Abstract

Inhibitors of serine peptidases (ISPs) expressed by Leishmania major enhance intracellular parasitism in macrophages by targeting neutrophil elastase (NE), a serine protease that couples phagocytosis to the prooxidative TLR4/PKR pathway. Here we investigated the functional interplay between ISP-expressing L. major and the kallikrein-kinin system (KKS). Enzymatic assays showed that NE inhibitor or recombinant ISP-2 inhibited KKS activation in human plasma activated by dextran sulfate. Intravital microscopy in the hamster cheek pouch showed that topically applied L. major promastigotes (WT and Δisp2/3 mutants) potently induced plasma leakage through the activation of bradykinin B2 receptors (B2R). Next, using mAbs against kininogen domains, we showed that these BK-precursor proteins are sequestered by L. major promastigotes, being expressed at higher % in the Δisp2/3 mutant population. Strikingly, analysis of the role of kinin pathway in the phagocytic uptake of L. major revealed that antagonists of B2R or B1R reversed the upregulated uptake of Δisp2/3 mutants without inhibiting macrophage internalization of WT L. major. Collectively, our results suggest that L. major ISP-2 fine-tunes macrophage phagocytosis by inhibiting the pericellular release of proinflammatory kinins from surface bound kininogens. Ongoing studies should clarify whether L. major ISP-2 subverts TLR4/PKR-dependent prooxidative responses of macrophages by preventing activation of G-protein coupled B2R/B1R.

1. Introduction

Integrated by 3 serine proteases, factor XII (FXII), factor XI (FXI), and plasma prekallikrein (PK) and by one nonenzymatic cofactor, high molecular weight kininogen (HK), the kallikrein-kinin system (KKS), also referred to as the plasma contact pathway of coagulation, is assembled and activated when the blood comes in contact with negatively charged polymers of endogenous origin or microbial surfaces [1, 2]. Upon binding to these negatively charged structures, the zymogen FXII undergoes a conformational change that endows the unstable proenzyme with limited enzymatic activity. Activated FXII (FXIIa) then cleaves prekallikrein (complexed to the cofactor HK), generating PKa. Reciprocal cleavage reactions between FXIIa and PKa amplify the proteolytic cascade, leading to downstream (i) generation of fibrin via the FXIIa/FXIa-dependent procoagulative pathway, (ii) release of the internal bradykinin (BK) moiety of HK by PKa. Once liberated, the short-lived BK induces vasodilation and increases microvascular permeability through the activation of bradykinin B2 receptors (B2R) expressed in the endothelium lining [1]. In addition, the multifunctional PKa generates plasmin, an effector of fibrinolysis, and cleaves native C3 of the complement system C3 [3, 4].

Although HK is classically regarded as the parental precursor of proinflammatory kinins, the cleaved form of HK (HKa), a disulfide linked two-chain structure, has additional biological functions. For example, it has been reported that HKa reduces neutrophil adhesive functions upon binding to β2-integrin Mac-1 (CR3, CD11b/CD18, αMβ2) [1, 5]. More recently, Yang et al. [6] appointed HK/HKa as the plasma-borne opsonins that drive efferocytosis of apoptotic cells via plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR)/RAC1-pathway. After binding to phosphatidyl serine (PS) exposed by apoptotic neutrophils, the surface-bound HK binds to uPAR before switching off proinflammatory responses of macrophages [6]. In contrast to this novel immunoregulatory function, HK (and low molecular weight kininogen, LK) are traditionally viewed as precursors of proinflammatory kinins. Once leaked into extravascular tissues, the plasma-borne HK/LK undergo proteolytic cleavage by tissue kallikrein, releasing the B2R agonist lysyl-BK (LBK) in inflammatory exudates [1]. It is noteworthy that oxidized forms of kininogens may release bioactive kinins as result of cooperation between neutrophil elastase (NE) and mast cell tryptase [7, 8]. Acting as paracrine hormones, the short-lived kinins (BK or LBK) swiftly activate G-protein coupled bradykinin B2 receptors (B2R), a subtype of receptor constitutively expressed by endothelial cells, nociceptive neurons, macrophages, and DCs [1, 9–11]. The long-range signaling activity of intact kinins is controlled by kinin-degrading metallopeptidases, such as the angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE/kininase II) [1]. In addition, the liberated kinin peptides are metabolized by kininase I (carboxypeptidase N or M); removal of the C-terminal Arg residue generates des-Arg-kinins, the high-affinity ligands of B1R, a GPCR subtype whose expression is strongly upregulated in injured/inflamed tissues [12].

During the last decade, research conducted in our laboratory showed that kinins proteolytically released in peripheral sites of T. cruzi or Leishmania chagasi infection reversibly couple inflammation to antiparasite immunity [13–17]. Another interesting twist came from studies showing that activation of the contact system/KKS promotes bacterial entrapment within fibrin meshes, thus providing a physical barrier against the systemic spread of microbial pathogens [18]. To this date, however, it is unclear whether the contact pathway modulates immunity at early stages of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Intravital microscopy studies conducted in the mouse ear model of L. major infection [19–21] have shown that infiltrating neutrophils engulf the promastigotes before expressing the apoptotic markers required for efferocytosis by dermal DCs. After internalizing the parasitized/apoptotic neutrophils, the dermal DCs are no longer capable of steering protective TH1-responses in the draining lymph node [19–21]. Although efferocytosis has strong impact on DC function and TH development in L. major infection, independent studies showed that macrophage clearance of apoptotic neutrophils may either induce pro- or anti-inflammatory responses in NE-dependent manner, the intracellular fate of the parasite being influenced by the host genetic background [22, 23].

In natural infection by blood-feeding arthropods, insect proboscis inevitably causes bleeding, which then causes the mixing of plasma and sandfly saliva substances with parasites deposited in the injured dermis [24]. Interestingly, Phlebotomy duboscq, a vector of Leishmania species, contains high levels of a salivary protein (PdSP15) that inhibits the contact pathway [25] by binding to negatively charged polymers of endogenous origin—such as platelet-derived polyphosphates [2, 18, 26]. Considering that activation of the procoagulative contact system induces microvascular leakage through PKa-mediated release of BK, it is conceivable that sandfly-transmitted Leishmania promastigotes have evolved the means to subvert the innate effector function of the kinin pathway at early stages of infection.

The current study was motivated by the recent discovery that Leishmania has three genes encoding ecotin-like inhibitors of serine peptidases (ISPs) [27]. Previous studies with the archetype of the family Escherichia coli ecotin [28] showed that this inhibitor targets neutrophil elastase (NE) [29]—a member of the trypsin-fold serine peptidases of clan PA/family S1A. After noting that the Leishmania genome [30] lacks these endogenous serine peptidase targets, Eschenlauer et al. [27] predicted that L. major ISPs might target S1A-family serine peptidases expressed by cells of the innate immune system, such as NE, tryptase, and cathepsin G [30]. In a series of elegant studies, Eschenlauer et al. [27] and Faria et al. [31, 32] addressed this issue using L. major lines lacking ISP2 and ISP3 (Δisp2/3). After studying the outcome of interactions between L. major promastigotes and elicited macrophages, these authors found that these phagocytes internalized the Δisp2/3 promastigotes far more efficiently than ISP-expressing wild-type (WT) parasites [27, 31] and linked the upregulated CR3-dependent phagocytosis of the Δisp2/3 L. major mutants to NE-dependent activation of innate immunity via the TLR4/PKR/TNF-α/IFN-β, a prooxidative pathway that limits intracellular parasite survival [31, 32]. Notably, the phenotype of Δisp2/3 promastigotes was reversed by supplementing the macrophage cultures with purified (recombinant) ISP-2 or with the synthetic NE inhibitor (MeOSuc-AAPV-CMK), at the onset of infection [31]. Based on these collective findings, these authors suggested that ISP-2 expressing L. major promastigotes might downmodulate phagocytosis and limit microbicidal responses of macrophages by preventing NE-dependent activation of TLR4 [31, 32]. More recently, we have documented that macrophages internalize and limit intracellular T. cruzi growth in resident macrophages through activation pathways forged by the cross-talk between bradykinin B2 receptors and C5a receptors [33]. Intrigued by the similarities that exist between the phenotype of the L. major Δisp2/3 mutant and L. chagasi promastigotes [15] and T. cruzi trypomastigotes (Dm28 strain) [33, 34], in the current work we interrogated whether ISP-expressing L. major and the ISP-2 Δisp2/3 mutants differ in their ability to activate the KKS in vivo and in vitro. Using intravital microscopy, we first showed that L. major promastigotes topically applied to the hamster cheek pouch potently activate the KKS extravascularly, irrespective of presence/absence of ISP. In the second part of this study, we present evidence indicating that ISP-expressing L. major may subvert innate immunity by targeting kinin-releasing serine proteases (S1A family) exposed at the cell-surface of macrophages.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Parasites

L. major Promastigotes of Friedlin (MHOM/JL/80/Friedlin) were grown in modified Eagle's medium (HOMEM, Sigma) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco) at 25°C, as previously described [31, 32]. Suspensions of promastigotes were washed twice with PBS before being used either in vitro or in vivo. Leishmania major deficient in ISP2 and ISP3 (Δisp2/3) were generated as previously described by Eschenlauer et al. [27]. The following antibiotics were used at the indicated concentration for the selection of transfectants: 50 mg/mL hygromycin B (Roche), 25 mg/mL G418 (Invitrogen), 10 mg/mL phleomycin (InvivoGen), and 50 mg/mL puromycin dihydrochloride (Calbiochem).

2.2. Intravital Digital Microscopy

Syrian hamsters, 3-month-old males, were maintained and anesthetized according to regulations given by the local ethical committee (IBCCF, protocol-014, 23/02/2008). Altogether 65 hamsters (114 ± 18 g) (Anilab, São Paulo, Brazil) were used. Anesthesia was induced by intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital 3% that was supplemented with i.v. α-chloralose (2.5% W/V, solution in saline) through a femoral vein catheter. A tracheal cannula (PE 190) was inserted to facilitate spontaneous breathing and the body temperature was maintained at 37°C by a heating pad monitored with a rectal thermistor. The hamster cheek pouch (HCP) was prepared and used for intravital microscopy as previously reported [34, 35]. The microcirculation of the HCP was observed using an Axioskop 40 microscope, objective 4x, and oculars 10x equipped with a LED light source Colibri (Carl Zeiss, Germany) and appropriate filters (490/520 nm and 540/580 nm, rhodamine) for observations of fluorescence in epiluminescence. A digital camera, AxioCam HRc, and a computer with the AxioVision 4.4 software program (Carl Zeiss, Germany) were used for image analysis of arteriolar diameter and total fluorescence in a representative rectangular area (5 mm2) of the prepared HCP. Fluorescence was recorded for 30 min prior to experimental interventions to secure normal blood flow and unaltered vascular permeability and the fluorescence measured at 30 min after FITC-dextran (FITC-dextran 150 kDa, 100 mg/kg bodyweight, TdB Consultancy, Uppsala, Sweden) injection was adjusted to 2000 fluorescent units (RFU = Relative Fluorescent Units) for statistical reasons. Leukocytes were labeled in vivo by injecting rhodamine 100 μg/kg b.w i.v. (10 min prior to experimental interventions), reinforced by injection of the same tracer at 10 μg/kg b.w. every 10 min until 60 min. The recorded fluorescence at 10 min after rhodamine injection in each experiment was adjusted to 3000 fluorescent units (RFU) for statistical reasons. Two images of exactly the same area were recorded at every 5 min interval during the entire experiment. One was used to measure plasma leakage and arteriolar diameter (490/520 nm) and the other to measure total fluorescence of rhodamine-labeled leukocytes in circulation, rolling, adherence, and migration (540/580 nm) in the observed area (5 mm2) here defined as leukocyte accumulation. Exposure time was limited to 15 s for each captured image in order to avoid phototoxicity. Following 30 min control period after FITC-dextran injection HCPs were topically exposed to WT L. major promastigotes or Δisp2/3 (7.5 × 106/500 μL) during interruption of the superfusion for 10 min. Cromoglycate was injected i.p. (40 mg/kg b.w.) at time of pentobarbital anesthesia and dextran sulfate 500 kDa (TdB Consultancy, Uppsala, Sweden) was injected i.v. (2 mg/kg) prior to parasite application. HOE-140 tested at 0.5 μM and the histamine receptor H1 mepyramine (10 μM) were applied locally via a syringe pump into the superfusion during 10 min prior to application of promastigotes.

2.3. Isolation of Peritoneal Macrophages and Invasion Assays

C57BL/6 mice received an intraperitoneal injection of 2 mL of 3% thioglycolate and macrophages were harvested from peritoneal lavage 3 days later. Macrophages were plated on 13 mm coverslips in 24-well plate and after 20 h of incubation at 37°C in complete medium (RPMI + 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin) the nonadherent cells were removed by washing the monolayer of cells with PBS. Invasion assays were performed by adding stationary phase promastigotes to the monolayers at a ratio of 5 : 1 (parasite/macrophage) in medium containing 1 mg/mL albumin from bovine serum (BSA, Sigma). The interaction was performed during 3 h in a humidified chamber containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. When indicated, the culture medium was supplemented with 100 nM of B2R antagonist (HOE-140, Sigma) or 1 μM of B1R antagonist des-Arg9-[Leu8]-BK (DAL8-BK; Sigma), 5 minutes before addition of parasites. After interaction, extracellular promastigotes were removed by washing the monolayers twice with PBS, which were then fixed with Bouin overnight and stained with Giemsa (Merck). The number of intracellular amastigotes was determined by counting at least 100 cells per replicate under the light microscope. All assays were done in triplicates and results were expressed as mean values ± SD.

2.4. Parasite Surface Staining

Promastigotes were preincubated with PBS-1% BSA for 1 hour to avoid unspecific binding and then incubated for 1 h with monoclonal antibody MBK3 (IgG1—1 : 50) or HKH4 (IgG2a—1 : 50), kindly provided by Dr. W. Müller-Esterl from Frankfurt University. MBK3 recognizes the BK epitope in domain D4 of human and bovine H-/L-kininogens whereas HKH4 binds to the D1 domain [36]. Isotype-matched monoclonal antibodies were used as negative controls. Parasites were washed three times with PBS-1% BSA and incubated with secondary fluorescent antibody (FITC—1 : 50) for 30 min at 4°C, protected from light. After washing, the samples were acquired by flow cytometry (FACSCan; BD Biosciences), and data analyses were done with Summit software (Dako Colorado, Inc). Assays were done in duplicates and results are representative of two independent experiments.

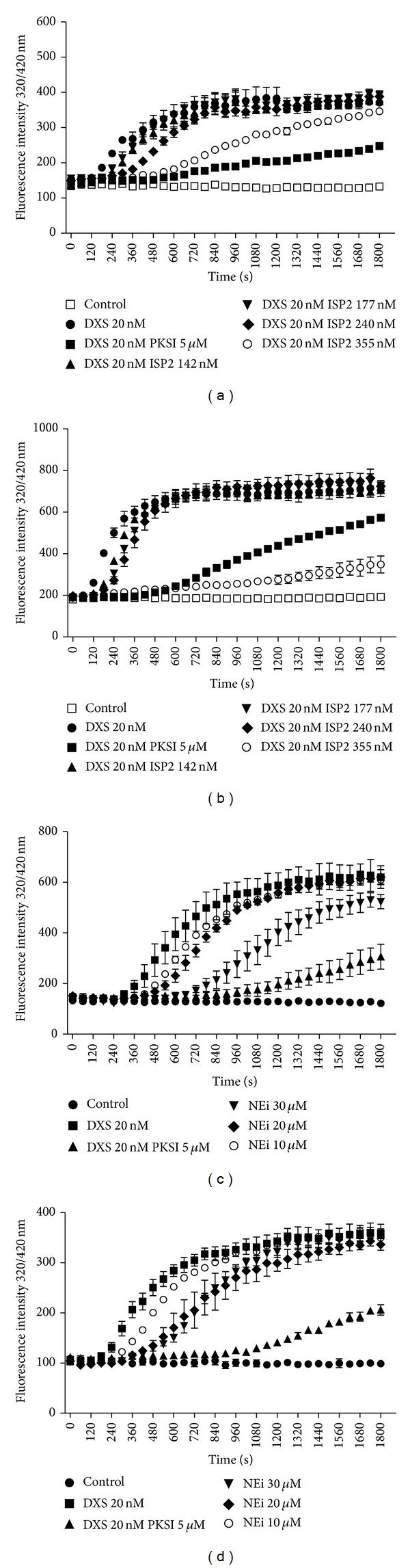

2.5. Contact Phase Activation of Human Plasma

The activation of FXII/PK in human citrated (platelet free) plasma treated (or not) with dextran sulfate (DXS; 500 kDa, TdB Consultancy) was monitored by spectrofluorimetry as previously described [37], using internally quenched fluorescent substrates whose sequences correspond to the C-terminal (Abz-GFSPFRSVTVQ-EDDnp) or N-terminal flanking region (Abz-MTEMARRPQ-EDDnp m) of BK of mouse kininogen. The hydrolysis of the cleaved substrate Abz-peptidyl-EDDnp (Abz = o-aminobenzoyl and EDDnp = ethylenediamine 2,4-dinitrophenyl) was monitored by measuring the fluorescence at λ ex. = 320 nm and λ em. = 420 nm in a Spectramax M5 fluorescence spectrophotometer. The reaction was carried out in PBS, pH 7.4, using citrated human plasma 1 : 20, 4 μM of the Abz-peptidyl-EDDnp substrate and 20 nM of the contact system activator DXS (500 kDa). As internal controls, the plasma was pretreated with the synthetic PKa inhibitor (PKSI-527—5 μM) [38]. Assays with recombinant ISP-2 (kindly supplied by A. P. C. A. Lima) were performed at final concentrations of 142, 177, 240, and 355 nM; the neutrophil elastase (NE) inhibitor MeOSuc-AAPV-CMK (Calbiochem) was tested at 10, 20, and 30 μM. PKSI or recombinant ISP2 and MeOSuc-AAPV-CMK were preincubated with human plasma for 15 min, at 37°C, prior to the addition of DXS and the substrate. Plasma was prepared by centrifugation of blood samples at 2500 g for 20 min at 4°C. After centrifugation, plasma samples were filtered using a 0.2 μm membrane.

2.6. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were done using PRISM 5.0 (GraphPad Software). Comparisons of the means of the different groups were done by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). When the mean values of the groups showed a significant difference, pairwise comparison was performed with the Tukey test. A P value of 0.05 or less was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. For intravital experiments, we used ANOVA or pairwise t-test, when appropriate.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of the Dynamics of Inflammation in HCP Topically Sensitized with L. major Promastigotes

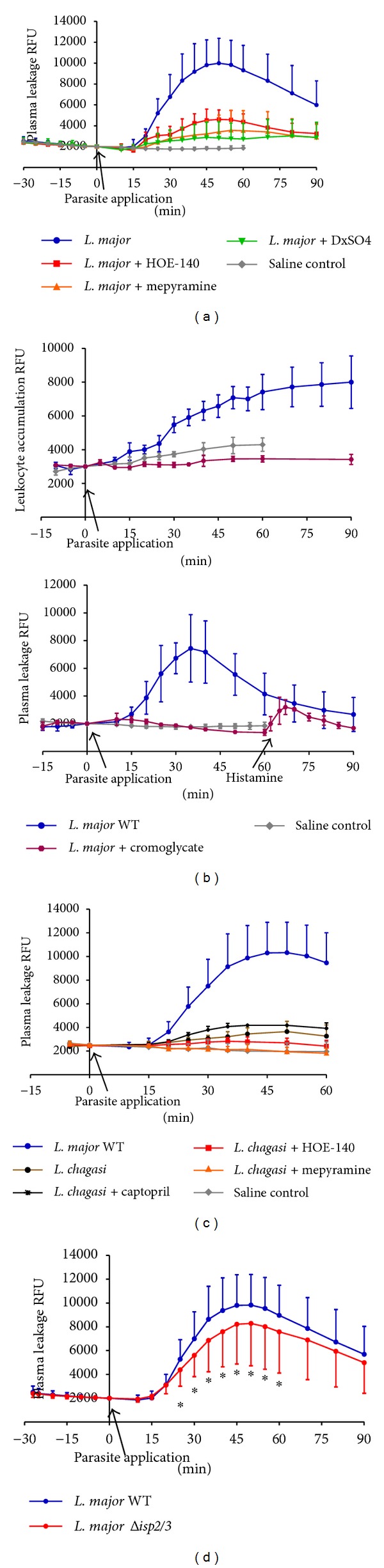

Intravital microscopy in HCP has provided a wealth of information about the interplay between the KKS and the topically applied pathogens because this method dispenses the use of needles, thus ruling out the influence of bleeding and collateral activation of the contact system in the analysis of microcirculatory parameters. As a starting point in this work, we asked whether the proinflammatory responses evoked by ISP-expressing L. major promastigotes or ISP-deficient parasites were comparable. Our results (Figures 1–3) revealed that L. major (WT) promastigotes induced a very robust and reversible microvascular leakage that was detectable at 20 min and reached its maximal value 45 min after pathogen application (Figures 1(a)–1(c)). In 4 out of 15 experiments we measured leukocyte accumulation in and around postcapillary venules and noted that these circulating cells were promptly mobilized locally, the response being detectable up to 90 min after pathogen application (Figure 1(b)). The temporal course and dynamics of the plasma leakage response evoked by WT promastigotes were quite different from the classical responses elicited by BK, histamine, or leukotrienes, all of which cause a maximal increase within 10 min and reversed to steady-state conditions within 30 min [39, 40]. Intriguingly, we found that the leakage responses evoked by L. major (WT) promastigotes were generally more robust than those induced by the same inoculum of L. donovani promastigotes (Figure 1(c)) [16] or T. cruzi (tissue culture trypomastigotes, Dm28c strain) [35]. Akin to the findings made in the above-mentioned studies, we found that topically applied HOE-140 (B2R antagonist) markedly reduced L. major (WT-) induced plasma leakage (Figure 1(a)).

Figure 1.

Microvascular plasma leakage and leukocyte accumulation in the HCP sensitized with Leishmania. The data represent relative fluorescence units (RFU: mean ± SD) induced by the topical application of L. major promastigotes (MHOM/JL/80/Friedlin, 500 μL of 1,5 × 107/mL) on hamster cheek pouch preparations (HCPs) after 30 min of stabilization period without significant increase in RFU. Applications of promastigotes were made during 10 min of interrupted superfusion of the HCPs. (a) Pharmacological interventions. Four groups of HCP were sensitized with L. major WT promastigotes, whereas one group (saline control; n = 6) served as untreated control. The first group (n = 15) corresponds to the positive controls, that is, profile of HCP exposed to L. major alone; the second group (n = 5) received HOE-140 (0.5 μM) 5 min prior to promastigote application; the third group (n = 4) received the antagonist of histamine receptor (H1R) mepyramine (10 μM) 5 min prior to challenge with promastigotes; and the fourth group (n = 7) was pretreated (i.v.) with dextran sulfate 500 (DXS-500; 2 mg/kg) at time of FITC-dextran injection. Plasma leakage was significantly reduced (P < 0.05) in all experimental groups subjected to pharmacological interventions. (b) Effect of the mast cell stabilizer cromoglycate. Data represent mean values ± SD obtained in HCP sensitized by L. major WT (n = 4) and a saline control group (n = 6). Two hamsters were given cromoglycate 40 mg/kg i.p. at time of anesthesia induction, and this treatment resulted in a complete inhibition of plasma leakage and leukocyte accumulation elicited by L. major despite the fact that the HCPs responded to histamine stimuli (4 μM) at the end of the experiment, that is, 60 min after topical application of L. major promastigotes. As an internal control, one hamster from the DXS-treated group (n = 7, Figure 1(a)) received rhodamine i.v. prior to parasite challenge. Measurements of leukocyte accumulation showed that DXS-500 reduced the Leishmania response to levels below the saline control group while plasma leakage decreased to the level of controls depicted in Figure 1(a) (data not shown). (c) Comparative analysis of kinin/B2R-driven microvascular plasma leakage induced by different Leishmania species. The graph depicts responses evoked by L. major WT and L. chagasi promastigotes (500 μL de 1,5 × 107/mL). L. major WT (blue filled circles, n = 19); L. chagasi (brown filled circles, n = 6); L. chagasi + captopril 1 μM (black crosses, n = 4); L. chagasi + o.5 μM HOE-140 (red squares, n = 4); L. chagasi + 10 μM mepyramine (orange triangles, n = 4); and saline control (grey diamonds, n = 3). The maximal microvascular response to L. major was 5-fold higher than L. chagasi at 50 min after parasite application. The tests involving pharmacological interventions in HCP sensitized with L. chagasi groups were different (P < 0.05) from the L. chagasi control at 40 min. (d) Microvascular plasma leakage elicited by L. major Δisp2/3. The data represent mean values ± SD. One group represents the microvascular responses evoked by WT L. major (MHOM/JL/80/Friedlin, n = 19) whereas the second group represents responses induced by L. major Δisp2/3 (n = 16). The plasma leakage induced by WT versus Δisp2/3 promastigotes was significantly different (*P < 0.05) between 25 and 60 min after topical application of the pathogens.

Figure 3.

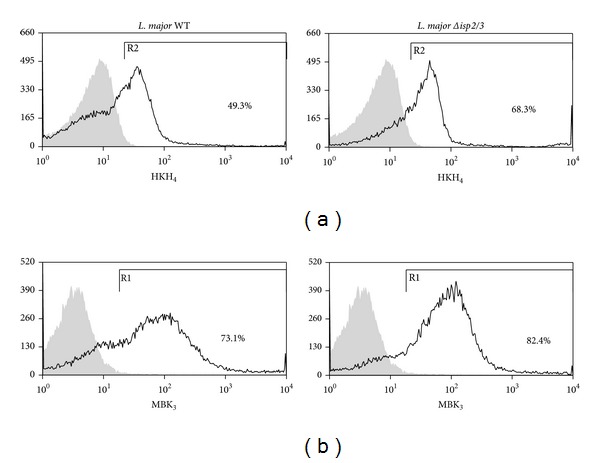

Evidence of differential display of kininogens and BK epitopes on surface of WT L. major versus Δisp2/3 promastigotes. WT and Δisp2/3 promastigotes were washed 3x before incubation with mAbs against D1 or D4 (BK epitope) of kininogens, HK/LK (HKH4 (a) or MBK3 (b), resp.) for 1 h. Unrelated Ab (IgG2a for HKH4 or IgG1 for MBK3 staining) were used as specificity controls. Binding of primary IgG was assessed by incubating the cells with a secondary FITC-labeled anti-mouse IgG antibody for 1 h. The graphs represent the percentage of HK/LK adsorption and are representative of two independent experiments performed in duplicates.

Considering that mast cells are innate sentinel cells strategically localized in the perivascular tissues, we next interrogated whether L. major promastigotes might evoke plasma leakage in mast cell-dependent manner. As shown in Figure 1(a), the topical addition of mepyramine (histamine-1-receptor blocker) markedly inhibited the macromolecular leakage induced by L. major promastigotes. In a limited series of studies, we found that cromoglycate, a well-known mast cell stabilizer, abolished the L. major-induced leakage of plasma (Figure 1(b), lower panel). Of further interest, cromoglycate prevented leukocyte accumulation in the parasite-laden microvascular beds, reducing this parameter to levels below controls (Figure 1(b), top panel). It is noteworthy that the doses of mepyramine and HOE-140 that were topically added to the HCP at the onset of infection were sufficient to block the leakage induced by standard solutions of histamine (4 μM) and BK (0.5 μM) [35]. Further expanding this investigation, we next explored the possibility that the microvascular leakage elicited by L. major promastigotes requires the participation of circulating neutrophils. To this end, we injected separate group of hamsters intravenously with DXS, a negatively charged polymer (500 kDa) and found that it profoundly inhibited plasma leakage induced by L. major promastigotes. Although DXS was initially thought to inhibit neutrophil-dependent microvascular permeability by blocking endothelial interaction with neutrophil-derived cationic proteins [41–44], there is now awareness that these effects might result from DXS-mediated activation of the KKS, a systemic reaction that leads to hypotension as result of excessive BK formation [45].

Finally, we sought to compare the microvascular responses elicited by WT L. major with their counterparts genetically deficient in ISP-2/ISP-3. As shown in Figure 1(d), the dynamics of plasma leakage induced by topically applied Δisp2/3 mutants was similar to that evoked by WT parasites, the peak response being observed at 45–50 min after pathogen application. However, somewhat surprisingly, the Δisp2/3 mutants were 20% less effective in eliciting transendothelial leakage of plasma as compared to WT promastigotes (Figure 1(d)); the difference in their proinflammatory phenotypes (P < 0.05) was already noticeable at 25 min after parasite application.

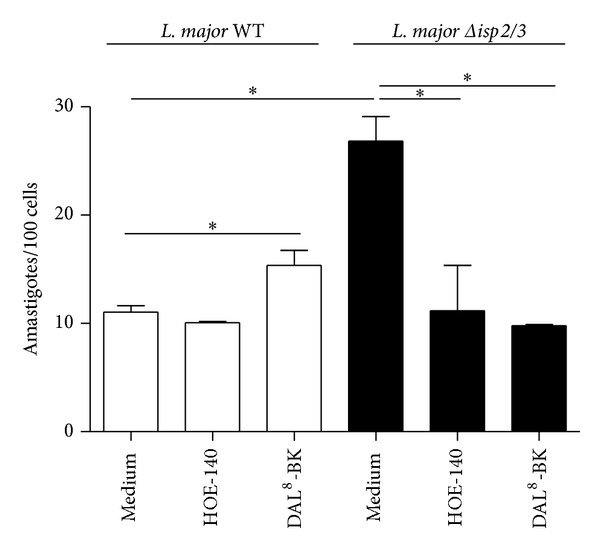

3.2. Bradykinin Receptors Selectively Fuel Macrophage Internalization of ISP-Deficient L. major

Studies in mice models of acute Chagas disease [14] and visceral leishmaniasis [16] have recently showed that B2R-deficient mice exhibited impaired development of type-1 effector T cells, the immune dysfunction of the transgenic strain being ascribed to primary deficiency in the maturation of B2R−/− DCs in chagasic mice [14]. In a third study, we examined the role of the kinin pathway in the in vitro outcome of macrophage interactions with L. chagasi promastigotes [15]. Interestingly, these studies revealed that activation of the kinin/B2R pathway may either fuel intracellular parasite outgrowth in splenic macrophages from hamsters, a species that is susceptible to visceral leishmaniasis, or limit parasite survival in thioglycolate-elicited mouse peritoneal macrophages [16]. Motivated by this groundwork, in the next series of experiments we examined the outcome of macrophage interaction (3 h in the absence of serum) with L. major promastigotes or Δisp2/3 mutants. Consistent with the phenotypic properties of Δisp2/3 promastigotes originally described by Eschenlauer et al. [27], we found that the phagocytic uptake of these mutants was strongly upregulated as compared to WT promastigotes (Figure 2). Next, we asked whether B2R (constitutively expressed) or B1R (NFκ-B inducible; [35]) contributed to the phagocytic uptake of L. major. Infection assays performed in the presence of HOE-140 or DAL8-BK (B1R antagonist) revealed that none of these GPCR antagonists inhibited macrophage uptake of ISP-expressing (WT) L. major. In striking contrast, however, both GPCR antagonists efficiently reduced the phagocytic uptake of Δisp2/3 promastigotes by the phagocytes (resp., to 58% and 63%; Figure 2). For reasons that are not clear, the B1R antagonist had a mild but significant stimulatory effect (39% increase compared with medium) on the uptake of WT L. major.

Figure 2.

Differential role for bradykinin receptors in the phagocytic response of macrophages infected by WT L. major promastigotes and Δisp2/3 mutants. Thioglycolate elicited (peritoneal) macrophages were incubated in medium containing 1 mg/mL BSA in the presence or absence of 100 nM of HOE-140 or 1 μm of des-Arg9-[Leu8]-BK (DAL8-BK). Promastigotes were added (parasite/cell ratio 5 : 1) and incubated for 3 h at 37°C. White bars represent L. major WT and black bars represent Δisp2/3. Data represent numbers of intracellular amastigotes per 100 macrophages (means ± SD) for triplicates and represent two different experiments (*P < 0.05).

3.3. Surface Exposure of the BK Epitope Differs in WT and Δisp2/3 Promastigotes

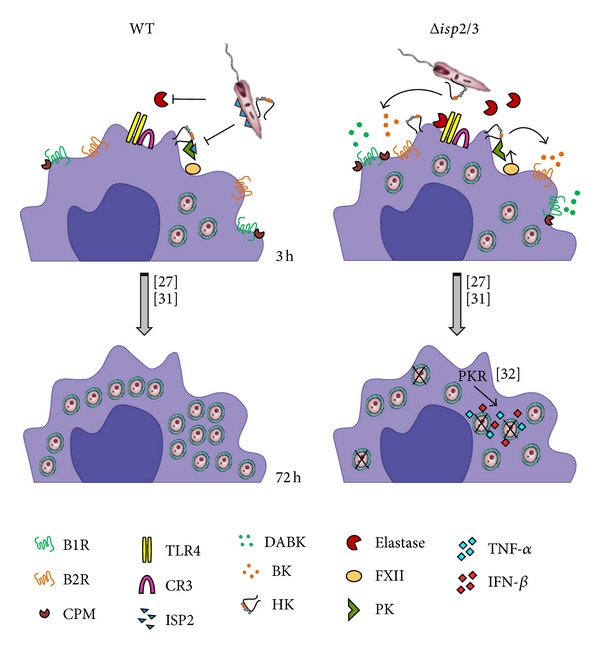

Since the studies of macrophage infection by L. major promastigotes were routinely performed in the absence of serum, we reasoned that the kinin agonists should either originate from kininogens molecules bound to the surface of macrophages [46] or alternatively from kininogen molecules eventually sequestered from serum by promastigotes. To test the latter possibility, we washed stationary phase L. major promastigotes extensively as described for infection assays and then stained the parasites with two different domain-specific mAbs: (i) MBK3, a monoclonal antibody that recognizes the BK epitope (domain D4) of kininogens (HK/LK), and (ii) HKH4, a mAb that recognizes domain D1 of HK/LK [36]. FACS analysis showed that almost 70% of Δisp2/3 promastigotes are positive stained for HKH4, compared to less than 50% of the WT parasites (Figure 3(a)). Along similar lines, MBK3 antibody showed that the BK epitope of kininogens was present in a higher proportion of Δisp2/3 promastigotes as compared to WT promastigotes (Figure 3(b), 82,4%) as compared to WT parasites (Figure 3(b), 73.1%). These results suggest that both ISP-expressing L. major promastigotes and Δisp2/3 mutants are able to sequester kininogens (retaining the intact BK molecule) from FCS. According to our working hypothesis (Figure 5), the kininogen opsonins tethered on ISP-deficient parasites may be cleaved by pericellular serine proteases (S1a family) of macrophages, whereas the surface-bound kininogens associated to ISP-expressing (WT) L. major should be protected from proteolytic cleavage.

Figure 5.

Scheme shows how ISP-2 limits the kinin-releasing activity of surface S1A-proteases of macrophages. As an extension of recently published studies [27, 31, 32], here we propose that the proinflammatory phenotype of the Δisp2/3 mutant (right side of scheme) is due to increased pericellular release of kinins mediated by NE and/or contact phase serine proteases (FXIIa/PKa). In the absence of ISP-2, the “eat me signal” of kininogen tethered on L. major mutants might be inactivated by S1A-family proteases. In addition, the released kinin peptides fuel phagocytosis and microbicidal function of macrophages via activation of B2R and B1R, a subtype of GPCR upregulated in inflamed tissues.

3.4. Targeting Activation of the Contact Phase/KKS in Human Plasma with Recombinant ISP-2 or Synthetic Inhibitor of Neutrophil Elastase

Considering that ISP-2 is hardly detected in the supernatants of L. major promastigotes (A. P. C. A. Lima, personal communication), we reasoned that we reasoned that this ecotin-like inhibitor may target S1A serine proteases within the secluded spaces formed by the juxtaposition of host cell/parasite plasma membranes. Given the technical obstacles to monitor KKS activation and kinin release in this intercellular compartment, we first asked whether soluble (recombinant) ISP-2 or MeOSuc-AAPV-CMK (NE inhibitor) could inhibit the activation of the human contact system by DXS. This was addressed using a novel enzymatic assay that we recently used to detect the P. duboscq sandfly protein inhibitor of the contact system [25]. Briefly, the addition of DXS (500 kDa) to human plasma induces the reciprocal activation of FXII/PK, leading to the accumulation of PKa, the major kinin-releasing (S1A family) in the plasma. Using as-read-outs synthetic substrates spanning the N-terminal or C-terminal flanking sequences of BK in the kininogen molecule, the kinetic measurements shown in our positive controls (Figure 4) reflect DXS-induced hydrolysis of the kininogen-like substrate by PKa [25]. Internal controls run in the presence of the synthetic PKa inhibitor (PKSI-257) show, as expected, pronounced inhibition of the contact phase enzyme by DXS. Assays performed with soluble ISP-2 revealed that the onset of hydrolysis was consistently delayed, in dose-dependent manner (range 142–355 nM; Figures 4(a) and 4(b)). A similar trend was observed when we added MeOSuc-AAPV-CMK (NE inhibitor) to the citrated plasma (range 10–30 μM; Figures 4(c) and 4(d)). Collectively, these findings are consistent with the proposition that the activity of the contact phase enzyme complex (FXIIa/PKa) is at least partially inhibited by ISP-2 (soluble) or by the synthetic NE inhibitor.

Figure 4.

Effect of ISP2 on DXS-induced contact phase activation of human plasma. Citrated human platelet free plasma diluted 1 : 20 in buffer (described in methods) was supplemented with (i) 4 μM Abz-MTEMARRPQ-EDDnp (a, c) or 4 μM Abz-GFSPFRSVTVQ-EDDnp (b, d), intramolecular quenched fluorescent substrates whose sequences span the N-terminal or the C-terminal flanking sites (resp.) of BK in mHK (ii) dextran sulfate 500 kDa (DXS; 20 nM). The substrate was also tested in the absence of DXS (Control). Assays with the elastase inhibitor (NEi—MeOSuc-AAPV-CMK-10, 20, and 30 μM), the synthetic PKa inhibitor (PKSI-527—5 μM), and the inhibitor of serine peptidase 2 (ISP2—142, 177, 240, and 355 nM) were performed using two different schemes. (a, b) PKSI or the elastase inhibitor was added to the plasma together with DXS and the substrate. (c, d) PKSI or ISP2 was preincubated with plasma for 15 min, at 37°C, prior to the addition of DXS and the substrate. Hydrolysis was followed by measuring the fluorescence at λ ex. = 320 nm and λ em. = 420 nm (up to 1800 seconds). The plot shows the increase of fluorescence with time, reflecting substrate hydrolysis. The values in the figures represent the mean ± SE of duplicate determinations performed within 1 representative experiment of 2.

4. Discussion

In the current study, we used genetically modified Δisp2/3 mutants of L. major to determine whether these ecotin-like inhibitors regulate the proinflammatory activity of the kinin/B2R pathway in vivo and in vitro. In the first group of studies, we demonstrated that L. major promastigotes potently evoke plasma leakage and induce leukocyte accumulation in microvascular beds through mast cell-dependent activation of the kinin/B2R pathway, irrespective of the presence or absence of ISP-2. Extending this analysis to in vitro infection models, we showed that antagonists of B2R (HOE-140) or B1R (DAL8-BK) efficiently reversed the upregulated phagocytic uptake of L. major Δisp2/3 by TG-macrophages without interfering with the internalization of ISP-expressing (WT) promastigotes. As discussed further below, these findings suggested that, upon attachment to the macrophage surface, ISP-expressing promastigotes might suppress the activation of B2R/B1R-dependent proinflammatory responses by inhibiting the kinin-releasing activity of serine proteases (S1A family).

While studying the functional interplay between NE and ISP-2 during macrophage infection by Leishmania, Faria et al. [31, 32] demonstrated that two prominent phenotypes of Δisp2/3 mutants (upregulated phagocytosis and induction of ROS via the elastase/TLR4/PKR pathway) were completely reversed in cultures supplemented with three different inhibitors of serine peptidases: aprotinin [27], a non-specific inhibitor of Arg-hydrolyzers, MeOSuc-AAPV-CMK (NE inhibitor), and the L. major ISP-2 (soluble/recombinant). Given the precedent that NE and mast cell tryptase (acting cooperatively) liberate bioactive kinin from oxidized kininogens [7], our findings that HOE-140 and DAL8-BK also reversed the phenotype of Δisp2/3 mutants suggest that ISP-expressing L. major might inhibit the pericellular processing of surface-bound HK through the targeting of NE. Alternatively, our finding that soluble ISP-2 (or the NE inhibitor MeOSuc-AAPV-CMK) partially inhibit DXS-induced activation of the contact system in human citrated plasma (i.e., PKa-mediated hydrolysis of the flanking sites of BK in kininogen-like substrates) suggests that ISP-expressing promastigotes might rely on their surface-associated ISP-2 to target the contact phase enzymatic complex (FXIIa/PKa/HK) assembled on macrophage surfaces [46]. Admittedly, genetic studies will be required to dissect whether ISP-2 subverts innate immunity by protecting surface kininogens from the kinin-releasing activity of NE and/or by targeting surface assembled contact phase peptidases (FXII/PK). Although we have not systematically analyzed the impact of pharmacological blockade of B2R/B1R on the intracellular parasitism of TG-macrophages, preliminary results suggest that HOE-140 (tested at 100 nM) upregulates the outgrowth/survival of Δisp2/3 mutants in TG-macrophages. If confirmed by genetic studies, our results may imply that L. major promastigotes might limit ROS formation via the NE/TLR4/PKR/TNF-α/IFN-β pathway originally described by Faria et al. [32] through ISP-2-dependent targeting of kinin-releasing peptidases assembled at the surface of macrophages.

A key event in many inflammatory processes is the adhesive interaction of circulating neutrophils and activated endothelial cells in postcapillary venules, a process that is often coupled to increased microvascular permeability, which in turn leads to the progressive accumulation of protein-rich edema fluid in interstitial tissues. Although conceding that the dynamics of the inflammatory responses that sand-fly-transmitted Leishmania induces in the injured dermis is far more complex than what is described in our intravital microscopy studies, the analysis of microvascular leakage and leukocyte accumulation in HCP topically sensitized with L. major promastigotes (WT or ISP2/3-deficient parasites) revealed that these parasites are far more potent inducers of plasma leakage and leukocyte accumulation than L. donovani [15], L. chagasi promastigotes (Figure 1(c)), or T. cruzi trypomastigotes [35]. Although the mechanisms underlying the discrepant phenotypes of L. major and L. chagasi or T. cruzi remain unknown, we were intrigued to find out that a 3X-fold higher dose of L. chagasi promastigotes did not evoke such a strong microvascular response, not even after treating the HCP with captopril, an inhibitor of kinin degradation by angiotensin-converting enzyme (Figure 1(c), black curve). In contrast, T. cruzi and L. chagasi are potentially lethal pathogens that disseminate systemically and preferentially target tissue in organs irrigated by fenestrated capillaries. Under these circumstances, plasma-borne substrates, such as kininogens, diffuse freely into the visceral tissues invaded by these visceralizing species of pathogenic trypanosomatids, both of which were empowered with kinin-releasing cysteine proteases [15, 47–49]. It is noteworthy that B2R-deficient mice acutely infected by T. cruzi [14] or L. chagasi [16] display heightened disease susceptibility, implying that the activation of the kinin/B2R pathway may preferentially shift the host/parasite balance towards protective immunity, at least during the acute phase.

Since proboscis inevitably provokes some extent of bleeding, we may predict plasma proteins and anti-inflammatory substances derived from the insect saliva are rapidly mixed with metacyclic parasites. Our studies in HCP topically sensitized with L. major promastigotes (which prevents bleeding and KKS activation due to pathogen inoculation through needles) suggest that these parasites potently evoke plasma leakage and leukocyte accumulation in microvascular beds via the kinin/B2R pathway. For reasons that are unclear, we found that Δisp2/3 promastigotes evoked a somewhat milder inflammatory response (20%). Incidentally, Eschenlauer et al. [27] have reported that mice subcutaneously infected with L. major promastigotes transiently displayed higher tissue burden of ISP2/ISP-3-deficient parasites as compared to WT parasites. Lasting 3 days, the parasite burden subsequently equalized, implying that the selective advantage conferred to ISP-deficient promastigotes has waned as the infection progressed.

Based on pharmacological approaches, we showed evidences that L. major activates the KKS via mechanisms that involve transcellular cross-talk between neutrophils (intravascularly) and mast cells, a subset of innate sentinel cells that are mostly localized in perivascular tissues. Beyond the vasoactive role of histamine, a potent inducer of vascular permeability, mast cells also release heparin and polyphosphates, both of which were recently characterized as endogenous activators of the contact system [50, 51]. Given the interdependent nature of inflammatory circuits, it is likely that mast cells and the KKS/complement cascades are reciprocally activated and fueled in the HCP sensitized with L. major promastigotes. Although we have not studied the impact of the influx of complement into peripheral sites of L. major infection, it is well-documented that Leishmania lipophosphoglycan is opsonized by C3bi [52]. In the absence of other potent inflammatory cues, the engagement of macrophage CR3 by ISP-expressing L. major (WT) promastigotes may drive phagocytosis without necessarily stimulating the production of reactive oxygen intermediates, thereby creating a hospitable environment for the intracellular growth of L. major [31, 32]. Although studies in CD11b-deficient BALB/c mice have recently confirmed that activation of the C3bi/CR3 pathway increases host susceptibility to L. major infection [53], it will be interesting to know whether CR3-dependent suppression of IL-12 responses might depend on parasite-evoked extravasation of complement components to the extravascular compartment, as proposed here for plasma-borne kininogens.

Studies in the mouse ear model of sandfly-transmitted infection showed that L. major metacyclic promastigotes deposited in the dermis are engulfed by the infiltrating neutrophils within approximately 3 h [19–21]. Based on the results described in HCP topically sensitized with L. major promastigotes, it is conceivable that the proteolytic release of vasoactive kinins may further stimulate the transendothelial migration of neutrophils at very early stages of the infection. Furthermore, given evidence that parasitized neutrophils expose the apoptotic markers required for efferocytosis, it will be interesting to know whether plasma leakage may contribute to DC efferocytosis and to the ensuing suppression of Th1-inductive functions of DCs in the draining lymph nodes [19–21]. Beyond the impact on adaptive immunity, it is well established that efferocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils has profound effect on parasite survival in infected macrophages [22]. In this context, our finding that kininogen epitopes (N-terminal D1 and internal/BK/D4 domain) are tethered at the surface of Leishmania promastigotes is an intriguing finding because it raises the possibility that ISP-expressing promastigotes might “protect” the integrity of surface bound kinin precursors from premature proteolytic degradation by host proteolytic enzymes. This hypothesis is worth exploring in light of recent studies showing that HK (an abundant protein in the bloodstream; 660 nM) binds to PS exposed on apoptotic neutrophils before stimulating uPAR-dependent efferocytosis by macrophages via the p130Cas-CrkII-Dock-180-Rac1 pathway [6]. In other words, ISPs may protect the integrity of HK opsonins “eat me signals” while at the same time preventing the liberation of proinflammatory kinins (see scheme, Figure 5) within sites of parasite attachment to phagocytes. Although we have not explored the potential significance of L. major opsonization by kininogens, it will be interesting to know whetherparasite subsets bearing the uPAR ligand HK/HKa “eat me signal” might render macrophage permissive to intracellular survival, perhaps reminiscent of the apoptotic mimicry paradigm originally described by Barcinski and coworkers [54].

5. Conclusions

Extending the breadth of our previous investigations about the role of the kallikrein-kinin system in the immunopathogenesis of experimental Chagas disease and visceral leishmaniasis, the studies reported in this paper suggest that ecotin-like inhibitors expressed by L. major promastigotes fine-tune phagocytosis and may limit amastigote survival by inhibiting the pericellular activity of kinin-releasing serine proteases (S1a family) of macrophages.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from CNPq/INBEB, Faperj, and PRONEX. The authors thank Professor Ana Paula Cabral de Araujo Lima (Instituto de Biofísica Carlos Chagas Filho, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro) for kindly providing WT and Δisp2/3 L. major and inhibitor of serine peptidase 2 (ISP2) and Professor Werner Müller-Esterl (University of Frankfurt) for donation of anti-kininogen antibodies. They also wish to thank Dr. Marilia Faria (Instituto de Biofísica Carlos Chagas Filho, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro) for independently testing the B2R and B1R antagonists in infection assays with macrophages (unpublished data).

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Kaplan AP, Joseph K. Pathogenic mechanisms of bradykinin mediated diseases: dysregulation of an innate inflammatory pathway. Advances in Immunology. 2014;121:41–89. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800100-4.00002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maas C, Renné T. Regulatory mechanisms of the plasma contact system. Thrombosis Research. 2012;129(2):S73–S76. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2012.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amara U, Flierl MA, Rittirsch D, et al. Molecular intercommunication between the complement and coagulation systems. Journal of Immunology. 2010;185(9):5628–5636. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ricklin D, Hajishengallis G, Yang K, Lambris JD. Complement: a key system for immune surveillance and homeostasis. Nature Immunology. 2010;11(9):785–797. doi: 10.1038/ni.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wachtfogel YT, deLa Cadena RA, Kunapuli SP, et al. High molecular weight kininogen binds to Mac-1 on neutrophils by its heavy chain (domain 3) and its light chain (domain 5) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269(30):19307–19312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang A, Dai J, Xie Z, et al. High molecular weight kininogen binds phosphatidylserine and opsonizes urokinase plasminogen activator receptor-mediated efferocytosis. The Journal of Immunology. 2014;192(9):4398–4408. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kozik A, Moore RB, Potempa J, Imamura T, Rapala-Kozik M, Travis J. A novel mechanism for bradykinin production at inflammatory sites: Diverse effects of a mixture of neutrophil elastase and mast cell tryptase versus tissue and plasma kallikreins on native and oxidized kininogens. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(50):33224–33229. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heutinck KM, ten Berge IJM, Hack CE, Hamann J, Rowshani AT. Serine proteases of the human immune system in health and disease. Molecular Immunology. 2010;47(11-12):1943–1955. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aliberti J, Viola JPB, Vieira-de-Abreu A, Bozza PT, Sher A, Scharfstein J. Cutting edge: bradykinin induces IL-12 production by dendritic cells: a danger signal that drives Th1 polarization. Journal of Immunology. 2003;170(11):5349–5353. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bertram CM, Baltic S, Misso NL, et al. Expression of kinin B1 and B2 receptors in immature, monocyte-derived dendritic cells and bradykinin-mediated increase in intracellular Ca2+ and cell migration. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2007;81(6):1445–1454. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0106055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gulliver R, Baltic S, Misso NL, Bertram CM, Thompson PJ, Fogel-Petrovic M. Lys-des[Arg9]-bradykinin alters migration and production of interleukin-12 in monocyte-derived dendritic cells. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2011;45(3):542–549. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0238OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marceau F, Bachvarov DR. Kinin receptors. Clinical Reviews in Allergy and Immunology. 1998;16(4):385–401. doi: 10.1007/BF02737658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monteiro AC, Schmitz V, Svensjö E, et al. Cooperative activation of TLR2 and bradykinin B2 receptor is required for induction of type 1 immunity in a mouse model of subcutaneous infection by Trypanosoma cruzi . Journal of Immunology. 2006;177(9):6325–6335. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monteiro AC, Schmitz V, Morrot A, et al. Bradykinin B2 Receptors of dendritic cells, acting as sensors of kinins proteolytically released by Trypanosoma cruzi, are critical for the development of protective type-1 responses. PLoS Pathogens. 2007;3(11):1730–1744. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Svensjö E, Batista PR, Brodskyn CI, et al. Interplay between parasite cysteine proteases and the host kinin system modulates microvascular leakage and macrophage infection by promastigotes of the Leishmania donovani complex. Microbes and Infection. 2006;8(1):206–220. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nico D, Feijó DF, Maran N. Resistance to visceral leishmaniasis is severely compromised in mice deficient of bradykinin B2-receptors. Parasites and Vectors. 2012;5(1, article 261) doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scharfstein J, Andrade D, Svensjö E, Oliveira AC, Nascimento CR. The kallikrein-kinin system in experimental Chagas disease: a paradigm to investigate the impact of inflammatory edema on GPCR-mediated pathways of host cell invasion by Trypanosoma cruzi . Frontiers in Immunology. 2007;3(396):1–20. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engelmann B, Massberg S. Thrombosis as an intravascular effector of innate immunity. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2013;13(1):34–45. doi: 10.1038/nri3345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peters NC, Egen JG, Secundino N, et al. In vivo imaging reveals an essential role for neutrophils in leishmaniasis transmitted by sand flies. Science. 2008;321(5891):970–974. doi: 10.1126/science.1159194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peters NC. In vivo imaging reveals an essential role for neutrophils in Leishmaniasis transmitted by sand flies. Science. 2008;322(5908):p. 1634. doi: 10.1126/science.1159194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ribeiro-Gomes FL, Peters NC, Debrabant A, Sacks DL. Efficient capture of infected neutrophils by dendritic cells in the skin inhibits the early anti-leishmania response. PLoS Pathogens. 2012;8(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002536.e1002536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ribeiro-Gomes FL, Moniz-de-Souza MCA, Alexandre-Moreira MS, et al. Neutrophils activate macrophages for intracellular killing of Leishmania major through recruitment of TLR4 by neutrophil elastase. The Journal of Immunology. 2007;179(6):3988–3994. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Filardy AA, Pires DR, Dosreis GA. Macrophages and neutrophils cooperate in immune responses to Leishmania infection. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2011;68(11):1863–1870. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0653-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Titus RG, Ribeiro JMC. The role of vector saliva in transmission of arthropod-borne disease. Parasitology Today. 1990;6(5):157–160. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(90)90338-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alvarenga PH, Xu X, Oliveira F, et al. Novel family of insect salivary inhibitors blocks contact pathway activation by binding to polyphosphate, heparin, and dextran sulfate. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2013;33(12):2759–2770. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Müller F, Mutch NJ, Schenk WA, et al. Platelet polyphosphates are proinflammatory and procoagulant mediators in vivo. Cell. 2009;139(6):1143–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eschenlauer SCP, Faria MS, Morrison LS, et al. Influence of parasite encoded inhibitors of serine peptidases in early infection of macrophages with Leishmania major . Cellular Microbiology. 2009;11(1):106–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01243.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chung CH, Ives HE, Almeda S, Goldberg AL. Purification from Escherichia coli of a periplasmic protein that is a potent inhibitor of pancreatic proteases. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1983;258(18):11032–11038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eggers CT, Murray IA, Delmar VA, Day AG, Craik CS. The periplasmic serine protease inhibitor ecotin protects bacteria against neutrophil elastase. The Biochemical Journal. 2004;379(1):107–118. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ivens AC, Peacock CS, Worthey EA. The genome of the kinetoplastid parasite, Leishmania major . Science. 2005;309(5733):436–442. doi: 10.1126/science.1112680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Faria MS, Reis FCG, Azevedo-Pereira RL, Morrison LS, Mottram JC, Lima APCA. Leishmania inhibitor of serine peptidase 2 prevents TLR4 activation by neutrophil elastase promoting parasite survival in murine macrophages. The Journal of Immunology. 2011;186(1):411–422. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faria MS, Calegari-Silva TC, de Carvalho A, Vivarini JC, Lopes UG, Lima AP. Role of protein kinase R in the killing of Leishmania major by macrophages in response to neutrophil elastase and TLR4 via TNFα and IFNβ . The FASEB Journal. 2014;28(7):3050–3063. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-245126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmitz V, Almeida LN, Svensjö E, Monteiro AC, Köhl J, Scharfstein J. C5a and bradykinin receptor cross-talk regulates innate and adaptive immunity in Trypanosoma cruzi infection. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302417. The Journal of Immunology. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmitz V, Svensjö E, Serra RR, Teixeira MM, Scharfstein J. Proteolytic generation of kinins in tissues infected by Trypanosoma cruzi depends on CXC chemokine secretion by macrophages activated via Toll-like 2 receptors. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2009;85(6):1005–1014. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1108693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andrade D, Serra R, Svensjö E, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi invades host cells through the activation of endothelin and bradykinin receptors: a converging pathway leading to chagasic vasculopathy. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2012;165(5):1333–1347. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01609.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaufmann J, Haasemann M, Modrow S, Müller-Esterl W. Structural dissection of the multidomain kininogens. Fine mapping of the target epitopes of antibodies interfering with their functional properties. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268(12):9079–9091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Korkmaz B, Attucci S, Juliano MA, et al. Measuring elastase, proteinase 3 and cathepsin G activities at the surface of human neutrophils with fluorescence resonance energy transfer substrates. Nature Protocols. 2008;3(6):991–1000. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fukumizu A, Tsuda Y. Amino acids and peptides. LIII. Synthesis and biological activities of some pseudo-peptide analogs of PKSI-527, a plasma kallikrein selective inhibitor: the importance of the peptide backbone. Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 1999;47(8):1141–1144. doi: 10.1248/cpb.47.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Svensjö E. Bradykinin and prostaglandin E1, E2 and F2α-induced macromolecular leakage in the hamster cheek pouch. Prostaglandines and Medicine. 1978;1(5):397–410. doi: 10.1016/0161-4630(78)90126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Svensjö E, Andersson KE, Bouskela E, Cyrino FZGA, Lindgren S. Effects of two vasodilatory phosphodiesterase inhibitors on bradykinin-induced permeability increase in the hamster cheek pouch. Agents and Actions. 1993;39(1-2):35–41. doi: 10.1007/BF01975712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosengren S, Ley K, Arfors K-E. Dextran sulfate prevents LTB4-induced permeability increase, but not neutrophil emigration, in the hamster cheek pouch. Microvascular Research. 1989;38(3):243–254. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(89)90003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Höcking DC, Ferro TJ, Johnson A. Dextran sulfate inhibits PMN-dependent hydrostatic pulmonary edema induced by tumor necrosis factor. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1991;70(3):1121–1128. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.70.3.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brown RA, Lever R, Jones NA, Page CP. Effects of heparin and related molecules upon neutrophil aggregation and elastase release in vitro. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2003;139(4):845–853. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ley K, Cerrito M, Arfors K-E. Sulfated polysaccharides inhibit leukocyte rolling in rabbit mesentery venules. American Journal of Physiology. Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 1991;260(5):H1667–H1673. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.260.5.H1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Siebeck M, Cheronis JC, Fink E, et al. Dextran sulfate activates contact system and mediates arterial hypotension via B2 kinin receptors. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1994;77(6):2675–2680. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.6.2675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barbasz A, Kozik A. The assembly and activation of kinin-forming systems on the surface of human U-937 macrophage-like cells. Biological Chemistry. 2009;390(3):269–275. doi: 10.1515/BC.2009.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.del Nery E, Juliano MA, Lima APCA, Scharfstein J, Juliano L. Kininogenase activity by the major cysteinyl proteinase (cruzipain) from Trypanosoma cruzi . Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(41):25713–25718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lima APCA, Almeida PC, Tersariol ILS, et al. Heparan sulfate modulates kinin release by Trypanosoma cruzi through the activity of cruzipain. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(8):5875–5881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108518200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scharfstein J, Schmitz V, Morandi V, et al. Host cell invasion by Trypanosoma cruzi is potentiated by activation of bradykinin B2 receptors. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2000;192(9):1289–1299. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.9.1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oschatz C, Maas C, Lecher B, et al. Mast cells increase vascular permeability by heparin-initiated bradykinin formation in vivo . Immunity. 2011;34(2):258–268. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moreno-Sanchez D, Hernandez-Ruiz L, Ruiz FA, Docampo R. Polyphosphate is a novel pro-inflammatory regulator of mast cells and is located in acidocalcisomes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2012;287(34):28435–28444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.385823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Späth GF, Garraway LA, Turco SJ, Beverley SM. The role(s) of lipophosphoglycan (LPG) in the establishment of Leishmania major infections in mammalian hosts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(16):9536–9541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530604100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carter CR, Whitcomb JP, Campbell JA, Mukbel RM, McDowell MA. Complement receptor 3 deficiency influences lesion progression during Leishmania major infection in BALB/c Mice. Infection and Immunity. 2009;77(12):5668–5675. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00802-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wanderley JLM, Barcinski MA. Apoptosis and apoptotic mimicry: the Leishmania connection. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2010;67(10):1653–1659. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0291-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]