Abstract

Many of our insights into obesity and diabetes come from studies in mice carrying natural or induced mutations. In parallel, genome-wide association studies in humans have identified numerous genes that are causally associated with obesity and diabetes, but discovering the underlying mechanisms required in-depth studies in mice. We discuss the advantages of studying natural variation in mice and summarize several examples where the combination of human and mouse genetics opened windows into fundamental physiological pathways. A noteworthy example is the melanocortin-4 receptor and its role in energy balance. The pathway was delineated by discovering the gene responsible for the Agouti mutation in mice. With more targeted phenotyping, we predict that additional pathways relevant to human pathophysiology will discovered.

Keywords: diabetes, obesity, mouse genetics, human genetics, complex traits, gene mapping, GWAS

Genetic Diversity of Mice

Inbred mouse strains have been maintained for nearly a century, beginning with the systematic collection of mice belonging to collectors in Europe, Asia, and North America. Inbreeding of the various strains produced reference populations, many of which have become important animal models for disease-related research.

The majority of the inbred strains are derived from Mus musculus (M. m) and belong to one of three subspecies, M. m. domesticus, M. m musculus, and M. m castaneus. Cross breeding between M. m. musculus and M. m. castaneus produced the Mus musculus molossinus subspecies (1). Because of the extensive introgression of genomic regions between the various subspecies, different parts of the genome will exhibit different phylogenetic relationships between strains. Thus, it is most useful to examine these relationships by focusing on discrete regions of the genome, which can be done with the web-based Mouse Phylogeny Viewer (http://msub.csbio.unc.edu/).

Extensive phenotyping of inbred strains has shown that for most phenotypes, there is extensive diversity across mouse strains. A measure of genetic diversity is the number of SNPs in a given population. In the entire human population, there are approximately 40 million single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Coincidentally, across the inbred mouse strains there are also approximately 40 million SNPs.

By selecting comparison groups that display strong phenotype contrast, mechanistic studies can be performed focusing on specific tissues and biological pathways. In many cases, a full-blown disease is not necessary to obtain useful results; all that is needed is genetically-controlled phenotype differences. The Jackson Laboratory curates a web site that displays many hundreds of phenotypes corresponding to each individual mouse strain (http://phenome.jax.org/).

The many inbred mouse strains maintained at the Jackson Laboratory have been extensively studied in relation to a multitude of human diseases. The strains differ in their susceptibility to diet induced obesity and to obesity-induced type 2 diabetes (T2D) allowing genetic mapping of quantitative and qualitative trait loci controlling these differences. The characteristics of the strains in relation to T2D has been previously reviewed (2). The C57BL/6 strain is the most widely used reference strain in diabetes research. It is commonly referred as the “diabetes resistant” strain. However, depending on the strain it is compared to, it displays both protective and diabetes susceptibility phenotypes. With high fat diet feeding, C57BL/6 mice are susceptible to diet-induced obesity, insulin resistance and hyperglycemia whereas the A/J mouse remains lean and insulin-sensitive (3, 4).

Experimental approaches

We will very briefly describe some of the experimental approaches to gene discovery in mice, pointing out some of the advantages of particular experimental designs. More detailed descriptions have been published elsewhere (2, 5-8).

The most widely-used method for gene discovery is a linkage study, typically an F2 intercross. Two strains with contrasting phenotypes are bred for two generations. Through meiotic recombination, the F2 mice inherit recombinant chromosomes with segments derived from either parental strain. Each F2 is unique and must be genotyped at polymorphic markers across the genome in order to analyze the relationship between SNP genotypes and phenotypes. There are four main disadvantages to this approach: 1) mapping resolution is poor because on average, each mouse only accumulates two recombinations per chromosome; 2) limited genetic space; only two alleles are compared and in large areas of the genome that are identical by descent, no genotypic variation occurs; 3) each F2 animal is unique, so there cannot be biological replication; 4) homozygous inbred strains have eliminated many of the most deleterious alleles because they are lethal when homozygous.

Chromosome substitution strains (aka consomic strains) have been derived in mice and rats (9). When a phenotype is linked to a substituted chromosome, the chromosome can then be systematically dissected by deriving congenic strains with introgressed regions corresponding to segments of the chromosome. Even before an individual gene beneath a QTL is identified, the congenic strains are valuable animal models representing allelic variants. An example is a study that identified a gene-by-diet effect on hepatic steatosis and hepatocellular carcinoma linked to mouse chromosome 17 (10, 11).

One approach to improve mapping resolution is to use outbred stocks of mice or rats, while performing an association study similar to genome-wide association studies (GWAS) performed in human populations. This can be done with free-living wild caught mice, but the environmental variation can compromise the experiments. Alternatively, several stocks of mice and rats have been created and maintained (12-14). They have accumulated hundreds of recombinations and thus provide high mapping resolution (6). One resource is the diversity outcross which was derived from the eight founder strains of the Collaborative Cross project (13). This resource includes three wild-derived strains and thus contains high genetic diversity; 3-7 alleles per locus. Valdar et al 2006 performed GWAS analysis in outbred strains and mapped 843 QTLs with an average 95% confidence interval of 2.8 Mb (15). The QTLs contribute to variation in more than 90 traits including obesity and T2D however molecular characterization of the many small-effect QTLs identified remains an important challenge. Zhang et al recently carried out GWAS using 288 mice from a commercially available outbred stock to map loci influencing HDL cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, TG levels, glucose, and urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratios. They found significant associations with HDL cholesterol and identified Apoa2 and Scarb1, both of which have been previously reported, as candidate genes for these associations (16). These findings highlight the need for outbred populations with greater genetic diversity as in the case for the DO strains. More recently, in an outbred rat stock, Baud et al. identified 35 specific genes responsible for 31 different phenotypes, mostly hematological (17).

Recombinant inbred (RI) strains are obtained from brother-sister mating of mice (beginning at the F2 generation, typically from two founder strains). These mice need to be genotyped just once. A hybrid approach of phenotyping RI strains and inbred strains, the hybrid mouse diversity panel (HMDP) has identified many QTLs and a good number of candidate genes (18).

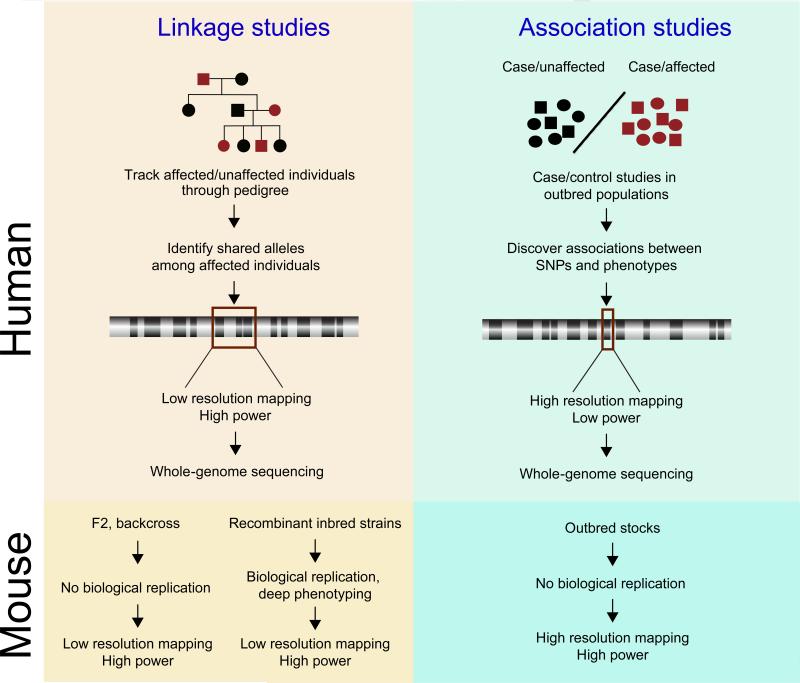

When comparing linkage and association studies, there appears to be a trade-off between power and resolution (Figure 1). Linkage studies have high power and low resolution. Conversely, association studies, while often having very high resolution, suffer from low power; in human GWAS the commonly accepted threshold for genome-wide significance is a nominal p-value of 5 × 10-8. This is due to the large multiple testing penalty that comes with interrogating millions of SNPs.

Figure 1. Linkage and association studies in mouse and human genetics.

A) Human. In linkage studies, families with affected individuals are selected. SNP genotyping is performed to identify allele sharing between affected individuals. This approach has high statistical power, but phenotypes typically map to broad chromosomal regions harboring many genes. In association studies, one looks for association between SNP genotypes and phenotypes across an outbred population. Because these populations segregate smaller genomic regions, the mapping resolution is much higher than is seen in linkage studies. However, the requirement to score large numbers of SNPs and ensuing multiple testing penalty results in lower statistical power. B) Mouse. Intercrosses between inbred mouse strains are analogous to family-based linkage studies in humans. Like human linkage studies, mouse intercrosses have high statistical power have low mapping resolution. Association studies in outbred stocks are analogous to human genome-wide association studies. These studies have much higher resolution than linkage studies. They require fewer SNPs to achieve high coverage and therefore have relatively high statistical power.

Why do genetics?

The simplest rationale for “doing genetics” is that it offers an undeniable causal connection between a gene locus and a phenotype. The search for this connection does not require a hypothesis or even prior understanding of the biological pathway that connects phenotype and gene. Many surprises have emerged where gene loci not previously associated with a particular human disease have shown strong associations with disease. Examples from human GWAS or linkage studies are: TSF7L2 and type 2 diabetes (19), SORT1 and LDL cholesterol (20), a locus near the FTO gene and obesity (21), PNPLA3 for hepatic steatosis (22), and PCSK9 for autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia (23).

Much has been gained from the study of transgenic mouse models where genes have been overexpressed or deleted. However, natural allelic variants can offer mechanistic insights that would not otherwise be obtained from null alleles. For example, the classic work of Brown and Goldstein on hundreds of loss-of-function LDL receptor variants enabled them to discover fundamental mechanisms underlying receptor trafficking through the secretory pathway and endocytosis (24).

A less obvious reason to do genetic screens is to develop causal network models of disease (25). This is based on the premise that phenotypes that map to the same locus have a much higher probability of being causally linked than phenotypes that are merely correlated. This concept follows from the fact that the relationship between genotype and phenotype follows a one-way line of causality while correlated phenotypes can be connected by any direction or indirectly. Genetics-based causal models have yielded novel connections to atherosclerosis, obesity, and diabetes (25).

A valuable resource for screening allelic variants in the mouse is a sperm bank from N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) -mutagenized mice, maintained by the Harwell Genetics Unit. The samples were generated by treatment of male mice with a small dose of ENU, alkylating agent, which produces point mutations in male mouse spermatogonial stem cells from which mature sperm are derived. This bank was successfully screened for novel mutations in the Nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase gene (discussed below;(26).

Physiological insights gained from mouse obesity and diabetes genes

Obese models of type 2 diabetes

Since type 2 diabetes is closely linked to obesity, most of the animal models of type 2 diabetes are obese. The obesity could be due to spontaneously occurring mutations or genetic manipulations. The Lepob/ob, LepRdb/db and Ay/a mice are the three most commonly used spontaneously obese monogenic mouse models. They display insulin resistance and can develop diabetes, depending on the background strain (Table 1).

Table 1.

Spontaneous mouse models of obesity.

| Model | Mutation | Phenotype | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monogenic mouse models | Lepob/ob | Lacks leptin | Severe obesity, hyperinsulinemic, hyperglycemic, hyperlipidemic, infertile. Develop diabetes depending on the background strain. | (27) (98) |

| Leprdb/db | Lacks Leptin receptor | Hyperphagic, obese, hyperinsulinemic and hyperglycemic. Develop diabetes depending on the background strain. | (28), (99) | |

| Agoutiy/a | Lacks Raly gene | Adult onset obesity, hypertension and insulin resistance due to hyperphagia and hypoactivity. fertile until about 4 months of age | (100) | |

| Polygenic mouse models | KK | Mildly obese, hyperleptinemia, hyperinsulinemia followed by beta-cell failure (degranulation) and diabetes. | (107), (108) | |

| NZO | Hyperphagic, obese, hyperleptinemia. | (101) | ||

| Peripheral leptin resistance. | (102) | |||

| Hyperinsulinemic due to impaired regulation of FBPase. | (103) | |||

| Impaired glucose tolerance, hyperglycemia, beta-cell loss. | (104) | |||

| TallyHo/Jng | Obese, hyperglycemic, Hyperinsulinemic. Degranulates pancreatic beta-cells. | (105, 106) |

Leptin, the first adipokine

The leptin gene was one of the great earliest triumphs of mouse genetics. The Ob mutation arose spontaneously at the Jackson Laboratory in 1949, producing a mouse with morbid recessive monogenic obesity (27). Fifteen years later, another mutation Db, was found that phenocopies Ob (28). Douglas Coleman performed parabiosis experiments by connecting the circulatory systems of Ob and Db mice (29). The Ob mice lost weight and starved to death. Coleman's prescient interpretation of these results was that the Ob mouse is missing a functional circulating factor that regulates food intake and that the Db mouse is missing a functional receptor for that factor. Through positional cloning, Jeff Friedman's laboratory identified the Leptin gene and its mutation in the Ob mouse and Tartaglia identified the leptin receptor gene and its mutation in several allelic variants of Db (30).

Leptin is primarily produced in adipose tissue, crosses the blood-brain barrier, and exerts its effects on food intake in the hypothalamus. However, leptin also regulates energy expenditure (31) and many metabolic and endocrine processes (e.g. lipogenesis, bone mineralization, puberty, kidney function). There are leptin receptors in many tissues that mediate direct effects on those tissues (e.g. suppression of insulin secretion in β-cells (32, 33)).

With the exception of a small number of families (34), leptin deficiency is not a cause of human obesity (35). However, obese humans tend to be leptin resistant and the physiology of leptin has provided many valuable insights into the causes and treatment of human obesity (31).

Congenital lipodystrophy syndromes often lead to insulin resistance, hepatic steatosis and type 2 diabetes. These syndromes are associated with leptin deficiency (36). Many of the metabolic syndromes of lipodystrophy are caused by leptin deficiency and have been successfully treated with leptin injections, initially in mice (37), and then in humans (38). Studies by Unger have shown that leptin suppresses glucagon secretion and thus leptin administration can normalize blood glucose in mouse models of type 1 diabetes (39). It remains to be determined whether or not this therapy is effective in humans.

Diabetes in response to leptin deficiency depends on mouse strain background. This was originally observed by Coleman in a comparison of the C57BL/6 mouse strain with a closely related strain, C57BL/Ks, where the latter strain exhibited diabetes susceptibility (40). This observation had a profound influence on mouse genetics by demonstrating that obesity effects on diabetes are conditional on defects in other pathways. It inspired mouse geneticists to conduct genetic screens for diabetes promoting modifiers of the obesity phenotype. Much of the evidence now indicates that these other pathways primarily affect β-cell biology (reviewed in (41).

The discovery of leptin redefined our view of adipose tissue as an endocrine organ rather than merely a site for fat storage. Numerous additional hormones, termed adipokines have since been discovered. They regulate whole-body insulin action, inflammation, and many metabolic processes (42).

Agouti and the discovery of the MC4R pathway

Mice with the agouti lethal yellow (Ay) allele, first described in 1905, have a yellow (instead of black) fur color and are obese. These phenotypes are dominant. All of the obesity-inducing Agouti alleles are expressed from an alternative promoter, leading to ubiquitous expression. The Ay mutation is caused by a deletion upstream of the Agouti that places it next to the ubiquitously expressed Raly gene (43, 44). In the skin, the Agouti protein antagonizes the signaling of αMSH via the melanocortin-1 receptor, which normally promotes the production of eumelanin by melanocytes and hence black skin. Blocking this pathway leads to production of pheomelanin and hence yellow skin. In the hypothalamus, Agouti blocks melanocortin-4 receptor pathway, resulting in changes in food intake and energy efficiency, leading to obesity (45). In normal animals, a different protein, agouti-related protein, is a natural antagonist of the MC4R pathway. Mutations in the MC4R pathway are the most common monogenic cause of obesity in humans (46); ~90 different mutations in MC4R cause morbid obesity.

Examples of polygenic spontaneous mouse models of obesity are also discussed in Table 1.

Examples of type 2 diabetes related genes identified through positional cloning in mice

Mouse genetics has contributed to identification of several type 2 diabetes associated genes. Below we discuss examples of genes identified through positional cloning.

Lipin

The original Lipin gene was identified through positional cloning, using a naturally-occurring mutation in the BALBc/ByJ mouse strain causing lipodystrophy and defects in lipid metabolism (47). The genes for lipin-1, lipin-2 and lipin-3 are expressed in adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, and liver. Purification of a phosphatidate phosphohydrolase in yeast led to the discovery that Lipin is a homolog of the yeast enzyme and possesses the same enzymatic activity, placing it within the glycerolipid biosynthetic pathway (48). Lipin also functions as a transcriptional co-activator of PGC-1α, which activates PPARα in response to fasting (49) and leads to increased expression of fatty acid oxidizing genes such as carnitine palmitoyl transferase-1, acyl CoA oxidase, and medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase. There are two other Lipin genes, which have the same enzymatic activity as Lipin 1. Polymorphisms in LIPIN genes are associated with a range of phenotypes, including type 2 diabetes, low blood pressure, myoglobinuria and response to thiazolidinedione drugs (reviewed in (50). Several studies have shown that lipin-1 expression is correlated with Glut4 expression (51-53)), providing a reasonable mechanism for the relationship between thiazolidinediones (TZD), lipin-1 expression, and insulin sensitivity.

Zfp69

Zfp69 was positionally cloned using a population of inbred strains of mice (SJL, NON and NZB) outcrossed with the NZO strain, as the gene underlying an obesity-associated diabetes susceptibility locus on mouse chromosome 4 (54). First, in an F2 intercross between male NZO and F1 backcross between NZO and the atherosclerosis-resistant SJL strain, a locus for the development of mild hyperglycemia and hypoinsulinemia (Nidd/SJL) was identified. The glucose elevating allele was presumably contributed by the SJL allele. Second, the region of interest on chromosome 4 from SJL strain was intergressed into the diabetes resistant C57BL/6 background and the resulting mice were lean and normal. However, when the mice were made obese by subsequent crossing with the NZO strain, they developed fasting hyperglycemia and hypoinsulinemia. Sequence analysis of ten genes in the region revealed allelic variation of zinc finger domain transcription factor 69, (Zfp69). Zfp69 encodes a transcription factor that regulates lipid storage in adipose tissue, and thereby enhances lipid deposition in the liver.

Interestingly, the diabetes resistant C57BL/6 and NZO strains express truncated Zfp69 mRNA, which lacks both the N-terminal KRAB and C-terminal zinc finger binding C2H2 domains. The diabetogenic strains SJL, NON and NZB however, express normal Zfp69 mRNA levels. As was the case for SJL, introgression of the NON and NZB alleles into diabetes resistant strains resulted in hyperglycemia. Therefore, loss of function of the Zfp69 gene suppresses diabetes and expression of the full length mRNA enhances obesity-induced diabetes. In agreement with these observations, mRNA expression of the human ZFP69 is enhanced in adipose tissues of type 2 diabetic subjects. We do not know of any gene that causes glucose to increase solely through an action in adipose tissue. Thus, it will be interesting to explore the potential role of Zfp69 in pancreatic β-cells.

Sorcs1

Sorcs1 was positionally cloned in an F2 intercross between the diabetes-susceptible BTBR and the diabetes-resistant C57BL/6 strain (55). The Lepob mutation was introgressed into the intercross and the entire F2 population was Lepob/ob and thus segregated for alleles conferring diabetes susceptibility in the context of morbid obesity and leptin deficiency. Dissection with 11 congenic mouse strains achieved single-gene resolution (rare in mouse genetics) and identified Sorcs1 as the gene underlying a fasting insulin QTL on chromosome 19 (56). The region was syntenic with an insulin QTL identified in genetic studies of the GK rat (57).

Sorcs1 belongs to the vacuolar protein sorting 10 (vps10) family, homologous to a yeast protein that transports lysosomal enzymes to the lysosome (58). In mammals, Sorcs1 binds to platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), initially suggesting that Sorcs1 might affect islet vasculature. But, a PDGF-BB hypomorph, while affecting the permeability of many tissues (59), failed to affect islet vasculature (60).

The deletion of Sorcs1 in the C57BL/6 Lepob mouse led to diabetes and a severe depletion of insulin granules in pancreatic β-cells, suggesting that, like its ancestral homolog, Sorcs1 is involved in vesicular trafficking and perhaps in the biogenesis of insulin granules. Recent studies show that in protozoans, vps10 homologs are essential for the production and/or function of their secretory organelles (61, 62). Like insulin granules, these organelles engage the SNARE proteins and are triggered to fuse with the plasma membrane during exocytosis. Interestingly, lean mice deficient in Sorcs1 do not lose their insulin granules. Thus, the requirement for Sorcs1 seems to be invoked by obesity or leptin deficiency.

In human genetic studies, SORCS1 is associated with type 2 diabetes (63, 64), diabetes complications (65), and Alzheimer's Disease (66-69). The wide range of phenotypes resulting from this locus is likely a consequence of its involvement in a cellular process common to many physiological pathways. Important mechanistic insights will be obtained from discovering the precise steps in vesicle trafficking that are mediated by Sorcs1 and the cargo proteins whose transport depends on Sorcs1.

Tomosyn-2

In the BTBR/B6 F2 study, the strongest linkage for fasting serum glucose was on chromosome 16 (55). By dissection of the QTL region with congenic strains, Bhatnagar et al. narrowed the interval to a small number of genes and identified Stxbp5l, encoding Tomosyn-2 protein, as the strongest candidate (70). It is interesting that although the F2 genome scan showed no linkage for insulin, the strongest phenotype of the congenic strains was in islet glucose-induced insulin secretion, which was reduced by ~50%. This illustrates the point that physiological traits like serum insulin are a rather insensitive measure of critical physiological processes like insulin secretion.

Tomosyn-2 is homologous to Tomosyn-1 and both proteins are expressed in β-cells. But, the fact that allelic variation in Tomosyn-2 could lead to an insulin secretion phenotype suggests that they have non-overlapping functions. These proteins are negative regulators of exocytosis. This begs the question, how do β-cells lift the brake imposed by the Tomosyn proteins when they secrete insulin? Current studies are focusing on how nutrient sensing is linked to the negative control of Tomosyn-2.

Lisch-like

The Lisch-like (Ll) gene was positionally cloned in an ob/ob F2 intercross between C57BL/6J (B6) and the diabetes prone DBA/2J (DBA) strains (71) as a gene underlying a T2D locus on chromosome 1 and was shown to be involved in regulating β-cell mass and plasma glucose levels.

Ll is a novel gene expressed in hypothalamus, islets, liver and skeletal muscle and is believed to encode a transmembrane protein that could mediate pathways involved in cell division and affect β-cell mass. Mice with reduced LI expression have impaired β-cell development and glucose metabolism (71). Reduced expression of the homologous gene in zebrafish disrupts islet development (71). Interestingly the human ortholog of LI has been associated with T2D in several populations (72-77). The direct role of Ll on β-cell replication and function using KO mice has yet to be investigated.

Tbc1d1

QTL mapping through an intercross between the NZO and SJL strains identified a major locus for HFD-induced obesity on chromosome 5 (78-80). Fine mapping reduced the QTL interval to a block of approximately 8 Mb that included 19 protein-coding genes. The expression of Tbc1d1, one of the genes in the QTL peak region, was reduced by 70% in skeletal muscle of SJL mice. Sequencing of the Tbc1d1 gene revealed a 7-bp deletion in exon 18 only in the SJL strain, resulting in deletion of part of the functionally vital TBC-GAP domain, leading to loss of function mutation. Using a subcongenic line, which harbors approximately 10 Mb of the region from SJL on a C57BL/6J background, Chadt et al showed homozygous carriers of the SJL allele had lower body weight than control mice (81). Recently it was shown that mice homologous for the SJL allele displayed impaired insulin stimulated GLUT4 translocation in skeletal muscle (82). More recently TBC1D1 is also shown to be expressed in pancreatic β-cells where it is phosphorylated in response to glucose and plays a role in β-cell proliferation and insulin release (83).

Nnt

Using an F2 intercross derived from C57BL/6J and C3H/HeH mice Toye et al (84) identified Nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase (Nnt) as a type-2 diabetes gene that affects glucose tolerance and insulin secretion. The C57BL/6J strain carries two mutations: a missense mutation (M35T) within the mitochondrial leader sequence of the precursor protein and an in-frame 5-exon deletion that removes four transmembrane helices and their connecting linkers. It is ironic that in this case, a strain that is widely used as a reference strain is the mutant.

Nnt is an enzyme that pumps protons across the inner mitochondrial membrane catalyzing the reversible reduction of NADP+ by NADH and conversion of NADH to NAD+ therefore acting as an essential component of glucose-induced ATP production in pancreatic β-cells. Islets isolated from mice carrying mutations in Nnt have impaired ATP production, preventing closure of KATP channels in response to glucose, calcium influx, and insulin secretion. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) production is enhanced in Nnt mutant β-cells, suggesting a role for Nnt in ROS detoxification. Interestingly, a recent study identified a mutation in Nnt in individuals with familial glucocorticoid deficiency, which is thought to be associated with ROS detoxification in human adrenal glands (85).

Tsc2

Hepatic steatosis frequently occurs in people who are obese and diabetic. In mice, obesity is also often associated with hepatic steatosis, but at least in two mouse strains that develop diabetes when made obese, the BTBR and the DBA strains, the diabetes susceptibility correlates with a resistance to hepatic steatosis and is correlated with reduced hepatic lipogenesis (86-88). Mapping of hepatic triglyceride to a QTL on chromosome 17 in the C57BL/6 × BTBR F2 intercross identified Tsc2 as a highly plausible candidate gene for hepatic steatosis (87). Tsc2 encodes tuberin, a GTPase activating protein that activates Rheb, an activator of mTor. Since mTor stimulates both lipogenesis and cell growth, Tuberin acts as an inhibitor of both processes. Between the two mouse strains is a coding SNP, M552V. Functional studies showed that the C57BL/6 allele conferred a higher rate of lipogenesis and a greater ability to induce proliferation in a β-cell line. Since Tsc2 knockout mice have increased β-cell mass and hyperinsulinemia (89), these studies suggest that Tsc2 can simultaneously regulate hepatic lipogenesis and β-cell proliferation.

Txnip

Txnip was identified in an F2 intercross between CAST/Ei and a recombinant congenic strain, Hcb19, screening for hyperlipidemia (90). The Hcb19 mice have dramatically increased fasting triglycerides and ketone bodies. Fine mapping and sequencing identified a nonsense mutation in the thioredoxin interacting protein (Txnip) gene. Deletion of Txnip in muscle produced a severe defect in both glucose and fatty acid oxidation (91). Txnip is one of the most glucose inducible genes in β-cells (92) and muscle (93), through the carbohydrate response element binding protein. Its deletion rescues several type 2 diabetes mouse strains from diabetes, through an attenuation of apoptosis (94, 95). In the liver, loss of Txnip decreases hepatic glucose production (96).

In the brain, Txnip plays a critical role in the regulation of energy expenditure. Modulation of Txnip expression in AGRP-expressing neurons affects leptin sensitivity and adiposity, through an effect on energy expenditure rather than food intake (97).

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

The contribution of genetic variation to diabetes has been estimated to be approximately 50%. Yet, the sum of all discovered susceptibility loci does not come close to explaining the high heritability of diabetes. This has been attributed to complex gene-gene interactions and the inability to sample many rare alleles. The loci that have been discovered have very modest effects on disease risk; typical odds ratio <1.2. One potential problem is that the phenotyping that can be done in human subjects is limited and subject to a high level of environmental “noise”. Model organisms offer the opportunity for deeper phenotyping and more control over non-genetic sources of variation.

Mouse genetics has unveiled new areas of mammalian pathophysiology. In some cases (e.g. the melanocortin-4-receptor), variation in the genes that were identified contributes to human disease. But, more often, the identified genes do not have common variants contributing to human disease (e.g. leptin & lipin), but are important in human physiology. Hence, the goal of mouse genetics is to discover novel genes, pathways, and mechanisms, and not necessarily those that vary in the human population.

Genetic screens in intercrosses between inbred strains have been responsible for most of the discoveries from mouse genetics. These studies required years of work to narrow down the chromosomal positions of the genes mapped in the crosses. New resources are now available that obviate the need to improve mapping resolution, thus accelerating the path towards gene discovery. These include collections of recombinant inbred mouse strains (e.g. the Collaborative Cross and the HMDP collections) or outbred stocks of mice and rats. These resources explore a larger genetic space owing to the larger number of alleles represented.

Human genetic studies of diabetes confront several limitations when phenotyping consists of scoring the presence or absence of a disease. Unlike disorders that manifest throughout a lifetime (e.g. hyperlipidemia), diabetes typically occurs late in life. Since it is not possible to distinguish a non-diabetic from a not-yet diabetic subject, there are undoubtedly many false negatives. Phenotyping of intermediate traits (e.g. insulin secretion or insulin turnover) will likely identify new genes and pathways. Technological developments in proteomics, metabolomics, non-invasive imaging, and stable isotope tracer methods open the door to novel phenotyping approaches.

Highlights.

Many critically important physiological pathways related to energy metabolism and diabetes were discovered through mouse genetics.

Mouse strains and outbred stocks provide a repertoire of genetic diversity comparable to that of the entire human population.

Technological improvements, largely in –omics methods, together with robust physiological phenotyping will lead to the identification of new genes using newly available resources in mouse and rat genetics.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Yang H, Wang JR, Didion JP, Buus RJ, Bell TA, Welsh CE, Bonhomme F, Yu AH, Nachman MW, Pialek J, et al. Subspecific origin and haplotype diversity in the laboratory mouse. Nature genetics. 2011;43(7):648–55. doi: 10.1038/ng.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clee SM, Attie AD. The genetic landscape of type 2 diabetes in mice. Endocrine reviews. 2007;28(1):48–83. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Surwit RS, Feinglos MN, Rodin J, Sutherland A, Petro AE, Opara EC, Kuhn CM, Rebuffe-Scrive M. Differential effects of fat and sucrose on the development of obesity and diabetes in C57BL/6J and A/J mice. Metabolism: clinical and experimental. 1995;44(5):645–51. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(95)90123-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Surwit RS, Kuhn CM, Cochrane C, McCubbin JA, Feinglos MN. Diet-induced type II diabetes in C57BL/6J mice. Diabetes. 1988;37(9):1163–7. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.9.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mott R, Flint J. Dissecting Quantitative Traits in Mice. Annual review of genomics and human genetics. 2013;14(1):421–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-091212-153419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flint J, Eskin E. Genome-wide association studies in mice. Nature reviews Genetics. 2012;13(11):807–17. doi: 10.1038/nrg3335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Civelek M, Lusis AJ. Systems genetics approaches to understand complex traits. Nature reviews Genetics. 2014;15(1):34–48. doi: 10.1038/nrg3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nadeau JH, Forejt J, Takada T, Shiroishi T. Chromosome substitution strains: gene discovery, functional analysis, and systems studies. Mammalian genome : official journal of the International Mammalian Genome Society. 2012;23(9-10):693–705. doi: 10.1007/s00335-012-9426-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singer JB, Hill AE, Burrage LC, Olszens KR, Song J, Justice M, O'Brien WE, Conti DV, Witte JS, Lander ES, et al. Genetic dissection of complex traits with chromosome substitution strains of mice. Science. 2004;304(5669):445–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1093139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill-Baskin AE, Markiewski MM, Buchner DA, Shao H, DeSantis D, Hsiao G, Subramaniam S, Berger NA, Croniger C, Lambris JD, et al. Diet-induced hepatocellular carcinoma in genetically predisposed mice. Human molecular genetics. 2009;18(16):2975–88. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Millward CA, Burrage LC, Shao H, Sinasac DS, Kawasoe JH, Hill-Baskin AE, Ernest SR, Gornicka A, Hsieh CW, Pisano S, et al. Genetic factors for resistance to diet-induced obesity and associated metabolic traits on mouse chromosome 17. Mammalian genome : official journal of the International Mammalian Genome Society. 2009;20(2):71–82. doi: 10.1007/s00335-008-9165-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valdar W, Solberg LC, Gauguier D, Burnett S, Klenerman P, Cookson WO, Taylor MS, Rawlins JNP, Mott R, Flint J. Genome-wide genetic association of complex traits in heterogeneous stock mice. Nature genetics. 2006;38(8):879–87. doi: 10.1038/ng1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Svenson KL, Gatti DM, Valdar W, Welsh CE, Cheng R, Chesler EJ, Palmer AA, McMillan L, Churchill GA. High-resolution genetic mapping using the Mouse Diversity outbred population. Genetics. 2012;190(2):437–47. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.132597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yalcin B, Nicod J, Bhomra A, Davidson S, Cleak J, Farinelli L, Osteras M, Whitley A, Yuan W, Gan X, et al. Commercially available outbred mice for genome-wide association studies. PLoS genetics. 2010;6(9):e1001085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valdar W, Solberg LC, Gauguier D, Burnett S, Klenerman P, Cookson WO, Taylor MS, Rawlins JN, Mott R, Flint J. Genome-wide genetic association of complex traits in heterogeneous stock mice. Nature genetics. 2006;38(8):879–87. doi: 10.1038/ng1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang W, Korstanje R, Thaisz J, Staedtler F, Harttman N, Xu L, Feng M, Yanas L, Yang H, Valdar W, et al. Genome-wide association mapping of quantitative traits in outbred mice. G3. 2012;2(2):167–74. doi: 10.1534/g3.111.001792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rat Genome S, Mapping C, Baud A, Hermsen R, Guryev V, Stridh P, Graham D, McBride MW, Foroud T, Calderari S, et al. Combined sequence-based and genetic mapping analysis of complex traits in outbred rats. Nature genetics. 2013;45(7):767–75. doi: 10.1038/ng.2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghazalpour A, Rau CD, Farber CR, Bennett BJ, Orozco LD, van Nas A, Pan C, Allayee H, Beaven SW, Civelek M, et al. Hybrid mouse diversity panel: a panel of inbred mouse strains suitable for analysis of complex genetic traits. Mammalian genome : official journal of the International Mammalian Genome Society. 2012;23(9-10):680–92. doi: 10.1007/s00335-012-9411-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grant SF, Thorleifsson G, Reynisdottir I, Benediktsson R, Manolescu A, Sainz J, Helgason A, Stefansson H, Emilsson V, Helgadottir A, et al. Variant of transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) gene confers risk of type 2 diabetes. Nature genetics. 2006;38(3):320–3. doi: 10.1038/ng1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Musunuru K, Strong A, Frank-Kamenetsky M, Lee NE, Ahfeldt T, Sachs KV, Li X, Li H, Kuperwasser N, Ruda VM, et al. From noncoding variant to phenotype via SORT1 at the 1p13 cholesterol locus. Nature. 2010;466(7307):714–9. doi: 10.1038/nature09266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frayling TM, Timpson NJ, Weedon MN, Zeggini E, Freathy RM, Lindgren CM, Perry JR, Elliott KS, Lango H, Rayner NW, et al. A common variant in the FTO gene is associated with body mass index and predisposes to childhood and adult obesity. Science. 2007;316(5826):889–94. doi: 10.1126/science.1141634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Romeo S, Kozlitina J, Xing C, Pertsemlidis A, Cox D, Pennacchio LA, Boerwinkle E, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nature genetics. 2008;40(12):1461–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abifadel M, Varret M, Rabes JP, Allard D, Ouguerram K, Devillers M, Cruaud C, Benjannet S, Wickham L, Erlich D, et al. Mutations in PCSK9 cause autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia. Nature genetics. 2003;34(2):154–6. doi: 10.1038/ng1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldstein JL, Brown MS. The LDL receptor. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2009;29(4):431–8. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.179564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schadt EE. Molecular networks as sensors and drivers of common human diseases. Nature. 2009;461(7261):218–23. doi: 10.1038/nature08454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freeman H, Shimomura K, Horner E, Cox RD, Ashcroft FM. Nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase: a key role in insulin secretion. Cell Metab. 2006;3(1):35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ingalls AM, Dickie MM, Snell GD. Obese, a new mutation in the house mouse. The Journal of heredity. 1950;41(12):317–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a106073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hummel KP, Dickie MM, Coleman DL. Diabetes, a new mutation in the mouse. Science. 1966;153(3740):1127–8. doi: 10.1126/science.153.3740.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coleman DL. Effects of parabiosis of obese with diabetes and normal mice. Diabetologia. 1973;9(4):294–8. doi: 10.1007/BF01221857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tartaglia LA, Dembski M, Weng X, Deng N, Culpepper J, Devos R, Richards GJ, Campfield LA, Clark FT, Deeds J, et al. Identification and expression cloning of a leptin receptor, OB-R. Cell. 1995;83(7):1263–71. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90151-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farooqi IS, O'Rahilly S. Leptin: a pivotal regulator of human energy homeostasis. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2009;89(3):980S–4S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26788C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Covey SD, Wideman RD, McDonald C, Unniappan S, Huynh F, Asadi A, Speck M, Webber T, Chua SC, Kieffer TJ. The pancreatic beta cell is a key site for mediating the effects of leptin on glucose homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2006;4(4):291–302. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morioka T, Asilmaz E, Hu J, Dishinger JF, Kurpad AJ, Elias CF, Li H, Elmquist JK, Kennedy RT, Kulkarni RN. Disruption of leptin receptor expression in the pancreas directly affects beta cell growth and function in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007;117(10):2860–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI30910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montague CT, Farooqi IS, Whitehead JP, Soos MA, Rau H, Wareham NJ, Sewter CP, Digby JE, Mohammed SN, Hurst JA, et al. Congenital leptin deficiency is associated with severe early-onset obesity in humans. Nature. 1997;387(6636):903–8. doi: 10.1038/43185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwartz MW, Porte D., Jr. Diabetes, obesity, and the brain. Science. 2005;307(5708):375–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1104344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hegele RA, Cao H, Huff MW, Anderson CM. LMNA R482Q mutation in partial lipodystrophy associated with reduced plasma leptin concentration. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2000;85(9):3089–93. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.9.6768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimomura I, Hammer RE, Ikemoto S, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Leptin reverses insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus in mice with congenital lipodystrophy. Nature. 1999;401(6748):73–6. doi: 10.1038/43448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petersen KF, Oral EA, Dufour S, Befroy D, Ariyan C, Yu C, Cline GW, DePaoli AM, Taylor SI, Gorden P, et al. Leptin reverses insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis in patients with severe lipodystrophy. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2002;109(10):1345–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI15001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang MY, Chen L, Clark GO, Lee Y, Stevens RD, Ilkayeva OR, Wenner BR, Bain JR, Charron MJ, Newgard CB, et al. Leptin therapy in insulin-deficient type I diabetes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(11):4813–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909422107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coleman DL, Hummel KP. The influence of genetic background on the expression of the obese (Ob) gene in the mouse. Diabetologia. 1973;9(4):287–93. doi: 10.1007/BF01221856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Florez JC. Newly identified loci highlight beta cell dysfunction as a key cause of type 2 diabetes: where are the insulin resistance genes? Diabetologia. 2008;51(7):1100–10. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deng Y, Scherer PE. Adipokines as novel biomarkers and regulators of the metabolic syndrome. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1212:E1–E19. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05875.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller MW, Duhl DM, Vrieling H, Cordes SP, Ollmann MM, Winkes BM, Barsh GS. Cloning of the mouse agouti gene predicts a secreted protein ubiquitously expressed in mice carrying the lethal yellow mutation. Genes & development. 1993;7(3):454–67. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.3.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Michaud EJ, Bultman SJ, Stubbs LJ, Woychik RP. The embryonic lethality of homozygous lethal yellow mice (Ay/Ay) is associated with the disruption of a novel RNA-binding protein. Genes & development. 1993;7(7A):1203–13. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7a.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lu D, Willard D, Patel IR, Kadwell S, Overton L, Kost T, Luther M, Chen W, Woychik RP, Wilkison WO, et al. Agouti protein is an antagonist of the melanocyte-stimulating-hormone receptor. Nature. 1994;371(6500):799–802. doi: 10.1038/371799a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Farooqi IS, Yeo GS, Keogh JM, Aminian S, Jebb SA, Butler G, Cheetham T, O'Rahilly S. Dominant and recessive inheritance of morbid obesity associated with melanocortin 4 receptor deficiency. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2000;106(2):271–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI9397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peterfy M, Phan J, Xu P, Reue K. Lipodystrophy in the fld mouse results from mutation of a new gene encoding a nuclear protein, lipin. Nature genetics. 2001;27(1):121–4. doi: 10.1038/83685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Han GS, Wu WI, Carman GM. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Lipin homolog is a Mg2+-dependent phosphatidate phosphatase enzyme. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281(14):9210–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600425200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Finck BN, Gropler MC, Chen Z, Leone TC, Croce MA, Harris TE, Lawrence JC, Jr., Kelly DP. Lipin 1 is an inducible amplifier of the hepatic PGC-1alpha/PPARalpha regulatory pathway. Cell Metab. 2006;4(3):199–210. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Csaki LS, Reue K. Lipins: multifunctional lipid metabolism proteins. Annual review of nutrition. 2010;30:257–72. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.012809.104729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mlinar B, Pfeifer M, Vrtacnik-Bokal E, Jensterle M, Marc J. Decreased lipin 1 beta expression in visceral adipose tissue is associated with insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome. European journal of endocrinology / European Federation of Endocrine Societies. 2008;159(6):833–9. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koh YK, Lee MY, Kim JW, Kim M, Moon JS, Lee YJ, Ahn YH, Kim KS. Lipin1 is a key factor for the maturation and maintenance of adipocytes in the regulatory network with CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma 2. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283(50):34896–906. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804007200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Harmelen V, Ryden M, Sjolin E, Hoffstedt J. A role of lipin in human obesity and insulin resistance: relation to adipocyte glucose transport and GLUT4 expression. Journal of lipid research. 2007;48(1):201–6. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600272-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scherneck S, Nestler M, Vogel H, Blüher M, Block M-D, Diaz MB, Herzig S, Schulz N, Teichert M, Tischer S, et al. Positional Cloning of Zinc Finger Domain Transcription Factor Zfp69, a Candidate Gene for Obesity-Associated Diabetes Contributed by Mouse Locus Nidd/SJL. PLoS genetics. 2009;5(7):e1000541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stoehr JP, Nadler ST, Schueler KL, Rabaglia ME, Yandell BS, Metz SA, Attie AD. Genetic obesity unmasks nonlinear interactions between murine type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci. Diabetes. 2000;49(11):1946–54. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.11.1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clee SM, Yandell BS, Schueler KM, Rabaglia ME, Richards OC, Raines SM, Kabara EA, Klass DM, Mui ET, Stapleton DS, et al. Positional cloning of Sorcs1, a type 2 diabetes quantitative trait locus. Nature genetics. 2006;38(6):688–93. doi: 10.1038/ng1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Granhall C, Park HB, Fakhrai-Rad H, Luthman H. High-resolution quantitative trait locus analysis reveals multiple diabetes susceptibility loci mapped to intervals<800 kb in the species-conserved Niddm1i of the GK rat. Genetics. 2006;174(3):1565–72. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.062208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bankaitis VA, Johnson LM, Emr SD. Isolation of yeast mutants defective in protein targeting to the vacuole. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1986;83(23):9075–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.23.9075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Armulik A, Genove G, Mae M, Nisancioglu MH, Wallgard E, Niaudet C, He L, Norlin J, Lindblom P, Strittmatter K, et al. Pericytes regulate the blood-brain barrier. Nature. 2010;468(7323):557–61. doi: 10.1038/nature09522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Raines SM, Richards OC, Schneider LR, Schueler KL, Rabaglia ME, Oler AT, Stapleton DS, Genove G, Dawson JA, Betsholtz C, et al. Loss of PDGF-B activity increases hepatic vascular permeability and enhances insulin sensitivity. American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism. 2011;301(3):E517–26. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00241.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sloves PJ, Delhaye S, Mouveaux T, Werkmeister E, Slomianny C, Hovasse A, Dilezitoko Alayi T, Callebaut I, Gaji RY, Schaeffer-Reiss C, et al. Toxoplasma sortilin-like receptor regulates protein transport and is essential for apical secretory organelle biogenesis and host infection. Cell host & microbe. 2012;11(5):515–27. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Briguglio JSK, S.'Turkewitz AP. Lysosomal sorting receptors are essential for desnse core vesicle biogenesis in Tetrahymena. J Cell Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1083/jcb.201305086. in revision. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Goodarzi MO, Lehman DM, Taylor KD, Guo X, Cui J, Quinones MJ, Clee SM, Yandell BS, Blangero J, Hsueh WA, et al. SORCS1: a novel human type 2 diabetes susceptibility gene suggested by the mouse. Diabetes. 2007;56(7):1922–9. doi: 10.2337/db06-1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Florez JC, Manning AK, Dupuis J, McAteer J, Irenze K, Gianniny L, Mirel DB, Fox CS, Cupples LA, Meigs JB. A 100K genome-wide association scan for diabetes and related traits in the Framingham Heart Study: replication and integration with other genome-wide datasets. Diabetes. 2007;56(12):3063–74. doi: 10.2337/db07-0451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Paterson AD, Waggott D, Boright AP, Hosseini SM, Shen E, Sylvestre MP, Wong I, Bharaj B, Cleary PA, Lachin JM, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies a novel major locus for glycemic control in type 1 diabetes, as measured by both A1C and glucose. Diabetes. 2010;59(2):539–49. doi: 10.2337/db09-0653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xu W, Xu J, Wang Y, Tang H, Deng Y, Ren R, Wang G, Niu W, Ma J, Wu Y, et al. The genetic variation of SORCS1 is associated with late-onset Alzheimer's disease in Chinese Han population. PloS one. 2013;8(5):e63621. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lane RF, Steele JW, Cai D, Ehrlich ME, Attie AD, Gandy S. Protein sorting motifs in the cytoplasmic tail of SorCS1 control generation of Alzheimer's amyloid-beta peptide. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2013;33(16):7099–107. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5270-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang HF, Yu JT, Zhang W, Wang W, Liu QY, Ma XY, Ding HM, Tan L. SORCS1 and APOE polymorphisms interact to confer risk for late-onset Alzheimer's disease in a Northern Han Chinese population. Brain research. 2012;1448:111–6. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.01.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reitz C, Tokuhiro S, Clark LN, Conrad C, Vonsattel JP, Hazrati LN, Palotas A, Lantigua R, Medrano M, I ZJ-V, et al. SORCS1 alters amyloid precursor protein processing and variants may increase Alzheimer's disease risk. Ann Neurol. 2011;69(1):47–64. doi: 10.1002/ana.22308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bhatnagar S, Oler AT, Rabaglia ME, Stapleton DS, Schueler KL, Truchan NA, Worzella SL, Stoehr JP, Clee SM, Yandell BS, et al. Positional cloning of a type 2 diabetes quantitative trait locus; tomosyn-2, a negative regulator of insulin secretion. PLoS genetics. 2011;7(10):e1002323. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dokmanovic-Chouinard M, Chung WK, Chevre J-C, Watson E, Yonan J, Wiegand B, Bromberg Y, Wakae N, Wright CV, Overton J, et al. Positional Cloning of “Lisch-like”, a Candidate Modifier of Susceptibility to Type 2 Diabetes in Mice. PLoS genetics. 2008;4(7):e1000137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xiang K, Wang Y, Zheng T, Jia W, Li J, Chen L, Shen K, Wu S, Lin X, Zhang G, et al. Genome-wide search for type 2 diabetes/impaired glucose homeostasis susceptibility genes in the Chinese: significant linkage to chromosome 6q21-q23 and chromosome 1q21-q24. Diabetes. 2004;53(1):228–34. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.1.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hsueh WC, St Jean PL, Mitchell BD, Pollin TI, Knowler WC, Ehm MG, Bell CJ, Sakul H, Wagner MJ, Burns DK, et al. Genome-wide and fine-mapping linkage studies of type 2 diabetes and glucose traits in the Old Order Amish: evidence for a new diabetes locus on chromosome 14q11 and confirmation of a locus on chromosome 1q21-q24. Diabetes. 2003;52(2):550–7. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Elbein SC, Hoffman MD, Teng K, Leppert MF, Hasstedt SJ. A genome-wide search for type 2 diabetes susceptibility genes in Utah Caucasians. Diabetes. 1999;48(5):1175–82. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.5.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vionnet N, Hani EH, Dupont S, Gallina S, Francke S, Dotte S, De Matos F, Durand E, Lepretre F, Lecoeur C, et al. Genomewide search for type 2 diabetes-susceptibility genes in French whites: evidence for a novel susceptibility locus for early-onset diabetes on chromosome 3q27-qter and independent replication of a type 2-diabetes locus on chromosome 1q21-q24. American journal of human genetics. 2000;67(6):1470–80. doi: 10.1086/316887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wiltshire S, Hattersley AT, Hitman GA, Walker M, Levy JC, Sampson M, O'Rahilly S, Frayling TM, Bell JI, Lathrop GM, et al. A genomewide scan for loci predisposing to type 2 diabetes in a U.K. population (the Diabetes UK Warren 2 Repository): analysis of 573 pedigrees provides independent replication of a susceptibility locus on chromosome 1q. American journal of human genetics. 2001;69(3):553–69. doi: 10.1086/323249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Meigs JB, Panhuysen CI, Myers RH, Wilson PW, Cupples LA. A genome-wide scan for loci linked to plasma levels of glucose and HbA(1c) in a community-based sample of Caucasian pedigrees: The Framingham Offspring Study. Diabetes. 2002;51(3):833–40. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.3.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Giesen K, Plum L, Kluge R, Ortlepp J, Joost HG. Diet-dependent obesity and hypercholesterolemia in the New Zealand obese mouse: identification of a quantitative trait locus for elevated serum cholesterol on the distal mouse chromosome 5. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;304(4):812–7. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00664-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jurgens HS, Neschen S, Ortmann S, Scherneck S, Schmolz K, Schuler G, Schmidt S, Bluher M, Klaus S, Perez-Tilve D, et al. Development of diabetes in obese, insulin-resistant mice: essential role of dietary carbohydrate in beta cell destruction. Diabetologia. 2007;50(7):1481–9. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0662-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kluge R, Giesen K, Bahrenberg G, Plum L, Ortlepp JR, Joost HG. Quantitative trait loci for obesity and insulin resistance (Nob1, Nob2) and their interaction with the leptin receptor allele (LeprA720T/T1044I) in New Zealand obese mice. Diabetologia. 2000;43(12):1565–72. doi: 10.1007/s001250051570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chadt A, Leicht K, Deshmukh A, Jiang LQ, Scherneck S, Bernhardt U, Dreja T, Vogel H, Schmolz K, Kluge R, et al. Tbc1d1 mutation in lean mouse strain confers leanness and protects from diet-induced obesity. Nature genetics. 2008;40(11):1354–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Szekeres F, Chadt A, Tom RZ, Deshmukh AS, Chibalin AV, Bjornholm M, Al-Hasani H, Zierath JR. The Rab-GTPase-activating protein TBC1D1 regulates skeletal muscle glucose metabolism. American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism. 2012;303(4):E524–33. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00605.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rutti S, Arous C, Nica AC, Kanzaki M, Halban PA, Bouzakri K. Expression, phosphorylation and function of the Rab-GTPase activating protein TBC1D1 in pancreatic beta-cells. FEBS letters. 2014;588(1):15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Toye AA, Lippiat JD, Proks P, Shimomura K, Bentley L, Hugill A, Mijat V, Goldsworthy M, Moir L, Haynes A, et al. A genetic and physiological study of impaired glucose homeostasis control in C57BL/6J mice. Diabetologia. 2005;48(4):675–86. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1680-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Meimaridou E, Kowalczyk J, Guasti L, Hughes CR, Wagner F, Frommolt P, Nurnberg P, Mann NP, Banerjee R, Saka HN, et al. Mutations in NNT encoding nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase cause familial glucocorticoid deficiency. Nature genetics. 2012;44(7):740–2. doi: 10.1038/ng.2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Davis RC, van Nas A, Castellani LW, Zhao Y, Zhou Z, Wen P, Yu S, Qi H, Rosales M, Schadt EE, et al. Systems genetics of susceptibility to obesity-induced diabetes in mice. Physiological genomics. 2012;44(1):1–13. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00003.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang CY, Stapleton DS, Schueler KL, Rabaglia ME, Oler AT, Keller MP, Kendziorski CM, Broman KW, Yandell BS, Schadt EE, et al. Tsc2, a positional candidate gene underlying a quantitative trait locus for hepatic steatosis. Journal of lipid research. 2012;53(8):1493–501. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M025239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lan H, Rabaglia ME, Stoehr JP, Nadler ST, Schueler KL, Zou F, Yandell BS, Attie AD. Gene expression profiles of nondiabetic and diabetic obese mice suggest a role of hepatic lipogenic capacity in diabetes susceptibility. Diabetes. 2003;52(3):688–700. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.3.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rachdi L, Balcazar N, Osorio-Duque F, Elghazi L, Weiss A, Gould A, Chang-Chen KJ, Gambello MJ, Bernal-Mizrachi E. Disruption of Tsc2 in pancreatic beta cells induces beta cell mass expansion and improved glucose tolerance in a TORC1-dependent manner. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(27):9250–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803047105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bodnar JS, Chatterjee A, Castellani LW, Ross DA, Ohmen J, Cavalcoli J, Wu C, Dains KM, Catanese J, Chu M, et al. Positional cloning of the combined hyperlipidemia gene Hyplip1. Nature genetics. 2002;30(1):110–6. doi: 10.1038/ng811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hui ST, Andres AM, Miller AK, Spann NJ, Potter DW, Post NM, Chen AZ, Sachithanantham S, Jung DY, Kim JK, et al. Txnip balances metabolic and growth signaling via PTEN disulfide reduction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(10):3921–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800293105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Minn AH, Hafele C, Shalev A. Thioredoxin-interacting protein is stimulated by glucose through a carbohydrate response element and induces beta-cell apoptosis. Endocrinology. 2005;146(5):2397–405. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Parikh H, Carlsson E, Chutkow WA, Johansson LE, Storgaard H, Poulsen P, Saxena R, Ladd C, Schulze PC, Mazzini MJ, et al. TXNIP regulates peripheral glucose metabolism in humans. PLoS medicine. 2007;4(5):e158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chen J, Hui ST, Couto FM, Mungrue IN, Davis DB, Attie AD, Lusis AJ, Davis RA, Shalev A. Thioredoxin-interacting protein deficiency induces Akt/Bcl-xL signaling and pancreatic beta-cell mass and protects against diabetes. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2008;22(10):3581–94. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-111690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chen J, Saxena G, Mungrue IN, Lusis AJ, Shalev A. Thioredoxin-interacting protein: a critical link between glucose toxicity and beta-cell apoptosis. Diabetes. 2008;57(4):938–44. doi: 10.2337/db07-0715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chutkow WA, Patwari P, Yoshioka J, Lee RT. Thioredoxin-interacting protein (Txnip) is a critical regulator of hepatic glucose production. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283(4):2397–406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708169200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Blouet C, Liu SM, Jo YH, Chua S, Schwartz GJ. TXNIP in Agrp neurons regulates adiposity, energy expenditure, and central leptin sensitivity. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2012;32(29):9870–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0353-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature. 1994;372(6505):425–32. doi: 10.1038/372425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chen H, Charlat O, Tartaglia LA, Woolf EA, Weng X, Ellis SJ, Lakey ND, Culpepper J, Moore KJ, Breitbart RE, et al. Evidence that the diabetes gene encodes the leptin receptor: identification of a mutation in the leptin receptor gene in db/db mice. Cell. 1996;84(3):491–5. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dickie MM. Mutations at the agouti locus in the mouse. The Journal of heredity. 1969;60(1):20–5. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a107920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Igel M, Becker W, Herberg L, Joost HG. Hyperleptinemia, leptin resistance, and polymorphic leptin receptor in the New Zealand obese mouse. Endocrinology. 1997;138(10):4234–9. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.10.5428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Halaas JL, Boozer C, Blair-West J, Fidahusein N, Denton DA, Friedman JM. Physiological response to long-term peripheral and central leptin infusion in lean and obese mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94(16):8878–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Andrikopoulos S, Rosella G, Gaskin E, Thorburn A, Kaczmarczyk S, Zajac JD, Proietto J. Impaired regulation of hepatic fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase in the New Zealand obese mouse model of NIDDM. Diabetes. 1993;42(12):1731–6. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.12.1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Junger E, Herberg L, Jeruschke K, Leiter EH. The diabetes-prone NZO/Hl strain. II. Pancreatic immunopathology. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology. 2002;82(7):843–53. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000018917.69993.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kim JH, Sen S, Avery CS, Simpson E, Chandler P, Nishina PM, Churchill GA, Naggert JK. Genetic analysis of a new mouse model for non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Genomics. 2001;74(3):273–86. doi: 10.1006/geno.2001.6569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kim JH, Stewart TP, Soltani-Bejnood M, Wang L, Fortuna JM, Mostafa OA, Moustaid-Moussa N, Shoieb AM, McEntee MF, Wang Y, et al. Phenotypic characterization of polygenic type 2 diabetes in TALLYHO/JngJ mice. J Endocrinol. 2006;191(2):437–46. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kondo K, Nozawa K, Tomita T, Ezaki K. Inbred strains resulting from Japanese mice. Bulletin of the Experimental Animals. 1957;6:107–112. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ikeda H. KK mouse. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 1994;24(Suppl):S313–S316. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(94)90268-2. (doi:10.1016/0168-8227(94)90268-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]