 44 μm in wt/wt). In agreement with our previous report [5], saline injection did not cause any significant changes in ONL thickness in the tub/tub retina (22.6 μm in saline injection vs. 23.9 μm in uninjected tub/tub) (P=0.4573). However, nanoceria treatment increased the ONL thickness to 75.5% of that in wt/wt (33.2 μm in nanoceria injection vs. 44 μm in wt/wt), which is 46.9% more than the saline injected eyes (33.2 μm in nanoceria injection vs. 22.6 μm in saline injection) (P<0.0001) (Figs. 4A, 4B, 4C). Further observations at P49 indicated the ONL thickness of tub/tub retina is 45% of wt/wt (19.6 μm in tub/tub vs. 43.6 μm in wt/wt). Similarly, saline injection does not significantly change the ONL thickness compared to the uninjected tub/tub retina (17.6 μm in saline vs. 19.6 μm in tub/tub) (P=0.2455). Nanoceria continued their protective function over time in the tub/tub retina where the ONL thickness is 74.1% of that in wt/wt (Figs. 4A, 4B, 4C) and there is little change compared to P28 (P28: 33.2 μm; P49: 32.3 μm). The ONL of the nanoceria injected eyes is 83.5% thicker than that of the saline injected eyes and is statistically significant (P<0.0001). However at P80, the ONL thickness in nanoceria treated retina is dramatically thinner but still significantly thicker than the uninjected and saline treated control levels. The same result was seen in the P120 retina (Figs. 4A, 4B, 4C).

Figure 4.

Nanoceria provide pan-retinal protection. Quantitative histology (A) using H & E stained retina demonstrated that the protection by nanoceria occurs throughout the retina. Data (B) shown are the average of all the measurements in the same group at 60×. N=66 ∼ 112 measurements in each group from 3 ∼ 6 eyes. ** P<0.005, ***P<0.0001. Representative photomicrographs of H & E stained retinas (C) in the superior hemisphere at 1.2 mm from ONH of wt/wt, tub/tub, saline and nanoceria injected tub/tub retinas at different time points demonstrated that the ONL thickness decreases with age in tub/tub retina and nanoceria treatment inhibits this reduction (C). Caspase-3 expression was significantly reduced in nanoceria treated tub/tub retina compared to uninjected tub/tub retina as reflected in mRNA levels at P28 and protein levels at P49 (D). N=3 ∼ 5 retinas from each group. *P<0.05. RPE: retinal pigment epithelium, OS: outer segment, IS: inner segment, ONL: outer nuclear layer, INL: inner nuclear layer, GCL: ganglion cell layer. Scale bar, 200 μm.

We also determined the expression levels of caspase 3 in P28 retina by qRT-PCR. As demonstrated in Fig. 4D, the mRNA level of caspase 3 in tub/tub retinas exhibits a value more than 4 fold higher than that in wt/wt retina. Saline treatment reduced the caspase 3 level but it is not significantly different from the untreated retina. Nanoceria treatment again significantly reduced the level of caspase 3 expression by 2.5 fold compared to the untreated mutant retina (P<0.05). At P49, caspase 3 protein expression was less in nanoceria treated retina (Fig. 4D).

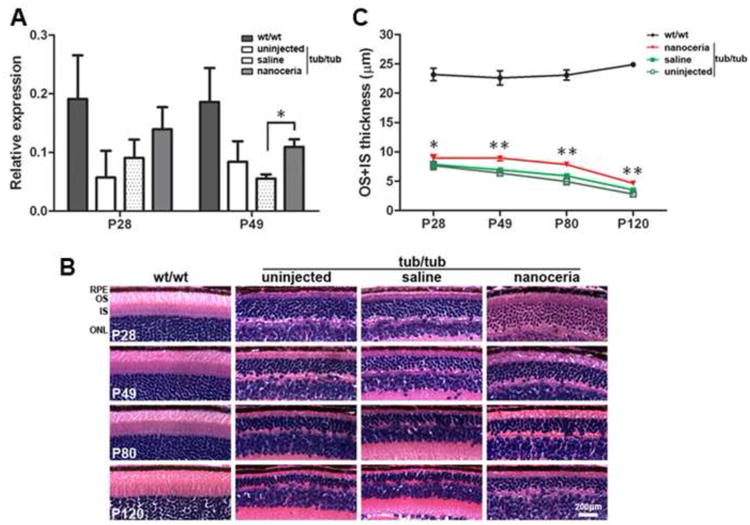

The thickness of outer segment plus inner segment

Phototransduction and visual cycle occurs in the OS [33]. RDS is an important transmembrane structural protein exclusively located in the rim region of the OS discs and is involved in OS disc morphogenesis, orientation, structural stability maintenance and disc renewal [33-35]. To determine the effects of nanoceria on the OS structure and function, Rds expression was examined by qRT-PCR at P28 and P49. As shown in Fig. 5A, Rds mRNA level in P28 tub/tub retina had decreased by more than 4 fold compared to that of the wt/wt and nanoceria treatment resulted in Rds levels 2.5 fold higher than those in the tub/tub retina. This persisted until P49. In the tub/tub mutant retina, the OS and IS are not clearly distinguished by light microscopy (Fig. 5B), so we measured OS+IS thickness on the histological slides superiorly and inferiorly at P28, P49, P80 and P120 (Fig. 5C). The OS+IS thickness in uninjected tub/tub retina is 33.9% of wt/wt at P28, 30.7% at P49, 25.6% at P80 and 14.1% at P120. Saline injection did not alter the OS+IS thickness at any of the time points compared to uninjected tub/tub controls. However, nanoceria injection resulted in significant increases in the thickness of the OS+IS (Fig. 5B, 5C) to 13.9% at P28, 28.7% at P49, 32.4% at P80 and 32.5% at P120, compared to the uninjected or saline injected tubby mutant retinas.

Figure 5.

Nanoceria protect photoreceptors as reflected in the thickness of OS and IS. qRT-PCR analysis of Rds gene expression of mRNA at P28 and P49 (A). N=3 ∼ 5 retinas from each group. *P<0.05. Representative microphotographs of H & E stained retinas (B) at 0.8 mm from the ONH in the superior hemisphere of wt/wt, tub/tub, saline and nanoceria injected tub/tub retinas at different time points demonstrated that the ONL thickness of tub/tub retina gradually decreases with age. Data (C) are the average of all the measurements for both superior and inferior hemisphere of the eyes in the same group at 60×. Nanoceria treatment significantly prevents OS+IS thickness reduction. N=24 ∼ 48 measurements in each group from 3 ∼ 6 eyes. *P<0.05, ** P<0.005. RPE: retinal pigment epithelium, OS: outer segment, IS: inner segment, ONL: outer nuclear layer. Scale bar, 200 μm.

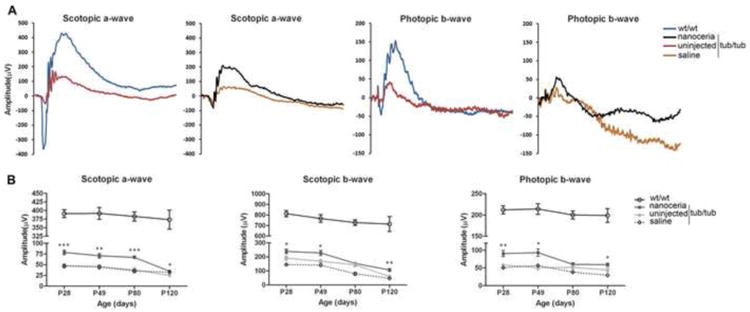

Measurement of retinal function by ERG

Finally, we examined whether the structural preservation of the retina leads to improvement in retinal function. Full field ERG under scotopic and photopic conditions was performed at P28, P49, P80 and P120 to test the responses of rods and cones to light stimulation. As indicated in Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 1, compared to wt/wt mice, tub/tub mice have significantly reduced ERG amplitudes at P28 and they are further reduced at P49. Saline injection caused a decline in ERG amplitudes at both time points compared to the age-matched uninjected mutant controls. However, nanoceria injected eyes showed significantly enhanced retinal functions in both rod and cone ERGs at P28 in comparison with saline injection (P<0.0001 and P=0.0002, respectively) or uninjected mice (P<0.0001 and P=0.0046, respectively). This effect was retained until P49, at which time the amplitudes of both rod and cone ERGs (Fig. 6B) were still significantly different from those of saline (P=0.0004 and P=0.0012, respectively) and uninjected mice (P=0.0005 and P=0.0094, respectively). The scotopic a-wave of nanoceria treated mice at P80 was slightly reduced compared to P28 and P49, and significantly higher than the untreated or saline injected control animals (P<0.0001). The photopic b-wave dropped to the baseline of the uninjected control but remained significantly higher than saline treated eyes (P=0.0009) (Fig. 6B). At P120, the amplitudes of both rod and cone ERGs in the tub/tub mice are still significantly higher than those of the uninjected mutant mice.

Figure 6.

Nanoceria protect retinal function. (A) Scotopic and photopic ERG traces from wt/wt, tub/tub, nanoceriainjected and saline-injected eyes at P28. (B) Nanoceria increased rod responses up to P80 (bottom left) and second neuron responses (Scotopic b-wave, bottom middle). Cone function (bottom, right) was protected through P49. Data shown are mean ± SEM. N= 6 ∼ 24 eyes. *P<0.05, **P<0.005, ***P<0.0001

Discussion

The maintenance of a high concentration of a therapeutic drug for prolonged periods of time is pivotal for providing an effective treatment of any disease. Intravitreal injection, by directly delivering drugs to the target site, can achieve maximum effectiveness and significantly reduce the toxicity and inflammatory side effects [20]. In addition, because of the unique characteristics of the eye such as small size, physical isolation from the rest of the body and a distinct layered structure, only a small amount of reagent is necessary to be exactly delivered to the specific compartment to provide effective therapeutic effects without loss of a significant amount and exposure to the immune surveillance [36]. We previously reported that the systemic (intracardial) administration of nanoceria at P10, P20 and P30 can protect tubby retinal structure and function at P34 by modulation of survival and apoptosis signaling pathways [19]. Here, we further report the long-term effect of nanoceria on retinal structure and function following intravitreal injection. Our data demonstrate that a single injection of 172 ng of nanoceria at P7 can preserve retinal structure and function up to P49 and that gradual loss occurs after P80. At P120, there was improvement in the retinal structure and retinal function was also significantly different from the untreated or saline treated mice.

We have reported that light accelerates retinal degeneration in tubby mice and our data demonstrated the involvement of oxidative stress in this process [5]. Under stress conditions, down regulation of the antioxidant defensive network has been reported in the retina of rd1 [37], tubby [29] and other mutant mice. In this study, we surveyed the expression of a number of oxidative stress and defense genes using PCR arrays and showed that they are differentially regulated by nanoceria treatment, depending on the subcellular location of their proteins in the different compartments of the cell. For example, Sod2 (Superoxide dismutase 2, mitochondrial) is an important antioxidant for scavenging mitochondrial superoxide and deficiency of Sod2 causes all retinal layers to be thinner and causes abnormalities of mitochondrial morphology [38]. Delivery of exogenous human Sod2 gene resulted in a decrease in ganglion cell death and protection of optic nerve fibers from degeneration [39]. Txnrd1 (thioredoxin reductase), located in both cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments, is crucial for reduction/oxidation of thioredoxin and is the central component in the thioredoxin (Trx) system for defense against oxidative stress-induced damage. We have reported that its expression is down-regulated in the tubby retina [26]. Here, our PCR array data demonstrated that they are down-regulated in tubby mice and nanoceria treatment upregulated their expression levels. Whereas Sod1 (Superoxide dismutase 1, soluble), located in the cytosol, is down-regulated in the tubby retina by nanoceria. We think this is because nanoceria themselves have superoxide dismutase activity. We had reported that nanoceria, by intracardial injection, can up regulate phase II enzymes by modulating Nrf2 expression [19]. Similarly, we now show that Nrf2 gene expression is also up regulated in tubby mutant retina by intravitreal injection of nanoceria (Fig. 1). Using ARACNE (algorithm for the reconstruction of accurate cellular networks), CLR (context likelihood of relatedness) and LibSVM software for analysis and prediction combined with microarray data and promoter sequences of Nrf2-regulated gene targets, Taylor et al showed that Nrf2 is a central gene which up regulates multiple downstream antioxidative genes including Nqo1, Prxd1, Sod1, Sod2, Ercc6, Prdx6, Als2, Txnrd2, Park7 and Srxn1 [32]. Our PCR array data demonstrated that nanoceria differentially regulate gene expression with some antioxidant–related genes being up regulated whereas other genes with similar function are down regulated. Nanoceria have been demonstrated to localize inside the nucleus of treated cells [40] and act as direct antioxidants [41], especially mimicking enzymatic activities of superoxide dismutase and catalase [42-44]. We think nanoceria indirectly modulate oxidative stress-associated gene expression by directly decreasing ROS concentrations.

We have previously shown that rhodopsin and arrestin are mislocalized in the tubby retina [5]. In this study, we confirmed that rhodopsin and arrestin are mislocalized. We also showed that M-opsin, but not S-opsin, is mislocalized and nanoceria can partially prevent this. Mislocalization of rhodopsin and cone opsin is a common phenomenon in many ocular diseases [45] and knockout mouse models [46-48]. It is evident that rhodopsin mislocalization in the retina of tulp1 and other mutant mice is an early and primary defect and a major cause of photoreceptor death [48, 49]. One of the TUB family members, TULP1, has been suggested to have a role in rhodopsin trafficking [49]. However, at present, the exact cause of photoreceptor protein mislocalization in tubby mice is unknown. Although there is no clear evidence demonstrating that Tub directly regulates photoreceptorspecific gene expression, our data from immunocytochemistry, RT-PCR and western assays imply that the Tub gene does affect the expression of rod and cone opsins and other phototransduction-associated genes. The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is an important organelle in the cell and regulates protein synthesis, folding, sorting, and Ca2+ homeostasis. Recently, ER stress, a protein folding stress, has been implicated as a causative factor in many neurodegenerative diseases [50-54]. ER stress is tightly linked with oxidative stress [42] and we have shown that oxidative stress is involved in the retinal degeneration in tubby mice [5]. Sato et al reported that S-opsin in Rpe65 deficient mice is incompletely modified during N-glycan processing thus resulting in its mislocalization [55]. Here, the Tub mutation possibly initiates the ER stress and results in the incomplete posttranslational modification of rod and cone opsins which causes these proteins to be misfolded or unfolded and results in improper trafficking of these proteins. Ca2+ is required to be maintained in the ER lumen at a higher level than in the cytoplasm and Ca2+ signals directly contribute to cell survival (see review [56]). A direct effect of ER stress is the depletion of Ca2+ storage and that results in increases in its intracellular level [57]. Table 1 indicates that nanoceria treatment increases the expression of Mpp4, a gene which plays a role in organizing a protein complex which interacts with the Ca2+ extrusion pumps for modulation of Ca2+ homeostasis in the retina [58]. Therefore, nanoceria may also play a role in reducing the protein accumulation or in helping degrade the misfolded/unfolded protein. This possibility is currently under investigation.

For a protective agent to be an effective inhibitor of retinal degeneration, it must preserve significant numbers of functional photoreceptor cells for prolonged periods of time. In this study, we demonstrated that a single intravitreal injection of nanoceria at P7 can protect photoreceptor cell structure and function up to P49, a time frame in which the tubby mutant mice normally lose about 2/3 of photoreceptor cells in the retina (Fig. 4C). The extended survival time of photoreceptors provides an opportunity for the application of other therapeutic strategies to completely rescue or cure the inherited ocular diseases. Such approaches would include the pharmacological treatment of the diseases with other antioxidants or inhibitors targeting signaling pathways and growth factors, or the use of therapeutic genes to replace the defective gene or to modulate the expression of other genes involved in the regulation of the expression of the defective gene. It is also possible, in the case of nanoceria, to provide multiple injections or to use slow release devices which would prolong photoreceptor survival which in turn would preserve vision and increase the quality of life for patients with such diseases [59, 60].

It is interesting that the rod function was retained until P80 which is four weeks longer than the cone function was preserved (P49). The structure of rods and cones are quite different and 95∼97% of photoreceptors are rods whereas only 3∼5% are cones. The rods contain sealed discs which are well-packed inside the cell membrane whereas the cone discs are continuous with the cellular membrane which may distinguish their physiological and biochemical behavior and possibly their ability to take up and retain nanoceria. The uptake and internalization of nanoceria has been studied in vitro and data have shown that nanoceria are internalized via an endocytic processes - either phagocytosis [61] or pinocytosis - which are caveolin- and clathrin-mediated endocytosis [40]). We have shown that ∼80% of nanoceria remain in the retina for up to 4 months after a single intravitreal injection in wild type albino rats (unpublished data). Currently, we don't know how the nanoceria move from the vitreous into the photoreceptors and how they are retained. Experiments to determine if nanoceria are specifically transported by proteins and/or vesicles are currently underway.

Conclusion

Our data demonstrate that a very small amount (172 ng) of nanoceria prolong photoreceptor survival and preserve retinal structure and function in tubby mutant mice for more than a month following a single intravitreal injection in the tubby pups at P7. Our data show that nanoceria, acting as catalytic antioxidants in vivo, can up regulate genes associated with oxidative stress and antioxidant defenses as well as key photoreceptor–specific genes and reduce mislocalization of photoreceptor-specific proteins. These findings suggest that nanoceria may be broad spectrum therapeutic agents effective against a variety of ocular diseases.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. There are no detectable changes in retinal function (A) or structure (B) caused by saline injection in wt/wt mice. Mice were intravitreally injected at P7 with 1 μ1 of saline, visual function was assessed by full field ERG and morphology was evaluated by histology of H & E stained sections at PI-30. N=5 ∼ 7 mice from each group. RPE: retinal pigment epithelium, OS: outer segment, IS: inner segment, ONL: outer nuclear layer, GCL: ganglion cell layer. Scale bar, 200 μm

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the personnel at the Animal, Imaging, and Molecular modules of the Vision Research Core Facility at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center. The authors also thank Jiali Dong for his technical assistance. This study was supported in part by NIH grant COBRE-P20 RR017703, P30-EY12190, R21EY018306, R01EY018724, R01EY02211, FFB C-NP-0707-0404-UOK08. NSF: CBET-0708172 and unrestricted funds from PHF and RPB. JFM is an RPB senior Scientific Investigator.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: Xue Cai, none; Steven A Sezate, none.

Potential conflict of interest: The University of Central Florida and University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center own a patent (US patent: Inhibition of reactive species and protection of mammalian cells (7347987, March 25, 2008)) with JFM and SS listed as inventors. JFM is a cofounder of Nantiox, a startup company licensed to use nanoceria.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kleyn PW, Fan W, Kovats SG, Lee JJ, Pulido JC, Wu Y, et al. Identification and characterization of the mouse obesity gene tubby: a member of a novel gene family. Cell. 1996;85:281–90. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noben-Trauth K, Naggert JK, North MA, Nishina PM. A candidate gene for the mouse mutation tubby. Nature. 1996;380:534–8. doi: 10.1038/380534a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heckenlively JR, Chang B, Erway LC, Peng C, Hawes NL, Hageman GS, et al. Mouse model for Usher syndrome: linkage mapping suggests homology to Usher type I reported at human chromosome 11p15. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:11100–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohlemiller KK, Hughes RM, Mosinger-Ogilvie J, Speck JD, Grosof DH, Silverman MS. Cochlear and retinal degeneration in the tubby mouse. Neuroreport. 1995;6:845–9. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199504190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kong L, Li F, Soleman CE, Li S, Elias RV, Zhou X, et al. Bright cyclic light accelerates photoreceptor cell degeneration in tubby mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;21:468–77. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bode C, Wolfrum U. Caspase-3 inhibitor reduces apototic photoreceptor cell death during inherited retinal degeneration in tubby mice. Mol Vis. 2003;9:144–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cantley LC. Transcription. Translocating tubby. Science. 2001;292:2019–21. doi: 10.1126/science.1062796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohia SE, Opere CA, Leday AM. Pharmacological consequences of oxidative stress in ocular tissues. Mutat Res. 2005;579:22–36. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beatty S, Koh H, Phil M, Henson D, Boulton M. The role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Surv Ophthalmol. 2000;45:115–34. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(00)00140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hollyfield JG. Age-related macular degeneration: the molecular link between oxidative damage, tissue-specific inflammation and outer retinal disease: the Proctor lecture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:1275–81. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halliwell B. Oxidative stress and neurodegeneration: where are we now? J Neurochem. 2006;97:1634–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karakoti A, Singh S, Dowding JM, Seal S, Self WT. Redox-active radical scavenging nanomaterials. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:4422–32. doi: 10.1039/b919677n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karakoti AS, Monteriro-Riviere NA, Aggarwal R, Davis JP, Narayan RJ, Self WT, et al. Nanoceria as antioxidant: Synthesis and biomedical applications. JOM. 2008;60:33–7. doi: 10.1007/s11837-008-0029-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh S, Dosani T, Karakoti AS, Kumar A, Seal S, Self WT. A phosphate-dependent shift in redox state of cerium oxide nanoparticles and its effects on catalytic properties. Biomaterials. 2011;32:6745–53. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.05.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Das M, Patil S, Bhargava N, Kang JF, Riedel LM, Seal S, et al. Auto-catalytic ceria nanoparticles offer neuroprotection to adult rat spinal cord neurons. Biomaterials. 2007;28:1918–25. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alili L, Sack M, Karakoti AS, Teuber S, Puschmann K, Hirst SM, et al. Combined cytotoxic and anti-invasive properties of redox-active nanoparticles in tumor-stroma interactions. Biomaterials. 2011;32:2918–29. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen J, Patil S, Seal S, McGinnis JF. Rare earth nanoparticles prevent retinal degeneration induced by intracellular peroxides. Nat Nanotechnol. 2006;1:142–50. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2006.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou X, Wong LL, Karakoti AS, Seal S, McGinnis JF. Nanoceria inhibit the development and promote the regression of pathologic retinal neovascularization in the Vldlr knockout mouse. PLoS One. 2011;6:el6733. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kong L, Cai X, Zhou X, Wong LL, Karakoti AS, Seal S, et al. Nanoceria extend photoreceptor cell lifespan in tubby mice by modulation of apoptosis/survival signaling pathways. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;42:514–23. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edelhauser HF, Rowe-Rendleman CL, Robinson MR, Dawson DG, Chader GJ, Grossniklaus HE, et al. Ophthalmic drug delivery systems for the treatment of retinal diseases: basic research to clinical applications. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:5403–20. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai X, Sezate SA, McGinnis JF. Neovascularization: ocular diseases, animal models and therapies. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;723:245–52. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-0631-0_32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cai X, Nash Z, Conley SM, Fliesler SJ, Cooper MJ, Naash MI. A partial structural and functional rescue of a retinitis pigmentosa model with compacted DNA nanoparticles. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dorrell MI, Aguilar E, Jacobson R, Yanes O, Gariano R, Heckenlively J, et al. Antioxidant or neurotrophic factor treatment preserves function in a mouse model of neovascularization-associated oxidative stress. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:611–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI35977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farjo R, Skaggs JS, Nagel BA, Quiambao AB, Nash ZA, Fliesler SJ, et al. Retention of function without normal disc morphogenesis occurs in cone but not rod photoreceptors. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:59–68. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200509036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kong L, Tanito M, Huang Z, Li F, Zhou X, Zaharia A, et al. Delay of photoreceptor degeneration in tubby mouse by sulforaphane. J Neurochem. 2007;101:1041–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen JI, Roychowdhury S, DiBello PM, Jacobsen DW, Nagy LE. Exogenous thioredoxin prevents ethanol-induced oxidative damage and apoptosis in mouse liver. Hepatology. 2009;49:1709–17. doi: 10.1002/hep.22837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao X, Talalay P. Induction of phase 2 genes by sulforaphane protects retinal pigment epithelial cells against photooxidative damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10446–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403886101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kong L, Zhou X, Li F, Yodoi J, McGinnis J, Cao W. Neuroprotective effect of overexpression of thioredoxin on photoreceptor degeneration in Tubby mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;38:446–55. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mandal MN, Patlolla JM, Zheng L, Agbaga MP, Tran JT, Wicker L, et al. Curcumin protects retinal cells from light-and oxidant stress-induced cell death. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:672–9. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanito M, Masutani H, Kim YC, Nishikawa M, Ohira A, Yodoi J. Sulforaphane induces thioredoxin through the antioxidant-responsive element and attenuates retinal light damage in mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:979–87. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor RC, Acquaah-Mensah G, Singhal M, Malhotra D, Biswal S. Network inference algorithms elucidate Nrf2 regulation of mouse lung oxidative stress. PLoS Comput Biol. 2008;4:el000166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boesze-Battaglia K, Goldberg AF. Photoreceptor renewal: a role for peripherin/rds. Int Rev Cytol. 2002;217:183–225. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(02)17015-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Connell G, Bascom R, Molday L, Reid D, Mclnnes RR, Molday RS. Photoreceptor peripherin is the normal product of the gene responsible for retinal degeneration in the rds mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:723–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.3.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Molday RS, Hicks D, Molday L. Peripherin. A rim-specific membrane protein of rod outer segment discs. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1987;28:50–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bennett J. Commentary: an aye for eye gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther. 2006;17:177–9. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahuja-Jensen P, Johnsen-Soriano S, Ahuja S, Bosch-Morell F, Sancho-Tello M, Romero FJ, et al. Low glutathione peroxidase in rd1 mouse retina increases oxidative stress and proteases. Neuroreport. 2007;18:797–801. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3280c1e344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sandbach JM, Coscun PE, Grossniklaus HE, Kokoszka JE, Newman NJ, Wallace DC. Ocular pathology in mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (Sod2)-deficient mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:2173–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qi X, Lewin AS, Sun L, Hauswirth WW, Guy J. SOD2 gene transfer protects against optic neuropathy induced by deficiency of complex I. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:182–91. doi: 10.1002/ana.20175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh S, Kumar A, Karakoti A, Seal S, Self WT. Unveiling the mechanism of uptake and sub-cellular distribution of cerium oxide nanoparticles. Mol Biosyst. 2010;6:1813–20. doi: 10.1039/c0mb00014k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tarnuzzer RW, Colon J, Patil S, Seal S. Vacancy engineered ceria nanostructures for protection from radiation-induced cellular damage. Nano Lett. 2005;5:2573–7. doi: 10.1021/nl052024f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heckert EG, Karakoti AS, Seal S, Self WT. The role of cerium redox state in the SOD mimetic activity of nanoceria. Biomaterials. 2008;29:2705–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Korsvik C, Patil S, Seal S, Self WT. Superoxide dismutase mimetic properties exhibited by vacancy engineered ceria nanoparticles. Chem Commun. 2007:1056–8. doi: 10.1039/b615134e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pirmohamed T, Dowding JM, Singh S, Wasserman B, Heckert E, Karakoti AS, et al. Nanoceria exhibit redox state-dependent catalase mimetic activity. Chem Commun. 2010;46:2736–8. doi: 10.1039/b922024k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adamian M, Pawlyk BS, Hong DH, Berson EL. Rod and cone opsin mislocalization in an autopsy eye from a carrier of X-linked retinitis pigmentosa with a Gly436Asp mutation in the RPGR gene. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:515–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Concepcion F, Chen J. Q344ter mutation causes mislocalization of rhodopsin molecules that are catalytically active: a mouse model of Q344ter-induced retinal degeneration. PLoS One. 2010;5:el0904. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gao J, Cheon K, Nusinowitz S, Liu Q, Bei D, Atkins K, et al. Progressive photoreceptor degeneration, outer segment dysplasia, and rhodopsin mislocalization in mice with targeted disruption of the retinitis pigmentosa-1 (Rpl) gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:5698–703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042122399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lopes VS, Jimeno D, Khanobdee K, Song X, Chen B, Nusinowitz S, et al. Dysfunction of heterotrimeric kinesin-2 in rod photoreceptor cells and the role of opsin mislocalization in rapid cell death. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:4076–88. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-08-0715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hagstrom SA, Adamian M, Scimeca M, Pawlyk BS, Yue G, Li T. A role for the Tubby-like protein 1 in rhodopsin transport. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:1955–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ito Y, Shimazawa M, Inokuchi Y, Yamanaka H, Tsuruma K, Imamura K, et al. Involvement of endoplasmic reticulum stress on neuronal cell death in the lateral geniculate nucleus in the monkey glaucoma model. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;33:843–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shimazawa M, Inokuchi Y, Ito Y, Murata H, Aihara M, Miura M, et al. Involvement of ER stress in retinal cell death. Mol Vis. 2007;13:578–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salminen A, Kauppinen A, Hyttinen JM, Toropainen E, Kaarniranta K. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in agerelated macular degeneration: trigger for neovascularization. Mol Med. 2010;16:535–42. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2010.00070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lin JH, Li H, Yasumura D, Cohen HR, Zhang C, Panning B, et al. IRE1 signaling affects cell fate during the unfolded protein response. Science. 2007;318:944–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1146361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tzekov R, Stein L, Kaushal S. Protein misfolding and retinal degeneration. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a007492. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sato K, Nakazawa M, Takeuchi K, Mizukoshi S, Ishiguro S. S-opsin protein is incompletely modified during N-glycan processing in Rpe65(-/-) mice. Exp Eye Res. 2010;91:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rong Y, Distelhorst CW. Bcl-2 protein family members: versatile regulators of calcium signaling in cell survival and apoptosis. Ann Rev Physiol. 2008;70:73–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.021507.105852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dong Y, Zhang M, Liang B, Xie Z, Zhao Z, Asfa S, et al. Reduction of AMP-activated protein kinase alpha2 increases endoplasmic reticulum stress and atherosclerosis in vivo. Circulation. 2010;121:792–803. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.900928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang J, Pawlyk B, Wen XH, Adamian M, Soloviev M, Michaud N, et al. Mpp4 is required for proper localization of plasma membrane calcium ATPases and maintenance of calcium homeostasis at the rod photoreceptor synaptic terminals. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:1017–29. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bourges JL, Bloquel C, Thomas A, Froussart F, Bochot A, Azan F, et al. Intraocular implants for extended drug delivery: therapeutic applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006;58:1182–202. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cheng L, Hostetler K, Valiaeva N, Tammewar A, Freeman WR, Beadle J, et al. Intravitreal crystalline drug delivery for intraocular proliferation diseases. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:474–81. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hirst SM, Karakoti AS, Tyler RD, Sriranganathan N, Seal S, Reilly CM. Anti-inflammatory properties of cerium oxide nanoparticles. Small. 2009;5:2848–56. doi: 10.1002/smll.200901048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. There are no detectable changes in retinal function (A) or structure (B) caused by saline injection in wt/wt mice. Mice were intravitreally injected at P7 with 1 μ1 of saline, visual function was assessed by full field ERG and morphology was evaluated by histology of H & E stained sections at PI-30. N=5 ∼ 7 mice from each group. RPE: retinal pigment epithelium, OS: outer segment, IS: inner segment, ONL: outer nuclear layer, GCL: ganglion cell layer. Scale bar, 200 μm