Abstract

Background

Communication skills are critical in Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine because these patients confront complex clinical scenarios. We evaluated effectiveness of the Geritalk communication skills course by comparing pre- and post-course real-time assessment of participants leading family meetings. We also evaluated the participants’ sustained skills practice.

Measures

We compare participants’ skill acquisition before and after Geritalk using a direct observation Family Meeting Communication Assessment Tool, and assessed their deliberate practice at follow-up.

Intervention

First-year Geriatrics or Palliative Medicine fellows at Mount Sinai Medical Center and the James J. Peters Bronx VA Medical Center participated in Geritalk.

Outcomes

Pre- and post-course family meeting assessments were compared. An average net gain of 6.8 skills represented a greater than 20% improvement in use of applicable skills. At two-month follow-up, most participants reported deliberate practice of fundamental and advanced skills.

Conclusions

This intensive training and family meeting assessment offers evidence-based communication skills training.

BACKGROUND

Emerging evidence suggests that discussions with patients and families about the patient’s prognosis and plan of care, led by skilled communicators, decreased family burden,1 improved family satisfaction and bereavement outcomes, and resulted in lower costs of care.1–3 Communication skills are particularly important in the fields of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine because these patients face especially complex clinical scenarios.

It is critical that communication skills are taught effectively. Indeed, the American College of Graduate Medical Education’s Next Accreditation System, an outcomes-based evaluation system to measure competency in performing the essential clinical tasks, highlights communication skills as central to milestones for a variety of fields.4 Multiple studies have demonstrated that teaching communication skills by lecture alone will not result in improvement.5,6 Programs based upon the learning models of experiential learning and deliberate practice have succeeded in teaching communications skills and changing physician behavior.6

The Geritalk course7 is an innovative program, built on the foundation of experiential learning and deliberate practice, designed for Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine fellows, to improve their communication skills. Modeled on the successful Oncotalk program,6 Geritalk is an educational intervention which focuses on teaching, practicing and reflecting on effective communication skills. A previous study7 about Geritalk demonstrated that overall satisfaction with the program was very high and the program increased the self-assessed preparedness for specific communication challenges, and sustained skills practice. In this article, we report 1) the impact of the Geritalk program on communication skill acquisition by directly observing participants leading family meetings before and after the course and 2) the sustained deliberate practice of the participants 2 months after the course.

INTERVENTION

Midyear, the fellows participated in the 2-day Geritalk program7, which includes a curriculum of didactic presentations and demonstrations, small-group communication skills practice, and future skills practice commitment. The didactic sessions addressed basic communication skills, giving bad news, negotiating goals of care, and forgoing life-sustaining treatment, including do-not-resuscitate orders.7 Following each didactic, participants were split into two small groups, each with 2 faculty facilitators, for a practice session focused on the communication skills reviewed in the lecture and demonstration. Through interactions with simulated patients or family-members, the fellows worked to develop their communication skills in an individualized step-wise fashion. In each practice session, the faculty emphasized deliberate practice.

MEASURES

All first-year fellows in Geriatrics or Palliative Medicine at the Mount Sinai Medical Center and its affiliate, the James J. Peters Bronx VA Medical Center were eligible to participate. After providing written informed consent, participants completed a baseline survey, which included demographics, prior experience in leading family meetings, and self-assessment of their competence and confidence in delivering bad news and conducting goals of care discussions.8,9

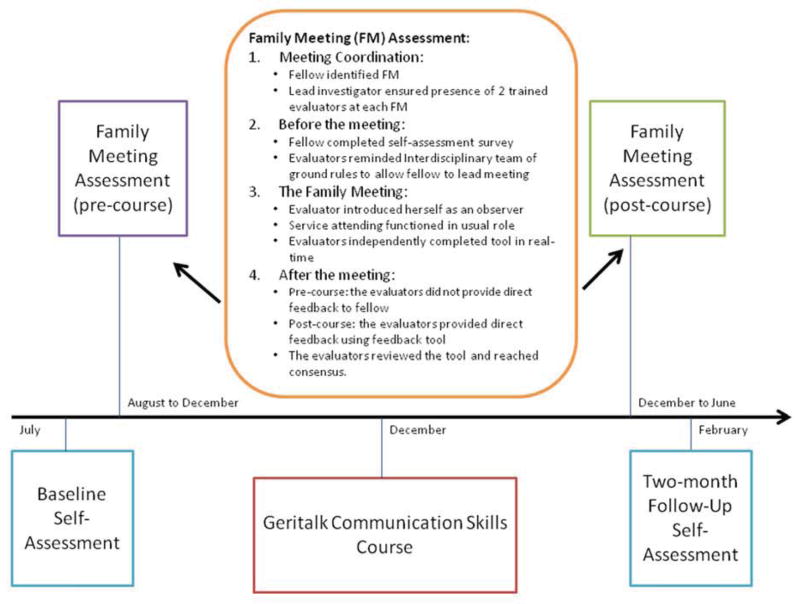

Figure 1 provides a timeline of the study, including the baseline survey, pre-course family meeting assessment, Geritalk course, post-course family meeting assessment, and post-course self-assessment. Participants’ data were de-identified and linked by unique study identification codes. The Institutional Review Board for the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai approved this study.

Figure 1.

Study Protocol and Timeline

Measurements: Pre-Course and Post-Course Direct Observation Family Meeting Assessments

The family meeting, defined as any conversation with a patient and/or family about the patient’s disease, treatment plan, goals of care, or transitions in care, is a key opportunity to observe and assess communication skills. In order to evaluate the impact of the Geritalk course in learner acquisition of communication skills, we developed the FaMCAT, a real-time Family Meeting Communication Assessment Tool. The FaMCAT (Appendix B) is a checklist of 31 distinct communication skills, identified by communication skills experts to be the most important when communicating with patients and families.5 The FaMCAT was shown to be feasible, reliable (inter-rater reliability 0.68), and useful in identification of areas for further training. All faculty evaluators completed training in the use of the FaMCAT. Please see Appendix A (available at jpsmjournal.coom) for details on the evaluation of the tool and evaluator training.

The family meeting evaluations occurred both before Geritalk (between August and the start of Geritalk in December) and after Geritalk (between the end of Geritalk in December and June) during actual clinical encounters. In all cases, one or both evaluators of the post-course assessment were different from the evaluators of the pre-course assessment. Post-course evaluators were blinded to the participant’s pre-course performance.

Before the meeting, the participant provided basic demographic information about the patient, the goal or purpose of the meeting and the meeting attendees. In addition, the evaluators reminded the interdisciplinary clinical team of the study’s protocol to evaluate the participant leading the meeting. During the family meeting, each evaluator completed the evaluation tool independently. Afterward, the two evaluators compared assessments and resolved discrepancies to reach consensus. The two independent evaluation and the consensus evaluation forms were submitted to the research coordinator. The consensus evaluation form was used for data analysis.

OUTCOMES

Primary Outcome: Participant Skill Acquisition

The participant skill acquisition was measured comparing each participant’s use of each skill before and after the course. Each skill was evaluated as “Yes” for a skill used, “No” for a skill not used or “NA” for not applicable during the meeting observed.

We also assessed a subset of 8 fundamental skills, i.e., those identified by communication skills experts5 as the minimal skills required to competently conduct a family meeting. These skills included the following: 1) greeting (made appropriate introductions and explained role), 2) assessed patient’s/family’s understanding, 3) gave information in a balanced manner and clarified misconceptions, 4) avoided the use of medical jargon, 5) checked for understanding, 6) used empathic continuers5 or statements that directly addressed the patients’ emotions, validated their feelings and invited further disclosure, 7) used open-ended questions (i.e. “tell me about your loved one”), and 8) provided a summary at the end of the meeting and assessed patient or family member’s understanding.

Secondary Outcome: Deliberate Practice

Post-course Family Meeting Assessment Feedback

The secondary aim was to evaluate learner’s use of deliberate practice following the course. In addition to the observation-based assessment, the post-course evaluation included the opportunity for feedback using the deliberate practice framework taught during the course. Prior to the family meeting assessment, each participant identified a communication skill on which they wanted to work, i.e., practice deliberately. While completing the post-course family meeting assessment, the faculty observers took additional notes specifically related to this skill. Following the family meeting, one or both of the trained faculty evaluators provided learner-centered feedback. Specifically, the faculty observer asked the participant to reflect on what went well during the meeting, what could be done differently next time when facing a similar challenge, and which specific communication skills might be useful to try in the future.

Two-Month Follow-Up Self-Assessment

The investigators created a 45 item two-month follow-up self-assessment. The two-month interval was chosen to ensure the participants would have ample time to practice their new skills and to reflect on the training itself. In order to assess the sustained effect of using deliberate practice to improve communication skills, the participants were asked “How often have you practiced the following communication skills over the last two months?”. This question applied to the 31 skills in the FaMCAT on a 5-point Likert scale of “never” to “always”.

In addition, the participants were asked “How valuable was the Geritalk training to improve communication skills?” and “How often have you thought about what you were taught in the Geritalk communication course?”. Finally, they were asked about their overall evaluation of the course.

RESULTS

Participant Demographics and Baseline Self-Assessment of Communication Skills

Nine (100%) fellows completed the study. Eight were female (89%); the median age was 32 years. Five (56%) were Palliative Medicine fellows and 4 (44%) were Geriatrics fellows. Overall, 7 (78%) completed a residency in Internal Medicine. Six (67%) reported prior training in communication. Six (67%) participants reported that they had led 1–5 family meetings and 3 (33%) reported they led more than 5 family meetings. At baseline, few participants felt competent to independently give bad news to a patient or family member (33%) or discuss goals of care with a patient or family member (22%).

Family Meeting Assessments

The pre-course family meeting assessments took place an average of 68 days (range, 8 to 143 days) before to the course. The post-course family meeting assessments took place an average of 88 days (range, 34 to 176 days) after the course. The mean duration of the family meetings was 42 minutes (range, 25 to 75 minutes). The average patient age was 73 years (range 32 to 96) and 70% were male. The patients had a wide variety of diagnoses: metastatic cancer, respiratory failure in the setting of sepsis, stroke/subarachnoid hemorrhage, dementia, and heart failure; and the majority (80%) had an estimated the life expectancy of less than one year. The patient participated in 44% of the meetings and family participated in 94% of the meetings. The identified purpose of the meeting was to discuss: goals of care (47%), bad news (20%), failure of medical treatments (20%), and poor prognosis (13%).

Primary Outcome: Learner Skill Acquisition

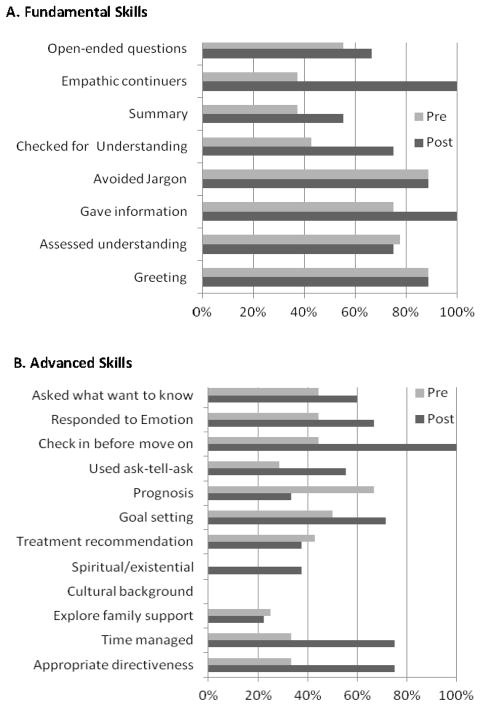

During the pre-course family meetings, participants on average used 49% of appropriate communication skills, while during the post-course meetings, they on average used 71% of appropriate skills. The average net gain of communication skills was 6.8 skills, which represents more than a 20% improvement in use of applicable skills. Of the 8 fundamental communication skills, participants, on average, used 64% of the applicable skills in the pre-course assessment and 82% in the post-course assessment (Figure 2A). For example, participants increased their use of “empathetic continuers” from 22% to 100%.

Figure 2. Participant Use of Skills Pre- and Post-Geritalk Coursea.

aThe percentages presented represent the number of participants who used each skill divided by the number who had appropriate opportunities to use the skill during the family meeting.

Note: A full description of each skill can be found on Appendix A page 2.

We noted that several skills were used by less than 50% of the participants during the pre-course family meeting assessment. We designated these as advanced communication skills. Of the advanced communication skills, participants, on average, used 34% of the applicable skills in the pre-course assessment and 53% in the post-course assessment (Figure 2B). Overall, the participants increased their use of the advanced skills in the post-course family meeting assessment. For example, participants increased their use of the skill “managed time” from 33% to 75% and “goal setting” from 50% to 71%. In addition, the participants increased their use of the skill “checked-in with the patient or family before moving on” from 44% to 100%.

Secondary Outcome: Deliberate Practice

Feedback after the Post-Course Family Meeting Assessment

The participants identified a variety of communication skills to practice during the post-course family meeting assessment. The majority (67%) identified a skill to respond to emotion. After the post-course family meeting assessment, the trained evaluators provided learner-centered feedback to each participant. The mean duration of feedback was 11 minutes (range, 10 to 15 minutes). In all cases, the participant successfully used the skill that they set out to practice deliberately. Furthermore, each participant was able to identify a challenging point in the conversation at which they did not know how to proceed. The ability to identify this challenging point demonstrates the participant’s ability to identify a learning opportunity and in turn, facilitate timely, formative feedback. Next, each participant identified a communication skill, which could assist them to navigate the challenging point in the future, further promoting independent deliberate practice.

Two-Month Follow-Up Assessment

In the two-month follow up assessment, the majority of the participants (78%) reported using each of the six skills from the SPIKES protocol5 (setting, perception, invitation, knowledge, empathic response, and strategy) “most of the time” to “always”. The participants reported using empathic continuers: “some of the time” (22%), “most of the time” (33%), and “always” (44%).

Participants reported using the advanced communication skills in the two months after the course. The participants reported that they “made a treatment recommendation based on the patient’s goals”: “most of the time” (67%) and “always” (33%). In addition, the majority reported using the advanced skills of “using silence appropriately” (89%) and “goal setting” (89%) either “most of the time” or “always”. This self-report demonstrated that participants continued to use the model of deliberate practice to improve communication skills.

The majority (78%) of participants reported that the Geritalk training was “very valuable” to improve communication skills. They reported that they have thought about what they learned in the Geritalk communication course: biweekly (11%), weekly (67%) and daily (22%). Six (67%) participants reported the overall evaluation of the course as “excellent” and the remaining 3 (33%) as “very good”.

CONCLUSIONS/LESSONS LEARNED

The Geritalk communication skills course is effective at teaching both the fundamental communication skills necessary to lead a family meeting and advanced communication skills. This is consistent with prior research demonstrating that communication skills can be taught.6

The course was effective particularly with participant acquisition of “empathic continuers” skill, which is emphasized throughout the 2-day course. This emphasis is based on prior research, which demonstrated that the patients of oncologists who use more empathic statements reported greater trust in their oncologists and improved satisfaction.10

In addition, the study demonstrates that the participants reported continued deliberate practice of these skills two months after the course. Specifically, the faculty encouraged the participants to identify a skill, try the skill, reflect on the skill practice and trouble-shoot alternative skills to use in challenging scenarios. The participants integrated the model of deliberate practice into their learning and continued to employ deliberate practice two months after the course. As highlighted by the Next Accreditation System4, this deliberate practice is critical to ensure that the participants continue to facilitate their communication skill mastery following their training.

Improvement in communication skills requires a model of experiential learning and deliberate practice. This is the first study using a real-time clinical assessment to demonstrate both participant skill acquisition and sustained skill practice following a communication skills course. Unlike similar studies using standardized patients, this is the first study to evaluate a communication skills training program using a direct observation real-time family meeting assessment tool during actual clinical encounters. Our study demonstrated that this assessment tool can be used to effectively evaluate a training program with overall participant skill acquisition. Furthermore, this tool can be used to evaluate individual participants with a wide range of skill and provide the framework for formative participant-centered feedback and need-based training, in real-time.

Nevertheless, this study has several limitations. This study was conducted at two sites with a small sample size. Furthermore, fellows in these fields are particularly motivated to improve communication skills, which are a cornerstone to their clinical work. Improving communication skills to enhance patient-physician communication is paramount in all medical fields. Moreover, it is difficult to account for the additional communication skills training which occurs outside of the Geritalk program. Finally, the communications skills evaluators also taught these fellows in clinical settings. To limit this bias, for each fellow, we ensured that at least one post-course evaluator was not a pre-course evaluator.

In conclusion, our assessment of the Geritalk program using actual clinical encounters demonstrates effective participant skill acquisition and sustained use of these skills. This modality of intensive training and real-time family meeting assessment could address the gap in patient-centered communication skills and may, in turn, offer a feasible and effective mechanism to improve patient satisfaction, quality of care, and outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This project was funded by the Plaza Jewish Community Chapel, New York, NY. In addition, Dr. Gelfman was supported by a T32 (T32HP10262) and is supported a National Palliative Care Research Center (NPCRC) Junior Faculty Career Development Award an R03 (R03 AG042344-01), and Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai’s Older American Independence Center (1P30AG28741-01) Research Career Development Core support. Dr. Kelley was supported by the Paul Beeson Career Development in Aging Research Award (1K23AG040774-01A1). Dr. Litrivis was supported by GACA K01 HP20483. Dr. Lim was supported by GACA K01 HP20465. Drs. Kelley, Litrivis, Lim and Gelfman have support from the Hartford Foundation Centers of Excellence in Geriatric Medicine Scholars Program. Dr. Smith was supported by the Clinical Translational and Science Award KL2TR000069.

Appendix A: Technical Appendix

Measuring a Communication Milestone: Development of a Real-Time Direct Observation Family Meeting Tool

Laura P. Gelfman, MD, Elizabeth Lindenberger, MD, Helen Fernandez, MD, MPH, Gabrielle R. Goldberg, MD, Betty B. Lim, MD, Evgenia Litrivis, MD, Lynn O’Neill, MD, Cardinale B. Smith, MD, MSCR and Amy S. Kelley, MD, MSHS

Background

Formal assessment of communication skills is limited or non-existent in many graduate medical education programs, including Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine fellowship programs. The few existing assessment tools do not target specific skills nor link to a real-time clinical encounter and, thereby allow for formative feedback.1 Given the focus of communication skills in the fields of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine, we developed a direct observation tool for faculty to evaluate an individual fellow’s communication skills during a clinical encounter and to provide real-time formative feedback following the encounter.

In this appendix, we describe the assessment tool’s development, the training for the tool’s use and the results from our pilot testing, including the feasibility of completing these direct real-time observations, the tool’s reliability, the evaluator satisfaction with tool and the ease of identifying areas for further training. In the study described in the accompanying manuscript, we used this assessment tool to compare the communication skills of the Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine fellows at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai before and after participation in the Geritalk program.2

Development of the Communication Skills Assessment Tool

From our Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine, we assembled 9 faculty members with communication skills expertise. First, the group compiled a broad checklist of all communication skills that a clinician may use and agreed upon the essential dimensions of the communication competencies with working definitions for each skill.3,4 This checklist, based on the validated ABIM mini-Clinical Evaluation Exercise (CEX) model5,6 of direct observation assessment, was designed to highlight communication skills gaps, so they could be addressed with further training.

With a comprehensive list of skills compiled, we created a user-friendly checklist of thirty-two distinct skills (Appendix B, page 1). Each skill is evaluated as “Yes” for a skill used, “No” for a skill not used or “NA” for not applicable. While our primary assessment was focused on the presence or absence of each skill, we included a subjective assessment, i.e., “beginner”, “intermediate” and “expert”, for each skill to account for the range of expertise in the use of each skill. Similarly, we included an “overall impression” 4-point scaled item at the end of the tool. These optional assessments are subjective, not grounded by concrete definitions and were outside the scope of our primary analysis.

We worked with two national communication skills experts7 to identify the 8 most “fundamental” skills, meaning the minimal skills required to competently conduct a family meeting. These skills include the following: 1) greeting, 2) assessed patient’s/family’s understanding, 3) gave information in a balanced manner and clarified misconceptions, 4) avoided the use of medical jargon, 5) checked for understanding, 6) used empathic continuers8 or statements that directly addressed the patients’ emotions, validated their feelings and invited further disclosure, 7) used open-ended questions, and 8) provided a summary at the end of the meeting and assessed understanding. In addition, we developed a training manual for the assessment tool, which included the working definition of each skill, and could be easily accessed during a family meeting observation (Appendix B, page 2).

In July 2011, we held a training session for 7 faculty members who would be conducting the family meeting observations. During this session, we held two mock family meetings. Prior to the mock family meeting, a brief synopsis of a case of a nursing home resident who was admitted to the hospital with respiratory failure and sepsis. An actor played the role of the patient’s daughter and two palliative care nurse practitioners participated as clinicians displaying an average trainee skill level. During the first mock family meeting, the faculty observed the clinical encounter while filling out our assessment tool. After the first mock family meeting, we debriefed the use of the tool, compared our assessments, and reached consensus on the use or lack of use of each skill. Once again, we made any necessary revisions to our working definition of each skill. This process was repeated following a second mock family meeting, at which point all faculty reached consensus on the assessment and the definition of each skill.

Separate training occurred for the one faculty member who instead watched the videotaped training session with the lead investigator (LPG). This faculty member similarly evaluated the two mock fellows and debriefed the evaluation. Consensus was achieved. In total, 8 faculty members completed the training of the assessment tool. The tool’s final version included a single item to assess the evaluator’s satisfaction with the tool.

Finally, we developed a study protocol to both assess the feasibility of identifying, scheduling and conducting an observed family meeting with each fellow and test the inter-rater reliability of the assessment tool. The protocol outlined each step from the identification of a real-time family meeting opportunity through the completed assessment by two evaluators. Each fellow contacted the research coordinator with the date, time and location of a family meeting. The lead investigators ensured that two trained evaluators would be present for each meeting.

Immediately before the family meeting, each fellow completed a brief five-item self-assessment of her competence in delivering bad news and conducting goals of care discussions, and the extent of her prior experience in leading family meetings.1,9 Next, the evaluators met briefly with the team conducting the meeting to ensure that the fellows led the meeting. During the family meeting, each evaluator completed the evaluation tool independently. Following the meeting, the two evaluators compared assessments and resolved discrepancies through team adjudication to reach consensus. The two independent evaluation forms and the consensus form were then submitted to the research coordinator. The Institutional Review Board for the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai approved this study. We held an information session about the research study in July 2011, and, subsequently, informed consent was obtained.

Initial Testing

Of the ten fellows recruited, 100% agreed to participate and completed the study. Eight were female (80%). The median age was 34 years (range, 29 to 49). All were first-year fellows in Geriatrics or Palliative Medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai or the James J. Peters VA Medical Center. Sixty percent reported prior communication training. Prior to the observed family meetings, 30% self-assessed their competence with giving bad news to a patient or family member as “competent to perform independently”. Twenty percent self-assessed their competence with discussing goals of care with a patient or family member as “competent to perform independently”. The fellows reported the meeting goal as: giving bad news (24%), poor prognosis (18%), failure of medical treatments (18%), and transitions in goals of care (40%).

In 5 months, 10 (100%) fellows completed family meeting assessments. Five (50%) fellows identified a meeting more than 24 hours in advance, with a range of advanced notification from 90 minutes to 72 hours. The average meeting length was 45 minutes. The mean inter-rater reliability is 0.68 and the two paired independent evaluators reached consensus in all cases. Of the 20 assessments (each fellow was evaluated independently by 2 trained faculty members), the evaluators were “extremely” (65%) or “moderately” (35%) satisfied with the tool.

In spite of the fellows’ widely varying experience with communication skills, using this tool, the trained evaluators identified specific areas for further training for each fellow. Of the 8 fundamental communication skills, the majority completed 4 skills and a minority completed the other 4 skills. None completed all 8 skills. For the skill of “greeting”, 80% used the skill. For the more advanced skill of empathic continuers8, only 20% used the skill. This demonstrates that the tool can evaluate a diverse group of learners and identify opportunities for improvement.

Conclusions

In our institution, this real-time communication skills assessment and feedback tool is feasible, reliable, and guides formative feedback and need-based training. In this pilot study, the average time commitment was less than one hour and the trained evaluators were satisfied with the tool. This tool was able to identify opportunities for a wide skill levels and there was no “ceiling effort” or the failure to fully measure the extent of the most skilled fellows’ communication skills because the tool was not challenging or comprehensive enough. Furthermore, the data from the collective group of fellows will allow educators to identify high-yield areas for further training as well as the individual data to develop targeted learning.

In spite of the benefits to fellowship programs, our conclusions have several limitations. This study was conducted at a single institution with highly motivated educators in communication. We have yet to establish external validity in other settings. In addition, the presence of 2 evaluators at each clinical family meeting presents a burden on the clinical staff. Nevertheless, we believe that one evaluator would be sufficient in the clinical setting. Additionally, the assessment tool only accounts for the trained evaluator’s perception and not those of other participants including clinicians, patients nor families.

This assessment tool offers a promising solution to ensure rigorous assessment of communication skills of trainees. The tool is feasible to use, reliable and allows for identification of areas for further training. This tool may have a broader audience, beyond Geriatric and Palliative Medicine.10 Overall, the tool’s implementation will assist program directors to assess trainees’ communication skills competencies, encourage developmental assessment and provide faculty with observable behaviors for assessment. Future research is needed to establish external validity before expanding this tool’s use. Ultimately, we aim to disseminate the tool to other fellowship programs seeking a novel and evidence-based communication skills assessment tool.

Acknowledgements: We wish like to acknowledge the Palliative Medicine and Geriatrics fellows for their participation in this research project.

Funding/Support: This project was funded by the Plaza Jewish Community Chapel, New York, NY. In addition, Dr. Gelfman was supported by a T32 (T32HP10262) and is supported a National Palliative Care Research Center (NPCRC) Junior Faculty Career Development Award an R03 (R03 AG042344-01), and Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai’s Older American Independence Center (1P30AG28741-01) Research Career Development Core support. Dr. Kelley was supported by the Paul Beeson Career Development in Aging Research Award (1K23AG040774-01A1). Dr. Litrivis is supported by GACA K01 HP20483. Dr. Lim is supported by GACA K01 HP20465. Drs. Kelley, Litrivis, Lim and Gelfman have support from the Hartford Foundation Centers of Excellence in Geriatric Medicine Scholars Program. Dr. Smith was supported by the Clinical Translational and Science Award KL2TR000069.

Previous presentations: The authors presented this material in the form of a poster presentation at the 2012 Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Education Research Day and the 2012 American Geriatric Society Annual Assembly.

- 1.Han PK, Keranen LB, Lescisin DA, Arnold RM. The palliative care clinical evaluation exercise (CEX): an experience-based intervention for teaching end-of-life communication skills. Acad Med. 2005 Jul;80(7):669–676. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200507000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelley AS, Back AL, Arnold RM, et al. Geritalk: communication skills training for geriatric and palliative medicine fellows. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012 Feb;60(2):332–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03787.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. SPIKES-A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5(4):302–311. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-4-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, et al. Efficacy of communication skills training for giving bad news and discussing transitions to palliative care. Arch Intern Med. 2007 Mar 12;167(5):453–460. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norcini JJ, Blank LL, Arnold GK, Kimball HR. The mini-CEX (clinical evaluation exercise): a preliminary investigation. Ann Intern Med. 1995 Nov 15;123(10):795–799. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-10-199511150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hawkins RE, Margolis MJ, Durning SJ, Norcini JJ. Constructing a validity argument for the mini-Clinical Evaluation Exercise: a review of the research. Acad Med. 2010 Sep;85(9):1453–1461. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181eac3e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Back A, Arnold R, Gelfman LP, Kelley AS. Identification of fundamental communication skills (personal communication) Mar 29, 2012.

- 8.Pollak KI, Arnold RM, Jeffreys AS, et al. Oncologist communication about emotion during visits with patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Dec 20;25(36):5748–5752. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weissman DE, Ambuel B, Norton AJ, Wang-Cheng R, Schiedermayer D. A survey of competencies and concerns in end-of-life care for physician trainees. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1998 Feb;15(2):82–90. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(97)00253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Medicine AfAI. [Accessed December 10, 2012];Internal Medicine End of Training EPAs. 2012 http://www.im.org/AcademicAffairs/milestones/Pages/EndofTrainingEPAs.aspx.

Appendix B: Family Meeting Communication Assessment Tool (FaMCAT) and Training Manual

| Observer:_________________________________________ | Start time:____ | End time: ____ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| To be completed by each faculty member observing the family meeting: | ||||||

| Family Meeting Skills Demonstrated | NA | No | Yes | Beginner | Intermediate | Expert |

| SPIKES | ||||||

| (S) Setting: | ||||||

| Meeting preparation | ||||||

| Prepared room | ||||||

| Body language | ||||||

| Greeting | ||||||

| (P) Perception: | ||||||

| Assessed patient’s/family’s understanding | ||||||

| (I) Invitation: | ||||||

| Asked what the patient/family wants to know | ||||||

| Gave a “warning shot” | ||||||

| (K) Knowledge: | ||||||

| Gave information (about current medical condition) | ||||||

| Avoided use of medical jargon | ||||||

| (E) Empathic Response: | ||||||

| Responded to emotions | ||||||

| Wish statements (for unrealistic tx goals) | ||||||

| (S) Strategy: | ||||||

| Check-in before moving on | ||||||

| Check for understanding | ||||||

| Summary | ||||||

| Plan | ||||||

| Other skills: | ||||||

| Used empathic continuers (NURSE-at least one) | ||||||

| Used empathic terminators | ||||||

| Used Ask-Tell-Ask | ||||||

| Prognosis (delivered as range) | ||||||

| Used silence appropriately | ||||||

| Used open-ended questions (tell me about…) | ||||||

| Goal setting (in context of ongoing or future care) | ||||||

| Made a treatment recommendation | ||||||

| Spiritual and existential concerns | ||||||

| Patient’s/Family’s cultural background | ||||||

| Explored patient identity/family support | ||||||

| Mediated conflicts that arise | ||||||

| Discussed the 5 things | ||||||

| Discussed what to expect in dying process | ||||||

| Time managed | ||||||

| Used appropriate level of directiveness | ||||||

| Leadership (interdisciplinary team/consultants) | ||||||

| Overall Impression: | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Needs instruction before further meetings | Perform only with faculty assistance | Competent to perform independently | Performs with expertise |

| FaMCAT: Criteria for Yes/No/NA: Criteria for Yes/No/NA | |

| SPIKES | |

| (S) Setting: | |

| Meeting preparation | Communicated with others caring for patient before meeting, negotiate roles, reached consensus on information, i.e. prognosis/treatment, identify decision-maker(s) |

| Prepared room | Assures comfort, appropriate setting, allows for interpersonal space, provides tissues and/or water If made effort, then yes/no: if no effort, then N/A |

| Body language | Sat down, eye contact, open posture, demonstrates being engaged |

| Greeting | Makes appropriate introductions, explains role (as palliative care fellow or geriatrics fellow) |

| (P) Perception: | Asked what the patient/family already knew/assessed patient’s/family’s understanding |

| (I) Invitation: | Asked what the patient/family wants to know N/A if patient asks for information |

| Gave a “warning shot” to indicate bad news will be given or to address concerns about what happened in the past | |

| (K) Knowledge: | Gave information (in balanced manner, clarified misconceptions or misunderstandings) about current medical condition |

| Avoided use of medical jargon | |

| (E) Empathic Response: | Responded to emotions |

| Wish statements for unrealistic treatment goals | |

| (S) Strategy: | Check-in before moving on |

| Checked for understanding | |

| Summary | Provided summary at end of meeting, assessed understanding |

| Plan | Created follow-up plan, gave business card, arranged for next meeting |

| OTHER SKILLS: | |

| Used empathic continuers | Statements that directly address patients’ emotions, validate their feelings, and invite further disclosure; used at least one nurse statement [(N)ame, (U)nderstand, (R)espect, (S)upport, (E)xplore] |

| Used empathic terminators | Statements that avoid the emotion or change the topic, or not respond to cues with expressions of empathy |

| Used Ask-Tell-Ask | Evaluating quality of ask-tell-ask, not quantity |

| Discussed Prognosis | Assessed desire for prognosis/life expectancy, delivered as range |

| Use of silence | Allowed patients and/or family members to respond to questions, nods head/verbal cues, appreciates and allows for silences/paused |

| Used open-ended questions | For example, “tell me about your loved one…” |

| Goal setting | Attempted to elicit patient’s or family member’s goals and expectations in context of ongoing or future care |

| Made a treatment recommendation | Tailored treatments to elicited patient’s goals/values as appropriate—i.e. chemotherapy, CPR, treatment alternatives, artificial hydration/nutrition, or hospice care |

| Spiritual and existential concerns | Assessed spiritual and existential concerns, offered chaplaincy |

| Patient’s/Family’s cultural background | Assessed patient’s cultural background and concerns |

| Explored patient identity/family support | Explored patient identity, asked patient/family about personal support |

| Mediated conflicts and anger | Among patient, family or interdisciplinary team, addressed medical errors |

| Discussed the 5 things | I love you, I forgive you, Please forgive me, Thank you, Goodbye |

| Discussed what to expect in the dying process | Explained what would happen if withdraw specific treatment, gave information about dying process |

| Managed time | Managed time effectively, balanced time constraints with needs of patient/family |

| Used appropriate level of directiveness | Guided conversation with patient and family |

| Leadership | Ran meeting appropriately, engaged other members of interdisciplinary team/consultants |

Footnotes

No competing financial interests exist.

Author Contributions: LG, EL and AK were involved in the development of the study concept and design, acquisition of subjects and data, analysis and interpretation of data. All authors participated as course faculty, family meeting assessment observers and contributed to the development and editing of the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008 Oct 8;300(14):1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang B, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, et al. Health care costs in the last week of life: associations with end-of-life conversations. Arch Intern Med. 2009 Mar 9;169(5):480–488. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weeks JC, Cook EF, SJOD, et al. Relationship between cancer patients’ predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences [see comments] JAMA. 1998;279(21):1709–1714. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, Flynn TC. The next GME accreditation system--rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med. 2012 Mar 15;366(11):1051–1056. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1200117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Back ALAR, Tulsky J. Mastering Communication with Seriously Ill Patients. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, et al. Efficacy of communication skills training for giving bad news and discussing transitions to palliative care. Arch Intern Med. 2007 Mar 12;167(5):453–460. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelley AS, Back AL, Arnold RM, et al. Geritalk: communication skills training for geriatric and palliative medicine fellows. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012 Feb;60(2):332–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03787.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weissman DE, Ambuel B, Norton AJ, Wang-Cheng R, Schiedermayer D. A survey of competencies and concerns in end-of-life care for physician trainees. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1998 Feb;15(2):82–90. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(97)00253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han PK, Keranen LB, Lescisin DA, Arnold RM. The palliative care clinical evaluation exercise (CEX): an experience-based intervention for teaching end-of-life communication skills. Acad Med. 2005 Jul;80(7):669–676. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200507000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tulsky JA, Arnold RM, Alexander SC, et al. Enhancing communication between oncologists and patients with a computer-based training program: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Nov 1;155(9):593–601. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-155-9-201111010-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]