Abstract

Background

Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma (aRMS) is a myogenic childhood sarcoma frequently associated with a translocation-mediated fusion gene, Pax3:Foxo1a.

Methods

We investigated the complementary role of Rb1 loss in aRMS tumor initiation and progression using conditional mouse models.

Results

Rb1 loss was not a necessary and sufficient mutational event for rhabdomyosarcomagenesis, nor a strong cooperative initiating mutation. Instead, Rb1 loss was a modifier of progression and increased anaplasia and pleomorphism. Whereas Pax3:Foxo1a expression was unaltered, biomarkers of aRMS versus embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma were both increased, questioning whether these diagnostic markers are reliable in the context of Rb1 loss. Genome-wide gene expression in Pax3:Foxo1a,Rb1 tumors more closely approximated aRMS than embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. Intrinsic loss of pRb function in aRMS was evidenced by insensitivity to a Cdk4/6 inhibitor regardless of whether Rb1 was intact or null. This loss of function could be attributed to low baseline Rb1, pRb and phospho-pRb expression in aRMS tumors for which the Rb1 locus was intact. Pax3:Foxo1a RNA interference did not increase pRb or improve Cdk inhibitor sensitivity. Human aRMS shared the feature of low and/or heterogeneous tumor cell pRb expression.

Conclusions

Rb1 loss from an already low pRb baseline is a significant disease modifier, raising the possibility that some cases of pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma may in fact be Pax3:Foxo1a-expressing aRMS with Rb1 or pRb loss of function.

Keywords: Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma, Disease modifier, Sarcoma, Rb1, Spindle cell, Retinoblastoma

Background

The pediatric and young adult tumor, rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS), is increasingly being understood to represent a spectrum of diseases that are distinguished not only by histological appearance but also by mutational profile and cell of origin [1-3]. Two major subtypes of RMS exist, alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma (aRMS) and embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (eRMS) [4]. aRMS is commonly associated with a translocation-mediated PAX3:FOXO1A fusion gene [4], whereas the best described initiating mutation in eRMS is p53 loss [1]. The rarer anaplastic variant of RMS is incompletely understood, although the adult pleomorphic RMS variant is now thought to be often driven by Ras [5].

A high frequency of retinoblastoma (Rb1) gene mutation has been reported in a subset of human eRMS [6], and we previously reported that Rb1 nullizygosity in combination with other mutations may lead to loss of differentiation in eRMS and spindle cell sarcomas [1]. However, the role of Rb1 loss in aRMS remains controversial [6,7]. In this study, we employ conditional mouse genetics to define the role of Rb1 in the initiation and progression of aRMS.

The primary aim of this study was to determine the role of Rb1 loss in tumor initiation and progression using conditional genetic mouse models of aRMS. We hypothesized that Rb1 plays a critical role in tumor initiation, but instead identified Rb1 loss as a disease modifier resulting in not only anaplasia but also a switch from aRMS to pleomorphic RMS identity. Our studies also point to an inherently low expression of pRb in aRMS, even when the Rb1 locus is intact.

Methods

Mice

All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio or the Oregon Health & Science University. The Myf6Cre, conditional Pax3:Foxo1a, conditional p53, and conditional Rb1 mouse lines and corresponding genotyping protocols have been described previously [2,8-12]. Tumor-prone mice were visually inspected every 2 days for tumors because of the fulminant onset in these models. Tumor staging was based upon a previously described adaptation of the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group staging system [1].

Human subjects

The Oregon Health & Science University institutional review board has made a determination that the use of de-identified tumor samples from the Nationwide Children’s Hospital Biopathology Center or Children’s Oncology Group Biorepository (both sources that consent patients for research tissues directly) is not human subject research because these activities do not meet the definition of human subject per 45 CFR 46.102(f).

Survival analysis

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of the mice was performed with the endpoint being the development of RMS. The log-rank test was utilized to determine the statistical significance (P < 0.05). Both analyses were performed with Systat12 software (Systat Software Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RNA isolation and quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

RNA was isolated from mouse tumors and wildtype vastus lateralis skeletal muscle using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was then processed by RNAeasy-Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and was reverse transcribed using a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Fermentas, Ontario, Canada). For Figure 1A, qRT-PCR analyses were performed on an ABI7700 instrument (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) by a Taqman assay for mouse Pax3:Foxo1a expression. The mean of three experimental replicates per specimen was used to calculate the ratio of gene of interest/Gapdh expression for the Taqman assay, as described previously [11]. For Figure 1B, qRT-PCR was performed using a standard 96-well assay or custom Format-24 Taqman arrays (ABI and Assuragen, Austin, TX, USA) using mouse or human GAPDH as a control for relative gene expression, and 18S RNA as a quality control. Statistical considerations for this format assay have been previously described [1]. Probesets for mouse samples were 18S-Hs99999901_s1, GAPDH_Mm99999915_g1, myog_Mm00446194_m1, Cdh3_Mm01249209_m1, MYCN_Mm00627179_m1, EGFR_Mm00433023_m1, Fbn2_Mm00515742_m1, tcfap2b_Mm00493468_m1, Hmga2_Mm04183367_g1 and Rb1_Mm00485586_m1.

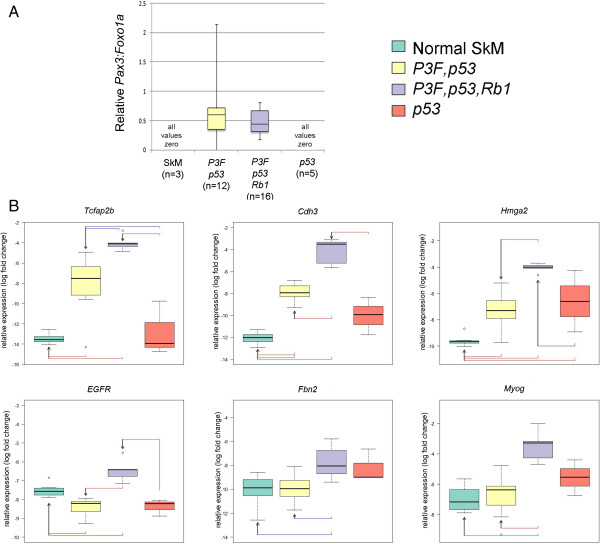

Figure 1.

Addition of Rb1 inactivation to Pax3:Foxo1a activation and p53 deletion changes gene expression features for tumors in the Myf6cre lineage. (A) qRT-PCR of Pax3:Foxo1a shows similar expression level in strains with Pax3:Foxo1a,p53 versus Pax3:Foxo1a,p53,Rb1 mice. (B) Expression of tumor subtype-specific markers in Pax3:Foxo1a,p53 versus Pax3:Foxo1a,p53,Rb1 versus p53 mice.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Tissues fixed in 10% buffered formalin were paraffin-embedded and sectioned at 3.5 μm thickness. Paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin or by Gomori Trichrome. For MyoD and Myogenin immunohistochemistry, staining was performed using the M.O.M. Immunodection Kit Staining Procedure (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions using antigen unmasking. The myogenin monoclonal primary antibody (5D7 supernatant; Developmental Hybridoma Studies Bank, Iowa City, IA, USA) was used at a concentration of 1:50. The Desmin monoclonal primary antibody (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) was used at a concentration of 1:200. For histology, we evaluated 24 Pax3:Foxo1a,p53,Rb1 tumors, six Myf6Cre,Pax3:Foxo1a,Rb1 tumors and two Myf6Cre,Rb1 tumors (as stated in Results and detailed in our prior publication [13], most Myf6Cre,Rb1 mice develop pituitary adenomas well ahead of sarcoma development). For the tissue microarray obtained from the Children’s Oncology Group Biorepository, the section was pretreated with Cell Conditioning 1 for 64 minutes as antigen retrieval and then stained with rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-pRb (Ser807/811, catalogue number9308; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA) at a dilution of 1:200 followed by staining on a Ventana ES auto stainer (Ventana, Tucson, AZ, USA) and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine detection.

Cell culture

To establish primary tumor cell cultures, mouse-derived tumors were digested with 1% collagenase IV (Sigma Aldrich) overnight, rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline, and then plated on 10 cm dishes. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s media (DMEM; Sigma Aldrich) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. The C2C12 mouse myoblast cell line was purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA) and maintained in the same culture conditions as primary tumor cell cultures.

Cell viability screens

Mouse-derived primary cell cultures at passage ≤5 plated into 96-well plates using DMEM culture medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. After 12-hour incubation, vehicle or drug was applied to the cells over a range of concentrations from 0.1 to 10,000 nM in triplicate. Panibinostat, PD0332991, SAHA and SNS-032 were purchased from a commercial source (Selleckchem, Houston, TX, USA). Following 72-hour incubation, an MTS viability assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (CellTiter 96® AQueous MTS Reagent; Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and quantified using a Synergy 2 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (Biotek, Winooski, VT, USA) and subsequently analyzed using Microsoft Excel. For Figure 2E, group contrasts (shC01 (n = 14) with shC05 (n = 14), and shY08 (n = 14) with shY09 (n = 14)) with regard to mean cell viability were carried out with analyses of covariance of log cell viability in terms of log concentration and group; four data points with negative cell viability for shC01 (n = 2) and shC05 (n = 2) were removed prior to analysis. After pooling shC01 with shC05 and shY08 with shY09, and removing the four data points with negative cell viability, the resulting two groups (shC, n = 24; and shY, n = 28) were contrasted with regard to mean cell viability with a similar analysis of covariance model in log units. All statistical testing was two-sided with a significance level of 5%.

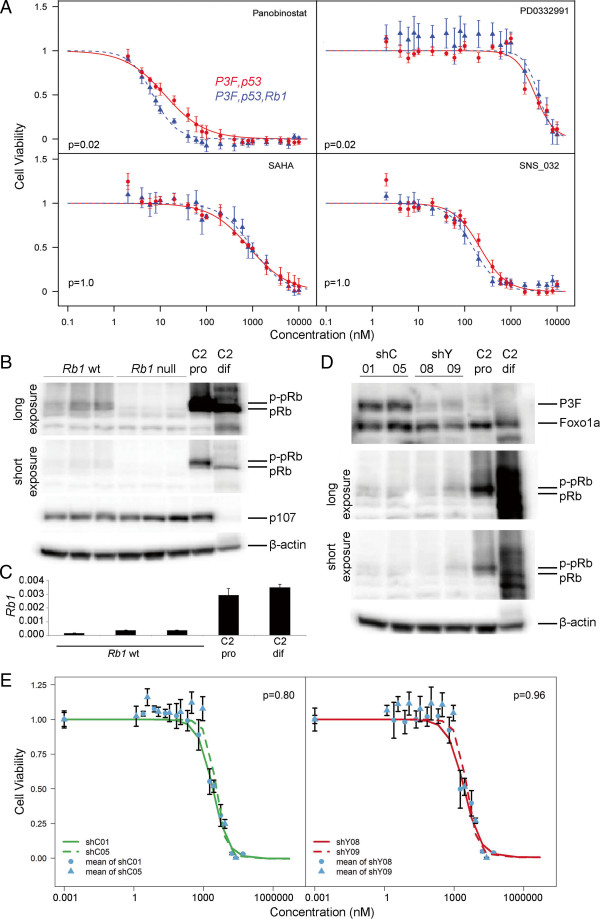

Figure 2.

Sensitivity to CDK4/6 inhibitors is not determined by Rb1 status or Pax3:Foxo1a expression. (A) Median inhibitory concentration (IC50) determinations by cell viability assays for Pax3:Foxo1a,p53 (n = 3) and Pax3:Foxo1a,p53,Rb1 (n = 3) RMS primary cell cultures treated with Panobinostat, PD0332991, SAHA and SNS-032. P values based on a linear model of cell viability in terms of genotype, concentration and the genotype by concentration interaction with Bonferroni multiple testing correction. IC50 of PD0332991 was approximately 3 μM for both groups. Error bars, mean ± 1 standard error of the mean. (B) Western blotting for Rb1 wildtype primary tumor cell cultures (n = 3) and Rb1 null RMS primary tumor cell cultures (n = 3). C2, C2C12 mouse myoblasts; pro, proliferating culture conditions; dif, differentiation culture conditions. pRb and phospho-pRb (p-Rb) are distinguished by mobility on a 5% gel using a single antibody. Whereas pRb expression is diminished in RMS cell cultures relative to C2C12 proliferating myoblasts, p107 expression is comparable. (C) Reduced relative expression levels of Rb1 by qRT-PCR in Rb1 wildtype aRMS primary cell cultures relative to C2 pro or dif. 3 independent aRMS primary cultures. All measurements performed in triplicate. P ≤0.035 for comparisons of aRMS cultures with either C2 pro or dif. (D) Two independent shRNA clones for eYFP knockdown (shY08, shC09; also achieves Pax3:Foxo1a knockdown, see Results) were compared with shRNA controls (shC01, shC05) for expression of pRb, which was unaltered. P3F, Pax3:Foxo1a. (E) Insensitivity to PD0332991 was not improved in Pax3:Foxo1a knockdown tumor cell culture clones (IC50 of all clones ~2.75 μM). Specifically, shC01 and shC05 independent clones did not differ significantly, shY08 and shY09 independent clones did not differ significantly, nor did the shC versus shY clones differ significantly with regard to mean cell viability.

Immunoblotting

Rb1 wildtype aRMS primary tumor cell cultures, Rb1 null aRMS primary tumor cell cultures and C2C12 cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum and lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing both protease and phosphatase inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich) at the proliferation stage (50 to 70% confluency). C2C12 cells were cultured in DMEM with 2% house serum for 7 days and lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer as for C2C12 differentiation. The lysates were homogenized and centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 10 minutes. The resulting supernatants were used for immunoblot analysis by mouse anti-β-actin (catalogue number A1978; Sigma), mouse anti-pRb (catalogue number 554136; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), rabbit anti-p107 (catalogue number sc-318; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) and goat anti-FKHR (catalogue number sc-9808; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). For Figure 2B,D, β-actin was run as a separate blot (using the same amount of protein loaded per well as the pRb/p107 blot) rather than stripping because achieving separation of pRb and phospho-pRb on a 5% gel required running β-actin off the gel.

Generation of shRNA tumor cell culture clones

To establish shRNA knockdown clones of primary tumor cell cultures, we used MISSION® pLKO.1-puro eGFP shRNA Control Transduction Particles (catalogue number SHC005V; Sigma Aldrich) for Pax3:Foxo1a knockdown and MISSION® pLKO.1-puro Non-Mammalian shRNA Control Transduction Particles (catalogue number SHC002V; Sigma Aldrich) as the control, respectively. shRNA transfections and clonal selection were carried out according to the manufacturer’s recommended procedures. Mouse RMS primary cell cultures were plated at 1.8 × 106 cells per 150 mm dish. After 24 hours, hexadimethrine bromide was added (8 μg/ml, catalogue number H9268; Sigma Aldrich), followed by each particle solution (Multiplicity of Infection 0.5). After another 24 hours, media were removed and fresh media were added. The following day, puromycin was added (5 μg/ml, catalogue number P8833; Sigma Aldrich). Puromycin-resistant clones were selected by cloning rings at day 14 (shC) and day 17 (shY), with continuous puromycin selection at all times.

Principal component analysis gene selection and microarray analysis

Gene expression analysis was performed using Illumina Mouse Ref-8 Beadchip v1. Microarray datasets were obtained from the GEO database [GEO:GSE22520] from our previous study [1]. We employed similar methods for microarray data analysis and the principal component analysis (PCA) described by Rubin and colleagues [1]. Briefly, we first performed rank invariant set normalization on mouse gene expression data, and then selected 12,370 probes out of 24,613 probes from Mouse Ref-8 beadchip with average log2 intensity >6 and standard deviation >0.1 over 25 samples. We also derived four gene sets for PCA from different studies (Table 1) to show the relevance of aRMS-like and eRMS-like tumors between mouse and human. All four signature gene sets are first mapped from human to mouse gene symbols via homolog utility at MammalHom (Table 1), and then map to microarray probes if the corresponding probes exist. The reduction of gene count was due simply to the microarray platform difference. These gene lists are presented in Additional file 1.

Table 1.

Principal component analysis from different 4 studies

| Dataset | Number of signature genes | Number of genes mapped to microarray | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differentially expressed genes in fusion-positive aRMS vs. fusion-negative eRMS |

121 |

83 |

Laé and colleagues [19] |

| Genes differentially expressed between PAX-FOXO1A and fusion-negative RMS cell lines |

79 |

55 |

Davicioni and colleagues [14] |

| Williamson F1/F2 metagenes |

45 |

32 |

Williamson and colleagues [20] |

| Genes conserved in mouse and human Pax3:Foxo1a-positive aRMS | 58 | 47 | Nishijo and colleagues [11] |

All human gene symbols were translated to their homologues in mouse using MammalHom (http://depts.washington.edu/l2l/mammalhom.html) and then mapped to the microarray annotation. aRMS, alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma; eRMS, embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma; RMS, rhabdomyosarcoma.

Microarray datasets were obtained from the GEO database [GEO:GSE22520] from our previous study [1]. We employed similar methods for microarray data analysis and the PCA described by Rubin and colleagues [1]. Briefly, we first performed rank invariant set normalization on mouse gene expression data and applied PCA to the mouse data, respectively, using the selected genes listed in four aRMS versus eRMS signature gene sets. PCA was performed using the MATLAB Bioinformatics toolbox (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA).

For the comparison between six samples of Pax3:Foxo1a,p53 tumors (aRMS) and six samples of Pax3:Foxo1a,p53,Rb1 tumors (other RMS), the normalized expression data were applied to a t test and differential expressed genes between aRMS and other RMS tumors were identified with the criterion of fold-change >2 and P < 0.05. All bioinformatics tasks were performed with MATLAB/Bioinformatics Toolbox, unless otherwise noted.

Results

Rb1 inactivation in combination with Pax3:Foxo1a activation and p53 inactivation causes highly aggressive rhabdomyosarcoma tumors

To investigate the role of Rb1 in aRMS, we restricted our conditional model studies to the Myf6 lineage using Myf6cre on the basis of our prior studies indicating the maturing myoblast to be the likely aRMS cell of origin [2]. Rb1 homozygous deletion in the Myf6Cre lineage can lead to pituitary macroadenomas [14], and therefore sarcoma-free survival (instead of tumor-free survival) is presented in Figure 3. We first inactivated both alleles of Rb1 in Myf6-expressing maturing myofibers (designated hereafter as Rb1 mice). Animals were born in normal Mendelian ratios and developed normally throughout adolescence and early adulthood (Figure 3A). As reported previously [2], for mice with only Pax3:Foxo1a homozygous activation or only p53 homozygous inactivation (Pax3:Foxo1a or p53 mice, respectively), aRMS occurred but at very low frequency (Figure 3A). Also as reported previously, simultaneously inactivating p53 dramatically increased the frequency and decreased the latency of aRMS tumors in Pax3:Foxo1a-expressing mice [2]. However, Rb1 loss had no cooperative effect on the tumor development with either Pax3:Foxo1a activation or with p53 inactivation (Figure 3B). Interestingly, when Rb1 loss was combined with Pax3:Foxo1a activation and p53 inactivation concurrently, the overall latency of tumor formation decreased (Figure 3B). Taken together, these data suggested that Rb1 loss is a modifier of disease progression – but not a necessary and sufficient mutational event, nor a strong cooperative initiating mutation.

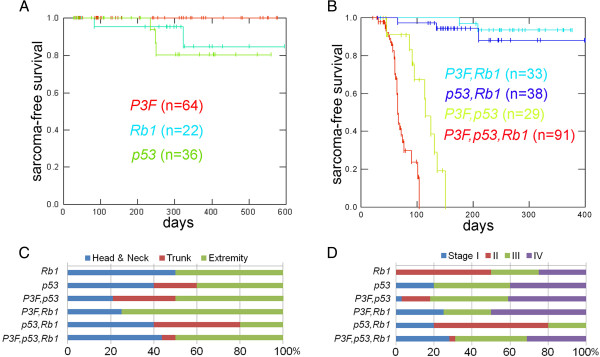

Figure 3.

Rb1 inactivation decreases latency of rhabdomyosarcoma in with the context of dual Pax3:Foxo1a activation and p53 inactivation. (A) Kaplan–Meier survival curve of RMS-free survival in mice with Rb1 inactivation, p53 inactivation or Pax3:Foxo1a activation in the Myf6cre lineage. Any of these genetic events alone is generally not sufficient for the development of RMS. (B) Survival analysis of Pax3:Foxo1a,p53; Pax3:Foxo1a,Rb1, and p53,Rb1 mice (all using Myf6cre). The results suggest that Rb1 loss, unlike p53 inactivation, has no cooperative effects with Pax3:Foxo1a activation for the development of RMS. (C) Addition of Rb1 inactivation to Pax3:Foxo1a activation and p53 deletion significantly accelerated rhabdomyosarcomagenesis compared with Pax3:Foxo1a,p53 mice (log-rank test, P <0.01; all experiments using Myf6cre). The mean latency for sarcoma development was 67 days in Pax3:Foxo1a,p53,Rb1 mice and 107 days in Pax3:Foxo1a,p53 mice. (D) Tumor stage (top) and anatomical site (bottom) of mice corresponding to (A) to (C).

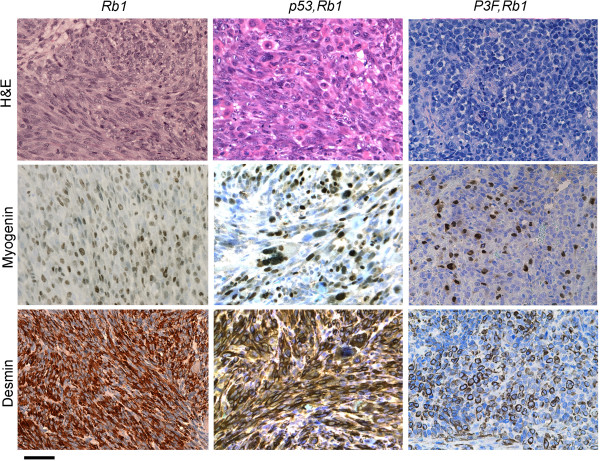

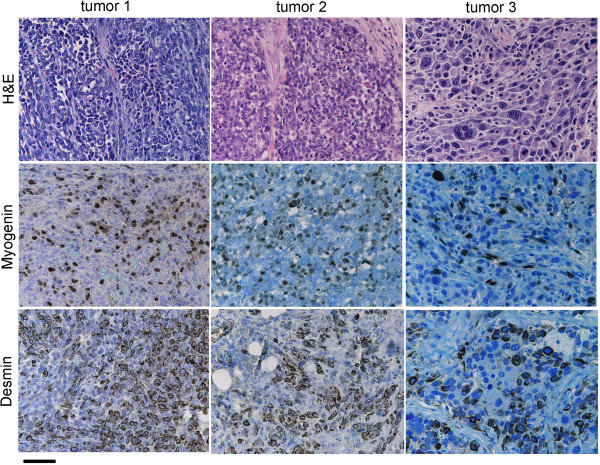

Figure 3C,D show the anatomical sites and tumor stages in each genetically engineered model. Pax3:Foxo1a,p53,Rb1 mice demonstrated slightly more head/neck tumors and more large, nonmetastatic stage I tumors compared with Pax3:Foxo1a,p53 tumors for which the Rb1 locus was intact. Histologically, Pax3:Foxo1a,Rb1 tumors consisted of myogenin and desmin-positive small round blue cells, consistent with the diagnosis of aRMS, whereas Rb1 tumors were represented as mixed spindle and small round blue cells with only focal regions of myogenin or desmin positivity consistent with either RMS not otherwise specified or poorly differentiated malignant epithelioid neoplasms (Figure 4). Similarly, p53,Rb1 tumors appeared as mixed spindle and small round blue cell histology with myogenin and desmin positivity and occasional rhabdomyoblasts, consistent with pleomorphic RMS (Figure 4). In contrast, Pax3:Foxo1a,p53,Rb1 tumors sometimes retained histological identity as aRMS, but often had a mixed epithelioid/spindle cell morphology and variable myogenin and desmin staining (Figure 5). Pleomorphic histomorphology was present to varying degrees, often very extensive. When not consistent with aRMS, the spectrum of diagnoses included RMS not otherwise specified, pleomorphic RMS and undifferentiated spindle cell sarcoma.

Figure 4.

Histological analysis of rare Rb1 and Pax3:Foxo1a,Rb1 tumors. A representative Rb1 tumor (left) shows spindle cell morphology with high percentage of myogenin-positive and desmin-positive cells consistent with eRMS, whereas a representative Pax3:Foxo1a,Rb1 tumor (right) consists of small round blue cells that are only rarely myogenin and desmin positive (best region shown in figure), consistent with the diagnosis of poorly differentiated malignant epithelioid neoplasm. Scale bar: 40 μm. H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

Figure 5.

Histological analysis of Pax3:Foxo1a,p53,Rb1 tumors. Histological analysis of Pax3:Foxo1a,p53,Rb1 tumors demonstrate small round blue cells with positive myogenin and desmin staining, consistent with aRMS (tumor 1 and tumor 2). However, some tumors showed highly anaplastic morphology (tumor 3) and were diagnosed as pleomorphic RMS. The Pax3:Foxo1a transcript level by qRT-PCR for the right tumor was nearly the same as for the middle tumor (data not shown). Scale bar: 40 μm. H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

Addition of Rb1 inactivation to Pax3:Foxo1a activation and p53 deletion creates a bi-phenotypic profile using traditional aRMS and eRMS biomarkers

Since Pax3:Foxo1a,p53 and Pax3:Foxo1a,p53,Rb1 tumors had differences in histomorphology, we examined whether Rb1 inactivation altered the expression level of Pax3:Foxo1a, thereby potentially altering expression of downstream target genes. Instead, Pax3:Foxo1a,p53 and Pax3:Foxo1a,p53,Rb1 tumors expressed the same level of Pax3:Foxo1a (Figure 1A). We also examined aRMS and eRMS-specific gene expression from tumors (Figure 1B). Rb1 inactivation increased the expression of two markers, Tcfap2 (Transcription factor AP-2b) and Cdh3 (Placental P-cadherin), which have been identified as direct target genes of PAX3:FOXO1A in aRMS [14,15]. Paradoxically, Pax3:Foxo1a,p53,Rb1 tumor also showed an increased level of Hmga2 (Transcription factor high mobility group A), a marker of fusion-negative aRMS [15]. The expression level of EGFR (Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor) and Fbn2 (Fibrillin-2) as specific markers for eRMS [16,17] were also paradoxically increased in Pax3:Foxo1a,p53,Rb1 tumors. Furthermore, Pax3:Foxo1a,p53,Rb1 tumors also had increased expression of Myogenin, a marker for alveolar and embryonic rhabdomyoblastic differentiation [18], compared with Pax3:Foxo1a,p53 tumors. These results suggested that Rb1 inactivation in the context of Pax3:Foxo1a activation and p53 inactivation may mix the molecular phenotype of tumors for a state neither consistent purely with aRMS or with eRMS.

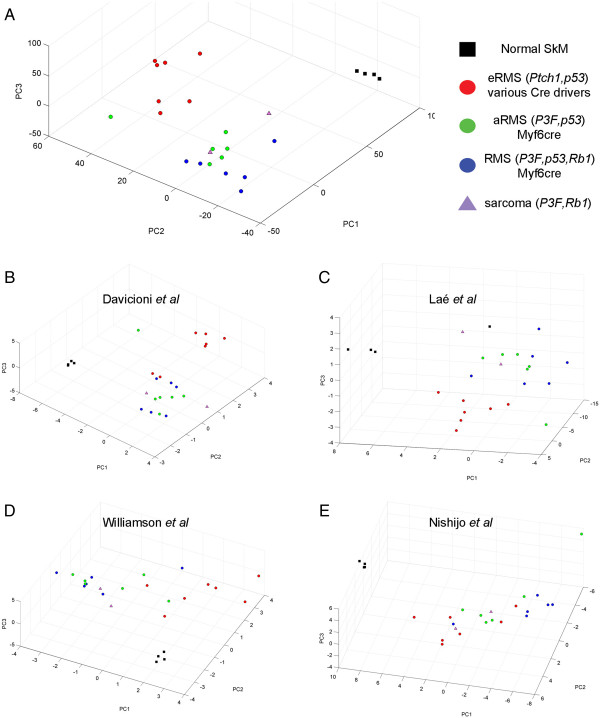

Rb1 loss in Pax3:Foxo1a,p53 tumors results in an overall molecular phenotype more similar to aRMS than eRMS

Because the addition of Rb1 loss sometimes masked histological identity and also shifted selected marker expression of aRMS versus eRMS for Pax3:Foxo1a,p53 mice, we sought to clarify overall biology of Pax3:Foxo1a,p53,Rb1 mice by examining global gene expression profiles. To achieve this goal, we applied PCA to all 25 tumor samples [GEO:GSE22520] [1] with 12,370 selected probes based on their overall expression level and variation, as well as published four gene sets that differentiated aRMS and eRMS in humans [11,14,19,20] (see Methods). All PCA results derived from four different gene sets showed comparable separation of three groups: eRMS (red), aRMS (green) and normal skeletal muscle (black) (Figure 6A to E). In addition, we observed that Pax3:Foxo1a,p53 tumors (green), Pax3:Foxo1a,p53,Rb1 tumors (blue) and Pax3:Foxo1a,Rb1 tumors (purple) were classified into the same relative RMS types (Figure 6A to E). The genes and principal component coefficients (that is, loadings) for genes are given in Additional file 1. As a validation measure, the recombination of Rb1 loci from tumors was confirmed to be complete in Pax3:Foxo1a,p53,Rb1 tumors (Additional file 2). Furthermore, we performed a Student t test between Pax3:Foxo1a,p53 tumor (aRMS) and Pax3:Foxo1a,p53,Rb1 tumor (other RMS) data with 138 genes differentially expressed between these two groups (fold-change >2, and P < 0.05). Classical genes recognized for Rb1-deficient tumors [21] were identified as increased in Rb1 deleted aRMS tumors (Mcm7, H1fx, Cdc25c, Tyms, Brca2, Top2a, Kif2c, Tk1, Plk1, Birc5, Cdc20, Msh6, Cbx2, Chaf1b, Ccnb1, H2afz, Mcm2) by 1.5-fold to 2.1-fold. In addition, intactness of the Rb1 loci was associated with expression of certain myogenesis-related genes (Myh7, Myl4, Actc1, Tnni1, Myl3, Mef2c), whereas Rb1 loss was associated with genes that did not fit any apparent common function (Biklk, Itgb4, Slc14a1, Reln, Ear11, Vgll2, Pvalb) (Additional file 3).

Figure 6.

Human aRMS versus eRMS gene set differences are conserved in murine models when Rb1 is inactivated. (A) Principal component analysis (PCA) of mouse tumors using 12,370 genes that significantly discriminate among previously described murine eRMS [1] (red), Pax3:Foxo1a,p53 tumors (green) or Pax3:Foxo1a,p53,Rb1 tumors (blue), and normal skeletal muscle (black). Samples are colored according to their genotypes as indicated. Average log2 intensity >6 and standard deviation >0.1 over 25 samples. Normal skeletal muscle (SkM) is shown as a control. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. (B) PCA for differentially expressed genes between PAX-FOXO1A and fusion-negative RMS cell lines by Davicioni and colleagues [14]. (C) PCA for differentially expressed genes in fusion-positive aRMSaRMS versus fusion-negative eRMS by Laé and colleagues [19]. (D) PCA for differentially expressed F1/F2 metagenes by Williamson and colleagues [20]. (E) PCA for genes conserved in mouse and human Pax3:Foxo1a-positive aRMS by Nishijo and colleagues [11].

We next examined the functional and therapeutic significance of Rb1 loss. pRb associates with a wide range of transcription factors to control cell cycle progression, cellular senescence, apoptosis, and differentiation. The best characterized role for pRb is in the control of E2F1 activity. pRb exerts this function by interfering with the ability of E2F1 to communicate with the basal transcription apparatus and/or recruiting chromatin-modifying enzymes to block the activation of E2F responsive genes [22]. In this context pRb has been shown to target histone deacetylase (HDAC) [23,24]. On the other hand, pRb is regulated by cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK)-4 or CDK6 in complex with cyclin D1[21,25,26] – rendering Rb1 null tumors insensitive to CDK4/CDK6 inhibitors. We therefore compared the sensitivity of primary tumor cell cultures from Pax3:Foxo1a,p53 tumors with Pax3:Foxo1a,p53,Rb1 tumors for the anti-cancer agents panobinostat (LBH58; a pan-HDAC inhibitor), PD0332991 (a selective cyclin D kinase 4/6 inhibitor), SAHA (vorinostat; a HDAC inhibitor) and SNS-032 (BMS-387032; a CDK2, CDK7 and CDK9 inhibitor). For this experiment, we utilized three biologically independent primary cell cultures for each genotype. We found no statistically significant difference in sensitivity to panobinostat at single concentrations (P = 0.38 at 10 nM, P = 0.34 at 20 nM and P = 0.28 at 40 nM; P values were based on analysis of variance tests with Bonferroni multiple testing corrections) (Figure 2A), but small and statistically significant trend differences were seen for panobinostat and PD0332991. No difference in sensitivity was seen for SAHA or SNS-032. These results suggested that Pax3:Foxo1a,p53 tumors are functionally the same regardless of the deletion status of Rb1.

Given that pRb status has been previously shown to determine sensitivity to Cdk4/6 inhibitors in other forms of cancer [27], the insensitivity to PD0332991 for Pax3:Foxo1a,p53,Rb1 tumors relative to Pax3:Foxo1a,p53 tumors was unexpected. We thus hypothesized that aRMS with intact Rb1 loci may nonetheless functionally inactivate pRb through epigenetic silencing or pRb hyperphosphorylation. To investigate these possibilities, we first examined the level of pRb and phospho-pRb by western blotting. We compared expression of Pax3:Foxo1a expressing primary tumor cell cultures with or without Rb1 loss (n = 3 biological replicates each) to proliferating or differentiating C2C12 myoblasts as a control for the aRMS cell of origin. While present, pRb and phospho-pRb expression was dramatically lower in aRMS primary cell cultures for which Rb1 alleles were wildtype than in C2C12 myoblasts (Figure 2B). As expected, pRb expression was absent in aRMS primary cell cultures for which Rb1 was homozygously, conditionally deleted (Figure 2B). Expression of the Rb-related family member, p107, was not significantly increased in aRMS primary cell cultures for which Rb1 was homozygously, conditionally deleted versus aRMS primary cell cultures for which Rb1 alleles were wildtype (Figure 2B). Taken together, these data suggest that pRb expression is downregulated at the transcriptional or post-transcriptional level, thereby accounting for the lack of difference of sensitivity to the CDK4/CDK6 inhibitor, PD0332991, whether Pax3:Foxo1a-expressing tumors had wildtype or conditionally deleted Rb1 alleles.

To determine whether decreased pRb levels in aRMS Rb1 wildtype tumors reflected transcriptional downregulation, we performed qRT-PCR of Rb1. Relative to proliferating or differentiated C2C12 myoblasts, mRNA levels were significantly diminished in aRMS Rb1 wildtype primary tumor cell cultures (Figure 2C). Given that Rb1 was downregulated at the transcriptional level, to determine whether Pax3:Foxo1a acted directly or indirectly to reduce pRb expression we generated stable clones for knockdown of Pax3:Foxo1a using shRNA against eYFP (because the mouse model has eYFP expressed on the same mRNA as Pax3:Foxo1a by means of a Pax3:Foxo1a-ires-eYFP conditional knock-in configuration at the Pax3 locus, eYFP knockdown leads to Pax3:Foxo1a knockdown). Despite reduction of Pax3:Foxo1a in two independent aRMS clones cultures relative to two independent control shRNA aRMS clone cultures, pRb expression did not change (Figure 2D). Furthermore, sensitivity to the CDK4/CDK6 inhibitor, PD0332991, was not improved by Pax3:Foxo1a knockdown (Figure 2E). These data suggest an alternation in G1/S checkpoint control in mouse aRMS that is independent of Pax3:Foxo1a.

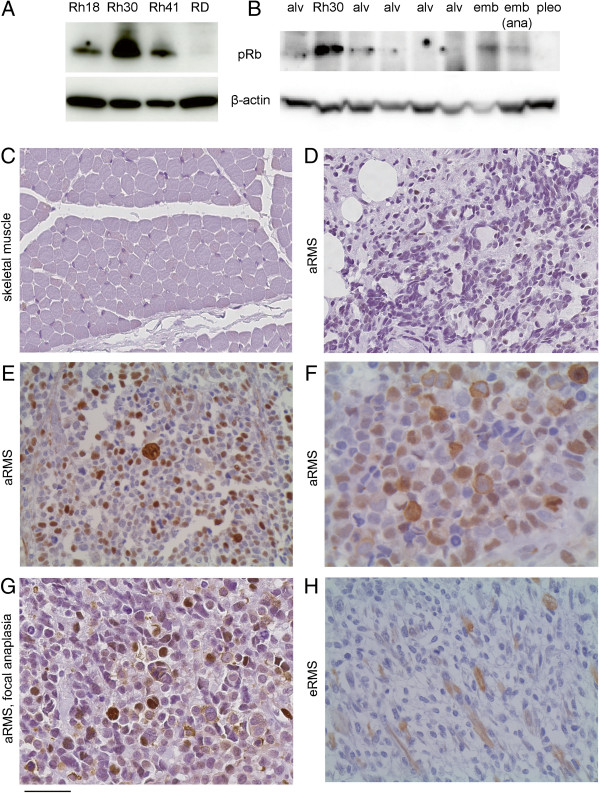

To cross-correlate mouse aRMS findings to human pediatric aRMS, we examined pRb expression by western blotting in aRMS cell lines (Rh30, Rh41) in comparison with eRMS cell lines (Rh18, RD) (Figure 7A). Both aRMS cell lines expressed pRb, strongest in Rh30. To determine whether pRb expression in Rh30 was representative of clinical sample expression, we performed western blotting of available human aRMS, eRMS and pleomorphic RMS samples concurrent with Rh30 (Figure 7B; Additional file 4). Rh30 expression was an outlier, given that clinical aRMS (as well as eRMS and pleomorphic RMS) samples expressed little pRb.

Figure 7.

pRb expression in human RMS. (A) Western blotting of human aRMS (Rh30,Rh41) and eRMS (Rh18, RD) cell lines. (B) Clinical RMS samples. alv, aRMS; emb, eRMS; ana, with anaplasia; pleo, pleomorphic RMS. (C) to (H) Immunohistochemistry of a human rhabdomyosarcoma tissue microarray using an anti-phospho pRb antibody that detects phosphorylation at Ser807/811. Staining was nuclear, cytoplasmic or both in any given cell, but the percentage of cells stained variably between 0 and 80%.

To determine whether low pRb expression in RMS is due to homogeneous low pRb expression across all cells or selective pRb expression in only a subset of RMS cells, we performed immunohistochemistry of a tissue microarray provided by the Children’s Oncology Group Biorepository. This tissue microarray was evaluated using an anti-phospho-pRb antibody that detects phosphorylation at Ser807/811. Ser807 is a site phosphorylated by CDK4 that in some contexts appears critical to phospho-pRb growth suppressor function inactivation and nuclear export [28]. Results are presented in Additional file 5. Skeletal muscle consistently had no staining. For tumor cores with a typical aRMS histology, 3/25 (12%) had no expression, 12/25 (48%) had expression in 2 to 30% of cells, and 10/25 (40%) had weak to strong expression in 40 to 80% of cells. Nuclear expression was evident in 19/25 (76%) of cores, cytoplasmic expression in 11/25 (44%) of cores, and simultaneous nuclear and cytoplasmic expression was present in the same cell for 9/25 (36%) of cores. Altogether, 14/25 (56%) of aRMS cores displayed evidence of cytoplasmic phospho-pRb localization, suggesting that nuclear export may be a major mechanism of pRb inactivation in aRMS. In three other core samples of aRMS with anaplasia, 1 to 50% of cells strongly expressed phospho-pRb with nuclear localization (for so few samples we hesitate to infer any generalizations). Finally, for specialized rhabdomyoblast cells of aRMS that paradoxically express markers of differentiation and display common multinucleation but also express markers of proliferation (ki67 positivity) [29], phospho-pRb localization was nuclear, cytoplasmic or both (as was also seen for the nonrhabdomyoblast tumor cells). Expression of pRb was thus heterogeneous in aRMS, accounting for overall low total pRb levels – with high pRb expression levels in the Rh30 cell line possibly having been a selection effect.

Discussion

In this study we have demonstrated that Rb1 loss is a modifier of aRMS progression, but not a necessary and sufficient mutational event for rhabdomyosarcomagenesis, nor even a strong cooperative initiating mutation. The modifier effect of Rb1 loss at the histological level was to increase anaplasia and pleomorphism, whereas at the molecular level, even though Pax3:Foxo1a expression itself was not altered, the traditional gene expression biomarkers of alveolar versus embryonal RMS subtypes were both increased. Individual gene expression biomarkers of eRMS versus aRMS may thus be unreliable in the situation of Rb1 loss. Nevertheless, overall gene expression of Rb1 null aRMS more closely approximated aRMS than eRMS. Intrinsically abnormal Rb1 levels and pRb function in all Pax3:Foxo1-expressing RMS was evidenced by the insensitivity to a canonical Cdk4/6 inhibitor, regardless of whether the Rb1 locus was intact or null. The mechanism of Rb1 transcriptional dampening remains an open question for future studies. Although our testing of the HDAC1/2/3/6 inhibitor vorinostat had relatively little single agent effect on cell viability, it is intriguing to speculate that other pharmacological modifiers of DNA methylation, histone acetylation or histone methylation might restore Rb1 levels and pRb function and thereby have utility in a combination therapy approach.

The role of Rb1 in RMS initiation is controversial [6,7]. While RMS is rare as a primary cancer in patients with germline Rb1 haploinsufficiency, RMS is the most common soft tissue sarcoma in a radiation field [30] for these patients. However, these cases are generally RMS not otherwise specified rather than aRMS [31]. In mice, the T antigen (which inactivates all three Rb-family members pRb, p107 and p130) expressed as a transgene leads to the development of cardiac RMS [32]. However, in our recent study of strict conditional Rb1 loss in the Myf6-expressing fetal/postnatal maturing myoblast or Pax7-expressing postnatal muscle stem cell (satellite cell) lineages, no tumors developed [33]; instead, satellite cell and myoblast pools expanded but were largely incapable of fusing to form mature myofibers. Thus, from these past and the current studies it would seem that Rb1 loss alone does not initiate rhabdomyosarcomagenesis.

A role for Rb1 loss in progression of eRMS and other soft tissue sarcomas has been clearer than for aRMS. In a related report of non-aRMS soft tissue sarcomas, Rb1 loss accelerated progression of p53-initiated tumors and led to undifferentiated phenotypes, but, as expected, did not induce tumor initiation in a conditional model using a Prx-cre driver (specific to the mesenchymal tissue of the limb bud) [34]. For RMS, Rb1 had been suggested to play a more important role in embryonal RMS (eRMS) than aRMS: Rb1 genetic abnormalities (allelic imbalance, deletion) are more common in eRMS than in aRMS [6], and one study showed no dramatic loss of Rb1 in 13 aRMS primary tumor samples [7]. At the protein level, pRb positivity by immunohistochemistry in aRMS is lower than for eRMS (65% vs. 85%, respectively) [35]. Our complementary re-analysis of confirmed fusion-positive human aRMS revealed that a fully pRb off signature can be frequent (25 of 62 Pax3:Foxo1a-positive cases) but almost never does a fully pRb off signature happen without a co-existing p53 off signature (Jinu Abraham and colleagues, in preparation. Subtle variations in Rb1 gene and protein expression may thus depend on the mutational profile of aRMS (for example, Pax3:Foxo1a and/or p53 status) if not other factors. In the small sets of human samples we studied for total pRb expression by western and phospho-pRb expression by immunohistochemistry, we found that overall expression was generally low for aRMS tumors (similar to the mouse), and that only subsets of cells had expression within a tumor mass (and among this subset, cytoplasmic localization for presumed pRb inactivation was not uncommon).

An unexplained phenomenon is that human aRMS are known to have a much higher mitotic rate than eRMS [35], similar to the observation in mice [1]. A related observation in our current study was the fairly similar insensitivity of Rb1 null and Rb1 wildtype aRMS to a Cdk4/6 inhibitor, PD0332991, which may be attributed to the relatively low Rb1 transcript levels we observed in tumors with wildtype Rb1 alleles. We speculate that human aRMS tumors may achieve effective pRb inactivation (and related PD0332991 resistance) through the same or a number of other mechanisms including pRb nuclear exclusion, inhibition of pRb phosphatases, Rb1 mutation, Survivin overexpression [27,36,37], Cdk4 amplification [38], ΔNp73 or p57 expression [39], Cdkn2a (p16ink4a) loss, E2F gene mutations, overexpression or amplification of cyclin D1 (facilitating pRb phosphorylation), expression of viral proteins (for example, HPV-E7), or p27 or p21 loss [21]. The latter (p21 and p27) are observed to have lower expression in aRMS than eRMS, an effect that can be reversed by the putative HDAC inhibitor butyrate [40]. Further downstream in the G1/S checkpoint, p27 degradation is increased in a Pax3:Foxo1a-dependent manner, attributed to the Pax3:Foxo1a target gene product, Skp2 [11,41]. Interestingly, in other tumors p27 loss desensitizes Rb1 null tumor cells to Arf-mediated apoptosis. Thus, p27 and pRb loss of function may be synergistically tumorigenic in aRMS – which combined with the other factors accelerating early G1/S checkpoint entry may overall accelerate progression from the G1 phase to the S phase.

An interesting aspect of our studies is that conditional deletion of Rb1, resulting in loss of the very low baseline expression of Rb1 and pRb, could be associated with reduced myogenic marker expression for some tumors examined. pRb is known to have roles in both cell cycle control and myogenic differentiation of normal myoblasts, but when pRb is lost then p107 is able to play a compensatory role in myogenic differentiation [42]. In our studies of aRMS, p107 did not compensate for pRb loss. Thus, the variably present Rb1 null aRMS de-differentiation phenotype suggests that low baseline pRb expression is in fact important biologically – and an important determinant of aRMS histomorphological identity. Diagnostically, this result could be very significant in that it leaves the possibility that some clinical cases of undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas may in fact express Pax3:Foxo1A, but in the context of pRb loss would not be tested for Pax3:FoxO1A given their histological appearance.

Conclusions

The pRb and Pax3:Foxo1a status may warrant investigation in pleomorphic soft tissue sarcomas currently thought to be distinct from aRMS. A careful distinction, too, between low baseline pRb expression and near-complete pRb loss may require additional clinical biomarkers such as p16ink4a in a prospective manner.

Abbreviations

aRMS: Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma; CDK: Cyclin-dependent kinase; DMEM: Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s media; eRMS: Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma; HDAC: Histone deacetylase; PCA: Principal component analysis; RMS: Rhabdomyosarcoma; shRNA: Short hairpin RNA.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

KN and CK conceived and designed these studies. Experimental methodology was developed by KN, KK and CK. Experimental procedures were carried out by KN, CK, MNS, AB, SD, SLP, PSM and ETH. ET, H-IHC, KK, ETH, KN, JA OR, MS, NB, YC, AM, BPR and CK participated in analysis and interpretation of data. CL, LAZ and JEM performed the statistical analysis. ET, KK and CK wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Presenting gene sets used for PCA and genes accounting for each principal component in Figure 6.

Presenting complete recombination of floxed alleles. Successful recombination of all floxed alleles of Pax3:Foxo1a, p53 or Rb1 was confirmed by genomic polymerase chain reaction of tumors in Myf6cre,Pax3:Foxo1a,p53,Rb1 mice.

Presenting differential gene expression for Myf6cre,Pax3:Foxo1a,p53 tumors with and without Rb1 inactivation.

Presenting samples used for western blotting in Figure 7B.

Presenting scoring for phospho-pRb of the tissue microarray (slide scan sent to the Children’s Oncology Group Biorepository and available on request).

Contributor Information

Ken Kikuchi, Email: kenkikuchi88@gmail.com.

Eri Taniguchi, Email: eritanijp@hotmail.com.

Hung-I Harry Chen, Email: ChenHH@uthscsa.edu.

Matthew N Svalina, Email: svalina@ohsu.edu.

Jinu Abraham, Email: abraham@ohsu.edu.

Elaine T Huang, Email: huange@ohsu.edu.

Koichi Nishijo, Email: koichi.nishijo@bayerhealthcare.com.

Sean Davis, Email: sdavis2@mail.nih.gov.

Christopher Louden, Email: louden@uthscsa.edu.

Lee Ann Zarzabal, Email: lz1033@gmail.com.

Olivia Recht, Email: orecht@smith.edu.

Ayeza Bajwa, Email: ayeza.bajwa@yahoo.com.

Noah Berlow, Email: noah.berlow@ttu.edu.

Mònica Suelves, Email: MSuelves@imppc.org.

Sherrie L Perkins, Email: sherrie.perkins@hsc.utah.edu.

Paul S Meltzer, Email: pmeltzer@mail.nih.gov.

Atiya Mansoor, Email: mansoora@ohsu.edu.

Joel E Michalek, Email: michalekj@uthscsa.edu.

Yidong Chen, Email: ChenY8@uthscsa.edu.

Brian P Rubin, Email: rubinb2@ccf.org.

Charles Keller, Email: keller@ohsu.edu.

Acknowledgements

Primary funding sources were NIH1R01CA133229 and a gift from the Nylund estate. KN and JA were supported by a training award from the Scott Carter Foundation. The Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank is developed under the auspices of the NICHD and maintained by The University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA. De-identified human tumor samples were provided by the Nationwide Children’s Hospital Biopathology Center or the Children’s Oncology Group Biorepository. The authors thank Amy Paul for assistance with studies, Dennis Duran for slide scanning and Hajime Hosoi for reagents.

References

- Rubin BP, Nishijo K, Chen HI, Yi X, Schuetze DP, Pal R, Prajapati SI, Abraham J, Arenkiel BR, Chen QR, Davis S, McCleish AT, Capecchi MR, Michalek JE, Zarzabal LA, Khan J, Yu Z, Parham DM, Barr FG, Meltzer PS, Chen Y, Keller C. Evidence for an unanticipated relationship between undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma and embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:177–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller C, Arenkiel BR, Coffin CM, El-Bardeesy N, DePinho RA, Capecchi MR. Alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas in conditional Pax3:Fkhr mice: cooperativity of Ink4a/ARF and Trp53 loss of function. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2614–2626. doi: 10.1101/gad.1244004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatley ME, Tang W, Garcia MR, Finkelstein D, Millay DP, Liu N, Graff J, Galindo RL, Olson EN. A mouse model of rhabdomyosarcoma originating from the adipocyte lineage. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:536–546. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt CA, Crist WM. Common musculoskeletal tumors of childhood and adolescence. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:342–352. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907293410507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettmer S, Liu J, Miller CM, Lindsay MC, Sparks CA, Guertin DA, Bronson RT, Langenau DM, Wagers AJ. Sarcomas induced in discrete subsets of prospectively isolated skeletal muscle cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:20002–20007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111733108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohashi K, Oda Y, Yamamoto H, Tamiya S, Takahira T, Takahashi Y, Tajiri T, Taguchi T, Suita S, Tsuneyoshi M. Alterations of RB1 gene in embryonal and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma: special reference to utility of pRB immunoreactivity in differential diagnosis of rhabdomyosarcoma subtype. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134:1097–1103. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0385-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Chiara A, T’Ang A, Triche TJ. Expression of the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene in childhood rhabdomyosarcomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:152–157. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CB, Engleka KA, Wenning J, Min Lu M, Epstein JA. Identification of a hypaxial somite enhancer element regulating Pax3 expression in migrating myoblasts and characterization of hypaxial muscle Cre transgenic mice. Genesis. 2005;41:202–209. doi: 10.1002/gene.20116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino S, Vooijs M, Van Der Gulden H, Jonkers J, Berns A. Induction of medulloblastomas in p53-null mutant mice by somatic inactivation of Rb in the external granular layer cells of the cerebellum. Genes Dev. 2000;14:994–1004. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonkers J, Meuwissen R, Can der Gulden H, Peterse H, Van der Valk M, Berns A. Synergistic tumor suppressor activity of BRCA2 and p53 in a conditional mouse model for breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2001;29:418–425. doi: 10.1038/ng747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishijo K, Chen QR, Zhang L, McCleish AT, Rodriguez A, Cho MJ, Prajapati SI, Gelfond JA, Chisholm GB, Michalek JE, Aronow BJ, Barr FG, Randall RL, Ladanyi M, Qualman SJ, Rubin BP, LeGallo RD, Wang C, Khan J, Keller C. Credentialing a preclinical mouse model of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2902–2911. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishijo K, Hosoyama T, Bjornson CR, Schaffer BS, Prajapati SI, Bahadur AN, Hansen MS, Blandford MC, McCleish AT, Rubin BP, Epstein JA, Rando TA, Capecchi MR, Keller C. Biomarker system for studying muscle, stem cells, and cancer in vivo. FASEB J. 2009;23:2681–2690. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-128116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoyama T, Nishijo K, Garcia MM, Schaffer BS, Ohshima-Hosoyama S, Prajapati SI, Davis MD, Grant WF, Scheithauer BW, Marks DL, Rubin BP, Keller C. A postnatal Pax7 progenitor gives rise to pituitary adenomas. Genes Cancer. 2010;1:388–402. doi: 10.1177/1947601910370979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davicioni E, Finckenstein FG, Shahbazian V, Buckley JD, Triche TJ, Anderson MJ. Identification of a PAX-FKHR gene expression signature that defines molecular classes and determines the prognosis of alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6936–6946. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davicioni E, Anderson MJ, Finckenstein FG, Lynch JC, Qualman SJ, Shimada H, Schofield DE, Buckley JD, Meyer WH, Sorensen PH, Triche TJ. Molecular classification of rhabdomyosarcoma–genotypic and phenotypic determinants of diagnosis: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:550–564. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grass B, Wachtel M, Behnke S, Leuschner I, Niggli FK, Schafer BW. Immunohistochemical detection of EGFR, fibrillin-2, P-cadherin and AP2β as biomarkers for rhabdomyosarcoma diagnostics. Histopathology. 2009;54:873–879. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachtel M, Runge T, Leuschner I, Stegmaier S, Koscielniak E, Treuner J, Odermatt B, Behnke S, Niggli FK, Schafer BW. Subtype and prognostic classification of rhabdomyosarcoma by immunohistochemistry. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:816–822. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.4934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Perlman E, Harris CA, Raffeld M, Tsokos M. Myogenin is a specific marker for rhabdomyosarcoma: an immunohistochemical study in paraffin-embedded tissues. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:988–993. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laé M, Ahn EH, Mercado GE, Chuai S, Edgar M, Pawel BR, Olshen A, Barr FG, Ladanyi M. Global gene expression profiling of PAX-FKHR fusion-positive alveolar and PAX-FKHR fusion-negative embryonal rhabdomyosarcomas. J Pathol. 2007;212:143–151. doi: 10.1002/path.2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson D, Missiaglia E, De Reynies A, Pierron G, Thuille B, Palenzuela G, Thway K, Orbach D, Lae M, Freneaux P, Pritchard-Jones K, Oberlin O, Shipley J, Delattre O. Fusion gene-negative alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma is clinically and molecularly indistinguishable from embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2151–2158. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen ES, Knudsen KE. Tailoring to RB: tumour suppressor status and therapeutic response. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:714–724. doi: 10.1038/nrc2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehm A, Kouzarides T. Retinoblastoma protein meets chromatin. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:142–145. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01368-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehm A, Miska EA, McCance DJ, Reid JL, Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. Retinoblastoma protein recruits histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Nature. 1998;391:597–601. doi: 10.1038/35404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnaghi-Jaulin L, Groisman R, Naguibneva I, Robin P, Lorain S, Le Villain JP, Troalen F, Trouche D, Harel-Bellan A. Retinoblastoma protein represses transcription by recruiting a histone deacetylase. Nature. 1998;391:601–605. doi: 10.1038/35410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DO. Principles of CDK regulation. Nature. 1995;374:131–134. doi: 10.1038/374131a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg RA. The retinoblastoma protein and cell cycle control. Cell. 1995;81:323–330. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldas H, Holloway MP, Hall BM, Qualman SJ, Altura RA. Survivin-directed RNA interference cocktail is a potent suppressor of tumour growth in vivo. J Med Genet. 2006;43:119–128. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.034686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao W, Datta J, Lin HM, Dundr M, Rane SG. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein via Cdk phosphorylation-dependent nuclear export. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:38098–38108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605271200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Kikuchi K, Radka M, Abraham J, Rubin BP, Keller C. IL-4 receptor blockade abrogates satellite cell – rhabdomyosarcoma fusion and prevents tumor establishment. Stem Cells. 2013. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Marees T, Moll AC, Imhof SM, De Boer MR, Ringens PJ, Van Leeuwen FE. Risk of second malignancies in survivors of retinoblastoma: more than 40 years of follow-up. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1771–1779. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinerman RA, Tucker MA, Abramson DH, Seddon JM, Tarone RE, Fraumeni JF Jr. Risk of soft tissue sarcomas by individual subtype in survivors of hereditary retinoblastoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:24–31. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobbert C, Mollmann C, Schafers M, Hermann S, Baba HA, Hoffmeier A, Breithardt G, Scheld HH, Weissen-Plenz G, Sindermann JR. Transgenic model of cardiac Rhabdomyosarcoma formation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;136:1178–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoyama T, Nishijo K, Prajapati SI, Li G, Keller C. Rb1 gene inactivation expands satellite cell and postnatal myoblast pools. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:19556–19564. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.229542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin PP, Pandey MK, Jin F, Raymond AK, Akiyama H, Lozano G. Targeted mutation of p53 and Rb in mesenchymal cells of the limb bud produces sarcomas in mice. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(10):1789–1795. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Oda Y, Kawaguchi K, Tamiya S, Yamamoto H, Suita S, Tsuneyoshi M. Altered expression and molecular abnormalities of cell-cycle-regulatory proteins in rhabdomyosarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:660–669. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A, Hayashida M, Ito T, Kawano H, Nakano T, Miura M, Akahane K, Shiraki K. Survivin initiates cell cycle entry by the competitive interaction with Cdk4/p16(INK4a) and Cdk2/cyclin E complex activation. Oncogene. 2000;19:3225–3234. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A, Ito T, Kawano H, Hayashida M, Hayasaki Y, Tsutomi Y, Akahane K, Nakano T, Miura M, Shiraki K. Survivin initiates procaspase 3/p21 complex formation as a result of interaction with Cdk4 to resist Fas-mediated cell death. Oncogene. 2000;19:1346–1353. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cen L, Carlson BL, Schroeder MA, Ostrem JL, Kitange GJ, Mladek AC, Fink SR, Decker PA, Wu W, Kim JS, Waldman T, Jenkins RB, Sarkaria JN. p16-Cdk4-Rb axis controls sensitivity to a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor PD0332991 in glioblastoma xenograft cells. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14:870–881. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cam H, Griesmann H, Beitzinger M, Hofmann L, Beinoraviciute-Kellner R, Sauer M, Huttinger-Kirchhof N, Oswald C, Friedl P, Gattenlohner S, Burek C, Rosenwald A, Stiewe T. p53 family members in myogenic differentiation and rhabdomyosarcoma development. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:281–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti A, Borriello A, Monno F, Criscuolo M, Rosolen A, Esposito G, Dello Iacovo R, Della Ragione F, Iolascon A. Cell division cycle control in embryonal and alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:2290–2299. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(02)00454-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Wang C. PAX3-FKHR transformation increases 26 S proteasome-dependent degradation of p27Kip1, a potential role for elevated Skp2 expression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205424200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider JW, Gu W, Zhu L, Mahdavi V, Nadal-Ginard B. Reversal of terminal differentiation mediated by p107 in Rb-/- muscle cells. Science. 1994;264:1467–1471. doi: 10.1126/science.8197461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Presenting gene sets used for PCA and genes accounting for each principal component in Figure 6.

Presenting complete recombination of floxed alleles. Successful recombination of all floxed alleles of Pax3:Foxo1a, p53 or Rb1 was confirmed by genomic polymerase chain reaction of tumors in Myf6cre,Pax3:Foxo1a,p53,Rb1 mice.

Presenting differential gene expression for Myf6cre,Pax3:Foxo1a,p53 tumors with and without Rb1 inactivation.

Presenting samples used for western blotting in Figure 7B.

Presenting scoring for phospho-pRb of the tissue microarray (slide scan sent to the Children’s Oncology Group Biorepository and available on request).