Summary

Phosphate concentration is tightly regulated at the cellular and organismal levels. The first metazoan phosphate exporter, XPR1, was recently identified, but its in vivo function remains unknown. In a genetic screen, we identified a mutation in a zebrafish ortholog of human XPR1, xpr1b. xpr1b mutants lack microglia, the specialized macrophages that reside in the brain, and also displayed an osteopetrotic phenotype characteristic of defects in osteoclast function. Transgenic expression studies indicated that xpr1b acts autonomously in developing macrophages. xpr1b mutants displayed no gross developmental defects that may arise from phosphate imbalance. We constructed a targeted mutation of xpr1a, a duplicate of xpr1b in the zebrafish genome, to determine if Xpr1a and Xpr1b have redundant functions. Single mutants for xpr1a were viable, and double mutants for xpr1b;xpr1a were similar to xpr1b single mutants. Our genetic analysis reveals a specific role for the phosphate exporter Xpr1 in differentiation of tissue macrophages.

Introduction

Macrophages are a highly diverse population of immune cells present in virtually all tissues of vertebrates. Macrophages are important not only for phagocytosis and immune system regulation, but also tissue homeostasis and development (Davies et al., 2013, Wynn et al., 2013). For example, besides their well-known role in the immune defense of the central nervous system, microglial cells (brain-resident macrophages) are also important for clearance of cellular debris and regulating neuronal connectivity (Paolicelli et al., 2011, Peri and Nusslein-Volhard, 2008, Ransohoff and Cardona, 2010) (Schafer et al., 2012). Similarly, osteoclasts (bone-resorbing macrophages) are essential for correct bone development, bone remodelling in adults and mineral homeostasis at the organismal level. Mice that are devoid of osteoclasts develop osteopetrosis, a condition characterized by abnormal bone structure and altered hematopoiesis (Begg et al., 1993, Pollard, 1997). Despite the importance of tissue macrophages, the mechanisms that control the development and dedicated functions of tissue macrophages are not well understood.

Inorganic phosphate (Pi) is a crucial ion necessary for bone mineralization and diverse cellular activities, because it forms an integral part of membrane phospholipids, nucleic acids and ATP. Furthermore, phosphate has an important role in many signalling pathways involving kinases and phosphatases (Biber et al., 2013, Forster et al., 2013). SLC34 and SLC20 are transporters that define two classes of molecules that import phosphate into cells. SLC34 family members are expressed and localized in the apical membrane of enterocytes (NPT2b/SLC34A2) and epithelial cells of the proximal tubule in the kidney (NPT2a/SLC34A1). Members of SLC20 family are ubiquitously expressed and are considered to be suppliers of phosphate for cellular metabolism and bone mineralization (Biber et al., 2013, Forster et al., 2013). Although the existence of a dedicated phosphate exporter has long been hypothesized, the first metazoan phosphate exporter, XPR1, was only recently identified (Giovannini et al., 2013).

XPR1 is a highly conserved multipass transmembrane protein originally identified as a receptor for xenotropic and polytropic murine retroviruses (Battini et al., 1999, Tailor et al., 1999, Yang et al., 1999). XPR1 possesses two characteristic protein domains, SPX (named after the proteins Syg1, Pho81 and XPR1) and EXS (named after the proteins ERD, XPR1 and Syg1). The SPX domain is conserved throughout evolution and present in many yeast and plant proteins involved in phosphate homeostasis (Secco et al., 2012a, Secco et al., 2012b). The SPX domain of XPR1 is dispensable for phosphate export and viral infection (Giovannini et al., 2013, Wege and Poirier, 2014). Because overexpression of XPR1 or of a truncated form containing the SPX domain leads to an increase in intracellular cAMP levels (Vaughan et al., 2012) and because XPR1 interacts with the Gβ subunit of the G-protein trimer, this protein has also been classified as an atypical G-protein coupled receptor (Vaughan et al., 2012). Despite the evidence for a role in phosphate export and its potential role as a transmembrane receptor, XPR1 may also have other activities and there is little understanding of its function in vivo.

xpr1a and xpr1b are the zebrafish orthologs of XPR1. In this study, we show that the phosphate exporter xpr1b acts specifically in macrophages to promote the differentiation and establishment of several tissue-resident macrophage populations. xpr1b mutants lack microglia and also have a reduction in the number and complexity of Langerhans cells. Furthermore, we demonstrate that xpr1b mutants have profound defects in bone architecture characteristic of osteoclast disruption. Additionally, our genetic analysis of xpr1a, the only additional zebrafish paralog of xpr1b, showed that xpr1a mutants had no defects in microglia formation and that xpr1b; xpr1a double mutants are phenotypically similar to xpr1b mutants. Thus, our genetic analysis provides evidence that the macrophage lineage is particularly sensitive to alterations in Xpr1 function.

Results

Genetic screen identifies xpr1b as new regulator of macrophage development

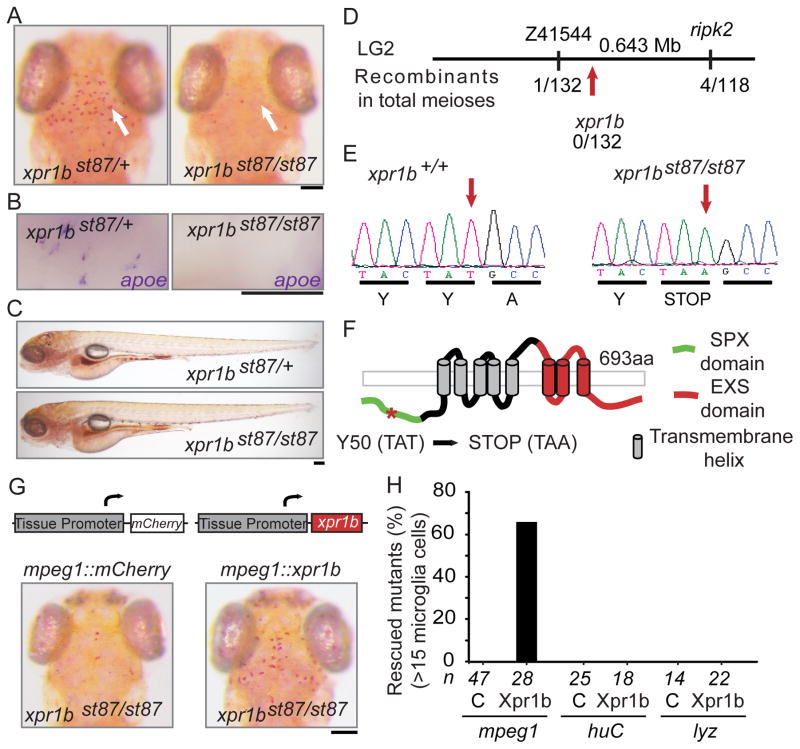

We conducted a genetic screen for ENU-induced mutations causing abnormalities in microglia, using the vital dye neutral red, a previously reported marker of macrophages and microglia in zebrafish (Herbomel et al., 2001). This screen identified xpr1bst87 as a mutation that severely reduced the number of neutral red labelled microglia (Figures 1A). At 5 days post fertilization (dpf), homozygous xpr1b st87 mutant larvae lacked expression of the microglial marker apolipoproteinE (apoe) (Herbomel et al., 2001, Peri and Nusslein-Volhard, 2008) (Figure 1B), but were otherwise morphologically indistinguishable from wildtype and heterozygous siblings (Figure 1C). High-resolution genetic mapping placed the xpr1bst87 mutation in a 0.64 Mb region of linkage group 2 (LG2) that contains the xpr1b gene (Figure 1D). Xpr1b shares 79% identity and 87% similarity with the human XPR1 protein, which was originally identified as a retroviral receptor (Battini et al., 1999, Tailor et al., 1999, Yang et al., 1999) and has been recently characterized as an inorganic phosphate exporter (Giovannini et al., 2013). Sequence analysis of xpr1bst87 mutants identified a T to A transversion that introduces a premature stop codon near the 5′ end of xpr1b open reading frame (Figure 1E). All xpr1bst87 mutants analysed were homozygous for this lesion (n = 80). To obtain additional evidence that xpr1b is disrupted by the xpr1bst87 mutation, we rescued the mutants by injecting synthetic mRNA encoding wildtype xpr1b. Injection of 200 pg of xpr1b mRNA into xpr1bst87 mutants rescued the microglia phenotype (Figure S1A). Furthermore, we also generated mutations in xpr1b using sequence specific TALE-nucleases (Sanjana et al., 2012, Christian et al., 2010). We isolated two frameshift mutations, namely xpr1bst89 and xpr1bst90. Both mutations failed to complement xpr1bst87, and homozygous xpr1bst89 and xpr1bst90 mutants also lacked microglial cells (Figure S1B). Taken together, the mapping, analysis of two other mutant alleles, and rescue experiments demonstrate that xpr1bst87 is a loss-of-function mutation in the xpr1b gene.

Figure 1. xpr1b is required autonomously in macrophages for microglia development.

(A) 5 dpf zebrafish larvae were stained with the microglial vital marker neutral red (Herbomel et al 2001). Left panel shows the dorsal view of xpr1b heterozygous larva with microglia (arrow) in the optic tectum; (B) Whole-mount in situ hybridization at 5 dpf reveals the expression of the microglial marker apoe in xpr1b heterozygous but not in xpr1b mutants. (C) Lateral view of neutral red stained heterozygous and homozygous mutants shows normal whole-animal morphologies at 5 dpf. (D) Schematic representation of the st87 locus. (E) Chromatogram depicts the lesion (arrow) in the coding sequence of xpr1b. (F) Graphical representation of the domain structure of Xpr1 and the location of the st87 lesion (asterick). (G) Diagram represents the transgenic constructs driving the expression of mcherry reporter or wildtype xpr1b under the control of macrophage (mpeg1), neurons (huC) or neutrophils (lyz) tissue promoters. Below are representative images of neutral red stained xpr1b mutant fish expressing mcherry (left) or xpr1b (right) under the macrophage lineage specific promoter. Microglia are present only when xpr1b is expressed under the mpeg1 promoter. (H) Graph shows the percentage of mutants rescued by different tissue specific promoters. The number of embryos analysed for each condition, mcherry (C) or xpr1b, are shown below. Scale bar = 50 μm. See also Figure S1.

xpr1b is required autonomously in macrophages for microglia development

To test whether Xpr1b is required autonomously in the macrophage lineage or in other cell types, we employed a transgenic rescue strategy. Coding sequences for xpr1b or the reporter mCherry were expressed under the control of cell specific regulatory elements that drive expression in neurons (elavl3/huC), neutrophils (lyz) or macrophages (mpeg1) as previously described (Shiau et al., 2013). Transient Tol2-mediated expression of the wildtype xpr1b gene under the control of mpeg1 regulatory elements rescued microglia (>15 cells/embryo) in 67% of xpr1b mutants (n = 28). There was no significant rescue of microglia when xpr1b gene was expressed in other cell types or by expression of the mCherry coding sequence in any cell type (Figures 1G and 1H). These data indicate that xpr1b is required in the macrophage lineage for normal microglia development.

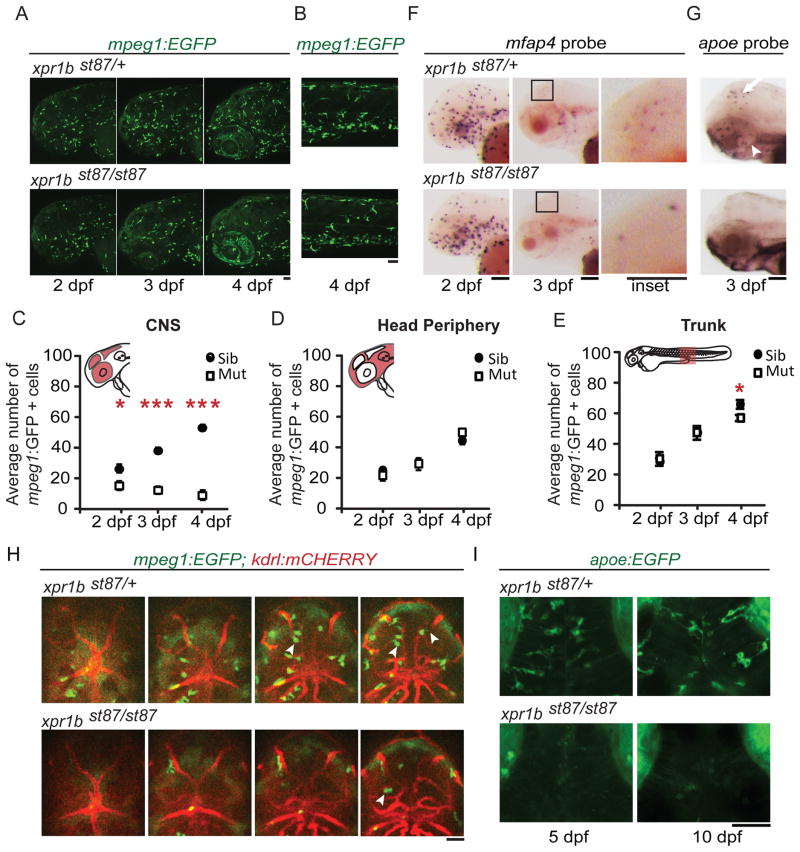

Brain colonization of microglia is disrupted in xpr1b mutants

Microglia derive from a subset of primitive macrophages that migrate from the yolk sac into the brain, where they differentiate as microglia during embryogenesis (Ginhoux et al., 2010, Herbomel et al., 2001). To define the role of xpr1b during microglia development, we analyzed the macrophage lineage from the formation of primitive macrophages to differentiation of microglia (1–5 dpf). The markers mfap4 [microfibrillar-associated protein 4 (Zakrzewska et al., 2010)] and mpeg1:EGFP [macrophage expressed gene 1 (Ellett et al., 2011)] are expressed in macrophages and in microglia after they begin to differentiate at 60 hpf. Using these markers, we detected no difference in the number or distribution of macrophages up to 24 hpf (AMM, unpublished data). At 2 dpf, however, the number of mpeg1:EGFP positive cells within the CNS (eye, midbrain and hindbrain) was slightly but significantly reduced in xpr1b mutants (Figures 2A and 2C). This reduction became more apparent as development progressed, so that wildtype larvae had approximately 50 mpeg1:EGFP positive microglia/per field of view at 4 dpf, compared to only about 14 in xpr1b mutants (Figures 2A and 2C).

Figure 2. xpr1b is required for brain colonization by microglial progenitors.

(A and B) Representative z-projections of mpeg1:EGFP labelled cells at 2–4 dpf in the head (A) or 4 dpf in the trunk (B), in heterozygous larvae (top panel) or xpr1b mutants. (C, D and E) Graphs show the average number of mpeg1:EGFP positive cells in the highlighted region of fish schematics: CNS (eye, midbrain and hindbrain) (C), head periphery (D) and trunk (E). xpr1b mutants show a reduction in the average number of macrophages in the CNS region starting at 2dpf. Error bars show s.e.m. Statistical significance was determined by paired two-tailed Student’s test *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001 (2 dpf, mutants n =7, siblings n = 16; 3 dpf, mutants n = 6, siblings n = 16; 4d pf, mutants n = 4, siblings n = 9). (F) Whole mount in situ hybridization at 2 and 3 dpf, shows mfap4+ macrophages in the brain of wildtype heterozygous (top panel) larva but not in xpr1b mutants (lower panel). (G) Whole mount in situ hybridization at 3dpf, shows apoe+ microglia in the brain of wildtype heterozygous (top panel) larva but not in xpr1b mutants (lower panel). (H) Serial single-plane images of stable transgenic fish expressing the macrophage marker mpeg1:EGFP and the vasculature marker kdrl:mCHERRYCAAX. Images show extensive penetration of macrophages into the brain of wildtype heterozygous fish (top panels) and only a few in xpr1b mutants (lower panels) (arrowheads indicate macrophages). (I) Z-stack images of stable transgenic fish expressing the microglia marker apoe:EGFP. Images show microglia cells with processes in wildtype fish at 5 and 10 dpf (top panels) whereas no microglia cells are present in xpr1b mutants, even at 10 dpf (right panel). Scale bar = 50 μm. See also Figure S2–S3 and Movies S1–S4

We sought to determine whether the reduction in microglia in xpr1b mutants reflected an overall reduction of the precursor macrophage population. In contrast to microglia, there was no significant reduction in the number of mpeg1:EGFP labelled macrophages in non-CNS locations of the head of xpr1b mutants at 2 dpf, 3 dpf, or 4 dpf (Figures 2A and 2D). Similarly, the number and distribution of mpeg1:EGFP labelled macrophages in the trunk region of mutant larvae remained comparable to wildtype up to 4 dpf, albeit a slight reduction was detected in the mutants (Figures 2B and 2E). In vivo time-lapse imaging of mpeg1:EGFP labelled cells in the head showed that mutant macrophages divide at a rate similar to their wildtype counterparts (Figure S2, Movies SV1 and SV2), suggesting that reduced proliferation may not explain the decrease in the mutants. In addition, our in vivo time-lapse imaging analysis and TUNEL staining experiments showed no indication of higher cell death in mutant macrophages (Movies SV1 and SV2). Because the number of mpeg1:EGFP expressing cells is reduced in the CNS of xpr1b mutants at 2 dpf, prior to the differentiation of microglia in the wildtype, and that no significant reduction in peripheral macrophages was found at this stage, the foregoing analyses suggest that migration and invasion of the brain by microglial precursors is reduced in xpr1b mutants.

The non-canonical NOD-like receptor nlrc3-like was recently reported to suppress inflammatory activation of primitive macrophages and to enable their migration and differentiation as microglia (Shiau et al., 2013). We sought out to determine if the migratory defect present in xpr1b mutants is related to that of nlrc3-like mutants. Similarly to nlrc3-like mutants, xpr1b mutants had higher than normal neutrophil numbers in the head. xpr1b mutants, however, did not have an increase of circulating neutrophils or increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines, which are characteristic of nlrc3-like mutants.(Figure S3). Furthermore, Nlrc3-like expression did not rescue the microglia defect in xpr1b mutants, nor did Xpr1b expression rescue nlrc3-like mutants (Figure S3). These results provide evidence that xpr1b and nlrc3-like function in distinct genetic pathways that are essential for microglia formation in zebrafish.

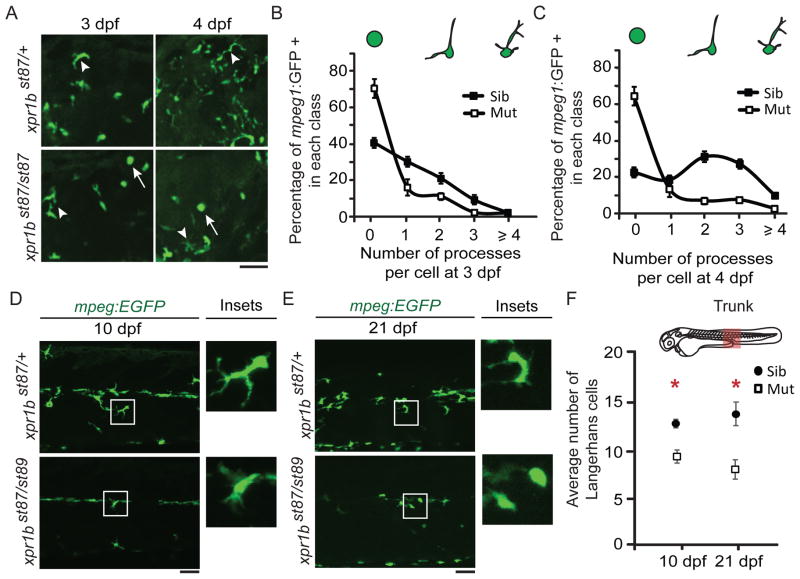

xpr1b mutant macrophages have abnormal morphology and do not differentiate as microglia

Although the number of microglial progenitors (macrophages located in the CNS) is reduced in xpr1b mutants, time-lapse imaging revealed that some mpeg1:EGFP expressing cells are able to enter the brain parenchyma (Figure 2H, Movies SV3 and SV4). However, expression of the microglia marker apoe (Herbomel et al., 2001), was not observed in mutants at any stage examined (2.5d dpf, 5 dpf and 10 dpf) (Figures 2G–I). Furthermore, the morphology of mpeg1:EGFP-labeled cells was abnormal in xpr1b mutants. In xpr1b mutants at 3 dpf, about 72% of mpeg1:EGFP-labeled cells in the midbrain and hindbrain had no processes, compared to only 42% in wildtype (Figure 3A–C). At 4 dpf, the morphological difference is even more pronounced, with the majority of cells having 2 or more processes in wildtype, whereas more than 60% of cells in the mutant had no processes (Figures 3A–C). These data indicate that xpr1b is required both for microglial progenitors to colonize the brain and also for these cells to differentiate into apoe-expressing, process-bearing microglia.

Figure 3. xpr1b is required for differentiation of microglia and Langerhans cells.

(A) Representative Z-stack images of the head region of stable mpeg1:EGFP transgenic fish at 3 and 4 dpf. In wildtype heterozygous fish macrophages display an array of morphologies from rounded (arrows) to multiple process bearing cells (arrowhead). In contrast, xpr1b mutants display a more restricted array of morphologies. (B and C) Graphs show the percentage of mpeg1:EGFP positive cells that contain 0, 1, 2, 3 or 4 or more processes at 3 dpf (B) or 4 dpf (C) (3 dpf siblings n = 6; mutants n = 5. 4 dpf siblings n = 4; mutants n = 4). (D and E) Representative Z-stacks of the superficial layers of the trunk of wildtype heterozygous and xpr1b mutant fish at 10 (D) and 21 dpf (E). Insets show representative images of Langerhans cells. (F) Graph shows the average number of Langerhans cells in the field of view in the area of the trunk highlighted in the schematics. Error bars show s.e.m. *P ≤ 0.05, using paired two-tailed Student’s t test (10 dpf siblings n = 5; mutants n = 6. 21dpf siblings n = 7; mutants n = 6). Scale bar = 50 μm. See also Figure S4.

Number of Langerhans cells and their complexity is affected in xpr1b mutants

The requirement of xpr1b for the differentiation of primitive macrophages into microglia cells raised the possibility of this gene having a broader role in the differentiation of other specialized tissue macrophages. To examine this possibility, we analysed Langerhans cells, a population of tissue macrophages that reside in the skin. In wildtype, the mepg1:EGFP transgene labelled cells in the skin that displayed many processes at 10 dpf and 21 dpf, consistent with the previously characterized location and morphology of Langerhans cells at these stages (Figures 3D and 3E) (Svahn et al., 2013). In xpr1b mutants, the number of these mepg1:EGFP positive cells was reduced in the skin (Figure 3F), and the cells that were present had fewer processes (Figure S4). These results indicate that xpr1b is also essential for the normal development of Langerhans cells.

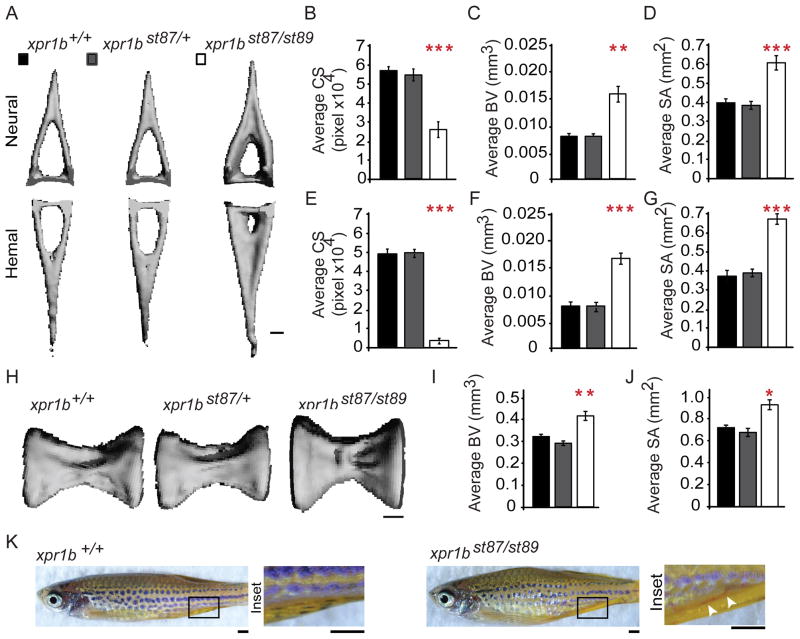

xpr1b mutants have impaired bone remodelling that is indicative of osteoclast defects

xpr1b mutants can survive to adulthood, although in reduced numbers compared to their siblings (Figure S5A). Furthermore, xpr1b mutants were also smaller than their siblings at 50 dpf, but were able to continue growing (Figure S5B). Interestingly, some xpr1b mutant adults (2/9) displayed severe abnormalities in their body axis. In light of such severe malformations and reduced viability, we sought to determine whether Xpr1 is important for bone architecture. Micro-computerized tomography (μCT) imaging revealed pronounced vertebral abnormalities in the xpr1b mutants. Notably, the 14th and 16th hemal canals were about 10% of the wildtype size (Figures 4A and 4E, Figure S5). The neural canals of the same vertebrae were less affected in the mutants, but still only about 40% the size of wildtype (Figures 4A and 4B, Figure S5). Likewise, xpr1b mutants had greater bone volumes and surface areas than their siblings (Figures 4A, 4C, 4D, 4F and 4G, Figure S5). These results suggest that in xpr1b mutants bone resorption is impaired. We extended our analysis to determine if the vertebral bodies of the 14th and 16th vertebrae also displayed features consistent with a defect in bone resorption. As with the vertebral arches, we found that xpr1b mutant vertebrae had greater bone volumes (Figures 4H and 4I) and surface areas (Figures 4H and 4J) than their siblings. These results are also consistent with a generalized defect in bone resorption in xpr1b mutants. Osteoclasts are cells derived from macrophages that have the primary function of resorbing bone during remodelling, and mutations that affect osteoclasts number and function disrupt bone remodelling (Segovia-Silvestre et al., 2009). Indeed the zebrafish panther mutant, which has a mutation in the macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (csf1ra), has a reduced number of osteoclasts and narrower neural and hemal canals due to increased bone mass (Chatani et al., 2011). Interestingly, csfr1a mutants also had impaired blood vessel formation, with the formation of an ectopic blood vessel that bypassed the occluded hemal canals. xpr1b mutants also had blood vessels in their ventral regions that were not observed in their siblings (Figure 4K). The parallels between xpr1b and csfr1a mutant phenotypes suggest that the skeletal defects in xpr1b mutants arise from a reduction of osteoclast number or function. Taken together, these phenotypic studies provide evidence that Xpr1 is essential for the development and function of diverse tissue macrophage populations, including microglia, Langerhans cells, and osteoclasts.

Figure 4. xpr1b is required for normal skeletal development.

(A) μCT-derived volumetric reconstructions of the neural (top) and hemal (bottom) 14th vertebral arches from a representative wild type (n=6), heterozygous (n=7) and mutant (n=6) fish. xpr1b mutant fish have excess bone on the inner surface of the arch compared to wild type and heterozygous fish, reducing the overall aperture of the canal. Scale bar = 100 μm. (B–G) Graphs showing quantified values for the vertebral arch defect depicted in (A). xpr1b mutant fish exhibit significant reductions in canal aperture (B, E) with a concomitant increase in the total amount of bone as measured by bone volume (BV; C, F) and surface area (SA; D, G). (H) Volumetric reconstructions of the 14th vertebral bodies from a representative wild type, heterozygous and mutant fish. xpr1b mutant vertebral bodies appear larger than their wild type and heterozygous siblings. Scale bar = 100 μm. (I, J) Graphs depicting the significant increase in the total amount of bone present in mutant vertebrae as measured by BV (I) and SA (J). Error bars show s.e.m. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired, two-tailed t tests. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.005, *** P < 5×10−4. (K) Lateral view of wildtype (left panel) and xpr1b mutant (right panel) adult fish. Inset shows the presence of an ectopic vessel in xpr1b mutants (right panel, arrowheads) that is absent in wildtype fish. See also Figure S5.

xpr1a, the only zebrafish paralog of xpr1b, is not required for microglia or normal embryonic development

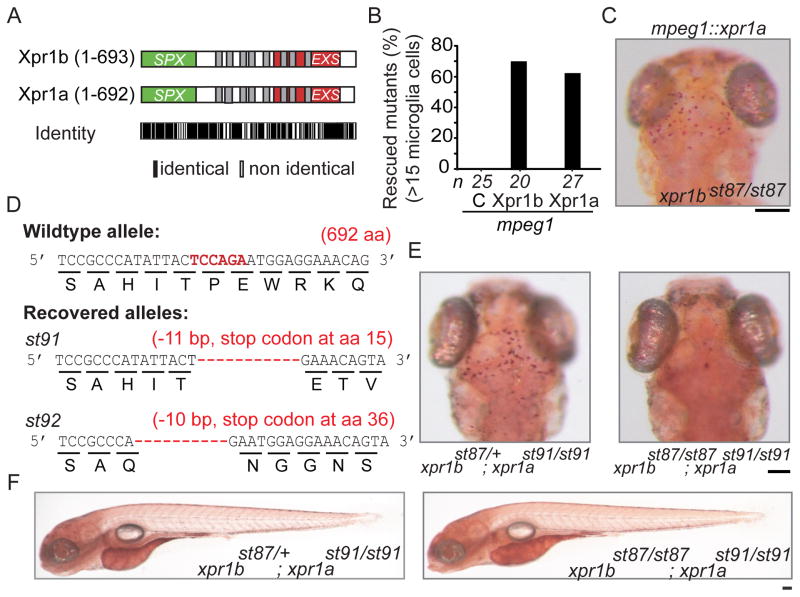

The zebrafish genome contains a second XPR1 homolog, xpr1a. Xpr1a, shares 80% identity and 89% similarity with human XPR1 and 80% identity and 87% similarity with Xpr1b (Figure 5A). To investigate the function of xpr1a, we used TALE-nucleases to generate mutations near the 5′ end of xpr1a coding sequence (Figure 5D). Homozygous mutants for two different frameshift mutations in xpr1a (st91, st92) had normal microglia development and gross embryonic morphology (Figures 5E and 5F and unpublished data). xpr1a homozygous mutants were viable as adults. Additionally, xpr1b; xpr1a double mutants resembled xpr1b single mutants, with reduced microglia but otherwise normal morphology in the embryo and early larva. Despite the evidence that XPR1 is the main phosphate exporter in metazoans, our genetic studies indicate the function of Xpr1 is required in specific cell types, including at least several macrophage lineages, and not broadly across all tissues.

Figure 5. xpr1a encodes a functional phosphate exporter but is not required for microglia development or embryonic development.

(A) Graphic representation of the domain structure of Xpr1b and Xpr1a showing their shared identity. (B) Graph representing the percentage of rescued xpr1b mutants when either xpr1b, control mcherry (C) or xpr1a are expressed in the macrophage lineage. (C) Representative dorsal image of a neutral red stained 5 dpf xpr1b mutant larva rescued by expression of xpr1a in the macrophage lineage. (D) Top panel shows diagram depicting the TALE nuclease targeted nucleotide sequence and the corresponding amino acid sequence of xpr1a. Bottom panels show the two alleles generated that have frameshift mutations in xpr1a coding sequence resulting in premature stop codons. (E) Dorsal views of neutral red stained 5 dpf xpr1a mutant (left) and xpr1b;xpr1a double mutant (right), showing that xpr1a mutants have a normal number of microglia cells. (F) Lateral views of neutral red stained 5dpf xpr1a mutant (left) and xpr1b;xpr1a double mutant (right), show grossly normal development at 5 dpf. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Transgenic expression of Xpr1a rescues microglia in xpr1b mutants

To test if Xpr1a can functionally substitute for Xpr1b, we injected the progeny of an xpr1b heterozygous intercross with a transgene expressing xpr1a under the control of the macrophage lineage promoter, mpeg1. Expression of Xpr1a in the macrophage lineage rescued xpr1b mutants to similar levels as expression of Xpr1b (63% rescue with Xpr1a [n = 27] vs. 69% rescue with Xpr1b [n = 20], Figure 5B and 5C). Although zygotic xpr1a is not required for normal development, these results indicate that Xpr1a can fulfil the function of Xpr1b when expressed in the macrophage lineage.

DISCUSSION

XPR1, initially identified as a receptor for xenotropic and polytropic gamma retroviruses, is the only known phosphate exporter in metazoans (Giovannini et al., 2013). This multipass transmembrane protein is highly conserved across evolution, and closely related proteins are present in species as diverse as humans, plants and unicellular eukaryotes. Previous analysis suggested that Xpr1 mediates phosphate export in a wide range of vertebrate cell types (Giovannini et al., 2013), but prior genetic studies did not analyse the role of Xpr1 in vertebrates in vivo. Our genetic analysis in zebrafish provides strong evidence that Xpr1b has a unique and specific function in highly specialized tissue-resident macrophages, including microglia and osteoclasts.

Phosphate homeostasis and tissue specificity

In light of the functional conservation of Xpr1 homologues among metazoans and in budding yeast, the cell type specificity of Xpr1b is remarkable. Complex regulatory mechanisms control phosphate homeostasis in unicellular and multicellular organisms. In the latter, Pi homeostasis occurs both at the cellular and organismal level. Cellular phosphate influx largely relies on the presence of sodium-dependent phosphate transporters (Biber et al., 2013, Forster et al., 2013). Whereas some of these transporters are ubiquitously expressed (e.g. SLC20A1 and SLCA20A2), expression of others (e.g. SLC34) is almost exclusively restricted to certain tissues with critical function in regulating organismal phosphate levels, such as the small intestine and kidney (Biber et al., 2013, Forster et al., 2013). The expression and activity of these transporters are regulated by many factors to ensure that phosphate homeostasis is maintained.

The biochemical function of Xpr1 as a phosphate exporter was only recently described (Giovannini et al., 2013), and the role of phosphate exporters in organismal phosphate homeostasis remains elusive. Our data suggest that Xpr1b is not required for phosphate transport or other functions in most cell types but is instead required in a specific subset of cells, including microglia, Langerhans cells and osteoclasts. Our analysis suggests that the regulated activity of sodium-dependent phosphate transporters is sufficient for proper phosphate balance in most cell types, and that the requirement for dedicated phosphate exporters is restricted to cells that experience extreme phosphate fluctuations. Such cells could include highly phagocytic cells, including microglia, cells involved in phosphate (re)absorption (e.g. small intestine enterocytes and proximal tubule cells) and cells involved in bone resorption (osteoclasts). In fact, the presence of a dedicated phosphate exporter has long been hypothesized in epithelial renal cells and osteoclasts (Barac-Nieto et al., 2002, Ito et al., 2007). In particular, osteoclasts were shown to have a unique Pi efflux system, involved in the continuous release of Pi at the basolateral plasma membrane preventing accumulation of intracellular inorganic phosphate (Ito et al., 2007). In assays of cultured mammalian cells, Xpr1 mediates phosphate export (Giovannini et al., 2013), and our genetic studies indicate that Xpr1b has an essential function in osteoclasts and other tissue macrophages in vivo. To explore the possibility that xpr1a, which encodes a protein 80% identical to Xpr1b, might have functions overlapping with xpr1b, we used transgenic and mutational approaches. As one might expect from the extent of sequence similarity, our experiments indicate that a transgene expressing Xpr1a in the macrophage lineage restores microglia in xpr1b mutants. Nonetheless, xpr1a mutants were phenotypically indistinguishable from their wildtype siblings, and xpr1b:xpr1a double mutants were phenotypically similar to xpr1b single mutants. Therefore, it seems that the zygotic functions Xpr1b and Xpr1a are largely dispensable for the early development of many cell types. It is important to note that earlier functions, in and out of the macrophage lineage, might be masked by the maternal expression of both these proteins. Nevertheless, the double mutants survive for at least 20 days postfertilization, further supporting the possibility that these phosphate exporters have cell–type specific rather than general functions.

Xpr1b and development of tissue-resident macrophages

The cytokine colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF1), the interleukin IL-34 and their receptor, colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R), are key regulators of macrophage development (Davies et al., 2013, Wynn et al., 2013). Studies in mouse, rat, and zebrafish have revealed a conserved role of the macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (csfr1a aka fms) in the establishment of many tissue-resident populations, including microglia, osteoclasts and Langerhans cells (Droin and Solary, 2010, Nakamichi et al., 2013). In zebrafish, csfr1a mutants (panther mutants) have primitive macrophages, which proliferate and move, but fail to colonize the brain and other target tissues (Herbomel et al., 2001). Similarly, migration of macrophages into the brain is reduced in xpr1b mutants. In contrast to csfr1a/panther mutants, in xpr1b mutants the small number of macrophages that are able to enter the brain parenchyma do not differentiate into apoe-expressing microglia. In addition, in xpr1b mutants there is no recovery of the microglia population as larval development begins, in contrast to csfr1a/panther mutant larvae, which gain increasing numbers of microglia as larval development progresses. csfr1a/panther and xpr1b mutants also share an osteopetrotic phenotype, which appears to be more severe in xpr1b mutants, as judged by the extent of occlusion of the neural and hemal canals. Although we did not experimentally address the autonomy of Xpr1b in Langerhans cells and osteoclasts, we have shown that Xpr1b acts autonomously in the macrophage lineage to rescue the microglia phenotype. Because Langerhans and osteoclasts are also derived in part from primitive macrophages (Ginhoux et al., 2010, Hoeffel et al., 2012), it is likely that that Xpr1b acts autonomously not only in microglia but in these other tissue macrophage populations as well. Further experiments are required to determine if there is any relationship between xpr1b and csfr1a signalling and to determine the mechanisms by which the loss of the phosphate exporter disrupts the establishment of tissue resident macrophage populations. It is also possible that XPR1 has other functions that are essential for development of tissue macrophages, in addition to its activity as a phosphate exporter (Giovannini et al., 2013, Wege and Poirier, 2014).

In summary, we show that the phosphate exporter Xpr1b acts specifically and autonomously in the macrophage lineage. Our analysis of xpr1a mutants and xpr1b;xpr1a double mutants shows that the zygotic function of this phosphate exporter is required only in specific cell types and not generally for development and survival of the larva. Our xpr1a and xpr1b mutants will be valuable in the analysis of the intricate regulation of phosphate homeostasis at the cellular and organismal level in vivo.

Experimental Procedures

Zebrafish lines and embryos

Wildtype (TL, AB/TU and WK), transgenic and heterozygous xpr1b fish were raised at 28.5°C and staged as described (Kimmel et al., 1995). To inhibit pigmentation, embryos were treated with 0.003% 1-phenyl-2-thiourea (PTU) in methylene blue embryo water. The transgenic lines Tg(lyz:EGFP), Tg(mpeg1:EGFP) and Tg(kdrl:mCherry-CAAX) have been previously described (Hall et al., 2007, Ellett et al., 2011, Fujita et al., 2011).

ENU mutagenesis, microglia screen and neutral red assay

Founder P0 wildtype males were mutagenized with N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) and subsequently outcrossed to raise F1 and F2 families for screening as described (Pogoda et al., 2006). An F3 genetic screen was conducted to identify putative mutants with specific defects in microglia (e.g. loss of microglia) but no apparent anatomical morphological defects at 5 dpf. Microglial cells were scored in live 3 to 5 dpf larvae after treatment with the vital dye neutral red as described (Shiau et al. 2013). Briefly, larvae were incubated in embryo water containing 2.5 μg/ml neutral red at 28.5°C for 2–3 hrs, followed by two water changes and analysed 4–24hrs later using a dissection microscope.

Genetic mapping

st87 mutant embryos were separated from wildtype siblings based on the neutral red phenotype, lack of microglia, at 5 dpf. Bulk segregant analysis with 480 simple sequence length polymorphisms (SSLPs) (Pogoda et al., 2006) identified markers on LG2 flanking the st87 mutation. High resolution mapping was conducted using additional SSLPs and single nucleotide polymorphisms linked to the mutation, which were found from sequencing PCR fragments amplified from genomic DNA of mutants and wildtype siblings. Sequencing of PCR products of genes in the critical interval identified st87 lesion in the xpr1b gene. st87 lesion was genotyped based on the PCR/restriction digest assay using the forward primer (5′-GCTGCTAACAGAATACTTCCT-3′), reverse primer (5′-CCAGTCCCGGCTTGGACTCTGA-3′) and digestion with DdeI.

Sequence specific TALE nucleases

The 5′ regions of xpr1b and xpr1a genes were selected as targets. The web tool TAL Effector-Nucleotide Targeter 2.0 (TALE-NT 2.0; https://tale-nt.cac.cornell.edu) was used to design TALEN pairs and identify a diagnostic restriction enzyme,. The specific sequence for each TALEN is detailed in Table S1. TALEN assembly followed the PCR/Golden Gate cloning protocol (Sanjana et al., 2012). TALE nuclease mRNA was transcribed using the Sp6 mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion). A total of 400–800 pg of TALE nuclease mRNA was injected into 1–2 cell stage embryos which were raised at 28.5°C. Carriers of deletions in xpr1b and xpr1a gene were identified by PCR/restriction digest assay with the primers present in Table S1 and the restriction enzymes FspI and Hpy188III. Stable lines of two different alleles for each gene were established.

Whole mount in situ hybridization

In situ hybridization on whole zebrafish embryos and larvae was performed as previously described (Pogoda et al., 2006). Antisense riboprobes were transcribed for lyz, mfap4, apoe, and mpx as described Shiau et al., 2013.

Time-lapse and fluorescent imaging

Embryos and larvae used for live imaging were treated with 0.016% (w/v) Tricaine, mounted in 1.5% low-melting-point agarose and imaged at room temperature. Images for determination of average number of mpeg1:EGFP positive cells were acquired on a Zeiss Axio Observer microscope coupled to a Perkin Elmer UltraView vox spinning disk confocal. Images of laterally mounted embryos and larvae were captured with a Hamamatsu camera, using the Volocity Acquisition suite for multidimensional multichannel time-lapse recording. Images were analysed using Volocity software and processed with Adobe Photoshop. All other imaging was done on a Zeiss LSM 5 Pascal confocal microscope. Image J software was used to make maximum intensity projections of z-stacks and images were processed for contrast and brightness in Photoshop. The average number of Langerhans cells was determined by counting the number of mpeg1:EGFP positive cells present in the skin in the field of view. Images were taken always from the region immediately posterior to the anal fin. Analysis of the number of projections per cell was done per field of view and in maximum intensity projections obtained using Image J software. Time-lapse imaging of mpeg1:EGFP; kdrl:mcherryCAAX transgenic line was done by capturing 1 z-stack per 20 seconds for 30min, using the 20x objective.

Expression constructs

The coding sequences of xpr1b and xpr1b were cloned from a 5 dpf embryonic cDNA pool and directionally inserted into pCR8/GW/TOPO vector (Invitrogen), primers used are in Table S1. For RNA expression, xpr1b sequence was subcloned into the pCSDest vector using multsite GATEWAY technology (Kwan et al., 2007). Tol2 sequence containing constructs used for tissue-specific expression were also made using multisite GATEWAY (Kwan et al., 2007). The tissue-specific regulatory sequences used have been reported elsewhere (Shiau et al., 2013). Tissue-specific transgenes were transiently expressed by co-injecting 12–25 pg of Tol2-plasmids described above and 100–200pg of Tol2 transposase mRNA in 1 cell embryos.

Bone remodeling phenotypes

Wild type (xpr1b+/+, n=6), heterozygous (xpr1bst87/+ and xpr1bst89/+, n=3 and n=4 respectively) and mutant fish (xpr1bst87/st89, n=6) were collected when their standard length was 2.5 cm, fixed in 4% PFA for 24 hrs, and rinsed in 1x PBS. Skeletal phenotypes were evaluated by micro-computerized topography (μCT). Fish were scanned in 1x PBS using a Scanco μCT40 operated at 70kVp, 114 μA, at medium resolution, and with 2x-averaging. Voxel size was 12 μm3 for all fish. Evaluation of the 14th and 16th vertebral arches was performed on an average of 63 (hemal) and 65 (neural) two-dimensional slices (~750–780 μm) beginning at the anterior edge of each arch. Volumetric reconstruction images were imported into Adobe Photoshop and measured to determine the average canal aperture for each genotypic class (defined as the total number of pixels corresponding to the arch opening). Bone volume (Direct) and surface area (TRI-plate model) measurements were evaluated using Scanco/OpenVMS software.

Characterization of vertebral body defects of the 14th and 16th vertebrae was performed by evaluation of an average of 53 two-dimensional slices (~640 μm) beginning at the anterior edge of each vertebra. Bone volume and surface area measurements were determined as above. Statistical significance of all measurements was determined by unpaired, two-tailed t tests.

Supplementary Material

3 dpf wildtype embryos carrying the transgenes mpeg1:EGFP (macrophage marker) and kdrl:mCherryCAAX (vasculature marker) were imaged in a spinning disc confocal microscope every 4 min for 2 to 4 hrs. Z-stack images were taken from a dorsal view. Macrophages are able to move and colonize the brain. A mitosis event can be seen in the left eye. No cell death events were observed. 3 hrs real time, 7 fps; 20x objective.

3 dpf xpr1b mutant embryos carrying the transgenes mpeg1:eGFP (macrophage marker) and kdrl:mCherry-CAAX (vasculature marker) were imaged in a spinning disc confocal microscope every 4 min for 2 to 4 hrs. Z-stack images were taken from a dorsal view. Although fewer macrophages are present, macrophages are able to move and can be seen penetrating the brain. No cell death events were observed. 3 hrs real time, 7 fps; 20x objective.

2.5 dpf wildtype embryos carrying the transgenes mpeg1:EGFP (macrophage marker) and kdrl:mCherryCAAX (vasculature marker) were imaged in a confocal microscope every 20 s for 30min. Z-stack images were taken from lateral view. Macrophages are able to move and can be seen penetrating the brain. 30 min real time, 7 fps; 20x objective.

2.5 dpf xpr1b mutant embryos carrying the transgenes mpeg1:EGFP (macrophage marker) and kdrl:mCherryCAAX (vasculature marker) were imaged in a confocal microscope every 20 s for 30 min. Z-stack images were taken from lateral view. Macrophages are able to move and can be seen penetrating the brain. 30 min real time, 7 fps; 20x objective.

Figure S1. xpr1b mRNA can rescue xp1b mutants.

(A) Representative dorsal view images of 5 dpf neutral red stained xpr1b mutant fish uninjected (control) or injected with xpr1b mRNA (right). Microglia are present only when xpr1b mRNA was injected. (B) Graph shows the percentage of rescue. Scale bar = 50 μm. (C) Top panel shows diagram depicting the TALE nuclease targeted nucleotide sequence and the corresponding amino acid sequence of xpr1b. Bottom panels show two of the alleles generated that have frameshift mutations in xpr1b coding sequence that result in premature stop codons. (E) Dorsal views of neutral red stained 5 dpf xpr1b heterozygote (left) and xpr1b mutant (right), showing that the new xpr1b alleles phenocopy xpr1bst87.

Figure 2. xpr1b mutants have normal mitotic timing.

(A) Still images from time-lapse videos from 2dpf wild type embryos (top) and xpr1b mutants (bottom). Mitotic timing of xpr1b mutant macrophages is comparable to that of its siblings. (B) Graph depicts the number of cell divisions per hour, per field of view. Error bars show s.e.m. Statistical significance was determined using paired two-tailed Student’s t test. There is no statistical difference between xpr1b mutants and its siblings. Images were acquired every 5 min for 2–4 hrs.

Figure S3. xpr1b mutants have a moderate increase in neutrophil numbers but no signs of increased inflammation.

(A) Whole-mount in situ hybridization with the neutrophil specific marker mpx shows that xpr1b mutants (right) have more neutrophils in the head than their siblings. (B) Representative image of Z-projection from a stable transgenic line expressing GFP under the control of the neutrophil specific promoter lysozyme (lyz). xpr1b mutants have more neutrophils per field of view than their siblings. (C) Graph showing the average number of neutrophils present in the field of view represented by the highlighted box in the fish diagram. xpr1b mutants have more neutrophils than their siblings. (D) Graph depicts the relative mRNA levels of proinflammatory cytokines measured by qPCR, comparing xpr1b mutants and their siblings at 3 dpf. P = 0.23 (il-1β), P = 0.57 (tnfα), and P = 0.16 (il-8) determined using an unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test. (E) Graph depicts the percentage of larvae rescued after injection of nlrc3-like mRNA, showing rescue for nlrc3-like mutants but not for xpr1b mutants. (F) Graph depicts the percentage of larvae rescued after injection of mpeg1:xpr1b DNA, showing rescue for xpr1b mutants but not for nlrc3-like mutants. Error bars show s.e.m. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Figure S4. xpr1b mutant Langerhans cells have fewer processes than wildtype Langerhans cells.

(A) Graph depicts the average number of processes present in Langerhans cells in xpr1b mutants and their sibling counterparts. The number of processes present in 3 Langerhans cells per fish were counted. Mutants analysed = 6; Siblings analysed = 5. Error bars show s.e.m. Statistical significance was determined using paired two-tailed Student’s t test. ** P < 0.01

Figure S5. xpr1b is required for normal skeletal development.

(A) Graph represent the percentage of fish with different genotype at each time point. xpr1b mutants are under-represented at later stages, indicating that they have a lower survival rate. (B) Graph depicts the size distribution of wildtype and xpr1b mutant fish at 50 dpf. xpr1b mutants are smaller than their wildtype counterparts. *** P < 0.0005, determined by paired, two-tailed t test. (C) μCT-derived volumetric reconstructions of the neural (top) and hemal (bottom) 16th vertebral arches from a representative wild type, heterozygous and mutant fish. scale bar = 100 μm. (D–I) Graphs showing quantified values for the vertebral arch defect depicted in (C). xpr1b mutant fish exhibit significant reductions in canal aperture (D, G) with a concomitant increase in the total amount of bone as measured by bone volume (BV; E, H) and surface area (SA; F, I). (J) Volumetric reconstructions of the 16th vertebral bodies from a representative wild type, heterozygous and mutant fish. Scale bar = 100 μm. (K, L) Graphs depicting the significant increase in the total amount of bone present in mutant vertebrae as measured by BV (K) and SA (L). Error bars show s.e.m. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired, two-tailed t tests. * P < 0.05, *** P < 5×10−4.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to M. Barna and S. Kim for sharing equipment. Special thanks to Talbot lab members for critical comments on the manuscript and T. Reyes and C. Hill for fish care. A.M.M. was supported by EMBO fellowship ALTF 1125-2011. C.E.S. was supported by NIH NRSA fellowship 5F32NS067754, and H. S. was supported by an A*STAR fellowship. This work was supported by NIH grant R01 NS065787 to W.S.T.

Footnotes

Author contributions

A.M.M. mapped the st87 mutation, generated st89, st90, st91, st92 and conducted all experiments on xpr1b and xpr1a mutants. C.E.S., H.S. A.M.M and W.S.T. performed the genetic screen. C.E.S performed analyzed the genetic interaction of nlrc3-like and xrp1. C.G. and D.M.K. performed all the analysis of bone development. A.M.M. and W.S.T. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript, with input from all the authors.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could a3ect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- BARAC-NIETO M, ALFRED M, SPITZER A. Basolateral phosphate transport in renal proximal-tubule-like OK cells. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2002;227:626–31. doi: 10.1177/153537020222700811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BATTINI JL, RASKO JE, MILLER AD. A human cell-surface receptor for xenotropic and polytropic murine leukemia viruses: possible role in G protein-coupled signal transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:1385–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEGG SK, RADLEY JM, POLLARD JW, CHISHOLM OT, STANLEY ER, BERTONCELLO I. Delayed hematopoietic development in osteopetrotic (op/op) mice. J Exp Med. 1993;177:237–42. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.1.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIBER J, HERNANDO N, FORSTER I. Phosphate transporters and their function. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013;75:535–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHATANI M, TAKANO Y, KUDO A. Osteoclasts in bone modeling, as revealed by in vivo imaging, are essential for organogenesis in fish. Dev Biol. 2011;360:96–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHRISTIAN M, CERMAK T, DOYLE EL, SCHMIDT C, ZHANG F, HUMMEL A, BOGDANOVE AJ, VOYTAS DF. Targeting DNA double-strand breaks with TAL effector nucleases. Genetics. 2010;186:757–61. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.120717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVIES LC, JENKINS SJ, ALLEN JE, TAYLOR PR. Tissue-resident macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:986–95. doi: 10.1038/ni.2705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DROIN N, SOLARY E. Editorial: CSF1R, CSF-1, and IL-34, a “menage a trois” conserved across vertebrates. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;87:745–7. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1209780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELLETT F, PASE L, HAYMAN JW, ANDRIANOPOULOS A, LIESCHKE GJ. mpeg1 promoter transgenes direct macrophage-lineage expression in zebrafish. Blood. 2011;117:e49–56. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-314120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FORSTER IC, HERNANDO N, BIBER J, MURER H. Phosphate transporters of the SLC20 and SLC34 families. Mol Aspects Med. 2013;34:386–95. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FUJITA M, CHA YR, PHAM VN, SAKURAI A, ROMAN BL, GUTKIND JS, WEINSTEIN BM. Assembly and patterning of the vascular network of the vertebrate hindbrain. Development. 2011;138:1705–15. doi: 10.1242/dev.058776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GINHOUX F, GRETER M, LEBOEUF M, NANDI S, SEE P, GOKHAN S, MEHLER MF, CONWAY SJ, NG LG, STANLEY ER, SAMOKHVALOV IM, MERAD M. Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science. 2010;330:841–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1194637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIOVANNINI D, TOUHAMI J, CHARNET P, SITBON M, BATTINI JL. Inorganic phosphate export by the retrovirus receptor XPR1 in metazoans. Cell Rep. 2013;3:1866–73. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALL C, FLORES MV, STORM T, CROSIER K, CROSIER P. The zebrafish lysozyme C promoter drives myeloid-specific expression in transgenic fish. BMC Dev Biol. 2007;7:42. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERBOMEL P, THISSE B, THISSE C. Zebrafish early macrophages colonize cephalic mesenchyme and developing brain, retina, and epidermis through a M-CSF receptor-dependent invasive process. Dev Biol. 2001;238:274–88. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOEFFEL G, WANG Y, GRETER M, SEE P, TEO P, MALLERET B, LEBOEUF M, LOW D, OLLER G, ALMEIDA F, CHOY SH, GRISOTTO M, RENIA L, CONWAY SJ, STANLEY ER, CHAN JK, NG LG, SAMOKHVALOV IM, MERAD M, GINHOUX F. Adult Langerhans cells derive predominantly from embryonic fetal liver monocytes with a minor contribution of yolk sac-derived macrophages. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1167–81. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITO M, HAITO S, FURUMOTO M, UEHATA Y, SAKURAI A, SEGAWA H, TATSUMI S, KUWAHATA M, MIYAMOTO K. Unique uptake and efflux systems of inorganic phosphate in osteoclast-like cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C526–34. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00357.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIMMEL CB, BALLARD WW, KIMMEL SR, ULLMANN B, SCHILLING TF. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 1995;203:253–310. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KWAN KM, FUJIMOTO E, GRABHER C, MANGUM BD, HARDY ME, CAMPBELL DS, PARANT JM, YOST HJ, KANKI JP, CHIEN CB. The Tol2kit: a multisite gateway-based construction kit for Tol2 transposon transgenesis constructs. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:3088–99. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKAMICHI Y, UDAGAWA N, TAKAHASHI N. IL-34 and CSF-1: similarities and differences. J Bone Miner Metab. 2013;31:486–95. doi: 10.1007/s00774-013-0476-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAOLICELLI RC, BOLASCO G, PAGANI F, MAGGI L, SCIANNI M, PANZANELLI P, GIUSTETTO M, FERREIRA TA, GUIDUCCI E, DUMAS L, RAGOZZINO D, GROSS CT. Synaptic pruning by microglia is necessary for normal brain development. Science. 2011;333:1456–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1202529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PERI F, NUSSLEIN-VOLHARD C. Live imaging of neuronal degradation by microglia reveals a role for v0-ATPase a1 in phagosomal fusion in vivo. Cell. 2008;133:916–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POGODA HM, STERNHEIM N, LYONS DA, DIAMOND B, HAWKINS TA, WOODS IG, BHATT DH, FRANZINI-ARMSTRONG C, DOMINGUEZ C, ARANA N, JACOBS J, NIX R, FETCHO JR, TALBOT WS. A genetic screen identifies genes essential for development of myelinated axons in zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2006;298:118–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POLLARD JW. Role of colony-stimulating factor-1 in reproduction and development. Mol Reprod Dev. 1997;46:54–60. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199701)46:1<54::AID-MRD9>3.0.CO;2-Q. discussion 60–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RANSOHOFF RM, CARDONA AE. The myeloid cells of the central nervous system parenchyma. Nature. 2010;468:253–62. doi: 10.1038/nature09615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANJANA NE, CONG L, ZHOU Y, CUNNIFF MM, FENG G, ZHANG F. A transcription activator-like effector toolbox for genome engineering. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:171–92. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHAFER DP, LEHRMAN EK, KAUTZMAN AG, KOYAMA R, MARDINLY AR, YAMASAKI R, RANSOHOFF RM, GREENBERG ME, BARRES BA, STEVENS B. Microglia sculpt postnatal neural circuits in an activity and complement-dependent manner. Neuron. 2012;74:691–705. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SECCO D, WANG C, ARPAT BA, WANG Z, POIRIER Y, TYERMAN SD, WU P, SHOU H, WHELAN J. The emerging importance of the SPX domain-containing proteins in phosphate homeostasis. New Phytol. 2012a;193:842–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.04002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SECCO D, WANG C, SHOU H, WHELAN J. Phosphate homeostasis in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the key role of the SPX domain-containing proteins. FEBS Lett. 2012b;586:289–95. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEGOVIA-SILVESTRE T, NEUTZSKY-WULFF AV, SORENSEN MG, CHRISTIANSEN C, BOLLERSLEV J, KARSDAL MA, HENRIKSEN K. Advances in osteoclast biology resulting from the study of osteopetrotic mutations. Hum Genet. 2009;124:561–77. doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0583-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHIAU CE, MONK KR, JOO W, TALBOT WS. An anti-inflammatory NOD-like receptor is required for microglia development. Cell Rep. 2013;5:1342–52. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SVAHN AJ, GRAEBER MB, ELLETT F, LIESCHKE GJ, RINKWITZ S, BENNETT MR, BECKER TS. Development of ramified microglia from early macrophages in the zebrafish optic tectum. Dev Neurobiol. 2013;73:60–71. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAILOR CS, NOURI A, LEE CG, KOZAK C, KABAT D. Cloning and characterization of a cell surface receptor for xenotropic and polytropic murine leukemia viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:927–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAUGHAN AE, MENDOZA R, ARANDA R, BATTINI JL, MILLER AD. Xpr1 is an atypical G-protein-coupled receptor that mediates xenotropic and polytropic murine retrovirus neurotoxicity. J Virol. 2012;86:1661–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06073-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEGE S, POIRIER Y. Expression of the mammalian Xenotropic Polytropic Virus Receptor 1 (XPR1) in tobacco leaves leads to phosphate export. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:482–9. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WYNN TA, CHAWLA A, POLLARD JW. Macrophage biology in development, homeostasis and disease. Nature. 2013;496:445–55. doi: 10.1038/nature12034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANG YL, GUO L, XU S, HOLLAND CA, KITAMURA T, HUNTER K, CUNNINGHAM JM. Receptors for polytropic and xenotropic mouse leukaemia viruses encoded by a single gene at Rmc1. Nat Genet. 1999;21:216–9. doi: 10.1038/6005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZAKRZEWSKA A, CUI C, STOCKHAMMER OW, BENARD EL, SPAINK HP, MEIJER AH. Macrophage-specific gene functions in Spi1-directed innate immunity. Blood. 2010;116:e1–11. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-262873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

3 dpf wildtype embryos carrying the transgenes mpeg1:EGFP (macrophage marker) and kdrl:mCherryCAAX (vasculature marker) were imaged in a spinning disc confocal microscope every 4 min for 2 to 4 hrs. Z-stack images were taken from a dorsal view. Macrophages are able to move and colonize the brain. A mitosis event can be seen in the left eye. No cell death events were observed. 3 hrs real time, 7 fps; 20x objective.

3 dpf xpr1b mutant embryos carrying the transgenes mpeg1:eGFP (macrophage marker) and kdrl:mCherry-CAAX (vasculature marker) were imaged in a spinning disc confocal microscope every 4 min for 2 to 4 hrs. Z-stack images were taken from a dorsal view. Although fewer macrophages are present, macrophages are able to move and can be seen penetrating the brain. No cell death events were observed. 3 hrs real time, 7 fps; 20x objective.

2.5 dpf wildtype embryos carrying the transgenes mpeg1:EGFP (macrophage marker) and kdrl:mCherryCAAX (vasculature marker) were imaged in a confocal microscope every 20 s for 30min. Z-stack images were taken from lateral view. Macrophages are able to move and can be seen penetrating the brain. 30 min real time, 7 fps; 20x objective.

2.5 dpf xpr1b mutant embryos carrying the transgenes mpeg1:EGFP (macrophage marker) and kdrl:mCherryCAAX (vasculature marker) were imaged in a confocal microscope every 20 s for 30 min. Z-stack images were taken from lateral view. Macrophages are able to move and can be seen penetrating the brain. 30 min real time, 7 fps; 20x objective.

Figure S1. xpr1b mRNA can rescue xp1b mutants.

(A) Representative dorsal view images of 5 dpf neutral red stained xpr1b mutant fish uninjected (control) or injected with xpr1b mRNA (right). Microglia are present only when xpr1b mRNA was injected. (B) Graph shows the percentage of rescue. Scale bar = 50 μm. (C) Top panel shows diagram depicting the TALE nuclease targeted nucleotide sequence and the corresponding amino acid sequence of xpr1b. Bottom panels show two of the alleles generated that have frameshift mutations in xpr1b coding sequence that result in premature stop codons. (E) Dorsal views of neutral red stained 5 dpf xpr1b heterozygote (left) and xpr1b mutant (right), showing that the new xpr1b alleles phenocopy xpr1bst87.

Figure 2. xpr1b mutants have normal mitotic timing.

(A) Still images from time-lapse videos from 2dpf wild type embryos (top) and xpr1b mutants (bottom). Mitotic timing of xpr1b mutant macrophages is comparable to that of its siblings. (B) Graph depicts the number of cell divisions per hour, per field of view. Error bars show s.e.m. Statistical significance was determined using paired two-tailed Student’s t test. There is no statistical difference between xpr1b mutants and its siblings. Images were acquired every 5 min for 2–4 hrs.

Figure S3. xpr1b mutants have a moderate increase in neutrophil numbers but no signs of increased inflammation.

(A) Whole-mount in situ hybridization with the neutrophil specific marker mpx shows that xpr1b mutants (right) have more neutrophils in the head than their siblings. (B) Representative image of Z-projection from a stable transgenic line expressing GFP under the control of the neutrophil specific promoter lysozyme (lyz). xpr1b mutants have more neutrophils per field of view than their siblings. (C) Graph showing the average number of neutrophils present in the field of view represented by the highlighted box in the fish diagram. xpr1b mutants have more neutrophils than their siblings. (D) Graph depicts the relative mRNA levels of proinflammatory cytokines measured by qPCR, comparing xpr1b mutants and their siblings at 3 dpf. P = 0.23 (il-1β), P = 0.57 (tnfα), and P = 0.16 (il-8) determined using an unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test. (E) Graph depicts the percentage of larvae rescued after injection of nlrc3-like mRNA, showing rescue for nlrc3-like mutants but not for xpr1b mutants. (F) Graph depicts the percentage of larvae rescued after injection of mpeg1:xpr1b DNA, showing rescue for xpr1b mutants but not for nlrc3-like mutants. Error bars show s.e.m. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Figure S4. xpr1b mutant Langerhans cells have fewer processes than wildtype Langerhans cells.

(A) Graph depicts the average number of processes present in Langerhans cells in xpr1b mutants and their sibling counterparts. The number of processes present in 3 Langerhans cells per fish were counted. Mutants analysed = 6; Siblings analysed = 5. Error bars show s.e.m. Statistical significance was determined using paired two-tailed Student’s t test. ** P < 0.01

Figure S5. xpr1b is required for normal skeletal development.

(A) Graph represent the percentage of fish with different genotype at each time point. xpr1b mutants are under-represented at later stages, indicating that they have a lower survival rate. (B) Graph depicts the size distribution of wildtype and xpr1b mutant fish at 50 dpf. xpr1b mutants are smaller than their wildtype counterparts. *** P < 0.0005, determined by paired, two-tailed t test. (C) μCT-derived volumetric reconstructions of the neural (top) and hemal (bottom) 16th vertebral arches from a representative wild type, heterozygous and mutant fish. scale bar = 100 μm. (D–I) Graphs showing quantified values for the vertebral arch defect depicted in (C). xpr1b mutant fish exhibit significant reductions in canal aperture (D, G) with a concomitant increase in the total amount of bone as measured by bone volume (BV; E, H) and surface area (SA; F, I). (J) Volumetric reconstructions of the 16th vertebral bodies from a representative wild type, heterozygous and mutant fish. Scale bar = 100 μm. (K, L) Graphs depicting the significant increase in the total amount of bone present in mutant vertebrae as measured by BV (K) and SA (L). Error bars show s.e.m. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired, two-tailed t tests. * P < 0.05, *** P < 5×10−4.