Abstract

Introduction

In the prospective, open-label multicenter INTENSIFY study, the effectiveness and tolerability of ivabradine as well as its impact on quality of life (QOL) in chronic systolic heart failure (CHF) patients were evaluated over a 4-month period.

Methods

In CHF patients with an indication for treatment with ivabradine, resting heart rate (HR), heart failure symptoms [New York Heart Association (NYHA) class, signs of decompensation], left ventricular ejection fraction, brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) values, QOL, and concomitant medication with focus on beta-blocker therapy were documented at baseline, after 4 weeks, and after 4 months. The results were analyzed using descriptive statistical methods.

Results

Thousand nine hundred and fifty-six patients with CHF were included. Their mean age was 67 ± 11.7 years and 56.9% were male. 77.8% were receiving beta-blockers. Other concomitant medications included angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (83%), diuretics (61%), aldosterone antagonists (18%), and cardiac glycosides (8%). At baseline, the mean HR of patients was 85 ± 11.8 bpm, 51.1% and 37.2% of patients were classified as NYHA II and III, respectively, and 22.7% showed signs of decompensation. BNP concentrations were tracked in a subgroup, and values exceeding 400 pg/mL were noted in 53.9% of patients. The mean value of the European quality of life-5 dimensions (EQ-5D) QOL index was 0.64 ± 0.28. After 4 months of treatment with ivabradine, HR was reduced to 67 ± 8.9 bpm. Furthermore, the proportion of patients presenting with signs of decompensation decreased to 5.4% and the proportion of patients with BNP levels >400 pg/mL dropped to 26.7%, accompanied by a shift in NYHA classification towards lower grading (24.0% and 60.5% in NYHA I and II, respectively). EQ-5D index improved to 0.79 ± 0.21.

Conclusion

Over 4 months of treatment, ivabradine effectively reduced HR and symptoms in CHF patients in this study reflecting daily clinical practice. These benefits were accompanied by improved QOL and good general tolerability.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12325-014-0147-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cardiology, Chronic heart failure, Heart rate, Ivabradine, NYHA class, Quality of life, Symptom reduction

Introduction

Elevated resting heart rate (HR) increases the morbidity and mortality of patients with chronic systolic heart failure (CHF) [1, 2] or coronary artery disease with left ventricular systolic dysfunction [3]. Furthermore, there is substantial evidence that reduction in elevated HR improves the outcome of patients with cardiovascular diseases [4, 5]. Beta-blockers are the primary pharmacological option available to lower HR. They reduce left ventricular load, suppress the adrenergic stimulus, improve myocardial remodeling, and thereby reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [6]. Therefore, beta-blocking agents have been recommended for many years in international guidelines as a standard therapy in CHF [7].

However, many patients on beta-blocker therapy, even if optimized, still present with elevated HR [8, 9]. Other patients have contraindications or cannot be treated with beta-blockers due to intolerable side effects. For several years, ivabradine has been available as an alternative HR-reducing agent. It reduces HR by selectively blocking the “funny” cardiac pacemaker current (I f) channel in the pacemaker cells in the sinoatrial node. In patients with chronic stable angina pectoris, ivabradine has an anti-ischemic and anti-anginal effect comparable to that of beta-blockers [10] and calcium channel blockers [11].

Furthermore, the SHIFT study (Systolic Heart faIlure treatment with the I f inhibitor ivabradine Trial; #ISRCTN70429960) demonstrated that ivabradine also improved the cardiovascular outcome of CHF patients with an elevated HR (≥70 bpm) compared with placebo [12]. The risk for the composite primary end point (cardiovascular death and hospital admission for worsening heart failure) was significantly reduced by 18%. Interestingly, this risk reduction was achieved on top of background pharmacotherapy, including beta-blockers, recommended by heart failure guidelines. A sub-analysis of SHIFT found that patients with an initial HR ≥75 bpm gained a significant benefit from ivabradine compared with placebo in all pre-specified end points, including risk of total mortality, CHF-associated mortality, and hospital admission due to worsening heart failure [13].

Consequently, the European Medicines Agency approved ivabradine for CHF patients in New York Heart Association (NYHA) classes II to IV with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and a resting HR ≥75 bpm, also in combination with beta-blocker therapy. According to very recent registry data, the prescription rates for ivabradine in patients with reduced LVEF in Europe are still low, while angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and beta-blockers are widely used [9]. Thus, data analyzing the use of ivabradine in daily practice are still limited. Therefore, we conducted a prospective, non-interventional, open-label, multicenter study (INTENSIFY; PractIcal daily effectiveNess and TolEraNce of ivabradine in chronic SystolIc heart Failure in GermanY) to collect data on the use and tolerability of ivabradine in an ambulatory setting in patients suffering from CHF treated by cardiologists, specialized general practitioners (GPs), and internists. We focused on the effect of ivabradine on HR reduction, heart failure symptoms, and quality of life (QOL).

Methods

Patients with chronic systolic heart failure fulfilling criteria for treatment with ivabradine according to the approved indication or European guideline [7] recommendations (sinus rhythm, NYHA class II–IV, resting HR ≥70/75 bpm) were included in the study by treating physicians in an outpatient setting (cardiologists, specialized GPs, and internists). There were 3 scheduled visits, one at baseline (visit 1), a control visit after 4 weeks (visit 2), and the final examination after 4 months (visit 3). A standardized case report form was used to record all data.

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 and 2008. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study, which was approved by the independent ethics commission in Freiburg/Germany (FEKI). The trial was registered at Controlled-trials.com, number ISRCTN12600624.

After obtaining informed consent, demographic and disease-specific medical history data, as well as information about concomitant diseases and the reason for initiating ivabradine treatment, were documented at visit 1. Patients were then treated with ivabradine in flexible doses over a 4-month period. The recommended starting dose was 5 mg twice daily (2.5 mg twice daily for patients ≥75 years of age). If necessary, the dose could be adjusted to 7.5 mg twice daily at visit 2.

Heart failure was clinically documented at each visit by recording HR, symptoms, signs of decompensation (meaning ambulatory signs of congestion like peripheral edema, worsening dyspnea, developing ascites, etc.), LVEF, concomitant medications, and QOL using the validated European quality of life-5 dimensions (EQ-5D) patient questionnaire.

To assess the overall response rate of patients to ivabradine, treatment response was defined as achieving an HR <70 bpm or an absolute reduction of at least 10 bpm at visit 3, reflecting the recommendations of the current European Society of Cardiology (ESC) heart failure guidelines [7] for treatment with ivabradine and also the inclusion criteria of the SHIFT trial (≥70 bpm) [12].

Regarding analysis of concomitant medication, the focus was beta-blocker therapy with defined target doses of metoprolol 190 mg/day, carvedilol 100 mg/day, as well as bisoprolol and nebivolol 10 mg/day. For assessment of beta-blocker treatment status of the cohort, patients were divided into three subgroups according to beta-blocker dose at baseline as a percentage (<50%, 50–99%, ≥100%) of defined target doses. Another three subgroups were specified according to HR at baseline before ivabradine treatment (<75 bpm, 75–84 bpm, ≥85 bpm). In another subgroup of patients, levels of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) were available for each visit. All occurring adverse events (AEs) during the study period had to be documented and assessed by the physician on a specific adverse event reporting form at each patient visit (month 1 and month 4).

Because of the non-interventional design of the study, without a pre-defined statistical null hypothesis, a purely descriptive statistical analysis of the results was performed. Data are presented as mean ± SD for continuous variables and numbers of patients and/or percentages for categorical variables. Baseline and efficacy analysis included all patients with complete age and sex data (full analysis set), and all patients with any documentation were included in the safety and tolerability analysis (safety set). Data were analyzed statistically by an independent statistical institute (Metronomia Clinical Research GmbH, Munich, Germany).

All statistical analyses have been performed by means of the SAS® software system (version 9.3 for Microsoft Windows; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

In total, 1,956 patients with CHF were documented by 694 centers in Germany. The mean study duration was 126 ± 24.4 days. The mean age of the cohort was 67 ± 11.7 years, and 56.9% of the patients were male.

The CHF diagnosis had been known for more than 6 months in 85.4% of the population and for more than 3 months in 14.6%. The etiology of CHF was ischemic in 62.4% of patients, non-ischemic in 31.7%, and both in 5.8%. Nearly all patients (97.9%) presented with at least one concomitant disease, most commonly hypertension (85.1%), hyperlipidemia (60.3%), diabetes mellitus (38.0%), and asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (27.0%; Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristics | Male | Female | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 1,104 (56.9%) | n = 837 (43.1%) | n = 1,941 (100%) | |

| Mean age | 66 ± 11.2 | 68 ± 12.3 | 67 ± 11.7 |

| <65 years | 470 (42.6%) | 280 (33.5%) | 750 (38.6%) |

| 65–80 years | 538 (48.7%) | 429 (51.3%) | 967 (49.8%) |

| >80 years | 96 (8.7%) | 128 (15.3%) | 224 (11.5%) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29 ± 4.6 | 28 ± 5.3 | 29 ± 4.9 |

| Disease duration | 1,031 (100.0%) | 769 (100.0%) | 1,800 (100.0%) |

| >3 months | 161 (15.6%) | 102 (13.3%) | 263 (14.6%) |

| >6 months | 870 (84.4%) | 667 (86.7%) | 1,537 (85.4%) |

| Disease etiology | 1,094 (100.0%) | 825 (100.0%) | 1,919 (100.0%) |

| Ischemic | 740 (67.6%) | 458 (55.5%) | 1,198 (62.4%) |

| Non-ischemic | 281 (25.7%) | 328 (39.8%) | 609 (31.7%) |

| Both | 73 (6.7%) | 39 (4.7%) | 112 (5.8%) |

| LVEF | 982 (100.0%) | 722 (100.0%) | 1,704 (100.0%) |

| ≤35% | 282 (28.7%) | 171 (23.7%) | 453 (26.6%) |

| >35% | 700 (71.3%) | 551 (76.3%) | 1,251 (73.4%) |

| Signs of decompensation | 1,087 (100.0%) | 830 (100.0%) | 1,917 (100.0%) |

| No | 848 (78.0%) | 633 (76.3%) | 1,481 (77.3%) |

| Yes | 239 (22.0%) | 197 (23.7%) | 436 (22.7%) |

| BNP | 214 (100.0%) | 146 (100%) | 360 (100.0%) |

| ≤400 pg/mL | 99 (46.3%) | 67 (45.9%) | 166 (46.1%) |

| >400 pg/mL | 115 (53.7%) | 79 (54.1%) | 194 (53.9%) |

| NYHA class | 1,094 (100.0%) | 827 (100.0%) | 1,921 (100.0%) |

| I | 97 (8.9%) | 87 (10.5%) | 184 (9.6%) |

| II | 576 (52.7%) | 405 (49.0%) | 981 (51.1%) |

| III | 400 (36.6%) | 315 (38.1%) | 715 (37.2%) |

| IV | 21 (1.9%) | 20 (2.4%) | 41 (2.1%) |

| Heart rate, bpm (n = 1,929) | 85 ± 11.7 | 86 ± 11.9 | 85 ± 11.8 |

| ECG | |||

| Sinus rhythm | 922 (83.5%) | 695 (83.0%) | 1,617 (83.3%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 104 (9.4%) | 89 (10.6%) | 193 (9.9%) |

| AV block | 70 (6.3%) | 32 (3.8%) | 102 (5.3%) |

| Pacemaker | 79 (7.2%) | 25 (3.0%) | 104 (5.4%) |

| ICD | 60 (5.4%) | 10 (1.2%) | 70 (3.6%) |

| CRT | 14 (1.3%) | 8 (1.0%) | 22 (1.1%) |

| Concomitant disease | |||

| Any | 1,080 (97.8%) | 821 (98.1%) | 1,901 (97.9%) |

| Hypertension | 932 (84.4%) | 719 (85.9%) | 1,651 (85.1%) |

| Diabetes | 419 (38.0%) | 319 (38.1%) | 738 (38.0%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 707 (64.0%) | 463 (55.3%) | 1,170 (60.3%) |

| Smoking | 286 (25.9%) | 102 (12.2%) | 388 (20.0%) |

| Asthma | 60 (5.4%) | 90 (10.8%) | 150 (7.7%) |

| COPD | 246 (22.3%) | 129 (15.4%) | 375 (19.3%) |

| Depression | 133 (12.0%) | 164 (19.6%) | 297 (15.3%) |

| Apoplex/TIA | 67 (6.1%) | 43 (5.1%) | 110 (5.7%) |

| Hepatic disease | 33 (3.0%) | 14 (1.7%) | 47 (2.4%) |

| Renal insufficiency | 122 (11.1%) | 93 (11.1%) | 215 (11.1%) |

| Malignancy | 31 (2.8%) | 23 (2.7%) | 54 (2.8%) |

| Sleep apnea | 77 (7.0%) | 30 (3.6%) | 107 (5.5%) |

AV atrioventricular, BMI body mass index, BNP brain natriuretic peptide, bpm beats per minute, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CRT cardiac resynchronization therapy, ECG electrocardiography, ICD implantable cardioverter defibrillator, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, NYHA New York Heart Association, TIA transient ischemic attack

As concomitant medication, 77.8% of patients received beta-blockers (32.7% metoprolol, 27.7% bisoprolol, 8.5% nebivolol, and 6.6% carvedilol). 19.9% of patients received at least the beta-blocker target dose, 55.8% at least 50% but less than 100% of the target dose, and 24.3% less than 50% of target dose (Table 2). The mean daily dose was 103.7 mg for metoprolol, 6.2 mg for bisoprolol, 5.4 mg for nebivolol, and 27.7 mg for carvedilol (Table 3).

Table 2.

Beta-blocker therapy at baseline

| Beta-blocker treatment/dosing | Male (n = 1,104) | Female (n = 837) | Total (n = 1,941) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any beta-blocker | 893 (80.9%) | 617 (73.7%) | 1,510 (77.8%) |

| Metoprolol | 387 (35.1%) | 248 (29.6%) | 635 (32.7%) |

| Bisoprolol | 307 (27.8%) | 231 (27.6%) | 538 (27.7%) |

| Nebivolol | 101 (9.1%) | 64 (7.6%) | 165 (8.5%) |

| Carvedilol | 76 (6.9%) | 52 (6.2%) | 128 (6.6%) |

| Other | 48 (4.3%) | 37 (4.4%) | 85 (4.4%) |

| % of target dosea | 768 (100.0%) | 535 (100.0%) | 1,303 (100.0%) |

| <50% | 173 (22.5%) | 144 (26.9%) | 317 (24.3%) |

| 50–99% | 434 (56.5%) | 293 (54.8%) | 727 (55.8%) |

| ≥100% | 161 (21.0%) | 98 (18.3%) | 259 (19.9%) |

aDefined target doses of beta-blockers: metoprolol 190 mg/day, bisoprolol and nebivolol 10 mg/day, carvedilol 100 mg/day

Table 3.

Beta-blocker mean daily doses in relation to target doses and heart rate at baseline

| Beta-blocker dosing | <75 bpm (n = 297) | 75–84 bpm (n = 643) | ≥85 bpm (n = 989) | Total (n = 1,941)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean dose (mg/day) (n = 1,345) | ||||

| Metoprolol | 95.8 ± 49.32 | 105.2 ± 46.20 | 104.4 ± 53.48 | 103.7 ± 50.67 |

| Bisoprolol | 6.9 ± 3.32 | 6.1 ± 2.64 | 6.1 ± 2.65 | 6.2 ± 2.77 |

| Nebivolol | 5.3 ± 2.21 | 5.4 ± 1.75 | 5.5 ± 2.14 | 5.4 ± 1.98 |

| Carvedilol | 29.5 ± 19.79 | 29.5 ± 19.79 | 27.6 ± 16.02 | 27.7 ± 17.04 |

| % of target dosea | 177 (100.0%) | 459 (100.0%) | 658 (100.0%) | 1,303 (100.0%) |

| <50% | 55 (31.1%) | 101 (22.0%) | 160 (24.3%) | 317 (24.3%) |

| 50–99% | 82 (46.3%) | 271 (59.0%) | 367 (55.8%) | 727 (55.8%) |

| ≥100% | 40 (22.6%) | 87 (19.0%) | 131 (19.9%) | 259 (19.9%) |

bpm beats per minute

aDefined target doses of beta-blockers: metoprolol 190 mg/day, bisoprolol and nebivolol 10 mg/day, carvedilol 100 mg/day

bNo statistical imputation of missing values was performed. Patients with missing values for heart rate are included in the “total” column in case of existing documentation of beta-blocker dosing, though they are not considered in the stratified heart rate analysis

Apart from lower mean metoprolol dose in the low HR group, there were no relevant differences in average doses of beta-blockers between patients with low (<75 bpm), moderately elevated (75–84 bpm) and high baseline HR (≥85 bpm). The proportion of patients receiving less than 50% of the beta-blocker target dose was higher and the proportion receiving 50–99% lower in the subgroup with low HR, compared to the subgroups with moderately elevated and high HR (Table 3). Other concomitant medications included ACE inhibitors or ARBs (83%), diuretics (61%), aldosterone antagonists (18%), cardiac glycosides (8%), aspirin (58%), and statins (56%).

Insufficient HR lowering with a beta-blocker was the most common reason for prescribing ivabradine, documented in 74.6% of patients, followed by decreased exercise capacity in 43.6% and intolerance to high doses of beta-blockers in 40.5%. 90.4% of patients started with 5 mg, 9.3% with 2.5 mg, and 0.2% with 7.5 mg twice daily. At visit 3, 44.1% of patients received 5 mg, 52.4% were treated with 7.5 mg, and 3.5% with 2.5 mg ivabradine twice daily. The mean duration of treatment with ivabradine was 123.4 ± 28.1 days. In 4.4% of patients, the study drug was discontinued for different reasons (50.0% patient’s request, 14.1% insufficient efficacy, 20.5% intolerance, 15.4% lack of compliance, and 29.5% other reasons).

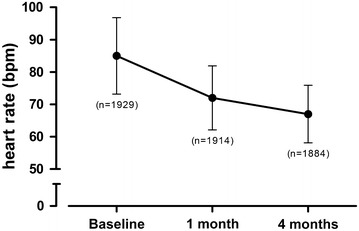

The mean HR of patients was reduced by ivabradine from 85 ± 11.8 bpm at baseline to 72 ± 9.9 bpm after 1 month and 67 ± 8.9 bpm after 4 months at visit 3 (Fig. 1). Relative HR reduction was greater in patients with higher baseline HR. Following the pre-specified response definition of achieving an HR <70 bpm or an absolute reduction of at least 10 bpm at visit 3, 89.0% of all patients had responded to treatment with ivabradine.

Fig. 1.

Mean resting heart rate during treatment with ivabradine from baseline to study end (month 4). Data presented as mean ± standard deviation. bpm beats per minute

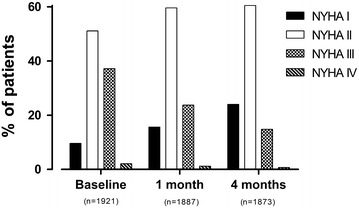

At baseline, NYHA grade I was recorded for 9.6% of patients, NYHA grade II for 51.1%, NYHA grade III for 37.2%, and NYHA grade IV for 2.1%. During the study, the proportion of patients with NYHA III or IV decreased, whereas the proportion of patients with NYHA I and II increased. At visit 3, 24.0% of patients were classified as NYHA I, 60.5% as NYHA II, 14.8% as NYHA III, and 0.7% as NYHA IV (Fig. 2). The change in NYHA class was comparable in all three subgroups defined by baseline HR.

Fig. 2.

Proportion of patients in different NYHA classes from baseline to study end (month 4). NYHA New York Heart Association

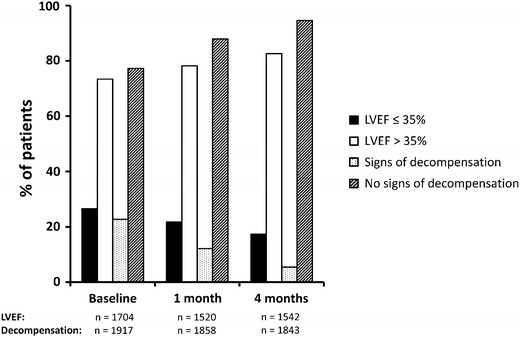

At baseline, 26.6% of patients had an LVEF ≤35%. This proportion declined during the study to 17.4% at visit 3 (Fig. 3). There were no relevant differences either in baseline LVEF or in LVEF changes between subgroups defined by baseline HR.

Fig. 3.

Proportion of patients with LVEF ≤35% or >35% and with/without signs of decompensation from baseline to study end (month 4). LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction

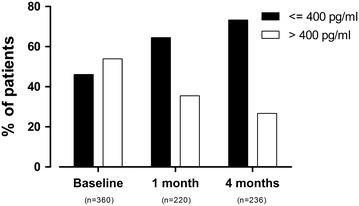

At the initial visit, 22.7% of all patients showed signs of decompensation (edema, dyspnea, etc.). This proportion had decreased to 5.4% at the final visit (Fig. 3). The proportion of patients with signs of decompensation was slightly lower at all three visits in the subgroup with a baseline HR of <75 bpm compared with the two other subgroups with higher baseline HRs. BNP concentration was tracked in 360 patients and exceeded 400 pg/mL in 53.9% at baseline, and in 26.7% at visit 3 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Proportion of patients with BNP levels ≤400 or >400 pg/mL from baseline to study end (month 4). BNP brain natriuretic peptide

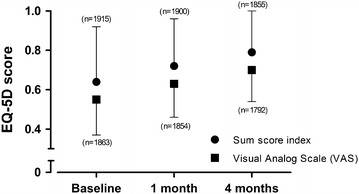

Reductions in signs of decompensation and BNP values were observed in all baseline HR subgroups at the end of the study period. The mean value of the QOL EQ-5D sum score index was 0.64 ± 0.28 at baseline and had improved to 0.79 ± 0.21 at visit 3. A similar improvement was seen in the EQ-5D visual analog scale (Fig. 5), with comparable results in all HR subgroups.

Fig. 5.

Quality of life of patients from baseline to study end (month 4), evaluated by EQ-5D sum score index and visual analog scale. Data presented as mean ± standard deviation. EQ-5D European quality of life-5 dimensions

Overall, 2.9% of patients treated with ivabradine reported at least one adverse event. 0.3% of patients died during the 4-month follow-up period, reflecting a low-risk CHF outpatient cohort. The most common adverse events were cardiac (1.4%), related to the nervous system (0.5%), or to the eye (0.5%). Bradycardia was detected in 0.3% of patients (n = 5) in the whole study cohort and was more common in the group with baseline HR <75 bpm than in the two subgroups with higher baseline HRs (1.0% vs. 0% and 0.2%, respectively).

In the final examination, the physicians rated the effectiveness of ivabradine as very good in 54.9% of patients and good in 41.5%. The proportion of patients for whom effectiveness was rated as very good was higher in the subgroup with a baseline HR of >85 bpm than in the 2 subgroups with lower HR (58.4% vs. 51.5% and 50.2%, respectively). Tolerability was rated by the physicians as very good in 68.2% and good in 31% of patients. The proportion of patients with tolerability rated as very good was lower in the subgroup with baseline HR <75 bpm than in the other subgroups with higher baseline HRs (61.7% vs. 69.1% and 69.4%, respectively).

Detailed evaluation of other pre-defined subgroups showed comparable effectiveness (NYHA classification, signs of decompensation), improvement in QOL, and tolerability, independently of beta-blocker dose (<50%, 50–99%, ≥100% of target dose), LVEF (≤35%, >35%), or age (<65 years, 65–80 years, >80 years), at baseline (subgroup data not shown).

Discussion

Treatment with ivabradine reduced resting HR by 13 ± 10.3 bpm after 1 month (18 ± 12.3 bpm after 4 months). The magnitude of this reduction is similar to that observed in the primary analysis of the SHIFT study [12]. The baseline HR in that trial fell by 15.4 bpm from 79.9 bpm within 28 days. The placebo-corrected difference was 10.9 bpm after 28 days, 9.1 bpm after 1 year, and 8.1 bpm at the end of the study after a median follow-up duration of 23 months. Due to the non-interventional design no placebo group was included in INTENSIFY, so placebo correction of HR reduction was not possible. In SHIFT, an uncorrected HR reduction (15 bpm) of the same magnitude as achieved in INTENSIFY (13 bpm) after 1 month resulted in a significant improvement in patient outcome at the end of follow-up [13].

Not only HR, but also functional class improved. The proportion of patients classified as NYHA I and II increased from 60.7 to 84.5% in 4 months. A positive effect of selective HR reduction on NYHA class is also supported by the SHIFT study, with improvement in NYHA class documented in 28% of patients on ivabradine treatment [12].

The changes in NYHA class reported for the patients in INTENSIFY represent a considerable stabilization of CHF in a short period of time. This is also reflected by an improvement of other clinical parameters after 4 months: the proportion of patients with an LVEF ≤35% decreased from 26.6 to 17.4%, of patients with signs of decompensation declined from 22.7 to 5.4%, and of patients with a BNP level ≥400 ng/mL decreased from 53.9 to 26.7%.

The stabilizing effect on CHF induced by ivabradine through reduction of HR is supported by a study recently published by Sargento et al. [14], showing that a significant 44.5% decrease in N-terminal pro-BNP versus baseline and improvement in NYHA class achieved with 3-month ivabradine treatment in ambulatory CHF patients on optimized standard therapy closely correlated with the degree of HR reduction and baseline HR. The reduction in symptoms seen in INTENSIFY is also in line with the data of Volterrani et al. [15] demonstrating greater effects on exercise capacity and NYHA status in CHF patients (NYHA II–III) for ivabradine/carvedilol combination therapy or ivabradine monotherapy compared with carvedilol monotherapy during a 3-month study period. Also, QOL of patients was significantly improved with ivabradine and combination treatment versus baseline, while no effect was shown for carvedilol monotherapy.

The hidden symptomatic “benefit reserve” in the INTENSIFY cohort before the start of ivabradine treatment could obviously not be targeted solely with beta-blockers, which most patients received. As CHF diagnosis was known for more than 6 months in 85.4% of patients, it is justified to consider that beta-blocker up-titration has been completed in that period of time. It should be noted that there was no intensification of beta-blocker treatment or other CHF therapy during the study period that could have contributed to the symptomatic improvement. In contrast, even a tendency to discontinuation or to reduction in existing beta-blocker therapy could be observed after 4 months. The results of our study emphasize that there was room for further symptomatic improvement in these patients, despite beta-blocker treatment in line with current guidelines the dosage of which can be considered to be optimized at study inclusion. Interestingly, at baseline, patients with higher HRs tend to be treated with considerably higher mean doses of metoprolol, which was the most widely used beta-blocking agent in this patient cohort. There are other studies confirming that HR reduction is not consistently related to beta-blocker dose [16]. For example, Franke et al. [8] analyzed 443 CHF patients with an LVEF ≤35% and NYHA class II–IV. After careful up-titration of beta-blocker treatment, 29% of patients reached the recommended target dose and 69% at least half of it. Despite this optimized beta-blockade in clinical practice, 53% of patients remained on an HR ≥75 bpm [8]. There is now also growing evidence from recent clinical studies [17, 18] and also meta-analyses of beta-blocker studies [19, 20] that treatment in CHF patients should not be strictly focused on achieving certain beta-blocker target dosages, which seem not to be related to clinical outcomes, but rather should concentrate on the cumulative HR reduction that can be achieved by different rate-reducing agents in the therapeutic regimen. The magnitude of HR reduction was closely correlated with prognosis in the abovementioned studies.

HR reduction by ivabradine also improved QOL considerably in the INTENSIFY study, as reflected by the observed increase in EQ-5D parameters. This finding is also in line with a secondary analysis from the SHIFT trial, showing that HR reduction by ivabradine was associated with a significant increase in QOL [21]. There was clear relationship between the magnitude of HR reduction and improvement in QOL, and also an inverse relation between QOL measures and incidence of the primary composite end point of the trial. The QOL improvement in our study is of considerable clinical relevance. The result lies well within the range that can be achieved by percutaneous coronary intervention treatment in symptomatic patients with coronary artery disease (roughly 0.2 index points on the EQ-5D), which is an established treatment of proven efficacy in these patients [22]. Ivabradine produced similar improvements in a large patient cohort with symptomatic coronary artery disease in clinical practice [23].

For CHF patients on the other hand, an extensive meta-analysis failed to show a significant improvement in QOL for beta-blocker treatment, irrespective of proven mortality reduction [24]. These results are supported by a study by Riccioni et al. [25] and also a head-to-head comparison trial of ivabradine, carvedilol, or combination treatment [15], demonstrating greater improvement in QOL with ivabradine alone or with combination therapy with carvedilol compared with carvedilol alone. In this head-to-head study, Volterrani et al. [15] found no significant effect of carvedilol monotherapy on QOL after 3 months of treatment versus baseline. The positive effect of ivabradine on QOL of CHF patients also needs to be considered in the context that such data is, to our knowledge, largely missing for other heart failure standard medications (ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists). No improvement in QOL could be demonstrated for beta-blockers, and only modest effects or delay of progressive worsening of QOL for ACE inhibitors [26]. No effect on symptom status or QOL measures was seen in a randomized trial with eplerenone compared with placebo in NYHA II/III CHF patients [27]. Keeping in mind the growing relevance of QOL improvement as an important therapeutic goal in heart failure therapy, ivabradine seems to provide a specific additional benefit here compared with other prognostic standard medications.

Taken together, the results from INTENSIFY add to this evidence in demonstrating additional improvement in symptoms and in QOL in combination with standard beta-blocker therapy.

Study Limitations

An important limitation of this trial is its open-label, observational, non-interventional design with no placebo group, which may lead to an overestimation of the treatment effects. On the other hand, the efficacy of ivabradine in combination with beta-blocker has been consistently proven in a large randomized clinical trial with CHF patients [12]. Moreover, the open study design allows evaluation of treatment effects under conditions of routine clinical practice, while in controlled studies strict inclusion criteria usually restrict access of broader patient populations with, for example, multiple comorbidities and risk factors.

Another limitation is the relatively short study duration of 4 months, which is nevertheless sufficient to evaluate symptom reduction and QOL in CHF patients, as already demonstrated in other studies [14, 15, 24]. The high resting HR at baseline can also lead to an overestimation of the treatment benefit, as the ivabradine effects are more pronounced in patients with a high HR, due to its use-dependent mechanism of action. But with only slightly more than half of the patients being up-titrated to the recommended maintenance dose of ivabradine, treatment effects may also be underestimated.

Due to the non-interventional design, an underestimation of adverse events cannot be fully excluded, as they were not specifically looked for and were evaluated only in the form of an open interview at each visit. But taking into account favorable safety results from controlled clinical trials, ivabradine in combination with beta-blockers and other frequently prescribed drugs appears to be well tolerated in CHF patients [12, 15].

Conclusion

In this prospective open-label study, ivabradine was effective in reducing HR and symptoms in CHF patients over a period of 4 months. There was a marked reduction in the proportion of patients showing signs of decompensation and a LVEF ≤35% from baseline to study end. A shift from higher to lower NYHA classes could also be demonstrated. Furthermore, ivabradine reduced BNP levels and improved QOL in this large patient cohort. These benefits were accompanied by good general tolerability. The results of our study emphasize that there is still potential for further symptom reduction and corresponding QOL improvement in CHF patients, despite optimized beta-blocker treatment in line with current guideline recommendations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Sponsorship and article processing charges for this study were funded by Servier Deutschland GmbH, Munich, Germany. All named authors meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published. The authors thank Dr Angelika Bischoff for assistance in the preparation of the manuscript. Subsets of these data were presented during poster sessions at the 2013 and 2014 European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Congresses and at meetings of the German Society of Cardiology in 2013 and 2014.

Conflict of interest

Prof Zugck has received speaker honoraria for different lectures and research grants from Servier. Dr Martinka is an employee of Servier Deutschland GmbH (Medical Affairs). Dr Stöckl is an employee of Servier Deutschland GmbH (Medical Affairs).

Compliance with ethics guidelines

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 and 2008. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Footnotes

Trial registration: Controlled-trials.com, number ISRCTN12600624.

References

- 1.Pocock SJ, Wang D, Pfeffer MA, et al. Predictors of mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:65–75. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Böhm M, Swedberg K, Komajda M, et al. Heart rate as a risk factor in chronic heart failure (SHIFT): the association between heart rate and outcomes in a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:886–894. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61259-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fox K, Ford I, Steg PG, et al. Heart rate as a prognostic risk factor in patients with coronary artery disease and left-ventricular systolic dysfunction (BEAUTIFUL): a subgroup analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:817–821. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61171-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reil JC, Custodis F, Swedberg K, et al. Heart rate reduction in cardiovascular disease and therapy. Clin Res Cardiol. 2011;100(1):11–19. doi: 10.1007/s00392-010-0207-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lonn EM, Rambihar S, Gao P, et al. Heart rate is associated with increased risk of major cardiovascular events, cardiovascular and all-cause death in patients with stable chronic cardiovascular disease: an analysis of ONTARGET/TRANSCEND. Clin Res Cardiol. 2014;103:149–159. doi: 10.1007/s00392-013-0644-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foody JM, Farrell MH, Krumholz HM. Beta-blocker therapy in heart failure: scientific review. JAMA. 2002;287(7):883–889. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.7.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McMurray J, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1787–1847. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franke J, Wolter JS, Meme L, et al. Optimization of pharmacotherapy in chronic heart failure: is heart rate adequately addressed? Clin Res Cardiol. 2013;102(1):23–31. doi: 10.1007/s00392-012-0489-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maggioni AP, Anker SD, Dahlström U, et al. Are hospitalized or ambulatory patients with heart failure treated in accordance with European Society of Cardiology guidelines? Evidence from 12,440 patients of the ESC heart failure long-term registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15(10):1173–1184. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tardif JC, Ford I, Tendera M, et al. Efficacy of ivabradine, a new selective I(f) inhibitor, compared with atenolol in patients with chronic stable angina. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(23):2529–2536. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruzyllo W, Tendera M, Ford I, Fox KM. Antianginal efficacy and safety of ivabradine compared with amlodipine in patients with stable effort angina pectoris: a 3-month randomized, double-blind, multicenter, non-inferiority study. Drugs. 2007;67(3):393–405. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200767030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swedberg K, Komajda M, Böhm M, et al. Ivabradine and outcomes in chronic heart failure (SHIFT): a randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet. 2010;376:875–885. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61198-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Böhm M, Borer J, Ford I, et al. Heart rate at baseline influences the effect of ivabradine on cardiovascular outcomes in chronic heart failure: analyses from the SHIFT study. Clin Res Cardiol. 2013;102(1):11–22. doi: 10.1007/s00392-012-0467-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sargento L, Satendra M, Longo S, et al. Early NT-porBNP decrease with ivabradine in ambulatory patients with systolic heart failure. Clin Cardiol. 2013;36(11):677–682. doi: 10.1002/clc.22183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Volterrani M, Cice G, Caminiti G, et al. Effect of carvedilol, ivabradine or their combination on exercise capacity in patients with heart failure (the CARVIVA HF trial) Int J Cardiol. 2011;151(2):218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.06.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wikstrand J, Hjalmarson A, Waagstein F, et al. Dose of metoprolol CR/XL and clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure. JACC. 2002;40(3):491–498. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)01970-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swedberg K, Komajda M, Böhm M, et al. Effects on outcomes of heart rate reduction by ivabradine in patients with congestive heart failure: is there an influence of beta-blocker dose? Findings from the SHIFT (systolic heart failure treatment with the I(f) inhibitor ivabradine trial) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(22):1938–1945. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cullington D, Goode KM, Clark AL, et al. Heart rate achieved or beta-blocker dose in patients with chronic heart failure: which is the better target? Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14(7):737–747. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flannery G, Gehrig-Mills R, Billah B, et al. Analysis of randomized controlled trials on the effect of magnitude of heart rate reduction on clinical outcomes in patients with systolic chronic heart failure receiving beta-blockers. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101(6):865–869. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McAlister FA, Wiebe N, Ezekowitz JA, et al. Meta-analysis: beta-blocker dose, heart rate reduction, and death in patients with heart failure. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:784–794. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-11-200906020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ekman I, Chassany O, Komajda M, et al. Heart rate reduction with ivabradine and health related quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure: results from the SHIFT study. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2395–2404. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denvir MA, Lee AJ, Rysdale J, et al. Influence of socioeconomic status on clinical outcomes and quality of life after percutaneous coronary intervention. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:1085–1088. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.044255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Werdan K, Ebelt H, Nuding S, et al. Ivabradine in combination with beta-blocker improves symptoms and quality of life in patients with stable angina pectoris: results from the ADDITIONS study. Clin Res Cardiol. 2012;101(5):365–373. doi: 10.1007/s00392-011-0402-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dobre D, van Jaarsveld C, deJongste M, et al. The effect of beta-blocker therapy on quality of life in heart failure patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(2):152–159. doi: 10.1002/pds.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riccioni G, Masciocco L, Benvenuto A, et al. Ivabradine improves quality of life in subjects with chronic heart failure compared to treatment with β-blockers: results of a multicentric observational APULIA study. Pharmacology. 2013;92(5–6):276–280. doi: 10.1159/000355169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dobre D, de Jongste MJ, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM, et al. The enigma of quality of life in patients with heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2008;125(3):407–409. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Udelson JE, Feldman AM, Greenberg B, et al. Randomized, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled study evaluating the effect of aldosterone antagonism with eplerenone on ventricular remodeling in patients with mild-to-moderate heart failure and left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3(3):347–353. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.906909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.