Abstract

Psychiatric disorders are complex multifactorial illnesses involving chronic alterations in neural circuit structure and function. While genetic factors are important in the etiology of disorders such as depression and addiction, relatively high rates of discordance among identical twins clearly indicate the importance of additional mechanisms. Environmental factors such as stress or prior drug exposure are known to play a role in the onset of these illnesses. Such exposure to environmental insults induces stable changes in gene expression, neural circuit function, and ultimately behavior, and these maladaptations appear distinct between developmental and adult exposures. Increasing evidence indicates that these sustained abnormalities are maintained by epigenetic modifications in specific brain regions. Indeed, transcriptional dysregulation and associated aberrant epigenetic regulation is a unifying theme in psychiatric disorders. Aspects of depression and addiction can be modeled in animals by inducing disease-like states through environmental manipulations (e.g., chronic-stress, drug administration). Understanding how environmental factors recruit the epigenetic machinery in animal models is revealing new insight into disease mechanisms in humans.

INTRODUCTION

Psychiatric disorders impose an ever-increasing burden on society. Major depression and drug addiction are complex phenomena resulting from the interaction of several factors including neurobiological, genetic, cultural, and life experience. Both depression and addiction are characterized by functional and transcriptional alterations in several limbic brain regions implicated in regulating stress responses and reward1; 2; 3; 4; 5. Advances in the last decade have identified epigenetic mechanisms as important effectors in psychiatric conditions. Indeed, being at the foundation of gene regulation, epigenetic mechanisms are ideal candidates for the study of depression and addiction. Epigenetic mechanisms refer to the highly complex organization of DNA. This includes primarily many types of histone modifications6 and nucleotide modifications such as DNA methylation7 and hydroxymethylation8. More recently, non-coding RNAs such as microRNAs (miRNA) have emerged as a related mechanism although not epigenetic per se. Mounting evidence has identified epigenetic regulation in the context of stress-induced depression and drug-induced addiction. These epigenetic alterations are site-specific, largely in post-mitotic cells, and appear to be de novo rather than inherited. The majority of these findings come from animal models although interesting insights in humans are starting to accumulate.

Early development marks a time of rapid brain development and enhanced susceptibility to environmental insults. Epigenetic mechanisms of gene regulation are a particularly attractive explanation for how early life exposures to stress or drugs exert life-long effects on neuropsychiatric phenomena. Developmental exposures to stress or drugs may have broader impact on epigenetic states and brain circuits than similar exposure later in life. Research to date has focused on relatively distinct neural circuits in exploring the consequences of developmental versus adult exposures.

The present review brings together findings relating to epigenetic mechanisms in depression and addiction from both adult and developmental studies and elaborates the potential offered by epigenetic analyses to better understand these complex disorders.

EPIGENETICS AND DEPRESSION

Depression is a complex and heterogeneous disorder. Stressful life events represent a major factor in vulnerability to depression. However, the difficulty in defining specific subsets of depression has made clear identification of its multiple etiologies very difficult. Animal models offer a useful approach to study depression. Indeed, the development of chronic stress paradigms over the last decade, combined with the ability to objectively measure anhedonia and stress susceptibility in rodents, have helped clarify the neural circuitry and neuroadaptations underlying aspects of depression.

Adult onset of depression

Our understanding of the role of epigenetics in adult depression comes primarily from studies of animals exposed to stress. While acute stress paradigms are designed to evaluate an animal’s initial coping response, chronic stress paradigms involve prolonged exposure to either physical9 or psychological stressors, such as social subordination10. Such chronic stress paradigms successfully recapitulate certain behavioral features of human depression. For instance, chronic stressors produce anhedonia-like symptoms, characterized by a decrease in reward-related behaviors such as reduced preference for sucrose and social interaction10; 11 that are rarely seen following acute stress. Additionally, some behavioral alterations induced by chronic stress are long-lasting and effectively reversed by chronic but not acute treatment with existing antidepressant medications10; 11, a treatment course comparable to that required in humans. Together, these findings suggest that chronic stress paradigms are more effective at modeling at least certain features or subtypes of the human depression syndrome, while acute studies may provide insight into neuronal adaptations that regulate short-lived responses to stressful events.

Histone modifications in depression

Histone tails may be posttranslationally modified by acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation, and ubiquitination, among others. The combinations of various marks at a multitude of residues are seemingly endless and ongoing research is attempting to translate the effect of this “histone code” to transcriptional regulation. Meanwhile, study of some better understood histone modifications are providing important insights into the pathophysiology of depression12.

Histone Acetylation

The potential importance of histone acetylation in depression was initially suggested by observations that histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition alone or in combination with antidepressant treatment ameliorated depression-like behavior in rodents13; 14; 15; 16; 17,18; 19; 20. In mice, chronic social defeat stress induces a transient decrease of H3K14 acetylation in nucleus accumbens (NAc; see Figure 1B; Figure 2), a key brain reward region, associated with a persistent reduction of HDAC214. Both findings are seen in the NAc of depressed humans as well. The observation that intra-NAc infusion of MS275, a specific inhibitor of class I HDACs, yields antidepressant-like effects suggests that the persistent increase in histone acetylation in NAc may facilitate adaptation to chronic stress14. In support of this, in a chronic unpredictable stress paradigm, overexpression of an Hdac2 dominant-negative in NAc was antidepressant, while expression of a form of Hdac2 with increased chromatin binding affinity was pro-depressant20. However, expression of Hdac5, a class II HDAC, is decreased in mice susceptible to social defeat stress and increased by chronic imipramine treatment suggesting a pro-resiliency effect of this HDAC. This is further supported by the heightened susceptibility to social defeat of Hdac5 knock-out mice21. The opposing effects of HDAC2 and HDAC5 are difficult to reconcile with a simplistic role of histone acetylation in depression and stress adaptation. However, it is conceivable that HDAC2 and HDAC5 may regulate distinct populations of genes. Additionally, it is important to note that HDAC5 could also regulate non-histone targets due to its cytoplasmic as well as nuclear localization. Genome-wide studies of NAc gene expression in defeated mice treated with fluoxetine or intra-NAc infusion of MS275 demonstrated that both treatments are able to reverse a large proportion of defeat-induced differential gene expression. Although each treatment regulated subsets of unique gene expression changes, there was also a degree of overlap in regulated targets, suggesting that antidepressant effects of fluoxetine may in part be mediated by regulation of histone acetylation14.

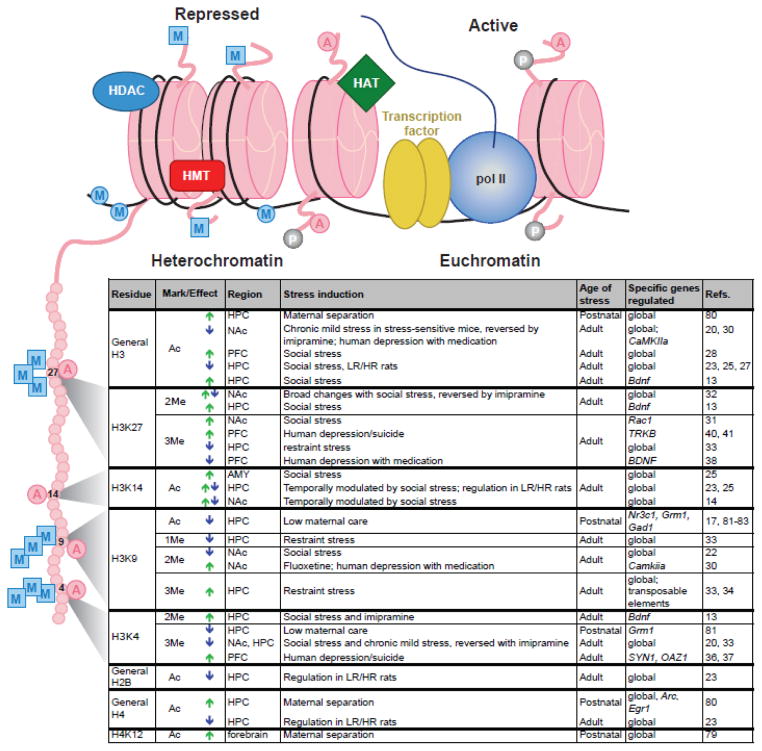

Figure 1. Epigenetic dysregulation in the HPA-axis and reward circuitry is implicated in psychiatric disorders.

A majority of research on altered epigenetic regulation in depression and other stress-related disorders has focused on changes within the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (A) and the brain’s reward circuitry (B), depicted here in rodent brain. Studies examining effects of early life manipulations on epigenetic regulation of behavior have focused on changes within the HPA axis, in contrast to adult studies, which have concentrated on epigenetic alterations in reward circuitry.

A) Main components of the HPA axis: corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) and vasopressin (AVP) from the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) stimulates adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) release from the anterior pituitary, which induces glucocorticoid (cortisol [human] or corticosterone [rodent]) release from the adrenal cortex. Glucocorticoid receptors (GRs) in the hippocampus (HPC) and other brain regions mediate negative feedback to reduce the stress response. B) Depicted are the major components of the limbic-reward circuitry: dopaminergic neurons (green) project from ventral tegmental area (VTA) to nucleus accumbens (NAc), prefrontal cortex (PFC), amygdala (AMY), and HPC. NAc receives excitatory glutamatergic innervation (red) from HPC, PFC, and AMY.

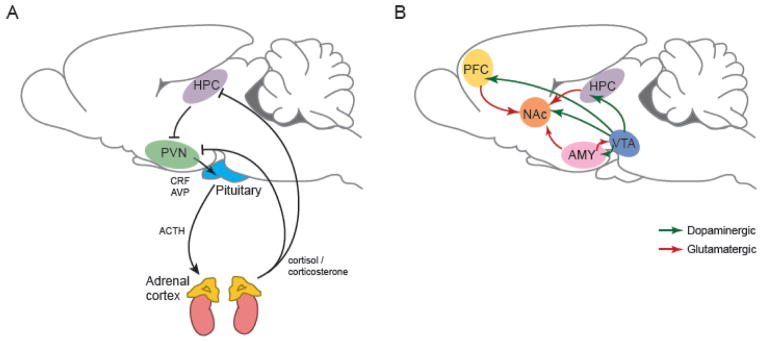

Figure 2. Examples of chromatin modifications regulated by stress or antidepressant treatment.

Illustration (top) indicates histone octamers (pink) in heterochromatin (left) and euchromatin (right), along with associated proteins and histone tail/DNA modifications. Table (bottom) lists histone tail modifications of specific residues—depicted on the expanded histone tail illustration (left)—that are regulated by various stress paradigms or antidepressant treatments within the indicated brain regions. Arrows indicate an increase (green) or decrease (blue) in specific modifications. Abbreviations: A, acetylation; P, phosphorylation; M (in a square), histone methylation; M (in a circle), DNA methylation; AMY, amygdala; HAT, histone acetyltransferase; HDAC, histone deacetylase; HPC, hippocampus; HMT, histone methyltransferase; HR and LR, high responding and low responding, respectively (with respect to baseline locomotor activity); PFC, prefrontal cortex; NAc, nucleus accumbens; pol II, RNA polymerase II. Modified from Ref 12, with permission.

Chronic stress paradigms also robustly regulate histone acetylation in the hippocampus (HPC; see Figure 1A&B), a brain region that is both highly sensitive to the effects of stress and implicated in the regulation of stress responses. In contrast to effects in the NAc, chronic social defeat stress transiently increases then persistently decreases global H3K14 acetylation and this decrease is reversed by chronic imipramine22 (see Figure 2). Imipramine also increases H3 acetylation at the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (Bdnf) promoter and this increase correlates with increased hippocampal Bdnf expression13. However, the initial stress-induced decrease in Bdnf after defeat may be mediated by increased H3K27 methylation at the Bdnf promoter rather than histone acetylation mechanisms. Intra-hippocampal HDAC inhibition by MS275 restores normal sucrose preference in defeated mice but alone does not alter social avoidance. However, MS275 treatment combined with social housing reversed social interaction deficits suggesting that histone acetylation in HPC may serve to facilitate adaptation and that defeat-induced reduction in H3K14 acetylation post-defeat is maladaptive. Whereas Hdac5 expression in NAc is antidepressant, in HPC Hdac5 is downregulated by imipramine in defeated mice and hippocampal overexpression of Hdac5 blocks the antidepressant actions of imipramine.

In a genetic rat model of stress susceptibility, high responders (HR), which exhibit basal reductions in anxiety and increased sucrose preference relative to low responders (LR), have increased CREB-binding protein (a histone acetyl transferase or HAT), lower HDAC3, and higher global H3 and H2B acetylation levels in hippocampus23. However, HR rats are more susceptible to chronic social defeat than LR rats and exhibit reduced sucrose preference post-defeat. After chronic social defat, HR rats have decreased hippocampal global H3 and H2B acetylation, whereas LR rats have increased H3 acetylation. Both groups showed equivalent decreases in H4 acetylation. Repeated electroconvulsive seizures (ECS), which induce a robust antidepressant effect, regulates H3 and H4 acetylation at Bdnf, c-Fos, and Creb promoters in a time-dependent manner that correlates with gene expression changes. Downregulation of c-Fos was linked to reduced H4 acetylation whereas sustained induction of Bdnf was linked to increased H3 acetylation24. Potentially H3 and H4 acetylation differentially modulate depression-like states in HPC further highlighting the complexity of histone mechanisms in depression.

Histone acetylation in the amygdala (AMY; see Figure 1B, Figure 2) is also implicated in the expression of depressive-like behaviors after chronic social defeat. H3K14 acetylation is transiently increased in AMY after social defeat but is not persistently changed25. HDAC inhibition by intra-AMY MS275 reverses social avoidance but not sucrose preference deficits, suggesting that AMY and HPC histone acetylation may regulate different aspects of depression-like behavior. Chronic unpredictable stress in rats reduced Hdac5 expression in the AMY central nucleus26 and acute, but not chronic, defeat transiently decreased AMY H3 acetylation27. Clearly more work is needed to fully understand the significance of AMY histone acetylation in depression.

Data on the role of histone acetylation in depression in prefrontal cortex (PFC; see Figure 1B) is similarly scarce. Although some studies report no global change in acetylation levels25; 27, conflicting reports suggest that social defeat stress increases global H3 acetylation in PFC28 although this study did not differentiate between mice that are susceptible versus resilient to defeat stress making the significance of this regulation difficult to interpret. A recent study found that rats less resilient to chronic social defeat stress had increased levels of H3K18 acetylation in PFC29. At this point, the lack of data documenting effects of manipulating histone acetylation in PFC prohibits a clearer understanding of the importance of potential stress-induced acetylation changes in depression.

In summary, histone acetylation is robustly regulated by chronic stress in multiple brain regions however the significance of these changes is region-specific. Existing data suggest that, in general, increased histone acetylation, which would favor an open chromatin conformation and increased transcription, is antidepressant. More work is needed to understand how histone acetylation changes regulate expression of specific gene targets implicated in depression.

Histone Methylation

Chronic social defeat stress robustly decreases global levels of H3K9me2 in NAc, a repressive histone modification (see Figure 2), with the coincident downregulation of the histone methyltransferases G9a and G9a-like protein which catalyze this mark22. Overexpression of G9a in NAc is antidepressant22 and increased H3K9me2 at specific gene promoters is implicated in the antidepressant effect of fluoxetine30. Indeed, chronic exposure to fluoxetine reduces Camkii expression in NAc by reducing H3Ac and increasing H3K3me2 levels at the Camkiia promoter in NAc. Interestingly, these effects are found in the NAc of depressed humans exposed to antidepressants suggesting that the stress-induced loss of repressive methylation is maladaptive and that the therapeutic effects of antidepressant drugs may act via the reinstatement of these marks at specific gene loci. One gene which illustrates this mode of regulation is Ras. Reduced H3K9me2 at this gene in the NAc of susceptible mice results in increased Ras expression, induction of ERK signaling and, ultimately, CREB activation which induces depression-like behavior22.

Another repressive histone mark, H3K27me3, is increased upstream to the promoter of the Rac1 gene in susceptible mice and this is associated with a sustained reduction in transcript expression that influences characteristic dendritic spine changes in defeated mice31. These findings are corroborated in humans as H3K27me3 levels are inversely correlated with Rac1 expression, which is also decreased in NAc of depression patients31. As well, susceptible mice exhibit decreased expression of Mll and Lsd1, the methyltransferase and demethylase of H3K4, respectively, although no global changes in H3K4 methylation are apparent22.

The observed decreases in H3K9me2 in NAc would be expected to mediate a more permissive transcriptional state similar to the effect of the global increases in H3 acetylation described above. Curiously, however, manipulations that decrease repressive methylation induce susceptibility whereas manipulations that increase acetylation induce resilience. To reconcile and integrate these findings, genome-wide approaches are required to examine regulation of histone modifications at specific gene loci to understand the precise coordinated regulation of depression-related target genes. ChIP-chip analysis (chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by genome-wide promoter microarrays) examined stress-induced redistribution of H3K9me2 and H3K27me2 in NAc of mice subjected to chronic social defeat or protracted social isolation. Significant and dynamic changes in repressive histone methylation were observed in upstream regulatory regions in both models with more genes evidencing increased H3 methylation. Interestingly approximately 20% of genes were similarly regulated in both models32. The genome-wide finding of increased H3 methylation opposes the finding of reduced global levels of H3K9me2 in NAc of susceptible mice22, further highlighting the requirement for more refined analytical approaches that target histone modifications at specific genomic loci.

Stress also regulates histone methylation in the HPC in a complex time dependent manner33. For instance, acute and sub-chronic restraint stress increases global H3K27me3 levels, an effect that returns to basal levels with chronic restraint stress. Moreover, H3K9me1 is decreased after acute stress and these changes are not evident after more prolonged stress. In addition, sub-chronic stress increases global H3K4me3 levels whereas chronic stress decreases levels of this same mark and this decrease is reversed by antidepressant treatment. Potentially these temporal patterns of histone methylation may reflect different processes of initial stress adaptation subsiding into eventual maladaptation with sustained stress. However, experimental manipulations of such modifications are needed to interpret the functional consequences of these adaptations. Acute stress also increases H3K9me3 levels at transposable elements which may be important in limiting potential genomic instability34. Whole forebrain overexpression of Setdb1, a histone methyltransferase that catalyzes H3K9me3, reduced depression-like behavior35, suggesting that the increase in H3K9me3 after acute stress may represent an adaptive response.

Aside from the few examples cited above, human postmortem studies examining histone modifications in depression are sparse. Elevated levels of H3K4me3 were reported at the synapsin gene family. These changes associate with higher expression of SYN2 in the PFC36. In addition, contrasting chromatin profiles were found in brains from bipolar disorder cases suggesting that these changes may be specific to major depression. Similar changes have been described in the promoter of the polyamine gene OAZ where higher levels of H3K4me3 are associated with higher expression in the PFC of suicide completers37.

Consistent with evidence from animal models, postmortem studies in human brains suggest that antidepressants promote open chromatin structure by decreasing H3K27me3 levels at certain BDNF promoters in PFC of a depression sample38. Follow up studies in peripheral blood revealed higher peripheral BDNF expression in treatment responders compared to non-responders, with H3K27me3 levels being inversely correlated with both BDNF IV expression levels and with symptom severity39. Decreased expression of the tyrosine receptor kinase B (TRKB), which is activated by BDNF, in the PFC of depressed cases is also associated with an enrichment of H3K27me3 levels in the promoter of both TRKB and its astrocytic variant, TRKB.T140; 41. The elevated H3K27me3 levels associate with changes in DNA methylation in the promoter suggesting the presence of dual epigenetic control over TRKB.T1 expression, as reported for many genes in simpler systems. In addition, mice overexpressing TRKB.T1 are more susceptible to chronic social stress than wild type mice42 suggesting that epigenetic changes at the TRKB.T1 promoter could define the vulnerability to chronic social stress and the development of depression.

Chromatin remodeling in depression

Very little is known concerning the role of chromatin remodeling complexes in depression. Chromatin remodeling complexes use the energy of ATP hydrolysis to alter the packing state of chromatin and work in concert with chromatin modifying enzymes to direct nucleosomal dynamics. Preliminary data suggest that chronic social defeat regulates the expression levels of several families of chromatin remodelers in the NAc, including the ISWI family, and enhancing ISWI remodeling complexes in NAc controls susceptibility to social defeat43. As our understanding of these molecules as well as their functional role evolves, more work will be needed to uncover the precise nature of their impact on behavioral regulation induced by stress in the context of depression.

DNA methylation

In addition to the chromatin modifications described above, a growing body of evidence supports a role for DNA methylation in mediating the impact of stress. DNA methylation is a relatively stable epigenetic mark and thus an interesting candidate mechanism for sustained stress-induced susceptibility to depression. Several of these alterations have been described in different animal models and more recently in human brain.

Chronic social defeat stress increases transcript levels of the de novo DNA methyltransferase Dnmt3a in NAc. Overexpressing Dnmt3a in NAc increases depression-like behavior after sub-maximal social defeat and intra-NAc infusion of a DNMT inhibitor, RG108, reverses defeat induced social avoidance44. DNMT3a activity is generally associated with transcriptional repression suggesting that susceptibility may associate with downregulation of transcriptional expression in NAc. Genome-wide analysis of DNA methylation will be important in establishing the precise mechanisms of this epigenetic modification in defeat-induced susceptibility. DNA methylation in NAc may play a role in regulation of glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (Gdnf)20. Chronic unpredictable stress increases Gdnf expression in NAc of a stress-sensitive mouse line (BALB/C) but increases Gdnf expression in a more resilient line (C57BL/6). Although DNA methylation and MeCP2 (methyl CpG binding protein 2) binding was increased at the Gdnf promoter in NAc of both mouse lines, MeCP2 complexes with different proteins in the two lines. In the susceptible mouse line, MeCP2 reportedly interacts with HDAC2 to decrease H3 acetylation and repress Gdnf transcription, while in the resilient mouse line MeCP2 associates with the transcriptional activator CREB to facilitate transcription. The authors suggest that these differences are mediated by differing patterns of methylation at the Gdnf promoter although more work is required to confirm this and elucidate its underlying mechanisms.

DNA methylation is implicated in the regulation of corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN)26; 45 (see Figure 1A). CRF is a critical regulator of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA)-axis activation and other stress actions in the brain. CRF is increased in the PVN of mice that are susceptible to social defeat and this is accompanied by decreased DNA methylation at the Crf promoter. Both effects are reversed by chronic imipramine treatment45. DNA methylation is also increased at the Crf promoter in the PVN of female rats subjected to chronic unpredictable stress, suggesting that DNA methylation may play a role in determining sex-specific regulation of HPA-axis function26. Knockout of Mecp2 in PVN results in an exaggerated physiological stress response, however, the precise mechanism of MeCP2 action remains to be fully elucidated46.

Flinders Sensitive Line rats, a model of genetic susceptibility to depression, exhibit elevated DNA methylation at the P11 promoter which is reduced by escitalopram treatment47. The significance of these findings lies in the fact that P11 is known to interact with serotonin receptors and decreased levels of P11 in certain brain regions are associated with depression-like behavior in mice and humans48; 49; 50. Additionally, chromatin remodeling factor SMARCA3 is a target of the p11 complex and is required for neurogenesis and behavioral responses induced by fluoxetine treatment, indicating interactions between epigenetic states51.

In addition to the effects mentioned above, exposure to aggressive mothers and traumatic stress in rats decrease the expression of Bdnf transcripts III and IV in the HPC and PFC52; 53. These effects are associated with alteration of DNA methylation patterns in distinct regions of the HPC53.

The studies elaborated above highlight epigenetic modifications targeted toward specific genes frequently associated with behavioral alterations. However, it is clear that stress effects are not restricted to a small number of candidate genes. Genome-wide studies mapping DNA methylation alterations induced by stress are lacking in animals. A series of recent genome-wide studies addressing this issue in humans in the context of early life adversity are discussed below. Furthermore, analysis of PFC of psychotic and bipolar cases found numerous sites of differential DNA methylation that were enriched in various functions such as glutamatergic and GABAergic neurotransmission, brain development, and response to stress54. Importantly, these studies compared different tissues (blood versus brain) and brain regions (HPC versus PFC) and globally suggest that stress-induced epigenetic adaptations are region-specific but also cell-type specific, consistent with the emerging notion of epigenetic heterogeneity across tissues55 and cell types56; 57.

In summary, experiments to date have identified stress-induced increases in DNA methylation at a small number of genic loci. Based on the current literature, chronic stress would appear to favor increased DNA methylation and transcriptional repression. However, genome-wide approaches will be very important in identifying the global DNA-methylation “foot-print” and the transcriptional consequences in stress models in animals and in human depression.

Non-coding RNAs in depression

A relatively novel area of research concerns the regulation of miRNAs by stress and antidepressant treatments. miRNAs are posttranscriptional regulators that bind to complementary sequences in the 3′ UTR of their target mRNAs to repress translation or alter mRNA stability58. While still in its infancy, this area of research has the promise to identify important mechanisms through which stress and antidepressants exert their effects.

Microarray analysis of PFC and HPC following acute or repeated restraint stress in mice revealed stress induced changes in miRNA expression profiles. Following acute restraint, let-7a, miR-9, and miR 26-a/b expression was increased in the PFC but not in the HPC, while no change was reported after repeated restraint59. Contrasting results showed elevated expression of let-7a-1 in AMY after acute and chronic stress. In addition, miR-376b and miR-208 were both increased following acute or chronic stress, whereas miR-9-1 decreased in both conditions in HPC60. Other reports implicate miRNAs in the post-transcriptional regulation of Gr (glucocorticoid receptor; Nr3c1). Compared to Sprague-Dawley rats, F344 stress-sensitive rats have lower GR protein but not mRNA levels in the PVN and corresponding increases in miR-18a levels. Overexpression of miR-18a downregulates GR protein levels in cultured neurons61 suggesting that the exaggerated HPA stress response in F344 rats may be mediated by miR-18a regulation of GR translation. Interestingly, in AMY, acute stress induced expression of several miRNAs is implicated in regulation of anxiety through effects on mineralocorticoid receptor and corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 1 (Crfr1) expression62; 63. A significant downregulation of several miRNAs has been reported in HPC of rats that do not develop learned helplessness (LH) following inescapable foot shock compared to LH rats64. LH is a model that is often used to mimic certain symptoms of depression65. These effects coincide with drastic changes in HPC gene expression66 and are believed to represent a potential coping mechanism that allows the development of physiological responses to overcome the effects of stress.

miRNAs may also be therapeutic targets for mood stabilizers. A screening for miRNAs targeted by lithium and valproic acid in rat HPC identified several candidates, among which nine were common to both treatments and are predicted to target genes frequently associated with bipolar disorder. Moreover, lithium was shown to regulate the immobilization stress-induced alteration in HPC miR-34c and AMY miR-15a levels but only in a stress-specific fashion67. Chronic fluoxetine treatment in mice increases miR-16 levels in serotonergic raphe nuclei which downregulates serotonin transporter (Sert) levels, thus altering 5-HT activity in the raphe68. Intra-raphe administration of fluoxetine induced the release of S100β, a known inhibitor of miR-16. Via the reciprocal connections between dorsal raphe and locus coeruleus (LC), S100β is believed to migrate to noradrenergic neurons in the LC and decrease expression of miR-16. By decreasing miR-16 in the LC, S100β turned on the expression of serotonergic functions in noradrenergic neurons. Moreover, intra-raphe and -LC miR-16 administration alleviated the behavioral deficits induced by 6 weeks of chronic unpredictable stress suggesting that the therapeutic effects of fluoxetine may be mediated via its actions on miRNA expression in the brain68.

Recent findings also support the involvement of miRNA in human depression. For instance, 21 miRNAs were downregulated in PFC of depressed suicide cases69. The miRNAs identified in this study were predicted to bind several targets among which DNMT3B was shown to be highly upregulated, an effect consistent with findings from previous postmortem studies in depression70 and with several reports of stress-induced hypermethylation in the context of depression (see below). Interestingly, the authors suggest the existence of a highly interconnected network of miRNAs specific to depression which may underlie PFC hypoactivity. Microarray screening of known miRNAs in brain found significant enrichment of miR-185 and miR-491-3p in the brains of depressed suicide cases71. miR-185 is predicted to bind 5 sites in the 3′ UTR of TRKB.T1, the astrocytic variant of TRKB and miR-185 levels were inversely correlated with TRKB.T1, with expression decreased in the PFC of depressed suicide cases40; 71. Luciferase assays confirmed the functional relationship of these two genes.

The above findings suggest the involvement of miRNAs in the pathophysiology of depressive disorders. However, studies are still in their infancy and one key obstacle is the lack of powerful prediction tools for miRNA targets. Indeed, most miRNAs are predicted to, and most likely do, bind several genes, making it difficult to predict the impact of one miRNA on stress-induced behavioral alterations.

Epigenetics and developmental vulnerability to depression

Early life exposures to stress may have life-long impact on neuropsychiatric states and behavior via epigenetic mechanisms. Adults who experienced childhood stress or maltreatment are at significantly greater lifetime risk of a range of mood or other psychiatric disorders72; 73; 74; 75. DNA methylation, post-translational histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs may alter expression of key genes, or may alter their ability to be induced or repressed in response to subsequent environmental perturbations, enhancing vulnerability to psychiatric disorders. This section will highlight research on epigenetic alterations resulting from developmental (in utero, early post-natal, and peri-adolescent) exposures to stress, with consequences for depression and and related disorders.

Early life adversity has been modeled in rodents and non-human primates using maternal separation (MS) or maternal deprivation. These paradigms involve removing offspring from the mother for 2–8 hours per day prior to weaning, and lead to robust stress responses among offspring. Natural variations in maternal care likewise associate with differential stress responses among adult offspring. Rats reared by dams that display low frequencies of offspring licking and grooming (LG) exhibit heightened stress sensitivity and elevated HPA activity in adulthood compared to those reared by dams that groom their offspring with high frequency76. Research in the last decade has shown that epigenetic alterations play a role in the enduring effects of early life stress on adult mood disorders.

Histone Modifications

Prenatal Stress

Few studies have explored the effects of prenatal stress on post-translational histone modifications directly. Treatment of adult mice exposed to prenatal stress with valproic acid—which is a non-specific HDAC inhibitor among several additional actions—ameliorate locomotor hyperactivity, deficits in social interaction, prepulse inhibition, and fear conditioning77. However, more work is needed to understand the role of chromatin modifications and chromatin modifying enzymes in both the initial response to, and lasting effects of, prenatal stress.

Postnatal Stress

Postnatal adversity in the form of maternal separation in rodents is associated with broad changes in histone modifying enzymes and post-translational histone modifications. Adult male rats that underwent MS displayed reduced levels of Hdac1 mRNA in PFC, although this molecular phenotype was not observed in infancy or adolescence78. Among Balb/c mice that display enhanced susceptibility to stress (but not among C57Bl/6 mice), MS reduced levels of Hdac 1, 3, 7, 8, and 10 in the forebrain in adulthood, and increased acetylation of histone H4, particularly at H4K1279. Elevated H3 and H4 acetylation was also found in the HPC of juvenile mice immediately after MS80. Adolescent fluoxetine treatment potentiated effects of MS on histone modifications, and co-administration of fluoxetine with an HDAC inhibitor ameliorated both HDAC and behavioral effects of MS79. Not surprisingly, treatment during adolescence with theophylline—which can activate HDACs in addition to its better described action as a phosphodiesterase inhibitor—exacerbated the behavioral effects of MS79. These findings suggest that adolescence may be a relevant period for pharmacological intervention and that it may be possible to erase at least some of the epigenetic signature of early life stress.

Chromatin modifications additionally mediate some of the effects of maternal LG on rat stress responses. Low maternal LG associates with decreased hippocampal H3K9-acetylation at the Gr exon 17 promoter17; 81; 82; 83. These modifications co-localize with changes in DNA methylation and span across large regions of the genome as evidenced by microarray analyses82. The changes are also associated with depressive-like symptoms, reduced gene expression, with promoter hypermethylation. Treatment with the HDAC inhibitor TSA, infused either intracerebroventricularly (ICV) or intra-HPC, reversed the effects of low maternal care on adult H3K9-Ac levels and anxiety-like behavior17; 84.

DNA methylation

Prenatal Stress

Activation of the HPA-axis (see Figure 1A) leads to release of CRF and vasopressin (AVP) from the hypothalamic PVN, release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) from the anterior pituitary, and release of glucocorticoids (cortisol in primates and corticosterone in rodents) from the adrenal gland. Under normal conditions, acute stress is shunted by negative feedback from neurons expressing GR in the brain, such as in the HPC, while chronic stress has been associated with impaired GR feedback and elevated HPA-activity85. The developing fetus is largely protected from maternal glucocorticoids by the enzyme 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (11β-HSD2), which converts active glucocorticoids to their inactive form. However, 10–20% of maternal cortisol is estimated to pass through the placenta to the fetus86. Evidence paradoxically suggests that maternal adversity during pregnancy leads to a suppression of 11β-HSD2 levels and enzymatic activity87; 88 and heightened stress-responses among offspring89; 90. DNA hypermethylation of Hsd11b2 in the placenta and hypomethylation in the fetal hypothalamus consequent to prenatal maternal stress may contribute to long-term alterations in offspring stress programming91.

Persistent changes in DNA methylation have been identified in the brains of adult mice exposed to early prenatal stress92. Within the hypothalamus, early prenatal stress associates with elevated DNA methylation at CpG sites in the NGF1-A binding region of the Gr promoter exon 17, and decreased methylation at CpG sites within the Crf promoter, with no changes in Bdnf methylation92. These alterations occur at specific CpG sites, in specific genes, and in specific brain regions, highlighting both the difficulties in using peripheral tissues to predict meaningful changes within the brain, as well as the need for more precise tools to manipulate epigenetic gene regulation in functional pre-clinical studies.

Hypermethylation in the GR promoter 1F was likewise found in infant cord blood from mothers who experienced depression during the third trimester of pregnancy93; 94, and from mothers reporting intimate partner violence during their pregnancy95. The effects were however not reversed by antidepressant treatment. This suggests that maternal prenatal stress induces specific long-lasting epigenetic alterations affecting GR expression. Altered DNA methylation at the serotonin transporter (SERT, SLC6A4) in offspring cord blood is likewise associated with prenatal maternal depression in the context of a genetic variant within methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, an enzyme required for folate metabolism and generation of methyl groups96. Contrary to these reports, a recent study examined the relationship of maternal depression or other psychiatric diagnosis with DNA methylation across the genome in offspring cord blood and found no association between maternal depression and altered DNA methylation at any site examined97. Modest differences in methylation at CpG sites in two genes (TNFRSF21 and CHRNA2) were associated with maternal antidepressant use.

In addition, elevated levels of Dnmt3a mRNA were found in the placenta (but not hypothalamus or cortex) of rats exposed to in utero stress, while elevated Dnmt1 mRNA was found within the cortex of offspring at gestational day 2091. Mice exposed to prenatal stress had elevated levels of Dnmt3a and Dnmt1 mRNA in the PFC and HPC at birth, and these relative differences persisted at postnatal (PN) day 7, 14, and 6077. Furthermore, prenatal stress induced increased binding of DNMT1 and MeCP2, along with increased 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, within CpG-righ regions of the Reelin and Gad67 promoters, at both PN1 and PN6077.

In sum, existing evidence points to a role of prenatal stress in altering adult vulnerability to depression via altered DNA methylation at specific genes. However, work to date is limited by its focus on a small number of candidate genes. Genome-wide analyses of DNA methylation changes in rodent models of prenatal stress will facilitate comparisons of potential epigenetic biomarkers in peripheral tissue such as cord blood and placenta with epigenetic and gene expression changes in specific brain regions implicated in stress regulation and mood.

Postnatal Stress

Variations in maternal care alter DNA methylation levels in genes thought to be critically involved in behavioral stress responses. The offspring of low LG mothers, as opposed to those raised by high LG dams, exhibit lower hippocampal expression of several variants of GR, including the hippocampal specific variant Gr 1717; 82. This is associated with higher DNA methylation levels in promoter regions, including those overlapping with binding sites for transcription factors (i.e. NGF1A) known to regulate GR expression. However, the impact of maternal care on the establishment of DNA methylation profiles is not targeted to specific genes but rather spreads across large genomic regions. Indeed, microarray analysis of a 6.5 million base-pair region centered on the Gr locus showed that low maternal care induces hundreds of parallel DNA methylation changes co-localized with other chromatin modifications98. These adaptations preferentially affect promoters, as evidenced by the cluster at protocadherin genes, and follow a non-random, discontinuous pattern across large genomic regions98. While it is known that DNA methylation recruits cofactors carrying enzymatic activity toward chromatin structure99, it is still unclear how both DNA methylation and chromatin conformation are co-regulated in the context of stress.

Similar alterations have been reported in the HPC of suicide completers with a history of child abuse. Abused suicide completers exhibit lower expression levels of GR1B, 1C, and 1F compared to non-abused suicides and controls100; 101. These changes are associated with changes in DNA methylation within respective promoters, may interfere with transcription factor binding as evidenced by functional luciferase assays. Furthermore, DNA methylation levels at the GR 1F promoter are positively correlated with childhood sexual abuse severity and number of distinct maltreatment conditions in individuals with major depressive disorders102; 103. Importantly, these alterations appear to be specific to early-life adversity as GR transcriptional modifications found in the brains of depressed patients do not associate with changes in DNA methylation104.

Low maternal care in rats also affects Gad1 and Grm1 expression in the HPC81; 83. Pups raised by low LG mothers show lower Gad1 and Grm1 HPC expression levels associated with promoter hypermethylation and lower levels of H3K9Ac compared to pups raised by high LG dams. This is accompanied by elevated HPC levels of Dnmt1 similar to the elevated levels of Dnmt3a in mice susceptible to chronic social defeat. It is possible that the hypermethylated state found in gene promoters following stress originates from the increase in DNMT levels. Human data support this possibility. For instance, levels of DNMT1 in the brain of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder cases correlates with promoter hypermethylation and lower expression of REELIN and GAD1 genes105; 106; 107; 108; 109. In addition, the expression of all three DNMTs (DNMT1, 3A, and 3B) are altered in limbic and brain stem regions in depressed suicide completers70.

Interactions between early attachment patterns and the methylation state of the SERT promoter in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in Rhesus macaques has also been reported110, suggesting that increased methylation in this genomic region may associate with increased reactivity to stress in maternally deprived, but not in mother-reared, infants. Interestingly, in humans, a significant association has been reported between sexual abuse and overall DNA methylation in different regions of the SERT gene, in transformed lymphoblast cell lines derived from subjects recruited through the Iowa Adoption Study111; 112. Furthermore, DNA methylation patterns in SERT have been associated with the emergence of antisocial personality disorder in adulthood.

Early maternal separation also altered DNA methylation in a known enhancer region for Avp expression in PVN113. Consistent with the observed overexpression of Avp, a sustained hypomethylation state within the Avp enhancer region was characterized in the PVN of stressed mice 6 weeks, 3 months, and 1 year following the stress regimen113. A similar overexpression was also reported in stressed mice at 10 days, although no methylation differences were observed in the Avp enhancer, revealing a dual regulatory mode depending on the timing of the stress. These findings point to the existence of complex mechanisms of transcriptional regulation by DNA methylation in non-promoter regions, highlighting the importance of investigating such mechanisms beyond the traditional promoter-centric focus.

Stress beyond the early neonatal period also leaves an epigenetic mark. Three weeks of adolescent isolation stress in a Disc1 mutant mouse induced mood-related behavioral alterations accompanied by hypermethylation of the tyrosine hydroxylase (Th) gene promoter in the VTA of mice114. However, Th promoter hypermethylation was observed in response to both Disc1 mutations and adolescent isolation stress, and these effects were additive although only in VTA dopamine cells projecting to frontal cortex and not in dopamine cells projecting to NAc114. Hypermethylation was observed at the end of the three-week adolescent isolation, and sustained 12 weeks later in the absence of further stress. Th promoter hypermethylation was rescued by treatment with the GR antagonist RU38486, suggesting that GR-mediation of the stress response in this chronic adolescent stress paradigm underlies stress-induced alterations in the mesocortical reward pathway114.

DNA methylation is also altered by extreme childhood adversity in the form of abuse. Experience of maternal maltreatment in rats (tramping, dragging, rough handling) leads to chronic hypomethylation at the Bdnf exon IX gene promoter in the PFC52. These effects are at least partially rescued by ICV treatment for seven days with zebularine, a DNA methylation inhibitor. One recent human study assessed the impact of child abuse on genome-wide DNA methylation signatures in gene promoters115. HPC DNA methylation patterns were compared between suicide completers with a severe history of child abuse (sexual or physical) and healthy controls, and hundreds of differentially methylated sites were identified. Interestingly, DNA methylation levels in gene promoters were inversely correlated with gene expression at a genome-wide level, supporting the globally repressive role of DNA methylation at promoters, as reported by other groups54; 116. Similar observations have been made in suicide completers117. The impact of abuse becomes obvious when assessing the gene functions enriched with differential methylation: differential methylation in the abused suicide group is enriched in genes related to cellular plasticity, while learning and memory genes were particularly affected in suicide. This suggests that intense early-life adversity may induce long-lasting alterations that may not be found in the brain of suicide completers not exposed to early-life adversity. Importantly, the changes in DNA methylation levels reported in these studies occurred in specific cell types as most of the methylation changes were found exclusively in neuronal DNA.

In line with the previous results, these studies suggest that the experience of stress, whether during early-life or adulthood, have profound, genome-wide epigenetic consequences in the brain and peripheral tissues. Indeed, modifications of DNA methylation signatures in different regions of the brain are a plausible mechanism to explain how stress can induce behavioral alterations. Methylation signatures in peripheral tissues may provide a biomarker of stress exposure and vulnerability, however, it is highly implausible that the same genes regulated within a particular brain region will be similar affected in blood. It will be interesting in future studies to better correlate regulation of DNA methylation genome-wide between blood and brain and across numerous brain regions of animal models and to translate such findings to humans.

Non-coding RNAs in depression

Prenatal Stress

Several miRNAs were down- (miR-145, miR-151, miR-425) or up- (miR-103, miR-219-2-3p, miR-98, miR-323) regulated in whole brain tissue of neonatal rats exposed to gestational stress from E12-18118. Targets of these miRNAs include genes implicated in neurotransmission, stress response, and disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. For example, prenatal stress increases levels of GPM6A, a neuronal glycoprotein involved in filopodium extension, in the HPC and PFC of male mice at both PN28 and PN60119. This is accompanied by enhanced miR-133b, Dnmt3a, and Mecp2 levels and with alterations in methylation patterns within two CpG islands of the Gpm6a gene119. Furthermore, miR-133b downregulated Gpm6a levels and reduced neurite extensions in cultured HPC neurons, demonstrating functional consequences of miR-133b dysregulation by prenatal stress.

Altered miRNA expression was also found in the second generation of animals exposed to prenatal stress, promoting miRNAs as one potential epigenetic mechanism of trans-generational stress effects. First generation male mice exposed to first trimester gestational stress have a demasculinized stress response, and their second generation male offspring have reduced levels of miR-322, miR-574, and miR-873 that are similar to patterns among control females120. Similarly, altered microRNA patterns were observed after neonatal treatment with the aromatase inhibitor formasetane, implicating testosterone in the regulation of miRNAs and organization of sexually dimorphic brain and behavior120. Similar effects of prenatal stress on miRNA patterns have yet to be observed in peripheral or central human tissue.

Postnatal stress

Maternal separation in rats is known to induce the expression of the repressor element-1 silencing transcription factor 4 (Rest4)121 in PFC, the expression of which is believed to influence the processing of several miRNAs including miR--9-1, -9-3, -212, -29a, 124-1, and -132122. Among these miRNAs, miR-132 and -124 have CREB binding sites within their respective promoters and their expression can be induced by BDNF123. Overexpressing Bdnf in cultured neurons increases miR-132, which upregulates several glutamate receptors subunits (NMDA NA2A and 2B subunits and AMPA GluA1 subunit) and neurite outgrowth, potentially by decreasing levels of the GTPase-activating protein, p250GAP124; 125. CREB can also regulate miR-124 at the synapse through 5-HT-induced long-term facilitation and CREB de-repression123. Interestingly, treatment with the MAPK/ERK pathway inhibitor U0126, suppressed BDNF induction of miR-132, suggesting that MAPK/ERK may represent another pathway besides CREB by which BDNF upregulates miR-132. Moreover, BDNF increases the expression of DICER, one of the key members of the miRNA processing machinery, increasing mature miRNA levels and inducing RNA processing bodies in neurons126. Together, these findings suggest that miRNAs may be affected by stress via altered BDNF signaling.

EPIGENETICS AND ADDICTION

In rodents, addiction-relevant transcriptional regulation is studied by exposing animals to drugs of abuse. Most commonly this is experimenter-administered drug exposure, and it should be noted that, although many effects are recapitulated in self-administration models, clearly some mechanisms are distinct. More work is needed to examine the generalizability of epigenetic mechanisms revealed by passive drug exposure paradigms to more rigorous drug self administration models. The following sections will review epigenetic regulation in response to exposure to several common drugs of abuse.

Histone modifications in addiction

Histone acetylation

Global H3 and H4 acetylation levels in the NAc, a brain region critical for drug reward as noted above, are increased after a single exposure to cocaine and remain elevated with chronic administration127; 128; 129. The specific K residues at which cocaine induces acetylation have not been documented. The functional significance of elevated histone acetylation in regulating the rewarding effects of cocaine is complex and manipulations of acetylation exert variable effects on drug responses. While manipulations that acutely increase histone acetylation generally increase behavioral responses to cocaine, more sustained increases in acetylation attenuate cocaine’s rewarding effects. The opposing effect of long-term increases in histone acetylation may be explained by compensatory increases in repressive histone methylation130. Cocaine regulation of the HAT CREB binding protein (CBP) and HDAC5 are implicated in HDAC regulation of cocaine’s behavioral effects21; 131; 132; 133. CBP heterozygous knockout mice exhibit attenuated locomotor and reward-related responses to cocaine131; 132, while homozygous HDAC5 knockout mice are hypersensitive to cocaine and overexpression of HDAC4 or HDAC5 in NAc attenuates cocaine-elicited behaviors21; 127; 134. In contrast, NAc-specific deletion of HDAC1 (but not HDAC2 or 3) attenuates cocaine responses via induction of G9a and H3K9me2130.

In many instances, cocaine or other stimulant-induced alterations in histone acetylation at candidate gene loci in NAc correlate with gene expression. Studies of candidate genes suggest that with the progression from acute to chronic drug exposure, the gene targets associated with acetylation changes shift from immediate early genes to a later enrichment of genes implicated in long-term plasticity (e.g. Cdk5, Bdnf, Camkiia). Acute, but not chronic, cocaine increases H4 acetylation at the c-Fos promoter127; 135. In contrast, chronic, but not acute, cocaine increased H3 acetylation at the Bdnf, Cdk5, and Camkiia promoters in NAc30; 127; 134. Genome-wide studies of total H3 and H4 acetylation using ChIP-chip found both hyper- and hypo-acetylation at many gene promoter regions that were largely non-overlapping between the marks. Interestingly, although altered histone acetylation associated with expected regulation of mRNA for many genes, expression levels of most genes did not correlate with acetylation changes. This highlights the importance of considering individual histone modifications within the context of broader chromatin regulation136. Two interesting targets identified by this genome-wide approach are Sirt1 and Sirt2, class III HDACs, which are induced in NAc by chronic cocaine. Overexpression of Sirt1 or Sirt2 in NAc enhances cocaine reward and NAc-specific knockdown of Sirt1 has the opposite effect. These actions of SIRT1 are mediated via the regulation of numerous synaptic proteins and the associated induction of dendritic spines137.

In contrast to cocaine, far less is known about the role of histone acetylation in mediating the rewarding effects of other drugs of abuse. Opiate regulation of several target genes correlates with altered histone acetylation138; 139 and inhibition of HDAC activity in NAc potentiates the rewarding effects of opiates140. Similar to cocaine, opiates induce SIRT1, although not SIRT2, in NAc and overexpression of either Sirt1 or Sirt2 in this region increases opiate reward137. Ethanol increases global H3 and H4 acetylation in PFC and AMY, increases CBP in AMY, and decreases HDAC activity in brain and these effects are associated with increased ethanol reward141; 142; 143; 144. However, ethanol withdrawal is associated with increased HDAC activity and decreased H3 and H4 acetylation, which was rescued by systemic treatment with the HDAC inhibitor TSA and also prevented withdrawal-associated anxiety144. Much further work is needed to characterize the actions of these other drugs, most importantly genome-wide assessments of histone acetylation.

Histone methylation

Much of our understanding of the role of histone methylation in drug addiction is informed by recent studies of two repressive histone methylation signatures, H3K9me2 and H3K9me3, both of which are decreased by cocaine and opiates in mouse NAc, effects recapitulated in human addicts145; 140. Both cocaine and morphine decrease expression of G9a and GLP, two HMTs that catalyze H3K9me2. Ethanol also decreases G9a in cultured cortical neurons146. Manipulations of G9a in NAc bi-directionally control behavioral responses to cocaine and opiates. Increasing G9a function inhibits and decreasing G9a enhances drug-elicited behaviors145; 147. Cocaine-induced downregulation of G9a plays a central role in the characteristic increases in dendritic arborizations and synaptic protein expression that is associated with cocaine exposure145.

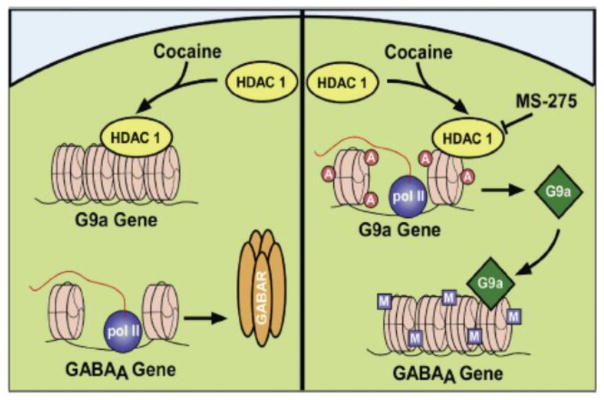

Regulation of G9a and associated alterations in H3K9me2 levels appear especially relevant to understanding the prolonged effects of cocaine. Chronic cocaine followed by one month withdrawal decreases H3K9me2 at the Fosb gene and this is associated with increased inducibility of the Fosb gene148. Prior history of cocaine exposure increases susceptibility to subsequent stress and reduction of G9a in NAc by cocaine mediates this cross sensitization22. G9a may play a critical role in homeostatic control of epigenetic regulatory mechanisms. Extended HDAC inhibition in NAc attenuates cocaine effects, as stated above, and this is mediated via G9a induction130 (see Figure 3). G9a exerts this effect via complex regulation of certain GABAA subunits in this brain region. Thus, while chronic cocaine or extended HDAC inhibition individually increases expression of GABAA subunits in NAc, chronic cocaine in combination with extended HDAC inhibition paradoxically attenuates the behavioral effects of cocaine and inhibits expression of these subunits. The mechanism of this suppression involves induction of G9a and subsequent increased H3K9me2 binding at specific GABAA subunit genes. In this instance, G9a induction may be triggered in response to excessive hyperacetylation induced by combined HDAC inhibition and cocaine as a homeostatic brake130.

Figure 3. Regulation of GABAA receptor subunit gene expression in NAc through crosstalk between histone acetylation and repressive methylation.

Repeated cocaine targets HDAC1 to the G9a/GLP (G9a-like protein) promoters, leading to decreased G9a/GLP gene expression and decreased binding of these histone methyltransferases (HMTs) at the promoters of certain GABAA receptor subunit genes. The resulting decreased repressive histone methylation (reduced H3K9me2) allows for increased transcription of the GABAA receptor subunits and increased inhibitory tone in the NAc. Chronic cocaine plus chronic intra-NAc infusion of MS275, by inhibiting HDAC1, promotes excessive histone acetylation at several genes, including G9a/GLP, and leads to the induction of G9a/GLP gene expression. These HMTs then catalyze increased H3K9me2 at GABAA receptor subunit gene promoters to block cocaine-induced transcriptional activation of the GABAA subunits and increased inhibitory tone. From Ref 130, with permission.

Genome-wide analysis of H3K9me2 expression by ChIP-chip or more sensitive ChIP-seq (ChIP followed by next generation sequencing) suggests that, although patterns of expression after cocaine or opiates are associated with changes in gene expression, this single mark—as with measures of histone acetylation noted earlier—is not predictive of gene expression changes135; 147; 149. ChIP-seq of H3K9me3 in NAc shows that this mark is almost exclusively located in non-genic regions, with such binding reduced by chronic cocaine at many sites. Of particular interest, cocaine reduces H3K9me3 binding at several repetitive elements, including long-interspersed nuclear element-1 (Line1), the expression of which is decreased by cocaine150. The next important challenge will be to understand cell-type specific regulation. Recent findings suggest that cocaine regulation of H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 follows a cell-type specific time course151. Interestingly, although cocaine represses G9a expression in both D1 and D2 medium spiny neurons (MSNs) in NAc, cell-type specific manipulation suggest that G9a exerts opposing effects152. Developmental knockdown of G9a in D1 MSNs suppresses behavioral responses to cocaine, conversely, G9a knockdown in D2 MSNs enhances cocaine’s effects. Moreover, overexpression of G9a in D2 MSNs of adult mice attenuates cocaine reward but has no effect in D1 MSNs, suggesting that G9a may regulate cocaine reward primarily through effects on D2 MSNs.

Finally, advances in designer-transcription factors are allowing for unprecedented precision in dissecting the regulatory influence of specific histone marks. Recent work using zinc finger proteins to specifically target G9a to the FosB promoter establishes a direct causal link between increased H3K9me2 at this specific locus and transcriptional repression of the FosB as well as attenuated locomotor responses to cocaine. In contrast, targeting of the transcriptional-activator p65 to the same locus increases H3 acetylation, increases FosB transcription, and enhances cocaine responses153.

Other histone and related mechanisms

Far less is known about other histone modifications and their role in drug reward. Chronic cocaine alters histone phosphorylation154; 155 and arginine methylation156. A recent paper established a critical role for poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation. Chronic cocaine induces poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) in the NAc and this upregulation potentiates behavioral responses to cocaine. ChIP-seq revealed cocaine-induced increases in PARP-1 binding across the genome and this correlated with increased gene expression measured by RNA-seq157.

As with depression, very little is known concerning the role of chromatin remodeling complexes in addiction. Chromatin remodeling likely contributes to cocaine-induced expansion of euchromatin. Recent work suggests that cocaine, like chronic social defeat, regulates the expression of the ISWI family of chromatin remodelers and that this upregulation may be important for altered nucleosome spacing156.

Studies of drug-induced regulation of histone post-translational modifications have enriched our understanding of the complex interplay of several different types of modifications149. Exposure to drugs of abuse may initially increase histone acetylation, favoring transcriptional activation. With sustained drug exposure, increases in histone acetylation act to induce certain histone methyltransferases and subsequently increase repressive histone methylation, curtailing the initial period of excessive transcriptional activation. Thus, it is critical to identify the interactions among diverse histone modifications to fully characterize the transcriptional alterations induced by drugs of abuse.

DNA methylation in addiction

In comparison to histone methylation, far less is known concerning how DNA methylation influences molecular and behavioral adaptations in addiction. Acute exposure to cocaine inhibits the expression of both maintenance and de novo DNMTs, Dnmt1 and Dnmt3a/b, in the NAc44; 158. However, Dnmt3a expression is actually increased after chronic cocaine exposure with extended withdrawal. NAc-specific deletion or pharmacological inhibition of DNMT3a in NAc, which reduces global DNA methylation levels, potentiates the rewarding effects of cocaine suggesting that DNMT3a and DNA methylation negatively regulated cocaine reward. Accordingly, viral-mediated overexpression of Dnmt3a, but not Dnmt1, in NAc reduces cocaine conditioned place preference. Paradoxically, Dnmt3a overexpression induced increases in thin spines comparable to increases observed after cocaine44. This finding suggests that DNMT3a may not simply repress gene transcription. Consistent with this, inhibition of DNMT activity has been reported to block histone acetylation159.

Chronic extended access cocaine self-administration increases methyl-CpG binding protein in the dorsal striatum160. Knockdown of MeCP2 in the dorsal striatum suppresses cocaine self-administration specifically in an extended availability paradigm. In contrast, MeCP2 knockdown in NAc enhances behavioral responses to amphetamine, while MeCP2 overexpression attenuates amphetamine reward161. More work is needed to understand the complexities of MeCP2 regulation in addiction models. It is important to note that MeCP2 and DNMTs may not exclusively mediate their reported effects on drug reward via DNA methylation, such as through recruitment of HDACs162 and H3K9 methylation163. Several studies have reported cocaine-induced DNA methylation changes at candidate genes158; 164; 165, however, genome-wide studies of DNA methylation are needed to more fully and directly assess the role of DNA methylation in addiction.

Recent work suggests that cocaine also decreases expression of Tet1 in NAc. TET1 is an enzyme that catalyzes 5-methyl cytosine oxidation to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmc), which has been viewed as a transient epigenetic state between methylated and unmethylated cytosines. Overexpression of Tet1 attenuates behavioral responses to cocaine. Genome-wide 5hmc capture and deep sequencing combined with RNA-seq found robust regulation of 5hmc at distal enhancer regions and within coding regions of genes that are induced in response to a cocaine challenge149. These findings suggest that 5hmc may be a stable epigenetic mark induced by cocaine although more work is needed.

Non-coding RNAs in addiction

Many studies report up- and downregulation of several miRNAs by drugs of abuse. Next generation sequencing recently identified tens of miRNAs that are altered in NAc whole extracts and in purified striatal postsynaptic densities after chronic cocaine166. Among these, cocaine increased expression of miR-181a and decreased expression of miR-124 and let-7d in rat striatum126; 167; 168; 169; 170. Moreover manipulations that recapitulate these effects also enhanced behavioral responses to cocaine. miR212 is induced in the rat dorsal striatum by cocaine self-administration and this induction suppresses cocaine intake171. The antagonistic effect of miR212 on cocaine self-administration appears to be mediated through indirect activation of the transcription factor CREB, known to antagonize cocaine reward5. Finally, chronic ethanol suppressed BK channel expression through induction of miR9 in both the striatum and preoptic area of the hypothalamus172. Knockout of argonaut-2 (Ago2), which is required for miRNA processing and mRNA silencing, from D2 neurons in striatum reduced cocaine self-administration, further supporting the importance of miRNAs in cocaine action169. This is a promising field of research and more work is needed to fully explore the population of miRNAs regulated by drugs of abuse and to define mRNA targets and functional consequences for each.

Epigenetics and developmental vulnerability to addiction

Developmental exposure to drugs of abuse results in altered epigenetic states in the brain. In some cases, clear links to addiction vulnerability exist, while in other cases the ultimate effect on addiction or other psychiatric disorders remains to be elucidated.

Histone Modifications

Prenatal Exposure

Fetal alcohol exposure can result in impaired motor coordination and balance and has been linked to alterations in cerebellar development. Guo and colleagues173 identified reduced acetylation of H3 and H4 in the cerebellum of rats exposed to ethanol in the third trimester-equivalent of human pregnancy (rat PN2-12). Reduced histone acetylation may be mediated by reduced CBP in this region after developmental ethanol173. More research is needed to understand whether deficits in H3 and H4 acetylation similarly contribute to deficits in learning, cognition, judgment, attention, and social behavior associated with fetal alcohol exposure.

Developmental Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) exposure enhances rat behavioral preference for THC in adulthood174, which may be mediated by altered dopamine receptor levels. Reduced D2 (DRD2) expression is observed in adult drug abusers, raising the question of causality or consequence. Human fetal exposure to cannabis also decreased D2 expression levels in NAc, suggesting that downregulated D2 levels may be both a consequence of exposure and predate drug abuse vulnerability174. Rats prenatally exposed to THC show D2 downregulation in association with increased H3K9me2 and decreased H3K4me3 binding at the Drd2 gene, consistent with the change in receptor expression174.

Postnatal Exposure

Altered histone modifications may underlie the enhanced vulnerability to alcohol and other drugs found during the peri-adolescent period. Binge-like intermittent adolescent alcohol exposure alters acetylation of H3 and H4 in PFC, NAc, and dorsal striatum of rats and is associated with downregulation of D2 receptors in the PFC175. ChIP has not been used to confirm reduced H3 and H4 at the Drd2 gene locus specifically.s Interestingly, these findings were specific for adolescent, but not adult, ethanol exposure175, indicating enhanced vulnerability to chromatin-modifying effects of alcohol during development.

Cocaine administered to adolescent rats in ascending doses to mimic patterns of drug binging observed in human adolescents resulted in abnormally rapid attention shifting and altered gene expression in the PFC176. Decreased H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 levels accompanied downregulated expression of transcription factors including Egr1/2, Homer1, and Jmjd1a in PFC one day after final cocaine administration176. However, array data also showed upregulation of genes associated with cell adhesion and extracellular matrix not explained directly by altered H3 methylation. Interestingly, expression of fewer genes was altered 24 days after final cocaine administration indicating that persistent behavioral effects may be due to organizational changes and altered connectivity that no longer require sustained changes in gene expression or epigenetic gene regulation.

Adolescent THC exposure has been shown to enhance heroin self-administration and dysregulation of the endogenous opiate system. Adolescent rats exposed to THC have elevated levels of proenkephalin (Penk) mRNA in the NAc, which is associated with decreased H3K9me2 and increased H3K4me3 at the Penk promoter177. Furthermore, overexpression of Penk in the striatum of THC-exposed rats potentiated heroin self-administration, while knockdown of Penk attenuated self-administration. These studies elegantly demonstrate gene-specific regulation by posttranslational histone modifications in the development of drug addiction, rather than global dysregulation of histone modifications or histone modifying enzymes.

DNA methylation

Prenatal Exposure

Altered DNA methylation patterns are implicated in long-term neurological alterations associated with fetal alcohol exposure. Sufficient folate and methyl donors are essential for proper DNA methylation in rapidly dividing cells during embryonic development. Recent evidence in humans shows that chronic alcohol consumption during pregnancy impairs folate transfer from the mother across the placenta to the developing fetus178, although additional research is needed to determine whether alcohol actively downregulates placental folate receptors and transporters. Alcohol also has a direct effect on developing neurons: neuronal stem cells cultured with alcohol for just six hours showed altered patterns of 5-methylcytosine and DNMT1 immunostaining, as well as inhibited differentiation, growth, and migration179. Alcohol-induced alterations in DNA methylation persist past embryonic development, and DNMT activity was increased at weaning180 and alterations in CpG methylation were observed into adulthood in the whole brain of male mice181. These studies are an excellent beginning to understanding the effects of fetal alcohol exposure on gene regulation by DNA methylation. Future studies would benefit from examining more specific genes or gene networks that may be affected by methylation changes, as well as how these patterns change from embryonic development through adulthood, and whether a diet rich in methyl donors (either during fetal development or later in life) is able to rescue some of the effects of fetal alcohol exposure.

Prenatal exposure to cigarette smoke has a small but significant effect on methylation within repetitive DNA elements in human placenta182; 183, buccal epithelium184, and blood samples185. Among the genes aberrantly methylated, BDNF exon 5 was hypermethylated in blood samples taken during adolescence185. Further studies in animal models of prenatal or neonatal cigarette smoke exposure should explore whether DNA methylation at specific genes in these peripheral tissues are predictive of methylation patterns (even if at different genes) within brain regions relevant for cognitive, emotional, social, or rewarding behaviors.

Fetal cocaine exposure during the second and third trimesters of mouse gestation significantly affected CpG methylation in HPC pyramidal neurons of both neonatal (PN3) and juvenile (PN30) offspring186. Interestingly, the patterns of aberrant methylation observed at PN3 were somewhat dissimilar to the patterns observed at PN30 in response to fetal cocaine exposure, which highlights the necessity of longitudinal, tissue-specific studies to better understand long-term epigenetic consequences of in utero drug exposure. However, the relevance of these changes to later addiction liability is unknown.

Postnatal Exposure

Surprisingly little is known about methylation patterns resulting from postnatal exposure to various drugs of abuse. Among weight-restored anorexic patients, smoking (but not malnutrition) was associated with decreased POMC promoter methylation within peripheral monocytes187. However, the degree to which this is relevant for POMC expression or epigenetic regulation within the brain is unknown.

The broad epigenetic changes induced by early life stress may also be relevant to our understanding of sensitivity to drugs of abuse in adulthood. Maternal stress was recently shown to paradoxically increase Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, and Dnmt3b mRNA levels and decrease global DNA methylation levels in the adult NAc, although methylation was increased at promoters of genes potentially relevant to stress or drug behavior including protein phosphatase 1 catalytic subunit (Pp1c) and adenosine A2A receptor (A2ar)188. Maternal separation-induced DNA methylation changes in NAc may underlie enhanced locomotor responses to acute cocaine treatment in adulthood188. Further studies are needed to understand the role of epigenetics in the cross-sensitization of early life stress and drug sensitivity.

Non-coding RNAs

Prenatal Exposure

Persistent effects of developmental drug exposure are additionally mediated by miRNAs. Levels of miRNAs including miR-140-3 were reduced by ethanol and dose-dependently upregulated by nicotine exposure in neural progenitor cells derived from fetal mouse cortex189. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits α4 and β2 (Nchar-a2 and b2) were altered in the same direction as miR140-3 indicating a potential mechanism for long-term developmental effects of prenatal alcohol or nicotine on neurotransmission. Microarray analysis identified dramatic changes in miRNA patterns in whole brains of mice exposed to alcohol during gestation181; 190. Targets of these dysregulated miRNAs converged on several genes relevant to fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, including Pten, Nmnat1, Slitrk2, Otx2, and Hoxa1181. Co-incubation of alcohol-exposed mouse embryos with folate was able to block upregulation of miR-10a and -10b and downregulation of a target gene, Hoxa1190, indicating that these miRNAs are themselves regulated epigenetically by DNA methylation, and that dietary supplements may be able to mitigate some of the effects of fetal alcohol exposure.

Prenatal cocaine exposure in zebrafish altered mRNA levels of Drd1, Drd2a, Drd2b, and Drd3, Pitx3, and Th, genes known to be relevant for drug taking behavior191. These expression changes were accompanied by decreased miR-133b, in both encephalon and in the periphery191. It will be interesting to validate these findings in mammalian systems and test whether miR-133b may be a useful biomarker for changes occurring within the developing brain reward circuitry.

Postnatal Exposure

Altered miRNA expression was observed after chronic nicotine exposure in an atypical C. elegans model, from post-embryonic stage L1-L4 (juvenile)192. In both human placental tissue and C. elegans exposed to nicotine, miRNA variation was proportional to nicotine dose192; 193. However, it is unknown as of yet whether developmental nicotine exposure results in chronic alterations in miRNAs within mammalian brain.

LIMITATIONS, FUTURE DIRECTIONS, AND CONCLUDING REMARKS