Abstract

Introduction

Clinical trials have shown that liraglutide effectively lowers glycated hemoglobin A1c (A1C) levels in adult patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D). However, no studies have evaluated the effectiveness of liraglutide by body mass index (BMI) in the United States (US) in clinical practice. This study examined liraglutide’s clinical effectiveness to lower A1C and body weight after 6 months in T2D patients stratified by baseline BMI.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study using the General Electric Centricity electronic medical records database. Adult patients with T2D (≥18 years and BMI≥ 25 kg/m2) and A1C >7% at baseline who started liraglutide between January 1, 2010 and January 31, 2013 and who did not use insulin or a glucagon-like peptide-1 analog 12 months before initiating liraglutide (N = 3,005) were selected. Changes from baseline, stratified by BMI, in A1C, body weight, A1C <7% goal attainment, and incidence of severe hypoglycemia at 6-month follow-up were examined.

Results

After 6 months, A1C levels decreased on average by 0.95%, 1.02%, 0.99%, and 0.84% for BMI categories 25.0–29.9 (n = 333), 30.0–34.9 (n = 793), 35.0–39.9 (n = 821), and ≥40.0 kg/m2 (n = 1,058), respectively (P = 0.30). The proportions of patients achieving A1C <7% at 6 months were 38.2%, 37.0%, 40.9%, and 41.0% (P = 0.54). The absolute body weight decreased by 1.5 to 4.0 kg across BMI and the rate of severe hypoglycemia (0.2%) was low.

Conclusion

Patients with T2D experienced statistically significant decreases in A1C and body weight after initiating liraglutide regardless of their BMI. Liraglutide reduced A1C equally well across baseline BMI in clinical practice in the US.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12325-014-0153-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Body mass index, Clinical effectiveness, Glycated hemoglobin, Liraglutide, Type 2 diabetes

Introduction

In recent years, diabetes mellitus has emerged as a global public health concern. Already the most common metabolic disorder, the global prevalence rates of diabetes have been increasing [1]. As of 2012, about 9.3% of the US population (29.1 million people of all ages) were affected by diabetes, which was the seventh leading cause of death in the United States (US) [2]. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) estimated the total costs of diagnosed diabetes to be $245 billion in 2012, which increased from $174 billion in 2007 [3]. Numerous complications are linked to diabetes including heart disease, stroke, hypertension, and kidney disease, which could potentially increase total costs incurred [2]. About 90–95% of all diabetes cases involve type 2 diabetes (T2D); therefore, the clinical and economic burdens incurred by T2D need to be investigated [2].

Liraglutide is a once-daily glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist used to improve glycemic control in adults with T2D. The liraglutide effect and action in diabetes (LEAD) pivotal clinical trials and the 1860 liraglutide dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor (LIRA-DPP-4) study have analyzed liraglutide against various active comparators across the treatment cascade [4–11]. These studies have demonstrated that liraglutide improves glycemic control with a low incidence of hypoglycemia, and has the additional benefit of clinically relevant weight loss.

High body mass index (BMI) is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular diseases and all-cause mortality for people with T2D [12, 13]. High BMI, also involved in the pathogenesis of T2D, can complicate the treatment of T2D by altering lipid levels, increasing insulin resistance, and raising blood glucose levels [13]. Several studies have examined changes in body weight, BMI, or body fat over a follow-up period for patients treated with liraglutide, given the effects of excess body weight in T2D patients. Substantial weight reduction [12–18] or BMI reduction [12, 17, 19] was found in several investigations. However, to date, no study has evaluated the relative clinical effectiveness of liraglutide to achieve glycemic control and weight loss in patients with T2D across baseline BMI levels in real-world clinical practice in the US. The objective of this study is to address this gap and examine liraglutide’s effectiveness on glycated hemoglobin A1C (A1C) (a minor component of hemoglobin to which glucose is bound), body weight, cholesterol, and blood pressure across different BMI levels.

Methods

Data Source

The data for this retrospective cohort study were obtained from the General Electric (GE) Centricity electronic medical record (EMR) database from January 1, 2009 to January 31, 2013. The GE Centricity EMR database contains data on more than 15 million individuals receiving care from more than 10,000 general practitioners. Forty-seven US states are represented and the average length of follow-up for individuals in the dataset is approximately 3 years. The GE Centricity EMR database contains detailed information that typical medical claims databases do not, such as patient demographic characteristics (patient height, weight, BMI, and smoking status) and certain laboratory values (cholesterol, A1C, and vital signs [blood pressure]). This general practitioner (ambulatory) EMR database provides complete information on all prescribed drugs for patients receiving care from that practice. Patient information from a variety of sources is routinely integrated into a common database and includes the number of patient encounters, insurance data, medication data that reflect not only prescription drug data, but also over-the-counter (OTC) medications prescribed by the physician, and historical drug use. However, the GE database is unable to provide specific dose information.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was exempt from ethics approval from an institutional review board and informed consent since it involved assessment of existing data and the subjects could not be identified directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects [45 CFR 46.101(b)].

Sample Selection

Patients were included in the study sample if they had T2D and a prescription order for liraglutide between January 1, 2010, and January 31, 2013. The index date was defined as the date of the first prescription order for liraglutide. T2D was defined using the following criteria: (1) at least one diagnosis for T2D based on an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code for 250.x0 or 250.x2; (2) one or more prescription orders for a non-insulin antidiabetic drug; or (3) two consecutive fasting blood glucose levels of ≥126 mg/dL [20]. These analyses focused on outcomes at 6 months after starting liraglutide (6-month post-index).

Patients were excluded if they (1) were not continuously enrolled during 12 months prior to the index date (pre-index period) and during 6-month follow-up, (2) had one or more prescription orders for any GLP-1 receptor agonist during baseline, (3) had one or more prescription orders for insulin use during baseline, (4) were less than 18 years of age, (5) had type 1 diabetes (ICD-9-CM codes: 250.x1 or 250.x3), polycystic ovarian syndrome (ICD-9-CM code 256.4) without the presence of T2D (ICD-9-CM codes 250.x0 or 250.x2), or were pregnant or had gestational diabetes (Supplemental Table 1) during any point in time during the pre-index period, (6) or their baseline A1C was ≤7% [21]. All patients were required to have at least one valid A1C measure at baseline (up to 45 days prior to the index date to up to 7 days after) and at least one valid A1C measure at their 6-month follow-up date (±45 days) for analyses of outcomes at 6 months follow-up. Due to very few (N = 36) patients in the baseline BMI category <25.0 kg/m2, this category was excluded from the analysis.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Demographic characteristics such as age, gender, race, geographic region (Midwest, Northeast, South, and West), and health plan type (Commercial, Medicare, Medicaid, Self-pay/Other, and Unknown) were captured at baseline. Baseline clinical characteristics included BMI and common diabetes-related complications identified using ICD-9-CM codes [22]. Clinical measures like A1C, weight, blood pressure (systolic blood pressure [SBP]; diastolic blood pressure [DBP]), lipid values (total cholesterol; high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL]), and occurrence of severe hypoglycemia were reported at both baseline and follow-up. Severe hypoglycemia was defined according to type of service and ICD-9-CM codes (Supplemental Table 2) [23] and/or a recorded glucose level of less than or equal to 40 mg/dL [24].

Patients may have had multiple measurements of the clinical outcomes during the baseline and follow-up periods. The baseline value was defined as the value closest to the index date (within 45 days prior to the index date to up to 7 days after). Values for outcomes at 6-month follow-up were defined as the measurements that were obtained on the day closest to 180-day post-index within a ±45-day window. All characteristics were stratified by baseline BMI categories, which were defined as 25.0–29.9, 30.0–34.9, 35.0–39.9, and ≥40.0 kg/m2.

Clinical Outcomes

The authors assessed the following clinical outcomes at 6-month follow-up: absolute changes (follow-up minus baseline) in A1C, weight, blood pressure, and lipids; relative changes (absolute change divided by baseline) in body weight; and the proportion of patients treated with liraglutide reaching A1C targets. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) target of A1C ≤6.5% and the American Diabetes Association (ADA) target of A1C <7% were used. Finally, the authors examined the occurrence of severe hypoglycemia at 6-month follow-up.

Analyses

Means and standard deviations (SD) were reported for continuous measures and percentages were reported for categorical measures. Statistical significance between baseline and follow-up values were assessed using the paired t-test for continuous measures and McNemar’s test for categorical measures. Analysis of variance (ANOVA), for continuous variables, and the Chi-square test, for categorical variables, were used to assess the statistical significance across the BMI categories. Differences with a P value of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

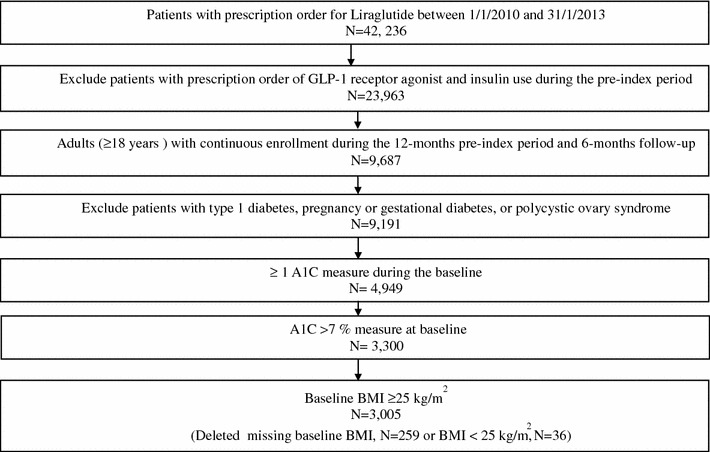

A total of 3,005 patients with T2D sub-optimally controlled at baseline (A1C >7%) initiating liraglutide between January 1, 2010 and January 31, 2013 were identified (Fig. 1). Table 1 shows the demographics and clinical characteristics of the sample stratified by baseline BMI. The mean age (SD) of the study sample was 54.7 (10.9) years and ranged from 52.1 (10.7) to 57.8 (11.1) years across the BMI categories (P < 0.01). More than one-third of patients in all BMI categories were in the 50–59 year age group. About 53% of the sample was female and this proportion, too, varied by BMI category (46.5–59.3%, P < 0.01). There were no statistically significant differences across BMI category by race/ethnicity, region, plan type, smoking status, or the presence of comorbid conditions.

Fig. 1.

Sample selection. A1C Glycated hemoglobin A1c, BMI body mass index, GLP-1 glucagon-like peptide 1

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics stratified by baseline BMI

| Baseline BMI kg/m2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 3,005) | 25.0–29.9 (N = 333) | 30.0–34.9 (N = 793) | 35.0–39.9 (N = 821) | ≥40.0 (N = 1,058) | P value* | |

| Age, years | 54.7 (10.9) | 57.8 (11.1) | 56.5 (10.7) | 55.0 (10.7) | 52.1 (10.7) | <0.01 |

| Age, % | ||||||

| 18–39 years | 8.9 | 6.0 | 5.4 | 7.8 | 13.2 | <0.01 |

| 40– 49 years | 21.8 | 16.2 | 19.7 | 21.6 | 25.3 | |

| 50–59 years | 36.4 | 35.1 | 36.6 | 35.8 | 37.1 | |

| 60–69 years | 24.1 | 28.2 | 26.6 | 25.9 | 19.6 | |

| 70–79 years | 7.8 | 11.4 | 10.3 | 8.0 | 4.4 | |

| 80+ years | 1.1 | 3.0 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 0.4 | |

| Gender, % | ||||||

| Female | 52.6 | 50.2 | 46.5 | 50.9 | 59.3 | <0.01 |

| Male | 47.4 | 49.8 | 53.5 | 49.1 | 40.7 | |

| Race/ethnicity, % | ||||||

| White | 63.9 | 61.6 | 61.3 | 64.3 | 66.4 | 0.10 |

| African American | 7.7 | 8.1 | 7.9 | 7.8 | 7.4 | |

| Hispanic | 1.8 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 1.1 | 2.1 | |

| Other | 3 | 4.5 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 1.6 | |

| Unknown | 23.6 | 23.4 | 25.1 | 23.4 | 22.6 | |

| Region, % | ||||||

| Midwest | 20.6 | 21.6 | 20.1 | 18.2 | 22.5 | 0.13 |

| Northeast | 19.2 | 18.6 | 17.8 | 19.0 | 20.7 | |

| South | 48.3 | 47.5 | 49.4 | 52.1 | 44.7 | |

| West | 11.9 | 12.3 | 12.7 | 10.7 | 12.1 | |

| Plan type, % | ||||||

| Commercial | 33.2 | 29.1 | 33.3 | 35.0 | 33.1 | 0.27 |

| Medicare | 15.6 | 17.7 | 17.2 | 14.7 | 14.6 | |

| Medicaid | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.9 | |

| Self-pay/other | 1.5 | 2.7 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 1.6 | |

| Unknown | 49.1 | 49.9 | 47.7 | 49.1 | 49.9 | |

| Smoking status, % | ||||||

| Never smoked | 25.0 | 31.8 | 23.0 | 25.2 | 24.2 | 0.13 |

| Former smoker | 30.6 | 26.4 | 32.0 | 30.6 | 30.9 | |

| Current smoker | 7.5 | 8.1 | 7.9 | 8.0 | 6.6 | |

| Other/unknown | 36.9 | 33.6 | 37.1 | 36.2 | 38.3 | |

| Complications, % | ||||||

| Retinopathy | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.04 |

| Nephropathy | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.37 |

| Neuropathy | 1.9 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 0.47 |

| Cerebrovascular | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.43 |

| Cardiovascular | 1.1 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.15 |

| PVD | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.42 |

| Diabetes medications, % | ||||||

| Sulfonylureas | 52.9 | 56.2 | 52.7 | 53.0 | 52.0 | 0.58 |

| Metformin | 79.8 | 82.3 | 80.3 | 78.7 | 79.4 | 0.54 |

| Other OADsa | 32.5 | 33.3 | 32.9 | 34.1 | 30.7 | 0.45 |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 38.3 (7.7) | 28.1 (1.3) | 32.6 (1.4) | 37.3 (1.4) | 46.6 (6.1) | <0.01 |

| Weight, kg | 110.4 (24.5) | 82.4 (10.8) | 95.2 (11.9) | 108.0 (13.8) | 132.6 (22.3) | <0.01 |

| A1C, % | 8.65 (1.4) | 8.66 (1.42) | 8.70 (1.47) | 8.66 (1.35) | 8.59 (1.37) | 0.358 |

| Lipids, mg/dL | ||||||

| Total cholesterol | 176.1 (43.0) | 179.0 (46.1) | 175.5 (44.7) | 177.0 (45.0) | 175.0 (38.8) | 0.62 |

| HDL | 41.9 (11.4) | 43.1(12.0) | 42.2(11.5) | 41.2(10.8) | 41.7 (11.4) | 0.19 |

| Blood pressure, mmHg | ||||||

| SBP | 129.8 (15.3) | 126.4 (14.3) | 128.7 (16.0) | 130.3(15.0) | 131.2 (15.1) | <0.01 |

| DBP | 78.1 (9.6) | 76.1 (9.3) | 77.2 (9.7) | 78.7 (9.4) | 79.0 (9.8) | <0.01 |

For appropriate variables, results presented as mean (SD)

BMI body mass index, PVD peripheral vascular disease, OADs oral antidiabetic medications, HDL high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure

* P values were determined using analysis of variance (ANOVA), for continuous variables, and the Chi-square test, for categorical variables, to assess statistical significance across BMI categories

aOther OADs include alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, dipeptidyl peptidase inhibitors, thiazolidinediones and meglitinides

The mean baseline BMI (SD) of the study sample was 38.3 (7.7) kg/m2 with group means of 28.1 (1.3), 32.6 (1.4), 37.3 (1.4), and 46.6 (6.1) kg/m2 for BMI categories 25.0–29.9, 30.0–34.9, 35.0–39.9, and ≥40.0 kg/m2, respectively. Average (SD) baseline A1C, which was 8.65% (1.4) for the entire sample, did not vary significantly by BMI category (P = 0.358). Total cholesterol and HDL measures at baseline also did not vary significantly by BMI category (P = 0.62 and P = 0.19, respectively). However, blood pressure did vary by BMI category, with blood pressure increasing as baseline BMI increased (P < 0.01). The proportion of patients who experienced severe hypoglycemia within the baseline period around the index date (45 days prior to 7 days after) was low (0.1%).

Clinical Outcomes

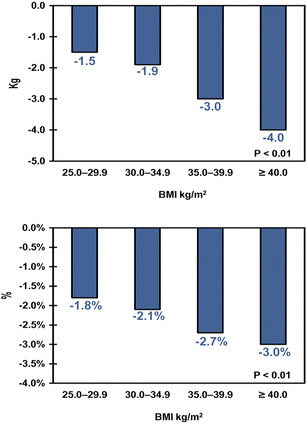

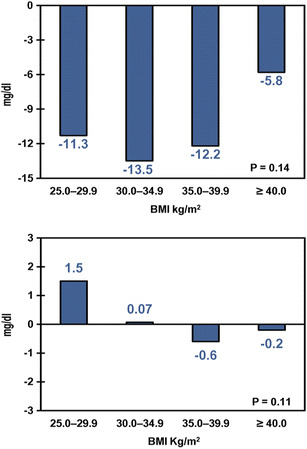

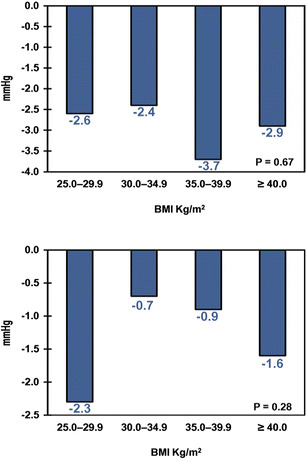

Table 2 shows the baseline and 6-month follow-up values for each clinical outcome for those patients who had available data at both time points; the fraction of the sample with data at both baseline and 6-month follow-up ranged from 23% for HDL to 55% for A1C. Liraglutide patients across all BMI categories experienced a statistically significant decrease in A1C (P < 0.01) at 6 months from baseline ranging from −0.84% to −1.02%. Similarly, liraglutide patients across all BMI categories experienced statistically significant decreases from baseline in absolute and relative body weight, total cholesterol, and SBP (all P < 0.05) at 6 months. The results were mixed for HDL and DBP—significant changes from baseline to 6 months were observed in only some BMI categories. The proportions of patients achieving the ADA target of A1C <7% were 38.2%, 37.0%, 40.9%, and 41.0% for BMI categories 25.0–29.9, 30.0–34.9, 35.0–39.9, and ≥40.0 kg/m2, respectively. None of these changes were statistically significantly different across BMI categories, except for body weight, in which case patients in higher BMI categories tended to lose more absolute and relative weight. In other words, for all clinical outcomes examined, except for body weight, patients experienced similar decreases in A1C, total cholesterol, and SBP regardless of their baseline BMI. These results are displayed graphically in Figs. 2, 3, 4, and 5. The proportion of patients with severe hypoglycemia at 6-month follow-up was low (0.0%, 0.7%, 0.0%, 0.2% for BMI categories 25.0–29.9, 30.0–34.9, 35.0–39.9, and ≥40.0 kg/m2, respectively).

Table 2.

Liraglutide clinical outcomes by baseline BMI at baseline and 6-month follow-up

| Clinical outcomes, mean (SD) | Baseline BMI, kg/m2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 25.0–29.9 | 30.0–34.9 | 35.0–39.9 | ≥40.0 | P value∆ | |

| A1C (N) | 1,649 | 186 | 454 | 440 | 569 | |

| Baseline A1C | 8.59 (1.36) | 8.58 (1.30) | 8.71 (1.47) | 8.58 (1.38) | 8.51 (1.26) | 0.12 |

| 6-month A1C | 7.65 (1.43)* | 7.63 (1.29)* | 7.70 (1.40)* | 7.59 (1.46)* | 7.67 (1.48)* | 0.71 |

| Absolute change in A1C from baseline | −0.94 (1.57)* | −0.95 (1.56)* | −1.02 (1.61)* | −0.99 (1.55) * | −0.84 (1.55)* | 0.30 |

| A1C ≤6.5% at 6 months | 20.6 | 18.3 | 20.9 | 21.1 | 20.6 | 0.87 |

| A1C <7.0% at 6 months | 39.5 | 38.2 | 37.0 | 40.9 | 41.0 | 0.54 |

| Weight (N) | 1,554 | 173 | 433 | 416 | 532 | |

| Baseline weight, kg | 109.6 (23.8) | 82.5 (10.2) | 95.0 (11.9) | 108.8 (13.9) | 131.0 (22.1) | <0.01 |

| 6-month weight, kg | 106.7 (23.5)* | 80.9 (10.8)* | 93.1 (12.8)* | 105.8 (14.5)* | 126.9 (22.4)* | <0.01 |

| Absolute change in weight from baseline, kg | −2.9 (5.7)* | −1.5 (4.8)* | −1.9 (4.2)* | −3.0 (4.8)* | −4.0 (7.3)* | <0.01 |

| Relative change in weight from baseline, % | −2.5 (5.7)* | −1.8 (5.8)* | −2.1 (4.4)* | −2.7 (4.4)* | −3.0 (6.1)* | <0.01 |

| TC (N) | 700 | 84 | 206 | 188 | 222 | |

| Baseline TC, mg/dL | 175.7 (43.0) | 176.7 (44.3) | 175.6 (43.7) | 177.9 (45.6) | 173.5 (39.8) | 0.75 |

| 6-month TC, mg/dL | 165.2 (40.1)* | 165.4 (39.5)* | 162.1 (40.3)* | 165.6 (42.4)* | 167.7 (38.3)* | 0.49 |

| Absolute change in TC from baseline, mg/dL | −10.4 (36.5)* | −11.3 (40.1)* | −13.5 (38.6)* | −12.2 (34.6)* | −5.8 (34.3)* | 0.14 |

| HDL (N) | 692 | 82 | 202 | 191 | 217 | |

| Baseline HDL, mg/dl | 41.8 (11.0) | 43.4 (12.8) | 42.1 (10.2) | 40.7 (10.9) | 41.9 (11.2) | 0.34 |

| 6-month HDL, mg/dl | 41.8 (11.3) | 44.9 (14.3)* | 42.2 (10.5) | 40.2 (10.9) | 41.7 (10.8) | <0.01 |

| Absolute change in HDL from baseline, mg/dL | −0.02 (6.6) | 1.5 (5.7)* | 0.07 (6.6) | −0.6 (6.5) | −0.2 (6.5) | 0.11 |

| SBP (N) | 1,549 | 172 | 430 | 411 | 536 | |

| Baseline SBP, mmHg | 129.9 (15.6) | 126.4 (14.7) | 128.9 (16.3) | 130.8 (15.5) | 131.2 (15.3) | <0.01 |

| 6-month SBP, mmHg | 127.0 (14.5)* | 123.8 (13.8)* | 126.5 (15.1)* | 127.0 (14.1)* | 128.4 (14.2)* | <0.01 |

| Absolute change in SBP from baseline, mmHg | −2.9 (16.5)* | −2.6 (15.6)* | −2.4 (16.8)* | −3.7 (15.8)* | −2.9(17.1)* | 0.67 |

| DBP (N) | 1,548 | 172 | 430 | 410 | 536 | |

| Baseline DBP, mmHg | 77.7 (9.8) | 76.2 (9.5) | 76.6 (9.9) | 77.9 (9.7) | 79.0 (9.7) | <0.01 |

| 6-month DBP, mmHg | 76.5 (9.6)* | 73.9 (8.7)* | 75.9 (9.9) | 77.0 (9.7) | 77.4 (9.4)* | <0.01 |

| Absolute change in DBP from baseline, mmHg | −1.26 (10.3)* | −2.3 (9.1)* | −0.7 (10.5) | −0.9 (9.9) | −1.6 (10.7)* | 0.28 |

Includes adults with type 2 diabetes with valid data at baseline and follow-up

DBP diastolic blood pressure, HDL high-density lipoprotein, SPB systolic blood pressure, TC total cholesterol

* Differences between baseline and 6 month follow-up values statistically significant (P < 0.05). P values were determined using paired t-test for continuous measures and McNemar’s test for categorical measures. ∆Statistical significance across BMI categories was determined through analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and Chi-square test for categorical variables

Fig. 2.

Absolute change in A1C from baseline to 6-month follow-up: (%). Statistical significance across body mass index (BMI) categories was determined through analysis of variance (ANOVA)

Fig. 3.

Changes in body weight from baseline to 6-month follow-up. Statistical significance across body mass index (BMI) categories was determined through analysis of variance (ANOVA). Upper panel absolute change in body weight (kg), lower panel relative change in body weight (%)

Fig. 4.

Changes in lipids from baseline to 6-month follow-up. Statistical significance across body mass index (BMI) categories was determined through analysis of variance (ANOVA). Upper panel absolute change in total cholesterol (mg/dL), lower panel absolute change in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL)

Fig. 5.

Changes in blood pressure from baseline to 6-month follow-up. Statistical significance across body mass index (BMI) categories was determined through analysis of variance (ANOVA). Upper panel absolute change in systolic blood pressure (mmHg), lower panel absolute change in diastolic blood pressure (mmHg)

Discussion

This study found that liraglutide lowered A1C as well as other key T2D-related complications equally well across baseline BMI categories 6-month post-initiation. This study, to the authors’ knowledge, is the first to evaluate liraglutide’s real-world effectiveness for different levels of BMI in clinical practice in the US. The results of this study could provide valuable insights to clinicians when prescribing liraglutide to patients with T2D across different BMI groups. The findings may also be useful to patients and formulary decision makers when choosing between available T2D medications. The overall results from this study are consistent with those of the pivotal LEAD trials. Pooled analyses of seven Phase III liraglutide trials found that A1C dropped by 1.05–1.15% from baseline, for 1.2 and 1.8 mg dosages, respectively [25]. Although these reductions were marginally larger than the overall A1C reduction of 0.94% (AIC reduction ranged from 0.84% and 1.02% depending on BMI categories) found in this current study, the results are comparable given the differences between the tightly controlled setting of a clinical trial and real-world clinical practice. This same meta-analysis of clinical trials reported that the absolute reduction in body weight from baseline stratified by liraglutide dose ranged from 1.69 kg (1.2 mg) to 2.27 kg (1.8 mg) [25]. Similarly, this study reported an overall absolute body weight reduction of 2.9 kg, ranging from 1.5 kg to 4.0 kg across BMI groups.

The results of this study, by baseline BMI, are consistent with two recently published studies. No differences were found in A1C reductions across six BMI categories before and after adjustment for baseline factors, such as baseline A1C and ethnicity, using Association of British Clinical Diabetologists (ABCD) nationwide data from the UK [26]. In addition, in a prospective follow-up study, Fadini et al. [15] found that liraglutide was equally effective in reducing A1C across baseline BMI tertiles measured at 4-month intervals, i.e., the A1C reductions across the BMI tertiles were not statistically significantly different from each other (P = 0.94).

Although the authors did not find evidence that A1C reductions were related to baseline BMI, the study did find that absolute and relative reductions in body weight were dependent on baseline BMI, which is consistent with the findings of Fadini et al. [15] of a statistically significant association between reductions in body weight (kg) at 4-month intervals and baseline BMI tertiles (P < 0.01), and with the findings of the UK study conducted by Ryder et al. [26] reporting an association between absolute weight reductions and greater baseline BMI resulting from liraglutide treatment. The results of this study for relative weight loss are also consistent with the meta-analysis of the LEAD pivotal trials conducted by Niswender et al. [13], namely, those patients with higher baseline BMI lost more relative body weight than patients with lower baseline BMI.

Other outcomes evaluated in this study included severe hypoglycemia, lipids, and blood pressure. The low rate of severe hypoglycemia that the authors found is consistent with liraglutide’s glucose-dependent mechanism of action and the results from the Bode et al. [27] meta-analysis. The authors’ findings, that changes in total cholesterol and HDL were independent of baseline BMI, are also, if not indirectly, consistent with the findings that total and HDL cholesterol were not related to changes in body weight reported by Fadini et al. [15]. The overall reductions in SBP and DBP, respectively, were also consistent with those reported by Bode et al. [27] of 2.87 and 1.40 mmHg (liraglutide 1.2 mg) and reductions of 2.99 and 1.47 mmHg (liraglutide 1.8 mg).

Study Limitations

There were several limitations of this study. First, although the authors identified over 3,000 eligible patients with baseline data, relevant laboratory and clinical measures at 6-month follow-up were unavailable for many of them, as expected in a real-world study setting. The impact of this limitation is unclear but the authors do note that the average baseline laboratory and clinical values for the subset of patients with follow-up data were similar to those of the baseline values for the entire sample. Second, it is not possible to determine if patients actually filled or refilled their prescriptions using the GE Centricity EMR database, so the authors could not examine adherence to therapy as an outcome nor were they able to adjust for adherence. Therefore, this study used an intent-to-treat approach. Third, because dose information is often missing from drug records in the GE Centricity EMR database, the authors could not stratify the analyses by liraglutide dose. Fourth, the analyses did not adjust for potential confounding by measured (e.g., age, gender, race) and unmeasured factors (e.g., diet, exercise). Fifth, a post hoc power calculation showed that the statistical power ranged from 40% to 50% for all clinical outcomes except body weight, for which the power was about 90%. The low statistical power may affect the ability to detect changes in clinical outcomes across BMI levels. However, as for other retrospective database studies, the authors had no control over the sample size after enforcing inclusion/exclusion criteria. Lastly, the authors may have misclassified baseline and 6-month follow-up measurements because the start and end dates of liraglutide that were recorded by physicians may have differed from actual start and end dates. However, it is unlikely that the possible discrepancy between actual and recorded dates would vary in any systematic way.

Conclusion

The authors found that liraglutide was equally effective in reducing A1C across baseline BMI categories suggesting that liraglutide may be effectively used for adult patients with T2D regardless of their BMI level. This study provides valuable insights for providers and formulary decision makers as it represents the first real-world evaluation of liraglutide’s effectiveness to lower A1C, body weight, cholesterol, and blood pressure across BMI groups in clinical practice in the US.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

All named authors meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship for this manuscript, had full access to all of the data in this study, take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis and have given final approval for the version to be published. Sponsorship and article processing charges for this study was funded by Novo Nordisk Inc. (Plainsboro, NJ, USA).

Conflict of interest

A. S. Chitnis is an employee of Evidera (Bethesda, Massachusetts, USA). M. L. Ganz is an employee of Evidera. N. Benjamin is an employee of Evidera. Evidera provides consulting and other research services to pharmaceutical, device, government, and non-government organizations. In this salaried position, A. S. Chitnis, M. L. Ganz and N. Benjamin work with a variety of companies and organizations and are precluded from receiving payment or honoraria directly from these organizations for services rendered. J. Langer is an employee of Novo Nordisk Inc. and is a shareholder of Novo Nordisk A/S (Bagsvaerd, Denmark). M. Hammer is an employee of Novo Nordisk Inc. and is a shareholder of Novo Nordisk A/S.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

This study was exempt from ethics approval from an institutional review board and informed consent since it involved assessment of existing data and the subjects could not be identified directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects [45 CFR 46.101(b)].

Funding

This study was sponsored by Novo Nordisk Inc., Plainsboro, NJ, USA.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes statistics report: estimates of diabetes and its burden in the United States, 2014. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Diabetes Information Clearinghouse (NDIC). National Diabetes Statistics, 2011. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda; 2011. http://diabetes.niddk.nih.gov/DM/PUBS/statistics/. Accessed December 2013.

- 3.American Diabetes Association (ADA). The Cost of Diabetes, 2012. American Diabetes Association, Alexandria; 2013. http://www.diabetes.org/advocacy/news-events/cost-of-diabetes.html. Accessed December 2014.

- 4.Buse JB, Rosenstock J, Sesti G, Schmidt WE, Montanya E, Brett JH, et al. Liraglutide once a day versus exenatide twice a day for type 2 diabetes: a 26-week randomised, parallel-group, multinational, open-label trial (LEAD-6). Lancet. 2009;374(9683):39–47. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60659-0. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60659-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeVries JH, Bain SC, Rodbard HW, Seufert J, D’Alessio D, Thomsen AB, et al. Sequential intensification of metformin treatment in type 2 diabetes with liraglutide followed by randomized addition of basal insulin prompted by A1C targets. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(7):1446–54. doi:10.2337/dc11-1928. 10.2337/dc11-1928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garber A, Henry R, Ratner R, Garcia-Hernandez PA, Rodriguez-Pattzi H, Olvera-Alvarez I, et al. Liraglutide versus glimepiride monotherapy for type 2 diabetes (LEAD-3 Mono): a randomised, 52-week, phase III, double-blind, parallel-treatment trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9662):473–81. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61246-5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61246-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marre M, Shaw J, Brandle M, Bebakar WM, Kamaruddin NA, Strand J, et al. Liraglutide, a once-daily human GLP-1 analogue, added to a sulphonylurea over 26 weeks produces greater improvements in glycaemic and weight control compared with adding rosiglitazone or placebo in subjects with type 2 diabetes (LEAD-1 SU). Diabet Med. 2009;26(3):268–78. doi:10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02666.x. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02666.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nauck M, Frid A, Hermansen K, Shah NS, Tankova T, Mitha IH, et al. Efficacy and safety comparison of liraglutide, glimepiride, and placebo, all in combination with metformin, in type 2 diabetes: the LEAD (liraglutide effect and action in diabetes)-2 study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(1):84–90. doi:10.2337/dc08-1355. 10.2337/dc08-1355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pratley RE, Nauck M, Bailey T, Montanya E, Cuddihy R, Filetti S, et al. Liraglutide versus sitagliptin for patients with type 2 diabetes who did not have adequate glycaemic control with metformin: a 26-week, randomised, parallel-group, open-label trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9724):1447–56. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60307-8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60307-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Russell-Jones D, Vaag A, Schmitz O, Sethi BK, Lalic N, Antic S, et al. Liraglutide vs insulin glargine and placebo in combination with metformin and sulfonylurea therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus (LEAD-5 met + SU): a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2009;52(10):2046–55. doi:10.1007/s00125-009-1472-y. 10.1007/s00125-009-1472-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zinman B, Gerich J, Buse JB, Lewin A, Schwartz S, Raskin P, et al. Efficacy and safety of the human glucagon-like peptide-1 analog liraglutide in combination with metformin and thiazolidinedione in patients with type 2 diabetes (LEAD-4 Met + TZD). Diabetes Care. 2009;32(7):1224–30. doi:10.2337/dc08-2124. 10.2337/dc08-2124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suzuki D, Toyoda M, Kimura M, Miyauchi M, Yamamoto N, Sato H, et al. Effects of liraglutide, a human glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue, on body weight, body fat area and body fat-related markers in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Intern Med. 2013;52(10):1029–34. 10.2169/internalmedicine.52.8961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niswender K, Pi-Sunyer X, Buse J, Jensen KH, Toft AD, Russell-Jones D, et al. Weight change with liraglutide and comparator therapies: an analysis of seven phase 3 trials from the liraglutide diabetes development programme. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15(1):42–54. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1326.2012.01673.x. 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2012.01673.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bailey T. Options for combination therapy in type 2 diabetes: comparison of the ADA/EASD position statement and AACE/ACE algorithm. Am J Med. 2013;126(9 Suppl 1):S10–20. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.06.009. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fadini GP, Simioni N, Frison V, Dal Pos M, Bettio M, Rocchini P, et al. Independent glucose and weight-reducing effects of Liraglutide in a real-world population of type 2 diabetic outpatients. Acta Diabetol. 2013;50(6):943–9. doi:10.1007/s00592-013-0489-3. 10.1007/s00592-013-0489-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katout M, Zhu H, Rutsky J, Shah P, Brook RD, Zhong J, et al. Effect of GLP-1 mimetics on blood pressure and relationship to weight loss and glycemia lowering: results of a systematic meta-analysis and meta-regression. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27(1):130–9. doi:10.1093/ajh/hpt196. 10.1093/ajh/hpt196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kesavadev J, Shankar A, Krishnan G, Jothydev S. Liraglutide therapy beyond glycemic control: an observational study in Indian patients with type 2 diabetes in real world setting. Int J Gen Med. 2012;5:317–22. doi:10.2147/ijgm.s27886. 10.2147/IJGM.S27886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mulligan CM, Harper R, Harding J, McIlwaine W, Petruckevitch A, McLaughlin DM. A retrospective audit of type 2 diabetes patients prescribed liraglutide in real-life clinical practice. Diabetes Ther. 2013;4(1):147–51. doi:10.1007/s13300-013-0025-z. 10.1007/s13300-013-0025-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elkhenini H, New JP, Summers LK, Syed AA. Liraglutide therapy in obese people with type 2 diabetes—experience of a weight management centre. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brixner DI, McAdam-Marx C, Ye X, Boye KS, Nielsen LL, Wintle M, et al. Six-month outcomes on A1C and cardiovascular risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with exenatide in an ambulatory care setting. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2009;11(12):1122–30. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1326.2009.01081.x. 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2009.01081.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Diabetes A. Standards of medical care in diabetes–2014. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(Suppl 1):S14–80. doi:10.2337/dc14-S014. 10.2337/dc14-S014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young BA, Lin E, Von Korff M, Simon G, Ciechanowski P, Ludman EJ, et al. Diabetes complications severity index and risk of mortality, hospitalization, and healthcare utilization. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(1):15–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ginde AA, Blanc PG, Lieberman RM, Camargo CA Jr. Validation of ICD-9-CM coding algorithm for improved identification of hypoglycemia visits. BMC Endocr Disord. 2008;8:4. doi:10.1186/1472-6823-8-4. 10.1186/1472-6823-8-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elliott MB, Schafers SJ, McGill JB, Tobin GS. Prediction and prevention of treatment-related inpatient hypoglycemia. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2012;6(2):302–9. 10.1177/193229681200600213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zinman B, Schmidt WE, Moses A, Lund N, Gough S. Achieving a clinically relevant composite outcome of an HbA1c of <7% without weight gain or hypoglycaemia in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of the liraglutide clinical trial programme. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14(1):77–82. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01493.x. 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01493.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryder REJ, Sen Gupta P, Thong KY, ABCD Nationwide Liraglutide Audit Contributors. Liraglutide is effective across a range of obese body mass indices; findings from the Association of British Clinical Diabetologists (ABCD) nationwide liraglutide audit. Poster 801. Abstract available at http://www.abstractsonline.com/Plan/ViewAbstract.aspx?mID=2978&sKey=92a4dee8-8b53-4c91-a416-f9b6a9f63306&cKey=46c8beac-fa07-4f65-ac90-48aaa2b0b1ea&mKey=2dbfcaf7-1539-42d5-8dda-0a94abb089e8. 48th European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) Meeting; October 1–5, 2012; Berlin, Germany.

- 27.Bode BW, Brett J, Falahati A, Pratley RE. Comparison of the efficacy and tolerability profile of liraglutide, a once-daily human GLP-1 analog, in patients with type 2 diabetes ≥65 and <65 years of age: a pooled analysis from phase III studies. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2011;9(6):423–33. doi:10.1016/j.amjopharm.2011.09.007. 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2011.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.