Abstract

Purpose

PS121912 has been developed as selective vitamin D receptor (VDR)–coregulator inhibitor starting from a high throughput screening campaign to identify new agents that modulate VDR without causing hypercalcemia. Initial antiproliferative effects of PS121912 were observed that are characterized herein to enable future in vivo investigation with this molecule.

Methods

Antiproliferation and apoptosis was determined using four different cancer cell lines (DU145, Caco2, HL-60, and SKOV3) in the presence of PS121912, 1,25-(OH)2D3, or a combination of 1,25-(OH)2D3 and PS121912. VDR si-RNA was used to identify the role of VDR during this process. The application of ChIP enabled us to determine the involvement of coregulator recruitment during transcription, which was investigated by rt-PCR with VDR target genes and those affiliated with cell cycle progression. Translational changes of apoptotic proteins were determined with an antibody array. The preclinical characterization of PS121912 include the determination of metabolic stability and CYP3A4 inhibition.

Results

PS121912 induced apoptosis in all four cancer cells, with HL-60 cells being the most sensitive. At sub-micromolar concentrations, PS121912 amplified the growth inhibition of cancer cells caused by 1,25-(OH)2D3 without being antiproliferative by itself. A knockout study with VDR si-RNA confirmed the mediating role of VDR. VDR target genes induced by 1,25-(OH)2D3 were down-regulated with the co-treatment of PS121912. This process was highly dependent on the recruitment of coregulators that in case of CYP24A1 was SRC2. The combination of PS121912 and 1,25-(OH)2D3 reduced the presence of SRC2 and enriched the occupancy of corepressor NCoR at the promoter site. E2F transcription factor 1 and 4 were down-regulated in the presence of PS121912 and 1,25-(OH)2D3 that in turn reduced the transcription levels of cyclin A and D thus arresting HL-60 cells in the S or G2/M phase. In addition, proteins with hematopietic functions such as cyclin-dependent kinase 6, histone deacetylase 9 and transforming growth factor beta 2 and 3 were down-regulated as well. Elevated levels of P21 and GADD45, in concert with cyclin D1 also mediated the antiproliferative response of HL-60 in the presence of 1,25-(OH)2D3 and PS121912. Studies at higher concentration of P121912 identified a VDR-independent pathway of antiproliferation that included the enzymatic and transcriptional activation of caspase 3/7.

Conclusion

Overall, we conclude that PS121912 behaves like a VDR antagonist at low concentrations but interacts with more targets at higher concentrations leading to apoptosis mediated by caspase 3/7 activation. In addition, PS121912 showed an acceptable metabolic stability to enable in vivo cancer studies.

Keywords: Vitamin D receptor, VDR–coregulator inhibitor, leukemia, cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, HL-60, 3-indolylmethanamine

Introduction

The inhibition of cancer cell growth in the presence of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25-(OH)2D3) was shown as early as 1979 [1, 2], and since then many groups have reported similar antiproliferative effects of VDR ligands in vitro and in vivo. This was followed by the systematic genomic analysis of 1,25-(OH)2D3 effects in cancer cells using microarrays, which was carried out using prostate, breast, colon, ovarian, and skin cancer cells, as well as leukemia cells [3–8]. VDR ligands, including the endogenous and most active ligand 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3) bind the vitamin D receptor (VDR) with high affinity and are responsible for the transcription of genes that regulate cell cycle, tumor growth, apoptosis, and cell differentiation as well as calcium homeostasis [9, 10]. Human clinical studies with 1,25(OH)2D3 and analogs are dose-limited because of hypercalcemia and hypercalciurea, which can cause psychosis, bone pain, calcification of soft tissue, coronary artery disease, and, in severe cases, coma and cardiac arrest [11, 12]. These side effects prompted the synthesis of thousands of 1,25(OH)2D3 analogs to develop VDR ligands with lower calcemic activity. In clinical trials, two synthetic VDR ligands that were developed to treat cancer did not achieve an acceptable therapeutic ratio [13, 14].

Recently, coregulator proteins (coactivators and corepressors) have been identified as transcriptional master regulators [15]. Among other functions, coregulators govern the activation and repression of VDR-mediated transcription depending on the gene, cell type, and VDR ligand [16–19]. We and others have introduced new classes of VDR modulators that in contrast to VDR ligand antagonists, bind liganded VDR and inhibit the interactions with coregulators [20–23]. The VDR ligand antagonists include the irreversible antagonist TEI-9647 [24], 25-carboxylic esters (ZK168218 and ZK159222) [25], 26-adamantly substituted antagonists (ADTT and analogs) [26], 22-butyl-branched VDR ligands [27] and non-secosteroid compounds that destabilize the active form of VDR [28, 29]. Newer irreversible VDR–coregulator inhibitors based on the 3-indolylmethanamine scaffold have a unique ability to selectively and covalently interact with VDR at its coregulator binding site [23]. It was shown that the interaction between VDR and steroid receptor coactivator 2 (SRC2) was selectively inhibit by 3-indolylmethanamine PS121912 and that at higher concentration PS121912 inhibited the growth of cancer cells. Herein, we present the effects of PS121912 that are mediated by VDR such as coregulator recruitment and regulation of transcription. In addition, VDR-independent effects at higher concentrations of PS121912 are presented.

Material and Methods

Reagents, Protein and Peptides

1,25(OH)2D3 was purchased from Endotherm, Germany.

Cell culture

HL-60, Caco2, DU145, and SKOV3 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD). All cell lines were maintained in DMEM/High Glucose (Hyclone, #SH3024301) or RPMI-1640 (ATTC, #30-2001), non-essential amino acids, penicillin and streptomycin, and 10% dialyzed FBS (Invitrogen, #26400-044. Cell cultures were maintained in 75 cm2 flasks and kept in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

Cytotoxicity Assays

Cancer cells were plated in quadruplicate in 384-well plates and treated with different concentrations of PS121912 followed by incubation for 18 h at 37 °C. CellTiter Glo (Promega) was added to quantify the number of live cells by luminescence using a Tecan M1000 reader. Controls were 3-dibutylamino-1-(4-hexylphenyl)propan-1-one (positive) and DMSO (negative). Three independent experiments were performed in quadruplicate, and data were analyzed using nonlinear regression with variable slope (GraphPadPrism).

Cell Proliferation Assay

Cancer cells were plated in 96-well tissue culture plates. After 5 h, cells were treated with DMSO, 1,25(OH)2D3 (20 or 100 nM) or PS121912 (0.5 or 2 µM) using 50H hydrophobic coated pin tool (V&P Scientific). The number of viable cells was determined each day in triplicate (5 days max) using CellTiterGlo. DMSO was used as control to determine the normal growth. The percentage live cells as compared to DMSO (negative control) and 3-dibutylamino-1-(4-hexylphenyl)propan-1-one (positive control). Three independent experiments were performed in quadruplicate. For siRNA studies, cells were plated in 6-well plates at 1.5M cell/well and treated for 24h with 300 µl of untreated DMEM containing 8 µl VDR siRNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-106692) or control siRNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-37007), LipofectamineTM LTX (12.5 µl), and PLUSTM reagent (4.3 µl).

Apoptosis assay

Cancer cells were plated in quadruplicate in 384-well plates and treated with different concentrations of PS121912 followed by incubation for 18 h at 37°C. Caspase-Glo 3/7 (Promega) was added to quantify the activity of caspase 3/7 by luminescence using a Tecan M1000 reader. Ketoconazole and DMSO were used as positive and negative control, respectively. Three independent experiments were performed in quadruplicate and data were analyzed using nonlinear regression with variable slope (GraphPadPrism).

ChIP

HL-60 cells were plated in 6-well plates at 2M cells per well and treated with either DMSO (0.03%) or inhibitor PS121912 (0.5 µM) in the presence or absence of 1,25(OH)2D3 (20 nM) for 18 hours. The DNA was prepared using an Imprint ChIP Kit (Sigma, CHP1) providing all internal controls. The antibodies used were VDR (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-1008), GRIP-1 (SRC2) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-6094), and NCoR (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-1609). The CYP24A1 promoter primers were FP 5’-AGCACACCCGGTGAACTC-3’and RP 5’- TGGAAGGAGGATGGAGTCAG-3’. SYBR Green Jumpstart TAQ Ready Mix (Sigma, s4438) was used for RT-qPCR in conjunction with thermal cycling conditions of initial 50 °C for 10 min, 95 °C for 5 min, and 50 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 30 s. ΔΔCt method was used to determine the % DNA occupancy in respect to input (3%). Standard errors of mean were calculated from two independent experiments performed in triplicate.

RT-qPCR

Cancer cells were incubated at 37 °C with either DMSO (0.03%) or inhibitor PS121912 (2 or 0.5 µM) in the presence or absence of 1,25(OH)2D3 (20 or 100 nM) for 18 hours in a 6 well plate. The cells were harvested using 0.3 ml of 0.25 % Trypsin (Hyclone, #SH3023601) and added to DMEM or RPMI media (1 mL). The cell suspension was spun down for 3 minutes at 700 rpm to form a cell pellet and the supernatant medium was carefully removed. The cell pellet was resuspended in 350 µL of RTL buffer (RNAeasy kit, Qiagen) with the addition of mercaptoethanol. The cells were lysed using a QIAshredder (Qiagen), and total RNA was isolated using the RNAeasy kit (Qiagen). A QuantiFast SYBR Green RT-PCR Kit (Qiagen) was used for the real time PCR following manufacturer’s recommendations. Primers used in these studies are as follows: GAPDH FP 5’-ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC-3’, GAPDH RP 5’-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3’; TRPV6 FP 5’-ATGGTGATGCGGCTCATCAGTG-3’, TRPV6 RP 5’-GTAGAAGTGGCCTAGCTCCTCG-3’, IGFBP3 FP 5’-CGCCAGCTCCAGGAAATG-3’, IGFBP3 RP 5’-GCATGCCCTTTCTTGATGATG-3’; CYP24A1 FP 5’-CTTTGCTTCCTTTTCCCAGAAT-3’, CYP24A1 RP 5’-CGCCGTAGATGTCACCAGTC-3’; P21 FP 5’-GGAAGACCATGTGGACCTGT-3’, P21 RP 5’-GGCGTTTGGAGTGGTAGAAA-3’, GADD45a FP 5’-GGAGAGCAGAAGACCGAAA-3’, GADD45a RP 5’-TCACTGGAACCCATTGATC-3’. RT-qPCR was carried out on a Mastercycler (Eppendorf). The thermal cycling conditions were an initial 50 °C for 10 min, 95 °C for 5 min, and 50 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 30 s. ΔΔCt method was used to measure the fold change in gene expression of target genes. Standard errors of mean were calculated from two independent experiments performed in triplicate. In addition, a TaqMan array human cyclins & cell cycle regulation (Life, #4414123) was used for each treatment (n = 2). The RNA was isolated as described above and RT-qPCR was carried out using Quantifast Probe RT-PCR Kit (Qiagen).

Antibody array

Apoptosis antibody array was performed using RayBio Human Apoptosis Antibody Array G Series (Cat no. AAH-APO-G1-8). HL-60 cells were plated in 4 well-plates and treated with DMSO, 1,25(OH)2D3 (20 nM), and 1,25(OH)2D3 (20 nM)/PS121912 (500 nM). Cells were incubated for 18 hours. Cell lysate was collected using 1X Cell Lysis Buffer provided in RayBio Human Apoptosis Antibody Array kit. The glass chip was assembled as recommended by the manufacturer. 100 µL of blocking buffer was added to completely cover the array area followed by 30 min incubation. After decanting the blocking buffer, 100 µL of cell lysate solution was added and incubated for 18 hours at 4 °C. After decanting the sample, the antibody array area was washed 2 times with washing buffer I and 2 times with washing buffer II. The array area was incubated with 70 µL biotin-conjugated antibodies for 2 hours at room temperature. After washing with washing buffer I & II, 70 µL of HiLyte Plus-conjugated streptavidin was added and incubated 2 hours at room temperature. After the washing steps, the antibody array chip was dissembled and scanned using a fluorescence imager (Molecular Imager FX, Biorad). The blot intensity was quantified with “Quantity One” software.

Metabolic stability

The assay was performed with total incubation volume of 200 µL containing 181.8 µL of phosphate buffer (100 mM) pH 7.4, 10 µL of NADPH Regenerating System Solution A (BD Bioscience Cat. No. 451220), 2 µL of NADPH Regenerating System Solution B (BD Bioscience Cat. No. 451200), 0.2 µL of PS121912 (10 µM final concentration) and 5 µL of human pooled liver microsome (0.5 mg/mL final concentration). Initially, phosphate buffer, NADPH Regenerating System Solution A & B, and PS121912 were added and incubated at 37 C for 5 min. The reaction was initiated by adding liver microsomes. Aliquots of 30 µL were taken at time intervals of 0, 5, 10, 15, 30 and 60 minutes. Immediately, 30 µL of cold methanol solution containing 10 µM of internal standard caffeine was added and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 2 min to quench the reaction. The ratio of caffeine and PS121912 was measured by HPLC and % PS121912 remaining was calculated. By plotting the log of % remaining against the time interval, the linear slope (k) was determined. The metabolic rate (k*C0/C), half-life (log2/k), and internal clearance (V*k) were calculated as well. k is the slope, C0 is the initial concentration of PS121912 (µM), C is the concentration of microsomes (mg/mL), and V is the volume of incubation (µL)/protein in the incubation (mg). Data were presented as mean and standard error. Statistical significance was analyzed by Student’s T-test using the GraphPad Prism software (version 4.0). P value smaller than 0.01 ( P < 0.01) were considered significant.

P450 inhibition assay

The CYP3A4 inhibition assay was performed using Vivid® CYP3A4 Green Screening kit (Cat no. P2857) using the manufacturer’s suggested protocol. First, the Master Pre-Mix was prepared by diluting P450 BACULOSOMES Plus Reagent (50 µL) and 100X Vivid Regeneration System (100 µL) in 4850 µL of 1X Vivid CYPP450 Reaction Buffer. 50 µL of Pre-Mix mixture and 40 µL of 1X Vivid CYPP450 Reaction Buffer were added into each well of 96-well plate. Using 50H hydrophobic coated pin tool (V&P Scientific), PS121912 was added serial-diluted into the 96-well plate followed by a 10 min incubation period. During this incubation period, a 10X mixture of Vivid Substrate DBOMF and Vivid NADP+ mixture was prepared as suggested by manufacturer. The reaction was initiated by adding 10 µL of the 10X Vivid substrate and NADP mixture. The plate was incubated for 30 minutes, and fluorescence was measured using an excitation/emission wavelength of 550/590, respectively. DMSO was used as a negative control, and ketoconazole was used as a positive control to measure the activity of CYP3A4. Each concentration was measured in triplet with two independent measurements. IC50 values were determined by non-linear regression using GraphPadPrism.

Results

We investigated the acute cytotoxic effect of PS121912 with a panel of cancer cells consisting of DU145 (prostate), Caco2 (colon), HL-60 (monocytes), and SKOV3 (ovary) (Fig.B). The cell viability was determined in the presence of PS121912 after 18 hours. The results are depicted in Fig.1C.

Fig. 1.

Effects of PS121912 in DU145 (prostate), Caco2 (colon), HL-60 (monocytes), and SKOV3 (ovarian). A) Chemical structure of PS121912; B) Induction of apoptosis after 18 hours by PS121912 for different cancer cells. The initiation of apoptosis was determined by quantifying the activity of caspase 3/7 using a luminescence-based assay (Caspase-Glo 3/7, Promega); C) Determination of cell viability after 18 hours assessed by quantification of cellular ATP using a luminescence-based assay (CellTiter-Glo, Promega). Three independent experiments were performed in quadruplicate for each dose response, and the data were analyzed by non-linear regression using GraphPad Prism.

The cancer cell lines exhibited different sensitivities towards PS121912. Whereas DU145 cells showed little cell death at 100 µM PS121912, all other cells were not viable at that concentration. In contrast, HL-60 was the most sensitive cancer cell line with an LD50 value of 6.8 ± 1.5 µM for PS121912. SKOV3 and Caco2 exhibited the same intermediate sensitivity towards PS121912. The distinction between necrosis and possible apoptosis as a mechanism of cell death was determined by quantifying the activity of caspase 3/7 [30]. PS121912 activated the executioner caspases with an EC50 of 4.7 ± 2.3 µM. The inversely proportional relationship between cell death and activation of caspase 3/7 is indicative of apoptotic cell death of HL-60 cells in the presence of PS121912. At higher concentrations, the activation of caspase 3/7 was also observed for other cancer cells in accordance with a weaker toxicity observed for these cells.

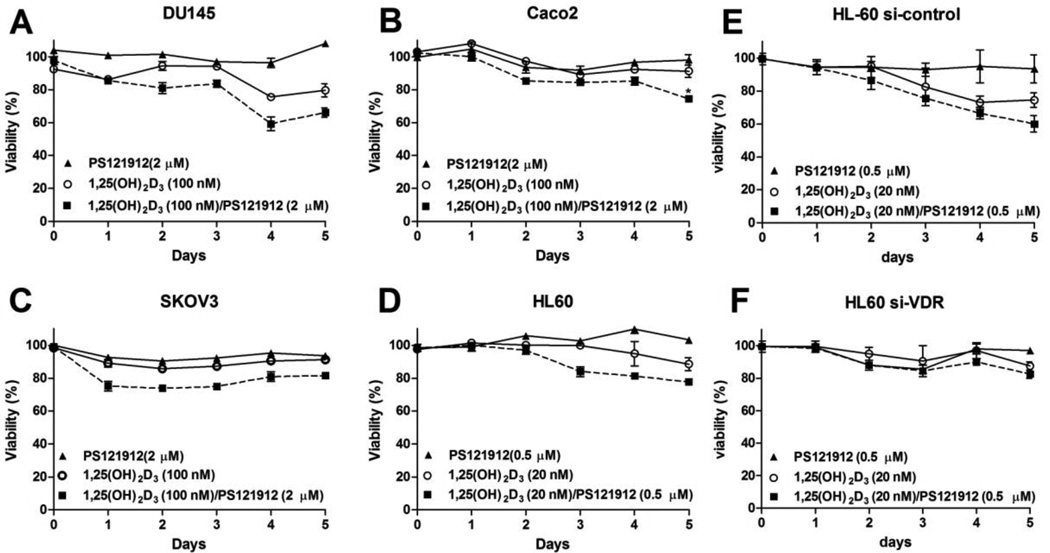

PS121912 was developed as a selective and potent VDR–coregulator inhibitor to modulate VDR-mediated transcription in the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3 [23]. At high concentrations, 1,25(OH)2D3 itself induces antiproliferation, which was studied in concert with PS121912 for four different cancer cell lines (Fig2.).

Fig. 2.

Proliferation studies in the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3 and PS121912 using A) DU145 prostate cancer; B) Caco2 colon cancer; C) SKOV3 ovarian cancer; D) HL-60 monocytes; E) HL-60 transfected with control siRNA; F) HL-60 cells transfected with VDR siRNA. Cells were treated once and incubated 5 days. The viability of cells was measured each day using luminescence-based cell viability assay. The % viability as compared to positive and negative control was plotted against time. Each cell line was treated with DMSO, 1,25(OH)2D3 , PS121912, or a co-treatment of 1,25(OH)2D3 and PS121912. Student t-test was used to determine the significance between 1,25(OH)2D3 and the co-treatment on day 5.

In contrast to DU145 and HL-60, 100 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 had a minor antiproliferative effect in SKOV3 and Caco2 cells. The concentration of PS121912 was selected at such that minimal antiproliferative effects were observed in the absence of 1,25(OH)2D3. This approach was designed to identify effects of PS121912 that depend on the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3. Different PS121912 concentrations were tested with various cancer cells and a non-antiproliferative concentration of 2 µM PS121912 was determined for DU145, Caco2, and SKOV3 (Fig.2 A–C). For the more sensitive HL-60 cells, a PS121912 concentration of 500 nM was low enough to not cause any antiproliferation (Fig.2D). Importantly, when cancer cells were treated with a combination of 1,25(OH)2D3 and PS121912 a significantly reduced viability was observed after five days for Caco2 cells in comparison with the sole treatment of 1,25(OH)2D3. A similar but less pronounced effect was observed for all other cancer cell lines. Furthermore, HL-60 that were transfected with VDR siRNA before compound treatment did not show inhibition of cell growth at the same concentrations (Fig.2F). Control siRNA transfected cells behaved similar to non-transfected cells (Fig.2D), thus VDR a crucial mediator for the antiproliferative effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 and the combination with PS121912.

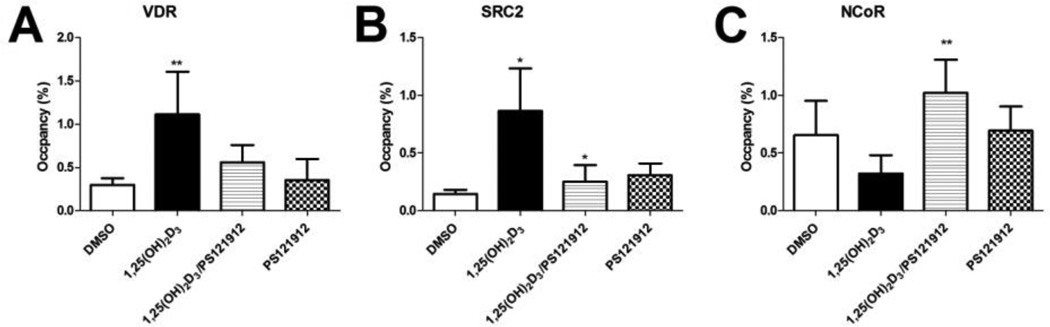

It was shown that PS121912 inhibit the interaction between VDR and coactivator SRC2 in cells using a two-hybrid assay.[23] In order to demonstrate the inhibition of DNA-bound VDR during transcription a chromatin immunoprecipitation assay (ChIP) was carried out using specific antibodies for coactivator SRC2 and corepressor NCoR. The results are depicted in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay (ChIP) in HL-60 cells at the CYP24A1 promoter. Cells were incubated with 20 nM 1,25(OH)2D3, 0.5 µM PS121912, or the combination thereof. A) IP using VDR antibody; B) IP using SRC2 antibody, and C) IP using NCoR antibody.

1,25(OH)2D3 induced the DNA occupancy of VDR at the CYP24A1 promoter site in addition to the recruitment of coactivator SRC2 (Fig.3 A and B)[31]. In respect to corepressor recruitment, 1,25(OH)2D3 reduced the interaction between VDR and NCoR (Fig.3 C). Importantly, the interaction between DNA-bound VDR and SRC2 was reduced in the presence of PS121912, whereas PS121912 promoted the interaction between VDR and NCoR. Finally, low concentrations of PS121912 by itself had no significant effect of the VDR-coregulator recruitment.

To determine the regulation of genes in the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3 and PS121912, we measured the mRNA levels of direct VDR target genes bearing an identified VDR response element in their promoter sequence such as TRPV6 [32], IGFBP3 [33], CYP24A1 [34], P21 [35], GADD45 [36]. The results for four different cancer cells (DU145, Caco2, SKOV3, and HL-60) are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Modulation of gene expression in the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3 and/or PS121912.

| Cell line | DU145a | Caco2a | SKOV3a | HL-60b | DU145c | Caco2c | SKOV3c | HL-60d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | 1,25(OH)2D3e | 1,25(OH)2D3/PS121912f | ||||||

| Gene | ||||||||

| TRPV6 | 1.39±0.1 | 1.69±0.35 | 1.14±0.32 | 0.79±0.23 | 0.51±0.03 | 1.02±0.14 | 1.21±0.35 | 1.38±0.41 |

| IGFBP3 | 2.49±0.4 | 2.06±0.31 | 0.79±0.03 | 0.71±0.29 | 1.37±0.1 | 1.86±0.51 | 0.74±0.08 | 1.03±0.35 |

| CYP24A1 | 11.8±1.8 | 74.3±10.4 | 118±36 | 9.52±2.1 | 8.0±0.6 | 36.1±5.4 | 13.5±13 | 5.41±1.6 |

| P21 | 3.31±0.57 | 0.67±0.09 | 1.19±0.27 | 1.48±0.32 | 1.38±0.04 | 0.67±0.05 | 1.60±0.39 | 1.72±0.41 |

| GADD45 | 0.67±0.16 | 0.92±0.16 | 1.11±0.25 | 1.75±0.28 | 1.44±0.30 | 1.11±0.21 | 1.26±0.41 | 1.98±0.26 |

Cells were treated with compounds for 18 hours followed by mRNA extraction and RT-qPCR. The fold induction was calculated in respect to control using the ΔΔCt method

100 nM 1,25(OH)2D3,

20 nM 1,25(OH)2D3,

100 nM 1,25(OH)2D3/2 µM PS121912,

20 nM 1,25(OH)2D3/500 nM PS121912,

significant higher and

significant higher and  significant lower in respect to vehicle;

significant lower in respect to vehicle;

significant higher and

significant higher and  significant lower in respect to 1,25(OH)2D3.

significant lower in respect to 1,25(OH)2D3.

In general, many of the genes were up-regulated by 1,25(OH)2D3, and this up-regulation was blocked with the co-treatment of 1,25(OH)2D3 and PS121912. For example, the mRNA level of TRVP6 , a calcium channel, increased in the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3 for prostate and colon cells, whereas treatment with 1,25(OH)2D3 and PS121912 blocked this increase. Similarly, higher mRNA levels of IGFBP3, a IGF binding protein, were observed for DU145 and Caco2 in the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3, which were reduced with the co-treatment of 1,25(OH)2D3 and PS121912. The gene product of CYP24A1, 24-hydroxylase, regulates the catabolism of 1,25(OH)2D3 and is upregulated in all cancer cells treated with 1,25(OH)2D3. Importantly, the combination of 1,25(OH)2D3 and PS121912 down-regulated CYP24A1 in all cell lines. The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor P21, involved in growth arrest, was up-regulated by 1,25(OH)2D3 in DU145 and HL-60, resulting in significant growth inhibition. For the co-treatment of 1,25(OH)2D3 and PS121912, P21 mRNA levels were elevated in DU145, SKOV3, and HL-60. GADD45, which is also affiliated with growth arrest, was increased for the sensitive HL-60 in the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3 and elevated for the co-treatment in DU145 and HL-60.

In addition, we determined the gene regulation in the presence of PS121912 without 1,25(OH)2D3. The results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Gene regulation in the presence of PS121912

| Cell line | DU145a | Caco2a | SKOV3a | HL-60b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | PS121912c | |||

| TRPV6 | 0.52±0.06 | 1.10±0.35 | 1.13±0.45 | 1.27±0.41 |

| IGFBP3 | 1.00±0.07 | 1.17±0.14 | 0.86±0.14 | 0.81±0.18 |

| CYP24A1 | 1.11±0.1 | 1.11±0.13 | 0.73±0.08 | 0.67±0.15 |

| P21 | 0.97±0.14 | 0.60±0.06 | 1.01±0.25 | 1.38±0.30 |

| GADD45 | 0.97±0.08 | 1.04±0.09 | 1.17±0.27 | 1.23±0.22 |

Cells were treated with compounds for 18 hours followed by mRNA extraction and RT-qPCR. The fold induction was calculated in respect to vehicle using the ΔΔCt method.

2 µM PS121912,

500 nM PS121912,

less than 0.75  lower.

lower.

Overall, we observed a minor change in gene regulation with 500 nM PS121912 reflected by the absence of antiproliferation. TRPV6 is down-regulated in DU145 and CYP24A1 is down-regulated in SKOV3 and HL-60 and P21 is down-regulated in Caco2 cells. In comparison with Table 1, PS121912 gene regulatory effects are highly dependent on the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3.

Furthermore, the expression levels of a large group of genes involved in cell cycle and proliferation were determined for HL-60 cells treated with 1,25(OH)2D3 in the presence and absence of PS121912.

Among the 43 gene investigated, 12 genes were significantly down-regulated, which include cyclins A, D1, and D2, cyclin-dependent kinase 6, and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors 2A. In general, the effect was more pronounced for the combination treatment than the sole 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment. In addition, transcription factors E2F-1 and E2F-4, glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta, histone deacetylase 6 and 9, and transforming growth factor beta 2 and 3 were down-regulated. In contrast, dual-specific phosphatase CDC25A and cyclin-dependent kinase 1A also known as P21 were up-regulated. An additional study with 20 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 and 3 µM PS121912 was carried out resulting in similar gene regulation (results not shown).

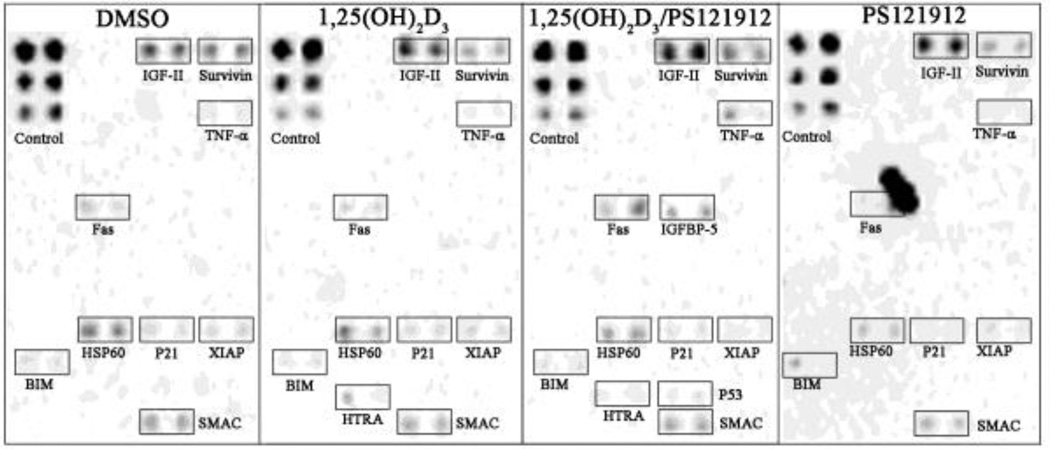

The expression of proteins associated with apoptosis were examined using an antibody array. HL-60 cells were treated with DMSO, 1,25(OH)2D3, or the combination of 1,25(OH)2D3 and PS121912 for 18 hours. Cell-lysates were added to the array, which contains 44 apoptosis pull-down antibodies spotted in duplicate. Biotinylated antibodies were used for detection, which in turn were visualized with fluorescently-labeled streptavidin. The results are depicted in Fig.4.

Fig. 4.

A human apoptosis antibody array was used to detect changes in protein levels. HL-60 cells were incubated with DMSO, 1,25(OH)2D3 (20 nM), 1,25(OH)2D3 (20 nM)/PS121912 (500 nM), or PS121912 (500 nM) for 18 hours.

Nine proteins could be detected in HL-60 cells treated with DMSO, with IGF-II and HSP60 being the most prominent pro-apoptotic proteins. The treatment with 1,25(OH)2D3 induced the expression of IGF-II but also reduced the protein levels of Survivin, an inhibitor of apoptosis. The pro-apoptotic serine protease HTRA was upregulated contributing to the reduced proliferation of HL-60 cells in the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3. The co-treatment of 1,25(OH)2D3 and PS121912 slightly elevated the IGF-II and Survivin levels, but it also significantly increased the levels of pro-apoptotic TNF-α and death receptor FAS. In addition, the levels of pro-apoptotic IGFBP5 were increased. The inhibitor of apoptosis XIAP was down-regulated in comparison to DMSO or 1,25(OH)2D3 treated HL-60 cells. For the sole treatment with PS121912 a reduced expression of HSP60 and Survivin was observed. In addition, the levels of pro-apoptotic BIM were elevated with PS121912.

In order to assess the potential utility of PS121912 in vivo we determined its metabolic stability. The results are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Metabolic in vitro clearance

| PS121912 | |

|---|---|

| Intrinsic Clearance (ml/min/kg)a | 2.04 |

| Metabolic Ratea | 0.102 |

| Half-Life (min)a | 179 |

| left at 1 hour (%)a | 77 |

| CYP3A4 Inhibition ( µM)b | 9.1 ± 2.0 |

| Polar Surface Area (Å)c | 37.05 |

| LogPc | 5.97 |

| Rotatablec | 6 |

| H-Bond Donorc | 2 |

| H-Bond Acceptorc | 2 |

PS121912 was treated with pooled human liver microsomes. Metabolism of PS121912 was quantified by LCMS using caffeine as internal standard.

Inhibition of CYP3A4 by PS121912 was determined with Vivid screening kit (Invitrogen) using fluorescence.

calculated using MOE (molecular operating environment).

The clearance of PS121912 is very good with a half-life of almost 3 hours. PS121912 inhibits the function of CYP3A4 at higher concentrations, which might contributes to its prolonged clearance. Overall, PS121912 is a predominately hydrophobic molecule with a small polar surface area and an elevated logP value.

Finally, we investigate the effect of higher PS121912 concentrations in HL-60 especially in respect to apoptosis as demonstrated in Fig1. Therefore, mRNA levels of caspase 3 and 7 were determined for HL-60 cells treated with 3 µM PS121912 (Fig5.).

Fig. 5.

Regulation of caspases and CYP3A4. A) caspase 3; B) capsase 7; C) CYP3A4. HL-60 cells were incubated with DMSO, 1,25(OH)2D3 (20 nM), PS121912 (3 µM) or a combination thereof for 18 hours and mRNA levels were determined by rt-PCR.

In the presence of 20 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 no change in caspase 3 and caspase 7 mRNA levels were observed. However, PS121912 induced the expression of both caspases at a concentration of 3 µM independently of the concentration of 1,25(OH)2D3. Furthermore, mRNA levels of CYP3A4 were not altered in the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3, PS121912, or a combination thereof.

Discussion

Although VDR is expressed in many cells, including cancer cells, there is a high tissue-selective action of VDR ligands with respect to gene regulation and cell proliferation. The leukemia cell line HL-60 was one of the very few cancer cell lines that are sensitive toward PS121912. Others included the monocytes CCRF-CEM and MOLT-4, the non-small cell lung cancer NCI-H522, and renal cancer cells UO-31, determined by the NIH developmental therapeutics program (see online resource). DU145, SKOV3, and Caco2 cells were investigated in this study because of their low and medium sensitivities towards PS121912. Importantly, apoptosis was observed in all cancer cells in the presence of micromolar concentrations of PS121912, supporting the fact that programmed cell death can be induced with appropriate concentrations of PS121912.

PS121912 is also able to modulate the transcription of a number of VDR target genes related to cell growth at sub-micromolar concentrations in the presence of 1,25-(OH)2D3. This effect is less pronounced in the absence of 1,25-(OH)2D3 thus liganded VDR is likely to mediate this response. Similar results were observed for proliferation studies that showed cell growth inhibition caused by 1,25-(OH)2D3, which was amplified in the presence of PS121912. The antiproliferation effect of 1,25-(OH)2D3 and the combination of 1,25-(OH)2D3/PS121912 was abolished in HL-60 cell treated with VDR siRNA, demonstrating the essential role of VDR to mediate antiproliferative effects of VDR modulators.

Recent microarray studies support the fact that the profile of genes regulated by 1,25-(OH)2D3 showed substantial variation among different cells.[37] Similar results were observed in this study, where transcription of VDR target genes, regulated by 1,25-(OH)2D3 or the co-treatment with PS121912, was different for cancer cells. In fact, CYP24A1 was the only gene that was up-regulated in all four cancer cells in the presence of 1,25-(OH)2D3. In HL-60 cells, 1,25-(OH)2D3 increased DNA binding of VDR and induced recruitment of coactivator SRC2 at the promoter site. In turn, 1,25-(OH)2D3 reduced the interaction of DNA-bound VDR and corepressor NCoR thus inhibiting repressed transcription. In concert with sub-micromolar concentration of PS121912, we observed the inhibition of coactivator binding and the recruitment of NCoR resulting in repressed expression of CYP24A1. CYP24A1 is elevated in many cancer patients and has been associated with poor disease prognosis.[38] Therefore, the down-regulation of CYP24A1 is an important anticancer action of PS121912 that occurs in the presence of 1,25-(OH)2D3.

Other VDR target genes such as P21 and GADD45 are up-regulated in HL-60 in the presence of 1,25-(OH)2D3 and in combination with PS121912 and are is most likely to mediate their antiproliferative effects. Both gene products have been reported to arrest cells in the G1/S or G2/M phase [39, 40]. In addition, 1,25-(OH)2D3 has been known to induce monocytic differentiation of HL-60 mediated by up-regulated P21 [41]. For both anti-proliferative treatments, detectable P21 protein levels were observed in HL-60 as well as increased levels pro-apoptotic serine protease HTRA. During growth arrest, elevated levels of p21 inhibit CDK4 phosphorylation of cyclin D1 [42]. Thus reduction in the expression levels of cyclin D1 , observed for the co-treatment of 1,25-(OH)2D3 and PS121912, is expected to amplify this apoptotic pathway leading to a pronounced cell cycle arrest.

Cyclin A1, which is found in many leukemia cell lines [43], is highly expressed during the S and G2/M phase and is affiliated with transcription factor E2F-1 and p21 [44]. All three genes are down-regulated in the presence of 1,25-(OH)2D3 and PS121912 thus leading to cell cycle arrest under these conditions. Among the cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK) only CDK6 is down-regulated, which in turn is controlled by cyclin D1-3 [45]. CDK6 is important for hematopietic functions and is essential for the sustaining proliferation [46]. Also HDAC 9 has hematopietic functions and is down-regulated 1,25-(OH)2D3 and PS121912 impairing the progression of the cell cycle. Transforming growth factors beta (TGF-beta) is an essential cytokines involved in growth and development [47]. In cancer cells however, TGF-beta 1 is a negative growth regulator, whereas the function of TGF-beta 2 and 3 are less understood. The down-regulation of TGF-beta 2 and 3 in the presence of 1,25-(OH)2D3 and PS121912 might be specific to promyelocytic cells mediating a distinct pathway of antiproliferation. Finally, GSK-3, which supports the progression of leukemia [48], is down-regulated by 1,25-(OH)2D3 and PS121912 making GSK-3 an important target for VDR modulators.

We can conclude that PS121912, especially at low concentrations, behaves like a VDR antagonist reversing transcriptional effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 when used as co-treatment. In addition, PS121912 as well as other VDR antagonists do not reverse the antiproliferative effect of 1,25-(OH)2D3 [49]. However at higher concentrations, PS121912 might interact with more biological targets especially those responsible for the activation of caspase 3/7. Especially the up-regulation of CASP3 and CASP7 , which has not been reported to be mediated by VDR, is unique to PS121912.

Finally, we determined the preclinical properties of PS121912 in order to investigate this compound in vivo. The analysis revealed that PS121912 is metabolically stable and can inhibit the metabolic enzyme CYP3A4 at higher concentrations. Thus, we believe that the bioavailability of PS121912 will be sufficient in order to determine its anticancer effects in vivo .

Supplementary Material

Table 3.

Regulation of genes involved in cell cycle.

| Gene | Description | 1,25D3a | 1,25D3b PS121912 |

Gene | Description | 1,25D3a | 1,25D3b PS121912 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GUSB | glucuronidase, beta | 0.99±0.08 | 0.92±0.1 | CDKN2C | cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2C | 1.16±0.33 | 0.86±0.19 |

| ATM | ataxia telangiectasia mut. | 1.23±0.11 | 0.87±0.30 | CDKN2D | cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2D | 1.17±0.44 | 0.81±0.19 |

| ATR | ataxia telangiectasia | 0.90±0.15 | 0.63±0.15 | E2F1 | E2F transcription factor 1 | 0.61±0.06 | 0.67±0.19 |

| CCNA1 | cyclin A1 | 0.37±0.01 | 0.47±0.24 | E2F2 | E2F transcription factor 2 | 1.41±0.35 | 1.13±0.29 |

| CCNA2 | cyclin A2 | 1.05±0.01 | 0.78±0.07 | E2F3 | E2F transcription factor 3 | 0.94±0.25 | 0.70±0.22 |

| CCNB1 | cyclin B1 | 1.07±0.08 | 0.73±0.11 | E2F4 | E2F transcription factor 4, | 0.69±0.13 | 0.52±0.17 |

| CCNB2 | cyclin B2 | 1.01±0.23 | 0.73±0.06 | GSK3B | glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta | 0.90±0.42 | 0.57±0.12 |

| CCND1 | cyclin D1 | 0.20±0.01 | 0.18±0.08 | HDAC1 | histone deacetylase 1 | 0.80±0.14 | 0.73±0.07 |

| CCND2 | cyclin D2 | 0.44±0.03 | 0.41±0.22 | HDAC2 | histone deacetylase 2 | 0.79±0.03 | 0.74±0.09 |

| CCND3 | cyclin D3 | 1.13±0.04 | 0.97±0.18 | HDAC3 | histone deacetylase 3 | 0.76±0.13 | 0.73±0.23 |

| CCNE1 | cyclin E1 | 0.74±0.02 | 0.78±0.08 | HDAC4 | histone deacetylase 4 | 0.82±0.12 | 0.73±0.07 |

| CCNE2 | cyclin E2 | 0.84±0.05 | 0.70±0.07 | HDAC5 | histone deacetylase 5 | 0.90±0.08 | 0.77±0.12 |

| CCNH | cyclin H | 0.91±0.04 | 0.82±0.15 | HDAC6 | histone deacetylase 6 | 0.72±0.17 | 0.55±0.05 |

| CDC2 | cell division cycle 2, | 0.81±0.05 | 0.62±0.07 | HDAC7 | histone deacetylase 7 | 0.85±0.32 | 0.64±0.14 |

| CDC25A | cell division cycle 25A | 1.28±0.14 | 1.67±0.37 | HDAC9 | histone deacetylase 9 | 0.53±0.02 | 0.41±0.16 |

| CDK2 | cyclin-dependent kinase 2 | 0.81±0.11 | 0.61±0.03 | PPP2CA | protein phosphatase 2 | 0.86±0.01 | 0.80±0.15 |

| CDK4 | cyclin-dependent kinase 4 | 0.93±0.21 | 0.70±0.05 | RAF1 | v-raf-1 leukemia viral gene | 0.86±0.04 | 0.74±0.09 |

| CDK6 | cyclin-dependent kinase 6 | 0.61±0.12 | 0.39±0.09 | RB1 | retinoblastoma 1 | 0.97±0.03 | 0.77±0.15 |

| CDK7 | cyclin-dependent kinase 7 | 1.11±0.04 | 0.62±0.07 | TGFB1 | transforming growth factor, beta 1 | 0.91±0.01 | 0.74±0.12 |

| CDKN1A | cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A | 1.59±0.08 | 2.15±0.44 | TGFB2 | transforming growth factor, beta 2 | 0.29±0.08 | 0.36±0.11 |

| CDKN1B | cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B | 0.84±0.01 | 0.69±0.21 | TGFB3 | transforming growth factor, beta 3 | 0.65±0.25 | 0.48±0.12 |

| CDKN2A | cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A | 0.66±0.09 | 0.57±0.10 | ± |

HL-60 were treated with compounds for 18 hours followed by mRNA extraction, RT qPCR. The fold induction was calculated in respect to vehicle using the ΔΔCt method.

20 nM 1,25(OH)2D3.

20 nM 1,25(OH) 2D30.5 µM PS121912.  > 1.25,

> 1.25,  < 0.6.

< 0.6.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee [LAA], the UWM Research Growth Initiative (RGI grant 2012) [LAA], the NIH R03DA031090 [LAA], the UWM Research Foundation (Catalyst grant), the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation [LAA], the Richard and Ethel Herzfeld Foundation [LAA], RO1 AR050023 [DDB], and Swim Across America and Women and Infants’ Hospital of Rode Island [RKS].

References

- 1.Eisman JA, Martin TJ, MacIntyre I, Moseley JM. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin-D-receptor in breast cancer cells. Lancet. 1979;2:1335–1336. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)92816-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colston K, Colston MJ, Feldman D. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and malignant melanoma: the presence of receptors and inhibition of cell growth in culture. Endocrinology. 1981;108:1083–1086. doi: 10.1210/endo-108-3-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Savli H, Aalto Y, Nagy B, Knuutila S, Pakkala S. Gene expression analysis of 1,25(OH)2D3-dependent differentiation of HL-60 cells: a cDNA array study. Br J Haematol. 2002;118:1065–1070. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swami S, Raghavachari N, Muller UR, Bao YP, Feldman D. Vitamin D growth inhibition of breast cancer cells: gene expression patterns assessed by cDNA microarray. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;80:49–62. doi: 10.1023/A:1024487118457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krishnan AV, Shinghal R, Raghavachari N, Brooks JD, Peehl DM, Feldman D. Analysis of vitamin D-regulated gene expression in LNCaP human prostate cancer cells using cDNA microarrays. Prostate. 2004;59:243–251. doi: 10.1002/pros.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wood RJ, Tchack L, Angelo G, Pratt RE, Sonna LA. DNA microarray analysis of vitamin D-induced gene expression in a human colon carcinoma cell line. Physiol Genomics. 2004;17:122–129. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00002.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang X, Li P, Bao J, Nicosia SV, Wang H, Enkemann SA, Bai W. Suppression of death receptor - mediated apoptosis by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 revealed by microarray analysis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:35458–35468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506648200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akutsu N, Lin R, Bastien Y, Bestawros A, Enepekides DJ, Black MJ, White JH. Regulation of gene Expression by 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and Its analog EB1089 under growth-inhibitory conditions in squamous carcinoma Cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:1127–1139. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.7.0655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brumbaugh PF, Haussler MR. 1 Alpha,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol receptors in intestine. II. Temperature-dependent transfer of the hormone to chromatin via a specific cytosol receptor. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:1258–1262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mellon WS, DeLuca HF. An equilibrium and kinetic study of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 binding to chicken intestinal cytosol employing high specific activity 1,25-dehydroxy[3H-26, 27] vitamin D3. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1979;197:90–95. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(79)90223-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gross C, Stamey T, Hancock S, Feldman D. Treatment of early recurrent prostate cancer with 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (calcitriol) J Urol. 1998;159:2035–2039. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)63236-1. discussion 2039–2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beer TM, Myrthue A. Calcitriol in cancer treatment: from the lab to the clinic. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:373–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gulliford T, English J, Colston KW, Menday P, Moller S, Coombes RC. A phase I study of the vitamin D analogue EB 1089 in patients with advanced breast and colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 1998;78:6–13. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jain RK, Trump DL, Egorin MJ, Fernandez M, Johnson CS, Ramanathan RK. A phase I study of the vitamin D3 analogue ILX23-7553 administered orally to patients with advanced solid tumors. Invest New Drugs. 2011;29:1420–1425. doi: 10.1007/s10637-010-9492-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKenna NJ, Lanz RB, O'Malley BW. Nuclear receptor coregulators: cellular and molecular biology. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:321–344. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tagami T, Lutz WH, Kumar R, Jameson JL. The interaction of the vitamin D receptor with nuclear receptor corepressors and coactivators. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;253:358–363. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masuyama H, Brownfield CM, St-Arnaud R, MacDonald PN. Evidence for ligand-dependent intramolecular folding of the AF-2 domain in vitamin D receptor-activated transcription and coactivator interaction. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:1507–1517. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.10.9990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong H, Kohli K, Garabedian MJ, Stallcup MR. GRIP1, a transcriptional coactivator for the AF-2 transactivation domain of steroid, thyroid, retinoid, and vitamin D receptors. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2735–2744. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li H, Gomes PJ, Chen JD. RAC3, a steroid/nuclear receptor-associated coactivator that is related to SRC-1 and TIF2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:8479–8484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nandhikonda P, Lynt WZ, McCallum MM, Ara T, Baranowski AM, Yuan NY, Pearson D, Bikle DD, Guy RK, Arnold LA. Discovery of the first irreversible small molecule inhibitors of the interaction between the vitamin D receptor and coactivators. J Med Chem. 2012;55:4640–4651. doi: 10.1021/jm300460c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mita Y, Dodo K, Noguchi-Yachide T, Miyachi H, Makishima M, Hashimoto Y, Ishikawa M. LXXLL peptide mimetics as inhibitors of the interaction of vitamin D receptor with coactivators. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:1712–1717. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.01.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mita Y, Dodo K, Noguchi-Yachide T, Hashimoto Y, Ishikawa M. Structure-activity relationship of benzodiazepine derivatives as LXXLL peptide mimetics that inhibit the interaction of vitamin D receptor with coactivators. Bioorg Med Chem. 2013;21:993–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sidhu PS, Nassif N, McCallum MM, Teske K, Feleke B, Yuan NY, Nandhikonda P, Cook JM, Singh RK, Bikle DD, Arnold LA. Development of Novel Vitamin D Receptor–Coactivator Inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2014 doi: 10.1021/ml400462j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miura D, Manabe K, Ozono K, Saito M, Gao Q, Norman AW, Ishizuka S. Antagonistic action of novel 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-26, 23-lactone analogs on differentiation of human leukemia cells (HL-60) induced by 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:16392–16399. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.23.16392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bury Y, Steinmeyer A, Carlberg C. Structure activity relationship of carboxylic ester antagonists of the vitamin D(3) receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:1067–1074. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.5.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Igarashi M, Yoshimoto N, Yamamoto K, Shimizu M, Ishizawa M, Makishima M, DeLuca HF, Yamada S. Identification of a highly potent vitamin D receptor antagonist: (25S)-26-adamantyl-25-hydroxy-2-methylene-22,23-didehydro-19,27-dinor-20-epi-vita min D3 (ADMI3) Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;460:240–253. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inaba Y, Yoshimoto N, Sakamaki Y, Nakabayashi M, Ikura T, Tamamura H, Ito N, Shimizu M, Yamamoto K. A new class of vitamin D analogues that induce structural rearrangement of the ligand-binding pocket of the receptor. J Med Chem. 2009;52:1438–1449. doi: 10.1021/jm8014348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teske K, Nandhikonda P, Bogart JW, Feleke B, Sidhu PS, Yuan NY, Prestron J, Goy R, Singh RK, Bikle DD, Cook JM, Arnold LA. Identification of VDR antagonists among nuclear receptor ligands using virtual screening. Nuclear Receptor Research. 2014;1:1–8. doi: 10.11131/2014/101076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nandhikonda P, Yasgar A, Baranowski AM, Sidhu PS, McCallum MM, Pawlak AJ, Teske K, Feleke B, Yuan NY, Kevin C, Bikle DD, Ayers SD, Webb P, Rai G, Simeonov A, Jadhav A, Maloney D, Arnold LA. Peroxisome Proliferation-Activated Receptor delta Agonist GW0742 Interacts Weakly with Multiple Nuclear Receptors, Including the Vitamin D Receptor. Biochemistry-Us. 2013;52:4193–4203. doi: 10.1021/bi400321p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thornberry NA, Lazebnik Y. Caspases: enemies within. Science. 1998;281:1312–1316. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meyer MB, Goetsch PD, Pike JW. A downstream intergenic cluster of regulatory enhancers contributes to the induction of CYP24A1 expression by 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:15599–15610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.119958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meyer MB, Watanuki M, Kim S, Shevde NK, Pike JW. The human transient receptor potential vanilloid type 6 distal promoter contains multiple vitamin D receptor binding sites that mediate activation by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in intestinal cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:1447–1461. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peng L, Malloy PJ, Feldman D. Identification of a functional vitamin D response element in the human insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 promoter. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:1109–1119. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zou A, Elgort MG, Allegretto EA. Retinoid X receptor (RXR) ligands activate the human 25-hydroxyvitamin D3-24-hydroxylase promoter via RXR heterodimer binding to two vitamin D-responsive elements and elicit additive effects with 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19027–19034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.19027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu M, Lee MH, Cohen M, Bommakanti M, Freedman LP. Transcriptional activation of the Cdk inhibitor p21 by vitamin D3 leads to the induced differentiation of the myelomonocytic cell line U937. Genes Dev. 1996;10:142–153. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang F, Li P, Fornace AJ, Jr, Nicosia SV, Bai W. G2/M arrest by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in ovarian cancer cells mediated through the induction of GADD45 via an exonic enhancer. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:48030–48040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308430200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kriebitzsch C, Verlinden L, Eelen G, Tan BK, Van Camp M, Bouillon R, Verstuyf A. The impact of 1,25(OH)2D3 and its structural analogs on gene expression in cancer cells--a microarray approach. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:3471–3483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anderson MG, Nakane M, Ruan X, Kroeger PE, Wu-Wong JR. Expression of VDR and CYP24A1 mRNA in human tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;57:234–240. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chung HK, Yi YW, Jung NC, Kim D, Suh JM, Kim H, Park KC, Song JH, Kim DW, Hwang ES, Yoon SH, Bae YS, Kim JM, Bae I, Shong M. CR6-interacting factor 1 interacts with Gadd45 family proteins and modulates the cell cycle. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28079–28088. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212835200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kearsey JM, Coates PJ, Prescott AR, Warbrick E, Hall PA. Gadd45 is a nuclear cell cycle regulated protein which interacts with p21Cip1. Oncogene. 1995;11:1675–1683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang H, Lin J, Su ZZ, Collart FR, Huberman E, Fisher PB. Induction of differentiation in human promyelocytic HL-60 leukemia cells activates p21, WAF1/CIP1, expression in the absence of p53. Oncogene. 1994;9:3397–3406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.LaBaer J, Garrett MD, Stevenson LF, Slingerland JM, Sandhu C, Chou HS, Fattaey A, Harlow E. New functional activities for the p21 family of CDK inhibitors. Genes Dev. 1997;11:847–862. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.7.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang R, Nakamaki T, Lubbert M, Said J, Sakashita A, Freyaldenhoven BS, Spira S, Huynh V, Muller C, Koeffler HP. Cyclin A1 expression in leukemia and normal hematopoietic cells. Blood. 1999;93:2067–2074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang R, Muller C, Huynh V, Fung YK, Yee AS, Koeffler HP. Functions of cyclin A1 in the cell cycle and its interactions with transcription factor E2F-1 and the Rb family of proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2400–2407. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meyerson M, Harlow E. Identification of G1 kinase activity for cdk6, a novel cyclin D partner. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2077–2086. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kozar K, Sicinski P. Cell cycle progression without cyclin D-CDK4 and cyclin D-CDK6 complexes. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:388–391. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.3.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Munger JS, Harpel JG, Gleizes PE, Mazzieri R, Nunes I, Rifkin DB. Latent transforming growth factor-beta: structural features and mechanisms of activation. Kidney international. 1997;51:1376–1382. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Z, Smith KS, Murphy M, Piloto O, Somervaille TC, Cleary ML. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 in MLL leukaemia maintenance and targeted therapy. Nature. 2008;455:1205–1209. doi: 10.1038/nature07284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Antony R, Sheng X, Ehsanipour EA, Ng E, Pramanik R, Klemm L, Ichihara B, Mittelman SD. Vitamin D protects acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells from dexamethasone. Leuk Res. 2012;36:591–593. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.