Abstract

Since late 2010, the Arab world has entered a tumultuous period of change, with populations demanding more inclusive and accountable government. The region is characterised by weak political institutions, which exclude large proportions of their populations from political representation and government services. Building on work in political science and economics, we assess the extent to which the quality of governance, or the extent of electoral democracy, relates to adult, infant, and maternal mortality, and to the perceived accessibility and improvement of health services. We compiled a dataset from the World Bank, WHO, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Arab Barometer Survey, and other sources to measure changes in demographics, health status, and governance in the Arab World from 1980 to 2010. We suggest an association between more effective government and average reductions in mortality in this period; however, there does not seem to be any relation between the extent of democracy and mortality reductions. The movements for changing governance in the region threaten access to services in the short term, forcing migration and increasing the vulnerability of some populations. In view of the patterns observed in the available data, and the published literature, we suggest that efforts to improve government effectiveness and to reduce corruption are more plausibly linked to population health improvements than are efforts to democratise. However, these patterns are based on restricted mortality data, leaving out subjective health metrics, quality of life, and disease-specific data. To better guide efforts to transform political and economic institutions, more data are needed for healthcare access, health-care quality, health status, and access to services of marginalised groups.

Background

Uprisings and protests in the Arab world have emphasised social and economic inequity, absence of political accountability, and concerns about government corruption. Although the optimism for more inclusive and effective governance throughout the region has now given way to concerns about the rise of patriarchal conservatism, civil war, and political instability in some countries, the demand for more inclusive and equitable government in the region has been heard. The toppling of regimes in Egypt and Tunisia by popular protest in 2011, and the removal of a dictatorship in Libya by an alliance of activists, domestic fighters, and international forces, created hope for the creation of governments that respond to the needs of their population throughout. However, this hope is coupled with a concern that antidemocratic impulses can occur in post-revolt or interim periods, as seen in Egypt. The optimism for reform is also coupled with brutal realities about the use of force against civilians, and even health-care personnel, by regimes attempting to remain in power. In Syria and Bahrain, the governments have responded to demands for political change with a brutal use of force. And, in Syria, conflict has escalated with the government’s increasing use of force and the involvement of foreign fighters, leading to a catastrophe for the population. In Saudi Arabia and Jordan, governments have tried to quell domestic pressures with social reforms. The uprisings have increased awareness of the need for political freedom and social justice throughout the Arab world—an awareness that can potentially be harnessed for reform. This Series on health in the Arab world addresses the shared challenges in improving health, from taking on non-communicable diseases and tobacco control, to mitigating the health effects of war and environmental change, and finally building health systems allowing for universal access.1–5

The 22 countries in the Arab world are diverse, ranging from oil-rich states of the Persian Gulf with long-life expectancy and low maternal mortality, to poor states with poor governance and poor health indicators, such as Yemen and Somalia (table; panel 1; figure 1). Although the regimes governing these countries are shaped by an often shared colonial legacy, and Cold War politics, the region is highly diverse.6 In this Series, we consider the 22 Arabic-speaking nations, concentrated in the Middle East and north Africa. The Arab world, as a whole, is near the global averages in terms of poverty and inequality (World Bank data; panel 1). And, although social inequality is often pointed to as an impetus for the Arab uprisings, as Cammett and Diwan7 note, neither economic growth rates nor absolute levels of income inequality can explain popular movements that have emerged to overthrow dictators. Instead, the perceptions of socioeconomic trends, driven by declining welfare regimes and the rollback of the state, could be more explanatory.7 The Arab world has life expectancy and infant mortality indicators that are at or better than the global averages (figure 2). Life expectancy and under-5 mortality have improved more in the Arab world in the past 30 years than in any other region (figure 2). These sharp improvements in human development could have, as has been argued, shaped the path to revolution, as an increasingly educated youth with high expectations began to place pressure on their governments, and weaken their bond with the state.8

Panel 1: Data sources.

We constructed a dataset including data for demographics, epidemiology, and governance in the 22 countries in the Arab world from 1980 to 2012. A sample of some core data are in table 1, and the full dataset is available from the authors on request. A description of key sources is below.

Arab Barometer Survey

A 2010–11 representative survey across ten Arab countries, including Jordan, occupied Palestinian territory, Lebanon, Egypt, Sudan, Algeria, Morocco, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Mauritania, Syria, and Iraq. The survey seeks to measure citizen attitudes, values, and behaviour patterns relating to pluralism, freedoms, tolerance, and equal opportunity; social and interpersonal trust; social, religious, and political identities; conceptions of governance and an understanding of democracy; and civic engagement and political participation.

World Development Indicators 2012 (World Bank)

These indicators, collected from 1980 to 2011, provide internationally comparable statistics about development and the quality of people’s lives. We used data for population sizes, economic growth, gross domestic product, oil rents, and others to contextualise health developments within their unique socioeconomic political environments.

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) mortality statistics

From the IHME Global Health Data Exchange, adult mortality rates (1970–2010), maternal mortality rates (1980–2008), and infant and child mortality rates (1970–2010) were collected to measure health outcomes and progress towards Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5. IHME combines registry data, surveys, and censuses to produce mortality estimates.

Worldwide Governance Indicators

These indicators, assembled by the World Bank and the Brookings Institution from 1996 to 2011, summarise the views on the quality of governance collected from survey institutes, think tanks, non-governmental organisations, international organisations, and the private sector.

Polity IV Dataset

The Polity2 score is a measurement of a political regime, widely used in political science. Negative scores show an autocratic regime, positive scores show a democratic government. The Polity IV project is a project from the University of Maryland, MD, USA, and Colorado State University, CO, USA, characterising regimes from 1800 to 2011.

Appendix p 2 shows the key variables provided by each data source.

Figure 1. Map of the Arab world.

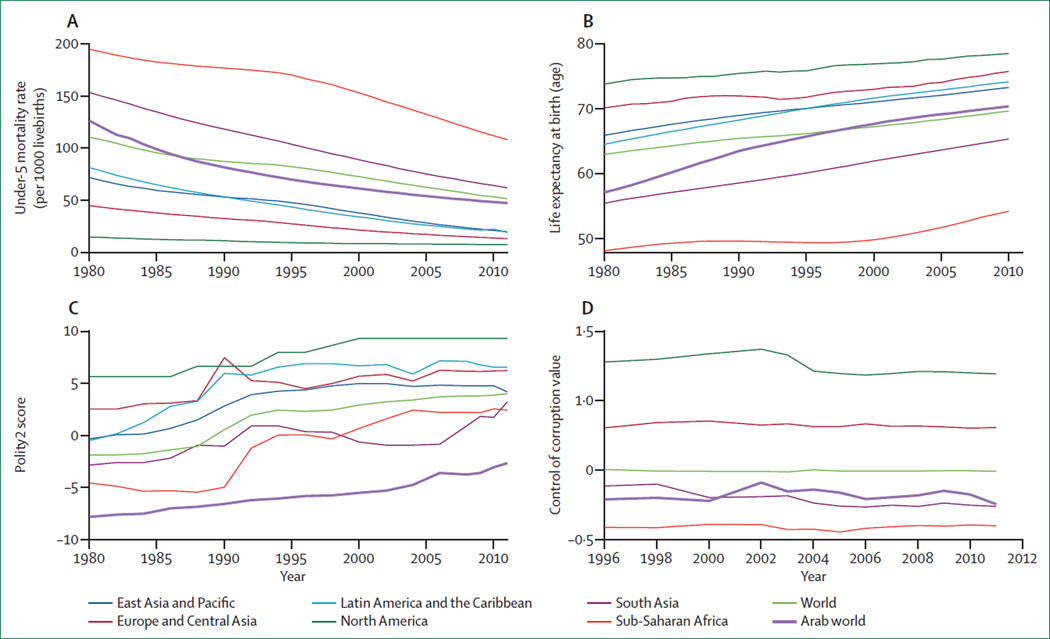

Figure 2. The Arab world in global context.

(A) After improvement in the 1980s, under-5 mortality is now slightly better than the global average. (B) Life expectancy at birth is slightly greater than the global average. (C) The Arab world is the most autocratic region in the world, according to electoral democracy scores from the Polity IV dataset, where a polity2 score of 10 is democracy and a score of −10 is autocracy. (D) Corruption in the Arab world is high according to World Governance Indicator data, where 0 is the global average; the Arab world fares consistently only better than sub-Saharan Africa since 1996. Data from Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation mortality estimates, World Bank Databank, Polity IV dataset, and the World Bank/Brookings World Governance Indicators (panel 1).

What distinguishes the Arab world—almost as much as the Arabic language itself—is the absence of political accountability throughout the region. The core concept of accountability is that stakeholders being held accountable (those who have power) have obligations to act in ways that are consistent with accepted standards of behaviour and that they will be sanctioned for failures to do so.9 In democratic states, elections are a frequent operative instrument of accountability, but they neither always serve that role nor do they hold a monopoly on accountability. Across the Arab world, political systems are often dominated by elites and do not have ways to address the population’s broader concerns, showing the neglect of operative methods for accountability. Additionally, as discussed in other papers in this Series,2,5 many states in the Arab world have abandoned or disregarded contracts of trust with their citizens, through neglect of public services and segments of the population, or the use of violence against their own populations. Another distinguishing feature is the extent of external intervention in the form of colonialism, economic sanctions, foreign aid, military assistance, and military conflict that have contributed to, but do not fully explain, the failure to establish accountable and inclusive political systems in the Arab world. These political factors might explain variations in access to health services and health outcomes, complementing epidemiological or social factors typically considered by public health researchers. In this paper, we discuss the effect of governance type and quality on health; however, we do not address all the political factors that might affect health outcomes, such as foreign economic and military intervention, state violence, ethnic or religious fragmentation and diversity, civil war, patronage networks, or the political power of the medical profession.

Government political accountability drives the adequate and fair distribution of national public goods.10,11 The equitable distribution of public goods, such as health care, education, roads, and infrastructure, is so intertwined with accountability that some political scientists use measures of the distribution of these public goods as a measure of government political accountability.12,13 In republics, pension plan coverage is double that in monarchies (44% vs 22%, respectively), which suggests that regimes dependent on their social achievements for stability are more likely to provide for their population.14,15 Another factor in determining provision of public goods could be social division, or what political scientists have referred to as fractionalisation, which can occur on social, ethnic, or religious grounds.16 Countries that have greater social divisions have less access to health care, higher child and maternal mortality rates, and less investment in public goods.17,18 In regions with high ethnic fragmentation, the health benefits of democracy are not realised, perhaps because of policies that deprive minority groups.17

The role of governance in shaping health

To establish a causal pathway for governance and health, scholars have been divided about whether it is democracy or governance effectiveness that leads to improvements in health and human development. Although definitions of democracy vary and are subject to extensive debate, most studies relating democracy and health consider electoral democracy, as scored by the Polity IV project (panel 1), which is based on the competitiveness, openness, and level of participation in elections. These measures of electoral democracy do not judge the extent to which governments actually respond to population demands, but more narrowly capture the extent to which they hold good elections. Scholars arguing for a causal part played by democracy in improving welfare suggest that democracy leads to increased social spending, and accountability leading to redistribution of resources to people with a low income, which in turn leads to improved welfare.19,20 However, critics point out that outside of countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, public spending and human development are not correlated,21 and that democracy has little or no effect on maternal and child mortality rates.22 Furthermore, countries transitioning to democracy can take a step back in human development because young democracies are increasingly prone to instability and conflict,23 and are likely to have weak political institutions that are unable to deliver services effectively.24 An alternative thesis linking democracy to human development is that a country’s so-called stock of democracy— its experience over decades—leads to the creation of a strong civil society, the empowerment of oppressed groups, and higher quality political institutions, leading to pronounced improvements in human development in the long term.25,26

Other researchers have suggested that it is not electoral democracy that leads to improvements in health and human development, but rather high quality bureaucratic governments, which exercise power impartially and are able to deliver public services.27 The most widely used measurements for government effectiveness are from the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI; panel 1). These cross-country measures assess several components of governance on the basis of international expert surveys collected since 1996. These measures, produced through collaboration between the World Bank and Brookings Institution, combine 30 data sources, bringing together metrics for governance quality from research institutes, international organisations, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and the private sector, and include citizen and expert survey data. In the WGIs, government effectiveness is measured on the basis of perceptions of the quality of public services, the civil service (including freedom from political pressures), the quality of policy formulation, and the government’s commitment to these policies. Researchers using these governance indicators have identified some factors that are likely to lead to ineffective government—eg, a high dependence on oil and gas rents worsens corruption, bureaucratic quality, and legal impartiality, which are problems that might be expected in Arab countries deriving a high portion of gross domestic product from oil rents.28 However, in the Arab world, no clear relation exists between oil rents and government effectiveness as measured on the basis of WGI indicators. Additionally, WGI indicators have been critiqued for their reliance on perception-based measures of governance taken from surveys, often by international organisations.29 Critics have also pointed out that organisations offering assessments are mainly from high-income countries, and might score countries with strong trade and security relations high. Others have suggested that the indicators create a situation in which governments promise best practice reforms without any plan for implementation to signal to the inter national community that they are improving governance.30 Despite these limitations, the WGI indicators for corruption and government effectiveness correlate reason ably with measures for corruption and government ability to address problems from the Arab Barometer Survey (panel 1) of citizens (correlation coefficients of 0·56 and 0·41, respectively), offering some support for their use. In parallel with the notion of the stock of democracy, we also consider a country’s average government effective ness from 1998 to 2010 (figure 3), based on the notion that a country’s long-term experience with effective government could shape mortality.

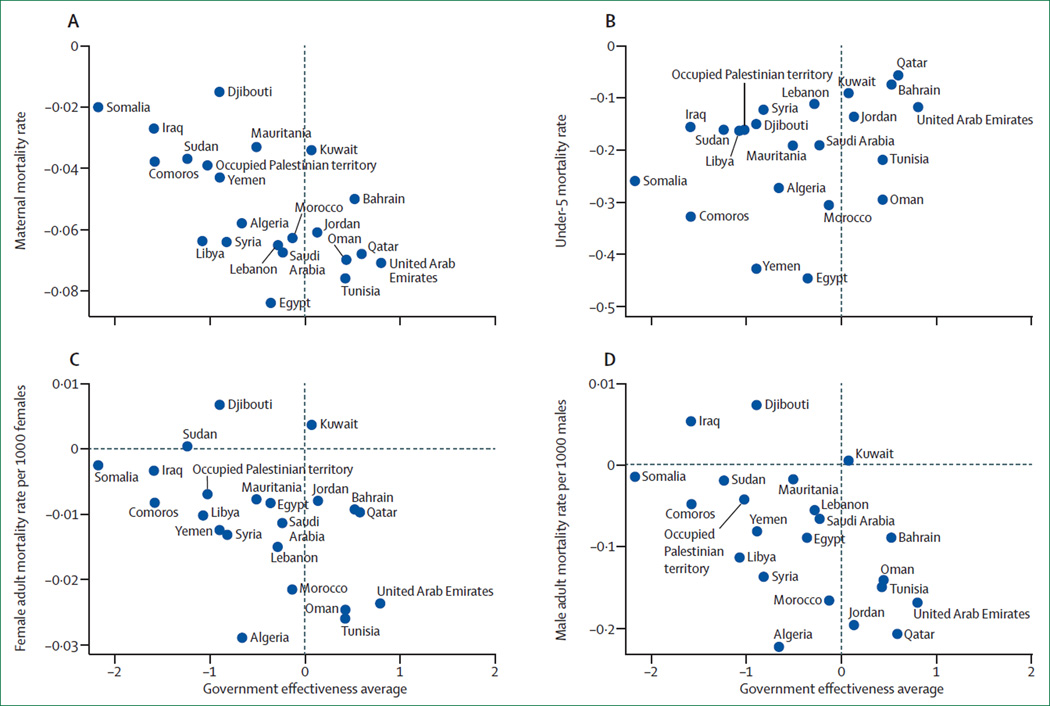

Figure 3. Government effectiveness (mean) versus mortality (mean annual change), 1980–2010.

Increases in government effectiveness (standard normal unit) seem to correlate with greater reductions in maternal and adult mortality. Data from World Bank, Polity IV project, and Institute of Health Metrics Evaluation (panel 1).

So far, public health researchers have given little attention to how regimes govern and the effectiveness of their governance. Although our focus here is on the Arab world, a region undergoing upheaval, these analyses might offer insights into the relation between governance and health globally. The primary dilemma is the inequity created by political exclusion, in which a two-tiered health system with a high-technology private sector caters to elites, whereas a second-rate system serves the wider public, and in which political loyalties shape access to health care, sometimes excluding women and ethnic and political minorities.

There are many reasons for the shortage of inclusive and accountable political institutions in the Arab world, including the legacy of colonialism, informal local social institutions, and external rents freeing governments of the need to tax and respond to their citizens, including oil profits and foreign assistance. The remains of colonial institutions persist across the Arab world today. As Tell6 points out in an Essay in this Series, these colonial legacies might play an important part in explaining underdevelopment in the Arab world. Acemoglu and colleagues31 described how regions where colonial states set up extractive political institutions remain poorer today, even when accounting for geography. Extractive political institutions were usually created to reap the material benefits of colonialism—including oil and access to trade routes—without having to settle in a place where colonial settler mortality was high. Although direct colonialism has largely ended, with the possible exception of the occupied Palestinian territory, extractive colonial institutions have often been replaced by extractive local institutions.31

A complementary explanation for the poor popular political participation in the region is that the formal governmental institutions of nowadays were built on a foundation of informal institutions, based on kinship, tribes, and religious organisations. The interaction of colonial, neocolonial, and local institutions has been shown to shape state formation and economic development in other regions.32 Some scholars suggest that these informal political institutions are stronger and more pervasive than are formal governmental institutions in the Arab world, and continue to help with commerce, social services, and local collective action.33 Nowadays, throughout much of the Arab world, Islamic and other organisations have established systems of social services and representation that allow for political participation outside of state institutions.34,35 Yet, these same institutions might also explain the absence of political inclusiveness in formal state institutions. Governments across the region have incorporated these informal networks, and their rules for resource allocation, into their parliaments, transforming government institutions into “agents of patronage and kinship and detracting them from their public service role”.34

A third explanation for the absence of political inclusiveness in the Arab world is the persistence of external forces keeping autocratic regimes in power. Support to such regimes, such as those in Bahrain and Saudi Arabia, includes oil revenues and military alliances in exchange for their support of US and European military and security efforts in the region. The history of external forces in the region, war, conflict, and the long-term effects of oil dependence and resulting deterioration of environments and lifestyle are discussed in greater detail in other papers in this Series.2,5

The aggregate metrics measuring electoral democracy and governance quality do not fully capture the exclusion of women and minorities from the political process. Women and minorities are most prominently excluded from the political process in the Arab world, with potential consequences for access to health care. Compared with women across the world, Arab women have markedly less rights to political participation, and have only 5·7% of parliamentary seats in the region (compared with 15% in sub-Saharan Africa and 12·9% in Latin America).36,37 Six of the 16 countries scoring lowest for their discriminatory laws and societies regarding women are in the Arab world, according to the World Economic Forum’s Gender Gap Index.38 Arab women have experienced deterioration of their political rights after the deployment of US military troops to a country—eg, Iraq.39 This deterioration could be because troop presence weakens political regimes making them less likely to stand up to Islamists and traditionalists’ opposition to women’s rights.39 Women in the Arab world are less likely to be educated, less likely to be physically active, more likely to be victims of intimate partner violence, and more likely to be obese than are men. Additionally, Arab women have the world’s lowest rates of labour force participation, among the world’s highest rates of female illiteracy, face discriminatory laws, and are hampered by sexist mentalities.36 Despite these setbacks, overall and maternal mortality rates of women aged 15–45 years have improved throughout the region since 1980. Similar to women, minority groups and migrant workers also face discrimination and political exclusion.

Across the Arab world, communities are excluded from social services on the basis of their country or region of origin and religion. Immigrant labourers—mainly from south and southeast Asia—in the countries of the Persian Gulf, refugees from the occupied Palestinian territory in many Arab countries, stateless Bedouins, and ethnic and religious groups (eg, Kurds living in border areas) are all discriminated against in the provision of social services. These non-citizen groups form most of the population in some Arab countries—eg, in Qatar, three of four residents are non-citizens. In the Arab states of the Persian Gulf, where most of the population in some states are migrant workers, less than 30% of the population are covered in pension plans and social insurance schemes.14 Non-citizen groups have little room to protest their discrimination because they are outside the protection of national legal systems and often overtly persecuted, as they have been in cases of protracted conflict including in Iraq and Sudan.40 Discrimination against these minorities is in violation of the 1992 Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities. In many cases, exclusion has been eased by emergency laws (which have been in place since 1963 in Syria), allowing governments to override remaining checks on discrimination.

Trends in health and governance

Overall, since 1970, health indicators in the Arab world have sharply improved with an average increase in life expectancy of 19 years—the largest gain among world regions, and an average reduction in infant mortality of 60 deaths per 1000 live births.15 In fact, five of the ten countries with the largest development gains since 1970 were Arab (Oman, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco).15,41 Since 1980, adult mortality has been declining across the region, except in Iraq (appendix p 3). These improvements have sometimes been attributed to government investment in social protection, and high levels of public sector employment, especially in countries of the Persian Gulf. However, mortality statistics capture only one aspect of health and wellbeing, and say little about quality of life, distress, and human security.

In the Arab world, the past two decades have been characterised by steady or worsening corruption and reductions in political voice and accountability (appendix p 5). These deteriorating, or stagnantly poor, political conditions might explain the origins of some revolutions. Even though oil-rich countries of the Persian Gulf did well in assessments of the efficacy of their public administration, they did worst on public accountability (appendix p 5).15 Inequality can be a direct result of corruption, because resources and the benefits of economic growth are distributed to people who are supportive of the regime, sometimes at great expense to the public.42,43 Additionally, poor governance has restricted economic growth in the Arab world.44 Poor governance can undermine investment, restrict job creation, and, most importantly, erode public trust and social fabric.

In settings of poor governance, civil society and community networks are sometimes able to provide essential services, mitigating the effect of poor governance on health. Across the Arab world, formal and informal organisations and community-based groups have provided many additional forms of social protection (panel 2). Islamic political movements have captured the most scholarly, media, and policy attention. Organisations such as Hezbollah, Hamas, and the Muslim Brotherhood have sought to gain legitimacy through their efforts to provide or broker access to social welfare. But many other private stakeholders supply medical services, including both for-profit and not-for-profit providers and local and international organisations. However, in several authoritarian governments in the Arab world, activity of the informal sector and civil engagement is low, which has been attributed to the extent of government surveillance.55

Panel 2: Islamists and non-state providers in the Arab world.

Outside of the high-income oil monarchies of the Persian Gulf, states have not been able to maintain functioning public health systems for their citizens. This has opened the door for the consolidation or increase in an array of non-state providers of basic health services. Private, for-profit providers constitute the largest component of the non-state sector, exacerbating health inequalities because the poor and low-to-middle classes often cannot afford treatment at their institutions. Both local and international non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are also active in the health sector, often but not exclusively operating at a very local level. Religious charitable organisations have the longest histories as providers of health services, dating back to at least the colonial period, and in some countries in the region remain important. Of all non-state providers, Islamists (both Sunni and Shia) have captured the most scholarly, policy, and media attention and are distinct from religious charities because they have explicit political aspirations alongside their religious and social goals. Islamists refer to organisations and movements that aim to build political power, often but not exclusively through participation in elections and other formal state institutions, and generally use non-violent means.45 In practice, however, the lines between Islamists and religious charities are often blurred as religious and social activism can be interpreted as political in their own right and because Islamists can have close informal relationships with religious charitable organisations or overlapping leaderships.46 Furthermore, it is worth noting that the designation as non-state is ambiguous because many Islamist organisations with associated charitable wings have contested elections and won posts in local and national government, a trend that has only increased since the Arab uprisings.

A snapshot of the range of the health institutions and programme activities of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, its counterpart in Jordan, Hamas in occupied Palestinian territory, and Hezbollah in Lebanon shows the varied roles and weight of Islamists in distinct health system contexts. In Jordan, about 50 Islamic NGOs, which are mainly linked to the Muslim Brotherhood, were licensed. Some of these institutions have had many branches running schools, clinics, and hospitals.47–49 Despite the growth of these Islamic NGOs, the state is the major provider of health services in the country, whereas private, for-profit providers are increasingly important, particularly for high-income groups.50 In Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood runs a network of clinics, schools, and vocational training centres that are often credited with winning support in the population. In practice, the network’s reach is restricted in a country with a population of 80 million people. Although it is difficult to obtain precise values on the organisation’s health institutions, according to a 2006 report, the Brotherhood ran about 22 hospitals and controls about 20% of all NGOs registered in Egypt,51 although some commentators suggest that the organisation’s importance in welfare provision is exaggerated.52 The state is the major provider for most citizens, although the declining quality of care in the public health system and the rise of for-profit providers since at least the 1980s has diminished its actual importance in health-care provision and financing. The role of Hamas in the health sector of the occupied Palestinian territoy is even more difficult to quantify or even to classify, partly because the organisation actively tries not to publicise which health institutions it controls to avoid crackdowns by both Fatah (the political party that maintains control over the Palestinian National Authority in the occupied Palestinian territory) and Israel on its facilities. Furthermore, many perceived Hamas-run clinics and dispensaries might be run by supporters of the group, but have no formal affiliation with the organisation.53 A 2003 report by the International Crisis Group estimated that about 70–100 social welfare associations were affiliated with Hamas, excluding branch organisations.45 Hamas has always been more entrenched in the Gaza Strip, a trend that has increased since the Fatah–Hamas split in 2007. Even in Gaza, however, the UN Relief and Works Agency plays the most important part in health-care provision for the local population (Cammett M, unpublished). Of all of the Islamist organisations, Hezbollah has the most extensive network of health-care institutions relative to its national context. In Lebanon, the state has played a minimal part in providing and regulating health care, opening up the field to a diverse array of providers. Of about 400 clinics and dispensaries that tend to serve low-income Lebanese, Hezbollah runs about 25 facilities, a value that probably underestimates its involvement in health-care provision because it does not include additional health networks linked to Hezbollah agencies. Additionally, Hezbollah runs four hospitals located in predominantly Shia Muslim communities.54

In view of the decline in public health capacity and state commitment to health sectors across much of the Arab world, non-state provision has an important role in meeting population health needs. At the same time, it has potential drawbacks for access to care, accountability, and even national integration. First, non-state stakeholders, including the largest Islamist providers, do not have and might not even aspire to national reach. Their health services therefore have in-built geographic disparities, no matter what their intentions might be. Second, providers with an explicitly political agenda, such as Islamists who participate in formal politics, might make the delivery of some services, especially those with higher fixed costs, contingent on political support. Although Hezbollah does not deny care to those who come to their health facilities, it reserves the most extensive and continuous services for hardcore loyalists, especially the families of martyrs and fighters. This political quid pro quo is hardly unique to Islamists; non-Islamist parties in Lebanon employ political criteria in allocating services, whereas in Tunisia under Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, the ruling Constitutional Democratic Rally, the ruling party of the deposed president, distributed social assistance on a discretionary basis.54 By definition, patronage and clientelism in the health sector restrict the accountability of providers to beneficiaries. Finally, in the post-colonial era, the extension of health, education, and other social rights to populations was integral to state and nation-building processes in many Arab countries. To the extent that states can no longer provide or cannot properly regulate the provision of health-care services by non-state organisations, trust in political institutions and a shared sense of membership in a national political community might diminish.

Although deteriorating health infrastructure and conditions cannot be causally linked to the impetus for the Arab uprisings, it is clear that health concerns feature prominently in the concerns of people dissatisfied with governance performance. A poll by Zogby56 asked citizens of Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates to rank ten factors in order of importance, including expanding employment opportunities, ending corruption and nepotism, protecting personal and civil rights, and resolving the Israel–Palestine conflict. In 2004, improving the health-care system ranked first across the region, whereas it ranked second to expanding employment opportunities in 2005.56

Measurement of the relation between health and governance

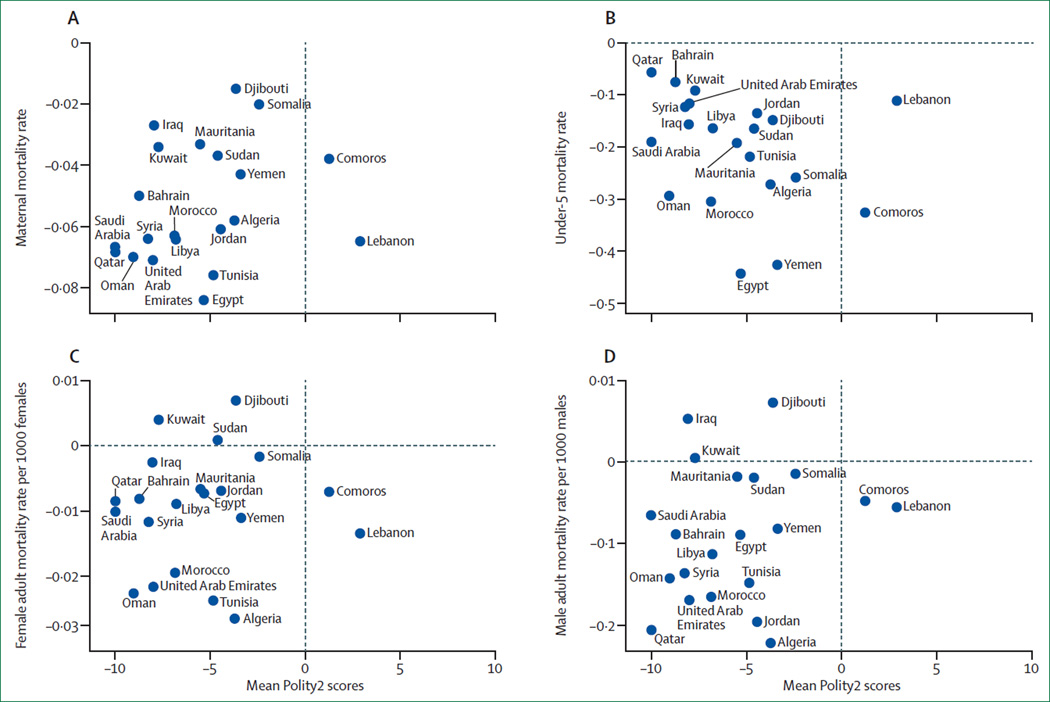

Data for demographic, mortality, and governance trends in the Arab world have rarely crossed out of disciplinary silos in public health, economics, or politics (panel 1). For this paper, we built an extensive dataset for indicators related to health and governance in the Arab world (data available from authors on request). Our primary aim was to synthesise the literature on health and governance in the Arab world, investigate the associations between governance on mortality trends, and explore the possible mechanisms of any such effect. We established a model for testing the relation between electoral democracy (measured by Polity score) or good governance (measured by WGI) and mortality from 1980 to 2011 (appendix p 6). Although some results were statistically significant in our conservative model, these relations were inconsistent (appendix p 7). Notably, with several less conservative approaches, each of the relations had significant effects on mortality; however, we omit these relations in favour of the most conservative model. In view of the concern that the long-term effect of democracy or good governance (rather than year-on-year changes) leads to improvements in health outcomes,25 we also plotted these effects against mortality indicators (figure 3, figure 4). We noted that high government effectiveness seems to be associated with high average improvements in mortality indicators. Democracy seems to have no consistent relation with mortality improvements. This finding is consistent with recent scholarship suggesting that good governance strengthens the capacity of the state to deliver services.57 Although these trends do not establish a causal relation, they favour the argument that government effectiveness, not democracy, is associated with improvements in mortality. Because these findings are based on mortality statistics, these trends provide no information about the effect of autocracy and corruption on quality of life, including restrictions on freedom.

Figure 4. Democracy score (mean) versus mortality (mean annual change), 1980–2010.

On the x-axis, 10 is democracy and −10 is autocracy. Democracy does not seem to have any consistent relation to changes in mortality. Data from World Bank, Polity IV project, and Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (panel 1).

To probe how citizen perceptions of good governance might be associated with health, we used data from the 2010–11 Arab Barometer Survey (panel 1). Across the Arab world, most Arabs see their governments as corrupt, and citizens of those countries with worse corruption tended to have least confidence that governments were improving health services (appendix p 8). However, these perceptions of corruption and the perception that political leaders are not concerned with ordinary citizens do not seem to have a clear relation to changes in mortality.

Informing the reform agenda

Academic research is divided on whether it is democracy or effective government that leads to improved health. We cannot be any more conclusive about the causal mechanisms between governance and health in the Arab world. Our analysis shows that in the Arab world, democracy and mortality improvements are not associated; however, there does seem to be an association—worthy of further investigation—between government effectiveness and mortality improvements.

In view of the concerns about the quality of the cross-country data for governance and electoral democracy, new regional data that show action and implementation, rather than perceptions of good governance, are needed. Additionally, data specific for marginalised groups are needed to consider the effect of political exclusion on welfare, which is an effect lost in aggregated population statistics. Finally, the pathways and mechanisms by which good governance leads to improved welfare remain contested in political science. The assessments possible with the existing data do not address questions of causality. Local qualitative studies assessing mechanisms of how political accountability might translate into improved mortality are greatly needed. Although the effects are likely to spread beyond the health sector, measures of health-care quality in the region would be valuable in this assessment.

Aggregate statistics for population health tell us little about the health status of the least advantaged residents of the Arab world. WHO relies on government reported information, the Arab Barometer Survey includes only citizens, and World Bank data for inequalities in the Arab world are sparse (panel 1), making an assessment of the determinants of health in marginalised groups elusive. A classic argument advanced by scholars working on social determinants of health is that low income, and high income inequality, are associated with poor health outcomes (eg, a reduction in life expectancy).58 In the Arab world, we are unable to assess the relation between income inequality and mortality because Arab countries do not reliably report income inequalities and the available data exclude the most vulnerable populations. Assessment of the health of these groups is an urgent priority for researchers.

In the absence of cross-country data, local studies have shown that health-care and social protection systems favour the urban middle class in many Arab countries, excluding poor people, migrants, and residents of rural areas.59 Despite high levels of government investment in social protection (between 20% and 25% of national income in Egypt and Jordan), social protection schemes in the region have been characterised by “regressive redistribution from the poor to the urban middle class”.14 Notably, people employed in the informal sector are largely excluded from social protection schemes. In an analysis before the Arab uprisings, the informal sector employed 40–50% of north Africans (Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia) and more than 20% of Syrians.16 We are unable to disaggregate mortality on the basis of inclusion in social protection, thus we cannot assess the effect of these exclusions on mortality.

Conflict and war threaten to create new intrastate inequalities and further compromise the use of aggregate statistics. Chronic and recurrent conflict has plagued Iraq, the occupied Palestinian territory, Lebanon, and Somalia. Recently, the Arab uprisings have given way to armed conflict in Libya, Syria, and Yemen. Furthermore, external stakeholders have placed economic sanctions, seeking to weaken the government in power in Iraq (under Saddam Hussein) and the occupied Palestinian territory (since the election of Hamas). In Iraq, these sanctions had a crippling effect on the health of the population, especially for children with infant mortality rising from 47 to 108 per 1000 under sanctions from 1994 to 1999, and under-5 mortality rising from 56 to 131 per 1000.60 However, in Iraq under sanctions, childhood mortality was determined by region, rather than wealth, because people living under UN sanctions saw sharp rises in child mortality, whereas in the autonomous northern region of Iraq childhood mortality declined.60 Similarly, in the occupied Palestinian territory, malnutrition has been determined geographic ally, by physical access to food, sometimes obstructed by road closures, rather than the financial means to purchase food.61 With the uprisings, new waves of migration are taking place to escape violence, and new regional disadvantages are being created, perhaps most urgently among Syrian refugees. A paper later in this Series explores the crucial health issues that emerge from violent conflict and wars in the Arab world.5

Threats to health during the Arab uprisings

The Arab uprisings, while advocating for increased political accountability, economic opportunity, and equity, have had immediate detrimental effects on health in the region. The conflicts that have accompanied or followed uprisings in Syria, Egypt, Yemen, and Bahrain have led to increased social divisions, migration, political violence, and disruptions in education and health-care provision. These recent challenges come on top of the prolonged conflicts and insecurity in Iraq, Somalia, and the occupied Palestinian territory.5,62 Other countries, which have not had revolutionary movements, are under stress from the influx of refugees (especially Lebanon and Jordan with Syrian refugees), and thus might be deterred from advocating for reforms because of the instability and repression that has followed movements in other Arab countries. The Arab uprisings have escalated the level of conflict in the region, which has direct effects on the physical and psychological wellbeing of populations, the provision of medical resources, and the operation of medical staff. In Bahrain and Syria, for example, doctors caring for people affiliated with political oppositions have been targeted by the regimes and subjected to harassment and imprisonment.45 In Syria, hospitals have been taken over by the national army, and injured members of the opposition face arrest, and sometimes torture, if they seek medical care through formal channels.46 These breaches of medical neutrality, and the instability that accompanies political violence, are a threat to the provision of health care.

Conflict disrupts social inclusion, health-care access, and access to essential services. Social inclusion creates good social relationships and support networks, which increase people’s ability to cope with physical and mental illnesses.47 The increased vulnerability of minority groups (which had sometimes been protected by autocratic regimes) in the political upheavals is likely to further weaken their support communities. Existing social inequalities have also been amplified amid the uprisings. For example, the most high-income and elite populations have been able to travel to access medical services, whereas poor populations have found them selves increasingly competing for scarce resources, such as the case in Yemen and among Syrian refugees.48 Additionally, the instability after the uprising or migration to refugee camps is likely to have a negative effect on child nutrition and infant mortality, among other health indicators of these marginalised populations.49 The health effects of the Arab uprisings have neither been fully shown nor documented, and action by the humanitarian community and neighbouring governments will be guided by continual assessments.

The economic implications of the Arab uprisings might also affect population health. First, the strain on the economy, particularly in countries reliant on tourism, services, and export, has meant less available finance for health services on the part of the state. This situation is worsened by increased demand from citizens as populations become more vulnerable. Second, the economic crisis has meant a decrease in income and employment, which could lead to further reliance on compromised safety nets. Finally, economic hardship often pushes more people to work in the informal economy, where they do not have social security or access to health benefits.50

Improving governance and health

For the first time in the history of the Arab nations, a movement has galvanised to demand freedom and increase political inclusiveness and accountability. However, the initial hope for reform across the region has, in many places, been replaced by violence, fear, or a hardening of the traditional status quo. What the future holds for the Arab world is unclear. The trends shown here, and the published literature, suggest that focusing on building effective and inclusive governments in the region could have public health benefits. This is a familiar concept; the Lancet Series on health in the occupied Palestinian territory made the case that freedom is a prerequisite for delivery of health.55,62 Political freedom is probably no less essential to health in other Arab countries. In many Arab countries, so-called regime survival became a more important goal than development over the past decades. However, as the demands for truly accountable governance take hold, regime survival could come to depend on development, progress, and equity.

The papers in this Series point to several opportunities for health reform, each of them rooted in a call for improved accountability. Saleh and colleagues1 make recommendations to strengthen health-care delivery and quality by holding countries to the WHO parameters for health sector improvement. Abdul Rahim and colleagues3 make the case for adopting clear targets to control the regional epidemic of non-communicable disease and promote accountability toward meeting these targets, many of them based on international declarations. Dewachi and colleagues5 conclude that nations must be held accountable to their citizens to avoid the militarisation of health care. This message of trust through accountability is reinforced by El-Zein and colleagues2 in arguing that Arab governments must not view their rich natural resources as exclusive assets for a privileged class, but as ecological and cultural assets for this and future generations. In each paper in this Series, methods for improved accountability are regarded as essential to the health transformation of the Arab world.

The process of shaping the reform agenda is likely to be as important as the content in ensuring that governments remain accountable and effectively deliver services for all. The reform agenda should be shaped with broad input from citizens, such that the public, not entrenched elite populations, will benefit from the new arrangements. For example, Syria under Bashar al-Assad has been rife with cronyism, whereby those close to the regime largely owned and controlled the business sector.43 In Syria, before the 2011 uprising, a public–private partnership was proposed as a way to liberalise the health-care system, causing concern that this measure would make it difficult to enrol those working in the informal economy and other marginalised groups in medical insurance schemes—an issue already witnessed in neighbouring Lebanon.50 Often, these entrenched elite populations leading policy to deviate from the public interest have included health-care professions and their organisations.

International aid, military assistance, and oil purchases have supported many corrupt, ineffective, and non-inclusive governments across the Arab world. Additionally, international institutions, including the World Bank, have sometimes promoted policies that reinforce ineffective or irrelevant policies.52 International stakeholders supporting civil society organisations in the Arab world have often supported organisations affiliated with the ruling authoritarian regimes, thereby contributing to inequalities in political inclusion and restricting the effect of international capacity building efforts.53 Perhaps most crucially, international health and development organisations, including WHO and the World Bank, have been constrained by their reliance on these governments to collect information about health, inequality, and development in the region. Few countries in the region report any information about income inequality (available from authors on request) and about the state of their non-citizen populations. International health organisations should seek to measure the health of all people living in the Arab world, not only citizens.

To achieve better measures of health and ensure the delivery of health services when government services are weak, it is necessary for international stakeholders to liaise with civil society, activists, and, in some cases, political parties and revolutionary governments. This task is made particularly challenging because WHO has traditionally been constrained by its allegiance to working with governments, and many Arab states have penalised or criminalised international stakeholders working with NGOs. Foreign assistance, especially military assistance and cooperation, has also been crucial to the survival of authoritarian regimes in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Bahrain. In the USA, the Leahy Law requires that militaries receiving US assistance be deemed free of gross human rights abuses.54 US policy makers might be able to re-evaluate the nations they support that have used the military to suppress popular dissent, before military assistance and partnerships are renewed. Further, development assistance for health to the Arab world can provide medical relief and social protection for groups that are marginalised and excluded from access to government services.

The Arab uprisings have emphasised the demand for socioeconomic opportunity, equity, and freedom. At the same time, the instability that has accompanied or followed some of the Arab uprisings makes the poorest and most socially excluded people in society even more vulnerable. Efforts to increase the efficacy of governments and enhance political accountability can lead to reforms that expand and protect opportunities, health, and wellbeing across the Arab world. International stakeholders can provide support to measure the health of populations left outside the political process, the quality of health care, and the extent and nature of inequality in the region; all areas with sparse data. These measurements, done over time, can become a core part of operationalising accountability and informing the revolutions that have led to social reform and government upheaval. Additionally, the international community can support state and non-state stakeholders dedicated to improving the effectiveness of government and inclusion in the political process health, and should minimise support for stakeholders that have been complicit in the repression of freedom.

Table.

Demographic, health, and governance indicators for the Arab world

| Governance type | Year | Demographics | Health indicators | Governance indicators | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population* |

GDP/head (2012 US$) |

Oil rents (% of GDP)† |

Life expectancy (years) |

Under-5 mortality rate‡ |

Maternal mortality rate§ |

Government eff ectiveness |

Control of corruption |

Electoral democracy score |

|||

| Peninsula | |||||||||||

| Bahrain | Constitutional monarchy |

1990 2011 |

493 1324 |

$8582 ·· |

31·8% ·· |

72·5 75·2 |

20·5 10·0 |

89·3 ·· |

·· 0·65 |

·· 0·23 |

–10 −8 |

| Kuwait | Constitutional monarchy |

1990 2011 |

2088 2818 |

$8827 $62 664 |

36·0% ·· |

72·7 ·· |

16·9 10·9 |

47·9 ·· |

·· −0·04 |

·· 0·07 |

·· −7 |

| Oman | Absolute monarchy | 1990 2011 |

1868 2846 |

$6255 $25 221 |

40·8% ·· |

70·6 73·3 |

47·5 8·7 |

84·9 ·· |

·· 0·43 |

·· 0·08 |

−10 −8 |

| Qatar | Absolute monarchy | 1990 2011 |

474 1870 |

$15 537 $92 501 |

38·2% ·· |

74·1 78·2 |

20·2 7·7 |

48·8 ·· |

·· 0·83 |

·· 1·02 |

−10 −10 |

| Saudi Arabia | Absolute monarchy | 1990 2011 |

16 139 28 083 |

$7236 $20 540 |

41·9% 50·5% |

68·8 ·· |

42·7 9·2 |

94·3 ·· |

·· −0·43 |

·· −0·29 |

−10 −10 |

| United Arab Emirates | Constitutional monarchy |

1990 2011 |

1809 7891 |

$28 033 $45 653 |

24·9% 18·0% |

72·1 76·7 |

22·2 6·6 |

30·9 ·· |

·· 0·95 |

·· 1·08 |

−8 −8 |

| Yemen | Republic (president and prime minister) |

1990 2011 |

11 948 24 800 |

$473 $1361 |

23·0% 19·0% |

56·1 65·5 |

126·0 76·5 |

582·4 ·· |

·· −1·14 |

·· −1·18 |

−2 −5 |

| North Africa | |||||||||||

| Algeria | Republic (semi-presidential) |

1990 2011 |

25 299 35 980 |

$2452 $5244 |

8·3% 17·6% |

67·1 73·1 |

65·6 29·8 |

188·6 ·· |

·· −0·66 |

−0·56 ·· |

−2 2 |

| Comoros | Republic (presidential) | 1990 2011 |

438 754 |

$571 $809 |

·· ·· |

55·6 ·· |

121·7 79·3 |

449·9 ·· |

·· −1·74 |

·· −0·7 |

4 9 |

| Djibouti | Republic (semi-presidential) |

1990 2011 |

562 906 |

$804 ·· |

·· ·· |

51·4 57·9 |

121·6 89·5 |

606·5 ·· |

·· −0·96 |

·· −0·3 |

−8 2 |

| Egypt | Republic (semi-presidential) |

1990 2011 |

56 843 82 537 |

$759 $2781 |

14·7% 5·9% |

62·0 73·2 |

85·7 21·1 |

195·4 ·· |

·· −0·6 |

·· −0·68 |

−6 −2 |

| Libya | Republic (parliamentary) |

1990 2011 |

4334 6423 |

$6669 ·· |

32·4% ·· |

68·1 75·0 |

44·1 16·2 |

124·3 ·· |

·· −1·47 |

·· −1·31 |

−7 0 |

| Mauritania | Republic (semi-presidential) |

1990 2011 |

1996 3542 |

$511 $1151 |

·· ·· |

55·9 58·5 |

124·7 112·1 |

1295·4 ·· |

·· −0·9 |

·· −0·57 |

−7 −2 |

| Morocco | Constitutional monarchy |

1990 2011 |

24 781 32 273 |

$1033 $3054 |

0·0% 0·0% |

64·1 72·1 |

81·3 32·8 |

383·8 ·· |

·· −0·22 |

·· −0·26 |

−8 −4 |

| Somalia | Republic (parliamentary) |

1990 2011 |

6599 9557 |

$139 ·· |

·· ·· |

44·5 51·2 |

180·0 180·0 |

962·8 ·· |

·· −2·16 |

·· −1·72 |

−7 0 |

| Sudan | Republic (presidential) | 1990 2011 |

20 457 34 318 |

$468 $1234 |

0·0% 18·5% |

52·5 61·4 |

122·8 86·0 |

592·6 ·· |

·· −1·39 |

·· −1·3 |

−7 −2 |

| Tunisia | Republic (semi-presidential) |

1990 2011 |

8154 10 674 |

$1507 $4297 |

5·3% 4·4% |

70·3 ·· |

51·1 16·2 |

141·2 ·· |

·· 0·02 |

·· −0·21 |

−5 −4 |

| Levant | |||||||||||

| Iraq | Republic (parliamentary) |

1990 2011 |

18 194 32 962 |

·· $3501 |

·· 69·1% |

67·5 ·· |

46·0 37·9 |

211·7 ·· |

·· −1·15 |

·· −1·22 |

−9 3 |

| Jordan | Constitutional monarchy |

1990 2011 |

3170 6181 |

$1268 $4666 |

0·0% 0·0% |

70·4 ·· |

36·7 20·7 |

102·5 ·· |

·· 0·05 |

·· 0·01 |

−4 −3 |

| Lebanon | Republic (parliamentary) |

1990 2011 |

2948 4259 |

$963 $9904 |

0·0% 0·0% |

68·7 72·6 |

33·1 9·3 |

76·4 ·· |

·· −0·33 |

·· −0·91 |

·· 7 |

| Syria | Republic (semi-presidential) |

1990 2011 |

12 324 20 820 |

$999 ·· |

24·1% 14·4% |

71·1 ·· |

36·1 15·3 |

155·9 ·· |

·· −0·44 |

·· −0·97 |

−9 −7 |

| Occupied Palestinian territory |

Republic (presidential) | 1990 2011 |

1978 4019 |

·· ·· |

·· ·· |

68·0 ·· |

43·1 22·0 |

91·8 ·· |

·· −0·64 |

·· −0·83 |

·· ·· |

Complete dataset available from authors on request. Data from World Bank, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, WHO, and Polity IV project (panel 1). GDP=gross domestic product.

Population in 1000s.

Oil rent data from 2010–11.

Deaths per 1000 livebirths.

Deaths per 100 000 livebirths.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

Funding for this research was provided by The Freeman Spogli Institute For International Studies at the Global Underdevelopment Action Fund Stanford University (Stanford, CA, USA). The American University of Beirut (Beirut, Lebanon) provided additional support.

Footnotes

For more about the Arab Barometer Survey see http://www.arabbarometer.org

For more about the World Development Indicators see http://data.worldbank.org/topic

For more about the mortality statistics of the IHME see http://ghdx.healthmetricsandevaluation.org/

For more about the Worldwide Governance Indicators see http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/index.aspx#home

For more about the Polity IV Dataset see http://www. systemicpeace.org/polity/polity4.htm

Contributors

RB led the writing of the manuscript. LK contributed to writing the manuscript. MC wrote the panel on non-state providers and contributed to writing of the manuscript. JS managed the database and produced the graphs. SB wrote the panel on statistical methods (appendix) and guided the analysis. AJ provided the Arab Barometer data and gave input on the manuscript. PW and RG contributed to the writing, editing, and guiding of the manuscript throughout this project.

References

- 1.Saleh SS, Alameddine MS, Natafgi NM, et al. The path towards universal health coverage in the Arab uprising countries Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Yemen. Lancet. 2014 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62339-9. published online Jan 20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62339-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Zein A, Jabbour S, Tekce B, et al. Health and ecological sustainability in the Arab world: a matter of survival. Lancet. 2014 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62338-7. published online Jan 20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62338-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdul Rahim HF, Sibai A, Khader Y, et al. Non-communicable diseases in the Arab world. Lancet. 2014 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62383-1. published online Jan 20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62383-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakkash R, Afifi R, Maziak W. Research and activism for tobacco control in the Arab world. Lancet. 2014 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62381-8. published online Jan 20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62381-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dewachi O, Skelton M, Nguyen V-K, et al. Changing therapeutic geographies of the Iraqi and Syrian wars. Lancet. 2014 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62299-0. published online Jan 20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62299-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tell T. State formation and underdevelopment in the Arab world. Lancet. 2014 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62548-9. published online Jan 20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62548-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cammett M, Diwan I. The political economy of the Arab uprisings. In: Richards A, Waterbury J, Cammett M, Diwan I, editors. A political economy of the Middle East. 3rd edn. Colorado: Westview Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuhn R. On the role of human development in the Arab Spring. Popul Dev Rev. 2012;38:649–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2012.00531.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grant R, Keohane R. Accountability and abuses of power in world politics. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2005;99:29–43. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsai LL. Solidary groups, informal accountability, and local public goods provision in rural China. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2007;101:355–372. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Díaz-Cayeros A, Magaloni B, Ruiz-Euler A. Traditional governance, citizen engagement, and local public goods: evidence from Mexico. World Dev. 2013;53:80–93. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diaz-Cayeros A, Magaloni B. The Programa Nacional de Solidaridad (PRONASOL) in Mexico. World Bank; 2003. The Politics of Public Spending—Part II. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lemarchand R, Legg K. Political clientelism and development: a preliminary analysis. Comp Polit. 1972;4:149–178. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loewe M. Pension schemes and pension reforms in the Middle East and North Africa. Geneva: United Nations Research Institute for Social Development; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jabbour S, Yamount R, Hilal J, Nehmeh A. The political, economic and social context. In: Jabbour S, Giacaman R, Khawaja M, Nuwayhid I, editors. Public Health in the Arab World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alesina A, Devleeschauwer A, Easterly W, Kurlat S, Wacziarg R. Fractionalization. J Econ Growth. 2003;8:155–194. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Powell-Jackson T, Basu S, Balabanova D, McKee M, Stuckler D. Democracy and growth in divided societies: a health-inequality trap? Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alesina A, La Ferrara E. Ethnic diversity and economic performance. J Econ Lit. 2005;43:762–800. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drèze J, Sen A World Institute for Development Economics Research. The political economy of hunger. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGuire JW. Social policy and mortality decline in East Asia and Latin America. World Dev. 2001;29:1673–1697. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Filmer D, Pritchett L. The impact of public spending on health: does money matter? Soc Sci Med. 1999;49:1309–1323. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00150-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ross M. Is democracy good for the poor? Am J Pol Sci. 2006;50:860–874. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mansfield E, Snyder J. Democratization and the danger of war. Int Secur. 1995;20:5–38. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fukuyama F. State-building: governance and world order in the 21st century. Cornell University Press; New York. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gerring J, Thacker SC, Alfaro R. Democracy and human development. J Polit. 2012;74:01–17. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huber E, Stephens J. Development and crisis of the welfare state. Chicago: Chicago University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holmberg S, Rothstein B. Dying of corruption. Health Econ Policy Law. 2011;6:529–547. doi: 10.1017/S174413311000023X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anthonsen M, Löfgren Å, Nilsson K, Westerlund J. Effects of rent dependency on quality of government. Econ Gov. 2012;13:145–168. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaufmann D, Kraay A, Mastruzzi M. The worldwide governance indicators: methodology and analytical issues. [accessed Nov 12, 2012];2010 http://ssrn.com/abstract=1682130. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andrews M. CDDRL, Governance Project Seminar. Stanford University; 2013. Apr 25, Going beyond form-based governance indicators and ‘reforms as signals’ in development. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Acemoglu D, Johnson S, Robinson JA. The colonial origins of comparative development: an empirical investigation. Am Econ Rev. 2001;91:1369–1401. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahoney J. Colonialism and postcolonial development: Spanish America in comparative perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jamal A, Khatib L. Actors, public opinion, and participation. In: Lust E, editor. In the Middle East. Washington, DC: CQ Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alhamad L. Formal and informal venues of engagement. In: Lust-Okar E, Zerhouini S, editors. Political participation in the Middle East. Colorado: Lynne Rienner; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shehata D. The fall of the pharaoh: how Hosni Mubarak’s reign came to an end. Foreign Aff. 2011;90:26–32. [Google Scholar]

- 36.UNDP. Towards the rise of women in the Arab World. New York: United Nations; 2006. [accessed March 4, 2013]. Arab Human Development Report 2005. http://www.arab-hdr.org/publications/other/ahdr/ahdr2005e.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jamal A. Women, gender and public office: Arab states. In: Joseph S, editor. Encyclopedia of Women and Islamic Cultures. Brill Academic Publishers; 2007. [accessed March 4, 2013]. http://www.princeton.edu/~ajamal/encyclopedia_entry_EWIC_Jamal.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hausmann R, Tyson LD, Zahidi S. The global gender gap report. Geneva: World Economic Forum; 2013. [accessed March 4, 2013]. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GenderGap_Report_2013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jamal A. Stanford Comparative Politics Workshop 2012. Stanford, CA, USA: Stanford University; 2012. Apr 27, [accessed June 1, 2013]. United States military intervention and the status of women in the Arab World. http://politicalscience.stanford.edu/workshops/comparative-politics-workshop/cp-workshop-amaney-jamal. [Google Scholar]

- 40.UNDP. Challenges to human security in Arab countries. New York: United Nations Development Programme; 2009. [accessed March 4, 2013]. Arab Human Development Report 2009. http://www.arab-hdr.org/publications/other/ahdr/ahdr2009e.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 41.UNDP. The real wealth of nations: pathways to human development. New York: United Nations Development Programme; 2010. [accessed March 5, 2013]. Human Development Report 2010. http://hdr.undp.org/en/media/HDR_2010_EN_Complete_reprint.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heydemann S. Networks of privilege in the Middle East: the politics of economic reform. New York: Palgrave MacMillan; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haddad B. Business networks in Syria: the political economy of authoritarian resilience. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guetat I. The effects of corruption on growth performance of the MENA countries. J Econ Finance. 2006;30:208–221. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stork J. Bahrain’s medics are the targets of retribution. The Guardian (UK) 2011 May 5; [Google Scholar]

- 46.Médecins Sans Frontières. [accessed March 6, 2013];Syria: medicine as a weapon of persecution. 2012 Feb 8; http://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/publications/reports/2012/In-Syria-Medicine-as-a-Weapon-of-Persecution.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kouzis AC, Eaton WW. Absence of social networks, social support and health services utilization. Psychol Med. 1998;28:1301–1310. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kangas B. Traveling for medical care in a global world. Med Anthropol. 2010;29:344–362. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2010.501315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elgazzar HA. Raising returns: the distribution of health financing and outcomes in Yemen. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2011. [accessed April 14, 2013]. http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2011/02/13/000333037_20110213233057/Rendered/PDF/596160WP01publ1omesinYemen01PUBLIC1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sen K, Al-Faisal W. Syria: neoliberal reforms in health sector financing: embedding unequal access? Soc Med (Soc Med Publ Group) 2012;6:171–182. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Horton R. The occupied Palestinian territory: peace, justice, and health. Lancet. 2009;373:784–788. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60100-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tartir A, Wildeman J. Persistent failure: World Bank policies for the occupied Palestinian territories. Washington, DC: Al-Shabaka: The Palestinian Policy Network; 2012. [accessed April 14, 2013]. http://al-shabaka.org/sites/default/files/TartirWildeman_PolicyBrief_En_Oct_2012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Durac V. Entrenching authoritarianism or promoting reform? Civil society in contemporary Yemen. In: Cavatorta F, editor. Civil society activism under authoritarian rule: a comparative perspective. New York: Routledge; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Foreign Operations Appropriations Act. Sect 563, Public Law 106-429. USA. [accessed March 20, 2013];2001 http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-106publ429/html/PLAW-106publ429.htm.

- 55.Tabutin D, Schoumaker B. The demographic transitions: characteristics and public health implications. In: Jabbour S, Giacaman R, Khawaja M, Nuwayhid I, editors. Public Health in the Arab World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zogby J. Attitudes of Arabs: an in-depth look at social and political concerns of Arabs. Washington, DC: Arab American Institute; Zogby International; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Norris P. Making democratic governance work: the impact of regimes on prosperity, welfare, and peace. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilkinson RG, Pickett KE. Income inequality and population health: a review and explanation of the evidence. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:1768–1784. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lewando Hundt G, Alzaroo S, Hasna F, Alsmeiran M. The provision of accessible, acceptable health care in rural remote areas and the right to health: Bedouin in the North East region of Jordan. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ali MM, Shah IH. Sanctions and childhood mortality in Iraq. Lancet. 2000;355:1851–1857. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02289-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Batniji R, Rabaia Y, Nguyen-Gillham V, et al. Health as human security in the occupied Palestinian territory. Lancet. 2009;373:1133–1143. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abdelfattah D. CARIM AS 2011/68, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. San Domenico di Fiesole (FI): European University Institute; 2011. [accessed March 5, 2013]. Impact of Arab Revolts on Migration. http://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/19874/ASN2011-68.pdf?sequence=1. [Google Scholar]