Abstract

Introduction

The natural history of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) suggests that some remain slow in growth rate while many develop a more accelerated growth rate reaching a threshold for intervention. We hypothesized that different mechanisms are responsible for AAA that remain slow-growth and never become actionable versus the aggressive-AAA that require intervention may be reflected by distinct associations with genetic polymorphisms.

Methods

168 control and 141 AAA subjects all with ultrasound or CT imaging studies covering about 5 years were identified and the AAA growth rate determined from the serial imaging data. Genetic polymorphisms all previously reported as showing significant correlation with AAA: angiotensin 1 receptor (AT1R) (rs5186), interleukin-10 (IL-10) (rs1800896), methyl-tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) (rs1801133), low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) (rs1466535), angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) (rs1799752) and several MMP9 SNPs with functional effects on the expression or function were determined by analysis of the genomic DNA.

Results

AAA subjects were classified as slow-growth rate- (<3.25 mm /yr; n=81) vs. aggressive-AAA (growth rate >3.25 mm /yr, those presenting with a rupture, or those with maximal aortic diameter >5.5 cm (male) or >5.0 cm (female); n=60) and discriminating confounds between the groups identified by logistic regression. Analyses identified MMP9 p-2502 SNP (P=0.029, OR=0.54 (0.31-0.94)) as a significant confound discriminating between control- vs. slow-growth AAA, MMP-9 D165N (P=0.035) and LRP1 (P=0.034) between control vs. aggressive-AAA, and MTHFR (P=0.048, OR=2.99 (1.01-8.86)), MMP9 p-2502 (P=0.037, OR=2.19 (1.05-4.58), and LRP1 (P=0.046, OR= 4.96 (1.03-23.9)) as the statistically significant confounds distinguishing slow- vs. aggressive-AAA.

Conclusion

Logistic regression identified different genetic confounds for the slow-growth rate-and aggressive-AAA indicating a potential for different genetic influences on AAA of distinct aggressiveness. Future logistic regression studies investigating for potential genetic or clinical confounds for this disease should take into account the growth rate and size of AAA to better identify confounds likely to be associated with aggressive AAA likely to require intervention.

Introduction

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) once thought to affect 6% of men over the age of 60 and responsible for >2% of all death has shown a recent decline in the incidence in many parts of the world although the reported decrease in the incidence is not uniform throughout the world.1 Nevertheless, rupture of AAA remains a high mortality event and often the first manifestation of the disease2 and identification of pre-symptomatic patients with AAA and those likely to progress to a disease state requiring intervention remains a critical goal in reducing the mortality and morbidity from this disease.

The precise pathophysiology of AAA remains controversial but the disease’s progression can be divided into four steps: aneurysm initiation, formation, growth, and rupture.3 The growth rate of AAA correlates with the size of the aneurysm on presentation indicating that growth accelerates as the aneurysm enlarges.4,5 The AAA growth rate is increased in smokers while it is decreased in patients with diabetes.5–8 Size of the aneurysm appears to be a critical factor in predicting rupture or dissection and aneurysms exceeding 5.5 cm or greater (5.0 cm for female), or those demonstrating fast growth rate serve as a threshold for surgical intervention.4,9 A clinical indicator or a biomarker of aggressive aneurysms likely to progress to requiring intervention is currently lacking.

A genetic component to AAA was first documented by the observation that a positive history of AAA in a first-degree relative increased the risk of AAA by ten-fold.10 Susceptibility genes for AAA are considered likely predisposing factors but no pathogenic genes responsible for AAA have been identified and the diseases is likely multifactorial involving multivariable interactions among numerous genes and environmental factors. A recent analysis of a cohort of over 3 million individuals has reconfirmed male sex, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, history of smoking and a history of coronary artery disease as clinical risk factors associated with AAA.11

Various investigators have studied polymorphisms of specific genes encoding key molecules thought to be involved in AAA formation, primarily focusing on genes encoding structural proteins of the vessel wall, degrading enzymes such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), tissue inhibitors of MMPs (TIMPs), immuno-modulatory molecules, and molecules involved in hemodynamic stress consistent with our current understanding of the pathogenesis of AAA. AAA is often asymptomatic before rupture and occurs in older patient populations making the establishment of large cohorts for genetic association studies difficult. Reassessment of the literature by recent meta-analyses3,12,13 of allelic-association case-control studies have identified a number of potential genetic variation predispositions associated with AAA but suffer the limitation of statistically analyzing data obtained from different cohorts of subjects. In the current study, we sought to reassess the genotype association of 5 genetic variations reported in the literature as demonstrating significant correlation with AAA in a well-defined single population of cases and controls. The AAA subjects all had multiple imaging studies to allow assessment of the aneurysm growth rate allowing us to classify the subjects as slow- or fast-growth. Specifically, we performed a case: control logistic regression analysis of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) (rs1799752), angiotensin 1 receptor (AT1R) (rs5186), interleukin-10 (IL-10) (rs1800896), and methyl-tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) (rs1801133), all of which were reported in meta-analysis studies as showing significant correlation with AAA. We also included low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) (rs1466535) reported as showing association with AAA in a recent genome-wide association study14 and several MMP-9 SNPs (p-2502 (rs8113877), p-2118 (rs3918240), p-1702 (rs3918241), D165N (rs8125581), R279Q (rs17576), R668Q (rs17577)) with demonstrated effects on the expression or function of this protease, and with sufficient minor allele frequency in the northern Wisconsin population as recently reported by us.15

Materials & Methods

Selection of genetic variations included in the current study

The genetic variations (4 SNPs and 1 deletion) selected for this study were identified by recent meta-analyses to show significant association with AAA, and had also been reported to result in well-defined functional alterations of the gene products. We briefly summarize the known functional consequences of the selected genetic variations with a summary shown on Table I. Appendix Table I lists the published studies cited in the meta-analyses and the genotype distribution of the SNPs included in the current analysis. In addition, we included six MMP-9 SNPs with functional consequence on the expression or function of this molecule. We worked under the assumption that a given genetic variation may contribute to the association with AAA only if the underlying genetic variation resulted in a functional alteration of the gene expression or function. This approach provides a context, with which to demonstrate biological plausibility, and can help in the interpretation of genetic association with AAA.3

Table I.

The known functional consequences of genetic variations under study

| Gene | rs# | Polymorphism | Location | Functional Alteration | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE | rs1799752 | 287 bp Ins | Intron | Inc Enzymatic Activity | Rigat et al.38 |

| AT1R | rs5186 | A>C | 3’UTR | Inc Receptor Density | Martin et al.39 |

| IL-10 | rs1800896 | G>A | Promoter | Dec Promoter Activity | Bown et al.40 |

| LRP1 | rs1466535 | C>T | Intron | Inc Receptor Density | Bown et al.14 |

| MMP9 (p-2502) | rs8113877 | G>T | Promoter | Dec Promoter Activity | Duellman et al.15 |

| MMP9 (p-2118) | rs3918240 | C>T | Promoter | Inc Promoter Activity | Duellman et al.15 |

| MMP9 (p-1702) | rs3918241 | T>A | Promoter | Dec Promoter Activity | Duellman et al.15 |

| MMP9 (D165N) | rs8125581 | G>A | Exon | Dec Enzymatic Acitivty | Duellman et al.15 |

| MMP9 (R279Q) | rs17576 | G>A | Exon | Inc Enzymatic Acitivty | Duellman et al.15 |

| MMP9 (R668Q) | rs17577 | G>A | Exon | Inc Enzymatic Acitivty | Duellman et al.15 |

| MTHFR | rs1801133 | C>T | Exon | Dec Enzymatic Acitivty | Sharp et al.28 |

Genetic polymorphisms demonstrating significant correlation with AAA according to recent meta-analyses were selected. Additionally, MMP9 SNPs identified in our recent study were selected. The gene affected, the rs# polymorphism identification number, actual genetic polymorphism where the major allele > SNP allele, location and the functional alterations of the polymorphism when known, and the literature references are listed. bp Ins, base pair insertion; Inc, increase; Dec, decrease.

Selection of cases and controls

The Marshfield Clinic Personalized Medicine Research Project (PMRP) was established in 2001 and currently has a collection of over 20,000 subjects with clinical information and genomic DNA available.16 The PRMP database was searched with a sole inclusion criterion of patients with a diagnosis of aortic aneurysm (ICD-9 code between 441.3 and 441.5) at two dates and at least one confirmatory scan (MRI, contrast CT, or angiography) of the abdominal aortic aneurysm with a maximal dimension measurement of 3 cm or greater or at least one AAA rupture diagnosis code. Exclusion criteria included history of syndromic connective tissue diseases (e.g. Marfan and Ehlers-Danlos syndromes), presence of any non-aortic aneurysms, abdominal trauma, and syphilis. The cohort did not have sufficient data to discriminate subjects with inflammatory vs. atherosclerotic AAA17 or those with potential mycotic aneurysms. The same exclusion criteria applied to the control population derived from subjects enrolled in the PMRP. Since the subjects are selected from a well-defined patient population confirmed for the presence of aortic aneurysm by imaging studies, the incidence is 100% for this case-control genetic analysis circumventing loss of statistical power due to misdiagnosed subjects. Control subjects had no diagnoses of aortic aneurysm and must have had at least one scan with no aortic measurements greater than 2.5 cm. The well known confounds for aortic aneurysm such as male sex, patient age, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, history of coronary artery disease, and history of smoking were frequency matched in the selection of the controls to maximize detection of unaccounted genetic contribution to the disease (Table II). The recently documented negative correlation between AAA and diabetes was not known at the initiation of this study and the history of diabetes or the use of anti-hyperglycemic medication was not abstracted for the current cohort. Of the 168 AAA subjects available in the database, we restricted our model development to 141 subjects with multiple imaging studies with a median follow up duration of 5.06 years. We used the available serial imaging data to classify subjects to slow-AAA (n=81, mean growth rate of 1.08±0.08 mm/yr) vs. fast-AAA (n=24, mean growth rate of 5.10±0.55 mm/yr) based on the threshold growth rate of 3.25 mm/yr (Table II). These AAA growth rates are well within the range reported in a large meta-analysis.4 An aggressive-AAA group was defined as those with a fast-growth rate, those with a maximal aneurysm dimension exceeding 5.5 cm (male) or 5.0 cm (female) or those presenting with a rupture (n=9). In this sense, we use the term aggressive-AAA to describe a group of patients where the disease has become actionable or has progressed to the threshold of intervention. Of 39 subjects that had undergone repair present in the database, 32 were included in the aggressive-AAA group based on the growth rate (prior to intervention) or the aneurysm size inclusion criteria. The remaining 7 were excluded due to insufficient information to allow determination of the aneurysm growth rate. This allowed logistic regression modeling of possible contribution of the genetic confounds for control (n=168) vs. slow-growth AAA (n=81) or aggressive-AAA (n=60) comparisons. The transfer of genomic DNA from the Marshfield Clinics to UW Madison and genotyping was approved by the University of Wisconsin IRB protocol M2010-1315.

Table II.

Demographic and clinical variables of controls and AAA subjects

| Control (n=168) | Slow AAA (n=81) | Agg. AAA (n=60) | p-value Slow vs. Control |

p-value Agg vs. Control |

p-value Agg vs. Slow |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1929.97±0.60 | 1930.19±0.88 | 1929.57±0.99 | 0.853 | 0.731 | 0.640 |

| 0.74 | 0.80 | 0.67 | 0.371 | 0.250 | 0.100 |

| 29.3±0.4 | 28.8±0.5 | 29.2±0.8 | 0.395 | 0.856 | 0.627 |

| 0.18/0.20/0.62 | 0.15/0.17/0.68 | 0.17/0.23/0.60 | 0.652 | 0.830 | 0.593 |

| 0.58 | 0.68 | 0.53 | 0.123 | 0.555 | 0.079 |

| 71.7±0.9 | 69.2±1.0 | 70.5±1.7 | 0.080 | 0.533 | 0.505 |

| 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.945 | 0.523 | 0.621 |

| 63.4±0.9 | 63.0±1.4 | 64.0±1.5 | 0.787 | 0.747 | 0.637 |

| 0.83 | 0.88 | 0.80 | 0.374 | 0.636 | 0.216 |

| 62.5±0.8 | 61.7±1.2 | 62.9±1.3 | 0.597 | 0.817 | 0.534 |

| na | 7.33±0.52 | 6.37±0.54 | na | na | 0.202 |

| na | 0.70±0.03 | 0.69±0.05 | na | na | 0.927 |

| na | 5.66±0.53 | 4.10±0.64 | na | na | 0.065 |

| 1.80±0.07b | 4.30±0.12 | 6.24±0.19 | <0.001a | <0.001a | <0.001a |

| na | 1.08±0.08 | 5.10±0.55 | na | na | <0.001a |

A table comparing the demographic and clinical variables of the controls and cases. Date of birth rather than the current age was used because the former is a better measure of age at the entry of the subjects into the PMRP database and a better measure, allowing direct comparison between the cases and controls in this retrospective database study. Date of birth is given as year and a decimal value corresponding to the month/12. The maximum abdominal aortic dimension for the control group

is based on 66 subjects with reported abdominal aortic dimensions stated on the imaging reports and no subjects in this group had any mention of abdominal aortic abnormality on at least one imaging study of the abdominal aorta. Nominal variables are displayed as a percentage of total. P values determined by a Student t-test for ordinate variables and by a Chi square test for proportions.

Indicates statistical significance (p<0.05). Agg., aggressive; nev/cur/fmr, never/current/former; CAD, coronary artery disease; Dx, diagnosis, HTN, hypertension; HCE, hypercholesterolemia; R2, correlation coefficient for the linear regression of the growth curve; max aortic dm, maximum aortic dimension.

Genotyping and VTNR determination

Genomic DNA of the case and control subjects was genotyped for the SNPs of interest by the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center using the Kasper method (www.kbioscience.co.uk/reagents/KASP.html) with the primers listed in Appendix Table II. Ambiguous calls were re-genotyped resulting in detection of all genotypes for all subjects. For rs1799752 (ACE1) with a 287bp insertion/deletion polymorphism, a target DNA encompassing the polymorphism was PCR amplified using a FAM-tagged forward and a reverse primer, and the product size determined on an ABI capillary electrophoresis instrument. The PCR amplification using Titanium Taq DNA polymerase (Clontech Lab, Mountain View, CA) consisted of 95 C x 1 min, 38 cycles of 95 C x 1 min, 59 C x 1 min, and 72 C x 1 min, and a terminal extension at 72 C for 10 min.

Determination of AAA growth rate

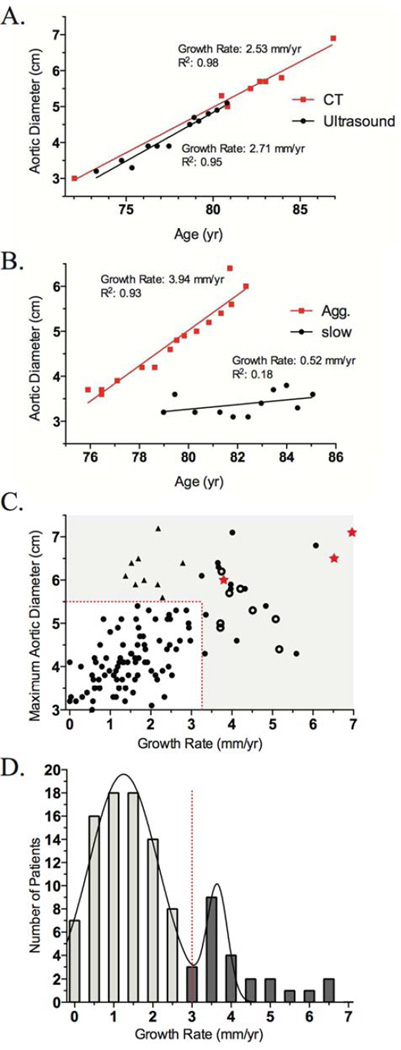

The subjects with AAA had serial imaging data available, either ultrasound or CT, with a mean follow up duration of 5 years. Both imaging techniques demonstrated consistent estimation of the aneurysmal size (Figure 1A) in agreement with the literature18 and both ultrasound and CT data were merged in the subsequent analysis. Although we did not observe in our cohort, others have reported that the estimate of AAA diameter by CT may be systematically larger than by ultrasound.5 The maximum aortic dimension determined by serial imaging studies for the subjects was plotted against time to estimate the growth rate of aneurysm by a linear regression through the data points. A linear regression through multiple imaging data should reduce much of the effect of inter-observer variability in the measurement of aortic dimension.19 Figure 1B shows examples for 2 subjects, one demonstrating a fast-growth rate (3.94 mm/yr) and a second with slow-growth rate (0.52 mm/yr). From the distribution of aneurysm growth rates, a threshold of 3.25 mm/yr was used for defining slow vs. fast AAA growth rate (Figure 1C,D). The overall R2 value for the linear regression for growth rate estimation of the 141 subjects was 0.69±0.03 and not improved by an exponential fit indicating that a linear estimate was adequate for our current dataset. We did not observe the episodic AAA growth of “fits and starts” especially for non-diabetic patients described in the literature7 but our analysis of growth rate will correspond to a linear time-averaged growth rate if the growth rate were not smooth over time.

Figure 1. Analysis of aneurysm growth rates in the AAA cohort.

A. Maximum aortic diameter from a single individual assessed by CT (square) and ultrasound (circle) plotted as a function of age. Both imaging methods gave consistent measurements of the aneurysm growth rate and R2 of the linear regression. B. Maximum aortic diameter vs. age of two AAA subjects with aggressive-(square) and slow-growth (circle) rates. C. Distribution of growth rates in the present cohort of n=141 subjects with serial imaging data of AAA. Symbols represent subset of subjects presenting with an acute AAA rupture (star), repaired by intervention (open circle), and those above the diameter threshold (triangle). The use of a linear curve fitting could result in an underestimate of a curvilinear growth rate reported by some but our preliminary analysis showed no significant increase in the correlation coefficient (R2 statistics) of exponential over linear curve fit. D. Patient aneurysm growth rate was binned and a threshold of 3.25 mm/yr was set to discriminate between slow- and fast- growth rate aneurysms. Ruptured (regardless of the size or rate of growth) or repaired aneurysms (above the growth rate or diameter threshold) were included in the aggressive-growth rate cohort but not in the double Gaussian fit of the growth rate.

Descriptive statistics and logistic regression modeling

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) and Linkage disequilibrium (LD) was calculated between each pair of SNPs based on observed and expected genotypes using the LD function in R (Appendix Figure 1). Descriptive statistics of genotype distributions were determined for cases and controls for additive (AA=2, Aa=1, aa=0), dominant (AA =1, Aa or aa=0), and recessive (AA or Aa =1, aa=0) coding where “A” is the major (wild type) allele and “a” is the SNP allele. A Chi-squared statistic was used to determine potential difference in the proportions of genotypes in cases and controls. Coding demonstrating the most significant difference between the cases and controls for the five polymorphisms examined here plus the 6 functionally significant MMP-9 SNPs identified in our previous work were tested for AAA association using logistic regression using the generalized linear model (glm) function in R based on the binomial family and coefficients of regression considered significant for p<0.05. The form of the fitted equation was: Ln(P/1-P)= A0 + Σ Ai*rsi where P=probability of AAA, A0= intercept (i.e. outcome not accounted for by the confounds), Ai are the regression coefficients, and rsi are the genetic variant confounds with no interaction terms allowed due sample size limitations. According to this coding, the odds ratio (OR) calculated is with respect to the wild-type allele.

Determination of whether to keep or eliminate a given confound in the logistic regression was based on a likelihood ratio test using the Anova function (test=‘Chisq’ option) in R. A reduced model was compared with the full model prior to the confound reduction and the eliminated confound was considered an insignificant contributor to the overall fit if the likelihood ratio test resulted in P>0.05. We chose the above ad hoc approach rather than the frequently used automatic selection of the confounds by a stepwise regression technique using Akaike information criteria because of the unresolved statistical meaning and the validity of this approach.20,21 The performance of the derived logistic regression model in terms of its ability to correctly classify true positive (benefit) from false positive (cost) was evaluated by the receiver-operator curve (ROC) and area under the ROC curve (AUC)22 using the ROC function (Epi package). Cross-validation of the model was performed by a 10-fold cross validation, (sometimes called rotation estimation),23 of the same dataset used for the model development using the cv.binary function (DAAG package). Statistical inference for the individual coefficients and OR of the final logistic regression model were based on a large sample approximation to the sample distribution where standard error of the estimate S.E.=sqrt (Σ1/ni) where ni are the numbers of observed data entries in a 2×2 contingency table.24

Results

At the time of study initiation the cohort of n=141 subjects with information on AAA growth rate divided into slow- and fast-growth rates were matched to controls for the clinical confounds including age, gender, history of coronary artery disease, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and smoking known to show association with AAA (Table II).

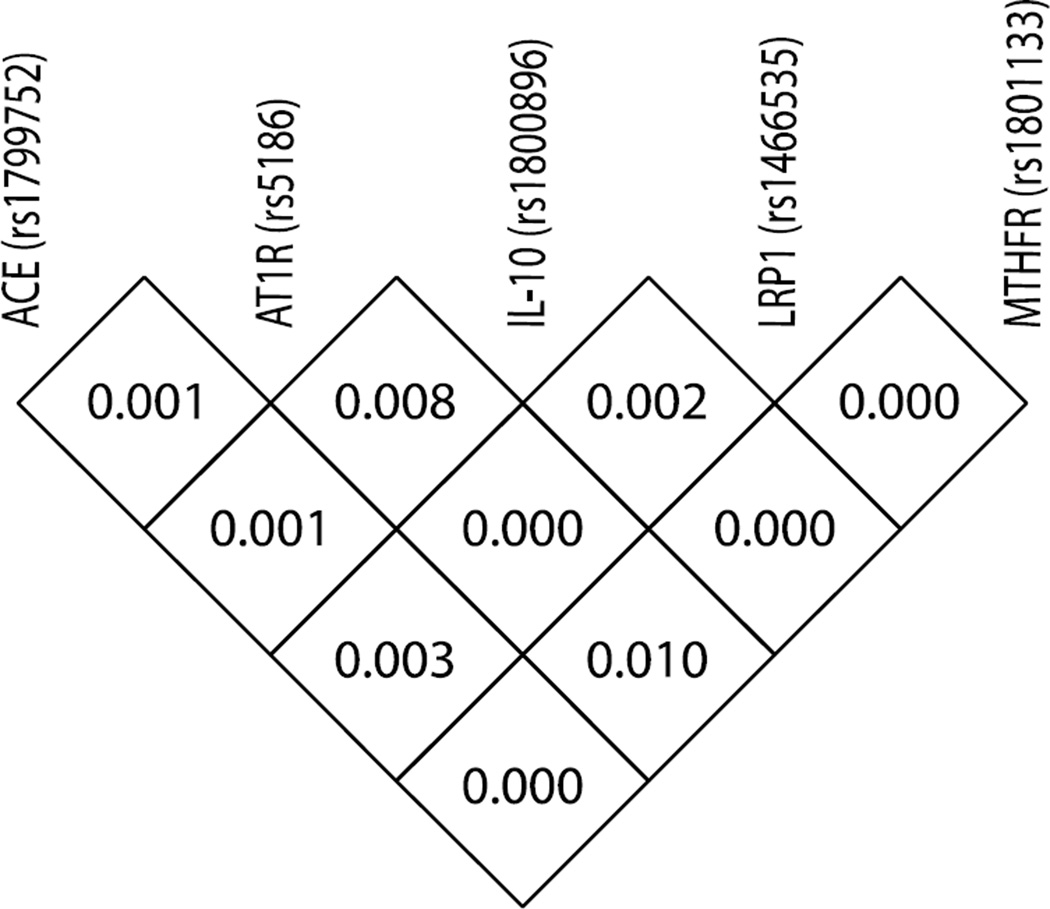

The demographic and clinical variables for this cohort have been published previously and only differ in the maximum aortic dimension as expected (see Figure 3A in Duellman et al.15). The 5 new genetic variants examined were in Hardy Weinberg equilibrium with no significant linkage disequilibrium with each other (Appendix Figure 1) suggesting the potential for these confounds to show independent association with AAA. The overall distribution of the genotypes for the 168 controls and 141 AAA subjects, for additive-, dominant-, and recessive-coding, are shown in Table III. Of note is the observation that none of the confounds by themselves, regardless of the coding, demonstrated statistically significant Chi-squared statistics (P<0.05) or unadjusted odds ratio (95% CI excluding 1.0) in our cohort including all AAA in apparent contradiction to the previously published results in the literature (Appendix Table I).

Table III.

Genetic variations in control and AAA subjects

| Gene | Coding | Genotype | Case (n=141) n (%) |

Control (n=168) n (%) |

p-value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE | Additive | DD | 45 (32%) | 43 (25%) | 0.39 | |

| DI | 69 (49%) | 85 (51%) | 0.34 | 1.29 (0.76–2.18) | ||

| II | 27 (19%) | 40 (24%) | 0.18 | 1.55 (0.82–2.95) | ||

| Dominant | DD | 45 (32%) | 43 (26%) | 0.22 | 1.36 (0.83–2.24) | |

| DI+II | 96 (68%) | 125 (74%) | ||||

| Recessive | DD+DI | 114 (81%) | 128 (76%) | 0.32 | 1.32 (0.76–2.29) | |

| II | 27 (19%) | 40 (24%) | ||||

| AT1R | Additive | AA | 73 (52%) | 77 (46%) | 0.52 | |

| AC | 54 (38%) | 75 (45%) | 0.26 | 1.32 (0.82–2.12) | ||

| CC | 14 (10%) | 16 (9%) | 0.20 | 1.08 (0.49–2.38) | ||

| Dominant | AA | 73 (52%) | 77 (46%) | 0.30 | 1.27 (0.81–1.99) | |

| AC+CC | 68 (48%) | 91 (54%) | ||||

| Recessive | AA+AC | 127 (90%) | 152 (90%) | 0.90 | 0.95 (0.45–2.03) | |

| CC | 14 (10%) | 16 (10%) | ||||

| IL-10 | Additive | AA | 42 (30%) | 48 (29%) | 0.71 | |

| AG | 60 (42%) | 77 (46%) | 0.41 | 1.25 (0.73–2.16) | ||

| GG | 39 (28%) | 43 (25%) | 0.55 | 1.20 (0.66–2.19) | ||

| Dominant | AA | 42 (30%) | 48 (29%) | 0.41 | 1.23 (0.75–2.03) | |

| AG+GG | 99 (70%) | 120 (71%) | ||||

| Recessive | AA+AG | 102 (72%) | 125 (74%) | 0.86 | 1.05 (0.64–1.72) | |

| GG | 39 (28%) | 43 (26%) | ||||

| LRP1 | Additive | CC | 66 (47%) | 67 (40%) | 0.32 | |

| CT | 62 (44%) | 78 (46%) | 0.38 | 1.24 (0.77–2.00) | ||

| TT | 13 (9%) | 23 (14%) | 0.15 | 1.74 (0.81–3.73) | ||

| Dominant | CC | 66 (47%) | 67 (40%) | 0.22 | 1.33 (0.84–2.09) | |

| CT+TT | 75 (53%) | 101 (60%) | ||||

| Recessive | CC+CT | 128 (91%) | 145 (86%) | 0.22 | 1.56 (0.76–3.21) | |

| TT | 13 (9%) | 23 (14%) | ||||

| MTHFR | Additive | CC | 66 (47%) | 79 (47%) | 0.71 | |

| CT | 53 (37%) | 68 (40%) | 0.28 | 1.07 (0.66–1.74) | ||

| TT | 22 (16%) | 21 (13%) | 0.51 | 0.80 (0.40–1.58) | ||

| Dominant | CC | 66 (47%) | 79 (47%) | 0.97 | 0.99 (0.63–1.55) | |

| CT+TT | 75 (53%) | 89 (53%) | ||||

| Recessive | CC+CT | 119 (84%) | 147 (87%) | 0.43 | 0.77 (0.41–1.47) | |

| TT | 22 (16%) | 21 (13%) |

Genotypes of the indicated SNPs and insertion/deletion polymorphism for ACE1 were determined and tabulated as Additive coding (AA=2, Aa=1, aa=0), Dominant coding (AA =1, Aa or aa=0), and Recessive coding (AA, or Aa =1, aa=0). The P value is the Chi squared statistics for the contingency table. For the additive coding both AA vs. Aa and AA vs. aa were calculated from the respective 2×2 contingency table.

Logistic regression analysis between control subjects without aneurysms vs. the slow-growth rate AAA group identified MMP-9 p-2502 as the only statistically significant (P<0.05) confounds (Table IV)). The ROC analysis revealed an AUC of 0.60 indicating that this model was only a moderate discriminator against control vs. slow-AAA groups. A 10-fold cross validation demonstrated an accuracy of 0.68. A similar analysis of control subjects vs. aggressive-AAA revealed MMP-9 D165N (P=0.035) and LRP1 (P=0.034) as statistically significant associations with an AUC of 0.60 and 10-fold cross validation of 0.74 (Table IV).

Table IV.

Results of logistic regression of the genetic confounds

| Slow AAA vs. Control | ROC AUC: 0.60 | |||

| Covariates | Coding | Coefficient±SE | p-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

| Constant | 0.23±0.39 | 0.558 | 1.25 (0.59–2.67) | |

| MMP9 p-2502 | Recessive | −0.62±0.28 | 0.029 | 0.54 (0.31–0.94) |

| MTHFR | Recessive | −0.67±0.36 | 0.065 | 0.51 (0.25–1.04) |

| Aggressive AAA vs. Control | ROC AUC: 0.60 | |||

| Covariates | Coding | Coefficient±SE | p-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

| Constant | −2.01±0.76 | 0.008 | 0.13 (0.03–0.60) | |

| MMP9 D165N | Dominant | −0.71±0.34 | 0.035 | 0.49 (0.26–0.95) |

| LRP1 | Recessive | 1.61±0.76 | 0.034 | 4.99 (1.13–22.10) |

| Slow AAA vs. A ggressive AAA | ROC AUC: 0.65 | |||

| Covariates | Coding | Coefficient±SE | p-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

| Constant | −3.23±0.98 | <0.001 | 0.04 (0.01–0.27) | |

| MTHFR | Recessive | 1.10±0.56 | 0.048 | 2.99 (1.01–8.86) |

| MMP9 p-2502 | Recessive | 0.79±0.38 | 0.037 | 2.19 (1.05–4.58) |

| LRP1 | Recessive | 1.60±0.80 | 0.046 | 4.96 (1.03–23.92) |

The acronyms for the genetic polymorphisms are as described in the Methods. The genetic coding indicates the coding used for the logistic regression resulting in the coefficients, P value, and the adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval). The area-under-curve (AUC) of the receiver-operator curve (ROC) (see Methods) was calculated as a measure of the model’s ability to discriminate the two groups under comparison. Bold text indicates statistical significance. SE, standard error; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Lastly, we sought genetic associations able to potentially discriminate between slow growth rate-and aggressive-AAA since this distinction is of critical clinical importance. A logistic regression model demonstrated the statistically significant association of MTHFR (P=0.048), MMP-9 p-2502 (P=0.037), and LRP1 (P=0.046) (Table IV). The AUC of the ROC curve was 0.65 demonstrating moderate discrimination between the groups and a10-fold cross validation estimate of accuracy of 0.62.

Discussion

The specific genetic variations in ACE (rs1799752), AT1R (rs5186), IL-10 (rs1800896), and MTHFR (rs1801133) considered in the current study have all been reported to show correlation with AAA recapitulated in recent meta-analyses, and LRP1 (rs1466535) has also been shown to associate with AAA in a genome wide association study. These genetic variants all result in known alterations of the gene expression and/or function and could play a plausible role in AAA based on our current understanding of the pathobiology of AAA. The surveillance of small AAA has demonstrated that some subjects with this disease remain stable for extended time with a slow aneurysm growth rate while others demonstrate aggressive increases in aneurysm size or require surgical intervention on presentation. Diabetes decreases the aneurysm growth rate4,7 and drugs such as cholesterol lowering drugs and the antibiotics doxycycline have been reported to decrease the AAA expansion rate although a recent meta-analysis concluded that no single drug used for cardiovascular risk reduction had a major effect on the growth or rupture of small aneurysms.5 However, no studies have investigated the association of genetic confounds with cohorts of AAA subjects grouped by growth rate. We investigated the association between genetic polymorphisms and AAA subjects with slow growth rate- (growth rate <3.25 mm/yr) and aggressive-subgroups (growth rate >3.25 mm/yr, presenting with a rupture, or aortic size exceeding the accepted threshold for intervention).

A control vs. slow-growth AAA comparison revealed significant association of MMP-9 and a trend towards significance for MTHFR. MMP-9 which targets elastin and collagen for degradation has been long considered a key contributor in the pathophysiology of AAA in the initiation of aortic wall inflammation followed by the proteolytic degradation and attenuation of the mechanical support of the aorta.25,26 Increases in elastin and collagen degradation products have been found to show positive correlation with aortic dilation with potential utility as a circulating biomarker for aneurysm progression.27 A promoter SNP at p-2502 (rs8113877) in the MMP-9 gene decreases the transcriptional activity;15 therefore, the wildtype genotype with normal transcriptional activity carries an increased risk. MTHFR is the primary enzyme for homocysteine metabolism. The C>T polymorphism (rs1801133) causes an alanine to valine substitution in the protein which results in a 70% reduction in enzyme activity, as measured in vitro, and manifests in vivo as a raised homocysteine level.28 High homocysteine levels induce serine proteases in vascular smooth muscle cells and cause alterations in arterial vasculature,29 induce elastolysis in vitro through the action of MMP2,30 and clinically correlates with AAA patients selected for surgical treatment.31 As such, the MTHFR wildtype genotype with normal enzymatic activity and lower homocysteine level will be protective compared to the SNP. Both genotype associations with slow-growth AAA revealed in this analysis demonstrate mechanistic feasibility.

The control vs. fast-growth AAA comparison revealed a significant correlation with a different MMP-9 D165N and a LRP1 SNP. The MMP-9 D165N SNP (rs8125581) located in the coding exon results in a decreased enzymatic activity15 and a negative-association with AAA makes functional sense. The LRP1 SNP (rs1466535) is located in the second intron of LRP1 with no known non-synonymous SNPs or splice-site variants in linkage disequilibrium with this site. There was a significant increase in LRP1 expression in CC (wild type) compared to TT (SNP) homozygotes potentially involving the transcription factor SREBP-1.14,32 LPR1 has multiple ligands with a wide variety of biological activity including effects on vascular smooth muscle cell migration and proliferation,33 and regulation of inflammation status, both pro and anti-inflammatory, through interaction with TGFβ, and regulation of MMP-9, TNFα, iNOS, and IL-6.34,35 The biological role of LRP1 in AAA is unknown at this time but we speculate, based on the increased OR for the wildtype genotype demonstrated in our association analysis, that the overall effect of LRP1 is protective against aggressive growth rate in AAA. The MTHFR SNP in conjunction with the MMP-9 p-2502 SNP and LRP1 affords distinction between AAA subjects with slow- vs. aggressive-growth rate. This information is particularly important since identification of the aggressive-growth rate subset of the AAA cohort will allow a closer interval of follow up imaging and possibly earlier intervention prior to the expansion of AAA to a point with a significantly increased risk. The clinical or economic utility of genetic stratification of AAA cannot be assessed without further studies but the cost of genotyping is trivial (~$50/ genotype) compared to the cost of even a single abdominal US scan (~$1,600) or CT scan (~$5,400) (cost estimates based on customary charges at the UW Hospital including the scan and professional read fee, personal communication with L. Seman, Department of Radiology). Further outcome studies are needed to see whether genetic screening can ever replace the currently standard imaging methods.

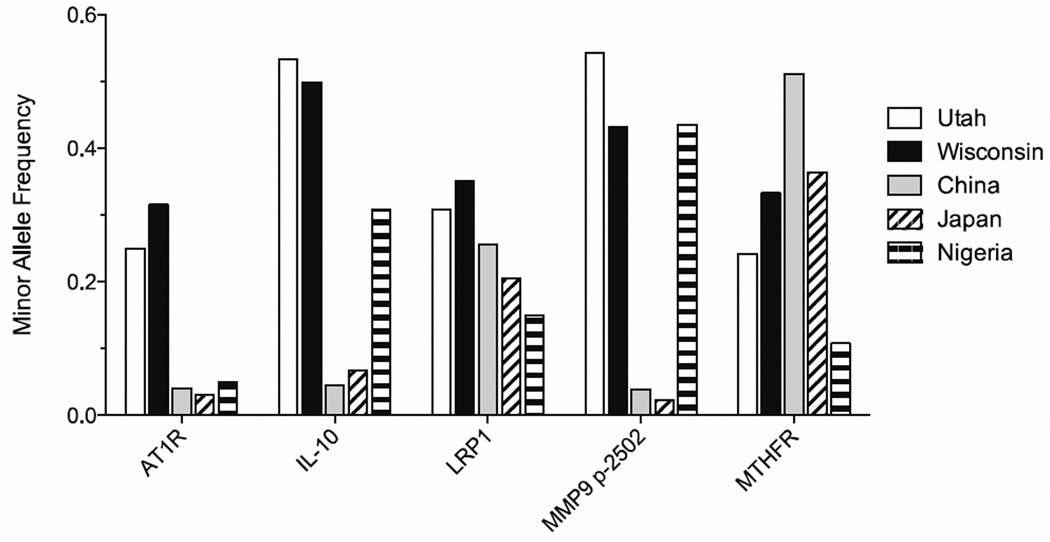

Lastly, we wish to comment on the apparent discrepancy in the unadjusted OR observed in our cohort and those previously published. A failure to replicate genetic association studies is a well-recognized problem with several potential reasons including confounding from population structure, misclassification of outcome, inappropriate matching of clinical confounds, and allelic heterogeneity.36 Alternatively, the inability to replicate may be due to a true heterogeneity in the genetic basis of the disease under consideration. Our cohort derived from a well-studied group of subjects with stringent criteria for entry both as a subject and a control, including radiographic data, and is unlikely to suffer from misclassification of outcome at the time of data collection. However, because AAA largely affects older subjects, it is possible that the control subjects could develop AAA later in life, which was unaccounted for. Confounding factors from population structure such as other genetic and environmental factors, and allelic heterogeneity leading to different pathogenic mechanisms for different populations are essentially impossible to assess when comparing results from one cohort to another. It is well known that allelic heterogeneity exists between ethnic groups and this information is now available for many genes through the international haplotype mapping (HapMap) project database (hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Appendix Figure 2 shows the known cohort-dependent minor allele frequency of 5 SNP variations for which information is available. The minor allele frequencies of some genetic polymorphisms show considerable cohort-dependent differences suggesting a strong allelic heterogeneity in the population documented in the HapMap database. Meta-analyses, despite well-recognized weaknesses, have contributed towards circumventing the severe limitation of small sample size of individual studies by combining data of multiple studies through statistical techniques.37 However, future meta-analyses should take into consideration the established fact of population variation in SNPs as well as the population from which the primary data arose and group the data for statistical analysis only when the populations show similar distribution of the genotype under consideration. This simple consideration should reduce group stratification error and the risk of over- extrapolating genetic association results from multiple studies derived from different populations. The statistical power of our current study is restricted by the small sample size, nevertheless, our result offers genetic polymorphism association as a method to segregate patients with AAA where the disease is likely to remain benign with a slow growth rate and those likely to require intervention. A future replication study to confirm and validate the findings of our current study should be drawn from an analogously well-defined population to reduce the risk of group stratification error.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Peggy Peissig and the Bioinformatics Core at the Marshfield Clinics Research Foundation, Marshfield, WI for database search and transfer of the genomic DNA.

Appendix Materials

Appendix Table I. Summary of published genetic polymorphism distributions in AAA.

The primary literature cited in the meta-analyses15–16 was reviewed and pertinent information summarized on this table. Some studies did not unambiguously specify the polymorphism under study by explicitly stating the polymorphism identification number (rs#), the genetic coding used for the model building was variable, and the different studies involved different subject populations.

| Gene | Alleles (rs#) | Study | Case (n) |

Cont. (n) |

Case (MAF) |

Cont. (MAF) |

OR (95% CI) | Coding | Region | Adj. OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE | I/D | Fatini et al1 | 250 | 250 | 0.63 | 0.49 | 1.90 (1.3–2.9) | Dominant | Italy | 2.4 (1.3–4.2) |

| (unreported) | Pola et al2 | 56 | 112 | 0.82 | 0.46 | 6.88 (3.38–14.02)a | Dominant | Italy | na | |

| Hamno et al.3 | 125 | 153 | 0.4 | 0.42 | 1.12 (0.62–2.03)a | Dominant | Japan | na | ||

| Korcz et al4 | 133 | 152 | 0.45 | 0.51 | 0.50 (0.20–1.25) | Dominant | Poland | 0.92 (0.40–2.10) | ||

| ACE | I/D | Jones et al5 | ||||||||

| (rs4646994) | Population#1 | 576 | 472 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 1.07 (0.78–1.47)a | Recessive | NZ | 1.28 (0.82–1.98) | |

| Population #2 | 298 | 912 | 0.52 | 0.5 | 1.32 (0.96–1.80)a | Recessive | UK | 1.26 (0.83–1.92) | ||

| Population #3 | 352 | 339 | 0.53 | 0.49 | 1.24 (0.88–1.75)a | Recessive | Australia | 1.40 (0.87–2.27) | ||

| ACE | I/D | Current Study | 133 | 168 | 0.44 | 0.49 | 1.59 (0.82–3.08) | Additive | US | na |

| (rs4646994) | ||||||||||

| AT1R | A1166C | Fatini et al1 | 250 | 250 | 0.3 | 0.28 | 1.41 (0.72–2.76) | Recessive | Italy | na |

| (rs5168) | Jones et al5 | |||||||||

| Population#1 | 576 | 472 | 0.3 | 0.27 | 1.31 (1.02–1.68)a | Recessive | NZ | 1.52 (0.85–2.75) | ||

| Population #2 | 298 | 912 | 0.34 | 0.27 | 1.57 (1.21–2.05)a | Recessive | UK | 1.79 (1.07–2.99) | ||

| Population #3 | 352 | 339 | 0.37 | 0.29 | 1.57 (1.13–2.18)a | Recessive | Australia | 1.89 (1.02–3.50) | ||

| Current Study | 133 | 168 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 1.13 (0.73–1.78) | Dominant | US | na | ||

| IL-10 | A1082G | Bown et al6 | 100 | 100 | 0.59 | 0.47 | 1.80 (0.92–3.64) | A allele | England | na |

| (rs1800896) | Bown et al7 | 389 | 404 | 0.53 | 0.45 | 1.50 (1.09–2.07) | A allele | England | 1.45 (0.84–1.92) | |

| Current Study | 133 | 168 | 0.47 | 0.49 | 1.20 (0.70–2.06) | Additive | US | na | ||

| LRP1 | CC | Bown et al8 | 6228 | 49,182 | 0.32 | 0.4 | 1.15 (1.10–1.21) | C allele | Europe | na |

| (rs1466535) | Current Study | 133 | 168 | 0.32 | 0.37 | 1.28 (0.87–2.02) | Dominant | US | na | |

| MTHFR | C677T | Brunelli et al9 | 58 | 60 | 0.48 | 0.39 | 0.69 (0.31–1.55)a | Dominant | Italy | na |

| (rs1801133) | Jones et al10 | 428 | 282 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 1.06 (0.79–1.44)a | Dominant | NZ | 1.12 (0.56–2.22) | |

| Ferrara et al11 | ||||||||||

| >60 yrs | 42 | 45 | 0.57 | 0.23 | 0.24 (0.10–0.61)a | Dominant | Italy | na | ||

| <60 yrs | 46 | 45 | 0.78 | 0.23 | 0.09 (0.03–0.24) | Dominant | Italy | na | ||

| Sofi et al12 | 438 | 438 | 0.43 | 0.38 | 0.78 (0.59–1.03) | Dominant | Italy | na | ||

| Strauss et al13 | 63 | 75 | 0.21 | 0.37 | 0.27 (0.13–0.54)a | Dominant | Poland | 0.27 (0.13–0.54) | ||

| Current Study | 133 | 168 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.65 (0.34–1.23) | Recessive | US | na |

Indicates odds ratio was calculated based on published case vs. control genotype frequencies. Cont, control; MAF, minor allele frequency; NZ, New Zealand; US, United States; Adj. OR, adjusted odds ratio.

Appendix References Cited:

Fatini C, Pratesi G, Sofi F, Gensini F, Sticchi E, Lari B, et al. Ace dd genotype: A predisposing factor for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005;29:227–232.

Pola R, Gaetani E, Santoliquido A, Gerardino L, Cattani P, Serricchio M, et al. Abdominal aortic aneurysm in normotensive patients: Association with angiotensin-converting enzyme gene polymorphism. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2001;21:445–449.

Hamano K, Ohishi M, Ueda M, Fujioka K, Katoh T, Zempo N, et al. Deletion polymorphism in the gene for angiotensin-converting enzyme is not a risk factor predisposing to abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1999;18:158–161.

Korcz A, Mikolajczyk-Stecyna J, Gabriel M, Zowczak-Drabarczyk M, Pawlaczyk K, Kalafirov M, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ace, i/d) gene polymorphism and susceptibility to abdominal aortic aneurysm or aortoiliac occlusive disease. J Surg Res. 2009;153:76–82.

Jones GT, Thompson AR, van Bockxmeer FM, Hafez H, Cooper JA, Golledge J, et al. Angiotensin ii type 1 receptor 1166c polymorphism is associated with abdominal aortic aneurysm in three independent cohorts. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:764–770.

Bown MJ, Burton PR, Horsburgh T, Nicholson ML, Bell PR, Sayers RD. The role of cytokine gene polymorphisms in the pathogenesis of abdominal aortic aneurysms: A case-control study. Journal of vascular surgery. 2003;37:999–1005.

Bown MJ, Lloyd GM, Sandford RM, Thompson JR, London NJ, Samani NJ, et al. The interleukin-10-1082 'a' allele and abdominal aortic aneurysms. Journal of vascular surgery. 2007;46:687–693.

Bown MJ, Jones GT, Harrison SC, Wright BJ, Bumpstead S, Baas AF, et al. Abdominal aortic aneurysm is associated with a variant in low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:619–627.

Brunelli T, Prisco D, Fedi S, Rogolino A, Farsi A, Marcucci R, et al. High prevalence of mild hyperhomocysteinemia in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm. Journal of vascular surgery. 2000;32:531–536.

Jones GT, Harris EL, Phillips LV, van Rij AM. The methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase c677t polymorphism does not associate with susceptibility to abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005;30:137–142.

Ferrara F, Novo S, Grimaudo S, Raimondi F, Meli F, Amato C, et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase mutation in subjects with abdominal aortic aneurysm subdivided for age. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2006;34:421–426.

Sofi F, Marcucci R, Giusti B, Pratesi G, Lari B, Sestini I, et al. High levels of homocysteine, lipoprotein (a) and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 are present in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm. Thromb Haemost. 2005;94:1094–1098.

Strauss E, Waliszewski K, Gabriel M, Zapalski S, Pawlak AL. Increased risk of the abdominal aortic aneurysm in carriers of the mthfr 677t allele. J Appl Genet. 2003;44:85–93.

Duellman T, Warren CL, Peissig P, Wynn M, Yang J. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 genotype as a potential genetic marker for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2012;5:529–537.

Thompson AR, Drenos F, Hafez H, Humphries SE. Candidate gene association studies in abdominal aortic aneurysm disease: A review and meta-analysis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;35:19–30.

McColgan P, Peck GE, Greenhalgh RM, Sharma P. The genetics of abdominal aortic aneurysms: A comprehensive meta-analysis involving eight candidate genes in over 16,700 patients. Int Surg. 2009;94:350–358.

Appendix Table II. List of primers used for genotyping the SNPs and PCR detection of the insertion/deletion genetic variant.

Kaspar genotyping was performed for SNP genotyping which includes two SNP-specific primers, one common primer, and reporter-oligonucleotides specifically annealing to the 5’ overhang sequence specific to the one or other SNP-specific product. The table lists the SNP-specific and the common primers.

| Kaspar primers for genotyping |

| rs1801133 (C/T SNP) MTHFR |

| Fwd: GAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCTAAAGCTGCGTGATGATGAAATCGG |

| Rev: GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTGAAAAGCTGCGTGATGATGAAATCGA |

| Common: CTTTGAGGCTGACCTGAAGCACTT |

| rs1800896 (G/A SNP) IL-10 |

| Fwd: GAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCTCAACACTACTAAGGCTTCTTTGGGAA |

| Rev: GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTAACACTACTAAGGCTTCTTTGGGAG |

| Common: GAGGTCCCTTACTTTCCTCTTACCTA |

| rs5186 (A/C SNP) AT1R |

| Fwd: GAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCTTTCTCCTTCAATTCTGAAAAGTAGCTAAT |

| Rev: GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTCTCCTTCAATTCTGAAAAGTAGCTAAG |

| Common: CCTCTGCAGCACTTCACTACCAAAT |

| rs1466535 (C/T SNP) LRP1 |

| Fwd: GAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCTCAGGGTCCATGGCAGAGAAAC |

| Rev: GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTGCAGGGTCCATGGCAGAGAAAT |

| Common: CTGCAACCTGGGAGCTATGGGAA |

| VNTR primer for PCR |

| rs1799752 (287 bp deletion) ACE1 |

| Fwd: CTGGAGACCACTCCCATCCTTTCT |

| Rev: GATGTGGCCATCACATTCGTCAGAT |

Further information on this method can be found at www.kbioscience.co.uk/reagents/KASP. The insertion/deletion polymorphism was distinguished using primers designed to PCR amplify the polymorphic region resulting in different sizes of the amplification product. VNTR=variable number tandem repeat.

Appendix Figure 1. The five genetic polymorphisms show little linkage disequilibrium. Additional genes chosen for genetic associate studies show minor linkage disequilibrium (LD) with each other. LD displayed as the D-index with 0 showing no linkage and 1 indicating perfect linkage. LD for the MMP-9 SNPs was reported in Duellman et al. (2012).14

Appendix Figure 2. Population-dependent variation in the minor allele frequency of genetic variations derived from the HapMap database. The bars are minor allele frequency retrieved from the HapMap database and calculated from the observed genotypes for our local patient cohort (Wisconsin), of the genes showing significant association with AAA based on multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions: Conception and design: TD, JY, Analysis and interpretation: TD, CW, JM, JY, Writing the article: TD, JY, Final approval of the article: TD, CW, JM, JY, Statistical analysis: TD, CW, Overall responsibility: JY

Funding Sources: This study was supported by the Wisconsin Genomic Initiative Demonstration Project grant (JY), Translational Cardiovascular Science Training Grant, T32 HL07936-12 (TD), Molecular and Cellular Pharmacology Training Grant NIH T32 GM008688 (TD), and the Bamforth Endowment Fund (JY) from the Department of Anesthesiology, UW Madison. UW Office of Clinical Trials is partly supported by grant 1UL1RR025011 from the Clinical and Translational Science Award program of the National Center for Research Resources, NIH. A part of JM’s time was supported by grants from Abbott, Covidien, Gore, Cook and Endologix.

References Cited

- 1.Sidloff D, Stather P, Dattani N, Bown M, Thompson J, Sayers R, et al. AneurysmGlobal Epidemiology Study: Public Health Measures can Further Reduce AbdominalAortic Aneurysm Mortality. Circulation. 2013 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakalihasan N, Limet R, Defawe OD. Abdominal aortic aneurysm. Lancet. 2005;365(9470):1577–1589. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66459-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson AR, Drenos F, Hafez H, Humphries SE. Candidate gene association studies in abdominal aortic aneurysm disease: a review and meta-analysis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;35(1):19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2007.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson SG, Brown LC, Sweeting MJ, Bown MJ, Kim LG, Glover MJ, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the growth and rupture rates of small abdominal aortic aneurysms: implications for surveillance intervals and their cost-effectiveness. Health Technol Assess. 2013;17(41):1–118. doi: 10.3310/hta17410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sweeting MJ, Thompson SG, Brown LC, Powell JT. Meta-analysis of individual patient data to examine factors affecting growth and rupture of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Br J Surg. 2012;99(5):655–665. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chun KC, Teng KY, Chavez LA, Van Spyk EN, Samadzadeh KM, Carson JG, et al. Risk factors associated with the diagnosis of abdominal aortic aneurysm in patients screened at a regional veterans affairs health care system. Ann Vasc Surg. 2014;28(1):87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2013.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Rango P, Cao P, Cieri E, Parlani G, Lenti M, Simonte G, et al. Effects of diabetes on small aortic aneurysms under surveillance according to a subgroup analysis from a randomized trial. Journal of vascular surgery. 2012;56(6):1555–1563. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.05.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schlosser FJ, Tangelder MJ, Verhagen HJ, van der Heijden GJ, Muhs BE, van der Graaf Y, et al. Growth predictors and prognosis of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Journal of vascular surgery. 2008;47(6):1127–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lederle FA, Johnson GR, Wilson SE, Ballard DJ, Jordan WD, Jr., Blebea J, et al. Rupture rate of large abdominal aortic aneurysms in patients refusing or unfit for elective repair. Jama. 2002;287(22):2968–2972. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.22.2968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johansen K, Koepsell T. Familial tendency for abdominal aortic aneurysms. Jama. 1986;256(14):1934–1936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kent KC, Zwolak RM, Egorova NN, Riles TS, Manganaro A, Moskowitz AJ, et al. Analysis of risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysm in a cohort of more than 3 million individuals. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52(3):539–548. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.05.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McColgan P, Peck GE, Greenhalgh RM, Sharma P. The genetics of abdominal aortic aneurysms: a comprehensive meta-analysis involving eight candidate genes in over 16,700 patients. Int Surg. 2009;94(4):350–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saratzis A, Abbas AA, Kiskinis D, Melas N, Saratzis N, Kitas GD. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: a review of the genetic basis. Angiology. 2011;62(1):18–32. doi: 10.1177/0003319710373092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bown MJ, Jones GT, Harrison SC, Wright BJ, Bumpstead S, Baas AF, et al. Abdominal aortic aneurysm is associated with a variant in low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89(5):619–627. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duellman T, Warren CL, Peissig P, Wynn M, Yang J. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 genotype as a potential genetic marker for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2012;5(5):529–537. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.112.963082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCarty CAWR, Giampietrao PF, Wesbrook SD, Caldwell MD. Marshfield clinics personalized medicine research project (PMRP): design methods and recruitment for a large population-based biobank. Personalized Medicine. 2005;2:49–79. doi: 10.1517/17410541.2.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hellmann DB, Grand DJ, Freischlag JA. Inflammatory abdominal aortic aneurysm. Jama. 2007;297(4):395–400. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolf YG, Johnson BL, Hill BB, Rubin GD, Fogarty TJ, Zarins CK. Duplex ultrasound scanning versus computed tomographic angiography for postoperative evaluation of endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Journal of vascular surgery. 2000;32(6):1142–1148. doi: 10.1067/mva.2000.109210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Long A, Rouet L, Lindholt JS, Allaire E. Measuring the maximum diameter of native abdominal aortic aneurysms: review and critical analysis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;43(5):515–524. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrell FE. Statistical Models. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henderson HV, Velleman PF. Building Multiple-Regression Models Interactively. Biometrics. 1981;37(2):391–411. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fawcett T. An introduction to ROC analysis. Pattern Recogn Lett. 2006;27(8):861–874. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Picard RR, Cook RD. Cross-Validation of Regression-Models. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1984;79(387):575–583. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mosteller F. Association and estimation in contingency tables. J Am Stat Assoc. 1968;63:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diehm N, Dick F, Schaffner T, Schmidli J, Kalka C, Di Santo S, et al. Novel insight into the pathobiology of abdominal aortic aneurysm and potential future treatment concepts. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2007;50(3):209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Golledge J, Muller J, Daugherty A, Norman P. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: pathogenesis and implications for management. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26(12):2605–2613. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000245819.32762.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindholt JS, Heickendorff L, Vammen S, Fasting H, Henneberg EW. Five-year results of elastin and collagen markers as predictive tools in the management of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2001;21(3):235–240. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2001.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharp L, Little J. Polymorphisms in genes involved in folate metabolism and colorectal neoplasia: a HuGE review. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(5):423–443. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jourdheuil-Rahmani D, Rolland PH, Rosset E, Branchereau A, Garcon D. Homocysteine induces synthesis of a serine elastase in arterial smooth muscle cells from multi-organ donors. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;34(3):597–602. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bescond A, Augier T, Chareyre C, Garcon D, Hornebeck W, Charpiot P. Influence of homocysteine on matrix metalloproteinase-2: activation and activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;263(2):498–503. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brunelli T, Prisco D, Fedi S, Rogolino A, Farsi A, Marcucci R, et al. High prevalence of mild hyperhomocysteinemia in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm. Journal of vascular surgery. 2000;32(3):531–536. doi: 10.1067/mva.2000.107563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Costales P, Aledo R, Vernia S, Das A, Shah VH, Casado M, et al. Selective role of sterol regulatory element binding protein isoforms in aggregated LDL-induced vascular low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 expression. Atherosclerosis. 2010;213(2):458–468. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boucher P, Gotthardt M, Li WP, Anderson RG, Herz J. LRP: role in vascular wall integrity and protection from atherosclerosis. Science. 2003;300(5617):329–332. doi: 10.1126/science.1082095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Overton CD, Yancey PG, Major AS, Linton MF, Fazio S. Deletion of macrophage LDL receptor-related protein increases atherogenesis in the mouse. Circ Res. 2007;100(5):670–677. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000260204.40510.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gaultier A, Arandjelovic S, Niessen S, Overton CD, Linton MF, Fazio S, et al. Regulation of tumor necrosis factor receptor-1 and the IKK-NF-kappaB pathway by LDL receptor-related protein explains the antiinflammatory activity of this receptor. Blood. 2008;111(11):5316–5325. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-127613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colhoun HM, McKeigue PM, Davey Smith G. Problems of reporting genetic associations with complex outcomes. Lancet. 2003;361(9360):865–872. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)12715-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noble JH., Jr. Meta-analysis: Methods, strengths, weaknesses, and political uses. J Lab Clin Med. 2006;147(1):7–20. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rigat B, Hubert C, Alhenc-Gelas F, Cambien F, Corvol P, Soubrier F. Aninsertion/deletion polymorphism in the angiotensin I-converting enzyme geneaccounting for half the variance of serum enzyme levels. J Clin Invest. 1990;86(4):1343–1346. doi: 10.1172/JCI114844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martin MM, Buckenberger JA, Jiang J, Malana GE, Nuovo GJ, Chotani M, et al. The human angiotensin II type 1 receptor +1166 A/C polymorphism attenuates microrna-155 binding. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(33):24262–24269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701050200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 40.Bown MJ, Lloyd GM, Sandford RM, Thompson JR, London NJ, Samani NJ, et al. The interleukin-10-1082 ‘A’ allele and abdominal aortic aneurysms. Journal of vascular surgery. 2007;46(4):687–693. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]