Abstract

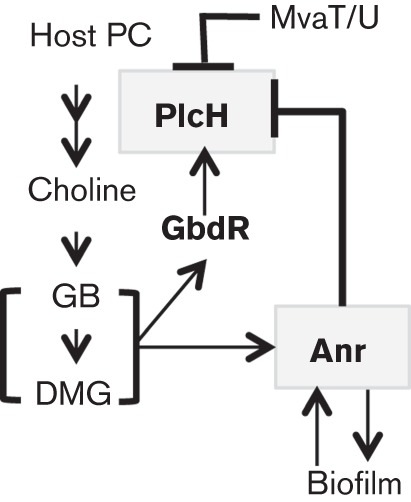

Haemolytic phospholipase C (PlcH) is a potent virulence and colonization factor that is expressed at high levels by Pseudomonas aeruginosa within the mammalian host. The phosphorylcholine liberated from phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin by PlcH is further catabolized into molecules that both support growth and further induce plcH expression. We have shown previously that the catabolism of PlcH-released choline leads to increased activity of Anr, a global transcriptional regulator that promotes biofilm formation and virulence. Here, we demonstrated the presence of a negative feedback loop in which Anr repressed plcH transcription and we proposed that this regulation allowed for PlcH levels to be maintained in a way that promotes productive host–pathogen interactions. Evidence for Anr-mediated regulation of PlcH came from data showing that growth at low oxygen (1 %) repressed PlcH abundance and plcH transcription in the WT, and that plcH transcription was enhanced in an Δanr mutant. The plcH promoter featured an Anr consensus sequence that was conserved across all P. aeruginosa genomes and mutation of conserved nucleotides within the Anr consensus sequence increased plcH expression under hypoxic conditions. The Anr-regulated transcription factor Dnr was not required for this effect. The loss of Anr was not sufficient to completely derepress plcH transcription as GbdR, a positive regulator of plcH, was required for expression. Overexpression of Anr was sufficient to repress plcH transcription even at 21 % oxygen. Anr repressed plcH expression and phospholipase C activity in a cell culture model for P. aeruginosa–epithelial cell interactions.

Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa squanders few opportunities to colonize a vulnerable human host. In addition to engendering a range of nosocomial infections, including keratitis (Green et al., 2008), burn wounds (de Macedo & Santos, 2005), endocarditis (Baddour et al., 2005) and implanted medical devices (Hidron et al., 2008), it also colonizes the lungs of 80 % of persons with the heritable disease cystic fibrosis (CF) (Rajan & Saiman, 2002; Rosenfeld et al., 2003). Colonization by P. aeruginosa contributes to the decline of lung function in this patient population (Rajan & Saiman, 2002), due in part to its wide array of virulence factors that promote its growth and persistence within the host. One such virulence factor is the well-characterized exotoxin haemolytic phospholipase C (PlcH), which is secreted by P. aeruginosa when in association with eukaryotic hosts. PlcH is essential for virulence in co-culture with fungal filaments, on Arabidopsis leaves, in Galleria mellonella larvae and in mammalian hosts (Hogan & Kolter, 2002; Jander et al., 2000; Rahme et al., 2000), highlighting its importance in diverse models of infection.

PlcH degrades the abundant phospholipids phosphatidylcholine (PC) and sphingomyelin, which are found in eukaryotic membranes and in lung surfactant (Berka & Vasil, 1982; Vasil, 2006). PC degradation releases both fatty acids and choline-containing compounds that are further degraded for catabolism (Kang et al., 2008; Son et al., 2007; Wargo et al., 2008). Once choline is liberated and transported into the cytoplasm, its catabolism promotes the activity of the transcriptional regulator Anr through an unknown mechanism under conditions where oxygen is normally destructive to the active dimer (Jackson et al., 2013; Malek et al., 2011; Massimelli et al., 2005). Anr is a homologue of the well-known Escherichia coli anaerobic regulator Fnr. Fnr is activated under conditions where oxygen levels are low because the presence of molecular oxygen destroys the [4Fe–4S]2+ cluster cofactor necessary for its dimerization and DNA-binding activity (Lazazzera et al., 1996; Sawers, 1991). Anr mediates the respiratory switch from normoxic to hypoxic and anoxic conditions (Schreiber et al., 2007; Ye et al., 1995). We reported previously that Anr was essential for normal biofilm development and host colonization in P. aeruginosa (Jackson et al., 2013). Wessel et al. (2014) recently demonstrated that densely populated P. aeruginosa colonies are depleted for oxygen. Furthermore, P. aeruginosa-containing mucus plugs have been shown to be strongly hypoxic in vivo (Høiby et al., 2001). For these reasons, we were interested in the fate of plcH expression in hypoxic environments.

Positive regulation of plcH expression occurs under circumstances where inorganic phosphate is limiting via the response regulator PhoB (Shortridge et al., 1992) and when choline is available (Shortridge et al., 1992; Wargo et al., 2009). GbdR, an AraC family transcription factor, positively regulates plcH expression in response to glycine betaine (GB) and dimethylglycine (DMG) (Wargo et al., 2009). GB and DMG are acquired from the oxidation of choline, and act as inducers for GbdR activity (Wargo et al., 2008; Wargo et al., 2009). To date, there are few publications reporting negative regulation of plcH in P. aeruginosa. Two reports demonstrated catabolite repression-mediated silencing of the plcH promoter (Diab et al., 2006; Sage et al., 1997). P. aeruginosa does not induce plcH when given choline in the presence of succinate, the preferred carbon source in the bacterium (Collier et al., 1996), allowing it to catabolize the other sources of carbon and energy, such as choline (Diab et al., 2006; Sage & Vasil, 1997). The histone-like nucleoid-associated proteins MvaT and MvaU were both shown to bind and inhibit the transcription of the plcH ORF in P. aeruginosa (Castang et al., 2008). Several publications have reported that a canonical Anr consensus sequence is positioned within the plcH promoter (Galimand et al., 1991; Trunk et al., 2010), suggesting a role for negative regulation of plcH by Anr. However, this regulatory scheme has not been established.

In this publication, we provide evidence that Anr repressed PlcH activity and plcH transcription under oxygen-limiting conditions. Anr-mediated repression of plcH was conserved in genetically distinct P. aeruginosa strains. Although Anr and the secondary regulator Dnr had identical consensus sequences, Dnr did not contribute to plcH repression under these conditions. Based on the finding that mutation of the Anr consensus sequences led to higher levels of plcH, we propose that Anr binds directly to the plcH promoter. Finally, we showed that Anr repressed plcH expression and phospholipase C (PLC) activity in co-culture with cultured human bronchial epithelial cells. These data established the long-suspected link between plcH expression and Anr activity in P. aeruginosa.

Methods

Growth conditions.

All of the strains used in these studies are listed in Table 1. Strains were maintained on lysogeny broth (LB) and during genetic manipulations. When indicated, media were supplemented with gentamicin at 60 µg ml−1 for P. aeruginosa and 10 µg ml−1 for E. coli. For overexpression studies, the medium was supplemented with 300 µg carbenicillin ml−1. Unless otherwise noted, cultures were grown in MOPS medium (Neidhardt et al., 1974) that contained 10 mM glucose, 1 mM choline chloride and 8 µM ferric chloride (MOPS-GCF). Overnight cultures were grown in 5 ml LB medium on a roller drum at 37 °C. For experiments, cultures in 50 ml flasks with 5 ml MOPS-GCF medium were used. Growth at 21 % oxygen was performed on a platform shaker at 225 r.p.m. in MOPS-GCF. For growth at 1 % oxygen, P. aeruginosa was cultured on a platform shaker at 225 r.p.m. in an InvivO2 400 Hypoxia Workstation (Ruskinn Technology) where the oxygen set point was 1 % and the carbon dioxide set point was 5 %. Oxygen levels were maintained with 94 % nitrogen and a gas regulator.

Table 1. Strain and plasmid list.

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype | Source | |

| Strains | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | |||

| PAO1 WT | DH1856 | ||

| PAO1 ΔplcHR | DH860 | In-frame plcHR deletion | Shortridge et al. (1992) |

| PAO1 Δanr | DH1857 | In-frame anr deletion | Jackson et al. (2013) |

| PAO1 Δanr+anr | DH1913 | Complementation of Δanr at the native locus | Jackson et al. (2013) |

| PAO1 ΔgbdR | DH543 | In-frame gbdR deletion | Wargo et al. (2008) |

| PAO1 Δanr Δdnr | DH2067 | Deletion of both anr and dnr | This study |

| PAO1 Δdnr | DH2036 | In-frame deletion of dnr in DH1856 | This study |

| PAO1 Δdnr att : dnr | DH2068 | Complementation of Δdnr at attTn7 site | This study |

| PA14 WT | DH1722 | ||

| PA14 Δanr | DH1977 | In-frame deletion of anr in DH1722 | L. Dietrich Columbia Univ. |

| Plasmids | |||

| pMQ30 | Allelic replacement vector; Gmr | Shanks et al. (2006) | |

| pMQ123 | Shanks et al. (2006) | ||

| pMQ123-anr | Anr overexpression vector | This study | |

| puc18T-mini-Tn7T-Gm | attTn7 site insertion vector | Choi & Schweizer (2006) | |

| pMW22 | plcH promoter upstream of lacZYA; Gmr | Wargo et al. (2009) | |

| pAAJ1 | Anr-binding motif mutated in pMW22 | This study | |

General statistics.

Experimental replicates were averaged for c.f.u., β-galactosidase and quantitative real-time (qRT)-PCR experiments. The means were compared using a two-sample t-test assuming unequal variance. P≤0.05 was considered significant.

Construction of in-frame deletion mutants and plasmids.

The Δdnr, Δdnr att : dnr and PAO1 pAnr-OE strains were constructed for this publication. The remaining strains listed in Table 1 were constructed previously as referenced. The dnr sequence, with its 1 kb up and downstream flanking regions (Winsor et al., 2011), was amplified and ligated into pMQ30 using yeast cloning (West et al., 1994). pDnrKO was transformed into E. coli S17λpir and then mated overnight with PAO1. Single-crossover mutants were selected by growth on gentamicin; then, following resolution of the merodiploid, double-crossover events were confirmed by growth on LB medium plates containing 5 % sucrose without NaCl. In-frame deletion mutants were identified by PCR. To complement Δdnr, dnr was amplified from PAO1 with its native promoter and ligated into puc18T-mini-Tn7T-Gm (Choi & Schweizer, 2006). The plasmid was then conjugated into P. aeruginosa to complement Δdnr at the att site. Overexpression constructs were made by amplifying the target gene in PAO1 without its native promoter and cloned into pMQ123 (Shanks et al., 2006). For plcH promoter mutagenesis assays, two of the nucleotides within the Anr consensus sequence were mutated in pMW22 by GenScript mutagenesis services.

PLC activity assays.

To visualize haemolytic activity, agar plates containing 5 % defibrinated sheep blood (Remel) were utilized. Plates were supplemented with 500 µl 1 M potassium phosphate (pH 7.0) by top spreading to prevent plcH induction due to phosphate limitation. Aliquots of 1 ml P. aeruginosa PAO1 WT and selected mutant overnight LB cultures were washed twice with an equal volume of distilled water and then spotted in 5 µl volumes onto the agar followed by 24 h incubation at 37 °C. Plates were imaged before and after the colonies were scraped off with a coverslip; removal of the colony allowed for better visualization of the zone of haemolysis.

To measure PLC activity, 10 µl P. aeruginosa WT and selected mutant supernatants were incubated with 90 µl artificial substrate p-nitrophenyl-phosphorylcholine (NPPC) as described by Kurioka & Matsuda (1976). The reaction buffer contained 100 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.2), 25 % glycerol and 20 mM NPPC. NPPC hydrolysis was detected by measuring A410. PLC activity is reported as the change in A410 in 60 min over the OD600 of the culture (ΔA410/OD600).

β-Galactosidase assays.

To monitor the induction of plcH, a plcH promoter lacZ fusion construct (pMW22) was used (Wargo et al., 2009). Briefly, the lacZYA operon was amplified from pRS415 (Simons et al., 1987) and ligated into pUCP22 (Schweizer, 1991) following digestion at KpnI and EcoRI, resulting in pMW5. A plcH promoter fragment (position −374 to −13) was amplified from pAES110 plcH : : lacZYA (Sage & Vasil, 1997) and ligated into pMW5 following digestion with XbaI and BamHI, resulting in pMW22. pMW22 was transformed into P. aeruginosa by electroporation and gentamicin-resistant colonies were selected as positive transformants. Cells were grown overnight at 37 °C in LB, then diluted into either 5 ml of fresh MOPS-GCF medium in a 50 ml flask at a starting OD600 0.05 or spotted onto phosphate-supplemented blood agar plates. Planktonic cultures were shaken at 225 r.p.m. at 37 °C for 6 h under atmospheric conditions or in a chamber with 1 % oxygen. For plate-based assays, colonies were collected after 16 h of growth in a chamber with 1 % oxygen at 37 °C. β-Galactosidase activity was measured as described previously (Miller, 1992; Zhang & Bremer, 1995).

qRT-PCR.

Cultures were grown in MOPS-GCF medium at 21 or 1 % oxygen. After 6 h, cells were harvested and RNA was isolated using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen). Following DNase treatment (DNA-free; Ambion) and cDNA synthesis, qRT-PCR was performed as follows: 94 °C for 3 min, 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 56 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 30 s, an extension at 72 °C for 2 min, and then a hold at 4 °C. The reaction mixtures used the Power SYBR master mix according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The following primers were used: dnr-Forward AGCCAGCTGTTCCGTTTCTC, dnr-Reverse GTGGCGTTCTTCAGGGAAAG; ppiD-Forward GGTGAGTCGTGGAAAGTGGT, ppiD-Reverse GTACATGGCCTTCTCGTCCT; and plcH-Forward GCAGTTGAACATCCGCAATC, plcH-Reverse CTGGTTCGGTTCGAGTTCATAG. Both the amplification and analysis were performed using the Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR System. Experimental transcripts were normalized to the housekeeping gene, ppiD.

Biofilm assays on airway epithelial cells.

For culture on airway epithelial cells, 5×105 mutant CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTRΔF508) homozygous human CF bronchial epithelial (CFBE) cells (CFBE41o−) (Cozens et al., 1994) were grown either in six-well plates or glass-bottomed dishes (MatTek), and then maintained in minimal essential medium (MEM) with serum for 9–10 days. Once a confluent monolayer formed, overnight cultures of P. aeruginosa strains in LB were resuspended into MEM to 1×108 c.f.u. Epithelial cells were washed once, then inoculated with 1 ml containing 1×108 P. aeruginosa and incubated for 1 h. Planktonic cells were removed and co-cultures were re-fed with serum-free MEM. PLC activity was measured in co-cultures that were not re-fed over the 5 h incubation period. To quantify bacterial cell attachment, co-cultures were washed twice with Dulbecco’s PBS and then treated with 1 ml 0.1 %Triton X-100 to detach and lyse epithelial cells along with attached bacteria from the wells. The cultures were homogenized, serially diluted, plated for c.f.u. on Pseudomonas isolation agar and counted after growth at 37 °C for 24 h.

Results

Oxygen limitation represses PlcH activity in P. aeruginosa

We have shown previously that PlcH activity on host PC in environments with oxygen leads to enhanced activation of the anoxia-associated Anr regulon, and that Anr promotes virulence in a pneumonia model and early steps in the colonization of airway epithelial cells (Jackson et al., 2013). When observing P. aeruginosa colonies grown on blood agar under normoxic and low oxygen conditions, we observed evidence for an additional relationship between oxygen tension and PlcH activity.

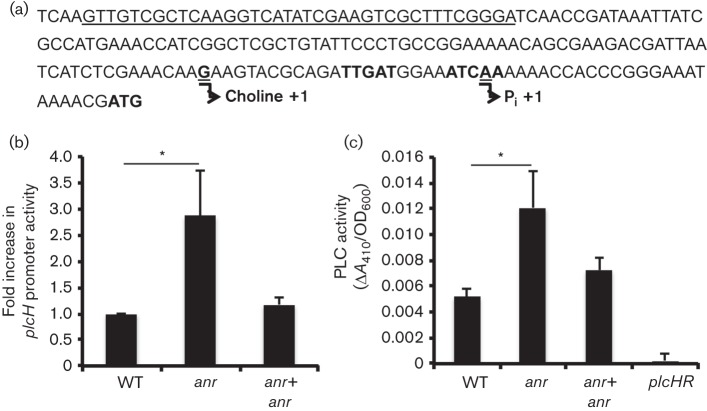

P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 haemolysis of sheep blood agar in plates was dependent on PlcH, as shown previously (Wargo et al., 2009). This was demonstrated by the fact that the WT formed clear zones in the agar underneath each colony, whilst ΔplcHR mutant colonies did not (Fig. 1a). Growth and haemolysis on the blood agar plates incubated at atmospheric oxygen (21 %) and under oxygen-limiting (1 %) conditions was assessed. Oxygen was indeed limiting at 1 % as growth was slower and the final number of c.f.u. within colonies was twofold lower in 1 % oxygen when compared with atmospheric oxygen (data not shown). The haemolytic phenotype of the PAO1 WT strain was strikingly different at 1 % oxygen as compared with 21 % oxygen. Under atmospheric oxygen conditions, a region of complete haemolysis was observed under WT colonies, whilst colonies incubated at 1 % oxygen did not give rise to a haemolytic zone.

Fig. 1.

Growth at 1 % oxygen decreases PlcH activity and plcH transcription. (a) P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 WT and ΔplcHR haemolytic activity was assayed on phosphate-supplemented blood agar plates at 21 and 1 % atmospheric oxygen. For plates incubated under each condition, images were captured before (left) and after (right) the colony was scraped off with a coverslip (n = 3). (b) The plcH promoter lacZ fusion [pMW22 (Wargo et al., 2009), noted as PplcH–lacZ] was used in P. aeruginosa PAO1 WT in PlcH-inducing medium at 37 °C for 6 h at 21 and 1 % oxygen. The data represent the mean±sd of three biological replicates. *P<0.05.

To determine if decreased PlcH-dependent haemolysis at 1 % oxygen was due to decreased plcH expression, we measured plcH expression in liquid cultures grown with shaking in chambers that were maintained at either 21 or 1 % oxygen. Activation of the plcH transcription was measured using a promoter fusion construct in which the plcH promoter was fused to lacZ. The transcriptional fusion strain was grown in planktonic cultures in MOPS-GCF medium. Mirroring the phenotypes observed on blood agar plates, plcH–lacZ expression was threefold lower at 1 % atmospheric oxygen when compared with 21 % oxygen (Fig. 1b).

Anr represses plcH transcription at 1 % atmospheric oxygen

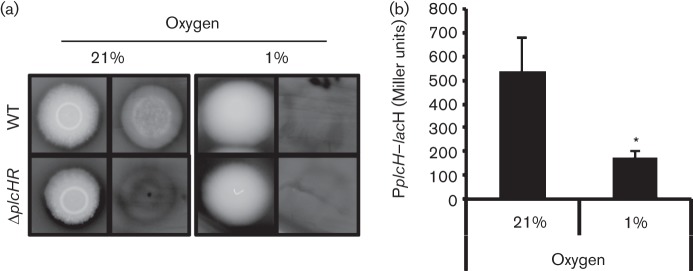

A sequence identical to that recognized by the oxygen-sensitive transcriptional regulator Anr is present within the plcH promoter region (Galimand et al., 1991; Trunk et al., 2010). Anr mainly acts as a regulator of gene expression under micro-oxic and anoxic conditions (Arai et al., 1995; Kawakami et al., 2010; Lu et al., 1999; Ye et al., 1995), and its activity increases as oxygen tensions decrease. The putative Anr-binding site (5′-TTGAT-N4-ATCAA-3′) lies downstream of the choline-dependent transcriptional start site (Fig. 2a) (Vasil, 1994), leading us to speculate that Anr was involved in the repression of plcH transcription under low oxygen conditions. To test this hypothesis, we grew WT, Δanr and the complemented Δanr mutant in MOPS-GCF medium in a 1 % oxygen atmosphere. The growth kinetics were similar between the anr mutant and the WT at 1 % oxygen, and this was consistent with published work showing that anr mutants were still able to grow and induce high-affinity cytochrome oxidase at oxygen concentrations as low as 0.4 % oxygen (Alvarez-Ortega & Harwood, 2007). We found that the Δanr mutant cultures displayed threefold more β-galactosidase activity than WT or the anr complemented strain under low oxygen conditions (Fig. 2b). The Δanr mutant also had higher levels of β-galactosidase activity in comparison with the WT strain when grown as colonies on blood agar (Fig. S1a, available in the online Supplementary Material). In aerated cultures grown in MOPS-GCF medium, activation of the plcH promoter was shown to be regulated positively by GbdR via the choline catabolites GB and DMG (Wargo et al., 2009). We found that GbdR activation of the plcH promoter was required for any detectable plcH expression under the 21 and 1 % oxygen culture conditions, indicating that the decreased Anr activity was not sufficient to promote plcH transcription (Fig. S2).

Fig. 2.

Anr represses plcH transcription and PlcH activity in 1 % oxygen. (a) Map of the plcH promoter showing the conserved GbdR (underlined) and Anr (bold font) (Trunk et al., 2010; Wargo et al., 2008) consensus sequences. The choline- and phosphate-dependent transcriptional start sites are shown underlined (Vasil, 1994). (b) WT, Δanr and Δanr+anr containing PplcH–lacZ were grown for 6 h at 1 % oxygen. The fold change in Miller units was calculated by normalizing values to WT. The mean of three biological replicates is shown. (c) PLC activities of culture supernatants grown for 6 h at 1 % oxygen were measured by NPPC hydrolysis. The nitrophenol product was measured at A410. The data represent the mean±sd of three replicate cultures. *P<0.05 (difference from WT).

Analysis of the genome sequences from 27 published P. aeruginosa strains revealed that the Anr motif in the strain PAO1 plcH promoter (Fig. 2a) was conserved in all strains, including PA14, suggesting that Anr-mediated regulation of plcH may be conserved across strains. To explore this prediction, the plcH promoter fusion constructs were introduced into a strain PA14 Δanr mutant and the WT. Genomic analyses have shown that PAO1 and PA14 are highly divergent strains within the species (He et al., 2004; Stover et al., 2000). As observed in PAO1, the PA14 Δanr mutant also had significantly higher levels of plcH promoter activity when compared with the strain PA14 WT (Fig. S1b), indicating that plcH repression by Anr at low oxygen was not a strain-specific phenomenon.

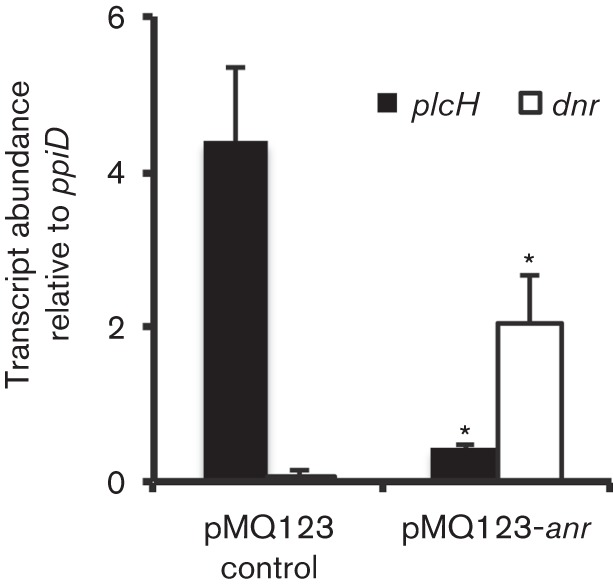

Anr overexpression is sufficient to repress plcH expression

To determine if increased Anr activity was sufficient to repress plcH transcription, we overexpressed Anr from a plasmid in strain PAO1 WT at 21 % oxygen and measured the abundance of plcH transcripts. To validate that anr overexpression in cultures grown with 21 % oxygen leads to increased Anr activity, we measured levels of dnr, an Anr-regulated transcript (Schreiber et al., 2007). In the overexpression strain, there was a 29-fold increase in dnr transcript abundance compared with a strain expressing the empty vector (Fig. 3). We observed a 10-fold reduction in plcH transcript levels upon Anr overexpression in comparison with the vector control (Fig. 3). These results indicated that Anr was active upon overexpression and suggested that Anr activity was sufficient to repress plcH transcription. The increased Anr activity upon anr overexpression even in the presence of oxygen may indicate that higher Anr levels poise cells to rapidly modulate the Anr regulon as cultures enter into a low oxygen or reducing phase (Dibden & Green, 2005) due to increasing cell density or it may suggest that Anr is also capable of modulating gene expression without fully intact metallocentres or dimers.

Fig. 3.

Anr overexpression represses plcH transcript abundance at 21 % oxygen. qRT-PCR analysis of plcH and dnr normalized to ppiD in the WT pMQ123 and WT+pMQ123-anr. The data represent the mean±sd of two biological replicates. *P<0.05.

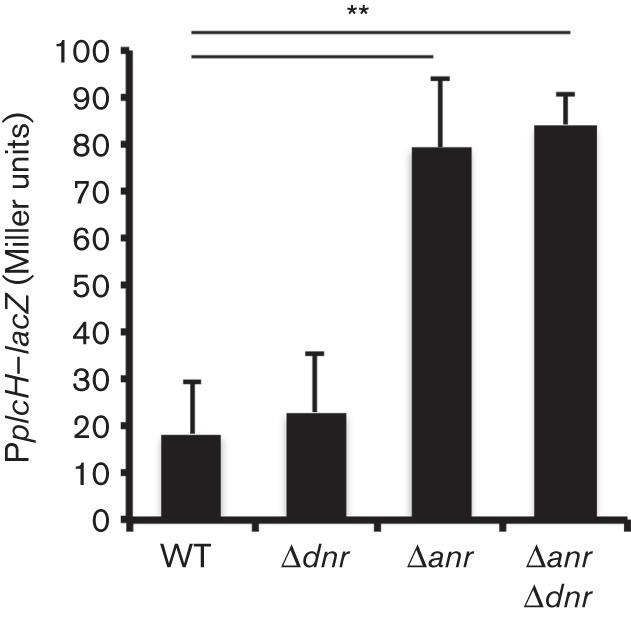

Dnr does not repress plcH in colony biofilms

Anr positively regulates a homologous transcriptional regulator, Dnr, which controls the subset of anoxia-induced genes involved in dissimilatory nitrate respiration and thus is required for anaerobic growth when nitrate is supplied as an electron acceptor (Arai et al., 1995, 1997) (Fig. S3). Although Anr and Dnr recognize the same consensus sequences, they have different modes of activation. Whilst Anr is active with an intact 4Fe–4S cluster, Dnr is activated when its haem cofactor is oxidized by nitric oxide and induces a conformational change in the protein that allows for DNA binding (Rodionov et al., 2005; Trunk et al., 2010). The two transcription factors regulate some of the same genes in P. aeruginosa (Rompf et al., 1998; Schreiber et al., 2007); however, Dnr did not appear to be involved in the repression of plcH. Whilst the Δanr mutant had higher plcH–lacZ activity under oxygen-limited conditions (P<0.01, Fig. 4), plcH transcription in the dnr mutant background was the same as in the WT (Fig. 4). Furthermore, the Δanr Δdnr double mutant displayed significantly more activity at the plcH promoter than the Δdnr single mutant and was indistinguishable from the Δanr mutant (Fig. 4, Δdnr compared with Δanr Δdnr), indicating that under these conditions Anr, not Dnr, plays a role in plcH repression.

Fig. 4.

Dnr does not play a role in plcH repression at 1 % oxygen. plcH promoter activity was assayed in PplcH–lacZ in WT, Δdnr, Δanr and Δanr Δdnr strains following growth on phosphate-supplemented blood agar plates for 16 h at 1 % oxygen. The data represent the mean±sd of three replicate colonies with similar results between independent experiments (n = 3). **P<0.01 (relative to WT).

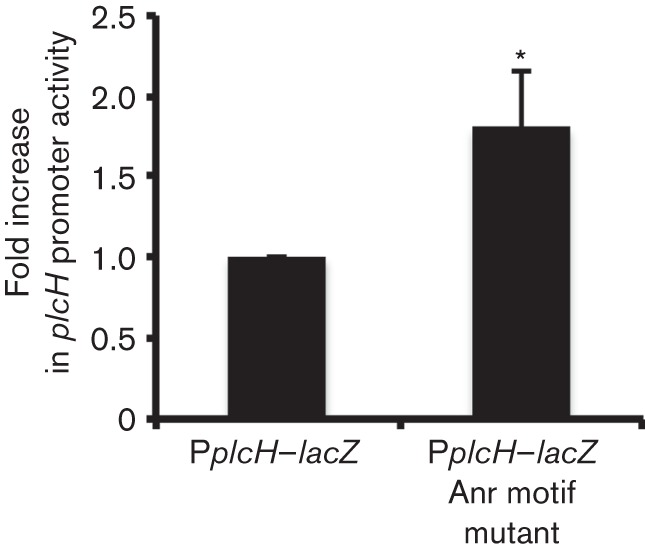

Anr consensus sequence is necessary for plcH repression at 1 % oxygen

To further test our hypothesis that Anr directly regulated the plcH promoter, mutagenesis of the Anr box within the promoter of a plcH–lacZYA plasmid, pMW22, was performed (Wargo et al., 2009). The canonical Anr consensus sequence was mutated from 5′-TTGAT-N4-ATCAA-3′ to 5′-CTGAT-N4-ATCAG-3′. These conservative substitutions were chosen based on published data that showed that Anr-mediated activation of the arcD promoter was reduced by eightfold upon mutating the corresponding nucleotides (Winteler & Haas, 1996). At a concentration of 1 % oxygen, P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 WT expressing the plcH promoter with the mutated Anr site fused to lacZ had twofold higher plcH expression when compared with the comparable strain expressing lacZ under the native plcH promoter (Fig. 5). These data were highly suggestive of a model in which negative regulation of the plcH promoter under oxygen-limiting conditions occurred via direct interaction between Anr and the plcH promoter.

Fig. 5.

Mutagenesis of the Anr motif in the plcH promoter derepresses expression under low oxygen. The fold change in plcH promoter activity in PAO1 WT PplcH–lacZ and a WT strain expressing the mutagenized plcH promoter lacZ fusion variant for 6 h at 1 % oxygen. The mean±sd of three biological replicates is reported. *P<0.05.

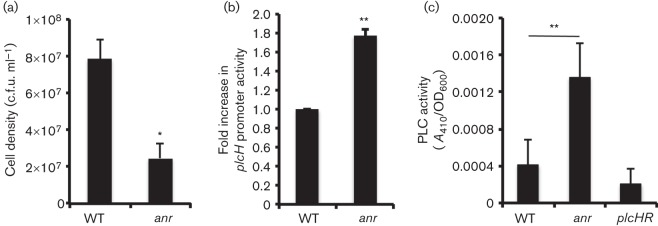

Anr represses plcH in co-culture biofilms on epithelial cells

Our previous work showed that PlcH production enhanced the activation of Anr in lung surfactant and upon early colonization of airway epithelial cells (Jackson et al., 2013). P. aeruginosa persists in the CF lung in a biofilm-like mode of growth (Moreau-Marquis et al., 2008), and data suggested that P. aeruginosa experiences oxygen limitation and induction of Anr in vivo (Hassett et al., 2009; Jackson et al., 2013; Petrova et al., 2012; Williamson et al., 2012; Worlitzsch et al., 2002). As P. aeruginosa forms robust biofilms in the CFBE airway epithelial co-culture model system and as Anr is important in this process (Anderson et al., 2008; Jackson et al., 2013), we sought to determine if Anr regulated plcH expression in this system. In order to assess plcH regulation in co-culture, P. aeruginosa PAO1 WT and Δanr strains were co-incubated with a confluent monolayer of CFTRΔF508 (CFBE41o−) homozygous human airway epithelial cells for 6 h to allow for biofilm formation (Anderson et al., 2008). Monolayer-associated cells were enumerated and, as published previously (Jackson et al., 2013), it was found that anr mutant co-cultures contained threefold fewer cells associated with the airway epithelium compared with WT (Fig. 6a). When plcH promoter activity was measured in WT and Δanr strains bearing the plcH–lacZ fusion on a plasmid, we found β-galactosidase levels were twofold higher in the anr mutant compared with the WT (Fig. 6b). Supernatants recovered from the Δanr mutant co-cultures contained significantly more PLC activity than WT (Fig. 6c). Together these data supported the model where Anr promoted biofilm formation and repressed plcH when colonizing epithelial cells.

Fig. 6.

Anr negatively regulates plcH on airway cells. (a) Cell density of WT and Δanr mutant biofilms on CFBE cells after 6 h. (b) Fold change in plcH promoter activity (PplcH–lacZ) in WT and Δanr strains after growth on CFBE cells for 6 h. (c) PLC activities of supernatants from cultures grown in association with bronchial epithelial cells for 6 h. PLC activity was measured by NPPC hydrolysis. The nitrophenol product was read at A410. The mean±sd of three biological replicates is reported in all panels. *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

Discussion

The regulation and roles of the important virulence factor PlcH are still being revealed. It was known that phosphate and choline catabolites, catabolite repression, and H-NS (histone-like nucleoid structuring protein) regulate plcH expression (Castang et al., 2008; Diab et al., 2006; Sage & Vasil, 1997; Shortridge et al., 1992; Wargo et al., 2009). Additionally, we have reported recently novel links between PlcH-mediated PC catabolism and activation of Anr, a transcription factor that promotes biofilm formation and virulence in P. aeruginosa (Jackson et al., 2013). Here, we show that Anr represses plcH in conditions as oxygen tensions become low, thereby creating a negative feedback loop in the control of PlcH activity (summarized in Fig. 7). The loss of a haemolytic phenotype during growth at 1 % oxygen was concomitant with reduced plcH transcription (Fig. 1). This evidence, and knowledge of principal hypoxia regulators, led us to suspect that Anr was the effector of this outcome. Mutants lacking Anr had more plcH promoter activity and PLC activity in cultures grown with 1 % oxygen (Fig. 2), and this was observed in both strains PAO1 and PA14. Under conditions where plcH transcription was not different between the WT and Δanr strains (21 % oxygen), Anr overexpression significantly decreased plcH transcript abundance, whilst increasing the abundance of other transcripts known to be regulated positively by Anr (Fig. 3). We also demonstrated that plcH promoter activity is higher in 1 % oxygen when the Anr-binding sequence is mutated (Fig. 5). Together, these data provide strong evidence that Anr negatively regulates plcH transcription under low oxygen conditions.

Fig. 7.

Model of Anr regulation of plcH and its role in infection. PlcH activity frees lipids and the choline-containing head group, which can be catabolized to choline phosphate (not shown), choline, GB and DMG by P. aeruginosa when oxygen is available (Massimelli et al., 2005, Wargo et al., 2008). GB and DMG act as ligands for GbdR, which activates plcH transcription (Wargo et al., 2009). Choline catabolism induces Anr activity under oxic conditions through an unknown mechanism and Anr activity, in turn, promotes biofilm formation in P. aeruginosa (Jackson et al., 2013). Biofilms are known to become limiting for oxygen at relatively low volumes (~55 pl) (Wessel, et al., 2014), which we expect to further increase Anr activity. In addition to plcH repression by the H-NS-like proteins MvaT/U (Castang et al., 2008), we have shown here that Anr represses plcH expression under conditions where oxygen levels are low. PlcH repression may contribute to a stable host–pathogen interaction.

Anr positively regulates target genes involved in utilization of alternate electron acceptors in the absence of oxygen. These target genes are regulated by secondary transcription factors that are active in the presence of their cognate electron acceptor. For example, the secondary regulator Dnr regulates enzymes involved in the stepwise reduction of nitrate to nitrogen gas in the absence of oxygen during denitrification (Arai et al., 1997, 1999; Hasegawa et al., 1998). In the course of this process, nitrite is reduced to nitric oxide, which binds to the haem cofactor present on Dnr and induces a conformational change in concert with carbon dioxide, allowing the transcription factor to bind to DNA (Arai et al., 1999; Castiglione et al., 2009; Giardina et al., 2009). Despite the fact that the Anr- and Dnr-binding sites are indistinguishable from one another (Giardina et al., 2009; Rodionov et al., 2005), we did not detect higher plcH levels in the dnr mutant indicating that Dnr was not playing a role in plcH repression under our conditions (Fig. 4). This lack of effect maybe be because nitrate was not added to the blood agar colony biofilms or the planktonic cultures and Dnr may play a role in controlling plcH transcription under other conditions where sources of nitric oxide are available, such as in the CF lung (259 µmol l−1) (Grasemann et al., 1998; Linnane et al., 1998). It is important to note that plcH mRNAs are detected across numerous samples, indicating that the regulation of this gene in vivo may be complex (Wargo et al., 2011).

As reported previously, the anr mutant was defective in biofilm formation on airway epithelia (Fig. 6) (Jackson et al., 2013). These same studies also showed that PlcH also contributes to host colonization. It is interesting to note that whilst the anr mutant was defective in host colonization, plcH promoter expression and PLC activity were higher in the Δanr co-culture supernatants. Together, these data are consistent with our previous work that indicated that one important role for PlcH in the co-culture model is in the activation of Anr and that Anr regulates other factors involved in host colonization.

This regulatory scheme in which PlcH activity is repressed by low oxygen conditions is surprising considering the numerous benefits of PlcH in P. aeruginosa colonization of and virulence towards diverse hosts (Fitzsimmons et al., 2011; Hogan & Kolter, 2002; Jackson et al., 2013; Wargo, 2013), acquisition of carbon, nitrogen and osmoprotectants (Son et al., 2007; Wargo et al., 2009), and resistance to host immunity (Terada et al., 1999). Anr regulation of PlcH may reflect the fact that PlcH-released catabolites (choline and lipids) require oxygen for catabolism (Wargo et al., 2008) (Fig. 7). Other sources of carbon, such as amino acids, are catabolized in an oxygen-independent manner (Barth & Pitt, 1996). Thus, it is reasonable to propose that PlcH production may become unfavourable under oxygen-limiting conditions.

In addition, it is possible that high levels of PlcH protein could be detrimental to the integrity of P. aeruginosa membranes as P. aeruginosa membranes contain ~4 % PC when grown on LB (Baysse et al., 2005). For this reason, a negative feedback loop in the control of PlcH could be beneficial in chronic infections produced by P. aeruginosa where oxygen becomes limiting (Bjarnsholt et al., 2008; Kirketerp-Møller et al., 2011; Kolpen et al., 2010; Worlitzsch et al., 2002). It is more striking to note that pulmonary pathologies such as CF, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD) are associated with increased vascularization (Wilson & Robertson, 2002). In CF patients, the absence or dysfunction of the CFTR protein has been demonstrated to promote the expression of proteins such as vascular endothelial growth factors A and C, which are involved in angiogenesis (i.e. the development of new blood vessels) in the CF airway (Martin et al., 2013; Verhaeghe et al., 2007). PlcH has been demonstrated to be selectively cytotoxic to endothelial cells at mere picomolar concentrations, as compared with minimal cytotoxicity towards epithelial cells (Vasil et al., 2009). One could imagine that expression of PlcH in the increasingly vascularized lung of a CF or COPD patient would result in an altered host–pathogen relationship that may not be advantageous. Future work will explore the consequence of Anr-mediated repression of plcH expression in models of chronic infection.

In an unexpected finding, Anr overexpression from a plasmid under high oxygen conditions increased PLC activity as measured by NPPC, suggesting that Anr promotes expression of a secondary NPPC-cleaving activity as it represses plcH expression (data not shown). The non-haemolytic PLC, PlcN, is a candidate for this Anr-induced PLC activity, as it can hydrolyse the NPPC reagent, but inefficiently hydrolyses phospholipids in the context of membranes (Ostroff et al., 1990). This would account for the increased PLC activity as observed by NPPC, but not observed on blood agar, and future studies will characterize this additional activity.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health (RO1AI091702; D. A. H.) and a NRSA Institutional Research Training Grant Fellowship (T32-DK007301 Renal function and Disease; A. A. J.). This work was also supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (P30GM106394) and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Research Development Program (STANTO07R0; Host–Pathogen Interaction Core in the Lung Biology Center at Dartmouth). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations:

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- CFBE

cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelial

- CFTR

cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder

- DMG

dimethylglycine

- GB

glycine betaine

- H-NS

histone-like nucleoid structuring protein

- NPPC

p-nitrophenyl-phosphorylcholine

- PC

phosphatidylcholine

- PLC

phospholipase C

- qRT

quantitative real-time.

Footnotes

Three supplementary figures are available with the online Supplementary Material.

References

- Alvarez-Ortega C., Harwood C. S. (2007). Responses of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to low oxygen indicate that growth in the cystic fibrosis lung is by aerobic respiration. Mol Microbiol 65, 153–165. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05772.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson G. G., Moreau-Marquis S., Stanton B. A., O’Toole G. A. (2008). In vitro analysis of tobramycin-treated Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms on cystic fibrosis-derived airway epithelial cells. Infect Immun 76, 1423–1433. 10.1128/IAI.01373-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai H., Igarashi Y., Kodama T. (1995). Expression of the nir and nor genes for denitrification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa requires a novel CRP/FNR-related transcriptional regulator, DNR, in addition to ANR. FEBS Lett 371, 73–76. 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00885-D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai H., Kodama T., Igarashi Y. (1997). Cascade regulation of the two CRP/FNR-related transcriptional regulators (ANR and DNR) and the denitrification enzymes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol 25, 1141–1148. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5431906.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai H., Kodama T., Igarashi Y. (1999). Effect of nitrogen oxides on expression of the nir and nor genes for denitrification in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol Lett 170, 19–24. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13350.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddour L., Wilson W., Bayer A., Fowler V. G. JrBolger A. F., Levison M. E., Ferrieri P., Gerber M. A., Tani L. Y. & other authors (2005). Infective endocarditis: antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, American Heart Association: Endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Circulation 111, e394–e433. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.165564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth A. L., Pitt T. L. (1996). The high amino-acid content of sputum from cystic fibrosis patients promotes growth of auxotrophic Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Med Microbiol 45, 110–119. 10.1099/00222615-45-2-110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baysse C., Cullinane M., Dénervaud V., Burrowes E., Dow J. M., Morrissey J. P., Tam L., Trevors J. T., O’Gara F. (2005). Modulation of quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa through alteration of membrane properties. Microbiology 151, 2529–2542. 10.1099/mic.0.28185-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berka R. M., Vasil M. L. (1982). Phospholipase C (heat-labile hemolysin) of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: purification and preliminary characterization. J Bacteriol 152, 239–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjarnsholt T., Kirketerp-Møller K., Jensen P. Ø., Madsen K. G., Phipps R., Krogfelt K., Høiby N., Givskov M. (2008). Why chronic wounds will not heal: a novel hypothesis. Wound Repair Regen 16, 2–10. 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00283.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castang S., McManus H. R., Turner K. H., Dove S. L. (2008). H-NS family members function coordinately in an opportunistic pathogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 18947–18952. 10.1073/pnas.0808215105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castiglione N., Rinaldo S., Giardina G., Cutruzzolà F. (2009). The transcription factor DNR from Pseudomonas aeruginosa specifically requires nitric oxide and haem for the activation of a target promoter in Escherichia coli. Microbiology 155, 2838–2844. 10.1099/mic.0.028027-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K. H., Schweizer H. P. (2006). mini-Tn7 insertion in bacteria with single attTn7 sites: example Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nat Protoc 1, 153–161. 10.1038/nprot.2006.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier D. N., Hager P. W., Phibbs P. V., Jr (1996). Catabolite repression control in the Pseudomonads. Res Microbiol 147, 551–561. 10.1016/0923-2508(96)84011-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozens A. L., Yezzi M. J., Kunzelmann K., Ohrui T., Chin L., Eng K., Finkbeiner W. E., Widdicombe J. H., Gruenert D. C. (1994). CFTR expression and chloride secretion in polarized immortal human bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 10, 38–47. 10.1165/ajrcmb.10.1.7507342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Macedo J. L., Santos J. B. (2005). Bacterial and fungal colonization of burn wounds. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 100, 535–539. 10.1590/S0074-02762005000500014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diab F., Bernard T., Bazire A., Haras D., Blanco C., Jebbar M. (2006). Succinate-mediated catabolite repression control on the production of glycine betaine catabolic enzymes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 under low and elevated salinities. Microbiology 152, 1395–1406. 10.1099/mic.0.28652-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibden D. P., Green J. (2005). In vivo cycling of the Escherichia coli transcription factor FNR between active and inactive states. Microbiology 151, 4063–4070. 10.1099/mic.0.28253-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimmons L. F., Flemer S., Jr, Wurthmann A. S., Deker P. B., Sarkar I. N., Wargo M. J. (2011). Small-molecule inhibition of choline catabolism in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other aerobic choline-catabolizing bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 77, 4383–4389. 10.1128/AEM.00504-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galimand M., Gamper M., Zimmermann A., Haas D. (1991). Positive FNR-like control of anaerobic arginine degradation and nitrate respiration in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 173, 1598–1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giardina G., Rinaldo S., Castiglione N., Caruso M., Cutruzzolà F. (2009). A dramatic conformational rearrangement is necessary for the activation of DNR from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Crystal structure of wild-type DNR. Proteins 77, 174–180. 10.1002/prot.22428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasemann H., Ioannidis I., Tomkiewicz R. P., de Groot H., Rubin B. K., Ratjen F. (1998). Nitric oxide metabolites in cystic fibrosis lung disease. Arch Dis Child 78, 49–53. 10.1136/adc.78.1.49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M., Apel A., Stapleton F. (2008). Risk factors and causative organisms in microbial keratitis. Cornea 27, 22–27. 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318156caf2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa N., Arai H., Igarashi Y. (1998). Activation of a consensus FNR-dependent promoter by DNR of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in response to nitrite. FEMS Microbiol Lett 166, 213–217. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13892.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassett D. J., Sutton M. D., Schurr M. J., Herr A. B., Caldwell C. C., Matu J. O. (2009). Pseudomonas aeruginosa hypoxic or anaerobic biofilm infections within cystic fibrosis airways. Trends Microbiol 17, 130–138. 10.1016/j.tim.2008.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J., Baldini R. L., Déziel E., Saucier M., Zhang Q., Liberati N. T., Lee D., Urbach J., Goodman H. M., Rahme L. G. (2004). The broad host range pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA14 carries two pathogenicity islands harboring plant and animal virulence genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101, 2530–2535. 10.1073/pnas.0304622101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidron A. I., Edwards J. R., Patel J., Horan T. C., Sievert D. M., Pollock D. A., Fridkin S. K., National Healthcare Safety Network Team. Participating National Healthcare Safety Network Facilities (2008). NHSN annual update: antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: annual summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006–2007. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 29, 996–1011. 10.1086/591861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan D. A., Kolter R. (2002). Pseudomonas–Candida interactions: an ecological role for virulence factors. Science 296, 2229–2232. 10.1126/science.1070784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Høiby N., Krogh Johansen H., Moser C., Song Z., Ciofu O., Kharazmi A. (2001). Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the in vitro and in vivo biofilm mode of growth. Microbes Infect 3, 23–35. 10.1016/S1286-4579(00)01349-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A. A., Gross M. J., Daniels E. F., Hampton T. H., Hammond J. H., Vallet-Gely I., Dove S. L., Stanton B. A., Hogan D. A. (2013). Anr and its activation by PlcH activity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa host colonization and virulence. J Bacteriol 195, 3093–3104. 10.1128/JB.02169-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jander G., Rahme L. G., Ausubel F. M. (2000). Positive correlation between virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants in mice and insects. J Bacteriol 182, 3843–3845. 10.1128/JB.182.13.3843-3845.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y., Nguyen D. T., Son M. S., Hoang T. T. (2008). The Pseudomonas aeruginosa PsrA responds to long-chain fatty acid signals to regulate the fadBA5 beta-oxidation operon. Microbiology 154, 1584–1598. 10.1099/mic.0.2008/018135-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami T., Kuroki M., Ishii M., Igarashi Y., Arai H. (2010). Differential expression of multiple terminal oxidases for aerobic respiration in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ Microbiol 12, 1399–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirketerp-Møller K., Zulkowski K., James G. (2011). Chronic Wound Colonization, Infection, and Biofilms. New York: Springer Science+Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Kolpen M., Hansen C. R., Bjarnsholt T., Moser C., Christensen L. D., van Gennip M., Ciofu O., Mandsberg L., Kharazmi A. & other authors (2010). Polymorphonuclear leucocytes consume oxygen in sputum from chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia in cystic fibrosis. Thorax 65, 57–62. 10.1136/thx.2009.114512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurioka S., Matsuda M. (1976). Phospholipase C assay using p-nitrophenylphosphoryl-choline together with sorbitol and its application to studying the metal and detergent requirement of the enzyme. Anal Biochem 75, 281–289. 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90078-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazazzera B. A., Beinert H., Khoroshilova N., Kennedy M. C., Kiley P. J. (1996). DNA binding and dimerization of the Fe–S-containing FNR protein from Escherichia coli are regulated by oxygen. J Biol Chem 271, 2762–2768. 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnane S. J., Keatings V. M., Costello C. M., Moynihan J. B., O’Connor C. M., Fitzgerald M. X., McLoughlin P. (1998). Total sputum nitrate plus nitrite is raised during acute pulmonary infection in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 158, 207–212. 10.1164/ajrccm.158.1.9707096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C. D., Winteler H., Abdelal A., Haas D. (1999). The ArgR regulatory protein, a helper to the anaerobic regulator ANR during transcriptional activation of the arcD promoter in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 181, 2459–2464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malek A. A., Chen C., Wargo M. J., Beattie G. A., Hogan D. A. (2011). Roles of three transporters, CbcXWV, BetT1, and BetT3, in Pseudomonas aeruginosa choline uptake for catabolism. J Bacteriol 193, 3033–3041. 10.1128/JB.00160-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C., Coolen N., Wu Y., Thévenot G., Touqui L., Prulière-Escabasse V., Papon J. F., Coste A., Escudier E. & other authors (2013). CFTR dysfunction induces vascular endothelial growth factor synthesis in airway epithelium. Eur Respir J 42, 1553–1562. 10.1183/09031936.00164212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massimelli M. J., Beassoni P. R., Forrellad M. A., Barra J. L., Garrido M. N., Domenech C. E., Lisa A. T. (2005). Identification, cloning, and expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa phosphorylcholine phosphatase gene. Curr Microbiol 50, 251–256. 10.1007/s00284-004-4499-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J. H. (1992). A Short Course in Bacterial Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. [Google Scholar]

- Moreau-Marquis S., Stanton B. A., O’Toole G. A. (2008). Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation in the cystic fibrosis airway. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 21, 595–599. 10.1016/j.pupt.2007.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neidhardt F. C., Bloch P. L., Smith D. F. (1974). Culture medium for enterobacteria. J Bacteriol 119, 736–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostroff R. M., Vasil A. I., Vasil M. L. (1990). Molecular comparison of a nonhemolytic and a hemolytic phospholipase C from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 172, 5915–5923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrova O. E., Schurr J. R., Schurr M. J., Sauer K. (2012). Microcolony formation by the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa requires pyruvate and pyruvate fermentation. Mol Microbiol 86, 819–835. 10.1111/mmi.12018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahme L. G., Ausubel F. M., Cao H., Drenkard E., Goumnerov B. C., Lau G. W., Mahajan-Miklos S., Plotnikova J., Tan M. W. & other authors (2000). Plants and animals share functionally common bacterial virulence factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97, 8815–8821. 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajan S., Saiman L. (2002). Pulmonary infections in patients with cystic fibrosis. Semin Respir Infect 17, 47–56. 10.1053/srin.2002.31690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodionov D. A., Dubchak I. L., Arkin A. P., Alm E. J., Gelfand M. S. (2005). Dissimilatory metabolism of nitrogen oxides in bacteria: comparative reconstruction of transcriptional networks. PLOS Comput Biol 1, e55. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0010055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rompf A., Hungerer C., Hoffmann T., Lindenmeyer M., Römling U., Gross U., Doss M. O., Arai H., Igarashi Y., Jahn D. (1998). Regulation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa hemF and hemN by the dual action of the redox response regulators Anr and Dnr. Mol Microbiol 29, 985–997. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00980.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld M., Ramsey B. W., Gibson R. L. (2003). Pseudomonas acquisition in young patients with cystic fibrosis: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Curr Opin Pulm Med 9, 492–497. 10.1097/00063198-200311000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage A. E., Vasil M. L. (1997). Osmoprotectant-dependent expression of plcH, encoding the hemolytic phospholipase C, is subject to novel catabolite repression control in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J Bacteriol 179, 4874–4881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage A. E., Vasil A. I., Vasil M. L. (1997). Molecular characterization of mutants affected in the osmoprotectant-dependent induction of phospholipase C in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Mol Microbiol 23, 43–56. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.1681542.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawers R. G. (1991). Identification and molecular characterization of a transcriptional regulator from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 exhibiting structural and functional similarity to the FNR protein of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 5, 1469–1481. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00793.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber K., Krieger R., Benkert B., Eschbach M., Arai H., Schobert M., Jahn D. (2007). The anaerobic regulatory network required for Pseudomonas aeruginosa nitrate respiration. J Bacteriol 189, 4310–4314. 10.1128/JB.00240-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer H. P. (1991). Escherichia–Pseudomonas shuttle vectors derived from pUC18/19. Gene 97, 109–112. 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90016-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanks R. M., Caiazza N. C., Hinsa S. M., Toutain C. M., O’Toole G. A. (2006). Saccharomyces cerevisiae-based molecular tool kit for manipulation of genes from gram-negative bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 72, 5027–5036. 10.1128/AEM.00682-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortridge V. D., Lazdunski A., Vasil M. L. (1992). Osmoprotectants and phosphate regulate expression of phospholipase C in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol 6, 863–871. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01537.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons R. W., Houman F., Kleckner N. (1987). Improved single and multicopy lac-based cloning vectors for protein and operon fusions. Gene 53, 85–96. 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90095-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son M. S., Matthews W. J., Jr, Kang Y., Nguyen D. T., Hoang T. T. (2007). In vivo evidence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa nutrient acquisition and pathogenesis in the lungs of cystic fibrosis patients. Infect Immun 75, 5313–5324. 10.1128/IAI.01807-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover C. K., Pham X. Q., Erwin A. L., Mizoguchi S. D., Warrener P., Hickey M. J., Brinkman F. S., Hufnagle W. O., Kowalik D. J. & other authors (2000). Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406, 959–964. 10.1038/35023079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada L. S., Johansen K. A., Nowbar S., Vasil A. I., Vasil M. L. (1999). Pseudomonas aeruginosa hemolytic phospholipase C suppresses neutrophil respiratory burst activity. Infect Immun 67, 2371–2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trunk K., Benkert B., Quäck N., Münch R., Scheer M., Garbe J., Jänsch L., Trost M., Wehland J. & other authors (2010). Anaerobic adaptation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: definition of the Anr and Dnr regulons. Environ Microbiol 12, 1719–1733. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02252.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasil M. (1994). Phosphate and osmoprotectants in the pathogenesis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In Phosphate in Microorganisms: Cellular and Molecular Biology, pp. 126–132. Edited by Torriani-Gorini A., Yagil E., Silver S. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology. [Google Scholar]

- Vasil M. (2006). Pseudomonas aeruginosa phospholipases and phospholipids. In Pseudomonas, pp. 69–97. Edited by Ramos J., Levesque R. Dordrecht: Springer; 10.1007/0-387-28881-3_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vasil M. L., Stonehouse M. J., Vasil A. I., Wadsworth S. J., Goldfine H., Bolcome R. E., III, Chan J. (2009). A complex extracellular sphingomyelinase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa inhibits angiogenesis by selective cytotoxicity to endothelial cells. PLoS Pathog 5, e1000420. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghe C., Tabruyn S. P., Oury C., Bours V., Griffioen A. W. (2007). Intrinsic pro-angiogenic status of cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 356, 745–749. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.02.166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wargo M. J. (2013). Choline catabolism to glycine betaine contributes to Pseudomonas aeruginosa survival during murine lung infection. PLoS ONE 8, e56850. 10.1371/journal.pone.0056850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wargo M. J., Szwergold B. S., Hogan D. A. (2008). Identification of two gene clusters and a transcriptional regulator required for Pseudomonas aeruginosa glycine betaine catabolism. J Bacteriol 190, 2690–2699. 10.1128/JB.01393-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wargo M. J., Ho T. C., Gross M. J., Whittaker L. A., Hogan D. A. (2009). GbdR regulates Pseudomonas aeruginosa plcH and pchP transcription in response to choline catabolites. Infect Immun 77, 1103–1111. 10.1128/IAI.01008-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wargo M. J., Gross M. J., Rajamani S., Allard J. L., Lundblad L. K., Allen G. B., Vasil M. L., Leclair L. W., Hogan D. A. (2011). Hemolytic phospholipase C inhibition protects lung function during Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 184, 345–354. 10.1164/rccm.201103-0374OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessel A. K., Arshad T. A., Fitzpatrick M., Connell J. L., Bonnecaze R. T., Shear J. B., Whiteley M. (2014). Oxygen limitation within a bacterial aggregate. MBio 5, e00992-14. 10.1128/mBio.00992-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West S. E., Schweizer H. P., Dall C., Sample A. K., Runyen-Janecky L. J. (1994). Construction of improved Escherichia–Pseudomonas shuttle vectors derived from pUC18/19 and sequence of the region required for their replication in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene 148, 81–86. 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90237-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson K. S., Richards L. A., Perez-Osorio A. C., Pitts B., McInnerney K., Stewart P. S., Franklin M. J. (2012). Heterogeneity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms includes expression of ribosome hibernation factors in the antibiotic-tolerant subpopulation and hypoxia-induced stress response in the metabolically active population. J Bacteriol 194, 2062–2073. 10.1128/JB.00022-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J. W., Robertson C. F. (2002). Angiogenesis in paediatric airway disease. Paediatr Respir Rev 3, 219–229. 10.1016/S1526-0542(02)00200-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winsor G. L., Lam D. K., Fleming L., Lo R., Whiteside M. D., Yu N. Y., Hancock R. E., Brinkman F. S. (2011). Pseudomonas Genome Database: improved comparative analysis and population genomics capability for Pseudomonas genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 39 (Database issue), D596–D600. 10.1093/nar/gkq869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winteler H. V., Haas D. (1996). The homologous regulators ANR of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and FNR of Escherichia coli have overlapping but distinct specificities for anaerobically inducible promoters. Microbiology 142, 685–693. 10.1099/13500872-142-3-685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worlitzsch D., Tarran R., Ulrich M., Schwab U., Cekici A., Meyer K. C., Birrer P., Bellon G., Berger J. & other authors (2002). Effects of reduced mucus oxygen concentration in airway Pseudomonas infections of cystic fibrosis patients. J Clin Invest 109, 317–325. 10.1172/JCI0213870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye R. W., Haas D., Ka J. O., Krishnapillai V., Zimmermann A., Baird C., Tiedje J. M. (1995). Anaerobic activation of the entire denitrification pathway in Pseudomonas aeruginosa requires Anr, an analog of Fnr. J Bacteriol 177, 3606–3609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Bremer H. (1995). Control of the Escherichia coli rrnB P1 promoter strength by ppGpp. J Biol Chem 270, 11181–11189. 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]