Abstract

Background

A functional polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) in the promoter region of the serotonin transporter gene has been widely studied as a risk factor and moderator of treatment for a variety of psychopathologic conditions. To evaluate whether 5-HTTLPR moderates the effects of treatment to reduce heavy drinking, we studied 112 high-functioning European-American men who have sex with men (MSM). Subjects participated in a randomized clinical trial of naltrexone (NTX) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for problem drinking.

Methods

Subjects were treated for 12 weeks with 100 mg/day of oral NTX or placebo. All participants received medical management with adjusted Brief Behavioral Compliance Enhancement Treatment (BBCET) alone or in combination with Modified Behavioral Self-Control Therapy (MBSCT, an amalgam of motivational interviewing and CBT). Participants were genotyped for the tri-allelic 5-HTTLPR polymorphism (i.e., low-activity S′ or high-activity L′ alleles).

Results

During treatment, the number of weekly heavy drinking days (HDD, defined as 5 or more standard drinks per day) was significantly lower in subjects with the L′L′ (N=26, p=0.015) or L′S′ (N=52, p=0.016) genotype than those with the S′S′ (N=34) genotype regardless of treatment type. There was a significant interaction of genotype with treatment: For subjects with the S′S′ genotype, the effects of MBSCT or NTX on HDD were significantly greater than the minimal intervention (i.e., BBCET or placebo, p=0.007 and p=0.049, respectively). In contrast, for subjects with one or two L′ alleles, the effects of the more intensive psychosocial treatment (MBSCT) or NTX did not significantly differ from BBCET or placebo.

Conclusions

These preliminary findings support the utility of the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism for personalizing treatment selection in problem drinkers.

Keywords: pharmacogenetics, stress reactivity, psychotherapy, MSM, plasticity

Risk of psychiatric illness and response to its treatment are genetically influenced. Although a number of genetic moderators of pharmacotherapies for psychiatric disorders have been identified (e.g., review by Malhotra et al., 2012), much less is known about genetic moderators of the response to psychotherapy and combined pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy, particularly in the treatment of substance use disorders (Bauer et al., 2007).

One widely studied polymorphism that has been shown to moderate alcohol dependence risk and treatment response in some studies is a functional insertion/deletion polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) in the promoter region of the serotonin transporter gene SLC6A4 (Feinn et al., 2005, Olsson et al., 2005, Florez et al., 2008). 5-HTTLPR has been reported to modulate the transcriptional activity of SLC6A4 and levels of 5-HTT messenger RNA (mRNA) (Heils et al., 1996, Lesch et al., 1996, Hranilovic et al., 2004). Homozygotes for the low-expression short 5-HTTLPR (S) allele had greater anxiety symptoms in response to stress than long (L) allele carriers (Caspi et al., 2010), which may reflect greater reactivity to environmental stimuli and diminished ability to self-regulate anxiety, although mixed results have been reported regarding the relationship between 5-HTTLPR genotype and anxiety-related traits (e.g., Schinka et al., 2004). Studies generally have found greater alcohol use and dependence among individuals with the S allele, which may be related to individuals′ anxiety or depression (Feinn et al., 2005). It has also been reported that the S allele is associated with more frequent heavy episodic drinking and drinking to “get drunk” among college students (Herman et al., 2003). However, young adults with the LL genotype have also been reported to exhibit more hazardous drinking when exposed to high psychosocial adversity (Laucht et al., 2009). One possible explanation for the discrepant results is heterogeneity in the alcohol use disorder phenotype.

5-HTTLPR is functionally tri-allelic, in contrast to the bi-allelic categorization often reported (Hu et al., 2006, Zalsman et al., 2006). In addition to the insertion-deletion polymorphism, a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP; rs25531) was found to be tightly linked with the L-specific insertion. The SNP encodes an A→G exchange that renders the L allele functionally equivalent to the lower activity S allele in terms of promoter activity and RNA levels produced in cell culture systems (Hu et al., 2006, Perroud et al., 2010). Therefore, the L allele is differentiated into two variants: LA or LG. The lower expression LG variant is more appropriately grouped with the S than the LA variant. Using the tri-allelic approach, studies have been reported associations between 5-HTTLPR and the severity of depression (Zalsman et al., 2006) and the response to treatment with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor in patients with social anxiety (Stein et al., 2006)

In the present study, we examined the moderating effect of 5-HTTLPR on both pharmacotherapeutic and psychotherapeutic outcomes in high-functioning male heavy drinkers recruited for a randomized controlled trial in which the goal of treatment was to reduce drinking, rather than abstinence from alcohol. We hypothesized that the lowest expression (S′S′) genotype, which may reflect a greater reactivity to changes in environment, would be associated with a greater reduction in heavy drinking following the intervention with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or the opioid antagonist naltrexone.

Methods

Participants and procedures

Subjects were participants in Project SMART, a randomized controlled trial of combined medication and psychotherapy to reduce problem drinking in MSM (Morgenstern et al., 2012). Potential participants expressed a desire to reduce their drinking but not quit altogether. To be eligible for the study, men: 1) were 18 to 65 years old; 2) had an average consumption of at least 24 standard drinks per week over the last 90 days; 3) identified themselves as sexually active with other men; and 4) read English at an eighth grade level or higher. Participants were excluded if they: 1) had a lifetime diagnosis of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or other psychotic disorder; an untreated current major depressive disorder; or current dependence on drugs (with the exception of nicotine or cannabis); 2) started a new psychotropic medication in the last 90 days; 3) were at risk for serious medication side effects from naltrexone (NTX); or 4) were enrolled in concurrent drug or alcohol treatment during the treatment phase of Project SMART.

Procedures complied with and were approved by the New York State Psychiatric Institutional Review Board. Details of the procedures are provided in our recent reports (Morgenstern et al., 2012, Chen et al., 2013). Briefly, the sample consisted of 200 participants assigned via urn randomization to one of two medication conditions, NTX (100 mg/day orally) or placebo (PBO), and one of two counseling conditions, an adjusted version of Brief Behavioral Compliance Enhancement Treatment (BBCET, Johnson et al., 2003), or BBCET in combination with Modified Behavioral Self-control Therapy (MBSCT, an amalgam of motivational interviewing and CBT). The treatment phase lasted 12 weeks and the medication was administered double-blind. Only individuals of European ancestry who agreed to participate in the genetics study (N=122) are included in the present report to avoid any possible confounding results caused by population stratification.

Subject characteristics

Participants′ demographic features are detailed in Table 1. The typical participant was approximately 41 years of age, European-American, single, with prescreen (90 days) weekly sum of standard drinks (SSD) of 42.4 (standard deviation, SD=18.0), baseline (1 week immediately prior to the beginning of treatment) weekly SSD of 36.6 (SD=18.3), and approximately 7 drinks per drinking day. Seventy-five percent of participants completed college, and one-third of them attended graduate or professional school. Although a DSM-IV diagnosis of current alcohol dependence was not an inclusion criterion, the vast majority (91.8%) of subjects included in this study met criteria for the diagnosis, which is similar to our recent report that included all 200 subjects of any ethnicity (Morgenstern et al., 2012). There were no differences in the prescreen characteristics among the three genotype groups except other drug use (Table 1).

Table 1. Prescreen Characteristics of Subjects.

| Condition |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L′L′ (n = 26) |

L′S′ (n = 58) |

S′S′ (n = 38) |

||||

| Variable | M or % | SD | M or % | SD | M or % | SD |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age | 39.5 | 10.3 | 40.1 | 11.1 | 42.1 | 12.9 |

| Education | ||||||

| High school/GED or less | 4 | 4 | 6 | |||

| Some college/associate’s | 20 | 18 | 25 | |||

| Bachelor’s degree | 44 | 43 | 36 | |||

| Some grad/grad/professional | 32 | 35 | 33 | |||

| Employment | ||||||

| Employed | 72 | 84 | 78 | |||

| Unemployed/looking for work | 20 | 6 | 8 | |||

| Not in labor force/not looking | 8 | 10 | 14 | |||

| Drinking severity | ||||||

| Mean sum standard drinks/week | 42.5 | 19.9 | 42.5 | 17.2 | 42.1 | 18.4 |

| Mean drinks per drinking day | 7.6 | 3.0 | 7.7 | 2.7 | 7.6 | 2.6 |

| Mean number heavy drinking days/week | 3.3 | 2.2 | 3.7 | 2.0 | 3.3 | 1.9 |

| Short Inventory of Problems score | 16.6 | 7.5 | 15.2 | 7.4 | 14.9 | 6.9 |

| Alcohol Dependence Scale score | 14.0 | 5.2 | 13.8 | 5.9 | 12.3 | 4.4 |

| Number of alcohol dependence criteria met | 5.0 | 1.6 | 5.0 | 1.4 | 4.3 | 1.8 |

| Any drug usea | 46 | 76 | 63 | |||

| Prior treatment for alcohol use problems | 21 | 8 | 13 | |||

| BDI-II score | 19.4 | 7.8 | 18.7 | 8.8 | 16.1 | 6.8 |

| State STAI score | 39.2 | 9.6 | 38.9 | 12.2 | 40.1 | 11.5 |

Note. M: mean. SD: standard deviation. BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory. STAI: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory.

χ2 (2, N = 122) = 7.16, p = 0.03.

Substance use and other psychiatric disorders

The Composite International Diagnostic Instrument, Substance Abuse Module (CIDI-SAM, Cottler et al., 1989) was used to evaluate substance dependence criteria. Participants were screened for psychosis and other thought disorders using the psychotic screening and bipolar disorder sections of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, (SCID, First et al., 1996) and for cognitive impairment using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE, Folstein et al., 1975). Depressive symptoms were measured using the revised Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II, Beck et al., 1996). The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI, Spielberger, 1983) was used to measure anxiety symptoms. All participants also a received psychiatric diagnostic interview by a psychiatrist for a final determination of eligibility.

Alcohol and drug use patterns and problems

The Time-Line Follow-Back Interview (TLFB, Sobell et al., 1980) was used to assess the frequency of alcohol and drug use during the previous 90 days at prescreen and at the end of treatment. Drinking and drug use were also assessed with the TLFB for the period between the prescreen and baseline interviews (typically 1-2 weeks). To assess the quantity and intensity of alcohol use, three variables were created from the TLFB data. Two primary outcomes--weekly sum of standard drinks (SSD), and weekly number of heavy drinking days (HDD)--were selected a priori because NIAAA safe drinking guidelines (http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/CliniciansGuide2005/clinicians_guide.htm) include measures of drinking quantity (no more than 14 drinks per week for men) and intensity (no heavy drinking days, i.e., no more than 4 drinks per day for men).

Genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood using standard methods. The 5-HTTLPR polymorphism was genotyped using a TaqMan 5′ nuclease assay modified from that originally described by Hu and colleagues (Hu et al., 2006). A more detailed description of our genotyping procedure can be found in Covault et al., (2007). The number of L alleles (0, 1, or 2) for each subject was identified by examination of scatterplots of end-point Fam versus Vic fluorescence levels captured using an ABI 7500 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California). A second TaqMan (Applied Biosystems) 5′ nuclease allelic discrimination assay served to distinguish LA versus LG alleles by using the same primers and amplification conditions as for the L versus S allele assay but using LA versus LG allele-specific probes (6FAM-CCCCCCTGCACCCCCAGCATCCC-MGB and VIC-CCCCTGCACCCCCGGCATCCCC-MGB, respectively). We repeated the genotyping for 17% of samples with no discrepancy between assays. We did not observe the G allele in samples from S-allele homozygotes, consistent with the findings of Hu and colleagues (2006).

Data Analysis

Generalized estimating equation analysis (GEE), an analytic method for longitudinal data that corrects for correlated observations, was used to analyze the number of weekly heavy drinking days (HDD, defined as 5 or more standard drinks per day) across the 12-week treatment period. Within the GEE analysis, a negative binomial distribution with log function was specified, along with a working exchangeable correlation matrix, and provided good model fit to the data. Of the 122 subjects of European ancestry who agreed to participate in the genetic sub-study, 112 provided adequate drinking data for the treatment period and are included in these analyses. The independent variables (IVs) for the models were genotype (L′L′, L′S′, or S′S′), medication (NTX or PBO) and psychotherapy (MBSCT/BBCET) treatment conditions and the interaction of these conditions. To allow for simultaneous testing of both main and interaction effects, the IVs of medication and psychotherapy treatment conditions were orthogonally coded. Time and the interactions of time with genotype, medication condition, and psychotherapy condition were also included in the models to test for differential effects over the 12-week treatment period. In addition, the time variable was centered. The 90-day pre-screen average weekly HDD and the baseline (BL-1, i.e., one week prior to treatment) HDD were included to control for pretreatment drinking. Nevertheless, the interaction between medication and psychotherapy condition was not hypothesized as it was not found in prior analyses (Morgenstern et al., 2012).

Results

Genotype distribution

The distribution of participant genotypes is shown in Table 2. The S and LG alleles were grouped together and labeled S′, and the LA allele was labeled L′. Using this categorization, the distribution of genotypes did not deviate from the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (χ2 (df=2, N = 112) = 0.577, p=0.749). In addition, there were no significant differences in genotype frequencies among the four treatment groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Genotype frequency of 5HTTLPR grouped by treatment

| 5HTTLPR Genotype |

Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S′S′ | L′S′ | L′L′ | |||

| Total | 34 | 52 | 26 | 112 | |

| Psychotherapy condition1 |

|||||

| BBCET | 15 | 30 | 14 | 63 | |

| BBCET + MBSCT | 19 | 22 | 12 | 49 | |

| Medication condition2 | |||||

| Placebo | 22 | 23 | 13 | 58 | |

| Naltrexone | 12 | 29 | 13 | 54 | |

Pearson Chi-Square = 0.107, p=0.948

Pearson Chi-Square = 3.495, p=0.174

5-HTTLPR moderates naltrexone and psychosocial treatment responses

No significant differences in drinking outcomes were detected when testing GEE models using the 3-level (S′S′/L′S′/L′L′) independent variable. Upon examination of the trajectories of HDD for each of the genotypes, it was noted that the trajectory for S′ homozygotes was different from that of both the L′S′ and L′L′ genotypes, which were very similar to each other (Supplementary Figure 1). Thus, a GEE model was run comparing only the L′S′ genotype with the L′L′ genotype and revealed no significant differences in drinking outcomes. Therefore, it was decided to compare both L′ homozygotes and heterozygotes separately with S′ homozygotes.

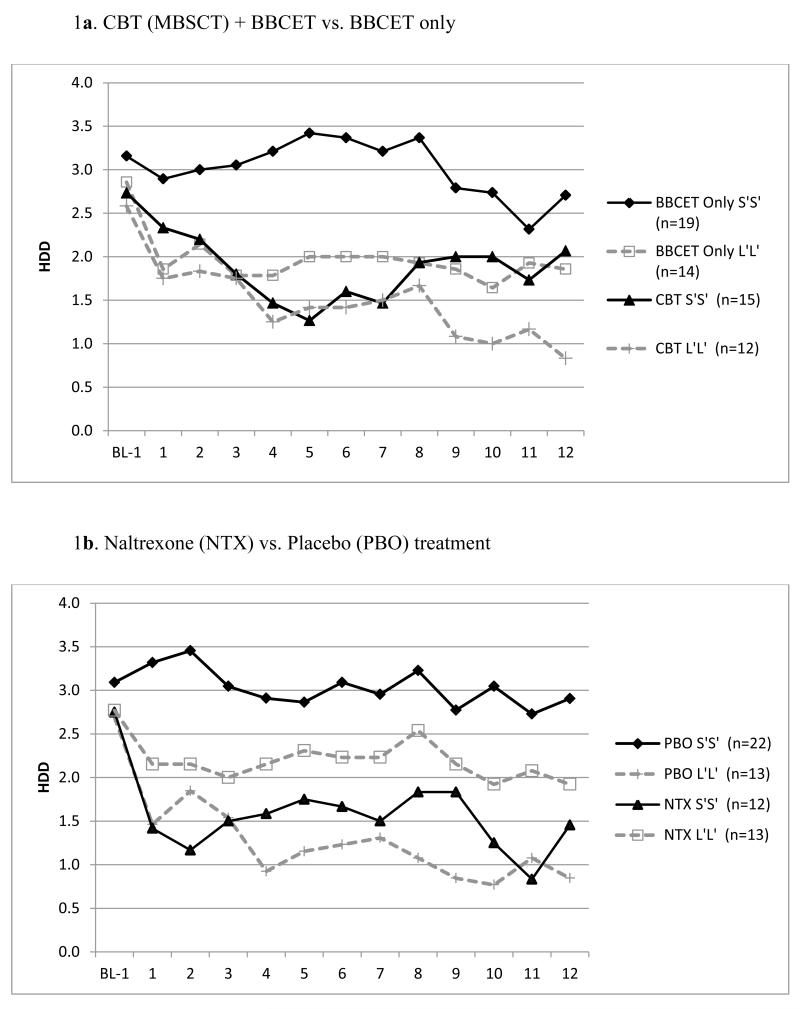

We found a significant main effect when comparing the S′ (N=34) and L′ (N=26) homozygotes, such that the average number of weekly HDDs during the 12 weeks of treatment was lower for L′ homozygotes (B = −0.46, SE = 0.17, 95% CI = −0.84, −0.15, p=0.015) than for S′ homozygotes, regardless of treatment type (Supplementary Figure 1). There also were significant genotype by psychotherapy treatment (i.e., MBSCT+BBCET/BBCET-alone) and genotype by medication (NTX/PBO) interactions (B = 0.80, SE = 0.36, 95% CI = 0.09, 1.51, p = 0.027, and B = 0.89, SE = 0.36, 95% CI = 0.19, 1.60, p = 0.013, respectively). For S′ homozygotes, the independent effects of MBSCT (B = −0.57, SE = 0.21, 95% CI = −0.99, −0.15, p=0.007) and NTX (B =−0.44, SE=0.22, 95% CI=−0.87, −0.00, p=0.049) were significantly greater than the respective control interventions (i.e., BBCET or PBO, Figure 1). In contrast, for subjects with the L′L′ genotype, the effects of the more intensive psychosocial treatment (MBSCT) did not differ significantly (B=0.23, SE=0.29, 95% CI = −0.34, 0.80, p=0.437, Figure 1a) from those in the BBCET group. Paradoxically, L′ homozygotes treated with NTX had more HDDs, although not significantly (B=0.46, SE=0.29, 95% CI = −0.12, 1.03, p = 0.120), than those receiving PBO (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Responses to psychotherapy (MBSCT) and medication (naltrexone) in adult males whose goal was to moderate but not quit drinking by 5-HTTLPR genotype (S′S′ vs. L′L′). Panel a shows the number of average weekly heavy drink days (HDD, defined as 5 or more standard drinks per day), along the treatment course (week) grouped by psychotherapy condition and genotype, while panel b shows the results grouped by medication condition and genotype. BL1: baseline beginning of treatment.

We also found a significant main effect for genotype when we compare S′ homozygotes with heterozygotes (N=52, Figure 2). Heterozygotes had, on average, fewer weekly HDD over the 12-week treatment period (B = −0.40, SE = 0.16, 95% CI = −0.72, −0.07, p = 0.016) than S′ homozygotes. However, in contrast to the L′ homozygote and S′ homozygote comparisons, when comparing S′ homozygotes with heterozygotes, there were no significant genotype by psychotherapy treatment (B = −0.04, SE = 0.32, 95% CI = −0.67, 0.59, p = 0.902) or medication (B = −0.49, SE = 0.30, 95% CI = −0.09, 1.07, p = 0.099) condition interactions. There was a significant main effect for psychotherapy treatment such that the more intensive psychotherapy (MBSCT) was associated significantly (B = −0.39, SE = 0.16, 95% CI = −0.70, −0.08, p = 0.014) with fewer HDD over the treatment period than BBCET-only (Figure 2a). However, there was not a significant main effect for NTX versus PBO (B=−0.15, SE=0.16, 95% CI =−0.47, 0.18, p=0.376, Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Responses to psychotherapy (MBSCT) and medication (naltrexone) in adult males whose goal was to moderate but not quit drinking, by 5-HTTLPR genotype (S′S′ vs. L′S′). Panel a shows the number of average weekly heavy drink days (HDD, defined as 5 or more standard drinks per day), along the treatment course (week) grouped by psychotherapy condition and genotype, while panel b shows the results grouped by medication condition and genotype. BL1: baseline beginning of treatment.

Because the drinking trajectories for the L′L′ and L′S′ genotypes were very similar to each other, we did additional exploratory analyses to compare S′ homozygotes (N=34) with a clustered group composed of L′ homozygotes and heterozygotes (N=78). The results were similar, showing that there was a significant main effect for psychotherapy treatment such that the more intensive psychotherapy (MBSCT) was associated significantly with fewer HDD over the treatment period than BBCET-only (Detailed data are not shown).

Discussion

This is the first alcohol treatment trial that has simultaneously evaluated genetic moderator effects for both medication and psychotherapy. The results showed a significant interaction of genotype and treatment type: For subjects with the S′S′ genotype, but not others, the effects of NTX or MBSCT were significantly greater than the control intervention (i.e., PBO or BBCET). In addition, the number of weekly heavy drinking days was significantly lower in subjects with the L′L′ or L′S′ genotype than those with the S′S′ genotype, regardless of treatment type.

The biological mechanism by which the serotonin transporter (5-HTT) affects alcohol consumption is still unclear (Johnson, 2004, Johnson et al., 2011). It has been reported that serotonergic function can influence drinking behavior in alcohol-dependent individuals either directly by modulating the reinforcing effects of alcohol or indirectly by mediating impulse control and affective state (Stoltenberg, 2003). Animal studies have shown an inhibitory role for serotonin (5-HT) in regulating alcohol intake (McBride and Li, 1998). Specific serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have been reported to reduce alcohol consumption in rats (Gill et al., 1989). However, the effectiveness of SSRIs at reducing drinking in humans is not clear. Studies have shown that earlier-onset, higher vulnerability patients with alcohol use disorder had poorer drinking outcomes when treated with either fluoxetine (Kranzler et al., 1996) or fluvoxamine (Chick et al., 2004) than with placebo and later-onset, lower vulnerability patients showed better drinking outcomes with sertraline treatment than with placebo (Pettinati et al., 2000).

Kranzler et al., (2011) reported that the effects of sertraline were conditional on 5-HTTLPR genotype. Further studies (Kranzler et al., 2012) demonstrated a daily anxiety × age of onset × 5-HTTLPR polymorphism × medication interaction, which reflected a daily anxiety × medication group effect for early-onset individuals homozygous for the high-expression (L′) allele, but not others. Specifically, on days characterized by relatively high levels of anxiety, early-onset L′ homozygotes receiving placebo reduced their drinking intensity significantly. In contrast, early-onset L′ homozygotes treated with sertraline non-significantly increased their drinking intensity. These findings implicate anxiety as a key moderator of the observed pharmacogenetic effects, and indirectly support our hypothesis that individual stress reactivity, which in part manifests itself as anxiety, may influence the treatment outcomes for alcohol use disorder. The finding that L′ homozygotes treated with NTX had more HDDs, although not significantly, than those receiving PBO, was similar to that reported for sertraline (Kranzler et al., 2012). We were unable to analyze the age of onset or levels of daily anxiety in the small number of L′ homozygotes due to the limitation of available data collected in the subjects. We speculate that they may share similar characteristics and mechanisms.

A recent cross-sectional study on the response to CBT in 584 children with anxiety disorder showed significant associations between 5-HTTLPR and anxiety responses at follow up, which was usually 6 months after treatment (Eley et al., 2012). Children with the SS genotype, but not others, showed a significantly greater reduction in symptom severity from pre-treatment to follow up. The findings are similar to our results, in which only individuals with the S′S′ genotype showed significant changes in the number of HDDs following CBT when compared with those receiving the comparison psychosocial intervention, i.e., BBCET. Findings in both studies suggest that the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism influences responses to psychosocial interventions, which supports the hypothesis that this marker contributes to individuals′ sensitivity to the environment (Belsky and Pluess, 2009).

A growing body of work suggests that S allele carriers, while more sensitive to stress, may also be more responsive to supportive environments or treatment interventions to reduce the impact of environmental stressors (Kaufman et al., 2004, Hankin et al., 2011). It has been hypothesized that the S allele is a “plasticity factor” rather than simply a risk factor following exposure to adverse environment (e.g., Kuepper et al., 2012). Our data support the idea that the S-allele of 5-HTTLPR is associated with an overall increased reactivity to environmental influences, as individuals with S′S genotypes were more heavily influenced by treatment conditions, either psychosocial or pharmacological. These findings extend earlier data supporting the plasticity hypothesis of 5-HTTLPR. The findings also support the potential utility of studies of other genetic moderators of the response to psychotherapy, which in a manner similar to pharmacogenetics, could aid in treatment selection.

The current study is novel in that it compared the moderating effect of a widely studied genetic polymorphism on both pharmacological and psychosocial treatment responses in the same cohort, an approach that provides insight into the mechanism underlying the interactive effects. The all-male study sample limits its generalizability, but eliminated potential confounding effects of gender (Philibert et al., 2008, Cerasa et al., 2013). Furthermore, the subjects were high functioning individuals whose treatment goal was to reduce drinking rather than quit altogether. This may represent a unique and relatively homogeneous subgroup of heavy drinkers that differs from those included in most other studies. Nevertheless, our findings must be viewed in the context of modest sample size, particularly the L′ homozygote subsample, yielding modest statistical power. To replicate these findings, subsequent studies may need to select participants based on their genotype to ensure adequate numbers in all treatment cells.

In conclusion, our results suggest that a matching strategy in which problem drinkers who are S′-allele homozygotes are best treated with NTX and/or a CBT-related treatment while L′-allele carriers can receive a less intensive treatment. If these findings are replicated in a larger sample and extended to women, they could help to personalize treatment selection in problem drinkers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Supported by the grants from the National Institutes of Health: R01 AA015553 (J.M.), K24 AA013736 (H.R.K), K23 AA018696 (A.C.H.C.) and M01 RR06192 (University of Connecticut Health Center GCRC).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure: Dr. Kranzler has been a consultant or advisory board member for Alkermes, Lilly, Lundbeck, Pfizer, and Roche and a member of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology’s Alcohol Clinical Trials Initiative (ACTIVE), which has received support from AbbVie, Lilly, Lundbeck, and Pfizer.

References

- Bauer LO, Covault J, Harel O, Das S, Gelernter J, Anton R, Kranzler HR. Variation in GABRA2 predicts drinking behavior in project MATCH subjects. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2007;31:1780–1787. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00517.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition Manual, in Series Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition Manual. Harcourt Brace; San Diego, CA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Pluess M. Beyond diathesis stress: differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychological bulletin. 2009;135:885–908. doi: 10.1037/a0017376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Hariri AR, Holmes A, Uher R, Moffitt TE. Genetic sensitivity to the environment: the case of the serotonin transporter gene and its implications for studying complex diseases and traits. The American journal of psychiatry. 2010;167:509–527. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerasa A, Quattrone A, Piras F, Mangone G, Magariello A, Fagioli S, Girardi P, Muglia M, Caltagirone C, Spalletta G. 5-HTTLPR, anxiety and gender interaction moderates right amygdala volume in healthy subjects. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience. 2013 doi: 10.1093/scan/nst144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen AC, Morgenstern J, Davis CM, Kuerbis AN, Covault J, Kranzler HR. Variations in mu-opioid receptor gene (OPRM1) as a moderator of naltrexone treatment to reduce heavy drinking in a high functioning cohort. Journal of Alcoholism and Drug Dependence. 2013;1:101–104. doi: 10.4172/2329-6488.1000101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chick J, Aschauer H, Hornik K, Investigators G. Efficacy of fluvoxamine in preventing relapse in alcohol dependence: a one-year, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicentre study with analysis by typology. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottler LB, Robins LN, Helzer JE. The reliability of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Substance Abuse Module-(CIDI-SAM): A comprehensive substance abuse interview. British Journal of Addiction. 1989;84:801–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covault J, Tennen H, Armeli S, Conner TS, Herman AI, Cillessen AH, Kranzler HR. Interactive effects of the serotonin transporter 5-HTTLPR polymorphism and stressful life events on college student drinking and drug use. Biological psychiatry. 2007;61:609–616. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eley TC, Hudson JL, Creswell C, Tropeano M, Lester KJ, Cooper P, Farmer A, Lewis CM, Lyneham HJ, Rapee RM, Uher R, Zavos HM, Collier DA. Therapygenetics: the 5HTTLPR and response to psychological therapy. Molecular psychiatry. 2012;17:236–237. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinn R, Nellissery M, Kranzler HR. Meta-analysis of the association of a functional serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism with alcohol dependence. American journal of medical genetics. Part B, Neuropsychiatric genetics: the official publication of the International Society of Psychiatric Genetics. 2005;133B:79–84. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, in Series Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. Biometric Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Florez G, Saiz P, Garcia-Portilla P, Alvarez S, Nogueiras L, Morales B, Alvarez V, Coto E, Bobes J. Association between the Stin2 VNTR polymorphism of the serotonin transporter gene and treatment outcome in alcohol-dependent patients. Alcohol and alcoholism. 2008;43:516–522. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill K, Mundl WJ, Cabilio S, Amit Z. A microcomputer controlled data acquisition system for research on feeding and drinking behavior in rats. Physiology & behavior. 1989;45:741–746. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(89)90288-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Nederhof E, Oppenheimer CW, Jenness J, Young JF, Abela JR, Smolen A, Ormel J, Oldehinkel AJ. Differential susceptibility in youth: evidence that 5-HTTLPR x positive parenting is associated with positive affect ‘for better and worse’. Translational psychiatry. 2011;1:e44. doi: 10.1038/tp.2011.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heils A, Teufel A, Petri S, Stober G, Riederer P, Bengel D, Lesch KP. Allelic variation of human serotonin transporter gene expression. Journal of neurochemistry. 1996;66:2621–2624. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66062621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman AI, Philbeck JW, Vasilopoulos NL, Depetrillo PB. Serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism and differences in alcohol consumption behaviour in a college student population. Alcohol and alcoholism. 2003;38:446–449. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agg110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hranilovic D, Stefulj J, Schwab S, Borrmann-Hassenbach M, Albus M, Jernej B, Wildenauer D. Serotonin transporter promoter and intron 2 polymorphisms: relationship between allelic variants and gene expression. Biological psychiatry. 2004;55:1090–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu XZ, Lipsky RH, Zhu G, Akhtar LA, Taubman J, Greenberg BD, Xu K, Arnold PD, Richter MA, Kennedy JL, Murphy DL, Goldman D. Serotonin transporter promoter gain-of-function genotypes are linked to obsessive-compulsive disorder. American journal of human genetics. 2006;78:815–826. doi: 10.1086/503850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BA. Role of the serotonergic system in the neurobiology of alcoholism: implications for treatment. CNS drugs. 2004;18:1105–1118. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200418150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BA, Ait-Daoud N, Seneviratne C, Roache JD, Javors MA, Wang XQ, Liu L, Penberthy JK, DiClemente CC, Li MD. Pharmacogenetic approach at the serotonin transporter gene as a method of reducing the severity of alcohol drinking. The American journal of psychiatry. 2011;168:265–275. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10050755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BA, DiClemente CC, Ait-Daoud N, Stoks SM. Brief Behavioral Compliance Enhancement Treatment (BBCET) manual. In: JOHNSON BA, RUIZ P, GALANTER M, editors. Handbook of Clinical Alcoholism Treatment, Handbook of Clinical Alcoholism Treatment. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore, MD: 2003. pp. 282–301. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Yang BZ, Douglas-Palumberi H, Houshyar S, Lipschitz D, Krystal JH, Gelernter J. Social supports and serotonin transporter gene moderate depression in maltreated children. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:17316–17321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404376101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranzler HR, Armeli S, Tennen H, Covault J. 5-HTTLPR genotype and daily negative mood moderate the effects of sertraline on drinking intensity. Addiction biology. 2012 doi: 10.1111/adb.12007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranzler HR, Armeli S, Tennen H, Covault J, Feinn R, Arias AJ, Pettinati H, Oncken C. A double-blind, randomized trial of sertraline for alcohol dependence: moderation by age of onset [corrected] and 5-hydroxytryptamine transporter-linked promoter region genotype. Journal of clinical psychopharmacology. 2011;31:22–30. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31820465fa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranzler HR, Burleson JA, Brown J, Babor TF. Fluoxetine treatment seems to reduce the beneficial effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy in type B alcoholics. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 1996;20:1534–1541. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuepper Y, Wielpuetz C, Alexander N, Mueller E, Grant P, Hennig J. 5-HTTLPR S-allele: a genetic plasticity factor regarding the effects of life events on personality? Genes, brain, and behavior. 2012;11:643–650. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2012.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laucht M, Treutlein J, Schmid B, Blomeyer D, Becker K, Buchmann AF, Schmidt MH, Esser G, Jennen-Steinmetz C, Rietschel M, Zimmermann US, Banaschewski T. Impact of psychosocial adversity on alcohol intake in young adults: moderation by the LL genotype of the serotonin transporter polymorphism. Biological psychiatry. 2009;66:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesch KP, Bengel D, Heils A, Sabol SZ, Greenberg BD, Petri S, Benjamin J, Muller CR, Hamer DH, Murphy DL. Association of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Science. 1996;274:1527–1531. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5292.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra AK, Zhang JP, Lencz T. Pharmacogenetics in psychiatry: translating research into clinical practice. Molecular psychiatry. 2012;17:760–769. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Kuerbis AN, Chen AC, Kahler CW, Bux DA, Kranzler HR. A Randomized Clinical Trial of Naltrexone and Behavioral Therapy for Problem Drinking Men Who Have Sex With Men. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0028615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson CA, Byrnes GB, Lotfi-Miri M, Collins V, Williamson R, Patton C, Anney RJ. Association between 5-HTTLPR genotypes and persisting patterns of anxiety and alcohol use: results from a 10-year longitudinal study of adolescent mental health. Molecular psychiatry. 2005;10:868–876. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perroud N, Salzmann A, Saiz PA, Baca-Garcia E, Sarchiapone M, Garcia-Portilla MP, Carli V, Vaquero-Lorenzo C, Jaussent I, Mouthon D, Vessaz M, Huguelet P, Courtet P, Malafosse A, European Research Consortium for S Rare genotype combination of the serotonin transporter gene associated with treatment response in severe personality disorder. American journal of medical genetics. Part B, Neuropsychiatric genetics: the official publication of the International Society of Psychiatric Genetics. 2010;153B:1494–1497. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettinati HM, Volpicelli JR, Kranzler HR, Luck G, Rukstalis MR, Cnaan A. Sertraline treatment for alcohol dependence: interactive effects of medication and alcoholic subtype. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2000;24:1041–1049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philibert RA, Sandhu H, Hollenbeck N, Gunter T, Adams W, Madan A. The relationship of 5HTT (SLC6A4) methylation and genotype on mRNA expression and liability to major depression and alcohol dependence in subjects from the Iowa Adoption Studies. American journal of medical genetics. Part B, Neuropsychiatric genetics: the official publication of the International Society of Psychiatric Genetics. 2008;147B:543–549. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinka JA, Busch RM, Robichaux-Keene N. A meta-analysis of the association between the serotonin transporter gene polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) and trait anxiety. Molecular psychiatry. 2004;9:197–202. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell MB, Maisto SA, Sobell LC, Cooper AM, Cooper T, Saunders B. Developing a prototype for evaluating alcohol treatment effectiveness. In: SOBELL LC, WARD E, editors. Evaluating alcohol and drug abuse treatment effectiveness: Recent advances, Evaluating alcohol and drug abuse treatment effectiveness: Recent advances. Pergamon; New York: 1980. pp. 129–150. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorssuch RL, Lushene PR, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc.; Palo Alto, CA: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Seedat S, Gelernter J. Serotonin transporter gene promoter polymorphism predicts SSRI response in generalized social anxiety disorder. Psychopharmacology. 2006;187:68–72. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0349-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenberg SF. Serotonergic agents and alcoholism treatment: a simulation. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2003;27:1853–1859. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000098876.94384.0A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalsman G, Huang YY, Oquendo MA, Burke AK, Hu XZ, Brent DA, Ellis SP, Goldman D, Mann JJ. Association of a triallelic serotonin transporter gene promoter region (5-HTTLPR) polymorphism with stressful life events and severity of depression. The American journal of psychiatry. 2006;163:1588–1593. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.