Abstract

Bifidobacteria are one of the predominant bacterial groups of the human intestinal microbiota and have important functional properties making them interesting for the food and dairy industries. Numerous in vitro and preclinical studies have shown beneficial effects of particular bifidobacterial strains or strain combinations on various health parameters of their hosts. This indicates the potential of bifidobacteria in alternative or supplementary therapeutic approaches in a number of diseased states. Based on these observations, bifidobacteria have attracted considerable interest by the food, dairy, and pharmaceutical industries and they are widely used as so-called probiotics. As a consequence of the rapidly increasing number of available bifidobacterial genome sequences and their analysis, there has been substantial progress in the identification of bifidobacterial structures involved in colonisation of and interaction with the host. With the present review, we aim to provide an update on the current knowledge on the mechanisms by which bifidobacteria colonise their hosts and exert health promoting effects.

1. Introduction

1.1. Host Colonisation by Bifidobacteria

On a cellular basis, humans can be regarded as superorganisms. As a rough approximation, these super-organisms consist of 90% microbial cells with the vast majority of the microbial diversity being located in the human gastrointestinal tract (GIT) [1]. The development and composition of a normal GIT microbiota is crucial for establishing and maintaining human health and well-being [2–4]. It is generally accepted that, before birth, the intrauterine environment and thus the GIT of the unborn foetus are sterile [4]. During delivery, newborns acquire microorganisms from their mothers faecal, vaginal, and skin microbiota. Interestingly, considerable numbers of bifidobacteria and other components of the infant intestinal microbiota were also isolated from human breast milk [5, 6]. Some of the strains recovered in the mother's milk were identical to those detected in the faecal samples of the infant [7] suggesting that human milk might contribute to the establishment and development of the intestinal microbiota of children.

The succession of colonisation follows more or less a classical pattern with facultative anaerobes such as Escherichia coli or Enterococcus sp. dominating for the first hours or days. Once these organisms have consumed the residual oxygen in the GIT, strictly anaerobic bacteria including Bifidobacterium sp., Clostridium sp., and Bacteroides sp. rapidly become predominant [4]. In naturally delivered, breast-fed children up to 95% of all bacteria are bifidobacteria [8–10] making them by far the predominant bacterial component of the faecal microbiota in this group. The bifidobacteria most frequently isolated from healthy breast-fed infants belong to the species B. longum, B. bifidum, and B. breve [10, 11].

Following the period of exclusive breast-feeding, the composition of the faecal microbiota rapidly changes due to the introduction of solid foods, constant exposure to food-derived and environmental microorganisms, and other factors such as hygiene, antibiotic treatment, and so forth [4, 12]. During the first three years of life, the faecal microbiota then gradually develops into the microbiota of adults [9]. The adult colonic and faecal microbiota is dominated by obligate anaerobes with Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes together representing more than 80% followed by Actinobacteria, which contribute up to 10% to the total bacterial flora. The vast majority (up to 100%) of Actinobacteria in faecal samples are representatives of the genus Bifidobacterium [12]. Members of this genus are nonmotile, non-spore-forming, strictly anaerobic, gram-positive bacteria characterised by genomes with a high G + C content, an unusual pathway for sugar fermentation termed bifidus shunt, and an unusual V- or Y-shaped morphology formed by most strains under specific culture conditions [13].

1.2. Effects of Bifidobacteria on Host Health

In healthy individuals, the composition of the intestinal microbiota is relatively stable throughout adulthood with minor day-to-day variations [36, 37]. However, a number of factors have profound impact on the composition of the microbiota and more substantial and persistent changes in the microbiota, a state also termed dysbiosis, are associated with various diseases [2, 38]. A common feature of most diseases with changes in the (intestinal) microbiota is a reduction or change in the relative abundance of bifidobacteria along with an increase in other bacterial groups, such as Enterobacteriaceae or clostridia (Table 1). These alterations might be implicated in onset, perpetuation, and/or progression of disease [12]. However, in most cases, it is not clear whether the altered community profiles of the microbiota are a cause or consequence of the disease.

Table 1.

Factors and medical conditions associated with changes in the composition of the faecal microbiota.

| Factor/disease | Effect/observation | References |

|---|---|---|

| Caesarean section | Higher numbers of the Clostridium difficile group l Delayed/reduced colonisation with Bifidobacterium sp., Lactobacillus sp. and Bacteroides sp. |

[14–16] |

|

| ||

| Infant feeding | Formula-fed infants with lower levels and diversity in Bifidobacterium sp. | [11, 15, 17] |

|

| ||

| Ageing | Increase in Enterobacteriaceae and Bacteroidetes

Reduced levels of Bifidobacterium sp. |

[18, 19] |

|

| ||

| Antibiotic-associated diarrhea and chronic C. difficile infections | Reduced diversity Increase in Enterobacteriaceae and Firmicutes Reduced levels of Bifidobacterium sp. and Bacteroidetes |

[18, 20–22] |

|

| ||

| Irritable bowel syndrome | Increase in Firmicutes

Reduced levels of Bacteroidetes and Bifidobacterium sp. |

[23–25] |

|

| ||

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Reduced diversity Lower levels of Faecalibacterium sp. Increase in Enterobacteriaceae and Bifidobacterium sp. Reduced levels of Bifidobacterium sp. in pediatric IBD |

[26–29] |

|

| ||

| Atopic disease/Allergy | Increase in Clostridium sp.

Reduced levels of Bifidobacterium sp. |

[30–32] |

|

| ||

| Autism | Increase in Clostridium sp.

Reduced levels of Bifidobacterium sp. |

[33–35] |

Besides the implication in various diseases, the intestinal microbiota in general and bifidobacteria in particular are important to establish and maintain health of the host. Studies in germ-free animals nicely illustrate that the presence of a normal microbiota is required for proper development and function of the immune and digestive systems (reviewed in [38, 39]). Their predominance during neonatal development suggests that bifidobacteria play a major role in this process [4].

Various beneficial effects have been claimed to be related to presence or administration of bifidobacteria including cholesterol reduction, improvement of lactose intolerance, alleviation of constipation, and immunomodulation [13, 40, 41]. Different strains of bifidobacteria were shown to have profound effects on dendritic cells, macrophage, and T cells of healthy humans and in animals models of allergy or intestinal inflammation [42–47]. One class of molecules that seems to be of particular relevance for the immunomodulatory properties of bifidobacteria is exopolysaccharides (EPS). Mutants of B. breve UCC2003 that lack EPS production induce higher numbers of neutrophils, macrophages, NK, T and B cells in mice compared to the wild type strain indicating that EPS production renders this strain less immunogenic by an unknown mechanism [48].

A promising target for bifidobacterial treatments are amelioration of chronic inflammatory disorders of the GIT [42, 49, 50]. Different strains of bifidobacteria were shown to dampen NF-κB activation and expression and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines by IECs or immune cells in response to challenge with LPS, TNF-α, or IL-1β [51–56]. Also, various strains of bifidobacteria or mixes of probiotics containing bifidobacteria were able to counteract intestinal inflammation in different models of chronic intestinal inflammation [49, 53, 55–60]. In murine models, different strains of bifidobacteria have been shown to be able to counteract chronic intestinal inflammation by reducing proinflammatory Th1 and inducing regulatory T-cell populations and lowering of colitogenic bacteria [42, 45, 46, 50, 60].

Experiments in mice indicate that some strains of bifidobacteria confer resistance against infections with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium [61], enteropathogenic E. coli [62, 63], or Yersinia enterocolitica [64]. Interestingly, B. breve UCC2003 is able to protect mice against infections with C. rodentium and this ability depends on EPS production [48, 65]. The protective effect of other bifidobacteria towards enteric infections and intestinal inflammation was shown to be mediated by the production of short chain fatty acids, that is, the end products of bifidobacterial sugar fermentation [50, 63]. It is thus likely that the contribution of EPS production by B. breve UCC2003 to protection against C. rodentium is related to the improved colonisation [48].

2. Colonisation Factors of Bifidobacteria

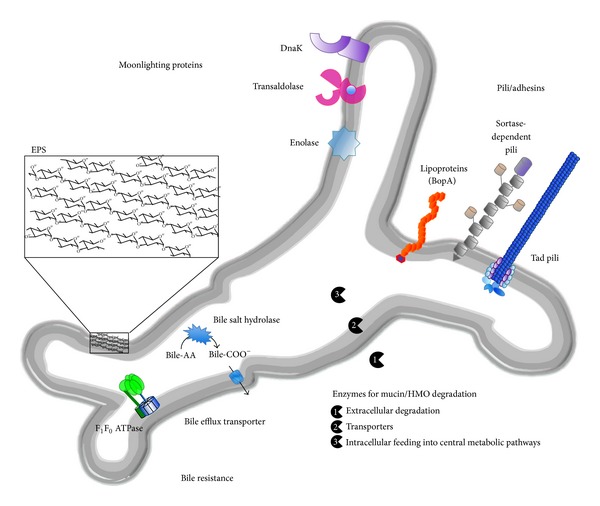

Due to the aforementioned effects of bifidobacteria, genomic approaches were pursued to understand the genetic and physiological traits involved in colonisation of and interaction with the host. The first genome sequence of a Bifidobacterium sp. strain was published in 2002 [66]. Since then, the genomes of over 200 strains of bifidobacteria belonging to 25 species and 5 subspecies have been sequenced (http://www.genomesonline.org/). Of these bifidobacterial genomes, 37 are complete and published and 42 are available as permanent drafts. Analysis of these genome sequences has provided insights into the very intimate association of bifidobacteria with their hosts and the adaptation to their gastrointestinal habitat and has led to the identification of a large number of genes with a potential role in these processes [67]. Some of these factors have been analysed in more detail (summarized in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Host colonisation factors of bifidobacteria identified by genome analysis and supported by experimental evidence obtained in in vitro experiments and/or murine model systems (bile-AA: conjugated bile acids; bile-COO−: deconjugated bile acids; Tad: tight adherence; EPS: exopolysaccharides; HMO: human milk oligosaccharides).

2.1. Resistance to Bile

Bile salts are detergents that are synthesized in the liver from cholesterol and secreted via the gall bladder into the GIT lumen [68]. They exert various physiological functions including lipid absorption and cholesterol homeostasis [69]. Since bile salts have considerable antimicrobial activity at physiological concentrations [70], resistance to bile is important for colonisation and persistence of gastrointestinal microorganisms and is thus one of the criteria for the selection of novel probiotic strains [71]. In a number of bifidobacteria, several genes and proteins conferring bile resistance including bile salt hydrolases and bile efflux transporters were identified and characterised in vitro [72–82]. Interestingly, the F1F0-type ATPase of B. animalis IPLA4549 was also shown to be involved in bile resistance [83]. The only example for in vivo functionality, however, is a recombinant strain of B. breve UCC2003 expressing the bile salt hydrolase BilE of Listeria monocytogenes [84]. Compared to the wild type, this strain showed improved bile resistance in vitro and prolonged gastrointestinal persistence and protection against L. monocytogenes infections in mice.

2.2. Carbohydrate Utilisation

The genome sequences of bifidobacteria of human origin display a remarkable enrichment in genes involved in breakdown, uptake, and utilisation of a wide variety of complex polysaccharides of dietary and host origin [13, 85–92]. Since most of the simple carbohydrates are absorbed by the host or metabolised by bacteria in the upper gastrointestinal tract, this can be regarded as a specific adaptation of bifidobacteria to their colonic habitat. The ability of bifidobacteria to ferment these complex carbohydrates is the rationale for the use of prebiotics, that is, nondigestible oligosaccharides, to boost bifidobacterial populations in the GIT [93].

The ability to utilise human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) is thought to provide a selective advantage to bifidobacteria over other microorganisms during initial colonisation of breast-fed newborns and to be, at least partially, responsible for the dominance of bifidobacteria in these children [85, 91]. The genomes of bifidobacteria particularly abundant in breast-fed infants, especially B. longum subsp. infantis, reflect their adaptation to the utilisation of HMOs [89, 90, 94] and some of the enzymes involved have been characterised [95–97].

Another nutritional adaptation of bifidobacteria to the intestinal niche is the ability to degrade and ferment host-derived mucins. Mucins are high molecular weight glycoproteins secreted by goblet cells as a protective coating for the intestinal epithelium [98]. Similar to the HMO-degradation pathways of B. longum subsp. infantis, B. bifidum strains were shown to grow on mucin as sole carbon source and harbour the respective genes for mucin degradation [85, 92].

2.3. Adhesins

Another property frequently associated with host colonisation of commensal and probiotic bacteria is adhesion to intestinal epithelial cells, mucus, or components of the extracellular matrix [99, 100]. Although definite proof for a role of adhesion of bifidobacteria to host-structures in colonisation is missing, these properties are thought to contribute to prolonged persistence and pathogen exclusion. Moreover, the presence of various receptors on the host surface for molecules of probiotic bacteria suggests direct interactions at least at some stage [101].

Strain-dependent adhesion of bifidobacteria to cultured intestinal epithelial cells has been shown in a number of studies [56, 102–115]. However, there are only very few reports investigating adhesion of bifidobacteria from a mechanistic point of view. For example, enolase was shown to mediate binding to human plasminogen by different bifidobacteria [104]. DnaK is another plasminogen-binding protein of B. animalis subsp. lactis Bl07 [105] and transaldolase is involved in mucus binding of four B. bifidum strains [116]. Using a proteomic approach, some of these proteins were shown to be induced in B. longum NCC2705 upon cocultivation with intestinal epithelial cells in vitro [117]. This indicates that bifidobacteria might be able to sense the presence of intestinal epithelial cells and react by expressing adhesive molecules that mediate interaction with these cells. Interestingly, the role of all these proteins as adhesins seems to be rather a moonlighting function, since they are cytoplasmic proteins with a primary role in bacterial metabolism. Similar moonlighting proteins have been shown to be involved in virulence of different pathogenic bacteria [118].

Bbif_0636, also termed BopA, is a lipoprotein with a cell wall anchor and was previously shown to be involved in adhesion of B. bifidum MIMBb75 to IECs [109]. A more detailed analysis performed by our group found the corresponding bopA gene to be specifically present in the genomes of B. bifidum strains. A purified BopA fusion protein with an N-terminal His6-tag inhibited adhesion of B. bifidum S17 to IECs. Moreover, expression of this His-tagged protein enhanced adhesion of B. bifidum S17 and B. longum E18 to IECs. The bopA gene is part of an operon encoding a putative oligopeptide ABC transporter and BopA contains an ABC transporter solute-binding domain [109, 112]. This indicates that its primary role might be uptake of nutrients and suggests a moonlighting function in adhesion. A recent study questioned the role of BopA as an adhesin [119]. The authors could show that neither BopA antiserum nor C-terminal His6-BopA fusion protein had an effect on adhesion of two B. bifidum strains to IECs. However, the His6-BopA fusion protein used in this study lacked both the signal sequence and the cell wall anchor motif. Thus, further experiments have to be performed to clarify the role of the position of the His6-tag, the contribution of the signal sequence and cell wall anchor, and BopA as an adhesin in general.

A recent bioinformatic analysis of the genome sequence of B. bifidum S17 for genetic traits potentially involved in interactions with host tissues revealed that the genome of B. bifidum S17 contains at least 10 genes that encode for proteins with domains that have been described or suspected to interact with host tissue components and may thus serve as potential surface-displayed adhesins [120]. Most of the genes for the putative adhesins of B. bifidum S17 are expressed in vitro, with higher expression during exponential growth phase [120]. Increased expression of the putative adhesins in exponential growth phase was associated with higher adhesion of B. bifidum S17 to Caco-2 cells [120].

2.4. Pili

All bifidobacterial genomes sequences analysed so far harbour clusters of genes encoding for Tad and/or sortase dependent pili [120–123]. For example, B. bifidum S17, B. breve S27, and B. longum E18 all harbour a complete gene locus for Tad pili. By contrast, B. longum E18 genome only contains an incomplete gene cluster for sortase-dependent pili suggesting absence of such structures and B. breve S27 encodes one gene cluster and B. bifidum S17 encodes three complete gene clusters for sortase-dependent pili. For a range of bifidobacteria, expression of the genes of these pili operons under in vitro conditions and in the mouse gastrointestinal tract could be demonstrated [120, 121, 123]. Several studies have also shown presence of pili on the surface of bifidobacteria under these conditions using immunogold labelling and transmission electron microscopy [122] or atomic force microscopy [121, 123]. For one strain of B. breve it was demonstrated that Tad pili are indeed important for host colonisation in a murine model [122].

2.5. EPS

Genes for EPS production were identified in most genome sequences of Bifidobacterium sp. strains [124]. The genetic organisation of EPS gene clusters is not well conserved in bifidobacteria and this is reflected by a high structural variability in the EPS of different bifidobacteria [124]. A recent study has indicated that production of EPS by B. breve UCC2003 is important for host colonisation [48]. Mutants of B. breve UCC2003 that lack EPS production are significantly less resistant to acidic pH and bile. Moreover, these mutants less efficiently colonize the gastrointestinal tract of mice compared to the wild type strain. Also, EPS-deficient mutants were considerably less immunogenic as the wild type in mice as reflected by lower numbers of immune cells in spleens and lower serum titres of specific antibodies.

Hidalgo-Cantabrana and colleagues characterized the EPS of B. animalis subsp. lactis A1 and isogenic derivatives, which were obtained by exposure of strain A1 to bile salts (strain A1dOx) followed by cultivation for several generations in the absence of bile (strain A1dOxR). The strain A1dOxR displays a ropy phenotype and shows higher expression of a protein involved in rhamnose biosynthesis along with higher rhamnose content in its EPS [125]. Interestingly, these strains elicited different responses by peripheral blood mononuclear cells and isolated lamina propria immune cells of rats [126].

Despite the presence of EPS gene clusters in most bifidobacteria, it remains to be determined experimentally whether all bifidobacteria actually do produce EPS, if this EPS has a role in host colonisation, and how different EPS structures impact the immune response of the host.

2.6. Other Factors Involved in Host Colonisation

Besides bile, another important stress encountered by bifidobacteria during gastrointestinal transit and colonisation is acidic pH in the stomach and small intestine. A number of B. animalis subsp. animalis and lactis strains were shown to survive acidic pH in the physiological range (pH 3–5) in a strain-specific manner and tolerant strains exhibited higher ATPase activity at pH 4 than at pH 5 [127]. Ventura et al. identified the atp operon encoding the F1F0-type ATPase of B. lactis DSM10140 and were able to show that its expression was markedly increased upon exposure to acidic pH [128]. Similarly, various ATPase subunits were upregulated in B. longum subsp. longum NCIMB 8809 in response to acid stress (pH 4.8) as shown by a proteomic approach [129]. This suggests that pH resistance of this strain is inducible and might help to cope with the conditions of the gastrointestinal tract thereby supporting host colonisation. Interestingly, resistance to bile and low pH somehow seems to be connected in the closely related B. animalis subsp. lactis ILPA 4549. In this strain, expression of the F1F0-type ATPase and ATPase activity in the membrane was increased in the presence of bile [83]. Moreover, the spontaneous mutant B. lactis 4549dOx, which shows increased bile resistance, was also able to better tolerate exposure to acidic pH [83].

More recently, one of the mechanisms by which bifidobacteria might be able to sense their environment and regulate expression of factors important for host colonisation and adaptation to the intestinal niche has been investigated in more detail. A proteomic analysis in B. longum NCC2705 identified LuxS as one of the proteins with the most prominent host-induced changes in expression compared to in vitro growth [130]. LuxS is an enzyme of the activated methyl cycle of bacteria for recycling of S-adenosylmethionine [131]. By-products of this pathway are autoinducer-2 (AI-2)-like molecules, which are also used by bacteria as signaling molecules and were shown to be involved in biofilm formation, virulence, production of antimicrobials, motility, and genetic competence in a number of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria [132, 133]. All publicly available genome sequences of bifidobacteria harbour luxS homologues, which are functional in the production of AI-2 [134]. Moreover, homologous overexpression of luxS in B. longum NCC2705 increased AI-2 levels in the supernatant and enhanced biofilm formation [134]. For B. breve UCC2003, luxS was shown to be important for colonisation of the murine gastrointestinal tract [135].

3. Concluding Remarks

Collectively, the available data suggests that individual strains of bifidobacteria exert health-promoting effects on their hosts. An important prerequisite for these effects, is resistance to the conditions of the GIT and, at least, transient colonisation of the host. In recent years, there has been considerable progress in the identification of bifidobacterial structures that play a role in host colonisation and health-promoting effects. However, the vast majority of studies have been performed in vitro or in animal models. Based on the fact that they have not been substantiated sufficiently by clinical studies in humans, the European Food Safety Authority has rejected all of the health claims submitted for probiotics. This highlights the need for well-performed clinical trials with a clear definition of target groups and relevant biomarkers and a more detailed analysis of the molecular mechanisms responsible for host colonisation and the positive effects of probiotic bifidobacteria.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially funded by the German Academic Exchange Service/Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Grant D/09/04778 to Christian U. Riedel). Christina Westermann was supported by a PhD fellowship of the “Landesgraduiertenförderung Baden-Württemberg.”.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Wilson M. The indogenous microbiota of the gastrointestinal tract. In: Wi M, editor. Bacteriology of Humans: An Ecological Perspective. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing; 2008. pp. 266–326. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Round JL, Mazmanian SK. The gut microbiota shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2009;9(5):313–323. doi: 10.1038/nri2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sommer F, Bäckhed F. The gut microbiota-masters of host development and physiology. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2013;11:227–238. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matamoros S, Gras-Leguen C, Le Vacon F, Potel G, de La Cochetiere M-F. Development of intestinal microbiota in infants and its impact on health. Trends in Microbiology. 2013;21(4):167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arboleya S, Ruas-Madiedo P, Margolles A, et al. Characterization and in vitro properties of potentially probiotic Bifidobacterium strains isolated from breast-milk. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2011;149(1):28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernández L, Langa S, Martín V, et al. The human milk microbiota: origin and potential roles in health and disease. Pharmacological Research. 2013;69:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martín V, Maldonado-Barragán A, Moles L, et al. Sharing of bacterial strains between breast milk and infant feces. Journal of Human Lactation. 2012;28:36–44. doi: 10.1177/0890334411424729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurokawa K, Itoh T, Kuwahara T, et al. Comparative metagenomics revealed commonly enriched gene sets in human gut microbiomes. DNA Research. 2007;14(4):169–181. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsm018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature. 2012;486(7402):222–227. doi: 10.1038/nature11053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turroni F, Peano C, Pass DA, et al. Diversity of bifidobacteria within the infant gut microbiota. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036957.e36957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roger LC, Costabile A, Holland DT, Hoyles L, McCartney AL. Examination of faecal Bifidobacterium populations in breast- and formula-fed infants during the first 18 months of life. Microbiology. 2010;156(11):3329–3341. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.043224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riedel CU, Schwiertz A, Egert M. The stomach and small and large intestinal microbiomes. In: Marchesi JR, editor. The Human Microbiota and Microbiome. CABI; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee J-H, O'Sullivan DJ. Genomic insights into bifidobacteria. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2010;74(3):378–416. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00004-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grönlund M-M, Lehtonen O-P, Eerola E, Kero P. Fecal microflora in healthy infants born by different methods of delivery: permanent changes in intestinal flora after cesarean delivery. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 1999;28(1):19–25. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199901000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Penders J, Thijs C, Vink C, et al. Factors influencing the composition of the intestinal microbiota in early infancy. Pediatrics. 2006;118(2):511–521. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biasucci G, Rubini M, Riboni S, Morelli L, Bessi E, Retetangos C. Mode of delivery affects the bacterial community in the newborn gut. Early Human Development. 2010;86(supplement 1):S13–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bezirtzoglou E, Tsiotsias A, Welling GW. Microbiota profile in feces of breast- and formula-fed newborns by using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) Anaerobe. 2011;17(6):478–482. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hopkins MJ, Sharp R, Macfarlane GT. Age and disease related changes in intestinal bacterial populations assessed by cell culture, 16S rRNA abundance, and community cellular fatty acid profiles. Gut. 2001;48(2):198–205. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.2.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Claesson MJ, Cusack S, O'Sullivan O, et al. Composition, variability, and temporal stability of the intestinal microbiota of the elderly. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(1):4586–4591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000097107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dethlefsen L, Relman DA. Incomplete recovery and individualized responses of the human distal gut microbiota to repeated antibiotic perturbation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(1) supplement:4554–4561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000087107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manges AR, Labbe A, Loo VG, et al. Comparative metagenomic study of alterations to the intestinal microbiota and risk of nosocomial clostridum difficile-associated disease. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2010;202(12):1877–1884. doi: 10.1086/657319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vincent C, Stephens DA, Loo VG, et al. Reductions in intestinal Clostridiales precede the development of nosocomial Clostridium difficile infection. Microbiome. 2013;1, article 18 doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-1-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kerckhoffs APM, Samsom M, van der Rest ME, et al. Lower Bifidobacteria counts in both duodenal mucosa-associated and fecal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome patients. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2009;15(23):2887–2892. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeffery IB, O'Toole PW, Öhman L, et al. An irritable bowel syndrome subtype defined by species-specific alterations in faecal microbiota. Gut. 2012;61(7):997–1006. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rajilić-Stojanović M, Biagi E, Heilig HGHJ, et al. Global and deep molecular analysis of microbiota signatures in fecal samples from patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(5):1792–1801. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Willing BP, Dicksved J, Halfvarson J, et al. A pyrosequencing study in twins shows that gastrointestinal microbial profiles vary with inflammatory bowel disease phenotypes. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(6):1844.e1–1854.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lepage P, Hösler R, Spehlmann ME, et al. Twin study indicates loss of interaction between microbiota and mucosa of patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(1):227–236. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwiertz A, Jacobi M, Frick J-S, Richter M, Rusch K, Köhler H. Microbiota in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Pediatrics. 2010;157(2):240.e1–244.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frank DN, St. Amand AL, Feldman RA, Boedeker EC, Harpaz N, Pace NR. Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of microbial community imbalances in human inflammatory bowel diseases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(34):13780–13785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706625104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Penders J, Thijs C, Van Den Brandt PA, et al. Gut microbiota composition and development of atopic manifestations in infancy: the KOALA birth cohort study. Gut. 2007;56(5):661–667. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.100164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalliomäki M, Kirjavainen P, Eerola E, Kero P, Salminen S, Isolauri E. Distinct patterns of neonatal gut microflora in infants in whom atopy was and was not developing. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2001;107(1):129–134. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.111237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Björkstén B, Sepp E, Julge K, Voor T, Mikelsaar M. Allergy development and the intestinal microflora during the first year of life. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2001;108(4):516–520. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.118130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Angelis M, Piccolo M, Vannini L, et al. Fecal microbiota and metabolome of children with autism and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified. PLoS ONE. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076993.e76993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adams JB, Johansen LJ, Powell LD, Quig D, Rubin RA. Gastrointestinal flora and gastrointestinal status in children with autism—comparisons to typical children and correlation with autism severity. BMC Gastroenterology. 2011;11, article 22 doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-11-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parracho HMRT, Bingham MO, Gibson GR, McCartney AL. Differences between the gut microflora of children with autistic spectrum disorders and that of healthy children. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2005;54(10):987–991. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zoetendal EG, Akkermans ADL, De Vos WM. Temperature gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of 16S rRNA from human fecal samples reveals stable and host-specific communities of active bacteria. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1998;64(10):3854–3859. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3854-3859.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Faith JJ, Guruge JL, Charbonneau M, et al. The long-term stability of the human gut microbiota. Science. 2013;341(6141) doi: 10.1126/science.1237439.1237439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sekirov I, Russell SL, Caetano M Antunes L, Finlay BB. Gut microbiota in health and disease. Physiological Reviews. 2010;90(3):859–904. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00045.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bergstrom KSB, Kissoon-Singh V, Gibson DL, et al. Muc2 protects against lethal infectious colitis by disassociating pathogenic and commensal bacteria from the colonic mucosa. PLoS Pathogens. 2010;6(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000902.e1000902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leahy SC, Higgins DG, Fitzgerald GF, van Sinderen D. Getting better with bifidobacteria. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2005;98(6):1303–1315. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Picard C, Fioramonti J, Francois A, Robinson T, Neant F, Matuchansky C. Review article: bifidobacteria as probiotic agents—physiological effects and clinical benefits. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2005;22(6):495–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jeon SG, Kayama H, Ueda Y, et al. Probiotic Bifidobacterium breve induces IL-10-producing Tr1 cells in the colon. PLoS Pathogens. 2012;8(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002714.e1002714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kayama H, Ueda Y, Sawa Y, et al. Intestinal CX 3C chemokine receptor 1 high (CX 3CR1 high) myeloid cells prevent T-cell-dependent colitis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(13):5010–5015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114931109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hart AL, Lammers K, Brigidi P, et al. Modulation of human dendritic cell phenotype and function by probiotic bacteria. Gut. 2004;53(11):1602–1609. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.037325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Konieczna P, Groeger D, Ziegler M, et al. Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 administration induces Foxp3 T regulatory cells in human peripheral blood: potential role for myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Gut. 2012;61(3):354–366. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lyons A, O'Mahony D, O'Brien F, et al. Bacterial strain-specific induction of Foxp3+ T regulatory cells is protective in murine allergy models. Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 2010;40(5):811–819. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.López P, González-Rodríguez I, Gueimonde M, Margolles A, Suárez A. Immune response to Bifidobacterium bifidum strains support Treg/Th17 plasticity. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024776.e24776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fanning S, Hall LJ, Cronin M, et al. Bifidobacterial surface-exopolysaccharide facilitates commensal-host interaction through immune modulation and pathogen protection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(6):2108–2113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115621109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Di Giacinto C, Marinaro M, Sanchez M, Strober W, Boirivant M. Probiotics ameliorate recurrent Th1-mediated murine colitis by inducing IL-10 and IL-10-dependent TGF-β-bearing regulatory cells. Journal of Immunology. 2005;174(6):3237–3246. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Veiga P, Gallini CA, Beal C, et al. Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis fermented milk product reduces inflammation by altering a niche for colitogenic microbes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(42):18132–18137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011737107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Riedel CU, Foata F, Philippe D, Adolfsson O, Eikmanns BJ, Blum S. Anti-inflammatory effects of bifidobacteria by inhibition of LPS-induced NF-κB activation. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2006;12(23):3729–3735. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i23.3729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lammers KM, Helwig U, Swennen E, et al. Effect of probiotic strains on interleukin 8 production by HT29/19A cells. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2002;97(5):1182–1186. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim SW, Kim HM, Yang KM, et al. Bifidobacterium lactis inhibits NF-κB in intestinal epithelial cells and prevents acute colitis and colitis-associated colon cancer in mice. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2010;16(9):1514–1525. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ménard S, Candalh C, Bambou JC, Terpend K, Cerf-Bensussan N, Heyman M. Lactic acid bacteria secrete metabolites retaining anti-inflammatory properties after intestinal transport. Gut. 2004;53(6):821–828. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.026252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heuvelin E, Lebreton C, Grangette C, Pot B, Cerf-Bensussan N, Heyman M. Mechanisms involved in alleviation of intestinal inflammation by bifidobacterium breve soluble factors. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005184.e5184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Preising J, Philippe D, Gleinser M, et al. Selection of bifidobacteria based on adhesion and anti-inflammatory capacity in vitro for amelioration of murine colitis. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2010;76(9):3048–3051. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03127-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Philippe D, Heupel E, Blum-Sperisen S, Riedel CU. Treatment with Bifidobacterium bifidum 17 partially protects mice from Th1-driven inflammation in a chemically induced model of colitis. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2011;149(1):45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCarthy J, O'Mahony L, O'Callaghan L, et al. Double blind, placebo controlled trial of two probiotic strains in interleukin 10 knockout mice and mechanistic link with cytokine balance. Gut. 2003;52(7):975–980. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.7.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ewaschuk JB, Diaz H, Meddings L, et al. Secreted bioactive factors from Bifidobacterium infantis enhance epithelial cell barrier function. The American Journal of Physiology—Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 2008;295(5):G1025–G1034. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90227.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kwon H-K, Lee C-G, So J-S, et al. Generation of regulatory dendritic cells and CD4+Foxp3+ T cells by probiotics administration suppresses immune disorders. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(5):2159–2164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904055107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Asahara T, Nomoto K, Shimizu K, Watanuki M, Tanaka R. Increased resistance of mice to salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium infection by synbiotic administration of bifidobacteria and transgalactosylated oligosaccharides. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2001;91(6):985–996. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Asahara T, Shimizu K, Nomoto K, Hamabata T, Ozawa A, Takeda Y. Probiotic bifidobacteria protect mice from lethal infection with Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H7. Infection and Immunity. 2004;72(4):2240–2247. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.4.2240-2247.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fukuda S, Toh H, Hase K, et al. Bifidobacteria can protect from enteropathogenic infection through production of acetate. Nature. 2011;469(7331):543–547. doi: 10.1038/nature09646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Frick JS, Fink K, Kahl F, et al. Identification of commensal bacterial strains that modulate Yersinia enterocolitica and dextran sodium sulfate-induced inflammatory responses: implications for the development of probiotics. Infection and Immunity. 2007;75(7):3490–3497. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00119-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Collins JW, Akin AR, Kosta A, et al. Pre-treatment with Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003 modulates Citrobacter rodentiuminduced colonic inflammation and organ specificity. Microbiology. 2012;158(11):2826–2834. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.060830-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schell MA, Karmirantzou M, Snel B, et al. The genome sequence of Bifidobacterium longum reflects its adaptation to the human gastrointestinal tract. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(22):14422–14427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212527599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ventura M, O'Flaherty S, Claesson MJ, et al. Genome-scale analyses of health-promoting bacteria: probiogenomics. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2009;7(1):61–71. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hofmann AF. The enterohepatic circulation of bile acids in mammals: form and functions. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2009;14(7):2584–2598. doi: 10.2741/3399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hylemon PB, Zhou H, Pandak WM, Ren S, Gil G, Dent P. Bile acids as regulatory molecules. Journal of Lipid Research. 2009;50(8):1509–1520. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R900007-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Begley M, Gahan CGM, Hill C. The interaction between bacteria and bile. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 2005;29(4):625–651. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Begley M, Hill C, Gahan CGM. Bile salt hydrolase activity in probiotics. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2006;72(3):1729–1738. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.3.1729-1738.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ruiz L, O’Connell-Motherway M, Zomer A, de los Reyes-Gavilán CG, Margolles A, van Sinderen D. A bile-inducible membrane protein mediates bifidobacterial bile resistance. Microbial Biotechnology. 2012;5(4):523–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2011.00329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ruiz L, Zomer A, O'Connell-Motherway M, van Sinderen D, Margolles A. Discovering novel bile protection systems in Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003 through functional genomics. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2012;78(4):1123–1131. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06060-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gueimonde M, Garrigues C, van Sinderen D, de los Reyes-Gavilán CG, Margolles A. Bile-inducible efflux transporter from Bifidobacterium longum NCC2705, conferring bile resistance. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2009;75(10):3153–3160. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00172-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kim G-B, Lee BH. Genetic analysis of a bile salt hydrolase in Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis KL612. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2008;105(3):778–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jarocki P. Molecular characterization of bile salt hydrolase from bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis Bi30. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2011;21(8):838–845. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1103.03028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Grill J-P, Schneider F, Crociani J, Ballongue J. Purification and characterization of conjugated bile salt hydrolase from Bifidobacterium longum BB536. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1995;61(7):2577–2582. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.7.2577-2582.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kim G-B, Miyamoto CM, Meighen EA, Lee BH. Cloning and characterization of the bile salt hydrolase genes (bsh) from Bifidobacterium bifidum strains. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2004;70(9):5603–5612. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.9.5603-5612.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kim G-B, Yi S-H, Lee BH. Purification and characterization of three different types of bile salt hydrolases from Bifidobacterium strains. Journal of Dairy Science. 2004;87(2):258–266. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(04)73164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kim G-B, Brochet M, Lee BH. Cloning and characterization of a bile salt hydrolase (bsh) from Bifidobacterium adolescentis . Biotechnology Letters. 2005;27(12):817–822. doi: 10.1007/s10529-005-6717-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tanaka H, Hashiba H, Kok J, Mierau I. Bile salt hydrolase of Bifidobacterium longum: biochemical and genetic characterization. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2000;66(6):2502–2512. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.6.2502-2512.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gahan CGM, Hill C. Gastrointestinal phase of Listeria monocytogenes infection. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2005;98(6):1345–1353. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sánchez B, De Los Reyes-Gavilán CG, Margolles A. The F1F0-ATPase of Bifidobacterium animalis is involved in bile tolerance. Environmental Microbiology. 2006;8(10):1825–1833. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Watson D, Sleator RD, Hill C, Gahan CGM. Enhancing bile tolerance improves survival and persistence of Bifidobacterium and Lactococcus in the murine gastrointestinal tract. BMC Microbiology. 2008;8, article 176 doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ventura M, Turroni F, Motherway MO, MacSharry J, van Sinderen D. Host-microbe interactions that facilitate gut colonization by commensal bifidobacteria. Trends in Microbiology. 2012;20(10):467–476. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhurina D, Dudnik A, Waidmann MS, et al. High-quality draft genome sequence of bifidobacterium longum E18, isolated from a healthy adult. Genome Announcements. 2013;1(6) doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01084-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhurina D, Zomer A, Gleinser M, et al. Complete genome sequence of Bifidobacterium bifidum S17. Journal of Bacteriology. 2011;193(1):301–302. doi: 10.1128/JB.01180-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bottacini F, O’Connell Motherway M, Kuczynski J, et al. Comparative genomics of the Bifidobacterium breve taxon. BMC Genomics. 2014;15, article 170 doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sela DA, Chapman J, Adeuya A, et al. The genome sequence of Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis reveals adaptations for milk utilization within the infant microbiome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(48):18964–18969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809584105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sela DA, Mills DA. Nursing our microbiota: molecular linkages between bifidobacteria and milk oligosaccharides. Trends in Microbiology. 2010;18(7):298–307. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Marcobal A, Sonnenburg JL. Human milk oligosaccharide consumption by intestinal microbiota. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2012;18(supplement 4):12–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03863.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Turroni F, Bottacini F, Foroni E, et al. Genome analysis of Bifidobacterium bifidum PRL2010 reveals metabolic pathways for host-derived glycan foraging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(45):19514–19519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011100107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Holmes E, Kinross J, Gibson GR, et al. Therapeutic modulation of microbiota-host metabolic interactions. Science Translational Medicine. 2012;4(137) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004244.137rv6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.LoCascio RG, Desai P, Sela DA, Weimer B, Mills DA. Broad conservation of milk utilization genes in Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis as revealed by comparative genomic hybridization. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2010;76(22):7373–7381. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00675-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sela DA, Garrido D, Lerno L, et al. Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 α-fucosidases are active on fucosylated human milk oligosaccharides. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2012;78(3):795–803. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06762-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Garrido D, Nwosu C, Ruiz-Moyano S, et al. Endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidases from infant gut-associated bifidobacteria release complex N-glycans from human milk glycoproteins. Molecular and Cellular Proteomics. 2012;11(9):775–785. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.018119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yoshida E, Sakurama H, Kiyohara M, et al. Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis uses two different β-galactosidases for selectively degrading type-1 and type-2 human milk oligosaccharides. Glycobiology. 2012;22(3):361–368. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwr116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Johansson MEV, Sjövall H, Hansson GC. The gastrointestinal mucus system in health and disease. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2013;10:352–561. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Laparra JM, Sanz Y. Comparison of in vitro models to study bacterial adhesion to the intestinal epithelium. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 2009;49(6):695–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2009.02729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tuomola E, Crittenden R, Playne M, Isolauri E, Salminen S. Quality assurance criteria for probiotic bacteria. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2001;73(2):393S–398S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.2.393s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lebeer S, Vanderleyden J, de Keersmaecker SCJ. Host interactions of probiotic bacterial surface molecules: comparison with commensals and pathogens. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2010;8(3):171–184. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bernet M-F, Brassart D, Neeser J-R, Servin AL. Adhesion of human bifidobacterial strains to cultured human intestinal epithelial cells and inhibition of enteropathogen-cell interactions. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1993;59(12):4121–4128. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.12.4121-4128.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Candela M, Bergmann S, Vici M, et al. Binding of human plasminogen to Bifidobacterium. Journal of Bacteriology. 2007;189(16):5929–5936. doi: 10.1128/JB.00159-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Candela M, Biagi E, Centanni M, et al. Bifidobacterial enolase, a cell surface receptor for human plasminogen involved in the interaction with the host. Microbiology. 2009;155(10):3294–3303. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.028795-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Candela M, Centanni M, Fiori J, et al. DnaK from Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis is a surface-exposed human plasminogen receptor upregulated in response to bile salts. Microbiology. 2010;156(6):1609–1618. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.038307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Crociani J, Grill J-P, Huppert M, Ballongue J. Adhesion of different bifidobacteria strains to human enterocyte-like Caco-2 cells and comparison with in vivo study. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 1995;21(3):146–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1995.tb01027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Del Re B, Sgorbati B, Miglioli M, Palenzona D. Adhesion, autoaggregation and hydrophobicity of 13 strains of Bifidobacterium longum. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 2000;31(6):438–442. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gopal PK, Prasad J, Smart J, Gill HS. In vitro adherence properties of Lactobacillus rhamnosus DR20 and Bifidobacterium lactis DR10 strains and their antagonistic activity against an enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli . International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2001;67(3):207–216. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(01)00440-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Guglielmetti S, Tamagnini I, Mora D, et al. Implication of an outer surface lipoprotein in adhesion of Bifidobacterium bifidum to Caco-2 cells. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2008;74(15):4695–4702. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00124-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Guglielmetti S, Tamagnini I, Minuzzo M, et al. Study of the adhesion of Bifidobacterium bifidum MIMBb75 to human intestinal cell lines. Current Microbiology. 2009;59(2):167–172. doi: 10.1007/s00284-009-9415-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Riedel CU, Foata F, Goldstein DR, Blum S, Eikmanns BJ. Interaction of bifidobacteria with Caco-2 cells-adhesion and impact on expression profiles. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2006;110(1):62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gleinser M, Grimm V, Zhurina D, Yuan J, Riedel CU. Improved adhesive properties of recombinant bifidobacteria expressing the Bifidobacterium bifidum-specific lipoprotein BopA. Microbial Cell Factories. 2012;11, article 80 doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-11-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Pan W-H, Li P-L, Liu Z. The correlation between surface hydrophobicity and adherence of Bifidobacterium strains from centenarians' faeces. Anaerobe. 2006;12(3):148–152. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Juntunen M, Kirjavainen PV, Ouwehand AC, Salminen SJ, Isolauri E. Adherence of probiotic bacteria to human intestinal mucus in healthy infants and during rotavirus infection. Clinical and Diagnostic Laboratory Immunology. 2001;8(2):293–296. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.8.2.293-296.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kirjavainen PV, Ouwehand AC, Isolauri E, Salminen SJ. The ability of probiotic bacteria to bind to human intestinal mucus. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 1998;167(2):185–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.González-Rodríguez I, Sánchez B, Ruiz L, et al. Role of extracellular transaldolase from Bifidobacterium bifidum in mucin adhesion and aggregation. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2012;78(11):3992–3998. doi: 10.1128/AEM.08024-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wei X, Yan X, Chen X, et al. Proteomic analysis of the interaction of Bifidobacterium longum NCC2705 with the intestine cells Caco-2 and identification of plasminogen receptors. Journal of Proteomics. 2014;108:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2014.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Henderson B, Martin A. Bacterial moonlighting proteins and bacterial virulence. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 2013;358:155–213. doi: 10.1007/82_2011_188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kainulainen V, Reunanen J, Hiippala K, et al. BopA has no major role in the adhesion of Bifidobacterium bifidum to intestinal epithelial cells, extracellular matrix proteins and mucus. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2013 doi: 10.1128/AEM.01993-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Westermann C, Zhurina DS, Baur A, Shang W, Yuan J, Riedel CU. Exploring the genome sequence of Bifidobacterium bifidum S17 for potential players in host-microbe interactions. Symbiosis. 2012;58(1-3):191–200. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Turroni F, Serafini F, Foroni E, et al. Role of sortase-dependent pili of Bifidobacterium bifidum PRL2010 in modulating bacterium-host interactions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(27):11151–11156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303897110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Motherway MO, Zomer A, Leahy SC, et al. Functional genome analysis of Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003 reveals type IVb tight adherence (Tad) pili as an essential and conserved host-colonization factor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(27):11217–11222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105380108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Foroni E, Serafini F, Amidani D, et al. Genetic analysis and morphological identification of pilus-like structures in members of the genus Bifidobacterium. Microbial Cell Factories. 2011;10(supplement 1, article S16) doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-10-S1-S16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Hidalgo-Cantabrana C, Sánchez B, Milani C, Ventura M, Margolles A, Ruas-Madiedo P. Genomic overview and biological functions of exopolysaccharide biosynthesis in Bifidobacterium spp. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2014;80:9–18. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02977-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Hidalgo-Cantabrana C, Sánchez B, Moine D, et al. Insights into the ropy phenotype of the exopolysaccharide-producing strain Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis A1DOXR. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2013;79(12):3870–3874. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00633-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hidalgo-Cantabrana C, Nikolic M, López P, et al. Exopolysaccharide-producing Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis strains and their polymers elicit different responses on immune cells from blood and gut associated lymphoid tissue. Anaerobe. 2014;26:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Matsumoto M, Ohishi H, Benno Y. H+-ATPase activity in Bifidobacterium with special reference to acid tolerance. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2004;93(1):109–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ventura M, Canchaya C, van Sinderen D, Fitzgerald GF, Zink R. Bifidobacterium lactis DSM 10140: identificafion of the atp (atpBEFHAGDC) operon and analysis of its genetic structure, characteristics, and phylogeny. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2004;70(5):3110–3121. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.5.3110-3121.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Sánchez B, Champomier-Vergès M-C, Collado MDC, et al. Low-pH adaptation and the acid tolerance response of Bifidobacterium longum biotype longum. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2007;73(20):6450–6459. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00886-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Yuan J, Wang B, Sun Z, et al. Analysis of host-inducing proteome changes in Bifidobacterium longum NCC2705 grown in vivo. Journal of Proteome Research. 2008;7(1):375–385. doi: 10.1021/pr0704940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Parveen N, Cornell KA. Methylthioadenosine/S-adenosylhomocysteine nucleosidase, a critical enzyme for bacterial metabolism. Molecular Microbiology. 2011;79(1):7–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07455.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Vendeville A, Winzer K, Heurlier K, Tang CM, Hardie KR. Making “sense” of metabolism: autoinducer-2, LuxS and pathogenic bacteria. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2005;3(5):383–396. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Pereira CS, Thompson JA, Xavier KB. AI-2-mediated signalling in bacteria. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 2013;37(2):156–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Sun Z, He X, Brancaccio VF, Yuan J, Riedel CU. Bifidobacteria exhibit luxS-dependent autoinducer 2 activity and biofilm formation. PLoS ONE. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088260.e88260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Christiaen SEA, O'Connell Motherway M, Bottacini F, et al. Autoinducer-2 plays a crucial role in gut colonization and probiotic functionality of Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098111.e98111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]