Abstract

Parathyroid hormone (PTH) is well-known as the principal regulator of calcium homeostasis in the human body and controls bone metabolism via actions on the survival and activation of osteoblasts. The intermittent administration of PTH has been shown to stimulate bone production in mice and men and therefore PTH administration has been recently approved for the treatment of osteoporosis. Besides to its physiological role in bone remodelling PTH has been demonstrated to influence and expand the bone marrow stem cell niche where hematopoietic stem cells, capable of both self-renewal and differentiation, reside. Moreover, intermittent PTH treatment is capable to induce mobilization of progenitor cells from the bone marrow into the bloodstream. This novel function of PTH on modulating the activity of the stem cell niche in the bone marrow as well as on mobilization and regeneration of bone marrow-derived stem cells offers new therapeutic options in bone marrow and stem cell transplantation as well as in the field of ischemic disorders.

Keywords: Parathyroid hormone, Stem cells, Bone marrow, Mobilization, Migration

Core tip: Parathyroid hormone (PTH) is the principal regulator of calcium homeostasis in the human body and controls bone metabolism. Besides to its physiological role in bone remodelling PTH has been demonstrated to influence and expand the bone marrow stem cell niche as well as to induce mobilization of progenitor cells from the bone marrow into the bloodstream. This novel function of PTH on modulating the activity of the stem cell niche in the bone marrow as well as on mobilization and regeneration of bone marrow-derived progenitor cells offers new therapeutic options in bone marrow and stem cell transplantation as well as in the field of ischemic disorders.

INTRODUCTION

Parathyroid hormone (PTH) is a peptide hormone secreted from the parathyroid glands that mainly acts on bone and kidney cells[1]. PTH is one of the two major hormones modulating calcium and phosphate homeostasis through its action to stimulate renal tubular calcium reabsorption and bone resorption[2]. Human PTH is an 84-amino acid peptide, but the first two amino acids in the N-terminal region of the hormone are mandatory for activation of the PTH 1 receptor (PTH1r), a membrane surface receptor expressed in multiple tissues including bone and kidney[3]. It has been appreciated that recombinant PTH 1-34 retains all of the biologic activity of the intact peptide (1-84)[4]. Patients with primary or secondary hyperparathyroidism and subsequently chronic exposure to high serum PTH concentrations revealed increased bone resorption[5]. However, in contrast to this observations after chronic exposure to high serum PTH concentrations, the intermittent administration of recombinant PTH in mice and men has been demonstrated to stimulate bone production more than resorption[6]. These observations finally guided the approval of intermittent recombinant PTH (1-34) for the treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal woman and subsequently in men[7-9]. Besides to its physiological role in bone remodelling, PTH has been shown to modulate the haematopoietic stem cell (HSC) niche in the bone marrow (BM)[10]. This review will focus on the molecular interplay between PTH and the HSC niche and will also discuss the ability of PTH to mobilize bone marrow-derived stem cells (BMCs) to the peripheral blood, which opens new therapeutic options for PTH in the field of bone marrow and stem cell transplantation as well as a potential role of PTH in the treatment of ischemic disorders.

PTH AND THE BM STEM CELL NICHE

BM is a complex organ, consisting of many different haematopoietic and non-haematopoietic cell types, that is surrounded by a shell of vascularized and innervated bone[11]. In the last years, there have been a lot of research and discussions about the existence and localizations of “niches”, specific local tissue microenvironments that maintain and regulate stem cells within the bone marrow[12]. The niche hypothesis has been proposed for the first time by Schofield et al[13] in 1978 and since then tremendous progress has been made in elucidating the location and cellular components of the HSC niche. It is now appreciated that the HSC niche is perivascular, created partly by mesenchymal stromal cells and endothelial cells and often, but not always, located near trabecular bone[11,14-19]. Calvi et al[10] were first able to demonstrate that osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche and that PTH is a pivotal regulator of the HSC microenvironment. They used transgenic mice carrying constitutively activated PTH/PTHrP receptors (PPRs) under control of the osteoblast-specific α1(I) collagen promoter and were able to detect a 2-fold increased number of Lin- Sca-1+ cKit+ (LSK) cells. PPR-stimulated osteoblastic cells produced high levels of the Notch ligand jagged 1 and supported an increase in the number of haematopoietic stem cells with evidence of Notch1 activation in vivo. Likewise, blocking Notch signaling with γ-secretase inhibitors inhibited the enhanced ability of these PPR activated osteoblasts to support long-term hematopoietic cultures. In a next step, they assessed whether PPR activation with PTH could have a meaningful physiological effect in vivo. They administered PTH to animals undergoing myeloablative bone marrow transplantation using limiting numbers of donor cells to mimic a setting of therapeutic need. Survival at 28 d in control mice that received mock injections after transplant was 27%. In sharp contrast, animals receiving pulse dosing of PTH had improved outcomes with 100% survival. The bone marrow histology of the two groups was also substantially different, with an increase in cellularity and a decrease in fat cells in the PTH-treated group[10]. That Jagged1 may play a critical role in mediating the PTH-dependent expansion of HSC, as well as the anabolic effect of PTH in bone was confirmed by Weber et al[20]. They showed the ability of PTH to augment Jag-1 expression on osteoblasts in an AC/PKA-dependent manner following 5 consecutive days of PTH administration. Jag-1 protein was increased on specific populations of osteoblasts including those at the endosteum and spindle-shaped cells in the bone marrow cavity[20]. PTH stimulation also augments the expression level of N-cadherin on osteoblasts[21,22]. N-cadherin-mediated adhesion may link to the canonical Wnt and Notch1 pathway through b-catenin signaling[23]. Wnt and Notch signaling pathways are known to be important in hematopoietic stem cell renewal[11,24-26].

As another important regulator of PTH-driven HSC expansion, a number of cytokines have been identified[11]. Several studies demonstrated increased expression of cytokines like IL-6, IL-11, G-CSF and stem cell factor (SCF)[27-31]. In this context, PTH signalling to osteoblasts resulted in an increase in the number of SCF+ cells[30,32]. Likewise, exposure to PTH resulted in enhanced expression of IL-6 and IL-11 in osteoblasts[33]. Jung et al[34] were able to demonstrate that expression of the chemokine stromal derived factor-1 (SDF-1, also termed CXCL12) by osteoblasts was increased following PTH administration. SDF-1 and its major receptor CXCR4 are pivotal in mediating both retention and mobilization of HSCs[35] and will be discussed at a later stage in this review. Brunner et al[36] compared a treatment regimen with G-CSF and PTH in a mouse model. They found that in contrast to G-CSF, PTH treatment resulted in an enhanced cell proliferation with a constant level of lin-/Sca-1+/c-kit+ cells and CD45+/CD34+ subpopulations in bone marrow[36]. Altogether the data on PTH and the bone marrow suggest an important role of PTH on the niche which allows the use PTH as a therapeutic tool to increase the number of BMSC. In the following chapter we will focus on the potential role of PTH to mobilize cells from the bone marrow to the bloodstream.

PTH AND STEM CELL MOBILIZATION

Under normal and pathological conditions there is continuous egress of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells out of the bone marrow to the circulation, termed mobilization[37]. Stem cell mobilization can be achieved experimentally in animal models or clinically by a great variety of agents, such as cytokines (e.g., G-CSF, SCF, Erythropoietin)[36,38-43] and small molecules (e.g., AMD3100)[44].

Following the intriguing data of Calvi et al[10] showing that PTH is a pivotal regulator of the HSC microenvironment and is able to increase the number of HSC in the BM, several preclinical studies investigated the effect of PTH administration on stem cell mobilization in mice. Adams et al[45] used three mouse models that are relevant to clinical uses of HSCs to test the hypothesis that targeting the niche might improve stem cell-based therapies. They treated mice with PTH for 5 wk following a 5-d regimen of G-CSF to mobilize BMCs from the bone marrow to the peripheral blood. They demonstrated that PTH administration increased the number of HSCs mobilized into the peripheral blood for stem cell harvests, protected stem cells from repeated exposure to cytotoxic chemotherapy and expanded stem cells in transplant recipients[45]. These results were corroborated by a study of our group where we explored the potency of PTH compared to granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) for mobilization of stem cells and its regenerative capacity on bone marrow. Healthy mice were either treated with PTH, G-CSF, or saline. HSCs characterized by lin-/Sca-1+/c-kit+, as well as subpopulations (CD31+, c-kit+, Sca-1+, CXCR4+) of CD45+/CD34+ and CD45+/CD34- cells were measured by flow cytometry. Immunohistology as well as fluorescein-activated cell sorting analyses were utilized to determine the composition and cell-cycle status of bone marrow cells. Serum levels of distinct cytokines [G-CSF, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)] were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Stimulation with PTH showed a significant increase of all characterized subpopulations of bone marrow-derived progenitor cells (BMCs) in peripheral blood (1.5- to 9.8-fold) similar to G-CSF. In contrast to G-CSF, PTH treatment resulted in an enhanced cell proliferation with a constant level of lin-/Sca-1+/c-kit+ cells and CD45+/CD34+ subpopulations in bone marrow. A combination of PTH and G-CSF showed only slight additional effects compared to PTH or G-CSF alone[36]. Interestingly, treatment with PTH resulted in significantly elevated concentrations of G-CSF in serum suggesting an indirect mobilizing effect of PTH via stimulation of osteoblasts producing G-CSF. To verify this hypothesis, PTH-stimulated mice were pre-treated with a G-CSF antibody and, thereby, the mobilizing effect could be significantly inhibited[36]. In a more clinically relevant model Brunner et al[5] investigated prospectively the effect of primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT), a condition with high PTH serum levels, on mobilization of BMCs in humans. In 22 patients with PHPT and 10 controls defined subpopulations of circulating BMCs were analyzed by flow cytometry. They found a significant increase of circulating BMCs and an upregulation of SDF-1 and VEGF serum levels in patients with PHPT. The number of these circulating cells positively correlated with PTH serum levels. Interestingly, the number of circulating BMCs returned to control levels measured after surgery[5].

Because of the therapeutic potential of PTH to activate and increase the number of HSCs in preclinical models, a phase I trial in humans has been conducted. A group of 20 human patients were included who had previously failed to produce a sufficient number of CD34+ HSCs in their peripheral blood following mobilization. Subjects were treated with PTH in escalating doses of 40 μg, 60 μg, 80 μg, and 100 μg for 14 d. On days 10-14 of treatment, subjects received filgrastim (G-CSF) 10 μg/kg. PTH administration was tolerated well and there was no dose-limiting toxicity. Of those patients who previously had a single mobilization failure, 47% met therapeutic mobilization criteria, of those who had previously failed two attempts at mobilization, the post PTH success rate was similar (40%)[46].

PTH AND STEM CELL HOMING VIA SDF1/CXCR4

In light of the promising results showing increased mobilization of BMCs after treatment with PTH, several studies also focused on the migration of different BMCs after PTH pulsing. The main axis of stem cell migration and homing is the interaction between SDF-1a and the homing receptor CXCR-4, which is expressed on many circulating progenitor cells[47,48]. It has been shown that CXCR4- and SDF-1-deficient mice have a severe migration defect of HSCs from the embryonic liver to the bone marrow by the end of the second trimester. At this period of development, SDF-1 is upregulated in bone marrow and chemoattracts HSCs. Later in life the SDF-1-CXCR4 axis plays a crucial role in the retention and homing of HSCs in the bone marrow stem cell niche[35]. SDF-1 is expressed by different cell types, including stromal and endothelial cells, bone marrow, heart, skeletal muscle, liver and brain[49]. Active SDF-1 binds to its receptor CXCR-4 and is cleaved at its position 2 by CD26/dipeptidylpeptidase IV (DPP-IV), a membrane-bound extracellular peptidase[50-55]. The truncated form of SDF-1 not only loses its chemotactic properties, but also blocks chemotaxis of full length SDF-1[50]. DPP-IV is expressed on many hematopoietic cell populations and is present in a catalytically active soluble form in the plasma[56]. In a chimeric mouse model to track BMCs by ubiquitously expression of EGFP under control of the ubiquitin C promoter, Brunner et al[37] demonstrated reduced migration of CXCR-4+ BMCs associated with decreased expression levels of the corresponding growth factor SDF-1 in ischemic myocardium after treatment with G-CSF. This could be explained by N-terminal cleavage of CXCR4 on mobilized haematopoietic progenitor cells resulting in loss of chemotaxis in response to SDF-1[57]. In contrast, PTH treated animals revealed an enhanced homing of BMCs associated with an increased protein level of SDF-1 in the ischemic heart[58,59]. Jung et al[34] showed recently enhanced levels of SDF-1 in the bone marrow after PTH stimulation. Therefore, our group used an enzymatic activity assay to investigate whether the elevated levels of SDF-1 protein in the ischemic heart after PTH stimulation may be due to changes of DPP-IV activity. Indeed, we were able to demonstrate that PTH inhibited the activity of DPP-IV in vitro and in vivo[58]. In order to exploit whether the observed enhanced stem cell homing after PTH treatment was dependent on an intact SDF-1/CXCR4 axis, the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 was injected along with PTH. In fact, the number of CD34+/CD45+ BMCs was significantly decreased in mice treated with PTH and AMD3100 compared to animals treated solely with PTH[58]. A similar pharmacological concept has been done recently by Zaruba et al[60]. They used a dual non-invasive therapy based on mobilization of stem cells with G-CSF and pharmacological inhibition of the protease DPP-IV/CD26 and observed enhanced mobilization and migration of different BMC fractions to the ischemic heart[60,61]. In 2006, a preclinical study with transgenic mice carrying a G-CSF deficiency was done to address the question whether PTH-induced homing of BMCs to the ischemic myocardium is G-SCF-dependent. Corroborating previous studies[58,59,62], PTH treatment resulted in a significant increase in BMCs in peripheral blood in G-CSF +/+ but not in G-CSF knockout mice. However, a significant increase in SDF-1 levels as well as enhanced migration of BMCs into the ischemic myocardium was observed after PTH treatment in both G-CSF+/+ and G-CSF-/- mice. These data suggest that homing of BMCs is independent of endogenous G-CSF[63].

In summary, data on preclinical and clinical studies reveal that PTH is a promising substance to enhance migration and homing of BMCs to ischemic tissue due to modulation of the pivotal SDF-1/CXCR4 axis.

PTH FOR THE TREATMENT OF ISCHEMIC DISORDERS

There is a long-lasting interest in the cardiovascular effects of PTH[64]. It has been shown that cardiovascular cells, cardiomyocytes and smooth muscle cells are target cells for PTH. PTH is known to induce arterial vasodilation, which is based on the activation of PTH/PTHrP receptor type I. Upon receptor activation, PTH causes an increase of cAMP production leading to a decreased calcium influx resulting in vasodilation[65,66].

After Calvi et al[10] established that PTH could alter the HSC niche resulting in HSC expansion and the fact that PTH treatment improved dramatically the survival of mice receiving bone marrow transplants, there was an emerging interest on a potential cardioprotective role of PTH. First, Zaruba et al[62] exploited the impact of PTH on post-MI survival and functional parameters in a murine model of myocardial infarction. They injected the biological active fragment of PTH [PTH1-34] for up to 14 consecutive days. PTH treatment after MI exerted beneficial effects on survival and myocardial function 6 and 30 d after MI which was associated with an altered cardiac remodelling reflected by smaller infarct sizes. Furthermore, PTH treated animals revealed an augmented mobilization and homing of angiogenic CD45+/CD34+ BMCs associated with an improved neovascularization[62,67]. In a more recent study, the effect of G-CSF, PTH, and the combination of both was investigated using the innovative pinhole single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) technique, which allows non-invasive, repetitive, quantitative, and especially intraindividual evaluations of infarct size[68]. SPECT analyses revealed that PTH treatment resulted in a significant reduction of perfusion defects from day 6 to day 30 in contrast to G-CSF alone. A combination of both cytokines had no additional effects on myocardial perfusion[59]. To further elucidate the cardioprotective mechanism of PTH, our group focused on the pivotal SDF-1/CXCR4 axis. PTH treatment again significantly improved myocardial function after MI associated with enhanced homing of CXCR4+ BMCs. Homing of BMCs occurred along a SDF-1 protein gradient. Low levels of SDF-1 in the peripheral blood and high SDF-1 levels in the ischemic heart guided CXCR4+ BMCs to the ischemic myocardium. Interestingly, stem cell homing and functional recovery were both reversed by blocking the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis using the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100[58]. PTH injections in transgenic G-CSF deficient mice showed that the cardioprotective effects of PTH are independent of endogenous G-CSF release[63].

That PTH treatment not only exerts beneficial effects in ischemic cardiovascular disorders shows a recent work where PTH therapy was tested after ischemic stroke in mice. PTH treatment significantly increased the expression of cytokines including VEGF, SDF-1, BDNF and Tie-1 in the brain peri-infarct region. Moreover, PTH treatment increased angiogenesis in ischemic brain, promoted neuroblast migration from the subventriular zone and increased the number of newly formed neurons in the peri-infarct cortex. Furthermore, PTH-treated mice revealed better sensorimotor functional recovery compared to stroke controls[69].

CONCLUSION

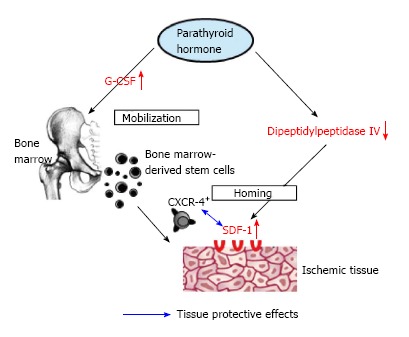

In summary, experimental and clinical data suggest a novel function of PTH on modulating the activity of the bone marrow stem cell niche as well as on mobilization and homing of BMCs. PTH is a natural DPP-IV inhibitor and is able to increase SDF-1 protein level in ischemic tissue, which enhances recruitment of regenerative BMCs associated with improved functional recovery. Based on the fact that PTH has already been clinically approved in patients with osteoporosis[8], the data offer new therapeutic options for PTH in bone marrow and stem cells transplantation as well as in the field of ischemic disorders (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Impact of parathyroid hormone on mobilization and homing of bone marrow-derived stem cells. Left axis: PTH administration results in mobilization of BMCs from bone marrow into peripheral blood via endogenous release of G-CSF. Right axis: PTH results in down-regulation of DPPIV, which inhibits inactivation of SDF-1 and therefore promotes homing of CXCR4+ BMCs. PTH: Parathyroid hormone; BMCs: Bone marrow-derived stem cells; G-CSF: Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; SDF-1: Stromal de-rived factor-1.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Panchu P, Takenaga K, Zhou S S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

References

- 1.Shimizu E, Selvamurugan N, Westendorf JJ, Partridge NC. Parathyroid hormone regulates histone deacetylases in osteoblasts. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1116:349–353. doi: 10.1196/annals.1402.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown EM. Four-parameter model of the sigmoidal relationship between parathyroid hormone release and extracellular calcium concentration in normal and abnormal parathyroid tissue. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;56:572–581. doi: 10.1210/jcem-56-3-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hodsman AB, Bauer DC, Dempster DW, Dian L, Hanley DA, Harris ST, Kendler DL, McClung MR, Miller PD, Olszynski WP, et al. Parathyroid hormone and teriparatide for the treatment of osteoporosis: a review of the evidence and suggested guidelines for its use. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:688–703. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar R, Thompson JR. The regulation of parathyroid hormone secretion and synthesis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:216–224. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010020186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunner S, Theiss HD, Murr A, Negele T, Franz WM. Primary hyperparathyroidism is associated with increased circulating bone marrow-derived progenitor cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E1670–E1675. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00287.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crandall C. Parathyroid hormone for treatment of osteoporosis. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2297–2309. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.20.2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finkelstein JS, Hayes A, Hunzelman JL, Wyland JJ, Lee H, Neer RM. The effects of parathyroid hormone, alendronate, or both in men with osteoporosis. New Engl J Med. 2003;349:1216–1226. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neer RM, Arnaud CD, Zanchetta JR, Prince R, Gaich GA, Reginster JY, Hodsman AB, Eriksen EF, Ish-Shalom S, Genant HK, et al. Effect of parathyroid hormone (1-34) on fractures and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1434–1441. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105103441904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Black DM, Greenspan SL, Ensrud KE, Palermo L, McGowan JA, Lang TF, Garnero P, Bouxsein ML, Bilezikian JP, Rosen CJ. The effects of parathyroid hormone and alendronate alone or in combination in postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1207–1215. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calvi LM, Adams GB, Weibrecht KW, Weber JM, Olson DP, Knight MC, Martin RP, Schipani E, Divieti P, Bringhurst FR, et al. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. 2003;425:841–846. doi: 10.1038/nature02040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morrison SJ, Scadden DT. The bone marrow niche for haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2014;505:327–334. doi: 10.1038/nature12984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kfoury Y, Mercier F, Scadden DT. SnapShot: The hematopoietic stem cell niche. Cell. 2014;158:228–228.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schofield R. The relationship between the spleen colony-forming cell and the haemopoietic stem cell. Blood Cells. 1978;4:7–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sacchetti B, Funari A, Michienzi S, Di Cesare S, Piersanti S, Saggio I, Tagliafico E, Ferrari S, Robey PG, Riminucci M, et al. Self-renewing osteoprogenitors in bone marrow sinusoids can organize a hematopoietic microenvironment. Cell. 2007;131:324–336. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Méndez-Ferrer S, Michurina TV, Ferraro F, Mazloom AR, Macarthur BD, Lira SA, Scadden DT, Ma’ayan A, Enikolopov GN, Frenette PS. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature. 2010;466:829–834. doi: 10.1038/nature09262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guezguez B, Campbell CJ, Boyd AL, Karanu F, Casado FL, Di Cresce C, Collins TJ, Shapovalova Z, Xenocostas A, Bhatia M. Regional localization within the bone marrow influences the functional capacity of human HSCs. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:175–189. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan CK, Chen CC, Luppen CA, Kim JB, DeBoer AT, Wei K, Helms JA, Kuo CJ, Kraft DL, Weissman IL. Endochondral ossification is required for haematopoietic stem-cell niche formation. Nature. 2009;457:490–494. doi: 10.1038/nature07547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ellis SL, Grassinger J, Jones A, Borg J, Camenisch T, Haylock D, Bertoncello I, Nilsson SK. The relationship between bone, hemopoietic stem cells, and vasculature. Blood. 2011;118:1516–1524. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-303800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adams GB, Chabner KT, Alley IR, Olson DP, Szczepiorkowski ZM, Poznansky MC, Kos CH, Pollak MR, Brown EM, Scadden DT. Stem cell engraftment at the endosteal niche is specified by the calcium-sensing receptor. Nature. 2006;439:599–603. doi: 10.1038/nature04247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weber JM, Forsythe SR, Christianson CA, Frisch BJ, Gigliotti BJ, Jordan CT, Milner LA, Guzman ML, Calvi LM. Parathyroid hormone stimulates expression of the Notch ligand Jagged1 in osteoblastic cells. Bone. 2006;39:485–493. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haÿ E, Laplantine E, Geoffroy V, Frain M, Kohler T, Müller R, Marie PJ. N-cadherin interacts with axin and LRP5 to negatively regulate Wnt/beta-catenin signaling, osteoblast function, and bone formation. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:953–964. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00349-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marie PJ. Role of N-cadherin in bone formation. J Cell Physiol. 2002;190:297–305. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reya T, Duncan AW, Ailles L, Domen J, Scherer DC, Willert K, Hintz L, Nusse R, Weissman IL. A role for Wnt signalling in self-renewal of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2003;423:409–414. doi: 10.1038/nature01593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim JA, Kang YJ, Park G, Kim M, Park YO, Kim H, Leem SH, Chu IS, Lee JS, Jho EH, et al. Identification of a stroma-mediated Wnt/beta-catenin signal promoting self-renewal of hematopoietic stem cells in the stem cell niche. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1318–1329. doi: 10.1002/stem.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fleming HE, Janzen V, Lo Celso C, Guo J, Leahy KM, Kronenberg HM, Scadden DT. Wnt signaling in the niche enforces hematopoietic stem cell quiescence and is necessary to preserve self-renewal in vivo. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:274–283. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schaniel C, Sirabella D, Qiu J, Niu X, Lemischka IR, Moore KA. Wnt-inhibitory factor 1 dysregulation of the bone marrow niche exhausts hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2011;118:2420–2429. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-305664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Broxmeyer HE. Regulation of hematopoiesis by chemokine family members. Int J Hematol. 2001;74:9–17. doi: 10.1007/BF02982544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duarte RF, Franf DA. The synergy between stem cell factor (SCF) and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF): molecular basis and clinical relevance. Leuk Lymphoma. 2002;43:1179–1187. doi: 10.1080/10428190290026231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duarte RF, Frank DA. SCF and G-CSF lead to the synergistic induction of proliferation and gene expression through complementary signaling pathways. Blood. 2000;96:3422–3430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taichman RS. Blood and bone: two tissues whose fates are intertwined to create the hematopoietic stem-cell niche. Blood. 2005;105:2631–2639. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taichman RS, Emerson SG. Human osteoblasts support hematopoiesis through the production of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1677–1682. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.5.1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blair HC, Julian BA, Cao X, Jordan SE, Dong SS. Parathyroid hormone-regulated production of stem cell factor in human osteoblasts and osteoblast-like cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;255:778–784. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenfield EM, Horowitz MC, Lavish SA. Stimulation by parathyroid hormone of interleukin-6 and leukemia inhibitory factor expression in osteoblasts is an immediate-early gene response induced by cAMP signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10984–10989. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jung Y, Wang J, Schneider A, Sun YX, Koh-Paige AJ, Osman NI, McCauley LK, Taichman RS. Regulation of SDF-1 (CXCL12) production by osteoblasts; a possible mechanism for stem cell homing. Bone. 2006;38:497–508. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zaruba MM, Franz WM. Role of the SDF-1-CXCR4 axis in stem cell-based therapies for ischemic cardiomyopathy. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2010;10:321–335. doi: 10.1517/14712590903460286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brunner S, Zaruba MM, Huber B, David R, Vallaster M, Assmann G, Mueller-Hoecker J, Franz WM. Parathyroid hormone effectively induces mobilization of progenitor cells without depletion of bone marrow. Exp Hematol. 2008;36:1157–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brunner S, Huber BC, Fischer R, Groebner M, Hacker M, David R, Zaruba MM, Vallaster M, Rischpler C, Wilke A, et al. G-CSF treatment after myocardial infarction: impact on bone marrow-derived vs cardiac progenitor cells. Exp Hematol. 2008;36:695–702. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deindl E, Zaruba MM, Brunner S, Huber B, Mehl U, Assmann G, Hoefer IE, Mueller-Hoecker J, Franz WM. G-CSF administration after myocardial infarction in mice attenuates late ischemic cardiomyopathy by enhanced arteriogenesis. FASEB J. 2006;20:956–958. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4763fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brunner S, Engelmann MG, Franz WM. Stem cell mobilisation for myocardial repair. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2008;8:1675–1690. doi: 10.1517/14712598.8.11.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brunner S, Theiss HD, Leiss M, Grabmaier U, Grabmeier J, Huber B, Vallaster M, Clevert DA, Sauter M, Kandolf R, et al. Enhanced stem cell migration mediated by VCAM-1/VLA-4 interaction improves cardiac function in virus-induced dilated cardiomyopathy. Basic Res Cardiol. 2013;108:388. doi: 10.1007/s00395-013-0388-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brunner S, Winogradow J, Huber BC, Zaruba MM, Fischer R, David R, Assmann G, Herbach N, Wanke R, Mueller-Hoecker J, et al. Erythropoietin administration after myocardial infarction in mice attenuates ischemic cardiomyopathy associated with enhanced homing of bone marrow-derived progenitor cells via the CXCR-4/SDF-1 axis. FASEB J. 2009;23:351–361. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-109462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brunner S, Huber BC, Weinberger T, Vallaster M, Wollenweber T, Gerbitz A, Hacker M, Franz WM. Migration of bone marrow-derived cells and improved perfusion after treatment with erythropoietin in a murine model of myocardial infarction. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16:152–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01286.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ding L, Saunders TL, Enikolopov G, Morrison SJ. Endothelial and perivascular cells maintain haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2012;481:457–462. doi: 10.1038/nature10783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Broxmeyer HE, Orschell CM, Clapp DW, Hangoc G, Cooper S, Plett PA, Liles WC, Li X, Graham-Evans B, Campbell TB, et al. Rapid mobilization of murine and human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells with AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1307–1318. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adams GB, Martin RP, Alley IR, Chabner KT, Cohen KS, Calvi LM, Kronenberg HM, Scadden DT. Therapeutic targeting of a stem cell niche. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:238–243. doi: 10.1038/nbt1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ballen KK, Shpall EJ, Avigan D, Yeap BY, Fisher DC, McDermott K, Dey BR, Attar E, McAfee S, Konopleva M, et al. Phase I trial of parathyroid hormone to facilitate stem cell mobilization. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:838–843. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Askari AT, Unzek S, Popovic ZB, Goldman CK, Forudi F, Kiedrowski M, Rovner A, Ellis SG, Thomas JD, DiCorleto PE, et al. Effect of stromal-cell-derived factor 1 on stem-cell homing and tissue regeneration in ischaemic cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2003;362:697–703. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Franz WM, Zaruba M, Theiss H, David R. Stem-cell homing and tissue regeneration in ischaemic cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2003;362:675–676. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14240-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kucia M, Reca R, Miekus K, Wanzeck J, Wojakowski W, Janowska-Wieczorek A, Ratajczak J, Ratajczak MZ. Trafficking of normal stem cells and metastasis of cancer stem cells involve similar mechanisms: pivotal role of the SDF-1-CXCR4 axis. Stem Cells. 2005;23:879–894. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Christopherson KW, Cooper S, Broxmeyer HE. Cell surface peptidase CD26/DPPIV mediates G-CSF mobilization of mouse progenitor cells. Blood. 2003;101:4680–4686. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Christopherson KW, Cooper S, Hangoc G, Broxmeyer HE. CD26 is essential for normal G-CSF-induced progenitor cell mobilization as determined by CD26(-/-) mice. Experimental Hematology. 2003;31:1126–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Christopherson KW, Hangoc G, Broxmeyer HE. Cell surface peptidase CD26/dipeptidylpeptidase IV regulates CXCL12/stromal cell-derived factor-1 alpha-mediated chemotaxis of human cord blood CD34+ progenitor cells. J Immunol. 2002;169:7000–7008. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.7000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Christopherson KW, Hangoc G, Mantel CR, Broxmeyer HE. Modulation of hematopoietic stem cell homing and engraftment by CD26. Science. 2004;305:1000–1003. doi: 10.1126/science.1097071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Christopherson KW, Uralila SE, Porechaa NK, Zabriskiea RC, Kidda SM, Ramin SM. G-CSF- and GM-CSF-induced upregulation of CD26 peptidase downregulates the functional chemotactic response of CD34þCD38 human cord blood hematopoietic cells. Experimental Hematology. 2006;34:1060–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Christopherson KW, Paganessi LA, Napier S, Porecha NK. CD26 inhibition on CD34+ or lineage- human umbilical cord blood donor hematopoietic stem cells/hematopoietic progenitor cells improves long-term engraftment into NOD/SCID/Beta2null immunodeficient mice. Stem Cells Dev. 2007;16:355–360. doi: 10.1089/scd.2007.9996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Durinx C, Lambeir AM, Bosmans E, Falmagne JB, Berghmans R, Haemers A, Scharpé S, De Meester I. Molecular characterization of dipeptidyl peptidase activity in serum: soluble CD26/dipeptidyl peptidase IV is responsible for the release of X-Pro dipeptides. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:5608–5613. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lévesque JP, Hendy J, Takamatsu Y, Simmons PJ, Bendall LJ. Disruption of the CXCR4/CXCL12 chemotactic interaction during hematopoietic stem cell mobilization induced by GCSF or cyclophosphamide. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:187–196. doi: 10.1172/JCI15994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huber BC, Brunner S, Segeth A, Nathan P, Fischer R, Zaruba MM, Vallaster M, Theiss HD, David R, Gerbitz A, et al. Parathyroid hormone is a DPP-IV inhibitor and increases SDF-1-driven homing of CXCR4(+) stem cells into the ischaemic heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;90:529–537. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huber BC, Fischer R, Brunner S, Groebner M, Rischpler C, Segeth A, Zaruba MM, Wollenweber T, Hacker M, Franz WM. Comparison of parathyroid hormone and G-CSF treatment after myocardial infarction on perfusion and stem cell homing. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H1466–H1471. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00033.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zaruba MM, Theiss HD, Vallaster M, Mehl U, Brunner S, David R, Fischer R, Krieg L, Hirsch E, Huber B, et al. Synergy between CD26/DPP-IV inhibition and G-CSF improves cardiac function after acute myocardial infarction. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:313–323. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Theiss HD, Gross L, Vallaster M, David R, Brunner S, Brenner C, Nathan P, Assmann G, Mueller-Hoecker J, Vogeser M, et al. Antidiabetic gliptins in combination with G-CSF enhances myocardial function and survival after acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:3359–3369. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.04.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zaruba MM, Huber BC, Brunner S, Deindl E, David R, Fischer R, Assmann G, Herbach N, Grundmann S, Wanke R, et al. Parathyroid hormone treatment after myocardial infarction promotes cardiac repair by enhanced neovascularization and cell survival. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;77:722–731. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brunner S, Weinberger T, Huber BC, Segeth A, Zaruba MM, Theiss HD, Assmann G, Herbach N, Wanke R, Mueller-Hoecker J, et al. The cardioprotective effects of parathyroid hormone are independent of endogenous granulocyte-colony stimulating factor release. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;93:330–339. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schlüter KD, Piper HM. Cardiovascular actions of parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone-related peptide. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;37:34–41. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00194-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schlüter KD, Piper HM. Trophic effects of catecholamines and parathyroid hormone on adult ventricular cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:H1739–H1746. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.6.H1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schlüter KD, Wingender E, Tegge W, Piper HM. Parathyroid hormone-related protein antagonizes the action of parathyroid hormone on adult cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3074–3078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schlüter KD, Schreckenberg R, Wenzel S. Stem cell mobilization versus stem cell homing: potential role for parathyroid hormone? Cardiovasc Res. 2008;77:612–613. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wollenweber T, Zach C, Rischpler C, Fischer R, Nowak S, Nekolla SG, Gröbner M, Ubleis C, Assmann G, Müller-Höcker J, et al. Myocardial perfusion imaging is feasible for infarct size quantification in mice using a clinical single-photon emission computed tomography system equipped with pinhole collimators. Mol Imaging Biol. 2010;12:427–434. doi: 10.1007/s11307-009-0281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang LL, Chen D, Lee J, Gu X, Alaaeddine G, Li J, Wei L, Yu SP. Mobilization of endogenous bone marrow derived endothelial progenitor cells and therapeutic potential of parathyroid hormone after ischemic stroke in mice. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87284. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]