Abstract

Objective

To examine the association of current cigarette smoking and pack-years smoked to the incidence and progression of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and to examine the interactions of current smoking and pack-years smoked with Complement Factor H (CFH, rs1061170) and Age-Related Maculopathy Susceptibility 2 (ARMS2, rs10490924) genotype.

Design

A longitudinal population-based study of AMD in a representative American community. Examinations were performed every 5 years over a 20-year period.

Participants

4439 participants in the population-based Beaver Dam Eye Study.

Methods

AMD status was determined from grading retinal photographs. Multi-state models were used to model the relationship of current smoking and pack-years smoked and interactions with CFH and ARMS2 to the incidence and progression of AMD over the entire age range.

Main Outcome Measures

Incidence and progression of AMD over a 20-year period and interactions between current smoking and pack-years smoked with CFH and ARMS2 genotype.

Results

The incidence of early AMD over the 20-year period was 24.4% and the incidence of late AMD was 4.5%. Current smoking was associated with an increased risk of transitioning from minimal to moderate early AMD. A greater number of pack-years smoked was associated with an increased risk of transitioning from no AMD to minimal early AMD and from severe early AMD to late AMD. Current smoking and a greater number of pack-years smoked were associated with an increased risk of death. There were no statistically significant multiplicative interactions between current smoking or pack-years smoked and CFH or ARMS2 genotype.

Conclusions

Current smoking and a greater number of pack-years smoked increase the risk of the progression of AMD. This has important health care implications because smoking is a modifiable behavior.

Age-related Macular Degeneration (AMD), a disease with a complex risk factor profile, is a leading cause of blindness in the United States.1–3 Smoking is one of the few modifiable factors consistently shown to be associated with AMD.4;5 Smoking affects processes (e.g., immune activation, depression of anti-oxidant levels, reduction of choroidal blood flow, decrease in luteal pigments in retina, reduction of drug detoxification by retinal pigment epithelium [RPE], nicotine potentiation of angiogenic activities) hypothesized to be involved in the pathogenesis of AMD.6–12 The purpose of this report is to examine the relationship of smoking to the incidence and progression of AMD over a 20-year period in the population-based Beaver Dam Eye Study cohort. In addition, we examine the interaction effects of current smoking and pack-years smoked and the presence of AMD candidate gene single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) Complement Factor H (CFH, rs1061170) and Age-Related Maculopathy Susceptibility 2 (ARMS2, rs10490924) to these outcomes. This report builds upon earlier observations on smoking and AMD over shorter follow-up of the cohort13–16 by examining interactions with CFH and ARMS2 and by modeling relationships using a multi-state-model (MSM), which allows us to incorporate incidence and progression of disease as well as death into a simple, biologically plausible model rather than modeling each aspect of the disease process in isolation.

Methods

Participants

A private census of Beaver Dam, Wisconsin was performed in 1987–1988 to identify all residents eligible for the study.17 Of the 5924 eligible, 4926 (83%) persons aged 43 to 86 years participated in the baseline examination in 1988–1990. Ninety-nine percent of the population was white and 56% was female. The cohort was re-examined at 5- (n=3722), 10- (n=2962), 15- (n=2375), and 20-year (n=1913) follow-ups. The mean and median times between the baseline and 20-year follow-up examinations were 20.4 years (standard deviation = 0.6) and 20.3 years, respectively. There was greater than 80% participation among survivors at each examination. Differences between participants and nonparticipants have been presented elsewhere.17–21

Participants were examined at the study suite, a nursing home, or their homes. The same protocols for measurements relevant to this investigation were used at each examination.22;23 All data were collected with Institutional Review Board approval from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in conformity with all federal and state laws, the work was HIPAA compliant, and the study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Genetic Measurements

Two common SNPs associated with age-related macular degeneration (AMD), Y402H in CFH and A69S in ARMS2, were used in this study. A69S was genotyped using two different platforms, one Taqman assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA) and the other Illumina array (San Diego, California, USA) in 2248 and 2940 samples, respectively. Of 588 samples genotyped with both platforms, a genotype concordance of 99.7% was observed. The variant Y402H was genotyped using a Taqman assay in 3015 samples in the BDES, which is described elsewhere.24;25 This variant was also imputed in 2940 samples based on 70 common SNPs (minor allele frequency >0.05), which were genotyped using Illumina array, in the CFH locus using the MACH program version 1.0.26 A concordance rate of 99.8% was observed among 1476 samples for which both genotyped and imputed data were available.

Grading AMD

Photographs of the retina were taken after pupil dilation according to protocol and graded in masked fashion by experienced graders.23;27 The Wisconsin Age-Related Maculopathy Grading System was used to assess the presence and severity of lesions associated with AMD from the fundus photographs. Grading procedures, lesion descriptions, and detailed definitions of presence and severity have appeared elsewhere.22;23;27–29

The severity of AMD was determined using the 5-step 3-continent consortium AMD Severity Scale.30 The definitions of each step are presented in Table 1 (available at http://aaojournal.org).

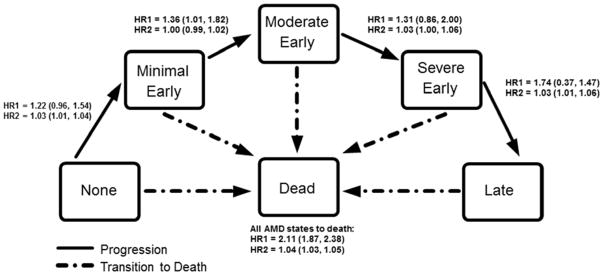

The 20-year incidence of early AMD in the worse eye was defined by developing Level 20, 30, or 40 in at least 1 eye in persons without any lesion defining early or late AMD at any previous exam. Similarly, incidence of late AMD was defined by developing level 50 in at least 1 eye in persons without late AMD at any previous exam. The relationship of current smoking and pack-years smoked to the incidence and progression of AMD over the 20-year period was evaluated using an MSM (Figure 1). Using the MSM, incidence of early AMD was defined as transitioning from no AMD to minimal early AMD because all transitions to higher levels were assumed to have passed through level 20. Similarly, incidence of late AMD was defined as transitioning from severe early AMD to late AMD. Progression of AMD was defined as having either eye transition to a more severe AMD level.

Figure 1.

The 3-Continent Consortium five-step severity scale for age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Arrows indicate possible transitions along the scale. Hazard ratios indicate the hazard of making the transition indicated by the arrow for a current smoker compared to a non-current smoker (HR1) and per 5 pack-years smoked (HR2), adjusted for age and sex. AMD, age-related macular degeneration; HR, hazard ratio.

Definitions

Age and smoking habits were defined at each examination. Age was centered at 70 years and scaled per 5 years. Smoking habits were determined from self-report. Smoking status was analyzed as current smoking or non-smoking. Current smokers were identified as persons having smoked ≥100 cigarettes in their lifetime and who were still smoking at the time of the examination. Non-smokers included never smokers, (those who reported to have smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes) and past smokers (those who were no longer smoking at the time of the exam). Pack-years smoked was defined as the average number of cigarettes smoked in a day divided by 20 and multiplied by the number of years the individual smoked. Smoking status and pack-years smoked were assumed to remain constant over a 5-year interval.

Statistical Analysis

The 20-year incidence of early and late AMD in the worse eye was calculated using chi-square tables with SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). We first examined the relationship of history of current smoking and pack-years smoked to the incidence and progression of AMD using the MSMs, adjusting only for age and sex. Then, in separate MSMs, we examined the interaction of current smoking and CFH, current smoking and ARMS2, pack-years smoked and CFH, and pack-years smoked and ARMS2 with the incidence and progression of AMD. Each interaction term was modeled using a 6-level variable, grouping each individual by smoking status (current smoking or non-smoking) or pack-years (0 or >0) and by the number of risk alleles for CFH or ARMS2 (0, 1 or 2). All other groups were compared to the reference group of non-smokers or those with 0 pack-years smoked with no risk alleles for that SNP. The p-value for the overall significance of each interaction term was calculated by running a separate MSM including a multiplicative interaction term between current smoking or pack-years smoked and each SNP. P<0.05 was used to determine statistical significance in all models.

MSM analyses were conducted in R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria) using the MSM package.31 The MSM permits staged modeling of AMD progression incorporating all facets of the natural history of AMD as well as death into a single, biologically plausible model rather than modeling aspects of the disease process in isolation. It uses a biological meaningful time scale (participant age) rather than an artificial time scale (time of study) and incorporates time-varying covariates by updating covariate values at observation times. Covariate effects on transition intensities are summarized as hazard ratios. Individuals were allowed to progress along transitions shown in Figure 1. Individuals who were not observed to transition through an intermediate level are assumed to have made the transition between exams. Because few individuals had apparent improvement in their AMD status, regression was not included as an outcome in this analysis.

Results

The cohort

There were 4439 individuals who had smoking status recorded and at least 1 eye gradable for AMD lesions during at least 1 pair of BDES exams and had genotype data for CFH or ARMS2. Reliable AMD data for at least 1 eye were available for 13797 person-visits, 4261 at baseline, 3177 at 5-year follow-up, 2611 at 10-year follow-up, 2096 at 15-year follow-up, and 1652 at the 20-year follow-up.

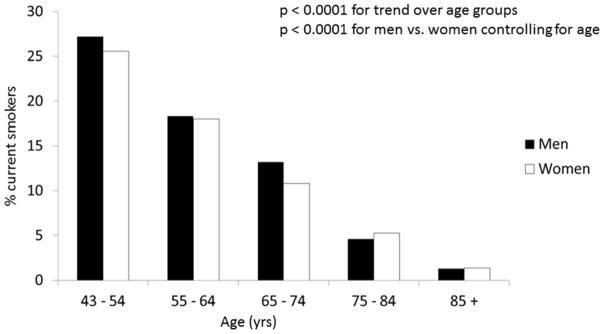

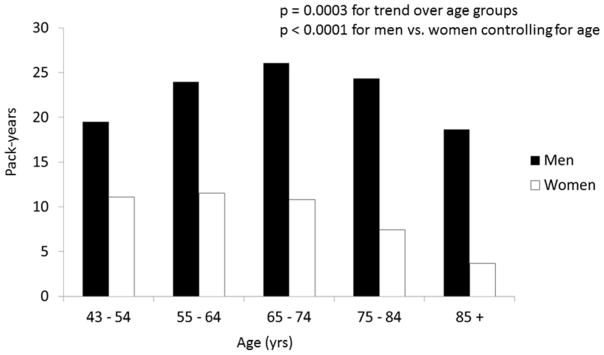

Adjusting for age, the proportion of individuals who were past smokers increased and the proportion of individuals who were current smokers, as well as the number of pack-years smoked, decreased during the course of the study. Individuals at later exams were more likely to be heavier and have a more severe AMD level than at previous exams (Table 2). Current smoking and number of pack-years smoked decreased by age group and, adjusting for age, were greater in men than in women (Figures 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Characteristics at each Examination Phase of Individuals Included in Analyses.

| Risk factor | BDES 1 1988–1990 N=4261 |

BDES 2 1993–1995 N=3177 |

BDES 3 1998–2000 N=2611 |

BDES4 2003–2005 N=2096 |

BDES5 2008–2010 N=1652 |

P value* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Mean or % | SD | Mean or % | SD | Mean or % | SD | Mean or % | SD | Mean or % | SD | ||

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Age, years | 61.34 | 10.93 | 65.05 | 10.41 | 68.83 | 9.86 | 71.86 | 9.03 | 75.43 | 7.99 | <.0001 |

| Sex, male | 43.97 | 43.45 | 42.15 | 41.33 | 41.46 | 0.41 | |||||

| Smoking status | <.0001 | ||||||||||

| Past | 35.70 | 39.49 | 42.71 | 42.65 | 43.85 | ||||||

| Current | 19.79 | 14.79 | 9.74 | 8.56 | 6.53 | ||||||

| Pack-years smoked | 17.50 | 26.64 | 16.14 | 24.97 | 14.76 | 24.68 | 28.40 | 27.75 | 28.04 | 28.14 | <.0001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.79 | 5.40 | 29.51 | 5.51 | 29.82 | 6.00 | 30.28 | 6.06 | 30.72 | 6.38 | <.0001 |

| AMD severity level | <.0001 | ||||||||||

| No AMD | 77.56 | 73.08 | 71.93 | 72.40 | 68.82 | ||||||

| Minimal early AMD | 14.61 | 15.60 | 14.68 | 13.39 | 14.18 | ||||||

| Moderate early AMD | 5.32 | 7.92 | 8.59 | 7.83 | 9.63 | ||||||

| Severe early AMD | 0.75 | 1.32 | 2.17 | 2.50 | 2.59 | ||||||

| Late AMD | 1.76 | 2.08 | 2.64 | 3.87 | 4.78 | ||||||

| CFH genotype | |||||||||||

| T/T | 39.11 | ||||||||||

| C/T | 47.40 | ||||||||||

| C/C | 13.49 | ||||||||||

| ARMS2 genotype | |||||||||||

| G/G | 60.20 | ||||||||||

| G/T | 34.83 | ||||||||||

| T/T | 4.97 | ||||||||||

AMD, age-related macular degeneration; ARMS2, age-related maculopathy susceptibility 2; BDES, Beaver Dam Eye Study; BMI, body mass index; CFH, complement factor H; SD, standard deviation.

Adjusted for age.

Figure 2.

Distribution of current smoking by age and sex in the Beaver Dam Eye Study.

Figure 3.

Distribution of pack-years smoked by age and sex in the Beaver Dam Eye Study.

The overall incidence of early AMD over the 20-year period was 24.4% and incidence for late AMD was 4.5%. Current smoking was associated with an increased risk of transitioning from minimal to moderate early AMD (hazard ration [HR] =1.36, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.01, 1.82) and a greater number of pack-years smoked was associated with an increased risk of transitioning from no AMD to minimal early AMD (HR=1.03, 95% CI 1.01, 1.04), and from severe early to late AMD (HR=1.03, 95% CI 0.01, 1.06) (Figure 1). Current smoking and a greater number of pack-years smoked were associated with an increased risk of death in all models.

The genotype distribution for CFH was 39.2% T/T, 47.3% T/C, and 13.6% C/C and for ARMS2 it was 60.7% G/G, 34.5% G/T, and 4.8% T/T. There were no statistically significant interactions between current smoking or pack-years smoked and CFH and ARMS2 genotype (Table 3).

Table 3.

Relationship of the Interaction of Smoking Status and Complement Factor H and Age-related Maculopathy Susceptibility 2 Genotype to the Incidence and Progression of Age-related Macular Degeneration and Incidence of Death.

| Model, risk factor, genotype | No AMD to minimal early AMD HR (95% CI) | P value* | Minimal early AMD to moderate early AMD HR (95% CI) | P value* | Moderate early AMD to severe early AMD HR (95% CI) | P value* | Severe early AMD to late AMD HR (95% CI) | P value* | All AMD states to death HR (95% CI) | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current smoking and CFH interaction | 0.11 | 0.63 | 0.86 | 0.99 | 0.14 | |||||

| Non-smoker, T/T | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Smoker, T/T | 1.15 (0.77, 1.72) | 1.21 (0.73, 2.01) | 1.26 (0.53, 2.99) | 0.77 (0.17, 3.49) | 1.95 (1.62, 2.35) | |||||

| Non-smoker, T/C | 1.34 (1.11, 1.61) | 1.19 (0.94, 1.50) | 1.80 (1.28, 2.54) | 1.33 (0.82, 2.14) | 0.92 (0.83, 1.01) | |||||

| Smoker, T/C | 1.40 (0.97, 2.03) | 1.61 (1.03, 2.50) | 2.16 (1.17, 3.97) | 1.01 (0.34, 2.97) | 2.20 (1.85, 2.61) | |||||

| Non-smoker, C/C | 1.75 (1.36, 2.25) | 2.03 (1.50, 2.75) | 1.79 (1.16, 2.76) | 1.17 (0.66, 2.08) | 1.02 (0.89, 1.17) | |||||

| Smoker, C/C | 3.42 (2.17, 5.37) | 3.82 (1.89, 7.69) | 2.50 (1.10, 5.69) | 0.82 (0.24, 2.82) | 1.78 (1.29, 2.46) | |||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Current smoking and ARMS2 interaction | 0.32 | 0.54 | 0.45 | 0.99 | 0.61 | |||||

| Non-smoker, G/G | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Smoker, G/G | 1.30 (0.97, 1.76) | 1.13 (0.75, 1.71) | 1.22 (0.66, 2.24) | 0.69 (0.21, 2.29) | 2.01 (1.73, 2.34) | |||||

| Non-smoker, G/T | 1.22 (1.03, 1.45) | 1.36 (1.10, 1.69) | 0.92 (0.68, 1.24) | 1.80 (1.21, 2.68) | 0.94 (0.86, 1.04) | |||||

| Smoker, G/T | 1.15 (0.77, 1.73) | 2.21 (1.42, 3.43) | 1.60 (0.86, 2.95) | 1.45 (0.57, 3.69) | 2.14 (1.77, 2.58) | |||||

| Non-smoker, T/T | 2.25 (1.61, 3.15) | 2.17 (1.47, 3.19) | 2.23 (1.47, 3.38) | 2.67 (1.58, 4.54) | 0.98 (0.80, 1.19) | |||||

| Smoker, T/T | 3.97 (1.87, 8.42) | 3.28 (1.06, 10.17) | 1.49 (0.33, 6.76) | 1.53 (0.11, 22.12) | 2.07 (1.35, 3.16) | |||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Pack-years smoked and CFH interaction | 0.69 | 0.51 | 0.93 | 0.27 | 0.44 | |||||

| Pack-years=0, T/T | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Pack-years>0, T/T | 1.05 (1.02, 1.08) | 1.00 (0.96, 1.05) | 1.01 (0.95, 1.08) | 0.98 (0.87, 1.10) | 1.04 (1.02, 1.05) | |||||

| Pack-years=0, C/T | 1.61 (1.13, 2.31) | 0.95 (0.60, 1.51) | 1.15 (0.57, 2.31) | 0.76 (0.29, 1.98) | 0.60 (0.03,13.47) | |||||

| Pack-years>0, T/C | 1.03 (1.00, 1.06) | 1.02 (0.99, 1.05) | 1.05 (1.00, 1.09) | 1.13 (1.05, 1.23) | 1.03 (1.02, 1.05) | |||||

| Pack-years=0, C/C | 2.93 (1.84, 4.65) | 2.95 (1.62, 5.37) | 0.92 (0.34, 2.46) | 2.27 (0.66, 7.80) | 1.86 (0.18, 19.24) | |||||

| Pack-years>0, C/C | 1.00 (0.95, 1.05) | 0.98 (0.93, 1.03) | 1.10 (0.98, 1.23) | 0.92 (0.83, 1.02) | 1.03 (1.00, 1.06) | |||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Pack-years smoked and ARMS2 interaction | 0.34 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.55 | |||||

| Pack-years=0, G/G | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Pack-years>0, G/G | 1.03 (1.00, 1.06) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.04) | 1.06 (1.01, 1.10) | 0.98 (0.92, 1.04) | 1.04 (1.03, 1.05) | |||||

| Pack-years=0, G/T | 1.15 (0.83, 1.59) | 1.59 (1.07, 2.35) | 1.39 (0.77, 2.52) | 1.46 (0.67, 3.19) | 0.96 (0.82, 1.13) | |||||

| Pack-years>0, G/T | 1.04 (1.01, 1.07) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) | 1.02 (0.98, 1.06) | 1.07 (0.99, 1.15) | 1.03 (1.02, 1.04) | |||||

| Pack-years=0, T/T | 1.69 (0.66, 4.33) | 3.46 (1.33, 9.00) | 2.04 (0.69, 5.97) | 1.31 (0.39, 4.43) | 1.12 (0.79, 1.59) | |||||

| Pack-years>0, T/T | 1.10 (0.93, 1.30) | 0.98 (0.86, 1.12) | 1.12 (0.97, 1.28) | 1.12 (0.97, 1.30) | 1.02 (0.99, 1.05) | |||||

AMD, age-related macular degeneration; ARMS2, age-related maculopathy susceptibility-2; CFH, complement factor H; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

For interaction for transition.

Adjusted for age and sex.

Discussion

In the BDES, using multistate modeling, we observed that current smoking was associated with an increased risk of progression from minimal to moderate early AMD and a greater number of pack-years smoked was associated with the incidence of early and late AMD.

The finding of a relation of smoking habits with the incidence of early AMD or AMD progression is consistent with our earlier reported findings from the 5-, 10-, and 15-year follow-up and with data from other studies.5;13–16 It is consistent with hypothesized biological mechanisms linking smoking to the pathogenesis of AMD.6–12 Our finding that a greater number of pack-years smoked but not current smoking was related to the incidence of early and late AMD may have arisen because pack-years smoked better reflects the amount of exposure over a lifetime of smoking. It may also be due to selective mortality in smokers who were more likely to transition from severe early AMD to death (2.10, 95% CI 1.90, 2.40) than from severe early to late AMD (HR=1.70, 95% CI 0.40, 1.50). While they did not reach statistical significance, the direction of the HRs indicate that current smoking may also put an individual at increased risk of developing early and late AMD.

We did not find an interaction between CFH and current smoking or pack-years smoked and late AMD. Several other studies have also concluded that there is no interaction between smoking and CFH32–36; however, some have reported an increased risk of late AMD in smokers with the C/C genotype.37–39 We have found a similar relationship where, compared to non-smokers with the T/T genotype, current smokers with the C/C CFH genotype had a higher risk for incident early AMD (HR=3.42) compared to individuals in the other risk groups (HRs ranged from 1.15 to 1.75). However, a test for a multiplicative interaction between current smoking and CFH genotype for incident early AMD did not reach statistical significance. It is possible that other unmeasured factors, e.g., inhalation, filtration, nicotine levels, additives to cigarettes, and other tobacco-related differences in the type of cigarettes smoked might, in part, explain differences in associations found among the studies examining this relationship. Last, it is possible that smoking and number of pack-years smoked may not increase the risk of incidence of late AMD in combination with the C/C CFH genotype in our population.

We also did not find an interaction between the ARMS2 genotype and current smoking or pack-years smoked for the incidence and progression of AMD. This is in contrast with two case-control studies that found strong combined effects of ARMS2 genotype and smoking on the incidence of late AMD.40;41 However, both the presence of the ARMS2 risk allele and the incidence of late AMD are infrequent in our population and it is possible that we are underpowered to detect such an interaction compared to case-control studies which are enriched to include a large proportion of individuals with late AMD

Our study has many strengths, including the use of standard protocols to measure AMD from fundus photographs over a 20-year period in a representative population-based study. In addition, use of the MSM allows us to model incidence and progression of early AMD lesions as well as death, which is associated with smoking, in a single model that is able to account for changes in smoking habits and AMD status over the course of an individual’s lifetime.

One limitation of our study is that, because current smoking and a greater number of pack-years smoked are associated with an increased risk of death, we cannot rule out the possibility that our inability to detect associations and interactions was due, in part, to selective mortality and a decrease in the rate of current smoking and pack-years smoked at older ages. Second, the number of pack-years smoked was determined from self-report and differences in rounding or recall by a participated at each visit may add variability to this measure.

In conclusion, a greater number of pack-years smoked increases the risk of incident, early, and late AMD. More studies are needed to examine the interaction of smoking and CFH and ARMS2 genotype to the incidence and progression of AMD and its lesions. This has important health care implications because smoking is a modifiable behavior.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This research is supported by National Institutes of Health grant EY06594 (Drs. B. E. K. Klein, R. Klein). The National Eye Institute provided funding for entire study, including collection and analyses of data. Additional support was provided by Senior Scientific Investigator Awards from Research to Prevent Blindness (Drs. B. E. K. Klein and R. Klein). Neither funding organization had any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: No conflicting relationship exists for any author.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Congdon N, O’Colmain B, Klaver CC, et al. Causes and prevalence of visual impairment among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:477–85. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferris FL, III, Tielsch JM. Blindness and visual impairment: a public health issue for the future as well as today. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:451–2. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedman DS, O’Colmain BJ, Munoz B, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:564–72. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chakravarthy U, Wong TY, Fletcher A, et al. Clinical risk factors for age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Ophthalmol. 2010;10:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-10-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thornton J, Edwards R, Mitchell P, et al. Smoking and age-related macular degeneration: a review of association. Eye (Lond) 2005;19:935–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beatty S, Koh H, Phil M, et al. The role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Surv Ophthalmol. 2000;45:115–34. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(00)00140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bettman JW, Fellows V, Chao P. The effect of cigarette smoking on the intraocular circulation. AMA Arch Ophthalmol. 1958;59:481–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1958.00940050037002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman E. Choroidal blood flow. Pressure-flow relationships. Arch Ophthalmol. 1970;83:95–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1970.00990030097018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammond BR, Jr, Wooten BR, Snodderly DM. Cigarette smoking and retinal carotenoids: implications for age-related macular degeneration. Vision Res. 1996;36:3003–9. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(96)00008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pryor WA, Hales BJ, Premovic PI, Church DF. The radicals in cigarette tar: their nature and suggested physiological implications. Science. 1983;220:425–7. doi: 10.1126/science.6301009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stryker WS, Kaplan LA, Stein EA, et al. The relation of diet, cigarette smoking, and alcohol consumption to plasma beta-carotene and alpha-tocopherol levels. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;127:283–96. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suner IJ, Espinosa-Heidmann DG, Marin-Castano ME, et al. Nicotine increases size and severity of experimental choroidal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:311–7. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein R, Klein BE, Moss SE. Relation of smoking to the incidence of age-related maculopathy. The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:103–10. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein R, Klein BE, Tomany SC, Moss SE. Ten-year incidence of age-related maculopathy and smoking and drinking: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:589–98. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein R, Knudtson MD, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein BE. Further observations on the association between smoking and the long-term incidence and progression of age-related macular degeneration: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:115–21. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomany SC, Wang JJ, Van LR, et al. Risk factors for incident age-related macular degeneration: pooled findings from 3 continents. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1280–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein R, Klein BE, Linton KL, De Mets DL. The Beaver Dam Eye Study: visual acuity. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1310–5. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein R, Klein BE, Lee KE, et al. Changes in visual acuity in a population over a 10-year period : The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:1757–66. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00769-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein R, Klein BE, Lee KE, et al. Changes in visual acuity in a population over a 15-year period: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:539–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein R, Klein BE, Lee KE. Changes in visual acuity in a population. The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1996;103:1169–78. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(96)30526-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klein R, Lee KE, Gangnon RE, Klein BE. Incidence of visual impairment over a 20-year period: the beaver dam eye study. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:1210–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.11.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klein R, Klein BE. Manual of Operations. US Department of Commerce; Springfield, VA: 1995. The Beaver Dam Eye Study II; pp. 61–90. NTIS Accession No. PB95-273827. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klein R, Klein BE The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Manual of Operations, Revised. Springfield, VA: National Technical Information Service; 1991. Accession No. PB91-149823. Ref Type: Report. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sivakumaran TA, Igo RP, Jr, Kidd JM, et al. A 32 kb critical region excluding Y402H in CFH mediates risk for age-related macular degeneration. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e25598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson CL, Klein BE, Klein R, et al. Complement factor H and hemicentin-1 in age-related macular degeneration and renal phenotypes. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:2135–48. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang L, Li Y, Singleton AB, et al. Genotype-imputation accuracy across worldwide human populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:235–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein R, Davis MD, Magli YL, et al. The Wisconsin age-related maculopathy grading system. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1128–34. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32186-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klein R, Davis MD, Magli YL, et al. The Wisconsin Age-Related Maculopathy Grading System. Springfield, VA: National Technical Information Service; 1991. Accession No. PB91–184267. Ref Type: Report. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klein R, Klein BE, Jensen SC, Meuer SM. The five-year incidence and progression of age-related maculopathy: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:7–21. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30368-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klein R, Meuer SM, Myers CE, et al. Harmonizing the classification of age-related macular degeneration in the three-continent AMD consortium. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2014;21:14–23. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2013.867512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackson CH. Multi-state models for panel data: the msm package for R. J Stat Softw. 2011;38:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 32.DeAngelis MM, Ji F, Kim IK, et al. Cigarette smoking, CFH, APOE, ELOVL4, and risk of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:49–54. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ryu E, Fridley BL, Tosakulwong N, et al. Genome-wide association analyses of genetic, phenotypic, and environmental risks in the age-related eye disease study. Mol Vis. 2010;16:2811–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scott WK, Schmidt S, Hauser MA, et al. Independent effects of complement factor H Y402H polymorphism and cigarette smoking on risk of age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1151–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seddon JM, George S, Rosner B, Klein ML. CFH gene variant, Y402H, and smoking, body mass index, environmental associations with advanced age-related macular degeneration. Hum Hered. 2006;61:157–65. doi: 10.1159/000094141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sofat R, Casas JP, Webster AR, et al. Complement factor H genetic variant and age-related macular degeneration: effect size, modifiers and relationship to disease subtype. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:250–62. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baird PN, Robman LD, Richardson AJ, et al. Gene-environment interaction in progression of AMD: the CFH gene, smoking and exposure to chronic infection. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1299–305. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sepp T, Khan JC, Thurlby DA, et al. Complement factor H variant Y402H is a major risk determinant for geographic atrophy and choroidal neovascularization in smokers and nonsmokers. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:536–40. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang JJ, Rochtchina E, Smith W, et al. Combined effects of complement factor H genotypes, fish consumption, and inflammatory markers on long-term risk for age-related macular degeneration in a cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:633–41. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmidt S, Hauser MA, Scott WK, et al. Cigarette smoking strongly modifies the association of LOC387715 and age-related macular degeneration. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:852–64. doi: 10.1086/503822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang JJ, Ross RJ, Tuo J, et al. The LOC387715 polymorphism, inflammatory markers, smoking, and age-related macular degeneration. A population-based case-control study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:693–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.